RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

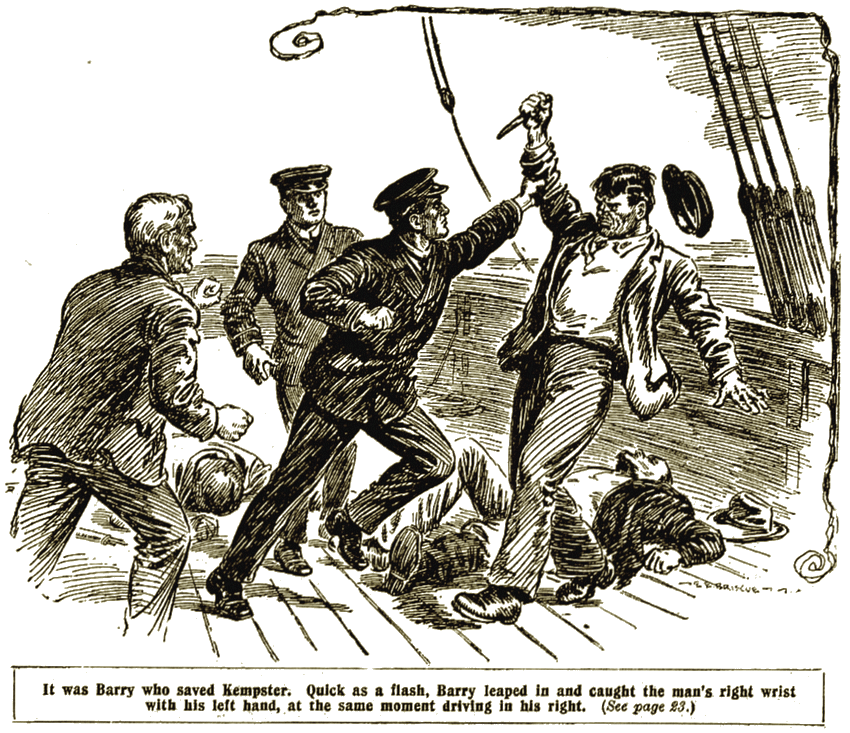

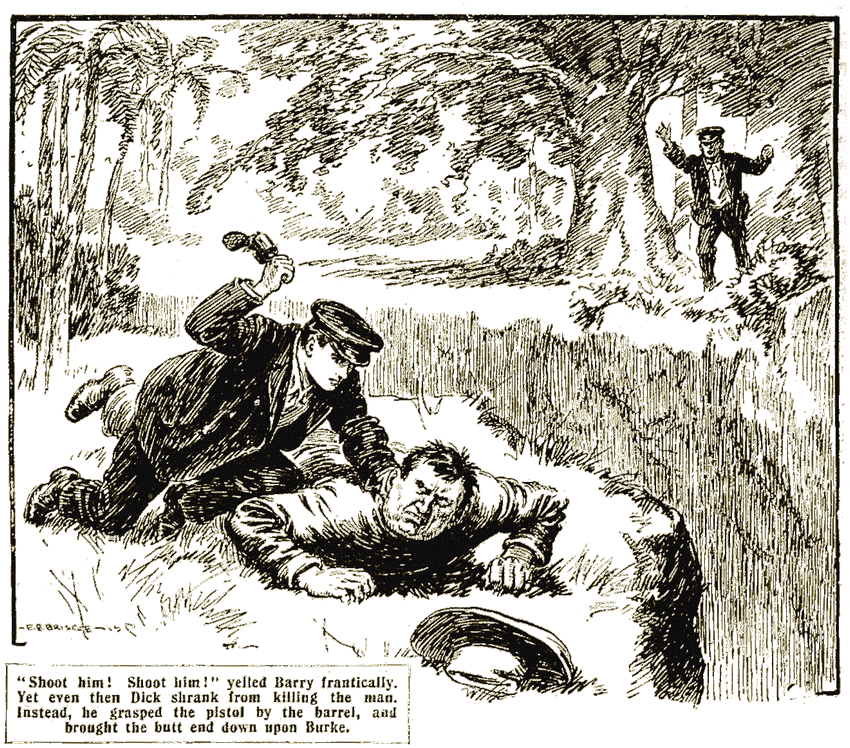

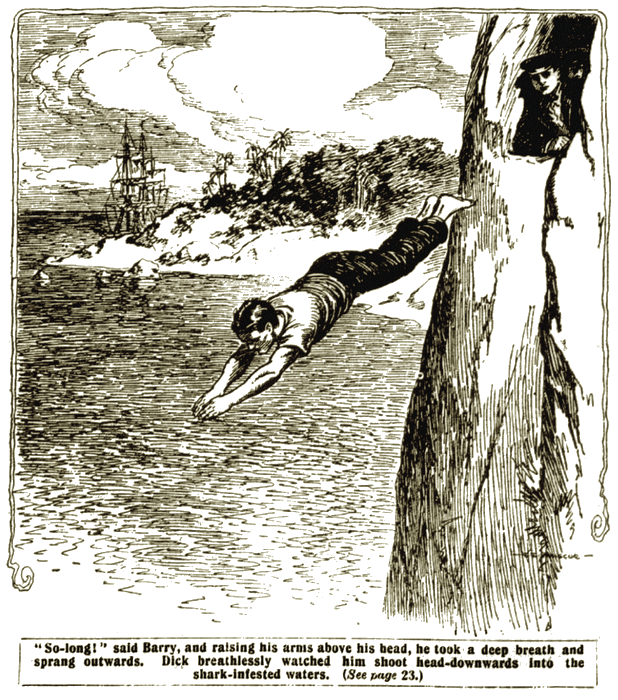

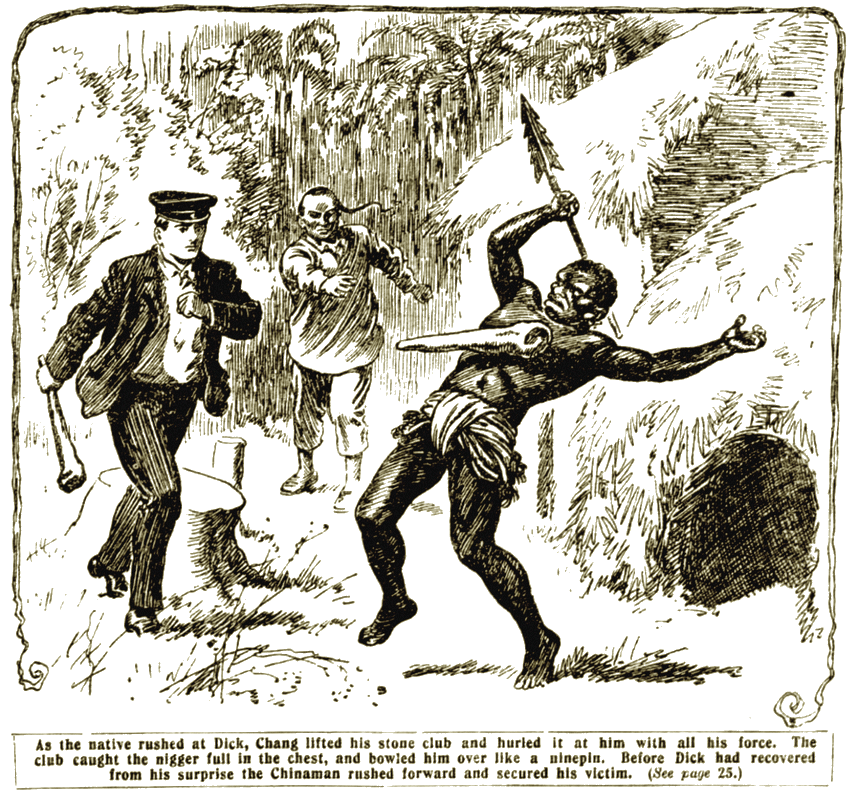

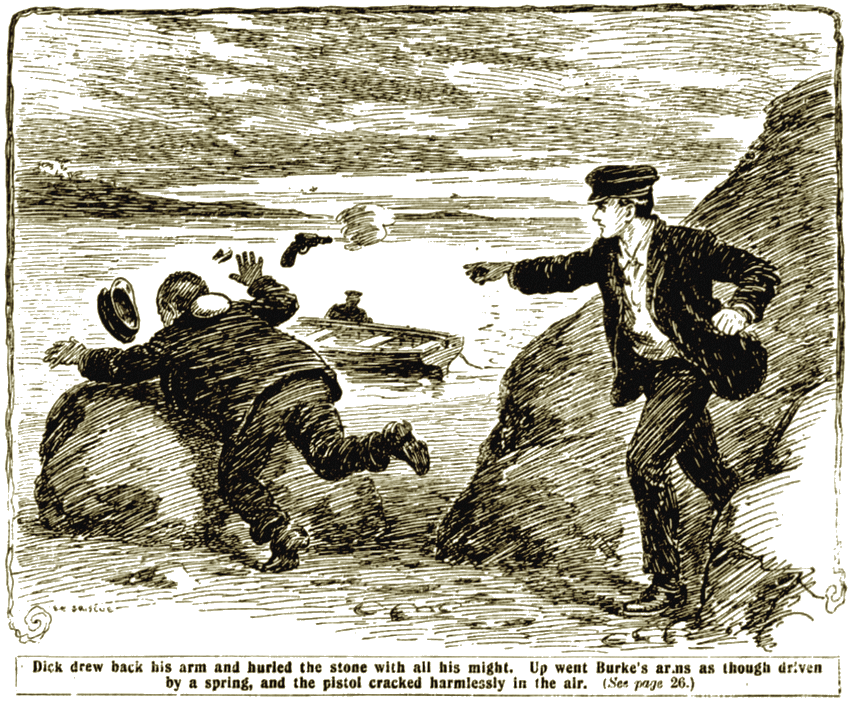

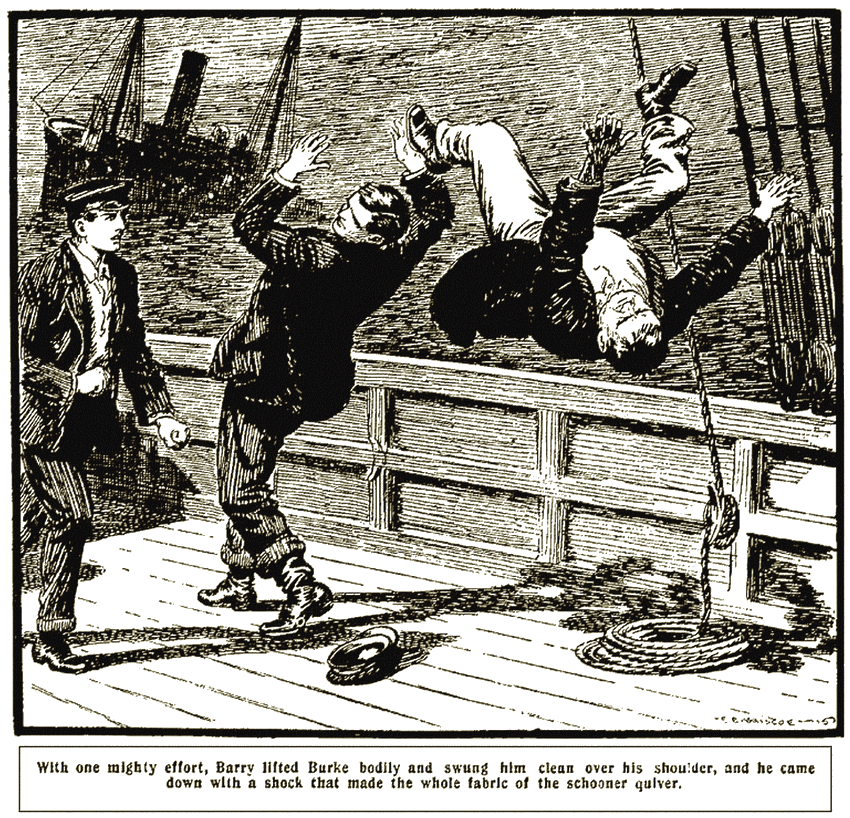

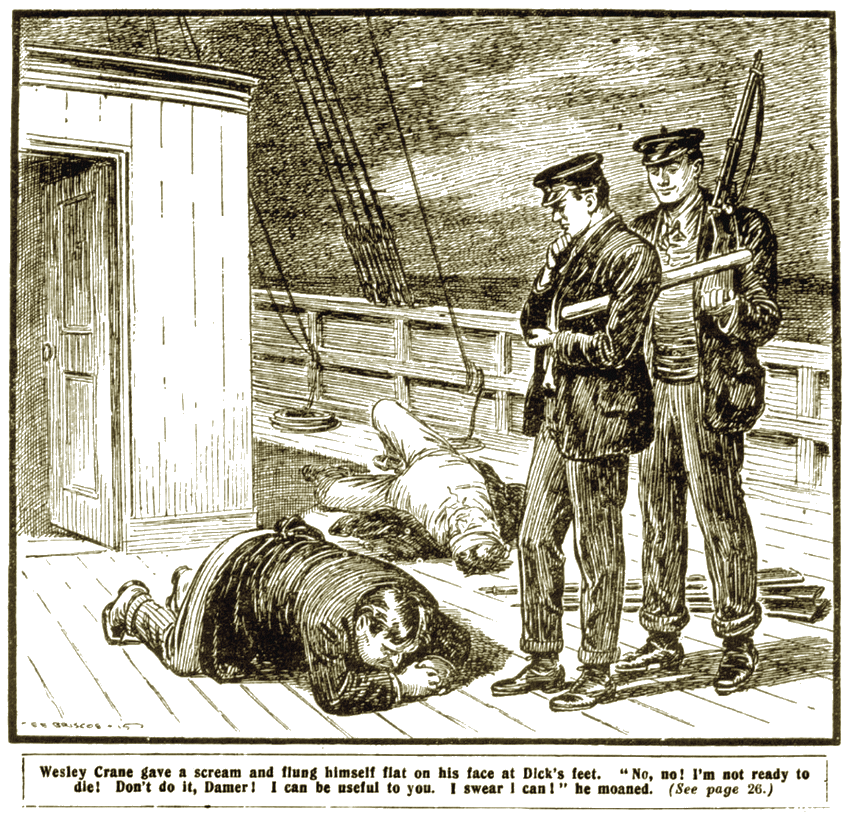

The Magnet Library, 12 June 1916, with first part of "Driven to Sea!".

Headpiece from "The Magnet Library," 12 June 1916.

"SHAKE a leg, you yellow-faced baboon! Up with it, or, by thunder, I'll come and make you!"

The tone was worse than the words, and Dick Damer paused in the act of stepping out of the blazing Australian sunshine on to the wide, cool verandah of Warlindi, and stood with a startled expression on his pink-and-white face.

There came a bumping as of furniture being moved inside the house, and a panting sound.

"Got it up at last, have you?" snarled the same voice. "Put it down and fetch the rest. Be smart, or—

The throat that followed will not bear repeating, and Dick went rather white. For a moment he was on the point of turning tail and bolting back the way he had come.

But he had travelled half-way round the world to reach this particular house, and in spite of his spick-and-span, pink-and- white appearance, the boy had plenty of pluck.

He paused, drew a deep breath, then seized the bell-handle and gave it a nervous jerk.

There was a long pause—so long that Dick's hand moved again towards the bell. But before he could ring a second time the door opened.

Dick saw a heavy, bloated-looking man, with a fat, flabby face and thick, black hair and eyebrows. His clothes were black, so was his tie; even his finger-nails shared in the general mourning. He looked like a funeral mute off duty.

"Who are you?" he asked, in a thick, husky voice. "What do you want?"

"I—I'm Richard Damer," stammered Dick. "I have come to see my uncle—my uncle—Nicholas Damer."

The other turned up his eyes with a sanctimonious expression.

"You are too late, my young friend. I regret to say that you are too late. Mr. Darner passed away last Tuesday week."

Dick's jaw dropped.

"Dead!" he gasped. "You don't mean to say he is dead?"

The fat man shook his big head and sighed heavily.

"Alas, it is too true! He had been ailing for a long time, but the end came very suddenly. I was with him to the last."

"Did—didn't he leave any message for me?" Dick managed to ask.

The other shook his head.

"He never mentioned you. I never even knew that he had a nephew."

"B-but he wrote to me to come out," said Dick. "Here's his letter. He said he would give me work, and that I could live with him."

"I know nothing of that. He never spoke of you to me. I was his partner. Crane is my name—Wesley Crane."

Dick could find no words. He was too staggered to speak.

Wesley Crane watched him with an odd expression in his prominent eyes.

"You've come from England?" he asked presently.

"Y-yes; in the Baramula. I only got in this morning."

"Then you're staying in Sydney?"

"I'm not staying anywhere. I left my box at the wharf, and came straight up. I—I couldn't afford to stay at an hotel."

Crane wagged his great head again.

"Ah, very sad! Well, I can't ask you to stay here. This place is to be sold, and I am busy taking an inventory. But since you are my late partner's nephew, I will do what I can for you."

He took out a pocket-book and scribbled a few words on a leaf, which he tore out.

"Here is the address of a friend of mine who will put you up for the night. To-morrow come to my office in Water Street, and I will see what work can be found for you."

Dick was touched.

"Thank you very much!" he said gratefully. "It is very kind of you indeed."

Crane put out a thick, grimy hand.

"That's all right," he said. "Well, I'm busy now. Good-bye!"

Dick's head was in a whirl as he tramped back down the long white road in the hot glare of the Australian sun. He was sixteen, but looked younger. That was the fault of Miss Emma Neate, the aunt who had looked after him since the death of his parents, eleven years before. She had never sent him to a boarding-school, and the result was that, though a well-grown youngster, he had precious little idea of fending for himself. He knew rather less of the world than the average boy of twelve.

Miss Neate herself was not much better, and it was pure ignorance on her part that had caused her to invest most of her money in a wildcat mining scheme. When it failed, and she was left with barely enough to live on, she had jumped at the chance offered to Dick by his Australian uncle, and sent him straight out to Sydney by the first ship.

The news of his uncle's death had shocked Dick, but as he had never seen him, he naturally did not feel any particular grief. The one question which filled his thoughts during that long walk back to the tram-head was whether the soft-spoken Mr. Wesley Crane was the same person whom he had heard using the appalling language which had greeted his ears at his first approach to Warlindi.

It hardly seemed possible, yet there were ugly doubts in Dick's mind. Of one thing he was quite sure. He did not like the man, and dreaded the prospect of working for him.

At last he reached the tram. By this time he was pretty well played out. He fell asleep in a corner, and woke to find the tram at rest and the conductor shaking him by the shoulder.

"All change, sonny. This here's the terminus."

Dick jumped up with a start. He took the address from his pocket.

"Can you tell me where this is?" he asked.

The conductor glanced at it, then at Dick.

"Bendigo Hotel, Wharf Street. Be you staying there?"

"Yes; just for the present. I was told to."

The conductor grunted.

"'Tain't much of a place. Still, I suppose you knows your own business. Go straight down that street till you gets to the water's edge, then second turn on the right."

Dick thanked him, and walked on. The sleep had refreshed him, but he was desperately hungry. Passing a little cook-shop, he went in and asked for a sandwich. As it was being cut he put his hand in his pocket to find some money.

He drew it out, and hastily tried the other.

A cry of dismay escaped him.

"What's the matter?" demanded the man behind the counter, in a surly tone.

"I—I've been robbed!" stammered Dick. "My purse is gone!"

"I've heard that tale afore!" remarked the other, with a sneer. "Out you gets—quick!"

This fresh misfortune fairly staggered Dick. True, the purse had only held a sovereign in gold and a little silver, but it was all he had in the world. No doubt it had been taken from him in the tram. At any rate he was now absolutely penniless. He could not even pay the few pence due on his box. Not knowing what else to do, he went straight on to the Bendigo.

This was a narrow-fronted inn standing in a dirty, noisome alley running off the wharf. Over the door was written, "John Bale, licensed to sell beer, spirits, and tobacco." The look of the place and the smell of it made him sick, but there was no help for it. He went in.

A surly-looking, heavy-jowled man in shirt-sleeves, stood behind the bar.

He eyed Dick suspiciously.

"Who are you? What do you want?" he demanded.

"My name is Damer. Mr. Crane sent me," answered Dick humbly enough. "He said I was to stay the night."

"Crane? Oh, Wesley Crane?" The man's tone became less surly. "All right. I'll fix you up. Where's your things?"

Dick explained, and spoke of the loss of his purse.

"More fool you to carry a purse! But don't you worry. I'll send across for your box. Had your dinner?"

"I've had nothing since breakfast," confessed Dick. "Take some o' them biscuits and cheese"—pointing to a basket on the counter.

"Supper'll be ready soon."

Dick helped himself gratefully. Then Bale showed him a room. It was a stuffy little cupboard of a place, and looked out on a filthy back-yard. His aunt's house had been the last word in cleanliness, and the squalor made Dick shiver. He flung open the window, and sat on the edge of the bed, feeling as miserable as a lost puppy.

He had left the door ajar, and presently heard low voices somewhere across the passage. He did not pay much attention. He was too unhappy.

It was something familiar in one of the voices that roused him, and he was up like a shot, and across the room.

"Who is he, anyway?" It was Bale who spoke, and, though little more than a hoarse whisper, Dick caught the words distinctly.

"That's no business of yours. I don't want him here, and that's enough for you!"

Dick's heart began to beat quickly. Now he was certain of the second voice. It was Wesley Crane's, and though as low-pitched as Bale's, there was an angry note in it.

"It's risky," answered Bale softly. "The cops have been giving me a heap o' trouble lately. S'pose someone seed him come in here?"

"Suppose nothing. He only landed this morning. He don't know a soul in the town, and no one knows him. You do as I say, and I'll make it right with you."

At this moment someone opened the street door. There came heavy steps in the bar. Dick heard Bale jump up hastily, and quickly closed his own door.

After a bit he opened it again, and stood just inside, straining his ears. But there was no more talk. All the same he had heard enough to make him horribly uneasy. He felt instinctively that it was himself that Crane had been referring to, and began to think that the best thing he could do was to clear out at once. But the idea of wandering about Sydney at night without a penny in his pocket daunted him, and before he could make up his mind Bale stuck his head in.

"Supper's ready!" he said gruffly. "This way!"

The dining-room matched the rest of the place, and the cloth on the table looked as though it had not been changed for a month.

"Sit down, sonny!" said Bale, as he pulled a chair up and seated himself. "Have some coffee, will ye?"

Dick thanked him.

"Milk and sugar?" asked Bale genially.

"Please!" said Dick.

The coffee was a pleasant surprise, black and strong and bitter, but far better than Dick had expected. He was thirsty, and drank nearly the whole cup, while Bale helped him to bread and a plateful of thick stew.

Dick put away two mouthfuls, then stopped and looked at his plate.

"What's the matter? Ain't it good?" asked Bale.

"It—it's all right," said Dick slowly, as he passed his hand across his forehead in a dazed fashion. "B-but I don't feel very well."

Bale watched him for a moment or two before replying.

"It's a bit hot in here. You want a breath o' fresh air."

"That's it," said Dick, in a queer, thick voice. He wondered vaguely what was the matter with his tongue. It felt too big for his mouth. There was something amiss, too, with his eyes. Bale, sitting just across from him, seemed to be growing. He became as big as a giant, then shrank slowly to the size of a dwarf.

"Come along!" said Bale briskly. "Come on outside!"

As Dick rose to hie feet, Bale opened a door at the back of the room, and led the way through a dark, narrow passage.

Dick followed uncertainly. His head was spinning in a most unpleasant fashion.

There was another door at the end of the passage. As in a dream Dick saw Bale open it.

"Here ye are, sonny!" he said, and the voice seemed to come from a long way off.

As he stumbled past, Dick felt a vigorous push from behind which sent him headlong forward. He plunged into pitchy darkness, the floor gave way beneath him, and he felt himself falling. He brought up with a stunning crash, and that was the last he knew.

DICK opened his eyes. He was still in darkness, and strange noises filled his ears. His head throbbed heavily, and for a time he was content to lie still.

Slowly he became aware that the whole place was swaying with a long, steady swing, and after a bit it came to him that he must be back in his own cabin aboard the Baramula, and that the events of the past day had been only a bad dream.

He shut his eyes tightly, and tried to sleep.

The next thing he knew a yellow light shone in his face, and, looking up, he saw bending over him a tall Chinaman in a blue blouse. His face looked as if it had been carved out of old ivory, and his left ear was missing, giving him an oddly lop- sided appearance.

"Hallo!" said Dick faintly. "Who are you? Where am I?"

The Chinaman paid no attention whatever to the question.

"Cap'n Clipps—he wantum see you."

"Captain Clipps? Who's he?"

"He tell you plenty soon. You come along o' me."

Dick sat up, which set his head swimming worse than ever. The light showed him that he had been lying on a wooden bunk in a small, low-ceiled cabin. The place was cleaner than Bale's hotel, but the reek of stale salt water, old clothes and oilskins was thick enough to cut with a knife.

As Dick's feet reached the door, there was a lurch which sent him flying, and if the Chinaman bad not caught him he would have pitched on his head against the opposite wall.

"Thanks!" gasped Dick, and then the Chinaman, keeping fast hold on him, led him out of the cabin and up a steep companion ladder.

A blast of fresh cold wind met him as he got his head above the hatch, and his bewildered eyes took in the fact that he was on the deck of a small sailing vessel, which was lying over to a stiff breeze, and tearing across the sea through the starlit darkness of a clear night.

Overhead he saw the loom of tall white sails, and on either side the foam-tipped waves, while astern streamed away a long wake, milk-white with gleaming phosphorescence.

The Chinaman gave him little time to take in his surroundings. He led him straight to the deck-house, and pushed him in through the open door.

Dick blinked in the bright light of a large swinging oil-lamp. The first thing he saw was a table. Behind the table sat the biggest man he had ever seen in his life—big, at least, so far as breadth went. He seemed perfectly square, and his face was huge and of a bright brick-red. Between his teeth was a long black cigar.

As Dick came in he took this out of his mouth and looked the boy up and down with a hard, penetrating stare.

"Waal, I know!" he growled contemptuously. "I always knowed Bale was a fool, but this here's the limit! What good d'ye think you are?" he barked suddenly, in a voice that made Dick jump.

"Are ye dumb?" he continued savagely, for Dick, sick and dizzy and bewildered, had not answered.

"Can't ye speak, ye pink-faced puppy?"

Dick flushed hotly. The insult pulled him together.

"I don't know what you are talking about!" he answered sharply. "Where am I? How did I come aboard here?"

"Wants to know where he is!" said the big man, in a tone of bitter sarcasm. "Asks how he came aboard! Wonders why we left his nurse ashore!"

He rose suddenly to his feet, and it gave Dick a shock to see how short he was compared with his enormous breadth. With one spring he was round the table, and caught Dick by the shoulder with his gigantic hand.

"See here, my lad," he said threateningly, sticking his great red face close up against Dick's. "I'll tell ye this much. You're aboard the Rainbow, and I'm the only man in her what's got the right to ask questions. You remember that if you value your health. I'm cap'n, an' you're cabin-boy, and anything else I've a mind to make you."

So far from scaring him, the captain's hectoring tone roused Dick's spirit.

"That's all nonsense!" he answered boldly. "I've been drugged and chucked on board here against my will. I demand to be put ashore!"

For a moment the captain stared as if he could not believe his ears. His red face grew redder still, his eyes looked as if they would start out of his head. Then his rage boiled over.

"Put ye ashore?" he roared. "I'll put ye ashore!"

He picked up Dick in both hands, holding him by the neck and the slack of his coat, and swinging him up level with his head as though he had been a baby, rushed out of the cabin and across to the rail. For a horrid moment Dick was certain that the brute was going to fling him overboard.

At the last moment he changed his mind.

"Thet's too easy!" he growled, and, spinning round, made for the companion. Without ado he pitched Dick headlong down into the darkness below.

"That's lesson number one!" he bellowed after him. "If you expects to live to make a man, you better not ask for number two."

As for Dick, he lay helpless and more than half stunned at the foot of the ladder. His luck had held thus far—that he had fallen on a pile of oilskins. But for that he would probably have been killed. He would certainly have broken half the bones in his body.

Next thing he knew the tall Chinaman was beside him, the lantern in his hand.

"You velly foolish," he said reprovingly. "Chang allee same wonder boss he no kill you."

"I don't care whether he kills me or not!" sobbed out Dick, beside himself with pain and rage. "I'd as soon be dead as like this!"

"You no talkee that way to-mollow," answered Chang calmly. "You sleepee one time. Feel all light to-mollow."

He helped Dick to a bunk, gave him a blanket, and left him. Dick, aching all over and miserable beyond words, lay there feeling that no would never sleep again.

But the very violence of his emotions exhausted him, and now that the schooner was well out to sea her motion became more regular and easy. Presently he dropped off, and did not wake until daylight was streaming through the open scuttle overhead.

For some minutes he lay wondering vaguely where he was and what had happened. Then he remembered, and started up.

Overhead someone was scrubbing the deck. He heard the water swishing across the planking. His throat was burning. He crawled out, put on his coat and boots, and moved towards the ladder.

Just then Chang appeared, coming down.

"Feel all light?" he asked and though his face and voice were wooden as ever, Dick felt there was a gleam of kindness somewhere behind.

"I'm better, thanks." he said. "Could I have a wash and some water to drink?"

"Plenty water in sea. You go topside, dlaw a bucket. Cap'n Clipps he still asleep."

Dick went on deck. It was a beautiful morning. The breeze had fallen light, but the schooner, with topsails set, snored through the clear blue waves. No land was in sight.

The only people on deck were three Chinamen—one at the wheel, the other two busy scrubbing and cleaning.

Dick drew a pail of cool sea water, stripped to the waist, sluiced himself well, and felt fifty per cent. better. He was going to put on the same clothes again, but Chang called him below and gave him a suit of blue dungaree which was not much too big for him.

He had just finished changing when breakfast was brought in—broad, fried pork in a mess-kid, and a black liquid which bore some faint resemblance to coffee, though it smelt chiefly of molasses.

Six Chinamen, including Chang, shared the meal with Dick. They ate in absolute silence, and seemed to take no more notice of the white boy than they did of the hideous brass joss which stood at the end of the fo'c's'le with a couple of punk-sticks burning before it.

Chang, who seemed to be cook, picked up the empty kid and bread- pan, and vanished silently. The others went on deck, leaving Dick alone.

Presently Chang came back.

"Hey, boss he want you. Talkee him one piecey. Sabee?"

Dick's heart sank, but he comforted himself with the thought that nothing could be worse than last night, and anyhow, he was feeling more like himself again.

He found Cripps in the cabin aft. The big man surveyed him with a sardonic grin.

"Still feelin' gay, sonny—eh?"

"Not particularly," answered Dick.

"Thet's right. It don't pay for kids like you to get giving back- talk to their skipper. Savvy?"

He waited for this to sink in, then continued:

"See here, young feller, you listen to me. I ain't altogether angry because you stuck up ter me last night. Show's you've got something back o' that pink-and-white baby face o' yours. D'ye know anything about a ship?"

"Nothing," confessed Dick.

"Ye don't look as if ye knowed much about anything, and that's the truth," said Cripps, grinning again. "Still, ye can learn, and I'm the man to learn ye. I'm a-going to learn ye, too, whether ye likes it or not, so you make up your mind to that. We don't keep no loafers aboard the Rainbow. Now, you mind what I say, and do what I tell ye, and this cruise'll be all right for you. But get gay again, and I'll make ye wish ye'd never been born!"

"I don't seem to have much choice!" said Dick bitterly "I've got to make the best of it!"

Cripps glared a moment, then burst into a loud laugh.

"You got sense all right. Now go forrard and help Chang peel the spuds. You'll learn galley work fust, and then, if you're good, I'll teach ye navigation. Git!"

Dick got. He felt he would a deal rather peel potatoes in Chang's company than remain aft with the formidable Cripps.

The next few days passed quietly enough. The weather remained perfect, and the Rainbow's crew hardly needed to touch a rope.

They were all Chinese, and the most silent lot imaginable. They talked among themselves, but except Chang hardly any said one word to Dick.

The Rainbow herself was a beamy, powerful craft of about 120 tons. But what her job was or where she was bound Dick had not the foggiest notion. He tried to sound Chang, but all the answer he got was:

"Boss, he tell you when he get leady."

On the fourth day the weather changed. The breeze fell light, and it turned blazing hot. It was a stinging, steamy heat which made Dick feel as if he could not breathe. The pitch grew soft in the deck seams, and the crew went about their work stripped to the waist.

About eleven in the forenoon Dick, who was sitting in the door of the galley cutting up meat for the soup, heard a sudden shout from up forward.

"Hyah! Hyah!"

Chang, who was in the galley, jumped out. At the same moment Cripps, who had been lying in a long chair under the awning aft, sprang to his feet.

"What's up?" he bellowed. "What's biting you, ye blamed galoot?"

He hurried forward as he spoke.

"What is it, Chang?" asked Dick eagerly.

"I tink um ship," answered Chang, who was staring out to sea, shading his eyes with both hands from the brassy glare.

"Ship! Where?"

Chang pointed, and presently Dick caught sight of a craft of some sort which, to his inexperienced eyes, was a mere blur on the throbbing horizon.

Meantime, Cripps, up in the bows, was staring at the vessel through a pair of glasses. A little knot of Chinamen stood silently around.

Cripps lowered his glasses. There was a look of excitement in his face which Dick had never seen before.

"Port—port your hellum!" he shouted to the man at the wheel.

The Rainbow came round with her bows pointed straight for the distant vessel. At that moment a puff filled her sails and the water began to bubble under her forefoot.

"What is it, Chang?" asked Dick. "Why are we going to her?"

"I tink um leck," answered Chang. "What call derelict."

DICK ventured forward. Cripps was still gazing fixedly at the strange ship, which was now rising rapidly into sight.

"She's in trouble," Dick heard the skipper mutter. "She's in trouble; I'll swear to that. Ay, that's her ensign upside down at the mizzen. Wish my eyes was better."

He glanced round and saw Dick.

"Here you! Your eyes are better than mine. Take a hold of these glasses."

He handed them to Dick, who, after one or two efforts, managed to focus them.

"What's the two flags on the boom, aft?" demanded Cripps.

"One's square," said Dick. "It's red and white. The other's pointed and the same colours."

Cripps brought his great hand down with a slap on his leg.

"Thought so!" he cried joyfully. "That means 'in need of assistance.' Now see if you kin see if there's anyone aboard."

"No, sir. I can't see anyone. There are no boats, either."

"Derelict—derelict! That's what she is. An', by gosh, there'll be pickings!" Cripps' great red face shone with a savage eagerness. There was a queer gleam in his eyes. He looked so different that Dick stared at him in amazement.

"Sonny," said Cripps, "ye got eyes if ye ain't got sense. An' ye talk English, which these Chinks can't do. I'll take ye along, derned if I won't."

Dick did not answer, but a shiver of excitement ran through him. He was beginning to understand now. He knew what salvage meant. He realised that, if this ship had been abandoned by her crew, the Rainbow, by taking her into port, could claim a heavy sum from her owners.

Soon they were close enough to view her without glasses. She was a square-rigged ship of about a thousand tons, and stood high in the water. There was no sign of life about her, and she rolled listlessly to the long send of the slow Pacific swell.

"What did they leave her for?" growled Cripps, in a puzzled tone. "Why did they leave her? There hasn't been no weather. Her masts is all standing."

As Dick had no ideas on the subject he did not venture to reply. The Chinese crew were equally silent while the Rainbow, little more than drifting before a succession of cat's-paws, slowly bore down on the derelict.

Suddenly Cripps woke up and began to roar out a succession of orders.

The crew fled to obey, and a minute or two later the schooner was lying to, head to wind. A boat was rapidly lowered, and with Cripps at the tiller, Dick in the bows, and two of the Chinks pulling, drove rapidly across the calm swells towards the derelict.

"Look!" cried Dick suddenly. "What's that?"

A brown triangular something had suddenly cut the water between the boat and the abandoned ship.

"Gosh, it's a shark!" said Cripps. "Ay, dozens of 'em. There's dead folk aboard. The sharks know."

In spite of the heat Dick shivered. In all his sheltered life he had never so much as seen a dead man.

As the dinghy drew up towards the stern of the derelict, Dick saw her name emblazoned on the taffrail. It was Kauri. Coming nearer, he suddenly caught a whiff of some powerful odour—a whiff so rank it made him almost choke.

"She—she's afire!" he gasped.

"No, she ain't," cried Cripps, smiting his thigh again. "No, she ain't. That's not smoke. It's gas. Ay, I've got it now. Carboys broke loose down below. Carboys of acid. That's it! No wonder it drove the chaps off her."

It was a job to board her, she was rolling so, but Cripps managed to catch a bight of rope hanging over the rail, and swung himself up.

"Here, you, Dick, you come aboard! Others stay in the boat. Sharp, now, kid, unless you want to make a meal for one o' them long-toothed gentry!"

Dick's heart was in his mouth as he followed, and he bruised his shins cruelly as he scrambled over the rail.

Once aboard, the reek was simply suffocating and the heat like that of a furnace.

Cripps glanced round the empty decks.

"She's abandoned, sure," he chuckled. "Oh, it's a windfall—a proper windfall!"

He hurried forward to the hatch. The cover was on, but he whirled it off. The gas poured out in suffocating clouds, and he staggered back.

"Let it blow out. It'll be all right in a minute," he gasped. "Here, you Dick, find an axe and burst open that forward hatch!"

Dick ran into the deck-house. There were axes in a rack on the wall. He got one out, and was turning when there came a sound which startled him so that he as nearly as possible dropped his heavy weapon.

The sound was a groan, and it came from quite close at hand.

Next moment he had turned up the cloth over the table in the middle of the room, and was looking down into a pair of open eyes.

"So there's one alive after all!" he gasped, and, getting hold of the owner of the eyes, who was lying between the table and the wall, he dragged him out into the open.

By his weight he thought he was a grown man, but when he got him into the light he saw that, though big and heavy framed, he was only seventeen or eighteen years of ago. He was a tall, finely- made young fellow in brown jeans, with the bluest eyes Dick had ever seen, curly hair of a chestnut red, and a heavy square jaw.

"What the blazes have you got there?"

Cripps's voice made Dick start.

"A boy. He's alive!"

Cripps swore savagely. Then his face cleared.

"It's all right." he said, in a tone of relief. "Only a cub of a cabin-boy. He can't interfere with our salvage. If I thought he could I'd—" he did not finish his sentence, but Dick shivered inwardly as he realised that the captain of the Rainbow would stop at nothing which lay between him and his prey.

"Call one o' them Chinks up, and get the chap aboard the schooner," ordered Cripps. "Sharp now, while he's still looney with the gas. Less he knows of all this the better."

Dick obeyed. As he went back to the stern he saw Cripps, with a handkerchief over his face, make a bold plunge down the companion.

It was no easy job lowering Dick's almost insensible find into the dinghy. But they did it at last, and pulled back to the schooner.

The crew of the dinghy took her straight back to the Kauri, but as Dick had had no orders to return, he stayed to look after the youngster. Chang and he between them got him below and laid him on a bunk. Chang fell his pulse and bathed his face with cold water.

"He all light pletty soon," observed the Chinaman.

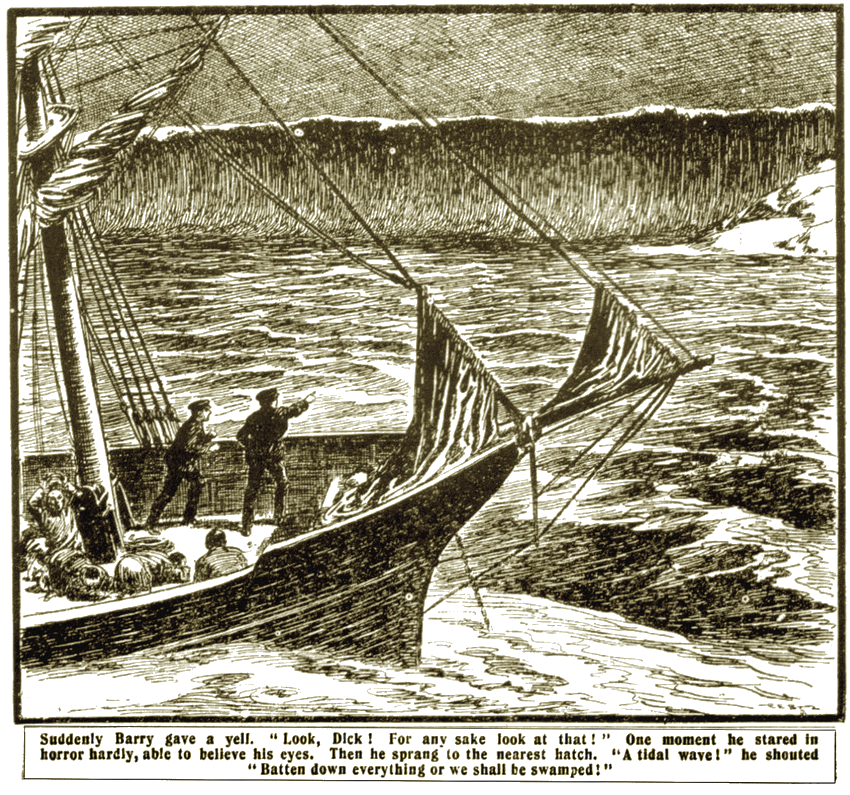

The words were hardly out of his mouth before there came a curious deep booming sound which seemed to come from everywhere at once, yet from nowhere in particular. It rose with startling suddenness, growing from a drone to a high-pitched shriek.

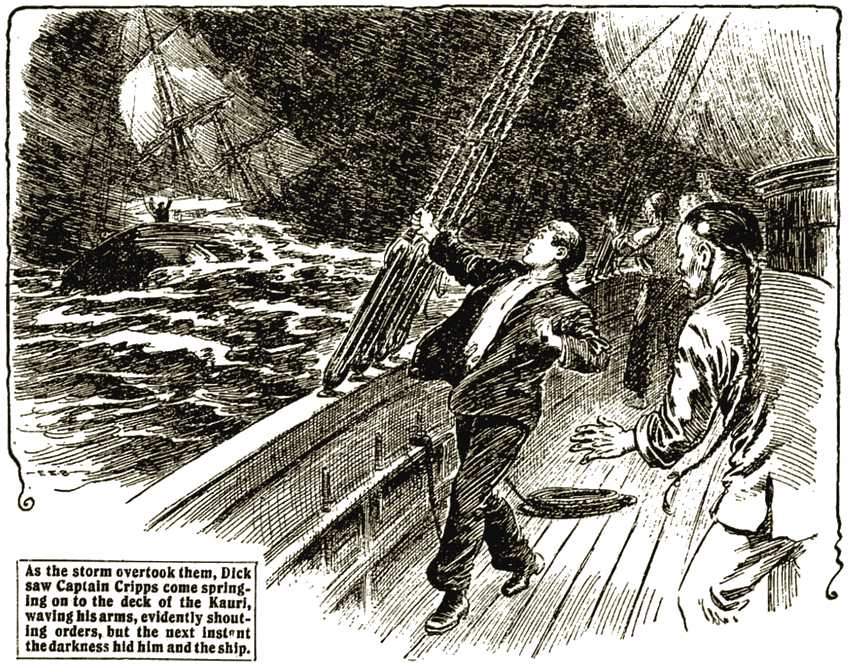

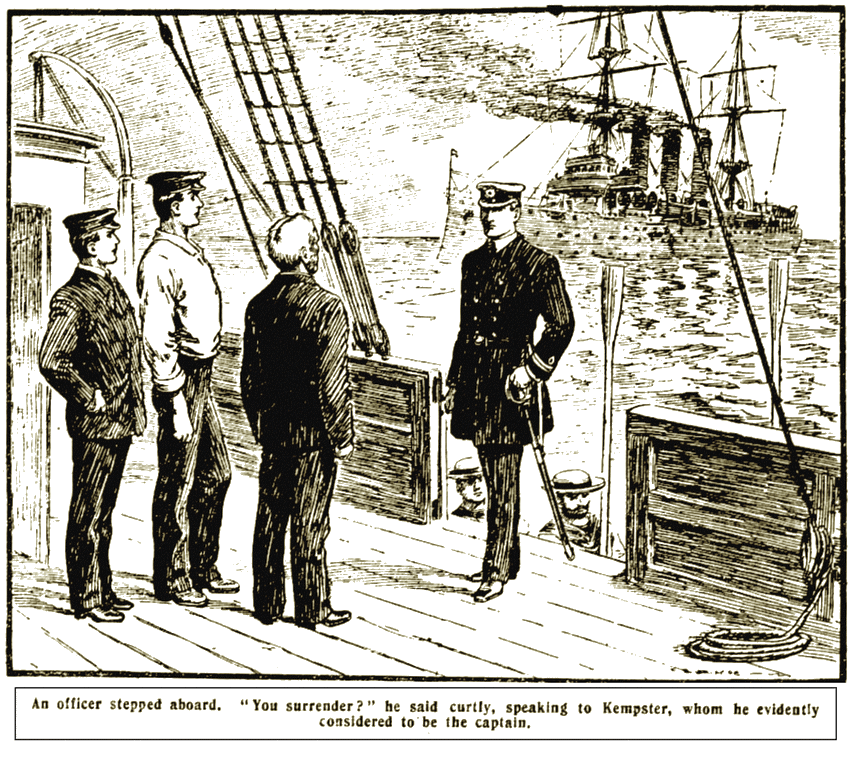

Headpiece from "The Magnet Library," 19 June 1916.

DICK, who had been leaning over the castaway, straightened himself with a sharp exclamation.

"What—" he began. Then his eyes fell on Chang's face, and the expression upon it cut his question short. For the first time since he had known the man he saw stark terror writ large on the yellow man's countenance.

Dropping everything, Chang darted for the ladder and went up it like a flash. Dick, hard at his heels, reached the deck, and for a moment stood stock still, unable to believe his eyes.

Fifteen minutes earlier, when he had left the deck, the sun had been blazing down from a cloudless sky. Now the sun was gone, swallowed by a monstrous volume of inky vapour which was sweeping up with tremendous speed The blazing heat had changed to a bitter chill.

But this was not the worst. To the southward, darkness had shut down across the ocean like a cover sliding over a hatch, and beneath it the sea was boiling under a squall of appalling fury. Dick could see the white line of foam rushing towards the schooner at the rate of an express train, while the roar of the oncoming tempest set the whole air a-tremble.

He had heard of the suddenness of these Pacific storms, but this—this was incredible, appalling.

As he stood there, helpless, not knowing what to do, the first gust caught the schooner and set her sails and spars swinging and flapping wildly.

"What can we do, Chang? What can we do?" he cried despairingly, and for the first time in his life a hideous sense of his own helplessness and ignorance overwhelmed him.

"Me not know. Me tink gettum sail down," answered Chang.

"Then call to the men. Tell them what to do!" cried Dick.

Chang shouted to the men, but they did not move. They stood where they were, clinging to cleats or stays, paralysed with fear.

Just then Dick saw Cripps come springing up on to the deck of the Kauri. He saw him rush to the side waving his arms, evidently shouting orders. Rut the roar of the storm swamped his voice, and the next instant a veil of darkness swept over him, hiding him and the ship in a single second.

Before Dick could draw one more breath it was on the schooner, and catching her full on the beam, pressed her over until her lee gunwale was buried, and it seemed that she would instantly capsize.

"You set o' swabs! Call yourselves sailormen? Are you going to let yourselves drown like rats in a tub?"

The voice came ringing through the din and thunder of the storm like the clear call of a bugle, and Dick, clinging to the starboard ratlines, turned his head and saw the boy from the Kauri spring up from the hatch and dash across the reeling deck towards the wheel.

"Stand by, men stand by!"

The Chinese crew, who had paid no attention whatever to the orders of Chang, seemed galvanised into sudden activity by the trumpet call of the stranger's voice. They sprang to obey.

"Look alive, there! Get hold of the cutter's warp! Sharp now, for your lives! Make the warp fast to the stays' halliards! Pass the end forrard; outside the rigging, you idiots! Now, make fast to the bitts! Let out some o' the line, there! That'll do! She's coming up!"

The boat, in which Dick had just returned from the derelict had been towing astern, and the first rush of the storm had swamped her.

The stranger whom Dick had rescued had seen that the one chance of saving the Rainbow was to use the swamped boat as a sea- anchor. This he achieved by fastening her to the schooner's bow instead of to the stern. The result was that the Rainbow, answering to the drag, veered round, and now lay head to the seas, pitching violently, but riding out the squall in perfect safety.

It was a masterly manoeuvre, and even Dick, utterly ignorant as he was of any form of seamanship, realised this much.

Dick had helped all he could—not that that was much. Now he stood, breathing hard, close to the wheel, and staring out in the direction of the derelict. But the rain was coming down in spouts. Nothing was visible beyond a hundred-yard radius. As for the derelict, there was not a sign of her.

"Hi, there, you—you white boy! What are you loafing there for? Get on and help get in that fore-s'l!"

Dick realised that the order was addressed to him, and for a moment resented it savagely. But only for a moment. He was aware that the new-comer had, of course, no idea to whom he owed his rescue. He knew, too, that every hand was needed, and he staggered forrard to obey.

The red-haired boy followed him. He had lashed the helm. He passed Dick, and sprang into the rigging. Clearly, he was a fine seaman. He knew exactly what to do, and how to do it; and the Chinamen, encouraged by his example, worked magnificently.

Dick, pulling here and hauling there as he was bid, was conscious the whole time of the tremendous personality of the youngster, of his enormous physical strength and driving power. So, like the Chinamen, Dick obeyed the orders that rang full and clear above the shriek of the storm.

It was quick come, quick go. They had barely finished snugging down, when the sky began to grow lighter. The rain ceased, the wind dropped, and then, like the rolling up of a drop scene in a theatre, the ragged mass of cloud swept away, leaving the sky a burning blue, with the sun flaring down upon the still heaving waters.

The cub from the Kauri went running up the weather rigging to the crosstrees. Dick saw him standing there, holding by one hand, shading his eyes with the other from the hot glare of the sun. For perhaps two minutes he stood, sweeping the whole horizon. Then he shook his head, and came swiftly down again.

"No sign of the Kauri?" said Dick, as the other reached the deck.

The red-haired youngster stared him up and down in a contemptuous way, which brought the blood to Dick's cheeks.

"No," he said shortly. "Where's your skipper?" he added.

"He was aboard the Kauri when the storm came on."

"Then the chances are he's there!" said the other, jerking his thumb downwards with an unpleasantly significant gesture. "Got a mate?" he continued.

"No. The rest of the crew are Chinamen."

"Great snakes, what an outfit! And who are you?"

"Damer, my name is—Dick Damer."

"And you're the chap who was going to let the schooner capsize without lifting a finger to save her?"

The contempt in his voice stung Dick.

"What else could I do?" he retorted. "I've only been aboard four days."

"Never been to sea before? No; I needn't ask. You don't look it. What's your job?"

"Anything and everything," answered Dick. "I was drugged in Sydney, and put aboard without knowing anything about it."

The other burst into a great laugh.

"Shanghaied—eh? Christmas, but I'll bet your skipper was pleased when he saw what they'd palmed off on him!"

The colour rose hotly in Dick's cheeks.

"It was no fault of mine. I didn't ask to come."

"You wouldn't. But, as you're here, you'd better be useful. What is this craft, and where's she bound?"

"She's the Rainbow of Sydney. That's all I know. Captain Cripps didn't tell me what her business was, or where she was going."

At the name of Cripps, a scowl crossed the other's face.

"Abner Cripps! Was that the chap?"

Dick nodded.

"The old pirate. I've heard of him. I'll lay it was some low-down game he was after. Wonder if the Chink head-man has got any notions? Which is he?"

"Chang. That tall man."

"Hi, you, Chang!" shouted the Kauri boy.

Chang stepped briskly across. From the smart way in which he obeyed the new-comer, it was clear that he regarded him with considerable respect. In fact, as Dick discovered later, the Wonderful piece of seamanship which had saved the Rainbow had given its author a very high place in the estimation of the Chinese crew. Indeed, they regarded him with a respect that was almost superstitious.

"See here, Chang." said the tall youngster briskly, "your skipper's gone. Chances are he's dead and drowned. Have you any notion where this craft's bound?"

"Chang not know nothing. Captain Clipps, he onlee man what know."

"Thought as much. Well, I suppose the best thing we can do is to 'bout ship, and get back to Sydney. And lucky for you folk I know my navigation. It I didn't, we might float around this old Pacific Ocean till Doomsday!"

He paused, and seemed to consider a moment.

"Stay! I'll have a look at the old shark's papers first. Like as not, there might be something worth getting one's teeth into. Here you, Damer, and you, Chang, come along down to the old man's cabin! May as well see I do the thing all ship-shape and proper."

He gave a quick glance round at the sea and the sky, then led the way briskly down the companion. Dick, following, could hardly repress a shudder as the other burst unceremoniously into Cripps' cabin. He half fancied that the squat, Herculean form of the skipper must rise in savage protest at the intrusion.

"Now then," said their leader, "here's his desk! Suppose the key's gone down with him? Well, we'll soon have it open!"

He looked round, and, seeing a heavy sheath-knife hanging on the wall, whipped it out of its scabbard, and set to work on the desk. There was a rending crash, and, amid a shower of white splinters, the heavy lid flew open.

Inside, besides the log-book and writing material, were several bundles of letters and papers. The red-haired boy pulled out the whole lot, flung them on the bunk, and, sitting down on the edge of it, deliberately began to examine them.

Once or twice he frowned, and once he laughed.

"Gosh, but the old man was a peach!" he muttered.

At last he came to a long blue envelope, from which he drew a letter and a chart, the latter folded across and across. As he read the letter, Dick saw his expression change. There came an eager gleam in his eyes. Then he unfolded the map, and spread it out carefully on top of the desk. Dick noticed a course pricked out across it and a circular mark in red ink.

For a minute or two the red-haired boy studied it carefully. Then suddenly he brought his fist down on the desktop with a bang that made Dick jump.

"Thought us much. Cripps was on a good thing, and no error. Here you, Damer, you can read if you can't do anything else. Take this, and squint through it. Chang, you clear out. I'll have a chin-chin with you afterwards."

Chang vanished in the curiously silent way peculiar to his race. Dick took the letter, and noted with a start that the heading was Warlindi.

"Dear Cripps," he read,—"The old man snuffed it last night. About time, too, for I've been sitting up here with him every night for a week, and a deuced tedious job I found it. However, I was there at the finish, and that's the main thing. As soon as ever I was sure that he'd really passed in his cheeks I got to work, and herewith I enclose the result. It's Kempster's chart all right, and the inland marked all hunky with the course and all pricked out. I needn't tell you what to do. You ought to be able to get the Rainbow ready inside a week. And don't you take any white men along. They might ask questions. Chinks are good enough if you pick them careful. As for the business end of this job, no need to go into that any further. You know what your share will be, and I reckon it's a darned sight more than you'd ever make if you stuck to the black-birding job till the end of your days. All I will say is, to give you a word of warning against playing me false, or keeping any of the stuff unbeknown to yours truly.

"Wesley Crane."

Dick looked up quickly.

"Why, this is written by the man who had me shanghaied!" he exclaimed.

The other eyed him sharply.

"Where do you come in? Do you know anything about this man Kempster or the chart?"

"Nothing," answered Dick. "I never heard of one or the other. I was sent out from home to my uncle, Nicholas Damer, who lived at Warlindi. When I got there I met this man Crane, who told me my uncle was dead. He said that he had liven his partner, and that my uncle had not said anything about my coming out. He told me he would give me work, and sent me back to Sydney, to stay at an inn kept by a man called Bale."

"Bale!" broke in the other. "Great ghost! The worst blackguard on the waterside! Tell you what, kid. You wore deuced lucky to escape with a whole skin. Well, go on."

"Bale drugged me," said Dick simply; "and the next thing I knew I was aboard this schooner."

The boy from the Kauri laughed loudly. Then he turned suddenly serious again.

"I don't know what this peach Crane had against you, but it's mighty clear he wanted to get shut of you as smart as he could. Well, see here; it's plain as pie that this chart was stolen from your late uncle. And if you're his nearest kin—why, seems to me you've got the best right to whatever there is in this island."

"What do you think it is?" broke in Dick.

"Pearls, most like. Anyway, it's worth having, or you may lay your last bob that this chap Crane wouldn't have shelled out to send the Rainbow after it. Now, I'm square. No one has the right to say that Barry Freeland don't play the game. But this chance is a bit too good to lose. We've got a ship, we've got a crew, we've got a navigator—yours truly. If you're game for this trip, and willing to go halves, I'm the chap to get the stuff, whatever it may be."

Dick hesitated a moment. The very vastness and vagueness of the venture daunted him. So, too, did Freeland himself. This cub from the Kauri was so big, so strong, so rough and reckless that the idea of voyaging for weeks or months in his company filled Dick with a sort of terror.

Barry Freeland seemed to read his thoughts.

"Scared, are ye?" he said, with a sneer. "Here's a chance offered ye of a fortune and, more than that, of getting square with the man that done ye down, and ye goes white and red like a baby. Gosh, how old are ye—six?"

Dick went not red, but crimson. Tears of mortification started to his eyes. He sprang to his feet.

"I'll go anywhere that you will. And—and if you talk to me like that again I'll fight you."

With the memory of Captain Cripps green in his mind. Dick fully expected a blow or a thrashing. To his immense surprise, Freeland threw his head back, and burst into a great roar of laughter.

"Flicked ye on the raw, did I? Darned if there isn't it bit of spirit in the kid, after all! All right, Damer, I'll take you at your word, and I'll draw up a bit of an agreement for you to sign. Now, cut along, and send Chang here. I've got to get him into this swim, for if he's willing, the rest of the Chinks won't make no trouble."

Dick heard nothing of the interview with Chang, but apparently it was satisfactory, for about half an hour later Freeland came on deck, and, at once taking command, gave orders for sail to be set. A course was shaped north-east, and all hands were kept busy until everything was shipshape and to Freeland's satisfaction.

By this time supper was due. Freeland called up Dick.

"Damer," he said, "you'll bunk with me, aft. Not that you'll be much use to me, but it isn't right for white men to live with Chinks. And, see here, you've got to learn—and learn mighty quick, too. I don't reckon to have to navigate this craft all the way to this here island single-handed. You'll have to stand watch and watch. See?"

"I'll do my best," said Dick humbly. And then they went down to supper.

It seemed odd to Dick to be sitting there in the cabin, with the food served on a table covered with a cloth, and with Chang bringing in the dishes. Freeland seemed to have changed everything, and changed it, too, without an effort. Dick was filled with envy at the easy way in which he gave his orders, and the promptness with which he was obeyed.

And yet there were things about Freeland which filled the other with discomfort. His table manners were not nearly so good as those of the Chinamen in the fo'c's'le. He ate with his knife, he champed his food noisily, and it was plain to Dick's fastidious eyes that he had not washed his hands before sitting down.

The new skipper of the Rainbow was utterly unlike anyone whom Dick had ever met before, and that night, after turning in, he lay awake a long time, wondering at the extraordinary turn of Fortune's wheel which had flung him into such queer company and such an amazing adventure.

"IT'S pearls all right. There's diving-dresses below."

So spoke Barry Freeland, emerging next morning from the depths of the hold.

"Ever seen a diving-dress, kid?" he added.

"I never have," answered Dick truthfully. "I've read about them, though."

"Bah! You've wasted all your life reading about things!" retorted the other. "I never struck a chap like you before."

"I—I know I'm very ignorant," said Dick humbly. "You see, I never went to school."

"No more did I. At least, not since I was twelve. I've been at sea ever since. Come and take the wheel. It's time you learnt to steer, anyway."

The schooner, with the wind a couple of points aft of the beam, was snoring pleasantly through the long blue swells. Barry, getting rid of the Chinaman, who was steering, took the wheel himself, and showed Dick how to read the compass and how to watch the sails.

"Now, take hold," he ordered.

Dick, with secret misgivings, did as he was bid, and was surprised to find how easy his task was. Barry watched him for a few minutes, then deliberately left him to his own devices, and for the next hour the schooner was entirely under Dick's control.

When his first nervousness had worn off, Dick actually enjoyed the experience. It was the first time in his life that he had ever had anything under his own control, and he took a keen pride in keeping the Rainbow exactly on her course.

"Not so bad," remarked Barry, when at last he came back to Dick. "But don't you go and think it's always going to be as easy as this. Wait till you've got to buck her into a head-wind and a head-sea. That'll teach ye something."

It was in this way that Dick's nautical education began, and Barry took precious good care that none of his pupil's time was wasted. Almost every hour of the day he was at him. He showed him how to take the sun, how to read the chronometer; he instructed him in the mysteries of dead reckoning, and taught him the names and uses of every spar and sail and sheet.

Dick, naturally intelligent, threw all his heart into the work, and learnt with such quickness that Barry was secretly pleased. At the same time he did not say so. On the other hand, he was often cuttingly sarcastic; and Dick, much as he admired him, was never quite happy in his company.

The weather remained fair, and the Rainbow, driving always north- east, ate up the miles. Each day Barry measured up her course on the chart, and Dick's excitement grew as he saw the distance lessen between her and her mysterious destination.

More than once they passed islands which hove up dream-like out of the blue sea, with the swells pounding and spouting on their coral reefs. Once Barry ran in through a wide channel into a still lagoon, and took a boat ashore for fresh water.

On the twenty-third day after the storm, when Barry took Dick below to prick off their course and write up the log, the distance between the Rainbow's position and the red circle on the chart which indicated the nameless island had dwindled to the length of a thumbnail.

"If the island's there, I reckon we'll raise her to-morrow," said Barry.

"If she's there?" repeated Dick. "B-but you don't think that she isn't?"

Barry laughed jeeringly.

"How d'ye know the whole thing isn't a fake?"

"I—I don't know, of course. But I hope not."

"Well, you'll know pretty soon if this wind holds," answered Barry, as he put the chart away.

The wind did hold, and all the rest of that day, and all night, too, the Rainbow was reeling off ten or eleven knots an hour.

At earliest dawn next morning Dick was on deck, staring out towards the north-east. He was so excited that he could hardly eat his breakfast, and brought down upon himself fresh jeers from Barry.

As soon as the meal was over he resumed his watch, climbing high into the cross-trees and sweeping the horizon with a pair of binoculars, which had belonged to Cripps.

It was about ten o'clock when, in the focus of the glasses, he caught what seemed a tiny cloud hanging between sea and sky. So like a cloud that for quite two minutes he hesitated, not really believing that it could be land.

Gradually the outline sharpened until the powerful glasses picked out the graceful feathers of lofty palms, and Dick, drawing a long breath, shouted at the top of his voice:

"Land-ho!"

Then he came sliding down to the deck with such haste that the ropes burnt his palms, and rushed up to Barry, who was standing by the binnacle.

"It's not a fake!" he cried triumphantly. "That's the island all right!"

"Let's hope there's something on it, then!" returned Barry drily.

Slowly the island lifted into sight, and in another hour they were near enough to see the huge swells breaking in white foam over the coral-reef surrounding it.

Now Barry took the wheel and Dick noticed that he changed course slightly, running up to windward of the island.

"Wonder where the opening is?" Dick heard him mutter. "Must be one somewhere. I suppose."

"It's very small—the island, I mean," said Dick.

"What's that matter? If it's pearls, they're in the lagoon, not on the island," Barry retorted.

The schooner drew on until she was parallel with the reef and about a mile to the north.

Dick gave a sudden shout:

"There's the opening, Freeland. Do you see it?"

"I've been looking at it the last two minutes," answered Barry drily; and, instead of turning in towards it, threw the schooner up into the wind, and shouted an order to heave the lead.

This was done, but the line ran out to its full length.

"No gettee bottom!" cried the leadsman.

"Likely as not it's a mile deep!" growled Barry. "Means we can't anchor."

"But why not run in?" asked Dick.

"Because we've only got one ship, you duffer; and if we pile her up there's an end of it. Think I'm going to chance running into an uncharted channel? Pretty sort of seaman I'd be!

"A nice hole I'm in!" he added, with a frown. "I can't leave the ship, for there's no one else to navigate her. And I've no one I can trust to sound the channel."

"I'll try if you like," said Dick. "Let me take Chang and Ah Lung. We'll manage, if you'll tell us what to do."

"H'm! Suppose that's the only thing," growled Barry. "Very well! Get the boat out as sharp as you can. And keep clear of the reef. If you capsize her, the sharks'll have you before you can say 'knife!'"

So the boat was launched, and Dick, full of excitement, but desperately keen to do his job to Barry's satisfaction, sat in the stern sheets and steered, while the two stolid Chinamen pulled at the oars.

As they neared the opening the roar was deafening. Although a fine day, with no more than a sailing breeze, the great Pacific swells burst on the ragged teeth of the reef with a sound like thunder.

"Steady her!" said Dick. It was the first order he had ever given, and the way in which he snapped it out surprised no one more than himself. "Ah Lung, you hold her where she is! Chang, you can heave the lead!"

The load hissed through the air and struck the water with a heavy splash. The line whizzed out.

"Folteen fathom!" announced Chung, and prepared for another cast.

Bit by bit they worked in; and risky work it was, for the current raced through the narrow opening, and the coral fangs stuck out black and jagged on either side through a smother of white foam.

"Plenty deep!" said Chang, as he took a last cast in the very centre of the channel. "Schoonel she no lun aground!"

"Carry on a bit," said Dick. "See what it's like inside."

Ah Lung took a couple more strokes, and the boat shot through into the lagoon. The change was startling. Inside, the water was calm as a lake, and of an incredible clearness. The boat seemed floating on air. Below, gay-coloured fish swarmed like birds, and in the depths corals and weeds of rainbow hues lay like a fairy garden plain to view.

Dick gasped with delight and wonder. He found it difficult to take his eyes off the beauties below and survey the island itself.

The lagoon was perhaps six or seven miles across, the island in the centre was not more than two miles in diameter. Its beach of coral-sand shone white as snow in the tropical sunshine: the centre was a mass of thick bush, with groups of tufted coconut and pandanus rising here and there from the undergrowth.

Dick scanned it carefully, but could see no sign of life. No smoke rose anywhere; the island looked as though man had never set foot upon it.

There came a sound like the distant crack of a whip.

Zip, zip, zip!

Something came skipping across the calm lagoon, cutting little white dots on its placid surface. It passed the boat with a long- drawn, whining sound.

Dick stared.

"What was that?" he asked wonderingly.

Crack! Zip! Nearer this time.

Chang and his fellow Chinaman had sprung to the oars and were pulling like mad for the channel.

"What was it?" asked Dick again.

"Someone shootee! No likee—no likee!" responded Chang, with something very like terror on his usually impassive face.

"Shooting at us! But what for?" exclaimed Dick; and as he spoke he felt as if someone had hit the boat with a hammer, and white splinters leaped from the gunwale.

The Chinamen pulled like fury, and before another bullet could reach them the boat was swinging in the rollers that poured through the opening in the reef, and Dick had his work cut out to keep her head to the foaming crests. If there was more shooting he did not hear it, and no other bullet touched them.

Ten minutes later they were alongside the schooner, which had been beating up and down outside, and Dick tumbled hastily over the counter.

"There's someone on the island!" he told Freeland breathlessly. "Someone shot at us!"

"The deuce he did! Did you see him!"

"We didn't see a sign of anybody—not a boat, or smoke, or anything. But one shot hit the cutter."

Barry frowned.

"What about the channel?" he asked.

"Plenty of room, and plenty of water. B-but are you going in? You may get shot."

Barry laughed harshly.

"Rifle-bullets can't sink the schooner," he said. "And if it comes to trouble—why, we can do our share of the shooting."

As he spoke he brought the schooner round, and ran her straight down towards the channel.

"WHERE'S your noble sportsman? Where's your chap with the gun?"

The schooner lay at anchor, every spar and rope mirrored in the placid surface of the lagoon. Barry stood with Dick by the rail, and, with his glasses to his eyes, searched the greenery, that danced and shimmered in the blaze of the afternoon sun.

"I don't know any more than you," Dick answered. "What are you going to do?"

"Go ashore and have a look round. Hi, Chang, over with that cutter!"

Chang and his fellows launched the boat, but when Barry ordered two of them into it they flatly refused to obey.

"No likee shootum," said Chang stolidly.

Barry's face flamed.

"You yellow-livered cur!" he thundered; and, making a spring like a tiger, he seized Chang by the collar of his blue blouse.

Into Dick's mind flashed the memory of Chang's former kindness, and on the spur of the moment rushed after Barry, and grasped his arm.

"No!" he cried. "No, don't hit him. You can't wonder he's scared."

Barry swung round on Dick, and there was a very ugly look in his eyes. For the moment Dick fully believed that the other would drive his fist into his face.

But Dick did not finch, and the expected blow did not come.

"Perhaps you'll come instead?" said Barry sarcastically.

"Yes, I will," answered Dick simply. "But," he added, "I can't row very well."

"You'll have to try!" returned Barry harshly. "Come on, then!"

Dick jumped down into the boat. When Barry followed, Dick saw that he was carrying a rifle. It was a .38-bore Winchester repeater.

"Pull on," said Barry shortly; and Dick, whose only rowing had been a pleasure-boat on a pond, dropped his blades in and began a jerky, unskilful progress towards the beach.

He was so busy endeavouring not to catch a crab that he had not much time to think of the danger. Yet now and then, in spite of the heat, his skin crawled at the thought that, somewhere up in that thick bush behind him, lay a man with a gun, waiting to put a bullet through his back.

But the shot never came, and presently the bow grated on the bench. Barry sprang quickly ashore and made the boat fast. Then, with his finger on the trigger, he walked quickly towards the brush.

The heat was terrific, the sand was like fire beneath their feet. The brush and palms seemed to swim in the scorching air.

"Quiet enough," muttered Barry, as he stepped into the shade of a group of palms. "If it hadn't been for that hole in the boat I'd have betted that you'd dreamed the whole thing. Gosh! I wonder where the gunman's gone? We'll have to try and track him."

He began prowling slowly along the edge of the scrub, his eyes on the ground. Dick, feeling anything but happy followed close behind.

A quarter of a mile they went, and suddenly Barry stopped short.

"Gee!" he muttered. "It was no dream, after all. Here's the tracks, right enough!"

Dick, looking down, saw footmarks plain upon a patch of sandy ground. He was about to speak, but Barry, holding up a hand, checked him, and set off on the trail like a questing hound.

The steps took them into a path—a path clearly much used, for the grass was worn flat. Yet it was so narrow that two could not walk abreast. And the path, curving through the steamy heat of the jungle-like brush, led them presently into an opening—a space of clear ground shadowed by a group of lofty palms.

Barry was leading, and he stopped so suddenly that Dick almost fell over him.

"Great ghost!" gasped Barry, and for the first time since he had met the cub from the Kauri, Dick heard real fright in his voice.

"Look at that!" muttered Barry; and as he stepped aside, Dick found himself confronted by a sight so strange and hideous that it was all he could do to choke down the scream that rose in his throat.

Flat upon the ground, under the dappled shade of the cocoa-palms, lay five skeletons. Neatly arranged, they were side by side, and about a yard apart.

They were dry bones, without one fragment of flesh, and their grinning skulls were all in line. Flat on their backs they lay, their legs stretched straight out, and their eyeless sockets staring straight upwards towards the sky.

But what was perhaps the most terrible part of this ghastly spectacle was that each skeleton head was crowned with a garland of scarlet hibiscus blooms, which glowed like blood against the paper whiteness of the bare bones.

A spasm of sickness seized Dick. He staggered and grasped at the nearest tree. For once Barry refrained from jeering at him.

"Ugh! I never saw anything so beastly!" he growled; and under his saddle-like tan his cheeks had whitened.

"Do—do natives leave their dead like this?" asked Dick hoarsely.

"Never heard of it, if they do," answered Barry. "Besides, they weren't bare feet that made those tracks we've followed. They were boots."

He paused a moment, and visibly pulled himself together.

"Come on! We've got to get to the bottom of this. The tracks are all around these bones. And, see, they lead off beyond!"

Again he took up the trail, and Dick, giddy and breathing hard, followed. The tracks led them out of the gruesome glade, and once more they found themselves in a narrow bush-trail.

Barry picked his way with care. Dick noticed that he held his rifle with his finger on the trigger. Once more the bush opened a little, and they saw another glade. It was empty, but in the centre was a pool of clear water, with a little rill running away from it, and trickling through a miniature forest of ferns towards the sea.

The spring was so strong that the surface of the little pool bubbled like a boiling kettle.

By this they paused.

"C-can I have a drink?" panted Dick.

"Go ahead. I'll watch out."

Dick dropped on his knee and put his face down to the exquisitely clear water. Never in his life had he tasted any thing so delicious as that fresh, cool draught. He drank, and drank, and sprang to his feet refreshed.

"Take the gun," said Barry, thrusting the rifle into his hands. Then he dropped down and buried his face in the sparkling pool.

It was at that moment that Dick heard the laugh, and if the sight of the skeletons had shocked him, that laugh struck terror into his heart.

It was a low, mocking chuckle, yet full of such malice that it sounded like nothing human.

He glared around, but could see nothing. The next thing he knew, Barry was on his feet, and had swiftly taken the rifle from his hands.

"You heard it?" whispered Dick.

Barry nodded. His eyes had a queer look in them.

For a minute or more they listened, and all was so still that the snapping of the tiny bubbles flung up by the spring came plainly to their ears.

"Suppose I didn't dream it?" muttered Barry. And as he spoke, Dick seized his arm and pointed.

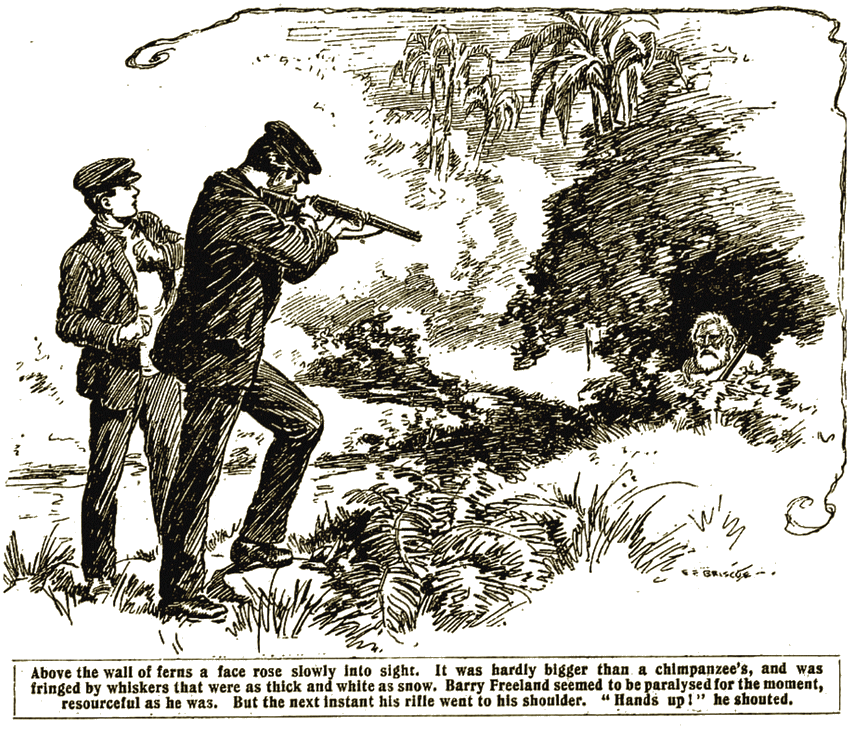

Above the wall of ferns which marked the course of the tiny brook a face had risen slowly into sight—a face that was no more human than the laugh.

It was hardly bigger than that of a chimpanzee, and the wrinkled skin was almost the colour of a well-baked coffeeberry. In startling contrast to the brown of the skin was the fringe of beard and whiskers, thick and white as snow. The top of the head was likewise covered with a mat of snowy hair.

One ear stuck out like a bat's wing, the other was missing altogether; and this gave the head a most curiously lopsided appearance.

But this mutilation Dick hardly noticed. It was the eyes that held him with a horrible fascination. Small, black, and deep-set under shaggy brows, they were filled with a sort of unholy glee that exactly matched the terrible laugh which their owner had uttered.

Barry Freeland drew a sharp, whistling breath. Ready and resourceful as he was, the hideously uncanny sight seemed for the moment to have paralysed his nerve.

It was only for a moment. Then he flung his rifle to his shoulder.

"Hands up!" he shouted.

His delay, though but momentary, had been too long. Unseen behind the close screen of fern, the other, too, had been holding a rifle.

The two shots rang out simultaneously, or so nearly so that, to Dick's ears, the two reports seemed one. But the one-eared man had evidently been a fraction of a second the quicker of the two, for it was Barry who stumbled backwards and fell heavily to the ground.

A VERY passion of rage filled Dick's soul. Without one thought to the fact that he was going to almost certain death, he made a furious dash at the brown-faced horror behind the ferns.

He saw the black muzzle of the rifle rise and cover him, and some instinct told him to duck. The whip-like crack filled the heated air with sound, and he felt the wind of the bullet past his cheek. Again his enemy pulled the trigger, but this time there was only an empty click. Either a miss-fire, or the magazine was empty.

With a snarl like that of some beast, the monkey-faced man fumbled wildly for fresh cartridges. Dick gave him no time. In the boy's heart had waked a Berserk rage, inherited from some long-forgotten ancestor. Fear was forgotten. He saw red, and his one instinct was to kill the man who had caused Barry Freeland's death.

With a tremendous bound he crashed through the hedge of ferns, and, striking the other with the whole of his weight, bore him down.

His clutching fingers gripped the lean throat; then the monkey- faced man was flat on his back, gurgling horribly, as Dick, kneeling on top of him, choked him savagely.

"Steady, kid! Don't slay him. He may be useful."

Dick looked up, and his eyes nearly started from his head. Barry, with blood running down his face, yet strong on feet and clear of voice, was standing over him.

"I—I thought you were killed!" gasped Dick; and then—what between heat and shock and the unwonted passion of anger—he suddenly collapsed. Everything around danced mistily before his eyes—a grey fog seemed to cover them; he felt himself heeling over.

It was the splash of cool water on his face that brought him to his senses. He opened his eyes and saw Barry standing over him.

Barry, with his face all streaked and mottled with bloodstains, was not a pretty sight, yet he seemed quite unconcerned, and was looking down at Dick with something very like a grin on his lips.

"You are the limit!" he observed.

Dick, horribly ashamed of his collapse, began to struggle to his feet. He was still giddy and shaking.

"Lie still, you ass!" ordered Barry.

"B-but the man with the gun—" protested Dick.

"He won't use his gun again in a hurry. He'd never have used it again if I hadn't come up when I did."

He burst into his loud laugh, which echoed oddly through the still heat of the blazing afternoon.

"You certainly are the queerest kid I ever ran against," he continued. "I'm hanged if I thought you had it in you to charge old Monkey-face the way you did! Can't think how he missed you."

"I—I ducked," answered Dick, flushing. "You see, I—I thought he'd killed you."

"He wasn't far off," Barry remarked as he took off his hat, and bent down.

"Look at that," he said, pointing to a neat little furrow about three inches long across the top of his scalp. The hair was gone, and the skin just scored. "The blow knocked me out for a moment," he explained. "It was just as well you tackled the chap like you did. If you hadn't, he'd most certainly have bagged us both."

"I—I'm glad I did right," said Dick humbly.

Barry laughed again.

"Gosh! I'd never have believed it of you if I hadn't seen it. There's hope for you, kid, after this."

Never had words of praise been sweeter to Dick. He scrambled up.

"Let me tie up your head for you," he said.

"Bless you, that's no odds! I'll just stick it in the pool a minute. And now that we've got our friend the gunman, best thing we can do is to take him back to the ship. I don't want to leave those Chinks to themselves any longer than I need."

The monkey-faced man was quite beyond doing any further mischief. Barry had seen to that. He lay flat on his back, his hands and feet lashed with sailor-like neatness.

While Barry washed the blood off his face at the pool, Dick stole across and looked at the man.

Oddly enough, the vicious, beast-like look had quite passed from his face. He lay staring up into the tree above him, paying no attention whatever to Dick. Dick, watching him, noticed that he had a great scar on the top of his head. It had healed badly, and the hair had not grown across it. It must have been a terrible wound. It seemed to have cut deep into the very bone. Dick was filled with wonder that any man could have survived such an injury.

Barry came back, and Dick pointed out the scar.

"You're right. Someone must have swiped him good and hard," Barry answered. "Tell you what, I believe he's loony."

"What—from the blow?"

"That's it. A crack on the head often sends a chap off his nut."

"Then that might explain his shooting at us," said Dick eagerly. "And—and the skeletons. Perhaps that was some of his work."

Barry whistled thoughtfully.

"Its on the cards," he muttered. "Just the sort of thing a loony chap would do. Wonder if he killed them, or whether they were his pals, and someone else came along and swatted the lot of them?"

"Murdered them, you mean?" asked Dick, in an awed voice.

Barry burst into his loud laugh.

"What else, you juggins? Did you think they turned up their toes and died in a neat little row like that?"

A month before, Dick would have been horribly shocked by Barry's levity; now he was only mildly surprised.

"Rum things happen in the islands," added Barry, as he turned to the prisoner and took the lashings off his ankles. "Now then, old bird," he said, "you're coining along with us. Comprenny? And no more gun play this journey."

The white-haired man rose to his feet quite quietly. Barry rove a length of cord to the lashings on his wrist, and made him walk ahead.

"Quiet as a sheep, ain't he? Tell you what, Dick, we'll take him past the skeletons, and see what he says."

Dick shivered. The idea of passing again those gruesome relics was anything but pleasant.

The prisoner, however, did not seem to mind. As soon as they reached the second glade, and caught sight of the skeletons, he hurried forward.

"Hallo, my hearties! How goes it?" he shouted, addressing the skeletons. "Here, you've been lying there long enough! Wake up, lads! The ship's a-waiting!"

There was something indescribably horrible in his greeting and in the whole scene. Even Barry, tough as he was, looked uncomfortable.

"Mad he is," he said to Dick—"plumb, loony."

"The ship's waiting in the lagoon. The pearls are aboard," went on the poor lunatic. "There's a fair wind, boys. We'll sail to- night for Sydney. Pink pearls, white pearls—they shine like moonlight. We're rich for the rest of our lives, if ye'll only wake up and help me sail the schooner home."

"I can't stand this," said Dick, with sudden sharpness. "Come on, Barry!"

For once Barry made no objection.

"All right. Take his arm."

"Come along, old chap," he said quite gently, speaking to his prisoner. "You're right about the schooner. I've got her waiting in the lagoon. But these chaps can't help you; they've got to stay behind."

The old man seemed unwilling to leave the poor, dead bones, but after a while he yielded, and they got him away down the bush- path, and so to the beach.

The moment he set eyes on the boat he broke into a run, and it was all the boys could do to keep up with him.

On the way out to the schooner he fell very silent again, but his queer, deep-set eyes fairly blazed with excitement. Barry had untied his hands, and he sprang aboard the schooner as lightly as a boy.

"He's a seaman, anyway," said Barry. "Wish he could tell us what's happened. There's been some black doings on the island."

"He may come round, and remember," suggested Dick. "I've read of cases like that."

"Ay, they do happen. I mind a chap in my fust ship, the Mary Power. Joe Forte, his name was. Good sailor, but sort of loony, and never spoke to anyone. We thought he was dumb. One day, in a squall, he fell off the top o' the deck-house, and we picked him up for dead. But he came round, and—bless you!—when he woke up he'd forgotten all about his voyage in the Mary Power, and thought he was back on a ship called the Hero. And talk—he talked as well as you or me! Look at the old chap!" he added. "He knows his way about."

The castaway was making straight for the companion. The boys followed him, and saw him go direct to the cabin. When they reached him, he was staring round in a puzzled fashion.

"She's not the same as she used to be. The cabin's bigger," he said, in a querulous voice.

"That's all right," said Dick soothingly. "You come along to your bunk, and get a wash and a change. Supper will be ready soon."

"That's right," whispered Barry. "You handle him. Give him a change out o' the slop-chest. He'll look more like a man when he's got some clothes on. Those rags are fit to scare a shark."

Dick nodded, and took the old chap to the spare cabin. When he brought him back to supper Barry stared.

"Gosh. I wouldn't ha' known him!" he said. "Why, he isn't so old after all."

The change was truly startling. Dick had persuaded the castaway to shave, and he had cut his hair. A good wash had left his face and hands several shades lighter, and a decent suit of clothes and a clean collar completed the transformation.

"I don't believe he's more than fifty," said Dick. "And he's as quiet as you please. Not a bit of trouble."

Chang came in with supper, and the castaway took his place at the table with the other two, and ate his food as quietly and decently as possible. His manners, indeed, were much better than Barry's, and Dick felt quite proud of his charge.

"Get him off to bed as soon as you can," whispered Barry to Dick. "You and I have got to have a chin."

The old chap made no trouble about going to bed, and Dick came back to the cabin.

Barry had Wesley Crane's letter before him, and was frowning over it.

"This is a rum go," he began. "I can't make head or tail of it. From this letter it looks to me as if Crane had sneaked the chart out of your uncle's papers, don't it?"

"Not much doubt of that," answered Dick, who was secretly flattered at being consulted.

"But it don't say who Kempster was, nor how your uncle got hold of the chart," continued Barry. "Anyways, Crane must ha' thought he was on to a good thing, and my notion was that this was an unknown island with a lagoon full of shell, and that Kempster had discovered it and sold or given the secret to your uncle."

"That seems reasonable," said Dick.

"Reasonable! Then how the mischief does this chap come to be marooned here? Who are the dead men? What's happened?"

Dick considered a moment.

"Perhaps my uncle sent an expedition, unknown to Crane, and they fell out over the pearls. There might have been a mutiny, and the mutineers killed their officers and cleared out with the schooner and the pearls."

Barry nodded.

"Yes, that would explain it. Or another schooner may have happened in on top of the first and tackled her. There are always a lot o' dirty pirates cruising round these seas."

"Then wouldn't the first schooner be lying here somewhere?" suggested Dick.

"No; they'd ha' scuttled or sneaked her."

"What do you think of doing?"

"May as well see if there are any pearls or shell left in the lagoon. I shall go down first thing in the morning."

Before turning in Dick took a peep at the cutaway. He found him sleeping like a baby, but just to be on the safe side he locked the cabin door on the outside and took the key.

It was a needless precaution. The man was still sound asleep when, at dawn, Dick unlocked the door.

The ship was astir early. Barry was eager to test the lagoon, and immediately after breakfast a diving-dress was got up, together with the pump and other apparatus.

Chang looked over the side, measuring with his eyes the depth of the water.

"No wantee dless," he said suddenly to Barry. "Me tink divee klite easy."

"Why the mischief didn't you say so before?" growled Barry. "All right. You go down one time, and see what the shell is like."

Chang nodded, and disappeared down the fo'c's'le hatch. Inside two minutes he was back, stripped to the buff, his yellow skin gleaming in the sunlight.

In one hand he carried an open basket, under the other arm a plummet-shaped stone with a loop of cord through a hole at the smaller end.

"Why, he's a regular professional diver!" said Barry, aside to Dick. "Look at the reef scars on his chest and shoulders! And I never knew it."

Without hesitation the man stepped down on the diver's ladder which had been put over the side. He reached the water level, stepped off, and shot down into the transparent depths below.

Breathlessly Dick watched him sink into the gorgeous growth of weeds and coral, scattering the shoals of brilliant-hued fish in his swift descent.

He reached the bottom, where the black sea-cucumbers lay like monstrous slugs on the snow-white sand. The long, blue sea-grass swayed under his feet, as, stooping, he swiftly plucked some unseen objects from the floor of the lagoon.

"What about sharks?" muttered Dick, as he watched.

"They don't come inside much," answered Barry. "It's precious seldom they venture inside a lagoon."

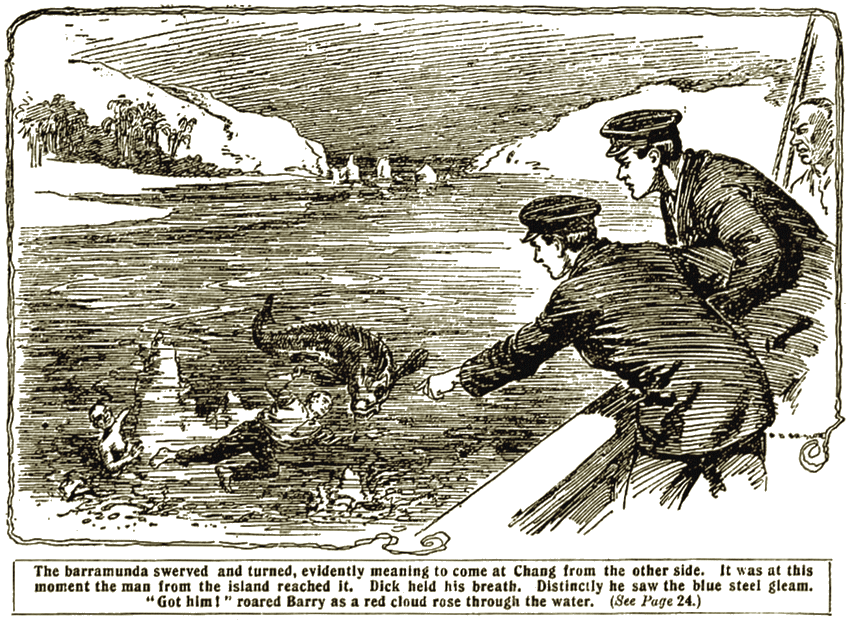

"Then what's that?" demanded Dick sharply, as he pointed to a long dark shadow that had suddenly appeared no more than the schooner's length away from the spot where Chang was moving.

The change that came over Barry's face was startling.

"A barramunda!" he gasped. "It's all up with the poor beggar!"

He spun round.

"Here, you chaps, barramunda!" he yelled. "The brute's after Chang. Any of you game to tackle it?"