RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

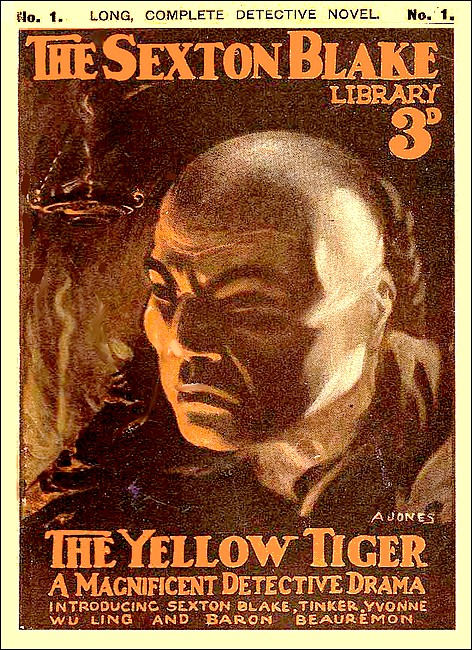

The Sexton Blake Library, September 1915, with "The Yellow Tiger"

Sexton Blake

Introducing Wu Ling and Baron de Beauremon

THE island of Marsey, which lies just off the Welsh coast beneath the frowning cliff of Pembroke, is as lonely a spot as one will find in all the kingdom. It forms a rough triangle in the sea, the legs of which are each about two miles in length. One small bay alone permits a landing, and with that exception the shores are high, rugged cliffs, the haunt of the sea-bird and the home of Neptune's thunder.

The island itself is almost devoid of habitants or habitations. One large bungalow, built by a former owner, gives on to the small cove where a landing-stage has been built; and a second, the only other building, is an ancient farmhouse, fashioned centuries ago from rudely-hewn timbers, and at present the home of the farmer-fisherman, tenant of the present owner of the island.

For the rest, the island is the grazing-ground of sheep and cattle belonging to the owner, and which are looked after on a share basis by the farmer. Beyond that the rabbits hold sway, falling by thousands each year into the traps of the farmer.

A narrow sound of less than two miles in width separates the island from the mainland, yet, narrow as is that sound, it was, in days gone by, the scene of many stirring scenes when smuggler and excise man met and clashed together.

No lighthouse is there to send forth its beacon each night to the ships which pass up and down the wide highway beyond, and for that reason it is a place shunned by the mariner and fisherman alike. For years it formed part of a large estate on the mainland and was seldom favoured by the visits of the landlord.

But lately when that estate was broken up it was bought in by a man who was a stranger to the district, and who, though well-known in certain quarters, was unknown in name or fame to the local inhabitants.

The purchaser was Baron Robert de Beauremon, president of that daring criminal organisation known as the Council of Eleven. Why he had bought it, or to what purpose he intended to put it, none knew.

The farmer tenant was informed by Beauremon's solicitors that the stock on the island had been bought by Beauremon, and that the arrangement which he had with the former owner would continue as usual. To the farmer-fisherman this was satisfactory, and he continued his duties as usual, scarcely troubling himself with thoughts of the new owner.

But a mild feeling of excitement filled him when he received a letter informing him that Baron Robert de Beauremon was coming to the island with some friends, and requesting him to get the bungalow in order. The tenant proceeded to do so, remarking to himself that the owner had neglected to say how he would arrive or by what means he would get across to the island.

Three days later he was enlightened with something of a shock, when, as he stood on the landing-stage in the little cove, he saw what at first appeared to be some strange colossal bird high overhead and winging its way towards the island.

As it approached, it grew larger and larger until, to the startled gaze of the tenant it resolved itself into one of the great air machines of which he had read and seen in pictures, but which he had never witnessed in reality.

Nor was his astonishment any the less when it swooped down towards the island and came to earth on a wide stretch of level field where cattle grazed. The beasts with tails in the air tore off madly towards a distant wood, and the farmer, running towards the spot where the huge biplane had come down, met two men climbing out of the cockpit.

One of them, a tall, fair man of commanding presence, removed his flying helmet as the tenant came up, and, smiling genially, informed him that he was the baron. The other man he indicated as Senor Gonzalez, his friend, following up the statement by asking if the bungalow had been got ready. The tenant, scarcely able to reply from the amazement which filled him, stammered out an affirmative and led the way towards it.

Then he was kept on the move as he had never been before. The new owner wanted this and that attended to, and nothing would do but he must make a complete tour of the island that very day.

For two days he was here, there, and everywhere, and then on the third night there was a new arrival. The farmer-tenant knew not whence he came. His first knowledge of the arrival was when the baron and his friend arranged a strong light on the landing-stage in the cove, and by its beams lighted in a large motor-boat which arrived late at night.

The tenant received a further shock when he saw that the new arrival was a Celestial, and that the one man who formed the crew of the motor-boat was also a Chinaman.

Then the two new arrivals disappeared towards the bungalow with their host, and the tenant saw no more of them for twenty-four hours.

But had he been able to conceal himself beneath the wide balcony of the bungalow he would have heard something which would have given him cause to think.

That same night, when the new arrivals had been refreshed by a plain but plentiful meal, Baron Robert de Beauremon and one of the Celestials went out on to the balcony, and seating themselves in low wicker chairs bent towards each other.

It was the baron who spoke first.

"How do things progress, prince?" he asked in a low tone, though in truth they had only the sea-birds for eavesdroppers. Prince Wu Ling—for it was he—shrugged slightly.

"My arrangements are complete," he replied. "It is only for you to say the word." Beauremon was silent for a little, then he said:

"When you first made the proposal to me, prince, I was dubious of its possibilities, but as I told you then I was and am prepared to go ahead with it, providing there was sufficient in it to tempt me. Of course, you know about the Council of Eleven, and will understand that we can only take on propositions which promise a large reward. It takes a lot of money to run such an organisation as the Council of Eleven, and we have been a little unfortunate lately.

"However, I am down here to listen to a definite offer, and if I take it up I am ready to act at once. If not—well, you will be a welcome guest as long as you will honour me with your presence."

"You speak fairly, baron," responded Wu Ling. "I understand the difficulties which are yours, and I understood them before I approached you regarding this affair. But I think the financial reward will be sufficient for you.

"Some time ago—it matters not exactly when—I was in communication with certain sources to whom Britain's power and present policy are inimical. At that time I joined forces with these people, and it was my intention to carry out for them certain operations in return for which they offered me their assistance in affairs which are very near my heart.

"I shall not bore you by a relation of the first step in this agreement. Sufficient is it to say that owing to laxity on the part of someone it was a failure, due principally to the meddling of a man whom you have reason to hate as much as I."

"You mean—" said Beauremon.

"I mean Sexton Blake," replied Wu Ling curtly. "Time and again has that man intruded himself upon my affairs, but one day—one day—ah! my friend! one day he will fall into my power. Then—" And Wu Ling finished with an expressive shrug. "But that is beside the question," continued the prince. "As I said, the first affair was muddled. It is my intention that there shall be no muddling in the second. For that reason I have laid my plans carefully, and have sought you, baron. Together we can do much.

"If we are successful it will take not more than a week of your time. If we are unsuccessful—but I will not consider that possibility. I am determined that we shall be. For the reward I can promise you a substantial sum for our co-operation. I am prepared to offer you ten thousand pounds down and, if success is ours, add to that another ten thousand."

"That would make twenty thousand in all," murmured the baron. "Make it twenty-five thousand in the event of success, prince, and my answer is 'Yes.'"

Wu Ling shrugged.

"As you will," he replied. "It shall be twenty-five thousand. And now to the details. My present allies are, as I have already told you, interested in certain affairs here in England. They have planned a series of coups, all of which lead up to a main coup, the nature of which even I do not know.

"I speak of the Germans. To them I have promised my aid, in return for which they give me theirs, as I have told you. Now I understand, baron, that it is an essential part of the conditions governing the Council of Eleven that there shall be no question of creed or country to influence your operations. Am I right?"

Beauremon nodded.

"That is quite right, Prince Wu Ling. The Council of Eleven is prepared to work for anyone, providing the price is paid."

Wu Ling smoked in silence for a few moments, then continued:

"Do you know the new British Minister of Munitions, baron?"

"I do not know him personally," replied Beauremon. "But I have seen him often."

Wu Ling held up one thin, yellow hand.

"Baron, that man is one of the geniuses of the age. He is probably one of the best-hated and best-loved men who ever lived. When he is spoken of there is no lukewarm sentiment expressed. It is either profound admiration or violent dislike. Yet no man has been watched more closely by the enemies of Britain than he. And it is true that these British pigs owe a vast deal to his brains.

"He has been the strong man at the helm—it is his keen mind which has seen through the muddles created by others, and now when the British have at last awakened, and have begun to realise that only strenuous measures will meet the tremendous demands upon them, they have had the sense to turn to this one man to lead them through the maze.

"With his usual promptitude he has risen to the demands made upon him, and when I say that he is the greatest enemy Germany has, I only speak the truth. Therefore, you will not be surprised to know that Germany is determined to remove him from the scene. Without him some muddler will take charge of things, and that will be another step ahead in the German programme which aims to lull this country into a state of security until the Germans are ready for the grand effort. Do you follow me?"

"Perfectly," responded Beauremon. "Proceed, please."

"It is to seek your assistance in removing this man from the scene of affairs that I have sought your aid," went on Wu Ling. "This island is, as it happens, ideally situated for the purpose. Your organisation will complete the circle of conditions necessary to make the situation perfect. Now I have learnt that this Munitions Minister is to leave London tomorrow night by motor-car for North Devon.

"He will visit at Northam, which is near the Westward Ho! golf-links, and on Saturday and Sunday will play golf. Golf is his only relaxation at present, and the only means he has of keeping fit while working at the pressure he is. I have a plan of the golf-links, and will show it to you.

"In a word, my plan is to get possession of the person of the Munitions Minister while he is playing golf at Westward Ho! With your assistance, and the use of your passenger-carrying aeroplane, I am strongly convinced that the thing can be carried out successfully. That is the proposition, baron. Are you prepared to take it up?"

Beauremon did not reply at once, but smoked thoughtfully for some minutes. Finally he roused himself.

"It is a highly dangerous proposal you outline," he said slowly. "If it can be brought off it will be one of the biggest coups on record—to kidnap a British Cabinet Minister! Nor would that be the end of it. The moment his absence was discovered, the best brains in the country would be at work to discover his whereabouts, and it would have to be a lonely place indeed which would suffice to hide him.

"But he wouldn't be kept hidden long," murmured Wu Ling softly. "A few days only would suffice, then he would never more be seen in this life."

"So that is the game, is it?" muttered the baron. "Frankly, prince, I don't like it. But I said I was prepared to enter into any arrangement you proposed, providing the price was sufficient, and I will not draw back. But we shall have to tread very warily indeed. This particular Cabinet Minister is no fool, I assure you."

"He is a dog, and will meet the fate of a dog!" rejoined Wu Ling passionlessly. "And since that is agreed upon, baron, suppose we call the others and discuss the details with them?"

Beauremon rose, and going to the door which led into the living-room of the bungalow, spoke in a low tone to the two men who sat there. One, a stout, powerful-looking Chinaman, rose at once, and bowed politely, waiting until the other man should rise too.

Had it been possible for Sexton Blake, the great London criminologist, to have peeped into that room just then, he would have recognised the Celestial as San, the shrewd and faithful lieutenant of Prince Wu Ling. And it was by this name Beauremon also knew him.

The other man, a small, swarthy-looking individual, whose every movement was as lithe as those of a panther, was Gonzalez, the Spanish member of the Council of Eleven, and the aviator of that organisation. He it was who had driven the great passenger-carrying biplane which had brought Beauremon to the island a few days before.

Both he and San followed the baron out on to the balcony and joined in the discussion. Until far into the night they talked, and when they finally rose to retire, all the details had been settled.

So as they sought their rooms with the distant pounding of the waves, the only sound to break the quietude of the lonely island, they had completed their plans. And at daybreak they began to put them into operation. Beauremon was abroad just as morn mounted out of the East.

The other three appeared on the balcony soon after, and when a hasty breakfast had been consumed, they all made their way to the shed where the biplane had been left. Gonzalez and Beauremon wheeled it out, and for some minutes the Spaniard was busy tuning up. Then he signed to the baron that the machine was ready, and the baron turned to Wu Ling.

"It is ready, prince. Shall we get along?"

Wu Ling nodded, and Beauremon led the way into the hangar. There he and Wu Ling donned flying clothes and fitted helmets on their heads. That done, Beauremon made his way to the biplane and climbed in, followed by the other. When they were settled in their places Gonzalez started the engine, and immediately there sounded a terrific roar as the Gnome barked out and the great propeller whirled.

San and Gonzalez held the machine until Beauremon gave the sign to let go, then the biplane shot ahead quickly, running along over the long stretch of level ground until Beauremon tilted the lifting planes. She answered immediately, and like a great bird shot upwards with incomparable grace.

Setting her to climb in a wide, sweeping circle, Beauremon settled in his seat, and from time to time glanced down at the water below, which was slipping away beneath them at the rate of seventy miles an hour.

Wu Ling, looking like some yellow sphinx from the past, sat motionless in his seat, his eyes fixed straight ahead and his arms crossed. For all the emotion his features displayed he might have been hammering along Piccadilly in a taxi instead of sweeping through the air at a terrific speed.

By the time the biplane had made a complete circle, bringing her nose back to the east, they had climbed to the two thousand foot level, and now, directly below them, the blue water of the Bristol Channel twinkled beneath the morning sun.

Far to the left the rugged line of the Welsh hills showed misty blue and black; to the right stretched the ramparted coast of North Devon; while behind them lay St. George's Channel, which broke on the coasts of Ireland.

The day itself gave promise of being perfect. Not a cloud flecked the unfathomable blue above, and at the two thousand foot level the soft August breeze caught them caressingly. It was an ideal day for flying.

Beauremon set the cloche for a very gradual climb, and picking out two tiny patches of black smoke, which came from steamers far below, steered a course midway between them.

At three thousand feet Beauremon set his right foot forward on the steering-bar, and ever so gradually the huge biplane swung southwards. Still she was climbing, and by the time they were at the four thousand foot level she was heading due south with eighty miles an hour being ticked off on the speed indicator.

Suddenly, far, far below them, a small dark blotch appeared. It looked like nothing so much as a dirty grey chip floating in a wide basin of blue, but when they had drawn almost directly over it, Wu Ling leaned forward, and, cupping his hands, shouted:

"Lundy Island!"

Beauremon nodded, and drew back his foot a little. The biplane swerved eastward again and swung along until Wu Ling again leaned forward and pointed down. "There!" he called.

Beauremon looked over the side. The distant Welsh coast now only showed as a dark line to the north. The coast of North Devon was immediately beneath them, and where the sea broke against it there showed a long line of white.

Gauging the shore-line with a careful eye, Beauremon tilted the planes and set the biplane to descend in a long volplane. At two thousand feet he shut off the engine, and, shifting the rudder-bar a little, took the descent in a gradual spiral.

Lower and lower they dropped until the beach below seemed to fairly fly to meet them, then as it became still more distinct, Beauremon headed for a wide part which lay glistening white beneath the sun. The nose of the biplane came round slowly as they spiralled, then they slid towards the landing spot; the wheels touched the sand, there was a slight shock as the skids took the ground and they ran along easily to stop just where a tiny sand dune rose. It was a perfect descent and a faultless landing.

For a few moments after the machine came to a stop both Beauremon and Wu Ling kept their seats, gazing up and down the beach. They fully expected some wandering fisherman to come along and gaze with wonder at the strange machine which had dropped from the sky, but at the end of a quarter of an hour there was still no signs of anyone, so they descended and stood on the sand by the biplane.

Beauremon drew out his watch, and, turning to Wu Ling, said:

"We were wise to come early. It is only ten minutes to six now, and it looks as if we had managed to come down without being seen. I was certain the coastguards would see us." Wu Ling shrugged.

"They may have done so, and even if they have, what care we? I have seen to all that. I have papers in my pocket which will serve to lull the suspicions of any coastguards. But come, let us wheel the machine along to the spot I have chosen in which to conceal it. Your landing has brought us less than a hundred yards from it."

They both took hold of the biplane, and, turning it, began to trundle it along the beach until they came to a thick patch of wood. There Wu Ling made a sign, and after a close scrutiny of the beach, they ran the machine in under the cover of the trees. Nor did they stop until they had succeeded in thrusting it into a deep tangle of cover which would have hidden two machines. And there Wu Ling snowed how carefully he had planned things.

"I have been in Cardiff for weeks," he said, as they sat on the ground beneath the machine. "I came over here several times in a motor-boat, and after choosing this spot, set about to prepare it for the reception of an aeroplane, for I knew that if this affair was to be brought off it could only be done so by the air. I'll wager no passing coastguard will discover this spot. It will be uncomfortable remaining in this wood for two days, but the prize is worth it. We have sufficient food and drink, and can manage to amuse ourselves in some way."

Beauremon smiled.

"We shall manage all right," he replied. "Our man comes down to-night, doesn't he?" Wu Ling nodded.

"Yes. To-morrow he will be playing on the links close by, and we may get a chance then to get him. If not, we shall have to try Sunday. I have here a plan of the links, and in your spare time you can study it."

So Beauremon, with that cool insouciance which was such a deeply-ingrained quality of his nature, lighted a cigarette and proceeded to study the plan of the golf-links which Wu Ling gave him. And the Celestial! What of him? Squatting on the ground he turned his gaze towards the sea, and for hour after hour sat there like a yellow sphinx, calm, all knowing, and inscrutable.

All that day did this oddly-assorted couple sit there in concealment, but in the evening Beauremon slipped off his flying clothes, and making his way to the sea bathed his face and hands in the cool brine.

Then he walked along the beach until he came to the village of Westward Ho! where he struck off across country. He kept on until he reached Northam, and, following Wu Ling's instructions, took the road leading to the residence of Mr. Grindley Morrison, one of the big land holders of the district and a former member of Parliament. It was this place which Wu Ling had said the Munitions Minister would visit.

There Beauremon lay concealed, until late that same evening a powerful motor-car drove along the road and stopped before the main gates of the place. While it waited for the gates to be opened, Beauremon slipped along in the shadow, and by the reflected glow of the powerful road lamps caught a glimpse of the occupants.

Then as it drove up the long approach to the house he started back for Westward Ho! well pleased with the result of his scouting mission. He had seen the Munitions Minister in that car.

The next day Beauremon and Wu Ling lay concealed in the wood close to the golf-links, watching, watching always for the opportunity they sought. Hours went by. During the morning they saw the Munitions Minister and another gentleman playing a round, but on that occasion no opportunity presented itself to put into operation their plan.

In the afternoon the same thing occurred, but so closely guarded was the Minister that they were compelled to return to their place of hiding that evening without having made a move.

Sunday morning they were once more on the spot, but the conditions were even worse than they had been the day before. Instead of two men, four were playing, and when after lunch the same thing occurred, it began to look as if all their efforts were to be crowned by nothing but rank failure. Still they lay there, watching like hawks for their prey to come within reach, and after tea on Sunday afternoon their chance came.

The Munitions Minister came in sight, swinging one of his golf clubs and smiling softly to himself at the result of a particularly fine drive which he had made from the fifteenth tee. Far in the distance the watchers could see another figure topping the rise, which they recognised as the man who had been with the Minister constantly, and who Beauremon knew to be Sir Hector Amworth, the head of Amworth, Strong & Co., the great heavy-gun makers.

They watched closely while the Munitions Minister, who was carrying his own bag of clubs, selected another club, and approached the spot where his ball lay.

It brought him less than twenty yards from the spot where Wu Ling and Beauremon lay concealed. From there they could see that it was a brassie which he had chosen, and Beauremon, holding up a cautioning hand, peered out while the Munitions Minister raised the club to strike the ball. Then, half-rising, the baron opened his lips, and, in a somewhat muffled voice, called:

"Help! Help!"

They saw the Munitions Minister pause even as the club was above his shoulder and listen. Again Beauremon called, this time in a tone even more muffled than before, and then they saw the Munitions Minister turn and look towards the wood where they lay.

The next moment he had shouted something at the top of his lungs to his distant companion, and, turning, raced towards the spot from which the cry had come. As he did so, Beauremon and Wu Ling rose, and, as the Munitions Minister dashed into the wood, they both launched themselves at him.

Now, while by no means a powerful man, the Munitions Minister was lithe and active and full of courage. The moment the two men sprang at him, he saw the trap which had been laid for him; but, determined not to be overpowered without a struggle, he raised the brassie which he still carried, and, as Beauremon came at him, struck out with all his force.

There was a cracking sound as the blow got home, and the next moment the club snapped in half as the blood poured from a deep wound in Beauremon's forehead.

The baron staggered, and, had the Munitions Minister taken to his heels, he might even then have escaped. But, instead, he turned to meet Wu Ling's attack, and, as the Celestial struck him, the pair went down together. The Munitions Minister just had time to call for help to the companion whom he knew must be near, and then Wu Ling's fingers closed on his throat.

Beauremon, who had recovered a little from the blow which he been dealt, also took a hand, and, picking up the Minister, they carried him through the wood towards the beach. At that same moment, the Munitions Minister's companion dashed into the wood, and, leaving the Minister to Wu Ling, the baron crouched to wait for him.

Sir Hector Amworth came on at full-speed, and, as he passed the tree where Beauremon crouched, the latter sprang, clubbing a heavy revolver as he did so. The next moment Sir Hector Amworth lay full-length on the ground, unconscious. Taking him by the shoulders, Beauremon dragged him towards the beach, and left him close to the wood while he went along after Wu Ling.

The Chinese prince had carried the Munitions Minister to a spot just opposite, where the biplane lay concealed. There Beauremon lent him a hand, and together they conveyed the now unconscious Minister to the biplane.

They dumped him into the cockpit unceremoniously, and returned for the other. He shared the same fate, and then the two daring men—one the product of the mysterious and inscrutable Orient, the other the child of an effete Occident—trundled the great passenger-carrying biplane out to the beach.

Climbing in, Beauremon turned the rear starter, and Wu Ling, who had clambered in after the baron, had just time to sink down in his seat, when, with a roar, the machine started along the beach. A moment later she was mounting, while the water slipped by underneath at seventy miles an hour.

And the only person who saw the exact spot from which the biplane rose was a single boy, who was idling about some distance along the beach.

The Missing Minister—Blake Called In.

"THE Minister of Munitions has disappeared, Blake!"

Sexton Blake gazed thoughtfully out of the window, which looked from the private room of Sir John, Chief of the British Secret Service, on to a flagged and cemented courtyard, but vouchsafed no remark. "The Minister of Munitions has disappeared," repeated Sir John, "and, Blake, he must be found without delay!" Blake nodded, but still remained silent.

"I have got together the facts which are actually known, and have cut out all the theories, of which there have been plenty," continued the chief. "Listen, and I will tell you what is known. On Friday evening the Minister left town in the company of Sir Hector Amworth, of Amworth, Strong & Co., the big munition people. Their destination was Westward Ho! on the north coast of Devon. As you know, the Munitions Minister is fond of golf, and while he is under such a pressure of work it is practically his only relaxation.

"It was their intention to play golf over the week-end, and to return to town last evening by car. Instead of arriving here Sunday evening, as intended, they have not put in an appearance up to now, and, as you see by the clock, it is half-past eleven. In half an hour it will be midday Monday.

"In ordinary times it would be just possible that the Minister might remain over longer than he intended, but certain extremely important matters demanded his presence in town by midnight Sunday.

"One of his secretaries waited up all night for the car to arrive, but when it did not come he got on the 'phone to the house at Northam, where the Munitions Minister and Sir Hector were staying. The result of that telephone conversation caused him to come hot-foot to me. This is what he told me:

"It seems that the Munitions Minister and Sir Hector Amworth arrived in Northam, which, as you know, is very close to Westward Ho! on Friday night, about ten o'clock. I may say that the Press was not cognisant of their destination when they left town. It was merely given out that the Munitions Minister was leaving town for the week-end, therefore unauthorised persons could hardly have known his intentions.

"At Northam they were guests of Mr. Grindley Morrison, the former member from that district, with whom the Munitions Minister is very friendly. It was he to whom the secretary spoke on the 'phone. The Munitions Minister and Sir Hector retired early Friday night, and breakfasted early Saturday morning.

"They motored through the Westward Ho! golf links a little after nine, played golf till noon, lunched at the hotel at Westward Ho! and continued their game during the afternoon. They returned to the house in Northam in time for tea, and spent the rest of the day within the grounds of the Morrison place.

"Sunday morning they again motored through to the links, and this time Mr. Grindley Morrison and a neighbour, Major Colin Hart, went with them. They played a foursome during the morning, which the Munitions Minister and Major Hart won. Then they went on to the hotel for lunch, and played another foursome during the afternoon.

"The car had been sent back to the house in Northam for a hamper, and they had tea on the links. After tea, Mr. Grindley Morrison and Major Hart remained at the club-house while the Munitions Minister and Sir Hector Amworth played round for a small wager. After the sixth hole they disappeared from view, and no more was seen of them.

"Time went on, and the two gentlemen who had remained at the club-house thought the game was taking a long time, but never dreamed that anything might be wrong. They attributed the delay to lost balls. I should mention that no caddie accompanied the players, since it was Sunday, and the Munitions Minister would not have one on that day. At last, however, it got so late that Mr. Grindley Morrison and Major Hart both became slightly worried. They decided to walk out to the eighteenth hole, and work back along the links from there, thinking they would pick up the players about the sixteenth or seventeenth hole. They did so, but worked clear back to the ninth hole without seeing the slightest sign of the players. I believe you know Westward Ho! links, Blake?"

Blake nodded.

"I have played there often, Sir John."

"Then you will know the topography of the golf links there, and will be able to follow intelligently what I have told you. You will remember that the links are situated on Braunton Burrows, on the seashore, and overlook Bideford Bay. You will also be familiar with the position of the different holes, and in your mind can follow the course of Mr. Grindley Morrison and Major Hart as they walked from the eighteenth hole in search of the missing players.

"As I have said, they reached the ninth hole without seeing any signs of them, and not until then did they become really worried at their absence from the scene. They consulted as to what they should do, and Major Hart suggested that they retrace their footsteps to the sixteenth hole, which, it seems, is close to a small wood, which lies between it and the sea.

"They thought the players might have suspended the game for a little to walk through the wood to the seashore in order to admire the view. The two searchers followed this plan, and made their way back to the sixteenth hole. From that green they turned off towards the wood, and, entering it, followed a path which led to the shore.

"About half-way along this path they suddenly came upon a golf-bag containing several clubs, and on the ground beside the bag was the lower half of a driver. The upper half of the handle-shaft they found some distance on. It had been broken, as though under force of a blow, and both bag and clubs they recognised as belonging to the Munitions Minister.

"By now keenly exercised in mind, they followed the path to the sand dunes on the shore, and there found a second bag with all the clubs intact. Mr. Grindley Morrison identified it as the one belonging to Sir Hector Amworth. Close to the bag there seemed to be the marks of several footprints, but so confused were they that nothing could be made of them.

"They went up and down the beach for the best part of an hour, shouting and halloing at the top of their voices, but gained no reply. Thinking, perhaps the two missing men might have returned to the club-house, and anxious to get an explanation of the reason for the two bags of clubs being where they were, they hurried back across the links, carrying the bags with them.

"On their arrival at the club-house, they called the steward and questioned him, but he was positive in his statement that neither of the gentlemen referred to had returned. You can imagine the state of mind in which Mr. Grindley Morrison and Major Hart now were.

"It had dawned upon them that something of a very serious nature had transpired, and, realising the importance to the country of those two gentlemen, set out again to make a thorough search. They went from one end of the links to the other, searching and calling, and not until they reached the tenth green did they hear anything which might by any chance throw any light on the occurrence.

"There they came upon one of the caddies, who had heard their shouts. He said he had spent the afternoon down by the military school, and had seen nothing of the two men for whom his questioners were searching. But he added that late in the afternoon he had seen an aeroplane leave the beach far up past the golf links, and that it had flown in a northerly direction.

"If there had been an aeroplane near the links, it would not be odd that anyone at the club-house should not hear it, for, if you remember, there is a long pebble beach at Westward Ho! which, when the tide is coming in or retreating, makes a loud, booming noise which would effectively drown the noise of an aeroplane engine at that distance.

"As it happened on Sunday, it was high-water at five-thirty, so the booming of the pebbles would continue for the better part of the afternoon, and—so the Munitions Minister's secretary says—Mr. Grindley Morrison informed them it was particularly loud that day.

"Mystified by what the caddie had told them, they walked along the beach to where he had seen the aeroplane rise. There they searched about until they found what may have been marks made by the wheels of a machine as it ran ahead to rise, but they could not make sure. They thought the lad must be romancing, and questioned him closely, but they could not shake his story.

"They sent for Mr. Grindley Morrison's chauffeur, and pressed him into the search. They covered every yard of the links and beach, and made an examination of all the bits of wood which are about there, but the result of all their efforts was nil. There was only a slight hope that the two missing men might have returned to Northam.

"While rather a far-fetched theory, it was always a possibility that a message had come to Northam for the Minister of Munitions, and that his own chauffeur had brought it out to the links. From the road he would follow, he might see them playing and might have taken it direct to the Munitions Minister without the formality of first taking it to the club-house.

"Presuming this, and further presuming that it had been an urgent communication, it is just possible, though, I confess, not probable, that the Munitions Minister and Sir Hector decided to abandon their game, and return at once to Northam without waiting to notify the others of their intention.

"But on the arrival of Mr. Grindley Morrison and Major Hart at Northam, they found that even this hope ended in thin air. No message had come for the Minister of Munitions, nor had anything been seen of either him or Sir Hector. The chauffeur was in the garage with the car, and had heard nothing from his master.

"Mr. Grindly Morrison and Major Han at once sent word to a few gentlemen in the neighbourhood, men whose discretion they could depend upon. They held a meeting in the library of the Morrison place, where Mr. Grindley Morrison told them what had occurred. Then they formed search-parties and searched the whole night. Mr. Grindley Morrison had just returned to the house, and was deciding that he should notify London of the mysterious disappearance, when the secretary of the Munitions Minister got through to him.

"That is the whole story as I have had it from the secretary, and he gave it to me as he got it from Mr. Grindley Morrison. Of course, you can readily see, Blake, what a serious thing this double disappearance is. To-day, the Minister of Munitions was to meet a very important deputation from several of the producing firms of the country. This evening he was due for a Cabinet conference. To-morrow he had another important conference on, and was on Wednesday to speak in Birmingham on munitions.

"In addition to those engagements, there is much urgent matter in his department which will of necessity be hung up during his absence. He is the brains and driving force of that end of things, and without him business will be almost entirely suspended. A message has been sent to the deputation which was to wait on him to-day, telling them that important business has made it impossible for him to keep the engagement, and postponing it until the end of the week.

"The Prime Minister has been told the truth, and he at once sent for me. He has impressed it upon me that we must find him without delay. His disappearance from the scene of action will cause tremendous complications. The other engagements he had, will, as far as possible, be filled by his assistants, but it is he himself who is necessary. That is all I can tell you, and the rest you must find out for yourself. You can work out the problem in your own way, only find the Munitions Minister as quickly as possible—much depends on it. Will you take up the matter, and push it forward without delay?"

"Of course, I will do what I can." responded Blake, rising. "I shall go to work on the matter at once. You are sure there is nothing further I can learn in London about this affair? Do you think the secretary could give me any further facts?"

"I don't think so," replied Sir John. "I questioned him very closely, and what I have told you is everything I elicited from him."

"Very well, I shall go to the scene of the disappearance and start to work there," said Blake.

With that he picked up his hat and stick, and shaking hands with the Secret Service Chief, strode towards the door. He passed through several corridors, and between several police guards, until he reached the lift, and entering it, was taken down to the ground floor. Passing out into Whitehall, he entered the big car, which, with Tinker at the wheel, was waiting for him.

"Drive to Baker Street at once," he ordered, and Tinker, turning slowly, sent the car along Whitehall at a good pace.

Crossing Trafalgar Square, he drove along Regent Street to Oxford Circus and there headed for Portman Square and Baker Street. He drew up in front of the house in Baker Street, and at a word from Blake followed his master into the house. Once in the consulting-room Blake tossed aside his hat and stick, and lit a cigarette.

"Sit down, my lad. I wish to speak to you," he said.

Tinker threw his cap on a table and sat down.

"Something serious—something very serious has happened, Tinker," began Blake. "The Minister of Munitions and Sir Hector Amworth have both disappeared while playing golf on Westward Ho! golf links. As far as is known, these are the details of the affair."

Forthwith he began and repeated to Tinker the story Sir John had told him. When he had finished, he said:

"It would only be a waste of time to theorise now. We must get to the spot without delay and see what we can. I must confess that, so far, the aeroplane spoken of by the caddie is the most suspicious circumstance, but on investigation that may prove to be nothing of importance. But we shall go prepared for all eventualities.

"In this case speed is the chief requirement. Therefore, you will get a taxi and drive through to Hendon. Telephone the mechanics before you go. Tell them to get the Grey Panther out and get her tuned up.

"When you get to Hendon, you will get into the Grey Panther and start for Devon. Come to earth as near to the Westward Ho! golf links as possible. If you take note of the western end of the golf course, you will find a very decent landing-place close to the beach.

"Myself, I shall drive down in the car and meet you there. Don't wait for lunch, but take some sandwiches and a Thermos flask with you. With luck you should arrive at Westward Ho! before me. If you have to come to earth some distance away, get some reliable men to look after the Grey Panther, and come on to the links. That is all. Now lose no time."

Almost before Blake finished speaking, Tinker was making for the telephone, and, ringing up the hangar at Hendon, spoke to the mechanic, telling him to get the Grey Panther ready at once for a flight. Then replacing the receiver he caught up his cap, and with a nod to Blake hurried out.

Blake, on his part, went into his dressing-room, and threw a few things into a bag. Then opening the door he called to Pedro. With the big fellow trotting at his heels, he made for the street and entered the car. A few moments later, he was thundering along Baker Street, heading for the surburbs and the open country, along the road to the west.

He stopped once on the way long enough to send a wire to Mr. Grindley Morrison, warning him of his coming, and then once he had struck the open country, he let out the throttle and sent the car ahead at a terrific pace. Through Middlesex he went across a point of Surrey into Berks, and thence he traversed Wilts, until he crossed the border into Somerset. From Somerset he took the direct road to Taunton, and pausing at Taunton long enough for some hasty refreshments, continued his way into Devon, heading for Barnstaple. At Barnstaple he stopped for five minutes, replenishing his petrol, and seeing to his lights, then on to Northam, only a few miles distant.

At the old sleepy town of Northam, which, in the days of Drake and Hawkins, was, with Appledore and Bideford, a place of bustle and excitement, as the cargoes from Virginia came up the bay and entered the Torridge, Blake paused to ask the way to the Morrison place, then on again to where it lay—a huge black pile of Tudor lines set in the heart of an ancient park, which had gathered vigour from the breath of the sea.

He drew up at the gates, and while waiting for the lodgekeeper to open them, glanced at his watch. It was just on nine o'clock, so that to come from Baker Street to the gates had taken him just under eight hours—not bad, considering the distance was over two hundred miles.

When the gates had been opened he drove up the long, tree-lined driveway which led to the house, and when through the deepening night he was the picturesque house, he noticed that the windows were thrown open to the warm August night, and caught sight of the white gleam of shirt-fronts on the verandah in front. He drew up near the side entrance, and leaping from the car, ran up the steps where a man in dinner-jacket stood waiting to receive him.

He put out his hand as Blake reached the top and said:

"You are Mr. Blake, I presume? Ah! Now that I see your features, I recognise you. I am Grindley Morrison. I received your wire early this afternoon, and have been anxiously awaiting your arrival."

"Then there is still no news?" inquired Blake, as he shook hands and removed his motoring-cap to allow the cool night air to refresh him.

Morrison shook his head.

"Not a sign of them. But come along and have some supper. I will tell you all I can then."

Taking Blake by the arm, he led him into the main hall of the place where a footman relieved him of his dusty coat. Then when he had washed, he followed his host to the room where supper had been spread. At a word from Morrison, the servant who was in attendance retired, and when the door had closed after him Morrison said:

"Go ahead, Mr. Blake. You must be famished. I will talk while you eat."

Blake set himself to investigate the merits of the several dishes which had been prepared, for in truth he was hungry, and while he ate the other talked. He repeated, more or less, the story which Blake had already had from the lips of the Secret Service Chief. When he had reached the point where he had received the 'phone message from London, he paused for a moment to take a sip of port, then proceeded:

"Needless to say, we have searched all day. Several of my neighbours have joined in the search, and though our efforts must have aroused some curiosity, I am certain nothing definite is suspected, for the Munitions Minister was here incog., and no one knew he was to be my guest. I was at Westward Ho! when your telegram was brought to me, and as you requested in it, I kept a sharp look-out for an aeroplane. But during this afternoon none appeared."

"That is rather odd," interrupted Blake. "My assistant was to leave London about two this afternoon, and flying at the speed he would, he should have not take more than four hours for the journey. What time did you leave the links?"

"Not until dusk set in. Some of the party have remained at the links, but when I left, no aeroplane had shown up, and although I left word for a message to be sent on to me in case one did, none has come. If there had been any news I should have heard without delay. I came on here to meet you, but was afraid you would not arrive before ten o'clock at the earliest."

Blake tapped the table thoughtfully

"I cannot understand why Tinker has not arrived. He should have been here. However, he may have had engine trouble on the way, and it may have been necessary for him to come to earth somewhere. If that is the case, he will hardly attempt to finish the journey to-night, but will wait until morning. Now, if you are agreeable, I should like to motor over to Westward Ho! and have a look round."

"Certainly, Mr. Blake. I am entirely at your service. I realise only too well what a serious matter this is, and the fact that both gentlemen were my guests, makes me feel it all the more keenly. But I can't for the life of me imagine what has happened. What could happen to those two in broad daylight on a golf links? I know, of course, that their absence from the helm would complicate matters vastly, and would grant a valuable delay to the enemy, but who would have dared to carry out such a thing? And yet, there must have been foul play."

Blake rose and lighted a cigarette.

"Surmise at present is useless," he said. "When we have had a chance to view what slight evidence there appears to be, and have collected that evidence together, then, and only then, may we attempt to form some theory as to what happened. By the way, where are the two golf-bags?"

"I have them in my study," replied Morrison. "Do you wish to see them?"

"When we return," said Blake. "If you are ready, I think we had better be getting along."

They left the room and passed out to the hall, where a man brought their coats and caps. They made their way outside, where Blake's car still panted at the steps. As they reached the top of the bank which rose from the driveway a man came towards them, and when he had drawn nearer, Blake saw that he was an elderly individual, with the stamp of the retired military man about him. He was therefore not surprised when Morrison introduced him as Major Hart, who had been a member of the golfing party when the mysterious disappearance took place.

He accepted Blake's invitation to join them, and, taking the wheel, Blake turned the car and started down the drive. On reaching the main gates he turned to the left, and with the powerful road-lamps picking out the road which wound like a white ribbon over a mantle of sable, they raced for Westward Ho!

Blake, who had often played on the Westward Ho! links and accounted them among the finest in all Europe, knew the way perfectly, nor did he slacken the pace until the car had passed the hotel and was skirting the links.

Instead of driving on to the club-house he kept on to the beach, from which came the boom, boom, boom of the great pebbles as the receding tide ground them viciously together. Here he drove more slowly until, at a word from Morrison, he drew up and all three descended.

"This is where we started the search," remarked Morrison, when they had alighted. "I suppose you will want to start here, too. We should meet some of the other searchers at any moment."

Blake dug beneath the rear seat of the car and produced a powerful acetylene lamp, which he turned on and lighted. Then he spoke:

"If you will lead the way, Mr. Morrison, I will follow. I do not know that I care to spend much time here. I wish to go chiefly to the spot where the caddie says he saw an aeroplane rise."

Morrison grunted, and, turning, led the way over the sand dunes along the beach until the lights of the village dropped behind, and only the incessant booming of the sea on the pebbles filled the night. To the right shone the light on Bideford Bar, while now and then as they topped a dune they could catch a glimpse of the revolving light on the southern point of Lundy Island, which stands sentinel at the gaping mouth of the channel.

Far up the shore they came upon two men, who were standing close to the water gazing out to sea. They turned as Blake and his two companions appeared, and by the light of the acetylene lamp he carried, Blake could see that they were both rather elderly.

Morrison introduced them as two neighbours, and when they were informed of Blake's name, they gave him an account of the evening's search. They told a tale of woods searched and shore examined foot by foot, without any signs of the two missing men. Blake listened to their report, then, thanking them, requested Morrison to show him the exact spot where the aeroplane had been seen to rise.

Morrison led the way into a near-by wood, and, making a circuitous way to the shore again, paused between two sand dunes.

"It was here," he announced.

Blake, holding the lamp so that the flare would fall on the sand, dropped to his knees and began to make an examination. It was not difficult for him to locate the two lines which Morrison attributed to the wheels of an aeroplane, and at the end of a few minutes Blake was strongly inclined to agree with him.

But to make a detailed investigation of the marks that night was out of the question. Though the acetylene lamp was powerful, still it would not show up the faint marks which might be there and on which Blake might find reason to hang his chief theory.

But now he had located the spot and could gain some idea of its topography in relation to the lie of the shore and the sweep of the channel, he could apply his intelligence with more certainty to the evidence which had been related to him by Sir John and endorsed by Morrison that same evening.

When he had risen to his feet he closed the mask of the lamp, and addressed the four men who stood close at hand.

"Gentlemen," he said, in low tones, "it must be quite evident to all of you that this affair is of a most serious nature. It must further be plain to you that for the present, at least, the truth must not leak out. Mr. Morrison has vouched for your discretion, and when you understand that matters vital to the safety of the nation are involved, you will see why nothing must be said. Therefore, I want you all to pledge your word of honour that until permission is given you you will say nothing about this."

A deep rumble of voices answered Blake as each one of the quartette gave his word. Then Blake resumed.

"With the gentlemen who live in the district, and who have already been taken into Mr. Morrison's confidence, we should have a sufficient force to keep guard here and watch for any development at this end. The line from here shall be in my own care. But for the present, at least, it will be necessary to preserve every atom of evidence until I can make a thorough examination of it. Therefore I want you to volunteer to take turns guarding the spot. Will you volunteer?"

It was Morrison who answered.

"I can speak for all of us here, as well as the others, who are at present about the links somewhere. We are only too keen to do all we can, and you may consider us, one and all, under orders, Mr. Blake." Blake bowed his thanks. "How many of you are there?" he asked. Morrison thought for a moment, then said: "Seven."

"Then I think it would be a good idea to divide the force up into watches. If three watches of two each were formed that would take six, and you, Mr. Morrison, could superintend the matter. In that way we could guarantee that this spot and a certain portion of the links would be under continual surveillance for the next few days, which may be critical. On the other hand, if we are successful in our efforts it may only be necessary for me to ask the services of yourself and your friends for a day."

"I shall certainly arrange to do this, Mr. Blake! We will pick up the others and arrange the first watch." Here Major Hart spoke up.

"If one of you gentlemen," he said, referring to the two whom they had found on the edge of the shore, "will volunteer for the first watch, I will also do duty."

Immediately one of the pair volunteered, and they took up their places by the spot where the aeroplane was supposed to have risen. Then Morrison struck off across the links to acquaint the other three men with the new arrangements, and Blake, well satisfied that the spot would be well guarded until daylight, when he could make a proper examination of any evidence there might be, returned to the car and waited for Morrison to come up. In about ten minutes he appeared, and, climbing in, said:

"I have fixed things up. The others are arranging the watches and will snatch some sleep at the hotel while they are not on duty. I shall return about midnight to see how they are getting along."

Blake nodded, and, starting the car, drove back to Northam. Arriving there he drove to the Morrison garage, where a man took charge of the car, and following his host into the house, went along to the study where the two golf-bags which belonged to the missing men had been taken.

The bag which Sir Hector Amworth had carried presented no particular features of interest. It was a well-made canvas bag, having a hood which protected the clubs. Blake unfastened this hood and examined the clubs one by one, but beyond revealing the ordinary signs of wear, he received no suggestion from them.

Laying this bag aside he picked up the one which had been carried by the Minister of Munitions. It was a very handsome bag of pigskin, well fitted with protecting hood of the same material which fastened by a patent lock, as did the other bag.

In addition, it was provided with all the accessories desired by the inveterate golf player—ball pocket, sponge pocket, umbrella holder, and a multiplicity of leather straps and other fixtures.

On raising the hood Blake saw that it was packed with all sorts of clubs from drivers—of which there were three sorts—to cleeks and putters, the latter represented by two designs.

It was the bag of the enthusiast who knew his game. Taking out the clubs one by one, Blake made a cursory examination of them and laid them aside. At last there was only one left in the bag, a finely-balanced mashie, which he laid beside the others before thrusting his hand into the bag to see what else was there. Then he came upon two broken pieces, one of which Morrison had picked up in the wood and the other on the beach.

Now Blake laid the bag aside, and carrying the broken club closer to the light concentrated his attention first on the shaft. He saw that it had been broken almost exactly midway between the top of the shaft and the tip of the club. It was a brassie, well made and strong, and as he gazed upon the clean break, Blake knew only a heavy blow could have caused it.

He put aside the top part of the shaft and picked up the club end. This he studied for some time, then thrusting his hand in his pocket, drew out a powerful pocket-glass which he applied to the examination.

Along the lower edge of the brassie's face he had seen something which had aroused his curiosity, and now through the glass he made out that the marks which had attracted him were neither the stains made by grass nor yet the remains of mud. They were tiny spots mostly, with one fairly large blotch about the size of a threepenny-bit—dark brown in colour and possessing no lustre.

Blake puzzled over the marks for some little time before suddenly he shot forth his hand and between his fingers carefully grasped something which had been adhering to the lower part of the club. Then as he held his hand up to the light, Morrison, who had been watching closely, saw that he held in his fingers a short hair. Blake laid down the club and placed the hair under the glass.

For some minutes he studied it; then raising his head, he said:

"This is an important discovery, Mr. Morrison. There can be no doubt but that this is a human hair, and unless I am greatly mistaken we shall find when I have made a thorough test that the stain on the lower edge of the face of this brassie is human blood. In my opinion, the club was broken owing to the violence with which a blow was dealt with it."

"Good heavens!" exclaimed Morrison. "Do you think that is the hair and those stains the blood of the Munitions Minister?"

"That is, of course, impossible to say; but hazarding a guess, I should think not. It is more likely to be the trophies of a blow which he dealt his assailants, for that there were assailants seems a certainty now. No, I should much prefer to think that they were the results of a struggle, in which the Munitions Minister had used the first weapon which came to hand and which he was probably holding when the attack came. Though how it came or whence, we cannot guess.

"But to-morrow I shall make certain tests and prove whether or no this is human blood and if this is a human hair, although I am fairly certain on the point already. Whoever wielded this club dealt a fierce blow, and I do not envy the man who received it on his head.

"Now I think that is all we can do to-night, Mr. Morrison, and if you do not mind, I shall retire. I will take this club with me. If anything comes from Westward Ho! please call me at once."

"I will do so," replied Morrison. "I am going out there at midnight to see how things are going on, but unless there is something important to report I shall not wake you."

Blake thanked him, and saying good-night, left the room. He went at once to the room which had been assigned to him, and, carefully laying the broken pieces of the brassie on a table, began to undress. He spent little time in futile theorising, but slipped into bed, and, although worrying a good deal over Tinker's non-appearance, soon drifted into sleep.

It seemed to him that he had scarcely dozed off when he was awakened by a furious pounding on his door, and sitting up in bed with a start, became aware that Morrison was outside the door shouting:

"Wake up Mr. Blake! I have just had a message from the links. There is an aeroplane wheeling round and round overhead, as though looking for a landing-place!"

How Tinker Brought the Grey Panther to Devon.

WHEN Blake had counted on four hours as being good flying time for Tinker to get from Hendon to Westward Ho! he had calculated conservatively. With favourable conditions the journey could be made in a machine like the Grey Panther in something under that time. But neither Blake nor Tinker were able to anticipate the trouble which the lad was to have.

When Tinker left Baker Street he hailed a taxi and drove straight through to Hendon. There at the hangar, which Blake used for the Grey Panther, he found that the mechanics had already wheeled out the slim shape of the monoplane.

She stood just without the hangar, shining beneath the warm afternoon sun, her lines as slim as those of any bird, and her silent Gnome engine sufficient in itself to suggest the lure of the boundless azure above. Sexton Blake had designed well when he designed the Grey Panther.

Tinker spent some twenty minutes examining the struts and stays and in tuning up the engine, then, climbing into the cockpit, he gave the word to the two mechanics, and, as the engine roared out and the propeller spun, they released her and she ran ahead in a straight line, throbbing beneath the reserve power of the engine.

A slight lift of the lifting planes and she rose easily; a pressure on the rudder bar and she swung to the left, picking out a spiral course which would take her to the two thousand foot level in a wide swing having a diameter of several miles.

Then Tinker settled back in his seat in full accord with the perfection of movement, which the Grey Panther at all times achieved.

Up, up, up she climbed, until the blunt nose of the Grey Panther pointed west, then, releasing the slight pressure of his foot on the rudder, Tinker let her forge ahead.

Catching the straight bend of the air, the monoplane quivered like a nervous horse at the start of a race, then the ground below was sweeping away beneath with the dark smudge of buildings growing less and less clear as the green country beyond was reached.

Mile after mile was ticked off with swift regularity. Towns were sighted, passed and left behind in a patch of grey and black. Villages and hamlets swept into view and were lost again. A lone farm here and there, the spire of an ivy-covered church, an occasional motor far below on a narrow country road, a slow moving farm cart, a solitary man in one of the fields which formed part of a widely-spread draught-board—all these and the hundred and one details which the airman sees, passed beneath them as the Grey Panther swept on her way.

Over county after county until he was over Stroud, in Gloucester, went Tinker, then he headed for the wide mouth of the Severn and the Bristol Channel. Away beneath soon glistened and reflected the long line of rocks and sand bars which stretched away to right and left until they broke into the shores of South Wales and North Devon respectively.

As he sighted them, Tinker made a mental calculation. He knew that if he kept straight on down channel, making Lundy Island his point of direction, he would eventually come opposite Westward Ho!—which was his destination. By following a straight line in this fashion he would have the broad line of the channel to guide him, and when opposite Westward Ho! a slight turn to the left would fetch him towards the land.

With this intention, he let the monoplane keep her present direction, and in the ordinary course of events, he would undoubtedly have fetched his landing place. But when the converging upper part of the channel had been left far behind and only the widening sweep of the blue water could be seen, he suddenly sat up in his seat and gazed away to the north, where a dark speck had appeared.

At first it looked like a bird wheeling high up against the blue sky, but as he continued to gaze at it Tinker knew it was no bird, but an aeroplane.

Hastily he swung the chart-stand towards him and gazed at the map of West of England which he had affixed before leaving Hendon. Then, looking to the north, he saw that the other machine was climbing high and heading westward.

"She is from Cardiff way," he muttered; "or, if she is not from Cardiff, she has been flying in that vicinity. I wonder if she is from an air station on the South Wales coast? I'll shift my course a point and see if I can pick her up. Might have a little race down Channel."

Suiting the action to the word, he put his foot on the rudder-bar and gave a slight pressure. The monoplane answered smoothly, and the next moment they were sweeping along on a different course—a course which, while it was still westward, would bring them in gradually until they were closer to the strange machine which Tinker reckoned was now about three thousand feet up. Incidentally, he shifted his lifting-planes a trifle, intending to climb to the level of the other machine.

Slowly the form of the other became more distinct. In another ten minutes Tinker saw that she was a biplane, and then a little later his eyes widened a trifle as he made out the full strength of her lines.

"Thunder!" he muttered. "She is certainly some biplane—a passenger machine, and big at that. I wonder where she is making for? Anyway, the Grey Panther has more speed, and I should be able to overhaul her soon."

During the last few miles Tinker had felt that bane of all airmen—air-sleepiness. On a warm day, with a machine running easily and little wind to strain at the stays, an airman is almost certain to fall under this species of air hypnotism, and in more cases than one it has been the death of those who have yielded to it.

Therefore, the lad more than welcomed the opportunity of a race, for it would rouse all his faculties, keeping him on the alert each moment.

Whether the pilot of the other machine had seen him or not he could not say. In any event he had so far paid no attention to the slim shape of the monoplane which was coming up behind him, and with a superb disdain of the Grey Panther, was forging away westward.

Tinker smiled to himself as he viewed the wide spread of the biplane, then, pressing the accelerator of the monoplane, he sent her leaping ahead. The speed indicator climbed from seventy to eighty miles an hour, from eighty to eighty-five, then to eighty-seven, and, at that Tinker let her hum.

The nearer he drew to the biplane, the more he became impressed with her great size and power, though in a straightaway race she would be no match for the slim and speedy monoplane which Blake had built.

By now the Bristol Channel stretched away on either side until the land was only a dim line north and south, and getting less clear each moment. Then the biplane ahead altered her course a trifle, heading more to the north in a direction which would bring her closer to the Welsh coast.

Tinker gave his rudder-bar a pressure and followed. As the Grey Panther came round he saw that the pilot in the biplane had taken sufficient notice of him to increase his speed, for now the big machine shot ahead at a swifter pace with the monoplane gaining very little.

"At last he has decided to race," chuckled the lad. "It has taken him long enough to make up his mind. Well, we will give him a pretty little run of it until we get opposite Westward Ho! The way he is going now he will drag me across the channel to the Welsh coast, but it won't take long to cross back again."

But Tinker was to find that the big biplane could kick out more speed than he thought, for now she increased her pace again, and for a short time the Grey Panther dropped back. Not until he had sent the speed-indicator up to ninety-five miles an hour did he start to gain again, and then, absorbed in the progress of the race, he did not notice that already he was far down channel.

Not until there suddenly appeared below him a long line of breakers, whose shock was taken by high and jagged cliffs, did he realise that not only had he passed the point which would be opposite Westward Ho! but had got far out towards St. George's Channel.

"Those must be the cliffs of Pembrokeshire," he muttered. "We have certainly come along some. I didn't realise how fast we were eating up space. I guess I had better turn back and call it an unfinished race. Perhaps I'll meet you again Mr. Biplane and give you a better run for your money."

As he pressed his foot against the rudder-bar to make the turning, he leaned over and gazed down at the sea below. He could see the ragged-looking line of coast with a myriad small islets thrown off from it, and in some cases almost hidden by the flying foam as the waves rolled in and broke upon them in a shower of iridescent spray. Between them and the narrow patches of sea which separated from the mainland, Tinker could see the white gleam of low-lying sands and the water glistening on vicious and wicked-looking rocks, bare and gaunt at low tide, but swept by a swirling mass of green and black as the water rose.

Jammed in between them he could, in imagination, see the narrow guts and crevices in which the tossing water sucked and whirled, meaning death to the strongest swimmer were he caught within them. Then, far to the north, away by itself, was one islet larger than those immediately below him. It stuck out, gaunt and bare-looking, from the height at which he viewed it, and for all the world looked like a great solid stone triangle dropped in the sea by one of the mythical giants of old, or a chosen spot on which Neptune or Thetis might rest while viewing the tossing waves which they ruled.

For miles he had scarcely moved the cloche or foot-bar, but now, as he started to turn and while still gazing away at the other machine, his foot suddenly caught in a wire leading to the switch, and in a moment he had pulled the connection loose. The next second the motor stopped, and, after the barest of quivering pauses, the monoplane plunged downwards.

It was fortunate for Tinker in that moment that he was up almost three thousand feet. Had he been only a few hundred feet in the air he would have had extreme difficulty in managing the machine for the drop, but long experience had taught him instinctively what to do, and while getting the Grey Panther into the correct angle for the volplane, he reached down and tried to catch hold of the wire end and replace it on the binding post.

No use!

Try as he would he could not reach it. It waggled aggravatingly just out of reach of his fingers, and straightening up he looked over the side.

"Nothing for it but to let her continue on the volplane and find a place to land," he muttered. "And what a place to have to come down. I haven't the floats on to-day, so can't come down on the water. Nor does there seem to be a square foot of level ground about those cliffs or islets, let alone a flat stretch where I could come to earth with an aeroplane."

At that moment his eyes lit on the triangular-shaped island which lay beyond the small group of islets below him.

With a quick glance he took in the details of the level surface which it presented, and saw that, contrary to what he had thought when at three thousand foot level, there were buildings upon it. Only two houses could he make out to be sure, but that meant people and people meant help in an emergency.

Then his eyes caught the sight of the great biplane dropping earthwards, and to his amazement, he saw that she was volplaning towards the island. Then every atom of his attention was needed for the Grey Panther.

He was about eighteen hundred feet above the sea now, and calculated swiftly that a direct volplane would carry him some distance beyond the island.

Jamming his foot against the rudder bar he changed the course of the machine and sent her into a spiralling volplane which would bring him down on the island. Then, bracing tight, he watched every movement of the Grey Panther, ready for any emergency which might occur.

He was not alarmed at the predicament in which he had managed to get himself. Had there not been a possible landing on the small triangular-shaped island he would have been in a very unenviable position, but the closer he got to earth the better he liked the look of the landing; and, if he could direct the volplane correctly, he would be little worse off. It would take him very few moments to replace the end of the wire on the binding post and then he could get away again.

Now he saw that the biplane, instead of landing on the island, had started her engine again and was rising in a spiral, but he saw at the same moment something white drop from her and float downwards towards the island.

From one of the houses two men ran out, and Tinker had just time to see that they were making for the spot where the white article must fall, when a patch of wood hid them from view, and all his faculties were taken up with making a landing.

The monoplane came down easily, and, striking the ground with her skids ran ahead and stopped with scarcely a jar.

After the barest look round at his surroundings, which he saw to hold little attraction, Tinker bent down, and, catching the end of the wire, fixed it to the binding post.

Then he screwed up the nut which held in its place, and, straightening up, prepared to get out. He knew just beyond the wood by which he had come down he would find the houses; and it was his intention to seek aid of the two men he had seen run out from one of the buildings.

But scarcely had his foot touched the ground when from somewhere in the wood there came the sound of a rifle, and the next thing a bullet plunked through one wing of the monoplane, just whizzing past Tinker's head.

Tinker whirled quickly and gave a loud "Hallo!"

"Look out there!" he yelled.

For answer the rifle barked out again; and this time a bullet passed through the arm of his coat to strike the Gnome, and ricochet from it to the ground by the lad's feet.

"This is a little too hot for comfort," he muttered, gazing in amazement at the spot from which the shots had come. "Those shots could hardly have come as close to me by mere accident. Hallo!" This as another shot struck the tail of the machine.

With that Tinker leaped into the cockpit, and, bending towards the rear starter, gave it a turn.

Just as the engine roared out, two men burst from the cover of the wood and started to run towards him. One of them stopped after a few yards; and, raising a rifle to his shoulder, fired. The bullet whistled over Tinker's head, and, ducking, he bent low while the Grey Panther tore along the stretch of level ground.

The men who, where they stood, were on his left ran on a little further, then both of them stopped and began firing at him. The bullets tore through the thin wing material of the monoplane and went ripping past the lad's head but no real hit was registered, and a few moments later, when the monoplane had gathered sufficient headway for a rise, Tinker shifted the lifting planes and sent her up.

But not yet did the fusillade of lead stop. All the time he was climbing to the thousand foot level they followed him, nor did they desist until the spiralling course he was following had taken him well out of range.

Then, as he pressed the rudder bar and sent the Grey Panther round to head towards the Bristol Channel, he saw, less than a mile distant, the huge biplane which, in the first instance, had been the cause of his getting so far away from his intended destination.

Tinker reckoned she was about on the two thousand foot level, and as he gazed at her he was puzzled by her movements. She was wheeling round and round in narrow circles, banking at dangerously steep angles as she turned and, seemingly, flying aimlessly.

Putting two and two together, however, it was not difficult for him to guess what was her purpose. He remembered how she had volplaned down towards the island while he himself was dropping. He recalled, too, the white article which had dropped earthwards from her, and which the two men had run from the house to get. Then he called to mind how a vicious and murderous attack upon himself had immediately followed.

Now the biplane was wheeling about watching for him. He was certain of it. Yet it puzzled him, even as he pressed the accelerator, to figure out why this should be so. When he had first sighted the big biplane back Cardiff way he had changed his course a point with the intention of having a friendly race down channel.

Although he did not recognise the machine, he reckoned she was one of the new craft of the extended air service, and, knowing the type of aviator in the ordinary British machine, he did not anticipate for a moment that his challenge would be refused.

Following that, the biplane had increased her speed and they had raced westwards. Then, when the accident had occurred to the Grey Panther, Tinker had found himself over a rocky portion of the Pembrokeshire coast. And yet, in thinking over the race, he recollected that the biplane had always been ahead, thus setting the pace and thus choosing the direction.

It was because he had followed her that he had reached such a lonely spot as he had. But that did not explain the reason for the white article which had been dropped from the biplane to the island, and which, in Tinker's opinion, had caused an unwarranted attack to be made upon him.

Only his own rapidity of action had saved him from being drilled by several bullets. Why? That was the puzzle. Nor was he left long in doubt as to the intentions of the other machine.

As the Grey Panther turned her nose towards the east, Tinker saw the biplane swing after him and drop to the two thousand foot level on which the monoplane was now running.