RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1936,

with "Revenge of the Robot"

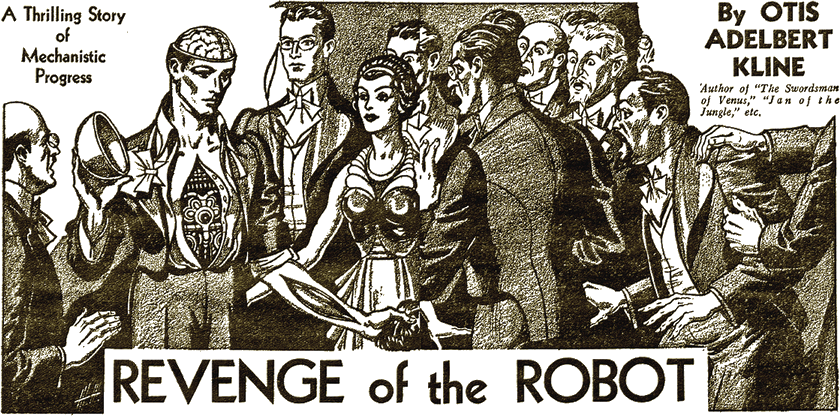

He opened his shirt front, slit his chest and revealed mechanism.

The Age of Miracles produces an amazing suicide and

a triumphant return from death. A million dollar prize is

offered—and won—for the most perfect automation. —Ed.

THE dessert had just been served at the annual banquet of the International Society of Robot Fabricators, where five thousand members of the society and their guests sat at a huge V-shaped table in the auditorium of the American Institute of Science on Chicago's lake front.

Orville Matthews, President of the United States, and himself a scientist of note, held a goblet close to the microphone before him, and tapped it gently with his spoon. The chatter of voices was instantly hushed as the sound was amplified in the vast auditorium.

The President stood up and shook back his mane of snow-white hair.

"Most of you," he said, "have some inkling of the announcement I am about to make, since the deliberations of our legislative body are not carried on in secret. You know that Congress voted an appropriation of one million dollars to be offered as a prize for the most outstanding achievement in science during the year 1999, the prize to be paid on January 1st, 2000, and the nature of the achievement to be determined by the President and his Cabinet.

"We have made vast strides in scientific achievement during the past fifty years. For instance, my good friend, Herr Doktor Ludwig Meyer, came here from Berlin in less than an hour in his stratosphere rocket plane. My friend Sir Chauncey Newcomb of London made it here in less than half an hour by patronizing the Transatlantic Vacuum Tunnel System.

"We have-many other splendid conveniences and inventions which, fifty years ago, were only dreamed of, but which to us of today are commonplace. However, there is one thing which man has not yet invented—a machine that will think for itself—a robot that will not merely respond to the orders of its controller, but will, in addition, reason inductively and deductively—a machine that will think analytically, creatively, and independently.

"The robot that wins this great prize must be constructed in the semblance of a human, being. It must not be subject to any outside control but, as I have said, must do its own thinking and direct its own actions. In case such a robot is not constructed, the prize money will be returned to the Treasury of the United States. If more than one such robot is constructed, the one which most perfectly simulates man physically, and which shows the strongest and most desirable mental characteristics, will win the prize.

"The competition is open to people of all nations, and I trust that every robot inventor will decide to compete. You have one year in which to perfect such a robot. Permit me to wish you luck."

The thunderous applause which greeted the President's announcement was followed by a thousand heated arguments. Many contended that such a robot was an impossibility. Others felt that it might be constructed, but a year was a very short time in which to perfect it.

There was one scientist who did not join in the discussion. Albert Bradshaw had devoted twenty of the thirty years of his life to intensive laboratory work, with the result that he had contracted pulmonary tuberculosis. In spite of the slow wastage of the disease, he was strikingly handsome—the hectic flush rather heightening the youthful appearance of his face.

His frank blue eyes were filled with devotion as he looked down into the sparkling black ones of his vivacious dinner companion and nurse, Yvonne D'Arcy. Tonight her appearance was far from professional, with her glossy black hair done in the latest mode, and her smart evening gown that tastefully set off her youthful charms.

"Enjoying it?" he asked her.

"So much," she smiled. "But we must go now. The exertion and excitement aren't good for you."

"All right," he answered agreeably. "Let's go."

Many admiring pairs of eyes followed the handsome couple as they made their way toward the checkroom. Among these were a pair of near-sighted grey eyes, peering through a thick-lensed pince-nez. Their look of admiration, however, was for the girl alone. For the man they had only an envious, malignant glare. Hugh Grimes, millionaire inventor of the Grimes Radio-Controlled Robots, which were employed by millions both in the United States and abroad, adjusted his pince-nez, stroked his neatly trimmed Van Dyke, and replied abstractedly to a statement made by the beefy, pendant-jowled Dr. Ludwig Meyer of Berlin, who sat at his right. Then, excusing himself, he rose and marched in the wake of the young couple who had just left their table.

There was a deadly glitter in his weak, watery eyes as he contemplated the back of the young man before him. As if to reassure himself, he dipped thumb and forefinger into his vest pocket and caressed a small, globular object that nestled there.

ALBERT BRADSHAW returned to his home weak and exhausted; yet he insisted on going into his laboratory to resume his work on the two figures, one in the semblance of a man, and the other a woman, which had occupied his working hours during the past ten years.

He bent over the male figure before him, and removed the wig and skull-case, revealing an intricate maze of delicate wheels, springs, bulbs and tubes. Then he went to the spotless white sink, and, reaching above it, took down from the shelf a bottle marked "Solution X-4, 337." Unstopping the bottle, he poured a small quantity of the solution into a test tube. From an airtight container he extracted a thin strip of blue litmus paper.

Suddenly there was a crash and a tinkle of glass from the window across the room directly behind him, followed by the plop of a small globe which shattered against the enameled back of the sink.

Before he had time to hold his breath, Bradshaw inhaled a whiff of the iridescent greenish gas which mushroomed out from the shattered globe. A searing pain shot through his nasal passages, throat and lungs. He instantly expelled his breath, then held it, and whirled in time to catch sight of a bearded face twisted in a malignant grin. A pair of nearsighted eyes glittered at him through a pince-nez. Then the face disappeared.

Suddenly Bradshaw noted that the litmus in his hand had turned pink. Dropping it, he reached up, seized a bottle marked "Ammonia" and smashed it in the sink. Then, with his seared, disease-weakened lungs nearly bursting with the agony of holding his breath, he dashed out of the laboratory.

In the hallway he collided with Yvonne. He collapsed in her aims a moment later as she sought to steady him.

"Acid gas of some sort," he groaned. "Tried to neutralize it with ammonia."

Quickly she brought a cushion from the davenport propped it under his head.

"The doctor should be here any minute on his regular visit," she said, "but I'll call him, anyway."

She hurried to the radiovisiphone, and pressed a button. When the disc was illuminated she twirled a dial in a combination of four letters and six numbers.

The rugged, homely features of a young man appeared in the disc.

"What's the matter, Yvonne?" he asked? "Patient worse?"

"He's just inhaled poison gas," she gasped. "Do hurry, Doctor."

"Be right over," he replied, and the disc once more went dark.

Through the window behind the disc she saw two men loading something into the back of a helicopter limousine. A third, whom she recognized as Hugh Grimes, climbed in behind the controls, and the craft roared upward.

A moment later the whir of the physician's helicopter coupe was audible outside the window. Then young Dr. Frank Gunning came dashing up the steps and through the door.

Bradshaw was breathing convulsively, his face twisted in agony. There was a bluish tinge around his mouth.

"Cyanosis," said the young doctor, after a brief examination. "We'll have to administer oxygen and a stimulant."

He picked up the patient and carried him to his bedroom. For more than two hours he and the nurse worked over Bradshaw with the portable oxygen set. Then the blue area around the mouth began to disappear.

A sedative was given, and the tortured patient slept while the doctor made a complete examination with his portable Super X-Ray fluoroscope.

Yvonne tiptoed out behind the doctor when he left, and stopped him in the hallway.

"Is there any chance for him?" she asked steadily.

"It's tough, Yvonne." His voice was brusque. "Al has about six months to live. That gas burned most of the healthy lung tissue that remains to him."

Yvonne caught her breath, and turned away to hide the tears that flooded her great dark eyes. The doctor pretended not to notice.

"By the way," he said, "how did he happen to breathe that poison gas? Was it a laboratory accident?"

"Worse," she replied. "It—it was premeditated murder. Hugh Grimes' work. He came here often, discussing his theories with Albert. Albert foolishly showed him his new robots. I think he was afraid Albert's creations might replace his own—also, that they might win the prize."

"Professional jealousy, eh?"

The voice of Albert Bradshaw broke into their conversation with unexpected suddenness. They whirled, and saw him standing in the doorway behind them, supporting himself against the jamb.

"Albert! You must get back to bed at once," admonished Yvonne.

"Not until I've had a look in the laboratory," replied Bradshaw.

"Take it easy, old man. I'll carry you." The doctor moved quickly to his side.

"No, damn it! I'm not done in yet. I'll walk."

Bradshaw gritted his teeth, and, supported by the nurse on one side and the doctor on the other, made his unsteady way down the hall to the laboratory. Cautiously Gunning opened the door and sniffed. There was a faint odor of ammonia—nothing more.

"I guess it's diluted enough so we can go in," he said. "Must be a window open."

There was. Two French windows, one with a shattered pane, were wide open. It had been easy for the marauder to reach in from the terrace and unfasten the catch.

Bradshaw pointed a shaking hand toward the center of the room. "Just as I suspected," he cried. "The robots are gone! And look there at my molds!"

The two elaborately constructed molds which he had used over and over in casting experimental male and female figures were smashed beyond repair.

Bradshaw sagged weakly. "Help me back to bed," he groaned." His eyes burned feverishly. "That devil has set me back temporarily, but he hasn't beaten me yet."

Once they had him back in bed, the doctor said: "This is a case for the police. We'll prefer charges of attempted murder and robbery against Grimes."

"We'll do nothing of the sort," Bradshaw .told him. "I don't want either of you to say a word about this—not until I tell you to. I'll beat Grimes in my own way. All I need is to rest and gather a little strength. Now, Doc, give me a sedative and get the hell out of here."

AFTER two weeks of careful nursing by Yvonne, supplemented by daily calls from Dr. Gunning, Albert Bradshaw went back to his laboratory.

"Molds!" he told Yvonne. "I must have new ones, immediately. It will mean days lost—weeks—no, wait. I have a better plan."

"What is that?"

"You and I will do very well for models. All we need is some plaster of Paris and vaseline. The old cases can easily be repaired. I'll make a mold from your body, and you make one from mine."

"Splendid!" she answered. "That will be a great time-saver."

They made the molds that day, and on the following day Bradshaw went feverishly to work. In the weeks that followed, he was often interrupted by prolonged coughing spells, most of which ended in hemorrhages, but he carried resolutely on.

Five months elapsed before he had the bodies ready. He then started work on the heads; and, in the midst of this work, collapsed.

Yvonne immediately called Dr. Gunning, and the physician came in a hurry. He found his patient unconscious, and after making an examination shook his head dubiously.

"If he gets through another twenty-four hours, I'll be amazed," he said. "Al is through. If it hadn't been for that gas, he might have got through to see his robots tested. As it is—" Carefully he prepared his hypodermic syringe, while Yvonne bared and sterilized an emaciated arm. Then he shot the needle home. Presently a touch of color came to the white cheeks, and the breathing became more regular. Bradshaw's eyes opened.

"Doc," he said, "you practice at the Emergency Hospital. Do you suppose you could get me two people—a man and a woman—" He was interrupted by a violent fit of coughing, and Yvonne gently wiped a trickle of red from the corner of his mouth.

"Al, I hate to tell you this," the doctor said gently, "but you're about through. Hugh Grimes is your murderer—"

With a sudden surge of strength the sick man sat up. "I have a plan to be revenged on Grimes. You two can help me. You must!"

"What is It, dear?" Yvonne asked. Bradshaw sank back exhausted upon the pillow. When he spoke again, his voice was so weak that it was almost inaudible. The two people he held most dear, Yvonne, his beloved, and Gunning, his friend, bent low that they might catch his dying message.

HUGH GRIMES rose late the next morning. After his bath and breakfast he twirled the dial of the radiovisiphone beside him. It was time for the morning news broadcast of the International Newscasters.

The announcer appeared on the disc, holding a manuscript.

"Albert Bradshaw, known the world over for his marvelous inventions, passed on last night. His death was the culmination of a long, brave battle against pulmonary tuberculosis."

Grimes smiled. "Too bad," he told his valet. "Poor chap has had a tough time of it. And yet, it's an ill wind that blows nobody good. It will mean just one less major competitor in the robot field."

"Yes, sir. Quite so, sir," the valet replied. "All finished, sir."

"Good! I'll go now and see how my robots are coming on."

He spent the next few hours in his laboratory. There were two robots there, a male and a female figure—the robots he had stolen from Bradshaw's laboratory, and changed somewhat to disguise their identity. In the afternoon he ordered an expensive wreath sent to the home of Bradshaw. The following day he attended the funeral, viewed Bradshaw's cold remains in the flower-banked casket, and extended his condolences to relatives, close friends, and the heart-broken Yvonne.

Time passed very slowly for Hugh Grimes, but eventually the great day arrived—the day of the contest.

Again five thousand people were seated at a V-shaped table in the auditorium of the Institute of Arts and Sciences. And again President Matthews presided. A space had been cleared in the center of the V, so that all might view the antics of the robots.

Grimes sat across the table from Yvonne D'Arcy. She was radiantly beautiful in her dinner gown of black trimmed with silver. At her left was the burly young doctor, looking just a bit uncomfortable in his dinner clothes.

Now the President was calling the meeting to order. The hum of conversation ceased. Lights were dimmed, and a spotlight cast a huge white circle on the cleared space between the tables.

Le Blanc, the French inventor, was the first to put his robot through its paces. It made a speech, did staggering sums in arithmetic without paper or pencil, and even wrote its name. It read passages from a French novel, sang and wrote a number of sentences dictated by its inventor. Then the President gave it a set of facts, and asked it what conclusion it reached from these facts. The conclusion was illogical.

"Ze Gallic mind," Le Blanc hastened to explain. "We are not a logical people; we are people of what you call ze emotion, not ze reason."

The President and his Cabinet, acting as judges, looked incredulous. A bevy of scientists examined the mechanism of the robot. A psychologist was called in. After deliberating, they decided that the robot was operated by a device which amplified the power of telekinesis—that power by which mediums levitate ponderable matter without touching it—and that it was controlled by telepathy—a mechanical recipient en rapport with some human agent. The psychologist quickly located the agent—a young lady who had accompanied Le Blanc.

"I suggest," said President Matthews, "that if they are any other entries similarly controlled, they be immediately withdrawn, for they will surely be discovered. Remember, to win this contest the robot must reason for itself! There can be no outside control of any kind!"

A number of entries were immediately withdrawn. However, Dr. Ludwig Meyer of Berlin did not hesitate for a moment. He had entered eight robots.

They came goose-stepping out into the spotlight, dressed like soldiers of the World War, with steel helmets, rifles and bayonets.

"Mein schildren, giff a demonstration of the trench fighting during the Vorld Var," commanded Dr. Meyer. "Broceed."

The robots instantly divided into two parties, four on a side, and savagely attacked each other with fixed bayonets. One by one, they went down, until only one robot with a battered helmet and torn sleeve remained standing.

"Hans," said the doctor, addressing the remaining robot, "come here."

The robot goose-stepped toward the doctor and stood stiffly at attention.

"Vill you question him, Mr. President?" Dr. Meyer suggested.

"How old are you, Hans?" the President asked.

"Six months," was the ready reply.

"Quite a big boy for your age. You speak English well."

"I speak many languages und I speak all of them veil."

At this point one of the judges nudged the President.

"Don't look now," he said, "but when you question the robot, observe the doctor. He always holds that big seal ring on his right hand near his mouth."

"But you speak English with a German accent, Hans," continued the President with a smile-.

"Dot's because German iss my native tongue," Hans replied promptly.

The President glanced slyly at the doctor, and observed that he had raised the ring to his lips.

"May I see that ring you are wearing, Herr Doktor," the judge asked politely.

"Look at it if you vant too," the doctor replied, "but don't remove it from my finger. I've made a vow sever to take it off."

"Don't tell me you are superstitious, Doctor." Carefully the judge examined the ring which the scientist held before him. He had palmed a small jeweler's screw driver, and suddenly he brought it into play, with the result that a monogrammed hinged lid sprang upward, revealing the hollow interior of the ring.

The scientist withdrew his hand with an oath, and his florid jowls turned a deep purple.

WHAT did you see in the ring?" the President asked.

"A radio transmitter, Mr. President," was the reply.

"We have located a radio receiving set in the robot," called one of the others.

Without a word Dr. Meyer rose and waddled toward the door. One by one, his fallen robots arose and goose-stepped after him, Hans bringing up the rear. As Hans went out the door he turned, placed his thumb to his nose and wiggled his fingers at the assemblage, producing a gale of laughter.

"Now we come to the entry of Hugh Grimes," announced the President when the laughter had subsided. "I believe you have two robots, Mr. Grimes. Where are they?"

"They have been in this room for some time, witnessing the ludicrous performance staged by the learned Herr Doktor Meyer," Grimes replied.

A young couple, wearing evening clothes, arose from the end of the table where they had been sitting for the past fifteen minutes, and walked into white circle of light.

A murmur of astonishment went up from the audience. Those who had observed the entrance of the couple, and had seen them conversing with animation while they laughed at the antics of the learned doctor's robots, were more than astounded— they were awe-stricken.

"You don't mean to tell us that these two are robots!" exclaimed the President.

"I most assuredly do," replied Grimes. "And before the demonstration takes place, I insist that I be searched by your radio experts and that you put two of your best psychologists near me. I want it absolutely proved that I am not controlling them either by mental or electrical means."

"Very well, we'll have you searched," answered the President. "And while we're at it, we'll have the couple examined to see if they really are mechanical beings."

The examination was conducted, and the examiners pronounced themselves satisfied with Grimes and the two figures.

Young Doctor Gunning nudged Yvonne. "Those are the robots stolen from Al's laboratory?"

"Yes," she whispered in reply. "No one but Albert ever made robots so nearly perfect."

"Now that the examiners are satisfied," said Grimes, "permit me to introduce Gwendolyn and Percival. If the orchestra will play a waltz, they will dance for you."

The orchestra obliged, and the robots waltzed gracefully about in the circle of light. Then Percival held up his hand for silence.

"My partner and I," he said, "challenge the two best bridge players in the house to a game. If there is any doubt in your minds that we can reason intelligently, I think we can readily allay it."

A table and cards were brought, and two volunteer bridge players took their places. Both men were members of the Cabinet and judges of the contest, and both were acknowledged the two best bridge players of their set.

At first, the two Cabinet members appeared to underrate the prowess of their mechanical adversaries. Presently, however, they began to wear worried frowns, and before long both threw down their hands in defeat.

"It's absolutely uncanny," said Andrew Gorman, Secretary of Agriculture. "They seem to read our minds."

"Are there any further questions, Mr. President?" asked Percival. "Do you wish us to submit to further examination?"

"One moment, please." The President turned to confer with the two discomfited Cabinet members, and also summoned the technicians.

Hugh Grimes looked on with a triumphant smile. Presently he became aware that someone had slipped unobtrusively into a chair beside Yvonne. He glanced closely at the man, and his face blanched at what he saw. For the man was either Albert Bradshaw, or his twin! He had the same sunken chest, the deep blue eyes, the hollow cheeks with their consumptive flush. The man even raised his hand to cover a cough, in the manner so characteristic of Albert Bradshaw.

Yet Hugh Grimes had seen the fellow lying dead in his coffin seven months before—had seen the coffin closed, and had later witnessed the cremation!

The man turned and whispered something to Dr. Gunning, who got up and strode toward the door from which the various robots had emerged.

Then Grimes tore his fascinated gaze away from this twin of his murdered rival as he heard the President speaking:

"It is the opinion of the judges," said President Matthews, "that the robots Percival and Gwendolyn, created by that famous scientist Hugh Grimes, fulfill all the conditions necessary for the winning of the prize. If there are no further entries, we will consider the contest closed, and award the prize."

He looked around the room.

Suddenly the twin of Albert Bradshaw stood up.

"Mr. President," he said, "there is another entry. I request that you hold the. contest open a few moments longer."

"Whose entry?" the President asked. "And who are you?"

"The entry of Albert Bradshaw." The second question went unanswered.

"But Bradshaw died several months ago," the President answered.

"Does that disqualify him?"

The President turned to his fellow judges, and conferred with them for a moment.

"No, it doesn't disqualify him. Produce the entry,"

"I am that entry," was the reply. The President stared at the speaker for a moment.

"By the Lord Harry!" he gasped. "It's Bradshaw himself, come to life!" The newcomer pushed back his chair and strode out into the spotlight.

"As I previously informed you," he said, "I am Bradshaw's entry—Bradshaw's reasoning robot, if you please.

I am not going to do any card tricks for you. But I am going to expose the greatest fraud ever perpetrated on a group of gullible scientists. Hugh Grimes, do you mind having your two entries step once more into the spotlight?"'

"Why—er—not at all." Grimes nervously adjusted his pince-nez. "Percival. Gwendolyn'. Come here." The two robots that had put on such a convincing performance a moment before remained motionless.

"You will notice that they do not respond," said Bradshaw's entry. "It is because they are controlled from outside, and that control has been broken."

At this moment young Doctor Gunning stepped into the spotlight, grasping a frightened young man by his coat collar.

"This man," continued the Bradshaw robot, "is Grimes' laboratory assistant, Carl Overton. I believe his name is known to all of you, since he is the international bridge champion. Bring him here, will you, Doctor?" Expertly, he went through the pockets of the young man, and produced two flat rectangular objects studded with a number of buttons and each topped by a small visiphone disc.

"Those robots were stolen from Bradshaw, who made the control boxes I now hold, after Grimes had attempted to murder him with poison gas—an attempt which resulted in his death five months later. These robots cannot reason for themselves; therefore they are ineligible to win the prize which you were so ready to award them. I will let them tell you their own astonishing story."

He manipulated several buttons on the control boxes, and the two rigid robots immediately came to life. Clasping hands, they ran out into the spotlight.

"We were created by Albert Bradshaw," said Percival.

"And Mr. Grimes stole us from Mr. Bradshaw's laboratory," said Gwendolyn.

Grimes' face blanched. He rose to steal away, but two burly Secret Service men seized his arms and forcibly seated him.

Grimes broke a window and hurled a poison gas bomb through," continued Percival; "He didn't try to hide his face from Bradshaw, as he thought the latter would surely die in horrible agony. The fact that Bradshaw was holding a strip of blue litmus paper temporarily prolonged his life. The paper was turned red by the acid gas, and he broke a bottle of ammonia, thereby neutralizing it and preventing it from searing him further. Had it not been for this, he would never have been able to reach the door."

"When Mr, Bradshaw left the laboratory," continued Gwendolyn, "Grimes had two of his men carry us away."

"That's so," broke in Yvonne D'Arcy. "I saw Grimes and two men load both robots into the helicopter limousine and roar away."

"Enough," said President Matthews. Mr. Grimes, you are under arrest for murder, robbery and fraud. Mr. Overton, you also are under arrest for complicity.

"And now, Mr. Bradshaw, or Mr. Bradshaw's entry, as you choose to call yourself, you have not proved to us that you are a robot, independently thinking." ~

"Both points are easily proven, Mr. President," smiled the robot, advancing. He rolled up a sleeve, and taking a knife from his pocket, slit the skin of an arm. It did not bleed, and the muscles and tendons revealed beneath were undeniably artificial. Then he opened his shirt front, slit his chest, and revealed mechanism.

"You are undoubtedly a robot," admitted the President. "Now, will you be good enough to show us your reasoning mechanism?"

"First," said the robot, "I will tell you what Bradshaw discovered after more than twenty years of research. There can be no reasoning or thought without life. All life as we know it is a combination of two things—mind and matter. We have never been able to discover any form of life that is not a combination of both. The brain is not the mind, but in human beings it is the medium through which it makes itself manifest. Behold!"

He snatched off the blond wig and skull-case. The astounded onlookers saw a human brain snugly encased in a transparent skull-shaped receptacle. Tenuous, fine strands, almost invisible, extended in an intricate network over the delicate brain membranes. The hairlike strands almost completely covered the cerebellum and cerebrum, converging in the sickle-shaped partition of the falx cerebri, which divides the two hemispheres of the cerebrum. The entire brain was immersed in some viscous solution, and the fascinated audience could see it envelop the exposed furrows and convolutions.

The robot continued: "At first it was the intention of Bradshaw to obtain the brains of two individuals at the point of death, one a male and the other a female, and preserve them in this solution, which prevents organic tissue from wearing out and which also provides enough nourishment to last each brain a thousand years. Once destroyed, cells do not replace themselves—and they feed very slowly. Bradshaw perfected his solution after years of experimentation with the brains of lower animals.

"Science has proven that thought impulses are electrical in nature. Bradshaw effected a way to isolate the multiple thousands of nerve fibres, neurilemma, ganglia, axons and other essential parts of the nervous system. The olfactory nerves, the optic, auditory, motor, hypoglossal and other of the cranial nerves—all are connected to mechanical muscles, and the slightest electrical impulse motivates the mechanical robot. The brain, of course, gives off these electrical impulses.

"But before Bradshaw could obtain the two brains, he found himself at the point of death. He called upon his two friends, Frank Gunning, the surgeon, and Yvonne D'Arcy, his nurse, to transplant his brain in this solution.

"Mr. President, judges and spectators of this contest—as you may readily see, I am a robot physically. Mentally, I am Albert Bradshaw. Since there was no specification in the contest rules that organic as well as inorganic matter might not be used, I submit that I am the robot for which you offered the grand prize—the reasoning robot."'

The President turned and conferred with his Cabinet members for a few moments. Then he stood up.

"It is the unanimous opinion of the judges of this contest that the prize of one million dollars be awarded to the robot of Albert Bradshaw," he announced.

"I thank you, Mr. President and gentlemen," bowed the robot. "And now, since I am to depart once and for all upon that greatest of all adventures, death, I will first make a few bequests. To you, Mr. President, I hand my complete plans and formula for the construction of reasoning robots. By the employment of these plans and formulae, everyone who wishes to do so and whose brain is not too badly injured, may add to his short span of physical life a thousand useful years.

"One half of the prize—five hundred thousand dollars, I set aside for a fund to be devoted to the manufacture of reasoning robots. The other half I bequeath to my friends, Dr. Frank Gunning and Yvonne D'Arcy. I once thought that Yvonne loved me with a devotion that would endure, but now, since I have become a robot, I see how it is between these two, that it was my friend the doctor whom she really loved—so I wish much happiness to both.

"You will now see a demonstration of the way a reasoning robot can end his existence any time he cares to do so."

He took a small hammer from his coat pocket, and raised it over his head.

"Are there any questions before I break this glass shell that will release me?"

There was a scream from Yvonne. She ran up to him, caught his arm and snatched the hammer away.

"So! You thought I didn't love you, Albert!" she cried. "You were always inclined to be obtuse where women were concerned, however brilliant in other ways. I'll show you whether I loved you. Look!"

She snatched at her hair, tore a glossy black wig away, together with a skull-case, revealing another brain suspended in a glass container.

"I am a robot," she cried, "the robot you molded with your own hands! Do you want more proof than this?"

"But how—" stammered the bewildered Bradshaw.

"After Dr. Gunning had removed your brain and sealed it in the container," she said, "I asked him to do the same with mine. He refused. Said it would be murder and tried to dissuade me. For months I begged him to perform the operation. That is why you saw us so much together. Finally, in desperation yesterday, I swallowed a corrosive chemical that would burn out my abdominal organs without injuring my brain. The doctor tried to use a stomach pump. I fought him off until he knew it was too late to save my life.

"When at last I sank to the floor, in agony, he agreed to perform the operation, and mercifully administered the anesthetic. I awoke as I am now—a robot—your robot. Don't you want me, dear?"

Bradshaw clapped on his own wig and skull case, and gently replaced those of Yvonne.

"Want you?"

Suddenly he caught the slight, black-haired figure in his arms.

"Darling, I want you for a thousand years."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.