RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

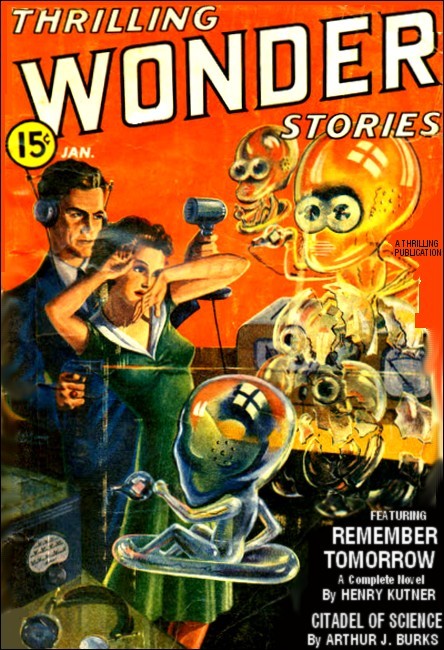

Thrilling Wonder Stories, Jan 1941, with "The Robot Beasts"

Dr. Fletcher created a new era for mankind, but one

man's

lust for power turned his invention into a mockery!

In the center of the collection stood a

lifelike figure of a handsome young man.

THE large laboratory in the basement of Dr. George Fletcher's home did not look its part. In fact, anyone entering the place would think himself in a museum of natural history. What appeared to be a large variety of stuffed animals, birds and reptiles, stood about the place in large numbers. But, instead of standing on pedestals, the creatures stood on the concrete floor itself, or were lined up in rows on the shelves.

Some of those on the floor were in pens, while a number which occupied the shelves were in cages. Yet all were motionless as statues as Dr. Fletcher descended the stairs and came into the room with his peculiar, dragging limp induced by paralysis. He was closely followed by Skag, the Great Dane, who was his almost constant companion.

The doctor was short and rather potbellied, with a fringe of graying hair. His hands trembled constantly.

He contemplated these creatures of his wearily, yet with the pride of a creator. There were tiny mice and moles of various colors and types; rats, guinea pigs, rabbits, cats, dogs. There were turtles, frogs, salamanders, lizards and snakes.

And in the very center of the collection stood the doctor's two favorite subjects—a lifelike figure of a handsome young man, with the features of an Apollo and the physique of a Hercules, and a huge, sleek Great Dane which exactly resembled Skag.

For Dr. Fletcher they represented a lifetime of toil and study. For each and every one of these creatures was not merely a stuffed animal, bird or reptile, but a delicately and intricately constructed robot in which the scientist had attempted to induce a natural degree of the intelligence of its kind by brain transplantation.

The brains, immersed in a nutrient solution which required renewal only once in fifty years, were in crystal brain cases, from which wires, attached to electrodes, ran to various parts of the robot anatomies, acting as motor and sensory nerves.

With muscles and tendons of tough, contractile plastic, and a system of levers, gears, wires and chains of light, strong aluminum alloy; powered by supercharged, lightweight storage batteries in the body cavities, these synthetic creatures were designed not only to see, hear, feel and smell, but to move and react to peripheral stimuli like the original animals.

Doctor Fletcher did not enjoy killing these animals to perfect his experiment. He was not a cruel or ruthless man at heart, but a humanitarian and philanthropist.

GLORY did not interest him or motivate his actions. He thought only of benefiting the human race, of human minds in fatally injured or diseased bodies. Once his experiments were perfected, he would change all that suffering.

And especially, he thought of the great scientific, inventive and artistic minds of the future which might be saved for the benefit of their fellows. Because of his invention they would be able to live not one, but many lifetimes.

As the doctor approached a pen in which a small black Scotty stood staring fixedly, he bent over and his trembling finger found a button concealed beneath the thick fur of the neck.

Instantly, the dog came to life, wagging its tail, leaping, barking and offering its head to be scratched. Its movements were so natural and lifelike that anyone not acquainted with the doctor's secret—and it was a secret shared only by one other human being—would have thought it a real, live dog.

This dog was his greatest achievement. The dog brain, which had now been in the case for some seven months, had learned to control the body perfectly, and showed by its reactions that it not only retained the canine intelligence which it had originally possessed, but was actually learning new things.

Many other experiments had not been so successful. Not one of the birds could fly. And a large number of the animal and bird robots had lost all intelligent movement entirely. Quite a number, also, were still without brains. Among these were the doctor's two latest creations, and, in his opinion, his greatest—the Great Dane, and the godlike youth.

Originally, the doctor had planned to use the brain of Skag in the Great Dane robot. But he had become so attached to the animal, and the animal to him, that he could not bring himself to order his assistant, young Doctor Frank Dornig, to perform the operation. Instead, he had purchased another dog of the same size, breed and build as Skag for the purpose.

With a sigh, he shut off the robot dog's battery, and made his dragging way to the swivel chair in front of his work-bench. Here, his shaking, fumbling hands found tools and some bits of wire and plastic which were needed to complete the mechanical Great Dane as soon as possible.

Skag lay down behind his master's chair. But, a moment later, he bristled ominously, then sprang to his feet with a deep growl, at the sound of the footsteps of young Dr. Dornig.

Just as Skag had shown a fondness for Dr. Fletcher, he had exhibited a fierce dislike for the younger doctor. Doctor Dornig, nevertheless, fed and cared for him, and tried his best to make the dog like him. But to no avail.

Young Dr. Dornig was as handsome as his employer was homely; as sure and strong and deft as the older doctor was weak and doddering. The godlike robot had been modeled after him by the old doctor, and closely resembled him in every detail.

The old man was very fond of his assistant, and secretly planned to leave him all of his possessions, though this was something he kept to himself. Outwardly, he was usually gruff and sometimes stern.

He looked up as the young man approached, his masklike features showing no emotion whatever.

"The new Dane has arrived, Doctor," said Dornig.

"Good," Fletcher approved. "We're all ready for him. I have only a few small adjustments to make and a couple of wires to install. Won't take me half an hour. In the meantime, you may operate on the new dog in the surgical room, and dispose of the carcass in the usual way. Here's the brain case."

YEARS before, Dr. Fletcher had performed these delicate brain operations

himself. But, as the shaking of his hands grew worse with the encroachment of

the paralysis agitans [*], he had been compelled to give it up, and to find

some one else to take his place.

[* Parkinson's disease.]

Young Doctor Dornig, fresh from his interneship, had gladly accepted the position, and had sworn never to reveal the secrets of the old doctor's laboratory until Fletcher was ready to give them to the world himself.

But the old doctor would not be ready to do that until he had achieved his supreme creation—a human thinking machine.

The synthetic body and brain case were ready, but as yet, no brain to control it had become available. It would have been possible to obtain the brains of some of the criminals who had been executed in lethal chambers with the brain unharmed. However, the doctor didn't want to put the brain of a criminal into this godlike robot of his. He wanted it to be governed by a brain with a clean ethical code, and intelligence and erudition that would be above the average.

Such a brain could only be obtained by accident—some one fatally injured whose mental qualifications measured up to his standard, but whose brain was intact. For such a brain, he would pay, from his immense fortune, a hundred thousand dollars to the heirs of the deceased.

Hospitals within a range of a thousand miles of his laboratory, which was on the shore of Connecticut, had been notified of this offer. Such things had been done before, time without number. And yet, the doctor had received only a few offers, and these from individuals whose mental powers were not, in his opinion, suitable for the completion of his experiment.

The right type of man, brought back to life through the doctor's scientific wizardry, could not only have the opportunity of renewing his acquaintance with relatives and friends, but might make the doctor a skilled laboratory companion and assistant, as well as a living testimony to his knowledge and skill. He had even thought of having Dr. Dornig remove and transplant his own brain in the case that was ready.

However, he knew that certain of his brain cells had been destroyed by paralysis, and that, as a robot, he would still have the same physical infirmities. So he had reserved himself only as the last desperate expedient.

Doctor Dornig started off with the brain case, then suddenly turned.

"Want me to take Skag out for a walk now?" he asked. "He hasn't been out this morning."

"Yes, take him out for a few minutes," Fletcher said. "But don't stay away long. I'm anxious to complete this job as soon as possible."

The young doctor took down a chain leash from the wall, and walking over to where Skag stood beside his employer's chair, snapped the hook through the collar ring. The big dog growled softly at his approach, but followed him in dignified silence after the hook had been snapped into place.

Dr. Dornig's expression of polite deference changed swiftly to one of avaricious cunning as he reached the top of the stairs. His usually steady hands trembled slightly, as he led Skag into the operating room where another Great Dane, almost the dog's exact double, was still confined.

TOTALLY unaware of the old doctor's benevolent plans for his future, Dr.

Dornig had plans of his own. He had kept the old scientist's secrets well

because he had planned that they should benefit himself, and that one day

they should make him master of a world empire. He was insanely jealous of the

great mind that was housed in that weak, trembling body.

He was nerve-weary from the long months of confining, secret work, tired of carrying out the orders of the old man who treated him as if he were just another robot. Another robot, indeed!

Soon there would be another robot—a robot containing the great mind of Dr. Fletcher. And that robot would be compelled, by torture if necessary, to do his will, to carry out his instructions, to assist in making the vigorous, ambitious young Dr. Dornig master of the world!

He had gone over his plans a thousand times. As a robot under his domination, Dr. Fletcher would assist in the creation of robots which would, in turn, make more robots, and these more, until he should have an army of almost invincible warriors. Their brains would be supplied by vigorous young men and women kidnapped for the purpose—kidnapped at the stage when they could easily be moulded to his will, and trained to obedience and loyalty to Dornig alone.

Their brain cases could be surrounded by armor of stainless steel, that would turn machine-gun bullets. Their bodies, encased in cuirasses of similar material, would do the same. They could not be gassed or drowned. Injuries to mechanical parts could always be repaired. Nothing short of a terrific force that would blow them to bits, a weight or blow that would crack the brain case, or an acid or disintegrating material that would attack the metal envelope, could really kill them. The entire robot body could be broken to bits, but if the brain case were still intact, it could easily be installed in another mechanical body.

He envisioned a mighty army of such robots setting out to conquer the world for him—robots flying strato-battle-ships and dive bombers, as well as strato-cruisers, aerial torpedo boats and smaller combat craft. Robots driving armored tanks and crushing all resistance before them. And eventually, robot armies carrying his conquests to every part of the globe, making him supreme master of the world!

The old doctor was almost helpless now. But Skag must be put out of the way first. Skag, Dornig realized, was dangerous. He chuckled softly, for he was about to transform Skag, also, into a robot!

Dr. Dornig permitted Skag to sniff the other huge Dane through the slats of the crate, in order to divert his attention while he prepared the needle. Suddenly, he sank it home, a terrific dose that paralyzed the big dog almost instantaneously.

Twenty minutes later, he placed the brain of Skag in the open brain case, poured in the life-sustaining solution, and sealed it. Then, he pushed the carcass into the electric furnace which they used as a crematory and closed the switch. This done, he opened the crate in which the other Dane was confined and placed Skag's collar around its neck.

He wanted to do this thing right. There must be no slips. He made sure there were witnesses to the fact that he had taken a Great Dane, which the neighbors could not tell from Skag, for a walk. He stopped and chatted with several of them before he cut across the thickly wooded acreage behind the little village toward the highway. Once on the highway, he removed the collar and struck the dog a vicious blow with the chain. It yelped and loped away at top speed. That dog, Dornig reflected, would not be seen in these parts again.

On his way back, he paused long enough to bury the collar and chain. Then he returned to the laboratory...

DR. FLETCHER had not been fooled by his young assistant's attempt to be

casual when he offered to take Skag for a walk. As a matter of fact, the

daily task had always been so distasteful to Dornig that he had never before

suggested it himself, but had waited for the old doctor either to walk the

dog himself, or request him to do so.

So engrossed was Dr. Fletcher, however, with his work, that it was some time before the little warning voice that had been trying to break through his preoccupation with his difficult and intricate task, finally registered on his objective consciousness. At that moment, he heard the door above open, and knew that his assistant was leaving the house.

He limped across the room and opened one of the iron shutters which guarded the secret of his basement laboratory from the world, then peered out.

As he suspected. Dr. Dornig was leading, not Skag, but the other dog. A glance at his wrist-watch told him that his assistant had had ample time to remove the brain of his canine pet and reduce the carcass to ashes.

He shook his head sadly, then mounted the stairs to the operating room. There lay the brain of Skag— it could be no other—in the brain case he had prepared for the other dog.

Laboriously, Dr. Fletcher climbed the stairs to the third floor. Then he mounted the iron ladder which led to his observatory on the roof.

This was fitted with a large, mounted telescope for scanning the heavens, but there were also several pairs of powerful binoculars for observing the terrestrial landscape.

He selected a pair and watched every movement of his young assistant, until he saw that he was ready to return to the house. Then he returned the glasses to their place, descended to his laboratory, and once more returned to his work.

As he sat there, mechanically completing his task, and awaiting the coming of his young assistant, he pondered the latter's cruel deception, seeking a motive.

He knew that Dornig disliked Skag, but reflected that he could easily have got rid of him months before had he desired to do so. Why, then, had he chosen this particular time and method to do away with Skag?

It was obvious that he had been scheming this very thing for many months, that he hated his employer as well as the dog. If he would serve the hated dog, thus, why not the master? Then, having turned both into robots, and knowing that the old doctor loved his canine pet, he might use his power over the latter to gain concessions from his former employer.

So disheartening was this revelation, that Dr. Fletcher began to wish himself dead and freed of such dreadful realities, forever.

His traitorous assistant, he knew, meant either to kill him outright, or turn him into a robot. Because of his vastly superior physical strength, Dornig was confident that he could do either at will.

But though he never had any proof of the treacherous intentions of his ungrateful assistant before, he had, long before he had employed the young doctor, known that, as the paralysis agitans reached an advanced stage, he must some day employ a skilled surgical assistant.

And he had been aware that such an assistant, realizing the world-shaking importance of his inventions, might turn traitor. So he had provided against such a contingency.

For a moment, Dr. Fletcher's trembling hand touched the lever of a switch above his desk, as if for reassurance. Then he hastily resumed his task as he heard the basement door click open...

BACK in the laboratory, Dr. Dornig took up the encased brain of Skag, and,

feigning weariness, descended the stairs.

"I can't tell you how sorry I am. Doctor," he said, "but Skag broke away

from me. I tried to catch him, but he got away in the woods."

The masklike face of the old doctor looked up from the work-bench. His expression told the younger man nothing at all.

"Never mind," said Dr. Fletcher. "He'll come back. He has lived here for so long that this place is home to him. Come, let us install the other brain. I am anxious to see how it will work."

For the next two hours, both men were engaged in the delicate task of installing the canine brain case, and clamping the many tiny electrodes into position. Finally, they closed the cranial cavity. The old doctor pressed the battery button on the neck of the huge mechanical dog with a trembling finger, and stepped back.

As had been expected, the Great Dane robot's movements were feeble and uncertain like those of a toddling puppy learning to work. But they progressed so well during the next half hour that Dr. Fletcher was greatly pleased.

"Take the rest of the day off, Dr. Dornig," he told his assistant. "You've been working too hard."

"How about knocking off for a while, yourself?" the young doctor asked. "You work twice as hard as I."

"Ah, but this is my life. It's both rest and recreation for me. Run along now, and report as usual tomorrow morning. I have some experiments to occupy me this evening."

Dr. Dornig left rather reluctantly. Ordinarily, he was glad for a holiday from the gruelling, exacting work of the surgical room and laboratory. But today, he was a bit worried. He had planned to remain and watch the reactions of the dog. If Dr. Fletcher found out what he had done, he intended to subdue the old doctor at once and remove his brain.

But he didn't want to do this, yet, unless his hand was forced. For if he did, he would have to finish the work on the man robot himself, or be forever deprived of the value of the old man's brain. And he was not sure that he could finish the mechanical work correctly. Once it was completed, he knew how to install the brain case and attach the electrodes. But it must work, once installed, or he could not make the old man his slave as he had planned and fulfil his own ambitious schemes.

However, since the dog showed no signs of revealing its true identity, he decided to leave.

"Thanks a lot," he said with simulated pleasure. "See you in the morning."

As the young doctor went out, the older man returned to his training of the robot dog. It was learning rapidly, and, because it contained the brain of Skag and resembled him, he subconsciously thought of it as Skag.

"Good boy, Skag!" he said, as the toddling, puppylike walk was presently replaced by the firm footsteps and upright carriage of a powerful, mature dog.

The robot dog understood, or seemed to understand, and to recognize his name. He cocked his huge head to one side, then reared up, placing both fore-paws on the doctor's shoulders, exactly as Skag had always done.

The old doctor's hand trembled more than usual as he scratched the huge robot dog behind the ear, while it evinced every symptom of pleasure.

"Skag!" he exclaimed. "Good old Skag. You remember me!"

PRESENTLY, he sat down in his chair in gloomy meditation, thrusting the dog

from him.

Instantly, the robot dog came over and laid its head on his knee, exactly as the physical Skag had done a thousand times. Suddenly the robot dog gave a savage growl, as steps sounded on the stairway—the footsteps of young Dr. Dornig.

In order to silence him, Dr. Fletcher reached down and pressed the button which was supposed to shut off the battery. But it didn't work, at first. Before he could press it again, that savage, revealing growl greeted the young doctor as he entered the room. Dornig could not help hearing it. He recognized its significance.

"So you have found out," he said, as the old doctor finally managed to shut off the robot dog's batteries. "I came back, expecting that you might."

"Yes, I've found out some time ago, as a matter of fact," Dr. Fletcher said. "That was mean of you, Doctor, merely because a dog growled at you. Skag had never harmed you."

"It was not mean, but the beginning of a great and glorious plan," said Dornig with feeling. "Why do you think I have been slaving here for you all this time? Do you think it was because of the miserable pittance you pay me? I've been a slave to you, subject to your every command and whim. But now, all that is changed. Now, I will be master, and you will work for me!"

"To what end?" asked Dr. Fletcher.

"I plan to build, not one or a few robots, but millions of them!" Dornig exclaimed savagely. "I'll turn them into impregnable soldiers. An army that will seize the U. S. Government for me, that will fly airplanes, drive tanks, man ships, and eventually conquer the world! An army trained to fight and to obey only me! You will help me to build the nucleus of this army, Dr. Fletcher. After that, you may remain on research, if you like— but only as my robot slave, subject to my every command!"

"And so you decided to use force on me if necessary, and fearing that Skag might protect me, got him out of the way first?" Dr. Fletcher asked softly.

"I had hoped that force would not be necessary, that you would see eye to eye with me and become my trusted lieutenant, and the director of all my research and production. In case you resist, I am fully capable of overpowering you. In case you decline to do my bidding, either as a man or as a robot, I have ways of torturing you that will change your attitude if not your views. Certain electrical impulses, for example, sent into the brain case through one of the electrodes—"

"Enough," said Dr. Fletcher, knowing what he meant. "Your scheme is perfectly clear to me."

"Then you will join me willingly?"

"No!" said Dr. Fletcher staunchly. "And rather than leave my inventions to you for such a foul purpose, I'll destroy everything—my plans, my laboratory, myself, and you with them, so that you will never be able to duplicate them!" He pointed with a shaky finger. "You see this switch? It is connected with a charge of powerful explosive beneath the floor that will blow this place, and us with it. I am going to use it—now!"

Dr. Dornig laughed derisively. "I took the precaution to put that little apparatus out of commission this morning," he said, grinning triumphantly. "No secrets of this place are hidden from me. And now, will you come quietly to the operating room, or must I use force?"

He took a loaded syringe from his pocket, pressed the plunger so that a drop of the paralyzing solution contained gathered on the point of the needle, then advanced threateningly.

"Go to hell!" cried the older man, and with one weak, trembling hand, seized a small hammer from his workbench to be used as a weapon.

The young man easily wrenched the hammer from Dr. Fletcher's shaking fingers, and sank the needle home...

Dr. Fletcher recovered consciousness, to find himself standing on the floor of his own laboratory. Dr. Dornig was seated in the old doctor's chair before the work-bench watching him.

"Ah, Doctor," said Dornig triumphantly. "I see you have recovered consciousness. My operation and installation were extremely successful."

Dr. Fletcher responded, but the voice was not his own. It was the voice of the robot, modeled after that of Dr. Dornig himself.

"I could not prevent your carrying out this vicious deed," he said raspily. "But you may rest assured that I'll not be your puppet. And so long as I exist as a thinking robot, I'll turn every energy to only one purpose—the defeat of your cruel and inhuman ambitions!"

Dr. Dornig lighted a cigarette, leaned back, and exhaled a cloud of smoke with apparent satisfaction.

"I don't know about that," he replied. "You are my prisoner, and you will shortly decide to do my bidding. Either that, or suffer the tortures of the damned until you beg for death!"

He leaned forward and pressed a newly installed buzzer button attached to the desk. The buzzing was instantly amplified a thousand fold in the brain of Dr. Fletcher—amplified to the point where it became a pulsing, vibrating agony. Dr. Fletcher knew that the young doctor must have connected the buzzer to one of the electrodes attached to his brain case.

He tried to reach the connection, then suddenly discovered that his wrists and ankles were stoutly manacled to two thick steel I-beams which Dr. Dornig had set in the concrete floor.

"So you feel it, eh?" Dornig gloated, releasing the pressure on the button. "Then you realize that you are entirely at my mercy. What is your decision now?"

"The same as before!" Dr. Fletcher snarled through clenched robot teeth.

"We'll see," said the young doctor, rising. "I'll give you a few hours to think it over. In the meantime, I'll continue some of my own experiments. I'm thinking of using mechanical dogs, like Skag, to fight in my robot armies."

He went over to where Skag stood motionless beside the robot which housed the brain of his former master, and pressed the battery button. Instantly, the big robot dog came to life.

For some twenty minutes, Dr. Dornig put him through his paces, and gave him various familiar commands which Skag obeyed with the same aloof dignity that had characterized his behavior toward the young doctor before his transformation into a robot.

"Interesting," commented Dornig to the old doctor. "Very. When you have helped me to construct some more man robots, and we have the brains installed, we'll build a few more of the Great Dane type. I'll leave you now, Doctor, to think things over. You will, for the next few hours, be accorded the luxury of pure thought, with no physical effort, whatever."

He thrust out a finger, pressing the button which shut off the batteries that supplied energy to the robot of Dr. Fletcher. Then he carelessly pushed the button of the Great Dane robot and went jauntily to the stairway, mounting the steps two at a time. Dr. Fletcher could not move, but he could think. And it seemed to him that his brain, stimulated by the powerful electric current that had been driven through it some time before by means of the vibrator attached to one of the electrodes which was connected with his brain case, was ten times as productive as it had ever been before.

He could not move any part of the robot body, could not even turn or blink the eyes, which had been left wide open. But he had noticed that Skag's battery control button had failed to work when the young doctor had pressed it. And now, the huge robot dog was wandering disconsolately about the laboratory, frequently going to his old master's work-bench.

Presently, the realization came to Dr. Fletcher that the dog somehow sensed his presence in the room. If he could only convey to his old pet his present location, they might be able to work together and defeat the plans of Dr. Dornig.

He could not shout a command, but he could think one. Now, he concentrated all the power of his great brain in an endeavor to project it to the puzzled dog.

"Skag," he telepathed. "Skag! Come here!"

Mentally, he said this, over and over.

Presently, Skag began circling the robot figure which contained the old doctor's brain. Closer and closer he came, until an exploring nose sniffed at one of the manacled legs. The contact of robot to robot seemed to establish complete telepathic rapport for, with a sudden, joyous bark, Skag sprang erect, his paws draping the chest and shoulders of the motionless robot figure, begging to have his head stroked.

The pressure of one big paw on the battery button was sufficient to arouse the robot of Dr. Fletcher to full motor and sensory powers. He raised a manacled hand and patted the dog, still communicating with him telepathically. He did not dare to use the voice in the robot larynx. It might spoil everything.

When the dog had received sufficient petting, he lay down at the feet of his robot master.

Then, Dr. Fletcher, with the robot hands trembling exactly as his physical hands had trembled, found that despite his manacles he could lift them high enough to open the chest and readjust the mechanical larynx until the voice bore a resemblance to his own.

But the manacles still held him to those stout I-beams, and unless he could break or remove them, he could do nothing against Dr. Dornig.

Lying on his work-bench at least ten feet beyond his reach, was his portable electrical welding machine, with its long coil of wire which made it possible to use it anywhere in the laboratory.

If he could only reach that welder, he could literally melt off his shackles. Suddenly, he thought of Skag. Once more, he brought a powerful telepathic impulse to bear on the faithful beast.

"Skag," he commanded audibly. "Go fetch my welder."

The dog went to the desk. But here, habit conquered, and he picked up the doctor's old slippers, which still rested beneath the desk.

"No, Skag," corrected Dr. Fletcher. "On the desk. The welder."

AT the word "no," the dog dropped the slippers, but still seemed uncertain of just what was wanted. Once more, the doctor sent that powerful telepathic impulse, and repeated:

"The welder, Skag. On the desk."

Then, to Dr. Fletcher's delight, the dog reared up, seized the machine in his teeth, and brought it to his master. The doctor took it with a word of praise for the dog, then quickly applied it to the manacles that held him.

Soon freed of his manacles, he first ripped away the wire attached to the buzzer which had been used to torture him. Then he walked over to his chair, one robot foot dragging as in life.

Suddenly, it occurred to him to try an experiment. The trembling of the hands, and other effects of his paralysis which had followed him into this robot existence, were due to the fact that certain brain cells in control of the motor nervous system had been destroyed by the disease. But he knew that man has thousands of excess brain cells which are never used in a normal life time. If these brain cells could be utilized, and trained to perform the task of those that had been destroyed—

He removed the top of the robot head, and began swiftly to readjust the many tiny electrodes clamped to the brain case. He worked tirelessly for more than two hours, changing and experimenting before he had succeeded in correcting his trembling hands. Another half hour gave him full control of the bad leg. And still another removed the masklike expression from the once handsome face.

Now, he could think, move and act like any normal human being, but without hunger, thirst or fatigue. He was a veritable superman, not only in appearance, but in efficiency as well.

His brain was always keenest when he had something to occupy his hands. But all of the material on the workbench had been cleared away. Yet, he must do some of his keenest thinking to defeat the ambitious schemes of Dr. Dornig. He suddenly recalled that the control button for Skag's batteries was difficult to shut off and needed readjusting.

He unscrewed the button, then bent over his work-bench to examine it. But at this moment he heard the basement door open, and the tread of Dr. Dornig on the stairs.

The robot Skag growled softly at Dr. Dornig's approach. The latter paused in amazement, when he saw Dr. Fletcher.

"So," he exclaimed. "You've managed somehow to free yourself. Well, I'll soon fix that."

He sprang forward, and the old doctor stood up to meet him. As Dr. Dornig thrust out a finger to press the control button, he felt his wrist caught in a grip of iron—a grip that had ten times the strength of that of the athletic young doctor. Then he was hurled backward, so that he crashed into, and overturned a heavy table.

Instantly, the young doctor sprang to his feet, and realizing that the old doctor had recovered his dexterity, and that his own strength was futile against that of this superman he had helped to create, he picked up the table. Tearing it free from its electrical connections, he hurled it straight at the robot doctor.

It struck the robot body full in the chest, and knocked it off balance.

Dr. Fletcher felt himself crashing to the concrete floor, the heavy table on top of him.

With a cry of triumph. Dr. Dornig sprang forward once more. But at this moment, Skag went into action. A fierce roar burst from his throat, as he reared up, his fangs snapping for Dr. Dornig's throat.

The latter laughed derisively, and reached for the control button to shut off the robot dog's battery. To his horror, he found that the button was missing. Snarling, he concentrated all of his attention on keeping those snapping fangs from his throat.

The muscles of the huge mechanical brute were untiring and would go on functioning as long as the current remained in the battery. The muscles of the powerful young doctor were tiring rapidly under the terrific strain, and he was growing weaker from a loss of blood. His hands and arms were ripped open in a score of places.

Growling, the mechanical dog sprang in for the kill. He seized the throat in his fangs and quickly ended the existence of Dr. Dornig and his mad dream.

In the meantime, old Dr. Fletcher, who had just succeeded in freeing himself from the weight of the table and the heavy machine attached to its top, rose to his feet, horrified.

But despite his emotional reactions, he was first, last and always, a scientist. Here, he reasoned, was a healthy brain of the type he had been waiting for during these long months. An intelligent brain, alive and uninjured, and adapted to control a robot body.

If he should act at once, he could now perform the operation with deft, sure strokes, and immerse the brain in a nutrient solution until a new robot body could be constructed. He could save the life of his former assistant and make him a semi-immortal, as a robot.

Dr. Fletcher was not of a vengeful nature. But another thought suddenly interrupted him as he reached a steady, powerful hand which answered every command of his brain, for his instrument case.

The brain of the young doctor was perfect, physically, but this brain would carry with it the ruthless ambition to dominate, the sadistic cruelty which had been a part of its thought processes in life.

Some day, it might trick him, overcome him, and begin the work that would lead to the most hideous holocaust of blood and anguish the world had ever known.

Two tears coursed down the robot cheeks, revealing the agony which wrung the soul behind those mechanical features.

TURNING his face away from the bloody horror which lay on the floor, he

sought and found the severed connection which led to the charge of explosives

in the secret chamber below.

Swiftly, he found and repaired the cut in the wire. Next, he connected the alarm clapper of his desk clock to the lever that would detonate the explosives, and set the alarm for five minutes hence. "Come on, Skag," he said. '"We're going for a walk."

Skag frisked about him joyously, as he had always done before his transformation at the prospect of a hike with his beloved master.

The two ascended the stairs and left the house, a godlike superman, and a powerful superdog.

Dr. Fletcher was through with his laboratory, finished with his great work which he had performed primarily for the benefit of his fellow man.

His inventions had not brought to humanity the benefits of which he had dreamed. And he realized, now, that in the wrong hands—the hands of ruthless seekers of power—they might bring infinite tragedy and sorrow.

However, they had, through the action of his former assistant, brought him a powerful, godlike body, and the prospect of living another lifetime, perhaps more, together with the one creature in the world that loved him.

AS he and Skag reached the highway, a tremendous explosion rocked the

countryside. Dr. Fletcher didn't even look back. "Come on, Skag," he said.

"We're headed for a new life—and a new freedom."

Skag, as if he fully understood, gave vent to a joyous bark. He chased a stray cat up a tree, and then returned with his tongue lolling, to trudge contentedly in the footsteps of his master.