RGL e-Book Cover 2017Š

RGL e-Book Cover 2017Š

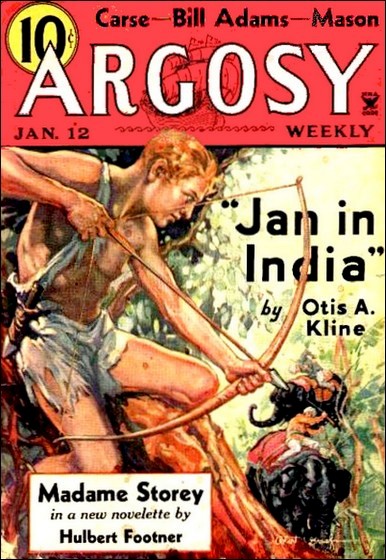

Argosy Weekly, 12 January 1935, with first part of "Jan in India"

THE sun sank, red and sullen, behind the tossing waters of the Bay of Bengal, and the lights of the yacht Georgia A. flashed on as the night descended with tropical suddenness.

Under the gay canopy which shaded the foredeck an after-dinner bridge game was in progress. The four who played were Harry Trevor, American millionaire sportsman and owner of the yacht, a tall, dark-haired man in his early forties; Georgia Trevor, his stately, Titian-haired wife; and their guests, Don Francesco Suarez and Doņa Isabella, from Venezuela.

Leaning over the stern rail side by side, but with eyes sullenly aloof from each other, and no thought for the beauty of the Indian night, were Jan Trevor and Ramona Suarez. Like his father, Jan was tall and broad-shouldered, yet he had the auburn hair and blue eyes of his mother. And instead of the stiff, military carriage of the elder Trevor, his was rather the lithe, supple grace of a jungle animal—a grace of movement that had not been cultivated in any drawing-room, but had, rather, been learned from the ocelot, the jaguar and the puma in their native haunts. For, despite his immaculate tropical evening clothes and the fashionable cut of his hair, Jan was but six months removed from the vast trackless jungle of South America that had mothered him.

Ramona was small and slender, a striking brunette with a slightly Oriental tilt to her big brown eyes, which showed that though she bore the name of Suarez, she was descended from a race much older than that which inhabits the Iberian Peninsula. Just now tears quivered on her long dark lashes, for she and Jan had quarreled for the first time. The quarrel had been trivial enough. This tall, red-headed fiancé of hers had been so attentive to her during the six months they had spent on their leisurely round-the-world cruise, that she had become piqued by his inattention of this evening and had spoken sharply to him.

She gazed out over the water for some time in silence. Then, her mood softening, she turned and laid a hand on his arm.

"Tell me, Jan. What is wrong? What has come over you? Ever since we came within sight of this strange jungle you have paid no attention to me. You go about as one in a dream. Or you hang over the rail, staring, sniffing the air. What has happened to you?"

Jan passed his hand over his eyes. "Ramona, I—I don't know. I have a strange feeling inside me which I cannot understand—a feeling of sadness. I wish I could explain—"

"You need not," she interrupted, her pride aroused. "You have tired of me, Jan, that is it. I know it—can tell it by your every action. It is well that this happened before we were married—that I found it out in time. I will leave you at the next port. Father, mother, and I can take a steer from Calcutta. Oh, I'm glad! Glad! Do you hear?"

Her last words were uttered in a choking voice, and ended in a muffled sob. Then she turned and sprinted across the deck toward the companionway.

With a single bound, Jan caught her, held her prisoned in his arms. "Ramona, please—" he begged. "You do not understand. I—I—"

She beat upon his breast with her tiny fists, wrenched herself free. "You are a brute, a beast! I hate you!" she sobbed.

Then she darted off and plunged down the companionway.

STANDING bewildered by this sudden change in the girl he had always considered so gentle, Jan waited until he heard the slam of her cabin door. What could he have done to arouse her so? Why should this strange moodiness which had seized him have so startling an effect upon her? And after all, what was it that had suddenly come over him upon their advent in these waters?

He returned to the rail to ponder the perplexing problem, and while he pondered he gazed at the distant jungle over which the gibbous moon was just rising, and from which there came to him strange scents and sounds—strange, yet somehow vaguely familiar.

First, there was the musty odor of decaying wood and leaves, which in every jungle is the same. There was the mingled perfume of many tropical wild flowers which were strange to him. And there were cat scents and cat sounds which he instantly recognized as such, though they were subtly different from those with which he had been familiar in his jungle. There were the calls of night birds, and somewhere a strange beast was trumpeting. Never before had he heard that sound, yet he instinctively knew that only an immense creature could make it.

Jan had never heard of nostalgia, and since he had never had a permanent home, save a cage in a private menagerie, which he hated, it would be difficult to imagine him homesick. Yet the jungle was his home. The jungle had reared him, fed him, mothered him. And while she had taught him many cruel lessons, they had been more than compensated for by the freedom and happiness she had brought him.

And so this alien jungle, which was like his jungle, yet different, had stirred a fierce longing in his heart, a strange, subjective yearning which he was unable to interpret in objective terms. He was drawn as iron is drawn to a lodestone, but he did not realize it. He only knew that he felt a strange sadness, an inexplicable longing; and that for no reason which he could understand, Ramona was angry with him.

As he leaned morosely over the rail, a plump, brown-skinned man who sat in a steamer chair beside the door of the companionway, observed him closely for some time. Then he took a lacquered case from beneath his voluminous garments, selected a cigarette, and lighted it, the flare of the match revealing his turbaned head, his round moon-like face, and the generously padded proportions of his short, rotund person.

Scarcely had the yellow flare died down ere a small, wiry figure slunk out from the shadows and crouched beside the chair of the obese one.

"I am here, babuji," he said in Urdu.

The fat man did not turn his head, but whispered from the corner of his mouth in the same language.

"The time has come to do what is to be done. See that you do it well. If you fail you will surely die. If you succeed you will not only acquire merit before your black goddess; you will be a rich man as well."

"I will not fail, babuji."

"So? Then wait here, my good Kupta, until I again strike a light."

The babu rose ponderously, and tossed his burning cigarette into the water. Then he circled the deck and mounted the ladder to the wheelhouse, where the second officer, Nelson, stood watch.

"Good evening, sair," he said with a profound bow.

"Evening," Nelson replied with a touch of surliness. He was not a man to encourage familiarity from any native, educated or otherwise.

"A cigarette, sahib?" The babu proffered his case.

"No, thanks," curtly.

The Indian took one, placed it between his flabby lips. Deliberately he fished out a match.

"Look, gentleman!" he exclaimed suddenly, pointing a chubby finger over the bow. "What is that floating in water ahead of us?"

Nelson gripped the wheel and strained his eyes forward. "Don't see a thing," he grunted.

The baba struck the match.

"Right there in front of us!" he exclaimed. "Looks like an overturned boat."

IN the meantime, the small wiry man had been lurking in the shadows, waiting for the signal of the lighted match. He now sprang out and ran swiftly and silently toward the unsuspecting Jan, who still leaned over the rail. In one hand he carried a heavy slung shot. The direction of the breeze was such that the jungle man could not scent the approach of the enemy. And the roar of the propeller drowned any slight noise which might otherwise have come to his acute hearing.

The slung shot whirled aloft, was brought down with sickening force on the wind-tousled red head.

Jan slumped silently over the rail.

His assailant stooped, caught him by the ankles, and heaved. The limp body turned over once, struck the waves with a great splash, the sound of which was muffled by the propeller, and disappeared from view.

A moment later the assassin had melted into the shadows.

Up in the wheelhouse, Nelson was still straining his eyes toward the moon- silvered water ahead. Presently he turned to the babu.

"You must be seeing things," he growled. "Maybe you've got some hashish in those cigarettes."

"Do not use hashish, gentleman," said Babu Chandra Kumar in a hurt tone. Covertly he glanced toward the stern rail. It was deserted. Then with an injured, "Good night, sair," he flung the cigarette into the water, and descended the ladder, whence he waddled slowly back to his steamer chair. As he squeezed his great bulk into that protesting piece of furniture, a voice came from the shadows.

"It is done, babuji."

"Very good, Kupta. I am sure that Kali will bless you. And here are your hundred rupees."

The coins clinked softly in the darkness, and the dusky Kupta once more merged with the shadows.

BABU CHANDRA KUMAR remained in his steamer chair for a full half hour. Then he took a small teakwood box from an inside pocket. Opening it, he extracted a bit of betel nut which he rolled in a pan leaf with a pellet of lime and a cardamon seed and thrust into his flabby mouth. Closing the box with a snap, he replaced it in his pocket, rose ponderously, and waddled to the starboard rail, where he stood, expectorating red juice over the side and watching the distant shore line which was plainly visible in the rays of the rising moon.

Presently he saw that for which he had been watching—a sampan with its sail bellying in the wind about halfway between the yacht and the shore. Swiftly he glanced up at the man in the wheelhouse.

Seeing that his back was turned, he shouted at the top of his voice, "Gentleman! Gentleman! Assistance! Help! Young sahib has jumped into the water!"

Nelson swung around.

"What's that?" he bellowed incredulously.

"Young sahib! He leaped into bay! I saw him! He will drown!" shrilled the babu.

"Man overboard!" the officer sang out.

Then he issued some swift orders.

There was instant confusion on the yacht. Cries of alarm from those on the foredeck mingled with the ringing of bells, the roar of the suddenly reversed screw, and the barking of orders.

The portly, red-faced Captain McGrew, who had been smoking and reading in his cabin, wheezed up the ladder, hastily buttoning his jacket. Harry Trevor and. Don Francesco dashed up the opposite ladder.

"Who was it?" Trevor demanded.

"It was your son, sir, according to the babu. Just now he shouted that the young sahib had leaped overboard."

"Good God! Jan? It seems incredible!"

"Bring her about! Break out lines and life preservers and man the rails! Stand by to lower a lifeboat," barked Captain McGrew.

Trevor and Don Francesco hurried to the foredeck once more to join the ladies. As they did so, Ramona came running up, her eyes red with weeping.

"What happened?" she asked. "I heard shouts, and the engines stopped."

"The babu says he just saw Jan jump overboard," said Trevor.

At this announcement Georgia Trevor went deathly white. Her husband passed a supporting arm around her.

"There, there. Don't be alarmed," he said, trying to hide his own concern. "The boy is a strong swimmer. Probably just leaped overboard for a lark. There's no danger. We'll have him back on board in a jiffy."

"But there are sharks in these waters. We saw two big ones following the ship this afternoon. Oh, Harry, we never should have brought him on this cruise. If anything has happened to him, we are to blame, because we insisted that he and Ramona should see the world together, before marrying."

"No, it is not your fault. It is mine."

It was Ramona who startled the group by this sudden assertion.

"Why, Ramona! What do you mean, dear?" asked the doņa.

"We quarreled," she said. "I told him I would leave him—never wanted to see him, again. And now he has gone—gone to his death."

She turned suddenly and flung herself sobbing into the arms of her foster mother.

Standing a few feet away from the group, mumbling his quid of betel, Babu Chandra Kumar smiled knowingly and spat into the water.

THE yacht came about with engines throbbing, then slowly cruised back over her former course, her searchlight sweeping the waves. A lifeboat was unshipped and swung out on its davits, ready to be lowered at a moment's notice. Men stood along the rails with life preservers, the lines coiled and ready.

The five who stood together on the foredeck moved to the bow, where they anxiously scanned the water, the doņa striving to reassure the sobbing girl, and Trevor supporting his half fainting wife.

Unnoticed by the others, the babu crossed the deck to the opposite rail as the ship came about. But instead of futilely gazing at the water ahead, he kept his eyes on the sampan, which was now nosing out toward the yacht.

Aided by the offshore breeze, the little sailing vessel made rapid progress in the direction of the yacht. And because of the reduced speed of the latter vessel, it had no difficulty in overhauling it.

As it drew near, the babu made out a turbaned figure in white standing at the rail. Instantly he ran, shouting, toward the little group in the bow.

"The maharaja comes!" he cried. "It is fishing boat of my master. Perhaps he can help us."

"The maharaja!" exclaimed Trevor. "How do you know, babuji?"

"That is his fishing vessel. And he is aboard."

"That's right. He told us at Singapore that he would be fishing in these waters."

"Ahoy the yacht," came a call from the sampan. "Anything wrong?"

Trevor cupped his hands as the sampan drew closer.

"My son is overboard, Maharaja," he shouted. "We are looking for him."

"Shocking! I'll help you search."

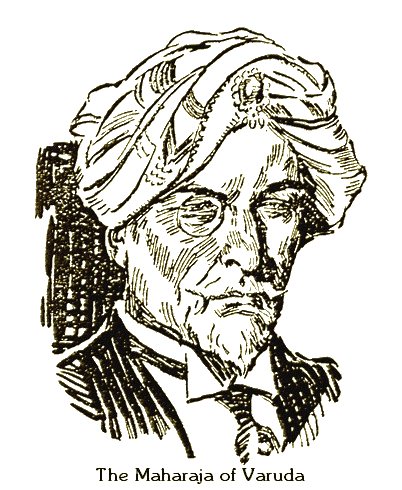

The two vessels cruised about in the vicinity until past midnight. Then both hove to, side by side, and the Maharaja of Varuda came aboard the yacht. He was slight and slender, with an iron-gray beard, a thin, hooked nose, curved like the blade of a scimitar, and small beady eyes that accentuated his hawk-like expression. Save for his jeweled turban, his dress was English, even to a beribboned monocle. Two handsome Hindu boys in their native garb followed him over the rail.

The maharaja bent low over the hand of the heart-broken Georgia Trevor. "Madame, I am devastated," he said. "But do not give up hope. Your son may have reached the shore. I believe you told me at Singapore that he was a strong swimmer."

"But the sharks! What could he do against those monsters?"

"They are not so numerous as you might think. As soon as it grows light enough I'll have my men search the shore line for some sign of him."

"You are very kind, maharaja sahib, but I fear it will be useless."

The maharaja greeted each of the others in turn, then addressed Harry Trevor.

"We have done all that is humanly possible tonight," he said. "I suggest that you drop anchor here, and rest in your cabins until morning. In the meantime, I will go ashore and organize my men for a search of the beach as soon as the sun rises."

"That's good of you, Maharaja," said Trevor, "but I can't remain here inactive. I'll go ashore with you."

"I, too," replied Don Francesco. "It is maddening to think of waiting here and doing nothing."

"Come ashore if you like, gentlemen. You will be welcome at my camp."

"May humble servant come also, your highness?" asked Babu Chandra Kumar. "Should like to help, if your highness will permit." He paused to snivel and brush away a tear. "I loved young sahib like son and had counted on exalted privilege of escorting him about Calcutta."

"You will probably be in the way," said the maharaja, with a disdainful glance at the babu's obese figure, "but come, anyway, since sahibs will not have any immediate use for your services as a guide. And bring your man. I have heard that he is a good shikari, and we may need men who are expert at trailing."

"Kupta is very great shikari, your highness. Can follow trail like hound."

SAVE for the half dozen men who stood guard, the camp of the maharaja was asleep when the party went ashore. Against the dark background of the jungle loomed a score of huge, slate-gray shapes—elephants. A few had lain down, but most of them stood, shifting their huge bulks from side to side, clanking their leg-chains and switching grass up over their backs.

The maharaja waved the babu and his servant to quarters among the mahouts. Trevor and Don Francesco were ushered to the richly carpeted and cushioned tent of his highness. Servants brought assorted liquors, soda, ice, cigarettes and cigars.

"Make yourselves comfortable, gentlemen," said the maharaja. "My tent is your tent and my servants are your servants. I must ask you to excuse me for a few moments. The elephants are restless, and I wish to inspect them. Only last night my most valuable elephant ran away, and Angad, her mahout, who went after her, has not returned.

"We may have urgent need for the others in the morning, so it would be embarrassing to have any more break away tonight."

"You mean—" began Trevor.

"I mean," replied the maharaja, "that if we find your son has made his way ashore, it is possible that we may have to do some dangerous jungle traveling to overtake him. My trackers will find him eventually, of course, but it will be the elephants that will carry us and our supplies. There is no safer, surer mode of jungle transportation."

He took a cigarette which one servant proffered in a jeweled box, permitted the other to light it, and, turning, left the tent. But he did not go to the elephant lines. Instead, he walked into a near-by tent where Babu Chandra Kumar sat alone.

The babu rose and made obeisance.

"You are sure there is no one within hearing?" asked the maharaja, glaring through his monocle.

"Am positive, your highness," replied the babu. "Kupta is already asleep, and none other except guards are stirring."

"Good. And now your report."

"The red-headed one is dead," said the babu. "Many leagues back Kupta slew him and threw him to sharks, while humble servant held attention of man in wheelhouse. Everything was done according to your highness orders."

"And you secured one of his handkerchiefs?"

"Yes, highness."

The babu produced a silk handkerchief in one corner of which were the initials "J. T."

"Splendid! Put it away until I signal you to produce it. But remember, it must be torn and bedraggled."

"Humble servant will see to that, highness."

"And now I have another task for you to perform. Take Sarkar, the mahout, who is about the size of the young red-headed sahib, and row along the shore to the southeast for a quarter of a mile. Then let him walk ashore barefooted on the sandy beach and make his way back to camp through the jungle, being careful to conceal his trail after he leaves the beach."

"Your highness, being so generous, will no doubt recall that humble servant is poor man with large family in Howrah," said the babu. "I will remember," replied the maharaja. "Already you have had a thousand rupees to divide with Kupta. Here is another thousand for serving me faithfully until we reach my palace. But all this is mere expense money. Once the little dark eyed beauty is safely delivered into the hands of my priests, no suspicion attaching to me for her disappearance, a lakh of rupees shall be yours. And if you show sufficient cleverness and aptitude it may be that I will make you my deewan for life."

"Your highness is most generous, indeed," replied the babu, bowing profoundly as the maharaja took his leave. But once the potentate had gone, he stuffed a quid of betel into his fat cheek and computed his possible profits for the journey. Already he had done Kupta out of four hundred rupees which were supposed to have gone to him for his assassin's work on the boat. The mahout, he felt sure, would do his part and keep silent for ten rupees. And for another fifty Kupta would willingly lead the assemblage through the jungle toward the maharaja's palace, while making it appear that he was trailing Jan.

With a beetle-stained smile, Chandra Kumar arose ponderously and went out toward the elephant lines, where Sarkar, the mahout, was sleeping.

AS HE leaned morosely over the rail, gazing at the distant jungle, Jan's first intimation of danger was when something crashed down on his head with stunning force. Things grew blurred and indistinct, and there was a strange weakness in his arms and legs. He sank to the rail. Then, though he felt himself being lifted and heaved overboard, he was unable to make the slightest resistance— could not even turn his head to look at his unknown enemy.

He splashed into the waves head-on, and went down through a seething maelstrom of black waters. The shock of falling into the water partly revived him, and he struggled feebly to reach the surface, meanwhile instinctively holding his breath.

Presently, when it seemed that his aching lungs were about to collapse, his head emerged into the air. He took a deep breath, shook the water from his eyes, and looked about him. The yacht was already more than a quarter of a mile away, and rapidly widening the distance between them. To shout, he knew, would be useless. At his right, not more than a mile distant, stretched a white ribbon of moonlit beach, and behind it the mysterious jungle which had so intrigued him. He kicked off his oxfords and removed his mess jacket. Once free of these impediments, he set out for the shore with long, steady strokes.

His head cleared rapidly as he made his way shoreward, and it occurred to him to wonder who had made this attempt on his life. On all the yacht, so far as he knew, he had not one single enemy. The captain and crew had all been friendly throughout the voyage. The babu and his servant, both of whom had graciously been lent to his father in Singapore by the maharaja, so the former might act as their dragoman in Calcutta, had been especially obsequious. His father and mother were ruled out, of course. Nor could the don and doņa have any possible reason for wanting to do away with him. But he had quarreled with Ramona. She had told him their engagement was over—that she never wanted to see him again.

Had Jan been brought up among men, he would have gained sufficient knowledge of human nature to be positive that the gentle Ramona, despite her tropical temper, would never attempt to kill him. But he had lived the greater part of his life in the jungle, and jungle codes were still a part of his nature.

Ramona had told him that she hated him—had been the only one on the yacht who had shown any open hostility toward him. And so he concluded that she had suited her actions to her words and had deliberately attempted to murder him. It was thus that any jungle creature would do—that he himself would do without compunction upon sufficient provocation.

The conviction brought him a greater sadness that he had ever known, for Ramona had come to mean more to him than life itself. And so, though he continued to swim onward with listless, automatic strokes, his heart was so heavy within him that he did not care whether he lived or died.

But in times of emergency, instinct is often stronger than reason or emotion. And so when Jan, chancing to look back, caught the glint of moonlight on a sail-like fin that was coming rapidly toward him, the instinct to live took command of him. He doubled, trebled, and presently quadrupled his former speed toward the shore. But each time, on glancing back, he saw that the dread killer of the sea was rapidly shortening the distance between them.

Presently, with the shore not more than a hundred yards distant, and the shark less than twenty feet behind him, he realized that his pursuer would be upon him before he could cover a third of the remaining distance. Ripping off his shirt, he flung it back over his head. It distracted the attention of the killer for a moment, during which the monster seized it and tore it to shreds in its razor sharp teeth. And during that moment, Jan gained a few feet. Taking his pocket knife from his trousers and placing it in his mouth, he wriggled free. Then, when the shark was a scant ten feet behind him, he tossed the sodden garment between them.

AGAIN the attention of the monster was distracted, and again Jan made a gain of a few feet. But the fish soon relinquished its tasteless morsel, and Jan, despite the fact that he was now making better progress than before, found himself being rapidly overhauled. Further flight, he saw, was futile, for it could only end in his being seized from behind in those cruel jaws. And with only a small pocket knife for a weapon, to turn and fight seemed equally hopeless.

But turn he did, after opening the blade and gripping the knife once more between his teeth. The monster was so close now that he could see it distinctly in the moonlight. It was a large hammerhead, fully fifteen feet in length, the most grotesque and one of the most dangerous of all the sharks that inhabit the Indian Ocean.

Seeing its toothsome quarry motionless, and apparently helpless, the shark plunged forward, opening its gleaming jaws to seize its prey. But when the flat snout was within two feet of him, Jan suddenly reached out with both hands and seized the two strange projections on each side of the monster's head, which gave it its name.

Puzzled by such unexpected tactics, the shark plunged onward, still trying to reach its intended victim. But it only succeeded in pushing the jungle man further toward the shore with each snapping lunge. Presently, after it had advanced about fifty feet in this fashion, it tired of such fruitless endeavors, shook its head free of those gripping hands, and backed away. Jan seized the opportunity to retreat, swimming backward and still keeping a sharp watch on his enemy.

It was well that he did so, for in a moment the shark darted forward once more, this time with lightning speed. Again Jan thrust out his hands, but this time, instead of merely employing them to keep his attacker away from him, he tightly gripped the two projections, and bearing down upon them, somersaulted over onto the creature's back and clamped his legs beneath the body just in front of the pectoral fins.

The monster instantly plunged under water, turning over and over to dislodge him. But he held his breath, and shifting his hold to the gill slits, turned his body so he was facing forward. Then he again clamped his legs around the body, and taking his pocket knife from between his teeth, tried to force the puny blade into the creature's brain. The thick skull, however, baffled him, so he shifted his attack to the eyes, which were situated at the extremities of the hammer-like projections. He successfully gouged out first one eye, then the other, while he maintained his precarious seat by means of his body-scissors and the gill slits. Then he carefully felt for and cut the jaw hinges on each side, rendering the shark incapable of seizing its prey.

This done, he kicked himself free of the monster, and swam for the surface, where he filled his aching lungs again and again. The shark broke water about thirty feet behind him a moment later, and he saw, to his consternation, that two more man-eaters were converging toward him, evidently attracted by the sounds of the struggle or the scent of animal blood.

THE shore was now but a hundred feet distant, and without a moment's hesitation, Jan turned and swam for it at top speed. But to his surprise and consternation, the maimed shark followed him as swiftly and unerringly as if it had not lost its sight—evidently by scent or sound, or perhaps both. In the meantime, the other two sharks came in from both sides with tremendous speed.

Jan covered fifty feet, and was again forced to turn and prepare to fight, but with three enemies this time instead of one. They came so swiftly that the last fifty feet might have been a mile, so far as his hope of escape was concerned. It was the most desperate situation in which he had ever found himself— desperate to the point of hopelessness. For what could he do against three such mighty enemies in their own element?

The two oncoming sharks drew up beside their maimed companion, now less than five feet from Jan. Then an astounding thing happened. For, instead of assisting in the pursuit, both simultaneously attacked the wounded hammerhead. In an instant there was a terrific struggle, a mighty threshing in the boiling, foaming water.

But Jan did not wait to see the outcome. Instead, he turned and once more struck out for the beach. A dozen powerful strokes, and he felt the sloping sand beneath his feet. He rose and ran splashing through the shallows. Not until dry sand was beneath him did he turn. The three contestants had disappeared, leaving only a few bubbles to mark the point of the struggle.

By this time, the yacht was only a speck of light upon the horizon. Jan stood resting from his exertions and watched it until it disappeared from view. Then he turned toward the dark, mysterious jungle behind him. The breeze carried the same scents and sounds that had attracted him when on the yacht. But the scents were much stronger, and the sounds much plainer, now.

For some time he stood there listening—sniffing the air. There remained to him only a few shreds of his underclothing, which had been torn in his struggle with the shark, and his pocket knife. He skilfully twisted the shreds into a G string and with his wet socks made a small pouch at one side for the knife. Then he melted silently into the shadowy depths of the forest.

Though his tread was as noiseless as that of any jungle cat, and his eyes, ears and nostrils were keenly alert for danger from the denizens of this unknown wilderness, the jungle bred Jan made his way forward as fearlessly as any man born and reared in civilization would walk the streets of his native city.

Presently, there came to him a powerful, unmistakable cat scent from close behind him, brought to him by a sudden shifting of the breeze. Instantly, he knew that a big feline of a breed new and strange to him was stalking him; and near enough for the charge. He turned, and caught the gleam of a great blinking pair of eyes.

Knowing itself discovered, the beast let out a roar, and charged. But with an agility which equaled that of the great cat, Jan sprang for the nearest tree, and swung himself into the lower branches just in time to escape the raking claws beneath him. He quickly made his way upward, but paused in his climb when a low growl suddenly came from the branch above him, accompanied by a new cat scent and the scratching of nails on bark, which told him that another large feline was descending to attack him.

Instantly he swung outward as far as he dared, on the limb upon which he was perched. Then, in a mottled patch of moonlight he caught sight of the descending brute against the trunk of the tree. It was jet black, with great yellow eyes, and about the size of a cougar.

On the ground below him the moonlight revealed the striped body of a cat that was larger, but no more dangerous to an unarmed man, than the one that was descending toward him. And while the tiger gazed upward, snarling and expectantly licking its chops, the black fury dropped lightly to the limb on which Jan was balanced, and with ears laid back and tail lashing the leaves, crouched for a spring.

AFTER the maharaja left the babu he did not inspect the elephant lines. Instead, he returned to his own tent where Trevor paced nervously back and forth, while Don Francesco sat in his chair and puffed violently at his slender, black cigar. Adjusting his monocle, the potentate walked to the table, sat down, and selected a cigarette which a servant quickly lighted for him.

"Rotten go, this," he remarked. "There's nothing more we can do until morning. Now if it had only happened in the day time we could be doing things. But this beastly waiting jangles one's nerves."

"It does that," Trevor agreed explosively. "Enough to drive a man nuts."

"Quite. But you mustn't let it get you. Come. Sit down and let me be your doctor. I prescribe a spot of brandy."

"His highness is right, amigo," said Don Francesco. "Worry can accomplish nothing. Constructive thinking and planning may help."

"Of course," replied Trevor, coming to the table. "I am a fool to get jittery. What's needed is constructive planning, and action."

Waving his servants away, the maharaja poured brandy for his guests.

Trevor tasted his drink and reached for a cigarette.

"Do you think, maharaja, that we will be able to find Jan in the morning— that is if he's still alive?"

"There is a strong possibility that we may," was the reply. "We can at least assure ourselves as to whether or not he has come ashore."

"How?"

"For several miles in both directions the beach is of soft sand. My trackers will easily be able to discern whether or not a man has come ashore."

"Right. But suppose he has gone on into the jungle. I have an idea that is the thing he is most likely to do. He grew up in the jungle, you know, and we all noticed that he seemed strangely attracted by this one the moment we came within sight of it."

"In that case," said the maharaja, "we must follow his trail until we can come up with him. My shikaris will be able to find him eventually, but it may take time."

"There is a possibility that we may be stuck here for days, weeks—even months."

"That is true," said the maharaja. "When we met in Singapore I did myself the honor of inviting you and your party to visit me. You declined then, because of your haste to get back to your affairs in America. However, since this matter has come up, it may be that you will change your mind. I flatter myself with the hope that you will, and all the resources of my little kingdom at your disposal."

"You are most kind, maharaja sahib," said Trevor. "I declined before because of urgent business at home. But there can be no more urgent business for me than the finding of my son. If a long search for him should be indicated by what we find in the morning, I will gladly avail myself of your kind invitation."

Morning dawned at last, and the camp was instantly astir with feverish activity. The maharaja divided his men into two parties to search the beach, one to go northwest, the other southeast. At his suggestion, Don Francesco accompanied the first party while he and Trevor went with the other.

At the head of this latter group of searchers waddled the fat babu, accompanied by Kupta the hillman.

Presently, when they had proceeded about a half a mile along the shore, the babu threw up his hands.

"Stop!" he cried. "Freshly tracks are here coming up out of the water."

Trevor sprang forward.

"Where?" he cried.

BUT a moment later, he saw them himself. The tracks of bare feet leading from the water's edge toward the jungle.

"Jan wore shoes," he said, "but he would have kicked them off in the water. Probably got rid of his socks, also." He turned to the maharaja. "Do you think it possible that any one else might have swum ashore here?"

"Hardly. No one left my little boat, and so far as we are aware, nobody but your son left the yacht. No one with any knowledge of these waters would be likely to try it from any other craft because of the danger from sharks. Your son, it seems, has escaped them by some miracle."

"Then you are reasonably certain these are Jan's tracks."

"Wait. Let us make sure." He called the babu. "Have your hillman inspect the tracks and tell us what sort of person made them," he ordered. Then he turned once more to Trevor. "The things these hillmen can tell from a few marks in the sand are uncanny," he said.

At Chandra Kumar's command, Kupta bent over the tracks. There followed a swift muttering in Urdu.

"Shikari says these are not tracks of Indian man, but of young and strongly sahib," the babu announced.

"That settles it," said the maharaja. "Take two men and go with him. Follow the trail into the jungle. In a half hour, send a man back to camp with news of what you have found on the trail. And in another half hour stop and wait for us, sending the second man to lead us to you. We will return for the elephants, and to pack."

When Trevor and the maharaja got back to the camp, they found that the ladies had already arrived there in one of the yacht's lifeboats, piloted by Officer Nelson. The eyes of all three showed the effect of a tearful, sleepless night.

"Have you learned anything?" all wanted to know in unison.

"Something that gives me great hope," Trevor replied. "Tracks leading into the jungle. We believe that Jan is alive and somewhere nearby."

"Alone and unarmed!" exclaimed Georgia Trevor. "What can he do? He will starve, or be devoured by wild beasts."

"I doubt that he will do either," said her husband. "Jan didn't manage to survive in the South American jungle for many years without learning a thing or two. The boy will be able to take care of himself. And we may find him any time now. An expert tracker is already on his trail, and we will follow as soon as the elephants are loaded."

"You will follow? But what of us? Are we to be left behind to—to die of suspense?"

"I have two large howdahs in addition to the pad elephants," said the maharaja. "There will be ample room for all if you care to come with us."

"But will it not be dangerous for the ladies?" asked Don Francesco.

"Not at all," replied the potentate. "The back of a docile and intelligent elephant is the safest place for any one in the jungle."

IN less than a half hour the caravan was loaded and on its way into the jungle. The second man, who had come from Kupta and the babu, led the way. In the first howdah rode the maharaja with Trevor, Don Francesco, and a servant to take charge of the rifles. In the second rode the three ladies. Behind them came the loaded pad elephants. And strung out in two files, one on each side, walked the maharaja's retainers, armed with spears and large jungle knives.

An hour's ride brought them to the bank of a small stream. And here, squatting at their ease in the dense shade of a deodar tree, they found the babu and Kupta, mumbling their betel and expectorating red juice at such unfortunate insects as chanced to wander within range.

At sight of the maharaja's elephant, the babu hoisted himself ponderously to his feet, and the hillman sprang lightly up beside him. Then both salaamed.

"Proceed on the trail, babuji," ordered the maharaja, "and see to it that your hillman does not lead us astray."

"He will not lose trail, your highness," the babu replied. "Kupta is very expertly shikari."

Taking a rusty looking old umbrella which Sarkar, the mahout, had brought for him from his private kit, he raised it over his head and waddled off behind the wiry hillman.

They followed the stream for some distance, then crossed at a shallow ford which seemed to have been used extensively both by domestic and jungle animals. The bank, which had been flattened out for more than a hundred feet on both sides of the stream, was indented with the tracks of elephants, deer, buffalo, horses and other lesser herbivores, and in the soft mud at the water's edge, Trevor saw the pugs of tigers and leopards. Obviously it was an old game trail which had come to be frequently utilized by man.

Having crossed the ford, Kupta circled for a time, then struck off in a northerly direction. The babu lumbered heavily after him, grunting, wheezing, and using the greasy end of his turban from time to time to mop the streaming perspiration from his eyes.

Trevor, to whom jungle travel was no novelty, noticed that they crossed and recrossed the well-marked game trail they had passed at the ford, but never stayed upon it for any great length of time. He concluded, from this, that Jan was following the trail, possibly in the hope of reaching civilization, or perhaps for the more primitive and necessary purpose of making a kill.

At noon they paused at a little pool, fed by a limpid spring which trickled down from the rocky hillside. Scarcely had the elephants paused to discharge their passengers, when the babu, who had climbed up beside the spring for a drink of water, came rushing toward them, waving a torn, sodden handkerchief and shouting shrilly.

"Highness! Sahibs! Memsahibs! Have found most importantly clue! See! See!"

"What is it, babuji? Let me see," said Trevor, who had been the first to dismount.

With the important air of one who has made a momentous discovery, Chandra Kumar handed him the handkerchief.

"Look at initials—in corner," puffed the babu.

"'J.T.,' by the gods!" exclaimed Trevor. "It's Jan's, all right."

The ragged bit of cloth was quickly passed from hand to hand as the others crowded around, and as quickly identified. The maharaja was the last to examine it. He squinted at it through his monocle for a moment. Then he turned to Georgia Trevor.

"You are positive that this is your son's handkerchief?" he asked.

"Positive."

"Then it is time for us to crystallize our plans. We have found that h is traveling swiftly to the northward. If he continues, he will soon be in my territory, Varuda, and my palace at Varudapur will be an ideal base from which to conduct our search. I therefore suggest that we make camp here, and send two pad elephants back to the coast for any baggage you may wish to bring with you, instructing the commander of your yacht to take it to Calcutta and there await further orders. In the meantime, I will send the babu and the shikari forward on the trail, to learn whither it leads, and to make inquiry as to whether or not any natives they may encounter have seen your son."

Georgia Trevor turned to her husband.

"What do you think, Harry?"

"A splendid plan," he replied. "We accept your suggestion and invitation, maharaja, with pleasure and with gratitude."

The potentate included all five of his guests with a courtly bow, "My house will be most signally honored," he said.

Then he turned, clapped his hands, and issued a few swift orders. In a few moments the elephants were relieved of their loads, and a village of tents grew as if by magic. There was a large tent for the three ladies, another for Trevor and Don Francesco, and a third for the maharaja. All three were sumptuously and lavishly furnished with thick rugs, divans with spring mattresses, silken cushions, and embroidered hangings.

As soon as the two pad elephants had been dispatched, the maharaja retired to his tent and sent for the babu. A few moments later, as Chandra Kumar wheezed in past the ornate curtains, the potentate dismissed his two servants. Then he beckoned the babu to him, and spoke softly in Bengali.

"The first part of our plan is accomplished," he said. "The tracks of Sarkar deceived them, and the handkerchief proved most convincing. But there yet remains much to be done. What of Zafarulla Khan and his Pathan cutthroats? Are you sure they are encamped near here, and that you will be able to find them?"

"Those horse-stealing malefactors would camp where I bade them until the British leave India, for a chance to win the princely sum which your highness has promised them," he replied.

"Very well. Here are the five thousand rupees which you are to pay them. And ten thousand more await them when they deliver the girl to my priests. Now here is the plan in full, and it must be carried out to the letter or we will all be ruined."

His voice dropped to a whisper, and the babu nodded and grunted from time to time, to show that he understood.

Shortly thereafter Chandra Kumar rode away to the northward on a small pad elephant, guided by Sarkar, the mahout, with Kupta ranging before them as if following a trail.

UNARMED and out on the end of the limb, with the black leopard ready to spring upon him, while the tiger waited expectantly below, Jan realized that he was in—grave danger. Yet he sat there calmly enough—waiting. Suddenly the leopard sprang. And with equal quickness, the jungle man dropped from his perch, swinging by his hands.

The tiger roared and leaped upward at sight of the man dangling so temptingly above him. The leopard, unable to check its impetus, turned in midair and tried to grasp the end of the limb. But Jan's sudden drop had pulled it down out of reach, and the black feline, now squalling with fear, hurtled downward, straight into the waiting claws of the tiger.

Jan once more swung lightly up on the limb, to watch the scrimmage going on in the little moonlight glade below him. He had expected to see the leopard instantly killed, and was therefore surprised to see that it was giving an excellent account of itself, falling on its back and using its fearful hind claws for defense each time it was attacked, while the jungle resounded with its spitting and caterwauling, mingled with the snarls and deep-throated roars of the tiger.

But, though he would have enjoyed seeing the conclusion of this jungle battle, it suddenly came to him that this was his golden opportunity for making good his escape. So he swung away through the interlaced branches and vines as easily as any arboreal ape—and far more swiftly. In a few moments all sounds of the battle died behind him, and the normal night cries of the smaller jungle inhabitants, which fear had stilled in the battle area, were resumed.

For mile after mile he swung along with tireless, effortless ease. And many and varied were the jungle scenes that unfolded beneath him. Once he passed quite near to a herd of elephants, feeding—great ponderous hulks in the moonlight, tearing off branches with their sinuous trunks and munching the leaves and twigs. Presently one of them trumpeted, and he identified the sound he had heard from the yacht.

Farther on he disturbed a tribe of rhesus monkeys in their leafy dormitory, and departed followed by their chattered imprecations. Later, a skulking leopard passed beneath him, its spots showing plainly in the moonlight, reminding him of the jaguars of his South American jungle.

Presently he came to a large tree in which a pair of peafowls roosted. The hen roused at his approach and flapped swiftly away through the jungle. But the cock awoke too late. He grasped it by the neck, took out his pocket knife, and in a few moments was feasting on its raw, warm flesh. Again he was reminded of his native jungle, and of the many curassows he had eaten in this same manner.

Having satisfied his hunger, he swung off once more, looking for water to quench his thirst. Presently he reached a tree that overhung a small stream. He was about to descend when a huge striped form slunk out of the shadows beneath him. The tiger waded into the stream up to its sagging belly and stood there lapping the water.

Presently it lay down, wallowing in the shallows. Weary of waiting, Jan presently grew sleepy. He decided to defer his drink until the morrow, so searched out a convenient crotch, curled up, and was soon asleep.

THE jungle man was awakened by a shaft of orange gold sunlight which, penetrating his leafy canopy, struck him full in the face. He arose, stretched, and looked down at the scene beneath him. The tiger was gone, but its huge pugs were plainly visible in the soft gravelly bank.

Thirsty as he was, Jan swung through the neighboring trees and made a careful survey of all the nearby thickets before he descended. The water was warm, but clear and sweet, and he noticed that a little farther out there were flat rocks in the stream bed. This gave him an idea; so, after he had satisfied his thirst, he waded out into the stream and looked about until he had found a hard flinty stone which roughly resembled a double-bitted ax head. Deftly he chipped away at it until he had two ragged cutting edges and a groove down the center on both sides.

This done, he cut a straight limb from an ironwood tree, shaped it into a stout haft with his knife, and after splitting one end, bound the head in place with strips of tough fibrous bark torn from a vine.

When his work was finished the sun had passed the meridian, but he had a stone ax as good as had ever been wielded by neanderthal man. More strips of bark, plaited together, formed a shoulder strap from which he slung his heavy weapon. And primitive though it was, it gave him a feeling of confidence, for he knew that sooner or later he must fight it out with the great carnivores of this jungle, and the weapon would help to counterbalance their superiority of tooth and claw. Indeed, he was more than a little anxious to try conclusions with the next tiger or leopard that might come this way, as he always preferred fight to flight, where there was anything approaching an equal chance.

Jan had been so engrossed in the making of his weapon that he had forgotten all about food. Now, however, his empty stomach began to remind him of his negligence. And the sight of a school of fish moving lazily through the shallows quickened his appetite. In a clump of bamboo near by he found a pole that had been broken off by the passage of some heavy animal, and was quite well seasoned. After trimming off the branches and cutting it down to the required length, he split the segment at one end into four pieces, which he held apart by means of crossed sticks bound with bits of bark. After sharpening the four ends he took his fishing spear to the stream and soon had three fat fish gasping on the bank.

He crouched beside his catch, ate them raw, and after a long, satisfying drink from the stream, proceeded along the bank. He had followed the stream for some distance when, upon rounding a sharp turn, he suddenly came face to face with a huge, leather-armored beast with a horn on its snout, wallowing in the mud.

With an angry snort, the rhinoceros scrambled to its feet and charged. Jan hurled his spear straight at the monster's lowered head and, turning, sprang up the bank. He caught hold of a stout vine and scrambled up hand over hand, just in time to escape the earth-shaking charge. The bamboo spear, instead of checking the brute, had only served to infuriate it, and it rooted angrily at the base of the tree, gouging out great chunks of bark.

But the jungle man did not remain in that tree. Instead, he resumed his journey, keeping to the trees and vines which overhung the stream. He traveled thus until the sun hung low on the horizon. Then there came to his sensitive nostrils the pungent smell of wood smoke, and something else—the strong, scent of tiger.

Cautiously, soundlessly, he swung onward, and in a moment saw the source of the smoke. A brown man, naked save for the dhoti about his loins, and his turban, was bending over a small cooking fire. With him was a brown boy similarly attired, who had just brought up an armful of wood and was starting out for another. Jan saw that the man was stirring something in a small kettle over the fire, that a large, double curved knife hung at his side, and a long spear lay near at hand. A few feet from the fire was a crude shelter of bamboo thatched with leaves.

THE boy walked straight toward the tree in which the jungle man was perched. In his right hand he carried a knife, double-curved like that of the man, but smaller, and with this, as he came beneath the tree, he began cutting bits of underbrush for firewood.

At this instant Jan discovered the source of the cat scent. A huge tigress, taking advantage of every bit of available cover, was noiselessly stalking the boy—was at that moment not thirty feet from him.

Swiftly the jungle man dropped from limb to limb. To shout a warning to the boy he knew would be useless. The great cat would have him before he could run ten feet. As Jan reached the lowermost limb the tigress uttered a rumbling growl and charged. The boy stood rooted to his tracks by terror.

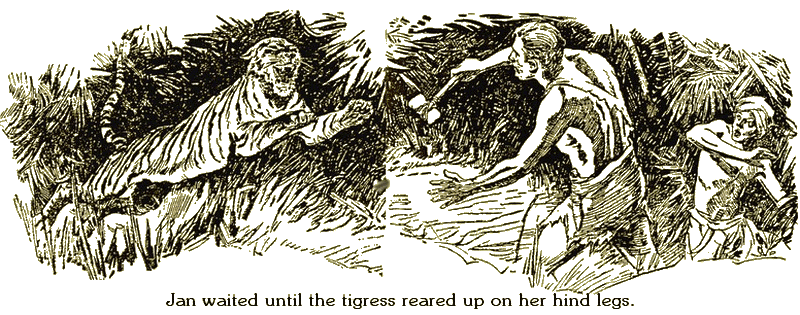

Lightly the jungle man dropped between the charging feline and its prey, his stone ax ready for action. The tigress paused for an instant, then seeing that only a man faced her, charged forward with renewed fury.

Jan waited until she reared up on her hind legs to seize him. Then he swung his stone ax with a circular motion that caught the brute a terrific blow on the side of the head. The jagged stone struck between eye and ear with such force that the eye popped out of its socket and the beast was bowled over on her right side.

Roaring with fury, the tigress scrambled to her feet and renewed the attack. This time Jan clouted her on the other side of the head, again knocking her off balance and rolling her over and over. Half dazed, she lay still for a moment, and the jungle man rushed in for the finishing stroke. But the tigress was far from dead, though she was now reduced to fighting defensively.

Throwing herself first on one side, then the other, she succeeded in warding off the blows from her head and body with her raking claws, and also in inflicting several deep gashes upon her enemy.

At this juncture Jan heard a shriek from the direction of the camp. From the tail of his eye he saw beside the fire the naked brown man struggling in the jaws of a tiger, evidently the mate of the beast he was fighting. The tigress, however, was still very much alive, so much so that the jungle man dared not turn away or relinquish the advantage he had gained. To do so would have meant almost certain death.

When next he was able to look toward the camp fire he saw that it was deserted. A moment later a childish voice that shook with terror sounded behind him.

"I have brought my father's spear for you, sahib ."

"Give it to me."

The spear was thrust around in front of him.

Jan dropped the ax and seized it. In a moment he had plunged the long steel blade through the heart of the snarling carnivore, pinning her to the ground; and in another, she had relaxed in death.

The jungle man turned and looked at the small brown boy, who stood with tears coursing down his cheeks.

"O great shikari, O mighty hunter," he quavered. "The other bagh has carried off my father. Perhaps he still lives. Will you kill it also, and save him for me?"

"I'll try," Jan promised.

HE wrenched the spear from the carcass of the fallen tigress, took up his stone ax, and slung it from the carry strap. Then he hurried to the camp fire. The trail left by the man-eater was plain enough. The brute had bounded away with great twenty-foot leaps, carrying the man as easily as a cat carries a rat. Occasional gouts of blood from the wounded man spattered the trail.

Jan set out, following at a swift, tireless trot. The little brown boy clung close at his heels. Soon the track showed that the tiger had slowed down to a trot. The huge pugs were comparatively close together, and there were narrow lines left by the dragging feet of its victim.

The trail paralleled the little stream and suddenly brought them to its confluence with a broader one—a small river. Here the pugs led straight down to the water's edge and ended in the shallows.

"The bagh has swum the river," said the boy.

"We will swim after him," Jan replied.

"But there are muggers—big ones. They would eat us."

The lad pointed to where several ugly crocodile snouts projected above the surface.

Jan barely glanced at them. Then he looked across the narrow river. The farther bank was plainly visible, and there were no tiger pugs on it. Yet the tiger could not have climbed up that bank without leaving a plain trail. Perhaps it had only swum up or down stream for a short distance, then come out on the same side. Jan searched the bank for a half mile in both directions, but found no tracks.

"Maybe the muggers got both," hazarded the boy.

"In any event, it will be too late to save your father if we find him now," Jan replied.

"But I would save him from being eaten, sahib, that I may perform the true duties of an eldest son."

"And what may that be?"

"To burn his body and cast his ashes into the Ganges."

Jan shook his head uncomprehendingly. He could not understand the sense of risking one's life to save a dead body, only to burn it immediately afterward. Yet, somehow, he liked this black-eyed, brown-skinned lad.

"We will cross the river," he announced.

Some distance upstream he had noticed a place where the leafy vault of trees and vines came almost together above the stream. He led the way to this point, the boy following.

"Get up on my back," he ordered, "and hold the spear."

The lad did as he was bidden, and Jan swarmed effortlessly up a thick vine with his light burden. He soon found a stout projecting limb that suited his purpose, and walked out on it until he stood high above the middle of the stream.

"Hang on," he cried. Then he leaped as a diver leaps from a springboard. The brown boy gasped, but clung tightly as they hurtled dizzily through space.

Jan caught a limb of the opposite tree some ten feet lower down, and clung. It sagged dangerously, and a huge mugger below them opened its jaws as if in pleasant anticipation. But the limb held, and in a moment more the two stood safely on the bank. Jan took the spear.

"Now we will look for the bagh," he said.

THEY walked back along the bank, and presently. the jungle man saw the trail which, had escaped him before.

The tiger had swum straight across, but instead of going up the bank had pulled itself up on the trunk of a tree undermined by the current which sagged out horizontally only a foot above the water.

The trail led straight back through the trees, over a low hill, and into a patch of tall jungle grass. Jan went warily through that grass, his spear ready poised in his hand for instant action. It was an ideal hiding place for any animal, but most especially for a tiger, whose stripes so perfectly simulated its pattern of light and shadow.

The path wound through the grass for a short distance. Then they suddenly came upon the trampled, blood-soaked spot where the tiger had devoured its kill. The signs were unmistakable. And all that the beast had left consisted of a bedraggled turban, some chewed bits of loin cloth, and the long, double-curved knife which the deceased had worn at his waist, attached to the ragged stubs of what had once been a leather belt.

The boy gathered the grisly tokens into a little pile, then squatted on his heels before them, rocking back and forth and moaning.

Jan watched him for some time in silence. Presently he said: "Come. We have yet to find the bagh and slay it."

"It is useless to find the bagh now," groaned the boy, "for I cannot perform the funeral rites for my father."

"Why not?" Jan asked. "Since your father is inside the bagh, we will slay the beast and burn it. Thus you may perform the funeral rites for your father and later cast his ashes into the Ganges."

The lad looked up thoughtfully.

"I do not know that the Brahmins would approve of such a burning," he said. "And yet, it is all that is left to do. So let us look for the bagh." He picked up the turban and knife, and stood up. The former, he fitted over his own small turban. The latter he extended to Jan. "Take this kukrie," he said, "since you do not have one. It will be very useful in the jungle."

Jan accepted the gift with befitting gravity, and set off once more on the trail of the tiger. It wound through the grass for some distance, then led back through the trees toward the river. Soon the cat scent grew very strong, and the jungle man moved forward with the utmost caution. Presently he saw the tiger sprawling in the shallows in a little inlet that connected with the river.

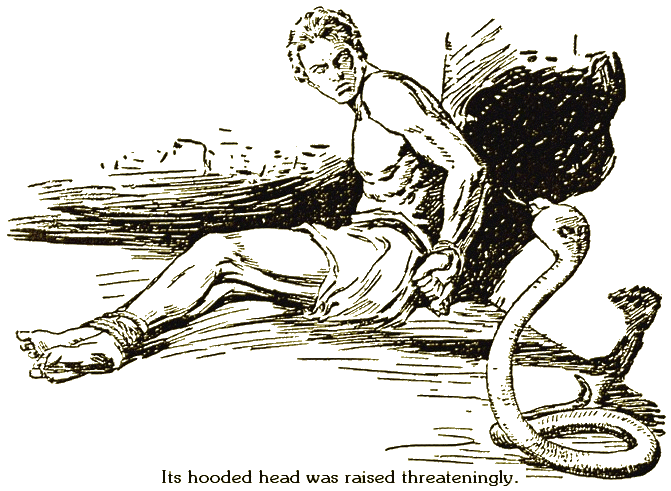

Noiselessly, he raised the heavy spear for the cast. But it was never made. For at that instant, Jan felt a stinging pain in his right forearm. A great, spade-shaped serpent head was clamped upon it. He dropped the spear, and gripping the snake behind the head with his left hand, squeezed it until its jaws loosened. But in the meantime the heavy coils of its enormous body had slithered down from the branch on which they were draped, and were flung, one after another, around his shoulder, as a hawser is thrown over a mooring post. Jan managed to keep his head and body free of those coils, but his right arm and shoulder were imprisoned.

Hearing the struggle so close at hand, the tiger bounded to its feet. Instantly catching sight of the jungle man, it growled thunderously and charged. Jan made a superhuman effort to wrench his arm and shoulder free from those crushing folds, but he could not loosen the vise-like grip of the reptile.

AS SOON as the babu had ridden well out of sight of the camp on the pad elephant, he ordered Sarkar, the mahout, to halt the beast, and called Kupta to come and ride with him. Then they started off once more, this time at a swifter pace, and straight for their objective, without any pretense of following a trail.

After a ride of about five miles, they came to a small camp situated in a pleasant grove of trees, through which a clear brook meandered. A short distance from the camp a herd of horses was grazing under the watchful eyes of two mounted and armed Pathans. Swarthy, bearded men lounged about in the shade, smoking and chatting.

As the elephant approached, one of these seized a rifle, sprang to his feet, and shouted a challenge in Pashto.

"Ho, strangers. What do you want?"

"I seek a word with Zafarulla Khan," replied the babu in the same language.

"Then you are Chandra Kumar?"

"In the flesh."

"In very good flesh, I observe," said the Pathan with a sly wink at his comrades, who laughed uproariously as the babu closed his umbrella and clumsily dismounted from his seat on the kneeling elephant.

"Said the crow to the pigeon," replied Chandra Kumar with a bland smile.

Whereupon the laugh was turned against the jester, for he was a very lean and cadaverous man. But like many jesters, he could give with better grace than he could receive.

"Our leader expects you, O father of a pig," he snarled.

"Lead on, my son, and I will follow," retorted the babu, with his same bland smile.

Goaded by the laughter of his comrades at this unexpected retort, the Pathan glared furiously and raised his rifle threateningly, as if he would brain the babu with it.

But the latter stood his ground without a change of countenance, so he turned and strode away, Chandra Kumar waddling after him.

He stopped before one of the tents. "The Bengali has come," he announced. Then he stalked away.

The babu paused at the doorway.

"Adab, Zafarulla Khan," he said pleasantly.

"Adab araz, babuji," was the deep voiced reply. "Bismillah! Enter, in the name of Allah."

The babu kicked off his slippers, dropped his folded umbrella across them, and stepped inside.

Zafarulla Khan, a perfect giant of a man with a beard dyed flaming red with henna, and a fierce, hawk-like countenance that was seamed with battle scars, sat cross-legged on a blood red Baluchi rug, smoking a hookah. His rifle leaned against a bale of rugs nearby, and his heavy tulwar lay beside him. A huge churdh, the terrible Afghan knife, kept company with a pair of pearl handled revolvers that were thrust into his sash.

"Fahdul," he invited with a wave of his hand. "Be seated."

The babu sat down ponderously and accepted the flexible, ivory bitted stem of the hookah which his host passed to him. Placing it to his lips, he inhaled deeply, making a neroli scented water bubble noisily in the ornate bowl.

The Pathan clapped his hands, and a beardless boy appeared in the doorway.

"Chai," roared Zafarulla Khan.

In a few moments, the boy returned with two small glasses of sweet, syrupy tea. Minutes were consumed in sipping, puffing, and polite inquiries as to the state of each man's health, as well as his family and all his immediate relatives.

This formality concluded, the babu got down to business.

"It is set for tonight," he said.

"It is not set until I give the word," growled Zafarulla Khan. "Where is the money?"

"Here. Count it." Chandra Kumar tossed a clinking bag between them. "Twenty-five hundred rupees."

"What's that!" roared the Pathan. "Wallahi! You were to bring five thousand. The agreement was for ten thousand rupees, one-half down and one-half when the girl is delivered to the priest. Now by my head and beard—"

"Wait!" The babu checked him with upraised hand, then continued blandly: "You must have misunderstood. I told you the priest would pay you five thousand when the girl was delivered, and I would pay you half that sum before the raid."

"You said five thousand, O dog and son of a dog!"

"I distinctly said, one half of that amount."

"One-half of ten thousand!"

"No, of five."

Zafarulla Khan raged, fumed, blustered and pleaded. He called upon Allah, Mohammed, and all the Moslem saints and prophets to bear him witness. But through it all, the babu remained placid and unruffled.

When the storm had somewhat subsided, Chandra Kumar proffered his betel box, but the Pathan struck it from his hand, then drew his churdh and fingered the keen blade significantly.

"Do you realize, O unbelieving swine," he growled, "how easy it would be for me to slit your throat, take the money, and leave you here for the hyenas and jackals? The conviction grows upon me that this is what I should do."

"But it is not what you will do," said the babu calmly enough, though he had grown somewhat pale beneath his brown skin.

"And why not?"

"Because if you did, you would have but twenty-five hundred rupees, whereas, for a bloodless raid and a pleasant ride you will have seventy-five hundred. Furthermore, both my master and the British would hunt you and your men down like mad dogs."

"Who says the raid will be bloodless and the ride pleasant? It is no light thing to kidnap a memsahib. For such a crime the British would hunt a man to the ends of the earth. Better to slit the throat of such as you, take my small gain, and have done with it."

"But as I have told you, the girl is not a memsahib, but an oriental. You have but to look at her great languorous eyes—her raven hair—"

"Hah! Perhaps I shall keep her for myself."

"Then you will make the raid?"

"Ayewah! But not for this paltry bag of coin—only for the sake of a look at this ravishing beauty."

The babu chuckled.

"Remember, she is to be turned over unharmed to the priest, if you would collect the five thousand rupees. And no slave girl is worth such a sum. Nor would you chance losing it, were the lovely Nour-mahal herself in your power. Your love of gold is too great for that."

"So you think," rumbled Zafarulla Khan. "But what of the plans?"

The babu again tendered his betel box, and this time the Pathan helped himself to a quid. Then he reached behind him for a brass cuspidor which he placed on the rug between them.

"The raid is to be staged just after sunset, when it will be light enough to see, yet dark enough so details and disguises will not be seen too clearly."

"Eh? There will be disguises?"

"I have brought them in a bundle on the elephant, Rajput clothing for all, great black false beards such as the Rajputs wear, and a can of petrol with which beards and clothing may be soaked when you have done with them and are ready to burn them."

"So The Rajputs are to take the blame."

"Why not? It is the only logical disguise."

"But the only Rajputs in this vicinity are men of the true faith, Moslems like ourselves."

"UPON whom, then, would you place the blame? And all of the Rajputs in Rissapur are not Muslim. Many have held to the faith of their forefathers."

"Billahi! Rissapur! I begin to smell a mouse in the rice bag! It is said there is no love lost between your Hindu kingling and the Muslim Maharaja of Rissapur."

"You smell a mouse which does not exist. They are warm friends."

"Well, perhaps. But I have my doubts. Proceed."

"You will ride down upon the camp, wearing the Rajput disguises, shouting the Rajput war-cry, and firing your guns into the air."

"Only to be shot by the sahibs."

"Nay, the sahibs will not be in the camp, and the guards will run into the woods at the first sounds of the raid."

"But I have heard that some of these memsahibs can shoot as well as a man."

"Not these," replied the babu. "Besides, their guns will be loaded with blank cartridges. You will seize the young one and ride off with her, taking care that no harm shall come to her or the others. On arriving at this camp, you will pile your disguises on the ground, pour petrol over them and burn them. Then you will ride on into Rissapur territotyr."

"Subhanallah! So I thought. The mouse scent again grows strong."

"When you reach the road that leads into the city, you will follow it until you come to the red shrine of Ganesha. Your men will ride on into the city, but you, carrying the girl, will turnoff there, and ride alone with her due north until you reach the river. There Thakoor, the priest, will await you with the money."

"Or an ambush to shoot me down."

"Not at all. My master does not wish the plot disclosed, and your men could go to the Maharaja of Rissapur with their grievances if you did not return with the money."

"So they could. Say on."

"When you have received the money you will ride on into Rissapur, pay your men, and order them to leave separately, by various ways, to reunite in any other place you may designate."

The Pathan slapped his thigh.

"Mashallah!" he exclaimed. "It is a good scheme, and we are just the men to carry it out. But still the mouse scent lingers. It is whispered that the British Raj would force a union of Varuda and Rissapur, and that the prince who succeeds in winning their favor will rule both. Now if this scandal were brought to the door of the Maharaja of Rissapur—"

"Pure bazaar gossip," the babu interrupted him, rising. "Heed it not, and think no more of super-plots which do not exist."

Zafarulla Khan thrust the bag of coins into his sash, and stood up. He towered above the portly babu like a cedar above an olive tree as the two made their way to where the elephant knelt.

With the help of Kupta, the Bangali cast off the ropes which held the bundle of disguises and the means to destroy them, and lowered the bundle to the ground. At a curt command from their leader, two of Zafarulla Khan's men took up the bundle and carried it to his tent.

Then the babu resumed his seat on the pad beside Kupta, and the elephant heaved its pon-derout bulk erect.

"Salaam," called Chandra Kumar in farewell, as the beast lumbered away.

"Salaam," replied the Pathan leader, and turning, stalked to his tent.

THE babu was quite jovial as they rode back toward their own camp, joking first with Kupta, then with Sarkar, the mahout. He was very happy, for though he had forsaken the gods of his forefathers, a new god had taken their place— gold. And he found it very pleasant to contemplate the twenty-five hundred rupees which were the profits of this trip, resting his heavy money belt along with the money he had mulcted from Kupta and Sarkar. Also, it was exceedingly gratifying to estimate the infinitely greater profits yet to come from this venture.

Within a half mile of the camp, they turned down a side path and halted, it being the babu's purpose to wait there until after the raid had taken place. He and Kupta dismounted and took their ease beneath a shady tree, but Sarkar was content to keep his seat on the elephant's neck while the beast tore off leaves and tender twigs and thrust them into his huge mouth.

Back in the camp of the maharaja, tiffin was followed by the customary nap, which lasted well into the afternoon. Then the maharaja assembled his guests for tea.

For some time, as was natural, the talk was only of Jan, and the possibility of catching up with him. Naturally, all were anxious to continue on the trail as swiftly as possible, with the exception of the maharaja. But he simulated anxiety on the subject very well.

"There's no use going on," he said, finally, "until we hear from the babu. Also, we must wait for the elephants that are bringing up our baggage. In the meantime," looking at his two male guests, "I think I'll have a try for sambar. There's no fresh meat in camp for my men. And I know of a water hole nearby where the jeraos, as we call them, are sometimes thick as fleas. You probably won't care to eat any of the meat—most Americans and Europeans don't, as it is rather coarse in texture. But I think I can promise you two gentlemen some ripping sport if you care to come with me."

Don Francesco turned to Trevor. "What do you say, amigo?" he asked.

"I don't know," replied Jan's father. "I simply, can't get the boy off my mind, and if I thought—"

"Oh, go with him," said Georgia Trevor. "There isn't a thing we can do at present—and you like to hunt."

"Yes, do come," urged the maharaja. "We'll only be gone for an hour or two at the most, and will be back in camp before the babu can possibly get here. Then we'll have a good night's rest and get an early start on the trail in the morning."

"Very well. I'll go. But the ladies—will it be safe to leave them here?"

"I'll leave all my spearmen here," the maharaja promised, "and rifles for the ladies."

"We'll take only one elephant and his mahout. Rare sport, shooting from the howdah—and we may flush a tiger."

Shortly thereafter, the maharaja and his two male guests rode away on the back of the largest elephant.

GEORGIA TREVOR and Doņa Isabella retired to their couches. Ramona sat down in front of the tent to read a travel book on India which she had in her hand luggage. There was no breeze, the leaves hung motionless on the branches, and the air seemed fairly to quiver with the heat. Several times she caught herself nodding over her book, and presently, overcome by heat-induced drowsiness, she fell asleep in her chair.

When she awoke, the sun had set and a breeze had sprung up. She arose and went for a stroll about the camp. She noticed that wood had been brought in for the cooking fires, but that not one had been lighted. Puzzled, she spoke to an old wrinkled Brahmin beggar who sat a little apart from the others with his back against a tree.

"Why is it you have not lighted your fires and prepared your evening meals?" she asked.

"It is not our custom, memsahib," he replied softly. "This interval between sunset and the first glimmer of stars is the moment of silence. No one cooks or lights fires at this time. It is a sacred moment when we sit still, meditate, and listen for the voice of silence."

One by one the stars came out. A man arose and touched a match to his cooking fire.

Then, as if this were a prearranged signal, the silence was broken by the thunder of charging hoofs, and the frenzied yelling of a host of riders, punctuated by the loud reports of rifles and pistols.

Instantly, the camp was thrown into wild confusion. The elephants began milling and trumpeting, their mahouts trying ineffectually to calm them. Then one big bull snapped his tether and fled into the jungle. He was followed by another and another, until all had disappeared into the jungle shadows. The guards seized their spears and ran hither and thither, shouting excitedly.

A dozen black bearded riders charged into the camp, shouting and shooting, their puggrees streaming behind them. Others deployed to the right and left.

With frightened cries, the spear-men plunged into the jungle, leaving the camp defenseless.

Cut off from retreat to the tent, Ramona saw Jan's mother and Doņa Isabella emerge with rifles in their hands. She saw the former level her rifle at a yelling raider and fire. The raider sprang from his horse and confronted her. Again she fired, point blank at his heart. But he only laughed, wrenched the rifle from her grasp, and pushing both women aside, plunged into the tent. Another rider disarmed the doņa, and seized her by the arm, while a third, who tried to hold the fiery Georgia Trevor found he had captured a tartar. She kicked, scratched, and finally seized him by the beard which, much to her surprise, came off in her hands, revealing a scraggy, gray beard beneath it.

The first man then came out of the tent, and spoke rapidly in Pashto.

Ramona, about to rush to the assistance of the others, felt a light tug at her sleeve. The old Brahmin who had told her of the voice of the silence was there.

"Come," he said softly. "It is you they want. The others will not be harmed. Follow me. Perhaps I can help you to elude them."

For a moment Ramona stood irresolute. Then she saw the marauders release the two women. One shouted a harsh command, and other raiders began searching the remaining tents. So far none of them had seen her standing there in the shadow. Silently, she turned and followed the old Hindu into the jungle blackness.

WITH his right arm and shoulder imprisoned in the crushing folds of the giant python, and the snarling tiger charging straight for him, Jan thought and acted with that celerity which had saved his life so many times before in his native South American jungle. First he leaned far back, then exerting every ounce of his marvellous strength, hurled his burdened arm and shoulder forward. With the backward movement, the coils of the serpent had loosened for a moment, seeking a new grip. Now, the writhing, hissing reptile hurtled through the air, and its heavy coils fell over the head and neck of the charging feline.

Jan caught up the spear and sprang back, but the precaution was needless, for both of his enemies now found themselves so busily engaged with each other that their intended victim was forgotten. The tiger bit, clawed and roared its anger as it rolled over and over trying to rid itself of those crushing folds. But its terrible teeth and talons made little impression on the armored body of the reptile, only dislodging a few superficial scales.

In contrast to the lightning-like movements of the great cat, those of the serpent seemed slow and deliberate. The coils which encircled the tiger's neck tightened into a thick scaly collar. Others slid around its body, the mighty muscles rippling beneath the gleaming skin, constricting, crushing.