RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

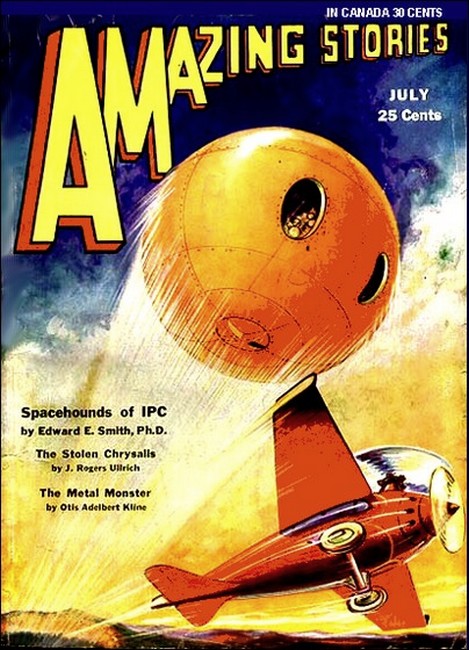

Amazing Stories, July 1931, with "The Metal Monster"

When the most powerful artillery, deadly bacteria and explosives known, and the most destructive methods available fail to be effective against some enemy's unknown weapon of war, it is time, very frequently, to turn to some simple means of combat and attack. Paradoxically, though, it is the simple thing that is so difficult to hit upon. In fact, like some of the greatest discoveries and inventions, the most destructive chemical solutions are often discovered by sheer accident. For instance, who could ever have thought purposefully of the chemical that was finally adopted by the hero of this story?—Ed.

MUCH has been written about the terrific cataclysm of 1960—the eruption of the volcano, Coseguina, with its accompaniment of earthquakes, fires, floods and storms, which carried death and destruction into Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua.

The world has been told by a thousand writers, with a thousand different viewpoints, of the awful blackness, so much more intense and so far greater in extent than "La Oscuridad Grande"—"The Great Darkness" of 1835—as to relegate the former event, awe-inspiring as it was, to insignificance.

Eyewitnesses who were fortunate enough to escape with their lives from the devastated cities, have described their varying sensations when, with noon and midnight alike, tiles slid from the roofs, walls crumbled, buildings crashed to the shaking earth like houses of cards, bells tolled futilely in cracked towers, and the air was filled with shrieks, prayers and choking dust.

But, immense and devastating as it was, it is not of this cataclysm that I would write, but of that infinitely more terrible menace to all mankind which closely followed it—which was, in fact, loosed on the inhabitants of the earth's crust as a direct result of the eruption. For I was an eyewitness of the first appearance of the Metal Menace, as well as a direct participant in the action that followed, as men struggled to shake off the fetters with which the slimy intelligences of the nether world were slowly and surely shackling and enslaving them.

It is difficult to attempt to write in an orderly fashion of those nerve- racking, reason-destroying events when they are yet so close to me, but life is fleeting, death may come to me at any moment, and there are many facts which are known to me alone, and which should be preserved for posterity. For this reason, I begin my task as chronicler now, instead of waiting for time to bring order and clarity to the vision. -Walter Stuart.

"HOOVER," I shouted through the control room phone, and my pilot, Art Reeves, skillfully banked, returning the Blettendorf electroplane almost to the exact spot and holding it there suspended with helicopters whirring.

We were directly above the crater of Coseguina. But six months had passed since its eruption, the most spectacular and destructive in the history of the world, yet it had not only ceased to smoke, but the hot lava, which had bubbled and seethed for some months in this immense cauldron of Mother Nature, had suddenly receded, and there remained a yawning black shaft, the bottom of which was sunk so far into the bowels of the earth as to be invisible.

It was to investigate this singular and previously unheard of phenomenon that my chief, the secretary of the American Geographic Association, had sent me from Chicago in the Blettendorf, together with Pat Higgins, my photographer and assistant, and Pilot Reeves.

"Descend," I said, and we began swiftly and smoothly to drop toward the yawning blackness beneath us.

Pat flashed on his keel and side lights and started his automatic cameras clicking. Four of them, like the lights, were trained on the crater walls, and the fifth was pointed straight down through the floor.

The top of the crater was fully a mile in diameter, but as we descended, the walls gradually drew closer together. Presently, when our magnetic altimeter showed that we were nearly five thousand feet below sea level, the shaft assumed a uniform diameter of about two hundred feet.

"Faith," said Pat with a grin, "this must be where the bottom dropped out of the kettle. If this keeps up, we'll be having tea with the devil in a couple of hours." I mopped the perspiration from my brow. The air in the cabin had grown uncomfortably warm. A glance at the thermometer showed a temperature of 120 degrees.

"I'm afraid we won't be able to get much closer to His Plutonic Majesty without asbestos suits," I replied. "Besides, the heat will thin our oil until its lubricating value will be nil. If we burn out a couple of helicopter bearings, we're due for a long, hard drop.

"Sure, we'd be old and gray by the time we hit the bottom," said Pat.

Watching the thermometer and magnetic altimeter, I saw that the heat was increasing at the rate of about one degree to every hundred feet of descent. When it reached 135 degrees I ordered Reeves to hover.

"We've come as far as we dare in this machine," I told Pat. "I'll take a look through the binoculars before we ascend."

I pointed my 50X Zeiss glasses downward in an effort to see the bottom of the shaft. But adjust them as I would, I could see only a tiny black speck where the seemingly converging walls—due to perspective—of the pit ended. I did notice something else, however, which caused me to utter an involuntary exclamation of surprise. The walls of the pit beneath us were of gleaming, silvery looking metal, and winding up around them was a railed metal stairway. On this stairway there was a movement—a constant flow of shiny metal globes rolling upward.

Rapidly shifting the focus for a nearer view I looked for the top of the metal wall. I found it in a moment, and the powerful glasses brought every detail so close that it seemed as if I could almost reach out and touch the gleaming railing of the spiral stairway. Never, so long as I live, will I forget the strange, almost unbelievable sight that greeted my eyes.

Standing along the railing near the end of the stairway, were four grotesque creatures, somewhat man-like in form. Their bodies were glistening metal globes, like Osage oranges, from which, in lieu of arms and legs, there projected four tentacles, apparently constructed of many little globes strung together like beads. Perched on similar but shorter tentacles above the body spheres were smaller globes, evidently the heads of the creatures. They had enormous goggling eyes, literally like headlights, both in shape, and from the fact that they cast their own rays before them.

The first three of these strange beings carried long pipes slightly curved at the upper ends. The lower ends were attached to flexible tubes greatly resembling conduit, which trailed down the stairway. The fourth held a straight cylinder about three inches in diameter and four feet in length.

The first three individuals were exceedingly busy. In fact they seemed to be the sole structural workers on the stupendous metal shaft that was swiftly rising from the bowels of the earth. The metal globes which were rolling up the stairway were of three sizes, and appeared to be living creatures, for when they reached the ends of their respective lines, all sprouted the queer tentacle-like arms and legs of the four larger creatures, and projected globular heads from their round interiors. Then those of the largest size sprang up, one by one, to the top of the unfinished wall, where they retracted their heads and limbs and rolled closely together.

AS soon as each new globe was in position, the foremost of the three large workers cemented it in place with a stream of gleaming liquid resembling quicksilver, that poured from the tube he carried, and filled in the interstices until a glistening, pebble-grained wall resulted.

The rolling globes of the middle size leaped from the end of their line to make the stairway in the same manner, cemented in place by the second tube- bearer, while those of the smallest size formed the railing and its supporting bars, and were fused into place by the third large worker.

I was dumbfounded. The idea of a race of metal beings building a structure with their own bodies, cheerfully and willingly, was almost unthinkable for me. It was something quite beyond my point of view. But then, a coral polyp's viewpoint as it fuses its body in with millions of others to form an atoll of a reef is also far from the understanding of individualistic men.

"Haven't seen a banshee, have you, chief?" asked Pat. who had noticed my startled expression.

"Take a look for yourself," I responded. "I want to know if you can see what I see."

Focusing his own binoculars he looked, then exclaimed: "Holy smokes! And I thought all the fairies were in Ireland! It's the Little People, sure as my name's Pat Higgins!"

I was looking at the fourth of the larger individuals, the one that carried the tube, wondering what his function was. Suddenly, as if attracted by the intensity of my gaze, he flashed his great goggle eyes upward. For an instant he gazed at the electroplane. Then he pointed his cylinder upward, and there was a crash of broken glass as a projectile struck the floor window.

As we were without weapons, I shouted an order to Reeves:

"Ascend! Full speed!"

"Sure, that one must have been a guard," said Pat, shutting off his clicking cameras. "Wonder what that was he fired at us."

The floor lurched as our craft shot swiftly upward. Something rolled against my foot. It was a shiny metal globe about two inches in diameter—evidently the missile which had been fired from the cylinder.

"Here it is, Pat," I said, and picked it up.

But scarcely had I done so, when it shot out segmented, tentacle-like arms and legs, and a head that was a tiny, goggle-eyed miniature of the creature which had fired it. One of the metal tentacles whipped down on the back of my hand with a stinging blow, so startling me that I dropped the thing. It instantly scurried for the broken floor window, but Pat with a "No you don't!" scooped it up in his empty binocular case and fastened down the lid.

"My grandfather once caught a fairy," said Pat, "and devil a bit of good luck did he have after that. It brought him to an early grave in his ninety-seventh year."

We emerged into the light of day, and Pat shut off his lights.

"Back to Leon," I ordered, and Reeves started the three propellers roaring as he pointed the nose of our craft up over the crater rim.

For our powerful electroplane, capable of a speed of five hundred miles an hour, the sixty-mile trip back to Leon would only have been a matter of a few minutes. But we were not destined to complete it, for scarcely had we passed over the ruins of Viejo, a little more than half the distance, ere Pat, who had been looking backward toward Coseguina, called my attention to the fact that an immense metal globe had shot up out of the crater and was following us through the air at a pace so much swifter than our own that we seemed, by comparison, to be standing still.

I focused my glasses on the big globe as it hurtled swiftly toward us. It was about a hundred and fifty feet in diameter, and constructed of the same gleaming metal that we had noted in the shaft. A minute, and it loomed, immense and menacing, almost upon us.

"Drop," I ordered Reeves.

He shut off the forward propellers, set the wings at perpendicular, and reversed the helicopters. We dropped, just in time, the immense globe hurtling over us with terrific speed. Its momentum must have carried it at least five miles ahead of us before it could turn to come back. In the meantime, we had descended to within a thousand feet of the earth.

"Hover," I shouted to Reeves, but scarcely had he checked our downward progress, less than five hundred feet from the ground, when the globe returned, plunging straight at us.

Reeves managed to swerve slightly to one side before it struck, but our left wing was torn off, and we spun crazily beneath the supporting helicopters. Then a blade broke, and we went into a swift nose dive.

I caught a fleeting glimpse of the ash-covered ruins of a great hacienda rushing up to meet us. Then there was a terrific crash—and darkness.

AN immense cloud of volcanic dust arose as we crashed through the tile-less frame of the hacienda roof. Our second helicopter had retarded our fall sufficiently to prevent fatalities, but we were badly shaken up.

The dust was so thick that I could scarcely see my hand before my eyes. The helicopter had ceased to whirl as we struck. The motor was dead.

"All right, Pat?" I asked.

"Safe and sound, chief," he replied.

"And you, Reeves?"

"Not hurt a bit."

"Good. We'd better get out of here at once and try to find a place to hide. That globe will be right back after us, I'm afraid."

Scarcely had I spoken, ere something ground against the roof, and there was a metallic clank as if a chain had been tossed to the floor.

"Follow me," I called, softly, and leaping out of the side door, groped my way through the dust cloud which was beginning to settle a little. The floor was covered to depth of more than a foot with fluffy volcanic ash, making the going difficult.

Presently my outstretched hands encountered a wall, and I followed this to a doorway. Stumbling through, I entered a large room that was in semi-darkness. I felt a hand on my arm. Then Pat whispered:

"They're after us! Hear 'em clanking around in the next room?"

"Where's Reeves?" I asked.

"Don't know. Must have found a place to hide."

We came to another doorway. The door was half ajar, and we squeezed through. We found ourselves in a small clothes closet.

I peered through the interstice between door and frame. The dust was settling rapidly, and the room into which we had crashed was partly visible through the first doorway we had entered. A number of metal creatures like those we had seen in the shaft were swarming over the wreck. Their globular bodies gleamed in the sunlight which filtered through the dust into the hole we had smashed in the roof. And hanging down through that hole was a thick metal cable or tentacle composed of globular segments which tapered slightly toward the tip.

The creatures investigating the wreck of the electroplane were about four feet in height—the same stature as the structural workers we had observed in the shaft. Suddenly I heard the voice of Reeves:

"Let go of me, damn you!"

In a cloud of swirling dust he was dragged by two of the creatures, each of which had hold of an arm, out into the sunlight. His head and clothing were thickly covered with volcanic ash. Evidently he had missed the doorway, had dug in, and had just been discovered.

Twisting, kicking and cursing, he was dragged up toward the huge tentacle. It whipped around his waist, then jerked him aloft, out of our sight. In a moment it dropped once more. With remarkable agility, the metal beings swarmed up. Then it was withdrawn, there was a clank like that of huge metal door being closed, and the roof creaked as if a great weight had been lifted from it.

"They've gone," said Pat, "and they've got Reeves!"

"Poor devil! And we couldn't do a thing! Come on." I led the way to the room into which the ship had crashed. Quickly mounting to its top, I climbed up on the unbroken helicopter blade and leaped to the roof. The huge metal sphere had disappeared.

Pat came up beside me.

"It's a long walk to Leon," he said, "and my wrist radiophone is smashed. How's yours?"

I tested it. It was tuned for just such an emergency, with that of my secretary, Miss Davis, who was back in the Hotel Soledade at Leon.

It worked. Her answer came back, clear and distinct.

"Yes, Mr. Stuart."

"Higgins and I cracked up on the roof of a large hacienda, about ten miles northwest of Leon. Send a helicopter taxi for us at once.

"Yes, Mr, Stuart. Right away."

I broke the connection, then turned to Pat.

"Think we can save any of those pictures?" I asked. "Why not, chief? The fuselage wasn't wrecked. I'll go down and get them."

The helicopter taxi arrived just as Pat came up with the cameras. We got aboard.

"Soledade Hotel," I told the driver.

In five minutes he lowered us to the flat hotel roof. I paid him while Pat unloaded the cameras. We passed them to a couple of liveried attendants, who led the way to our suite.

Miss Davis arose from her typewriter desk, concern in her eyes, as we entered.

"Was anyone injured? Why, where's Mr. Reeves?

He's not-"

"Not dead, so far as we know," I replied. "Captured. I'll explain later. Get me the secretary of the Association at once, on the radiovisiphone. Then the President of Nicaragua."

"But President Monteiro and his daughter are here in the hotel," said Miss Davis. "They came from Managua, today. Relief work, you know."

"All right. Get Secretary Black. Then I'll look up President Monteiro."

The face of my chief presently appeared in the radiovisiphone disc.

"Stuart!" he exclaimed. "What are you up to now?"

"Turn on your recorder," I replied. "Then I'll tell you."

"It's on. Go ahead."

I DID. I related every detail of the strange sights we had just witnessed, and the incredible experience through which we had just passed.

When I finished, he said:

"If anyone but you had told me this. Stuart, I'd think it some sort of a practical joke. But you are such a serious person, I believe you. Yet it's possible that you were suffering from an hallucination."

"I'll send you photographs within ten hours," I said. "Cameras don't have hallucinations."

"Right. I'll notify the War Department. Remain within call. Off."

As he spoke the word "Off," the connection was automatically broken. His face faded from the disc.

Miss Davis had gotten the President of Nicaragua on the room visiphone.

"President Monteiro will see you in ten minutes," she said. "He is in Parlor L."

I went into the next room, where Pat was busy developing his films. He had taken his small metal captive from his binocular case and confined it in a stout bird cage with a small padlock on the door. It was leaning against the bars, watching him with its round, headlight eyes, as I entered.

"Get your stuff in shape so you can leave it, Pat," I said. "We're going to call on President Monteiro in ten minutes, and take the prisoner with us."

Ten minutes later I knocked on the door of President Monteiro's suite. Pat stood behind me with his caged prisoner. We were ushered in by an attendant. The president, a small dark man with a carefully trimmed iron gray beard, was seated behind a large mahogany table. Beside him, with her hand on his shoulder, stood a slender, brown-eyed girl, apparently about twenty years of age. I recognized her instantly from the photographs I had seen of her, as Dolores Monteiro, daughter of the president, and the most famous beauty in the two Americas.

The president greeted me cordially. I introduced my assistant, and he presented us to his daughter. An attendant placed chairs.

Selecting a long, thin cigar from a humidor, and pushing it toward me with a gesture of invitation, the president said:

"And now, Señor Stuart, what is this important message you have for me?"

Briefly I told him of our strange experience—the astounding sights we had witnessed, and our narrow escape. He smoked with countenance unruffled until the end. Then he said:

"Understand me, señor, I am not doubting your word. But a story so strange as yours needs substantiation. You will not mind if I—ah—investigate further?"

"That is precisely what I hope you will do," I replied. "We have brought an exhibit, however, which I believe will convince you—a miniature specimen of the strange race of metal creatures we saw."

I lifted the cage, and put it on the table. The little creature inside it focused its huge headlight eyes inquiringly on each of us in turn, as if wondering what to expect next.

"Looks like a man-made automaton," commented the president.

"True," I replied, "yet it, and its larger fellows which we encountered, acted as if endowed with intelligence."

"You think these creatures will be—hostile?"

"Judging by their past actions, yes."

"Hum. We'll try them a little further."

He pressed a button on the table. A buzzer sounded in the next room and a uniformed aide came in.

"Dispatch three combat ships, fully armed and manned, to the crater Coseguina at once," he ordered. "Tell them to be on the lookout for flying globes and strange metal beings, but to make no hostile move unless attacked. Have one descend as far as possible into the crater while the other two stand by to guard it. If attacked, they are to defend themselves to the best of their ability. And let me hear their reports."

The aide bowed and withdrew.

"Perhaps you would like to see some photographs," I suggested.

"With pleasure," replied the president.

"I'll make some quick prints and bring them up," said Pat, rising. "Shall I leave the prisoner here?"

" Yes, leave him," said Monteiro. "I want to examine him further."

Pat went out and closed the door. The president poked an inquiring finger through the bars at the little creature in the cage, then withdrew it hastily with an exclamation of surprise as it struck at the encroaching digit with one of its tentacle arms.

"Per Dios!" he exclaimed. "This one, at least, is hostile. We shall soon find out about the others."

We did not have long to wait. The radiovisiphone hummed, and the face of the squadron commander's operator appeared in the disc.

"We are hovering over the southern rim of Coseguina. RX-337 hang? over the northern rim. RN-339 is above the shaft. It descends. A huge sphere has come out to meet it. They collide. The 339 falls, a mass of wreckage. Our machine gunners are spraying the globe with bullets, as are those of the 337. It darts for the 337, which tries to elude it, but is brought down with one side torn off. It is coming at us. Our commander has ordered a retreat. It is too swift for us. It is almost upon us.

We are d-"

There was a terrific crash, and the disc went blank. Tensely, we waited in front of the disc—the president, the girl and I. It continued blank. Monteiro rushed into the next room. I could hear him volleying orders.

Suddenly I was aware that my wrist was tingling. Someone was trying to call me. I pressed the connection of my wrist radiophone.

"Mr. Stuart Mr. Stuart!" It was the voice of Reeves.

"Art Reeves!" I exclaimed, "where are you?"

"Not much tine. Called to warn you. That little metal man guided them to you. Keep him in darkness. Leave at once. They're coming for me. Must-"

"Quick!" I said. "We must get out of here!"

Stripping the scarf from the table, I was about to muffle the cage when something struck the window-screen—ripped it away. A huge tentacle whipped into the room. Clinging to it were four of the globular metal creatures. One picked up the cage, a second seized the girl, and the other two pounced upon me, gripping my arms with their powerful tentacles. As helpless as if I had been held in a steel vise, I saw girl and cage jerked out of the window and upward. Then the big tentacle returned, wrapped around my waist, and dragged me after them.

I WAS thrown into a small, brilliantly lighted room. A heavy metal door clanged shut behind me. To all appearances the floor, walls and ceiling were constructed of seamless brown metal, without windows or doors. Even the source of the light was invisible. It seemed to radiate from the six metal surfaces that surrounded me.

On the floor lay the girl, a look of terror in her eyes.

Bending over, I lifted her to a sitting posture. The floor lurched suddenly, and I sprawled beside her. Recovering my balance, I asked:

"Are you hurt, señorita?"

"No, señor, but I am very frightened. Where are we?"

"If I'm not mistaken," I replied, "we're riding in one of the swift flying globes of the metal people."

In a few minutes there was a second lurch, followed by a sudden jolt that threw us both flat. Then a door opened in the apparently solid wall, and four of the metal creatures came in. Helping us to our feet, they hustled us out upon a platform constructed from brown metal. It was part of an extensive system of docks, along which hundreds of the globes rested. Countless others were arriving and leaving, from and for all points of the compass. Far above these flying globes I could see, through a dim haze, a great self-luminous dome—the ceiling of this tremendous underground world.

But most amazing of all was the immense city of gleaming white metal which surrounded the docks—a city of glistening towers, walls and battlements, all metal.

But conductors led us to a queer brown-metal vehicle—flat, with a hand-rail traversing the center longitudinally. In lieu of wheels, it traveled on four spheres, which supported it on idling bearings. There were no seats. Our captors, after bundling us aboard, indicated that we must stand, gripping the rail in the center.

The vehicle started smoothly, accelerating with great rapidity. I was unable to see any controls, and none of our captors seemed to be driving or steering it. Emerging from the dock, we rolled out on a broad, smooth street, paved with brown metal. Many vehicles like that we occupied were traversing this street, some of them at terrific rates of speed. Some had passengers, some carried materials of various kinds, and some were empty.

Moving in and out among the vehicles, and often traveling at even greater speeds, were thousands of silvery metal globes of divers sizes. I noticed some of them no larger than buckshot, while others were easily ten feet in diameter. I saw them, from time to time, stop at the entrances of buildings, put forth arms, legs and heads, and enter. Others, coming out of the buildings, retracted their limbs and heads and rolled swiftly away. I judged them to be factories, and afterward confirmed this belief.

We passed a building under construction, and I saw that it was being put together in the same manner as the metal shaft I had seen rising in Coseguina—the bodies of thousands of these strange creatures being utilized as building material.

Presently we drew up before a metal wall about fifty feet in height. Two massive gates, which had previously appeared as part of the wall itself, swung back, revealing a winding metal roadway which led to an immense building that stood in the center of the most unusual garden I have ever seen.

Instead of grass, flowers, shrubs and trees, it was filled with mosses, moulds, fungae, lichens and other thallophytic growths. Short velvety gray moss carpeted the lawn. There were clumps of huge mushrooms and morels, of many shapes, sizes and colors. But the most striking of all were the varieties of gigantic slime moulds.

The leocarpus fragilis with its gleaming golden spore cases shaped like elongated eggs, a mycetozoan on the borderland between the animal and vegetable kingdoms, grew to a height of ten feet. Globe-shaped physariums attained a diameter of three to four feet. And the dusky plumes of the stemonitis, massed in large clumps, waved twenty feet above our heads. Not so pleasing to look upon were the slimy, gelatinous plasmodia of the various species, flowing sluggishly about in the areas to which they had been confined, questing the food which they must have in order to produce the beautiful plumes, globes, baskets and ovoid spore cases of mature ones.

They were all creatures of the darkness—conceived and developed without sunlight—unable even to exist in the direct rays of the lord of the solar system, but multiplying and growing prodigiously, here in this weird, pale light of the nether world.

We came to a stop before what looked like the unbroken wall of the building, but here again a previously invisible door opened, revealing a circular doorway about fifteen feet in diameter.

Here we left our strange vehicle, and walked between our guards along a narrow corridor until we came to a great central foyer which evidently reached to the top of the building. Looking up, I could see galleries encircling it at each level, clear to the top. On the floor of this room near its center was a ring of black discs, each about ten feet in diameter, encircled by a narrow railing. Our captors led us out on one of these and directed us to grip the railing, whereupon it shot up into the air with considerable speed, then slanted over toward one of the higher balconies.

Peering over the railing, I saw that we were being lifted by a gigantic segmented tentacle emerging from the floor where the disc had been. After we had been deposited on the balcony the disc swiftly returned to its original position.

MANY round doors opened on the balcony, and we were conducted through one of these along a corridor to a second, much larger doorway, on each side of which stood two guards carrying metal tubes. They paid no attention to us as we were ushered into a magnificently furnished room which contrasted oddly with the plain brown metal corridors and foyer. The foyer was thickly and richly carpeted, the walls were decorated with murals near the bottom and bas reliefs above, and the ceiling was of luminous yellow metal, which shed a soft, amber light over the whole scene.

At the far end of the room a figure reclined beneath a green and gold canopy, upon a luxuriously cushioned dais raised about three feet above the level of the floor. As we drew near the throne, the figure sat up. I gazed aghast at the thing that confronted us.

At first I thought it a living human skeleton, but as we drew closer, I saw that its flesh and skin were transparent, its bones and teeth translucent, and its viscera and nervous system opaque. Its immense head, fully twice as large in proportion to its size as that of any earthly man, was encircled by a jewel-encrusted gold band, which supported an immense emerald at the center of the forehead. It wore no clothing, but its waist was encircled by a belt of golden links from which a dagger with a jeweled hilt, and several other instruments or weapons, I knew not which, depended. Its feet were enclosed in pointed golden slippers.

The horrible creature arose as our conductors brought us to a halt, and stepped forward to examine us. It poked me in the midriff with an inquisitive, gelatinous finger, pulled down my chin to look into my mouth, and felt my arms and legs. Wherever it touched me, it left prints of slime very much like those left by a garden slug. Its fingers felt cold and clammy.

Having completed its examination of me, the thing returned to its dais and reclined. Then, to my surprise, it addressed, or seemed to address me in English.

"I am disappointed in you, Walter Stuart. Although my other prisoner, Arthur Reeves, looked up to you as a leader, you are one of the creatures of the lower order. And your cranial capacity precludes the possibility of a brain large enough to receive and retain the higher training. Are there no creatures of the higher order upon the outer crust of the earth?"

"I take it," I replied, "that you consider yourself a creature of the higher order."

"I rule the creatures of the higher order," was the reply.

"These men of metal?"

"No, small-brained one. They are machines of my invention. I rule the people of my race—the higher order of creatures—the Snals. With the aid of my metal creatures, my Teks, I conquered the inner world—brought every Snal nation under my rule. They are irresistible, my Teks, when I direct them. I am Zet, conqueror and emperor of the inner world."

"I am puzzled to know," I said, "how you learned English."

"Your brain is even more deficient than I suspected," said Zet. "Our conversation is one of thoughts, not words."

"But I am speaking, and you seem to speak," I insisted. "I can hear you."

"You can speak and hear in a dream," said Zet, "yet you actually do neither. Call this a dream if you like. Or bring up, if you wish, those other words in your mind—telepathy or clairaudience. Our subjective minds are conversing without the employment of physical means. The conversation is instantly transferred to the objective consciousness.

"But who are you to question Zet, ruler of the inner world? Answer my question."

"There are no Snals on the outer crust of the earth," I said. "It is dominated by creatures called men, of which I am a specimen."

"That is unfortunate," said Zet. "I had hoped to find creatures of a higher order to conquer. But the outer crust will make a mighty empire—and I can set my Snals to rule over these inferior animals called men. It may be, too, that we can improve the race. Perhaps my nobles will take some of your females into their seraglios, thus founding a new race. Our bodies are more fragile than yours. Your brains are inferior to ours. A fusion of the races may prove of great benefit to both. It is worth trying."

"I'm not so sure that our brains are inferior," I retorted. "On the outer crust people born with heads as large as yours are usually imbeciles."

"And in the inner world, people born with heads as small as yours are invariably microcephalous idiots," he said, apparently unruffled. "But it may be that I can use you. I'll have you examined by my scientists. I couldn't use your assistant, Reeves. He disobeyed my first order and communicated with you. To disobey is death."

"You mean you killed him?"

"I did not slay him in anger, as you seem to think. He was turned over to my scientists for a thorough physical examination which they were very anxious to make. He was the first man they had ever seen, and they desired to take him apart."

"And they did this while he lived?"

"Partly. I understand that he died shortly after the examination began."

Vivisection! Poor Art Reeves cut open alive! And at the order of this big- headed, slimy monstrosity before me. Furious anger fired me—quadrupled my strength for the moment. With a sudden jerk, I twisted my arms free of the metal tentacles that held them, and leaped for the dais. My fingers ached to clutch the gelatinous throat of the thing that had ordered his death.

With lightning quickness, the hand of Zet jerked a small tube from his belt—pointed it at my breast. I felt a terrific shock, as if a powerful electric current were passing through my body. My muscles grew rigid—immobile. I seemed rooted to the floor. Then the two Teks leaped forward, seized my arms and dragged me back to my original position.

Zet replaced the tube in his belt.

"So," he said, "you are even more of an animal than I suspected. In one instant, you permitted your emotions to completely overthrow your reason. I doubt if I can use you. But my scientists will find out while I examine this other creature, which appears to be a female."

I saw the girl shudder as Zet arose and walked toward her. Then, struggling futilely, I was dragged away by the two Teks.

MY TWO metal captors took me down the corridor and out upon the balcony. Here they placed me on a railed black metal disc similar to that which had lifted us from the first floor, and we were hoisted to the second balcony above. Then they led me down another corridor, and through a circular door into a large room in which more, than a hundred Snals were working, some seated at tables, others standing before high benches on which were flasks, tubes, retorts, immense magnifying glasses, and much other paraphernalia I did not recognize.

I was conducted to a square, glassed-in room in the center of this vast laboratory, where a Snal with a head even larger than that of Zet, sat at a metal table. This room, with its glass partitions, was so situated that he could look into any corner of the laboratory without leaving his seat.

Fastened to a metal band that encircled his head was an immense lens that covered both eyes and most of his nose, so magnifying those hideous features that they were out of proportion with the others, and creating a most grotesque effect.

The two Teks forcibly seated me in a gray metal chair across the table from the Snal, and departed. I was surprised that this slimy, gelatinous individual would allow me in his presence without the Teks to guard me, but learned the reason when, under his steady gaze, I tried to shift to a more comfortable position. I was as firmly attached to the metal chair, which was in turn attached to the floor, as if I had been bound with steel bands. Yet the invisible force that held me did not manifest itself except when I tried to shift my position on the chair.

The Snal stood up, squinting at me through his huge lens. Through his transparent body and his translucent ribs, I could see his heart beating, his lungs inflating and deflating, and his stomach expanding and contracting as it disposed of his last meal. It was evident from his demeanor that he thought me an exceedingly queer looking creature. The feeling was mutual.

"You have been sent to me for examination, Walter Stuart," he said, finally. "I am Hax, chief scientist of the Snal empire."

"I suppose you'll take me apart to find out what makes me go, as you did poor Reeves," I replied.

"You say 'poor Reeves,'", he answered. "That is bad. It indicates the exercise of emotion, rather than reason. No, I do not intend taking you apart—not just now, at least. You are to be tested mentally."

He pushed a shiny metal sphere on the table before me. Suddenly it appeared to become transparent.

"A good beginning," said Hax. "You have the vision. It may be that we can use you. Step into this scene."

Suddenly, as I gazed into that metal globe, I felt myself drawn into it—felt that it had enlarged until it was as high as the sky.

I was moving—walking on a metal stairway. Globes were rolling up beside me, becoming Teks, springing up to the top of a wall. In my hands—not hands, tentacles—I held a bent tube from which gleaming liquid metal poured forth each time I pressed a small button on the side. My torso was spherical—a shining globe of metal.

When I had cemented the globe in place I waited for another to climb up beside it. Meanwhile, I glanced over the rim of the wall. It was level with the crater rim of Coseguina. And between me and that rim, thousands of other workers like myself were building a metal city on the sloping sides of the crater. Their animated building material was coming up the shaft in a steady stream, rolling up a spiral ramp that had been constructed at one side. On the crater rim, a great metal dome was rising—swiftly closing inward and upward toward the center with amazing rapidity—shutting out the daylight from above.

Reflecting the sunlight from their shimmering sides, a dozen huge, flying globes slowly circled overhead.

The vision suddenly faded. I was back in the laboratory, glued to the metal chair—a human being once more.

"You have followed well," said Hax. "Now let me see if you can control."

From beneath the table he produced two electrodes on insulated wires. He directed me to grasp one in each hand. Then once more the globe before me became clear—expanded.

I was in a huge warehouse at the peak of a pile of metal globes. I was a metal globe! I could look out through my own metal torso as if it had been a pane of glass.

"Descend." A voice came from somewhere beside me, yet I saw no one.

I rolled from my position, and down the side of the pyramid of globes. When I was half way down, the voice said: "Stop."

I halted, clinging to the slanting surface by some magnetic force which I was able to control.

"Let go."

I shut off the force, and rolled to the floor,

"Walk."

I thrust out leg and arm tentacles, put forth my metal head with its great goggling eyes, and scrambled to my feet.

"Back to your place."

Suddenly retracting head and limbs, I rolled back to the top of the pyramid and lay still.

The vision faded. Once more I sat in the laboratory before this strange scientist.

"You can control," he said. "That is good. If you can do this there are others of your race who can also do it. Your mind is unusually strong considering the smallness of your brain. We can use you."

"For what?" I asked.

"For that which you have just done. To control a Tek. Every Tek, large or small, is controlled by a Snal. By using your people to control the Teks, we will release thousands of Snals for other, more intellectual duties, to which their greater minds are suited."

"You mean," I said, "that you intend to make slaves of my people—slaves who will labor with their minds rather than their bodies?"

"Of those who can pass the test, yes. The others will go to feed the plasmodia of the slime moulds which we cultivate for food. Thus we can make use of all. There will be no waste. We are efficient, we Snals."

"Perhaps. But you haven't conquered mankind, and I don't believe you will."

"In order that you may entertain no false hopes," said Hax, "I'll show you what is now transpiring. Watch the globe."

I did. It suddenly became transparent. I was a goggle-eyed Tek, seated high in the air in a metal room situated in a great dome which covered the crater Coseguina. The work of building had been completed with incredible swiftness. I was surrounded by metal, yet I had the power of looking through it at any point by flashing a special ray from between my eyes.

A FLEET of twelve battleships was approaching from the south. They flew the flag of Nicaragua. Another fleet of seven, flying the flag of Honduras, approached from the north, across the Gulf of Fonseca. The two fleets deployed, and formed a semicircle, fronting the isthmus on which the volcano was situated. From the land side an immense army approached behind a long line of great, rumbling tanks. And two fleets of mighty aerial battleships closed in above, attended by several hundred relatively small but exceedingly swift helicopter electroplanes.

Suddenly, as if every gun in the attacking force were under single control, a terrific bombardment began. Shells from the battleships and artillery rained on that metal dome. Immense bombs were dropped by the aerial battleships and electroplanes. Projectiles of smaller caliber, from seventy-fives down to thirty-forties, rattled against that great hemisphere of gleaming metal. But not one shell or projectile so much as dented it.

This bombardment lasted for perhaps five minutes without interruption, and without any visible effect on the great dome. Then, suddenly, a thousand doors that had hitherto appeared to be a part of the solid metal, opened. From each door emerged a flying globe. Like a swarm of angry bees defending a hive, they hurtled at the attackers. Bullets rattled and shells burst against them without effect.

Two globes descended on a Nicaraguan battleship, one above the fore deck, the other near the stern. Long metal tentacles slithered down, gripping the front and rear turrets. And down these tentacles swarmed the Teks. They plunged into the turrets—down the ladders. Each Tek, as it emerged, dragged a human prisoner. One by one these prisoners were passed up into the globes. The Teks followed. The tentacles were drawn up. And the battleship, out of control, traveled aimlessly in a circle as the globes returned with their prisoners.

This scene was, at the same time, being enacted on all the other battleships. Other globes seized the aerial battleships with their powerful tentacles, boarded them, took off the men, and left them to drift unguided, or to crash. One by one the electroplanes were caught and denuded of men. The army attempted to retreat, but this was quickly prevented by a row of globes which formed on the ground, stretching across the peninsula. The Teks swarmed everywhere. Men were pulled out of the tanks—dragged away from the field pieces, or caught as they attempted to flee or hide.

All the battleships were circling erratically. There were several collisions. One ship went down, rammed by another. Aerial battleships and electroplanes were continually crashing to the ground or falling into the Gulf and the ocean. Huge tanks, driverless, climbed the peak as far as the edge of the dome, stood up, grinding at the shimmering metal, and fell over backward, their motors roaring, to tumble down the steep slope they had climbed, and smash to masses of twisted wreckage at the bottom.

In less than thirty minutes after the bombardment began, the last globe returned to the dome. And so far as I could see, not a single one of the fighters who had attacked so valiantly by land, sea and air, was left to tell the tale.

THE scene faded. Once more I was back in the laboratory with Hax. His colorless, glass-like eyes leered at me through the huge lens.

"You see," he said, "how hopeless it is for mankind to resist us. We are invincible."

"You have but defeated the forces of two small nations," I replied. "The earth has not yet begun to fight. Her scientists will find a way to defeat you."

"Her scientists are weak-minded children, compared to the most ignorant Snals," he said, contemptuously. "They are creatures of a lower order, fit only for slaves. And you will go now to begin your slavery with the rest."

Two Teks suddenly appeared behind me. Seizing my arms, they lifted me from the chair and hurried me away. As I left the laboratory the mocking laughter of Hax followed me.

The Teks took me out of the building the way I had come. One of the queer, rolling vehicles was waiting. My hands were forced down on the central rail, which glowed as if with some radioactive force. They stuck there, and try as I could, I was unable to remove them.

We passed through the gates in the wall, and threaded the city streets to a great, large structure near the cocks. A number of other similar vehicles with glowing handrails were waiting around the building. And thousands of prisoners, disembarking from arriving globes, were being herded into this building by the Teks.

Others were being driven out of another entrance I noticed that some were forced to grasp the shining hand rails, while others were bound, hand and foot, with wire, and stacked on the vehicles like cord wood. At first I saw only soldiers, sailors and airmen, wearing the uniforms of Nicaragua and Honduras. But the globes presently began to disgorge loads of civilians—-men, women and children, whites, mestizos, Indians and Negroes, evidently taken in raids on the nearby territory.

The vehicles, loaded with their human freight and each presided over by a Tek, began to form in a long line. When a train of about six hundred had been formed, we left. All traffic had evidently been stopped to let us through, for although I could see many vehicles on the other streets those through which our leader piloted us were deserted.

The vehicle in which I was riding was a half mile or so behind the one which led the procession. About half of the vehicles were loaded with the bound prisoner; and half with those held by the luminous hand rails. A load of the poor bound wretches was just ahead of me. I could hear their piteous moans. Their wrists and ankles were so tightly bound with wire that they were cut and bleeding. And those at the bottom of the pile were crushed by the weight of the ones above them.

Our train soon passed through the city, ani out upon a great metal causeway that stretched above a weird and unusual landscape of grotesque thallophytic growths. These were in orderly array, and tended by Teks. Among the cultivated plants I saw a number of varieties of gigantic slime moulds. They were cultivated in pits about twelve feet in diameter, set in rows with metal runways between them. Some of the pits contained great masses of naked, polynuclear protoplasm—the plasmodia which would later develop into adult slime moulds.

As we passed along through these fields I noticed that, from time to time, one of the cars containing the bound human beings was shunted off the causeway and along one of the tracks which ran between the plasmodium pits. Watching one of these as we sped past, I saw the Tek lift a bound human being and hurl his helpless victim into one of the pits. At the next pit he stopped and repeated the process. The grim prophecy of Hax was already coming to pass.

The men who were fastened on the vehicle on which I rode numbered about twenty. There were five naval officers, five seamen, eight Indians and two Negroes. The man just ahead of me wore the uniform of a lieutenant.

"What did they do to you in the round building, Señor?" I asked him in Spanish.

"We were given a test to see if we could control those metal creatures, señor," he replied. "Those who could not pass the test—many of them women and children—were bound with wire. It is horrible. What are they doing with them?"

I told him. He ground his teeth and cursed luridly. Presently he asked:

"And what will they do with the rest of us?"

"As long as we can serve," I replied, "we'll probably be slaves. After that, food for the plasmodia."

Of the six hundred vehicles that left the city, about three hundred drew up before a great, dome-like building. The others, with their wire-bound victims, had been shunted away to the slime mould farms.

A great circular door opened in the apparently solid wall of the building. The Tek who presided over our vehicle shut off the current in the rail, releasing our hands. Then we were herded into the building with the others—whites, mestizos, Indians and Negroes, men and women, mixed indiscriminately.

The first room in which we found ourselves was an immense lobby which encircled the building. This room proved to be the living and sleeping quarters of the Snal workers, whose places we human slaves were to take. While one-half of the workers labored in the inner rooms, the other half slept and took recreation in this apartment. Their bunks were metal cylinders about three feet in diameter and seven feet long, stacked three rows high along the outer wall. They contained no padding or covers, and were as private as gold-fish bowls. The tired workers, without bothering to disrobe, crawled into them and stretched out on the cold metal when ordered to do so by their overseers. They crawled out again to receive their meagre rations and to resume work when their sleep period had elapsed.

The overseers wore round, pointed helmets and complete . suits of scale-armor made from a dull-surfaced, dark brown metal. Their weapons were paralyzing ray tubes, like that which Zet had used on me, and queer, double-edge weapons, the blades of which looked like two meat-axes welded together, back to back, with handles about eighteen inches in length hooked at the end to hang from their belts; they carried slender metal rods about eight feet in length, the pointed ends of which continually glowed at a red heat.

WE were forced to disrobe and don the coarse aprons. In each apron were two pockets, one of which contained a glass flask and the other a shallow bowl. As fast as we donned our slave raiment, we were driven in single file past a counter, where we were issued water in our flasks and a thick, jet black porridge, which I afterward learned was made from the spores of a species of slime mould, in our bowls. It had a rank, musty flavor, and I could not stomach it at first, but as it was the only food given us, we had to eat it or starve. Most of us eventually got so we could consume the portions served us, although I doubt if anyone really learned to like the stuff.

After we had been given our garments and rations, we were herded into the immense central control room. The floor of this room rose in circular concentric terraces conforming to the contour of the domed roof above, and ending in a small round platform occupied by the chief overseer, who could thus look down on the entire workroom.

Set against the faces of the terraces were curved tables. Twenty workers were seated at each table, gazing into their control globes and gripping their electrodes. Each table was presided over by an armed and armored overseer, who gazed into a large globe mounted on a tripod, in which he could watch the collective activities of the Teks controlled by his workers. A worker, caught shirking or making an error, was punished by a searing touch from the red-hot point of the overseer's long rod.

I was assigned to a seat between two Snal workers, and noticed that this arrangement was maintained with the other slaves—first a Snal, then a human slave. The young lieutenant who had ridden on the same vehicle with me was seated just beyond the Snal at my right.

At a sharp command from the overseer, I grasped my controls and gazed into my globe. I instantly found myself a Tek, operating a gigantic mechanical shovel that was scooping up what looked like white sand from the floor and walls of a huge pit and dropping it into vehicles with globe-wheels and hopper-shaped bodies. These vehicles, each operated by one Tek, moved past in a steady stream as fast as I filled them with the white sand. One immense shovelful sufficed to fill each vehicle.

Other Teks labored nearby with similar mechanical shovels. The vehicles, I noticed, were all moving toward a great structure some distance away, from which columns of smoke or vapor were rising, and from which, at times, lurid flashes of light gave a blood-orange tint to the surrounding landscape and to the vapors that floated beneath the great vault, high overhead.

It dawned on me that this white sand must be a metallic ore—a salt of some metal—and that the building to which it was being taken was a smelter or refinery.

As I sat there working, it seemed that I developed the faculty of being two places at once—thinking two sets of thoughts at the same time. Objectively, I sat and worked in the control room. Subjectively, I operated the mechanical shovel. It was like playing a piano and singing at the same time—or perhaps more like singing an air and playing a violin obbligato. Doing two things at once, one objectively, the other subjectively, yet conscious of doing both.

The Snals had permitted me to retain my wrist chronometer, though my radiophone was taken from me. They had learned its use when Art Reeves had sacrificed his life to warn me—all to no avail.

The chronometer showed that our day was divided into two periods of about ten hours each—a work period and a rest period. The work period lasted for ten solid hours without intermission, nor were we permitted to take our hands from the electrodes even for an instant during that period. When the work period was finished, the second shift of workers was ready to take our places. We were then issued water and black porridge, and permitted to roam about in our living quarters for about an hour. At the end of the hour, however, we were peremptorily ordered into our sleeping cylinders for eight hours. We were then ordered out, fed and watered, and at the end of another hour, marched into the control room to relieve the shift that had been working while we slept and rested.

The division in which I worked, labored unremittingly at digging and loading a seemingly endless desert of white ore. I learned from workers in other divisions that some of them were engaged in smelting the ore, some in building metal cities and warehouses, others in building flying globes, and still others in transporting materials and prisoners through the streets of the subterranean cities and along the metal causeways that connected them.

With the aid of my chronometer I kept careful track of the outer world time.

Within two weeks after my arrival, every worker Snal in the building had been replaced by a human slave. The only Snals remaining were the armed and armored overseers.

I often thought of Dolores Monteiro as I had last seen her, shuddering before Zet, the slimy emperor of the nether world, and wondered what had become of her. She was a lovely creature, and unspoiled, despite the adulation she had always received.

Although certainly not human, Zet greatly resembled a human being in form. He had spoken of an experiment—an attempt at crossing the races. And I feared that the beauty of this girl might have tempted him to force her into his own seraglio. The thought was revolting. And the uncertainty was almost as maddening as the definite knowledge would have been.

During the hours after and before the sleeping periods, I used to walk around the building, scanning the faces of all the white females. At the end of a month I was still looking for her, but looking hopelessly.

Then, one day, I was startled by the familiar sound of a girl's voice behind me!

"Señor!"

IT was Dolores Monteiro who had called to me. She was wearing the coarse slave apron, but even in this rough garment she was ravishingly beautiful. My heart stood still as I looked down into her eyes for a moment, scarcely realizing that the object of my long quest stood before me.

"Señorita!" I exclaimed. "I've been looking for you everywhere."

"And I for you," she replied. "When were you sent here?"

"That first day," I answered. "And you?"

"Shortly after you left me standing before Zet," she replied. "But this is an immense place—almost a city."

"Then Zet did not harm you?"

"No," she replied, "but I will never forget the feel of his cold, slimy hands on me." She shuddered at the memory. "It was nauseating. Ugh!"

"Yes, I know," I said. "But didn't he do or say anything else?"

She answered me, almost in a whisper.

"That is the reason I had to find you. He did say something else, and ordered me not to tell. To disobey him is death, they say, but I must confide in you."

"Don't say it," I warned her.

"But I must. There is a reason. He said I would be sent away with the other slaves for the time being, to learn to work and to become accustomed to the ways of his people. But he said, also, that he would give positive orders that I should not be harmed, for someday soon he would honor me by sending for me."

"You mean-"

She nodded despairingly.

"I should kill myself at the first opportunity, of course, but I wanted to find you first—to tell you, the one person I know and can trust in this horrible place, so that if you live and some day meet my father and mother you can tell them the truth. They might otherwise think that I—that I went willingly. And there is no hope of escape. So you see why I had to tell you."

"'While there is life there is hope,'" I quoted. "Don't give up. Will you meet me at this spot after the work period?"

The call to work sounded as I spoke.

"I'll be here," she replied, and hurried away.

Some moments later I sat down at my work table, my senses in a whirl. My electrodes lay untouched before me, until a searing pain on my bare shoulder and the smell of my own burning flesh brought me to a realization of my surrroundings.

"To work, quickly!" snarled my overseer, "or there will be a worse burn."

I snatched the electrodes, and with my shoulder smarting from the touch of the red hot rod started my Tek at its apparently endless task of shoveling white ore.

The young naval lieutenant, whose alert, snapping, black eyes missed very little, saw my punishment and forgot, for a moment, to watch his globe. During that moment I saw his Tek topple from the platform on which it was working and fall into the pit.

With an angry roar the overseer seared the lieutenant's back.

"Dolt!" he thundered. "Get that Tek up at once, or I'll burn you to a crisp."

What happened after that took place so quickly that it was all over in less than a minute.

With a roar as angry as that of the overseer the peppery young lieutenant dropped his electrodes, stood erect, and sprang at the throat of his tormenter. So quick and unexpected was the attack that he was almost upon the astonished overseer before the latter realized what had happened.

Snatching his paralyzing ray cylinder from his belt, the Snal pointed it at the lieutenant, freezing him in his tracks. Then he stepped back and with a fiendish grin at his helpless victim thrust the red hot point through the brave lad's heart. Withdrawing it deliberately, he shut off the paralyzing ray, permitting the body to slump to the floor.

This exhibition of cruelty so filled me with rage and revulsion that I was tempted to hurl my globe at the Snal's head, and follow the throw with an attack. But the thought of Dolores deterred me. She would be waiting for me—expecting me to meet and help her.

Another slave was thrust into the lieutenant's place, and his body was carried out by two Teks.

"Take heed, slaves, from the death of your fellow," said the overseer, "and rebel not against authority lest you share his fate."

Dolores met me at the beginning of the rest period, and we went together for our food and water, then sat down on the stone floor to eat.

Before we had finished eating, a number of Teks came in, bearing the sections of a huge metal screen, which they welded smoothly together and set up in the middle of the floor. Several Snals came a short time thereafter, and connected it with a complicated-appearing machine, while the slaves flocked curiously around.

When their work was finished, a life size image appeared on the screen. It was Zet, ruler of the nether world, his emerald diadem sparkling above his slimy features.

He began to speak and every voice was hushed. To me, he seemed to be speaking English. Dolores told me afterward that she thought he was speaking Spanish. And a Misskito Indian I later interrogated was positive the great "Glass Face" had spoken his native dialect.

Zet told us that the screen had been installed for our entertainment and information, and that, through it, he would keep us constantly posted on the progress of his conquest of the world. We would thus be made to realize, he said, how hopeless it would be for us to rebel against the fate which nature had intended for us—that of serving the Snals, who were as superior to us as we were to the beasts we had domesticated. He ended by promising that those of us who served faithfully and well would be rewarded later, when his empire was established, by easier work and positions of power among our fellows.

Zet's image faded from the screen. It was followed by that of another Snal—a short, stocky individual, whose ornaments were richly powdered with jewels.

"I am the Voice," he said. " I speak for Zet, Lord of the Inner and Outer Worlds. Behold the progress of his conquests."

THE image faded and a large map of the Americas appeared on the screen,

"The portions marked in green are under the dominion of Zet," said the Voice. "He moves slowly but surely, taking what he wants when he wants it."

From the northern border of Mexico, through Central America, Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela, the map was shaded green! And all this in thirty days!

The map faded, and in its place we were shown moving pictures in full color. Managua, rebuilt capital of Nicaragua, was shown first. In the heart of the city rose an immense metal dome—shiny and incongruous, like some false growth appearing on the fair body of the earth. We were shown a glimpse of an inner room of the great dome. President Monteiro and his staff were here, guarded by Teks and bullied by an armored Snal who seemed to be Zet's vice-regent of the nation. There were other, flatter domes near the outskirts of the city. Beneath these, beds of slime mould had been planted. They were being tended by human slaves, and fed both with the bodies of men and domestic animals. Just outside this ring was another, in which were taller domes like the one we were in—control buildings in which human slaves toiled with their minds, that the Teks might work the will of their Snal masters.

We saw flashes of other capitals, each with its great shining dome centrally located, and its encircling rings of metal-covered slime mould beds and control buildings. Bogota, Caracas, Quito, Mexico City, San Jose, San Salvador and the rest, all were under the yoke of the conquerors.

Teks rolled about the streets—swarmed everywhere, searching out human victims to be dragged before the conquering Snals, who remained in their huge metal buildings or in the flying globes. Tiny Teks no larger than pin heads spied on the people unseen. Conspirators against the tyranny were thus quickly detected, captured and fed to the plasmodia.

We were shown the northern battle front, where the United States had stretched a huge army from gulf to ocean to protect its territory. It was not a battle, but a farce, in which the Teks were sent out at will of the controlling Snals, to drag men from the trenches, the tanks, or the decks and cabins of aircraft, and whirl them away in the flying globes, against which the most powerful weapons of the world were powerless. New weapons were being tried—oxyacetylene flame-throwers—that would cut through steel plates as if they had been paper—bombs, loaded both with nitric and sulphuric acids, in the hope that these might prevail against the obstinate metal. But they had no more effect on it than water has on glass.

Some of these things we saw. Some were told to us by the Voice. But I do not think there was a man or woman in the building who was not convinced of the truth of all of them, and the utter hopelessness of our situation. Man's knell of doom had sounded. His place in the sun was being slowly but surely wrested from him by these slimy intelligences of the nether world.

The South American republics had also extended a great defensive line across their continent. But it was even less of an obstruction to the conquerors than that of the United States.

After each work and sleep period, Dolores and I met at the same spot. We would eat our block porridge together, then go and stand in front of the screen to learn the latest news of the earth's conquest.

In another thirty days the southern half of the United States and more than half of South America were under the sway of the Snals. The opposing armies had been completely routed, and most of their field equipment destroyed. Our screen was tuned in with exploring globes flying over the areas as yet unconquered. And they showed people fleeing northward in every means of conveyance at their disposal. Canada swarmed with refugees. Air- and water-liners loaded to capacity were leaving for Europe, Africa and Asia. And the advance of the metal menace continued steadily, relentlessly.

Dolores came to mean much to me—more than the whole world. I had never told her, had not more than touched her hand. But she could do more with her eyes than can most girls with arms and lips.

It was because of the hopelessness of our situation that I did not speak to her of love or marriage. I suspected, however, that she knew of my love, and dared to hope that she returned it.

I always looked forward to my meetings with her as the only bright spots in this career of mental drudgery. Like those of the other slaves, my brain was being turned into a machine to work the will of the Snals. And it might have become as dulled and listless as did the others had it not been for her bright companionship.

During those first two months the Snal overseers began to select women from among the slaves to share their quarters with them. Each overseer had a private apartment, jutting out from the outer wall of the building at its base. These apartments were set at intervals, clear around the building, and where their round doors were placed, no sleeping cylinders were piled. Some went fearfully, under the threat of the red hot torture rods. But many preferred to die in agony.

A number of overseers had asked for Dolores—my own, a tall fellow named Lak, among them. But the head overseer had his orders. She was to be saved for Zet until such time as the ruler should send for her, unless— Every overseer knew that she had been commanded to keep this secret from the other slaves—that if she disobeyed, death would be the penalty. And each overseer combined in his person, the powers of judge, jury and executioner.

Many times I noticed Lak watching us furtively when we were together. Once I turned, and saw him standing close behind us as we watched the news screen. But even then, I did not guess his purpose.

It was, when I had computed that about two months of earth time had passed, that I eagerly sought our rendezvous after a work period, but Dolores was not there. I waited more than ten minutes, but she did not put in an appearance. Then I noticed a Misskito Indian, seated nearby licking his porridge—smudged fingers and eyeing me significantly.

"You look for white señorita?" he asked.

"Yes. Have you seen her?"

"In there," was the laconic answer. He pointed with his porridge-smeared thumb to the door of Lak's apartment

I LOOKED cautiously about me. None of the Snals seemed to be watching my movements. Endeavoring to appear unconcerned, I walked slowly toward the door of Lak's apartment. It took less than a minute to reach the edge of the pile of sleeping cylinders. Again I glanced slowly around. So far as I could see, neither Snal nor slave was paying any attention to my movements.

Dodging into the passageway between the piles of cylinders, I tiptoed to the door. It was closed, but gave when I tried the fastening. I opened it cautiously for a little way, Lak was standing with his back to me, holding Dolores by her shoulders. Neither could see me.

Entering soundlessly, I closed the door.

Lak was saying:

"You have earned death, slave-girl, but I can save you. Only I heard you tell the secret of Zet to the slave-man. You must make your choice now—your life or the love of Lak."

I had heard more than enough. With a single bound, I stood beside them. Seizing the armored shoulder of the Snal, I spun him half around.

His burning rod stood in a rack, but his chopper and paralyzing ray cylinder still hung from his belt. With a grunt of surprise and anger, he grabbed for the latter. But his visor was up and I swung for his face.

The result was astounding—and sickening. My arm was buried, half way up to my elbow in his great round head. My fist had crashed through his nose and the frontal bones of his face, clear into his, huge, mushy brain.

With a feeling of intense disgust, I withdrew my arm, and the metal-clad body clanked to the floor. As best I could, I cleaned the slime from my arm with a coverlet dragged from Lak's luxurious sleeping cylinder.

Dolores, who had bravely faced her persecutor to the end, now collapsed, with her face in her hands, and began weeping softly. I was about to try to comfort her, when I noticed something sputtering on the floor at her feet. Puzzled, I bent forward to investigate. A great tear trickled down between her fingers—fell to the metal floor. And where it struck, the sputtering commenced anew, while beneath it a patch of white crystals was forming.

The floor, unlike that of the main building, was made of the white metal that had defied shells, solid shot, oxy-acetylene flames and two of the strongest acids known to man, yet here it was, changing to a white powder beneath a woman's tears. After each tear drop fell the sputtering soon ceased. But the white spots spread with amazing rapidity. Presently, several of them ran together, then collapsed, revealing the wild thallophytic growths of subterranean jungle about ten feet below the floor. The hole widened rapidly, the metal flaking away in white crystals. It undermined the body of Lak, and it fell into the undergrowth while Dolores and I looked on amazed.

"A way out!" I exclaimed. "Come on!"

After dropping Lak's burning rod, I swung down on the edge of the still- widening orifice, and let go, alighting in the muck among the soft growths, with scarcely a perceptible jar.

Dolores bravely followed, and I caught her in my arms.

I stripped off the overseer's belt, which contained his paralyzing ray cylinder and chopper. When I had it strapped around my waist, I caught up the burning rod, and we hurried away through the grotesque fungoid growths.

A few steps took us out from beneath the building, which stood on metal stilts set into the soggy soil. As we emerged under the luminous dome of this strange underground world, the light grew much stronger and the vegetation taller.

Soon we were hurrying through a forest of thick slimy trunks, some of them eight to ten feet in diameter at the base and fifty to sixty feet in height—the stems of colossal mushrooms. Often we found our way blocked by these immense fungoids which had crashed to the ground, and for the remains of which, lichens and slime moulds of many varieties contended. Giant mosses of endless shapes and hues formed most of the undergrowth, and algae dominated the thousands of stagnant pools. From time to time the immense, umbrella-shaped caps overhead opened their gills to discharge millions of spores that glittered in the queer phosphorescent light as they swirled downward to settle over the weird landscape.

The animal, as well as the vegetable kingdom, was represented in variety and profusion. The lower orders dominated in size as well as in numbers. Fat, gray slugs, three feet and more in length, fed on the juices of the various plants about us. Snails of infinite variety and immense size left their slimy trails everywhere. I recognized glass snails, amber snails, agate snails, and most striking of all, great rams-horn snails as tall as camels.

Insect monstrosities buzzed busily about, or scampered over the moss. An immense thousand-legged worm, fully twenty feet in length, startled us as it crossed our path. A huge green beetle as large as a Shetland pony charged us with its huge four-foot mandibles distended, but backed up and hastily scampered away at a touch from my searing rod. A mosquito, as large as a crane, buzzed about us for some time, until I killed it with a lucky thrust through the head.

The air was heavy with the musty odors of the fungoid growths, the sickening charnel scent of the slimy creatures that lived in their moist depths, and the reek of decaying organic matter.

Stumbling, slipping, sliding, sometimes sinking knee-deep in clinging muck or splashing through water above our waists, we pressed onward, our sole desire being to put as much distance as possible between ourselves and the slave quarters.

As we hurried along I pondered much on the miracle that had wrought our deliverance from the apartment of Lak. What could there be, I wondered, in this woman's tears, that had destroyed a metal which had defied projectiles, explosives, heat, and powerful acids? In this solution of this mystery lay the key to the door of knowledge which, if once opened, would deliver the world from bondage.

And why, I wondered further, had this miracle not been wrought before? Surely many of the captured woman and children had dropped tears in the metal globes, on the metal vehicles in which they had been hauled, and on the tentacle-like arms of their captors. Then I recalled that the room in the globe that had brought me in, a prisoner, was of brown metal, as were the bodies of the vehicles in which we had been carried, and the highways over which we had traveled. The arms of the Teks, although of white metal, were of a duller cast than the globes and heads, as were the tables, globes and electrodes in the control room. The floor of the building, except in the private apartments of the overseers which jutted out over the jungle, were of stone.

But all this did not explain the enigma.

After five hours of wearisome travel, we were glad to stop and sit down on the moss for a breathing spell. I took a drink of water from my flask. It was nearly half full. I shuddered at the thought of having to drink the foul, stagnant water we had encountered. Dolores also drank some water and replaced her flask in her apron pocket.

"I'm hungry," she announced. "Do you suppose any of these plants are edible?"

"No doubt," I replied, "and it's equally probable that some of them are so poisonous that a mouthful or two would prove fatal. The question is, which are poisonous and which are edible. We have no way of knowing."

"Then what are we to do?"

"We may run across some of the varieties of slime moulds that the Snals cultivate for food," I replied. "Their spores are good to eat. And in the palace gardens I saw some gigantic morels. I think we would be safe in using these for food if we could find any. In the outer world the morel is the one mushroom form that is never poisonous."

"In that case," she said, "let us look for morels."

Rested by our brief pause, we resumed our journey. Presently the character of the vegetation changed as we came out of the marshy country to higher and drier ground. The moss was replaced by short, white snake grass. And huge, jointed reeds began to take the place of the tall mushrooms.

We had not gone far when we came to a group of large mounds uniformly about fifty feet in diameter and twenty feet high.

"I'm going up and have a look around," said Dolores, and suited her action to her words by scampering up the side of the mound. She had not taken more than five steps when one foot broke through into a compartment underneath. She withdrew it with a scream of pain, and came running toward me, her knee bleeding. Then a white thing about eighteen inches in height, popped out after her and pursued her on six rapidly moving legs. Behind it came another and another, and I recognized them for what they were—giant termite as large as pet bulldogs and ten times as dangerous.

I ran toward her, my burning rod ready for action, but before I reached her a veritable army of the formidable creatures came rushing toward us from around both sides of the mound, their great hooked mandibles snapping menacingly.

"No use to argue with those things," I shouted. "We wouldn't have a Chinaman's chance. Can you run?"

"And how!" she replied, passing me like a bullet.

I was not slow to follow, but I soon saw that we were being outstripped by the swift, six-legged creatures behind us, and that it would only be a matter of a few moments before we would be pulled down and torn to pieces.

"Climb something," I cried. "It will be our only chance to hold them off."