RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

THERE is no man more sensitive to ridicule than the sailor. He detests the merest suspicion of being laughed at, and, while among themselves in the fo'c's'le sailors yarn endlessly, it is most difficult for the landsman to get a seaman to talk freely. Even then, one doubtful look or word of disbelief and he shuts up, close as the proverbial oyster.

The consequence is that we on land never hear of many of the strange things that happen at sea. For instance, you will hardly ever get a sailor to mention the sea-serpent. While those who have gone most deeply into the subject have little doubt about the existence of still unclassified sea monsters, the sailor, knowing with what ridicule the Press greets any mention of these creatures, no longer reports their appearance. And the same or even greater reticence is observed with regard to the seeing of phantom ships and other ghosts of the sea.

Many of these supposedly supernatural appearances are doubtless explainable from natural causes. To take one instance, the mystery of the well-known phantom ship of Cape Horn has recently been elucidated. Over and over again vessels on their way from Europe to Western America via Cape Horn have been startled by the sight of a large ship with decks awash drifting in an almost impossible position beneath the giant cliffs of the Straits of Lemaire. At night or in storm this barque with her towering white sails has the strangest appearance. The Crown of Italy attempting to go to the aid of the supposed derelict, ran upon a reef and was wrecked, and a similar fate has befallen several other vessels. Last year, at the request of the United States, the Argentine Government sent a steamer to make researches. It was found that the supposed phantom was nothing but a rock—a rock which, by some strange freak of Nature, was white instead of black like those surrounding it, and bore the most startling likeness to a ship with sails set and deck just level with the waves. Another strangely-shaped rock off St. Helena, whitened with sea birds, bears so exact a resemblance to a full-rigged ship that the oldest and most experienced seamen have been deceived.

Mirage, again, may account for some of the spectres which have puzzled and alarmed mariners. Mirage is a phenomenon not confined to sandy deserts, for it is seen over snowfields and glaciers and at sea. In 1854 H.M.S. Archer cruising in the Baltic, saw the whole of the British Fleet of nineteen ships inverted in the air apparently only a few miles away. At the time the fleet was actually hull down, the nearest ship being quite thirty miles from the Archer. A gentleman living at Bedhampton recently described how the Nab Lightship, which is really twelve miles from his house, was brought by mirage so near that the men on board could be clearly seen with the naked eye.

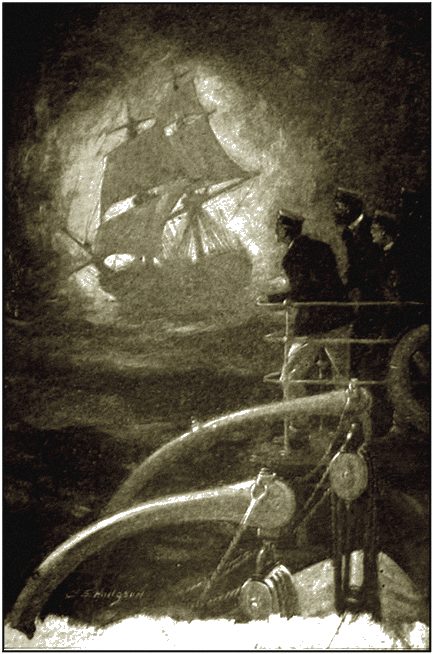

But apart from such natural phenomena, there are things seen at sea by no means so easy of explanation. We have no less credible a witness to the appearance of a true phantom ship than the present heir to the throne. The incident is recounted in "The Cruise of the Bacchante." On July 11th, 1881, at four o'clock in the morning, a spectral ship crossed the bows of the vessel in which the present Prince of Wales and his late lamented brother were cruising round the world.

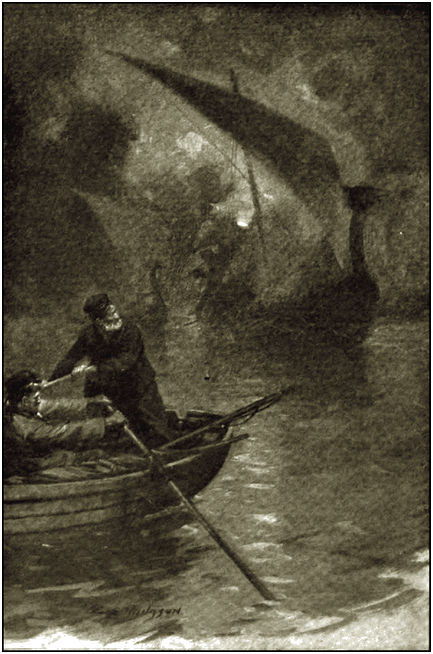

A spectral ship crossed the bows of the vessel

The apparition is described in these words: "The Flying Dutchman crossed our bows. A strange red light, as of a phantom ship all aglow, in the midst of which light the masts, spars, and sails of a brig two hundred yards distant stood up in strong relief. Thirteen persons altogether saw her, but whether it was Van Diemen or the Flying Dutchman, or who else, must remain unknown. The Tourmaline and Cleopatra, which were sailing on our starboard bow, flashed to ask whether we had seen the strange red light." It is a curious fact that six hours later the able seaman who was the first to sight this terrifying apparition fell from the foretop-mast crosstrees and was smashed to pieces.

The so called Flying Dutchman is the best known of all ghostly wanderers of the ocean, and his story the most familiar. The usually accepted version is that Cornelius Vanderdecken, a Dutch sea-captain, was on his way home from Batavia when, in trying to round the Cape of Good Hope, he met with baffling head winds, against which he struggled vainly for nine long, weary weeks. At the end of that time, finding that his ship was in precisely the same position as at the beginning, Vanderdecken burst into a fierce fit of impious passion, and, dropping on his knees upon the deck, cursed the Deity and swore by Heaven and Hell that he would round the Cape if it took him till the Day of Judgment. Taken at his word, he was doomed there and then to beat to and fro for all time, and sailors' superstition connects the appearance of his phantom ship with certain and swift misfortune.

Vanderdecken is not the only ocean wanderer in the latitude of Cape Agulhas. There is another Flying Dutchman in the shape of Bernard Fokke. Fokke, who lived in the latter half of the seventeenth century, was very different from the ordinary type of Hollander. He was a reckless fear-nothing, who boasted that his vessel could beat any other afloat. To make good his boast he cased her masts in iron and crowded more sail upon her than any other ship of the time dared carry. It is on record that he made the passage from Rotterdam to the East Indies in ninety days, a feat at that period savouring of the miraculous. The story goes that, in his anxiety to beat even his own record, Fokke sold his soul to the Evil One, and at his life's end he and his ship both disappeared. Transported to the scene of his old exploits, and with no other crew than his boatswain, cook, and pilot, he is condemned to strive endlessly against heavy gales that ever sweep him back.

Whether the phantom ship be that of Vanderdecken or of Fokke, the fact remains that nine-tenths of all the reported appearances of phantom ships are between the fortieth and fiftieth latitudes. Nor has the age of steam killed the tradition, for a year rarely passes without some vessel sighting one of these ghostly wanderers of the ocean. All sailors believe that, while spectre ships usually hail any vessels which they meet, it is the height of bad luck to reply in any way.

Phantoms of the sea have frequently been seen off various parts of our British coasts. In old days Cornwall was notorious for the wreckers, who worked their wicked will along the iron-bound cliffs. Priest Cove is believed to be still haunted by one of these gentry, who during his lifetime preyed on the spoils of unfortunate vessels lured ashore by a false light hung round the neck of a hobbled horse. The wrecker is seen on stormy nights, but now no longer on shore. He clings to a fragment of timber among the breakers, and is eventually dashed upon the rocks, and disappears in the roaring foam.

The fishermen of the rugged coast of Kerry have another legend connected with the fate of wreckers. One winter morning, early in the eighteenth century, a large ship was found, mastless and deserted, wedged among the rocks of that deadly coast. The wreckers eagerly pushed off, and to their joy found that the galleon was laden with ingots of silver and other rich produce of Spanish America. They filled their boats to the water's edge, and were eagerly pulling back when a monstrous tidal wave came rushing up out of the west. The horrified watchers on shore saw their brothers and husbands instantly swallowed up, and when the wave had broken not a sign remained of boats or men or ship. Upon each anniversary of the day the grim tragedy is said to be re-enacted.

The Solway has more than one phantom craft. Centuries ago two Danish sea-rovers, who had spent a lifetime in deeds of crime and cruelty, put into the Solway with their long ships heavy laden. A sudden furious storm broke, and the overweighted ships sank at their moorings with all aboard. Upon clear nights these two vessels, with their high curved prows and rows of shields along the gunwale, are sometimes seen gliding up the estuary, but no money would tempt the local fishermen to go out to meet them. The story is that about a century and a half ago two young men, pot-valiant, did row out to investigate.

These two vessels, with their high curved prows and rows of shields

along the gunwale, are sometimes seen gliding up the estuary.

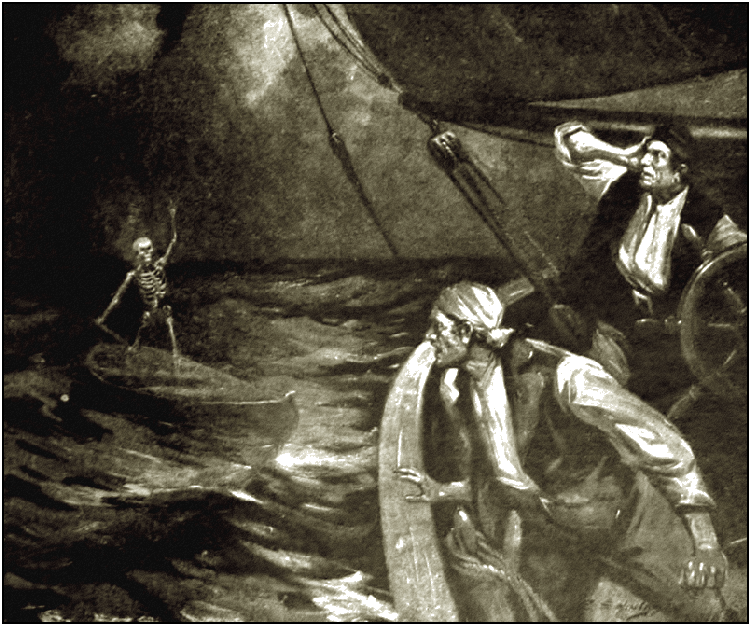

They were watched to approach the ghostly visitants, when suddenly the galleys sank, and the boat and its occupants, drawn down in the swirl, were never seen again. The so-called "spectral shallop" of the Solway is the apparition of a boat which was maliciously wrecked by a rival while ferrying a bridal party across the bay. It is manned by the fleshless ghost of the wrecker, but the only ships which it approaches are those which are doomed to wreck or disaster.

It is manned by the fleshless ghost of the wrecker.

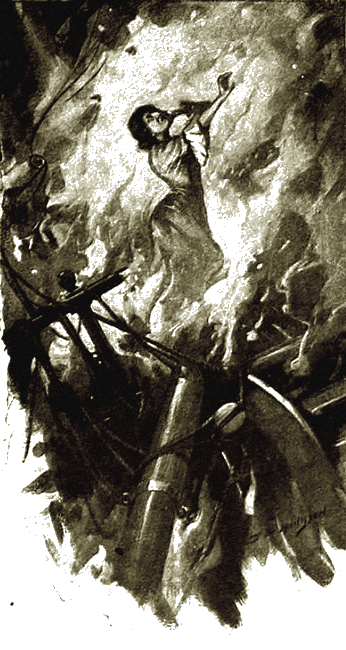

The rocky coasts of New England are haunted by several ghost ships. Of these the spectre of the Palatine is the best known, and her appearance flying down Long Island Sound is generally recognised by fishermen and coasters as a forewarning of disastrous storm. Her story is a terrible one. The Palatine was a Dutch trader which, lured by false lights exhibited by wreckers, went ashore on Block Island in the year 1752. Having stripped her, the wreckers, in order to conceal all traces of their crime, fired her. As the tide lifted her and carried her, wrapped in flames, out to sea shrieks of agony burst forth, and a woman, presumably a passenger who had hidden herself in fear of the wreckers, appeared on deck amid the crackling blaze. Next instant the deck collapsed and she vanished.

A woman appeared on deck amid the crackling blaze.

The New Haven ghost ship is, like the Palatine, an omen of disaster. In January, 1647, a vessel built at New Haven sailed on her maiden voyage. In the following June there came one afternoon a furious thunderstorm, and after it was over, and about an hour before dark, the well-known craft was sighted sailing into the river mouth—but straight into the eye of the wind. People crowded upon the shore to watch her, but while still a mile or more away she slowly vanished from sight. It was agreed that the apparition signified that the ship herself had been lost, and, in fact, she never was heard of again. Longfellow has written a poem embodying the story, of which one verse may be quoted:—

And the masts with all their rigging

Fell slowly one by one;

And the hull dilated and vanished

As a sea-mist in the sun.

The storm-ridden Gulf of St. Lawrence is still haunted by the flagship of a fleet sent by Queen Anne against the French. The fleet reached Gaspe Bay, when a fearful gale rose suddenly, and one after another the ships were driven on the rocks and broken to pieces or sunk. It was under the tall cliffs of ill-named Cape d'Espoir that the flagship came to her end, and upon each anniversary of the wreck the sight is repeated. Her deck is seen to be covered with soldiers, and from her wide, old-fashioned ports lights stream brightly. Up in the bows stands a scarlet-coated officer, who points with one hand to the land, while the other arm is round the waist of a handsome girl. Suddenly the lights go out, the ship lurches violently, her stern heaves upwards, and screams ring out as she plunges bow-foremost into the gloomy depths.

There are other sea phantoms besides apparitions of vessels, and not all are portents of misfortune. Some, indeed, are kindly in intention. Such was the drowned man who appeared in the middle of the night to Captain Rogers, of H.M.S. Society, and warned him to go on deck and have the lead cast. He did so, found only seven fathoms, tacked, and when morning came saw himself close under the Capes of Virginia instead of, as he had imagined, being more than a hundred miles out at sea. Another kindly ghost is a lady whose child was drowned at sea and who roams the beach at Lyme Regis searching for the body. Those who see her and afterwards follow where she has walked always find coins.

A well known novelist has written a most gruesome story of a ghost which invaded a cabin in a modern liner, and lay in its accustomed berth, dripping with salt water and festooned with seaweed. It is a very old belief among sailors that the ghost of a drowned man returns in this fashion. In Moore's "Life of Byron" it is related that a certain Captain Kidd told the poet how the ghost of his brother (then in India) visited him at sea and lay down in his bunk, leaving the blankets wet with sea-water. He noted the time and found that it corresponded exactly with the hour at which his brother was accidentally drowned.

A similar incident occurred much more recently in the United States Navy. Twenty years ago the old U.S. corvette Monongahela had a paymaster, a red bearded man with one eye, who was known throughout the navy as one of the best story-tellers in the service. He was a most popular man, but, alas! his love of whisky eventually brought him to his end. He died on board; and before his death he said to the other officers, "Dear boys, you've been good to me, and I love you for it. I can't bear to think of leaving the ship, and if I can I shall come back, and you'll find me in my old cabin, No. 2 on the port side." Although nobody allowed that he believed the "Pay" would come back, yet No. 2 remained vacant for three cruises. Then Assistant-Paymaster S—— joined the ship, and having, as he said, no superstitions installed himself comfortably in No. 2. All went well and they were homeward bound when, one night in April, the whole ship was terrified by unearthly screams. The officers rushed out, and there was S—— in a heap on the floor of the flat outside the cabin. When asked what was the matter, he gasped out, "A dead thing—a corpse in my berth—one eye and a red beard. Horrible!" When he had recovered himself a little he explained that he had awakened, feeling very cold. As he moved he came into contact with something clammy, slimy, and cold as ice. By the dim light which leaked through the port he saw that he had a bedfellow, a corpse with one eye staring, and a red beard tangled with seaweed. The officers crowded into the door of No. 2. There was no corpse, but on the wet and tumbled blankets lay a few fragments of barnacled seaweed!

Another ghost story concerns the United States Coast Survey schooner Eagre. The Eagre was once a private yacht, and went by the name of the Mohawk. One fine evening she was lying off Staten Island with her starboard bow anchor out. Her mainsail and staysail had both been left standing, and for some reason no one knows what—the sailing-master had hauled aft the main-sheet and secured it before going below. He had hardly dropped down the hatch when a squall swept up, and in an instant the Mohawk was on her beam ends. Nearly everyone was drowned, including the captain. The vessel was raised again and sold to the United States Government, but her crews ever afterwards declared that she was haunted. Every night the sailing-master would come on deck with a rush, spring to the main sheet, and frantically attempt to cast it loose in order to save his vessel.

It is a common belief among sailors that a ship which has been sunk and raised again is haunted by the ghosts of those who were drowned in her. Some fifteen years ago a large emigrant steamer was sunk in the Mediterranean, and over five hundred lives were lost. Thousands were spent in raising the vessel. She was brought home and refitted, but has never since been used. It is impossible to keep a crew. The men declare that every night the great hull rings with the screams and groans of the multitudes who sank, like rats in a trap, to the bottom of sixty feet of stormy sea.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.