RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

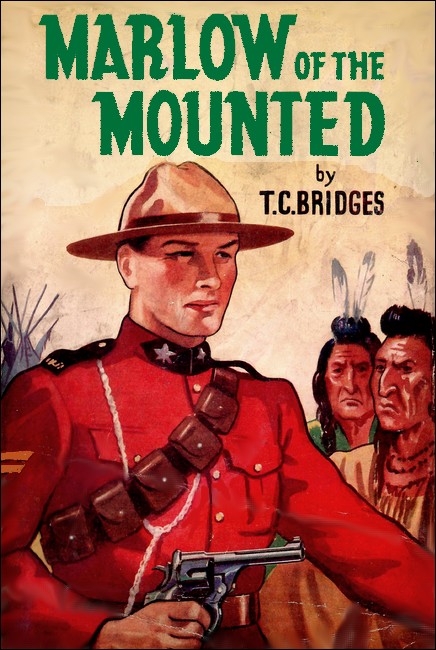

"Marlow of the Mounted," F. Warne & Co., 1946, Dust Jacket

"Marlow of the Mounted," F. Warne & Co., 1946, Book Cover

"Marlow of the Mounted," Title Page of First Edition

Keith Marlow, fresh from training at the Mounted Police Barracks, Regina, finds himself heading for Kutchin Country and the Rockies to round up white dope peddlers. A long, torturous trail lies in front of Keith and many hardships have to be overcome, before his mission is successfully completed.

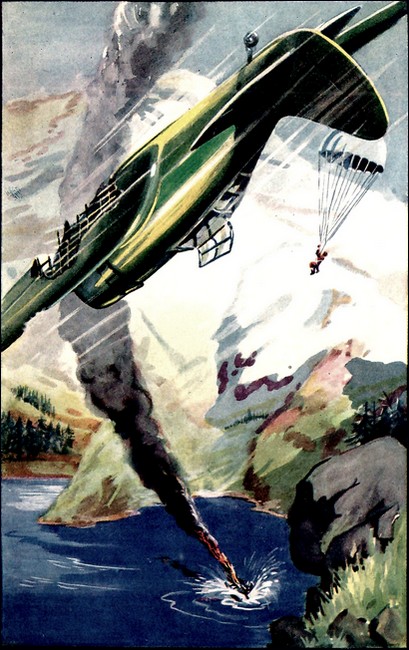

Frontispiece.

A small object detached itself from the tumbling wreckage.

KEITH MARLOW had learned much during the twelve terrible days that he had been on the trail of Jake Dranner. Fresh from training at the Mounted Police Barracks at Regina, Keith was too young and too inexperienced for such a task as hunting down this killer who was vicious and dangerous as a timber wolf.

As it happened there was no choice, for Corporal Duncan Maclaine, Keith's senior at Sundance, was suffering from a sprained ankle and the business of catching Dranner was urgent. Dranner had shot down Joe Pelly in cold blood, murdered him for the sake of some fifty ounces of dust which the old man had spent the whole summer in painfully washing from the gravel of Caribou Creek. The killing had been done up in the lonely Glenlyon hills and it was by pure chance that François Armand, a breed trapper, had stumbled on the body within twenty-four hours of the murder. Armand had not only found Pelly's body, but had spotted the murderer's tracks to which he declared he could swear. One of the webs had been mended with string, and the prints had been plain on the new fallen snow.

It was now late October, the worst season of the year for a long trek through the back country. Winter was setting in and snow-storms frequent but, on the other hand, the swift streams were not yet firmly frozen. For the first week of his journey Keith had travelled more or less at random, merely following the direction in which he thought Dranner would move. He had begun to despair when, at last, the luck turned and he struck the trail of the fugitive. The mark of the mended web was unmistakable.

Even then it was not easy. Two nights later a snow-storm wiped out the tracks, but Keith found them again and followed them into a long valley leading through desolate unnamed hills.

"He's got all old Pelly's stores," Maclaine had told Keith, "and his dogs. Ah'm thinking he'll hole up for the winter in some deserted cabin, for he canna get oot till the spring. Ah'm dooting ye'll find him but, gin ye do, be careful. The mon will bushwhack ye and shoot ye down wi' as little compunction as if ye were a skunk."

Maclaine's warning was in Keith's mind as he drove his dogs up the faint trail on the afternoon of the twelfth day. The sky was overcast and a few flakes of hard-frozen snow were drifting down. Darkness would soon close on the desolate scene and Keith had to find a camping place for the night. The prospect was not promising for there was little timber at this height, and Keith needed not only firewood but shelter, for without doubt a fresh storm was brewing.

A tiny point of light showed through the gloom. Keith rubbed his tired eyes with the back of his mitt. There was no doubt about it: the light, faint as it was, remained steady and Keith knew that it came from a lamp behind a window. A surge of excitement ran through his veins. There must be a cabin to the right of the trail and it was all odds that this was where Dranner had taken refuge.

Now Keith had to remember all that he had been told, for any mistake on his part would be fatal. Instead of the triumph of handing over the murderer to justice his own death would be certain. Dranner was armed, watchful and desperate. Also he would have dogs which, at the approach of another team, would give tongue at once: so the first thing Keith did was to turn his own dogs off the trail and tie them under shelter of some large boulders. He examined his pistol to see that it was loaded, then walked forward, making a circle to windward, so that Dranner's dogs could not scent him.

The wind was getting stronger every minute, the snow thickening into a driving swirl of white. Keith shivered as he stood just to windward of the cabin and wondered what to do next. There was nothing about it in the book of rules, and Keith himself had no experience in the matter of arresting criminals. For a moment he felt an unpleasant sensation of loneliness, but this did not last. After all, he had done a good job in trailing Dranner. Surely he could crown it by capturing the brute.

He looked at the cabin. So far as he could see in the thickening snow and failing light, it was the usual one-room shack built of logs and chinked with clay. There was a lean-to at the back. It stood in a patch of wind-stunted spruce. It had a door in front and one window, the panes of which were filled with oiled paper, a usual substitute for glass in the far places of the north. To attempt to enter by the door was suicide, for if this were Dranner he would shoot first and talk afterwards. The window was the best bet so Keith advanced cautiously until he was able to peep through.

If the young constable had had any doubts about the identity of the occupant of the cabin these were at once dispelled. One glance at the face of the man who sat smoking by the almost red- hot stove was enough. The light of the small oil-lamp standing on the home-made table showed it to be long and narrow, with pinched nose, thin lips and cold greenish-grey eyes set deep under bony temples. It was not improved by the fact that its owner had not troubled to shave for at least a week. He wore a greasy mackinaw coat and his heavy trousers were tucked into high boots. Keith noticed that a blued automatic lay on the table and that a rifle leaned against the wall almost within arm's reach of the man.

"Not a nice gentleman," muttered Keith, with a ghost of a grin on his half-frozen lips. "It's no use looking at him. I have to get him." He drew his service revolver and all in one act smashed the window and thrust the muzzle through the opening.

"Hands up, Dranner!" he ordered sharply.

The results were not what Keith had anticipated. One of Dranner's hands went up but with the other he swept the lamp from the table, thereby plunging the little room into almost complete darkness.

This was the moment when Keith should have fired, but it is a point of honour with the Royal Regiment to bring in their prisoners alive. He hesitated and his hesitation almost cost him his life for Dranner, who had dropped to the floor, must have had a second gun about him. This bullet cut splinters from the side of the window, which stung Keith's face. Keith staggered back, uttered a realistic groan and dropped heavily to the ground. But he did not stay there. Crawling on hands and knees he made round the corner to the front door of the shack. It was his hope that Dranner would believe he had killed his visitor and would come out to view the body.

But Dranner was cautious. He did not relight the lamp. Keith, listening intently, heard him rise and go to the window. No doubt he was peering out to see the body but, by this time, the snow was so thick and driving so furiously that Keith was convinced the man could see nothing.

Keith was angry and disappointed. His attack had completely failed. All he had done was to warn his quarry. Now, if Dranner had sense to stay inside the shack, he was safe. Keith could not remain here long, exposed to this blizzard. He would have to go back to his dogs and camp. There was only one grain of comfort in the situation, so far as Keith was concerned. Dranner had no dogs. If he had had a team they would have started barking at the shot. What had happened to them Keith could not guess, but the result was that Dranner could not travel. At any rate he could not go far from this cabin, for he would not be able to carry enough food to last him more than a few days.

On the other hand he probably had a good stock in the cabin while Keith had enough for a week only and it meant five days' hard travelling to reach Sundance.

The cold bit through Keith's fur parka. If he stood here in the wind much longer he would be frost-bitten. He was on the point of giving up and returning to his dogs when he heard a faint click. The latch was being lifted. A fresh wave of excitement made Keith forget the cold, forget everything except that Dranner was coming out. With his body pressed against the wall he stood perfectly still, hardly breathing.

The door opened inwards and the strong draught rushing in made the stove roar. The result was that a faint glow of light thrown by the flaming wood through chinks in the rusty old firebox illuminated the interior of the cabin and showed Keith an arm and hand grasping a pistol in the opening. Keith was desperately tempted to chop down on that arm with the barrel of his own gun but he resisted the temptation. It was well for him that he did for next moment he realised that it was a clever trap. The arm was too thick to be natural and he saw that it was protected by pelts rolled around it. The heaviest blow that Keith could have dealt would have done little damage.

Keith smiled grimly to himself. This time at any rate he had outsmarted his enemy.

But would Dranner come out? That was the question. He did, but not in the way Keith had expected. Instead of moving out cautiously he came with a rush. He was past Keith before Keith could land the blow he had been saving for the fellow's skull. But Keith was on him before he could turn on him with such force that Dranner went flat on his face on the frozen ground, Keith on top of him. There was not enough snow to deaden the shock and Keith exulted as he heard the breath go out of the man's body with one great gasp.

Certain that he was master, Keith relaxed his hold to fumble in his pocket for the handcuffs. This was his second blunder for Dranner suddenly exploded. That at least was what it felt like to Keith who was flung off the other's body and only just saved himself from rolling over sideways. With a snarl Dranner swung his right hand in which he still held his pistol. One bullet would finish the business.

IT would have done so but for those skins wrapped around Dranner's forearm. They made him clumsy and the fraction of a second which he lost gave Keith a fresh chance. With his left hand he forced up Dranner's right arm; and the flaming gun flung its missile harmlessly into the air. At the same time Keith punched with his right and, though the blow lacked force owing to Keith being on his knees, it rocked Dranner's head back. Before he could recover, Keith had clamped a two-handed grip on Dranner's right arm.

Keith Marlow at twenty was five-foot-ten, weighed eleven and a half stone and was fit as hard training could make him. It gave him an ugly shock to find that Dranner, who was probably twenty years older than he, was able to withstand that grip and still hold on to the revolver. Not only that but the man managed to rise to his feet, dragging Keith up with him. Keith wrenched at Dranner's wrist in an effort to force him to drop the pistol. He failed and Dranner retaliated with a savage kick which almost numbed Keith's left leg. Keith closed; and the two, clenched in a death struggle for the possession of the gun, rolled to and fro in the gloom of the blizzard.

Their battle brought them nearer and nearer to the door of the cabin. Keith could see this but Dranner, with his back to the cabin, was unaware of it. Keith was beginning to feel that he could not last much longer. His leg was hurting horribly. He resolved to take a chance. He let go with his right hand and drove for Dranner's jaw. His fist landed high but the blow staggered Dranner. He stepped backwards and banged his head against the wall of the cabin. That was enough for Keith. Before Dranner could recover from the dazing crack on his skull, Keith let loose a second blow which caught Dranner on the chin. It was like hitting a rock, for Dranner's head was still pressed against the wall, but it did the trick. The vicious eyes of the murderer glazed and he slipped to the ground limp as a sack, the pistol dropping from his relaxed fist. Keith kicked the pistol aside, snapped the steel cuffs on Dranner's thick wrists, dragged him inside and tied his ankles with a length of raw hide. Then he closed the door, re-lit the lamp, and dropped on the bunk where he lay for several minutes, drawing deep breaths into his aching lungs.

When he got up, Dranner was still insensible but he was breathing easily and Keith let him lie. There was a pot on the stove with coffee in it. Keith found a mug, filled it with the strong black liquid, added three spoonfuls of sugar and drank it down. Then he looked at his damaged leg and was relieved to find that although the flesh was swollen and blue, there was nothing broken.

He remembered his dogs. He must bring them in. As he got up he glanced again at Dranner. Dranner's eyes were open and the look in them sent a shiver down Keith's spine. There was savage hate in them. That was to be expected; but there was more. A sort of cold, cruel calculation which made Keith wonder what fresh tricks this human fiend had in store for him. He did not hide from himself that he had a long march before him before reaching Sundance and that, during every moment of the journey, he would have to be on guard. With nothing but the rope in front of him, no chance would be too desperate for Dranner. Before leaving the cabin Keith removed Dranner's two pistols and the rifle. He found also an ugly-looking knife which he stuck in his own belt.

Although the distance to the boulders was less than half a mile it taxed Keith's strength to the uttermost to reach them. The storm was developing into a real blizzard but, luckily for Keith, the wind had not yet reached its full force. The return journey was not so bad for the wind was behind him. For all that, by the time Keith had tied his dogs in the lean-to and fed them he was pretty near the end of his tether.

The prospect of spending the night under cover should have been pleasant but, for Keith, was completely spoiled by the knowledge that he had to be under the same roof and in the same room with Dranner. There was something so sinister, so repulsive about the man that Keith hated breathing the same air with him. It was, however, useless to be squeamish so Keith carried his sleeping-bag into the cabin, built up the fire and set to cooking supper. There was plenty of food in the place but everything was filthy and, tired as he was, Keith had to melt snow and heat water to wash out the cooking pans. Since there was no bread, he made bannocks and these, with fried bacon and fresh coffee, were the first course. The second was a tin of peaches which Keith had been keeping for a special occasion.

All the time that he was cooking and while he ate Dranner lay on the floor watching him, but saying not a word. Even when Keith had his back to the man he could feel those narrow grey-green eyes fixed upon him.

Having finished his own meal Keith fed his prisoner. But before doing so he chained him to the heavy log forming the foot of the bunk. This light steel chain and padlock he was carrying by the advice of Duncan Maclaine, and very glad he was to have it. Dranner offered no resistance and ate his food in silence, but Keith could feel the waves of hatred that emanated from the man almost as clearly as if they were expressed in blows.

Keith's whole body was one ache. The fight at the end of a hard day's mush had drained his strength and he knew that he must sleep well before taking up the trail again.

"You can have the bunk," he told Dranner curtly. He went out and fetched in his lead dog, Koltag. Koltag was a magnificent beast, partly grey, partly black, fanged like a wolf. The moment he came into the room the hair on his back rose in a stiff ridge, his yellow eyes flamed and a low growl rumbled in his throat. Keith laid a hand on the dog's massive head.

"Quiet, boy!" he ordered and the rumble died, but Koltag's eyes remained fixed upon Dranner. "I don't think you will try any monkey business," Keith continued, speaking to Dranner. "I don't believe you can. But if you do it is a dead body I shall take back to Sundance, not a living man."

A slight sneer curled Dranner's lips, but that was all. Keith realized that the man, if all brute, had the courage of the brute and was more dangerous than any brute. Yet, confident that Koltag would rouse him if anything went wrong, he took off his boots, slipped into his bag and, within a couple of minutes, was dead asleep.

When he woke it was still dark, the fire in the stove had died down and the room was bitter cold. He looked at the luminous dial of his wrist-watch and saw that it was past six. He had had nine hours' sleep and felt immensely refreshed. His leg still pained him but that would wear off with movement. He lit the lamp, made up the fire, then went out to feed his dogs and look at the weather.

The snow had ceased, the wind fallen and there seemed prospect of a fairly fine day; but Keith was dismayed at the amount of snow that had fallen in the night. The stuff was fine as flour and as difficult to walk in. It meant breaking trail for the dogs every yard of the way and speed would be cut down to perhaps two miles an hour. It was going to be a rotten journey but, after all, Keith had his man and would not have been human if he had not felt a little glow of triumph at the thought that his first official mission had been successful.

He went back into the hut and got breakfast. As on the previous night Dranner made no trouble. After he had eaten Keith handcuffed him again and left him chained. He had a job to do before packing for the start. That was to find the gold which no doubt Dranner had hidden somewhere under the floor of the shack. Dranner watched Keith sardonically as he set to work then, to Keith's amazement, spoke.

"No need to waste time, constable. The dust's under the stove."

IT was a job to move the stove which was nearly red hot, but Keith did it and found a buckskin bag which held nearly five pounds weight of coarse gold. Keith made no sign of his astonishment that Dranner should have told him where it was but, at the same time, he did not like it. It seemed to him that Dranner must be very sure of escaping—and of taking the gold with him. Again Keith resolved that he would not give the murderer the least ghost of a chance.

A pale sun was rising in an icy sky as the two left the cabin. Keith made Dranner walk ahead and break trail. It was hard work for, at times, the man was thigh deep in the dry powdery stuff. But Dranner did not remonstrate and noon found them on lower ground where the snow was not so heavy. The midday meal was eaten under shelter of a bluff and, as the dogs were tired, Keith gave them a full hour's rest. Even so, Keith succeeded in reaching the spot where he had intended to camp, a grove of thick spruce where there was shelter from the wind and plenty of firewood. Again he chained his prisoner and left Koltag to guard him while he made camp. He did everything himself. He would not trust Dranner to do anything. The man sat smoking, watching the other work with the same sardonic look in his deep-set eyes. Keith would have given a good deal to be able to read his thoughts.

Next morning the sky was overcast and the clouds hung low. As the sun rose a wind came with it, a keen steady breeze from north-west. "Snow!" muttered Keith, and he was right. They had hardly finished breakfast before it began. Keith had not yet spent a winter in the north so had not the weather sense of more experienced men. He wondered if it would be wiser to remain in camp rather than risk travelling in what might be a blizzard. But the thought of being cooped up with Dranner for another twenty- four hours was so repulsive that he resolved to risk it. After breakfast he harnessed up.

It was fine driving snow. The particles, hard and sharp as sand, packed themselves into every fold of Keith's clothes and stung his face like pepper. It made the dogs look like white ghosts, while the pulling became constantly heavier. The snow- storm did not develop into a blizzard but it made travelling exceedingly difficult, and Keith was forced to direct his course almost entirely by compass.

To make matters worse he struck treacherous going: low land intersected with rivers and lakes. The lakes were fed by springs rising in their beds and these springs made thin places in the ice. Since the ice was covered with snow, it was most difficult to tell whether it was safe or not. Early in the afternoon they were crossing a lake when the ice cracked sharply beneath them. The noise was as loud as a pistol shot. Dranner, who was leading, swung to the right and sprinted. It was only this that saved them from disaster. Keith stopped his prisoner.

"Dranner, I'm taking off those cuffs. If you went in with them on, you could not help yourself. But remember that I'll be watching. I shan't take a chance in the world." Once more Keith saw that maddening half-smile on the murderer's face. And once more the man did not speak, did not utter a word of thanks. "Do you understand?" Keith asked sharply. Dranner merely nodded.

Again they mushed on. The snow fell relentlessly and they moved like ghosts through the everlasting harsh, hissing swirl. Heads bowed, they plodded on, the merciless cold biting through their furs. Fatigue was beginning to dull his senses and Keith decided that it was time to stop, camp, and call it a day. The trouble was that he could see no place fit for a camp. The stretches of land which lay between these endless lakes were flat and covered with low brush. It was absolutely necessary to find shelter and wood.

They reached the far shore of the lake on which they had experienced so narrow an escape and Keith was grateful to know that land, not water, was beneath his feet. Yet here again was nothing but brush through which the dogs toiled slowly.

The land dipped again and here was another lake or rather the arm of one. It was narrow, no more than three or four hundred yards in width. Keith paused a moment and studied the opposite shore. He could see it only dimly, the snow fog was so thick; but he could see enough to be sure that it was high and heavily wooded. Here at last was the spot for which he had been searching.

"Mush!" he cried and the dogs, sensing that their long toil was nearly over, tightened the traces and made on down the slight slope to the lake. Here the snow was not so deep, for the wind had swept it away. Presently the runners rang on bare ice and the pace quickened. Dranner was still in the lead only a few feet in advance of Koltag. They were within less than a hundred yards of the far bank when it happened. A report like that of a cannon shot rang out and Keith felt the ice moving, dropping beneath his feet.

"Mush!" he yelled to the dogs and saw them spring forward. But he plunged through a black hole into water cold as death.

AS he fell Keith managed to grasp the edge of the ice on the far side of the hole. His mittens slipped on the ice but he forced himself forward and got his elbows over the rim of the hole. The ice held and he began to struggle upwards. Then, as he raised his eyes, he saw Dranner standing, waiting for him. Through the loom of the drifting snow the murderer's grey-green eyes stared down at him, full of pitiless purpose.

So this was the end. Dranner would force him back into the water and, himself, escape with the dogs. Even so, Keith refused to give up. It seemed to him that, if Dranner came near enough, it would be possible to catch him by the legs and end his beastly life. If he could do so, Keith felt that he would not die in vain.

He dragged himself upwards. He had lost all feeling in his legs but the muscles of his back and arms still responded to his fierce effort. He got his body over the edge. The ice creaked and groaned, yet held. Dranner did not move. Now Keith saw that he had the rifle in his hands. It was not loaded, so he meant to use it as a club. In the thickening gloom Keith saw the man's thin lips twisted in a grin of anticipation. Hope died within him for it was plain that he could not reach Dranner in time to avoid the crashing butt of the rifle. Already his wet clothes were armoured with ice and his legs so helpless that he feared he could not rise to his feet.

Above the hiss of the wind-driven snow came a new sound. That of feet running across the ice.

"Hold on!" came a high clear voice. "I will help you."

With a bitter oath Dranner whirled and went off at full speed. Something came flashing into Keith's circle of vision. A human figure which threw itself flat on the ice, then flung forward a rope, the loose end of which came straight into Keith's hands.

"Be careful!" Keith cried, "the ice is rotten. Keep back."

"I know. Hold on to the rope. Have you a good grip?"

"Yes, but—"

"All right. I'm running no risk." His rescuer was up again, tying the other end of the rope to the sledge.

"Hola! Hi ya! Mush!" came the quick command. The rope tightened and Keith heard the dogs' claws scratching on the ice as they lunged forward. A moment later he lay gasping and shivering on sound ice.

"Get up!" the voice ordered. Now for the first time Keith realized that his rescuer was a boy. He tried to scramble to his feet, but could only get to his knees. The cold had him now and he was rapidly losing all feeling.

The boy caught him under the arms and lifted him and he stood swaying, dazed.

"Run!" he ordered. "Straight ahead. The shore's only a hundred yards away. Run—while you can."

Keith staggered forwards. His legs were like dead sticks. They did not seem to belong to him. Even his brain was numbed by the intensity of the cold. The boy had him by the arm and pulled him forward. The dogs, led by Koltag, followed.

By the time they reached the shore Keith's blood was circulating again and the agony of it was beyond words. The boy heard him grit his teeth. He understood.

"Our camp is quite close," he said. "You can see the glow of the fire. I told Gil to keep it up. I heard the ice break and knew what had happened."

The red glow gave Keith fresh strength. Next minute he found himself close to a great pile of blazing logs while, behind him, a tarp rigged on posts kept off the bitter wind and reflected the heat.

"Strip him, Gil," said the boy. "I'll get coffee."

He hurried towards a tent, opposite which was a second fire and Keith found himself in the hands of a slim, dark-faced breed: capable hands, for they stripped him of his frozen clothes with amazing speed and wrapped him in a thick blanket.

The boy came back with a pot of coffee. He filled a metal mug, sweetened it with half a dozen lumps of sugar and handed the mug to Keith who swallowed it with gratitude. The boiling liquid sent a glow through his frozen body and cleared his head.

"Be careful," he warned. "My prisoner is loose, and he is dangerous!"

"He have gun?" Gil questioned.

"He has my rifle but I don't know whether he has cartridges." Gil frowned.

"Name of a dog, but he is a bad one. I will be careful, Monsieur. Now I see to dem dogs."

He went off and the boy returned to the tent. It was now snowing so heavily that it was impossible to see twenty yards in any direction. Keith wondered what Dranner was doing. He felt pretty sure that he had no cartridges for the one box of rifle cartridges was in the blanket roll strapped to the sledge and the only loose ones were in the pocket of his own tunic. Without cartridges, Dranner was like a toothless wolf. Yet the man was so savage, so desperate, that Keith was uneasy.

He leaned over and felt his clothes. They were drying fast and soon he would be able to put them on again. Meantime he dried his revolver carefully and reloaded it. Gil came back and with him Koltag.

"He say he come," said the breed with a smile. "He like you, I tink."

"He's a real good friend," Keith answered. "And I'm glad to have him. If Dranner comes anywhere near Koltag will warn us. I wish I knew where the fellow has gone. I'll have to be after him as soon as my clothes are dry."

"You have supper and sleep first," Gil said firmly. "I no tink Dranner he go very far in dis storm. You stay still. I fix supper."

Keith realized that he was savagely hungry—also that he was extremely lucky to be alive. He knew, too, that Gil was right. It was now pitch dark and travelling would be impossible before daylight. If Dranner had matches—and Keith believed he had—the man would build a fire and camp until morning. But he had no food and that would drive him desperate. It was on the cards that he might be lurking close at hand, waiting a chance for a treacherous attack. Had he been alone Keith would not have minded so much, but he hated the idea of exposing these kind friends to danger. Gil broke in upon Keith's thoughts.

"Supper ready. I tink your clothes, dey dry enough to put on."

Keith quickly got back into his uniform. Everything was dry except his footwear, but Gil fished out a pair of mukluks which were warm and comfortable.

THE boy came across from the tent with plates and knives and forks.

"You all right?" he asked of Keith and Keith spotted by his voice that he was English, not Canadian. He was about sixteen, tall, slim, distinctly good-looking, the last sort of boy that anyone could expect to meet in these Arctic wilds. He might have been a Public School boy home for the holidays, but Keith knew better than that. The way in which he had rescued Keith proved that he knew the north as well as, or probably better than, Keith himself.

"I'm right as rain, thanks to you," Keith answered warmly. "You did a mighty good job pulling me out of that ice-hole, and I don't even know your name."

"I'm Randolph Arden," the boy said quietly, but did not offer any more information.

"My name is Keith Marlow," said Keith. It seemed to him that the boy started slightly when he mentioned his name but he couldn't be certain. He was quite sure that he himself had never before seen the lad. Young Arden was far too striking to be easily forgotten. Again he wondered what he and this capable breed were doing in this wilderness and where they were bound.

"Who was the man that got away from you?" Randolph asked.

"His name is Jake Dranner. He—"

"I know. He murdered Joe Pelly." He looked at Keith and his eyes shone. "And you ran him down and arrested him?"

"And now I've lost him," said Keith with a shrug.

"You'll catch him again." Young Arden leaned forward eagerly. "He has no dogs or food."

"That's the trouble," said Keith. "He may raid this camp to- night. Gil and I will have to watch."

"You won't, Mr. Marlow," the boy said with a decision which surprised Keith. "You're all-in. Gil and I will take turns to watch. If you don't get a good sleep you'll never get him. Now we'll have supper."

Gil had a delicious stew of venison with onions and tinned vegetables. This, with coffee and bread, made the best meal that Keith had eaten for many a day. Keith could not keep his eyes off young Arden. The more he saw of him the more he wondered what he was doing here at the back of beyond. He ventured to suggest that it was late in the year for travelling so far north and to ask if he could be of any help. Randolph laughed.

"You needn't worry about me. I know this country better, I expect, than you do. Just now I'm on my way to join my father."

That was all he said about himself, and Keith was left to wonder where the father had settled and what he was about. Keith had the notion that Mr. Arden must have made a rich strike somewhere in these wilds. That would be good reason for his son keeping his mouth shut.

Supper finished, Gil took the dishes and Randolph turned to Keith.

"Gil will take first watch," he said. "You can sleep comfortably. If anything happens I promise to wake you."

Those agonizing minutes in the ice-hole on top of his hard day's journey, had taken more out of Keith than he would admit. He was grateful to creep into his sleeping-bag and had hardly closed his eyes before he was asleep. Next thing he knew, Gil was shaking him gently and he started up to see a fire blazing in clear windless darkness and the breed with a mug of steaming coffee in his mittened hand.

"You spoil me, Gil," said Keith.

"You make de most of him," replied the other. "You boil your own coffee to-morrow."

"If I'm alive to do it," was Keith's thought and then he saw young Arden standing beside him, ready dressed.

"The storm's over, Mr. Marlow," he said. "Gil and I have a long march to-day, so we're starting as soon as ever we can after breakfast."

Gil had flapjacks ready and a big pan of fried bacon. They ate quickly and almost in silence. As they finished Keith spoke.

"Which way do you go, Arden?"

"North-west," the boy told him and pointed. "And listen, Mr. Marlow. There's a trapper's cabin at the south end of this lake. If Dranner knows this country, as I expect he does, that's what he'll make for."

"Any food there?" Keith asked quickly.

"I don't know. A man called Masterman lived there last winter. He went out in the Spring, but whether he came back or not I haven't an idea. We didn't pass the place on our way up. But that is where you will be likely to pick up the trail. I do hope you'll catch the chap. I'd lend Gil to guide you, but Dad is terribly short of stores and we mustn't waste an hour."

"You have done enough for me, and more than enough," Keith said warmly. "You have saved my life, fed me, and given me the best night's rest I have had since I started. I can't begin to tell you how grateful I am."

"Then don't try," Randolph said, smiling. He held out his hand. "Gil has packed. I must say good-bye."

"You'll be coming out some time," Keith said. "If you're passing through Sundance, give me a call."

"I will if I can," said the boy slowly, "but it all depends on dad. Good-bye and good luck."

Keith felt uncommonly lonely as he watched young Arden and Gil, with their dogs and sledge, pass away and vanish among the serried ranks of tree-trunks. For as much as a minute he stood gazing after them, and it was not until they were quite out of sight that he turned to his dogs to make ready for his own start. The harness was in good condition but he went over every inch of it, then carefully examined the feet of his dogs. While he worked Koltag watched him keenly. It is not usual for an experienced husky to take to a tenderfoot yet, ever since the two had first met, Keith and his lead dog had been friends. Keith had been a dog lover all his life and Koltag had brains to understand and appreciate this. Keith had come to rely upon the great dog's courage and intelligence, even more than he would upon those qualities in a human companion.

Satisfied that all was correct, Keith packed his sleeping-bag on the sledge and harnessed his team but, before leaving, took one last glance around this camping ground. A scrap of paper attracted his attention, lying close to the ashes of the fire and he picked it up.

The paper was part of an envelope of which three-quarters had been burned and, if Keith was looking for sensation, he found it. Only one word and half of another were legible.

They were "Colin Ans—" Keith stared and stared.

"Colin Anson," he said. "It can't be anything else. But what does it mean? Colin has been dead for three years."

A RED sun was rising as Keith started his dogs south along the lake shore. The snow was so deep and powdery that travel was slow. The frost was keen but the wind had dropped, and conditions were a deal better than on the previous day. With his mind full of his recent discovery he moved mechanically, with the result that he drove right into a windfall and had to turn his team round in order to get out of trouble. This gave him a shock. A sweet chance he would have had if Dranner had happened to be anywhere near! Cursing himself for such wool-gathering, he put the scrap of paper out of his mind and gave all his attention to his surroundings.

Of course there was no trail. Snow had fallen for at least two hours after Dranner's escape. But Keith was not worried on that score. He felt certain that the man had made for Masterman's shack.

The ground rose and Keith entered a stand of spruce so thick that it cut off all sight of the sky. When he had passed through this he could see the end of the lake and, in a small clearing, a building. He focused his glasses and examined it carefully. It was a solid-looking cabin of a much better type than the shack where Keith had first found Dranner, but no smoke rose from the chimney and there was no sign of life about the place. Keith tied his dogs in shelter and, taking Koltag with him, made his careful way towards the place.

Pistol in hand, he crept through the trees until he was within a few yards of the shack. Koltag showed no sign of excitement until Keith, cautiously circling round the cabin, saw the marks of rackets on the new snow. Then the great dog growled low in his throat, and Keith saw at once that the tracks were those of Dranner. He had gone straight up the slope towards the west.

Keith hurried back to the cabin. He had to know whether Dranner had found food or, perhaps, firearms. One glance was enough. Dirty dishes stood on the table, ashes in the stove were still warm. On the floor lay Keith's own rifle. The stock was smashed. He saw at once that Dranner had been unable to find cartridges for the weapon.

He made a quick search and found flour, bacon, coffee and other stores but no sign of firearms or ammunition. It seemed unlikely that Masterman had left anything of the sort behind him. Whether that was so or not, one thing was clear. Dranner had all the food he could carry and was probably using his long legs to put as much distance as possible between himself and the Law, in the shape of Keith Marlow.

Dranner had some three hours' start but that didn't make much odds. With his dogs, Keith could travel faster than a man carrying a heavy pack. What did matter was the weather. Fresh snow would cover the murderer's tracks and already the sky was darkening. Keith hurried out, ran back to his sledge and at once got on the trail of the fugitive.

The gloom increased. With despair in his heart, Keith looked again at the sky and, as he did so, a chill flake stung his cheek. Within five minutes it was snowing as hard as on the previous evening. There was one gleam of hope: there was no wind so for the time Dranner's tracks remained visible.

They ran up a long slope among sparse trees and, at the top, turned slightly to the left and led through a deep hollow between two thick stands of spruce. The pass between these clumps was narrow and it came to Keith that here was the ideal spot for an ambush. If by any chance Dranner had found a gun in Masterman's shack, here was where he would hide ready to shoot down his pursuer.

Keith halted his dogs and they, tired with the long uphill pull, at once lay down in the snow. With Koltag at his heels and pistol in his hand, Keith went slowly forward. The cloud was passing, the snow thinning, but it was still too thick to see more than a few yards.

With an inch of new-fallen snow on top of Dranner's racket- marks, the trail was not easy to follow; yet Keith managed to do so, and was surprised and relieved to find that it went straight up the centre of the hollow.

Koltag stopped and growled. Keith looked round but could see nothing suspicious. He laid a hand on the dog's back.

"What is it, boy?" he asked.

Koltag was scratching in the snow and suddenly Keith saw a thin cord hidden beneath the surface. Instantly he knew what it was.

"Back!" he ordered sharply but he was just too late; the dog's paw touched the cord.

There was a heavy explosion, Keith was conscious of a violent blow on his head and down he went, flat on his face in the deep, soft snow.

KOLTAG'S warm, wet tongue upon his cheek roused Keith. He sat up. His head was ringing and, when he put his hand to his forehead, he found blood upon his fingers. Yet the wound was little more than a scratch. The missile that had hit Keith had expended most of its force on the fur of his hood which was cut.

He knew at once what had happened. He had fallen into a trap set by Dranner, but how he had escaped so lightly was beyond his imagining.

He followed the cord into the trees on the right of the pass. Fastened firmly to a log was an old ten-bore single-barrelled gun. Dranner had arranged it so that its muzzle pointed directly across the trail. The cord tied to the trigger had been carried under the snow and fastened to a peg opposite. Any person who touched the cord must pull the trigger and receive the whole charge in the lower part of his body.

Koltag had released the trigger and fired the gun. Why then was the dog unharmed and Keith only slightly injured?

One glance solved this problem. Dranner had carefully covered the trigger with a piece of birch bark, but it had not occurred to him to cover the muzzle also. Probably he had not reckoned on more snow falling. It was this last storm which had saved Koltag and Keith. Snow had drifted into the muzzle of the gun, plugging it, with the result that, when it was fired, the barrel, thinned by age and rust, had burst. It was a fragment of metal from the broken barrel that had hit Keith.

"And I was cursing that storm," Keith said slowly as he looked at the wreck of Dranner's deadly trap.

Koltag growled and instantly Keith knew the reason. He stepped swiftly back into the trail and flung himself down on his face. Koltag, puzzled at this performance, yet in no doubt whatever as to the identity of the man who was approaching, stood over him. Barely a minute passed before Dranner came into sight, at the head of the pass.

Keith, squinting out under the rim of his parka, saw that the man's only weapon was a club. His own right hand tightened on the butt of his service revolver. Dranner came slowly nearer and Keith saw his thin lips writhe in a grin of perfectly devilish glee.

"It worked!" Dranner gloated. "I got him. And the dogs, and the gold. Jake Dranner, your luck's in!"

Koltag's amber eyes were fixed upon the murderer. All his teeth showed and the rumble in his throat was terrifying.

"Shut that!" Dranner snarled. "Shut it or I'll crack your skull." Koltag tensed. Another moment and he would be at Dranner's throat. Dranner saw this, and raised his club. Keith's hand flashed up, his pistol crashed and the club flew from Dranner's hand. At the same instant Keith came to his feet like an uncoiled spring.

Dranner's pale eyes went wide with sudden fear. Yet with the savage ferocity of the brute he was, he made a rush at Keith. Keith was sorely tempted to finish the fellow with a single bullet. He had every justification for doing so. But he resisted the temptation. Instead, he chopped down upon Dranner's head with the barrel of his heavy pistol.

One blow was enough. Dranner sprawled forward and fell, with his arms stretched straight out upon the snow.

"And that's that," Keith remarked as he took out the cuffs and snapped them upon his would-be murderer's wrists. Then he rolled Dranner in a blanket to save him from freezing, filled his pipe and sat down to wait until his prisoner recovered consciousness.

In about five minutes he saw Dranner stir and open his eyes. Keith dragged him to his feet.

"Mush!" he ordered. "Mush, you treacherous brute. And one thing I'll tell you. Those bracelets don't leave your wrists again until you're in Sundance gaol. I don't care if you drown ten times over, you don't get a second chance."

Dranner mushed. He had no choice and, during the next four days, he paid heavily for his double attempt to murder Keith. Keith never gave him the ghost of a chance to try fresh tricks and in this was seconded by Koltag, who watched the murderer night and day and was ready to fall on him if he took one step out of the trail.

The weather was brutal and when, at last, Keith with his dogs and his prisoner trailed slowly into Sundance, he was a red-eyed wreck. Duncan Maclaine saw him coming and strode out to meet him. His ankle was sound again.

"So ye got him!" was his greeting.

"Thanks to your steel chain and the boy," Keith answered.

Duncan's grey eyes widened.

"The boy," he repeated softly. "Man, ye are all-in. Get to the fire. I'll lock up Dranner and see to the dogs. The whisky's in the cupboard. It's a good drink ye need and a hot meal, and I'm thinking ye have earned it."

When he had disposed of the prisoner and kennelled the dogs, Duncan came back to find Keith dead-asleep in a chair by the stove. He noticed the gaunt, frost-blackened cheeks and the new lines around Keith's eyes and nodded sagely.

"It's made a man of him," he remarked. He stooped, lifted Keith bodily, laid him on a bunk and covered him warmly, then set to work to cook an extra special supper. And while he cooked he was wondering what Keith had meant about the boy. He himself had been long enough in the north to know the odd illusions bred by loneliness and intense cold.

It was not until supper was on the table that he roused Keith; and Keith, mightily refreshed by three hours of unbroken sleep, got up and sniffed appreciatively.

"Venison steaks, fried spuds, pie!" he exclaimed. "Gosh, what a feast! And the first meal I haven't cooked for myself since I met the boy."

"Weel, ye had better be seeing if it tastes as good as it looks," said Duncan drily. "And when ye have satisfied your carnal appetite I'll be pleased to hear where ye found Dranner and about this young fellow ye talk of."

Keith had a quick wash, then wasted no time in getting to work on Duncan's cooking. While he ate, he talked and he did not spare the telling of his own blunder when he had first tackled Dranner in the hill shack. Duncan merely nodded. It was not until Keith came to the story of his rescue by Randolph Arden that the big stolid Scot showed real interest.

"Randolph Arden," he repeated. "No, I dinna ken the name. And English, ye say?"

"English as they make 'em, Duncan. And a well-educated lad. Might be a Public School boy except that he's been up here most of his life, I'd say. He certainly knows the woods. But here's the funny thing, Duncan. I believe he knew my name for he started when I told him I was Keith Marlow. And there's something else that's funnier still." He fished from his wallet the scrap of half-burnt paper and handed it to the other. "I found this by the fire after the two of them had gone." Duncan gazed at the paper.

"Who's this Colin?" he asked. "Do ye ken him?"

"I ought to. Colin Anson is my first cousin."

Duncan frowned.

"And is this Colin in Canada?"

"He was but—wait! Colin's father, George Anson, is my mother's brother. He is a manufacturer of chemicals and a very rich man. Colin was his only son. Uncle George wanted Colin to go into the business but Colin hated towns and business. He was always mad on birds and beasts. He refused, and naturally there was an awful row.

"Colin had a little money of his own, left him by his mother. He cleared out and the next news was that he had a job as game warden in the Kootenay National Park where he was happy as a king, looking after the wild life. The only snag from his point of view was the invasion of trippers every summer."

Keith stopped to pour out another cup of coffee and Duncan remarked that Colin seemed to have more sense than his father. Keith sugared his coffee, drank half of it and went on.

"I don't know whether you'll say so when you hear what happened. Do you remember the Blackie Shard gang?"

"Blackie Shard. Aye, Blackie was hung at Regina aboot two years ago."

"Just so. He was hung for the murder of two game wardens and one of them was my cousin, Colin." Duncan pursed his lips.

"Weel, your cousin had the life that suited him. I'd have been main sorry for him gin he was still living in the smoke and dirt of they big chemical works."

"I believe you're right, Duncan," said Keith soberly. "But what puzzles me is how young Arden came to have that envelope, with Colin's name on it, two years after his death." Duncan pondered.

"I dinna think there's much to wonder at. Likely he knew him while he was warden." Keith looked thoughtful.

"But if he had known Colin, he would have been sure to hear of his people. Myself, I think he had done so, because, as I tell you, he started when I told him my name. Yet he did not say one word about Colin to me?"

"Aye, but he didna tell you anything of himself. It's plain he didna want anyone poking into his father's business. And gin his father has made a big strike yon's understandable." Keith shrugged.

"That must be it, I suppose. But I tell you, Duncan, I mean to get to the bottom of this business if I possibly can. My uncle will be keen for anything I can tell him about Colin. His death hit the old chap very hard."

"I wish ye luck, Keith," Duncan replied. He got up. "I'll be sending my report to headquarters. Light your pipe, and rest yourself." Keith laughed.

"I'm rested all right. I'll wash up. That's only fair after you've done all the cooking."

DUNCAN MACLAINE did not show Keith a copy of the report which he wirelessed to Regina, but the reply which came on the following day gave both Corporal and Constable a bit of a shock. They were told that Inspector Curtis was coming north by 'plane, that they were to hold Dranner against his arrival, and that Keith was to be ready to come south in charge of the prisoner.

"Ye are a lucky lad, Keith," said Duncan. "Ye will get a fortnight or maybe a month of civilization."

"But I thought you didn't like civilization," grinned Keith.

"I didna like the sort they keep in London or Glesca. Regina is well enough and the grub is good."

"I'm looking forward to the trip," said Keith. "Perhaps I can find out something about the Ardens." Duncan laughed.

"Noo ye can set to redding up the place. The Inspector has the eye of a hawk for a pinch of dirt."

It was three days before the 'plane, carrying Inspector Curtis, made its landing on the ice of Moose River at the edge of the town. The Inspector, a tall, slim, keen-eyed man of about thirty-five, who had the reputation of being a martinet, found no fault with the barracks and praised the supper that Keith and Duncan set before him. He made Keith tell the whole story of the capture of Dranner over again. When Keith had finished he nodded.

"You were lucky," he said drily. Then he smiled. "It was a good show. I hope you mean to stay with the Force, Marlow." Keith stared at the speaker.

"Why, of course, sir," he answered, and was amazed to hear his superior officer laugh.

"I may remind you of that promise later on," said Curtis. He paused, then spoke to Duncan.

"Maclaine, has there been any trouble among the Indians of late?"

"Not aboot this part, sir. But I'm hearing that they Kuchins are no very restful."

"You've heard the truth. Some swine has been selling liquor to the poor devils and I suspect dope. Very queer stories have been leaking down but one thing is certain, that they have been holding potlatch and devil dances. We have sent Harman and Bishop to investigate. I want you to keep your eyes open, Maclaine."

"But they willna come this way, sir."

"They might. The dope might come north by 'plane." Maclaine nodded.

"Aye, it might," he said briefly.

Next morning the Inspector, with Keith and the prisoner went south by air. It was snug enough in the enclosed cabin and, as Keith watched the frozen wilderness reel away beneath them at a speed of two miles a minute, he was devoutly grateful to be travelling in such comfort instead of the foot-slogging which had been his lot for the past weary weeks. Two nights later he supped in the well-warmed barracks at Regina and realized, with intense though well-concealed delight, that his fellows looked on him no longer as a raw recruit but as a man who had pulled off a difficult job and one which reflected credit on the Force.

He was made to tell the whole story of his arrest of Dranner and next day found that it had headlines in the local paper. On the following morning it figured in the Montreal, Toronto and Quebec papers and a lot of sly fun was poked at Keith.

But Keith had something else to think of. The kick on the shin which Dranner had given him had left a very sore place and when the police doctor examined it, he told Keith that the bone was bruised and that he must lie up for a month. So Keith went into hospital, where good feeding and rest put back on his bones the flesh which he had lost during his hard journey.

A fortnight later Keith had a letter with an English postmark and recognized the writing on the envelope as that of his uncle, George Anson.

Dear Keith [his uncle wrote],

With much pleasure I have read of your exploit in arresting this murderer, Dranner. I am not greatly surprised for I knew that you had the qualities necessary for such a task if you chose to cultivate and exert them. It seems plain to me that the discipline you have endured, as a member of the world's most-famous police force, has made a man of you.

As the son of my only sister, I had always intended to make some provision for your future, and my intention was to give you an allowance which would be paid by my trustees. I have now changed my mind and drawn up a new Will by which, at my death, you will become my heir. In the meantime you will receive an allowance of £200 a year paid quarterly, which, with your pay, should make you comfortable.

You see I take it for granted that you will remain in the Force for the present, but, if you desire to take up any other career, I shall be ready to help and finance you.

I shall be glad to hear from you if you have time to write.

lett"Your affectionate uncle,

George Anson.

KEITH read the letter through twice. He drew a long breath.

"The dear old chap," he said slowly.

He sat quite still, trying to realise his position. George Anson, he knew, was a very rich man. In spite of Death Duties he, Keith, would have an income on which he could live where he pleased. He could travel; in fact, do almost anything he liked.

"Poor old Colin!" he said aloud and just then the door opened and Inspector Curtis entered the ward, which at the moment was empty except for Keith. Keith stood up and saluted.

"Sit down, Marlow," said the Inspector kindly. "I have a piece of news for you. You are promoted to be Corporal." Keith flushed slightly.

"Thank you, sir," he said. Then, on the spur of the moment, he handed his letter to the officer. "Two pieces of good news in one day, sir," he added. "Would you mind reading this?" Curtis frowned as he finished the letter and gave it back.

"Then you are leaving the service, Marlow?"

"Not unless I'm thrown out, sir," Keith answered promptly. The frown changed to a smile.

"I'm glad, Marlow. We need men of your stamp. Stick to the Service and, with your qualities and education, you are safe for promotion. I'll see to it that you have your chance." Keith thanked him with real gratitude and Curtis left the room.

Keith's leg mended steadily and in less than a month he was on duty again. He had expected to be sent back to Sundance, but had to remain at Regina in order to give evidence at Dranner's trial which was fixed for January. So the weeks passed and when December came, he was still in barracks.

Then came a pleasant surprise. He was granted a month's leave and, since he had more than a hundred pounds in the bank, he decided to run across to Montreal. John Blanchard, who had been his great friend at school in England, was in a bank there. He sent Blanchard a wire and left by the next train.

Blanchard was delighted to see Keith, and introduced him all round. Everyone had heard of Keith's exploit and Keith was embarrassed to find himself looked upon as something of a hero. He had heaps of invitations and a thoroughly good time.

One evening Keith was one of a sleighing party which drove out to a road-house at Altamont for supper. It was a big place and others besides Keith's party were there.

At a table on the far side of the room sat a man who attracted Keith's attention. He was big, blond, handsome and perfectly dressed; but he had the coldest grey eyes Keith had ever seen in a human face. He sat alone and Keith could see that he was in an ugly mood.

"Who's that?" he asked of Blanchard. Blanchard glanced at the big man and frowned.

"Paul Marrable," he answered. "I don't know much about him personally, but the general opinion is that he's a nasty piece of goods."

"He looks it," Keith agreed, still gazing at the man. Just then a young fellow came hurrying past Marrable and stumbled over his foot, which was stretched out across the open space between the tables.

"I beg your pardon," Keith heard him say. Marrable glared at him.

"Clumsy young fool!" he retorted in a tone loud enough to be heard all over the room. The boy drew himself up.

"I have apologised," he said with a dignity that pleased Keith.

"And I have called you a clumsy fool," sneered the other. "What are you going to do about it?"

"This," said the boy and, picking up a napkin, flicked Marrable across the face. A dull flush rose to Marrable's cheeks. His great fist shot out; the boy crashed into the nearest table and fell limply to the floor.

Keith was across the room in six strides.

"I am a police officer," he said. "I arrest you for brawling in a public place."

"You'll have a job," sneered Marrable and struck out again with fearful force.

IT was unwise of Marrable to warn Keith that he meant to fight. It gave the latter time to duck the blow and close, Among the many things taught in modern police training, in which Keith had recently taken a course, are holds unknown to the ordinary fighter. Once Keith had obtained such a grip, Marrable, though he was three inches taller than Keith and far heavier, was helpless. He struggled desperately, but his face went white with pain and all of a sudden he fell back against the wall and slid to the floor.

"Get a rope, Jack," Keith called, but the ready-witted Blanchard had already ripped off a curtain cord.

"Ah right, Keith. You hold him. I'll tie him," he said and in a matter of moments Marrable's wrists and ankles were firmly bound. He glared up at Keith with shocking malevolence.

"I'll kill you for this," he threatened in a strangled voice.

"If you're not hung first," replied Keith drily as he got up and dusted the knees of his trousers. "How's the boy, Jack. That blow was enough to finish him."

Leech and a waiter had already lifted the young fellow on to a couch.

"He's still insensible," Leech said, "but he's breathing all right." Keith turned to the head-waiter who was standing by, with a shocked expression on his face.

"Ring up a police car and an ambulance," he ordered. "And don't worry," he added in a kinder tone. "This was no fault of yours and I'll see that there's no trouble."

"Thank you, sir," said the man gratefully, and hurried away.

The police car and the ambulance arrived together. Keith made himself known to burly Sergeant Dickson who was in charge and explained what had happened.

"Marrable," repeated Dickson. "He's a bad hat if ever there was one. Trouble is we never could get anything on him. All right, Corporal, I'll take him along. And if this lad will prosecute I reckon he'll get a stretch. Do you know his name?"

Leech spoke: "Wilson," he said, "Chet Wilson. He comes from Quebec." Dickson made a note of the names, then he and the constable hauled Marrable to his feet, cut the cord that tied his ankles, and marched him off. Marrable did not speak, but his eyes as he looked at Keith were as evil as the lidless orbs of a rattlesnake.

By this time Chet Wilson had recovered consciousness but was still in a half-dazed condition. Keith saw him into the ambulance and went with him to the hospital. He did not leave until he was told that young Wilson was not in any danger.

"He will be all right by morning," said the doctor to Keith. "The only trouble with him is slight concussion caused by the back of his head hitting the table or the floor."

Keith nodded. "Thank you, Doctor. Tell Wilson, please, that I shall be round to see him in the morning."

Before ten next morning Keith was back at the hospital to find that Chet Wilson was practically himself again. He was a good- looking youngster and Keith saw that, though slim, his muscles were finely developed. Chet put out his hand.

"I want to thank you for what you did last night, Mr. Marlow. I'm told you tackled Marrable, single-handed, and got him down. I can't think how you managed it."

"All in the way of business," said Keith with a smile. "They teach you that sort of thing in the police. Actually I enjoyed going for that big brute." He paused. "We want you to prosecute, Wilson," he added. Chet shook his head.

"I couldn't do that."

"He might have killed you," Keith reminded him.

"But he didn't, Mr. Marlow. You must see that I couldn't prosecute," he said firmly. Keith shrugged.

"I didn't think you would but we shall have him for brawling in a public place. And by the time we have finished with him he won't be able to show himself in any kind of society."

"I can't prevent your doing that," the boy answered, "but, so far as I'm concerned, this is a personal matter. I shall never rest happy until I've had it out with Marrable. One day we shall meet, each with a gun in hand. Then I shall kill him." Keith nodded.

"More unlikely things have happened but, personally, I hope that some day we shall get the goods on him and send him up for a long term. Now I must go, for Court opens at half-past ten. But I shall see you again soon."

"Do come again," the boy begged. "I may have talked like a fool but I'm really grateful to you."

When Keith saw Marrable in the dock he grinned inwardly. The big man was still in dress clothes but they were crumpled and dusty. He was unshaven. He looked as if he had not enjoyed a good night. Yet Keith had to hand it to him that he held himself well and showed little sign of the fury that must be boiling within him.

Keith, Leech, Blanchard and the Altamont head-waiter, were the witnesses, but Keith had to explain that Chetwood Wilson refused to prosecute.

The case came down to one of brawling in a public place and resisting the police. Possibly the Chief of Police had whispered a word to the judge before he took his seat for his comments were scathing and he sentenced Marrable to a month's imprisonment without the option of a fine.

"And a sweet time he'll have in prison," Keith remarked to Blanchard as Marrable was taken away.

"Nothing to what you'll have if that blighter ever gets his hooks in you," replied Blanchard. "Did you see the look he gave you before he left the dock? It was pure poison." Keith laughed.

"I'll take my chances," he said.

He was to remember that remark before he was many months older.

KEITH saw a good deal of Chet Wilson during the last few days of his leave and came to like him greatly.

On the day before Keith's leave was up, Chet came to see him in his room at the hotel and found him packing. The boy sat silent awhile smoking, then spoke suddenly.

"Keith, do you think they'd take me in the Force?" Keith laid a folded shirt in his suitcase and faced the other.

"No reason why they shouldn't unless the list is full. But this is a bit sudden, Chet."

"It isn't. I've been thinking of it for three days past and I spoke of it to my mother. She was quite pleased."

"It's a hard life," said Keith.

"It's a man's life," Chet answered. "I'd go to seed in an office. See here, my notion is to come to Regina with you and see if I can enlist right away." Keith nodded.

"So long as your mother approves I've no objection. Can you be ready for the night train?"

"I'll meet you at the depot," Chet said and went off.

There are always plenty of candidates for the Royal Regiment, which now numbers 2,500 men and 300 officers; but recruits of the quality of young Wilson are not too plentiful. On arrival at Regina, Keith went straight to Inspector Curtis and told him all about Chet. Curtis himself interviewed the boy and approved of him, and next day Chet was sworn in and began to learn his drill.

Chet had the advantage of having been a member of the cadet force at his university and of being able to ride well. He also had his pilot's certificate. The result was that within a few weeks he was out of the rookie class and put on regular duty. Keith was pleased to see that Chet was popular with the other men and that he was gaining weight and strength rapidly.

Even after Dranner's trial and conviction Keith was still kept at Regina and this puzzled him for he had expected to be sent back to Sundance. It was not until the end of March he learned the reason for the delay. Then Curtis told him that no news had come from Harman and Bishop and that he was to go up to the Kuchin country and find out what had become of them.

"I am sending you, Marlow," said the Inspector, "because you have been on the edge of that country while in pursuit of Dranner, and because I think you have the tact needed to deal with these Indians. I have no doubt whatever that they have been getting whisky and probably drugs. If you can discover and arrest the scoundrels who are trading with them, you will have done a very real service."

"I'll do my best, sir," Keith said quietly.

"I'm sure of that. Now you must have another man with you. Have you any preference?"

"May I have Wilson, sir?"

"Wilson! But he is still only a recruit."

"All the same I would rather have him than anyone else," said Keith earnestly. "I know I can depend on him." Curtis smiled.

"Yes, I know what you mean. Very good. You can take Wilson and the sooner you get off the better."

Chet's face glowed when he heard that he was to go with Keith.

"I never dreamed of such luck. It's frightfully good of you, Keith." Keith laughed.

"You may change your mind before you're much older, Chet. It's no fun travelling at this time of year. We shall be bucking the spring blizzards after we leave Edmonton."

"I won't let you down," Chet promised. Keith clapped him on the shoulder.

"I wouldn't have asked for you if I'd thought you couldn't stick it," he said. "Now pack up. We leave in the morning."

There was no flying this trip. The first part of the journey was by rail through Edmonton to a post called Mackay. There Keith and Chet spent three days making preparations for their journey. They left with a team of six good dogs and a well-loaded sledge, and pushed north-west on their way to Sundance.

For the first few days Keith took it easy. This was partly for the sake of the dogs and partly on Chet's account. March is one of the coldest months in the north-west and, with a temperature of 20° to 30° below zero, there is always the risk of a greenhand getting his lungs frozen if he is driven too hard. For another thing there is much trail lore that cannot be learned in barracks and Keith had to teach Chet a dozen lessons: how to handle the dogs, how to break trail in soft snow, how to choose the proper spot for a camp, how to build a cooking fire and another that will last all night.

He could not have found a better pupil. Chet had a quick brain and rarely forgot anything after once being shown. He was good with the dogs and, in spite of his rather slight physique, was tough and tireless. Keith found too, that he was a marksman. With a rifle he was better than Keith and he was distinctly useful with a revolver.

Best of all, from Keith's point of view, was the steady good nature of his companion. The discomforts of travelling in extreme cold are so great that tempers are apt to fray, and men quarrel easily and sometimes reach a point where they no longer speak to one another. Chet had naturally a quick temper but had self- control and a keen sense of humour, so he and Keith got on famously together.

In camp at night they sat over their fire and talked and so came to know each other extremely well. Chet was tremendously keen for the success of their expedition and asked endless questions about the Indians they were visiting and the scoundrels who sold spirits to them. He wanted to know what these white men got in return for the big risk they took in breaking the Liquor Control Act.

"Furs," Keith told him. "White men are not allowed to trap on Indian reservation and the Indians, who are usually good trappers, get a wealth of fur. A sober Indian knows the price of his furs as well as any white man and gets it either from travelling fur buyers or from the nearest Hudson Bay Post. But the average Indian will sell his soul for whisky; so, for the price of a sledge load of rotgut spirit, these dope merchants acquire twenty, thirty, even fifty times its value in furs." He stopped to relight his pipe, then went on.

"But the damage is worse than that. Give the Indians drink and they don't work. Then they face the winter without fuel or food. All suffer, especially the squaws and children. I've been told, and I believe it is true, that sometimes the wretched people are driven to cannibalism and eat their own children."

Chet shuddered. "How can men be such brutes?" he asked. He paused then went on. "Keith, they said that Marrable was mixed up in the dope traffic. Do you think it is possible that he has anything to do with this gang?" Keith took his pipe out of his mouth.

"It's possible, Chet. The police in Montreal told me that all this dope business in Canada is controlled by one ring. But don't get the idea in your head that we are going to run into Marrable up here in the wilds. That gentleman is too fond of his creature comforts to rough it up here."

"I'm not so sure," Chet said slowly. "Don't forget that they use aeroplanes. Remember, too, that Marrable can't live any longer in Montreal."

FROM headquarters at Edmonton North to the Arctic Sea and west to the borders of the Yukon territory lies the so-called "G" division of Northern Alberta. It covers an area larger than the British Isles, France and Germany put together, and is controlled by 120 Mounted Police whom Whites and Indians alike look to as the Law.

This is mainly a country of tundra, muskeg, lakes and rivers, but to the west it rises to the slopes of the Rockies in a tangle of hills, valleys and swiftly-running creeks.

It was in this direction that Keith and his partner marched through the cruel cold of the last part of the Arctic winter. Now and then they crossed the trails of other mushers and twice they stopped for the night at police posts. Apart from that, they never set eyes on a human being.

But on the very morning after the talk mentioned in the last chapter, a 'plane came over. A single-engined cabin monoplane fitted with skis for landing on ice. They stopped and gazed at her, expecting at least a wave from her occupants. But there was no sign and she soon dwindled to a dot, then swept out of sight.

"Think those are our dope merchants?" Chet asked. Keith laughed.

"You have those fellows on your brain, Chet. The odds are that the machine is taking stores and mail to some mining post."

"It wasn't a mail 'plane," was all that Chet said.

As the days passed they travelled faster. The dogs, as well as they themselves, had become trail-hardened and, with the diminishing of their supplies, the load on the long komatik sledge grew less. They came to the mountains, and the going grew worse. The snow was like powdered ice and every yard of trail had to be broken. Then came the first bad storm since leaving Mackay and they were forced to hole-up in a clump of willows for thirty hours until it blew over. That day they did not get started until afternoon so, as the moon was nearly full, decided to push on for a couple of hours after their usual camping time.

Progress was slow at first for the fresh snow was piled in great drifts along the hillsides, but presently they came to a slope where the wind had almost cleared the ground. Suddenly the lead dog, a steady old fellow called Starek, lifted his head and growled. Keith looked round sharply and saw two dark forms merge from the brush above the trail. Then a couple more showed on the other side.

"Wolves," Keith said to his companion as he stooped to get his rifle from the load.

"But only four," said Chet.

"Four!" Keith repeated. "More like forty. Look round!" Chet looked and, sure enough, many other slinking forms were now visible behind the sledge.

"Gosh, you're right. I say, are they going to tackle us?"

"Looks like it," Keith replied. "See how they're spreading out to head us off."

"Well, I'll be darned! I always thought these yarns about wolves attacking people were bunk."

"So did I until I had the real stuff from some of the old- timers."

"Then what do we do now?" Chet asked, and Keith was secretly pleased that the boy's voice was as steady as his own.

"Push on, I think. We can't stay here with all this bush round us. If we can make those rocks"—he pointed as he spoke to a mass of rough boulders lying at the foot of a bluff a mile or so ahead—"we ought to be able to hold them off."

"But won't they rush us if we run away?"

"They may, but I have a trick up my sleeve—one that Duncan Maclaine showed me." He began to uncoil a long rope to the loose end of which he attached a small piece of tarpaulin; the other he fastened to the sledge.

"Ugh, how the brutes howl!" Chet muttered, but as Keith called to the dogs and the sledge started, the wolves ceased howling and, bunching together, followed.

The way was downhill, the dogs travelled fast, but the wolf pack came on at an easy lope. Yet they kept their distance. A wolf is the most suspicious of beasts and that long rope twisting and curling over the snow held them off.

"It works!" Chet cried. Keith did not answer. He was not easy in his mind for now they were coming to lower ground where the snow was deep and soft. When the dogs struck this heavy snow the pace slackened and the rope dragged instead of dancing. The wolves came closer. They had fanned out in a wide semicircle and were yapping like hounds on a trail. Keith stopped and swiftly pulled off his gloves. The frost stung his bare hands and he wasted little time in aiming his rifle at the nearest wolf.

With the ringing report the brute shot up in the air, came down sprawling and instantly the rest of the pack gathered and fell upon him, tearing him to pieces.

"Good business!" Chet called out, but Keith said quickly:

"Save your breath. The worst is to come. Take the rifle and try to shoot a couple more. But don't get your hands frosted."

It was amazing how quickly the pack finished every fragment of the dead wolf, bolting even the bones. As Chet raised the rifle he could see the gleam of their eyes and the saliva dripping from their yellow fangs. He fired and a wolf rolled over. As the others mobbed it Chet shot two more.

Keith's whip snapped and this time they gained a good distance before their enemies came again. But the snow grew deeper and now it was all uphill to the rocks. The pack had gathered and were close on their heels. The wolves had tasted blood and were out for a kill. Chet pulled up and turned.

"Go ahead with the dogs, Keith. I'll hold them," he said.

"HOLD them! You're crazy," Keith retorted. "You'd need a machine-gun to stop them, once you were left alone, and I doubt if you'd do it with that. But if you'll use your pistol and fire spaced shots I'll show you a trick."

Keith had stopped the dogs and the wolves, which had already finished their dead companions, paused at sight of the two figures facing them. Yet they were closing in all the time, crawling up through the snow on their bellies. Chet began to shoot again and although the moonlight was treacherous he made good practice. He was cool as though target shooting and few of his cartridges were wasted. He noticed with inward dismay that the pack no longer wasted time or energy in devouring their dead; they were anticipating a sweeter meal.

Keith meanwhile was busy. He had taken from the load something that looked like a length of yellow cane and thrust this inside his clothes under his armpit. He then found a length of coarse, stiff string. It was fuse, and the stick was dynamite. But the dynamite was frozen hard and he had to wait until it was thawed.

Crang! Crang! Each explosion of Chet's revolver sent echoes crashing from the bluff beyond and almost every bullet reached its mark. Despite the slaughter the pack advanced and, for the first time since the beginning of this battle, Chet felt a chill of real fear. Such vicious and relentless pertinacity on the part of wild things was terrifying. Yet he kept his head, and when his own pistol was empty swiftly snatched Keith's and continued his measured firing.

"All right!" came Keith's voice. "Stand aside, Chet!" Keith had struck a match and touched it to the fuse. As the fuse began to sputter he drew back his arm and flung the missile right into the centre of the bunched pack. The beasts sprang aside but, before they could reach a safe distance, there was a glare of fight, a loud thump and up shot a column of yellow smoke mixed with flesh, hair and even whole bodies. With howls of terror and agony the survivors bolted at full speed. Chet drew a long breath.

"You're good at tricks, Keith. I think that one saved our bacon." Keith laughed.

"Don't talk of bacon until it's in the pan. I'm starving." He called to his dogs and presently the two were making camp among the boulders under the bluff. They kept a good fire going all night and saw no more of their late enemies.

Three days later they reached Bramble Lake, on the shore of which was a shack belonging to a trapper named Culver. Culver, a heavily-built, bearded man, lived alone and was delighted to see some company.