RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

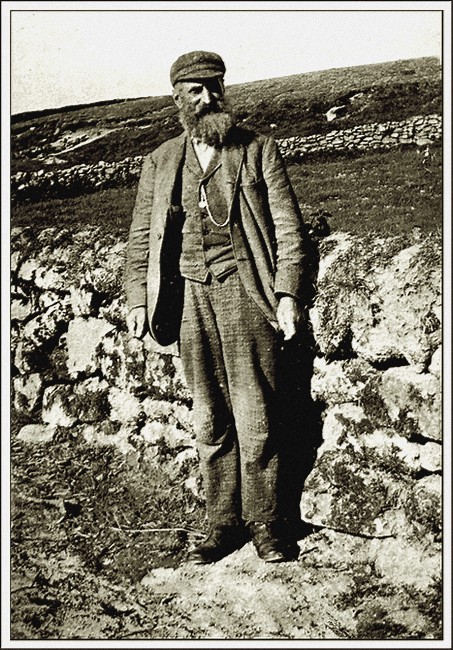

Frontispiece

The Author

MY very old friend, the author of these reminiscences, has flattered me by inviting me to write an introductory note.

We first met as journalists. He has followed that strangely alluring profession with distinguished success and always with the eagerness of youth. My own path, since our early days, has been in another direction; but those who have once lived in Fleet Street can never be indifferent to its charm, can never lose sympathy with the men, the companions of adolescent years, who have remained faithful to their original purpose.

Fleet Street is not an easy road; it is littered with failures or broken men and broken enterprises. I have seen brilliant spirits extinguished and fortunes fruitlessly squandered in Fleet Street. It is only now beginning to be realised that the true journalist is born and not made. His qualities are curiously rare. In an age when everybody can write, surprisingly few succeed in Fleet Street, though there are people who say that journalism is only a "knack." I do not think so. I suspect that there is something of disappointed envy, as there certainly is a world of misunderstanding, in such an ascription. The great journalist at least must possess qualities that come near to genius.

But there is a certain technique of journalism that can be learnt. What to say and how much to say. When to say it and to what audience to address it. All these things can be learnt. It is useless to send a Quarterly Review article to a daily newspaper, or an article on cricket to any paper in the height of the football season; or, let me say, a passionate exposition of Liberal aims to a trenchantly Conservative journal. I give but a few instances. Yet, these mistakes are made every day, and by clever writers. Too often they sicken of repeated failure and join the ranks of that still numerous band who console themselves with the belief that editors accept only the work of their personal friends.

Mr. Bridges is the one free-lance journalist known to me who, having achieved the security of an editor's chair, has voluntarily returned to free-lancing. It was a risky thing to do. The outside contributor to the Press is dependent week by week on the amount of literary work he can produce and place each week. Unless he is untiringly industrious and exceptionally fertile in ideas the lean weeks are likely to eat up the fat ones. But he has his advantages. He enjoys a large measure of freedom; he can, if he wishes, live a country life. To Mr. Bridges this has been an inestimable boon. His several books and innumerable articles on open-air subjects are fruits of his emancipation from the bondage of daily work in Fleet Street itself.

I commend this book especially to the beginner in journalism. He will gain much from it that he could not acquire from his unaided experience alone. Above all, he will learn that to a natural aptitude for his craft must be added the method, the diligence, and the high and indomitable spirit that have secured for Mr. Bridges his place among the journalists of to-day.

—Cecil Harmsworth.

Schooldays—Westward Ho!

FORTY years ago it was still usual for parents to choose their son's profession, and that often before the boy was out of the nursery. In my own case my father made up his mind that I should follow in his footsteps and become a parson. In those days we called it "going into the Church." So in 1879, at the tender age of ten, I was sent off to Marlborough, where, for more than a year, I was the youngest boy in the school, and consequently got most of the kicks and precious few of the halfpence. Somehow I managed to win a foundation scholarship, a performance which naturally confirmed my father in his opinion that I was specially destined for a clerical career. And as for me, I was too young to have any opinions of my own on the matter.

There was a deal of bullying in those days at Marlborough, and, I fancy, at most other big schools as well. Pretty beastly bullying, too. I have seen things happen worse than any described in Tom Brown. The unpleasantest time for us youngsters was on winter nights between tea and prep., when a gang, armed with blood-knots (unpleasant scourges made of knotted boot-laces), roamed Court (as the quadrangle is called) in search of victims. Many and many a time have I stood, shivering in the porch of "A" House, waiting till the very last minute, before bolting like a rabbit for Upper School, where, being in the Lower Fourth, I had to do my preparation. If I live to be a hundred I shall never forget the sick suspense of those times.

The food left much to be desired. Bread and butter for breakfast, bread and butter for tea. Not too much butter, either. Soup and meat or meat and pudding for dinner. No porridge, eggs, sausages, not even jam. Poor fare for growing boys, and consequently a lot of illness among those whose parents could not afford to supply them with extras. In common justice, I should say that matters improved in this respect even before I left, but at first they were very, very bad.

G. C. Bell was head master, a perfect figure of a "head," with his fine features, flowing beard, and beautiful hands. But he was never popular. Chiefly, I think, because he was a Radical, and boys are the most conservative creatures on earth. I remember a great political row. It was in the year when Walter Long was first returned for the Division. Boys had been strictly ordered to remain within bounds on Election Day, and the whole of the town beyond St. Peter's Church was put entirely out of bounds.

Early in the afternoon word came that the Conservative candidate was approaching along the Bath Road, whereupon nearly the whole school sallied out to meet him. The horses were taken out of his carriage, and several hundred boys pulled him, cheering, past College Gates and right down town to the Aylesbury Arms, where Mr. Long was called upon for a speech. There was a sharp scrimmage between his supporters and the rival faction, the air being thick with bloaters raided from a stall. I think we all expected to be "swished," and I know that the head master was extremely angry. But no doubt there was mediation, for in the end all that happened was the stoppage of one half-holiday, a penalty which was as bad for the masters as the boys.

Games were compulsory, and, though I enjoyed cricket, I well remember how I loathed being driven up to play Rugger. I was never any use, and was generally condemned to take part in "Remnants," where some thirty a side played upon a piece of rough ground which sloped steeply to a ditch. Inevitably the game gravitated to the edge of this ditch, and in the end the whole scrum would go rolling over into it, with consequences most unpleasant to the unfortunates who were at the bottom.

Marlborough has the great advantage of being set in the centre of some of the most lovely of all down country, and my great joy was to escape to the forest. Savernake Forest was, and I hope still is, a place of pure delight. It was full of birds and beasts, from red deer to squirrels and from great hawks down to golden-crested wrens. One Sunday a friend named Stayner and myself found a red stag which had recently died, and spent a gory hour in hacking off its head with our pocket knives. We then started back, with the intention of leaving the head with Colman, the taxidermist, to be set up. Just as we got out of the forest, who should come riding along but the young Marquis of Aylesbury (the one who afterwards married Dolly Tester) and his sister! He gave a view halloo, and started after us, and we bolted for some chalk pits, where we dropped the head, then ran for our skins for a clump of thorn bushes. The marquis did his best, and the thong of his whip licked around our ears time and time again. But in the end we got clear away. We were, however, nearly half an hour late for Sunday afternoon Scripture lesson, and caught it accordingly. Then there was Clinch Common, where, at the proper season, wild raspberries were plentiful, and from the top of which is one of the finest views in Wiltshire.

We had a capital Natural History Society, which, although jeered at by a section as "The Bug and Beetle," yet found plenty of recruits. It was managed by the Rev. T. A. Preston, mathematical master and one of the keenest and best naturalists I ever had the luck to meet. "Prunk," as we called him, had a red-hot temper, and I remember his knocking a boy right into one of the glass cases in the old museum where we were taken. It should, however, be added that he had caught the youth in question first at cribbing, then in lying. In summer we had occasional field days, delightful occasions when we drove miles into new country and visited Silbury Hill, Avebury, Stonehenge, and many other places of interest. I don't suppose there is any other part of England which can match that side of Wiltshire for relics of our Neolithic ancestors. We had constant encounters with keepers and farmers, and once I was shot at by an irate gamekeeper and quite sharply peppered. On another occasion a pal and myself were forced to swim the Kennet in order to get away from a water bailiff. The present generation of boys seem to have abandoned these rather violent forms of amusement, but they now have far more forms of diversion than in my day. What with bicycles, wireless, photography and the like, they are never without something to do.

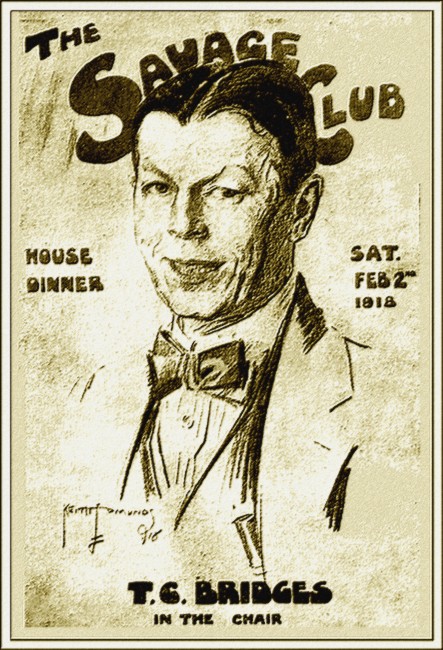

I have no doubt but that many Marlburians of my time have since become distinguished folk. The late Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson was there in my time, but he was older than I, and I never knew him. I do, however, remember E. F. Benson, who was in "B" House and keen on racquets, and Eustace Miles, who was a contemporary in "C" House. The two Irvings, Harry and Lawrence, were also at Marlborough with me. They did not shine at games, but were by no means unpopular. Lawrence I never saw again after leaving, but Harry I had the pleasure of meeting frequently in later days. The very last time that I saw him was at a Savage Club Saturday Night a few months before he died. I sat next him, and remember how sadly ill he was looking.

Of the masters, the one whom I always remember with pleasure was W. J. ("Slogger") Ford. He was master of the Middle Fourth when I was promoted into it. Of huge stature, though not so tall as his brother, "The Stork," he was one of the most powerful men I ever saw. Even a playful cuff from him would floor the biggest chap in his form. And what a cricketer! It was his joy to take the bowling at a net and set boys out at enormous distances to field. If a boy caught one of his monstrous smites he was usually rewarded with a pot of jam. In those happy days you could buy a pot of real strawberry jam for sevenpence.

Very good cricket teams used to come down to Marlborough. We always played the Gentlemen of Lancashire, and I remember Hornby hitting up a huge score. On one occasion, when I was a very small lad, E. M. Grace, W. G.'s brother, honoured me by sending me off to the pavilion to fetch him a glass of lemonade. I spoke of "The Stork," W. J. Ford's brother. He was six foot six, and I once saw him hit a ball full-pitch, not only out of the ground, but on to the thatched roof of a cottage on the other side of the road. It was by far the biggest hit I ever saw in my life, and it would be interesting to know its length. W. J. himself went to New Zealand after leaving Marlborough, but later came back England and took private pupils, at the same time doing a good deal of cricket journalism. I had the great pleasure of meeting him again in London, and he came to dine with me at the Cocoa Tree. I remember how he laughed at me because I still called him "sir." For the life of me, I could not help it. He died soon afterwards, still a comparatively young man.

I suppose I was about sixteen when I began to have my doubts about turning parson. I am afraid it was a sad disappointment for my poor father, when he was eventually forced to agree with me. Of course, there was only one alternative—to emigrate. At that date, though only forty years ago, any boy who failed in his Army or Civil Service exams., or who, for any reason, refrained from the profession for which he had been originally intended, went either to America or one of the Colonies. Never was there a more curious delusion than that a lad who had shown himself unfit for the Church, the Bar, Medicine, or the Services, should have been considered capable of making a living at what is perhaps the most complicated and exigent of all callings, namely, that of farming.

In 1886, the year in which I left Marlborough, the first Florida boom was at its height, and the papers were full of advertisements of the enormous profits to be made by growing oranges. The very name of Florida had a magic, and when I heard that the State possessed the finest fishing and shooting of any part of the South, I was mad to go. So in the end it was arranged, and in September 1886 I formed one of a convoy of three going out under charge of a clergyman named Noyle, who was himself intending to settle in the States. We sailed on the Egypt of the National Line, a comfortable old tub that possessed three tall masts as well as engines, and set a full suit of sails whenever the wind was favourable.

My chief recollection of New York is the profusion of fruit and the cheapness of the ice cream. We spent three days there, and went south by boat to Charlestown. We met a full gale off Hatteras, and the top-heavy steamer took an ugly list. Charlestown we found in parlous condition. Three weeks earlier the town had been practically wrecked by the worst earthquake ever known in South Carolina. The streets were still cumbered with piles of masonry, and the spires and chimneys tottered drunkenly. But the people were quite cheerful. We changed steamers and left again about two in the morning.

Now we were at last reaching the sub-tropics. Sky and sea were bluer than I had ever imagined; shoals of flying fish lifted out of the smooth swells. I saw a green turtle floating on the surface. Thirty-six hours later we were steaming up the immensely broad estuary of the St. John's River to Jacksonville, then, as now, the commercial capital of the State. A river steamer took us up from Jacksonville. The St. John's is probably the widest river in the world for its comparatively short length. It opens into lakes eight and ten miles in breadth. We passed the house of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the famous author of Uncle Tom's Cabin, a book which did more to inflame the passions of the North against the South in the great Civil War than anything else that has ever been written. Having lived so long among the kindly Southerners, it may be that I take a prejudiced view, but I say frankly that I think Mrs. Stowe was a dangerous extremist whose writings did a terrible deed of harm.

Slavery, of course, had become an anachronism in the nineteenth century, yet the servitude of the negro race was nothing like so black as Mrs. Stowe painted it. In point of fact, slaves were extremely well treated, and very rarely bought or sold. Among Southern gentlefolk it was considered a disgraceful thing to divide a family. Mrs. Stowe took her colour from the only State where conditions were bad, and made it seem that these conditions were usual all over the South. At the time when I went out the Civil War was still a matter of almost recent history. It was only twenty-two years past. I have known dozens of negroes who were formerly slaves, and who, almost without exception, deplored their changed condition. As one dear old black mammy of sixty said to me, "If Ah still belonged to mah old mahster Ah wouldn't be working now at mah age."

At four the next morning we were dumped on a board wharf at the river-side to wait for a train which was to leave at eight. On the verandah of the little hotel I found a fishing-rod, and, baiting with a piece of pork raided from the meat safe, promptly hooked a gigantic cat-fish which pulled like a horse until in the end it got the line round a snag and broke me. We breakfasted on fried pork, buckwheat cakes and syrup, and hot coffee served with "long sweetening" (that is, molasses), then got into the train and went trailing away slowly through the "piney" woods. Never was anything more bitterly disappointing than the view from the windows. Stunted pines, saw palmetto, cypress swamps, and here and there a savannah with scrub cattle grazing. The whole country was flat as a pancake, and steaming under a fierce blaze of sunshine.

By degrees the ground rose a little and the swamps were replaced by lakes. At last we ran into "hammock," that is hard wood forest, with splendid live oaks and glossy-leaved magnolias. Then to the left we saw the broad expanse of Lake Harris, and presently stopped at Lane Park, a new little town on the lake-side. Winterpark was my destination, but Noyle had friends on Lake Harris and had arranged for me to stay a day or two before going on. His friend lived a couple of miles up the lake-shore, but his boat was waiting. If the country so far had disappointed us, Lake Harris and its surroundings came as a delicious surprise. The hammock, tangled with climbing masses of grape vines, was the tropical forest of my dreams, and the shores sloped down to beaches of exquisite yellow sand. Here and there graceful cabbage palmettoes towered high above the bays and gums. We had hardly pulled a mile before the evening breeze sprang up, and inside five minutes the lake, which, when we started, had been smooth as glass, was a mass of short, steep, and very dangerous waves. It was all we could do to beach our light, flat-bottomed craft on the nearest stretch of sand, and the rest of the journey we did afoot. Our host's house was still a-building, and he was living in his stable. He gave us supper, and announced that he had fixed up a 'possum hunt for our benefit. I had not had a wink of sleep the previous night while coming up the river, and precious little the night before, but at eighteen one does not worry about that sort of thing, and I was eager to start. At nightfall, just as swarms of golden fireflies began to dance over the hammock, there arrived four young Americans and three negroes, together with a pack of half a dozen large, ugly, yellow hounds, and a few minutes later we all started away together into the woods.

Very soon the dogs got upon the track of an opossum, and drove it up a persimmon-tree, around which they bayed furiously. The persimmon was a tree which here in England would be prized as a splendid specimen, but the niggers tackled it with their axes, and, in a very few minutes, it came crashing to the ground, flinging the wretched opossum from its leafy summit.

The dogs had the creature in a moment, and killed it. They would have eaten it, but the negroes drove them off, and dragged their prey from them.

The opossum weighed about eight pounds, and bore a strong resemblance to a gigantic rat. I was told that it made as good a dish as a young sucking pig, and this is indeed perfectly true, for later I caught many in traps and ate them.

The hunt went on. Towards midnight I became so sleepy that I could hardly keep my eyes open, but there was no going back, for, alone, I should have been hopelessly lost before I had gone a quarter of a mile. It was three o'clock before we stopped hunting, and, lighting a smudge fire to keep off the mosquitoes, camped until daylight.

I stayed three days at Lake Harris, then my friend drove me to the terminus of the Tavares and Orlando railway. On this line, which was in a very bad way, there was but one train each way in the day, and these alternately passenger and freight trains. As ill luck had it, I struck a freight train, and had to travel in a box car.

It was a gruesome journey. The heat was frightful, the dust and smoke suffocating. The line was little better than two streaks of rust, and only once did the speed exceed twelve miles an hour. This was when, in the middle of a big swamp, the engine-driver suddenly saw half a dozen cattle on the metals directly ahead. It was too late to pull up, so, opening his throttle to the widest, he charged.

It was a horrid business. The wretched beasts, caught by the cow-catcher, were hurled off the embankment into the deep black slime on either side. The shock threw me flat on the floor, and for a moment I fully believed that the train would follow its victims; but, by a miracle, we held the metals, and carried on.

It was dark before we reached Orlando, which is the capital of Orange County, and to-day a very beautiful town. Even at that time, nearly forty years ago, it was a place of three thousand inhabitants, a large proportion of whom were people from the northern States.

What between the dust, the smoke, and the heat, I was by this time nearly as black as the negro train-conductor, and I actually hesitated to leave the train. But I was desperately hungry, and, in any case, had to change trains.

Close by the depôt I found a rough little restaurant kept by an Italian. I went up to the bare counter, and asked for a sandwich and a cup of coffee. A large roll, split in half, with a thick slice of ham in the centre, was pushed across and a mug of coffee poured out.

I never knew food taste better, for it was twelve hours since breakfast, but when I asked how much, the little Italian waved his hand. "You no pay," he said; and, after a moment's puzzlement, it came to me with rather an ugly shock that he took me for a tramp. Not that I blame him, for I was hardly recognisable as a white man.

It was with difficulty that I made him accept ten cents, then the good fellow allowed me to have a wash in his kitchen, and I set off to catch my train.

At Winterpark there was no one to meet me, and I was told that the house for which I was bound was two miles out in the wood. At last I found a nigger who was going my way and who acted as guide.

In those days the pupil farmer was more common than he is in 1926, and it was to one of these gentlemen that, unknown either to myself or to my people, I had been consigned.

The pupil farmer was a person who had a farm of some sort or another. It might be wheat in Canada, tobacco in Virginia, or oranges in Florida, but, whatever crop was grown on the soil, it did not yield the same profit as that derived from the human grist employed by its owner.

The modus operandi of the pupil farmer was to advertise in English papers for farm pupils. In every case he promised home comforts, good society, and good sport, and undertook to turn them out finished farmers. His charge was usually about a hundred pounds a year.

There are honest pupil farmers, especially in the remoter parts of our own Empire, but the American brand could not have been so described by any stretch of the imagination, and the gentleman into whose hands I had the misfortune to fall was one of the worst of his breed. He was a big, dark, and rather good-looking man, soft spoken and outwardly pleasant mannered. In actual truth, he was a soulless scoundrel, and the worst bully whom I have ever encountered.

Of the year which I spent under him I prefer to say as little as possible. All the hardest, dirtiest work fell to my share, and, as I learned later, the neighbours were under the impression that I was a hired hand, and was getting the usual dollar a day for my services.

Hard work hurts no healthy youngster, so long as he is decently treated and fed, but the food was the worst part of the business so far as I was concerned. All through the great heat of the following summer I had to live upon salt pork, sweet potatoes, and "biscuit," that is, baking-powder bread.

I got no fresh fruit or vegetables, and, into the bargain, the water (from an old well) was intensely nasty, and no doubt hideously unwholesome. The result was that I developed blood-poisoning and became covered with horrible sores.

There was no doctor in the place, and, in any case, my boss would have taken very good care that I did not see one.

In the end I became desperate and cleared out. I had one friend, son of an old Southern officer, General Samuel French, who lived at the other end of the big lake, and the youngster arranged with his father that I should live with them and work for my board and lodging.

General French was one of the best-known leaders in the Confederate Army, and had been a friend of the famous Jeff Davis. He had been in the regular U.S. Army before the war, and was a graduate of West Point. But he had settled in the South, married a Southern woman, and when the war broke out had definitely thrown in his lot with the Southerners. It was he who held the fort near Chattanooga, when that famous old song was written, "Hold the fort, for I am coming." He was a little man with a quick temper, but the kindest heart imaginable. He lived to a very great age, and died only about ten years ago.

A Swamp Story—Batching It

THE work on General French's property was every bit as hard as what I had been doing. We were up at half-past four every morning, and did two hours' chores before breakfast, and, barring the midday rest of two hours, we were busy until nightfall.

Yet the change was like one from hell to heaven. The old general was kindness itself, and his cook—a burly negro named Cicero Mack—knew the last thing about Southern dainties. Delicacies such as fried chicken, beaten biscuit, and guava jelly were on the table every day. There was any quantity of fresh milk and butter, and we had an excellent garden, from which came lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers, water-melons, okra, and many other vegetables.

While living with the general, his son and I made use of a short holiday to go off on a shooting and fishing trip, during which we very nearly came to a bad end.

Our idea was to take a boat, put it on the head waters of the Wekiva River, drop down the river through the swamps to the point where it met the St. John's, then sail up the St. John's to Sanford, and so home. Two young American friends of the general's son came with us, and we four loaded the boat on to a waggon, and hauled it to the source of the Wekiva.

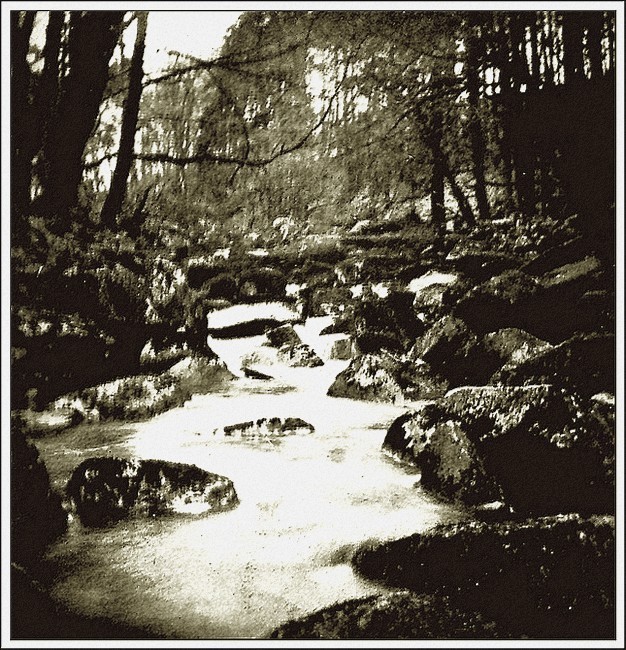

Like many other Florida rivers, the Wekiva leaps full fledged from one mighty spring, with a stream large enough to float a good-sized boat. We were warned that no one had been down the creek for some years, but it was not until we had gone some distance that we began to realise the difficulties in our way. The first thing that happened was the finding of a huge dead log right across the stream. When we started to cut it away, thousands of large red ants poured out of its rotten recesses and covered the boat, our provisions, and ourselves. They bit like fire. Some hours later we reached a saw-grass swamp, where shallow channels meandered between great grey walls of stiff, sharp-edged grass. It was not long before we went hard aground, and, when two of us jumped out to lighten the boat, we found that the bottom was quicksand, and had to scramble back with all possible speed. It took us an hour or more to get clear.

Our idea had been to spend the night at a place called Clay Springs, which was only about fifteen miles from our starting-point. But we had not reckoned on the delays, and night found us pulling along a deep, narrow, sluggish waterway, over-arched by giant cypress-trees. The roots of these trees formed the most extraordinary buttresses, edging the river like wooden rocks. From their branches above hung enormous trails of grey Spanish moss, so thick that the creek resembled a tunnel.

The creek itself was so sluggish that in places it was completely blocked by weed. This weed, known as water-lettuce, floats upon the surface, and, when it meets any obstruction, gathers in thick rafts, so thick that oars are useless and the boat has to be poled. What is worse, the under-water layers rot away, filling the air with the sickly reek of decay. Just as the light failed completely we struck one of these bars, and, when half-way through it, found that a monstrous tree-trunk lay all across the river a few inches below the surface.

It was out of the question to cut it. The only way to get past was to drag the boat over it. Two of us got out, and stood barefooted on the slimy log and set to hauling the boat over the obstruction. I shall not easily forget the sensations of those few minutes. In the first place, I was aware that if I lost my balance, and fell into the water, the heavy crust of vegetation would effectually prevent my ever reaching the surface again; but the worst part of it was the knowledge that the water-lettuce was the favourite haunt of the water-moccasin, the much-dreaded Florida swamp viper. This creature is short, thick, sluggish, and extremely venomous.

Luckily, all went well, and we got the boat safely over the log and into clearer water beyond. Now, since it was almost pitch dark, it was necessary to camp, but our trouble was that we could find no dry land to camp upon. The water was higher than usual for the time of the year, and in between the great cypresses was nothing but a sea of glutinous black slime. The only chance was to land upon one of the great buttress roots of which I have already spoken, and this we did, and, with much difficulty, lighted a small fire and set our kettle to boil. But these buttresses are hollow, and very rapidly the fire burned through the shell and fell hissing into the water beneath.

There was nothing for it but to make up our minds to a night in the boat, and let me tell you that there is precious little room for four men to sleep in the bottom of a small cat-boat. To add to our miseries, clouds of mosquitoes and sand-flies settled down upon us. The mosquitoes were bad enough, but the sand-fly, which is so small that it can go through an ordinary mosquito-net, bites like a red-hot needle. We lit a smudge fire in a frying-pan, and the smoke did something to keep off the insect pests.

Tired out, I fell asleep, to be roused by a deep roaring sound, and, jumping up in a fright, saw that the huge cypress-tree, at the base of which we kindled our fire, was all alight. It was a weird and even terrible sight, for the flames, rushing up the hollow trunk, spouted crimson torrents from every knot-hole. Tied up as we were, close under the burning tree, our position was one of great danger, and we had to shift in a hurry to a spot a hundred yards farther up-stream. There we sat and watched the blaze mounting to the summit of the doomed giant. The flames threw a lurid glare over a wide area of the swamp, and the reddened smoke rose in a great plume high into the windless air.

All sorts of swamp birds, roused by the unnatural glare, flitted, shadow-like, around the burning tree, and the roar was like that of a blast furnace. Presently great branches began to come crashing down, and towards three in the morning the charred ruins of the forest monarch toppled over, and went thundering and hissing into the depths of the swamp.

At dawn we breakfasted on a tin of bully beef and some dry biscuits, and pushed on. We passed the deserted ruins of a shingle-cutter's camp, and twice that morning got lost in blind channels. About two in the afternoon we discovered the entrance to the Clay Spring Run and turned up it. This was a clear and comparatively swift stream, teeming with fish. After two hours' hard pulling we reached its head, where there bursts out at the foot of the hill a spring large enough to float a steam launch. The water is a clear green—so clear that you can see a sixpence at the bottom in thirty feet. It is charged with sulphur, and its temperature of seventy degrees never varies, summer or winter.

As soon as we had tied up the boat we all stripped and plunged into the great spring. The rush of this giant source is so great that it picks you up, rolls you over and over, and flings you out into the tranquil little lake beyond. The water has extraordinary curative properties. Within a few moments it had washed away all the stinging discomfort of my numerous bites, and my skin felt soft as silk. Much refreshed, we made our way up the hill to the settlement, and were most kindly received in the house of friends, who gave us an excellent supper and spread mattresses for us on a wire-screened verandah.

Next morning we were off again early, and soon found ourselves back in the depths of the swamp. The next two days were one long struggle through rafts of water-weeds, and, as before, it was impossible to find landing- or cooking-places. What made this the more annoying was the fact that we were catching any quantity of fish. By merely trailing a spinning bait behind the boat we were able to take any number of magnificent black bass. We also caught a quantity of crimson-throated bream, one of the best of fresh-water pan fish.

On the second evening after leaving Clay Springs we did at last strike solid ground, and, landing, lit a roaring fire, made a huge pot of coffee, and set to grilling fish. It was thirty-six hours since we had last had a decent meal, and I, personally, finished a three-pound bass as my share of the supper.

We slung hammocks and slept in comparative comfort. Early next morning we found ourselves at the mouth of the Wekiva where it opens into the St. John's. The day breeze had not yet begun to blow, and the river was like glass, so we started to row southwards in the direction of Lake Monroe, on which lies the town of Sanford. We had gone but a little way when we heard a hoot in the distance. One of the big river steamers was coming up behind us at full speed. As ill luck would have it, we were in one of the narrowest parts of the river, and we saw at once that we should be in considerable danger from the wash. But we knew that there was no chance of the steamer slackening speed, so all we could do was to turn the boat bow on to the wave and take our chances. It is true that we could all swim, but that would not have helped us, for the river is bordered by tall saw-grass, through which no human being could hope to force a way. The bow wave came curling up a yard high, and, before we knew it, the boat was half full of water. We bailed like fury, and somehow kept afloat. But, comparing notes afterwards, we all agreed that not one of us had expected to come out of it alive.

Just as we reached the head of Lake Monroe the breeze began to blow. We got up our big sail, and the rest of our journey was finished in comfort. Reaching the wharf at Sanford, the first person we met was the father of Godfrey Moyers, one of our crew. He glanced at us and passed on. The fact was that our faces were so disfigured by mosquito bites that we were all entirely unrecognisable.

A letter from home contained the surprising announcement that my father had purchased an orange-grove for me. It was the fact that I had been making my own living for some months past which had induced him to make me this present.

For any man in England to purchase a property from complete strangers, at a distance of four thousand miles, is bound to be a somewhat risky proceeding. But my father, an old-fashioned English clergyman, was himself too honest and upright to realise the likelihood of being swindled in such a transaction, and, in result, he paid nearly a thousand pounds for a place which was possibly worth three hundred.

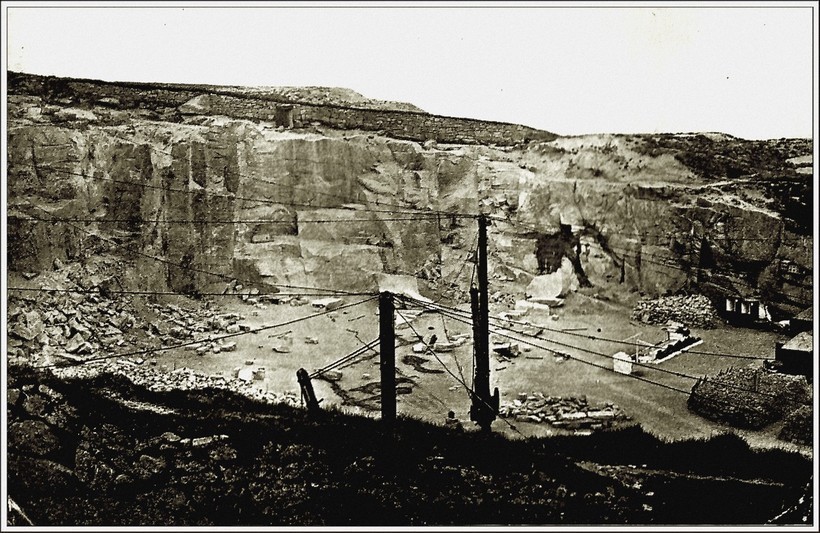

The property was, in all, eight acres. There was a little four-roomed house, a small stable, and about one hundred and fifty old orange-trees. But these trees were seedlings, not "budded" trees, and the fruit was inferior in quality. Also, they had been badly neglected. It was years since they had been pruned or properly fertilised, and the trunks were covered with moss and the ground with weeds.

The land lay between two lakes, and had the advantage of a constant draught of air, which made it cool and healthy, but, on the other hand, it was nearly three miles from the nearest railway station, and in those days there were no roads in Florida, but only narrow tracks, deep in soft, yellow sand.

In spite, however, of the obvious disadvantages, I was delighted to have a place of my own, so set to work to move in as soon as possible. The trouble was that I had not a stick of furniture, or any tools or agricultural implements. Nor had I a pony, which is the first necessity of life in a new country. My entire capital was about twenty-five dollars—say five pounds in English money. Hunting about, I discovered a man who was selling out and leaving, and from him I purchased a small iron cook-stove, some pots and kettles, crockery, a cot with a wire mattress, a table, and two chairs. I gave him eighteen a dollars for the lot, hired a waggon, and hauled them to my new home. The stock of flour, coffee, salt pork, and necessary groceries ran away with most of my remaining seven dollars, but I had a gun and a fishing-rod so hoped to make out.

I shall never forget those first months of "batching" it. The house stood on a patch of white sand which was covered with scrub palmetto, and my first job was to clear this and make a garden. The heat was terrific, and those palmettoes had roots like wire. The heavy stems, each as thick as my leg, ran along the surface, with their tentacle-like roots penetrating deep into the ground. Each had to be grubbed separately, and, even when they were grubbed and piled, they would not burn. I had to cut pine logs in order to start each fire.

It was the rainy season, and each day we had a crackling, roaring thunderstorm. For days together the storm would gather in the morning and break about twelve. Then it would shift, and for perhaps a week come at three in the afternoon. Sometimes the clouds did not bank up until nightfall, and that was worst of all, for on such days the sky was clear and the heat almost intolerable. I had no neighbours except one poor, crazy white man on the far side of the lake and half a dozen negro shacks a mile in the other direction. I had no books except a paper-covered Shakespeare, and, of course, no newspapers. For days together I never exchanged a word with a human being, for I was nearly five miles from the English settlement at Conway, and equally far from the county town of Orlando.

Of course, I did all my own cooking. At first it was very rough. I shall never forget the first time I tried to make yeast bread. The yeast, I think, was bad; at any rate, the dough refused to rise; so, leaving it in a bowl in the kitchen, I went out to work and forgot all about it. When I came back in the evening a second fermentation had taken place. The dough had risen clean out of its pan, had crawled over the table, and hung in long festoons to the floor. Red ants had found it, and were crawling in thousands up and down the dough icicles. But experience teaches, and I soon learned to make excellent baking-powder bread, potato cakes, and even gingerbread. Later I made guava jelly from my own guavas, and capital marmalade from the sour oranges which grow wild round the lakes. Americans I may mention, neither made nor ate orange marmalade,—at least, not in those days.

My two chief troubles were the fact that I had no fresh water, or money to put down a well, and that, for a similar reason, I could not afford the wire blinds which were fitted to all windows in the tropics for the purpose of keeping out flies. Flies were an absolute torment, and the only way to keep the house free from them was to darken it. I managed to buy some old green window-blinds second hand, which aided me to do this.

Probably because of the bad water, I suffered again from blood-poisoning, and this time a druggist in Winterpark gave me Fowler's solution of arsenic, telling me to take three drops three times a day. No doubt I took too much, for within a week I was desperately ill—so ill that I could neither cook, nor eat, nor sleep. No one came near me, and for some days I believe that I was in a very dangerous state, but somehow I pulled through, and presently found that the arsenic had done the trick, and that my blood-poisoning was completely cured.

October came, and cooler weather. I had now been in the country two years, and had made some friends. Occasionally I had an invitation to supper at some English or American house, and thought little of tramping five miles through the woods in either direction. One of my friends was a Yankee named Ward, and there came to stay with him another Vermonter named Denny. Denny was as keen as I on fishing, but knew little about it. And the odd thing was that, although he was a man of over thirty, he had never been in a boat in his life. One day I took him out in a borrowed boat on a big sheet of water called Lake Virginia. It was a sultry afternoon, fish did not bite well, but after a time Denny got hold of something heavy, and hauled up a great, ugly black-fish weighing about four pounds.

Now, a black-fish has a large mouth full of small but very sharp teeth, and I warned Denny to be careful in taking the hook out. Too excited to hear what I said, he thrust his hand into the gaping mouth, and the jaws instantly closed on his fingers. Uttering a yell of pain, he stumbled backwards, and fell with a crash into the bottom of the boat. In doing so he knocked one oar overboard and—worse than that—one of the metal rowlocks with it. The rowlock sank, of course, and, while I was reaching for the oar, a strong squall of wind caught the boat, and inside a minute a furious thunderstorm was raging.

With only one oar it was impossible to get the boat back to the near shore. I was forced to let her drive. It is astonishing what a sea gets up on one of these shallow lakes, and, of course, the farther we ran towards the far side of the lake the higher grew the waves. Denny had to bail for dear life, but, even so, the boat was absolutely waterlogged by the time we struck the far bank. There we had to beach the boat and tramp four miles in drenching rain.

About this time I had a legacy of a hundred pounds from a relative in England, and the first thing I did was to put down a well. There was no digging about it; I simply purchased a "point"—which is a perforated steel pipe with a sharp end. I drove this into the ground, screwed other lengths of pipe into it, and at a depth of about fifteen feet struck good water.

After that there was nothing to do but affix a small hand-pump on to the upper section of pipe, and, at a cost of about four pounds, I had an unfailing supply of deliciously cool water. Then I fitted blinds to my windows, painted the whole house, bought some fertiliser for the grove, and set to work to find a good pony.

I found a pony, but I have to confess that it was not a good one. Its looks were the best part of it, but its temper was abominable. It was what they call in America a "balky" horse, and it always chose to balk at the most inconvenient season. Also it was given to stumbling, and, soon after I had it, this unpleasant habit nearly brought me to a sudden end. I had ridden into Winterpark one evening to get my post, and was returning home up the broad avenue leading past the hotel. Down the centre of this avenue ran the tram-line from the hotel to the railway station. I was going at a sharp hand-gallop when Master Brandy, as I called him, shied, stumbled, and came down. He pitched me clean over his head, and I fell on mine on the near metal of the tram-line. For a moment I hardly realised that I was hurt, and I picked myself up, intending to go after the pony, but Brandy had already made himself scarce, and, feeling rather giddy, I made my way back to the drug store at the corner. In American towns, where there is no saloon, the drug store, with its soda-water counter, is the favourite resort, and as I entered there were three or four men in the place. They turned as I came in, and one and all gasped or exclaimed in horror. Then I caught sight of myself in a looking-glass, and was no longer surprised at their dismay. I was absolutely covered with blood—face, clothes—it was even in my boots. The fact was that I had cut an artery over the skull, and—so the druggist told me—should have bled to death if help had not been near. He, however, stitched up the cut, a friend drove me home, and in less than a week I had forgotten all about my tumble.

White Folk, Black Folk, and Crackers

I AM told that nowadays Florida has more than a million visitors each winter. In my time the entire population of the State was only about three hundred thousand, but the tourist traffic was already going strong. The first of the magnificent winter hotels was the Ponce de Leon, built by Flagler, the oil magnate, at St. Augustine, on the Atlantic coast. Plant, owner and builder of most of the Florida railways, ran the line through to the port of Tampa, on the Gulf Coast, and decided to build there an hotel which should be, not only the finest in Florida, but the most luxurious in the world. He began this in or about the year 1891, and the result was a most imposing building in the Moorish style, with copper domes and minarets, and accommodation for about three hundred visitors. Almost every bedroom had its own bathroom—a very unusual thing in those days; there was a wonderful circular ballroom, a vast drawing-room furnished with costly old French furniture and a white velvet pile carpet studded with golden lions. I mention the lions because of these I shall speak hereafter. There were stately pleasure grounds, with a small private zoo, hard tennis courts, a landing-place on the bay, with a fleet of all sorts of pleasure craft, to say nothing of a private railway siding. I never saw a place upon which money had been lavished so recklessly.

To open this hotel Plant organised a big tennis tournament, and was good enough to ask a number of us young Englishmen to play. We had talent among us, two men especially, Grinstead and Garrett, being very nearly first class. Among the Americans who came down was dear old Dr. Dwight, the father of American lawn tennis, and the two Wrights. It was great fun. We Englishmen travelled down from Orlando in Plant's private car, and at the hotel we found all sorts of delightful Americans and Canadians. The tennis was not taken too seriously. Every night we danced till midnight, then played pool or poker until far into the small hours. One of the finest of New York cocktail mixers presided over the bar, and such sherry cobblers, gin fizzes, and whiskey sours I have never tasted elsewhere.

Among the English contingent was a man known as "Bones," who was given to mixing his drinks rather recklessly. One night—or, rather, morning, for it was past two—Bones was missing, and a search-party was organised. For a long time we hunted in vain, then, as I passed the double doors of the great state drawing-room, I heard something move inside. Looking in, I found the room flooded with the soft light of the moon, then nearly at its full. The light showed up a solitary figure on hands and knees in the centre of the vast expanse of white carpet. It was Bones, and, as I watched him, he was creeping very slowly and cautiously forward. He stopped, raised his right hand, in which he was grasping something which looked horridly like a dagger but was actually only a paper-knife, and brought it down with a vicious thud. "Bones! Bones!" I called, hurrying forward. "What on earth are you doing?" He looked up. "Get out, you fool! Can't you see I'm killing lions?"

All sorts of people came to Florida for the winter. On one occasion President Cleveland and his wife stayed at the big Seminole Hotel at Winterpark, and a reception was organised. In a long row we filed before the President and Mrs. Cleveland and solemnly shook hands, then passed on. Though Winterpark was then merely a village, there were three or four hundred people present, and Mr. Cleveland was shaking hands for an hour on end. I am told that one of his successors, President Roosevelt, once shook hands with eight thousand guests in one afternoon. No wonder that a President, after his four years of office, usually ends with his right hand a whole size larger than his left. Cleveland was a typical American President, a big, solid, middle-class man. The politicians who control the destinies of the great republic invariably choose a person of this type. When a man like Theodore Roosevelt arises, every effort is made to keep him in the background, for the last thing wanted is a really strong President. In Roosevelt's case, he was cleverly shelved by being made Vice-President, and it was only the fact that poor McKinley was murdered which set the great Theodore in the Presidential seat.

Another interesting visitor to Florida was Bishop Whipple of Minnesota. Physically, he was one of the finest men whom I have ever seen, over six feet in height, straight as a wand, narrow-waisted, broad-shouldered. He had the high cheek-bones, piercing eyes, and straight black hair of the American Indian. Indeed, he bore such a remarkable resemblance to a Red Indian that he might have been one of the old chiefs reincarnated as a white man. Perhaps it was this which helped to make him such a power among the Indians. They called him "Straight Tongue," and truly he could talk straightly. He was a very great preacher indeed. We had Indians in Florida, the remnants of the once powerful Seminole tribe. They lived in the depths of the Everglades, that vast swamp which occupies the southern extremity of the peninsula. It is an interesting fact that these Indians had negro slaves, and kept them long after the Civil War of the sixties ended in the freeing of all slaves.

Florida has the most mixed population of any State in the Union, with the possible exception of California. There are the old Southerners, a small and dwindling minority, but the most charming people imaginable, and the very soul of hospitality. There are Yankees, keen, hard-working, long-headed, who have done everything to develop the resources of the State and, incidentally, to enrich themselves. They have built the railways and the hotels; they have drained the swamps and planted oranges, vines, and peaches. At present they control the great and growing trade in early vegetables for the Northern markets. There are "crackers," as they are called. These are the descendants of the "poor whites," that is, the white people who, before the Civil War, had no slaves. It is difficult to decide upon their origin, but they are certainly of mixed descent. It is said that they come, at least in part, from a colony of Minorcans planted in Florida by Governor Oglethorpe in the eighteenth century. Thirty years ago they were a very degenerate race, living in rough log or frame cabins in the depths of the piney woods. Each family had a small patch of corn (maize) and sweet potatoes. For the rest, they lived by shooting, fishing, or trapping. Some owned great herds of scrub cattle. One, a neighbour of mine, told me that he owned over eight hundred cattle, yet this man had never tasted fresh butter in his life, and I don't believe he had ever drunk fresh milk. The cattle were a poor lot, and were generally killed for their hides. Their beef was almost uneatable. The cracker women used to chew snuff—a horrible practice which left them toothless at thirty. Very few could read or write, and one used to hear extraordinary stories of the savage feuds which prevailed among them.

There were two clans—the Mazells and the Barbers—who had an hereditary quarrel. The men used to ambush one another with guns or rifles until at last there were only three Mazells and one Barber left. The Mazells, so the story runs, laid for the surviving Barber, caught him, tied a keg of nails to his legs, and dropped him into a deep lake. And that was the end of the Barbers. Even in my day there was still a certain amount of shooting. One day, when fishing in a boat on a lake, I was unpleasantly surprised by the crack of a pistol from among the thick growth on the shore and the nasty ping of a bullet close above my head. I lost no time in dropping into the bottom of the boat, but there was no second shot, and presently I thought it safe to pull rapidly away. I was not aware at the time of anyone who disliked me sufficiently to put a bullet into me, and, thinking it over, put it down as simply a silly practical joke. But listen to the sequel. A few days later I rode into Winterpark to get the mail, and my way took me along a track leading through the thick hammock bordering the same lake where I had been fishing. There was a thick malarial mist, and I went through at a sharp canter. As I reached the higher ground beyond I heard a gun-shot behind me, but paid no particular attention. I thought it was merely a nigger after a 'possum. I tied up my pony outside Ergood's store, which was also the post office, went in, and stood chatting while the mail was sorted.

Suddenly a young American came riding up at full gallop. "Say, there's a man been shot over in the hammock by Lake Virginia," he shouted. We all poured out. The marshal (policeman) was summoned, and, with him in charge, we went to investigate. We found a man lying in the road with his head shattered by a charge of buckshot. He was a cracker from a settlement on Lake Monroe, four miles away, and the place where he lay was only a few yards from the spot where I had been fired at. There was strong suspicion that he had been shot down by a man with whom he had quarrelled over a girl, but it was impossible to obtain proof, and the murderer, if murderer he was, went free. But the latter had been seen hanging about in this particular hammock on two days previously, and I have wondered if he was the same gentleman who took the pot shot at me.

The old-fashioned cracker was not a pleasant neighbour, for he had no sense of meum and tuum. He was worse than a 'possum in the chicken yard, and would raid whole sackfuls of oranges from a grove during the owner's brief absence from home. But, even before I left the State in 1894, a great change was coming about. The Education Authorities were getting hold of the rising generation, and by this time the old, bad cracker is practically extinct.

Negroes—"coloured people" is the polite term—far outnumbered the white population. I confess to something of a liking for the nigger, particularly the old-fashioned sort that could neither read nor write. Lazy fellows, yet good workers when put to it; always cheery, and showing their wonderful white teeth in the broadest of grins. So skilful, too, with axe and hoe! When I first moved to my little property the grove was full of old, dead pine-trees—stark, ugly, rotting relics. How to get rid of them was the question, for it looked as if it was sheerly impossible to fell them without smashing the growing orange-trees to smithereens. A negro named Ki Johnson, whom I consulted, smiled at my qualms. "Ah'll cut dem down, sah," he promised. "Ah won't hurt none ob dem orange-trees. You gib me a quarter apiece, and Ah don't get no pay ef I breaks a orange-tree." I agreed gladly, and inside two days the dead trees were down and not a single branch broken from a orange-tree. A man like Ki would drive a peg into the ground by felling a tree so as to drop exactly upon it. There was a negro settlement at the end of the lake, a mile from my place, so I could always get help when I wanted and could afford it. Wages were a dollar and a quarter (five shillings) a day, but by far the better plan was to bargain on a piece-work basis. If I wanted rails split, firewood cut, or a ditch dug, I could always get a nigger to take on the job for a lump sum, and I have known a man cut a whole strand of wood (ordinarily speaking, a good half-day's work) before breakfast. An old nigger mammy used to do my washing. One day the wash did not return on the usual day, so I rode down to see what was wrong. I found aunty, who was nearly as broad as she was long, standing under a shelter of palmetto leaves smoking a black clay pipe, and scrubbing away steadily.

"Where are my things, aunty?" I asked.

She looked round. "Dere's two coloured gentlemen come to de settlement dis week," she told me, "and yo' white men will hab to wait."

In Florida, as elsewhere, the Englishman usually gets on well with the negro. The two seem to understand one another. The old-fashioned Southern gentleman, who was usually of pure Anglo-Saxon origin—he, also, could always handle the negro, and the relations between the two were very pleasant. It is the Yankee who has done most to spoil the coloured people. It is no use attempting to educate coloured children on the same lines as white. The two races are fundamentally different, and the "black man and brother" theory never did, and never will, work. But I am getting on to very contentious ground, and had better, perhaps, say no more on this particular subject.

Queer fish—Remittance Men—Boyce and the Borrowed Grove—Macallum and The Alligator—Some Quaint Ladies

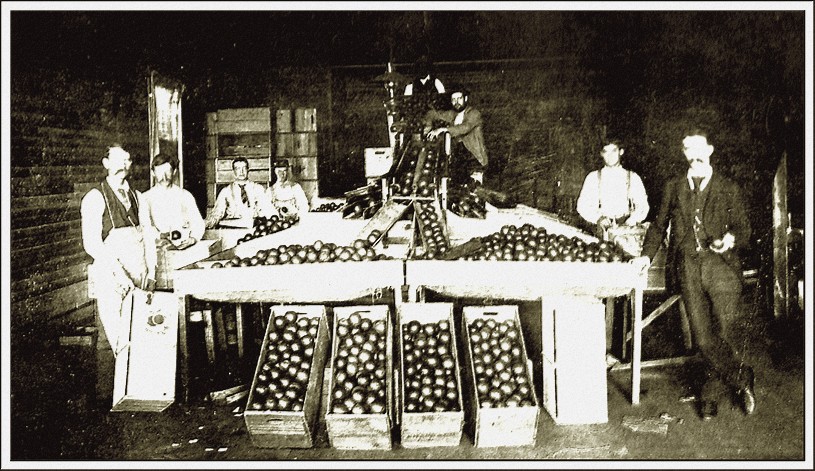

IT was poor luck for me that the place which my father had bought for me was so far from any of my fellow-countrymen. It was three miles from Winterpark, five from the county seat of Orlando, and quite six from the big English settlement on Lake Conway. Around Lake Conway there were at that time nearly a hundred English people—a few families, but mostly young fellows who batched it, either alone or in couples. There were also a good many English folk in and around Orlando, among them the two who ran the English Club. One of these was an old Marlborough boy, the other an old Cheltonian, and they were among the few who made any money. It was the custom for us all to ride into Orlando on Saturday afternoon and meet in the club, where we drank quantities of excellent iced lager beer and played billiards or pool on the only full-sized English table which existed in those days in South Florida. We supped in one of the restaurants, where a capital meal was to be had for a quarter (one shilling). Even the best hotel—the Magnolia—charged but fifty cents for supper.

Living, I may say, was wonderfully cheap in those days, which was as well for us, for we were all precious hard up. You could buy Florida beef for as little as five cents (twopence halfpenny) a pound, and, since anyone could grow all the sweet potatoes he could eat, there really was no reason for anyone to starve. The best tobacco, seal of North Carolina cut plug, cost sixty cents (half a crown) a pound, sound rye whiskey could be had for three dollars (twelve and sixpence) a gallon, and other things were in proportion. The only expensive matters were horse feed—all imported from the North—and clothes. But clothes did not worry us much, for a flannel shirt and an old pair of riding-breeches were the regulation attire, and store clothes were only needed during the short winter season, and then but occasionally. In summer the less clothes one wore the better. I have seen a man ploughing his orange-grove dressed in an old suit of pyjamas. When the heat and the flies became too trying he left his horse to graze while he ran down to the lake and jumped in, pyjamas and all, to come back a few minutes later, dripping but refreshed.

Most of the English orange-growers were steady-going fellows who were making a real effort to gain a living from the soil. But among so many we had all sorts, and some were very odd characters. One whom I particularly remember was the perfect type of a remittance man. I do not know why he left England, but it was probably for his country's good. At any rate, his people had banished him, giving him a hundred a year, paid monthly, and five acres of land. He loathed the country, and vowed that nothing would ever persuade him to grow an orange-tree, and he refused to clear even enough of his land to make a garden. He built himself a two-roomed shack in the thick of the pine-trees, and lived with no company but a bulldog and a squirrel. All his books were law books, from which it was inferred that he had once been a lawyer, but no one knew for certain, and it was not considered the thing to ask pertinent or personal questions. When his cheque was due, Lane, as I will call him, walked into Orlando, and his first care was to buy enough food and tobacco to keep him for the month. Then he went to the club or the nearest saloon and blew the rest. He was, at best, a sombre, reserved sort of person, and the more rye whiskey he absorbed the more silent he grew. When the last dollar was gone he walked home, and remained in seclusion for the rest of the month.

Lane was the means of nearly finishing my career, and this is how it happened. One Saturday night I met at the club a friend named Vivian, who asked me to spend Sunday with him at his place at Conway. "I'm flush," he told me, "and I've hired a buggy from Bob Hyer to take us out." The buggy, drawn by two fine Kentucky horses and driven by a nigger, arrived for us about eleven, and we started out. I remember that it was a brilliantly moonlit night, and, for Florida, rather cold. A mile out of town we saw a huge, gaunt figure seated on a log beside the track, his chin on his hands, which were resting on a heavy walking-stick. "It's Lane," said Vivian, and, ordering the nigger to pull up, asked Lane if he would like a lift. Without a word Lane got in, and we drove on. We had gone some distance, and were on a slight slope where the track ran down to a small lake, when, without the slightest warning, Lane sprang up, and, with a hideous yell, smote the off-side horse over the quarters with his stick. In an instant both horses were running away. Vivian and I seized Lane, flung him down, and sat on him, but the mischief was done, and the horses, quite beyond control, were galloping, hell for leather, down towards the lake. There was nothing to do but sit tight and pray hard. Next instant we were in the lake, but, happily for us, the water was shallow and the bottom firm, so, with our help, the nigger managed to check the horses before they got too far in. Soaking wet, but otherwise none the worse, we pulled back on to the track and reached Conway in safety. But Lane was showing symptoms of D.T., and, as I realised that he could not be left alone, I decided to stay the night with him. A beast of a night I had, too, for there was no firewood cut, and, cold as it was, I could not light the stove until daylight enabled me to go out and use an axe.

The sequel is the oddest part of the story. Returning to Orlando on the following Monday, I met Bob Hyer, the livery keeper, looking very solemn. He told me that the horses had turned up about two in the morning, but without the buggy or the nigger. The buggy was found in the woods, smashed to atoms, but of the driver there was no trace. Nor was anything ever heard again of that nigger, and to this day no one knows whether he is dead or alive. Lane, it seems, must have left a bottle of tanglefoot in the buggy, which the nigger found and finished. Then, presumably, he lost control of the horses, and they bolted again. But whether he was flung out and killed, or whether he was merely so scared that he decamped, remains a mystery.

Another queer fish was a gentleman whom I will call Boyce. Like me, he was a parson's son, and, when he arrived in the State, was every bit as green as I. But presently he developed great skill at games of chance, especially poker, and became also a first-rate shot and billiards player. Such pursuits do not tend to success in orange-growing, and, anyhow, Boyce voted any sort of farming a bore. So, when his father sent him a thousand pounds to buy a grove, he found other uses for the money. A year or so passed, and one day Boyce appeared in the club with a very long face. "Here's a devil of a mess," he told us. "My father has just written to say he's coming out to Florida for the winter. He wants to see how my grove is getting on. The deuce of it is I can't stop him, for he's started already." A shout of laughter interrupted him, but Boyce did not laugh. When the first merriment had died down a man named Dane spoke up. "All right, Boyce," he said, "I'll lend you my grove. I'm going over to Havana for three months," he explained, "and if you'll live in my house and look after it, you can have my grove while I'm away, and tell your father it's yours." He turned to us. "You chaps will back him up," he added. Of course we promised, and a week later Boyce was installed upon Dane's place, while the rest of us waited on tiptoe of expectation for the arrival of papa. But Boyce Senior never turned up. He got as far as New York, where he caught a severe chill, and, after a fortnight in bed, went straight back to England. I have often wondered what would have happened if he had arrived, and once I went so far as to make the incident the subject of a short story, which I called The Pinelake Conspiracy.

Later, Boyce came in for a fifty-pound legacy, and decided to visit New York. Boyce, I should explain, had a round, innocent face, and no one could possibly have mistaken him for anything but a Britisher. It was the off season, and the only other passengers on the boat out of Savannah were four "drummers" (commercial travellers), who at once settled down to poker in the little deck smoking-room. For the first day Boyce watched them in silence, and apparently none of them thought it worth while to speak to him. On the second day the sea was rather rough, and one of the drummers remained in his cabin. To make anything of a game at poker four players are needed, and one of the three survivors enquired of Boyce if he would care to come in. Bashfully Boyce agreed, but at the same time protesting that he was no expert. "I don't reckon any of us ever supposed you were," returned the drummer rather drily. Of the exact course of events during the next two days I have no record; but this I do know—that, instead of spending one week in New York, Boyce bought a first-class ticket to Liverpool on a Cunarder, and was away for rather more than three months. Those drummers, I fancy, were afterwards cautious about inviting youthful and innocent-looking Englishmen to share their amusements.

Years afterwards—I think it was in 1898—Boyce turned up one day in my London office, looking stouter, but still cheery. "I heard you were in town," he said, "and you're just the chap I want. Can you come to a dance to-night?" Anxious for a yarn with Boyce, I agreed, and he told me to meet him at six-thirty at King's Cross. From King's Cross we took train to a station some twenty miles north of London, where a well-appointed carriage met us and whirled us out to a large house, where we were hospitably entertained to an excellent dinner. After dinner the carriage took us to the dance, which was held in a big hall, and everything done in first-rate style. About two in the morning a special train took us back to London, and Boyce and I parted very cheerfully, he promising to come and look me up on the following Saturday. But he never appeared, and I have not since seen or heard of him.

Another queer fish was Lorton. He was a little shrivelled person of uncertain age, who had spent his youth—and, I presume, his money—in London. He had been one of the Piccadilly "mashers" in the early eighties, and he still wore an eyeglass and had the old trick of shooting his cuffs. He was "stony broke," and made a living by cooking for two other men with whom he lived. I liked him, and once asked him to stay the night and come to a dance at the Seminole Hotel at Winterpark. He turned up on a borrowed pony, with a dress suit, a relic of his youth, in his saddlebags. It was made of that old-fashioned glossy cloth, and, from being tightly rolled up, had developed a million wrinkles. I shall never forget his quaint appearance under the brilliant electrics of the big parlour where we danced. I introduced him to a plump little American girl, whom he led into the centre of the room and twirled round and round until she was so giddy that she sat down flop on the floor, bringing him with her. She was not pleased with me.

The stories of stingy Scots are as numerous as they are libellous to a kindly and hospitable nation. The meanest man I ever met was of English extraction, and lived in Florida. A friend of mine, a big, burly man of enormous muscular strength, was out duck-shooting one day in a boat upon a lake, when, in some way, the gun was accidentally discharged, and nearly blew its owner's left arm off. The accident was seen from the shore, and the sufferer was quickly brought to bank and carried into the nearest house, the residence of the mean man, where he was laid upon the parlour floor while his rescuer did his best to stop the bleeding. A doctor was at last fetched, the dreadful wound was properly bandaged, and the injured man taken to hospital. Before he recovered he received a bill from the mean man for the price of a new sitting-room carpet—"spoilt by your bleeding over it," ran the missive.

Speaking of Scots, there was one named Hugh Macallum who had a pretty place near Winterpark, but who always struck me as the last man who should ever have come to a new country. His house stood on rising ground above a small circular lake, which was perhaps a quarter of a mile across. The whole of the shores were planted with orange-trees, and there were several houses facing the water. One day Macallum's nigger came running up. "Dar's a mighty big 'gator down in de lake," he exclaimed. "Cain't yo' shoot him, boss?"

Macallum was the proud possessor of a rifle—an old Snider belonging to the Dark Ages of the British Army, a weapon of great weight and with a kick like a mule. Armed with this, he hurried down to the lake, and there, sure enough, the ridged back and bony head of a large alligator showed, floating on the glassy surface, out in the middle of the lake. Taking careful aim, Mac pulled the trigger, and a roar like that of a small cannon sent the echoes crashing along the lake-shore. "Did I hit him?" gasped Mac, rubbing his bruised shoulder.

"No, sah," said the nigger. "Dat dere gun throws high. Yo' went a big way ober him. Ah seed de bullet jist a-skippin' ober de water. Ah guess—" He pulled up short. "What's dat?" he exclaimed.

"Dat" was a sudden bellow of wrath from the opposite side of the lake, and from among the orange-trees a very tall, burly man, followed by a woman and a tribe of children, came running down to the water's edge. The man was carrying some large, round object, and Mac and the nigger and the rest of us stood watching in paralysed silence as the big man and one of the boys got into a boat and came pulling furiously across. They soon reached our side, and the man—he was a big, ugly cracker named Marriner—jumped out and came striding up to Mac. Under one arm he carried a large clock, and this he thrust under Mac's nose. "Gol dam ye!" he began furiously. "Look at that!" Mac looked with horror at a gaping hole in the clock face, while Marriner forcibly expressed his opinion of "blamed fools as shoots off guns without a-knowing whar the bullet's a-going." What had actually happened was that the heavy Snider bullet, ricochetting from the surface of the lake, had gone right through a window of Marriner's house, passed over the heads of the family, who were eating their midday meal, and buried itself in the clock. I don't know how much it cost Mac to square Marriner, but he was very sad for days afterwards.

Macallum had a brother-in-law named Harold Johnstone, who ran his place for him. Johnstone had knocked about in South Africa and elsewhere, and was a delightful companion and a very great friend of mine. He was a wonderful musician, and had all the old Gilbert and Sullivan operas by heart. Anything he had heard once he could reproduce on the piano. In summer, when Macallum was away, Johnstone stayed South and looked after the grove, and I often went over and spent the night, for the place was less than two miles from mine. The next house to Macallum belonged to two elderly American ladies, Miss Brown and Miss Macluer. They had been missionaries in their youth, and had retired to end their days in sunny Florida.

Johnstone had an old black horse, commonly known as the Polished Skeleton, and with this he used to plough the grove. His language as he ploughed was more peculiar than picturesque. It was just a habit he had picked up, and meant nothing at all, but it must have been a bit terrifying to those who did not know him as I did. One day, when I turned up, I found him looking puzzled and rather annoyed. "I say, Bridges," he remarked, "those two old women have gone crazy. Look at their windows!" I looked, and saw that the two windows of their house facing the Macallum grove had been covered with brown paper pasted over them.

I roared with laughter. "It's your language, Johnstone," I told him. "It's the way you talk to your horse. I told you there'd be trouble." Johnstone was quite upset, but, happily, matters righted themselves. A few days later Johnstone, working in the grove, heard shrieks from the lake-shore, and, running down, saw little old Miss Macluer hanging on desperately to a fishing-rod. She had apparently hooked something so big that it was on the point of pulling her into the water. He seized the rod and landed a three-foot alligator, which had taken the old lady's bait. This gave a chance for explanation and apologies. The brown paper was removed, and all went well. But the old ladies themselves were a source of endless amusement to the rest of us. They had a small jack donkey, to which they were greatly devoted, and which they used, not only to drive, but also to cultivate their grove. I have watched them ploughing, Miss Brown holding the plough-handles, while her friend walked alongside the donkey, holding over its head a large green umbrella, presumably to save it from sunstroke.

Another quaint old lady with whom I had a good deal to do was a Mrs. Sweetapple, who owned a large grove, a feeble husband, and a pretty daughter. She also had a Swedish maid who was an excellent cook. One night Mrs. Sweetapple was awakened by a sound of voices, and, getting out of bed, went to the window. The maid's room was over the kitchen, and presently she became aware that a man was standing beneath the maid's window and talking up to her. The man's voice was that of Ezra Tuckett, a neighbour of Mrs. Sweetapple, and it was clear that he was trying to persuade the maid to leave her present employ and come to work for his wife. Burning with indignation, Mrs. Sweetapple hurried downstairs, and returned carrying a large and over-ripe water-melon. This she flung from her own window with such good aim that it hit Tuckett on the back, just between the shoulders. When Tuckett recovered a little, he found himself flat on the ground, soaked to the skin with the squashy contents of the melon, and in the most filthy mess imaginable. Mrs. Sweetapple preserved a stony silence as from her window she watched him sneak away.

Mr. Sweetapple was afraid of his wife, and usually her obedient slave. One day she ordered him to mend the roof of the barn, and, as usual, he did as he was bid. At twelve Mrs. Sweetapple sallied out. "John, it's dinner-time," she said. "You come down."

"I'll come when I've finished," replied John.

"You come right now," ordered the lady; but for once John proved recalcitrant.

"I'll finish first," he answered.

Mrs. Sweetapple said no more, but, going into the barn, put the harness on her old horse, attached him to the buggy, and drove off to Orlando, where she stopped at the house of Sheriff Anderson. Anderson came out—a big, quiet, bald man with a long, tawny moustache.

"Sheriff," said Mrs. Sweetapple, "I want you to come right back home with me. John's gone crazy."

"John gone crazy!" repeated Anderson in amazement.

"Yes, he's surely crazy. He won't do what I tell him."

Later on I did some work for Mrs. Sweetapple, but that comes later in my story.

Some Small Adventures—Wilton and The Alligator—Swimming in a Dress Suit—Locked Out in the Rain—The Death of Tom Stanley

MAN, it is said, was not made to live alone, and certainly living alone is a dull business for a youngster not yet twenty years old. To get up and cook one's own breakfast, to go out to work, to come in for lunch, go out and work again, to end the day by cooking a solitary supper, then reading until bedtime, is the sort of life that a boy may stick for three or four days at a time—but hardly more. It was not so bad when one was really busy about the place, for then one was so tired that one slept like a log, but in summer, when things were slack in the grove, and when, in any case, it was too hot to work between twelve and three, it was pretty trying. The men in the settlement at Conway could always visit one another's houses in the evenings, but, as I have explained, my place was miles from Conway, and I had no near neighbours. Sometimes a week went by without my exchanging a word with another human being. It must be remembered that there was no delivery of post, no newspaper, and that books were rare and hard to come by.

For the first year of bachelor life on my grove I had not a pony, so wherever I went had to be on foot, and let me tell you that walking on roads ankle deep in dry sand is an exhausting sort of amusement—particularly so in summer, when the day temperature rarely falls below seventy-eight degrees, and is more often ten degrees above that figure. Even so, I usually footed it into Winterpark two evenings a week, where I collected my mail, if there was any, and chatted with the postmaster or one of the storekeepers. In those days I walked considerable distances. On one occasion I tramped sixteen miles to Clay Springs, through the pine-woods, and, after spending the night with some friends, walked back next day. Sixteen miles is a fair walk on a made road, but try it on a dry, sandy beach—a fair counterpart of a Florida road in the last century.

Now and then a friend—Harold Johnstone or Vivian, or a young scapegrace named Hudson—would arrive at my place to spend the night. These were great occasions, when I spread myself on cooking a top-hole supper, and then afterwards we sat out on the verandah smoking corn-cob pipes, twanging an old banjo, and singing all the songs we could remember.