RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

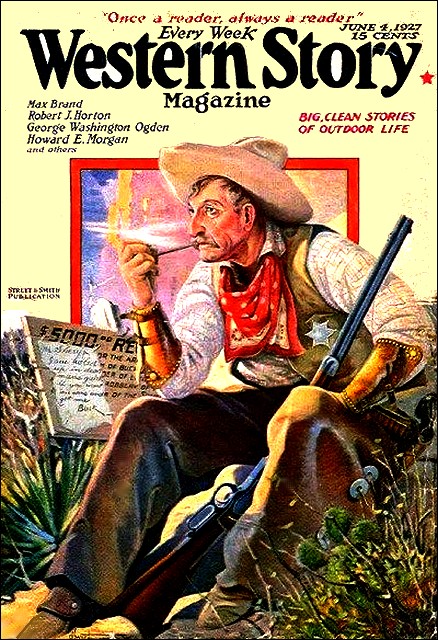

Western Story Magazine, June 4, 1927, with "The Desert Pilot"

ONE step beyond Billman lay the desert; young Ingram, minister of the Gospel, took the single step and sat down in the shadow of a rock amid the wilderness. Already one needed the shadow; for though the sun was barely above the horizon—had lost the rose and gold of dawn only the moment before—it was now white with strength and flooded the desert with a scorching heat. When the knee of the Reginald Oliver Ingram projected into that heat, he withdrew it. It was as though a burning glass had been focused neatly on it. He looked down, half expecting to see the cloth of his trousers smoking. And this heat would increase until early afternoon, after which its power would diminish by almost imperceptible degrees. Until its face turned red, the sun would flood the desert with white fire.

Like shimmering snow was the face of that desert, except that snow is fixed and still, whereas the sands were covered with little wraiths and atmospheric lines. They quivered and throbbed, as a white-hot iron quivers and throbs. Mr. Ingram raised his eyes from the paper on his knee and took more careful stock of all that lay around him. He had been in Billman only a few days—not long enough to preach his first sermon, as a matter of fact—but he had come across the continent with a suitcase filled with books. From their well-studied contents he could name yonder gigantic saguaro, and the opuntias, surrounded with a halo of ivory sheen in the strong sunlight; and he knew also the deer-horn cactus not far off, the greasewood and mesquite on the sands.

To name all the living things in sight was to give an impression of companionable multitudes about him, but as a matter of fact all he observed was hardly more to the desert than is an occasional mist of white to the broad, pale bosom of the summer sky—nothing to give shadow, for the intense sun will look through the spectral clouds when it stands directly above them. So it was with this plant life—a few fantastic forms, looking like odd cartoons of animals, thrust in the sand with arms or legs extended foolishly—and yonder patches that looked like smoke against the sand.

But Mr. Ingram looked upon all these signs of desolation with an eye that was unafraid; for he carried about him a spiritual armor that blunted the edge of every danger and every painful instance: When he left the theological school, a wise, ancient and holy man had said to him: "Now you are about to enter the world. Leave some of your books and bookishness behind you. Be a man among men; trust the angels a little less and man a little more!" The Reverend, Reginald Ingram smiled as he thought of this speech. For, looking across the desert, it seemed to him that the hand of God was visibly revealed, and he penned hastily and strongly the first words of the sermon which he would deliver later that morning: "Dear brothers and sisters whom I meet here at the edge of our civilization, we have gone very far from our old homes and we have left many of our old ideas behind us; we even have stepped beyond the reach of the law, I suppose; but we have not passed beyond the reach of God, and I wish to speak to you today concerning the signs of His loving Fatherhood which are scattered about us, though the signs are unregarded by most of us, I fear."

Having finished this burst, he paused, knitting his brows with the farseeing effort of a poet or a prophet. He glanced then to the tall forms of the San Joaquin Mountains far to the north and east, now washed with tides of light through air so pure and thin and dry that he could see the shadows which the boulders cast and almost pick out the individual trees which straggled up to timber line. Beyond that line was a band of purple, and above the purple lay the glittering caps of snow and eternal ice which, like a cup of haunting coolness, were offered forever to the sight of the parched desert beneath. A gleam of wings near by drew his attention to the fluttering butterfly which wafted aimlessly up and down close to the sand, all jeweled and transparent in the powerful sun.

The rapid pencil of the Reverend Reginald Oliver Ingram ran again over the paper: "Here, beyond the law, conscious of our own strength, and aware of the apparently cruel face of nature, we prepare ourselves for battle. But our Father in heaven permits life without battle, and sends out unarmed multitudes, who persist and give the earth gentleness and beauty. Consider the butterfly that flutters softly over the desert, harmless, soft, brilliant in the sun—"

He looked up for inspiration to complete his sentence, and noticed an active little cactus wren, balanced on a hideous thorn of the deer-horn plant.

"—or the wren," dashed on the swift pencil of the minister, "spreading his wings that the sun may flash through them and make of him a double jewel—"

He looked again, and saw almost at his feet a little yellow beetle looking as hard and glittering as a piece of quartz.

He touched it with the eraser of his pencil; it was, indeed, like pressing on a rock.

"—or the beetle," went on the writer in glad haste, "like a nugget of gold on the face of the desert. But these defenseless ones which can harm nothing and which give joy to the world teach us that we, also—"

Something whirred through the air; the butterfly was clipped in two by the long, wicked beak of the wren. The quivering halves tumbled almost at the feet of the watcher, but since he had sat quietly so long, the bird seemed to accept him as a part of the landscape, and pursuing its prey, gobbled up the feast and was gone.

Mr. Ingram looked down at his page and puckered his lips in thoughtful regret. However he continued: "Teach us that we, also, have been placed in the world to make it beautiful with the work of the heart and not terrible and dangerous with the work of the hand. Gentleness is mightier than pride—"

He paused again, and saw that the golden beetle had encountered a smaller insect. Whatever it might have been, it was now unrecognizable. For the yellow beauty, beating its shardlike wings with joy or anger, was already tearing the weaker thing to bits.

"Gentleness is mightier than pride," insisted Mr. Ingram's pencil, "and the triumphs of the strong are, in reality, not triumphs at all; they are soon avenged!"

He completed the sentence rather grimly, and another whir in the air attracted him once more to the wren, which had dropped like lightning from its bower of thorns and attacked the golden beetle.

There was no battle. The beetle depended on the toughness of its armor, and depended in vain, for soon Ingram could hear the crackling of this natural coat of plate, and the beetle presently disappeared. Thereafter, the wren flitted onto a stone, and sat there opening its beak wide, pulling in its head, and ruffling its feathers as though it found its recent tough meal very hard to digest.

"I hope you choke on it!" said the minister sternly to the bird. And he wrote: "Vengeance is near at hand, and we are being watched by a higher power. The victories which we win are always just around the corner from defeat!"

So wrote the man of God, and he had barely finished this sentence when new ideas forced themselves upon him, and he added fluently: "Put off your guns and knives! The God who rules heaven and earth is a God of peace. Trust to Him, and He will lead you out of your troubles. What blow can threaten you that He will not ward away?"

He felt a glow of triumphant conviction as he finished. At that instant he heard a hiss like a volley of arrows whirring above him; a shadow slanted with incredible speed past his head; the wren was blotted out; there was a shrill scream, and away winged the big hawk which had dropped from the blue—and now sailed back into it, carrying a little tuft of crimsoned feathers in one set of talons.

Ingram watched the bird of prey rising gracefully and rapidly, climbing the sky in great spirals. It reminded him of the men he had seen in Billman since his arrival—lean, quiet men, who, when they were roused to action, struck with sudden and deadly stroke. And all at once he felt more than a little helpless, for it seemed to him that he could hear the chuckles of his audience when he told them later that morning that there was no value in might or in the strong hand.

What lessons of gentleness could he derive from that nature where the smaller beetle was eaten by the larger, the larger by the wren, the wren by the hawk which towered in the sky, and the hawk, in turn, perhaps struck down by the soaring eagle? However, he would not be downhearted at once.

He followed the flight of the hawk past the cold summits of the San Joaquin range, and as he did so, the glory of the great Builder possessed his imagination. New ideas crowded upon him and drove his pencil at breakneck speed until he had covered several sheets; and when he stood up from the shadow of the rock and faced the glare of the sun, the sermon which had haunted him since his arrival at Billman was completed.

He glanced at the pages from time to time as he wandered back into the town; and before he reached his shack, he knew that the thing was firm in his memory. At his door he stood for a moment and watched the wind roll a cloud of dust up the street more swiftly than a horse could gallop. So let the idea which had come to him on this morning sweep through the minds of his auditors, and freshen in them the almost obliterated image of their Creator!

He entered his little house and was startled by the figure of a Dominican monk, whose fat body was covered with a gown of not over-clean rusty black, girded with a long cord. The monk turned and grasped the hand of Ingram.

"Good morning, Mr. Ingram," said he. "I am Brother Pedrillo. I've come to welcome a fellow-worker to Billman."

Ingram did not like the use of the word "fellow-worker". Young Mr. Ingram had been bred to a faith which does not look kindly upon the Roman Catholic creed; but in addition, he felt in himself so much aspiring vigor, such a contempt of the flesh, that to be yoked with Brother Pedrillo was like harnessing an ox in the same team with Pegasus.

So he turned away, busied himself putting up his notes for the sermon, and revolved swiftly in his mind the attitude which he should assume. However, the Lord works His will in mysterious ways. The Reverend Reginald decided that he would force himself into friendliness with the Dominican. Humility is ordained very early in the Gospel.

HE invited Brother Pedrillo to take a chair, and so became aware of the shoes of his visitor. They were made of roughest cowhide, but even that durable material was worn to tatters. The fringe of his robe, too, was worn to rags, and the bald head of the monk had been burned well-nigh black. At least this was a man who was much in the open air. The heart of young Ingram softened a little.

"You read philosophy, I see," remarked the monk.

"Don't you?" queried Ingram, rather sharply.

"When I was just from school, yes," replied the Dominican. "But afterward, I let the thing slip. It was quite useless to me in my work."

"Ah!" said Ingram coldly.

"Not," added the other, "that philosophy cannot be translated into the language and the acts of the man in the street; but I haven't the time nor the intelligence to do the translating. My work takes me long distances," he explained more fully, "and my tasks are placed far apart." He pointed to his battered shoes.

"You don't live in Billman, then?" asked Ingram.

"I live in a district a hundred miles square."

"Hello! Do you walk that?"

"Sometimes I get a lift in a buckboard. But my people are very poor. I must walk most of the days."

"A frightful waste of time," suggested Ingram.

"For those who live or for those who die," said the Dominican, "time is of little importance in this part of the world. Have you watched the buzzards?"

"Buzzards?"

"They wait on the wing a week at a time, without water, sailing a hundred leagues a day, perhaps; but, if they are watchful, finally they find food. It is that way with me. I go from village to village, from house to house. But if I find one good thing a month to do, I am satisfied. The rest of the time, I wait on the wing, as you might say."

He looked down at his round stomach as he spoke, and laughed comfortably, until he shook from head to foot.

"I should think that you could settle down here," said Ingram with enthusiasm. "There are scores of Mexicans here. The number of their knife fights, you know—I beg your pardon," he added, "I don't want to appear to give advice."

"Ah, but do it! Do it!" said Pedrillo. "As we grow older we find little advice to take; and a great many occasions for giving. So say what is in your mind."

Ingram looked at the other a little more closely, for he feared that he was being mocked; but he met an eye so transparent and a smile so genuine and childlike that he could not help laughing in return.

"There is nothing I can say," he declared at last. "Except that it seemed to me that there was enough in Billman to keep you busy every moment of your time."

"In this little town," said Pedrillo, "my people shift so fast—up to the mines and back again, in and out—that I can do little except marry or bury them as they pass. If it were a settled place, then I could take a house here and live among them until I became really a brother to them. But as it is, the mines fill their pockets with money. They have plenty to spend on food and tequila, and something left over to gamble and fight for. Their minds and their hands are so filled that they have no need of me except when they are about to marry or to die. If I were to settle among them now they would forget that I am here. I would be a shadow to them. But since I come from a distance, at rare intervals, I am something more. They listen to me now and then. That is all I can expect. I am not ambitious, Mr. Ingram. But you have your own people, and they are not mine. All of mine will hear me—at least two or three times in their lives. Some of yours will never hear you at all. But a great many of them may take you into their everyday lives. That is the greater good. Unquestionably, the greater good. Ah, well, I must accept my destiny."

His words were a good deal more serious than his manner, for he smiled as he spoke.

"But," he added, "I have never had gifts. Unless it is a gift to listen to people's sorrows. You, however, can mix with your kind and command admiration among them."

"Why do you say that?" asked Ingram, frowning a little, as one who does not like to receive idle compliments.

"You are big," said the Mexican; "you are young, and you are strong. The men here are rough; but they cannot afford to scorn you."

He pointed, as he spoke, to a little silver vase which stood on top of the bookshelf, a pair of boxing gloves chased on its side.

Young Ingram smiled faintly and shrugged his shoulders.

"That was before I had any serious purpose in life," said he. "That was before I found myself. Now I'm a man."

"How old are you?"

"Twenty-five, almost," said Ingram.

Brother Pedrillo did not smile. "And how did you come to find yourself?" he asked gently.

Ingram found it strangely easy to talk about himself to this brown, fat face, these inactive but knowing eyes. He rested his elbows on his knees and looked into the past.

"I was smashed in a football game, and played too long afterward. It put me in the hospital. I had the germs of a fever in me at the time, and that gave the sickness a galloping start. It was a long struggle. But in the intervals, when I was not delirious and when I realized how close to death I lay, I wondered what I had been doing with myself for twenty years. Twenty long years, and nothing done, nothing worth while! A few goals kicked. A few touchdowns. Some boxing. Well, I determined that if God spared me I would give something to the world that was worth while. And when I could call my life my own, I began studying for the church."

He checked himself and looked rather auspiciously at the Brother.

"I seem to be chattering a good deal," he suggested.

"Talk is good," said the older man with conviction. All at once he began to whistle a thin, small note. Ingram turned and saw a little yellow-backed lizard lying in the burning sun upon the threshold. It lifted its head and listened to the music. "Talk is good," added the friar, with a nod of surety.

He stood up.

"We begin to know each other," he said.

"I want to ask you the same question that you asked me," said Ingram. "How did you happen to select your vocation?"

"But I had nothing to do with it," answered the friar. "My mother gave me to the church. And here I am," he added, and smiled again. "Whatever I can do, ask of me. I have little power. I have little knowledge. But I know something of the strong men who live here."

"These ruffians!" cried Ingram rather fiercely.

Brother Pedrillo raised a brown hand.

"Don't call them that. Yes, call them that if you will. It is always better to put it into words than to leave it buried in the mind. But except for a rough man's act, would there be a church here now? Would you yourself be here in the desert, my brother?"

Ingram bit his lip thoughtfully.

"I don't know what you mean," he replied frankly.

"You don't know?" asked Pedrillo, his smile fading. And for a single instant his eyes were keen and cold as they searched the face of his companion. "Perhaps you don't," he decided. "You have not heard how your own church was built?"

"By a man named William Luger. I've been here only four days, you understand."

"Do you not know how he came to leave the money for it?"

"No. Not yet."

"So, so!" murmured the friar.

He sat down again and rolled a cigarette, whistling the small note to the enchanted lizard at the door. He made the cigarette like a little cornucopia, for such is the Mexican fashion. And Ingram saw, with a little disgust, that the fingers of the holy man were literally painted orange-yellow by the stain of nicotine.

"Let me tell you," said the friar, beginning to blow smoke toward the rough beam of the ceiling. "Billy Luger was a man typical of this part of the world!"

"A little better than that, I hope," said Ingram, turning stiff.

"No," replied the Dominican. "He was just that. He had spent thirty years branding cattle—his own or ones he borrowed for the occasion. Finally he dipped into mining, when the rush started toward the San Joaquin silver and the Sierra Negra gold. He made a few thousand and was celebrating a trip to town one evening, when he got into a card game with 'Red Jim' Moffet. Moffet shot him, and it was while Billy lay dying that he made up his mind to leave his money for the founding of a church. That's the story. And that's what brought you here."

"And the murderer?" asked Mr. Ingram hotly. "He was hanged, I trust?"

"You are a sanguinary young man," smiled the Dominican. "But these people are fond of killing with guns; they rarely kill with a rope. No, Moffet was not hanged. He's still alive, prosperous and well. You'll meet him around the town."

"A most extraordinary tale," said Ingram, breathing hard. "Was no attempt made to bring his killer to justice?"

"The fact is," said the friar sympathetically, "that Moffet accused Billy of having a card up his sleeve during the game. And I believe that the bystanders agreed with Red, after the smoke blew away."

Brother Pedrillo rose again.

"You are going to exercise much influence from the start, I know," said he.

"And on what do you base that?" asked Ingram, again antagonistic.

"Where the ladies of the town go, the men are sure to follow—though sometimes at a little distance," said Pedrillo, and he stepped out into the blast of the sun.

It glistened on his bald head as upon brown glass.

Once more the friar waved adieu, and trudged down the dusty street, leaving Ingram of two minds as he stood in the doorway. He could not quite make out the import of that last remark. It sounded suspiciously like a touch of sarcasm, but he could not be sure. At length he turned to complete his sermon. It was not easy. He had to set his teeth and force his pencil on. Because from time to time across his mind came the vision of a card game—and one man with cards up the sleeve!

WOMEN? He had not guessed that there were so many in the entire town, aside from the Mexican section across the creek. They filled more than half the front part of the church, whispering, buzzing, and then settling down to watch his face with a curious insistence, until he began to feel that they were hearing not a word.

He lifted his eyes from them and directed the strength of his little oration toward a dozen men who remained as far back as possible on the benches, huddling themselves into the shadowy corners.

They were listening, and they did not seem convinced by this talk about peace. Now and then they looked gravely at one another. Once or twice the Reverend Reginald Ingram thought he saw a faint smile. But he could not be sure. Only he knew that the church now began to seem extremely small; and that the sun beat upon it with a terrific force. It was hot, very hot; and he wanted a cooling wind to pour in and bring him relief.

Well, that small miracle was denied for his gratification, and Ingram centered his attention fiercely on his sermon—bulldogging it through, as he often had done on the football field. Yardage on a football field, however, is chalked off with convenient white lines. Yardage in a church is a different matter. One may be under the goal posts one instant, and fighting to keep from being scored on the next.

However, he drew his parallels. The yellow beetle and the gay little wren were called upon to furnish a metaphor apiece. The cruel hawk was not mentioned at all. And gradually he established his own conviction in the picture he was drawing of peace on earth, and good will among all of the men living upon it. He felt that he was drawing his audience together a little more. As for the hulking men in the rear—let them rise and sidle with creaking boots toward the exit. Not one of the feminine heads before him turned to watch them go. No, all were feverishly concentrated upon him. They were brown faces, indubitably Anglo-Saxon in spite of their color. And the eyes seemed strangely blue and bright by contrast. He began to feel that never before had he seen so many intelligent women gathered together. For, if the truth must be known, Mr. Ingram looked down upon the other sex. They rarely bothered him. No woman can talk football, and few can talk of religion with much conviction.

The minister ended his sermon, and the organ responded in squawks of protest to the organist who was trying to furnish music to close the service. However, the little crowd did not depart, and Ingram, descending from his throne, was softly enveloped in a wave of organdies and lawns that brought a fresh, wholesome laundry smell about him.

The ladies introduced themselves, and he listened gravely and earnestly to their names. If he was to work with such material as this, then it behooved him, by all means, to come quickly to the knowledge of it.

They had enjoyed his sermon, it appeared. They had enjoyed it, oh, so much! Everything he said was so true. If one only stopped to think! How well he understood the desert, and their problems! Some one was asking him to come home to lunch. And then another, and another.

A girl with very pale, blonde hair and very blue, blue eyes seemed to brush all the others aside, with her gesture—though she was a little thing—and stood directly before him, smiling up.

"They have no right to you," said she. "My poor mother couldn't come, and she wanted me to remember every word you said. As if I could do that, in my silly head! So you have to come home to lunch with me. Go away, Charlotte! Don't be foolish! Of course Mr. Ingram is coming with me!"

Even among the others it seemed to be taken for granted that Mr. Ingram would, of course, go with her of the pale hair and the extraordinarily blue eyes. They gave up. And she carried him off from the church.

Indeed, he had a distinct impression that he was being carried. He could remember her name by a little effort; in fact, it was a very odd one. She was called Astrid Vasa.

As they came from the church a tall man, who looked compressed by his store clothes and nearly strangled by his necktie, approached them, with a red-faced grin for the girl.

"Come along, Red," said she. "This is Red Moffet, Mr. Ingram. Red, this is Mr. Ingram. You know. He runs the church, and everything. Don't you, Mr. Ingram?"

She looked up at Mr. Ingram at the conclusion of this infantile question, and shut out the view of Red Moffet with a parasol which slanted over one shoulder, and which she was spinning with a very delicately made little hand. Ingram wanted to frown, but he couldn't help smiling; which made him more determined than ever to frown. And so his smile grew broad!

"Red works in a mine, or something," explained Astrid Vasa, shrugging a shoulder in the direction of Mr. Moffet.

"I own a mine," said Red. "It's kind of different."

He was offended, of course. It occurred vaguely to Ingram that Mr. Moffet seemed very offended. For his own part, he wondered what his attitude should be toward the man who had killed the founder of the church over which he now presided. But after all, it was said that the other cheek must be turned. Ingram, concentrating on the thought, set his teeth.

They reached a picket fence in front of a little unpainted house. Few of the houses in Billman were painted, for that matter. "I dunno that I'll be comin' in," said Red Moffet gloomily.

"You better come along," said Astrid. "We gotta couple of the best-looking roosters that you ever saw for dinner."

"I'm kind of busy," said Red, more darkly than ever, "so long!"

And he rambled down the street with a peculiarly awkward leg action. It reminded Ingram of the stride of a certain tackle of his college team, a fellow uncannily skillful in getting down the field under a kick, and marvelous in providing interference. He was more interested in Red Moffet from that instant.

"He's got a grouch on," confided Astrid. "He always wants to be the whole show since he got his silly old mine. C'mon in!"

The screen door screeched as it was kicked open from within. A burly gentleman in shirt sleeves stood before them.

"Hello; where's Red?" asked he in a pleasant voice.

"Dad, this is Mr. Ingram, the minister, and he's just been persuaded to—"

"Hullo, Ingram! Glad see you. Where's Red, sis?"

"I dunno. He got a grouch on and beat it. I can't be bothered—all his notions."

"You little simp," said the inelegant Mr. Vasa, "you'll be havin' him slide through your fingers one of these days."

"Dad, what are you talkin' about?" exclaimed Astrid, very pink.

Her sire looked from her to her companion and grunted.

"Humph," said he. "Is that it, eh?"

"Is that what?" asked Astrid, furious.

"Aw, nothin'. C'min and sit down and rest your feet, Ingram. Lookit—ain't it like a fool girl, though? Shufflin' a boy like Red around? Know Red, I guess?"

"I've barely met him," said Ingram, with reserve.

"Have, eh? Well, he's all right. Kind of mean, sometimes. Yep, mean as hell. But straight. Awful straight. Why, that kid's got a half million dollars' worth of mine up in the San Joaquin. Wouldn't think it, would you, to look at him? But I've seen it. Make your mouth water. Lord knows how deep the vein runs. Maybe take out a hundred thousand a year for a hundred years. Can't tell. And here's our Astie with a gent like that in her pocket, and chucking him away over her shoulder. Finders keepers! Sis, your're a simp. That's all!"

"Father!" cried Astrid, dividing the word into two distinct parts, each concealing a world of meaning. "D'you know that your're talkin' to a minister, with all your profanity, and—and talking foolishness about Red Moffet? Who said I had him in my pocket? Who wants to have him there? I'm sure I don't. And—what do you mean by talking like this to a perfect stranger?"

"Aw, don't step on your own toes to spite me, sis," suggested her father, grinning. "Besides, maybe Ingram ain't going to be a stranger for very long. How about it?"

This extreme directness embarrassed Ingram. He searched his mind—and found nothing with which to respond except a smile which might have received varying interpretations. Astrid retreated to regain her composure and let her blushes settle down to a normal pink.

"She's a good kid," pronounced Mr. Vasa, "but careless. Dog-gone careless. Far as that goes, though, this here is a land of carelessness and accidents. Billman's an accident, you know."

"An accident?" said the polite Ingram.

"Sure. You know how it started?"

"No. Started?"

"Sure. A town has to start, don't it? Aw, you're fresh out of the old States, where a town put down roots so long ago that there ain't any story left about it except a legend that's a lie. Well, things ain't that way out here. We ain't scratched many wrinkles on the desert yet, and the only ones we've made are all new. Take Billman. Old Ike Billman was started for the San Joaquin range when the mines opened up there. Had a string of wagons loaded with stuff to sell for ten prices, the old hound! But he busted down here. Broke a wagon wheel. Before he got it fixed the boys were rushing through on the way for the San Joaquin on one side and for the Sierra Negra on the other. They wanted supplies, and wanted 'em so bad that price was no object. So Ike, he piled out his stuff and sold it out here just as good as he could have done if he'd marched all the way into the mountains. Then he put up a shack, and began freighting more stuff—not to the mines, but here. Other folks followed the good example. Then some of us have got interests in both places—San Joaquin and Sierra Negra—so we live in this halfway station. Y'understand? That's how Billman started growing. Just plain accident."

"You're a mine owner also, then?" said Ingram in a polite attempt to discover the interests of his host.

Astrid returned. She had studied her smile before the mirror and felt that it would do.

"Sure, I'm a mine owner. I mean, I got shares in a couple of mines. I was a blacksmith when I come out here to—"

"Dad," put in Astrid, "I don't see why you have to rake up all the old family history. I'm sure Mr. Ingram isn't interested."

"Why not?" asked Vasa. "Ain't it honest to be a blacksmith? I never was in jail—except overnight. I got nothing to be ashamed of. It's a darn good trade, Ingram—blacksmithing. The money that I made out of it was honest. But this mining game—just luck! I took a couple of flyers at it. And they both connected with the bulls-eye. There you are. I'm gunna be pretty well off. I could sell out now for a hundred thousand. Maybe more. Not so bad, eh? But I guess I was just as happy hammering iron, hot or cold. It's the thing that you're cut out for that counts. Luck ain't apt to make you happy, Ingram. I'll never be worth shucks as a miner. But I could lay a shoe on the hoof of a horse so fine it would make you stare. You come and watch me some day. I still put in a few hours in the old shop now and then, just to keep my hand in."

Mrs. Vasa, as small as her husband was large, rather withered but still good looking, stood in the doorway. She was flushed from her work in the kitchen, and wiped her hands on her apron before she greeted the minister.

"Astie says that the sermon was just wonderful. I'll bet it was," said Mrs. Vasa. "Now you come along in and have a bite of lunch with us, will you? I'm mighty glad to have you here, Mr. Ingram. I was just too busy to get to church this morning. Church is kind of new in Billman, you know. And it takes a body a time to get into the run of going again. But my folks were mighty regular; they never missed a Sunday hardly. I always think it does you sort of good to go to church. Cools you off, you know, and it's restful. D'you think that you're gunna like Billman, Mr. Ingram?"

This was poured out effortlessly, rapidly, as they got to the table and sat down. Mr. Ingram could have made a quick answer to the final question, but it was not necessary to answer questions in this house. Between the head of the house and his wife there was no room left for silent spots.

Afterward they had music. Ingram sat down to supper, and remained to listen in amazement.

"Astie, she sings like a bird; dog-gone me if she don't!" said her father.

And that was exactly what she did. She accompanied herself on the piano. As smoothly as speech flowed from the lips of Mrs. Vasa, so song poured from the throat of her daughter, and the accompaniment bubbled delightfully in between.

"Dragged that dog-gone piano clean out from Comanche Crossing," declared Vasa. "And I never regretted what it cost, derned if I have. Now ain't it a treat to have a girl that can sing like that? She ought to be on the stage, where thousands could enjoy her. Honest, she should. But she'll never get there!"

"Why do you say that, dad?" asked Mrs. Vasa.

"Because she's got her career all mapped and laid out for her right here in Billman," said the head of the house.

"Career?" asked Astrid. "What sort of career?"

"Humph!" said the ex-blacksmith. "Breakin' hearts, or tryin' to!"

"Dad, you're just—" cried Astrid.

"You might let the poor girl—" began Mrs. Vasa.

"Aw, be still!" said Vasa. "Ingram's gunna know about you pretty quick, if he don't already. I tell you what, Ingram. If that girl hadn't been born with a pretty face, she would have amounted to something. But she's got just enough good looks to spoil her. Her heart's all right. But her mirror keeps tellin' her that she's Cleopatra."

"I hope you don't pay no attention, the way that he keeps on about his own flesh and blood," said Mrs. Vasa to her guest.

Ingram smiled. But it was with an effort.

"Tune up, sis," commanded Vasa. "Go on and tune up, will you, and stop shaking your head at me. It ain't gunna change me. I'm too old to change. Take me or leave me. That's my motto. Maybe there's rough hammer marks on me, but the stuff I'm made of is the right iron, I think. Go on and sing, will you? Gimme some of the old ones, where you don't have to listen too hard. 'Annie Laurie', that's about my speed. Somethin' nice and sad. Or 'Ben Bolt'. Dog-gone me, if that ain't a swell song, Mr. Ingram. What you say? 'Ben Bolt', sis. And make her nice and sobby!"

They had 'Ben Bolt' and 'Annie Laurie', also.

And afterward Mr. Vasa went to sleep in his chair and snored. And Mrs. Vasa announced that she would go and close her eyes for a minute. Such a warm afternoon! Mr. Ingram was glad to excuse her. He sat in the shade of the house with Astrid.

"I guess you think we're terrible people," said Astrid sadly, "the way that dad carries on."

"No," said Ingram earnestly. "I don't think so at all. I like him. He doesn't pretend. He's honest. I like him a great deal, you know."

It was pleasant to see her face light. Her smile was like her singing, charming beyond words. And Ingram wondered how such a flower could have grown in such rocky soil. It made him feel, too, the value of that background of culture which enables one to appreciate the great and the simple, the complex and the homely.

"He thinks I ought to go on the stage," said Astrid. "But I'll never get there. No, I'll have to stay here in the desert."

"Do you want to go?"

"I don't know," said she. "Only—I'm so lonely here."

She looked up at him with sad eyes.

"Poor child!" said Ingram, melting. "Lonely?"

He leaned a little toward her. Charitable kindness is commanded directly.

"Oh, lonely, lonely!" sighed Astrid, still looking into his face with suffering eyes. "Do you know—but you wouldn't want me to tell you—"

"I think I would," said the gentle minister.

"You know such a lot, and you're so wise and clever," said Astrid, "you would laugh at me!"

"I'm none of those things. And I won't laugh."

"Really you won't?"

"No."

"Well, of course I know a lot of people here. But though there are lots of them to chatter to—well, perhaps you won't understand—there's really not a soul for me to talk to."

"Poor child!" said Mr. Ingram. He felt that he had said that before, but it was so true that he could not help repeating it. "Poor child, of course I can understand!"

"Until you came, Mr. Ingram. And I really think that I could talk to you."

"You shall, my dear. Of course you shall, whenever you please."

"And you won't laugh at me?"

"Certainly not."

"And when I tire you, you'll just send me away?"

"We'll see about that," said he, tolerantly.

"Ah, you could understand!" said Astrid. "The others—they just think that I'm always gay. They never guess, Mr. Ingram, how close—the tears are—sometimes!"

Yes, yes! But he could guess! He could see the tears now, just welling into her eyes. And he dropped a large, strong hand over her little one.

They sat in silence. He felt prepared to face the world. He felt the ability to endure, to suffer. And some day, when he had children, he was sure that he would be able to raise them tenderly, and well.

THERE followed for Ingram several days of severe labor, for he was establishing his parish, enlisting the interests of various people, and accepting sundry contributions which poured in with amazing speed for the first public work which he attempted. This was the establishment of a little hospital.

Sick men came down constantly from the mines in the San Joaquin, or in the Sierra Negra, and from Billman they were in the habit of taking the long stage journey overland to Comanche Crossing, where they could get medical attention of a kind. Ingram saw the possibility of putting up something which would be more than a way-station for the sick. And his idea was taken up enthusiastically. Mexican labor made the adobe bricks rapidly on the banks of the creek, and the terrible sun dried them to the proper strength; after that, skilled Mexican workers raised the walls of the hospital. There were three rooms, and they were built of generous size, with lofty ceilings and thick walls, so that the sun's heat would not turn the place into an oven. For bed equipment there were various improvisations, and many donations were made after Ingram set the example by giving up his own cot. If he were willing to sleep on the floor, others would be equally brave in facing uncomfortable nights on the boards. For doctors there was no want; for several of them were among the men who had tried their luck in the gold rush and had run out of funds. They returned to their professional work and supplied the hospital with a competent staff. The Mexicans made excellent nurses, assisted from time to time by volunteers from among the ladies of Ingram's congregation. As for the funds to pay for all this necessary labor and expenses of various kinds, the inhabitants of Billman willingly dug deep into their purses, and in addition came contributions from all the mines.

The work of the hospital filled Ingram's hands for some time, and won for him a great deal of friendly recognition. In the meantime, a building of another kind went on to completion; a sure sign that the old days of Billman were drawing to a close, and that civilization was gathering the wild little town into its arms. For one day a thin, small man came to Ingram, a being so withered and lean that he seemed like a special product of the desert environment, equipped by nature to live for a long time without moisture of any kind. His skinny neck projected from a collar that would have girt in comfort the throat of a giant. His footwear was not neat.

And when he fixed his melancholy eyes upon the minister, the latter was sure that this was another one of the race of hobos who pestered him from time to time.

Said the little man: "I'm Sheriff Ted Connors. I came over to fix up a jail in this town, because it looks to me like this would be a handy place for a jail to stand. It wouldn't never have to be empty. And I'd like to know from you, how you get the folks in this town to fork over the money for a good cause?"

The two spent a long hour going over ways and means. And the very next day the foundations of the jail were established by the running of a shallow trench through the surface sands. The jail was completed in a very few days. And the withered little sheriff jogged out of town, leaving his work to be carried on by a younger, bigger, and much more formidable-looking deputy, Dick Binney.

"Now that there's a church and a jail," said big Vasa, "it looks like Billman was pretty well collared, eh?"

Ingram agreed. It was, he felt, only a matter of waiting a few weeks for the lawlessness and roughness of the town to subside. He had had a taste of that lawlessness before the town was very old. For, one night—the hospital had been opened that day and the first patients, the wrecked victims of a mine explosion, installed—masked men entered Ingram's shack and bade him come with them.

They led him down the main street, which was singularly deserted, and out from the town to a point where a crowd was gathered under one of the few trees of the neighborhood. Beneath that tree stood a man whose hands were tied behind him; around his neck was the noose of a rope which had been flung over a limb above his head. Ingram realized that he was in the presence of a crew of vigilantes.

A gruff voice said to him: "Here's Chuck Lane, that wants to talk to you, kid, before he swings. Hop to it and finish the job pronto. We're sleepy!"

"Do you intend to hang this man," asked Ingram, "without the process of law?"

"Ah!" said the leader of the crowd, "is that your line? Now look here, kid, if there's gunna be any arguin' about that out of you, you can turn around and go home. Chuck swiped a horse, the skunk, and he's gunna swing for it. There's been too much borrowin' of horses around these parts lately. And he goes up as example number one. If you got any talkin' to do, do it on Chuck, will you?"

Ingram considered briefly. After all, he was quite helpless before these armed fellows. A protest would accomplish no good; it would merely deprive the victim of whatever spiritual comfort he might desire.

As he stepped up to the man who wore the noose, the others, with an unexpected sense of decency, made a wider circle around them.

"It's all right, boys," said Chuck Lane cheerfully, noticing this backward movement. "All I got to say can be heard by you gents."

"Chuck," said the minister, "are you guilty of the crime of which they accuse you?"

"Crime?" echoed Chuck. "If borrowin' a horse when a man's in a hurry is a crime—sure, I'm guilty! Well, kid, that ain't why they sent for you. Fact is, I want to know something from you."

"Very well," said Ingram, "if you are a member of any church—"

"I was took to church once when I was a kid," said the thief. "Otherwise I ain't been bothered about them. But now when I come to stand here, around the corner from Nowhere, it seems to me a pretty good time to find out what's on the other side. What do you say, Ingram?"

"Do you mean that you have doubts?" asked Ingram.

"Sure! Doubts about everything. Is this the finish—like going to sleep and never waking up? You're a smart young feller. No matter what lingo you're paid to sling in the church, you give me the low-down out here, man to man. I won't tell nobody what you've said."

"There is a life to come, surely," said Ingram.

"Will you gimme a proof, then?"

"Yes. The beasts have flesh and sense. Man has something more. He is born with flesh, mind, and spirit. Mind and flesh die, but the spirit is imperishable."

"You say it pretty slick and sure," remarked Chuck Lane. "You really mean that?"

"Yes."

"Well, then, the next thing is: What chance have I to slip through without—without—"

"What chance have you of happiness?" asked the minister gently. "That I cannot tell. You know your own mind and life."

"What difference does the life make, really?" asked the horse thief. "Ain't it what's in the head that counts most?"

"Yes," said Ingram, "sin is more in the mind than in the body. Have you anything on your conscience?"

"Me? Well, not much. I've taken my fun where I've found it, as somebody has said before me. I knifed a gent in Chihuahua, once. But that was a fair fight. He'd taken a pass at me with a chair. I shot a fellow up in Butte, too. But the hound had told everybody that he was going to get me. So that don't count, either. Otherwise, there ain't been nothing important. This little job about the horse—that's nothing. I was just in a hurry. Now, kid, the cards are on the table. Where do I go?"

"You are young," said Ingram. "You're not much more than thirty—"

"I'm twenty-two."

The minister stared, aghast. Much, much of life had been scored on the face of this young man in his few short years.

Chuck seemed to understand, for he went on: "But the wrinkles don't set till you're forty," he remarked, "and you can change your face up to that time. Y'understand?"

"Did you intend to take up some other way of—"

"I was always aiming to be a farmer, if I could get a stake together. Nothin' wrong with my intentions, but the money was lackin'."

"And how did you try to earn it?"

"Cards was my chief line."

"Gambling?"

"Yes."

"You were honest, Chuck?"

"I never had the fingers for real crookedness," admitted Chuck frankly. "I could palm a couple of cards. That was all. And I generally met up with somebody a good deal slicker than I was. So my winnings went out the window."

Ingram was silent.

"Does that make it bad for me?" asked Chuck ingenuously.

It was a grim moment in which to play the judge, but Ingram answered slowly: "You've been a man-killer, a thief, and a crooked gambler. And perhaps there have been other things."

"Well," said Chuck, "I suppose that closes the door on me?"

"I don't know," said Ingram. "It depends, in the first place, upon your repentance."

"Repentance?" echoed the other. "Well, I dunno that I feel bad about the way I've lived. I've never shot a man in the back, and I've never cheated a drunk or a fool at the cards. I tried to trim the sharks, and the sharks always trimmed me."

"Is that all?" said Ingram.

"That's about all. Except that I'd sure like to get with the right crowd of boys on the other side. I never had no real use for the tinhorns, thugs, and short sports that must be crowded into hell, Ingram. But you think I got a mighty slim chance, eh?"

Wistfulness and manly courage struggled in his voice.

"No man can judge you," said the young minister. "If you believe in the goodness of God, and fix your mind on that belief, you may be saved, Chuck. I shall pray for you."

"Do it, old-timer," said Chuck. "A prayer or two wouldn't do me any harm, and it might do me a lot of good. And—look here—hey, boys!"

"Well?" asked some one, coming closer.

"I'd like Ingram to have my guns. It's all that I've got to leave the world."

"Are there no messages that I can take for you?" asked Ingram.

"I don't want to think about the folks that I leave behind me," said the thief. "I got a girl down in—well, let it go. It's better for her never to hear than it is for her to start grievin' about me. Better to think that I run off and forgot to come back to her. So long, Ingram!"

"Gentlemen," said Ingram, turning on the crowd, "I protest against this unwarranted—"

"Rustle the kid out of the way," said someone, and half a dozen strong pairs of hands hurried Chuck suddenly away.

Behind him Ingram heard a groan, as of strong friction, and, glancing back, saw something swinging pendulous beneath the tree, and writhing against the golden surface of the rising moon.

THE death of Chuck Lane caused a good deal of excitement in the town, for he was no common or ordinary thief, and the minister overheard one most serious conversation the next day.

He had stopped at Vasa's house to talk over the choir work with pretty Astrid; for she led the choir for him, and a thorough good job she made of it. There he met Red Moffet, and Red, with an ugly glance, rose and strode away, barely grunting at the minister as he passed.

"I think Red doesn't like me very well," said Ingram. "He seems to have something against me. Do you guess what it is?"

"I can't guess," said Astrid, with the strangest of smiles. "I haven't the least idea!"

But now the gallant form of the deputy sheriff, Dick Binney, swept down the street, and Red Moffet hailed him suddenly and strongly from the sidewalk.

"Binney! Hey, Binney!"

The deputy sheriff reined in his horse. The dust cloud he had raised blew down the street, and left him with the shimmering heat of the sun drenching him. So terrible was the brightness of that light, and so great the radiation of heat from every surface, that sometimes it seemed to the young minister that he lived in a ghost world here on the edge of the desert. All was unreal, surrounded by airy lines of imagination, or radiating heat.

Unreal now were those two men, and the horse which one of them bestrode. But very real was the voice of Red Moffet, calling: "Binney, were you there last night?"

"Was I where?"

"You know where."

"I dunno what you mean."

"Was you one of them that hung up poor Chuck Lane?"

"Me? The sheriff of this here place? What you take me for, anyway? Are you crazy?"

"I dunno what I take you for. But I've heard a yarn that you was with the rest of them cowards and sneaks that killed poor Chuck."

Dick Binney dismounted suddenly from his horse.

"I dunno how to take this here," said he. "I dunno whether it's aimed at the boys who hanged Chuck last night, or at me!"

"I say," declared Moffet, "that Chuck was an honester man than any of them that strung him up. And if you was one of them, that goes for you, too!"

It seemed that the deputy was willing enough to take offense, but he paused and gritted his teeth, between passion and caution. Certainly it would not do for him to avow that he had been one of the masked men.

So he said: "What you say don't bother me, Red. But if you're out and lookin' for trouble, I'm your man, all right!"

"Bah!" sneered Red Moffet. "It wouldn't please you none to make trouble for any man in town, now that you got the law behind you! You can do your killings with a posse now."

"Can I?" replied Binney, equally furious. "I would never need a posse to account for you, young feller!"

"Is that a promise, Binney?" asked Moffet. "Are you askin' me to have a meetin' with you one day?"

"Whenever you like," said the deputy. "But now I'm busy. I ain't gunna stand here and waste time with a professional gun fighter like you, Moffet. Only, I give you a warning. You got to watch yourself around this part of the world from now on. I'm watchin' you. I'm gunna give you just enough rope to hang yourself."

He jumped back into the saddle, and galloped down the street, leaving Red Moffet shaking a fist after him and cursing volubly.

Mr. Vasa, coming home, paused to listen with a judicious air to the linguistic display of Red. Then he came into his yard, shaking his head gravely.

"I'll tell you what it is," said Vasa, greeting his daughter and the minister, "things ain't what they used to be around these parts. There's a terrible fallin' off of manhood all around! There's a terrible fallin' off! There's been enough language used up by Red and Dick Binney, yonder, to have got a whole town shot up in the palmy days that I could tell you about."

"Dad!" cried his daughter.

"Look here," said the ex-blacksmith, "don't you make a profession of being shocked every time I open my mouth. You live and learn, honey! I tell you, there was never no fireworks in the way of words shot off before the boys reached for their guns in the old days, Ingram. No, sir! I remember when I was standing in the old Parker saloon. That was a cool place. Always wet down the floor every hour and sprinkled fresh, wet sawdust around. Made a drink taste a lot better. It was like spring inside that place, no matter how much summer there might be in the street. Well, young Mitchell was in there, drinking. Same fellow that shot Pete Brewer in the back. He was drinkin' and yarnin' about a freighting job that he'd come in from. He ordered up a round."

"I'll buy one for the boys," says he.

"No, you won't," says a voice.

"We looked across, and there was Tim Lafferty that had just come through the swingin' doors.

"Why won't I?" asks Mitchell.

"You ain't got time!" says Tim.

"They went for their guns right then, and as I stepped back out of line two bullets crossed in front of my face. Neither of 'em missed. But it was Mitchell that died. Well, that was about as much conversation as they needed in the old days before they had a fight. But now, look at the way that those two have been wastin' language in the street; and nothing done about it. I say, it's disgusting!"

"Do you think that Red's a coward?" asked the girl sharply.

"Red? Naw! He ain't a coward. And he can shoot. But what's important is that the fashion has changed now. A gent with a gun that he wants to use feels that he's got to write a book about his intentions before he can bum any powder. They didn't waste themselves on introductions in the old days. Well, those times will never come back."

The minister asked gravely: "Is it possible that the deputy sheriff could have been at the lynching the other night?"

"Well, and why not?"

"Why not? The representative of the law—"

"Why, old Connors made a terrible mistake when he up and appointed Dick for the job. Dick is all right some ways. But he's got an idea that the law is to be more useful to him than to the rest of the folks. He hated Chuck. I got an idea that he was at the hanging. And that's why Red is mad. He loved Chuck. Good boy, that Chuck Lane."

"Did you know him?" asked the minister, with some eagerness.

"Did I know myself? Sure, I knew him!"

"He was a gambler and—a horse thief?"

"That was careless—swiping the horse. Matter of fact, though, if he'd got to the other end of the line, he would have sent back the coin to pay for the horse as soon as he got enough money together. But you got to judge people according to their own lights, and not according to yours, young man!"

Thus spoke Mr. Vasa, with the large assurance of one who has lived in this world and knows a good deal about it.

"It's a brutal thing to lynch any man, no matter how guilty," declared Ingram.

"Hey, hold on!" cried the blacksmith. "Matter of fact, there ain't enough organized law around here to shake a stick at. Not half enough! And I don't blame the boys that hung up Chuck. Can't let horse stealing go on!"

This double sympathy on the part of Mr. Vasa amazed and silenced Ingram.

"You're lookin' thin," went on Vasa. "Tell, me how you're likin' the town. You run along into the house, Astie, will you? I got to talk to Ingram."

Astrid rose, smiled at her guest, and went slowly toward the house.

"She's got a sweet smile, ain't she?" was the rather abrupt beginning of the blacksmith's speech.

"She has," said Ingram thoughtfully. "Yes," he added, as though turning the matter in his mind and agreeing thoroughly, "yes, she has a lovely smile. She—she's a fine girl, I think."

"Pretty little kid," declared the father, yawning. "But she ain't so fine. No, not so fine as you'd think. Wouldn't do a lick of housework. I don't think, if her life depended on it. Y'understand?"

"Ah?" said Ingram, vaguely offended by this familiarity.

"And she's fond of everything that money can be spent on. Look at that pony of hers. Took her down to look over a whole herd at the McCormick sale. Nothin' would do for her. 'I'll take that little brown horse, dad,' says she.

"Now, Astie," says I, "don't you be a little fool. That little brown horse is a racer, out of blood more ancienter than the dog-gone kings of England. For a fact!"

"'All right,' says she, and turns her shoulder.

"'Look yonder at that fine chestnut," says I. "There's a fine, gentle, upstanding horse. Halfbred. Strong, not a flaw in it anywhere. Warranted good disposition. Mouth like silk. Footwork on the mountains like a mule. Go like a camel without water. Now, Astie, how would you like it for me to give you that fine horse—and ain't he a beauty, too?"

"'I don't want it,' says she. 'It'll do for that crosseyed Mame Lucas, maybe!'"

"'Astie,' says I, 'what would you do with a horse that would buck you over its head the minute that you got into the saddle?'

"'Climb into the saddle again,' says she.

"'Bah!" says I.

"'Bah yourself.' says she.

"It made me mad, and I bought that dog-gone brown horse. Guess for what? Eleven hundred iron men! Yes, sir!"

"'Now, you ride him home!' says I, hoping that he'd break her neck.

"He done his best, but she's made of India rubber. Threw her five times on the way, and had half the town chasing the horse for her. But she rode him all the way home, and then went to bed for three days. But now he eats out of her hand. Wouldn't think that she had that much spunk, would you?"

"No," agreed the minister, amazed. "I would not!"

"Nobody would," said the blacksmith, "to look at the sappy light in her eyes a good deal of the time. But I'm tellin' you true. Expensive! That's what that kid is. If there was ten pairs of shoes in a store window, she'd pick out the most high-priced pair blindfold. She's got an instinct for it, I tell you!"

Ingram smiled.

"You think that she'd change, maybe," said the blacksmith. "But she won't. It's bred in the bone. God knows where she got it, though. Her ma was never an expensive woman."

He rolled a cigarette with a single twist of his powerful fingers, and scratched a match on the thigh of his trousers. A hundred more or less faint lines showed where other matches had been lighted on the same cloth.

"This ain't a blind trail that I been followin'," he announced. "I'm leadin' up to something. D'you guess what?"

"No," said Ingram. "I really don't guess what you may have in mind."

"I thought you wouldn't," said Vasa. "Some of you smart fellows couldn't cut for sign with a five-year-old half-wit. Matter of fact, what I want to know is: Where are you heading with sis?"

"Heading with her?" said Ingram, very blank.

"Where d'you drift? What's your name with her? Does she call you deary, yet?"

Mr. Ingram stared.

"Has she held your hand yet for you?" asked Vasa.

The blood of a line of ancient ancestors curdled in the veins of Mr. Ingram.

"She does all of those things to the boys," said the blacksmith. "There is even two or three that may have kissed her. I dunno. But not many. She gets a little soft and soapy. But she's all right; I'd trust Astie in the crowd. I wondered where you'd been sizin' up with her?"

"I don't know what you mean," declared the minister.

"Aw, come on!" grinned the other, very amiably.

"Everybody has to love Astie. Some love her a little. Some love her a lot. Even the girls can't hate her. How d'you stand? Love her a little? Love her a lot?"

Ingram began to turn pink. Partly with embarrassment, and partly with anger.

"I have for Astrid," he said with deliberation, "a brotherly regard—"

"Hell!" said Vasa.

The word exploded from his thick lips. "What kind of drivel is this?" he demanded. At this, Ingram narrowed his eyes a little and sat a bit forward. More than one football stalwart who had seen that expression in the eyes of Ingram had winced in the old days. But the blacksmith endured this gaze with the calm of one who carries a gun and knows how to use it. Who carries two hundred and thirty pounds of muscle, also—and knows how to use it!

"Don't give me the chilly eye like that, kid," he continued. "I aim to find out where you stand with Astie. Will you talk?"

"Your daughter," said the minister, "is a very pleasant girl, and I presume that that closes this part of the conversation?"

He stood up. The blacksmith rose also.

"Well," said Vasa, glowering, "suppose we shake hands and part friends on it?"

"Certainly," said Ingram.

A vast, rather grimy paw closed over his hand, and suddenly he felt a pressure like the force of a powerful clamp, grinding the metacarpal bones together. But pulling a good oar on a powerful eight does not leave one with the grip of a child. The leaner, bonier fingers of Ingram curled into the plump grip of Vasa, secured a purchase, and began to gather strength.

Suddenly Vasa cursed and tore his hand away.

"Sit down again," he said suddenly, looking at his splotchy hand. "Sit down again. I didn't think you was as much of a man as this! It's what comes of layin' off work. I'm soft!"

The minister, breathing rather hard, sat down as invited. He waited, silently.

"You see, Ingram," said the blacksmith, "I've watched sis with the other boys, and I've watched her with you. She's always been getting a bit dizzy about some boy or other. But with you it's a little different; I guess she's hard hit. Now, that's the way I see it for her. How do I see it for you? And mind you, she'd take my head off if she thought that I was talking out of school."

Mr. Ingram looked at the wide blue sky—the sun dazzled him. He looked at the ground—it was withering in the heat. He looked at the fat face of the blacksmith, and two keen eyes sparkled back at him.

"I didn't think—" he began.

"Try again," said Vasa with a chuckle.

The blue eyes and the smile of Astrid flashed into the mind of the minister. Her smile was just a little crooked, leaving one cheek smooth, while a dimple came covertly in the other.

"I don't know," said Ingram; "as a matter of fact—"

"Only holding her hand?" said the blacksmith with a smile. "Well, Ingram, I ain't throwin' her at your head. I'm just telling you to watch yourself. It don't take more'n five minutes for a girl like that to make a strong man pretty dizzy. And if she ever gets the right chance to work on you, I know Astie! She'll hit you with everything she's got, from a smile to a tear. She'll either have you on your knees worshipping or else she'll have you comfortin' her. God knows what she would need comfort about! But that's the way she works. You understand? And one thing more—Red Moffet is wild about her. Red is the closest to a real man that's ever wanted to marry her. And he's got everything that her husband ought to have—money, grit, and sense. You've got sense. I guess you've got grit. But I know you ain't got money. Mind you, I'm just talkin' on the side. But, whichever way you're goin' to jump, you better make up your mind pretty quick. Because Red, if he don't hear something definite, is gunna lay for you with a gun one of these days!"

With this remark, Mr. Vasa arose.

"Girls are hell to raise," said he, confidentially. "Hell to have 'em and hell to lose 'em. Come on in, Ingram!"

"I'm busy at the church," said Ingram, rather stunned.

"Has this here yarning cut you up some?"

"No, certainly not. I thank you for being so frank. I didn't, as a matter of fact—"

"Maybe I shouldn't have told you. Well, it's out, now, and it'll bring matters to a head. Whichever way you jump, good luck to you!"

They shook hands again, more gingerly. And Ingram turned out the gate and went up the street, his head low, and many thoughts spinning in his mind, like the shadows of a wheel. It was, of course, ridiculous that an Ingram should think of marrying a silly little Western girl.

And still, she was not so silly. File off a few rough corners of speech—she would learn as quickly as a horse runs—and—

He came to the church and stood before it, hardly seeing its familiar outlines. He had received counsel. But, oddly enough, what he wanted to do now was to go back and see Astrid and find out, first of all, if she really cared for him.

Suppose that she did; and that he was not ready to tell her that he loved her? He made a sudden gesture, as though to put the whole idea away from his mind, and with resolute face and firm step, he went into the church.

A LITTLE chill went through Billman next day, for it was known that Red Moffet had discovered the name of at least one member of the posse that had hung Chuck Lane. Mr. Ingram heard the story from Astrid when she stayed a few moments after choir practice. It was a large choir, and though it was impossible to obtain enough male voices to match the sopranos, it was pleasant to hear the hymns shrilling sweetly from the throats of the girls.

Astrid stayed after practice and told the exciting tale. Mr. Red Moffet, by some bit of legerdemain, had secured the very rope with which Chuck Lane was hanged by the neck until dead. And, having secured that rope, Mr. Moffet had examined it with care and promptly recognized it. For, at the end, there was a queer little knot such as only a sailor would be likely to tie. And in Billman there was a cowpuncher and teamster who had been a sailor before the mast—one Ben Holman, a fellow of unsavory appearance. And worse reputation.

Red Moffet had, first of all, searched wildly through Billman to find the owner of that rope. But it was said that Mr. Holman heard that he was wanted and decided to look the other way. He slipped out from the village into the trackless desert. Mr. Moffet started in pursuit in the indicated direction, but straightway the desert became truly trackless, for a brisk wind rose, whipped the sands level, and effaced all signs.

Red Moffet came back to Billman, and the first place he went to was out to the cemetery, carrying the hangman's rope with him. He visited the most newly made grave and sat for a long time beside it. He himself had paid for the digging of that grave and for the headstone, which stood at one end of it, engraved in roughly chiseled letters:

Here lies Chuck Lane.

He was a good fellow

that never played in luck!

Men said that the inscription was Red's contribution also.

Whatever were the thoughts that passed through Moffet's mind as he sat there alone in the graveyard, Billman did not have the slightest hesitation in describing them as fluently as though Red had confided his ideas to the world in general.

"If you know what he was thinking, tell me," suggested the young minister to Astrid.

"Oh, of course. Red was swearing that he would never give up the trail until he had Ben Holman's scalp."

"Does he intend to murder that man for being one of the mob?" asked the minister.

"Murder?" echoed Astrid. "Well, it isn't murder when you stick by a pal, is it?"

"This pal, as you call him, is already dead. And though the means used were illegal, I must say that it seems to me young Lane was not worthy of much better treatment than he received."

At this, Astrid, who was sitting lightly on the back of a chair, swinging one leg to and fro, frowned.

"I don't follow that," said she, "You've got to stick by things, I suppose. Death doesn't matter, really."

"But Astrid—"

"I wonder," broke in this irreverent girl, "what folks would say if they heard me call you Reginald, or Reggie, say!"

"Why do you laugh, Astrid?"

"Why, Reggie is really a sort of a flossy name, isn't it?"

"It never occurred to me," said that serious young man. "But to return to what you say—about death not mattering—"

"Between a man and his pal, I mean," said Astrid. "Why, you live after death, don't you?"

"Yes," said Ingram. "Of course."

"Then," said she triumphantly, "you see the point. Even after a pal is dead, you'd want to do for him just what you'd do if he were living. That's pretty simple, it seems to me!"

"My dear child!" exclaimed he. "What service is Red performing to Chuck Lane by chasing Ben Holman out of Billman and murdering him if he can?"

"Why, Reggie," said the girl, "how would you serve a friend, anyway? Suppose you're a friend of mine and you want music for your church. Well, I'd sing in your church, wouldn't I?" And she wrinkled her nose a little and smiled at him. "Or suppose that I was a friend and that you wanted a new wing built on the church, I'd build it for you if I could, wouldn't I? Same in everything. You served a friend by doing what he would do for himself if he could, but which he can't—"

"I don't exactly see how you relate this to Red's murderous pursuit of Holman."

"You don't? You're queer about some things, Reggie. Suppose that Chuck Lane could come back to earth, what would he want to do except turn loose and chase down the boys that strung him up? And first of all he'd want to get the fellow who loaned his rope to do the job. I think that's pretty clear!"

"Astrid, Astrid," said Ingram, "do you excuse a murder with a murder?"

"But it isn't murder, Reggie! Don't be silly! It's just revenge!"

"'Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord!'"

"Oh!" said she. "Well, wait till the time comes, and I'll see how long you'd sit still and let a partner be downed by thugs or yeggs or something! You'd fight pretty quick, I guess!"

"No," said he. "Lift a hand against the life of a fellow? Astrid, we expressly are commanded to turn the other cheek!"

"Sure," said Astrid. "That's all right. But you can't let people walk over you, you know. Isn't good for 'em. Would make 'em bullies. You got to trip 'em up for their own sakes, don't you?"

"My dear Astrid, you are quite a little sophist!"

"And what does that mean?"

"A sophist is one who has a clever tongue and can make the worse way appear the better, or the better appear the worse."

She grew excited.

"Suppose, Reggie, that you were to stand right here—you see? And a gun in your hand—"

"I never carry a gun," said the minister mildly.

"Oh, bother! Just suppose! You're standing right here with a gun in your hand, and your beat friend is standing in the doorway of the church, and you see a greaser come sneaking in behind him with a knife—tell me, Reggie—would you let the greaser stick that knife into his back, or would you shoot the sneak—the low-down, yellow—"

"Such a thing could never happen here in the house of God," said Ingram.

"Oh, but just supposin'! Just supposin'! Can't you even do a little supposin', Reggie? You make me tired, sometimes! I pretty nearly believe that you haven't got any real pals! Tell me!"

"Pals?" He echoed the word very gravely. And then his face grew a bit stem with pain.

"Hold on!" cried Astrid. "I didn't mean to step on your toes like that. I see that you have got 'em, and—"

"No," said he. "There was a time when I had a good many friends. They were very dear to me, Astrid; but when I took up this new work, why, they drifted away from me. So many years—a very close life—books—study—a bit of devotion. No, I'm afraid that I haven't a single friend left to me!"

"That's terrible hard!" said the girl, sighing. "But I'll bet you have, though. Look here, it makes you feel pretty bad, doesn't it, I mean the thought of having lost 'em?"

"I trust that I have no regrets for the small sacrifices which I may have made in a great cause which is worthy of more than I could ever—"

"Stop!" cried Astrid. "Oh, stop, stop! When you get humble like that, I always want to either cry or beat you! I want to beat you just now! I say, you feel terrible bad because you've lost all those old friends. Then you can be sure that they feel bad to have lost you. So they still are your friends, and they would come jumping if you just gave them a chance! Tell me about them, Reggie."

He shook his head.

"It is a little sad," said he, "to think of all the men who've been—well, I think I prefer to let it drop."

"But I want to know. Look! I've told you everything about myself And I don't know a thing about you. That's not fair. But the whole point is, that any real man would go to hell and back for the sake of a friend. Now wouldn't he?"

The minister was silent.

Astrid went on, innocent of having given offense: "I'll tell you how it is, then, with Red. He and Chuck were old pals. Chuck's lynched. Well, Red wouldn't be a man worth dropping over a cliff if he wouldn't try to do something for his old partner. Isn't that clear and straight? I want to make you admit it."

"I can't admit that," said the minister slowly.

"By Jimminy!" said the girl, "I do believe that you've never really had a hundred-per-cent friend—the kind that they raise in this part of the country, I mean. A fellow who would ride five hundred miles for a look at you. Never write you a letter, most likely. But fight for you, die for you, swear by you, love you dead or livin', Reggie. That's the kind of a friend that I mean!"

The minister had bowed his head. He was silent; perhaps the torrent of words from that excited, small, round throat was bringing before his eyes all the men he had ever known.

"What are you seeing?" she asked suddenly.

"I'm seeing everything from the stubble field where the path ran to the swimming pool," said Ingram sadly, "to the empty lot behind the school where we used to have our fights; and the schoolrooms; and the men at college. Boys, I should say. They weren't men. They can't be men until they've learned how to endure pain!"

"Look here!" she snapped, "does a fellow have to suffer in order to be the right sort?"

"Would you trust something that looked like steel," asked he, "unless you knew it had been tempered by going through the fire?"

"Now you're getting a little highflown for me," said the girl. "It isn't only the men that have been your friends. But suppose I were to say that a girl you've known was in danger—the very one that you liked the most—suppose that she were standing there in the doorway, and a sneak of a Mexican was coming up behind—what would you do? Would you shoot?"

"No, I would simply call: 'Astrid, jump!'"

"I—" began Astrid.

Then the full meaning of this speech took her breath away and left her crimson. Ingram himself suddenly realized what he had said, and he stared at her in a sort of horror.

"Good gad!" said the Reverend Reginald Ingram, "what have I said!"

"You've made me all d-d-dizzy!" said Astrid.

"I—as a matter of fact, the words—er—were not thought out, Astrid!"

"Of course you didn't mean—" began Astrid.

"I hope you'll forgive me!" said Ingram.

"For what?" she said.

"For blurting out such a—"

"Such a what?" she persisted.

"You're making it hard for me to apologize."

"But I don't want you to apologize."

"My dear Astrid—"

"I wish you'd stop talking so far down to me!"

"I see you're offended and angry."

"I could be something else, if you'd let me," said she.

"I don't understand," said Ingram miserably. "I could be terribly happy, if you meant what you said."

He looked hopelessly about him. A daring blue jay had lighted on the sill of the open window. Its bright, satanic eyes seemed to be laughing at him.

"You see—Astrid—"

"Don't," cried she and stamped her little foot.

"Don't what?" he asked, more embarrassed than ever.

"Don't look so stunned. I'm not going to propose to you."

"My dear child—the friendship which I feel—which—so beautiful—most extraordinary—fact is that—I don't seem to find words, Astrid."

"Talking is your business," said the girl. "You've got to find words."

"Do I?" asked Ingram, wiping his hot brow.

"You can't leave me floundering like this, unless it's because you have some sort of a doubt about me. I want to know. Tell me, Reggie!"

"What?" asked he, very desperate.

"You make me so angry—I could cry!"

"For Heaven's sake, don't! Not in the church, when—"

"Is that all you think about—your silly old church? Reginald Oliver Ingram!"

"Yes, Astrid!"

"Do I have to tell you that I love you?"

Mr. Ingram, sat down so suddenly and heavily that the chair creaked beneath his weight.

"Stand up!" ordered Astrid.

He stood up.

"You don't really care!" she cried.

"Astrid—I'm a bit upset."

"Are you sick?"

"I'm a bit groggy."

"Reggie, cross your heart and tell me—have you ever been in love?"

"Not to my knowledge."

"Never really been in love?"

"No."

"Are you a little giddy and foolish and—"

"Yes."

"You are in love!" said she.

"Do you think so?"

"Have you never proposed?"

"Never!"

"Never in your whole life—to any girl?"

"No!"

"Then you'd better begin right now."

"Astrid, the thing is impossible!"

"What is?"

"To marry. You understand? I'm a minister. A poor man. Nothing but my salary—"

"Bother the silly salary! Do you want me?"

"Yes."

"Honestly?"

"Yes."

"More'n all the world?"

"Yes."

"More'n all your old friends—almost as much as your church and your work?"

"I think so," said he.

"You'd better sit down," suggested Astrid.

She took the chair beside him, and leaned her shining head against his shoulder.

"Heavens!" said Astrid.

"What's wrong?"

"How terribly happy I am! Why, Reggie, you're all trembling!"

"Because I'm trying to keep from touching you."

"Why try?"

"We sit here in the house of God and in His presence, Astrid."

"He would have to know some time," said she. "Gracious!"

"What, dear?"

"How hard you made me work!"

THE ideas of Astrid about the practical problems of the future were extremely simple and to the point. They could easily live on his salary. How? All she wanted would be some horses for riding, and a few Mexican servants—

"I have just enough," said he, "to support one person on the plainest of fare, with no servant at all."

"Oof!" said Astrid.