RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

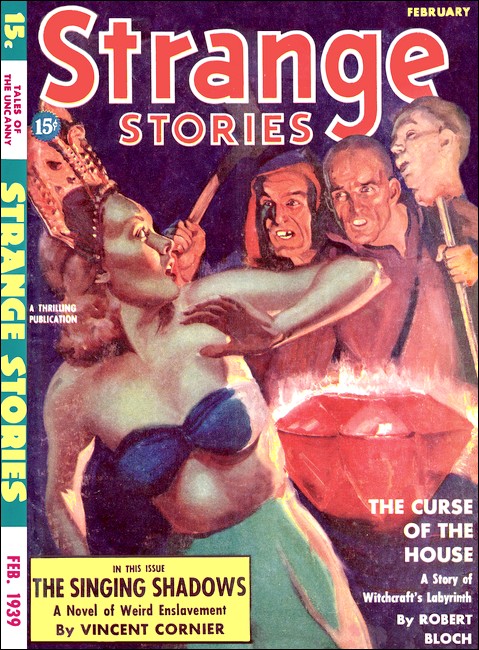

Strange Stories, February 1939, with "Servant of Satan"

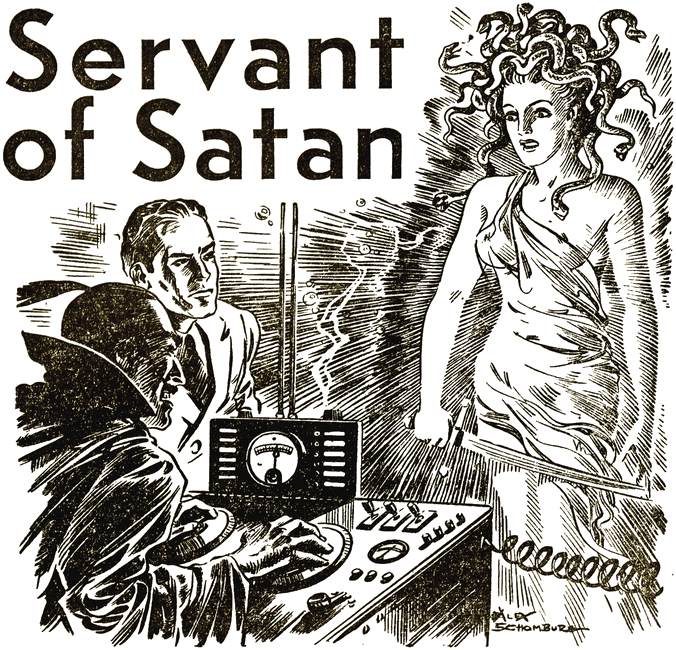

Her hair was a writhing mass of hissing snakes.

The snakes of Medusa writhe and hiss as the Devil's disciple

summons his Elemental servants to their diabolical task!

TIME is said to be a great healer—a bringer of forgetfulness of pain, and tribulation, and horror. But I cannot think back to that fateful evening two years ago without a shudder of revulsion—without again feeling myself in the grip of the ancient and incredibly malignant creatures known as Elementals.

Those Elementals—blasphemous monstrosities which orthodox science will tell you do not and cannot exist—were known to the ancients, described in their writings, depicted in their paintings and sculptures. And those of them with which I came to such horrible grips in this, our twentieth century, were restored to their immemorial and terrible power by the evil machinations of one modern man.

I felt and saw them then. I even smelled the charnel reptilian odor that emanated from their foul bodies as they materialized.

Aye, they are all around us in our daily lives. But they are unable to manifest themselves to us without human help—without living mediums from whom to suck the strength they require for their hideous and revolting materializations. God help—and God alone can help—the person who gives way to them; who lets them gain dominion over him.

I THOUGHT that I, Tom Carter, was the happiest man in the

world that Friday afternoon, two years ago, when I locked my desk

and prepared to say good-by to the gang at the office. For five

years I had slaved in order to work my way up to the job of

assistant general manager of the Brinkman Express Company. And I

had slaved with a double purpose.

April Harris and I had fallen in love five years before when our desks adjoined in the Manhattan Business College—April, with her big violet eyes and honey-colored hair. And now at last we were to be married.

Half a dozen of the boys rode down the elevator with me, waved me off as I climbed into the cab and slammed the door. "Three Stuyvesant Place," I told the driver. "Down in the Village. Make it snappy and I'll go heavy on the tip."

He made a swift U-turn in the middle of the block that flung me back into the corner, then speeded south on Park Avenue. He knew his business and it wasn't long before we turned into the comparatively quiet Stuyvesant Place, where April's Greenwich Village apartment was located. My heart beat joyfully. Yet underneath, was there a premonition of evil? Maybe I'm reading back into it something that wasn't there—not at that moment anyway. I don't know.

And it meant nothing special to me, when, as we lurched around the corner, I saw a big shiny black limousine pull away from the curb in front of us. It roared away, a big luxurious Isotta with drawn curtains, that must have cost a small fortune. Vehicles of that sort were rare in this neighborhood.

Yet how was I to dream that this particular one had any special significance for me? Did any mental shudder come to warn me, any spinal chill? Perhaps. But if it did, I mistook it for a thrill of happiness. My mind was too full of April, and of the joy I believed we were soon to have together.

My cab stopped with an abruptness that threw me forward and knocked my hat askew. I didn't mind. I gave the driver a five spot, told him to keep the change, flung the door open, dashed across the sidewalk and up the steps. I jabbed the bell button and waited.

There was no response. I could hear the bell ringing in April's second floor apartment. I thought perhaps April was having her bath and couldn't get to the buzzer just then. A delivery boy from the corner delicatessen came out, carrying an empty box. Evidently he had just made a delivery of groceries. I recognized him.

"Hello, Bob," I said.

"Hello, Mr. Carter," he answered—and his next words, usually spoken, were like the blow of a fist: "Looking for Miss Harris? I just saw her go out with a man."

"What!" I cried. "What man! Where!"

"Never saw him before," Bob answered. "Dressed like a million bucks, but all in black. Had a big car parked out in front, too, and a chauffeur in black livery."

"But his face, Bob?" I cried, worried and perplexed. "What did he look like?"

"Like the devil," he answered amazingly. "And I'm not cussing, Mr. Carter. It's just how he looked—like one of those pictures of Meph—Meph—"

"Mephistopheles," I broke in impatiently.

"Yeah, Mr. Carter. Black hair that came down to a point in front—eyebrows slanting upward—glittering black eyes. Sort of gave me the shivers when I saw him. I couldn't imagine where Miss Harris would be going with a guy like that."

I darted past him and bounded up the stairs. Perhaps he had been mistaken—had taken some other girl for April in the dimly lit hallway.

But the door of April's apartment stood wide open. I knew she never left it that way. I entered. The place was in disorder. Her new steamer trunk—a gift from me—was closed and locked. But her two bags stood open, only partly packed. I looked into the bath room. The shower curtain was wet and still dripping. The wet marks of April's small bare feet were on the bath mat. Her negligee hung over the chair.

APRIL had left! On the eve of our wedding! I was like a man

distraught, running hither and thither about the apartment,

peering here, peering there. Suddenly I stopped. My frightened

eyes had glimpsed a note lying in the middle of the coffee table,

held down by a tiny ash tray. It was addressed to me. Reading it,

my happy world crashed about me, my visions of joy splintered

into tragic grief:

Dear Tom:

By the time you read this I will be gone to where you will never see me again—gone with the man I really love. Perhaps I should have remained to face you and have it out. But on second thought, I decided that this would be the easier and kinder way.

Good-by and good luck.

April.

I was stunned—uncomprehending. I fell back upon the

studio couch. A pin stuck me, and I became dumbly aware that I

was sitting on a newly-pressed gown to which was attached a fresh

corsage of orchids—the orchids I had sent to April. The pin

that held them had pricked me. Savagely, I hurled it into a

corner. I spread the crumpled note on the coffee table and read

it once more—to convince myself I was not dreaming. Thank

God I did so!

April and I had taken secretarial courses, had both learned shorthand. I hadn't used mine for nearly three years, but the rigid training I had received in the business college had done its work well.

Now I suddenly recognized, attached to the very first word, the shorthand character for the sound "p." What could it mean? I looked at the next word and there was the character which indicated the sound "s." P.S. A message within a message! I drew an envelope from my pocket—the envelope which contained our marriage license—and rapidly transcribed the symbols on the back.

When I was done, I had the following ominous message which had been blended in terse shorthand characters with the original note:

Pasquale forcing me write this. Taking me away don't know where. Torturing me. Horrible threats. Wire noose around my neck. Suffering and deathly afraid, but thinking only of you dear. Find me quickly. His license number 126-8347 A.

His license number! The only clue. The swift picture flashed

through my mind—she, sitting at her writing desk by the

window—a kidnapper, resembling the Devil, strangling her

and dictating what she wrote—she, seeing the waiting car

outside, noting down the license number!

And Pasquale! Pasquale could only be one man! Pasquale Sarasini! My most persistent rival during my schoolboy romance with April! The description of the delivery boy fitted him perfectly. He had taken a bookkeeping course, hence had not learned shorthand. I had almost forgotten him in the intervening years—had even forgotten the malignant threats he had mouthed when he came upon April and me suddenly, one day, in the empty classroom after school, and saw us in each other's arms.

April had broken with him completely the day before. He had seemed to take it calmly, hiding his chagrin and disappointment. But that afternoon, seeing the proof that she loved another, he had said through hate-whitened lips:

"I'll see that you suffer the tortures of the damned for this, April."

I had not seen Pasquale after that, nor had April, for nearly four years. But then we heard rumors. He was delving into the occult, mystifying scientists. His picture began to appear in American and British papers. His fame spread to continental Europe. At first he acted as a materialization medium, giving private sťances. Later he went on the stage, producing illusions.

THEY were not illusions—I know that now. He became

famous, rich, sought after. He was billed as "Sarasini the

Great." He got motion picture contracts at fabulous prices.

Wealthy people patronized his private sťances. They came away

with amazing tales, not only of their loved ones materialized

before their eyes, but of strange monsters and creatures like

those depicted in ancient tombs and writings.

There was the cat-headed Bast of the ancient Egyptians, which talked to them in a mewing voice. There was the ibis-headed Thoth, scribe of the gods—hawk-headed Horus, son of Isis and Osiris. There was the Lamia of Greek legend, a serpent that became a woman and once more turned into a serpent before the eyes of its auditors, a seven-headed hydra, a Gorgon with snaky locks.

During the sťances, Sarasini played an instrument of his own invention—a sort of combination piano and organ. The music was weird and uncanny, of his own composition, and he stated that it was necessary to the materialization of his creatures, which he claimed really existed in another plane. Also, there were two tall poles, surmounted by rectangular caps. It was said that these were somehow connected with the instrument, and that materializations took place only between these poles, as if some electrical force were involved, the force traveling between them as a static spark leaps the gap between the knob of a Leyden jar and a conductor brought within range.

Sarasini made enemies in his profession. One spiritualistic medium and profound student of the occult, accused him publicly of being in league with Satan. And Sarasini had coolly admitted it!

In another generation he would have been burned at the stake; the horrors that he perpetrated would have been blotted out forever. But in this so-called "enlightened" generation, when all such things are scoffed at, it only created a sensation in the press—and was duly tagged by astute columnists as a publicity stunt. My God! How far it was from a mere publicity stunt I have reason to know!

Then, at the height of his career Sarasini retired from public life, disappeared from the sight and ken of men. A year passed.

And now—and now he had suddenly to claim the vengeance he had sworn more than five years before!

All this flashed through my mind as I frantically dialed the police. Swiftly, I requested the desk sergeant to give me the name and address attached to the license number April had written down. I told him who I was—the manager of the Brinkman Express Company. We often gave employment to ex-policemen. The sergeant snapped that he would get me the information.

I didn't tell him what had happened because I felt that this was a matter requiring discreet attention rather than the brusque tactics of the police. I think I was frightened at the thought of April disappearing completely, mysteriously, should the law intervene. It seemed an age before the phone rang.

The sergeant called back a moment later—it seemed ages to me. On the back of the envelope containing our marriage license I jotted down the name he gave me—Pablo Simister. Pasquale Sarasini hadn't changed his initials, at any rate, even if he had changed his name. The address was the penthouse at an uptown number on Riverside Drive near Washington Park.

Jamming my hat down on my head, I dashed downstairs and sprinted to the nearest subway kiosk, choosing that mode of transportation as the quickest. Two minutes later I was hurtling northward on the express. It reached One Hundred and Eighty-first Street Station at last.

I got off, dashed through the turnstile and up the steps, then over to Riverside Drive. I reached the apartment building, entered the foyer.

THERE were four self-service elevators. The lights showed two

were in service. I entered one of the others, closed the door,

pressed the top button. A few moments later the cage stopped, the

door opened automatically. I stepped out. A stairway led upward

at my left.

I climbed it, stood on the landing, and manipulated the brass knocker. I noticed that it was shaped like the head of a Medusa, with snaky locks. The door, I observed, was of steel, but painted and paneled to resemble wood.

I heard no sound on the other side. I knocked again. Before I could release the Medusa-headed knocker, the door swung silently open. Behind it stood a man in black butler's livery—black trimmed with silver. His face was completely concealed by a black mask—a domino with a sort of veil that hung down beneath it. His head was covered by a black hood. Startled though I was, I stepped forward so as to be able to block the door with my foot and knee, and said with simulated jocularity:

"Ah! A masquerade, I see. Is Mr. Simister in? I'm an old schoolmate of his—from out of town. Thought I'd drop in and say 'hello'."

"I'm sorry, sir; Mr. Simister is not at home," he replied politely.

"If you're expecting him soon I might step in and wait."

"I'm afraid I couldn't permit that, sir," he replied. "You see the master is exceedingly busy today, and I have orders to admit no one. Perhaps tomorrow—"

He started to close the door, but I blocked it with my foot. I did more; I uncorked a left for the spot beneath that black veil where I judged the point of his jaw would be. As ill luck would have it his jaw was shorter than I thought. My knuckles only grazed it. Then, before I could recover my balance, I felt my wrist caught in a grip of steel.

"I wouldn't do that, sir," he said, calmly. "You might hurt yourself."

Desperately I jerked my wrist toward me, and as the butler was gripping it tightly, he came with it. His other hand was still on the doorknob. Before he could get it up I gave him a right uppercut. His head snapped back, and he let go of my wrist. I drove a left and right to his solar plexus, doubled him up, then a left hook to the jaw that spun him around and broke his hold on the door. He fell on his face.

Softly I closed the door, then bent over him cautiously. He might be shamming. I stripped the hood and mask from his head. He appeared to be a Latin. He was out cold—the eyes turned upward and inward.

I looked around quickly. I was in a long hallway draped to the ceiling with black velvet hangings, like a sound-proofed radio room. Not a door was visible except the one through which I had just come. And that, I saw, could be rendered invisible, also, by two drapes now drawn up on either side and caught with silver cords.

There were places where the hangings overlapped. I went to the first of these, drawing it back, saw a door, which opened inward. It was a cloak room. Swiftly, I dragged the unconscious butler inside, and as swiftly divested him of his livery. Then I removed my own clothing and put on his. I bound him with the stout silver cords which hung on either side of the doorway, and which could be used, when required, for holding back the drapes. Then I gagged and locked him in.

I found no other doors until I reached the end of the hallway. Here, double doors opened into a spacious, modernistically furnished living room. The walls, like those of the hallway, were completely concealed by black velvet hangings.

I was about to go back and take my post before the door, when the drapes at the opposite side of the room suddenly parted, and a man stepped through.

I recognized him, instantly. He was in evening clothes, and had not changed greatly since I had last seen him. There was still that diabolical expression, those uptilted brows and glittering black eyes.

"Did you get rid of our caller, Dominick?" he asked.

"Yes, sir," I replied, mimicking the voice of the butler, while my heart pounded. "He's gone, sir."

He raised a quizzical eyebrow. "Mix my cocktail," he ordered.

I had previously noted the liquor cabinet standing against the drapes at my left—an ornate thing of ebony and silver. I recalled that his favorite cocktail during our school days had been a Martini, with an extra dash of orange bitters, but without the olive. Strange to say, he, a Latin, detested olives, and could not even stand food cooked in olive oil. I mixed the drink.

I thought I was getting away with it, but—

"Get 'em up, Carter," his voice said behind me, and I felt something hard prodding my back.

"Clever," he drawled. "Damn' clever. You almost got away with it. But it so happens that since last year, I've been allergic to gin. Get your hands together over your head."

Perforce I obeyed, and he snapped on a pair of handcuffs. Then he stripped off the hood and mask and ordered me to turn around.

"You haven't changed much, Carter," he said. "Still built like a battleship, with a mug like the Great Stone Face. I don't see how the devil you traced me here so quickly. But it doesn't matter, now. All that matters is that you're here. Sit down."

I seated myself in a black-upholstered chair. He sat down on the davenport, and slipped the automatic back into his shoulder holster.

"You've come for April, of course," he said.

"Clever of you to guess it," I answered him.

"What have you done with Dominick? Did you kill him?"

"Knocked him cold and tied him up."

"So? Well, he can stay that way for awhile. Perhaps it will teach him not to be so careless again. I suppose you realize that you're in a tight spot—that I can kill you and get away with it. No one will ever trace you here."

"That's where you're wrong," I lied as calmly as I could. "The police not only know I'm here. They actually gave me your address. If you'll release April at once—"

"Just a moment, Carter. Not so fast." He raised a slim white hand. "April has gone to a place where even I can't bring her back—permanently. I can only bring her— temporarily—from the different plane in which she now resides."

I HALF rose from my chair, straining at my shackles, longing

to reach his throat. "You mean you've killed her?"

He jerked the automatic from the holster. "Back into your seat, Carter. That's better." He laid the gun on the table top.

"No, I haven't killed her. I have transformed her. She is in a different and superior plane of existence. I have powers of which you do not dream, Carter. People have accused me of being in league with the devil. It is true.

"Aye. Satan is my master. He has made me what I am. I was baptized—but not by a priest of the church. When the time came for my baptism, both of my parents were ill—a flu epidemic. My nurse, an Arab girl, was a Yezidi—a secret worshiper of Satan. They call him Malik Taus in their language, because they fear to pronounce his real name—Shaitan.

"She took me to her own priest—deceived my parents—and I was baptized into the cult of the Yezidis. Later. I sat at the feet of their priest—Shaykh Ibrahim—drank in his teachings, absorbed his knowledge, mastered the esoteric truths that the worshipers themselves do not know, truth that is reserved for adepts alone.

"When I had learned all that the Shaykh could teach me, I went on by myself. Delved into the ancient writings of all peoples—athirst for greater knowledge. After many trials and failures, I learned how to summon the Master himself. He came, and made a pact with me—dictating the terms, to which I acceded. My soul in exchange for a temporal power such as no man has ever before enjoyed. He summoned seven of his creatures to be my servants—to work my will.

"Enough of that. April is here in this room—now—but you cannot see her. Perhaps you can see her a little if she makes a supreme effort."

He turned his glittering eyes to a point beside my chair. "April, show yourself," he commanded.

Suddenly my left side felt cold—as if all of the heat had been drawn out of it. There was a cold breeze blowing against my face, as from an underground burial vault suddenly opened up. And there came to my nostrils a dank, musty, reptilian odor—incredibly foul.

Horror of horrors! A tiny whirlpool of gray mist began forming on the floor before my eyes. It enlarged until it was five feet tall. Streamers of mist, like arms, extended from it. Two black orifices formed in the top, not solid, but like the hollow eye- sockets of a skull.

"The great Sarasini," I mocked, even though mystic fingers of fear clutched my heart, "pulling his magic tricks! Do you mean to tell me that this apparition is April? Come again."

No, I did not believe my words. I knew there was some alien and unutterably evil presence in the room. Not April. No, not April. I could not conceive of April becoming such a creature. But it was something alive, and sinister, and incredibly loathsome.

As I spoke, the apparition suddenly disappeared. The cold breeze stopped. Once more my left side was at normal temperature. But the nauseous odor was still in my nostrils—I could still feel the invisible presence of the thing from which it had emanated.

"So you mock me—scoff at my powers," Sarasini cried. "Wait. I can't bring her back completely here, but I can with the proper equipment. You wait here. I'll show you April—let you talk with her—for only a short time. Don't try any more tricks. You are absolutely helpless—in my power."

He rose and returned the automatic to its holster. Then he said: "Watch him, my beauties," and turning on his heel, parted the black drapes and disappeared.

His last order was apparently addressed to empty air. But the air was not empty! I could feel sinister presences around me, pressing against me, watching me with hollow, cavernous eyes.

I tried to tell myself that I was the victim of a delusion. Reason came to my aid. Sarasini had forgotten one thing—my profession. Every employee and executive of the Brinkman Express Company had a pistol permit, and carried a gun when on duty. I'd forgotten to take mine off when I left the office. It was still in my hip pocket, supported by a leather holster attached to my belt, and not noticeable under the butler's coat. I moved my manacled hands around, and found that I could easily reach it with my right hand.

I wasn't yet ready to draw, however. Instead, I stood up. Then it happened. I was about to walk silently toward the opening through which the magician had disappeared, when a misty spiral shape suddenly materialized on each side of me. Again I felt the cold. In an instant, my muscles grew numb—all the strength and heat oozed out of them as though sucked. I slumped stiffly back into the chair. Instantly, the two wraiths dissolved and disappeared. Once more I grew warm, got back the use of my muscles.

I remembered Sarasini's seemingly directionless command just before he had left the room—"Watch him, my beauties." These, then, were his "beauties"—these horrid wraiths, these shapes of writhing mist, that had sucked the strength from me and then given it back, that had frozen my blood and then allowed it to grow warm again. Like the Gorgons of Greek mythology, which had supposedly had the power to turn men to stone, so these shapes had given me the promise and the threat of the same power!

Could it be? Could it be that the terrible sisters, Stheno, Euryale and Medusa had actually existed? Could it be that I was now held prisoner by similar beings?

The black drapes in front of me parted once more. Sarasini appeared. Gone were his immaculate evening clothes. In their place he wore the tight-fitting scarlet costume of Mephistopheles. The costume suited his diabolical features far better than dinner clothes.

"Release him now, my pets," he said, again apparently speaking to empty air. Then he addressed me. "Come ahead, Carter."

He held back the drape while I walked through into the next room, my hands manacled before me.

I had seen pictures of the apparatus he used on the stage, and it was now duplicated in this room, which was a small auditorium with about two dozen chairs that faced the stage.

"Take a seat in the front row, Carter," he ordered.

I did so, and he walked to the keyboard of the strange instrument he had used so often in his public performances.

"Before I begin," he said, "I'll make a deal with you. You are completely in my power, yet I have no particular reason for killing you—yet. You hate me, but so do many others I have spared. You have never wronged me. April did that. She is the one I hate, and she is paying the penalty. If I convince you that April has passed to another plane where neither you nor any other human being can reach her, will you agree to go away peaceably, and say nothing to anyone about what you have seen?"

"I'll make no compact with you," I answered.

"I'll convince you anyhow," he said coldly. "Then, perhaps, you'll change your mind. If you don't—it will be just too bad for you."

His hands pressed the keys. A peculiar wailing sound arose. It could not be called music. Not harmony, not melody, but a hideous cacophony of sound that grated on my ears, caused icy shivers to run up and down my spine, and set my teeth on edge.

It grew louder, rising and falling in waves of horrific discord. At the same time I suddenly became aware of another sound—a noise like the crackling of an electric spark between the two upright posts with their strange, rectangular caps.

Once again I saw a misty spiral forming. But this time it swiftly took human form. A halo of light gradually grew brighter about the head as it gained solidity. Within this halo I saw the formation of writhing tentacles.

The human figure became a lovely girl, scantily clad, holding a sword in her hand.

I cried out. She had the form and features of April! But her hair! Good God, her hair! A writhing mass of hissing snakes, that snapped and fought among themselves, coiling and uncoiling and darting their forked tongues from their scaly mouths!

The wailing chorus died down to a soft undertone.

The materialized, Gorgon-headed creature spoke. The voice was the voice of April!

"Go back, Tom," it said. "Go back and forget. You were foolish to follow me here. You should have heeded my letter. I am now an entirely different entity, living in a different plane. The old April whom you knew is gone—gone forever— gone beyond your reach."

The head shook, and the serpents that were the hair of it, increased their hissing and writhing.

"Would you want to take me in your arms, now, with these?" the voice asked, and her free hand pointed to the reptilian crown.

"April! April!" I cried. "I'd take you in my arms in spite of hell!"

"Sit down, you fool," said Sarasini. "Her touch, now, would mean instant death to you—a horrible, agonizing death. She is beyond your reach—forever. Show him, April—show him that you are no longer human—that you have powers that are superhuman."

Thrice the girl whirled the sword in a shimmering arc above her head. Then, with the fourth swing she brought it lower in a back-handed motion. The keen blade passed beneath her chin, severing her head from her body! With her other hand she caught the toppling head and held it aloft!

The snakes continued to writhe and hiss in the aura of light surrounding the severed head. There was no blood on the sword blade, or the cut edges of the neck. The closed eyes opened. The lips spoke.

"You see, Tom? Could any human being do this and live? Are you satisfied?"

My words, my heart, strangled in my throat. "Your message—" I choked.

"I meant it—every word," replied that incredible head. "I mean it now when I say: Leave me. Forget that I ever existed."

Then I was to learn that love could be stronger than death, than horror. My love for the April that was, fought with my horror at the April I saw. I wanted her, the old April. This horrible materialization of some hell-spawned creature that was not the girl I loved, was, and forever would be, beyond my ken. But the old April seemed to send a call into my heart—the April who had written me that secret appeal of which this creature was unaware. I whipped my gun from my pocket at last, and stood up, aiming it at Sarasini's heart.

"Stick 'em up, or by God I'll drill you," I cried.

He raised his hands from the keys of the instrument as I advanced to a place beside the apparition. The wailing ceased. Then—horror of horrors—the thing beside me hurled its severed head, with its mass of squirming, hissing snakes, full in my face. I lurched back, flinging the revolting thing from me. It had a slimy reptilian feel and smell.

As it struck the floor, the sword in the hand of the headless figure swept down, striking the gun from my hand. Sarasini whipped his automatic from his shoulder holster and fired, just as I stooped to retrieve my gun. His bullet passed over my back. Before he could fire again I shot without aiming—merely elevating the muzzle of the gun with the butt resting on the floor.

I shot to kill, but miscalculated. The bullet caught him in the groin. He doubled up with a shriek of anguish, and fell on his face—the automatic clattering from his hand.

I retrieved it. As I stood erect I saw the Gorgon apparition dissolving—turning back into a mist. The head was going through the same process. Its writhing, snaky locks became tentacles of gray mist. Then these too were withdrawn into a cloud, which moved toward the platform and joined the larger cloud that had been the body. Quickly, the whole dissolved to nothingness.

Sarasini was groaning weakly on the floor, his knees drawn up nearly to his chin, his blood staining the crimson suit a darker red as it welled from the bullet wound.

"At him, my pets," he moaned. "Freeze him. Suck the life from him."

Funnels of mist swirled all about me. There were six of them, clutching at me with their wraith-like tentacles, glaring at me with their hollow eyes. I felt as if I had suddenly been deprived of all bodily heat and strength. Frantically 11 fought them—fought them with every nerve and muscle in my body.

Gradually, the wraiths dissolved. The warmth returned to my body. Suddenly I knew! By wounding their master I had weakened their power!

Sarasini was groaning and cursing. There was froth on his lips. The fire was dying into embers in his eyes. Suddenly they widened with fear. And as suddenly, I saw why. Six funnel-shaped wraiths descended upon him—the apex of each touched his body.

"Back, my beauties," he groaned. "Away from me, my pets. You are attacking me—your friend and master."

But the things fastened themselves to his body like anemones growing on a submarine stone. His groans and struggles lessened. He shuddered, stiffened, lay still—his eyes began to glaze. But still the wraiths clung to him, each a good six feet tall, and all undulating lightly in the air as undersea plants move in the water.

Sarasini was on the point of death—I could see that. The life force was being sucked from him by these creatures of his that had turned on their master. But suddenly he rallied, mustered his strength. And it was now that he turned to his Master for succor.

"Shaitan! Satanas! Beelzebub! Great Lord of Darkness! Emperor of Evil! They have turned on me! I die! Save me, Master!"

I heard at that instant the most hideous sound that has ever fallen on human ears. I could not tell whence it came—it seemed to echo from all points of the compass, to come from everywhere and yet from nowhere in the room—it seemed to my ears to fill the whole world, inhuman, gloating cacodemoniacal cachinnations that resembled a cosmic mirthless laughter.

At that sound hope faded from the glazing eyes of Sarasini. Yet it flickered faintly once more, as he turned his head desperately to me.

"Carter! Help me! Drive them off! If you do, I'll help you to rescue April! I swear it, Carter! My Master has deserted me! He is greedy to claim my soul—the forfeit I promised him—"

I reacted automatically to that cry for help. I emptied my gun into the tenebrous obscenities that were leeching his life away.

"Not that, Carter!" he cried. "Bullets cannot harm them! They are immune to mortal weapons! You saw what one did with the sword. They fear only goodness, and the symbols of goodness—the sacred symbols of the religions that worship God, the fountainhead of all good. The great seal of Solomon Baalshem, Lord of the Name; the six-pointed star inscribed with the Shem Hamphorash, Ineffable Name; the Cross—the crucifix! It is the simplest. Make a crucifix—quickly—of anything!"

I took the pencil from my pocket, broke it into two unequal pieces, lashed it in the form of a crucifix with a strip torn from my handkerchief.

"Touch my forehead with the point of the cross," Sarasini gasped. "Say: 'Anathema maranatha'."

I did as he bade me. The six undulating things that clung to him disappeared before my eyes.

I mopped Sarasini's face with my torn handkerchief.

"Brandy, Carter," he panted. "I need strength—to carry out my promise to you—before I redeem my pledge to Satan."

I ran into the other room, brought back the brandy bottle and glass. Then I poured a stiff three fingers and supported his head while he drank it.

He sighed, and the color came back to his face, the glaze receded from his eyes.

"April is in the next room," he said, "in a coma—possessed by one of my seven Elementals. That's why there were only six in here. Take the cross and the brandy—you'll need both—and do with her as you did with me. Here, take my keys. First, let me unlock your handcuffs."

As the handcuffs fell from my wrists, he selected the key to the door, and pressed it into my hand.

God be thanked, I found April, half reclining on a chaise longue in a luxuriously furnished bedroom. She was in what I at first took to be a drugged sleep. But her eyes were staring beneath her half closed lids.

Lightly I tapped her on the forehead with the crucifix and repeated the words: "Anathema maranatha."

A gray, funnel-shaped wisp started up from the place I had touched. With incredible rapidity it grew, elongated. Then it detached itself, and, whirling away like a miniature waterspout, disappeared beyond the black curtains in the doorway.

And dear April opened her eyes, smiled up at me under the fringe of her long lashes. She held up her arms, and as I bent over her they went around my neck. Our lips met—and clung.

Presently, I asked: "Can you walk, dear, or shall I carry you?"

"I can walk—in a minute or so," she replied.

I poured her a sip of brandy. Strengthened, she went with me into the next room.

Sarasini was propped up on one elbow. He asked for another drink of brandy and I poured it for him. He took it at a gulp.

"My minutes are numbered," he said in a low, sad voice. "When my life has ebbed away my Master will claim the soul which I have sold to him. You wronged me once, April, and I have hated you for it—hated you through the years. But you have suffered and paid—and the debt is wiped out.

"As death approaches, a new understanding comes to me. I have a new, and greater hate. My Elementals, which derived their strength from me and from the machine which I created for them under the direction of my Master, turned against me.

"I suspected that some day they might do so. I controlled them, yet I could feel that they were watching and waiting for the chance to turn on me. I was like an animal trainer in a cage of wild beasts, not knowing when or how I would be attacked."

He paused, asked for a cigarette. I lighted one for him.

"They brought me power and wealth," he went on, "and now they have brought me death. I could have survived your bullet, had it not been for their attack on me. I hate them. With your help, I'll break their power forever—the power I gave them.

"I have the knowledge—you the strength. Look in the room behind the instrument board—then do as I bid you. There you will find seven girls, connected with the instrument. I abducted them, one by one, hypnotized them, and turned them into mediums.

"Their bodies are the dwellings of my Elementals—their earthly homes. And they are not only the source of their power, but supply the mediumistic force which—amplified by my machine—make it possible for one Elemental at a time to materialize solidly between its poles," in almost any desired form. One of their favorite forms is one of the Gorgon, as you have seen.

"My time is short and I am going fast. Release those girls from the possession of the Elementals as you released April. They have suffered, and are suffering. I had intended to put April in the place of one who will soon die. But, through the power and mercy of the symbol in your hand, they will forget, even as she has forgotten, the agonies they now suffer. Disconnect them from the machine. Do this quickly. Then return to me."

April and I went into the room behind the fiendish instrument that was the product of Sarasini's perverted and devil-directed brain. There we saw seven pedestals, and on each a beautiful young girl, covered only with a scarlet, diaphanous drape. A leather band passed around the head of each, clamping an electrode to each temple. These electrodes were connected by wires to the instrument on which Sarasini had played his ugly discords.

"Give me the crucifix," said April.

I handed it to her, and while she touched, one by one, the possessed girls, I removed the electrodes from their heads.

Leaving April to care for them, I returned to the instrument room. Sarasini was now lying on his back, breathing stertorously. The death rattle was in his throat.

"Smash it," he whispered hoarsely. "Destroy the machine! Break it to bits!"

I picked up the stool and smashed that hell-spawned instrument until it was unrecognizable. I ripped all of the wires loose, and broke the connection between the smashed instrument and the two poles.

THERE isn't much more to tell.

I was not accused of murder because the evidence showed I had come to rescue April, and had been attacked. Dominick got a prison term for kidnaping, as an accessory. And we were forced to postpone our honeymoon until after his trial.

Then we decided not to go to Europe as we had originally intended. Instead, we took a cottage in Maine. Great stuff, that Maine air. Now there are two Aprils in my home. I'm back on the job, working like a beaver to save enough for the college education of April the Second.

But I have not forgotten the writhing shapes, the charnel reptilian smells. I shall carry the memory of them to my grave.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.