RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

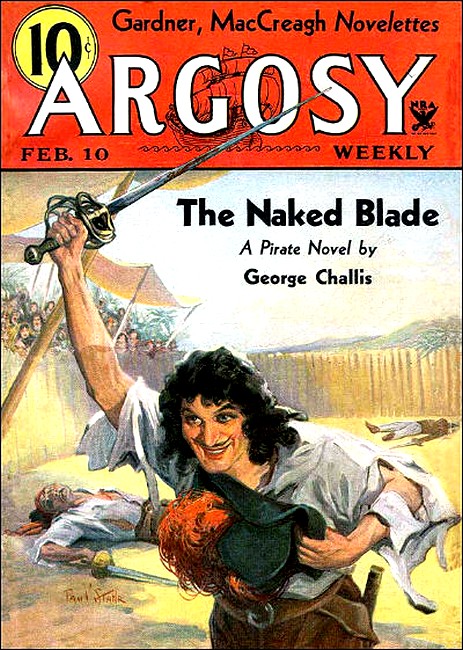

Argosy, 10 February 1934, with first part of "The Naked Blade"

"The Naked Blade," Greystone Press, New York, 1938

THE dream of Ivor Kildare swiftly accommodated itself to facts. The devil that had been breathing hot steam upon him seemed to leap suddenly upon his back and drive a spur into his ribs; so Kildare, wakening, saw the gaoler leaning over him with a long, sharp-pointed staff in his hand, and realized that he was a prisoner in the hands of the Spaniards and lodged in the prison hut of Porto Bello. The Indian woman was whimpering, as usual, and the man who groaned at every breath was the Negro who had been flogged the evening before.

"Get up," said Juan Capote, the gaoler.

Kildare pushed himself into a sitting posture with the force of his arms. His leg-irons and his wrist-irons chimed softly. The hut of wattles thatched with palm leaves was exactly long enough to hold sixty prisoners, and it was full. All lay prone, some on their backs, some on their sides, some on their faces, except Luis, the Mosquito Indian. The polished bronze torso of that giant, who sat crosslegged as usual, seemed as lofty as that of an ordinary man standing.

"Get up!" commanded Juan Capote, and jabbed with his pointed stick again.

Kildare rose with a motion so dexterous that the point of the stick missed his ribs. The length of his chains allowed him to stretch his lean arms above his head, and he stretched them now. His torn shirt let every rib be seen; the belly flattened against the backbone.

Juan Capote leaned to unlock the leg-chain from the staple to which it was fastened.

"Go out by the back door!" he commanded.

Kildare picked his way among the tawny limbs that were stretched on the earthen floor. Here and there he avoided bits of mud, also.

When he came to the back door and stepped outside, he paused a little to snort from his nostrils the stench of that prison room and to look about on the hills that surround Porto Bello like the sides of a cup. He could not see them very clearly because of the mist that went up from the dank ground and from the flat, greasy waters of the harbor; but he could discover the outlines, and the gleam of two or three of the creeks that vainly pour their waters, all year round, into the desolate sink of the bay. The forested slopes of those hills were jungles, but freedom moved in them, though like a snake.

Kildare, as he looked about him and took a breath of the fresher steam of the outside air, sidestepped, deftly, and the long goad of the gaoler shot by him.

"When I have you tied to a whipping post one day, then I shall not miss you, English dog!" said

Juan Capote. "Turn to the right. Go to the lieutenant's house."

Through the fog which covered the town with dimness and the rotting odors of the mud of the harbor, there moved many sounds of voices, for it was the season of the fair, which had run half its course. Porto Bello was a hushed and dying little village at other times of the year, but during the six weeks of the fair death battened more rapidly. Two hundred were already dead; two hundred more would die before the end of the trafficking. But commerce is more fearless than war. From the harbor came the noise of screeching ropes and Kildare saw, above the roof of the prison hut, the three masts of a great galleon which had just drifted into harbor. The fore topsail was being lowered, at this moment, into immense, pot-bellied folds. Little dark figures ran out along the yard. And beyond the mist, eastward, lay the free blue sea where every Englishman was a king!

A servant was ready to open the door of the little log house of Lieutenant Jose Urquija, who commanded in the prison, and whose face, half hardened by cruelty and half loosened by drink, was so dreaded in the long prison hut; but Kildare entered with a tread as light as that of a barefoot boy coming home. His chains jingled a musical quick-time, as he halted in front of the table which put a certain official dignity between Lieutenant Urquija and the luckless people whom he interviewed.

A man and a girl sat with Urquija at this table. As for the man, he looked like an Inquisitor, for it was not a smile that made the hollow in his cheeks, and his moustaches were drawn out in a line as straight as that of his compressed lips. His eye seemed as fierce as his body was weary. He wore a plain blue coat buttoned up to the neck, but the long and careful curls of black hair showed that he was a man of place or of money. Kildare noted him as one notes a storm cloud in a sky that is not quite overcast. The sun that looked through the dark was the girl. She kept her eyes, at first, upon the table, so that Kildare could see only half of her, as it were. But being a connoisseur, in that half he delighted. Even Kildare could not venture to stare at her, but by glances he took her image into his mind.

"Well, Señor Larreta," said the lieutenant. "This is the man you want to see."

Larreta stretched out a forefinger on which a jewel trembled and shone.

"He is the man I want to see," he exclaimed. "I know him! I know him!"

There was enough savagery in his voice to take all the attention of most men, but Kildare was able to notice that at this moment the girl looked up, and the blue of her eyes was as cold as interstellar space. He was no more than an ape on a chain, to her. It was better to look away from her to the Indian woman who stood behind, her copper face hammered all awry and the dents left by the hammer showing as purple pock marks. With both hands she wielded a large fan, moving it ceaselessly so as to cool her mistress with a gentle breeze.

"I know him now," said Larreta, "his face is not something to skip out of my memory, for when I last saw it my ship, the Madre Dolorosa, was heeling before the wind with every sail set, and a few leagues off the Infanta which I had loaded so heavily in Lisbon had already surrendered to the damned pirate. And now he came after us like a savage hound after a deer. His teeth were already in us. His ship was small but its guns were big, and every time they fired, the Madre Dolorosa quivered like wounded flesh. It seemed that half my soul had been lost in the Infanta; and the other half was about to die! They were gaining on us fast. We were twice their size, but my poor men began to run from the guns, screaming. And while I watched, in an agony, I saw in the fore-rigging of the pirate this man! They were very close; I saw his face. I saw him laugh. I saw him shouting orders. By the grace of God, at that moment one of our shots snapped her foremast in two and we ran away to safety. But as I saw him then, I see him now. He is Captain Tranquillo!"

The energy of his speech brought him half out of his chair; the lieutenant sat up so straight that his breastplate which hung on the wall at that instant could have been clapped upon him and made a perfect fit; the fan was still in the hands of the

Indian woman; but still to the girl, Kildare was no more than an ape on a chain. She turned her head a little, and against the frame of the lace ruff, Kildare saw her profile as she looked calmly at the passion of Laretta.

It was the calm of the girl, not the fury of the merchant, that made Kildare exclaim: "You lie!"

The lieutenant raised a hand and nodded; the gaoler's staff sang in the air and whacked the shoulders of Kildare.

At this the girl stood up and drew her filmy mantle about her—not for warmth, to be sure!

"The fan, Angela," she commanded. Then as the fan again began to wave, she added: "I came to see the buccaneer, Uncle Mateo, not the beating of him."

Kildare felt the blow not at all. He was too busy wondering at red hair and blue eyes in a Spaniard. Over the hair passed two bands of what seemed yellow lace, but he knew they were strips of Mexican gold-work, delicate as a spider's web. The deep blue stain of her eyes made him think of the sea when it is calm, but a thousand leagues from shore. The thin mist of the handkerchief was held by fingers perfectly relaxed.

She was unmoved, and that instant a passion went up from the heart of Kildare and formed in his throat the words of a vow for which he would spend his life.

The lieutenant was on his feet. He had caught up, in rising, his long cut-and-thrust rapier, and now he fumbled with both hands at the counter-weighted hilt of it.

"If this should be Tranquillo—" he said, "if this should be Tranquillo—"

"If this should be Tranquillo," broke in Larreta, "you will come to notice, and it will be a glorious day for Spain. Where's the printed description of the pirate? Read that! But where was he caught?"

"In the great storm which blew last week," said the lieutenant, "a ship sailed by Pedro Alvarado, was fleeing south, far from here off the coast of Campeche, and found a small boat dying in the wind, and only this man for a crew. They took him aboard, found that he was a damned Englishman, and properly brought him here to the prison of his Sacred Majesty."

"What name do you claim?" asked Larreta of the prisoner.

"Ivor Kildare."

"How did you come in the boat in the storm?"

"I was cutting logwood in Campeche when the great storm flooded us out. Three of us took the boat, and presently a great wave whirled the boat over, and righted it again. It was full of water, but my companions were gone. I bailed it out, and was sailing at large when Alvarado took me."

"He speaks clearly, Señor Laretta," said the lieutenant. Before the girl and Mateo Larreta were two wine glasses with their contents untasted, but the lieutenant's glass was already empty. He now held it out behind him, and an Indian crone arose from the floor and filled it with painful caution, to the very brim. The lieutenant drank. Some drops spilled on his chin and ran down into his beard. He caused the red liquid to disappear in the hair with a rub of his hand.

"He would not be an Englishman, if he did not lie well. Lieutenant, you have a description of Captain Tranquillo. Read it aloud!"

"I haven't the paper at hand," said the lieutenant, "but I know it by heart. So does every Spaniard of the Mexican and the Caribbean Seas. A man of six feet or less, lean and hard, a swarthy skin, black hair, and very blue eyes."

"Look before you, then! This is the very man!" said Laretta.

"A thin, black line of a moustache," went on the lieutenant, "a mouth somewhat sneering——"

"Exactly! See with your own eyes, if they are open!" exclaimed Larreta.

"—and," continued the lieutenant, "a calm demeanor and assured. Also, there is a large white scar cut between the eyes."

"A calm demeanor—and what could be calmer than the behavior of this devil?" asked Larreta.

"There is also the matter of the scar," said the lieutenant.

"Scar?" cried Larreta. "There is a matter of doubting fools and halfwits, also. As though a scar cannot be put on with a strip of plaster and taken off again!"

The lieutenant grew crimson. His face fairly swelled with the insults which had been so open. But suddenly he seemed to recall the importance of Larreta, and mastered his anger.

"I must have greater proof," said the lieutenant. "If I could be sure, he would burn tomorrow in the plaza."

"What is your proof, English bloodlapper," demanded Larreta. "What is your proof that your story is true?"

"It lies in a gesture of sweetness," said Kildare. A smile appeared faintly on his harsh face. He removed his battered hat with a wide and graceful sweep, and a delicate fragrance passed into the air of the room.

"He means the perfume," observed the lieutenant. "It is known that the logwood cutters of Campeche are apt to wear little bags of dried musk in their hats."

"His proof that his name is Ivor Kildare is a bit of fragrance in the air," answered the merchant. "My proof that he is really Captain Tranquillo shall be a bit of blood. Send him away, señor, and I shall open my mind to you. It will be worth hearing."

"Señor Larreta," said the prisoner, "it is true that I am not Captain Tranquillo. There are some little differences between us besides the matter of the scar. One is that he is Italian, while I am English. But even if you put his name on me and burn me for it, still I have good reason to be glad that I was brought to Porto Bello!"

His hat was still in his manacled hands; he pressed it now against his breast and bowed over it toward the girl.

The lieutenant sprang to his feet.

"Beat the dog from the room!" he shouted.

Juan Capote brought his staff down whistling on the back of the prisoner, again and again, but through the shower of blows Kildare straightened himself without haste.

He looked to see some break in the calm of the girl, but still she eyed him no deeper than the rags which clung about his nakedness. The staff still labored him as he turned toward the door, but he felt nothing except his rage.

THAT afternoon, when the time of siesta had ended, when the sun was red gold through the western mist, and the promise of night began to draw people into the open from their houses, Juan Capote came again to Kildare. His slender length was stretched on the ground as before, but this time his eyes were open, though there was a dream in them.

"Stand up!" said Capote, and grinned all on one side of his fat brown face.

The starved body of Kildare arose with an effortless ease, though his hands had not touched the ground.

"Here's the last day, Captain Tranquillo," said Juan Capote.

"Are they about to kill me?" asked Kildare. "They are."

"Then God receive my soul!" said Kildare, quietly. "And so much for that. It's the stake, I suppose?"

"If you miss the stake today, by proving that you're Captain Tranquillo, they'll burn you tomorrow because of the proof that you've given today. If there were twenty pounds more of you and a scar, you might be Tranquillo, for all that!"

"Have you seen Tranquillo?"

"I have."

"Will you tell them, Juan Capote?" asked Kildare.

"They'd ask me where I saw him, and that would be a long story. Besides, why shouldn't the gentry burn an English devil, now and then, to warm their hands?"

"Ay, and why not?" asked Kildare. "But tell me how they can make me prove that I am Tranquillo?"

Capote signalled to two half-breed assistants who now unfastened the leg-irons of the prisoner and stripped them away.

"They'll do it by baiting you like a bull. They've got three condemned men waiting for you in the cattle pen, and you'll fight all three at one time."

"All three?" murmured Kildare.

"Ay, with the weapons they wore when they were captured. There's Martino and his cutlass. He's a Negro slave that escaped and worked with a gang of man-killers in the back country till he was caught a while ago. And there's Luis, that big Mosquito Indian that I've had in here. He has his spear and his knife. Last, there's Jan Van Osten, a Dutch buccaneer that would be enough for you. Yes, with his rapier and dagger, he'd serve out two like you."

"The whole thing is nonsense," said Kildare.

"But anything that means murder is a good thing, to you Spaniards!"

"I'd beat the teeth down your throat," said Juan Capote, cheerfully. "Except that I want you fresh and sweet and fair for the fighting—you and your little splinter of a sword against the lot of 'em. What would you pay now for a real blade worthy of a man's hand?"

He leered at Kildare, who merely answered: "Suppose I kill the three of 'em—with my splinter of a sword? Suppose I come off the winner, what happens to me then?"

"There's the point of the thing. There's the beauty of the idea. It came out of the head of that rich merchant, that Larreta. No wonder he has twenty ships trading on the seas, as far as China! He made the lieutenant burn with the suggestion, and the lieutenant convinced the governor. So you fight today as Ivor Kildare, an English cutter of logwood from Campeche. If you are killed, there is one less English hound in the world, and the man who finishes you will be given his freedom. But if you should win and finish the whole trio, then mark the sweetness of your reward. Having conquered today, you will have proved that you are in fact what Larreta says: the terrible pirate and tiger of the seas, Captain Tranquillo. Therefore, for your victory today, you will be burned tomorrow with proper torments beforehand. You see that the thing is perfect. Either way you die. By the steel as Kildare, by the fire as Tranquillo. Do you admire the great mind of Larreta? Tell me freely what is in your mind? Could anyone else have thought of so perfect a scheme?"

With a grin, with a gaping hunger, he looked into the face of Kildare to find terror, and finding none, he pursed his lips as though he were about to spit, and ushered his prisoner out of the dark hut into the open.

His shackled hands were fastened to the arm of one of the prison guards, and in this fashion they went through the sandy, rutted streets to the big corral in which cattle were kept before being butchered to supply the town and the larders of outgoing fleets. The beef had been shunted out of it, on this occasion, and the whole population of Porto Bello had gathered as to a fiesta, packing in rank on rank around the high fence. Kildare, taken suddenly through a gate which was closed after him, found the interior of the fence lined with soldiers, and while he could see little of the ordinary people who were packed close against the palisade, all the notables of Porto Bello were in view. Planks raised on hurdles accommodated them with a low platform than ran all across one end of the corral. Beyond them, he saw the flat, leaden waters of the harbor, and the forts which guarded the mouth of the bay. The town was one of the strongest places in the possession of the king of Spain.

A squad of soldiers now came straight towards him. He paid no attention to them, but muttered to his gaoler: "Juan Capote, I see her again—the same lady who called Larreta her uncle, today. Who is she?"

"Why, telling that costs nothing, and I'm one to be kind to dying men," said Juan Capote. "That is the noble lady Ines Heredia, with plenty of blue Castilian blood, and not a penny to her name. She's the ward, but no relation, of that Larreta who made this show for you—and the rest of Porto Bello."

He laughed a little, as he came to the end of this speech. The squad of soldiers came up at the same time, and surrounded Kildare. Their officer was a square chunk of a man with the face and the eye of a fighter. He put his hands on his hips while he looked Kildare over.

"If you are Tranquillo, a sparrow is an eagle," said he. "But I do the work assigned to me. You know why you are here?"

"I do," said Kildare.

"Good," nodded the officer. "There are the three."

They stood at the farther end of the enclosure, the huge bronze body of Luis dominating the group. He was naked except for a loin cloth; but he was clad in dignity, besides, and he held in his hand a spear with an eight foot haft which nevertheless did not rise so very much above his head. The Negro wore only a pair of soiled white trousers with a sash about the hips, and carried a huge cutlass which he was brandishing eagerly now. The sun gleamed on his sweating shoulders and made the blade of the sword a swinging flame. He was not a giant like Luis, but he was a powerful fellow, and so was the Dutch pirate who stood a little apart from his companions, twirling his long moustaches to points and leaning on a great rapier.

"Three workmen, eh?" said the Spanish officer. "If you beat them, you are in fact Tranquillo, and we will burn you on another day."

"Thank you," said Kildare. "I have heard of Spanish courtesy, and now I am to taste it. If I win, I am Tranquillo. If I lose, I am myself. I understand."

"Very well, then. The light will grow bad in a short while. It is time to begin. But tell me—is this really your weapon, or only a child's toy?"

He took from one of the soldiers a scabbard strangely short and light. Kildare held out his wrists to let the irons be unlocked.

"That is mine," he admitted.

The key turned in the hand-irons; they fell with an abrupt crash into the dust. Then Kildare took the hilt of the sword and whipped out the blade. It was a mere needle, compared with most of the heavy rapiers that were used in that day; it was a mere line of light.

"If you fight with that," said the officer, "you are a madman this minute and will be a dead man the next. Do you hear me, Tranquillo, or whatever devil you are? If you were an angel from heaven, those three would cut you to bits and eat what they carved, no matter how you were armed. But the odds against you are big and if I intercede with the governor, who has a noble heart, he will let you have a better sword, with some weight and reach to it."

Kildare flexed his body, straightened, and then made the slender thread of bright steel tremble in his grasp.

"My friend," he said, "you are so kind, for a Spaniard, that if you were in my hands I would give you any gift, even a painless death! Let me tell you a little story of an evening when I was cornered in a dark lane by some fellows who wanted the blood in my heart, and as I swung my long rapier it struck a stone wall and splintered lengthwise, so that I kept only the hilt and a long splinter of steel. Yet a very little later I left that alley, and was in no haste. The others were not running to find me! They had other things to think about. After that, I gave up heavy blades. This one is light, as you see, but so is thought, so is death."

"It is on your own head," said the Spaniard. "We have wasted too much time. Go to the center. The three will find you there soon enough!"

He stood aside. The soldiers moved sternly forward, but Kildare walked uncompelled, his head high, and what seemed a flicker of the sunlight in his hand. His three enemies came straight at him.

A roar of excitement from the crowd made the air tremble, but that shouting died away when it was seen that the Dutch pirate was waving his arms and shouting for silence.

Then he could be heard crying, in very bad Spanish: "Excellency the Governor, give me a cheap gift. It is proper that a white man should die by a white man's hand, and not that filthy Negroes and Indians should have a share in the thing. Furthermore, I, Jan Van Osten, swear in the name of the devil and all brave hearts to lay this fool dead at the feet of His Excellency!"

Another, shout rushed up through the misty air of Porto Bello. That in turn was cut short at the lips of the many when they saw Kildare take off his battered hat and wave it to the four quarters of the compass.

When he had secured silence, he turned his back upon the advancing trio as if they had been shadows, not armed men, and lifting his hat in one hand, his glimmering sword in the other, he faced the raised platform of the notables of Porto Bello. He was near enough to see their faces, though not clearly, and it seemed to Kildare that the lady Ines Heredia leaned forward a little as though to hear him the better.

He called: "In the name of God and all free men, I, Ivor Kildare, offer a gift and a cheap gift, which is the blood that I lay at the feet of the lovely lady, Ines Heredia."

Even men about to die should shun insolence. The crowd looked towards the gentry and became silent. And from the notables there was heard a brief murmuring. Then total quiet followed.

Kildare tucked his hat under his left arm, made with the sword a salute that was accurately aimed at Ines Heredia. Then he saw that she was not even regarding him, but looking towards the harbor's mouth where the sail of a fishing boat shone like a metal shield.

That was why he turned suddenly, pinched by fury, and not because the three were advancing so close to him with their weapons, one of them free from death if he could take the life of Kildare.

Martino the Negro went a little ahead of the others. He was singing a love song as he flourished his cutlass. The Dutchman was close by him, and the long-striding Indian followed a step or two in the rear.

A wordless cry came out of the throat of Kildare, and he rushed straight at them.

THE Negro, at that sudden attack, bounded like a great black cat to the side. Jan Van Osten made a gesture with both elbows, as though to assure himself of room.

"Keep away, Luis. Give me space, Martino!" shouted the Dutchman. "One stroke and I finish the battle for all of us!"

He had on heavy boots, the tops of which flared out as widely and clumsily as the fluttering ribbons of his trousers, but he ran lightly enough to meet Kildare. Luis, the Mosquito Indian, held back, but Martino had no desire to see Van Osten win the freedom that was the prize for one of them. He came rushing in on the left of Kildare with a broad sidesweep of his cutlass at the very moment that Van Osten lunged. No man on earth could have parried those simultaneous strokes. Kildare made no effort to do so, but at the exact last instant he slid underneath that double flash of steel and leaped out again. His sword blade was no longer silver but almost to its hilt ran glimmering red.

The Negro hurled his cutlass away in the same gesture with which he clasped his body round and round. He sank to his knees, then to the ground, still clasping the life that was running from him, and kicking out with his legs.

Jan Van Osten had seen the length of his good cut-and-thrust rapier run out into the air over the Englishman's shoulder. He had seen the Negro fall, also, and he now recovered himself and felt as though the mere wind of his thrust had sent Kildare lightly back before him. He was not prepared to see Kildare wheel and make a double gesture of hat and sword, crying: "One life for my lady!"

But Ines Heredia looked on as at a picture, with her slender fingers interlaced and dropping. A madness of voices was in the air. Behind Kildare came danger that he felt like a shadow over his mind, but still as he waited with lifted hat and sword, the girl gave no token.

He had to whirl. The sword of Van Osten was at his very eyes, blindingly bright, but as a dead leaf shifts before the hand that tries to strike it, so the breast of Kildare slid from under the point of the Dutchman's rapier.

It was plain that there was to be no nonsense about fair play and that Van Osten was as willing to take a life from behind as from in front. He recovered himself from the lunge that might have spitted Kildare. Between the shoulder blades and stamped in a rage. Two dust clouds puffed out beneath his foot.

"You son of a black cat and a dancing master!" shouted Van Osten, and drove in with feint and thrust and lunge. The slender blade of Kildare touched those furious efforts lightly away. Such fencing as this he knew. It was the formal art of Spain. There was also the graceful school of Italy and above all the quieter, more precise, more deadly fashion of the French. Kildare had learned a great deal from all three systems, but when he threw away nine-tenths of the weight of a rapier and much of its accepted length, he had to bring to the use of his more delicate weapon a more delicate craft. He showed it now. A ghostly hand seemed to flash before him and put aside the lunges of Van Osten. And he had time also to wonder at the Indian who, a little distance off, had grounded the butt of his spear and leaned on the haft of it like a disinterested spectator of boy's play.

Van Osten had tried the point. Now he tried the edge with all his might. There was a red scarf tied around his head and the end that dangled behind his neck jerked and snapped with the violence of his blows. Yet he gained nothing. His heaviest strokes slithered away like falling water along the dainty rapier of Kildare. And the face of Van Osten, yellow as that of a Mongol, was patched with whiteness about the mouth.

"Am I Captain Tranquillo?" demanded Kildare. "Am I Tranquillo?"

"I've sailed with Tranquillo and seen the new moon on his forehead," said the Dutchman. "I'll sail with him again, and tell him how I slaughtered you like beef in the cattle pen of Porto Bello. Stand and fight, if there's any man in you."

"I'll stand and fight," said Kildare. "Come on, Van Osten!"

Van Osten came, feinting at the head in a fierce thrust and then lunging full for the heart. Once more Kildare disdained a parry and matched the speed of his body against the speed of a striking hand. His shoulder slid under the point of the leaping rapier. In the face of Van Osten he flashed his own sword like a ray of light, half silver, half dripping red. Then he stepped back and stood at ease with the point of his blade resting against the thumbnail of his left hand. And Van Osten, dropping his long rapier and dagger, stood agape as though he were beholding a miracle. He dropped to his knees with one hand at his throat. He seemed striving to speak, but only a red froth bubbled on his lips. Then he dropped forward, struggling in the dust with an invisible antagonist for a moment. He was still convulsed in that agony when Kildare turned with hat in one hand and the red sword in the other, crying: "A second life for the pleasure of my lady!"

He could see the grinning, beastly joy of the soldiers. Even the governor, dignified by his grey beard and his splendid cloak, had stood up to watch. Larreta had the face of one who curses bad fortune. Only the girl was unmoved. He could guess at her expression rather than see it, but it seemed to him that Ines Heredia was looking toward the harbor mist and smiling at her own distant thoughts. In her face he could read nothing of the moment.

Kildare ground his teeth and turned toward his last antagonist. Luis the Indian, moved by some sense of chivalry that no white man could have taught him, had held his hand during the first part of the battle. There is a golden lightning that may strike through the brain and through the heart as it struck now through Kildare when he realized that he had found such nobility in a savage. But now the giant came on like one who feels that he is the master, and Kildare knew his danger. In all the world such javelin men as the Mosquito Indians never have been seen, and in battle they were never known to go backward. The lucky captain of buccaneers who could bring one of them into his crew, knew that the man would keep the whole company in food by striking whatever fish came looming beneath them through the green waters of the coast, and in fight the Indian would not falter until the all-wise white men commanded a retreat. This fellow came on eagerly, now, with his terrible spear uplifted. Bronze in his color, like red bronze he seemed invulnerable to wounds. A wind from the hills lifted the long hair from his shoulders. He was to the slenderness of Kildare like one of those gods or kings of Egypt who on the temple walls are shown slaying whole ranks of Asiatics.

Well in spear-cast, Luis paused, exclaiming:

"White man, what is your nation?" The sound of good English was strange to the ears of Kildare.

"I am English, Luis," said he.

"I have sailed with your nation," said Luis, "and we have been brothers together. But there is only one life between us, now. Englishman, I have a wife. I have one son to live for and one son to revenge. Be strong and be swift. A spear is longer than a sword! Are you ready?"

"Ready, Luis," said Kildare, "I'd rather be killed by you than by the other two. But you'll find in this sword a sting that can put the poison in your heart and the darkness in your eyes as well as spears and snakebite. Come in!"

They ran straight in on each other. The Mosquito, with a hand that could be swifter than the gleam of a darting fish, struck rapidly for the face and the body of Kildare; and as the shadowy fencer avoided the danger and leaped in, Luis sprang far away and brought the fight to spear's length, again.

Something pulsed and stabbed in the brain of Kildare. It was the screeching of the people that seemed to be ringing inside his own mind, like a thought. He knew that death had just brushed him with its hand, and an electric tremor was working through his nerves. All his muscles twitching, like a cat that has missed its kill, he went wavering back before the spear, while the giant stepped on, offering either a thrust or the hurling of the spear. If the javelin were spent, there remained the long knife at his belt. And always the bright flash of spearhead avoided the touch of the sword which might neutralize its striking power.

The blue eyes of Kildare began to burn. He circled. The dusky gold of the Indian's body, now burnished with sweat, wavered against the background offered by the gentry of Porto Bello. They were so close now that Kildare could see their faces, and the glint of money in their hands as they laid wagers. The governor leaned eagerly forward from his chair; Larreta, with arms half folded, nursed his lean face with one hand; but the girl had turned indifferently, to speak with her attendant!

"Now!" cried Kildare, and seemed to be rushing straight in on the spear. But as a seagull may be hit by a sudden gust and struck off balance, so Kildare seemed to miss his footing in the deep dust, almost as treacherous as water, and staggered helplessly.

It was a trick, but a dangerous one. By the eyes and by the glinting white teeth of Luis, he saw that the Indian had taken the bait; then right at his throat came the point of steel. He managed to dodge it, barely. The flat of the lance-head kissed his shoulder; the wooden haft of it burned his skin. He caught that shaft with his left hand, and Luis, wrenching the weapon back, pulled the sword of Kildare right in at his breast.

But even as Kildare flashed in, he gave up the death that his sword was hungry for. He reversed the blade, and the pommel struck Luis between the eyes, and leaped out to safety again, with the trembling rapier singing a small song.

But the Indian did not try to strike in turn. His face was that of one who sleeps, with open eyes. His hand, gradually relaxing, let the spear fall to the dust. Yet he did not crumble, but rather fell as a tree falls, his arms swinging out above his head as he pitched forward on his face.

And the crowd roared like a wind!

Kildare looked round on them with a savage contempt. Then he dropped to one knee, gripped the long hair of Luis, and raised the rapier like a dagger to strike into the senseless back. He looked to the ladies and the gentlemen of Porto Bello. They were a mass of gesticulation. Those who had lost wagers were cursing their luck one instant, and the next shouting to the victor to kill; the winners, with laughter, held out their hands to take the gold. Yet all their hungry eyes were waiting for the final stroke. Only the girl sat apart from the rest.

She was not human. She was stone. This glorious red-bronze giant under the knife was no more to her than a phantasy through which she looked carelessly.

Kildare, in a red rage, reached out his will and set it upon her like hands.

He shouted: "To color her cheeks and redden her lips, a third life for my lady!"

They hushed their yelling, all of them; they risked a side glance toward her though by so doing they might miss the death. Kildare jerked his hand higher as though to deliver the blow, and that gesture seemed to draw her from her chair. She flung up her hands. They were stretched and rigid with protest, and Kildare saw the handkerchief, like a bit of translucent mist, fall from one of them. He could feel all those who waited in silence. Her voice came. He smiled. It was like the cry of any common woman who screams out in dread and in horror.

"Señor Kildare! Señor Kildare! In the name of God, be merciful!"

He stood up from the prostrate body. In his exultation, with his head thrown back, his sword seemed to salute some God of battle in the sky. Then he bowed to the lady until the point of the blade dipped into the dust.

Ines Heredia had covered her face. Larreta supported her. And Kildare would have paid rivers of gold to know whether or not she was weeping. He began to laugh through his teeth, softly. He was still laughing when the hard-faced officer and the soldiers came upon him. The manacles were clamped hastily upon his wrists. There was a tenseness upon these men, an anxiety until they made sure that his hands were helpless and his sword gone.

Beside him and behind him the soldiers formed. The officer walked ahead carrying the sword of Kildare in its scabbard and his own naked weapon, as though he expected that he might have to clear a way through the crowd. So it seemed, too, when they came through the side gate of the corral. For the people came in waves, crying: "Captain Tranquillo! Captain Tranquillo!" Some appeared merely curious to see his face at close hand. Others shook fists or weapons at him. A tall, gaunt half-breed woman followed all the way to the prison hut, screeching: "Burn him! Burn him! He killed the men and the women at Nombre de Bios! He tortured them. He murdered the babies."

Others began to roar: "To the stake! To the stake!" but all of these were rabble and they dared not brush shoulders with the armed men of the guard.

So Kildare stood at last inside the long hut with the familiar stench in his nostrils and the familiar groanings in his ears. And Juan Capote said: "You fought for a famous name today, señor. Tomorrow you will burn for it!"

Juan Capote began to laugh loudly, but through the laughter Kildare heard the voice of a girl sobbing. She was new to misery, for there was still music in her throat; and as he listened to her, Kildare saw in his mind another face.

THE leg-irons had not been fixed on Kildare before a messenger came panting, with word that the governor wished to see Captain Tranquillo at once, so Juan Capote led him out again. The sunset and the quick twilight already had passed. It was night, and the stars shone faintly down through the vapors of Porto Bello.

"Perhaps they will not wait," said Juan Capote. "They may be of my mind, and I always prefer a burning in the dark. One can see the flames more clearly at their work. And there's more meaning to screams that one hears at night, eh?"

"I could enjoy it," said Kildare, "if all of Porto Bello were shrieking in one voice, while we stabbed the fat merchants and hanged up the women by their hair till they confessed where the household treasures were hidden. I could relish the chorus, but I would listen carefully through it to find the voice of Juan Capote, squealing."

Juan Capote began to laugh at this delightful and absurd picture. And now they came past the old hospital where the sick from the ships were tended. Through an open window they heard a delirious patient expostulating, screeching, singing, laughing. Then they went by the cold and silent face of a church, and the top of it was almost lost in the foul mist of Porto Bello. They came to the houses of merchants built of cedar wood or stone, and at last reached the mansion of the governor. Soldiers took charge of Kildare at the entrance. They led him straight into the great hall of the house, where a dozen men sat with the governor around the ends and one side of a table.

There was plenty of light for this group, but the room was so large that Kildare was only dimly conscious of the big hand-wrought beams that crossed the ceiling, and of a balcony that was corbelled out from the end wall. A brocade of crimson and gold hung over the balcony railing and behind the drape he made out the faces of women. With the other grandees at the table sat Larreta; was not his ward, therefore, among the chosen few who were permitted to make an audience in that balcony? Kildare began to smile.

His smile even continued when his escort jerked him to a halt facing the governor; and those stern councillors regarded the prisoner with stony faces. For a moment there was no stir among the images that floated in the polished surface of the table as if in tarnished water. The governor spoke first, in a voice as imposing as his appearance.

"Captain Tranquillo," he said, "you have earned your name, today, and you have earned the stake for tomorrow. However, it is possible that fortune may still find a way to favor you. You may be given slavery instead of death if your answers to our questions are frank, open, and direct. I begin by asking if you were ever in San Lorenzo?"

"Your excellency," said Kildare, "has it been proved today that I am Captain Tranquillo?"

"It is proved to our satisfaction," said the governor.

"Then the world knows," said Kildare, "that Tranquillo stormed and sacked and burned San Lorenzo."

Every man at the table stirred suddenly in his chair. One of the officers stood up.

"Sit down, señor!" commanded the governor.

"Under your leave, your excellency!" muttered the soldier. "I cannot stay quietly in my chair when I see the face of this pirate and murdering dog, Tranquillo. By the saints, he smiles at us!"

"Sit down, nevertheless," said the governor. "Perhaps there is a time to come when he will smile no longer." He went on, as the man of war dropped sullenly back into his place: "Tell us, briefly, Captain Tranquillo, what happened in San Lorenzo."

"Certainly," said Kildare. "The buccaneers had landed ten miles below the town and hacked their way through the forest till they came out behind San Lorenzo. They saw the three forts on the hills. It was agreed to attack the middle fort first. The signal was the rising of the moon. So when that moon rose, red with Spanish murders and dim with Spanish lies—"

"Do you hear?" cried Larreta.

"Be still, Señor Larreta," commanded his excellency. "You may speak later in your turn, if you please."

Larreta groaned. With both hands he strangled a ghost of thin air, and sinking his head low on his chest, he looked up fiercely toward the narrator. Kildare glanced toward the balcony.

"When that moon rose," he went on, speaking toward the balcony instead of toward the governor, "the buccaneers rushed the middle fort. An Indian saw them. Only an Indian, for every Spanish eye was fat with sleep. Three times the buccaneers were clubbed and shot from the walls and three times Captain Tranquillo rallied them. The fourth time he gained the top of the wall, cleared a space with his sword, and instantly his buccaneers were swarming up beside him. The Indians and a few Negroes fought to the last, but the Spaniards fell on their faces and screamed for mercy. They were knocked on the head as they lay!"

The smiling of Kildare turned into laughter. He looked into every eye of those who sat at the table and tasted the hate and the fear in their eyes.

One merchant with apple-red cheeks and a skin almost too brown to be European, cried out that the last statement was a lie, and that he knew of a gallant gentleman—here the governor stopped the interruption and Kildare went on: "So the guns of the middle fort were turned on the outer forts, while Tranquillo went to one fort and then to another, and drove the garrisons screeching down the hill to the town."

"Speak in the first person if you are telling your own story," directed the governor, annoyed.

"You know that I am Tranquillo," said Kildare, "but God forbid that I should speak of what his hand accomplished that night as though I had done it. For he was a glorious hero, and even men could hardly have stood against him, to say nothing of Spaniards!"

He heard a shrill, musical murmuring, and turned his smile toward the balcony of the hall.

"Now when the defenders of the forts were driven into the town, the buccaneers came down on San Lorenzo like a flood. On the front of the wave they carried like froth all who tried to resist. Here and there a house stood out, but they were soon kicked to pieces. The screeching of the men soon ended, and the yelling of the women began."

His eyelids closed. As he laughed, the pupils were mere glinting bits of lapis lazuli. Some of those men before him were grey-green. Some were red. All were shining with sweat as they listened, except the governor, who said calmly: "You knocked the men on the head?"

"The Spaniards were knocked on the head, as soon as the Indians and the Negro slaves had stopped fighting," said Kildare.

"And the women?" asked the governor.

"Some were put to one use and some to another," said Kildare, "but the ugly wenches were made to talk."

"And how was that managed?" asked the governor.

"Why," said Kildare, "we are speaking of Captain Tranquillo, and you know his methods. Why else should you all be sweating? Why else should the ladies, yonder, be squeaking like mice underfoot?"

Someone groaned out a mighty oath that had the name of St. James in it, but Kildare went on lightly: "Much treasure had been flung into wells and cisterns, much had been tucked into odd corners, and why should noble buccaneers waste their manly time in such searching? The limbs of the prisoners were stretched with cords while their bodies were beaten gently to death. Some were tied up by the neck with weights attached to their feet. Some were tied up by the hair and toasted with burning palm leaves. Some were tied to four stakes by their thumbs and great toes, which was a very pleasant invention, and on some weights were laid which slowly stopped their breathing."

"And they talked, Captain Tranquillo?" said the governor, while a shrill murmuring broke out from the women.

"They spoke volumes of words," said Kildare, "which produced volumes of treasure, silver, in coins and in bars, gold, jewels, rich cloth, spices, silks from China, all heaped in a room of the governor's palace—a room very like this one, your excellency!"

"And then?" said the governor, stroking his beard.

"Then a storm smashed the fleet in that cursed harbor. A great army was coming overland from Panama, and the brave buccaneers were forced to carry their loot away. Many entered the forest. Few came out of it."

"And the treasure?"

"All except a few keepsakes were buried among the hills, of course."

"Therefore," said the governor, "if you lead us to the places where that treasure was buried, because we know that it was very great, we will spare your wretched life, Captain Tranquillo, and give you over to imprisonment."

Kildare sneered into the waiting, eager faces.

"I'd rather feed human flesh to dogs than such riches to the Spaniards," said he.

"Your excellency," said Larreta, "nothing will shake him, except fire, and fire burns as well by night as by day, and in a house as well as in the damp open air!"

"No," said the governor. "You have heard some of his torments described. Perhaps we can think of still others. All that cruelty can do to him shall be done. Soldiers, take him away, and give him again to his keepers! Tomorrow is time enough. And the people must not be cheated!"

"My lady Ines, adieu!" called the clear voice of Kildare.

Then the guards dragged him swiftly from the hall, and Capote brought him again to the jail, where the same greasy leg-irons fastened him once more to the wall. A rag burned in a bowl of fat. The smell of the soot was stronger than the waves of light that came from it.

"Here comes the food," said Juan Capote. "Eat well and sleep well, poor devil. Tomorrow you'll need your strength. Besides, the crowd wants a lot of you, and not a quick death. You'll see that we Spaniards have brains!"

He went out as the meal of the day was served. It was ladled from a bucket; a double handful of maize, stewed with rancid grease. But Kildare ate every morsel of his share, and licked his hands clean. Then came the water, borne in the same unwashed pail. Kildare, like the rest, bowed his head and sucked up as many mouthfuls as he could before the bucket was swung from him to the next prisoner on that side of the shed. Then he lay back, almost prepared to sleep but with his shoulders pillowed for a moment against the wall of the hut. So he passed into deep thought which the snarling of the others could not disturb. They fell asleep one by one, some groaning, some snoring, but the blue eyes of Kildare were still awake when Juan Capote kneeled softly beside him and whispered: "There is more luck in you than there is hair on the devil; you are a free man!"

DELICATELY Juan Capote worked the key in the locks and laid the leg-irons and the wrist-irons soundlessly on the ground.

"Now up," he murmured, "and follow me. Be a shadow. Make no sound. No one must know!"

Kildare arose, and down the double line of dusky, sleeping bodies, he marked the glistening bronze of the Mosquito Indian. So he took Juan Capote by the arm and whispered at his ear: "Set Luis free, also, Juan Capote. Whatever price you've been paid for me, you can afford to throw him in, also."

"What do you want him for?" demanded Capote, staring. "To cut his throat at your own pleasure after he's free? Come on with me! Hush! If a sound is heard the guard will know—"

"Set Luis free," said Kildare, "or I'll shout. Then if I burn for a buccaneer, you'll hang for a traitor!"

Capote wavered for an instant between fear and disbelief. Then he made at Kildare a gesture and a face of rage, but glided off to the Indian. Kildare, at the door of the hut, waited until the two forms came towards him. They passed with him into the open, where Luis lifted his free hands to the sky. There they waited until Capote brought them each a cloak, to Kildare a feathered hat, as well. The sword belt and the sword of Kildare followed, and the spear and the knife of the Mosquito Indian.

"Now, as God loves you, go quickly!" said Juan Capote. "The watch will turn that corner at any moment. Besides, in a few minutes I must enter the prison and find you gone, and raise the alarm. The bloodhounds will be after you, then! Use your legs; put a distance between you; and bless Juan Capote all the days of your life!"

"I have to know two things before I go," said Kildare. "The first is: who bribed you to do this, and how much was the bribe?"

"I have sworn to tell nothing. No one bribed me. I pitied you, Kildare, and you have forced me to let the Indian go, also."

"As for your oath," said Kildare, "it is only the breath of the fat pig, Juan Capote, soon given and soon drawn again. I'll have the name, man! Out with it!"

"This is your gratitude, you English dog!" snarled Juan Capote, and he whimpered with the might of his suppressed passion. "Her name is Ines Heredia. Who else would pity your life, except a blessed angel? She gave me a hundred pieces of eight; which is small enough pay considering the danger I am in. The governor will strangle. Larreta will die in a fit, when they know you are gone!"

"One thing more," said Kildare. "When the day comes for me to return to Porto Bello and purify it with fire, Capote, I would like to know the house of that Larreta. I owe him more than even fire could repay."

"I've told you enough," said Capote. "Hurry. I hear the watch coming now. Sacred Virgin guard and protect Juan Capote—"

"Tell me the way!" insisted Kildare. "Or we'll deal with the watch together, the three of us!"

"Damnation eat you in small morsels!" groaned Capote. "The house is beyond the church which we passed today. It is next to the church. Quickly! Quickly! Or we are all lost!"

"The good angel of bullies, cut-throats, and cowards watch over you, Juan Capote. Farewell," said Kildare, and instantly glided around the corner of the building, with the enormous bulk of Luis beside him. Kildare broke away at full speed; the Indian followed. The effort was so small to him that he could speak without panting, smoothly: "It is the wrong way. The harbor is the opposite way, and we must take to the water or the dogs will find us."

Kildare said nothing. He needed his wind for running and held straight on until he came to the strong palisade of the cattle market. Over that fence he vaulted and paused with his feet in the deep dust, breathing hard. The Indian stood beside him. One gesture had wrapped him in his mantle and turned him into a draped statue.

"The bloodhounds will have wise noses if they can follow our tracks across this trampled ground," said Kildare. "And now, Luis, you are right. The safest way is toward the water. That is the road for you. For my part, I have something else to do."

"I stay with you," said Luis.

"You can find some small canoa and slip out the harbor's mouth," said Kildare. "Or you can work your way up the coast through the forest until you come to your own country."

"I stay with you," said Luis.

"You have a wife waiting for you; you have a son who is waiting!" exclaimed Kildare.

"They may wait in peace," answered the Indian. "I should have died today with your sword in my heart. Instead, there is only a mark between my eyes to tell me that I have found my father. He took me from the Spaniards. He gave me my free hands again."

"Give me your hand," said Kildare.

The terrible grasp of Luis instantly crushed his fingers.

"My blood is your blood," said the Indian.

"My blood is your blood," said Kildare. "Follow me!" And he fled across the great corral where they had fought that day. He knew where the Negro had fallen and where Van Osten had lain. On the naked scantlings which had made the gallery, he could conceive again the crowd that had looked on, laughing, wagering gold. And she also had sat there, she to whom his life was worth a hundred pieces of eight!

One could buy a very good slave, for that price —a woman able to embroider, to dress a mistress, to use a fan, and to hold her tongue.

They scaled the palisade on the farther side of the field. Kildare no longer ran, for other forms moved in the street. He went on at a rapid walk, and the Indian followed him one pace behind, with the lance in his hand like a staff.

They passed the hospital and saw a light glide across a window on some errand of mercy. The church loomed on their right, then the broad front of a house built all of stone. They rounded it. An unbroken wall faced them on every side, and as they reached the back of it, Kildare paused.

"Can it be climbed, Luis?" he asked.

The Indian dropped his cloak and his spear and swarmed up to the top. He made only a soft scratching sound as he found purchases for fingers and toes. Into his reaching hands, Kildare tossed the cloaks and the spear and his unbuckled sword. Then he grasped the butt of the spear that was lowered to him, and so came easily to the top.

It was a narrow terraced roof that enclosed a patio on three sides; on the fourth the main body of the house rose an extra story. Of the windows, only two were lighted, and Kildare considered them while he fastened into the crown of his hat the small sack of musk which he had taken with him. Then, donning his cloak, he wrapped his sword in a fold of it and went to examine the lighted casement to his left. His head was well above the ledge of it, and he found himself looking straight into the eyes of Larreta!

That was all he saw, at first—the mouth pressed into a line, the inquisitorial eyes squinting as though they had just found Kildare at hand. But the gaze was fixed and did not shift with Kildare, so that he knew Larreta was beholding only some conception of the mind. He was at a writing desk well piled with papers. A bed, built like an ugly house, filled half the little room. All was dark and comfortless except a niche for a saint that was set with bright-colored tiles brought from Spain. The thought of Larreta seemed too grim to be put down easily in words; his pen remained suspended during the long moment while Kildare watched.

That eavesdropper moved to the next casement and found what he searched for. The lady Ines Heredia lay in a great chair among cushions. She was wrapped in thin Chinese silk, blue, and worked with a thread of gold. Her hand was as white as the throat on which it pressed. Her eyes were closed. Above her the dark hands of Angela moved the fan, and Kildare remembered that the night was warm.

Her eyes would not open, but her lips moved.

"What would you do, Angela?"

"Fate is the name for God and a stern father. It must be met," said Angela.

"He is not my father," said the girl.

"He has the rights of one," answered Angela.

"But he hasn't a father's heart. I am merchandise, Angela. Today, salt water spoiled some of the cargo. I have damaged myself in his eyes and in the eyes of some of Porto Bello."

"When you speak to heaven, consider the welfare of your own soul," said Angela, who seemed an endless pattern of quotations. "Why did you talk to the governor and beg for the life of a pirate?"

"Perhaps I was a fool," said the girl. "Well, go to Señor Larreta and tell him that I am able to see him now."

"That is good!" said Angela, putting aside the fan. She hurried to the door and paused there to add: "Remember that words are like wind and rain. If you bow to them, they can do you no harm."

Then she vanished.

"Wait here!" whispered Kildare to the Indian, and was instantly through the casement.

HE was taking off his hat with a sweeping gesture that sent the fragrance of musk lightly through the room, when she opened her eyes. He expected swift action—a leaping up and an outcry—which might make an end of him. Instead, she sat up among the cushions. The trouble disappeared from her face and left it a cold stone of indifference.

"I have come to thank you," said Kildare.

"Thank my mother's blood, not me," she answered. And he was vaguely aware of a picture against the wall, showing a golden-haired woman whose body was crushed in a green satin bodice as though in armor. Her cheeks seemed to be puffed and flushed by the pressure. "Senor Larreta is coming this instant, and he would have you murdered as cheerfully as you murdered the poor people of San Lorenzo. Will you go?"

"I came only to thank you," said Kildare, "but now I see that there are a few other things I must speak about."

"Bravos and bravado never amuse me," she told him. "Will you go? If he finds you here, he will have you killed, and he'll fling me into the street."

"To please you, I would do anything," said Kildare, "but there is that English mother of yours, and I must stay here to find out how much of your heart is English, too. I hear Larreta coming. A thousand times forgive me while I withdraw to your bed."

He was inside it at once, and swept the curtains about him. They were still trembling and whispering when the door opened on Larreta. Through a slender gap between the bed curtains, Kildare saw the Spaniard enter with the step of one who is determined to advance to a goal; and though he attempted an expression of courtesy, it merely gave him the look of a sick man struggling against pain. Angela was behind him; he slammed the door in her face, and the echo went rolling through the house.

"I am sorry to break in on you, Ines," said he.

She pointed to a chair by the window. "Sit down, Uncle Mateo," she said, "I know how polite you are, but sit down and make yourself comfortable. I know how careful and gentle you are in your speech, but now please be frank and say everything that is in your mind."

He seemed about to take the chair, but checked himself suddenly.

"If I said everything at once," he replied, "my throat would burn!"

"Then breathe between the words, and cool yourself," suggested Ines Heredia. "I yearn to hear you!"

"Hatred is a foul thing!" exclaimed Larreta, "and to hate a benefactor is the foulest of all!"

"You should be grateful for it, Uncle Mateo," said the girl. "It adds charm to me. What is a woman without the color of emotion in her? So by hating you, I raise my price."

"Two years of watching and warding over you!" exclaimed Larreta. "Two years of patient care. Two years of faithful devotion to the promise I made to your father. And now I begin to reap my harvest!"

"The soul of my father, poor, kind gentleman! —will thank you one day, Uncle Mateo, for bringing me to the pure, sweet air of Porto Bello and offering me for sale among the merchants of the town."

"I see your method, Ines. You know what you have done, today, and you try to shield yourself by attacking me. You have made yourself a byword and a talking point in the streets! A pirate, a murderer, and a devil has addressed you in front of the crowd, has spoken your name, has leered at you, and by my soul, you have answered him! Oh, Ines," he went on, suddenly turning his voice from rage to something like sorrow, "when I saw you standing in front of the governor, and when I heard you appealing for the life of the villain, I thought it was madness or magic working in you!"

"No, no!" said she. "My head is a great deal too sound to be bothered by magic."

"Your head and your heart were both turned by Tranquillo. It's the English blood in you, that hates all Spaniards, though your poor father was one! And for Tranquillo—with the air of the room still shuddering from the list of deviltries he had named!"

"That poor, ragged starved body? That Tranquillo?" said the girl. She laughed a little, scornfully. "That wretched little jackanapes with his romantic ways which he considers a grace to him, though it sets the world smiling? He lacks the scar and he lacks the mind of a Tranquillo!"

"You saw him fight today!" exclaimed Larreta.

"Juggling, juggling!" said the girl. "A trickster's sleight-of-hand, and three poor, dull-witted fellows."

"You heard him speak before the governor; you saw him sneer at any death we could give him."

"A little soul with an enormous vanity," answered Ines Heredia. Kildare set his teeth hard and freshened his grip on the hilt of his sword. She went on: "He was so flattered to be called Captain Tranquillo that he was willing to die a thousand deaths. And as for revealing where Tranquillo buried the treasure of San Lorenzo, he knows no more about the hidden gold and silver than my cat here!"

A grey cat that Kildare had not seen before came and rubbed against the silken mantle. Larreta smiled or seemed to smile, and then lifted one finger at her.

"You are a cunning little spider, Ines," said he, "and you can make all sorts of webs and deceptive traps with your words, but by one thing I prove that the pirate is really in your heart. You have always hated the odor of musk, until Tranquillo bowed and grimaced and made a fool of you in the lieutenant's house, and waved the perfume through the room. And now, by my blood and honor, I find the same fragrance in your own room, to recall him to you!"

"Angela is growing old and half-witted," said the girl. "She forgot that I detest it and she was wearing some of the stench when she came to me this evening. That is why I ordered her out of the chamber. That is why I shall keep her out, tonight."

"If you despise and loathe this pirate so much, tell me, then, why you appealed to the governor for him?"

"Because I pitied the miserable starveling," said the girl. "Because it touched my heart to see him gesturing and using his vocabulary as though he could make the world think him a gentleman. He was such an actor that people should have thrown coins to him and applauded. Instead of that, they take the silly sham seriously and determine to burn him at the stake. That is too bad! But tomorrow you'll see that I can laugh while the flames cover him."

"There is enough devil in you for that," agreed Larreta. "You could make yourself laugh and be gay while your heart is bleeding. But after this day and what you have done, you may thank God as I thank Him, that I already have contracted you for a fine marriage!"

"You have contracted me for a marriage?" she exclaimed. "Has someone met your price?"

"You speak as though you were a branded ox!" exclaimed Larreta.

"You could not make a beast suffer so!" said the girl.

"Poor fellow!" murmured Larreta. "All that he knows is the voice and the sweet face. But afterwards, what will his life become? Well, well, one must do what one can. You don't ask his name?"

"What do names matter to me?" asked the girl. "I am bought, sealed, ready for delivery. Nothing I can do will change the future. I must only keep some little hope until the last moment. I would rather have the false hope than the true name!"

"I should let you writhe in the torment," said Larreta, "but I am kinder than you deserve. It is Don Pedro! There, Ines—you see what a prize I found for you? Now bless God and your kind guardian!"

"Is it poor young Alvarado?" exclaimed the girl. "Is it Pedro Alvarado?"

"He can be pitied," said Larreta, "but he cannot be saved! I have his money to bind the contract. You are as good as married this moment. No matter what he finds out about you, my girl, not even an Alvarado can afford to throw away five thousand pieces—not in these days."

She slipped back in the chair.

"Pedro Alvarado!" she murmured. "I'd rather be sold to a man I hate, than to an honest gentleman I cannot love. Pedro Alvarado!"

"A month from today," said Larreta, "he sails in the Hispaniola of thirty guns. It brings cannon and powder for the forts at Porto Bello, and it brings young Don Pedro to the arms of his love!"

He laughed, as he ended, but resumed, angrily: "What more could you ask for? When the Hispaniola sails from The Havana, what better husband could it bring to you?"

"Uncle Mateo," said the girl, "you are very wise as a merchant; I cannot expect you to understand that nothing between heaven and earth is as dear to me as my own free choice. In place of my thanks, you have five thousand pieces. What merchant can complain of that exchange? But now I'm very tired. Will you let me sleep?"

"I should have brought you words like whips!" said Larreta. "Instead of that, I bring you the promise of Pedro Alvarado—and this is your return! I curse the day when your father gave me you and the wretched pastures in Castile to have in charge. May the pride in you wither your body, and the devil show in your face!"

He strode from the room, and the door crashed behind him.

THERE was not time for Kildare to move before the door opened again and old Angela entered, wreathed in smiles, that made her more hideous than ever.

"Don Pedro!" she cried. "Young, rich, glorious Pedro Alvarado. Oh, happy, happy, happy, happy!"

She clasped her hands together and put them against her old breast.

"Angela, leave the room!" said Ines Heredia.

"Ah, my lady," babbled Angela, "why are you angry with me? You will not tell me that you could find a finer husband? You will not tell me that you are not the happiest girl in the world? He will take you from Porto Bello away to Castile. You shall have a castle in the Land of Castles."

"With one carpet, three chairs, and no pictures in the whole fifty rooms. I've seen castles," said the girl. "And every castle has three maiden aunts in it, and every one of them fuller of proverbs than you are!"

"Do you mean that you would not choose Don Pedro? But why? But why?"

"Why do horses eat grass, while birds prefer fruit, and fish live on the river mud, for all I know? Angela, I wish to be alone."

"I'll only open the bed. How have the curtains come to be closed?" said Angela.

"I closed them to make one place dark against the mosquitoes."

"I'll just turn down the covers, then," said Angela. She actually had her hand on the curtains when her mistress called, sharply, and the old woman turned away.

"Leave the bed as it is; and go out of the room!" exclaimed the girl. "You've been bribed by my uncle to bait me and enrage me! I see how it is!"

"Bait you?" exclaimed Angela, "Ah, but listen, listen!"

She pointed upwards to gain attention, and into the silence as into a great bowl poured a distant sound, musical, mournful, and dismal.

"The bloodhounds!" said Angela. "Why should they loose them? Have more slaves broken away? Have more prisoners escaped?"

Ines Heredia had run to the window.

"Angela, go quickly and find out what has happened!" exclaimed the girl. "No, never mind. I want to be alone. Whatever has happened is no interest of mine. My head aches, and I'm sick at heart. Don't bother me again, but good-night!"

"Poor child!" murmured Angela. "I've never seen you like this, before. But a girl is half grandmother the instant she's betrothed. Ah well, ah well, good-night and good dreams!"

She went out, shaking her head, and Kildare appeared from inside the bed. He shrugged his shoulders to make the cloak fall in better folds around his body, smoothed the feather of the hat that was in his hand, and brushed back his long, black hair.

"Are you going to stay pruning yourself like a bird on a branch, when the hawks are over your head?" demanded the girl. "Do you hear, Captain Kildare?"

She pointed through the window.

"I thought that the dogs would be singing on the trail, before long," said Kildare.

"Then give yourself wings out the window and over the wall!" she exclaimed. "Suppose they should find you here?"

"The dogs would not take long over me, because as you say I'm a starveling sort of a wretch, but the story would fill the mouths of the Porto Bello gossips for a few days. You'd make a sweet morsel for the old ladies. They'd roll you over their tongues till all the sweet was gone, I suppose."

"Would that please you?"

"Would my own death please me?"

"You love danger and the hard chance," said the girl. "You are one of those fellows who would undertake to parry bullets with your sword and run through fire before it could burn you. So you're standing here, in the fire, waiting for the bullets."

"Who do you think I am?" asked Kildare. 58

"I hope that you're a poor harum-scarum English adventurer. The sort of a lad who was shipped because he couldn't learn Latin, and so he went to sea. That's my hope about you. But I fear that you're really Tranquillo."

"I give you my word that I am English."

"Still you may be Tranquillo."

"Tranquillo or not, am I worse than that fellow Alvarado who buys a wife the way another man buys a horse?"

She kept a thoughtful way about her and seemed to put him and his words together as an entity that could be studied in an impersonal way. A judge might examine a criminal in such a way, disgust and interest going hand in hand.

Her mouth was smiling, faintly, but not her eyes. "You are romantic."

"That's a word you've found in a book," suggested Kildare, savagely.

She turned to the window again.

"They're closer, now. I've seen them. They're a dozen, with a great brindled beast to lead them. They run like greyhounds and they fight like tigers."

He could hear them clearly, like mated bells pealing through the night in a chorus.

"That baying would make quite a noise, inside a room like this," said Kildare. "But I'd rather talk about you, than about dogs. When I saw you in the distance, I thought you were a glorious creature, if only the stone could be turned into flesh. And here in this room I've heard you talk like a very human, spiteful girl. But now you've stuffed yourself out with manners and words that don't belong to you. The woman goes out of you. You're like a foolish boy."

"They are coming closer," said the girl.

The bloodhounds were so much nearer that he could distinguish the individual voices in the pack. Had they passed the cattle compound so soon?

"I hear them," said Kildare, "and I'll continue to enjoy them from this window so long as you're a vain, stiff-backed, high-headed, Spanish grandee. Bah! You have your mother's hair and eyes. There's more English in your little finger than Spanish in all the rest of your body. Confess it. Be honest!"

"Suppose that I did?" she suggested.

"Then go one honest step further and confess that I am more to you than a poor carrion crow with half its feathers molted away. I'm not a beauty, like that Don Pedro. I'm covered with the prison grime, now, and my hands have not been clean all the days of my life, but my heart has been clean, and that heart could love you. Not as you are now, with your chin up and a sneer on your pretty lips, and your eyes like blue stones; but I could love the truth of you that's inside. I could worship it, and serve it, and find you a happiness that would keep you singing the rest of your days, by God."

"Mother of heaven!" groaned Ines Heredia. "Listen!"

For the dog pack seemed to have turned a corner not very far away, and the clamoring rang out close to them.

Kildare sank into a chair and laid his sword across his lap.

"They have throats," said he, "I suppose they have teeth to match, also."

Suddenly the strength seemed to crumble out of her. She threw out her hands, crying in a changed voice: "What do you wish me to say?"

He stood before her.

"Strike your hand into mine like an honest soul, and say: 'Ivor, Englishman or Spanish man, there is something in us that cries out to each other. God give us the luck of a second meeting!'—"

The door flew open. A great yellow-faced half-breed broke into the room, crying: "Señorita Ines, the town is up and Captain Tranquillo has escaped and—"

He saw Kildare, as it were, by the light of the sword that was flashed in his face, and his knees sagged under his weight.

"Go to the window," said Kildare.

The terrified servant obeyed, cringing along the wall, whining:

"Lady Ines, speak for me! Speak for me!"

"I'll not hurt him," said Kildare, "but I'll take him where his tongue cannot do any harm with telling what his eyes have seen tonight. Luis, take him out through the window, and muzzle him!"

Instantly the vast bronze hands of the Indian reached into the room, seized upon the half-breed, and drew him out. There was a muffled outcry, and silence. Only the yelling of the bloodhounds now seemed to be ringing under the very wall of the house.

Kildare turned to the girl. She was the color of fire. Like flame she was trembling, but she caught his hand suddenly and stammered: "Ivor, Englishman or Spanish man, there is something in us that cries out to one another. God give us the luck of a second meeting!"

Kildare put his arm half around her, so near that he could feel the shuddering of her body.

"Whether God gives it or not, I'll find that fortune for us," he cried.

He dropped on his knees. He kissed both her hands. He looked up once into her face. And then he was through the window and beside the Indian.

Running lights came up the street, dancing, swimming. The footfalls were so many that they made a sound like the heavy beating of rain on a roof.

The forward part of that wave reached the side of the house of Larreta, and there the cry of the pack was muffled away into snuffling, whimpering noises. Kildare heard them clearly as he dropped to the ground on the farther side of the building. The mulatto fell sprawling beside him, and then came Luis, making small of that leap like a great yellow mountain lion. And like a mountain lion picking up a lamb, so Luis raised the Negro by the scruff of the neck.

"The way to the best canoa in the harbor— show us that!" commanded Kildare.

The mulatto made a faint yelping sound like a rabbit that cannot utter the death screech because the teeth of the hound are in its throat; then he raced through the darkness of Porto Bello, swaying with speed. High over them the alarm bells broke out with a frightful clamoring. From windows and from opening doors pale whips of light lashed the trio as they ran, Kildare and the house servant first with Luis striding easily at their heels like a grown man who pursues two scampering boys and may take them when he will.

They slopped through the mud of an alley that was black as the throat of a cannon and threw them out suddenly upon the open beach. The stench of the rotten slime on the mud banks was in their nostrils and the harbor waters were beyond. Lights gleamed in smooth shallows under the lee of the hills, but a strong land-breeze darkened all the rest of the bay, and slapped the waves against the shore in a hurrying rhythm.

There were no sails in view, only naked masts in threes or twos and the tapering, bending poles of felucca rigs. A number of these were close by, moored at the little piers which fishermen had built, and toward one of these the mulatto led the way. It was a forty-foot canoa, with a wattled awning built aft and the long whip of the mast swinging slowly back and forth.

Kildare slashed the mooring ropes as Luis and the mulatto leaped aboard. Two frightened shadows, a man and a boy, ran out from beneath the awning, but they had not thought of resistance. The fisherman began to moan out broken prayers and vows; the son closed his teeth and sobbed behind them with a sound like that of a deserted puppy complaining far away. Yet the pair of them were instantly at work getting out the sweeps, thrusting the canoa from the pier, and loosing the sail.

"I am Captain Tranquillo. You live with me or you die with me tonight!" Kildare shouted at them, and that was enough to make them burst the tendons of their backs with their efforts, for the bloodhounds were on the beach, now, the deep notes of their baying spreading out with echoes over the bay, and behind them came the staggering lights and the shadowy bodies of the pursuers. It seemed as though all of Porto Bello were pouring out on this quest, and to urge them on the alarm bells beat from the church towers like so many hearts that race with fear.

When that crowd of man-hunters at last saw the quarry on the pierhead, they loosed the bloodhounds and the great beasts came with a rush, their feet pounding, their nails scratching on the wooden planking of the pier.