RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

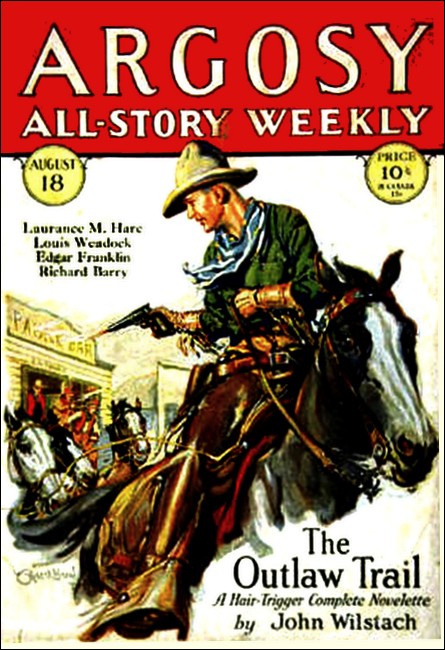

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 18 Aug 1928,

with "Treasure Accursed—and Mescal"

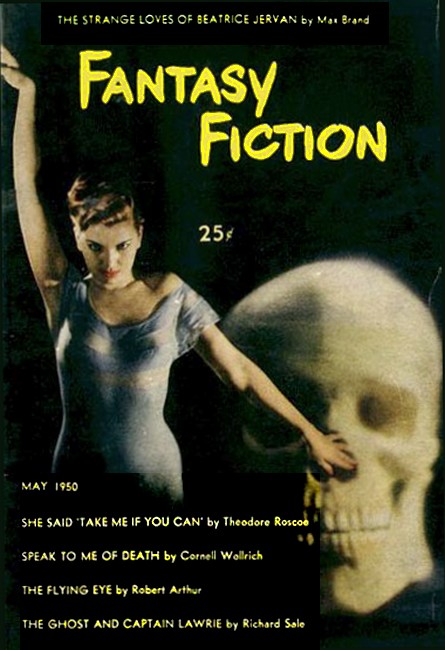

Fantasy Fiction, May 1950, with "Treasure Accursed !"

AS usual, my best customer in San Antonio waited until fifteen minutes before train time, then affixed his name to the dotted line. As he had done a dozen times before, he apologized for keeping me so long, expressed the hope that I would not miss my train.

I reached the depot in time to buy a railroad ticket, but the Pullman frames for the Cotton Boll Flyer had already been taken aboard. The redcap deposited my luggage in the observation car, pocketed his tip, and rushed for the door as the train started.

At this late hour I fully counted on occupying a "shelf," and was therefore agreeably surprised when the Pullman conductor informed me that I might have lower twelve in the Golconda.

I made out my reports, figured my commissions, and wrapped myself around a table d'hôte dinner, then settled down in my compartment to read a novel I had purchased that day.

When I get interested in a story I ant deaf to all that passes about me, so time and the Cotton Boll Flyer sped unheeded until I was aroused by the voice of the porter.

"Yas, suh. Make up yo' berth, suh?"

Reluctantly I arose and carried my book to the tiny smoking compartment. The solitary occupant greeted me with a nod and a "Howdy," as I entered. Evidently he wanted to start a conversation. I returned his greeting and sat down to resume my story, hoping that he would go to bed, or at least keep silent. He did—keep silent, I mean—for about three minutes. Then he opened up.

"Must be a mighty interestin' book you're readin'."

"Yes. It's a good story."

"Story books is all right, but stranger things than ever was written sometimes happen in real life."

Apparently I was in for it. This man had a story to get off his chest, and I felt that I might as well listen to it and have it over with. There was nothing about the man himself that might arouse interest. He was of medium build, gray-haired and plainly attired, evidently a small-town merchant of the Southwest.

"I have heard that truth is sometimes stranger than fiction," I replied, hoping he would be brief.

"You're shoutin'!" he exclaimed. "You're good and well shoutin', and nobody knows it better than I do. I come down here from Wardmore to rest my shattered nerves—doctor said I should get out in the open for a few weeks.

"I was in the open one day and one night, and if my nerves was shattered before they're teetotally wrecked now. Open, hell! No more open for me."

He produced a flask of colorless liquid from his hip pocket and proffered a drink, which I declined with thanks'

"This ain't no moonshine stuff," he explained. "Genuine mescal from over the border. Needn't be afraid of it."

"No, thanks, I never indulge."

"Well, I just gotta take a bracer now and then. Can't eat, can't sleep, can't do nothin' for thinkin' about last Monday night."

He took a deep draft, made a wry face, shuddered, and replaced the flask in his pocket.

"You must have had a harrowing experience," I ventured.

"Harrowin'? You said it. How old would you take me to be?”

"I should say about fifty-five."

"I'm just turned forty. Last Monday my hair was as black as yours. It turned gray overnight, and all because I followed the doctor's instructions, acceptin' an invitation from my friend, Dave Bonner, to go for a deer hunt on his ranch.

"Well, the day before I got there Dave tried to ride a no-good bronc, and the result was one busted collar bone, to say nothin' of sundry and assorted bruises, scratches and cuts.

"Dave was laid up, but he insisted that I go on the hunt anyhow, with one of his men named Joe Stark; so we rides out from the ranch bright and early Monday mornin' with Joe's hound rangin' ahead and a loaded pack horse trailin' behind.

"A thirty-five-mile ride took us well into the deer country, an' Joe picked on a shaded hollow as an ideal spot for the camp. It was a sort of gulch, runnin' plumb down to the river bed.

"I say river bed because there was about seventy-five feet of sand bottom stretched between the banks, with ten or fifteen feet of river zigzaggin' down the center of it. Of course when there's rains it's different, but it's been pretty dry down in this country lately.

"Well, anyhow, we pitched camp there, figgerin' to mosey over to a salt lick Joe knew about early the followin' mornin' and do a little still huntin’. After supper, Joe suggests that we while away the evenin' with a bottle of mescal and a little game of draw.

"About ten thirty the bottle is empty and Joe has most of my loose change, so I propose that we turn in. We're headin' for the tent when—zip! Joe's old hound which has been rangin' around among the trees, shoots between us with his back bristlin' an' his tail between his legs, an' ducks through the flap.

"Joe was some surprised. Said he never seen the dog act thataway before. Said he'd hunted everything from jack rabbits to mountain lions and never see him show a streak of yellow.

"We tried to coax him out of the tent, but nothin' doin'. He just crouches down in the corner and shivers, so Joe picks up his rifle and walks off in the direction he come from, to find out what it was that scared the daylights out of him.

"He comes back a few minutes later an' says that whatever it was, it must have sneaked off in the dark.

"No sooner does he get the words out of his mouth than we hear the horses snortin', squealin', and stampedin'. Before we can get to them they're gone, picket pins, ropes, an' all.

"I opine that if they go back to the ranch we're in a hell of a fix, but Joe calc'lates they won't go far with their ropes draggin'.

"We go back to the tent and I step inside while Joe stirs up the fire. I hear him talkin' to some one outside, so I step out figgerin' we got company.

"When I come up behind him he jumps kinda quick and swings his gun on me, then looks sheepish and asks how in blazes I got behind him so quick when I was standin' across the fire from him just a second before.

"When I tell him I was in the tent while he was talkin' across the fire he's some mystified hombre. I'd've concluded he was tryin' to kid me if he hadn't been so serious about it.

"I sit down by the fire and try to cipher the thing out, and turn to Joe with the opinion that maybe he's had just a drop too much of mescal, when he sticks his head out of the tent and wants to know who in Halifax I'm talkin' to.

"For a minute I think I'm seem' double, for there is Joe standin' in the tent, and here is Joe beside me. Then I only see him comin' out of the tent. After considerable discussion we agree that the mescal must be causin' double-sightednesss, an' turn in.

"I get about five minutes' sleep. Then I wake up sudden and hear Joe say: 'What's that?' There's a peculiar sound on the outside of the tent, as if some one was scratchin' it with a curry comb, or maybe rippin' it with a knife.

"The hound is so scared he is afraid to growl, although he rumbles a little bit, deep down in his throat. We grab our guns and rush outside, but find nothing and the noise stops.

"Then we go inside and it starts up again, so I stay inside and Joe goes out, and the noise stops once more. We decide the only thing to do is to stand two-hour shifts, Joe takin' the first shift while I turn in, too nervous to sleep.

"After about a half hour I'm just dozin' off when I hear a stifled groan from Joe. I rush outside and find him wrasslin' around as if somebody had a hold of him around the waist. Funny part of it is that I can't see the party that's got hold of him."

Here the narrator stopped for a long pull at the pocket flask, while I tensely awaited his next words. My book was completely forgotten.

"Well, Joe breaks loose from whatever has hold of him, but I can tell he's just about all in. I can see him shiverin' from where I stand, and his eyes rollin' somethin' awful. Truth of the matter is, I was doin' plenty of shakin' on my own account.

"I tried to brace up and tell Joe we was just plain piped, and havin' delirious tremblin', and kinda had him thinkin' my way when the dog gave a howl and rushed out of the tent. He passed use hell-bent-for-Sunday, and ain't never been seen since so far as I know, but I'm tellin' you that hound was plumb loco.

"Joe seen the way he was bristlin' and frothin' at the mouth, and, of course, that queered my theory about bein' bewildered by cactus juice, for, as Joe remarked, the dog didn't drink no mescal.

"WELL, of course, this occurrence didn't buck up my courage none, and I was for leavin' the place flat, but Joe was one of them hombres that has a streak of bulldog courage in him. You know the kind that never know when they're licked. That's Joe.

"Then we hear the scrapin' sounds inside the tent. We go in, and the sound continues outside. We step out, and the sound goes on inside.

"Once more I opine that we better vacate the premises while vacatin' is humanly possible, but Joe is plumb obstinate. He says he's goin' to stick around if it's only to see what the hell will happen next.

"'Let the son of a sand-dab scratch if it wants to,' he says. ‘It ain't hurtin' us none.'

"Then he piles some wood on the fire and lights his pipe casual like. Not wishin' to be outdone I loads up my donicker likewise, and we squat down by the fire while the scratchin' goes merrily on.

"Did ja ever get used to sleepin' with a clock tickin' by your bed and have it wake you up when it stopped? I was just gettin' sort of used to this scrapin' sound the same way and startin' to doze off when it stopped. I was wide awake as a flash and so was Joe, for I seen him give a sort of start on the other side of the fire.

"What got me, though, was the looks of the fire itself. There was plenty of wood on it, but it seemed to be slowly dyin' down—like somethin' was suckin' the flames into the ground. I stirred it up and Joe put on more wood, but nothin' would start it up.

"Down, down, lower and lower it went, from flames to embers, from embers to ashes. It got so dark I could barely see Joe sittin' across from me.

"Then those invisible arms grabbed me and I had a fight on my hands. I could hear Joe gruntin' and threshin' around on the ground, but I couldn't see him and was too busy myself to help him.

"What happened after that seems like a nightmare. I dimly remember breakin' loose and tryin' to find Joe, but failin' in this and pullin' my freight pronto.

"I never was what you would call an A-number-one sprinter, but take it from me, partner, I cut the breeze some that night—cut it clean and handsome until my wind give out. Then I went down in a heap.

"Next thing I knew after that I was layin' sprawled up against a cactus with the sun shinin' in my eyes. Not derivin' any great amount of comfort either from the sun or cactus, I got up and looked around with about as much idea of where I was as a Piute wanderin' in the Catacombs.

"Only thing for me to do was to follow my own trail, which I did, marvelin' meanwhile at the big stretch of territory between steps. If I could broad-jump like that regular I could make one of these here Olympian athletes look like a one-legged sand-flea competin' with a kangaroo.

"Well, I moseyed along, inhalin' alkali dust and hopin' it wasn't more'n a hundred miles to water, when I sights our horses with ropes trailin'. Them cayuses was glad to see me, too, but I was a danged sight gladder to see them.

"When I got into camp I seen Joe squattin' unconcerned by the fire cookin' breakfast. When he seen me he give one startled whoop and dropped a panful of bacon into the fire.

"'Well,' I asks, 'do I look anyways peculiar this mornin', or have you still got mescalitis?"

"'Lordamighty!' he shouts, 'your hair—look at your hair.'

"He passes me the camp mirror and I seen it like you see it now, changed from black to white overnight. I'm some surprised myself, but there ain't nothin' to do about it, and I figger I'm in for a kiddin' bee up at the ranch, so I try to take it casual.

"'That's what comes of ridin' in the sunshine without a hat,' I says. 'Plum faded all the color out of it’.

"He mumbles somethin' about not knowin' that I was addicted to hairdyes, and asks me to rustle some firewood while he slices more bacon. I'm pullin' an old, dried limb from under some piled up leaves and sand when I see something that sends the cold shivers up and down my spine. A whitened human skull is grinnin' up at me from under the limb.

"I calls Joe and we scratch around some more, uncoverin' a whole skeleton and likewise a small metal box. The lid is fastened with an iron padlock that's so rusted it crumbles when Joe taps it with the butt of his six-shooter."

The story-teller paused for another nip from the bottle.

"You can shoot me for a coyote if that box wasn't full of gold nuggets with a slip of yellow paper restin' on the top. There was some writin' on the paper which was almost plumb faded away, but we managed to figger it out. It said:

"'With my dying breath I curse the man who removes this box or its contents from this spot. Thomas Quinn.'

"I was for puttin' the box back and leavin' the neighborhood pronto, but Joe gives me the laugh. Don't believe in no dead men's curses or bunk like that. Says we'll go back to the ranch after breakfast and split fifty-fifty, which I finally agrees to do.

"We was ridin' ranchward a half hour later, followin' the river bank, along which is some pretty high bluffs. Joe was all excited, plannin' what he'd buy with his half of the treasure, when all of a sudden his horse went loco and dashed straight for the edge of the bluff.

"Joe tried to stop him, but it wasn't no earthly use' Might as well have tried to stop a rampagin' long-horn with a cobweb. It was a good hundred and fifty foot drop, and when I heard the thud at the bottom I knew that horse and rider was both in the happy huntin' ground.

"When I got down to the river-bed I found Joe layin' there stone dead, half under the carcass of the horse. The treasure box was layin' a few feet away with nuggets scattered on the sand.

"Did I pick it up? Say, partner, you couldn't have hired me to touch that box or one of them nuggets for all the gold in the United States Mint.

"Well, there wasn't nothin' to do but go to the ranch and bring the boys, which I did. When we got hack we found Joe and the horse layin' there, but the box and nuggets was gone.

"We saw the square mark where it had hit the sand, and beside it the track of big hob-nailed boots—the kind prospectors wear. There wasn't no tracks leadin' up to it, only a trail startin' where the box had lit and endin' in the water."

AT this moment the porter appeared in the doorway.

"Yo' berth is ready any time now, suh," he said.

He walked over to my companion, who, I was surprised to observe, had fallen asleep, and shook him.

"Come along now, Mistah Reed. Yo' don't want to sleep in the smokah. Come on an' I'll help yo' into yo' berth."

After the erstwhile story teller had departed, muttering a sleepy "Good-night," the Pullman conductor came in.

"Hear the treasure story to-night?" he inquired, grinning.

"You must have been listening in," I replied.

"Listening in? Hardly. I've heard it too often for that. Had this run now for fifteen years, and Old Man Reed has told that story to some one on the train every Saturday night since I've been on. Most of the drummers that come down this way regularly know it by heart.

"Old man's a good sort. Lives up in Wardmore and buys cotton down this way for a firm in Dallas. Comes down every Monday morning and goes back Saturday night.

"He's as straight as a string, and tends strictly to business all week, but as sure as Saturday rolls around he gets illuminated for the homeward trip, and the story has to come out.

"Sometimes when he can't scare up an audience, I accommodate him by listening. I don't believe he could make the trip without telling it to some one. Thought I would have to get on the job to-night, but you happened in just at the right time."

Oh well. I've always heard that a first-class salesman is bound to be a good listener.