Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

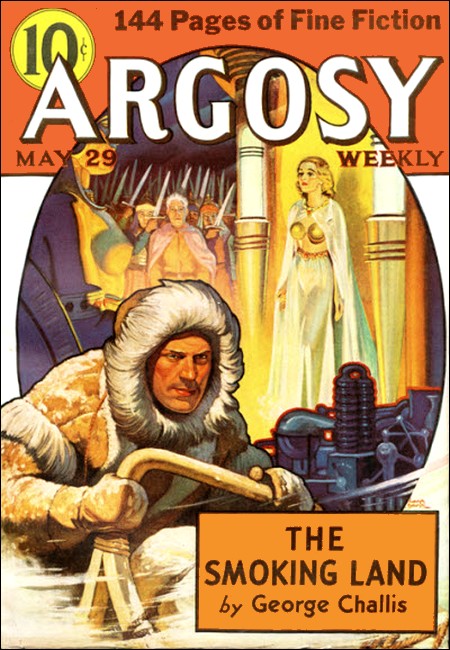

Argosy Weekly, 29 May 1937, with first part of "The Smoking Land"

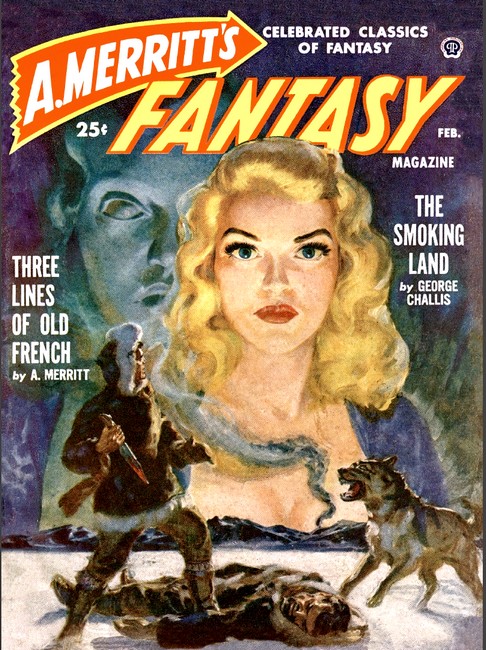

Abraham Merritt's Fantasy Magazine, Feb 1950, with "The Smoking Land"

Spectacular adventure lured ranchman Smoky Bill on a weirdy lone voyage to the world's periphery where reckless men waited to turn atomic science against the world.

THERE are plenty of folks on the Bitterroot range, from Apache Springs to Bullhide Crossing, who claim that the Cassidys, man and boy, have been liars and scoundrels and cotton-wood-bait for three generations. Yes, and not without cause, as I am the first to admit. So there's not any hurt feelings.

My own name is Cassidy—Smoky Bill, they call me mostly—and I never professed to be lily-pure. I have shot off my gun at moving targets and not all of them were coyotes. I have been a bit careless now and then about flipping my loop and dabbing my running iron. If I swore on a Bible, here and now, that I was Mahatma Gandhi or General Grant—well, it wouldn't be the first time I've told a lie.

But no man alive can say that the Cassidys aren't good men to ride the river with. No one can claim that we ever lie down on a friend.

This by way of explanation, and to account for the state of my mind and being on this afternoon when a rider clattered up outside my shack on the hill and cut loose with a bull- bellow....

There was sunset red on the far peaks and dusk was clotting at the edges of the sky. I had been dozing, and the first sound I heard was my name bawled out above the crunch of hoofs. "Cassidy—" I heard him call. "It's Cleveland Darrell wants you, Cassidy...."

I stood in the doorway and watched him climb down from a tall roan. He was a little man with a fat and hairless face and glasses on his stubby nose. A stranger, I saw, so I transferred the gun behind my back from my fingers to my waistband. He came up to me like a strutting banty rooster.

"Mr. William Cassidy?" I gave him a nod. "I am Dr. Herbert Franklin," he said. "Perhaps you have heard of me. I come to you, sir, in behalf of Cleveland Darrell."

I stood aside to let him in. "What's wrong with Cleve?" I asked.

"Nothing," said he, "but something is apt to be wrong with him unless I can find a man willing to call himself Darrell's friend. Are you the man?"

"Sit down on that chair, there, doctor," I said, "and tell me all about it. If Cleve Darrell's in a jam, then I'm your huckleberry. So speak up, man."

He sat, and his bright eyes watched me. In the meantime I was reaching back into my memory of newspapers, which have made the biggest part of the reading I have done in my life, and the name of Dr. Herbert Franklin began to seem more and more familiar. In his face I recognized the pictures I had seen.

"Dr. Franklin!" I said. "Aren't you the scientist who invented the ray that knocks the chin whiskers off of atoms and scrambles molecules all over the lot?"

He pursed up his lips. "Mr. Cassidy," said he, "I may be remembered, a bit in the future, as the man who started the experiments which a much more talented investigator carried on. I'm referring, naturally, to our distinguished friend, Dr. Cleveland Darrell."

I may have smiled a little. It was rather a shock to hear old Cleve Darrell referred to in the rather heavy manner of an after- dinner speaker as a "distinguished mutual friend," I had known Cleve well enough in the old days at district school to black his distinguished eye while he was giving me an undistinguished nosebleed. Of course I knew that he had become important in the meantime, but do what we will, we cannot be too serious about the newspaper fame of fellows we have ducked in the old swimming hole.

I said that I would like to know what was happening that made Cleve seem to be in danger.

Said the famous Dr. Franklin, "Do you know what Dr. Darrell is doing at the present time?"

"Playing pinochle about this hour, I should say," said I, "unless he's changed his habits a good deal."

Dr. Franklin cleared his throat. "I mean to say, do you know what his scientific occupation is?"

"It's something about electricity," said I. "That's all I know. Something hard to get at, and hard to understand."

"To put it shortly," said Dr. Franklin, "the goal of many men for a long time has been to release untold stores of power by liberating the chained-up energy of the atom. This means, in a word, the dissolution of matter. At least, we have no other term for it at the present time, and the idea of Cleveland Darrell is the production of a ray, whose impact upon a certain gas at a certain temperature ... but perhaps I can put it mathematically more simply still."

"You can, Dr. Franklin," said I. "You can, something tells me that you can. I knew when I laid eyes on you that you were a mathematician, or something like that. All my life I've admired mathematicians. I've admired, and revered them, but they give me the creeps."

I thought I had better explain this because I didn't want to hurt his feelings, so I said, "It's just that people are that way, or they aren't. The same with snakes and spiders. I've seen a man pick up a

spider by the legs and stroke the fur of its back. That's all right. It's quite all right if you happen to be fond of spiders. But I prefer snakes. Spiders and mathematics give me the creeps."

"Ah, yes, I understand," said the doctor.

But I could see that he didn't. In fact, he went right on. "I can make it perfectly simple, with a diagram and a few elementary equations—

"Don't do it, doctor," said I. "I know that you could make it simple, but it's no good. Just the way a fellow who has taken the Keeley Cure can detect alcohol, no matter how it's mixed up and disguised, in just the same way I can spot mathematics miles away, wearing a mask and a Spanish sash. It may promise a good time. It may look a good tie. But I spot it at once and get indigestion, and a swimming darkness before the eyes. I've been to nerve specialists and psychoanalysts, but they can't keep me from dreaming about algebra all night. Even fractions I don't like. I don't like them, don't use them, and I hate to talk about them. And a decimal point can spoil a whole day for me."

"Ah?" said the doctor. "In your case perhaps there has been a stoppage of the naturally developing—however, let that go. The difficulty is that I feel that I must give you an impression of the vast importance of Cleveland Darrell's work, and without the aid of mathematics, it is a subject which I fear can only be approached incompletely and indirectly."

"Be as incomplete as you like, doctor," said I. "As for indirectness, I'm a regular buzzard—I always fly in circles. You say that Cleve is doing some great work. I take your word for it. He's making a ray that will knock the spots out of every ray that ever rayed before. I gather that this ray will turn loose a lot of horsepower, which I understand, and equations, which I don't. So let's call it a drawn battle. Cleve is a great man and he's doing a great work. I take everything about it for granted. Now let's whittle the idea down to my own size and tell me what I can do to help."

"I take it," said Franklin, "that you're an old friend of Dr. Darrell's?"

"The best friend I ever had," said I.

Beyond the windows the dusk was creeping over the range. Lights were winking in the big ranch house below us.

"Cleve Darrell made all that possible," I told the little doctor. "I'd be just another saddle tramp if it wasn't for Cleve." I grinned, remembering. "Tell you just how good a friend Cleve was. He used to lick me two times out of three, but before he went away to college, he taught me the secret. It wasn't much—just a simple little thing—but oh, the difference to me! It was only a little uppercut that started out like an apology and wound up like the crack of a whip. The loaded end, if you understand."

THE doctor gave an embarrassed laugh, such as a man uses when

he's out of his depth and turns to wade for dry land.

"As a matter of fact," said he, "there are certain obliquities in your speech that I don't quite follow. Perhaps a little more familiarity—"

"No," said I, "study never would do it for you, Doctor Franklin. You could spend your life studying the lingo and never be clear in the use of it. It's just one of those things that we were talking about—snakes or spiders. And I gather that you're not at home with snakes."

"No," said he, "it's a matter into which I never have gone very deeply. I once wrote a little article on ophidians which—"

"Well," said I, turning a quick corner, "That's all right too. But let's get back to Cleve. What can I do for him?"

"You can protect him," said Franklin.

I was glad to get the talk down to short sentences like that. "Protect him from what?"

"From danger. I gather that you're a man of your hands—even with guns?"

"I have used my hands, doctor," said I. "Though I've seen times when I would have preferred to have a club. As for guns —well, I'm a lot more at home with them than I am with theorems and equations."

"Quite so," says be.

"But who in the world could have it in for old Cleve?" said I. "He was always the salt, and as quiet as a mouse until somebody picked on him. Then he could be thorny enough. Has he used his upper-cut on somebody who refuses to forget?"

"Uppercut?" said the doctor. "Er—as a matter of fact, not only individuals—and men of great power, too—but whole nations are interested in either stealing the results of Dr. Darrell's experiments, or else destroying him before they are completed."

"Destroying him?" said I.

"Yes."

"Murder Darrell?"

"Yes."

"But," I protested, "nations—great modern nations don't go all out to kill an individual even if he has found a new kind of gunpowder, or a way to fly to the moon."

I could almost hear the doctor shake his head. "This case is a new one," said he. "And the matter is of such vast importance that even international morals and law will be shaken to their foundations! That is to say, if the experiments succeed, and in the meantime, we have Cleveland Darrell, a man who absolutely refuses to take the slightest precautions. His own heart is so high and his spirit so noble that he declines to attribute meaner motives to others. In short, he imperils his life—which is another way of saying that he imperils the future of civilization—by refusing to take the slightest precaution. And that is why I have come to you. I have heard him refer to you affectionately, and very often. I believe that since he opened his laboratory at silver Dam he has used his hours of recreation to come hunting with you on your property."

"Yes, he's done that," said I.

"And I gather from what he says," went on Dr. Franklin, "that you are a friend who could be depended upon. Otherwise, I confess that I don't know what to do or where to turn. If I hire armed men, they will probably be corrupted by the enormous sums of money which our enemies are prepared to use, and in the most unscrupulous ways."

This began to look interesting.

"Concerning your interrupted work," said the doctor, "I could promise you on behalf of the laboratory a fee sufficiently handsome to cover, I believe—"

"Fee?" said I. "No, Dr. Franklin. I have a foreman and ranch hands down below who run my place much better without me. That's why I have my headquarters up here. Getting me off the property means money in my pocket in the long run. I'll be happy to stay around and look after Cleve Darrell as much as I can."

The doctor was delighted. He said he had been led to suspect that I was exactly this sort of a splendid fellow, and he passed out a lot more of the same sort of encouragement. However, I let that go over my shoulder.

"When do you want me on the job?" said I. "Tomorrow morning?"

"Tomorrow morning?" said he, with a sort of horror in his voice. "Mr. Cassidy, if you can possibly manage it, it would be a godsend to have you with us to help us through this very night!"

I must admit that my temperature lowered pretty fast, at that. But I said that I would come, and went down to saddle my horse.

SCIENTISTS, I've discovered, don't overstate. Certainly Dr. Franklin did not. I went over to the great dam and the laboratory which used some of the power that whirred out of the dynamos, fairly determined that I would be able to steer Cleve Darrell through that one night, at least; but I failed. My comfort is that I don't think any other one man would have succeeded.

However, I shall try to tell the details of that dizzy affair one by one. On the way over, of course I pumped Dr. Franklin as thoroughly dry as I could. I said, "There're a good many men employed about the works and in the factory, I suppose?"

"About two hundred," he nodded.

"Do you suspect that some of those men are on the wrong side?" said I.

"Yes, they are all on the wrong side, I suspect," said the doctor.

"You suspect everybody?"

"Yes, everybody."

"There must be some hardy, honest old night watchman," said I. "Come, now, Dr. Franklin. Don't tell me that every soul in two hundred could be corrupted this way!"

The doctor did not answer me at once, but bumped along on top of his horse with his elbows flopping up and down. All I can say of his riding is that it was just about what one would expect from a mathematician. Finally he said:

"Mr. Cassidy, I wish to tell you something."

"Go right ahead," said I. "As long as there isn't an X plus Y squared in what you say, I'll try to follow you. By the way, nearly everyone about here, including Darrell, calls me Smoky. That will shorten some of the things you need to say."

He thanked me, but he wouldn't use the nickname. He said, continuing, "I believe you feel that I have a friendly attitude towards Darrell?"

"Yes. I'm not able to find any other reason that could have brought you on this ride tonight. Something tells me that you're not very fond of riding."

"Ah, and how could you have guessed that?" said he.

"I don't know," said I. "I just had the idea."

"One may always admire," said the doctor, "the insight which every man is apt to show within his own province. But if you'll take it for granted that I am fond of Darrell, both as a man and because of my great admiration of him as a scientist—and if you will realize that my private fortune, in addition, has been sufficient for every need I have had in my life, then—"

He paused, and I was still as a mouse. I realized that Dr. Franklin was telling me things which ordinarily I should never have heard him say even if I eavesdropped.

He went on with a good deal of effort. "In spite of all these things, and others which bind me to act as a man of integrity, Mr. Cassidy—in spite, I say, of so many bonds, even I have been tempted!"

His voice dropped and was little more than a hoarse whisper. And I could guess, then, with half a mind, that the soul of the doctor was a great deal taller than his inches.

I pondered this thing bit by bit. "Was it hard cash that was offered, Dr. Franklin?" I finally asked.

He cleared his throat, and made another difficult pause before he answered. "The money was only a part of the offer. The other part—if you don't mind, it's a thing about which I cannot very well speak."

Of course I could not press him. But I took to wondering what all-powerful devils must be after poor Darrell when they could almost buy the soul of a gentleman like Franklin, a famous man, a wealthy man, a man of honor!

WHAT would be my price, for instance? If they could budge Dr.

Franklin, they certainly could budge me. And I wondered, with

sweat on my face, what my upper limit would be, and what besides

coin they would throw into the scales?

Things like that make long miles.

But finally we climbed the rise and saw from the divide that tarnished sheen of the water behind the dam, and the glittering of the lights that swarmed along the left side of it. Lights of a town, when one rides toward them, always seem to shift and stir about like a busy swarm of bees, and all that sense of movement was to me, on this night, a preparation of trouble to come.

We went down the slope beyond, and then up, climbing steadily, with very few words spoken, until we got to the village, where the houses of employees were stretched along regular streets, with a lot of well-watered green about them, not to be seen, but breathing out through the darkness. And I could hear the whirring of lawn sprinklers, now and then, and the thin whisper as the spray of it cut the air.

It was a pleasant moment, on the whole, but like the flowers of a funeral, all of this beauty only served to depress me, now. The quiet was the expectant hush before the fight begins.

We put up our horses in the company stables, and then went to the main building where the laboratories had been established. They had about an acre of rooms of one sort or another, all at the disposal of Dr. Cleveland Darrell, and they supplied him with money for his experiments, and besides that, he had all the immense flow of water power that the dam controlled to use for his experiments. In return, he did a nit of work for them in his odd moments. I wondered how they could afford to do it, and asked Dr. Franklin if it were simply because they were so tremendously interested in his experiments.

"The truth is," he said, "that the heads of this firm are not quite intelligent enough to appreciate the direction which his experiments are taking. They don't know how much he has in hand. But it isn't either pity or charity that makes them keep up such a big plant for Cleveland Darrell. No, he saves them in hard cash something like two or three hundred thousand dollars a year, and in addition, he's put some commercial inventions in their hands that ought to put them just about a whole century ahead of the rest of the world."

While the doctor was speaking, I took up his statements one by one and used them as measuring rods with which to estimate the mental size of Cleve Darrell, and he kept growing and growing against the horizon of my imagination until he pretty well stood up among the stars.

Of course I had known for years that he was important. But I had not suspected that he was a giant. When he was with me, he talked fishing and hunting, and such stuff, and he could be very good company both before dinner and after. But this was different. I was to see him on his own camping grounds!

We saw him very quickly.

We got up into a narrow little box of a sitting room, with seventeen kinds of odors in it, all of them bad, and a tired- looking boy took our names in, and a tired-looking little man with a week's beard on his face came out and snapped at us, and said that we would have to wait.

We asked him how long we would have to wait and I understood him to say, as he turned his back on us and went away with the white skirts of his apron flapping behind him, that he didn't know how long we would have to wait, and that he didn't give a damn.

I looked at Dr. Franklin, and the doctor smiled a little. "People who work around Cleveland Darrell," said he, "are apt to become a little tense—if they have wits enough to understand what he's doing."

We went over and stood at the window that looked down upon the galley; and there we waited for another half hour, I think. And then a red streak blinded me. No, it was more golden than red. It leaped, I think, from farther down the side of the building, and it landed somewhere on the face of the opposite cliff.

YES, we could see the spot where it landed. There was a

strange howling, roaring sound like thunder and a sick cat making

music together. And I saw a glowing spot form on the side of the

cliff and grow rapidly. While from the nether rim of that circle,

red-golden dripping flowed down the face of the cliff, and where

they reached precipitous falls and jumped through the air, they

struck again on the rock below with showering of living sparks.

The whole cliff was lighted up. It was the weirdest thing that

I'd ever seen.

As for Dr. Franklin, I thought that he'd throw himself out the window, he climbed so far and hung so over the ground. And there was a groaning in his throat.

Now the great circle of light that had been growing and growing up to this moment, disappeared as suddenly as it had commenced. And Franklin dropped back into the room, and barely managed to stagger to a chair.

He sank into it, and I, turning about, pretty well flabbergasted, was in time to see a tall figure with long, loose white arms, and a long white gown that flowed to the ground, and—a glass face!

This form stood by the door, fumbling at its head, and presently the glass mask came away and showed me Darrell.

Yes, it was the same fellow, but he had such a look on his face as I never had seen before. Dr. Franklin had said that the men who worked with young Darrell were apt to get a little tense. If so, it was a trouble that they could easily have caught from their boss. The color was out of his face, and the eyes flitted far back under his brows. He looked as though he hadn't slept for a month; but he looked, too, as if he could keep on working for another month. Perhaps that will give you my feeling about how he had been burning himself up, and how much there still remained to burn in him!

He gave us a wave of the hand for a greeting. He didn't have time for us yet.

A couple of poor devils were carried out through the door. They had fainted, and now they were rushed over to the windows and flattened out on the floor. Water was thrown in their faces. Brandy was poured down their throats.

Darrell was busy over them; his motions were quick and crisp, but heavy with strain.

The little fellow with the beard—the snapping turtle of a half hour before—was one of them; and I was rather glad of it. The other was a big six-foot-something whale of a man with a jaw like a crag. Just now as he came to he sat up, stood up—and broke out in heavy sobbing, like a baby.

It gave me cold chills to see him, but the dozens or so aproned laboratory workers—they looked more like surgeons' assistants—seemed to feel no shame for him, only understanding and sympathy. They helped him out of the room.

The little man of the beard got up next, and he walked across the room like a sleepwalker until suddenly he threw a hand up before his eyes, and winced a little, sideward, and fell sprawling on the floor again. Well, it's an odd thing to say, but I'm convinced that what knocked him flat this time was simply the eyes of Darrell, which suddenly had met his!

MIND you, I don't think that there was any malice in Darrell's look. He picked up the little bearded man with the ease one would expect from a fellow of his strength of arm and back, and handed him over to a pair of white-aproned assistants who carried him from the room. No, there was no question of personal malice. It was simply that when the little bearded man had looked at Darrell, he saw Darrell in connection with something that literally kicked the feet out from under him.

Darrell got the rest of his staff out of the room, and it seemed to me that they went like dumb cattle, looking over their shoulders at him as though they expected him to change into a grizzly, or something worse. What looks of apprehension!

When we were alone. Dr. Franklin shouted "Darrell, you've done it!"

But Cleve raised a hand at him, partly, at least, in warning. Then he came over and shook hands with me.

"I had to sweep the rest of 'em out of the room," he said. "That's why I didn't pay any attention to you at first, Smoky. Is anything wrong? What's brought you over here in the middle of the night?"

"Because," said I, "I've been hearing that the nights here are a lot too long for the nerves of some of the people at the laboratory. And I've seen enough to make it clear, all right. What did you do that turned a couple of hardboiled humans into jelly, Cleve?"

He considered me with his deep, bright eye in a way I had known in him since childhood.

"It's a hard thing to talk about," he said, very slowly. "I don't want to talk about it, either. I'll only say that both of those fellows have been working closely with me for months. They believed in me. They believed in what I was going to do. But the very thing we believe in is what may try us the most."

"I know," said I, translating down to my own level. "I never care what happens when a pair of teams go into the field, even if they're big leaguers, but when the Wyoming Wasps trot out, my heart bumps right up through the brain pan, and I get all addled. But what under heaven was that blasted loose from the side of this building?"

He gave me a faint smile, and then he turned to Dr. Franklin. "Did you see, Franklin?"

Herbert Franklin sat shaking in a chair in a corner of the room, his head bowed, his hands gripped hard on the arms of the chair. He did not look up now, but simply nodded his head, saying. "I saw!"

A wave of stifling hot air rolled through the windows and soaked through the room. There was an odd smell to it; it choked me, and set Franklin to coughing. But he jumped up and pointed to the outer night, not saying a word but keeping his eyes fixed upon Darrell.

Said Darrell, "That's it. I don't know what the temperature was, exactly. Not exactly. But I prophesy that the trees in the canyon will be dead in the morning."

Franklin put a hand before his eyes. "What else will be dead?" said he, huskily. "Not tomorrow, but afterward. It's something that no man should ever have attempted."

"If scoundrels have the say of it, no," said Darrell. "But it had to come sooner or later."

He gave his attention to me, again, but not all of it. No, most of it was still at work on something else. I knew he was contemplating what he'd done that night.

"You've come over here as a nerve specialist," said he. "What's your medicine, doctor?"

"Pills," said I.

"What sort of pills?"

"Mostly lead," I answered.

He frowned at me, and I pulled out my old Colt. "Pills that just fit this throat," said I.

"Put that up," said he, rather angrily. "Are you gunning for somebody? What's the matter with you, Smoky?"

"Nothing'S the matter with me," said I. "But I gather that there's something apt to be the matter with you before long."

He looked at Franklin, frowning. "This is your work, I know. I'm sorry, now, that I ever told you about this wild scoundrel. Bill, you get out of here and go back home.'

"You go to the devil," said I. "I've already done a day's riding, and I need rest. Ill stay here till the morning."

"All right. Only that long," said he. "Mind you—promise me that you won't take longer than that from your work."

"My work's all right," said I.

He shrugged. "You should not have bothered him, Franklin, but as long as he's here, I'm damned glad to have him."

"Raising a little crop of nerves, Cleve?" I said.

He nodded.

"Well, then." said I, "I'll sleep across your threshold and be your faithful Friday. Where do you put up tonight?"

"I put up in the laboratory," said he.

"Hold on," said I. "You've done enough for tonight. You've scared me to death, socked the cliff on the point of the chin, and killed all the trees in the canyon. Isn't that enough? For one night, at least?"

A tremor went through him, and the sight of it made me shake, too, because whatever else he was, Cleve was not the jittery sort. Nerves of iron he had, I remembered. Once.

"Franklin and you, Smoky," he said, "if I'm right, what I've done so far tonight is only the first step. What follows is so much more important that I can't mention it in the same breath!"

"What on earth can it be?" asked Dr. Franklin, and I was comforted to see that even his mathematical brain found Cleve foundering on logarithms in a deep sea.

"I can't tell you, Franklin," said Darrell. "In a sense, I daresay that it's not on earth. But I can't tell you. There are no words to fit the idea. Mind you, it's only a dream. I have to go about the resolution of it or the scattering of it all by myself. Not a soul can be with me. And that's why I say I'm glad to have someone to watch the door for me."

This atmosphere was growing so spooky that I would have called it a practical joke in any other place, but jokes don't breed very fast around a scientific laboratory. So I simply said, "Well, show me the door."

He took the pair of us at once, and the door he brought us to was a door. It was ten feet high and nearly as broad. It was opened by a purring machine that gave me the willies, and I rapped it on both sides with my knuckles. It was six inches, at least, of tool-proof steel—enough to break the heart of any egg; and beyond it there was a very long, narrow room, with heavily shaded electric lamps hanging from the ceiling at the farther end and throwing down brilliant funnels of light.

There was the usual laboratory litter of glass test tubes and such stuff ranged on the long sink affair under the lights, and big glass vases along shelves, filled with powders or liquids bright and gray enough, some of them, to stand beside the candy containers in a country store. Filling most of the rest of the space were several big iron cases that might have contained dynamos, ugly round heads they were that might have fitted monstrous bodies to scare grown men with by the light of midday. The rest didn't look menacing.

Said Darrell—and I hope you will take what he said to heart, because it has a bearing on what follows—"This is the place where I spend the rest of the night. Before morning I shall either be dead or else life—"

He stopped. I heard a strangling cry behind me and looked around—my gun in my hand.

It was only Dr. Franklin. He was gripping his throat with both hands as though he were trying to strangle himself and making a pretty good job of it. His face looked like the face of a drowning man.

"NOT that, Darrell!" said he. "Not that—in mercy's

name."

"Yes," said Darrell, white and grimmer than ever. "In mercy's name—in the name of mankind—I have to make my try before morning. Smoky, I want you to watch that door. I've shown you the key that opens it And no one must turn that key. You understand?"

"I understand," said I. "What if some callers drop in through another door, eh?"

"There's no other door," said he. "I've been planning for this night for three long years. This room was specially built. Blasted, I should say—blasted out of the naked rock."

"What about the windows?" said I.

"Look for yourself," said he.

I looked, and one look was enough. Far away below me was the dull sheen of water. I wanted to drop something and count the long seconds before it splashed.

"I'm satisfied," said I, turning back. "No one is to approach the door, eh?"

"No one," said he.

"And if somebody insists?"

"Warn 'em solemnly, twice, three times if you can. And then—"

"Well?" said I, beginning to feel really serious.

"Well," said he, "you have a gun, and not many people shoot straighter than you do, Smoky."

"You mean me to shoot 'em down?" said I.

"Damnation," said Darrell, through his teeth. "D'you understand the English language?"

It didn't offend me. No, it simply scared me to see that those steel nerves of his had been warped so taut and filed so thin. I said nothing in reply. He meant killing when he said it and I did not doubt that he had sufficient justification. Though I must say that I had a bright picture of Smoky Cassidy mounted on a gallows' scaffold with a rope around his neck and someone asking him if he had any last statement to make before leaving this sad world.

Darrell took us outside again. "You know where the key is," he said. "If so many men come that you can't handle them, just press this button—this one here. That will give me sufficient warning, and if they open the door after that—" He set his jaws, I saw the glint of his teeth. "They'll never be seen again between earth and heaven, Smoky!" said he.

By thunder, he meant it, too—plain annihilation!

Then, with a mere gesture to us, he went inside the room! I heard the door mechanism purr; and Darrell was closed away from us by half a foot of solid tool-proof steel.

I HAD a few moments to chat with Dr. Franklin after that, but I couldn't get much out of him, for he was dazed, and he still was wearing a remnant of that horrible, drowned look that I had seen on his face before.

I asked him if he had any idea what Darrell meant, and he said that he had, but that he could not talk about it.

"Why not?" said I.

His answer was sufficiently wild to make my head buzz. He shook a hand over his head, and with a trembling forefinger he pointed to the ceiling—but I knew he didn't mean to show me the ceiling. It was beyond it—the heavens—that he meant.

"Because," said Dr. Franklin, "it would be blasphemy to say even the names of rash fools who attempt to do what should lie only in the hand of God Almighty!"

And he turned on his heel and left me.

I stared after the door through which he passed for a considerable time, and then I looked around me for some way to kill time.

The room I was in was by way of being a waiting room; a number of magazines were lying on the center table. I cheered up when I spotted on one side of it a deep leather chair. I sank down into the chair and passed my hands over the magazines. In all that number there would have to be at least one detective story, and detective stories are my special meat. A dead body in the first chapter is my taste, and then suspicion all around, with the smart detective coming in when things look blackest for the innocent.

Personally, I think that it's hard to beat one of those family murders, in which the murder taint involves father, mother, brother James and sister Mary, to say nothing of the invalid old aunt. A story like that thickens the blood; I've gone to sleep with my light on, after reading one of those yarns.

So I passed my hand eagerly over the magazines, my mouth set for just the particular taste I had in mind.

But I was beaten from the start. Those magazines were not human. They were filled with reports of learned societies, and the only pictures they contained were of machines and gadgets twisted enough to make an octopus look as simple as a snail. I looked through them; one glance at any of them was enough. Then I slumped back into my chair and fell into the deep ways of disconnected, nervous thinking.

The floor of the room was trembling—and my brain was trembling, too—with a powerful, subdued humming that came from beyond the thick steel door. I linked my thoughts with that sense and feeling of electric might at work, and I began to wonder if the time might come when the machine was the man—and the man merely an inferior machine...

The click of the door yanked me out of it, and I saw Dr. Franklin come hurrying back, in his dressing gown, his feet whispering over the floor in slippers.

He waved to me. "I left my glasses in there, like an idiot," said he.

He went on towards the door.

"You're not going in, are you?" said I.

"Not going in?" exclaimed the doctor.

He paused on his way across the floor and stared at me. Then he laughed.

"Oh, I see," said he. "You're being; the good watchdog, eh? Well, that's all right, but don't bother me about it. Darrell is used to having me slip in and out at all times of day and night."

He went on to the door, and I sat back in my chair, relieved, but when I saw him reaching his hand towards the opening key, I shouted out, suddenly—a twinge of suspicion pushing my voice out.

Dr. Franklin jerked around. He was a pale but definite green, and the drowned look was on his face again. I covered him with my Colt, and I don't mind saying that the gun shook. How would you like to have your favorite dog jump for your throat, for instance?

Well, he stood there plastered against the wall, his hands pressed out flat against it beside him, while I got up and walked over to him. He did not shrink away, but merely watched me, blinking rapidly, gagged with horror.

SOMEHOW I knew exactly where to find it. I simply dipped a

hand into his right dressing-gown pocket and fished out the

thing. It was one of those bulldog affairs, short-nosed, but

loaded with full-sized forty-five caliber slugs. I'd rather be

hit by the regular bullet from the regular gun. A Colt smashed

the pellet clear through you. The dirty bulldog revolver is too

apt to just curl its slug around a bone and leave it there

somewhere inside you.

I put the gun in my own pocket I could hardly look at the doctor. I just watched his feet on the floor as he went back towards the outer door, and a very wavering line they followed, you may be sure! Not until the door slammed did I really look up.

Then I got across to my chair and slid into it, dizzy, and cold, and thoroughly sick. It had been shocking enough to hear Franklin admit, on the ride over, that he nearly had been bought up by the people "outside." I had thought that, and still think it, the most heroically honest confession I have ever heard. But now the same man, having been tempted, having confessed, had returned to the poison.

Oh, any other man, but not that little, large-brained mathematical giant, with his international reputation, and all. But I had seen with my own eyes. I could still finger in my pocket the gun with which he had walked to the forbidden door ready to shoot Cleve Darrell dead!

What did he intend to do afterward? How did he intend to get back past my long-barreled, professional Colt?

It simply meant that the price had been so frightfully high that he was prepared to commit the crime, and die for it the next second.

I was glad he was out of it, poor Dr. Franklin. No, I didn't despise him, or feel any particular loathing. I simply thanked God that whatever price had been offered to him had not been used to tempt me.

Would some grave professor with the eye of a priest and a pocketful of wisdom and diamonds, come to buy me off from in front of that door?

I told myself that no matter who stepped inside the waiting room, I would give him five seconds to step out again before I started shooting. It would be a quick count, too.

But nothing of the sort happened. Perhaps they read my brutish mind from a distance, or perhaps the look of poor Franklin's green face as he went out was enough to settle their minds about Smoky Cassidy. At any rate, I was allowed to sit through long, cold hours, while the moon rose, and the haze of it met the electric light that streamed out the window.

I wanted very much to lean out that window and drag in a few breaths of honest, Rocky Mountain, unscientific air, but all through those nightmare hours I did not dare to budge my eyes from the outer door of the waiting room.

But nothing came through it. No, the disaster came from the other direction, behind the thick steel of the door that guarded poor Cleve Darrell.

A thousand times I have tried to order and solidify my memory of the instant. It seems to me to have lasted a full minute, though I know that it must have been only a fraction of a second; but it was the hideous newness of the thing that lengthened the time. The best I can do is to ask you to try to conceive a noise that was a force, and a force that was also a light. For I heard a sound, and I felt a force crushing me as deep water crushes the body, and I knew that something ripped across my eyes, or the eye of my mind, like the gold en-crimson lightning that had streamed over the valley and struck the face of the opposite cliff.

Then unconsciousness hit me like a hammer-stroke, and I was blind and deaf. All at once, all my senses seemed to be smothered....

I CAME to with cold water being thrown on my face, and far

away voices that came quickly nearer to me, saying that I

couldn't be alive, and that it was impossible. And then another

voice, grave and calm, saying that I had stood in a node of the

explosion.

If you know what a node of an explosion is, you are wiser than I was. I heard, afterward, that sound travels in waves. And I had stood in the ebb of one of those roaring waves. Believe it if you please. I try to, but I can't I mean to say, I've seen too many explosions, and handled too much dynamite to understand the wave theory at all!

Some theory had to be dragged in, however. I realized that when I went to look at what had been Darrell's laboratory. All that was left of it was the steel outer wall, and the steel door in the center of it. Both wall and door were in waves—good, deep waves, too. It looked like a sheet of rubber, or a putty model.

As for the solid rock on which the rest of the room had been built, it was washed away. There is no other word. It was clean gone, and the raw, dripping bowels of the mountain were in plain view.

It was three days after the explosion before they let me go back to the spot, and after I had seen it, I wished that I had stayed away for three weeks—or forever.

I asked how many tons of nitroglycerine must have been used to blow the shoulder and the chest off a mountain, and the wiseacres shook their heads. Nitroglycerine, I gathered, was child's play compared with what had popped there inside the long work room of Cleveland Darrell. And not a one of the wise men had a grown-up thought as to what the explosive force could have been. Or could guess at it.

I saw Dr. Franklin, and asked him.

Oh, yes, we were on speaking terms again. He looked frightened and sick enough when I looked him up, but I said, straight from the heart:

"Franklin, whatever was in your mind earlier that night, and whatever devils got at you, I think you were through for the evening when you left me. I don't think you had anything to do with the hell-fire that broke later on. So please tell me what you think could have happened?"

He got hold of my arm with his shaking hand and thanked me for believing in him, and he told me in a dying voice that if he could dream of who the scoundrels were who had done the thing, or what means they had used, he would be the first to go to the powers of the law and accuse them. But he told me, in a dreadful whisper, that he thought the engines of Cleve Darrell's own construction must have been turned against him. By his tone, I guessed that he attributed the disaster to some superhuman agency.

But as for Cleveland Darrell, no one asked where he might be. Such a question seemed foolish. They simply built him a monument on top of the remainder of the mountain, and there you may see it to this day.

BUT while the world was forgetting Cleve Darrell, I was remembering him. Old friends die hard in my mind, and I never could forget that I had been placed on guard, that night of nights, and that the accident had happened while I was on the job—that I hadn't been able to keep it from happening.

Not that I really thought an outside hand had turned the trick. For Darrell himself, as you remember, had plainly stated that before morning he would either be dead or else—hell, something unfinished that had to do with life was in his mind, it appeared, when he ended his sentence. So it appeared plain that his experiment could easily end, in his own expectation, with disaster embracing his death. And that was what I really thought had happened.

But one's real thought, and one's sneaking inward suspicion may be quite different, and the suspicion which sometimes nudged me and waked me in the middle of the night was that Darrell had been done away with by murderers.

Nevertheless, I went on with my work, while my ranch prospered hand over fist. Then, at the end of six months came the mild newspaper sensation of the piece of wood that was picked up in the mountains of British Columbia by a tourist. No real prospector or old-timer would have paid any attention to it, but tourists are always opening their eyes and finding things out that afterward astonish the natives. For there were odd things about that piece of wood.

In the first place, drawn on it with a sharp point, were certain words, which said:

Bound north of Alaska for the Smoking Land and....

The writing stopped, there, at the end of the piece of wood, as though more words had followed when the stick was whole.

But the writing was not what had caught the attention of the wise men; it was not the writing that lodged that piece of wood in a special glass case at the Smithsonian. No, it was the nature of the wood itself, because it turned out not to be wood at all!

It looked like wood, and it had the grain of wood, and about the same specific gravity. But it was tougher than steel, and almost as hard as corundum. In fact, the wise men decided that the writing on it must have been scratched by a diamond point!

It was, it appeared, wood impregnated with some mysterious substance, hitherto never discovered upon this planet. That takes the breath, doesn't it?

No, it was not petrified pitch, or anything else that the scientists knew about. It was simply wood into which something else had been injected. The wise men rubbed off little fractions of that singular bit of pseudo-wood and put the particles in their test tubes, and incanted long theories about atoms with electrons added, or subtracted, or some such rot, or the interstices of space being filled with—well, I don't know what. You'll find all the theories in the newspapers and the magazines of the time; and it was in one of those magazines that I found the thing which blasted me free from the dude ranch and started me north.

It was simply a good, clear picture of the strange piece of wood, showing both sides; but the face that interested me was that which bore the writing. For, when I looked at it, something jumped in my brain, like a jack rabbit in the middle of a desert, and the idea kept running and running in circles around me, until suddenly it came home to me with a bang.

That writing belonged to Cleveland Darrell!

NO, not to his grownup hand, but to the sort of scratching

that he used to make in his copy-books when we were youngsters

together, and when I used to look over his shoulder and be

secretly proud of my steadier writing.

The thing took such a hold on me that I finally got hold of a handwriting expert, and showed him the photograph, and asked him to compare it with a specimen of Cleve's mature hand from a letter to me. And then I told him my memory of Darrell's schoolboy writing.

The expert was a kind man, and a tolerant man, and he considered my idea very carefully and I guess honestly. But afterward, he told me that a prepossession had got hold of me; that it wasn't strange, because of my terrible experience in Darrell's laboratory. But, he said, prepossessions ought to be guarded against because they were apt to turn into obsessions, and he advised me to take a long rest...

He clearly thought I was a little off in the head because of my belief that I recognized Darrell's hand in the scratchings upon the piece of wood found in British Columbia. For one thing, had Darrell ever been in British Columbia?

That was a reasonable question. And it should have knocked my crazy theory flatter than flat. But it didn't. I couldn't think of anything else. It got so that it came between me and everything I did or was or could be.

Finally, I decided to give way to it utterly.

Meantime, I had been asking everyone I knew about a "smoking land" lying to the north of Alaska. But no one had ever heard of such a thing, although I talked to a good number of gold-rush veterans, and to others who had mushed from one end of Alaska to the other. I got hold of books, too, and after someone told me that such a term might occur in some of the Eskimo folk tales, I dug up some of those. I found a lot of weird yarns of witchcraft and so forth, but never one small reference to the "smoking land."

Now, when a fellow has embarked on a long road, he usually refuses to admit that he has come to the end of it and found a blank wall or a falling-off place. And it was so with me. I decided that in the original Eskimo, there might be phrases which had not been properly translated. And so, to my own amazement, I found myself sitting up at night grinding away at odd books that try to give a phonetic reproduction of the Eskimo speech.

It was a hard job, but I managed to pick up a good many words and phrases; some of them I was grateful for later on. Those early studied opened my ears and enabled the actual lingo to sink in on my mind more easily when the right time came.

What I am driving toward is the moment when my preoccupation with the thought of Cleveland Darrell and the picture of that infernal piece of wood that was not wood, made me sell the ranch and start north. You will say that I should have known it was impossible for Darrell not to have been blasted into the most intensely microscopic bits, but on that one night, I was given a fairly thorough introduction to the impossible. I had seen a thunderbolt thrown by a human hand, so to speak! Besides, I never was very logical, and I think I was tired of ranching, anyway.

At any rate, I cleaned up a handsome profit on the sale of my place. I packed my war-bag and hit the trail to nowhere...

I have to take some long steps, now. It would be pleasant to talk a great deal about the great white North; and I could tell some longish tales about some of the experiences I had learning to punch dogs over the long northern trails, and the men I met.

I KEPT at it for more than a year, but by the end of that

time, I found myself at Point Barrow, back on a trail that I had

been over before—so many times, in fact, that already the

old-timers would grin when they saw me, and start passing

remarks.

My job was hopeless and bad enough, anyway, but it got a great deal worse when I came among fellows who would say to me: "Why, of course I've heard of the 'smoking land' and the way I heard of it was like this—"

And then would follow a long gag the end of which was a big laugh at my expense. They said that I won my nickname of Smoky because I had been so long in the Smoking Land. They cracked a lot of other poor jokes about me and my foolish hobby, if you can call a hungry, driving passion like that a hobby.

But nothing out of that year really matters, down to the time when my Eskimo boy, who had worked with me for three months, suddenly caught hold of the stranger who was eating beside my fire and said, laughing, and in broken English, that he had found, at last, a man from the Smoking Land!

NOW that I had been so long on the rim of the Arctic, there was nothing unusual about the scene. I remember that the land, the sea-ice, and the sky, were all one pale tone of café-au-lait. It was one of those backgrounds that make objects near at hand look big, and darker than the fact.

The dogs had been fed, and we were cooking our own meal when the stranger showed up and squatted to take his part of the hand out That's the way with Eskimo. They always have a hand out for whatever they can get. A really first-class Eskimo doesn't much mind what he receives as long as it is something. He never complains, as long as he is on the plus side of the ledger. I must say that they treat strangers just as they would themselves be treated, and if hobos could stand the cold, they would never have to do a lick of work in an Eskimo village.

I asked my boy what a village would do with a—professional loafer, and he took the matter under advisement for a long time. At last he said that if fate sent such a person among the Eskimo, the burden would have to be endured.

At any rate, I was accustomed to the begging of the northmen, and I paid little attention to this fellow, simply giving him the smallest third of our rations—there happened to be enough for all hands.

I began to notice the stranger a little more during the meal. In the first place, his dialect was one that I had never heard before during my wanderings among the Eskimo. All of that year, I had been going after the language as hard as I could, and I was pretty proficient but now and then I ran into some outlander whose talk was a puzzle to me. This chap was the worst of all.

In the second place, he had the look of a breed—about three-quarters white and the rest Eskimo. He had the bulk and the shoulders of a white man; he had the length of face, and the hollow cheeks, but I thought that the Eskimo blood showed in the size of his cheekbones, and in the rather cramped, slanting forehead. He had a white man's beard, too, something that one very rarely sees among any full-blooded Eskimo.

In the third place, his furs, which were handsome to look at, were of a cut and make very different from any that I had ever seen. The stuff looked to me like sea-otter, though I couldn't imagine even an ignorant outlander Eskimo wearing that frightfully expensive fur.

In the fourth place, and almost more important than all the other items, he had a dog the like of which I had never seen. It looked like a cross between a small polar bear and a wolf. It was a dirty yellow white—the natural color for that northern region; and it must have weighed a hundred and fifty, or even more. The head and neck were snaky, like the bear's, but it had a wolf's shoulders, and a wolf's magnificent legs.

It was on account of the dog, chiefly, that I had been considering the fellow's application for a job. He wanted to know if I was going south, and I said that I was. For I had had enough of the white land, and bucking blizzards, and all for the sake of a fool's dream.

"Bound north of Alaska for the Smoking Land," had rung in my ears for so long that I was sick of the thought of it. I was even a little sick of the thought of Cleve Darrell. Mind you, I had been very fond of Darrell; but still my reason was always telling me that he had died back there in a southern land, and the broken side of the mountain was the token and seal of his passing.

Yes, I was going back to the southland, and perhaps there I should find out the best site for a new dude ranch—no, I was tired of talking; but I would begin to be an honest man, and run cattle, and get poor again. In these days, it costs money to be honest and a hard worker!

So I told the strange Eskimo, and had my other boy translate, my firm intention of trekking south. And the stranger seemed interested. He wished to see the southland, he said, and because his desire to get there was so great, he was willing to work for very little in the way of hire. Also, he had a dog, I could see the dog for myself, and it was clear that I had no other like it, neither did any other man in Alaska have such a dog.

I asked him if his dog worked well in a team, and at this, he laughed—less like an Indian, again, than a disdainful white who knows more than you do. Rotten manners the white race has, compared to any unspoiled native.

When he finished laughing, he said that if I hitched up my eight dogs and put his white brute in the lead, his leader would pull as much as all the rest of the team. And as for food, he would eat one of the other dogs every fifth day, and so, at the end of forty days, there would be an end of the rest of the dogs, and the white leader would have cost no food at all, and the sled would be many hundreds of miles on the journey.

On the whole, I thought that this was one of the neatest little bits of exaggeration that I had ever heard.

Then he demonstrated how the dog could work, and that, I must say, was a sight worth watching. Without a word, just with movements of his head and hand, and very slight movements at that, he sent the big white beast out running over the snow, and worked him here and there, and back and forth. He stopped that dog, and sent him on again, and swung him right and left, and all the while he worked, the dog was at top speed, running with a long, swinging gallop that reminded me of the gait of a thoroughbred. Then he was brought in and gave a lick or two to the snow and lay down at the feet of his master. He was not winded by all of this running. He was just breathing easily, with his eyes half closed, as though he liked this sort of business.

Yes, that was a dog in a hundred, or a thousand, or ten thousand. I thought more of the dog, and more of the master for owning such an animal. On a long inland voyage such as I intended making, a brute of that capacity would be matchless. I leaned over and looked at his pads, and they were big enough for two. One of them was canted a little, so that the toes spread, and I saw that those toes were webbed almost to the nails! Not with a thin pink filament, but with fur-covered hide!

I still was staring at that webbed foot when I asked the stranger if his dog could swim.

"Swim?" said he. "When you come to open water, he will catch his own fish!"

I was more and more interested.

We had finished eating and were drinking tea. And I put some sugar into the stranger's tin. It was exactly as though I had fed him whisky. His spirits rose with a bound. I've seen the same thing happen more than once with people who are unaccustomed to anything but a meat diet.

When he was at the peak, I asked him where he lived. And he waved his hand to the north.

"Away out!" said he.

"But away out," said I, "there's nothing but sea ice!"

The stranger, at this, drew his head back into his neck furs and squinted at me in an ugly fashion; he said nothing.

AND this was the moment when my other boy laid hold of him,

laughing as I have said, and cried out, "Oh-ho, then he comes

from the Smoking Land! The Smoking Land!"

And he laughed again, as though his foolish sides would crack. For, you must understand, everyone who had had much to do with me in the far north was always prepared to hitch up every unusual idea with the Smoking Land. If a strange fish were hauled in on the line, it came obviously from the Smoking Land; and if a queer bird sailed through the sky, it was bred in the Smoking Land, also. I was sick of the sound of those words.

But the same phrase had an odd effect upon our stranger. He did not laugh. Instead, he showed a set of strong white teeth through his beard, and he snarled, "You say the thing that is not! You say the thing that is not!"

My boy was fairly rolling in the snow, by this time, but he sat up, gaping and choking like an idiot, now, and pointed with both hands, and shouted, "He comes from the Smoking Land!"

I was smiling a little myself, simply because laughter is infectious, not because I appreciated that stale, worthless joke.

But my smile was extinguished on the spur of the moment, I give you my word, because our stranger, in answer to that long laugh, pulled out a knife that looked as long as my arm, and made a pass for the other lad's throat.

It was not a detached gesture, either. It was followed up by a good long lunge that would have speared my boy as he rolled in the snow, squeaking like a rabbit with fear. But an accidental upfling of his arm parried the lunge and then my lad, getting to his feet, grabbed the arm with which he had made the lucky parry and ran.

I never before had seen any man run over deep snow as though he were wearing spikes on a cinder track.

The big stranger made two steps in pursuit; then he thought of a better idea. He waved to his dog, and the white beast jumped up with a little whine of eagerness, and bounded away in pursuit.

That was a good deal too much for me. Ordinarily, I had let the Eskimo follow their own little racial whims and fancies without any interference on my part, but I could hardly stand by and see a boy pulled apart by a man-eating dog. And it looked fairly certain that the white devil was not running this game for the first time.

So I pulled out Judge Colt and leveled it at him. "Call back that dog!"

He gave me a horrible squint, but without a word, he waved his arm, and I saw the dog, in the distance, come to a reluctant pause, and then swing slowly about toward his master.

That was not the end of the little parley, however. Mr. Eskimo, having his attention taken from my boy, was giving all of his most private thoughts to me. He leaned forward a little, and without a word, came straight at me with his knife.

The folly of that staggered me. The man might come from a land very far north, but he surely must have known about firearms—and there was I, covering him!

I never hated to do anything so much, but it looked like my neck or nothing. I fired a bullet straight into his breast!

I say that I fired the bullet "into" his breast, because as a matter of fact I saw where it hit, and saw him half stopped by the weight of the impact, but he wasn't entirely stopped, and he failed to drop. Also, the sound it had made was not the sickening chug of a slug driving into flesh. It was a hard, flat sound, like that made by banging a hammer on a thick board.

I was dizzy with the thought; my head spun about. But I put the twin brother of that bullet right on the spot where the first one had landed.

Yes, I saw that big brute of a man begin to laugh with a murderous fury of exultation as he sprang in on me with his arm strained back for the finishing stroke.

THERE are not many things that one can trust in this world, and I had always known it, but I made an exception in favor of Judge Colt. I had worn him next to my heart for a good many years, and if I treated him with proper care and precaution, he never failed me—never! Until then.

And it looked to be the last moment that anything on earth could be of interest to me. It was not quick thinking that gave me a moment of respite, but by a natural gesture, I threw up my gun hand to ward away that devilish knife.

There I had my first touch of luck, for the long, heavy barrel of the gun whanged the knife-hand of the Eskimo right across his mittened fingers. He brought his hand down, and it thumped me on the breast where he had intended to drive the knife home. But there was no steel in his grip; the knife had slipped out of his nerveless fingers and dropped into the crusted snow, where it stuck upright, trembling, and gleaming.

In the meantime, I grabbed him, only to find that I had embraced a round of boiler plate, so to speak. I understood, in the same flash, why neither of my bullets had gone home. Bullets are intended to bump their soft lead noses into still softer flesh, and this rascal from nowhere was wearing armor of some sort under his furs.

I might as well have embraced a barrel; but his first hug nearly broke my back. It sent a bursting rush of blood up behind my eyes so that I saw everything through a red swirl, and leaping through the crimson haze came the man-hunting dog. Oh, he meant business, let me tell you, with his beady little eyes almost blotted out by a wolfish grin, and his fangs looking almost as long as his master's knife.

I struck at him with a half-arm stroke and whacked him right between those beady eyes; the weight of his charge crashed blindly against his master and me, and sent us toppling over in the snow.

I was underneath the man, and the Eskimo got my throat in one hand and picked his knife out of the snow with the other, as calmly as any lady would pick a needle out of a big white pin cushion. All of his teeth were showing through his beard, too. And then I smashed him in the face with the barrel of my gun.

A Colt is the handiest short club in the world. The Eskimo turned into jelly and I crawled out from under the quivering, jerking mass of it to find the white dog running in short circles, holding his head down and trying to shake the cobwebs out of it.

I drew a bead on him, but I didn't shoot. Something came between my trigger finger and the trigger to stop me, because I remembered that a dog is only what training makes it, and that this fellow's savagery wasn't really anything he was responsible for. I was glad that something had stopped me.

The dog's wits cleared, almost at the same instant, and he sat down and canted his head to one side, and looked at me and at the gun in the canniest way imaginable, as though he were saying, "This is not in the book. I have to study this lesson before I can recite."

When I turned my back on him, he failed to budge, so I gathered that I was free from danger from him, at least; and a mighty weight it was off my mind, for I would rather have faced another pair of men in armor than that swerving, ponderous, lightning-fast body, with its knife-like, jagged teeth ready to snap and tear at me.

I gave my attention, now, to the out-lander, and since he was still muttering and groaning, quite unconscious, I opened his furs at the chest and my fingers rubbed against wood, or something that felt like it.

However, wood does not turn a bullet fired point-blank from a Colt.45. So I opened his furs wider and saw something that was a thunderclap in my brain; it made me feel a little dizzy.

For I was looking down on the same stuff upon which the message had been scratched—"Bound north of Alaska to the Smoking Land and...."

Yes, the same texture of wood, the look of wood, the brownish- gray color of wood—and the substance of the hardest steel! I rapped the butt of the gun as hard as I could on the face of that cuirass, and a hollow sound came back at me, but I could not see that it made the smallest dent on the surface!

But, hard as the stuff was, totally impenetrable as it seemed, I saw that small holes had been bored in it and through these holes passed a lacing of strong gut by which the armor could be taken on and off.

I UNTIED the string, pulled it loose, and then, with a strong

pull, I turned Mr. Eskimo out of his enchanted armor. When he

tumbled on his face in the snow, he came to himself with a start

and got up, staggering, pulling the furs about his open breast,

again, to keep out the stabbing knives of the cold.

In the meantime, I put away my Colt and took up the fallen knife. It was a beautiful piece of bluish-gray steel with a blade that tapered like the dripping point of an icicle. It was supple as the wind, and as penetrating as a fork of lightning. With that in my hand—and with the white dog still neutral—I stepped up close to the man from the North and said to him, in something as near his own dialect as I could manage, that if he attempted to run away, I would stick him right through his middle.

He blinked at me and said nothing, but I knew that he had understood.

"Now," said I, "you speak to me with a tongue that cannot say the thing that is not. Where did you get this thing?" I pointed to the armor on the snow. "I found it down by the shore, washing back and forth in the driftwood. I had gone to pick up driftwood for a fire. And found this."

"You have spoken, already, a thing that is not," I said. "A man does not pick up wet driftwood to make a fire. It is awash, there is a lot more of it safe and dry on the beach. Now try again, and tell me where you got this thing."

"It is clear that you are one of the wise ones," said he. "It is true that I did not pick it up among the driftwood on the beach. But I worked one summer unloading a ship at Point Barrow. And I found tins thing in the ship, and I took it away with me."

Take him all in all, he was a good liar of the hearty, natural school, one of the kind that looks you fairly in the eye and speaks out simply and bluntly—and knows not the truth at all.

There was a raging fire in me. I began to know that my strange trail was not ending in nothing. I could not put all the pieces of evidence together, but I was willing to swear, now, that there was, somewhere, a Smoking Land.

"Twice you have told me the thing that is not," I said. "The third time if you do so, I shall run your own knife through your heart and leave you for the wolves to eat. Yes, or my own dogs may have you before you are dead. And that white fellow, yonder, may enjoy a taste of you. Tell me the truth. You brought this from the Smoking Land!"

He grew smaller in a sudden jerk, as his knees sagged.

"You brought it from the Smoking Land," said I. "Tell me the truth."

"I know nothing," said he.

But his eyes were unsteady, and when a man cannot meet your glance, he is fighting a battle already more than half lost.

"You came from the Smoking Land," said I. "That's why you wanted to murder me. Because you don't want the thing known."

"He laughed at me," said he. "That is why I tried to kill him."

"I didn't laugh at you," said I.

"I was already in the madness, when I ran at you," said he. Yes, he had talent, great though unimproved talent. He was never without a word of answer.

So I took the very long blade and laid its needle point on his breast, and as he winced, I knew that the burning finger was sinking through his skin, drawing out a trickle of blood.

"You are less to me than a mad dog," said I. "So now I am going to kill you, because I have promised to do so. But I give you one more chance to live. You came from the Smoking Land!"

There was brightness and a shadow in his eyes, in quick succession, as he decided to throw himself at me, and then as he changed his mind, deciding that the knife was much too close to his heart for him to try it.

And, after that, his face, his whole body loosened and weakened. He wavered as a rag sways in a light wind, a wet, heavy rag that dangles freshly soaked on the line.

I waited, for I saw that speech of any kind was impossible to him, just then.

Finally he said, "Yes, I am from the Smoking Land! The wizards and the devils have told you! The witches have whispered it in your ear."

This was what he said that almost stopped my heart. The agony with which he spoke made me sure that he was not lying, this time. And my thought jumped back to the laboratory, and the dreadful night of the explosion, and that moment seemed to be only ten seconds, and not a whole year, before this.

And I was robed with a new strength, because it seemed to me that now I could not fail. One always feels that way when, after following a dim idea, new and sudden light strikes across the trail and shows you even a small part of truth in what you have been dreaming.

I was not through with the Eskimo. I started to pump him some more; of course I wanted to rush at once to questions about Cleve Darrell, in that mysterious northern country, wherever it might be. But I found that I had reached a stumbling block.

"I have said too much for fear of death," said the Eskimo. "But already I am dying. I can feel their hands on me, and their fire. Kill me when you please, because I shall be ready to die. To die by a bullet or the stroke of a knife is sweetness and a pleasure compared to what they will do! They will cut me in ten thousand pieces, and each separate piece shall die a separate death!"

IT was time, of course, to hold my horses. The man had more than he could stand; he was literally full to the lips with icy fear, so I stopped bearing down on him.

I secured him by tying his hands behind him with all of the knots I could devise.

For now there were the signs of an approaching blizzard, and I set to work making a snow house against the blow. I got it roughed out and completed fairly before the real weight of the wind struck us, and washed over us like a tide of freezing water. One of those northern storms has such power that to stand against the wind is really like wading through the shooting tide that races down a flume. And when I got inside the shelter, and the Eskimo with me, I was fairly contented.

If the blizzard lasted a few days, I cared not a straw. I had food enough to last both me and my dogs; I was not far from Point Barrow to get new supplies later on, and in short, I felt that I was a master of circumstance—for the moment. My captive did not complain. He lay down and turned his face to the wall and soon fell asleep.

It was like the sleep of an unhappy dog, for during hours and hours, his body would be twitching, and whimperings and moanings would come out of his throat.

Once he sat bolt upright and stared about him with nightmare eyes, his face covered with sweat. When he saw me, the fear seemed to go out of him again; he lay down and slept once more.

In the morning I would put such screws on him as never had been put on a man before. I reasoned in this way: that he was a murderer, that he had shown the will to murder and tried a very good hand with me at the game; that therefore I was at liberty do as I pleased with him, as with a creature whose own life was forfeit. In short, though this does not make good reading, I had determined to get his secret out of him, if steel could tear it, or fire burn it free!

So I sat up and watched him, until sleep began to overpower me. Then, at last, I put the knife under my body. The revolver I hung under the pit of my arm. I lay down and slept. It couldn't have been for very long.

When I wakened, I sat up with a yawn, not very much refreshed, for the air is pretty dead inside an icehouse. And outside it, where I should have to go soon to feed the dogs, the blizzard was screaming with a stronger voice than ever. I shook my head.

And then the memory of the day before, and the thought of the Smoking Land, and poor Cleve Darrell, came rushing back to me and roused me in earnest. The aches and the pains went out of me, and I turned to find my captive.

He was gone!

After the first shudder, I made up my mind that he would quite soon return. Nothing could face that blast, and few living things would care to even creep before it. He, being desperate to get away, might have tried, but a few minutes would convince him of his foolishness. I was prepared to smile when he came struggling in again, half frozen. I thought, too, of my poor bearer—wondered what had happened to him after he had fled from the dog's vicious rush, and if he had suffered much before the snow and wind and cold finally did for him.

I sat down and waited for another hour, and by the end of that time, I knew that I had lost my outlander. Wherever he was outside of the house, unless he had managed to free his hands, he was dead by this time.

There was no remorse in me for his sake, or very little. Because I told myself that whatever or wherever the Smoking Land, might be, it was a place from which this rascal had fled in order to escape from them, whoever they might be. That was why he had been so desperately eager to go south, that was why he was willing to take such low wages and throw in the services of his man-hunting dog. Yes, there must be crime behind him, a crime of such proportions that it had bounded him out of my hut and made him throw himself away in the storm.

But how I cursed myself that I had not managed to tear his secrets out of his unwilling mouth. I knew now that there was a Smoking Land to be reached. And nothing more.

So far as I knew there were merely some islands to the north, none of them a Smoking Land, and the rest of the wide waste stretching to the Pole was sea-ice. What fool would adventure blindly out on that ice, on that shifting, cruel trail?

The blizzard lasted another full day. When it ended, I went out and found, first and foremost, two of my dogs dead and half eaten; and near one of the carcasses, with the telltale red stain still about its muzzle and breast, was the man-hunting dog of the lost Eskimo.

I got out my gun, but at the sight of it the big dog simply ran a little distance and then stopped.

I almost laughed, angry and fierce as I was at the dog's idiotic notion that a gun could not kill at that short distance. But while I hesitated, it came back, whining, and then turned away and jogged off in the direction it had taken before, plainly asking me to follow. So, after fastening on my snow shoes, I trekked along behind him.

I guessed what the trail would be, and when the direction continued straight south, I knew that it was after the Eskimo that we were voyaging.

We went two or three miles before the dog stopped and scratched at the snow. There I started digging, and a yard under the frozen upper crust, I found the man from Smoking Land lying peacefully asleep, and forever.

There was no pain in his face, but a dreary, blurred, frozen expression.

There was nothing I could do except to examine his clothes and find what I could that might help me afterwards. But I found nothing at all—there was only that magnificent suit of furs.

So I took those furs.

I'm afraid that it sounds ghoulish, but before me was a trail the mere thought of which stopped my heart. And if this man had come from the Smoking Land, probably I would need just such body covering to keep me from freezing on the way. I took the furs, therefore, and when I had stripped him, I found, exactly in the center of his breast, a mark that looked like a rudely shaped M.

It was not a very old scar. It was puckered blue, but it had the look of a cut that had been made within a few months at the outside. And I took to wondering what that letter could stand for.

M could stand for month, or merry, or a lot of other things. But in English speech it would generally stand for murder.

And that fitted In with my own guesses about him.

SO I went back to my team gloomy and grim. My problem was beginning to be more and more complicated. Had this man been branded for a crime—and driven out from the Smoking Land to perish? Was it only by chance that he had managed to make the mainland?

But, if that was so, what manner of people were they in the Smoking Land—who practiced the use of the alphabet as civilized people know it?

It was another puzzler, and perhaps because it came on top of so much other mystery, it seemed to me the most confusing and heartbreaking problem of all.