RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

Adventure, August, 1937, with "The Saint"

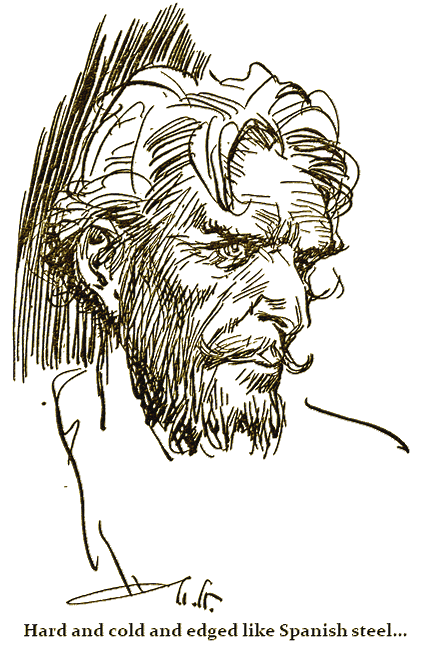

HE was smiling continually, with such an air of removal above the concerns of ordinary mortals, with such an upward lifting of the head, that his fellows in the boat had called him, from the first day of labor and thirst, "The Saint."

By the second day they used the name rather in irony than in praise, for they observed that the smile of The Saint—or "Saint George" as some called him—was merely the veiling of a nature bright and hard and cold and edged like Spanish steel.

He was far from a handsome man, for he had a long face, strong in the cheekbones and the jaw like some pharaoh of early Egypt whose portrait comes to us by a sculptor who knew his ruler was a god and therefore endowed him with the greatest strength of flesh and bone, together with the quiet cruelty of an immortal. At a glance, he seemed an old man, for his blond, sun-faded hair made a silver contrast with the ingrained and weathered darkness of his skin. He was not above middle height, but seated on the rowing bench, with only the weight of his shoulders and the flowing power of his long arms visible, his bearing still made him seem loftier than his fellows.

Except for a single rag of cloth, he was as naked now as he had been three days before when he left the piece of wreckage and climbed like an active sea-beast over the side of the canoa. Whatever his ship's name—and he was silent about it—he was the sole survivor. No doubt the vessel had been flying before the same hurricane that had whipped and staggered the Mary Burton across the Gulf of Mexico; no doubt it had smashed on the same reef that ruined the Bristol ship; but the light canoa, sliding over the teeth of the rocks that sank the Mary Burton, had picked up thirty of the crew of the big merchantman and then, ten leagues beyond as the storm died, the sea gave them this single relic of a dead ship.

He had with him only one item from the wreck, and that was his rapier, which lay now on the floor of the canoa between his feet. For three days the long arms and the hard hands of The Saint swayed an oar, while thirst whitened his lips and fixed the smile upon them, for the sea had spoiled the water which the canoa carried. In the three days he did not speak three words, but his silence and his labor and that sword between his feet had won the respect of his rescuers.

Even Captain Harry Dane, who commanded the canoa and to whom men were merely so many hands to level guns or to hold cutlasses, looked upon The Saint with a considering eye, and so did Harry Dane's crew. There were twenty of them and hardly two of one nationality, but all were strong, all were lean and fit for trouble as hungry cats.

If they were cats, one could imagine what mice they expected to catch at sea. In the reign of jolly Charles II, even the merest landlubber would have known what to think if he had seen, slipping among the islands or along the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico, a fifty-foot boat hollowed by fire from the trunk of one enormous tree, manned by a nondescript crew, with a single light cannon in the bow, and plentifully supplied with long-barreled muskets, pistols, knives, cutlasses, and axes. He would have said: "Here is a precious group of those sea-devils and man-quellers, the buccaneers—and God have mercy on my soul!"

These fellows had looked with wonderful scorn on the human driftage which they had picked from the waves. More than once, during the three terrible days of sun and thirst, they had seemed about to pitch the rescued back into the sea from which they had come; but now all the men in the boat, from the Mosquito Indian in the bows to the least of the men of the Mary Burton, were on their feet agape and staring. Some rubbed their dry throats, and some held out their hands as though to invite the mercy of heaven, and into the reddened eyes of all came a bright glimmer of hope. For over the edge of the horizon, blue as the sky but glinting with white like a cloud, loomed a big three-master, hull down, and laying a course well south and east of the canoa.

"Down, down!" shouted Captain Harry Dane. "And spring on the oars, every man of you. Maybe she means silks and wine for all of us and pieces of eight in every man's purse. Maybe she means that our voyage is made, but at the least she means a cask of water!"

Now their lives lay in the grip of their hands and the strain of their own backs. They bent the oars and set them groaning. They pulled with their heads dropped on their shoulders, their eyes blind, their lips stretched until they cracked to the blood, and the light canoa began to leap on the waves like a fish.

"Steady and easy!" roared Harry Dane. "She sights us! She turns to us! She changes her course! Elia, what do you make of her?"

The Italian left the sweep at which he was working and stood up to peer from beneath his hands.

"She don't sit down in the sea like an Englishman," he said. "Her sails are cut too loose and full to be a Frenchman. She's a Spaniard, signore."

FROM fifty throats came a groan of misery. The rowing fell away to a futile

splashing of the water. And The Saint, as he looked toward the blue-white

sails of the stranger, leaned and gathered his rapier into his hand.

After that, he sat up again with his head lifted and the usual faint smile on his lips. A grown man might not have seen a difference in his look, but a child would have known enough to be afraid. The groan of the seamen, in the meantime, turned into a pitiful babbling of complaint. Only the buccaneers, those sea-cats, were silent, sharpening their eyes to study the stranger. For these were the days of Sir Henry Morgan, when a hundred years of hatred between England and Spain had come into a fine and poisonous flowering, with special detestation blooming in the West Indies and along the Spanish Main. On sea or dry land, it was English dog to Spanish cat, and if the stranger made out that a majority of the men in the canoa were blond Englishmen, he was apt to give them bullets instead.

"Can we take her?" ran the murmur through the canoa. "Could we rush her and take her?"

For the Spaniard was not a fighting sailor. Spanish pikemen were the best infantry in Europe, but they were out of place on the swaying deck of a ship. They might fight with the greatest individual courage, but usually in a blind confusion. Mighty odds of Spaniards had been conquered by savage handfuls of sea-rovers.

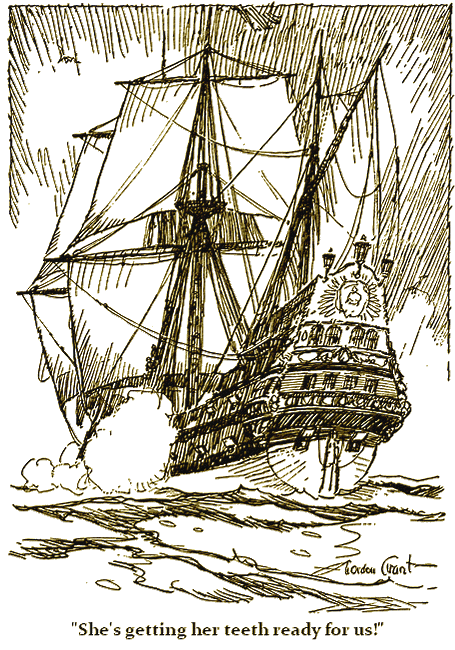

But now as the stranger approached nearer, with a freshening wind to harden her sails, the men of the canoa saw long rows of gun-ports, and the masts climbed higher and higher into the sky. She was a great-bellied galleon with a crew of hundreds aboard her, no doubt, and massive ordnance behind those ports. She was of the style as dear to the Castilians as their mountain castles, with huge fore and afterworks towering above the deck. The portholes began to open along the near wall of the ship; a moment later a huge flag unrolled from the head of the mizzen, showing the colors of Spain.

"She's getting her teeth ready for us," said Captain Harry Dane. "Down with all the blondheads on board us. Down with 'em. Fall on your faces and stay there. Up, Juan Martinez, and talk for us."

A tall Spaniard rose in the canoa and stepped forward into the bows. Harry Dane, dark as a Latin himself and too handsome for any wench in a seaport to resist, remained beside the Spanish buccaneer.

"If there's a man on board who knows my face, I'll get a noose of rope instead of a swallow of water," said Juan Martinez. "But I'll try her. Haloo-o-o!"

A swarm of sailors had gone up into the rigging, and in the lower shrouds stood various gentry to look at the little vagabond of the sea which was rowing near them. As the hail of Martinez rang over the water a big, gray-headed man by the port bulwark of the galleon called in answer: "What ship are you?"

"The Santa Elena from Cartagena!" shouted Juan Martinez. "Eight days out and three without water or the mercy of God on the high seas."

The side of the ship rose like the wall of a house, sloping well back because the Spanish shipwrights believed in plenty of tumble-home. Their vessels rode high, answering their helms slowly and never making a point close to the wind, but though they tossed like corks, they were almost as unsinkable. Witness the great Armada, where the Spanish ships died on the rocks, but not under English guns.

The gray-headed captain bellowed back: "This is the Santa Teresa, of Cadiz, bound home, Captain Juan Xi-menon—" He changed from Spanish to English, calling: "What is it you will have from me, my friends?"

The sound of that friendly language brought not one, but half a dozen hidden blondheads above the side of the canoa, shouting as with one English voice: "Water! Water, for God's sake!"

Captain Harry Dane turned on the fools with his cutlass like a bit of trembling white flame in his hand, but the harm was done already.

The Saint clearly heard Captain Xi-menon say to the officers about him: "I thought I could smell English rats on our clean Spanish sea. Kindly sink that boat for me, Don Jose."

"Back water! Back water!" shouted The Saint, speaking almost for the first time in three days.

The men sprang back on the oars, cursing and wild with fear, for they could see grinning Spanish faces inside the lower port-holes, and the busy aiming of the guns.

The Saint heard the word to fire, and the roar of the heavy guns was enough in itself he felt, to knock the little canoa out of the sea. But a lucky wave at the right moment put its heaving shoulder under the side of the Spaniard and rolled up the muzzle of his guns, so that the shot merely tore overhead with a sound like rending sheets of canvas. Only one gun struck home.

The ball, smashing through the canoa from side to side, knocked one headless corpse overboard and left two other good men writhing in a red smother of blood. But now the way of the great ship carried her ahead and left the canoa wallowing under her stern, where only two cannon looked through the square portholes.

THEY had the helmsman in view, high above, pulling at the spokes of the wheel

as the great ship commenced to wear, leaning with the wind, eager to pour in

the second broadside. The Saint picked up one of the long barreled muskets

which lay under the gunwales and shot the helmsman through the head.

"Well shot, by God!" roared Captain Harry Dane, as the strain of the rudder-chains spun the wheel back and let the ship straighten before the wind again. "Now get the gunners at those stern chasers. Joe Hatch—Gonzales—Johann-sen—Mirza—some of you sharp eyes begin drawing beads and keep the hands off that wheel. If we can't fight her side to side, at least we may be able to hold her by the heels. Fight or die, damn you! Up hearts and down with the Dons. Watch the rigging. Help me tilt up the cannon!"

The men from the Mary Burton took little part in the fighting that had started, but the buccaneers fell to work—not with a cheer but with a frantic and savage yelling like a pack with the fox in sight. Chance had placed them, in fact, in exactly the strategic position. More than one great Spanish ship had been worried to death in just this fashion when there was not enough wind to let her maneuver out of the jaws of a small boat that hung on her traces and picked off the helmsmen as fast as they offered themselves at the wheel.

The buccaneers, men who had learned that it was either straight shooting or death in more than one battle, now steadied their fire through the portholes of the stern chasers until The Saint could see shadowy figures leap or fall beside the guns. And the helm itself could not be manned.

More danger came from the mizzen rigging, where a crowd of musketeers had climbed up to the fighting tops, and to the yards, from which they commenced to open a furious fire on the canoa. Five men died in the small boat almost at the first discharge, but Captain Harry Dane had already prepared an answer. For he had elevated the muzzle of the short, wide-throated cannon at the bow of the canoa and filled it to the mouth with a heavy charge of powder and musket-balls. Now the master-gunner, that Mohammedan renegade, Mirza, lay flat to sight the cannon. Now it fired. The recoil ducked the nose of the canoa almost under water, but a stinging shower of death whipped the entire mizzen. Men fell from their places like apples from a wind-shaken tree; and some hung helplessly in the rigging, screaming, while huge red stains dripped down across the sails.

Even the men of the Mary Burton, by this time, had learned the game. Battle was bred in their English blood and bone, for one thing, and after all, the trick seemed simple.

Now two men appeared high on the poop, dragging a sea-chest which they placed behind the wheel before the musket fire from the canoa dropped them. Two more brought a second chest.

"Watch them! Watch them!" shouted The Saint. "They're building a barricade for their helmsman!"

After the first shot he fired, he had reloaded his long gun and remained leaning on it, at wait for another emergency. It had come now; quickly leveling the musket, he brought down one of the two Spaniards and the second sea-chest was left on the deck. In that emergency, the captain himself, now equipped in a heavy steel helmet and body armor, ran up and laid hold on one end of the chest. The other end was grasped by a second man in armor, a magnificent youth with long, dark, curling hair that blew aslant in the wind. Between them, they swayed the sea-chest into place, and in this manner a barrier was raised behind which a helmsman could stand in safety. From every throat on the canoa went up a tingling screech of fear as the Santa Teresa swung with the wind, answering her helm.

The Saint stood by Captain Harry Dane.

"Dying on the Santa Teresa is as good as dying in the sea," he observed.

"It is!" agreed Dane. And as the yelling of his men died out, and only the cheering of the Spanish came roaring down the wind, he ordered the canoa right in against the stern of the galleon.

There was no wincing from that decision, for it was plain that in ten minutes of maneuvering with rudder and sails, the big ship was certain to bring a broadside to bear, and one volley would end the canoa. So, buccaneers and English sailors, they strained at the sweeps and brought the slender craft sweeping in under the high wooden battlements of the Santa Teresa's stern.

The Mosquito Indian buried his harpoon in the wood and lashed the two craft together, and the little tide of men washed up the lofty slope, catching at finger and toeholds. So, in a moment, they were up at the boarding nettings that screened the rear bulwark of the ship on the high poop. Made of tough rope woven in a net, hardened almost to metal by boiling in tar and pitch, the nettings could very nearly turn the edge of a chopping cutlass, but not the straight, short sword which Captain Harry Dane carried.

HE and his men knew the system. On either side of him, men clung close and

thrust with half-pikes at the faces of the Spaniards, while Dane cut through

the nettings and opened a door to the deck of the ship, as it were. The Saint

was the first man to step on the boards. He fell with his first step, as

though a bullet had brought him down, and rolled in among the stamping feet

of the Spanish. When he rose to his feet he had shortened the rapier and was

stabbing at the bodies of those around him. That was how the entering wedge

was driven, and buccaneers came flooding into the opened space.

There was much confusion on the Spaniard at this time, for while those on deck realized that the pirates had begun to board them, the men at the guns between-decks had only just heard that the ship was manned at the helm again, and they had barely begun to cheer the good tidings.

The gallant captain had rushed instantly to the point of danger with his long, straight rapier held above his head, shouting: "Santiago and St. James!" but a Maltese ruffian with one eye brained him, gilded helmet and all, with a single ax-stroke.

That made the Spanish recede in a wave and gained half the lofty poop for the buccaneers. What stopped them from sweeping it clear was the same brilliant youth in the half-armor who had helped to place the second sea-chest to shield the helmsman. He fought as though he loved battle, and laughed as he swung a heavy Spanish broadsword. He nearly lopped an arm from the shoulder of an Englishman, and cut another through the brain-pan to the eyes. Behind him, the Spaniards began to rally fast.

The Saint, after his first entry into the battle and the first surge forward of the buccaneers, had slipped from the thick of the melee to observe matters from a little distance. This picture of the handsome Spaniard fighting like a hero seemed to please The Saint. He kept smiling with much more genuine pleasure than usual until he heard the muffled whine of trumpets beneath the deck and knew that the gun crews were being summoned away to meet boarders.

The time, therefore, was short; unless they swept the top deck of the Santa Teresa promptly, they would be worn down by fighting multitudes. The Saint slipped like a snake through the press, engaged the tall young Spaniard, and instantly had the point of his rapier through the right arm of that enemy. The broadsword dropped to the deck, and pressing in closer, The Saint struck his man between the eyes with the pommel of his sword. The big Spaniard fell on his face.

After that they won the entire poop—it was about a third of the entire length of the ship—at a stride, and stood forward looking down into the maelstrom which whirled without order in the waist of the Santa Teresa. All the forward works were black with men, who had opened a fire on the buccaneers aft.

Here that same Mohammedan devil of a Mirza took a hand. There were two small deck cannon mounted on the poop-deck, and these he turned down on the milling throng in the waist. Musket balls crammed those guns to the mouth, and the discharge of the cannon spread out the dead and the stricken in two fan-shaped patterns of red. The buccaneers came in behind this bloody stroke in a wave, shouting that the ship was theirs, and the Spaniards believed them. For just as every English sailor, in time of battle at sea, harked back to a thousand instances of invincible English valor, so very Spaniard that sailed the ocean could remember sad legends of defeat and disaster on shipboard, when it seemed that the hands of the saints were turned against them. These poor fellows, in a dreadful panic, turned and poured down the hatches to the safety of the lower decks, though they were not safe between decks, of course, for he who ruled the top deck controlled the brain of the ship.

In a few moments the waist was cleared, except for the dead and the screeching wounded, so that the Spaniards who manned the forward works found themselves cut off from the help of their companions. Of the Spaniards gathered forward there must have been five or six score, quite enough to change the course of the battle and sweep the buccaneers overboard, but already the taste of defeat was deep in their throats. The Saint sat with his arms folded, amidships, and watched the last of the defenders disappear through doors and windows.

Ten minutes after the attack began, the top deck of the Santa Teresa and the management of the great ship was in the hands of the buccaneers. There were on the galleon three hundred and seventy-five souls. At the moment of the attack, there were forty-three buccaneers able to bear arms. Yet they lost only seven more souls in boarding the Santa Teresa.

Tales of victories over far greater odds were in the mind of The Saint as he sat on the cask and listened to the screaming of the wounded, and then the pitiful complaints and the begging for mercy. The sight seemed to bother him more than the sound. He took tobacco from one dead man, a pipe from another, and presently he was smoking contentedly, and looking out to sea.

ALL was done according to old custom and unwritten laws. The wretched

Spaniards, cooped in the dimness between decks, gave up to despair at once.

When they were summoned on deck with their weapons, they came in droves to be

disarmed, plundered to the skin, and returned below deck. A score or so were

allowed liberty to become slaves of the new masters of the ship. They had to

work the sails, wash the deck, and even help in carrying the loot into the

waist of the ship, where the drinking already had begun. Two casks of brandy,

two casks of red wine, another of white, had been broached. The more thirsty

leaned and drank from the kegs and walked off, wine dripping over their

wounded, naked bodies; presently all was gaiety and laughing carousal.

For the prize was very rich. Gold from South American mines and pieces of eight as fresh and bright as the morning, sewed up in little leather bags by the patient hands of Indian women, were heaped around the foot of the mainmast in an astonishing pile; and there was massive gold and silverwork done by native artists, particularly one twenty-pound golden bowl intended for the king's own table service. There were whole bales of lace and silk, caskets of cut stones, and bags of uncut jewels. As for the spices in the hold and the log wood from Campeachy and the rich paintings on the cabin walls and a thousand little treasures, the buccaneers left them all to be evaluated by the thievish merchants at Port Royal. Around the mainmast they heaped only the valuables whose worth they understood, and according to sea-law they commenced the division instantly.

It was at this point that The Saint turned on the chest and regarded the deck scene again. He became aware that except for one rag of cloth he was naked; for beside the heaped up loot, sat a blue-eyed girl, all golden shine and beauty like an Italian painting. The Saint yawned and drew again on his pipe. He began to clean his rapier, tardily, wiping it free of sticky blood with the greatest care.

Captain Harry Dane took charge of the procedure as one who knew all the sea-rules perfectly. He stood on a heap of bar silver, piled like cordwood on the deck, and called out: "In silver, the value of a hundred and fifty thousand pieces of eight. In gold, two hundred and forty thousand—"

A yell of delight from the buccaneers.

"In jewels, another two hundred thousand; in lace, silver and gold work, and odds and ends, fifty or sixty thousand pieces of eight. Afterward we have the sale of the cargo and the ship at Port Royal, but now we have six hundred and fifty thousand pieces of eight, or Harry Dane is a liar and never saw Lancashire. For the dead and living, fifty-one in all. Fifty-one shares to start with. Who says no to that?"

Mirza the Moslem said: "If you feed a bone to a dead dog, still it cannot chew the meat."

"It's the sea-law," said Harry Dane. "The dead share with the living. They've all left a mother or a father or a brother or a friend, here or there."

"Except Barto," called a voice.

"Right," said Harry Dane. "Barto was a beast and not a man. The sharks have him now, and we have his share."

This caused much laughter and good feeling.

The captain added: "Someone go forward and knock that grunting swine on the head."

A Spaniard lay by the foremast, sick with his wounds and groaning with every breath he drew. Elia, the Italian, went forward and struck him through the base of the skull with a short hand-axe.

The Saint continued to smile. He glanced toward the girl and saw that she had pressed shuddering hands against her face. He smiled again. And glancing off to the side, he marked where the brave young Spaniard lay, that officer who had fought so gallantly on the poop. He was propped against a coil of heavy rope. Dried blood streaked his face from the blow with which The Saint struck him down; but he had made a bandage to staunch the bleeding of his wounded forearm. His helmet was gone and his dark hair flowed back across his shoulders. Except for the bigness of his features, he possessed almost the beauty of a woman.

The Saint refilled his pipe and looked into the west at the low-lying green of an island; he narrowed his eyes to enjoy the beauty of it.

"Now for wounds, who speaks?" the captain was asking.

"Jack-Martin lost a finger," said one. "A forefinger."

"That's two hundred pieces of eight," said Dane, readily.

"It's the only finger left on that hand," said Martin, calmly holding up the mutilated stump.

"Four hundred, then," answered the captain. "Who else?"

"A thumb," said someone, holding up the hand with the raw stump to prove his claim.

"A hundred pieces," said Dane.

"It's on his right hand," argued some one.

"True. A hundred and fifty pieces," said the captain. "Arms or legs?"

"Covetski has lost his left arm at the shoulder," said someone.

"Five hundred pieces," said the ready captain. "Wounds?"

"I'm cut through the calf of my leg," said one man.

"A cat scratched you, maybe," said Dane. A good, loud, brutal laughter followed this. "I mean, wounds that cut tendons or cripple a man?"

"I've lost half the end of my nose," said a thick voice.

"There's less of your face left to wash," said Harry Dane. "Who else? Nobody? Then who gets extra shares, beginning with your captain. Speak up, men."

"Ten shares for our captain," suggested someone.

"Too much," said another. "He did well, but ten shares is too much. Six shares is enough."

"Call it eight," suggested Dane, "and we'll save time and argument."

A general grunt expressed the assent of the crew.

"Who else gets extra shares?" demanded Dane.

"The Saint," said several voices, speaking together above the clamor.

"Right!" Dane agreed. "He drew the first blood for us, stepped on deck first, made room for some more of us, and dropped that Don Enrico, yonder, the junior captain of the ship. How many shares to The Saint? How many will you have, Saint George? Five?"

"As good as fifty," said The Saint. "It's all a man can carry about with him."

THEY rumbled and chuckled over this, and voted The Saint five shares on the

spot. There were no others to claim extra rewards except Mirza, who received

an extra half-share for his expert gunnery.

There was a total, therefore, of just over sixty shares, and the loot already on hand would provide the enormous booty of some twelve thousand and more pieces of eight per man, the living and the dead, except the poor dog Barto.

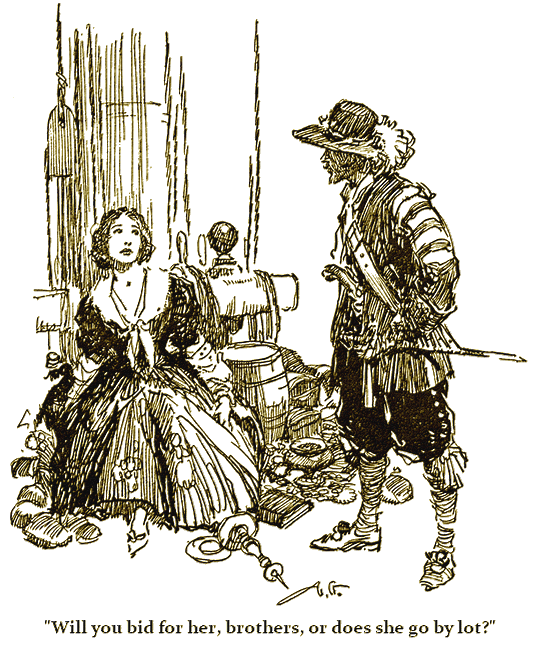

"Divide now," called the captain. "Here are the scales. But first there's one thing left over that's neither gold nor lace nor brandy nor wine. There it sits with the rest of the loot. Will you bid for her, brothers, or does she go by lot?"

"By lot," said several voices. "Everything by lot and by vote like true Brothers of the Coast!"

"Here's a bag of odd coins," said the captain. "Now I pass it around and every man takes one. The value of it doesn't matter, but the oldest date on it will give the woman to the lucky man. Señorita, what is your name?"

He stood over her, with his legs well spread, his fists on his hips, and his leering eyes fixed upon her, body and soul.

"I am Alice Morison," said the girl.

The Saint slipped from the chest and stood up. He gave her one glance and sat down again.

"That's an English name," said the captain, startled. "Are you English, my girl?"

"Yes," said Alice Morison.

The captain turned to Don Enrico, who watched with a high head, intently, all that went on.

"Is she English, in fact?" asked Harry Dane.

"She is English," said Enrico.

"Betrothed to one of the Spanish rats on the ship? Going to Spain for her marriage?" suggested Dane.

"English, unmarried, and unbetrothed," said Don Enrico. "Her father befriended my father in England; and so—"

"If she's English, she goes free, by God," called a hearty, drunken voice.

"No!" growled the chorus. "All the loot for all of us, and none held back."

"The vote's against you," said Harry Dane. "She goes to the man with the earliest date on his coin. Look, all of you, and sing out."

The Saint looked at his draw. It was a penny as bright and clean as the morning, and dated 1673. Then he heard the bawling voice of the one-eyed Maltese yelling: "I have it! 1589! Who has an older coin that that? Step aside and let me have her! Sweetheart, the look of you is better than cold beer in my throat. Lift your head, my lamb. There's only one eye in my face, and I'll swear it can see you better than any other man's two."

The Saint touched his arm.

"What'll you have?" snarled the Maltese, turning suddenly.

"I'll give this penny for that gold piece," said The Saint.

"Am I the fool, or are you?" asked the Maltese.

"You have the look, brother," said The Saint, smiling upon his man.

The Maltese was not a man to waste words and explanations. With one continuing gesture he pulled a knife from his belt and jabbed it back-handed at the naked belly of Saint George. There was no time to shrink to one side or the other or to give ground. The Saint attempted neither movement. He simply gripped the wrist as it jerked toward him and stopped the glistening point of the knife a half inch from his flesh. His right hand held the sword point at the throat of the Maltese.

"Brother," said The Saint, "if you are a wise man, you will see how much better this penny is than the gold piece. Gold is soft stuff and time will rub it away, but your good, hard copper will outwear half a dozen lifetimes. Will you let me buy it with the penny?"

"May your soul—" began the Maltese. But then he changed, adding: "Take the coin, and be damned. Does she go with it?"

"She does," said The Saint, and stepped cautiously out of range of the knife, with the gold coin in his hand.

A full-throated roar of laughter applauded this maneuver of Saint George, but the Maltese, looking from the copper coin in his hand to the face of the girl, suddenly snatched a pistol from the belt of the nearest buccaneer. He managed to fire it, but he had the sword of Saint George through his throat before he could aim the gun. For the Englishman had caught his rapier close to the guard and flung it like a deadly little javelin, all flash and steel, and no haft. It ran right through the neck of the Maltese and he fell on his back. When The Saint calmly stepped to him and drew out the sword, the stricken man began to kick and twist and tie his body into knots, stifled by the flow of his own blood. He got to his feet and ran with his hands before him and his dreadful face across the deck. When he struck the rail, in his blindness, he toppled over the edge and they heard his body plump into the sea below.

"There is an extra share for the rest of you," said The Saint calmly, wiping his sword. "Why don't you give me a cheer, boys, for putting money in your pockets?"

THE buccaneers had regarded this fracas with unmoved quiet, merely admiring,

in an impersonal way, the skill of The Saint with weapons. He was now washing

the blood of battle from his body with a bucket of water, and having whipped

off the wet with the edge of his hand, he picked out some clothes from the

heap of finery which lay at the foot of the mainmast. He did not bother about

shoes or stockings, but he drew on some linen and then stepped into a pair of

black knee breeches with silver rosettes at the knees, and pulled on a plum

colored jacket of velvet.

He was engaged in this manner, and then in combing his hair and viewing himself meticulously in a handmirror, as the captain said: "That was a good trick. He handled that sword the way a Mosquito Indian handles his fish spear. But I wonder if it wasn't murder? Let me have voices, brothers. Shall we thank Saint George for the dead man's share which goes to us, or shall we hang him up to the yardarm as a foul murderer?"

He posed the question with a most perfect indifference, and a general murmur answered: "Why, Saint George is a good fellow. We needed him in the attack, didn't we? He helped us then. And what was the Maltese except just another pair of hands?"

But there was a half-breed Portuguese called Juan Cedra, with enormous shoulders and the head of a child, and a complexion like unrefined molasses. He stood up and pointed a vast arm toward The Saint, saying: "If you like him, tell me who he is? He speaks French, Spanish, English, Italian. We took him naked out of the sea; we haven't even the name of the boat he sailed in. He came like the devil, with his sword and himself. I saw him when the shot smashed down three men and threw blood on him. He went on smiling. I saw him in the fight and he was still smiling. I say he may be the devil or the devil's servant. He may be a witch!"

The crew turned serious attention on The Saint for a moment, and he, stepping out in front of them with his pale hair and his dark face, still continuing to buckle the light rapier to his belt, lifted his head and turned that undecipherable smile upon his fellows.

"What am I, brother?" he asked. "Will you hang me?"

"Whatever else he is, he's a gentleman," said Juan Cedra, "and he's the only one among us. A good cutlass or an honest axe is right in the hands of most of us, for a fight, but he goes through like a wasp, stinging fighting men to death. He pricks you to death with a needlepoint. Hang him at the yardarm and see if the devil his master will break the rope! The Maltese was a very good man!"

Captain Harry Dane looked from The Saint to the girl and ran the tip of his tongue over his lips.

"Speak out, men!" he called. "How will you have him? In a hangman's noose, or a free man to use his feet and hands as he will?"

Mirza was pouring wine into his belly from a two-handled cup. He stopped drinking to say: "There are twenty score Spaniards on this boat. How many hands have we to keep them down?"

There was a general growl of assent to this.

"You're a free man, then," said the captain to The Saint. "But mind you, we're watching both your hands. Keep them out of hellish work."

The Saint drew his rapier, saluted the captain, saluted his fellows right and left, and slid the blade home in the sheath again. He favored them all once more with his smile. Then he went to the girl and said: "Follow me!" and passed on aft, down the deck, spinning his hand and catching again the broad gold-piece which carried the profile of Philip II of Aragon.

At the lift of the quarter deck, he passed in among the cabins which were reserved for officers. The captain's cabin, as spacious as a tavern room, he did not pretend to, but entered a starboard cabin big enough for comfort, furnished in carved hardwoods, from the large bed to the writing table affixed to the wall. The port light let in a cheerful stream of sunshine on the rich hangings of the bed, and on a little square of a hunting tapestry that decorated the wall. The figure of a saint in painted stucco filled a little niche in the opposite wall. Of course all was in disorder, for the looters had been through the cabin and wrenched out the drawers of the cabinet, overturned chairs, pulled the drawer from the writing table, overturned mattress and bedding, and knocked a litter across the floor.

The Saint began to gather up this confusion from the rug, and as he jammed part of it into a drawer of the big chest, he saw that the girl had entered and was standing near the tapestry, watching him with great eyes. He went toward her at once, slowly, with his head back and that peculiarly inhuman smile. His coming pressed her with invisible hands against the wall. She grew stone-pale. Even her lips lost their color and became a faded purple.

The Saint, when he was close to her, paused, surveyed her for an instant, and then bowed and lifted from the floor a handkerchief.

"You dropped this," he said, and she took it in her blind, trembling hand.

The Saint turned away to the table, saying: "I'll leave you here. You see the room ahead needs some attention? Afterward I'll come back to see how you are. And here is something to keep you company."

He laid on the table a small pistol, but with a bore so large that it promised a deadly discharge. Then he left her, while the bewilderment was still in her face and the color had not yet returned.

THE Santa Teresa sailed softly on toward far-off Port Royal, while the revel in the waist of the ship ran higher and higher. In spite of the warm weather, some of the buccaneers could not help loading themselves down with finery. They buttoned themselves into velvet longcoats, crammed their calloused, swollen feet into shoes, and put on be-laced and be-ruffled shirts, each worth half a year of their ignorant labor. There were not three thoroughly sober men on deck, and yet a full two score of Spaniards were at hand to manage the sailing of the ship. The Saint found Captain Harry Dane drinking wine out of a golden chalice and said at his ear: "Call 'treachery' and 'to arms', and see how many of our fellows can stand!"

Harry Dane stood up and bellowed: "Boarders away!... Treachery!... The ship's lost..."

Twenty men, perhaps, gained their feet, and most of these were staggering; the rest merely stirred uneasily in their drunken oblivion.

Harry Dane flung the golden cup away with such violence that it clattered over the deck and into the sea. A Mexican who loved his art had spent a year in the shaping of that chalice.

"You're right, Saint George," said Harry Dane. "We'll have to get drunk and watch, instead of being drunk all together. Throw that bucket of water over me to wash some of the haze out of my brain. Mirza, get up, you pig. Send the devil out of your wits and be a man. Here's a rope-end for you. The next man that drinks himself stupid, lay the rope on him till he bleeds! Who's aft to keep the helm? If we sail at random, the only port we'll ever make will be the mouth of hell. Now, hearty my lads, rouse up the sleepers. Douse them with water! Roll them down the deck. Beat the sense back into them. Swine are no sailors!"

Those who could stand began to torment the sleepers at once, and buckets of salt water in five minutes had spoiled a thousand pounds' worth of finery. In the midst of that gambol, The Saint returned to the cabin and tapped at the door.

"Who is it?" called the girl. "It is I," The Saint answered.

A silence answered him for an instant; then he heard the inner bolt being drawn. The door opened. She stood away from it, watching him with big eyes and her pale, intense face. She kept one hand behind her, and the pistol was no longer on the table.

"If you're afraid," said The Saint, "I'll stay away longer. But you should not fear an Englishman, even at a time like this."

"It's not fear of you," she said. "It's a sickness of dread that won't leave me... Come in. Take this chair in the sun, and then if I can thank God and you for—"

"Don't be a silly child," commanded The Saint. "How old are you?"

"Twenty-one," she said, frightened again.

"Look at me," said The Saint. "Am I a Spanish cat or an Englishman?"

"An Englishman," she answered.

"Then be ashamed to be turning red and white all the time," said The Saint. "You're as safe with me as though you were my sister... No," he decided, "that's a lie. Every man is a beast. If you were to look askance at me and smile; if you were to use half the everyday manners of the ladies of Whitehall, God knows what would happen. But in the meantime, I am your servant." He managed to bow to her without rising.

"God bless you," said the girl, with tears in her eyes.

"God never has," said The Saint, "but perhaps you have His ear."

SHE looked up suddenly and crossed herself.

"Tell me a little about yourself," he said. "First let me give you this assurance: When we reach Port Royal, I'll see that you're kept as safely in that hell-hole as a jewel in silk until I put you on a good ship for England. But tell me, first, what sort of a person you are. Open the door and come outside. It's a lovely evening."

She folded her hands together and looked down at them.

"You feel it's your role just now to be overcome by the fighting and the bloodshed that you've seen," said The Saint. "But don't plague yourself with the desire of all women, which is to be what they think the world expects of them. They put on a dozen faces in a day and are so busy arranging their features this way and that, that they have no brains or time left to speak with. Isn't that true?"

"I think there is truth in it," said the girl.

"As a matter of fact, why can't you relax altogether? In the hands of buccaneers, you're safer than you ever were in the hands of the Spaniards."

"Safer?" she cried, amazed.

"For a Spaniard," said The Saint, "is the favorite contrivance of the devil. The Spaniard walks like a man, talks like a man, breaths and eats and sleeps like a man, but still there's no humanity in him."

"Do you think the Spanish are mere beasts?" she asked.

"There was an Englishman once in the town of Seville," he said. "Do you know the saying: 'Heaven, or Seville in April?'... The Englishman was there in April, and he spent his days in a prison, with his body tied so that he couldn't move, and all of one day water dripped on his forehead until it seemed to beat the flesh away, and eat through the bone, and get at the brain. At last he went into a raving madness and screamed and said a good many foolish things and a good many shameful ones. I think he begged for his life. I think he promised to recant... And when he escaped with his life, he promised himself to hate the Spaniards the rest of his days, to spend the rest of his years hunting down the Spanish as a cat hunts down fat mice. Do you understand?"

"You are the man?" she asked, watching him with parted lips.

"If I could see them wiped from the face of the earth—" he mused. "The most wretched slut in London streets is a sacred creature compared with the finest lady that ever watched an auto-da-fe in Spain. The meanest English beggar is a saint compared with the most glorious nobleman in Spain. You are a child and cannot understand these things as they are."

"No," she said, shaking her head and speaking faintly. You were tortured by them?"

"I think, in fact, that you don't hate them at all," said The Saint. "You're rather fond of them, aren't you? Their soft manners, and their dignity, and all that? And that fear which is still in the back of your eyes—is it on account of some Spaniard on the ship?"

She was silent, staring at him.

THE Saint nodded, and then he laughed and leaned back in his chair a

trifle.

"A romance!" he said. "I can see it. And of course a Spaniard would love you, as he loves a roast of little singing birds. A delicate body with room for a great heart in it. Blue eyes of the sort that could weep great tears. Ah, but a Spaniard would enjoy wringing the happiness out of your soul. He would take years to do it, and enjoy the taste to the last morsel. And yet on this very ship, I saw today a man that seemed worthy of almost such a woman as you. The young man, the tall fellow with the long hair, and the beautiful dark face. He fought like a brave man."

"Enrico Morello?" cried the girl, suddenly. "Don Enrico?"

"So?" murmured The Saint, leaning forward in his chair and resting his elbows on his knees as he watched her. "Is he the man?"

The girl could not speak, but her lips kept trembling with words which she was afraid to utter.

"Don Enrico, tall and proud, Don Enrico, noble and true?" said The Saint, smiling his smile. "What will you say if I promise to be kind to him, with his wound and all? Will that make you happy?"

She was out of her chair and on her knees in front of him before he could rise. She had her hands crossed on her breast and her head raised and her eyes melting like some Italian painting of an adoring angel.

"Ah, but will you? My kind, my generous—"

"Stuff and nonsense," said The Saint, shrugging his shoulders and then lifting her to her feet. "Don't be hysterical about him, even if you love him. I made you a half-promise before. I'll make it a whole promise now. I'll do what I can to keep him out of trouble."

She caught his hand in both of hers and bowed over it. He snatched the hand away.

"Come, come!" said The Saint. "That's not very English, is it? As a matter of fact, there was something damned manly and heroic about that Don Enrico when he was fighting. He looked like a statue of a hero, and that's why I'll help him... But tell him not to be a fool and weight himself down with helmet and armor. Speed, speed is the thing!"

As he spoke, he made a few slight motions that flowed from foot to hand, as swift as the striking of a cat's-paw and the subtle shoulder movement that goes with it.

"Truth is," said The Saint, "I saw him step in and stand over one of his men who had fallen, and sweep aside three cutlasses that were about to cut him to the teeth—"

"He would always risk his life!" cried the girl. "When I was only five, I remember how he snatched me away from the bull. I still can see the gilded horns of the bull and hear the people shouting—"

She stopped herself, as though suddenly her breath had deserted her. The Saint, with his head back and his ironical smile, continued to watch her.

"It's no sudden romance," he said. "You've known him since you were children, eh?"

"His father... a friend of my father," she said. "And they would visit us, you see."

"His father, taking the little boy into a land where people would eat Spaniards, if that were the only way to get rid of them," commented The Saint. "Brave father, brave son! And gilded horns? Gilded horns, did you say?"

"There was a country fair," said the girl.

"I can see the white of the lie in your face," said The Saint. "Saved when you were five—and a bull with gilded horns, and people shouting—. What were they shouting? 'El Toro! Bravo el toro!'"

She went back from him until her shoulders were against the wall.

"Don't do that!" exclaimed The Saint. "Don't look as though I've laid a lash on you... It was this Don Enrico who said you were an English girl. What is he? Your husband?"

"He is my brother," she whispered.

"I can believe it," said The Saint, slowly. "Except for the different color, it's the same sort of rare beauty. Except that there's courage in him, and in you there's only—a Spaniard!"

She put her handkerchief to her mouth and swallowed. The Saint drew in a breath through his teeth.

"A sweet little blue-eyed'English girl, as safe with me as a sister. Bah!" he said. "I'm half a thought from putting hands on you. Whatever's clean in the world turns foul when it's near a Spaniard. But I made you a promise to see to this Don Enrico, and promises are things that I keep—better than I keep money!"

He turned on his heel and left the cabin.

When he reached the deck, he saw Captain Harry Dane standing with arms akimbo, looking over the world which he had so greatly mastered that day.

"Was it a charm, that gold coin?" asked Harry Dane. "Is she already smiling and happy?"

"Charm? In this?" said The Saint.

He took the golden coin and spun it into the air. Where it fell he did not look to see, but walked on, slowly. Captain Harry Dane picked up the spinning little glitter of yellow and laid it flat on his palm. The date was 1589, and the heart of Harry Dane spun in a flickering as dizzy as the spinning coin a moment before. He was not a man to wait for his fortune when it was in his hand; he turned at once and went to the girl's cabin.

THE Saint went forward, climbed the great square forecastle, strong as a tower, and stretched himself on the deck, where the heave of the sea swung him as in a windy hammock. There, lying face down, he fell asleep instantly. The wind blew almost a storm without wakening him. The night stilled. The dew fell and drenched him. Still he slept until in the small hours of the morning he roused at last, yawned, stretched, and got at once to his feet.

They were sailing over an easy sea, with the yards braced up a trifle and those clumsy Spanish sails rounding out their bellies in the wind. In the whole build and sailing of a Spanish ship there was something middle-aged, soggy, far removed from clean-limbed and active youth.

Looking aft, he saw that devil Mirza at the wheel, and a dozen of the Spaniards here and there, ready to receive orders for the handling of the sails; but the wind was so steady and the course so easy that not a rope had to be touched, hour after hour. Now and then the great latten yard on the mizzen swayed with some motion of the ship and uttered a deep, human, groaning sound. In the waist, aft of the place where two of the boats of the Santa Teresa stood in chocks, lanterns were lighted, in defiance of the law of the sea, and here a round dozen of the buccaneers were gathered with the towering bulk of Captain Harry Dane among them.

They had been playing cards, which still were scattered around the edges of two tarpaulins. But now they had a far more interesting occupation, which was the torment of a poor devil of a Spaniard, whom they had triced up by the thumbs. One man swung a rope's-end and with it flogged the prisoner across the naked belly. Every few strokes, when he paused, Harry Dane stepped closer to ask a question, but the Spaniard, apparently, was obdurate. And the flogging recommenced.

The Saint went down into the waist and, when he came close, saw that it was Don Enrico whom they were torturing. The wound in his right arm, where the sword of Saint George had stung him, had opened again and let a red stream all down his side; and the rough of the rope's-end had torn the flesh about his stomach. But even now, as the rope fell on him again and again, the face of Don Enrico remained not convulsed with a manly effort to endure pain, but perfectly calm and still. He looked up as though, like a good sailor, he were studying the leech of the sail and watching the wind.

The fellow who swung the rope's-end flung it down and stood back with an oath.

"Some one else take it," he said. "I've tired my back swinging it, and the dog of a Spaniard pays no attention to it."

"Ah, brother!" said the captain to The Saint. "I picked up the coin you threw away and tried to pick up the girl along with it, but by God she put a pistol under my nose and would have fired it, too, to judge by the way she showed her teeth. I talked to her as I never talked to a woman before, but I could not budge her. She acted like a cold saint or a fool in love. So I asked her, and she said it was true. She loved whom? Why, she loved The Saint! You!"

"Did she say she loved me?" asked The Saint, with his smile.

"She swore it. And of course I could not bear down on her if she belonged, body and bones, to a shipmate; but I thought when you threw the coin on the deck that you were throwing away your part in her also."

The Saint said nothing. He continued to look, with interest, on the upturned, stony face of Don Enrico, and the powerful muscles which robed the wounded body.

"We found out from one of the Spaniards," said Harry Dane, "that we had missed one prize worth half the rest of the cargo—a little bag of pearls which this Enrico Morello had on board. So we're asking him, patiently, where he may have put it. As you see, he won't give us an answer. Can you suggest another way of tormenting him? We have tried twisting a knotted rope around his head, but even when his eyes were starting out, and the knots began to cut through the flesh into the skull, he still would not speak."

"Slivers pushed under the nails and then lighted, they are very good things," said The Saint. "In Spain they are much used, I believe. But this man is about to die, and that will end the torture and the pearls at one stroke."

"About to die?" said Harry Dane. "A third of our profits would die with him, undiscovered! Cut him down, Teobaldo! The Saint says that the scoundrel is trying to cheat us and take his pearls to hell with him."

THEY cut down the Spaniard and would have allowed his loose, helpless body to

fall unregarded to the deck, but The Saint stepped in and took the weight of

it over his shoulder. The plum-covered velvet coat, already a-streak and awry

with the wet of the dew, now was bedabbled with the blood of the Spaniard, as

The Saint carried Don Enrico aft and into the confusion of an unused cabin.

There he laid the body on the bed and stood for a moment looking down into

the grim eyes of Don Enrico. The Spaniard said:

"Why did you stop them, señor? You knew that there was still plenty of life in me. But they might have ended it for me then, instead of taking it in parcels later on."

The Saint lifted the head of the Spaniard; from a bottle of cognac he poured a big dram down his throat. Enrico Morello coughed, gasped, and then lay back on the bed with heightened color and a more living eye. The Saint left the cabin and entered the galley, where he found a very surly cook.

"How are you, brother?" asked The Saint.

"Not as well as you," said the Spaniard. "For I haven't a new skin."

Even buccaneers could not daunt the spirit of this independent fellow. The Saint asked for hot water.

"There it is on the fire," said the cook. "And you have a sword to take it, or else I would give it to you with my own hands till you were stewed like a fish."

The Saint therefore mixed a bucket of warm water and carried it back to the cabin where he had left Don Enrico. He brought some lard also, and after he had washed the wounds he eased them with the grease and with torn strips of cloth made bandages. Another swallow of cognac left the Spaniard even able to smile.

"Why have you taken this care of me, friend?" he asked.

"Perhaps because there's no point in torturing a man about to die," said The Saint. "Perhaps to save you for some clever hands to work on tomorrow."

Don Enrico shook his head and smiled at the ceiling. It was an after-cabin, looking directly out on the streaming wake and the ship's boat that towed there, wavering from side to side in the moving current. The moonlight struck through this large, squared port aslant, moved on the floor as the Santa Teresa swayed with the waves.

"My friend," said Enrico Morello, "if they had not your sword, they would never have carried the ship. But now I think you are half sorry that they won. Yet it was barbarous for the big guns to fire into the canoa. Whatever your mind may be, will you tell me how it is with the English girl?"

"She has a cabin to herself, and a pistol to keep her alone," answered The Saint.

"Ha?" asked Don Enrico, lifting himself on his elbows.

"I am the only man among our people who knows, at this time, that she is your sister," said The Saint.

Don Enrico, after staring for a wild moment, lowered himself again on the bed.

"Do I understand you?" he asked.

"You do not," said The Saint. "If I've helped you, it was not for her, but because I wanted to know how you could endure the strokes of the rope's end without howling." He pointed to the black, swollen thumbs of Morello and asked: "What did you keep in your mind when the pain was the worst?"

"I kept seeing the blue Mediterranean through garden trees," answered Don Enrico. "I heard my mother's voice singing in the shade, and saw the bald head of the priest shining in the sun, and I felt the hand of Alicia holding mine; as though we were children again. It seemed to me that I had had happiness enough, and even if they lingered me out for a month, I still would be glad of having lived."

"You lived in the south of Spain?" Near Barcelona? Near Seville, perhaps?" asked The Saint.

"Our winter house is on the pitch of the slope near The Alhambra," said Enrico Morello.

"The blue face of the Mediterranean," mused The Saint. "The trees, the garden. And there was once a bull with gilded horns, eh?"

"Did she tell you about that?" murmured Don Enrico, smiling again. "That was a near thing to dying!"

The Saint went to the open port and leaned there, smelling the sea and watching the red stain of the ship's lantern from above entering a mist which had thickened until the boat astern was no more than a sliding shadow behind them. The moonlight was gone from the cabin and only the yellow, trembling flame of a wall-lamp illumined it.

He left the cabin and tapped at the door of the girl. When she heard his voice she pulled the door ajar, slowly, letting the pistol look out at him beside her frightened face.

HE was angered. He said: "Put the damned, silly pistol away, will you?" And

before she could move, his hand flashed like a cat's-paw and snatched the gun

away.

"Now be in another panic," said The Saint, gloomily, as he stepped into the room. "Or take a deeper breath and get better sense in you. The pistol is only a token, and tokens do very well with a brute like the captain, but there are other men to whom the token is worth nothing. Señorita Alicia, stop cringing in the corner like an eight-year-old baby and step out to speak to me like a woman to a man."

She glanced toward the saint in the niche and stared at The Saint in the flesh before she came slowly out to him.

He took her in his arms, and though he held her as lightly as a thought, he felt her body shudder.

"You anger me, Alicia," he said.

"I know that I'm only a Spaniard to you," she answered.

"And therefore—?"

"And therefore I'm afraid."

"You see, my dear," said The Saint, there's enough beauty in your face and loveliness in your body to drive any proper man half out of his wits, but there's also such a combed and brushed and washed and handled look, that I see a whole procession of tutors and governesses and dancing teachers and riding masters fading away behind you, and the shadow of your mother's hands is never done blessing you—"

"Yes, señor," she said.

"Is there any sense in that sort of an answer?" he asked.

"No, señor," she said.

"Now, you see, I'm holding you closer," said The Saint, "but in spite of that you will repeat after me: He is my friend in whom I place an absolute trust!"

The Saint, having ended, waited for a moment, looking at the dim swirling of the mist beyond the port. When he had no answer, he became suddenly aware that she was looking up to him, silently. Something in the gravity of her face amazed him. He could not read her expression at all.

"I cannot say it," she answered.

"You cannot?" asked The Saint, turning cold as steel.

"I cannot say it," she answered. "And it is not because I am a damned Spaniard."

"It is because, instead, I am a damned Englishman? You cannot say that you place a perfect trust in me?"

"No, my friend. It is not enough," she answered. And he became aware, suddenly, that the mystery behind her gravity was no less than a smile. Such a smile, in all the days of his life, The Saint never had seen before, there was such sweetness and mockery in it, such scoffing and affection, such carelessness and mastery.

He tried the word again in his mind and found it perfectly apt. Mastery! In fact, she looked upon him with such an air of hidden amusement that he became a little child again, dimly remembering the detestable snickering of half-grown girls, with voices rattling together like toys.

Bewilderment swept over the mind of The Saint. He drew back from her the third part of a step.

"It is plain that you now are without fear of me," he said.

"Yes, señor, I am without fear," she said.

He could not help looking past her, almost as though he expected a row of armed servitors to be standing there, sword in hand. It seemed to him that her surety could not be based upon a smaller security than that.

"And the change is sudden," he said.

"As sudden as a stroke of lightning," she said.

"I am relieved," he said, stiffly.

"No, señor. You are angered," said the girl.

"Angered?" he replied.

"It is easy for one of a base nation to anger you," said the girl, still irrepressibly smiling. "How can you be near a proud, cruel, subtle, devilish, wicked Spaniard without anger and without reaching for your sword, as you do now."

"I was not reaching for it," said The Saint, gnawing upon his nether lip. "I was merely resting my hand upon it."

"Alas, señor, I have wearied your very hands," said the girl. And she laughed again. "But I anger you more and more and I shall not speak again."

"You anger me in a strange way, Alicia," said The Saint. "There is anger, and a certain deliciousness, also. Like a sour wine, cold and old and perfect. As for the Spaniards—"

"They are beasts," said the girl, "and I would not have you think of them."

"In the name of God," said The Saint, "will you tell me what you have in mind?"

"I cannot," she answered, taking possession of his eyes and searching into them with a miraculous impertinence.

"Why can you not?" he asked.

"Because you stand too high above me," she answered.

A vague and sudden glimmer of understanding came upon him, and he fell on one knee before her and held up hands which almost but not quite touched her.

"Am I low enough now?" he asked. "Alicia, what is in your mind?"

"You are too far beneath me, now," she said, laughing again. But she came closer to him and took his face between her hands, running her fingers over the sun-faded, close-cropped hair, now like silver in the lamplight and against the darkness of his skin.

A sort of agony broke into the voice of The Saint as he cried to her: "Alicia, you don't know me. I am a man who has—"

"—sailed the seven seas and fought men and loved women and hated Spaniards, and stormed the high decks of the Santa Teresa," she said.

He closed his eyes, but he could feel her bending above him. He tried to draw her to him, but his hands would only touch the silk of her dress.

He thought to himself: "She is but a baby. I must not..."

And then he knew that he had uttered the words aloud, softly.

"But these Spaniards are such deceitful creatures and so dangerous that you cannot tell about them," said the girl. She kissed him. "And in fact there are enchantments which only the Spaniards know. Deep and desperate wiles and stratagems." She kissed him again. It was indeed like an enchantment, for joy held him stone-still.

"This is a great, strong spell which my mother taught me how to weave," she said. "And her mother learned it from her mother, and she from her mother. It is not yet complete. If you wish to save your soul from a dark bondage, señor, spring to your feet and flee from me, or else, surely, I shall have your soul forever."

He could at last look up to her and he began to laugh, a sound so strange on his lips that he himself was amazed by it.

AFTERWARD, he took her into the after cabin to her brother, and closed the door quickly. But the thin edge of her cry of joy still went like an invisible sword through and through him. He was still standing there, listening to the inarticulate, happy bubbling of the voices when he sensed or felt or heard something stir behind him.

He reacted to it with a sudden step that took him across the passage way, and the broad blade of the cutlass fell past his dazzled eyes like a cataract of water, and he saw the convulsed face of Mirza with the lips grinned back from the teeth with the effort of the stroke.

The time was too brief and the space was too close for the drawing of a sword. The Saint used his hands instead. He jerked an arm around the neck of Mirza; behind the Arab's head he caught his own projecting wrist with his left hand, thrusting up with his shoulder and pulling down against the leverage of his arm at the same instant, so that the chin of Mirza was forced violently back. And into the small of Mirza's back, at the same moment, The Saint jammed his knee as he leaped on his man.

A bone cracked, distinctly, a dull sound and a jarring sense, as though a small stick were wrapped in soft cloth and broken between the hands. Mirza spilled upon the floor. It was not like falling. His head dropped between his knees.

When The Saint tried to lift the body, he could hear bone-ends gritting together.

He pulled Mirza into the next cabin and stretched him on the floor. The man was in such agony that he rolled his eyes back into his head, and through his set teeth a froth sucked in and out with his breathing.

"Why, Mirza?" asked The Saint.

The Arab gave him one glance of hate and rolled his eyes up again.

"Who sent you?" asked The Saint.

He had no answer, and for a moment, silently, he watched the sweat of pain form and run on the face of Mirza. Then he picked from his belt a small dagger which he had picked up on the ship, a mere thorn of steel, sharp as a thought.

This he held above the eyes of Mirza, the hilt down, keeping the danger of the blade delicately between thumb and forefinger.

"Who sent you, Mirza?" he asked. "Or was it your own thought?"

The eye of the Arab looked on that release from pain with enormous hunger. He reached a slow hand up toward it.

"Harry Dane... he hates you... the girl..." said Mirza.

The Saint put the hilt of the dagger into that fumbling hand; then he left the cabin; and as he closed the door behind him, he felt rather than heard the blow strike home against the hollow of the chest. Mirza had left pain far behind him.

IN the after-cabin, he found the girl still on her knees beside the bed of

Don Enrico. They held hands and laughed together softly, as though they were

afraid that God himself would envy their happiness.

The Saint filled his pipe and lighted it. He sat back to content himself in the midst of a cloud of his own making.

"On this ship," he said, "an hour ago I seemed to be at least the second man on board. Now I'm one of the least. The captain has begun to hate me and wants my blood. The three of us must leave the Santa Teresa."

He puffed on the pipe again through a silence.

"Let us pray a little first," said the calm voice of the girl, "if we have to walk the waters afterward."

"Those pearls of yours are simply a lie and a legend on the ship that the sailor betrayed you with?" asked The Saint.

"They are not a lie. There is a great double-handful of them," said Don Enrico. "They are in a hollow panel at the left of the door of the second cabin forward. But are you telling me, my friend, that you, who led the attack and were the edge of the knife they drove home through us—that they are denying you now?"

"I have spent too much time away from them, since we gained the ship," explained The Saint. "So I have become a mystery. The sheep in the next field has become a wolf. Besides, the captain has a special reason for hating me."

He went into the forward cabin. His tapping fingers located the hollow panel at once and he smashed it with a blow of the sword-butt. From within the niche, he took out a bag of soft leather. Stones of an oily smoothness rolled inside the leather beneath the tips of his fingers. He carried the treasure back to Don Enrico.

"It is here," said The Saint. "And now, hardly ten miles away through the mist, lies Havana off our port bow. Would an Englishman be safe there under the conduct of Don Enrico?"

"But the governor is a dear friend!" Don Enrico cried.

Here a hand beat at the door. The Saint got to his feet. From the table he picked up a horse-pistol and stuffed it into his belt.

Three half-drunken buccaneers came crowding through the door.

"What is it?" asked The Saint.

"The Spaniard," said one of them. "We'll take him back now, and try some new devices on him. And the woman's no more than his sister, Saint George. A damn Spanish wench with Spanish lies in her throat—and you so soft with her."

They laughed in his face.

"We'll use our hands on Don Enrico in the morning," said The Saint. "There's so little life in him now that one squeeze would put an end to him."

"We have the captain's order, and by God, we'll bring him," said a fellow with greasy moustaches adrip from his face.

The Saint played with the horse-pistol.

"In the morning, brother. In the morning," he said.

It seemed for an instant that they would rush him. But one said: "Why should we be the only ones clawed by the tiger when there are thirty more to help us? Let's tell Harry Dane what the high gentleman says!"

They went out of the cabin in a rush of revengeful eagerness.

The Saint, turning to the white-faced pair, said to them: "There's a boat towing astern. Here!"

He leaped into the port, reached far out, and pulled down the tow-line.

"Hold this," he directed, giving it into the hands of the girl. "We need a little time, and I am going out to get it. In the meantime, the two of you slide down the rope and get into the boat astern. There's a small mast in it. Rig the mast and have the sail ready. Adieu for a moment—."

"Wait!" cried the girl, as he reached the door.

He waved to them and spilled from the bag of pearls enough to cover the palms of one hand. Then he went out, hearing Enrico say: "There are only moments to act in. There is no time for explaining. Do as he says—"

By the time The Saint reached the waist of the ship, he saw a full score of the buccaneers gathered about the lights at the foot of the mainmast, figures gross and dim in the mist. Even the voice of Harry Dane, haranguing them, seemed to be blurred by the thick weather. And then, as he came nearer, someone cried out: "The Saint! He's with us!" and the speech of the captain ended.

THE Saint walked straight on with his head high, and his smile from old

Egypt. On either side faces turned savagely toward him, and he had a sense of

hands reaching for weapons, or lifting as though they would strike him down.

It was the running of a gantlet, and if he paused or lost face for an

instant, he knew that he would be lost. So he moved steadily, with that high

head, until he was before Harry Dane.

The captain, giving up all pretense of friendliness, folded his arms and said in a loud voice: "I send for a damned Spanish prisoner, Saint George, and you drive the men away from you. Are you turning into a Spanish rat yourself?"

"I've an answer here in my hand," said The Saint, lifting a hand high above his head, and turning his smile from side to side so that all of them might see it.

"Ten pounds to a shilling that The Saint faces the captain down," said a drunken voice, distinctly.

"In my hand! In my hand!" laughed The Saint. "For all of you to see. You talk of torturing the truth out of a man too weak to hold up his head—so weak that every breath he draws may be the last one, who would die under the torture before he could tell you what you want to know. But I, do you hear, have talked part of the truth out of him, and before the morning I'll know the whole secret!"

"To hell with words," said Harry Dane. "Let's see what miracle you've got in your hand."

"Look, then!" shouted The Saint; opening his hands gradually, he allowed the big pearls to drop out one by one.

The buccaneers stared with dropping jaws. Then they scrambled on the deck for the prizes.

"They're real! They're pearls!" came the shout.

The Saint turned and strode through them.

"And in the morning," he called, "I'll have the rest safely! Patience, brothers."

So he had almost gained the entrance to the quarter-deck when he heard Captain Harry Dane shouting: "He has them now in the pockets of his coat. Catch him, lads! Catch the fox before he makes fools of us all. A Spaniard! The girl has made a Spaniard of him!"

"A Spaniard! A Spaniard!" they shouted, and bare feet pounded over the deck toward The Saint.

He ran back down the passage, reached the aftercabin, slammed and bolted it behind him. The cabin, he saw with a leaping heart, was empty.

Already the pursuit crashed against the locked door as he leaped into the after port and saw, beneath him, the boat like a phantom in the mist and the towline swinging far out of his reach to one side. He leaped for it, gained it with arms and legs, and slid down the curving slack of it, until a voice shouted above him. He looked up, and saw that the helmsman had left his wheel and was poising an axe above the rope. He did not see the stroke, but the suddenly loosened rope dropped him into the sea.

Perhaps that was as well, for even as he fell he heard the whistling of searching bullets over his head.

He came up not two arm-hauls from the edge of the boat and swarmed into it.

The lofty poop of the Santa Teresa already was fading, and through the tumult he could hear the voice of Harry Dane crying: "Give them the stern chasers loaded with musket balls! Man the first boat and over with her. We're losing half our prize, you fools—"

But when the stern-chasers spoke, the Santa Teresa had vanished behind a moon-whitened wall; and the hands of The Saint already were hoisting the sail on the mast which Don Enrico and the girl had stepped for him. The blowing fog filled the shoulder of the sail, and the little boat began to lean with the wind.

"You're steering wrong!" shouted Don Enrico. "Havana lies on the port bow—"

"And Harry Dane and the rest know it," said The Saint. "Take the tiller, Alicia. Don Enrico, wipe my sword dry while I trim the sheet—and God for Merry England, I'm a happy man this night!"

The wind was not fresh, but the small boat was a good sailer and the heads of the waves began to slap beneath the bows rapidly, sending small tremors of life through the craft.

"Hard a-port! Hard a-port!" screamed Don Enrico to his sister. "No, too late! Hold her head on—and God have mercy on our souls!"

The Saint, looking aside, saw an enormous shadow running upon them out of the mist, a figure so dim that it seemed no more solid than the darkness of a squall. He saw the round-cheek bows driving the sea like plunging white horses before them, and the heavy bowsprit with the little spritsail drawing above it, and the foremast leaning with its weight of canvas above the spring of the cutwater.

Right upon them drove the monster. He saw the anchors like black, misshapen teeth ready to strike down at them. And then the danger had run by them.

But another danger followed, for the yell of a lookout rang at their ears as the little boat began to pitch and rock in the bow wave of the Santa Teresa.

And then a cannon boomed, and another, and another; and a round shot ruled a brief line of white beside them.

Then silence, and the phantom was gone, and they saw no more of her.

But still they held their places tensed and crouched, and wishing the wind ever harder and harder in the sail as they drove on the course for Havana, until the mist above them thickened to milk, and then the stain of rose spread through it, and the daylight by degrees showed them to one another, smiling, but almost afraid of what they might see in one another's eyes.