RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

NOT so long ago it was a common thing to hear lengthy discussions about glands—all kinds of glands—anywhere at all. But though the subject of ductless glands has gone beyond the "fad" stage, gland experts continue their serious and intensive experiments. Much has recently been established as fact in the field of possibilities, but the science of glands is still in its infancy. It is hard to say what strides it will make in the near future. Our well-known author needs no introduction to our readers. Obviously, though, he has made a study of the subject of glands, and he gives us his findings in a most absorbing bit of scientific fiction. We know this tale will gain Mr. Kline many new readers.—Ed.

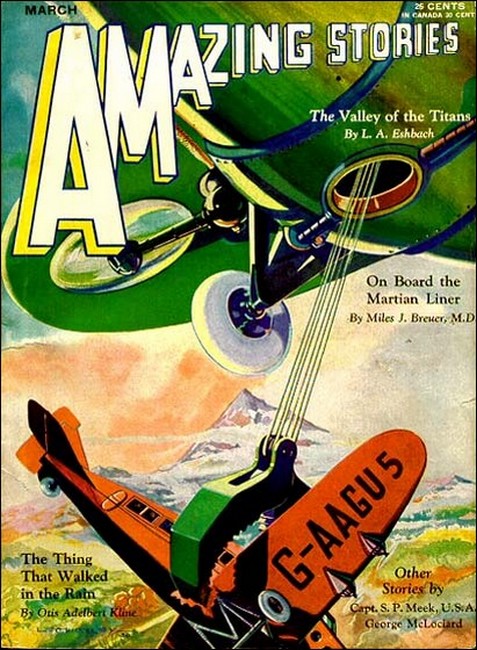

Amazing Stories, March 1931, with

"The Thing That Walked in the Rain"

IT all comes back to me as I take up my pen—a horrid shriek of pain and terror from high in the air, an enormous thing, taller than a tree, silhouetted against a background of lightning-illuminated storm clouds, like some gigantic tumble-weed, striding over the jungle, walking on its branches. And weaving high above the tree tops in the grip of those branches, a limp and helpless human being.

Again I feel a great, green snaky think strike me—knock me down, A band of stinging, burning agony, encircles my body. I hammer it ineffectually with my empty gun.

Once more I see Anita, hopeless terror in her eyes, a green arm around her slender waist, dragged away with incredible swiftness.

But I must begin at the beginning.

CERRO VERDINEGRO is only one of the lesser volcanic peaks that clutter tip the Nicaraguan landscape in such generous numbers. But to the members of our party, trudging doggedly toward it through the dense tropical jungle, it had an importance out of all proportion to its diminutive size.

Pedro Ortiz, our guide, a swarthy mestizo with a thin, carefully trained black moustache, an admirable tenor voice and a penchant for flamboyant raiment, usually avoided speaking its name, when he had occasion to refer to our destination, but merely mentioned it as "that mountain," or "that place." When its name was spoken in his presence he invariably crossed himself piously with a fervent: "Maria Madre preserve us!"

The two Misskito Indians whose keen machetes were carving the way for us, and the eighteen others who trudged behind in single, file, bearing our supplies, had grown more fearful day by day as we drew nearer our destination, so we were kept in constant trepidation lest they bolt and leave us stranded.

Tall, gaunt, bespectacled and bewhiskered, Professor Charles Mabrey, explorer and naturalist, had undertaken the leadership of the expedition for the purpose of clearing up the mystery surrounding the strange disappearance of his friend and colleague, Dr. Fernando de Orellana. And he made it plain that he did not, for one moment, countenance the weird, incredible story which linked that disappearance with the traditional mystery of the extinct volcano. It was his frank and unalterable opinion that the doctor had been murdered by the natives, and that they had invented the outré story of a man-eating monster inhabiting the crater lake purely to shield themselves from punishment. Although I had called his attention to the fact that as soon as the doctor had disappeared the natives had sent a runner to Managua to announce the fact, and that it did not seem likely they would do such a thing, if they had killed him, his only retort was that it was obvious I was not conversant with the complex ramifications of native cunning.

But to one member of our party, Verdingegro was a mountain of tragedy—a tomb, perhaps, that concealed the remains of a beloved parent. Anita de Orellana, motherless for many years, and now a full orphan if the native report of her father's death were true, bravely bore the rigors and hardships of our expedition despite the fact that she had been gently raised—had, in fact, been called from a young ladies' school in New York by the news of her father's strange disappearance. She appeared so small, so slight, so fragile, that often on the trail I felt like picking up the slender, khaki-clad form, as one might pick up and carry a tired child. In her big brown eyes, which she endeavored to keep cheerful, I frequently detected the hint of tears which she bravely hut vainly tried to suppress.

As for me, Jimmie Brown, the least important member of the party, I had joined the expedition at the invitation of Professor Mabrey, my friend and companion of many a jaunt into strange places and dangerous situations. I may as well confess that my hobby is exploration, and my means of livelihood a portable typewriter and a camera. There is a strain of the Celt in me, which perhaps accounts for my penchant for adventure, as well as for my red hair, blue eyes, and scant sprinkling of freckles. To me, the peak of Verdinegro was, at first, merely another adventure. But after I came to know Anila, it was something more. A mystery that must be solved. Perhaps a death to be avenged. The professor had introduced us at the dock and we had become acquainted on the voyage to Nicaragua.

As we suddenly emerged from the humid jungle into the clearing where the native huts were clustered, Cerro Verdinegro loomed up, sinister, menacing gigantic in its nearness. Our last view of the mountain, previous to our plunge into the jungle, had been from a distance of more than ten miles, from which it appeared in a blue haze. On close observation the reason for its name was manifest, for the vegetation that covered its sloping sides was a darker green than that of the surrounding country—probably, the professor told us, because its soil was more fertile.

On entering the village we were greeted by barking dogs, pot-bellied brown-skinned children, slouching, greasy looking squaws in various states of undress, and their no more attractive appearing lords and masters.

Pedro addressed a few words to a white-haired and exceedingly wrinkled old fellow, who pointed toward a path which led up the mountainside, and beside which a little stream trickled. Leaving the natives still gaping and chattering, we filed away between the small gardens of squash and beans, and on up the slope, following a path which cut through the riotous tangle of dark green vegetation.

After about a half hour of climbing, we came to a small clearing, in the center of which was a cottage with a screened porch. Near the cottage was the source of the little stream we had been following—a clear spring that gushed from the mountain side. Opposite this, was a native hut. A neglected, weed-choked garden mutely attested the recent cessation of human care. The dark green rim of the crater loomed not more than a quarter of a mile above us.

Dropping their burdens, our carriers grouped themselves around Pedro and began chattering vociferously. The professor led the way into the cottage. Anita and I followed.

Although the doors were unlocked, it was apparent that nothing had been disturbed. The professor pooh-poohed the idea of native honesty, but believed this singular phenomenon might be due to superstitious fear.

WE found ourselves in a large and roughly but comfortably furnished room, the walls of which were lined with books. A homemade desk, table and filing cabinet occupied one corner. Three doors other than that which led from the porch were cut into the walls. One led to a small bedroom in which there was a cot surrounded by mosquito netting. Another led to a larger room, evidently the doctor's laboratory, the shelves of which were filled with bottles, jars and boxes. It was equipped with a number of small tanks, a large table on which were a compound microscope, numerous retorts and test tubes, and other paraphernalia of the biologist, bacteriologist and biochemist.

The third door led into a small kitchen, equipped with an oil stove, a small sink, table and chairs. It contained a considerable quantity of tinned supplies, neatly arranged on the shelves. The table had been set for one, and the dishes held the dried remains of a meal which apparently had not been touched.

"It is evident, Anita," said the professor, gently, "that whatever took your father away did so quite unexpectedly. There are no signs of violence, so a ruse of some sort must have been used, tie was about to sit down to this meal, no doubt, when called outside on some pretext. But he never returned to finish the meal."

The girl's eyes filled with tears.

"Poor, dear Dad," she said. "He was always so good to me, and I need him so."

"There, there, my dear. I know just how you feel." The professor spoke soothingly, and put his arm around her shoulders. In a moment she was sobbing in the hollow of his khaki-clad arm.

I felt a queer lump rising in my throat. It was the first time I had heard her cry.

At this moment, Pedro came in.

"Pardon, señor," he said to the professor, "but those damn' Misskitos raise too mooch hal outside."

"What's wrong, Pedro?" asked the professor, patting the girl's head consolingly.

"They say mus' go long way by dark. They would like to 'ave the pay, now."

"Go a long way? Why?"

"They 'fraid thees mountain." Here Pedro rolled his eyes and crossed himself.

"To be sure. I had forgotten." The professor released Anita, who had stilled her sobbing and was gazing at Pedro, tears trembling on her long, curved lashes. "Tell them I'll come out and pay them right away." Pedro returned the questioning look of Anita with an expression of dog-like devotion. Fearful as he was of the mysterious mountain, I believe it was this devotion to Anita, more than the money we paid him, that kept him from leaving us.

He bowed politely to Mabrey:

"Si, señor. I tal them."

We followed him outside a moment later, and the professor opened a pocket of his money belt. One by one, he handed each Indian his wages. When he had paid the last man, he addressed Pedro.

"Ask them," he said, "if there are any brave men among them."

Our guide spoke to the group collectively, and a vociferous chattering began, which lasted for some time. Presently it quieted down, and Pedro said:

"They say, señor, that they are all brave men. But they say, also, that they cannot fight a monster taller than a tree, weeth a thousan' legs, and eet foolish to try.

"Tell them that we are going to try, and ask if there are two of them willing to stay if their daily wages are doubled."

More chattering, and presently two men wearing the air of martyrs stepped out of the ranks, while the others filed away, traveling with far greater speed than they had ever attained during our journey.

"Quarter them in the hut," ordered the professor.

"And now," he said, turning lo Anita and me, "we'll get settled, and then down to business."

THAT afternoon, when our luggage had been stowed away and we had partaken of a very satisfactory meal prepared by Anita in her father's kitchen, the three of us, Anita, Mabrey and I, started to follow the well-worn path which led over the crater rim. Pedro and the two Misskitos, squatting around their cook-fire before the hut, watched us depart with ominous glances, much as if we were being led before a firing squad.

When we reached the rim, we looked down upon a lake of glassy smoothness, which faithfully mirrored the sky and the encircling crater. So peaceful and beautiful did it appear, that the idea of a man-destroying monster inhabiting its pellucid depths seemed ridiculous.

"This lake, according to an old tradition," said the professor, "is bottomless, and inhabited by a terrible monster, which emerges from the water on rainy nights, searches until it has found a human victim, and returns to its watery lair deep in the bowels of the earth. Natives who profess to have seen this awful creature say it is taller and bigger than a tree and has a thousand snaky heads. Many years ago, the story goes, beautiful maidens with stones tied to their feet were thrown into the lake at regular intervals decided by the priests. These sacrifices, it is said, prevented the monster from leaving its lair and raiding the villages.

"With the advent of Christianity, the priests of the new religion abolished the custom, and it is said that for many years the monster again committed its terrible depredations. Then, so the story goes, it slept for three hundred years. But of late, it is said, the monster has awakened, and recommenced its raids on the populace. And now, when any man, woman or child disappears during a rainstorm, the monster is blamed and the new priests are cursed. There are, of course, boas, anacondas, jaguars and pumas in these jungles, but their depredations are never taken into account. I am inclined to think that the entire myth may have been started by the raids of an enormous boa, which is a water-loving snake, and often reaches a size that renders it fully capable of crushing and devouring a human being.

"So much for the legend. Now for the facts."

We descended the path which led down to the margin of the lake. It wound through a thick growth of trees and shrubs, the size of which attested their great age and the tremendous length of time which had elapsed since the volcano had last erupted. At the rim of the lake, the path turned to the right, following the water's edge.

The professor, who was in the lead, suddenly uttered an exclamation of surprise and increased his pace. Hurrying after him, I too gasped in amazement at what I saw. For there in that setting of jungle growth was a weather-worn stone structure so skillfully wrought that it might have been the product of an advanced civilization. Rising to a height of about twenty-five feet above the surface of the lake, and with half of its base jutting out into the water, was a stone structure which supported on its top, a huge rock slab, one end of which projected out over the lake like a diving board. A flight of steps led up to the top from the rear.

Just behind this, sunk into the stone paving in the shape of a crescent moon was a stone reservoir filled with water. Each point of the crescent brought up almost at the margin of the lake, where a slab of pumice permitted the lake water to filter through, thus keeping it perpetually filled. Back of this reservoir rose, tier upon tier of semicircular steps, to a height of about fifty feet, like the seats of an amphitheatre. A stone bridge spanned the center of the crescent, and at the top and center of the amphitheatre a great, elaborately carved slab of rock was set into the mountainside. Surrounded by hieroglyphics, the main figure on this slab was a huge multi-headed serpent. The sides of the altar were also decorated with this figure in bold relief, surrounded by pictographs and hieroglyphics,

"Without a doubt," said the professor, "this is the place of sacrifice mentioned in the legends. And that figure, the many-headed serpent, is no doubt an idealized conception of the monster—probably a huge anaconda—to which the victims were fed."

We circled the reservoir, crossed the little bridge, and mounted to the top of the altar. Walking out on the stone slab, I looked straight down into the clear depths below. The reason for the Indian belief that the lake was bottomless was instantly apparent, for although I could see downward for a great distance—could even detect fish swimming far below—I could not see the bottom.

We descended the steps once more, and the professor, with notebook and pencil began jotting down the writing on the side of the altar, for future comparison with the various Central American codices he had brought with him.

Anita, in the meantime, bent over and examined the water in the reservoir.

"What a pretty green water plant," she said. Then she reached beneath the water, but withdrew her hand with a jerk and a little exclamation of fear. "Why. it moved! It's crawling away!"

The professor and I both reached her side at the same time, A small, green, bushy-looking thing about an inch in diameter was creeping toward the center of the pool, using its branches as legs. The bottom of the pool was dotted with many others, growing with their branches extended upward like shrubs.

"What is it?" I asked.

"A hydropolyp," said the professor, "but of a kind I have never seen or heard of before. Although there are many varieties of salt water hydropolyps only three fresh water varieties are known in the Americas, the hydra, the cordylophora and the microhydra. There is a green variety called hydra viridiae, but it is purely a salt water animal. This is interesting! We must take a specimen back to the doctor's laboratory for examination."

He reached into the water and grasped one of the bush-like forms, but instantly let go and jerked his hand up out of the water, while the creature turned over and crawled away.

"My word!" he said. "My word! I'd forgotten that some of these creatures have nematocysts—stinging nettle cells! Anyway, we'll have to bring a specimen jar with us. The things would shrivel up if exposed to the air for a short time."

So engrossed had we been in our amazing discoveries that we had failed to notice the approach of a very black rain cloud. My first intimation of its presence was the splash of a huge raindrop on my shoulder. This was followed by a swift patter, and then a veritable deluge.

"Come," said the professor, "we must get back to the cottage. This may last for hours."

I was about to turn away with the others when I noticed through the sheets of rain, a disturbance in the water just in front of the stone diving platform that evidently was not caused by the torrential downpour. Then I distinctly saw a green serpentine thing reach up out of the water. It was followed by several more, groping and lashing about blindly, like earthworms, exploring the ground around their lairs.

"Look!" I cried excitedly.

THE professor looked with a gasping: "Good God!" and Anita with a scream of fear. One of the lashing arms reached toward us, and we scrambled, slipping and stumbling, up the winding path with a speed of which I had not thought any of us capable.

The rain pelted us unmercifully until we reached the cottage, but with the usual perversity of rainstorms, ceased almost as soon as we had attained shelter.

"What was it?" I asked, as we stood there, making little pools on the floor of the screened porch.

Mabrey mopped his wet face with his handkerchief. "God only knows!" he replied. "I'm willing to concede, however, that it wasn't an anaconda. Let's get into some dry things."

Anita retired to her father's bedroom to change, while the professor and I went into the kitchen to discard our wringing wet garments, rub down, and put on dry ones.

When we emerged into the living room once more we found Anita seated at her father's desk. She had rumpled her dark-brown shingle-bobbed hair to dry it, and I thought she looked more beautiful than ever.

"I've found something interesting," she announced, "perhaps a key to the mystery. It's father's diary."

"A diary," said the professor, "is a personal and sacred thing."

"But it says: 'For my daughter, Anita, when I am gone,'" replied the girl, "and instructs me to communicate the contents to you, Uncle Charley."

"That's different," said the professor, settling himself comfortably and loading his pipe. "Suppose you read it to me."

"I'll go out on the porch," I said.

"No, stay, Jimmie," begged Anita. "There's nothing secret about it. After all, even if there were, you are in this adventure with us—one of us. Sit down and smoke your pipe. I'll read it to both of you.

"The first part," continued Anita, "tells Dad's reason for coming here—to investigate the persistent legend of a terrible monster living in the crater lake. We all know that. He soon found the place of sacrifice and brought away some of the hydropolyps for examination in a temporary laboratory he had set up in a hut, while native workmen, under his direction, were building this house for him. Then he—"

She was interrupted by the slam of the screen door and the sound of footsteps on the porch. Pedro stood, bowing in the doorway.

"Pardon señorita y señores," he said, "but three Indios come in strange dress. Almost they are 'ere. I await instructions."

"Find out who they are and what they want," said Mabrey.

Pedro bowed and departed, and we all went to the window to watch him meet the newcomers. Our two Misskitos, we noticed, arose at their approach and bowed very low. The strangers were attired in garments unlike anything worn today, except perhaps on feast days or at masquerades or pageants. One Indian, much taller than the other two, was more richly and gaudily attired. And into his feather-crown were woven the red plumes of the quetzal, the sacred bird whose plumage might be worn only by an emperor under the old regime.

The tall red man spoke a few words to Pedro in an authoritative manner, and the latter, after making obeisance, turned and hurried back to us.

"He ees the great Bahna, the holy one!" said Pedro. "He would 'ave speech weeth the señores."

"All right. We'll see him," replied Mabrey. "Send him in."

A few moments later Pedro bowed the tall Indian and his two companions into the room. The two shorter men stood with arms folded, one at each side of the doorway, but the tall man advanced to meet us.

"I have come," he said in English as good as our own, "to warn you to leave. You are in great danger."

"From whom do you bring the warning, and what is the danger?" asked the professor.

The Indian's face remained expressionless—immobile. "The great god, Nayana Idra, speaks through me. I am his prophet. Not so long ago I warned the man whom you came to seek. He would not heed my warning, and he is gone. So you seek fruitlessly. You dare the wrath of the Divine One in vain. Go now, before it is too late, or on your own heads let the blame rest for that which will follow."

"Am I to understand that you are threatening us with the vengeance of this fabulous monster living in your alleged bottomless lake?" asked the professor, a trace of anger in his voice. "You seem well educated, and I confess that I am puzzled by a man of your apparent learning professing such superstitions."

"I have studied the learning of your people," replied Bahna, evenly, "but I have studied many things besides. You overreach yourself in calling them superstitions. They are the religion of my race, of which I am the hereditary leader. They are truths which you would neither appreciate nor understand. I have come to warn you, neither as a friend nor as an enemy, but solely as the mouthpiece of Nayana Idra, whom I serve."

"And who, pray tell, is Nayana Ira?"

"Nayana," said Bahna, with the air of a teacher lecturing a class, "is the Divine One, Creator of All Things. When he chooses to assume physical form he is Nayana Idra, the Terrible One, wreaking vengeance on those who have ignored or defied him."

"In his physical form," said the professor, "what does he look like?"

Bahna pointed to one of two great golden discs suspended in the pierced and stretched lobes of his cars. On it was graven a multi-headed serpent like that cut in the rock at the place of sacrifice.

"This," he said, "is man's crude conception of his appearance."

"May I ask," said Mabrey, "in what manner you received the message which you have conveyed to us from this alleged deity?"

His features as inscrutable as ever, the Indian drew a roll of hand-woven cloth from beneath his garments. Then, glancing about him, as if looking for a place to spread it, he walked to the desk, behind which Anita was sitting, unrolled it, and laid it down before us.

"There," he said, "is the message. Heed it and you will live. Disregard it, and you will meet with a fate more terrible than you can imagine."

We looked at the cloth curiously. It was embroidered with hieroglyphic symbols resembling those cut in the face of the sacrificial altar.

"When I awoke this morning," said Bahna, "this magic cloth was spread over me. The message says: 'Today there will come to the mountain three white strangers with their servants, to seek him on whom our vengeance had fallen. They are not of our people, and cannot understand our truths. Neither can they become our servants. You will warn them to leave, lest our wrath fall upon them.'"

"You seem," said the professor, "to have cooked up a most interesting, if unconvincing cock-and-bull story. If you are able to make yourself understood to Nayana, you may tell him for us that we will come and go as we please. And now, Bahna, I bid you good afternoon." By not so much as the flicker of an eyelash did Bahna betray the slightest emotion. Folding his cloth, he replaced it under his clothing and marched majestically through the doorway, followed by the two men who had accompanied him. We watched the three until they disappeared in the jungle. Then the professor reloaded his pipe, lighted it, and sat down in his chair.

"Now," he said, "we can go on with the diary." Anita sat down at the desk, reached for the diary, looked surprised, then alarmed, and searched fearfully, frantically through the books and papers on the desk. Then she sank back with a look of despair.

"I'm afraid we can't," she said, weakly. "The diary is gone!"

AFTER our evening meal, Professor Mabrey and I sat on the porch smoking our pipes and listening to the patter of the rain and to the almost incessant rumbling of thunder that had commenced with the advent of darkness. Anita was inside, looking through her father's papers. The cook-fire of Pedro and the two Misskitos had sputtered and gone out, and I guessed that they were, by now, comfortably installed in the mosquito-bar draped hammocks they had swung in the hut.

"This chap Bahna sure slipped one over on us," I remarked, thinking of the episode of the afternoon, "Seems to me there must have been something important in that diary—something he was afraid to have us see."

"Undoubtedly," replied the professor. "It was careless of me not to watch. These natives are deucedly tricky."

"Speaking of natives," I said, "I've been wondering if Bahna really is a native. He certainly doesn't look like the other Indians here. And he's educated."

"I've been wondering the same thing, myself," replied Mabrey. "Bahna is not a native name. I doubt if it is a proper name at all. Sounds more like a title. And his features were more Aryan than Mongoloid. With a turban instead of a feather crown he'd pass for a Hindu."

"Hasn't it been determined that there is some connection between the religions and traditions of the Far East and those of the early American civilizations?" I asked. "Seems to me I've heard or read something of the sort."

"It is a subject," he replied, "on which ethnologists have never agreed. It's pretty generally conceded, I believe, that all American Indians are members of the Mongolian race—blood brothers of the Chinese, Japanese, Tibetans, Tartars, and other related peoples of the Old World. Students of symbology have found evidence which seems to link all the great civilizations of antiquity. And Colonel James Churchward has correlated them all as evidence that the first civilization developed in a huge continent called Mu, situated in the Pacific Ocean, and, like the fabulous continent of Atlantis, sinking beneath the waves after its mystic teachings, had prevailed in the Americas, the then still flourishing Atlantis, Greece, Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, India and other coexistent civilizations.

"The royal race of Incas, it is said, more nearly resembled Aryans than Mongols, while many of the Aztecs had a strongly Semitic cast of countenance. It's a pity that the destructive fanaticism of the conquering Spaniards made it impossible for us to learn more than a very small part of the religions and traditions of these peoples. According to our recent tricky visitor, as well as our own observations, there must have existed here at one time a cult worshipping Nayana, or Nayana Idra, a many-headed serpent."

"Which brings us," I replied, "to the consideration of what we saw in the lake during the shower this afternoon. I'm positive that I saw several green, snake-like things of immense size, waving above the water. You saw it, too, as did Anita."

"The whole thing," said the professor, "smacks of the magic of India. Standing in the midst of a crowd, a Hindu fakir throws a rope up in the air. To every member of that crowd it appears to stand stiffly erect while he climbs to its top. But to the eye of a camera, it is lying stretched out on the ground while the fakir creeps its length on all fours. Mass hypnotism. The same thing is true of the trick of growing a rose from a seed in a few minutes, while playing a hautboy. The rose simply does not exist, except in the minds of the audience. And neither, I am convinced, does the monster we saw this afternoon have any existence, except, perhaps in the minds of the credulous natives who have been taught to believe in it. We have been hoaxed, and I, for one, don't propose to give any credit to the reality of the thing."

"It certainly looked real enough to me," I said, "and there wasn't any fakir in sight to hypnotize us."

"He wouldn't need be in sight," replied the professor. "Our minds were all prepared for the thing before it happened—our imaginations keyed to the highest pitch. A fertile field for the mass hypnotist."

AT this moment, Anita, who had been standing in the doorway for some time listening to our discussion, came out on the porch.

"I've just found something," she said, "which proves that my father believed in the reality of the Nayana Idra."

"What is it?" asked the professor.

"A short time ago I went into the bedroom for a handkerchief. Dad's khaki jacket was hanging there, and I noticed a book protruding from the pocket. It was his notebook, done in pencil, and very sketchy and incomplete. But I'm sure that if we can guess some of the things that are implied by these notes we can find the key to the mystery, which Bahna stole when he took the diary. Evidently the notations in the diary were mostly elaborations of these notes, written in ink in order that a complete and permanent record might be preserved."

"And you say he believed in the existence of the monster?"

"Without a doubt. Listen to this:

"'Another native stolen from village last night during rain. Went to see tracks. Like those of enormous serpents—many of them.'

"And here's a note made some days later:

"'Saw it for first time today, during shower. Great green arms writhing above water. Heard sound. Turned and strange Indian was standing behind me. Seemed to materialize from nowhere. Must be secret entrance in rock. Dressed like ancient high priest. Name Bahna, Called thing 'Nayana Idra.' Warned me away. I laughed. Went on fishing my specimens from the reservoir to take back for observation. When I looked again he had disappeared.'"

"Which goes to prove my hypnotic theory," said the professor. "Bahna was standing behind him, influencing his imagination with his subtle art when he thought he saw the monster."

"Here's a note made a week later," said Anita.

"'Some trouble to decipher characters. Mystic symbols to be read only by adepts of inner circle. Will figure out formula yet. Tried the ipecacuanha. Hydras all dead. Must have been too strong. Ancient high priests clever biologists and chemists. Created and destroyed own gods at will. Must try weaker solution. May have been modified by something else.'"

"What do you make of that, professor:" I asked.

"It seems that my friend, the doctor, was on the wrong track," said the professor. "He thought the things real instead of fantasies. He should have called the ancient priests clever psychologists instead of biologists."

"But what of the ancient formula? And what was he doing to the hydras with the ipecacuanha?" I asked.

"The formula was probably a lot of mummery," he replied, "like burning incense in a temple, or like the magic philters which still persist in our time and are efficient only to the extent that they inspire faith or wield the power of suggestion. The fact that they used ipecacuanha in this formula it not significant, as I see it. It contains emetine, a powerful emetic or an active poison, according to the dosage. I can understand that the hydras would be killed by a strong solution, as it is known to be particularly destructive to amoeboid life."

"But where do these strange hydras fit in:"

"Accessories to the mummery, somehow," he replied, "Possibly living miniature replicas of the fabulous monster, to assist in establishing belief in the creature, Giving color and mystery to the thing, like the doves of Isis, or the white dove that supposedly whispered heavenly secrets in the ear of Mohammed, while extracting a pea therefrom."

"Here is a later note about the hydras," said Anita. "'Weaker solution killed all but one. Put this under glass. Gonads seem to have atrophied. Died shortly after return to solution. Something wrong.'"

"It seems to me," I said, "that the doctor was convinced there was some connection between the hydras and this mystery, and that he was experimenting to find out what it was. Evidently he had some ancient documentary evidence of the mystical nature to go on."

"And being mystical in nature," retorted Mabrey, "it was probably as unreliable as it was unscientific."

At this moment our discussion was broken into by a loud shriek of fear and agony from the direction of the hut. Peering out through the screen, I made out, by the almost constantly recurring flashes of lightning, two figures running as if the very devil were after them. One plunged into the jungle and the other came dashing toward the cottage.

Then I heard a final, despairing shriek, which seemed to come from high in the air. Looking upward I beheld, silhouetted against the background of lightning-illuminated clouds, an enormous thing taller than a tree, with hundreds of branches, or legs. It appeared like some gigantic tumble-weed walking on its branches through the jungle with terrific, Brobdingnagian strides. And waving helplessly above the tree-tops in the grip of one of these branches was the limp and helpless figure of one of our Misskitos.

Meanwhile, the man who had been running toward the cottage arrived—bolted up the steps and through the door. It was Pedro.

"Maria Madre save us all!" he panted, his eyes rolling with terror. "Eet's come! Eet took Jose! Reached through the door and jerked heem out of his hammock! Hide! Hide queeck, or eet weel get you all!" Without stopping to think I dashed out of the house, unholstering my colt forty-five. Then I emptied its six chambers at the great trunk, swaying there above the tree-tops. Whether or not I hit it I do not know. There was no apparent effect. But an enormous tentacle came slithering down toward me, then another and another, blindly searching the clearing like exploring earthworms.

"Come in here, you fool!" shouted Mabrey. "Come in, I tell you!"

As if in a daze, I stood there, unheeding, watching the monstrosity that towered above me. Then a great, green, snaky thing struck me, knocked me down. Stinging, numbing pains shot through me. I was up in an instant, but it found me again—wrapped around my body, pinioning one arm—a band of stinging, burning agony. I pounded it ineffectually with my empty gun.

Mabrey leaped out—a machete gleaming in his hand. I was swung swiftly upward. The machete flashed, and I was dropped flat on my back in the mud. Big as I am, Mabrey caught me up and half carried half dragged me into the house, that severed, stinging, snakey thing still wrapped around me. He flung me savagely on the floor of the living room, and hurriedly closed all the doors and windows. The snakey arm relaxed, and I got up, still in excruciating agony from that stinging, nettle-like embrace.

Immense slimy tentacles were sliding over the roof, exploring the walls, pressing on the window panes. The arm that held me was writhing on the floor, a viscous green fluid oozing from the severed stump. It filled the room with a musty, unclean smell—a sickening charnel odor, as if an ancient tomb had been desecrated.

"Your machetes" shouted Mabrey. "Watch the window! It may break the glass!"

Scarcely had he spoken ere a window pane shattered—fell in a tinkling shower. A writhing green arm shot through the opening, touched Anita, and wrapped around her slender waist.

As she screamed in deadly terror and pain I sprang to her assistance. But she was jerked toward the window with incredible swiftness.

I SWUNG my machete at the writhing thing that was dragging Anita toward the window. It moved downward as I struck, and consequently was only cut half through—green liquid oozing from the wound. Goaded to a frenzy by the cries of the tortured girl, I slashed again and again at the great green arm, not realizing that my second blow had bitten clear through, and that I was merely cutting the severed end to pieces.

The oozing stump was withdrawn through the broken window. Brought to a realization of what I was doing, I turned and found Anita swaying—about to fall. The relaxed tentacles had slipped from her, but I knew from experience the stinging wounds it had left. She was biting her lips—attempting to suppress her moans of agony. I caught her in my arms—spoke to her soothingly. And she sobbed hysterically, her head on my shoulder.

Suddenly I was aware of a change outside. The patter of the rain had ceased. The muttering of the thunder was dying in the distance. And the mighty tentacles no longer slithered and groped outside the cottage. Suddenly the moon appeared from behind a cloud, flooding the drenched mountainside with its soft light. A gigantic figure like a huge upturned, uprooted tree appeared on the rim of the crater, wobbled unsteadily for a moment, and then disappeared.

"It's gone, Anita!" I said. "The thing has gone back to its lair! We're saved!"

"I'm so glad," she whispered, "but I am hurt—terribly."

The professor had gone into the laboratory. In a moment he returned with bottles, gauze and cotton. After washing our smarting, itching wounds with alcohol, he swabbed them with mercurochrome. Presently I felt some relief, and Anita, plucky little thing that she was, declared that her pains were gone.

Pedro made coffee, which he served piping hot to all of us. Nobody cared to sleep, so we sat and smoked, sipping our coffee and discussing our terrible visitor.

The professor, of course, said nothing more about his theory of mass hypnotism. Nor did I have the heart to twit him about it. He had saved my life. No doubt his presence of mind in closing the doors and windows had saved all of us.

He examined the two green things that had ceased to writhe on the floor, except when touched. Then they showed startling reactions.

"They are hollow," he said, "with terminal orifices much like the mouths of anemones. The tubes are lined with cells that digest the creature's food, taken in through the orifices. The ectoderm-the outer skin—is dotted with the stinging nettle cells which can be employed either for defense or aggression. Without a doubt the thing is an ambulatory hydra—a gigantic individual belonging to the strange species we saw in the reservoir. Throw the filthy things out, Pedro. The stench is nauseating."

Impaling one of the green things on his machete, Pedro held it at arms' length, dragged it to the screen door and flung it outside. He returned for the other and handled it in a like manner, then closed the door softly and tiptoed back into the room.

"Seex men come!" he said excitedly, "over the hut. They get here een a minute!"

The professor, Anita and I hurried to the window. Clearly visible in the moonlight were six figures, poking about the ruins of the native hut. One, taller than the others and wearing a large feather crown, was familiar to all of us.

"It's Bahna," said Mabrey, "with five of his followers. No doubt he means trouble, or he wouldn't have brought all those men with him. See to your side arms, everybody. Don't start anything, but he ready to finish anything they may start."

I loaded my emptied forty-five. Pedro and the professor were similarly armed with forty-fives and heavy machetes. Anita carried a thirty-eight and a lighter machete. Our shotguns and rifles stood in a corner.

"You stand guard over those guns, Pedro," ordered Mabrey. "We'll use our side arms if attacked, and make a dash for the other weapons, but we don't want to appear hostile unnecessarily. It may provoke an attack."

We took seats and waited, tensely alert. The professor and I smoked our pipes. Pedro puffed at his inevitable cigarette.

The splashing of footsteps sounded on the rain-soaked ground outside. The screen door opened. There was the tramp of feet on the porch. Then Bahna stalked into the room, his features as expressionless and inscrutable as before. Behind him walked five Indians. Two took positions on each side of the door. The other remained standing in the doorway with arms folded.

The professor nodded pleasantly, as if such visits in the dead of night were of ordinary occurrence. He was an admirable actor.

"Evening, Bahna," he said. "Beautiful night after the rain. Won't you sit down and have some coffee?" Bahna stared straight at the professor, his face expressionless as a moulded death mask.

"I warned you," he said, "of the wrath of Nayana Idra. You did not heed my warning. Had I not risked my own life to beseech him to leave, your lives would have been forfeit."

"And who," asked the professor evenly, "is Nayana Idra? I saw no such person."

"If you saw him not, then are you blind indeed," replied Bahna, "for he has carried one of your servants away with him, and another lies at the edge of the clearing, dead from fright. He looked upon the Divine One, and died."

"Perhaps you refer to the giant ambulatory hydra as Nayana Idra," said the professor. "We saw that, to be sure. If you prevailed upon it to leave, we are much obliged, as it is a disagreeable beast. But I was of the opinion that it had left because the rainstorm had ceased. Couldn't stay in the open air long, you know, unless the rain was falling. It would be dehydrated."

"I was about to warn you to leave, for the second and last time," said Bahna, "but it seems that you have been prying into secrets that do not concern you. Under the circumstances, I can no longer permit you to go."

"Indeed!" The professor stood up. "Get this, Bahna. We'll come and go as we damn please."

"Fool!"

The Indian suddenly whipped something from beneath his clothing. It looked like a glass ampulla. With his other hand he drew a handkerchief from his pocket, held it over his nostrils. Then he shattered the ampulla on the floor. Instantly the air was filled with an acrid odor. Through a dim haze I saw the other Indians holding cloths to their noses. I tried to reach for my forty-five, but couldn't raise my arm. My senses whirled. The room, its figures distorted, seemed to revolve about me. Then I lost consciousness.

WHEN I came to my senses once more I was in total darkness, lying, bound hand and foot, on a cold, damp stone floor. My head felt as big as a balloon. Every muscle of my body ached as if it had been pounded. And recurrent waves of nausea added to my general feeling of unpleasantness. Someone was speaking in the darkness quite near me. I recognized the voice of the professor.

"Must have been a concentrated, highly volatile solution of some member of the hemp family in that ampulla," he was saying. "Possibly cannabis indica, the stuff your people call marijuana, Pedro."

"Ees damn' bad stoiff, I tal you," said Pedro. "I feel lak I been dronk for whole year and the wild horse, she's jom all over me."

Then I heard the voice of Anita.

"Isn't that something like hashish, Uncle Charley?" she asked.

"It is hashish, or bhantj, so called in the Orient."

Evidently I had been the last to recover from the torpor induced by the drug.

"A clever chemist, that Bahna," the professor was saving, when we were suddenly half blinded by an unexpected glare of light.

A door had been silently opened by an Indian. Just behind it was a room flooded with sunlight shining in through a large, iron-barred window. The Indian came in, followed by three companions. Each carried a machete with which he cut the ropes from our ankles. Then we were helped to our feet.

"Holy One send for you," was the curt remark of the leader. They led us away through the sunny room, and along a narrow hallway which presently opened into another room lighted by sputtering candles set at intervals in holders in the wall, and giving off a heavy perfume of cloying sweetness.

Seated on a glittering, jewel-encrusted golden throne on a dais at one end of the room, was Bahna, staring straight ahead of him, his features as inscrutable and expressionless as if they had been of graven bronze.

Our four conductors stood us in a row before the throne. Then they departed noiselessly, leaving us alone with Bahna. He addressed us collectively, his expression changeless.

"Twice," he said, "have you earned death, and twice has the great god, Nayana Idra, spared you. Nayana Idra seeks votaries, not corpses, therefore I, his mouthpiece, offer you a final opportunity to live. The Divine One can use all of you, alive and well—can bring happiness and greatness to all. Your scientific knowledge, Professor Mabrey, can be employed in his service. You might in time, become one of his adepts—help to spread his religion as it was spread before, and will be again, to the four corners of the earth. He could use your strong arm, Jimmie Brown, and yours, Pedro, to fight in his service. He requires a High Priestess Consort for his earthly vicar, such a one as Señorita de Orellana, with youth, culture and beauty. Make oath, all of you, that you will observe his commands as administered through me, that you will make no attempts to escape, and you will be admitted as honored members of our cult. I await your answers."

"You won't have to wait long for mine," replied Mabrey. "It's 'No.'"

"That goes for me, too," I said.

"And for me," said Anita.

"An' for me," said Pedro defiantly, "you can pliz go to hal."

"Perhaps," said Bahna, apparently unperturbed, "you will all he glad to decide otherwise when you have seen what you shall shortly see. For I swear to you all, that your fate shall be as the fate of the one who is about to die, if you persist in your folly."

He clapped his hands, and four Indians came in to take us away.

WE were conducted from the throne room to another smaller one, where our hands were unbound and we were given breakfast, while a guard, armed with a machete, stood over each of us. After breakfast our hands were bound behind our backs once more, and we were all very effectually gagged. Then we were taken to the sunny room through which we had passed some time before, and led up to the barred window. Looking down from this I saw that we were just above the place of sacrifice which we had observed the day before. The window through which we were looking had been concealed from below by the jungle growth.

Evidently a ceremony was about to take place, for the terraces were lined with what appeared to be four orders of priests, from neophytes to acolytes. Bahna, the adept, was nowhere in sight. Just as the sun reached the meridian, the priests began chanting a somber, dirge-like melody in a minor key, to the weird accompaniment of drums and reed instruments. This chant kept up for perhaps five minutes. Looking around, I saw that the shores of the lake were lined with thousands of spectators, who must have been drawn from a large part of the surrounding territory.

The chanting suddenly ceased, and eight acolytes stepped forward, blowing conch shells. The din was terrific. The other priests were shouting something in which I could catch, from time to time, the word "Nayana Idra." I judged from their manner that they were crying a summons to their snakey god. Suddenly I saw, waving above the water, writhing and twisting in their green and menacing ugliness, the tentacles of the gigantic hydra.

All noise ceased as if at some secret sign, and standing in a wisp of curling smoke on the top terrace below me, apparently materialized from nowhere to this spot directly in front of the great engraved stone, I recognized the tall form of Bahna, attired in brilliant ceremonial robes and wearing a hideous mask, Beside him stood an Indian maiden, naked save for an extremely short apron of plaited sisal, and some jeweled breast ornaments. Her head was covered by a black cloth hood, and to her bands, which were bound behind her, was tied a heavy, grooved stone that must have weighed at least twenty-five pounds.

As Bahna advanced with slow, measured steps, the priests began a soft, weird chant. Descending the terraces, he guided the girl, who was not only unable to see because of her black mask, but from her automaton-like movements, was either under the influence of some drug or hypnotism.

When the High Priest and his victim crossed the bridge and neared the altar steps, the chanting increased in volume. Drums, reed instruments and conches once more added to the din. The volume of sound was terrific—almost car-splitting when, after mounting the steps, priest and sacrifice reached the top of the altar.

Bahna led the girl out on the stone which projected over the water, For a moment he stood there looking down at the writhing green arms below. Then there was a quick, outward thrust of his arm, the flash of a brown body in the air, and a boiling and seething of the water for a moment after it disappeared.

Scarcely had the boiling subsided, ere the high-priest himself, holding his hands for a moment above his head, dived straight down into the water.

I was astounded—mystified. It seemed to me that this was nothing short of suicidal. But then I was not, as Professor Mabrey had previously remarked, conversant with the complex ramifications of savage cunning. It was an act which was capable of producing a powerful effect on the minds of the watchers—would prove to them that Bahna was really friendly with this terrible god—if Bahna should later reappear before them alive.

The din continued. Suddenly I was aware that Bahna was again standing in a cloud of smoke on the center of the top terrace before the graven stone plate. His costume and mask were as dry as they had been before he took the plunge into the water.

The weird music ceased. But there went up from the throats of the watchers a great cry of applause.

Bahna removed his mask. Then holding his hands aloft, he stilled the shouting of the multitude and addressed them in a language which I was unable to understand. They listened silently—raptly. It was plain that he had tremendous power over these simple people.

Then our Indian guards led us away from the window, removed our gags, and confined us once more in our lightless prison.

For many hours, during which time we slept once and were fed twice, we were left to discuss and meditate on the threats of Bahna, there in the darkness. Then the door opened once more and four Indian guards came in to escort us away, our hands still bound behind our backs. They led us along the familiar route to the throne room. After conducting us before the throne, they left silently.

His features inscrutable as ever, Bahna surveyed us all. Then he clapped his hands.

From a doorway at the right of the throne, a door opened, and marching stiffly erect between two Indians, his hands, like ours bound behind his back, there entered a short, black-bearded, brown-eyed man of professional aspect, with thick-lensed glasses.

"Dad!" cried Anita.

"Anita mia!" he answered, "and Charlee, amigo! I feared you would come, but could not warn you."

"It's all right, old pal," said the professor. "We'd have come anyway, warning or no warning."

And so I knew that this man was Anita's father, Dr. Fernando de Orellana.

Bahna raised his hand. The two men who were leading the doctor, whirled him about and marched him out of the room. When the door had closed behind him the man on the throne spoke.

"Señorita de Orellana," he said, "I have permitted you to look upon your father, alive and well. If, by high noon today you have willingly become High Priestess of Nayana Idra, which is the greatest honor I can bestow upon you, your father will still be living and unharmed. If not, then will he suffer the fate meted out to the girl in the black mask at high noon yesterday, and you, willing or unwilling, will have become my slave and handmaiden.

"My people have demanded your death—have said that by raiding your camp Nayana Idra signified his desire for a white girl. But I, the mouthpiece of the great god, can tell them it was a white man they wanted. It is thus that I can save you. And as I have four white prisoners, any one will do for the sacrifice. I will permit you to choose which of these men shall live, and which man will die. One must be sacrificed at high noon, today.

"You have had sufficient time since yesterday to think this offer over. Now let me have your answer."

"My father! You would sacrifice him if I should refuse to become your High Priestess?"

"If you do other than consent now, there will be no hope for him."

"And if I do consent, only one of the others will die? You promise me that?"

"I promise that."

"They are all my very dear friends. They have risked their lives to come here with me, to search for my father. Spare me all their lives, and I consent."

"You ask too much, señorita. I cannot disappoint my people."

"Then I refuse."

"Think of your father."

"I refuse!"

"Very well. Your refusal is his death warrant, and you are my slave. When my flock has grown I will have many beautiful white slaves, though none. I swear, so beautiful as you."

He stood up and slowly drew a jeweled dagger—the only weapon that he carried—from its hilt in his sash. Then he descended the dais, while we watched him tensely, wondering what he was going to do.

My heart leaped to my throat, and I stood tensely, ready to hurl myself at him, bound hands and all, as he stepped up before Anita. He looked down at her for a moment. Then he spun her around, and cut her bonds.

"You are one slave I will not find it necessary to bind, little dove," he said, "although I shall probably have to cage you."

He replaced the dagger in the sheath, took both her little hands in one of his, and with the other chafed her wrists.

"You will not find me an ungentle master," he said. "When you have learned obedience."

Anita suddenly withdrew her hands, held one to her eyes, and swayed slightly, about to fall. Bahna quickly caught her in his arms.

"Let me go!" she cried weakly. "Let me go! I can stand!"

He released her, his mask-like features as inscrutable as ever.

"Very well," he replied. "You are coming with me now, willingly or unwillingly, as I decreed. I hope it will not be necessary for me to use force."

"It will not be necessary," she replied, "if you will first permit me to bid my good friends farewell."

"Do so," he said, "and quickly."

She came and stood before me, looked up into my eyes and put her arms around me.

"Good-bye, Jimmie," she said. "You have been a good and true friend."

"And you have been a brave and wonderful little pal," I replied, feeling, at the same time, something cold and sharp against my wrists. A slash, and they were free.

"Stand thus for a minute," she whispered. Aloud she said: "I'm glad, so glad to have known you, Jimmie, and to have been a wonderful pal. I'll always remember. Adios!"

"Adios!" I replied, still holding my hands behind me. I saw that during her apparent fainting spell she had secured Bahna's keen dagger and slipped it up her sleeve.

The High Priest evidently did not suspect her.

She went to Mabrey next, repeated her farewells, and with her arms around his lanky form, cut his bonds.

Then she stepped before Pedro.

"What!" said Bahna, losing his inscrutability for a moment, "Do you embrace a servant?"

"A faithful servant, yes."

It was then that he suspected, missed his dagger, and saw through the trick. With a snarl like that of an enraged animal, he leaped toward her. Whereupon I sprang in front of him to bar his progress.

"Fool!" he mouthed, and clapped his hands. But this action left his jaw exposed, and I swung in a right hook with all my weight behind it.

It floored him, but he was up in an instant, and I found him no mean antagonist. He was not only a boxer, but was evidently familiar with wrestling and jiu-jitsu as well. Before I had any intimation of what he was about he had seized my wrist, dragged it across his shoulder, and heaved me over his head with all his enraged strength.

As I thudded to the floor, he leaped toward me. At the same time four Indians brandishing machetes rushed into the room.

"Surrender, fools," called Bahna.

Anita had just cut Pedro's bonds. He had the dagger. It flashed outward from his hand, and the foremost machete wielder went down, coughing bloody bubbles—his throat transfixed.

With a single bound the professor secured the machete of the fallen man. And Pedro, at his heels, retrieved the dagger. I leaped to my feet, but was met by Bahna. His strong, wiry fingers seized my throat, pressed down on my windpipe. Black specks danced before my eyes. I tried to shake myself free, lashing out blindly with short rights and lefts to the body of my foe.

But the fingers dosed relentlessly. I felt my senses leaving me.

IT was the voice of Anita that recalled me to my senses. Otherwise I would have gone down beneath the choking, vise-like fingers of Bahna, never to rise again. My short-arm body blows, it seemed, had begun to take effect. I felt my opponent weakening—his fingers slipping from my throat.

Shaking myself free, I mechanically applied a hold, which had always been one of my favorites in wrestling—the crotch and half-Nelson. With the tremendous leverage which it gave me, I easily swung the High Priest aloft, then crashed him to the floor, falling upon him in order that the breath might be knocked from his body.

Still able to see only my antagonist, and without heed to my surroundings, I was surprised when, as we struck the floor together and I slid forward, my head encountered the body of another man. Bahna went limp, and I lay there panting for breath, waiting for my vision to clear.

My sight came back to me presently, and I was able to breathe without rattling my palate against the roof of my mouth. Then I saw that Bahna had fallen upon the outstretched arm of the Indian whose throat had been transfixed by Pedro's dagger. Anita was bending over me, pulling ineffectually at my shoulders in an effort to help me up.

"Come," she said, "his back is broken. Bahna is dead."

And so there passed the brilliant mind of the High Priest into the knowledge of that eternity of which he and his kind professed to teach, his back broken by the outstretched arm of his fallen servant.

I stood up, swaying like a drunken man, while Anita steadied me, her arm around my waist. Pedro and the professor, their machetes dripping, were reconnoitering at the door through which the doctor had been taken. The three remaining Indians lay on the floor in pools of their own blood. A machete is a messy weapon.

"Can you walk, Jimmie?" asked Anita. "We want to look for Dad."

"Sure can. Give me one of those meat axes."

She pressed a blood-stained machete into my hand. We were all armed, now, Pedro, in addition to a machete, carrying the dagger with which he could do such deadly execution.

With Mabrey leading the way, we crept off down the unexplored passageway along which Dr. de Orellana had been taken. Upon rounding a bend, we came suddenly upon an Indian guard. The professor leaped forward to attack, but Pedro's dagger flashed, its deadly work completed before the guard could even cry out or draw his weapon.

He slumped in front of a doorway before which he was evidently doing sentinel duty. We entered, and found ourselves in an immense, splendidly equipped laboratory. Chained to a table before which he was working with test tubes and retort, was the doctor. And near him, machete in hand, stood the other guard.

The doctor and Indian both saw us coming at the same time. The guard opened his mouth, about to cry out, when the little man at the table hurled the contents of his test tube into it. Strangling and coughing, the Indian raised his weapon to put an end to his prisoner, but before it descended, the professor's blade split his head open and he fell to the floor, dead.

We found the keys to the doctor's chains in his pocket and quickly released him. In turn the doctor embraced his daughter and his friend. Then Pedro and I were presented.

The doctor greeted us cordially, with all the courtly dignity of the Spanish gentleman. Then his leisurely manner vanished.

"We 'ave moch work to do, amigos," he said. "Two things there are, which must be accomplished. Thees monster must be keeled, and then we must escape the superstitious natives who are assembling to see the sacrifice. Weeth the help of my frien', Charlee, eet can be accomplished, but I must be in command.

"You, Jeemie, weel take Anita up to the observation room where you weel see the last sacrifice. Charlee and Pedro weel be my assistants."

I took Anita up to the room from which we had watched the last ceremony, after the doctor had insisted that I would only be in his way, and that it would be necessary to do some things which it would not be pleasant or seemly for Anita to witness.

As the sun reached the zenith there was a repetition of the ceremony we had witnessed the day before. The waving green arms of the hydra appeared again, amid the din of conches and the shouting for Nayana Idra. Then the noise ceased, and I was startled to see, standing in the thinning smoke screen where Bahna had stood the day before, someone of his precise height and build, garbed and masked in his ceremonial accoutrements. This time, instead of leading a native girl, the High Priest appeared to be half dragging, half carrying the body of a white man, dressed in the clothing of the professor and wearing the black hood over his head.

It was only because I knew that Bahna was dead, that I was able to discern that the professor was dragging the body of the High Priest. Make-up and acting were so clever, however, that Anita was deceived into thinking that Bahna had come to life. With a cry of horror she clutched my arm.

"Quick! We must save him!"

I reassured her, whereupon she relaxed in the hollow of my arm, and, in the pleasure of her sudden nearness, I almost forgot to watch the ceremony.

Exactly duplicating the exhibition of the day before, the professor hurled the limp body to the monster that waited to receive it in the water below. For a moment he watched it disappear in the pellucid depths—then dived exactly as the priest had dived. A short time later he reappeared in a puff of smoke, dry-clad, on the rock below us, spoke a few words to the multitude, and dismissed them. Then the smoke arose around him once more, and when it floated away he had disappeared.

Anita and I hurried through the throne room into the laboratory. There we found the professor, the doctor, and Pedro.

"How did you do it, professor?" I asked.

"My part was easy," replied Mabrey. "After we had prepared the body and dressed it in my clothing, I put on the make-up and stood with it in the revolving door—the one that looks like a carved slab cut into the crater wall. A puff of smoke, a quick turn, and I stood outside at the correct moment. After feeding the hydra, I waited for it to sink out of sight, then dived and swam back through the opening which leads back under the altar and into the laboratory. Here I made a quick change, putting on dry raiment that duplicated what I was wearing, and once more reappeared. I spoke a few words and made a few passes that the doctor had taught me then disappeared by means of the smoke and the revolving door.

"You may be surprised to know that the monster was not called by the conches nor the yowling of the priests, but by tapping two stones together under water in the underground stream that communicated with the lake from the laboratory. It had been trained to respond to this signal by using it each time it was fed.

"But it was the doctor who was the brains of the whole thing and who made everything possible. He can explain the facts of our coup better than I."

"Knowing what I know it was ver' simple," said the doctor. "First I tal you about thees Bahna. He ees well educated and ees really a descendant of an ancient race of priests—a cult that existed all over the world in olden times. In India it worshiped Narayana, the divine one, creator of all things. Narayana is pictured as a seven-headed serpent.

"In Greece it worshiped the Hydra. Nayana Idra is evidently a corrupted combination of the two words, Narayana and Hydra, used on this continent by the old adepts whose game was stopped at this place by the advent of the Spaniards, Bahna is a contraction of Bab Narayana, or the gate, or door to Narayana—in other words, the way to God.

"Thees Bahna was perhaps the only one in the world who knew the inner secrets of the old cult. How he learned them, I know not. Perhaps he succeeded in doing what I tried to do—deciphering the old rock inscriptions, so cleverly conceived and executed that they have one set of meanings for a neophyte, a second more secret meaning for an acolyte, and a more secret symbolical meaning for an adept—a man of the inner circle.

"They were clever biologists and chemists, those old adepts, although weeth the cleverness was meexed a certain amount of superstition.

"They learned, somehow, that eef a certain ambulatory hydra were immersed in a solution of ipecacuanha and other herbs in just the right proportion, and later removed to pure water and well fed, its growth limitations would be removed, that ees, it would continue to grow as long as it continued to live and feed, like a reptile. Of course many of the hydras immersed in the solution died, but they believed that when one survived and began to grow, the soul of Nayana had entered into it, and that the great god was thus assuming physical shape.

"I was learning these things by experimenting with the hydras from the reservoir, and by deciphering the inscriptions. Bahna discovered this, and as I knew too much for his safety, captured my servant and me one evening, as he was putting my meal on the table, by putting us to sleep with a glass bomb. My servant was fed to the hydra, but because of my scientific knowledge I was kept a prisoner to help the adept in his work."

"How did the solution remove the growth limitations of the hydras, doctor?" I asked.

"It seems to 'ave operated by atrophying the gonads, which are situated in the ectoderm, either destroying or modifying their hormones. This type of hydra is hermaphrodite and does not bud or multiply by fission, so naturally its reproductive functions are stopped by this treatment. Reproduction begins when the limit of growth has been nearly attained in the normal creature, but by destroying the normal functions of the gonads, reproduction is eliminated, and growth continued indefinitely.

"Having found a way to construct so awful a god, it was necessary for the adepts to find a way to destroy it when it had sufficiently terrified and subdued the populace to give the priests undisputed power. This was done, I found, by filling the body of a victim with a solution of aconite, which was deadly to the monster. Bahna, however, was a modern scientist, and obtained, I found, a large quantity of refined pseudo-aconitine, the most deadly poison known to science. It was this poison which he intended to use in one of his victims after the people in this neighborhood had been properly subdued and he was ready to destroy the monster. Weeth the help of Charlee and Pedro, I injected it into the hydra's veins after draining them of blood. My friend Charlee dismissed the people so they would not discover that their terrible god had been killed, or that any deception had been practiced on them, thus paving the way for our escape. Let us go and see if the poison has worked."

We went hack to the observation room and looked out. The crater was entirely emptied of human beings. And floating on the surface of the water, moving limply up and down with the waves that rippled across the lake, was an enormous green tangle—the limbs that had once walked in the rain, terrorizing the countryside. Thousands of fish, of many sizes and varieties, were tearing at them with such voracity that it was evident they would soon disappear.

"Bahna ees dead," said the doctor, "and his man-made god died weeth him. So ends the chapter. But you, Jeemie, who are so full of questions, permit me to ask you one. Why ees it that you and Anita stay so closely together, your arms around each others?"

I'm sure my face turned three shades redder than was its normal wont. But Anita snuggled closer, reassuringly.

"You are so good at deciphering mysteries, doctor," I said. "Why not figure this one out?"

Whereupon, reading the consent in her starry eyes, upturned to mine, I kissed her full upon the lips.

"Por Dios!" exclaimed the doctor, his arms around us both, "I geeve up! The man who can explain the mystery of love has not yet been born!"