RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

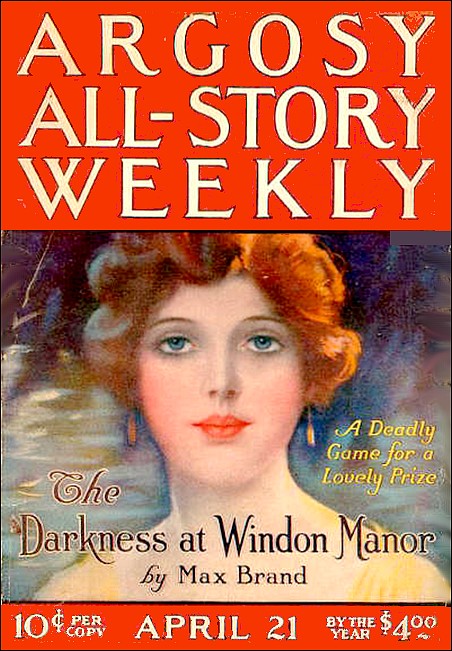

Argosy, 21 April 1923, with "The Darkness At Windon Manor"

THOUGH the chair in which he sat was one of a long and closely filled line, Andrew Creel seemed sufficiently aloof. It was not that the steamer rug wrapped closely about his knees or the cap drawn far over his eyes differed from those of the men near him, not that his lean face and dark eye were forbidding in any degree; but he carried about him that air of self-completeness which does not invite inquiry.

Conversation, after all, generally starts with discomfort of mind or body. When a man is lonely, or too hot, or too cold, or wearied of his surroundings, he turns to a neighbor who seems to suffer mutually; he voices a common protest, and the conversation begins on common grounds. It is not hard to tell when a man is ready for and open to approaches. A slight wandering of the eye, a yawn which never springs from sleepiness, a sullen drooping of the mouth, a nervousness of hand and foot—these are the signs which betray a man who pines for conversation.

But Andrew Creel was one of those who can be heated neither by conversation nor wine, nor by a tropic sun; they cannot be crowded in a throng, and they cannot be made lonely in a desert. They neither criticize nor protest nor praise. They merely watch; and one cannot tell whether their observations are retained in mental notes or consigned to oblivion. All down the line of steamer chairs there were perpetual changes. Some one leaned forward to draw his rug closer or loosen it; some one rearranged his hat; some one leaned back and tried to sleep with a scowl on his forehead, as if defying any one to accuse him of ill success; but Andrew Creel seemed utterly unmoved. His hands never altered their position in his lap; a corner of his rug had worked loose in the wind, and it flapped unheeded; his head turned from time to time, slowly, never jerked about by irritation or curiosity.

Indeed, it seemed as if the quiet eye of Andrew Creel found something new in each one of the vast groundswells which heaved about the side of the ship and went wandering off against the distant sky line with ridges of white and little rushings of foam along its sides. The swagger of the ship on the crest of the wave and its drunken lunge into the hollow of the trough seemed equally soothing to him. When people passed, the eye of Creel followed them calmly down the deck at times, never prying and never omitting the slightest detail.

It did not irritate those he observed, for they knew that he noted, but felt that he made no criticism; it was not much more than the observant eye of an animal. Again, he fairly looked through a whole group and bent his observation past them on the familiar rise and fall of the waves. One could never prophesy his state of mind; he might be on the verge of whistling a tune or closing his eyes in dreamless sleep.

In fact, Creel was very much what he seemed. He had spent a number of years wandering the earth, living well within the limits of a comfortable income. In all places he was at home, and he became the back of a camel in Egypt as well as the saddle on a spirited horse in Central Park. Bohemia accepted him in Paris without a murmur, and respectability opened its doors to him in London. What he gained from his wanderings no one would be prepared to guess, for he had never opened his heart to a confidant. It was really hard to conceive of such a man having a confidant. And though one presumed that under stimulation he might be a most fascinating narrator, it was obvious that nature intended him for a listener rather than a talker.

Life had left him as unmarked within as his forehead was smooth without. He was a man untested, untried. If there was strength in him, it was like the speed of the pedigreed horse which has never trodden a race track. He did not make an appeal vital enough to stimulate wonder and puzzling estimates; perhaps he might have been called the Sphinx without her smile. At the most, people surmised in him cleanness of body, heart and mind; and probably Andrew Creel made no more definite estimate than this of himself. He had no enemies, and yet he did not feel ineffectual; he had no friends, and yet he was never lonely.

On a gray day he mildly enjoyed the dimness; on a bright day he mildly enjoyed the color. He did not object to liquor, and yet he had never been drunk; he found women amusing, but he had never been in love; he enjoyed money, but he never yearned hungrily for silken luxury. To be sure, he was not asleep, but one could not help asking: "What if this man should awaken? What if he should desire, dread, hate, love? What if the black and white of his life should be flushed with sudden color—golden, reds, and purples?"

This very question in much the same words passed through the mind of Creel as he sat in the sunshine of the deck of the steamer. The stimulus to the question was a man who stood half facing him at the rail. This fellow had taken his hat off and the sea breeze was ruffling his hair; his head was bent a little back, and with partially closed eyes and faintly smiling lips he breathed deep of the same wind. Undoubtedly, Andrew Creel had seen a hundred other men in similar postures and had never been stirred to question or to comparison of their mood with his own. The difference this time lay in the similarity which existed between the bareheaded man and himself.

Not that they at all approached the same identity. To be sure, no one could ever mistake them; but they belonged to the same physical type. There was the high, rather narrow forehead, with marked prominences just above the eyebrows, the straight lips, the thin chin, the arched nose, the dark, sallow complexion, the black eyes, the lean, erect body suggesting agility rather than downright strength, endurance rather than sudden bursts of speed.

It was the call of like to like which first drew Creel's sharp attention. He noted one by one with unerring eyes the similarities, and in the second place he enumerated the differences. Here, however, there were difficulties. No matter how he concentrated on the subject, he could not make a list of the distinctions. His strong sense of order revolted against this failure. It was finally borne in upon him that the distinction was mostly a matter of differing spirits.

This man had rubbed shoulders with the world, had trodden the race track of human competition. The parallel lines had been engraved between his eyes by strife, victory, and perhaps defeat. He was capable of sorrow; he was capable of joy. Ah, there was the vital thing!

The salt wind in the face of Creel, which was a mere physical fact, made the stranger straighten his body and close his eyes in exquisite enjoyment. Creel caught the sense of the other covering space; that wind blew him into the past—how far? and into the future—how far? What keen associations pierced with that wind into the center of his being? For the first time in his entire life Creel was conscious of a hollow sense of loss, of desire. He had missed something in life. What was it?

The questions we ask ourselves cannot be evaded. Andrew Creel discovered with infinite discomfort that he could not turn his shoulder on himself as he had turned his shoulder on the world. He made, at last, a silent, sharp resolution to pierce the secret of this other man; to seek him out; to open him like a book and read therein. That resolution was the turning point in his life. He felt like the man who sits half dozing by the fire until a sudden thought comes knocking at his mind and he startles erect with the feeling that some one else has been in the room and watching him. Indeed, considering Creel in the light of what he did thereafter, it might be said that he had never before been awake.

UNACCUSTOMED as Creel was to feel under the positive necessity of meeting any human being, he was in doubt as to how he should approach the stranger. It seemed clumsy to go to him with some direct question in front of the crowd of languid passengers. He stared down, concentrating on the problem, and when he looked up again the stranger was gone.

He noted it with a quickening of the heart. There was no doubt now that he must exchange words with this man. Eventually he sauntered around the deck, but the stranger was nowhere in sight, and Creel carried his disappointment down to dinner with him. His gloom was the greater because this was the last evening on board ship, and the next morning everybody's time would be taken in the bustle of making port: in fact, by sunrise they would be among the approaches to New York. To-night was his last chance to find his man.

After dinner, accordingly, he went directly up to the deck. Once there, it was the wind which led him, for it was strongly connected in his mind with his earliest picture of the other. Creel went straight forward to the point where the wind was sure to be strongest—the bow. He was correct. There, leaning on the railing and apparently watching the bow wave, was his quarry. So sharpened were his eyes for the search that he recognized his man by the shape of his back.

Creel approached slowly, pondering ways of opening the conversation, when the wind which had already helped him assisted him again. It flipped the hat from the head of the other and whisked it straight into the hands of Creel. He laughed; there was exultation in his voice, for he knew that chance was playing into his hand.

"The Lord be praised," said the stranger, "for you've saved the only thing about me that won't be alien in America." He touched the hat into shape, for the crown had been deeply indented, and replaced it on his head.

"You see," he explained, "before I left London I intended to get clothes from an American tailor—a whole outfit—but I dodged the job until the last moment, and then I only had time to get a hat."

"Well," nodded Creel, as he took a position at the rail near the other, "we're certainly exact opposites; the only thing American about you is your hat, and the only thing English about me is the same article. Yet on the whole I prefer English styles throughout."

The other shrugged his shoulders. He said:

"We're on the way toward making comparisons between the English and Americans. Let's avoid it."

"And why?" asked Creel. "To the end of the world we'll remain interested in our differences; I've never known an American who could spend an hour in London without making comparisons between it and New York, and vice versa. There are very good reasons for it."

"Aye," replied the other, "cousins are always curious concerning each other."

"Exactly. We're just enough alike to make us appreciate our differences."

"And just close enough to fail to see each other in perspective."

"To be sure," agreed Creel. "We forget that we speak the same language, and remember that we have differing accents; we habitually underrate each other, and yet, when it comes to a pinch, blood usually tells. Still, the habit is irritating."

"Good again. The Yankee calls the Englishman dull, and the Englishman calls the Yankee cheap."

"But give them both the same environment, and you can't tell them apart, perhaps, in a single generation."

"To be sure; we have the same thieving ancestry," said the stranger.

"Thieving?" echoed Creel.

"Well, why not call it that?" argued his companion. "What other is the ancestry of the Englishman and the American? Not that I mean that we are still thieves, but we gained our strength from a strong infusion of the bloods of predatory races. In the beginning the Celts were in Great Britain. They were harmless enough to the world; they injured no one but themselves. At the same time they accomplished no particular good; they added nothing to the civilization of the world. They're a comparatively new race, and yet they left so few monuments and influences that they're almost prehistoric. They didn't try to take from others, but neither did they give to others. But then came the robber Saxons. They were an element of aggression and strength. They made a mark.

"Next came the robber Danes. Another element of strength. Finally came the robber Normans. Four elements of blood go to the making of the modern Englishman—and American—and three of those elements are from predatory races. They all had the acquisitive impulse, so that they stole at first, and when there was nothing else to steal they began to make for themselves."

He broke off and chuckled to himself, then he added, nodding in self-agreement: "Yes, we call the Englishman's instinct to conquer and rule to-day imperialistic instinct, but I wonder if it isn't a lineal inheritance from the spirit of the Vikings."

"Ah," murmured Creel, "you believe that the thief and the creator are only short steps apart?"

The other started and turned more directly toward Creel. His eyes sharpened.

"In a manner of speaking," he said, "that's exactly what I do mean. Come, come! We begin to agree famously!"

"Well," answered Creel, "it's a new viewpoint, but I suppose a fairly sound one. The impulse of the thief is to have and to hold; so he takes what some one else has already made. But if there's nothing to take he makes it for himself. He raises his own grain, perhaps."

"Or irrigates the desert," added the other.

"Or paints his own picture."

"Quite right. One generation steals a country to which their only title deed is the stronger hand; the next generation celebrates the theft with an epic poem. Superior strength, superior subtlety makes the theft possible; and strength and cleverness are the materials which the poet wants for his singing, his idealization."

"According to this," said Creel, smiling, "the thief is a very important and necessary element in civilization."

"And why not admit it?" answered the other with a touch of sharpness. "Strength is the important thing in men, and thieves are strong. They pit their single power against the banded might of the law. The primitive impulse which the average man reduces to spite, jealousy, backbiting, the thief admits to himself and follows. At least, he is not a hypocrite, and hypocrisy is the damning sin of every other class of society."

"Now we have reduced it to this," summed up Creel: "the thief is strong, clever—and honest." He laughed softly.

"You laugh," nodded the other, "but nevertheless you agree with me!"

And in spite of the growing dimness of the evening Creel saw that his eyes lighted with triumph. He added:

"Paris stole Helen: hence Odysseus and Agamemnon and Achilles; hence Homer. It all began with a theft; and after all, when does a good man make a satisfactory hero? He may be impressive, but he can never be real.

"The hero of Paradise Lost, every one admits, is Satan. Our sympathies lie with Abel; our interests lie with Cain. The destroyer holds the center of the stage. Caesar stole their rights from the populace; and the populace dropped upon their collective knees and thanked him for it. Yes," he concluded, "for a life which gives a man excitement, pleasure, leisure, and a light conscience, give me the profession of the thief."

As he ended, a searchlight from the bridge, whose shaft of light had been wandering wildly across the clouds, now dropped for an instant toward the prow of the ship and fell upon the figure of Creel's companion. His hand flew up automatically, as if to ward a blow. In raising it the two middle fingers were closed, but the forefinger and the little finger remained extended stiffly. It was an odd gesture; even when the searchlight flashed away the oddity of it remained imprinted on the mind of Creel. For no real reason he wished suddenly to be alone; to think over and analyze at leisure the host of impressions which the stranger had given him.

"I have to get my things in shape for the landing," he said, "so I'll bid you a very good evening. And perhaps," he added, "we can meet again in the morning? Perhaps we can find other points for agreement, eh?"

"By all means," chuckled the other, "and suppose we make this the meeting place—any time after breakfast. I'm usually out here watching the gallop of the bow wave and catching the breath of the wind. The wind, my friend—there's the predatory spirit for you!"

It was full night as Creel turned away and walked back up the deck. He remembered, after he had gone a little distance, that he had forgotten to ask the name of his new found friend, and he turned sharply about. He was loath, however, to return for such a purpose; it was too blunt, too crass a question; it showed too much curiosity, and if there was one thing on which Creel prided himself, it was his profound indifference.

As he stood, hesitating, he saw a broad-shouldered, stocky man walk down the deck toward the prow. The eye of Creel followed him, partly because of his powerful proportions, partly because his head was canted in an odd, thoughtful manner to one side, partly because he was walking straight toward the place where the stranger stood at the prow watching the rushing of the bow wave, faintly white, below. But the night was now so thick that the eye of Creel did not reach to the prow itself. Into that gloom the figure of the stocky man with the canted head disappeared. At that Creel turned and went slowly to his cabin.

THE next morning breakfast was hardly done when Andrew Creel went straight to the bow. It was already crowded with passengers who kept their eyes fixed on the approaches to New York Harbor, and among them there was no sign of the interesting stranger of the night before. It irritated Creel but hardly surprised him, for the stranger was distinctly not the man on whom engagements lie heavily; he would follow his mood.

Creel waited patiently, and when his man did not appear he made a careful tour of the decks. He regretted doubly now that he had not learned the name of his singular acquaintance, but finally he resigned himself to his fate. They were already in the heart of the harbor—the jagged outline of the Battery was like a row of lances cutting into the sky.

It was not hard to dismiss the stranger, no matter how promising their talk had been, for it seemed to Andrew Creel that he had already caught at the secret. The feeling that he had slept all his life was stronger than ever in him; it made the consciousness of his present alertness all the more keen. He fell to watching the faces of men and women and children who passed him. To be sure, this had always been a favorite amusement of his, but there was now a difference.

Whereas he had formerly merely caught at the characteristics and type of a man, he now tried to go back into his past, and from that he tried to build the man's future. It seemed to Creel in the delight of his new attitude that every line in a man's face was as significant as a chapter in a biography. Aye, every man was an open book, though each was written in a differing language; but everything helped Creel—the shape and activity of hands, the set of a chin, the brightness of an eye, the carriage of head and shoulders.

Not men alone, but the very feel of sun and air was new to Creel, and the distant heights of the Battery were like a jumble of imperial towers over a fairy city; when he stepped ashore he would be in the land of adventure. It was strange that a glance at a man and five minutes conversation should have affected him so vitally, but perhaps Creel had merely reached the natural end of his period of inertness.

After all, most men reach some such awakening. To some it comes through the sudden love for a woman, disappointed or fulfilled. A lesser thing affected it with Creel; he was as changed from himself of yesterday as the adolescent is removed from the mature man. It was not strange, therefore, that he was whistling as he moved down the gangplank, and when at last he was free to pass on into the city he walked with a springing, eager step like an athlete from whose shoulders a weight had been removed.

It was as he passed in the steady stream of people out onto the street that a form of great height loomed suddenly at his elbow, and a voice boomed:

"Hel-lo!"

He whirled, shaken with surprise, and his hand automatically flew up as if in self-defense; but when it rose the middle fingers were clenched and the fore and little fingers stiffly extended in the manner of the stranger on the ship the night before. He dropped his hand at once and found himself looking up into the face of a burly monster a whole head taller than himself; a man with a comfortably rounded vest and a plump face, tinged with the pink of good living. His eyebrows were so highly arched and his eyes so wide and extraordinarily blue that his expression was one of the most extreme candor and naïveté.

Before the gesture of Creel he started, and the color in his face deepened; his eyes darted once to right and left, and brushing close to Creel he muttered:

"Good God, Ormonde, do you give that sign in public places?"

The blood leaped from the heart of Creel to his head and then back again. He stared straight before him; the sun had never been so bright—faces were a swirl of dazzling white in that radiance. For the dream of the morning was true: he had stepped into a land of adventure—a fairyland. Ormonde? Well, he would be Ormonde or any one else for the nonce. The words came of themselves; his volition had nothing to do with them. He said:

"My dear fellow, it's become a second nature to me, and there's really no danger in it."

And to prove it he brazenly raised his hand in the same manner with the two fingers stiffly extended. The big man cursed softly; he was so excited that his forehead gleamed with sweat.

"Damnation, Ormonde!" he muttered. "Are you going to turn out as bad as everything we've heard about you? Follow me—this way!"

He led the way to an automobile, a long-bodied roadster, and they began to wind away through the heavy traffic with horns blaring about them and the rumble of trucks over the cobblestones.

"You took me on trust from the signal?" cried the giant in a voice that boomed easily over the rush of traffic.

"Not altogether," smiled Creel.

"Ah, I suppose that Anne said a word about me?"

"More than a word, in fact," replied Creel. "Quite a lengthy description."

"H-m!" rumbled the other, and his pink face turned red with pleasure. "A damned good girl—Anne! Did she call me Uncle Larry or just plain Payson?"

There was a note of concern in his question.

"Uncle Larry," replied Andrew Creel.

"Good!" nodded Payson. "She and I are as thick as—ha! I always choke over that word, Ormonde, damn it!"

"Naturally," said Creel.

"Eh? Naturally."

The big man swung about in his seat to stare at his companion in such amazement that he avoided a passing street car by the least portion of an inch. But Creel leaned back against the cushions perfectly at ease. He had never been more pleasantly stirred in his life, and he was inwardly sworn to see this adventure through.

"Tut, tut!" he protested. "Are you about to quarrel over a word?" And then he made his first wild venture toward the truth.

"Can't I step out of the profession for a single instant?"

"To be sure! To be sure!" agreed the other. "You are talking unofficially, so to speak. That's a good one!" He laughed thunderously. "But I'm not going to quarrel about the word. No, Ormonde, I'm a little too conservative to quarrel with you."

He laughed again, but this time without much mirth. "You see, we have heard a little of your history."

"I hope," murmured Creel, "that you enjoyed it."

"Enjoyed?" echoed Uncle Larry Payson. "By the Lord, Ormonde, I tell you my hair stood on end during part of it, particularly that whole Marborough episode. D'you know that when I heard how they both arrived at the same time I gave you up—I buried you!"

"Really?"

"You think I should have had more confidence in you than that? Well, sir, I have! After that yarn was done I was prepared to believe you could go through solids like an X-ray, and now that you have the Bigbee case—well, sir, when we get home I'll tell you at length what I think of you and what all the rest of the boys think of you. We are agreed on that. In fact, Ormonde, your fame has spread abroad through America among others than us. Yes, sir, you'll be delighted with a tribute that was paid you the other day. I was dining with the new police commissioner."

"With the police commissioner!" echoed Creel rather more than politely surprised.

Payson smiled with fatherly benevolence.

"We are thick—the best of friends," he went on. "I am one of the advisory cabinet, so to speak, and confer with the chief on his most difficult cases. He considers me a rare amateur in crime."

"An amateur?" repeated Creel, and then laughed softly. His mirth was mightily re-enforced by Payson.

"Yes, sir, those are the words of old Tom York, God bless him! An amateur in crime! If he knew the truth he would not believe what his eyes and ears told him. But I was about to tell you of the compliment he paid you. We had a good deal of wine with dinner, and Tom grew rather warm. He began to talk about big cases he knew of—in fact, he gave me some invaluable information that I'll tell you about later. In the midst of things he began to talk about the greatest criminals the law has combatted. And finally he said:

"'There's a young fellow in England the world will hear of one of these days. I've heard of some of his exploits, but not all of them. In fact, I've reason to believe that no one dreams of half the things he has done. His name, I understand, is Edward Ormonde, and in my personal opinion, Mr. Payson, he is the greatest thief that ever lived.' How's that, Ormonde?"

Creel flushed and was silent.

"You aren't offended?" inquired Payson eagerly.

"The word won't do!" said Creel decisively. "Won't do at all, in fact. Thief? Pah!"

"To be sure," cried Payson hastily. "I don't mean to circumscribe your talents to the one branch. By no means! And for that matter neither did Tom York, I'm sure!"

"Let it go," said Creel, relenting. "But it always irritates me a little to hear a fine—er—art, degraded with the name of thievery!"

Payson coughed and swallowed his smile, but by a mighty effort he presented a fairly straight face to Creel, though the cost was swelling purple veins above his forehead.

"If Edward Ormonde calls it an art," he said, "why, an art it is!"

THE long roadster by this time was humming softly on its way across the Fifty-Ninth Street bridge. In a few minutes it had cleared the suburbs of Brooklyn and was rushing along a country road. Since the remark about theft being an art Payson had few comments to make. Presently, however, he pointed to the left.

They had just topped a hill and they looked down upon a promontory. It was a triangle, the point touching the mainland, while the ocean surrounded it almost completely from the three sides. Down to the sea it dropped in sheer cliffs and at the bottom of these Creel saw the white lines of the surf and caught the far-off murmur of its rolling. The top of the promontory rose smoothly up toward the center, a fine lawn covering the outer portions and the mansion rising in the center, surrounded with mighty trees.

"Anne sent you a picture of it, didn't she?" went on Payson, as though irritated by the persistent silence of Creel. "Recognize it?"

"It shows even finer than it did in the picture," answered Creel. "In fact, I've rarely seen a finer place!"

"H-m!" nodded Payson. "That's what I say—though it's throwing a bouquet at myself—for I chose the site myself, you know, and I supervised the fitting up of the house. All that left wing is my work, besides the stables and the garage. We call the place Windon Manor."

"The whole group of buildings hangs well together," agreed Creel. "You did a good job of that. I suppose it's much admired."

They were sweeping down the graveled road from the crest of the hill toward the gate in the stone wall which crossed the neck of the promontory.

"The trouble is," answered Payson regretfully, "that men in our profession are usually too busy with other things to pay much attention to architecture. I can't tell you how glad I am to see that you're not like the general run. Naturally, men outside the profession never enter the grounds."

"Naturally," echoed Creel noncommittally, "you couldn't let men of another sort enter."

"I should say not," sighed Payson. "We'd venture daylight murder to keep others out."

Coming down the sweep of the hillside the car had gathered terrific momentum.

"Really?" murmured Creel. "And what would you do if a man not in your—or our—profession, got into the house or even the grounds? Would you actually go so far as murder?"

"Murder?" cried Payson. "Good Heavens, Ormonde, don't you see that it would be absolute ruin for an outsider to come in with us—even at a distance? We couldn't take a chance. There are things in that house that might—but let's not talk of the danger of an outsider getting in! It sets my blood running cold, the very thought! Murder? Why, Ormonde, we'd have to kill the unfortunate beggar and burn his body to ashes in the furnace. We'd have to annihilate him and every trace of him!"

Here the car, striking a slight rise of ground just before the gate, seemed to rise from the road and leap like a winged thing through the gate. Andrew Creel settled back against the cushions, his eyes half closed.

"But," said Payson, easing up the speed of the machine as they approached the house, "we give every one who comes here the acid test and you may be sure we know their history backward before they are trusted."

"And yet," said Creel, driven by the imp of the perverse, "just how much do you know about me?"

"Of course not much," chuckled Payson, "but then you would be an exception in any society—absolutely!"

"I wonder!" murmured Creel, and glancing back over his shoulder he noted the gate far behind him. He felt as if he had crossed the Rubicon, indeed.

They ran the car into a roomy garage, and a mechanician in a greasy cap approached them as they walked back toward the door.

"This chap is our chauffeur and chief mechanic," advised Payson, "and he's as true as steel all the way through. He's never failed us in a pinch. Better stop and have a word with him. He knows you were coming and he'd be mighty happy to have you notice him." And as the chauffeur came up, "Bud, I've been telling our friend about you. This is Ormonde."

Flannery wiped his grimy hand industriously on his overalls and then extended it with some diffidence.

"Glad to know you," he said.

"And I," said Creel, shaking hands with a heartiness that brought light into the eyes of the other, "am mightily glad to know a man who never fails in a pinch."

Flannery grinned with overmodesty.

"Oh," he replied, "I ain't so slow on the get-away. Maybe some of the flatties know me, but they got nothing on me. I broke a leg once and done my bit, but it was only a drag. And since then the dicks have never got a whiff of my trail."

The eyes of Creel wandered slightly, but he returned gallantly to the charge.

"I believe you," he said, "and it may be that we can do a bit of work together one of these days."

Flannery swelled visibly.

"You can count me in," he said, "on anything from a gat play to soaping a peter. Why, captain, I'd go along just for the sake of watchin' you work!"

Creel waved his adieu and went on with Payson. "Gat play" and "soaping a peter" and doing a "bit" and a "drag" were far beyond his comprehension. He thanked his Creator for a liberal endowment in the power of silence.

"If you could let me have a peek at the stuff," urged Payson as they approached the house, "I'd be eternally grateful. I'd feel as if I had something on the rest of the lads."

Creel hunted desperately through his mind for an answer.

"But I suppose," went on Payson, "that you want Anne to have the first look. Well, it's her right, I guess. Personally, Ormonde, I think you're getting her cheaply even at the price of the Bigbee case; for she's a jewel among women, lad, and I'd back her with my life and everything I have. But—you don't mind if I speak frankly?—considering you in the light of your past history, I'm damned if any of us can understand how you took up with such a romantic idea as this!"

It came home to Creel for the first time clearly, and the blow of understanding stunned him. In that house was a girl named Anne with whom he was supposed to be in love; as the price of her love he was bringing from England the Bigbee case, though what the Bigbee case might be he had not the slightest dream. Hitherto, he had gathered that only the arrival of the real Edward Ormonde would reveal his identity.

But Anne—the first glance from her would disclose him to the others; and then would follow that annihilation to which Payson had referred as they rushed in the car toward the gate of the place. Yet even now, after the first shock, he was not unhappy. Boundless hope filled him: the sense of approaching danger was like wine in his blood.

The door opened before them when they had climbed the broad steps leading up to the porch and a servant, perfectly groomed as the most conservative of servants, stood holding it wide. Within Creel saw a spacious hall with a lofty ceiling; within he knew the power of the gang, whatever it might be, would close around him. There was still a chance of escape, perhaps. Yet the imp of the perverse urged him on once more. He crossed the threshold with a light step which was instantly silent on the thick rug within.

The door closed with an almost imperceptible click; the final step was taken. He gave his light overcoat and his hat to the servant. Payson had already deposited his bag and now shook a warning finger at the servant.

"And, mind you, Harry," he said gravely, "no trifling with that bag or anything in it."

"Aw, listen, chief," drawled Harry, "maybe I'm a dub, but I ain't so green as to play him for a fall guy!"

"That'll do!" said Payson sharply.

The servant stiffened back to his former manner instantly. The difference between it and his attitude of the instant before was as great as the change from the stiffly starched shirt from the laundry and the crumpled rag which is tossed into the laundry bag.

"Yes, sir," he said. "Very good, sir."

And past his blank stare they walked into an inner room. Here three gentlemen rose at once to greet them. They looked to Andrew Creel very much as he would have expected the owner and the guests of such a mansion to appear. They were all well past middle age; they were perfectly groomed; courtesy looked from their eyes; their manner was, one and all, the manner of the man of the world. Creel had seen such men in every great cosmopolitan city. What he had heard led him to believe them a gang of unscrupulous thieves; his senses showed him in mien and manner three complete gentlemen. Payson stepped a little away from him and bowed both to him and to the others.

"Gentlemen," he said, "I have the honor of presenting to you Mr. Edward Ormonde, of England, and now, I trust, of America. Mr. Ormonde, these are my friends and yours: Mr. John Rincon, Mr. Matthew Kingston. Mr. Robert Lorrimer."

ANDREW CREEL surveyed the three cultured reprobates with a passive eye. Mr. John Rincon was very little, very withered, and very red. His complexion was so violently sanguine, indeed, that one felt as if the skin were of tissue paper thinness—as if the rubbing of the fingers against it would break the delicate tissue. It gave him an appearance of extreme boyishness which made a singularly grim contrast with the frailty of age. This contrast was sharpened, made ludicrous, by a bass voice so tremendous that it filled the apartment and came booming back from the walls; when he spoke his chest labored heavily and perceptibly.

By his side stood Robert Lorrimer. He was almost as tall as Payson himself, but not a tithe of the latter's bulk. He had a bushy, white mustache and a fluff of silver hair so thin that it stood up with every touch of a draft. His baldness accentuated a truly remarkable forehead. It was divided by a sharp line in the center, like a perpetual frown, which threw into relief the two swelling lobes of that great brow. It was his habit to speak slowly, thoughtfully, in a voice so faint and husky that at times he was almost unintelligible, and he continually paused to clear his throat.

Of the three Matthew Kingston seemed by far the youngest, but he was of that plump type who resist the approach of years. For the rest, he was quite ordinary in appearance, except that his eyes continually twinkled as though he were enjoying some secret jest. He seldom spoke, even to his intimates; he was prevented by a voice so shrill and piping that it brought an instant smile to the face of an auditor.

Accordingly, while the other three shook hands and expressed the appropriate pleasure in the introduction, Matthew Kingston murmured something unheard and let his smile take the place of words. Little John Rincon immediately took possession of Creel's arm.

"Come, come!" he said in that terrific voice. "Sit over here by the window—in that chair—so!—now we have a look at you. Well, well! So this is the great Ormonde! Sir, I shall mark this day in red chalk."

"And I," said the faint voice of Robert Lorrimer, "look forward to a long chat with you—a very long one, indeed, Mr. Ormonde!"

As for Matthew Kingston, he said not a word, but he stood with his pudgy hands clasped behind him, teetering slowly back and forth from heel to toe and smiling benignly down upon Creel.

"And where's Anne?" asked Payson. "I suppose that would be more to the point with Ormonde?"

"Of course it would, and she's due directly—she and her father. A dear girl, Ormonde, and we envy you your good luck!"

So saying, he rubbed his little, claw-like hands together and laughed with deafening heartiness.

He continued: "They'll be in directly; they didn't expect to see you here so soon. Quick trip, Payson, old boy!"

"And now," suggested Robert Lorrimer, "a peek at the Bigbee case, eh?"

"Not at all!" protested Payson, and he raised his big hand. "Not at all! Let Anne have the first look at 'em. After all, she's to pay the price!"

His chuckle over this witticism called forth a soft-voiced but stern rebuke from Lorrimer:

"My dear Payson, you are not in the slums, you know. You really are not. I wish you would watch your vocabulary."

"Rot!" blurted Payson. "Ormonde's a man: he takes no offense at a harmless little jest."

"At least," murmured Lorrimer, "Mr. Ormonde is a gentleman; and as such he will forget. Well, Mr. Ormonde, we all regret that our chief is not here to welcome you; but perhaps you're already acquainted with him in some other place? His name is James Ashe—to his friends."

"I have never had the pleasure," answered Creel.

And he wondered at the man who could be named chief in such a circle of accomplished scoundrels.

"It is to be regretted," said Lorrimer. Here he lowered his voice so that there was a singular emphasis on all that followed, though it may have been due to the constitutional weakness of his throat. It gave the impression that he excluded the others in the room from his comments, as though Ormonde alone could understand and appreciate. He said:

"It's a full month since Ashe left us. In fact, he departed almost immediately after we received word of your offer, your most unusual offer, sir!"

"Unusual?" boomed Rincon. "By the Lord, yes, and most welcome! But I'd like to know this: was it for the sake of poor Berwick or for his daughter alone, or for both of them, that you have acted with this—"

"Unprecedented generosity," filled in Lorrimer. "I'll wager that both reasons operated on Mr. Ormonde—both humanity and—a love of the beautiful."

He pointed his speech with a slight and graceful bow toward Creel, who suavely replied:

"That's kind of you. And, in fact, you're right. You have described the lady yourself, and Berwick is—"

He paused, as though hunting for a word and Lorrimer, as he had expected, came again to the rescue: "A traitor," he suggested, "and a coward, but—a human being. None of us suspected him on either count until he stole the Bigbee case from us; afterwards he showed in his true colors."

"Yellow," blurted Payson, "just damned yellow—the dog!"

"Come, come!" protested Lorrimer, and he raised a thin- fingered hand. "There are qualifying remarks to make. He pretended that he wanted to make enough at a blow to retire and set up an establishment of his own for the sake of Anne. Treason? Yes, but let's bear the redeeming features in mind. On the whole, Mr. Ormonde, I'm very glad that Berwick is not to be sacrificed—though you must admit that our provocation was extreme."

"Intolerable," agreed Creel calmly. "Absolutely!"

"I'm glad you agree," sighed Lorrimer, "I wouldn't have had you think us inhuman!"

"Lorrimer!" cut in Payson. "Don't be such an infernal, cold- blooded hypocrite; don't you suppose Ormonde knows us already? Are you going to try to pull the wool over his eyes?"

"Payson," said Lorrimer gently, "you sadden me; you cut me to the quick!"

"Oh—" began Payson, and then shut his teeth with a click and finished his sentence by bringing a huge fist snapping home against the palm of his other hand.

"Whatever I know," said Creel, who could not refrain from smiling, "always I am glad to have my ideas amended and improved."

And he favored Lorrimer with his most courtly bow. All the time he had been measuring the four; he had been estimating their strength of body and mind. He knew that he balanced over a gulf of destruction, but the danger did not paralyze him. He recognized with a sudden wonder that he was not afraid to die. The threat suspended over his head merely served to clear his mind, sharpen his insight into the soft-voiced cruelty of Lorrimer, the brutality of Payson, the silent malice of Kingston, and the inhuman viciousness of Rincon.

What he would do he had not the slightest idea. The coming of Anne would precipitate the final action; the coming of the real Ormonde would do the same thing.

In the little breathing space of suspense that remained to him, he found life incredibly dear, but the excitement of the moment was even more priceless.

"Thank you," Lorrimer was saying, "and, in spite of Payson, I want to assure you that it was not I but Ashe who pressed us to put Berwick out of the way; in fact, to the very end the firmness of Ashe was incredible. He was so set against accepting any ransom for the life of Berwick—even the lost Bigbee case—that I feared for a time." He completed his sentence with a marvelously expressive shrug of his shoulders.

"The truth is," broke in the thunder of Rincon, "that Ashe is pretty fond of Anne himself. He fought tooth and nail against a ransom for Berwick so long as the price of that ransom was to be Anne herself. But she settled it herself when she told him that if her father died she would lay the death at his door. Also, we voted Ashe down for the first time—even though Lorrimer was on his side!"

"Tut, tut!" said the soft-spoken Lorrimer. "Are you going to rake up old scores? It was a matter of policy, my dear Ormonde! Surely you will understand that it was a matter of mere policy; I could not consult my own humane instincts against the safety of the circle."

"Matter of mere life or death for Berwick—the cur!" said Payson. "But now you're safely here, Ormonde, I'll tell you a suspicion I've had. You see, Ashe left us immediately after we'd decided to accept your offer and spare Berwick in return for the Bigbee case. It was my personal opinion that he went to England to do you wrong—dispose of you, in fact, before you could bring the case back to us and take Anne away with you. Now I suppose Ashe merely went away to be by himself. He's terribly wrapped up in Anne, but I suppose he's submitted to the inevitable. I hope so, at least."

"Yes," roared Rincon. "A rare mind, that! He established us, you know."

"Ah," murmured Creel. "Tell me about that!"

"You do it," said Rincon to Lorrimer. "You're the orator."

"YOU flatter me," smiled Lorrimer, and he went on in his slow, almost faltering manner: "You see we were all once ordinary—er—business men—all of us. Our finances were tied up in the affairs of a great bank. For obvious reasons I cannot name the bank even to you, Mr. Ormonde."

"Certainly not," agreed Creel.

"Thank you. Well, then, we were all heavily engaged to the interests of this bank, as I was saying, when it failed. Yes, sir, it failed utterly owing to embezzlement—the stupidest, most transparent embezzlement which had been going on for years, and no depositor suspected it and none of the directors.

"At any rate, the embezzling went on, and on one fine day we discovered that we were ruined—all of us. The bank couldn't pay ten cents on a dollar: a disturbance of the Street helped to tear things to pieces. Well, sir, eventually we were gathered together—twenty-two good men and true, eight years ago almost to a day. We had one common topic which bound us together—our complete financial ruin. Some one remarked that if a man of mere uninspired common sense was capable of robbing a great bank with impunity for years, a group of intelligent men would probably be able to rob the world with impunity forever. Needless to say, the man who made that remark was the very youngest of us all—James Ashe.

"In ordinary circumstances the remark would have fallen on barren ground as a mere commonplace, but we were twenty-two desperate men; we felt that the world owed us some return for the honest money we had gathered and had lost."

"Honest?" growled Payson.

"As for your affairs," smiled Lorrimer imperturbably," I'm sure that I can't express a well grounded opinion."

"Well," began Payson, but stopped short, and Creel wondered to see the giant quelled by the calm voice and the smiling eye of old Lorrimer.

"We felt, I say," resumed the narrator, "that we deserved compensation and that whatever we could get, the end would justify the means. Some one took up the comment of Ashe—"

"It was yourself!" bellowed Rincon.

Lorrimer reproved him with a glance and continued:

"And supported him with a little impromptu sketch of the opportunities which might open before such an association. By the time his talk was ended others were ready to add remarks. Well, sir, that meeting lasted far into the night, though it began in the middle of the afternoon, and before the meeting broke up every member of it was pledged to secrecy and faithfulness to a new organization of a character which you may be able to surmise. We had accepted a constitution and we had named young Ashe as president. The great work was under way!"

As he paused Creel interpolated the question: "Twenty- two?"

"You naturally wonder at the number," agreed Lorrimer, "when we are now only six all told. But, you see, it was found that some of the men weakened from time to time, and the moment they weakened it was necessary that the rest of us should dispose of them. We appointed a secret committee of three to ferret out the discontented and the weak."

"And you headed the committee," commented Payson.

"And did my work thoroughly," said Lorrimer with a sudden metallic ringing of his voice, as though the memory stimulated him to an almost youthful vigor. "Did it thoroughly and would take the same steps again in case of need! When one of my committee failed me, he fell by my hand!"

His manner changed instantly, and passing his fingers through the fluff of silvery hair, he pursued his tale with a voice as soft as dripping honey:

"But those harsh days are long past, the Lord be praised! In five years the only defection has been that of poor Berwick. But to go on.

"When our number was so sorely diminished we finally decided that the remnant of the original members should no longer take an active part in the outside work except in cases of great need. We concluded that it would be wiser to constitute ourselves an inner council to plan, advise, and direct our active workers.

"These workers were recruited from various classes, beginning with what may be called the underworld of society and extending up to men of an incredibly high position. None of these was taken fully into our confidence and none was allowed to know the full extent or the details of our operations. Each was sworn, of course, to absolute secrecy, and the oath was reinforced by such proved examples of our power and instant execution of the unfaithful that our workers dread the decisions of the council far more than they dread the power of the law.

"Yes, sir, our power is felt so keenly by them that several of them have died in the chair refusing to confess to the law or to involve their directors even when pardon and police protection were offered as a reward for confession. Mr. Ormonde, I myself have witnessed two such executions, and on each occasion I was highly edified by the conduct of our unfortunate allies. They died like men; they proved themselves worthy of our society; and their names are inscribed in our memories!"

He made an impressive pause; and during it a chill went up the spine of Creel like a slowly moving piece of ice.

"As the result of these examples," said Lorrimer, "our organization is bound together with ties stronger than iron or adamant. We are dreaded more than the most horrible certainty of death; we can trust our members in every crisis. Moreover, they are forced to obey the least of instructions. They execute our orders not only in effect, but in form. In this manner we are enabled to conduct the most serious operations without unnecessary waste of life; a result which is highly gratifying to us all, needless to say!"

"Sir," said Creel, "your restraint is obvious and commendable."

Lorrimer bowed profoundly.

"Praise from Edward Ormonde," he said, "is praise indeed; but will you allow me to comment that you have not always showed the constraint which you now praise in us?"

"Explanations," said Creel carelessly, "never take much of my time. I will only say that when an end is before me I accomplish it by the most direct means. If there is opposition I destroy it; if there is revenge, I take my chance with it. And what, Mr. Lorrimer, is life without chance? It is profitable, perhaps, but very stale and weary!"

"Ah," murmured Lorrimer, "that is the opinion of a brilliant and self-confident artist, but in the end—well, each to his own preference. I prefer a longer life even if it is somewhat less crowded with action."

"And now that you've heard a little about us," boomed Rincon, "won't you favor us with something out of your own past, Ormonde? We're eating our hearts out with curiosity."

The others agreed with sparkling eyes.

"What, gentlemen, would you suggest?" asked Creel.

"The Gastonbrook affair!" cried Payson.

"The story of the two Lancasters!" said Rincon.

And the ludicrous, piping voice of Matthew Kingston now spoke for the first time: "The Van Zanten pearls!"

Creel swept them with a lingering glance of good nature.

"Ah," he said to Kingston, "I see you have an eye for the spectacular even more than the others. Now let me be perfectly frank with you: I rarely tell stories connected with my past."

He watched them exchange glances of astonishment.

"Why, Ormonde," came the roaring voice of Rincon, "we have understood that the most singular part about you is that you are always willing to confide in others any detail of your operations!"

"And so," growled the others, "have we all understood."

"No doubt, no doubt," answered Creel airily, "and as a matter of fact, that is the impression which I have always attempted to convey. But I draw a line of distinction between others I have talked to and you—my very good friends! I have talked—yes, but though I've handled the near-truth often enough, I've always avoided the exact details.

"In place of the actual happenings, when it came to the finer points, I've always substituted little touches of the imagination. For you see, gentlemen, I could not expose my methods in their entirety. I expose enough to make others believe they know all; I reserve the really distinguishing features. It is necessary. But with you, sirs, I prefer to tell the whole story or nothing at all. And of the two choices I'm sure you will forgive me if I select the second and say not a word about my past."

Lorrimer and Rincon exchanged glances, but Payson said instantly:

"That's what I call straight-from-the-shoulder talk, and I like it. Ormonde, I think more of you now than I ever have before. To tell you the truth, I've always had an idea that you were a windy, conceited, clever—damned fool. But I retract all my former opinions. And here's my hand on it!"

Before Creel could answer, Rincon announced in his terrific voice:

"And here you are, Ormonde. The lady is with us!"

LIKE the rest, Creel rose from his chair and turned toward the door—slowly, for when he faced that door at last he expected a sharp outcry of surprise that would bring weapons into the hands of every man in that room.

He turned, steeling his nerves, and when he saw the figure in the door he received two shocks which almost destroyed his reserve of nervous endurance. She had been riding, and she stood in the doorway, tugging off her gloves. The derby hat sat jauntily just a trifle to one side, and under it there was sunny hair, and flushed cheeks, and straight, black eyebrows. That was the singular feature—the bright hair, and the black of eyebrows and eyes.

In every respect his expectations were upset. For here was pride in place of boldness and feminine poise in place of worldly complacence. It was a darkly furnished room, high-ceilinged, of puritanically severe proportions, and spaciousness almost its only charm; she came into it like a touch of the fresh outdoors, like a sudden burst of living sunshine. At sight of Creel her eyes wavered an instant and the flush of exercise rushed into a flame of color; but at once she controlled herself and walked straight toward him, smiling faintly.

It was this that shook Creel's self-control to the core. This was the woman with whom Ormonde was supposed to be in love, and yet she did not know his face! In his utter confusion he must have betrayed himself if she had reached him, but now a man came from behind her, almost trotting in haste, and rushed upon Creel.

It was a little man, plump, with a well-rounded vest that shook as he hurried forward. His face had small and regular features which had once been extremely handsome, no doubt, but good living had blurred and disfigured that face with fat, loosening the mouth, almost obscuring the eyes; and this fat, in turn, recent anxiety had converted to flabby folds.

Purple pouches were under the eyes, and grim lines ran past the mouth, and under the chin hung a loose pocket of flesh. He came now, illumined with inward light, and seized on both the hands of Creel. His own were at once cold and moist and slippery to the touch.

"You are here!" he cried when at last he could speak. "Thank God you are here at last—my boy—my son! Ormonde, God bless you for what you've done for me."

A repulsion against which he could not fight swept over Creel; he jerked his hands free and stepped back.

"I can't keep silent any longer," he said, facing Lorrimer instinctively. "I've come a long ways simply to tell you that I haven't the Bigbee case with me!"

It was singular to note the manner in which the different people received the information. Payson, the smile wiped from his face, remained staring stupidly; Rincon turned from red to purple; Matthew Kingston turned on his heel and strode toward the far end of the room; Lorrimer sat bolt upright, clasping the arms of his chair, and a devil glittered in his eyes; the girl had turned utterly white, as though one stroke of a sponge had wiped the color from her face, yet there was something akin to relief in her sigh. As for Berwick himself, he had, in spite of his repulse of the moment before, been nodding and grinning; now his nodding and his grinning continued, but his eye was blank. He turned to the girl.

"Anne," he said feebly, "what does it mean?"

Some of her color returned—a burning spot in either cheek—and her eyes fixed and narrowed upon Creel.

"I think it means what the words said," she answered slowly.

"Then God help me!" moaned Berwick, and fell rather than sank into a chair. His daughter regarded him with a singular mixture of sympathy and scorn.

"Do you expect him to help you?" she asked harshly, and then dropping to her knees with a little cry of sorrow, she threw her arm around his shoulder and commenced to murmur little words of comfort; the two were quite shut off from the others.

Of the rest, Creel was the least discomposed. For he had expected sudden ruin with the entrance of the girl, and now he had at least a fighting chance left him. He sat down in a chair and commenced to drum his fingers lightly on the arm.

The others remained still unchanged in their attitudes, their glances one and all fixed ominously upon him, when a whistling broke in upon them with the opening of some outer door. Lorrimer smiled without trace of mirth and turned his evil eye toward the entrance to the room and then back to Creel.

"That's the whistle of James Ashe," he said, "and he comes in good time. He will have something to say to you. Mr. Ormonde: and the rest of us will abide by his decision. Ah, Jimmy!"

It was a man of very broad shoulders, the rest of his body tapering down so that he gave a promise of agility as well as terrible physical strength. There was nothing distinctive about his face save the massiveness of the jaw which gave him, in repose, the expression of one who has just set his lips in determination.

"Ashe," cried Rincon in his great voice, "here's Edward Ormonde at last!"

The man with the massive shoulders started, whirled until he faced Creel directly, and then walked hastily toward him. He came to an abrupt halt half a pace away and surveyed his man with manifest insolence from head to foot.

"You!" he snarled. "You? Edward Ormonde?"

"And he came," cut in the soft voice of Lorrimer, "without the Bigbee case!"

"Ha!" said Ashe, and whirled toward the speaker. "Without the Bigbee case, did you say?"

And then, strange to say, he dropped into a chair and burst into a convulsion of laughter—Homeric laughter; it seemed inextinguishable; it came roar on roar and peal on peal. It reduced him to a shaking bulk which loosely filled his chair from arm to arm. Then he sobered with an equally astonishing suddenness. He sat erect and regarded Creel with an undisguised sneer.

"So—Edward Ormonde"—and he gave the name an odd emphasis—"you came, and without the case? It was all a bluff? And just what is your purpose, my friend, in coming at all?"

"My dear fellow," said Creel, unmoved, though he understood at once that Ashe knew he was not Ormonde. "My dear fellow, in a dozen lifetimes you would never guess why I am here."

He was strong with sudden confidence; something kept Ashe from telling what he knew. Something would continue to prevent him, whatever the reason might be. On that score, at least, he was safe, until Ormonde himself appeared. But why did not Ormonde come? He was already long overdue.

"I want to call to your attention, Mr. President—" began Lorrimer coldly.

"What?" called Ashe, now grave indeed. "What do you mean by that?"

Lorrimer waved a hand of protest.

"Naturally," he said, "when Ormonde came I told him freely about our organization."

"Naturally," said Ashe with heat, "you are just clever enough to make an ass of yourself at times, Lorrimer!"

He glanced fiercely at Creel, then shrugged his shoulders and relaxed in his chair. "Well, go on."

"What I call to your attention," said Lorrimer, overlooking the rebuke, "in that Ormonde has imposed on us, grossly. He keyed up our expectations; he led us on; he lied to us in his cablegrams."

"I only interpose to remark," said Creel, "that I have never lied to you in a cablegram."

"Ah!" said Ashe. "You never lied in a cablegram addressed to us? Well, I believe you!"

And he burst again into his heavy laughter.

"Is it a laughing matter?" bellowed Rincon, smashing his claw-like fist against his knee. "I tell you, Ashe, we've let Ormonde into our inner circle to-day! That was natural when we thought we were getting a sufficient pledge from him—and giving him one in return. But what about it now that there's no tie between him and us?"

"It's perfectly simple," said Ashe. "We remove Mr.—er—Ormonde from our midst."

"Turn him loose without any bond from him?" cried Lorrimer, "Ashe, have you departed from the last of your senses?"

"I used the word 'remove'," answered Ashe dryly, "in a sense which I was sure you, at least, Lorrimer, would not fail to understand."

"Ah!" cried Lorrimer, and a grim joy lighted his eyes. "Remove him? Good! Very good indeed. He's trifled with us and your decision is admirable—admirable!"

He sat with his glance hungrily upon Creel and his lips parted like one who drank, deeply.

"Let him be—removed—and perhaps at the same time that Berwick pays his penalty?"

THIS brought Berwick himself sharply out of his prostration. He sprang to his feet, tearing himself away from the sheltering arms of Anne, and stretched out his arms to Lorrimer.

"Bob!" he screamed. "Stand by me!"

And when Lorrimer replied with a smile so slow, so calm that he seemed to be remembering a jest from the distant past, the little man turned with a shudder to Ashe.

"Jimmy," he said hoarsely, "if I go—the way that devil Lorrimer wants—you know that you and Anne can never—"

"Stop!" cried Ashe, his face livid with restrained passion. "Berwick, you swine, do you dare to call her name in like a dirty-handed tradesman? You—"

He checked himself with infinite effort and tried to turn a calm face to the girl.

"Anne, you know I can't decide this thing by myself. You know, it's merely the will of the majority which counts?"

She answered him with a glance of scorn, and once more with the same mixture of contempt and pity she took the arm of her father.

"Don't you see?" she murmured to him. "Nothing you can say will influence them. We must leave them."

"Not this way!" screamed the little man, now hysterical with terror. "Lorrimer, I didn't mean to call you a devil! Lorrimer— Bob—old friend—you know you can save me?—you and Ashe."

His words fell away to stammering under that continual, changeless smile of Lorrimer.

"If you don't come now," said Anne fiercely, "I'll leave you to yourself!"

He shrunk instantly close to her side and clasped her arm in both his pudgy hands, saying in a broken voice:

"No, Anne! Not that! My girl, my good girl! Stand by me still. It's murder otherwise. Don't you see it? Don't you see it?"

And he went at her side from the room. Before they reached the door she was supporting almost all his staggering weight. Lorrimer turned his smile upon Creel.

"A disgraceful and unfortunate scene, Mr. Ormonde," he said, "and I apologize in the name of all the rest for it. But even in the best families—I'm sure you will understand! And now"—he glanced to Ashe—"what is to be done with our distinguished guest?"

"You have already named it," said Ashe coldly, as if the problem of Creel's disposal in no wise interested him. "But for old Berwick—the cur—I'd like to ask for a slight delay of execution."

"The good of the order before your own welfare, Ashe," cut in Lorrimer.

"I'll remember this, Bob," said the president with infinite meaning. "Remember me, too, then, and be damned!" cried big Payson. And then in a quieter voice: "Listen, Ashe. We all know how you feel about Anne, but we can't let you have her at the cost of turning Berwick loose. None of our lives would be safe for an instant. You know that if you're half the man you used to be."

The struggle which went on inside Ashe rendered him perfectly colorless and brought a gleaming sweat to his forehead. Finally he was able to say:

"The majority rules. Well, let it go at that! And I'll try to forget the bad feeling that's behind it. It remains to name the time and the means of finishing Berwick and stopping that smile."

For Creel leaned in perfect comfort against the upholstered back of his chair and surveyed the assembly with a smile that never faltered.

Here the ridiculous, piping voice of Matthew Kingston broke in: "The time—one hour from now; the means—myself!"

It suggested the cruel malevolence of a child united to the strength and purpose of a grown man, and was doubly terrible.

"Now, don't you think," came the sudden roar of John Rincon, "that Edward Ormonde is a terrific fool if he shoves his head into the noose in this fashion? Do you suppose that the man we know as Edward Ormonde would cross the Atlantic to make an ass of himself in this manner? I tell you there's something behind it!

"Even Edward Ormonde couldn't wear that smile if he didn't have something up his sleeve. Come, Ormonde, no matter what you may think now, we'll prove to you that we're reasonable and that we'll meet you halfway. What's your scheme? And if you haven't the Bigbee case, what have you done with it?"

"There's sense in that," agreed Payson. "I don't follow this game; it's too complicated for me; but I see that there's something behind the scenes."

"Why, gentlemen," answered Creel, "you honor me by suggesting that I have something up my sleeve, whether it's the Bigbee case or something else."

"Ah-h!" broke in Lorrimer. "It's clear to me! He left the case somewhere before he came out to us. He wants something more than the girl before he'll come to terms. Well, Ormonde, what the devil is it that you wish? I repeat, we're reasonable; but if you play this game too long it's liable to end with a mighty sudden period."

The face of Ashe contorted to something strangely like a smile. He said:

"I think I know the way to solve your troubles, gentlemen. But first I should like to be alone with Mr.—er—Ormonde, for a few minutes. Does any one object?"

There was general assent and the others left the room at once. Until they were gone, Ashe remained seated with his eyes fixed upon the floor; then he raised them suddenly to Creel. He was smiling openly.

"Now, sir," he said, "I saw through your bluff from the first. I haven't told the others what I know because it would have been death for you within an hour, and I admire a cool head too much to see you come to an end like that. Whatever your name is, and whatever your purpose in coming here may be, talk to me frankly, sir. If it comes to a pinch I think I can save you, but first I must know exactly who and what you are."

"I am," said Creel thoughtfully, "a pursuer of pleasure who has recently acquired a serious purpose in life."

"Very good," nodded Ashe. "An eccentric; I thought as much. Well, my friend, I'm prepared to hear you with sympathy. My own pursuits have been rather various. And now, your name?"

"Ah, there's the rub! You're sure that I'm not Edward Ormonde, it seems?"

"Come, come!" chuckled Ashe, and waved the suggestion aside.

"How sure are you?" went on Creel, for he was feeling his way with the utmost caution. He knew, now that he could secure safety if he confided everything in Ashe, but safety would be purchased at a price whose greatness he had just come to appreciate.

"I am as sure," went on the other, "as I am that my real name is not James Ashe."

"My dear fellow," smiled Creel, "that's not nearly sure enough!"

Ashe frowned.

"Besides," said Creel with unbroken calm, "you have never seen Ormonde in your life." And he added: "Face to face!"

At the beginning of that speech a faint smile touched the corners of the mouth of Ashe. At the end of it he was sitting stiffly erect and his gray eyes narrowed upon Creel.

"How do you know that?" he asked sharply.

Creel, tremendously relieved, laughed easily.

"Very well," said Ashe, "you insist on maintaining your identity as Ormonde?"

"Really," said Creel, "the name suits me as well as another. There's an aristocratic twang to it that I like, in fact."

The frown of Ashe deepened. He said: "I'm a very busy man, sir. I'm not here to trifle with you over absurdities. Come! Out with the truth! What are you?"

Creel fell back upon a touch of the mystic.

"If you knew," he said, "you would not believe the testimony of your own senses."

"You see," said Ashe, "I'm treating you with patience. I'm giving you your chance. Another question: What brought you here?"

"You already know it. Anne Berwick."

It brought Ashe to his feet.

"Anne?" he echoed.

"I knew," replied Creel, smiling up to him, "that that spur would touch you up a bit."

"I'm a very bad man to touch up," answered Ashe heavily. "A very bad man, indeed. So you came here for the sake of Anne?"

"At least," said Creel, "you may understand me better if I say that I expect to stay here for the sake of Anne."

There was a pause. At length Ashe answered in the same deep voice: "Then God have pity on your soul!"

"Thank you," nodded Creel. "I shall not need to solicit Him."

"You are either a fool or very wise or a madman," said Ashe slowly, "and I suppose you're the last of the three. But madmen, sir, are not exempted from the penalties of our order. To us you are dangerous; you know it; you persist in maintaining a silly bluff. Do I have to warn you again?

"Come! I do not dabble needlessly in blood. I assure you that the simplest thing would be for me to turn you over to the tender mercies of Matthew Kingston, but I will make one last effort to save you from your own folly. My friend, I invite you for the last time to speak openly and frankly to me!"

Creel became grave. He said:

"I know your record, Ashe. I respect it; I don't like to see you make a fool of yourself. So I will speak frankly as far as I can. In the first place, I am Edward Ormonde; in the second place I didn't come here unprotected."

"Bluff!" broke in Ashe angrily. "Childish bluff, and it doesn't work. What else?"

"Ashe," said Creel, and he rose from his chair and faced the big-shouldered man. "Look at me! Don't you see that I'm not afraid of you?"

The glance of Ashe, obediently, narrowed and pierced deep into Creel. He changed color suddenly and seemed to sway back, defensively.

"It's true," he muttered, "you're not afraid, though why in the devil you aren't is beyond me. My friend, it would be as easy for me to dispose of you as it is for me to close my hand!"

Then, for he saw that the crisis had come, Creel made the final test. He spoke in a voice as calm as before.

"I wanted to give you more time, Ashe," he said, "but if you insist on running at the stone wall, go ahead. If you're determined to bring the test of strength now—go ahead!"

He turned on his heel, for it was impossible for him to conceal his inward excitement any longer, and crossed the room to a window, his back turned squarely upon Ashe. Standing there, he slowly drew out a cigarette, lighted it, and blew a long puff of smoke toward the pane.

His heart was thundering in him; he could only pray that Ashe would not note the tremor of his hand as he raised the cigarette to his lips; and all the time he felt the eyes of Ashe burrowing into his back.

It seemed an age before Ashe said suddenly: "It's bluff, of course, but, by the Lord, it's done well enough to win!"

Here Creel turned toward him, smiling.

"I knew," he said, "that you would be reasonable."

"Well—Ormonde—" said Ashe, and he smiled in mockery as he repeated the word: "I'm going to advise my friends to give you a respite of three days. I'm going to tell them it's my belief that you have secreted the Bigbee case and that if we give you time enough you will produce it when you see that you cannot extort better terms from us. The day after to-morrow, when it is completely dark, your respite ends."

"Why," murmured Creel, "this is even more generosity than I anticipated. And what, Mr. Ashe, moves you to grant me so long a respite?"

"It's partly because I admire the coolness of your bluff," admitted Ashe, "and partly because I freely confess that you puzzle me. Nine chances out of ten, of course, there is nothing to the puzzle, but I'm going to give myself a little time to decipher you. That's all."

"All?" smiled Creel. He stepped closer to Ashe and lowered his voice while his smile persisted. "Does fear take no part in your motives, Ashe? Not a little touch of fear?"

"By God!" cried Ashe. "What are you, devil or man?"

"Fear?" repeated Creel. "At least, I hope not. It would be a blot on your very excellent record. I suggest another thing. Do you value Anne?"

The jaw of Ashe set hard, but he returned no other answer.

"Because if you do, you had better keep me away from her; give me no chance of seeing her. I warn you, Ashe."

And his smile broadened. Ashe seemed on the verge of speech, but he restrained himself like a man of deep passions, who has schooled himself to self-control.

"Because at present," went on Creel, good-naturedly, "you stand much better with her than you would ever imagine, Ashe. Of course she dislikes many things about you—your violence and your frequent cruelty and a certain rough surface you have. But she admires your strength, your directness—and your love moves her. So you see, Ashe, you stand much better chances with her than you dream."

"Go ahead," said Ashe with a feeble attempt at lightness. "At least, you are amusing."

"Thank you. Keep her father from danger for a while longer; make her feel that you are his bulwark. In that way you will establish close diplomatic relations with her and who can tell what treaty might eventually be evolved!"

"But if I let her see you?" said Ashe, flushed with a growing excitement.

"Then you are lost!" said Creel solemnly. "Within twenty-four hours I will have won her completely away from you. You are right in fearing me—in two ways, Ashe."

"Bah!" snorted the big man, trembling with a strange mixture of rage and curiosity. "If I were ten years younger I might believe you. As it is, I read you like a book. Fear to let you see Anne? By God, sir, you can meet her at any time of the day or night! I shall give directions that you are to meet her openly; I shall have her thrown together with you."

"Good again!" said Creel. "You refuse to run against the stone wall, but you are willing to jump over the precipice."

"I have other things to do now," said Ashe coldly, "and I must leave you. Remember! The day after to-morrow by the time it is completely dark, we will expect from you the surrender of the Bigbee case or something leading immediately to its recovery. Failing that—" He made a widely inclusive gesture.

"For the rest, I shall instruct that you are to have every comfort and every liberty. It is only fair to warn you, however, that your liberty has strict bounds. If you attempt to descend the cliff to the sea or if you attempt to pass beyond the stone wall which bounds the grounds, you will be instantly shot. Those limits are continually watched. I assure you, it is perfectly impossible for you to cross them alive."

"Sir," said Creel, "I have not the slightest desire to imperil my life. I will cling close to the safety of the house."

"As for that," replied Ashe, "you are the judge. I have warned you. For your advice. I thank you profoundly. And I wish you the utmost success in finding the Bigbee case."

His smile was open mockery; speech had given back to him his equilibrium of temper.

"You must not trouble yourself about that," said Creel. "The day after to-morrow before it is completely dark, I shall place the Bigbee case in responsible hands."

Ashe, who was turning to leave the room, halted an instant; but he shrugged his shoulders at once and walked away through the door.

THE most experienced and courageous man of action might well have resigned himself to despair in the position of Andrew Creel, but the very fact that he had never before faced a crisis was now a help to him.

If it can be understood how nearly his former life had been an extended sleep, it can be taken for granted that on awakening he accepted the world as he found it. A place of peril, but for that very reason a place of infinite charm. It must not be imagined that he had found a scheme through which he could deliver himself from the power of Ashe and his companions, or that he forgot for one moment that the crisis awaited him at the little distance of two days.

But the two days themselves were as long as two eternities to the awakened senses of Creel. It seemed to him that he had never felt the warmth of sunshine before; every ticking second of the clock brought home a new delight to him; and in the place of certainty of escape he found consolation enough in an endless hope.

For that matter the criminal feels hope even while he sits in the electric chair awaiting the shock of the current. Oddly enough the greatest disturbing element for Creel was the expectation of the momentary arrival of the real Ormonde, the man who had awakened him, even if it were by chance, the man who had talked with him on the bow of the ship, the man who had raised his hand and made that odd, unconscious signal. For his coming would precipitate the final event which was now, by the decision of Ashe, postponed for two priceless days.

In the meantime he wished to be out under the keen, blue sky every waking moment, so on his first morning, after a breakfast which was served to him in his room, he sallied out into the little inner garden. For beside the broad sweeps of lawn and flowers and trees which ran over the rest of the peninsula, there was reserved a comparatively small walled place filled with shrubs and the choicest flowers. So far as he could tell, no one observed his movements and no effort was made to keep him within the house.