RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

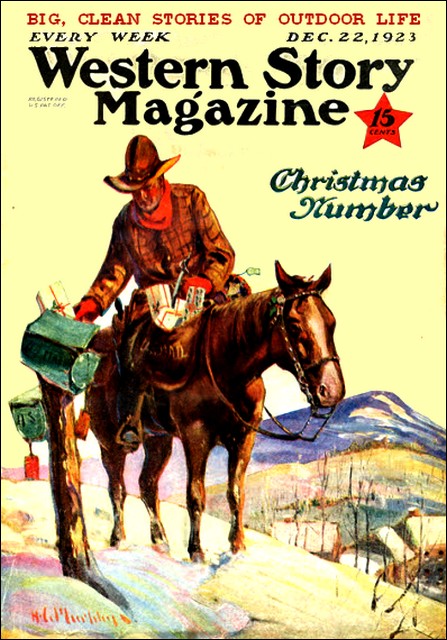

Western Story Magazine, December 22, 1923, with "The Boy Who Found Christmas"

WHEN I asked the judge about writing this, he said: "The way to begin, Lew, is to start out like this... 'I, the Kid, alias the Oklahoma Kid, alias Oklahoma, alias Lew, being twelve years of age and in my right mind, do affirm that...'"

"Judge," I said, "hand it to me straight, will you?"

The judge scratched his chin and said: "Tell them the whole truth and nothing but the truth." Then he winked. So I'm doing just what he said: telling the whole truth and nothing but the truth—with a wink.

I was born on Black Friday. The same day, my mother died and my dad lost his job. Them two things took the heart of him. She was a black-haired Riley, and he was a red-headed Maloney, and, when she died, everything went wrong for Dad. He never did no good for himself nor nobody else after that. The only way I remember him was when I was four or five years old. He used to put me on the bar and drink to me and tell me I was to grow up past six feet with a punch in both fists. The booze got him.

After he died, I went to live with Aunt Maria in a terrible clean house. Aunt Maria was a queer sort. She'd had a great sorrow in her past, someone told me, and was kind of sour on life in consequence. She was a good soul in a hard, severe way, but nothing religious about her, though. On the contrary, she hated church and ministers and all that like poison, wouldn't let 'em have anything to do with her, and was always reading books written to prove that they were all wrong in their beliefs.

This aunt of mine had four sons of her own, and what with me doing odd jobs around the place, fighting her boys, and getting lickings from her, times was hard. Her place was a ways out of the town and it was too far away for us—me and her sons, that is—to go to the district school even if she'd wanted us to, which she probably didn't. In the mornings, she'd put in an hour teaching us kids to read and write and figure, and that was all the schooling we got or were likely to get. It was all work and no play with Aunt Maria. She worked herself and made us boys work seven days a week, fifty-two weeks of the year. She never took a holiday herself and never gave us one. She was a hard taskmistress.

Then Missouri Slim blew in one day and seen me chopping kindling in the woodshed. I took to Slim right away. I'd seen plenty of rough and tough ones in my time, but Missouri was different. He was long and skinny. He had a big, thin nose and a little mouth and chin like a rat's, and a pair of small, pale blue eyes that never stopped moving. He was wearing seven days' whiskers, and he didn't look like soap bothered him none.

His clothes was parts of three different suits, and none of the three could ever have fitted. His coat sort of flapped around him with bulges in the pockets, and his trousers bagged at the knees and the seat, which showed that he done most of his hard work sitting and thinking. He looked like today was good enough for him and like he didn't give a hoot what come tomorrow. I figured he was right. He didn't talk much, neither, and, after Aunt Maria, that was sort of restful.

He says: "How old are you, young feller?"

"Seven," I says.

He watched me chop wood for a while. Then he pulled an old violin out of an old battered case and tuned her up. When he begun to play, smiling and with his eyes shut, I started seeing dreams. He finished and packed up his violin.

"Where you going?" I asks.

"Where nobody works," says he.

I asks him if that was heaven, and he allows that maybe it was. He says his first stopping place was down in the hollow just outside of town, near the railroad bridge, and that, if I wanted to see him and talk about the land where nobody worked, I could come down the next morning. He says he couldn't do no talking while I was chopping that kindling. He says it made him sort of sick inside to do any work or to see anybody else work.

"Look at that cow over in the field," says Slim. "Is she happy?"

"Sure," says I. "She's chewin' her cud."

"Has she done any work?"

"Nope."

"Look at them two dogs," says Slim. "Are they happy playin' tag?"

"I hope to tell!" says I.

"Do they do any work?" says Slim.

"Nope," says I.

"Nobody but fools work," says Slim.

I watched him out of sight. When I come to, Aunt Maria had me by the hair of the head.

"Not finished yet!" she says. "You lazy, good-for-nothing! Like father, like son!"

"My dad," says I, "was the strongest man in the county and the best fighter, and he never said quits!"

"It's a lie," says Aunt Maria. "He was a loafer, and he let a whisky bottle beat him and kill him!"

When it came to a pinch, I had a way of doing my arguing with my hands—until Slim taught me better. Now I grabbed a chunk of wood and shied it at Aunt Maria and hit her funny bone. It made her yell, but she was a Maloney, too. She caught me by one foot just as I was shinnying over the fence. When she got through with me, I couldn't stir without raising an ache. Besides, she sent me to bed without supper. I lay in bed, twisting around, trying to find a comfortable way of lying, but I couldn't invent none. Then I thought of Slim.

I went to the window and looked out. There was an old climbing vine that twisted across the front of my window. I smelled the flowers; I looked beyond and smelled the pine trees in the wind. Before I knew it, I was on the ground. I stood there a while, sort of scared at what I'd done and wondering if I could climb back the same way that I'd climbed down. I heard Billy and Joe snickering and laughing in the front attic room; I knew they was talking about me and my licking. I heard Aunt Maria rattling in the kitchen and finishing up her work. I smelled a couple of apple pies that was standing in the kitchen window, and they made me sort of homesick, but I told myself that I'd started along so far, that I'd better get the worst of it over before I come back to take my licking and go to bed again. I looked around me.

Take it by and large, the dark is pretty creepy inside of a house, but I seen that on the outside it was tolerable friendly. I could hear the frogs croaking out on the flat; I could hear crickets singing up and down the scale; the smell of pine trees was sweeter and stronger than it ever could be by day; and the sky was full of star dust and of stars.

There was nothing to fear as far as I could see or hear, except the black windows of Aunt Maria's house with a glimmer of light in 'em like the light in a cat's eye, and the noise of Aunt Maria in her kitchen. So I seen that there was nothing to worry about and lit out for the hollow beside the railroad bridge.

I come down through the trees and out into a little clearing, with the creek cutting through the middle, and firelight dancing across the riffles or skidding across the pool. There was four men sitting around the fire, drinking coffee out of old tomato tins, and in a sooty old wash boiler near the fire I could smell all that was left of a fine chicken stew. Maybe the Plymouth Rock rooster Aunt Maria had missed that day was in that stew. I hoped so. Three of the men had strange faces. The other was Slim. I come out and spoke up behind the place where he was sitting, sipping his coffee.

"Slim, will you let me eat while I listen to you talk about the land where nobody don't work?"

He didn't even look around. "It's the kid," says he, "the one I was telling you about. Are you hungry?" says he to me.

But I was already diving into the mulligan. I ate hearty. Now, says I to myself, when I couldn't hold no more, no matter how hard Aunt Maria licks me, this has been worth it! Then I looked up and seen they were all sitting around and watching me with their eyes bright, looking every one like the grocery man when he's adding up a bill.

"You've ate," says Slim in a way I didn't like at all. "Now what you got to pay for what you ate?"

I blinked at him and seen he meant it. "What's it worth?" asks I.

He looks at the others. "Forty cents," he says. "There was one chicken alone in that stew that would've cost anybody but me a whole dollar and a half. That ain't saying nothing of the two fryers that was alongside of him, and the onions and the beans and the potatoes and the tomatoes, and the work of bringing in the chuck, the cleaning of the pans, the building of the fire and the watching it, the picking of the chickens along with the cleaning and the cooking of 'em, the peeling of the potatoes and the slicing of 'em, and a lot of little odds and ends that's thro wed in for nothing. Forty cents is dirt cheap. It's lower'n cost, and what I got to have is cash!"

"I got no money," says I.

"Then you can pay with work."

"I thought that there was no work in your land," says I.

"Work or get money by your wits," says Slim. "It's all just the same."

"I got to work, then?" says I, backing off a little, for I could tell dead easy now that there was real trouble ahead of me, and a lot worse trouble than any I'd ever gotten into with Aunt Maria. "I'll do my work running," I says, and turns and run with all my might.

I'd taken three steps when a stone as big as a man's hand hit me and knocked me on my face, but still I could understand 'em talking.

"You've killed the kid, Slim," says one of 'em.

"Then he's died knowing that I'm his master," says Slim. "But he ain't dead. He's too chuck full of hellfire to die like this. No rock will end him... it will take steel or lead to do his business. Mind me, pals!"

I got my wind back and tried to duck away again. Another rock hit me and dropped me. I come to with water in my face and sat up, asking where I was.

"With your boss," says Slim, leaning over, "and here's my signature."

He showed me his bony fist doubled up hard.

"Leave go of that idea," one of the others says. "How d'you figure in on him more than any of the rest of us?"

"By reason of this," says Slim, and eases a long knife out of his clothes. "Does it talk to you?"

After that, they scattered and there was no more argument. After that, too, I belonged to Slim. I tried for six months to get away from him, but I never could work it. He kept an eye on me all day, and every night he tied my wrist to his wrist with a piece of baling wire. By the time that half year was up, I wouldn't have left him if I could. I'd got used to him and his ways, and I liked the life.

Besides, he learned me a lot. He learned me to sing a lot of songs by heart, playing the tunes to me on his violin. He showed me how to dance the buck and wing, or straight clog dancing. He showed me how to handle a knife so as to take care of myself if anybody else tried to get me. He taught me how to throw it like a stone and sink the point into a tree twenty yards away.

Once I says: "Slim, how come that you work so hard teaching me things?"

He says: "I work for you now... you work for me later on."

And I did. After that first six months, when he found out that he could trust me away from him because I was sure to come back, Slim never raised his hand. I used to knock at doors and ask for hand-outs. Mostly the womenfolk used to fetch me inside and set me down at a table and give me three times as much as I could put inside me, so I'd take it to Slim in my pockets.

Sometimes they got real interested and tried to adopt me. They'd wash me clean, dress me clean and new, give me a name like Cecil, or Charles, or Robert, or some other sort of fancy name like that, that a dog wouldn't have taken and kept. They'd put me to sleep in a fine bed covered with cool sheets. They'd come in and kiss me good night and cry over me; but in the middle of the night I'd come awake when a railroad train whistled for the stop, or because I felt the weight of the ceiling above my face, or because I choked with the smell of cooking and other folks that hangs around inside of any home.

Slim used to say that nothing this side of a good, first-class murder and then a ghost could clean a house of that smell of being lived in. I asked the judge about it. He said that Slim was just smart enough to be mean, that the first half of most of the things he said was right, and the second half was sure to be wrong. This shows how close the judge could figure things. I never knew him to go wrong.

Me, speaking personal, I never could make up my mind, but when I woke up like that in the middle of the night, the first thing I used to think about was the open sky. The second was a picture of Slim over a fire, cooking, and the smell of the mulligan. So I'd slide out of bed, dress up in my new clothes, and duck through the window.

Right here I've got to say that roast chicken, or 'possum and sweet potatoes, or roast young pig, is no better than chewing dead leaves compared to a real mulligan, the kind that Missouri Slim used to cook. He could make a stew out of a tomato skin and an old bone, if he had to, or else he could put in everything you brought.

Once I got into a grocery store on a Saturday night. I brought out one can of almost everything, hot peppers, a chunk of ham, and everything else I could find. It didn't faze Slim. He started the fire, opened the cans, and began putting 'em in and stirring the stuff with a stick. Once in a while he'd taste the goozlum on the end of the stick and then dump in something new. When he got all through, I was almost afraid to taste that mess, but, when I did, it beat anything I ever tasted before and anything I'll ever taste since. It was good.

"What d'you put in to make it so dog-gone good, Slim?" I asks him once.

"Good thoughts, kid," says Slim.

That was his way of talking.

Battering doors for hand-outs was the smallest part of my work. Mostly I kept cash rolling in to Slim. When we hit a good town we hadn't worked before, we'd lay up till evening with Slim playing his fiddle or sleeping, and me hunting around the town, seeing without being seen. I used to ask him how he could sleep so much.

"I'm like a camel, Lew," he used to say. "A camel puts fat on the hump in case it runs out of fodder. I put sleep in my pocket in case I hit hard going."

In the dark of the evening, we'd stroll into that town and Slim would play his fiddle while I danced and passed the hat, or else he'd come in, hobbling on a cane and acting sick, and I'd walk along and sing, with my cap in my hand and everything from nickels to silver dollars dropping into it.

"Keep looking up at the stars, kid," Slim used to say to me, "like you expected to go to heaven along with the next note you sing. The way to make 'em reach deep into their pockets is to put tears in their eyes."

Well, we made enough money to get rich, but Slim used to lose it playing poker, about as fast as it come in. Speaking personal, I liked it best when we wasn't too flush. When the coin was in, we'd lie up and take it easy, maybe a week at a time; when the coin was out, we'd be moving and seeing the sights. We went from New York to Frisco and from Montreal to El Paso during the five years I was with Slim. Then Slim began to drink pretty hard, and, when he started hitting up the moonshine, I knew it was time for me to shake loose. I begun to wait for my time.

That same winter a shack pulled us out from under a car where we was riding the rods. He basted Slim in the face with his lantern and kicked me off the grade. When the train rolled along, Slim used up the last of his cuss words, and then started groaning and holding his nose, where the rim of the lantern had landed.

"What d'you make of a man like that shack?" he says. "One that hits a man when he ain't expecting it? Ain't it low, Lew? That shack is so low he could crawl right under the belly of a snake!"

I didn't hear him. It was a mighty cold night. We'd been near to freezing on the rods, and now we seen the mountains walking up into the sky all around us and the wind come scooping down with the feel of the snow in its fingertips. A wolf began to yell on the inside edge of the skyline, and my stomach shriveled up as small as a dime.

"It don't make no difference to you," Slim says to me. "Poor old Slim that taught you all you know and worked for you and slaved for you! Now he's down and sick and weak and getting old, and you laugh when you see him hurt!"

That was the way Slim used to carry on. I knew he'd made a good thing out of me, but sometimes I couldn't keep the tears out of my eyes when he told me how I'd abused him. Well, after a while, he got out his flask of homemade whisky, so strong it would peel the varnish off of a table. He poured some of that down his throat, and then we started out to find a shelter against the wind. We had luck right away.

When we curved around the side of the hill, we could see the lights of a town in the hollow underneath, and, when we aimed straight for it, we ran plumb into a jungle as neat and as comfortable as any you ever seen, with a fine lay of boilers and tins handy, plenty of dead wood, trees so thick that they was like the roof of a house, and three hobos lying around a dead fire, sleeping warm and snoring—which showed that they'd been living fat.

IT was coming to the gray of the morning. The sky was beginning to show through the trees, and the mountains was turning black in the middle of the night, when we heard a rooster crowing on the inside rim of the skyline, and then other roosters answering the way they do.

"Do something for your country," says Slim. "Here I am, a poor, weak, old man"—he wasn't a year more than forty—"and you stand around and wait for me to starve. Ain't you got no shame in you, Lew?"

I left the jungle after I'd boiled a cup of coffee and ate a chunk of stale punk. Then I cut across to the town. I come out of the woods in the rose of the morning, and there was a neat little town with a white roof of snow on every house.

A mighty comfortable-looking town, I thought it was, as pretty as I ever seen. It sat down in the arms of the mountains with evergreen forests walking up away from it and a creek talking and shining through the middle of it. I seen a boy about my own age delivering milk, driving his wagon down the street, jumping off every minute to leave a bottle, coming back slapping his hands together to keep 'em warm. But there he was all wrapped up so thick with clothes that he could hardly move, and here I was with not even an overcoat.

You see, when you're laid out on the rods and let a winter wind comb through you for three or four hours at a stretch, there ain't anything else in the world that can really make you feel cold. I felt all snug and comfortable when I looked down at the town. I listened to the bells on the milk wagon go out, then I started for breakfast. The hobos I seen in the jungle had a lot of punk and other fixings; all we needed was meat, and there was meat asking to be taken.

I slid into a chicken yard and watched 'em prance around. I'll tell you how to catch chickens. Just go and sit down in their yard and wait. A chicken is the most fool of anything in the world. Pretty soon they come to have a look at you and a peck at you. Then nab one in each hand. You can always tell the fat ones. They're the busiest. The reason they're fat is because they work harder for bugs and worms and seeds, and the harder they work, the fatter they get.

If you're in doubt, don't feel the breast of a chicken to see if it's fat because the last place where they put on fat is the back. When a chicken is nice and round and soft in the back, you know that you got a good bird; if she's full of bones and ridges under the wings, you know you got little to chew. I grabbed a couple of beauties and went back into the trees, where I wrung their necks and then snagged 'em on a branch.

While I waited there, I heard a door open and a screen slam. Then I seen a woman come out on the back porch and call across to the next house: "Hello, Missus Treat! Oh, hello!"

Mrs. Treat shoved up a window and tried to lean out, but she was too fat to get her shoulders through. "Are you up so early, Fannie?" says she.

Evidently Fannie was.

"Was there ever a time," says Fannie, "when I wasn't up as early as you? Besides, this is the day before Christmas, and I guess womenfolk can't afford to sleep on such days."

"Not on days of festivity and merrymaking like Christmas," says Mrs. Treat. "We got to work while the menfolks sit by and fill up fat."

"We got happy lives," says Fannie. "We watch the sick, we hear the babies, we take care of the houses, and, when the big softies are blue, we got to smile and cheer 'em up. I can stand everything but the having to smile!"

She looked like smiling was a real trial, too. But Mrs. Treat, she just kept smiling and chuckling and bubbling all the time.

"Men are silly dears," she says. "You take everything hard, Fannie!"

I picked up the chickens and went off toward the jungle, because I knew that when a pair of womenfolk begin to get sorry for each other, they talk foolish for a long time. In the jungle, I found everybody up and awake. The three 'bos was still yawning and rubbing the sleep out of their faces while they fed up the fire, but Slim was real neat. He's gone to the creek and washed. His hands was reasonable white up to the wrists, and the front of his face was clean, but his neck and ears was never bothered by being wet except it rained on 'em.

As for baths, Missouri Slim never troubled much about 'em. He used to say that they was bad, because they took all the protection away from the skin. "Look at a dog or a horse," Slim would say. "Ain't they got something on over the skin? Same way with a man. He needs protection." There was no use arguing with Slim about a thing like that. He'd made up his mind for good and ever. Baths were not for him.

The hobos took the chickens and began to work on 'em, while Slim sat by and told 'em what to do. He'd brought in the meat supply, through me, and so he didn't have to work with his hands. They started a mulligan, while I rustled more wood, but when the stew was simmering, I asked my question, because it had been riding me for a long while back, ever since hearing the two women talking.

I says to Missouri Slim: "What's Christmas, Slim?"

Slim stopped stirring the mulligan, took another drink of his moonshine, and then corked the bottle, and put it up—all before he started answering me. Then he called to the other hobos.

"Look here," says Slim. "Here's ignorance, for you. Here's what the kids are growin' up to these days. Smart lookin', but they don't know nothing. No eddication. No refinement. No manners, by gosh! Here's a sample of 'em. Would you guess it? He wants to know what Christmas is!"

They all sat around and laughed at me. I could have knifed 'em all and enjoyed it, but I rolled me another cigarette and cussed 'em good and hearty. There is ways and ways of swearing. I knew a 'bo that had been a longshoreman. He could talk a bit. I knew another that used to be a muleskinner, and he could talk a lot more. But for taking a gent's hide off with cuss words, there was never anybody like Missouri Slim, because he sat back and thought things over and picked out words that meant something. With a knife or with his tongue he was a champeen, but he wasn't much good in any other kind of a fight. I'd laid by and studied the way he done it, and after a while, practicing to myself, I learned how to out-cuss even Missouri Slim himself. I'd got so's I could make the toughest 'bo that ever done a stretch foam and tear and rage when I cussed him. I've had a 'bo sit under a tree for thirty-six hours waiting to get me. Well, I talked right back to these three until I had 'em ready to fight. They stopped laughin' and showed their yellow teeth.

"Christmas," Missouri Slim says finally "is the day when folks get things without having to pay for 'em."

"Why," says I, "every day must be Christmas for you, then."

Missouri shied a rock at my head. He could throw a stone like a snake strikes—that quick. But I'd learned to dodge even quicker. The stone sailed by.

"What is Christmas?" I asks them all.

"Go and find out!" all four tells me.

They wouldn't say any more. Through breakfast, Slim kept saying how hard he took it that, after all the hard work he'd put in teaching me, I didn't even know what Christmas was. He said that I was a trial and a shame to him.

I didn't listen. I just ate my share of the chuck, smoked my cigarette, and then curled up near the fire to have a snooze. The last thing I heard was Slim telling the other 'bos to keep shut of me while I was sleeping, because if I was waked up quick, I got my knife out before my eyes was open. Slim had taught me that, if he hadn't taught me about Christmas.

When I slept, I had a dream that I had a fine black horse brought to me, all saddled and bridled, and that when I whistled, he came up and nuzzled my hand. I'd always wanted a horse. I used to beg Slim to get me one, but he used to point to the steel rails of the track and say: "There's our horse, kid, and it'll step faster than any four-legged horse in the world!" This dream made me so happy that I called out: "What's the name of this horse?" And a voice sang out in the air over me: "Christmas!"

I woke up. The four tramps was sitting around, grinning at me. So I knew that I'd shouted that last word out loud. I told Slim I was going for a walk and started off through the woods, but what I was really doing was hunting for Christmas. It made me feel like a fool to be laughed at by four 'bos. Aunt Maria had never taken a holiday or given me one or had any festivity at this time of the year, and with Dad and then with Missouri Slim, every day was a holiday. That was how I happened to miss knowing. I went back to the edge of the town and laid low.

Pretty soon a couple of boys came out into the back yard of a big house. I climbed up and sat on the edge of the fence.

"Hello," says one of them, "what are you doing up there?"

"Sitting on the fence," says I.

They frowned and looked at each other. They were a shade older than me, and heavier. I could see them sizing me up.

"That's our fence," says the biggest of the two. "You got no right to it."

"I'm just borrowing it," I tells 'em.

They begun to sidle up to me, talking all the time. I acted like I didn't notice.

"What you looking for?" they asks me.

"Christmas," I says.

They stopped and begun to laugh.

"What's funny about Christmas?" I asks 'em.

"D'you believe in Santa Claus?" says one of 'em.

I'd never heard that name before. I hedged. "Partly I do and partly I don't," I says.

They laughed again. "He doesn't know much, Tommy," says one of the two, "Where'd you come from, boy?"

"Yonder," says I, and waves to the sky.

"Who's your father?"

"The sheriff," says I.

"That's a lie," says Tommy. "Pete Saunders's dad is the sheriff. Who are you?"

Asking wasn't good enough. Tommy made a dive and caught my feet. As he pulled one down, the other one grabbed me around the neck.

"We've got him!" they yells, and they begun to pommel me.

It was all a cinch. When I laid hold on 'em, my fingers sunk way into them, they was so soft. I hit Tommy in the stomach, and he rolled on the ground, gasping. I got a half-nelson, that the Denver yegg, Tom Larkin, showed me how to use, and rolled Charlie on his back. Then I tapped him on the nose until he hollered quits. When I got up, Tommy was coming again, like a bull. I hit him on the jaw so hard it made my shoulder ache, and he dropped on his face and lay without a wiggle. It was good fun. I wiped that blood from Charlie's nose on my pants. When I looked up, a fine-looking man was standing in the yard with his hands on his hips, looking me over.

"Cheese it," I says to myself. "Here's where I get the boss licking of my life!"

"UNCLE JOHN, Uncle John!" yells Tommy. "Help! Help!"

I looked at the fence. It was higher from the inside than from the outside, and I saw that there wasn't a chance for me to go over it. Then I looked at the man. He was about thirty-five, but he had no more stomach than a greyhound, and by his way of standing I knew that he could run like one. So I made up my mind that I wouldn't try to run away. A boy is a fool to run if he can help it. When you're caught after running, you get three licks for every one you would have got before. I leaned against a tree and rolled a cigarette and waited to take what was coming.

The big man didn't seem in a hurry. He give me a look, and then he gave Tom and Charlie a look apiece. He didn't seem no ways satisfied.

"There's two of you, and there's one of him," says he. "Am I right?"

"He... he...," Charlie begun.

"Be quiet," says the big man in a way that made 'em both stand stiff and still. He goes on: "Did I see you two fighting that one boy... two on one?"

They didn't have nothin' to say. Me, I blinked at him and couldn't savvy what he was driving at.

"'S'all right," says I. "They didn't do me no harm... just scratched me up a bit."

"Listen to me, boys," says the uncle, "if this were not the day before Christmas, I'd make you remember this as long as you live. And if I ever again hear of you combining against another boy of your own age and size... by jingo...," he busts out, "I do believe that both of you are bigger than this little chap!"

It made me mad. I never gave promise of growing up to and past the six feet that Dad promised me when I was a little kid, but it always rubbed me the wrong way to have folks point it out. I stood up as big as I could stand.

"I ain't so small, mister," says I. "And them two... huh, they ain't nothing. If they was twice as big, I could eat 'em!"

I'd got the cigarette going pretty good, and then I steps up and blows it in their faces, but even that didn't make 'em fight. They'd had plenty.

"I think I understand," says the big man to himself more than to the rest of us. "I think I understand."

He hitches up his shoulders and drops his hands on his hips.

I thinks to myself: If he don't pack a wallop in each mitt, may I never grow up to he blowed in the glass. Hope he don't take his exercise on me today.

He hooked his thumb over his shoulder. "Go inside, boys," he says.

They went hopping; pretty soon they come to the back windows and must've frosted their noses looking out to watch me get my hiding. But the big guy didn't seem in no special hurry.

"Is that tobacco?" he says to me.

I told him it was and waited for him to start a lecture, like the rest. It's a queer thing that folks that's growed up can't leave a boy alone. They got to give advice. But the big guy was different.

"Lend me the makings, will you?" he asks me.

I handed them over. He rolled the pill with one hand; it was mighty slick work. I asked him how long it had taken him to learn, and he said that he got the trick of it when he was punching cows on the range. He didn't look like a 'puncher. He stood too light on his feet, and he wasn't brown enough, and he didn't have the wrinkles around the corners of his eyes. I told him that I was surprised.

"What would you make of me?" he says.

"Why, a banker." Then I had another idea, because of the way he looked straight into me and made me blink. "Or a sheriff," I says.

At that he started a little and let the match go out between his fingers without lighting his cigarette. "Why is that?"

"Because you look at a feller like he had a gun hid in his pocket," I tells him.

He managed to light his cigarette this time, and he grinned at me through the smoke. "You made a close guess, son," he says. "But I'm not the sheriff... I'm only the judge."

"Oh!" I says, and took another look at the size of that fence. It was bigger than ever!

He was a judge, and, of course, they're even worse than sheriffs. I started backing away.

"How long have you been smoking?" he asks me.

"Four or five years," I says. "Is that wrong?"

"Wrong?" he says, and cocks his head to one side like he was considering it. "Certainly not. If you wish to smoke, why shouldn't you? It's a comfort, isn't it, after a hard day's work?"

"It sure is," says I, and took a long breath, seeing that he wasn't one of them lecturers. For a square guy, the judge was a bird. He had the world stopped.

"I suppose that you're traveling through?" says the judge.

"Yep."

"With your dad?"

"Nope."

"Older brother?"

"I play my own hand," says I.

He took another breath of smoke and blew it out in rings. "Been playing your own hand for long?"

"About five years."

He whistled.

"What's wrong," says I.

"A touch of rheumatism," says he. "I got an old bullet lying up in me, and once in a while it gives me a reminder that it's there."

"A bullet?" I says.

"Yep

"Somebody plugged you once?"

"A pair of crooks started out to get me," says the judge.

"A pair of 'em? What kind?"

"Yeggs," he says. "I gave one of their pals a long sentence. A fiver, if you know what that means."

"Listen, was I born yesterday? Sure, I know that lingo. I used to pal around with Sammy Mobile. Well, you're lucky if you got out with only one chunk of lead in you if there was two yeggs after you. Did they corner you?" I stopped, anxious for him.

"They got me from behind," says the judge.

"Behind! Shot you down and men flagged it?"

"No, they ran to finish me."

"Jiminy!" says I, beginning to think that he was maybe just a ghost. "What happened then?"

"I finished them, instead."

"While you was lyin' on the ground?"

"I got the drop on 'em. The ground steadied my arm."

"Oh," says I, running out of any words that meant anything. "Who was that pair?"

"Tinman and..."

"Tinman! He's the bum that pulled the stunt at Jericho!"

"You know about that?" says the judge.

"Sure, I knew about it."

"Oh, Tinman's dead. I guess there ain't any harm in talking about it now!"

"Not a bit."

"Is it straight that he killed both the old folks?"

"Yep, he croaked the two of 'em," says I, sort of proud that I could tell a gent like the judge anything. "He spent the day in the cellar and come up through the trap door that night when they was asleep. He told us about it afterward. You got Tinman, eh? Who was the other one?"

"Lefty Peters."

"Peters!" repeats I. "The one that killed..."

"He had a long record," says the judge.

I begun to get some new angles on the judge. Peters and Tinman was so dog-gone bad that even the rest of the yeggs steered clear of them. They ran together because nobody else would play in with 'em. Their way of cracking a safe was to start making things safe by murdering the watchman. A killer ain't popular even among hobos. The getting of either one of 'em was enough to make a reputation for a whole posse, but for one man to get the two of 'em after they'd tackled him behind and dropped him was pretty near too much to believe. I begun to understand why the judge's eye was so straight. He needed a straight eye.

"Well," says I, "I'm mighty glad that I met you, Judge! I didn't even know that Tinman and Peters was dead."

"Neither did I until a month ago. It was a year back that I tackled them, but only the other day I turned up some evidence that established their identity. Did you know Peters, too?" He looked at me, interested.

"Did I? He nearly knifed me once, because he stumbled over me when he was drunk."

"Ah?" says the judge. "How did you get away?"

"Threw a handful of sand in his face and blinded him."

"Hmm!" says the judge. "You seem to be able to take care of yourself."

"A traveling man has to learn how to do that."

The judge coughed. "You ran away from home, I suppose?"

"I suppose not," says I. "Mother and Dad were dead... Aunt Maria gave me a job, not a home."

He laughed. He had a fine laugh that come clear from his stomach. When a man laughs up in his chest, you know he's no good. That's the way a woman laughs. Speaking of women... but the judge says it's better not to speak of 'em. I'll let that go.

"Where are you bound this morning?" he asks.

"I was just collecting some dope," says I.

"What?"

"Just talking."

"With my nephews, eh?"

"Yes."

"Did they tell you what you want to know?"

"They laughed at me."

"That's why you fought?"

"Nope... it takes more than a laugh to make me fight. I ain't proud," I explains to him.

"Oh, well, what was it you wanted to know?"

I didn't want to tell him. Being laughed at by the kids wasn't so bad, but I figured that it would hurt if the judge laughed, too.

"Why," says I, "it was nothing much, I guess. It was about... er... about Christmas."

"Ah, yes. What about it?"

I doubled up my hands and looked him square in the eye. "Well, what is Christmas?"

The judge looked at me a minute like I'd hit him. Then he stepped over quick.

He's going to laugh, too, says I to myself.

But he only picked up a stone and chucked it at the fence. There wasn't no sign of even a smile when he looked up again.

"What is Christmas?" says the judge, sort of to himself. "You never had it explained?"

"Never put in time in a school," says I, feeling mighty awkward with my hands and my feet when I said it.

"Oh," says the judge. He seemed to be thinking of something else. Finally he says: "Most people don't have to go to school to learn what it is, you know." Then he busts out with a frown, getting a little red: "it's the birthday of Christ, my friend."

He had me floored again, but I was too foxy to let him know it. I'd heard that name used for the inside lining of some fancy swearing, but in no other connection.

"Oh," says I, "is that all?"

"Is that all?" says he, speaking sort of quick, as though I'd pinched his watch. Isn't that enough?"

"Don't get sore," says I.

He give his chin a rub and stared at me. It looked like I was getting deeper with everything I said. I offered him the makings of another cigarette, but he didn't seem to see or hear me. His mind was on something else.

"Do you know when Christ was born?" he asks me.

I had a quick think, then I took a chance. "Sure," says I. "Before the war?"

THE judge begun to walk up and down the yard, kicking stones out of his way. I seen that I'd answered wrong.

"If he was a friend of yours...," I starts.

He cuts me off short. "Boy, boy! He was born more than nineteen hundred years ago!"

What a boob I'd been as a guesser. The judge waited a little longer: "What's your name?" he asks.

I would have said John Smith, or something like that, but he popped it out at me so quick, that I told the truth before I thought.

"Lew Maloney."

"Lew," says he, "d'you know nothing more about Christmas than this?"

"No," says I.

The judge stopped walking around. "I won't try to tell you all about Him now, only this... that He gave His life for the rest of us. A terrible death, Lew. You can understand that much of it. They stretched Him on a cross of wood, and they drove nails through his hands to hold Him up, and a spike through His two feet. He died by inches, for the sake of other men."

I tried to think of a man dying like that. It took my breath and made me sick.

"That's why," says the judge, "we keep Christmas every year. He gave so much for us that on this Christmas day, we give little things to one another to help us to think about what a good man, what a brave man, what a generous man He was... because He gave his life, do you see?"

"It's the finest thing I ever heard of," says I, and I felt it. It gave me a queer tingle clear down to the toes. It made every man I'd ever seen or heard of seem mighty small. "Was this here Santa Claus some relation of His?"

The judge bit his lip-to keep from saying something or to keep from smiling. I couldn't figure which.

"Ah," says he, "Santa Claus is another story. I was saying that we give things to one another... but Santa Claus is an old man who gives things to everybody!"

I thought about this for a while. "Judge, excuse me for contradicting, but you're wrong there. He never gave me nothing."

"Of course not. Because you never asked him to."

That floored me.

"Look here," I says, "d'you mean to say that, just for the asking, he gives things away?"

"Exactly that."

"It ain't nacheral," says I. "I got to have that proved, Judge."

"Didn't you, just now," says the judge, "give me a cigarette simply because I asked for it?"

"That's different," says I. "What's a cigarette?"

"Well," says the judge, "Santa Claus gives away things just like that."

"What's his plant?"

"What do you mean?"

"What's his scheme? What's his layout? What does he look like?"

"I can tell you. He's a very old man with a long white beard and long mustaches. Usually he wears a red coat trimmed with white fur, and a tall hat of the same red cloth and white fur. He has thick gloves on his hands, and his trousers are wrapped around his legs with cord to keep him warm, because he rides around in the cold air, drawn by reindeer..."

"Wait! Wait!" I says. "Did you say he drove around in the air?"

"Exactly. He has a big sleigh loaded with gifts. When he comes to a house where he intends to leave presents, he stops the sleigh on the roof and comes down into the house through a window, or even by a chimney..."

"Hold on, Judge," says I. "D'you expect me to swallow that? Driving through the air... stopping on the roof? Whoever heard of anything like that?"

"Why not?"

"Not even a feather can ride in the air very long!"

"Lots of strange things can happen in this world," says the judge. "Is Santa Claus and his rides through the air any harder to understand than a telephone?"

"Why, a telephone is easy!" I tells him.

"What is it, then?"

"Why, you know! Some wire, with electricity in it, and..."

"But what's electricity?"

It stumped me. I tried to think it out, but then I gave it up. "I don't know," I admits. After a minute I went along: "Are you handing this to me straight, Judge?"

"This very night!" says the judge.

I watched him mighty close, but he kept a straight face. He was serious all the time.

"Such as what?" I asks.

"Whatever you want."

"Suppose I asked him for a pair of shoes?"

"You'd get 'em. Think of something more. Tell Santa Claus the thing you want most in the world. He'll get it for you, if you really are willing to believe in him."

It made me sort of dizzy. I leaned against a tree and blinked.

"Suppose," says I, talking slow and watching the judge to see if he was about to smile and give the game away, "suppose that I was to ask him for a .32 six-shooter? One of them straight-shooting little guns that can't miss hardly. I suppose you mean to tell me that he'd give me even that?"

"You want a gun, eh?"

"Want it?" It choked me, thinking how bad I wanted that gun.

"Well," says the judge, "all you have to do is to write that out in a letter to Santa Claus..."

"I knew there was a catch," I says, and it made me sick inside. "Yep, I knew there was a catch!"

"Where's the catch?"

"You see, Judge, I never put in no time at school. Aunt Maria tried to teach me, but I... I never learned to write."

The judge kicked another stone that rolled clean to the fence. He seemed madder than ever. Then he thought about it, but, after a while, he told me that the thing might still be managed. He said that Santa Claus was a simple-minded guy, so old he was getting childish. If somebody else wrote down that letter for me and signed my name to it, he'd probably never notice that it wasn't my handwriting.

He offered to do the writing for me, pulled a piece of paper and a pencil out of his pocket, and asked me what I wanted to say. I told him I thought it ought to start out with his name and address, so's it would get to him. The judge allowed that was a slick idea. He wrote it down and read it to me: "Mister Santa Claus, Greenland, Northern Hemisphere."

It sounded pretty fine. I told him what to say, and he wrote the letter.

Dear Mr. Santa Claus: It ain't likely that you know me, but, if you'll give me a look tonight, I'll be glad to see you. And when you come, if you happen to have any old .32 caliber six-shooters on hand, I could sure use one. I mean the kind that the Denver Kid was packing the last time I seen him. It's about the right weight for me. I'd be mighty obliged.

Yours very truly,

Lew Maloney

I told the judge that Santa Claus might not see his way to giving as much as that to a stranger. The judge said he thought Santa wouldn't mind, but he said that I'd have to be in a house, because Santa didn't stop his sleigh except on a roof. I was stumped by this, but the judge said that I could come around to his house that night and wait for Santa Claus there.

It all sounded pretty spooky, but the judge seemed to take it pretty serious, so my hopes begun to rise. We added this to the letter:

You'll find me at the judge's house. If you don't want to give me the gun, I'd be glad to just have the loan of it.

I asked the judge if that was enough of an address for Santa Claus to find me by, and he said it was, because when he was a kid, the old man used to visit him regular, every Christmas. After that, I said I'd mail the letter, but the judge said that wasn't the way. He picked out a match and lighted the paper and watched it burn up to a crisp. Then a breath of wind came and floated the ash of the paper up till it was out of sight. The judge watched it sail away.

"Everything that burns up, Santa Claus reads," he says.

"Even old newspapers?" says I.

"Of course," says the judge. "That's how he keeps so well posted on things that are going on."

It was queer, any way you looked at it, but it was the judge that led me on. I couldn't help believing him.

"This here Christmas must be a happy time, then," I says.

The judge allowed that it was, for most folks.

"But you act like you had your coin on the wrong horse," I tells him. "Ain't you wrote a letter to the old boy?"

The judge pulled in a long breath. "There's only one thing in the world that I want," he says. "And Santa Claus can't help me."

"Something too heavy for his sled?" I asks.

The judge grinned. "Santa Claus is a bachelor," he says. "He doesn't keep any women in stock."

That took me back a lot. I got to admit that I lost half of my faith in the judge right then and there. I'd seen old women and young ones, but I never yet seen one that amounted to nothing. Between you and me, what's a woman good for? She can't run faster'n a little kid. She can't climb a tree, even, or throw a stone twenty yards. I've seen 'em jump on chairs and squeal when a mouse come into a room. That's a fact! The only use I ever had for 'em was to work 'em for a hand-out, and that was always a cinch. And here was the judge talking about wanting one of them!

"Judge," says I, "I dunno what you want with one. Here's a guy that'll give you a gun if you ask for it, but still you want to waste time asking him for a... well, it beats me, that's all. What's the good of 'em?"

"I'll tell you how it is," says the judge. "I agree with you about all the girls in the world, except one. The rest of them aren't worth a snap of your fingers. They're silly. They're weak. They talk too much. They're nothing that a man wants to have around him. But between you and me, there's just one girl that I could be happy to have."

"What would you do with her?" says I.

The judge put his hand to his throat and pulled his collar a little looser. "I'd use her to warm my heart, boy," he says real slow-like. "I'd take her inside my life and use her to warm my heart the rest of my days. I'd cherish her like a bird come in out of a storm. I'd put her where I could look at her, because just the lifting of her hand, or the turning of her head, or the least word she speaks, or even the memory of her smile is enough to stop your heart! Roll together everything you could wish... a gun, a horse, a dog, a house, a million dollars to spend… and still all of that wouldn't make up the price of one of her smiles!"

He said it all in a way that put a shiver in me. I couldn't find no ways to say what I felt. I felt that there was things in the judge that would never be in me. It was like seeing mountains and wondering what was on the other side of 'em. Then he gave himself a shake and managed to smile down at me.

"Come tonight, Lew," he says to me. "Come tonight. About this girl talk," he went on, "heaven knows why I said what I have said! But it's between you and me."

"Partner," says I, "it's buried. I've forgot what I heard you say."

We shook hands, and the judge went back toward the house, walking like an old man with his head sunk and his back bowed. I stood there watching him go, and I felt as though I wanted to die for him.

I WENT back to the jungle with the wind beginning to yell and tear. When I got there, I found Missouri Slim, but the three other hobos were gone. Instead, there was a little, square-set man and a tall, skinny one, leaning together over the fire and talking very soft and fast. They both looked like old-timers, and I knew that there was business in the air.

After a while, I found out that these were two-hundred-percent yeggs. The sawed-off guy was Whitey Legrange. The tall one was an old second-story man that had turned safe-cracker; his name was Murphy, but they called him Skinny. He'd just done a stretch, and his hair was still short and stuck out like bristles all over his head. He had the prison look, too, and the prison way of talking fast and soft out of the side of his mouth. It was enough to give you the shivers to watch him.

They'd planned a job for that night in the town, and they'd run the three other hobos out of the jungle because they wanted to be alone to talk things over with Missouri Slim. They had some sticks of powder along with 'em, and after a while they begun to cook them to make soup. After it was ready, they poured it into a flask, so I knew it was a job of blowing a safe. They had their doubts about me, at first.

"What about the kid?" says Whitey.

"He'll do," says Missouri.

Skinny caught me by the collar and dragged me around in front of him. He looked at me with his rat eyes.

"Kid," says he, "d'you know what happens to anybody that blows a game on me? I cut their livers out and feed 'em to a dog! That's me!"

"Lay off the kid," says Missouri. "I tell you, I know him for five years. He's got a head like a man on his shoulders. He could work the outside for you, if you want."

"There ain't any call for an outside man," says Legrange. "But if the kid is handy, let's see what he can do. We need some chuck. I haven't had a real square for two days. We need some yellow laundry soap, too. Can the kid get the stuff for us?"

"You hear what's wanted," says Missouri to me. "Go try your hand. I'll give you an hour. Mind you, Lew, if you ain't back with the stuff inside of an hour, I'll give you a tanning you'll never forget!"

I went back to the town. It would have been dead easy to batter doors and beg the stuff. Along about the time it's getting really cold, folks hand out pretty near anything you want to ask them for; but I didn't have the nerve to try the doors, because the judge or one of his nephews might've seen me. I snooped around until I located the grocery store, and I sneaked up to it through the back yard. I worked back the catch on a window with a bit of hooked wire, slid inside, and grabbed what was wanted. I took an old flour sack and dumped in enough chuck to feed twenty men. Then I put in a few bars of yellow soap, got back through the window, closed it, and even locked it again behind me.

When I got back to the jungle, Whitey snapped his watch shut.

"Forty minutes," says Whitey. "I guess this kid will do!"

Slim was the cook. We laid around and ate a big meal. Then everybody turned in, and we slept, or tried to sleep, but it was hard to do because the wind was thickening up with snow now, and the flakes come whistling through the trees and stung when they landed. We moved the fire close to a shelter, but, when we got near it, the smoke choked us, and, when we got away from the smoke, we started freezing. They kept nursing the flask of nitroglycerin all the time, seeing that it didn't get cold, because when the soap gets cold it just explodes-and there's an end to you and your troubles!

After a while, we gave up trying to sleep. The wind was acting crazy, tearing at the trees, poking at us like fingers of ice, and roaring and shouting through the woods. They begun to tell yarns about what they'd done. Missouri Slim led off with some man-sized lies about his fights.

Take him by and large, Missouri was the biggest liar that I ever listened to. He was the best and the safest, too. He always started with facts and then changed 'em a little and then a little more. He talked like he was being cross-examined by a flatty. He gave all the little details, so's you could have sworn that he was telling the truth. He'd start out like this: "I recollect back in the Big Noise when I met up with Sam Juisinsky. That was when he was wanted for killing the copper out in the Bronx. I was over on the west side, walking down Tenth Avenue with Joe Bertran and Ollie McNear. It was one of them thick, hot nights when you could hardly breathe. There was faces up in the windows. There was kids trying to play in the streets, throwing water at each other, and a crip on the corner was playing 'Sally' on his fiddle. 'Look there!' says Ollie. 'Damned if that ain't Juisinsky!'"

That's the way Missouri told a lie. He took his time about it, and it was mighty fine to hear him talk, even when I knew that he was lying every minute. After he finished his yarn, the other two took their turn. They didn't lie. They didn't have to—they'd both done things that might have been in a book.

Skinny told how he cleaned out the upstairs of a house while a wedding was going on downstairs. Whitey told how the detective, Marks, trailed him for five months and followed him clean to Australia and back; and how he and Marks met up in a joint and had it out with their bare hands, because neither of them happened to have a gun handy. He killed Marks in that fight, and, when he'd finished telling about it, I was sick and pretty weak.

It was getting dark now, and the three didn't plan to go ahead with their work until quite a while later.

"When everybody in town is full of turkey," they says, "and when they're pretty sleepy, then we'll come and get ours!"

But I was thinking about Christmas and Santa Claus and the judge. I told 'em that I would meet 'em wherever they said and whenever they wanted, and it turned out lucky enough that they was going to meet in a barn right next to the judge's house.

When I got back to the judge's house, my nerve begun to get weak on me. The place looked mighty big and black to me. I went around, trying to work up my nerve. The back yard was as big as a building lot, but that wasn't a patch on the size of the rest of the grounds. He had great big trees everywhere; there was stretches of level that must have been lawn, although the snow was all packed and crusted over it, mighty thick. There was a pool with a statue of a lady in the middle of it, with the snow piled upon her head till it looked like a mass of white hair. There was rows of big trees and little ones. There was acres and acres of grounds, with a driveway winding around through 'em up to the house. The more I seen of the place, the more sicker I got about going up to the door and telling them that I'd come to see the judge.

I went back and had another look at the house. How any one family could use a place as big as that beat me. It might've done for a hotel, pretty handy. I shinnied up a drainpipe from the eaves and got to a big window with the shade down on the inside, but through a crack to the side I could see slits of what was inside.

There was a whole fir tree standing in there covered with shining stuff like snow, but brighter than snow. There were strings of colored lights that throwed patches of red and green and blue and yellow on the ceiling. There were things that looked like rubies and emeralds and diamonds dripping from the branches. But that wasn't all. The whole room was strung around with twists and streamers of green stuff, and there were fir boughs and pine boughs standing in the corners. I could guess that that room smelled pretty slick, and somehow I knew that this was the place that was got ready for Santa Claus to come to.

You've no idea how much nearer I seemed to be to that gun I wanted after I seen the room. Still it seemed like it would be pretty hard to go into a place like that dressed the way that I was dressed. I would've give an eye for a new suit of clothes before I had to show my face.

After that, I sneaked back to the ground and took a look up at the roof. It wasn't hard to see everything. The last of the day was gone out of the west, but it was a clear night. The snow had stopped falling. There was too dog-gone much wind for any clouds to be in the sky. Every star was shining, looking so cold you wouldn't believe it. I could see the snow on the roof, heaped up thick, with a shining line along the top and blue shadows along the sides. Somehow, it didn't seem hard to believe now that Santa Clause could drive through the air with a sleigh and reindeer. I begun to strain my eyes with watching, expecting to hear the bells jingle and see the horns of the deer tossing. I figured that he'd stop the sleigh right where the roof branched out on two sides and made a cross.

That would give a support for the runners.

I was thinking this all out, when I seen something move along beside the hedge that fenced in the path near the house. Then a figure stepped out and went up toward the house. I followed it quick, because by the way it moved I knowed that it was a sneak of some kind. You can tell when anything is hunting—anything from a cat to a man.

When I got up close and had this here shadow between me and one of the windows of the house, I seen that it was a woman. She was all dressed up in a long fur coat with a great big collar that was folded up over her head and a big fur muff to keep her hands warm. I could tell by the hang of the coat that it was a woman. A man's coat slants in at the bottom because his shoulders are so broad; a girl's coat fans out.

I dropped behind a bush and let a handful of snow slide down my neck without stirring an inch. I was curious now. By the way she was moving, I figured that she was after some sort of loot, but when I seen that coat, I had to change my mind. It was the kind of a fur that you see the ladies stop outside of windows to look it. The wind kept ruffling it around, swinging it into folds and out again, and, when the light from a window hit it, it slid over the arm of that coat or over the hood, like oil over water. It was the kind of fur that the wind parts so's you can look way down into it, but, no matter how deep you look, you never see the skin, just more hair underneath, short and thick-growing, and fine as silk. It was the kind of fur that Missouri Slim said had no price—it just cost as much as you wanted to pay.

A lady that could afford to wear a coat like that couldn't afford to be a burglar. That was easy to see. But then, what was she doing there? She tried to get high enough to look into a window, couldn't make it, and turned around again. Then I stepped out from behind the bush, and she gave a little squawk when she seen me.

"Tommy!" she gasps, and then turns and starts to run. I got in front of her.

"It ain't Tommy," says I.

She stopped short and out of the shadow that the fur hood made over her face I could feel her eyes watching me. She asked me who I was and what I was doing there, but the best thing I could think of was to ask her the same questions.

"The east-bound train is two hours late," she says, "and I have to wait for it. I simply took a walk through the village to kill time."

"You never was here before?"

"Certainly not," says she.

I might've told her that, if she'd never been there before, she wouldn't have called out—"Tommy!"—but I didn't have the nerve to say it. She had a voice as soft as her fur coat. I never heard nothing like it. The harder I listened to it and the deeper I got into its softness, the more I felt like standing there and begging her just to talk.

The wind had dropped away as quick as the snow had stopped falling; and just as quick as the wind stopped, the cold dropped around us, thick and quiet, and biting through the clothes like teeth.

"And you?" says she. "Why are you here, little boy?"

"I ain't little," says I.

She begun to laugh, and that laugh took the frost out of the air. It was as light and as easy as the sound of water in summer when you lie on the bank and wonder whether it's better to sit up and start fishing, or just to lie still and watch the sky through the leaves and feel the air in your face—and go hungry!

"I'm the watchman for the judge," I says, because I couldn't think of nothing better to say. "He put me out here to keep strangers from busting in."

She laughed again. "You haven't even an overcoat," she says. "You must be stiff with cold! Tell me true, are you... are you waiting here because you're cold and hungry, and because there's so much warmth and light in that house? Is that the reason?"

I seen that there was a chance to make a haul. "Lady," says I, "that's the real reason."

"Poor child!" she says. She fumbled for a minute in her muff. Then she brought out some paper money and give it to me. The hand that touched my hand was as soft as silk and was as warm as a puppy.

"You're mighty kind."

"Merry Christmas to you," says she, and starts to leave.

I tried to stuff the money into my pocket, but my hand couldn't get it inside. "Wait a minute!" I calls after her.

She came back. "Well?"

What happened to me then, I dunno. But something snapped in me so loud that I could almost hear it. It made me sort of dizzy. Before I knew it, I'd made her take back the money and I'd told her that I was a cheat, that I wasn't waiting out there because I was hungry, that I'd just had all the chuck I could swallow, that I'd fooled her, and that I was sorry I done it.

She listened to me and didn't break in till I was done. Then she says: "You're a queer boy. You're a very queer boy. There's fifteen dollars here. Do you really mean that you don't want it?"

That took my wind, of course. Fifteen cold simoleons all for my own, fifteen plunks that even Missouri Slim couldn't never take away from me! Why, it was like being rich all at once. Yet I couldn't quite close my hand on that haul.

You've had that nightmare where you try to run with all your might, but a chill gets into your legs and you can't work 'em? That's the way it was with me. I wanted that money. I could think of twenty ways of spending it. I could figure it up as big as a mountain. A dime would buy a meal, if a guy knew how to spend it right. There was ten dimes in a dollar; but how many dimes there was in fifteen dollars was more than I could work out. Still I couldn't take it, quite.

"When the judge was a kid like me," asks I, "d'you think that he would of took money like this?"

And she cries out: "John take money? Oh, dear, no!"

THAT let the cat out of the bag. She wasn't no traveler coming through, like she said. She was there on purpose. This fitted in with the name she'd called me, taking me for one of the nephews of the judge. She knowed all the folks in that big house. She was one of their own kind. I could tell that by her voice—and by her kindness. Her being silly and being took in by my lies didn't matter very much, seemed like.

I hate a man that's a boob. If he gets trimmed, let him take what's coming to him, but I can't say that I like these here sharp women that can't be beat and that have two hard words and two hard tricks for every one of your own! I never knew it before I talked to this lady, but she opened my eyes. I felt like laughing at her for being so simple, but just the same she tickled something in me by being so silly. I part wanted to laugh and I part wanted to cry, which is mighty queer.

She was trying to explain away what she'd said. "Of course, I mean he wouldn't take money now, because he's a man. But at your age, if he were poor, of course, he'd take it! Why not?"

But I'd heard her the first time, and I told her so.

"And does the judge keep you from doing this?" she asks, very interested. "Are you imitating the judge?"

"Lady," says I, "I'm shy about ninety pounds. If I was that big, though, I'd try to step where he stepped, but he's got a long stride!"

"Does he know that you're his pupil?" she asks me.

"Nope."

"Are you going to try to be like him in every way?" she says.

"If I could," I says, speaking right out from my heart, "I'd be so like him that folks would think that we was brothers!"

"Then you'd have to be very proud."

"Is he proud?" I asks her.

"The very proudest man in the world, the hardest, the sternest, the most unforgiving!" cries she, all in a breath and with her voice shaking.

It made me stare to hear that. "I guess you hate him," says I, feeling mighty sorry for her and also for the judge, them both being fine folks.

"I hate him! Yes," she says, "I do, because I have cause to... oh, what am I saying?"

"I dunno that I would put money on anybody, having real cause to hate the judge," I couldn't help telling her. "What's he done to you?"

"What has he done to you, to make you so fond of him?" she asks right back at me.

"He treated me like I was his age and his size," I explains, trying to figure out just what he had done. "He talked like I could understand easy anything he had to say. He was square as a gun with me. Dog-gone me if I ever met such a man!"

The lady had come a little closer, so's I could see through the dark beneath the hood the shining of her eyes.

"Yes, yes!" she was saying over and over. "Yes, yes! I quite understand. So gentle, so simple, so kind. Dear John. Oh, dear, dear John."

"Lady,"—I was plain flabbergasted by this way of acting—"one minute you call him names... the next minute you say he's the king. What do you mean?"

"I don't know," says she, in a sort of a whisper. "I'm afraid that I don't know, except that he's kind on one day, and hard as stone the next! But tell me, what he has done for you?"

I told her that he'd explained this Christmas business to me, and I told her about this friend of his, Santa Claus, that was calling at this house that night.

At this, she puts her muff up to her face, and I was afraid that she was going to laugh, like other folks, but, when she spoke, she was plumb serious.

"I'm very, very glad that you're to meet Santa Claus," she says. "He's such a kind old man!"

"But sort of queer, ain't he? Think of a guy running around the country giving things away!"

"Have you asked him to bring you something?"

"Yes."

"I do hope that he will," says the lady.

"There ain't much doubt, I guess," I tells her. "The judge said that he was sure to get my letter. The judge wrote it for me, you see. I'm to go into the house and meet Santa Claus there."

"In that case," says she, "I imagine you're right."

I told her I'd been watching the roof to make sure, when he come, I'd be in the house in time, but she said that it might be a good idea not to wait until I saw the sleigh, because sometimes it was hard to make it out. If I didn't hurry, he might come and go before I got into the house. That idea gave me a start.

Then a window or a door was opened, and we heard the tingle of voices laughing inside the house.

"How happy they are!" says she. "How happy everyone in that house is today!"

"Except the judge."

"What do you mean?"

Just what I meant, of course, I couldn't tell her, the judge and me having talked it over private. I was stumped for a minute, then I says: "It don't do him any good to write letters to Santa Claus for himself, because the old gent can't bring what he wants."

"Is there anything in the world that he really wants and can't have?" asks the lady.

"There is."

"I'd give a great deal to know what it is."

"It's between him and me," says I. "You'd never guess, looking at him, what it is that he wants."

"More money," says she.

"You're wrong."

"To be a higher judge, then."

"Still wrong. Seems like you can't guess any more than I could, lady."

"He wants..." She stopped and took in her breath, like you do when you dive into cold water.

"Well?" says I, thinking that she couldn't come any closer.

"He wants a... a wife!"

It made me blink. Who would have thought that she was so smart that she could see right through to the right answer? I begun to think that she was pretty smart or else I was a good deal of a fool, because I'd never been able to guess it.

Then the lady come up close to me. She took me by the shoulders and turned my face into the light that come out from a window where the shade wasn't pulled down.

"Tell me! Tell me!" she says.

"You're right," says I. "Dog-gone if it don't beat me, how you could know it!"

There was a little sapling near her. She leaned against it with her head down, mighty sick.

"It's Alice, then," says she, sort of to herself. She went on after a minute: "He... he's to be married soon?"

"Look here," I says, "I've give him my word of honor that I wouldn't tell a soul what he told me. Here I've let you know, but now that I've spilled the beans, I might as well go on and tell the rest. Nope, he ain't going to be married soon. You see, not even Santa Claus can give him the girl that he wants!"

Well, you'd have been surprised to see how she changed. If I'd give her a horse and a wagon, she couldn't have straightened up so quick.

"He can't get her?" she says. "John can't get the girl he loves?"

"Nope. It can't be done."

"Oh, no," says the lady. "He could win a queen, if he chose to try."

"Chose?" says I. "Well, I've heard him talk about her as though she was the moon and the sun and the stars throwed in. She's the whole cheese to him, lady! He talked about her... why, he talked about her as he'd talk about... about a gun!"

Then I seen, when I said that, that even a gun wasn't enough. He wanted that girl of his even more than I wanted my gun!

"I got to go in," I tells her. "D'you think that I really got a chance to get the six-shooter?"

"If the judge has talked to Santa Claus for you," she says, nearly in a whisper, "of course, you will get it!"

"Stay here. I'll be out in a minute and let you know," I says.

"Yes," she says. "I'll stay. I wish you luck. What is it?"

I hung around on one foot. There was something I had to do before I left her. When she asked me, it popped into my head. I had to see her face.

"Ma'am," says I, "d'you mind me seeing your face?"

It didn't seem to please her none. She waited a minute and then says: "Why?"

"Because," I says, "I heard you talk, and I've listened to you laugh, and I figure that if you match up with your voice, seeing your face will be something to remember. Besides, you know, I won't tell nobody about you."

"You're a very strange boy!"

But all at once, she stepped back into the light that fell from the window and threw back her fur collar that curled over her head.

How can I tell you what I seen? It was like a match being struck in the dark. She seemed to shine and grow dim and shine again, while her smile went in and out around the corners of her mouth.

Suppose I put down the particular parts. About her hair—it was like the copper that's been beat up with a hammer, so's there's a lot of burning places and places of shadow mixed up together. She had the biggest eyes I ever seen, and every time she looked up at me, my heart jumped. But what's the use talking about one thing at a time?

To give it to you all in one lump, with that big fur collar rolling around her face and away from her face, she was like a pearl in a velvet case. Then she pulled the collar up again and she was like a light going out, once more.

"Hurry," she says. "I think Santa Claus is in the house! Hurry! Hurry!"

I turned and ran for the front door of the place, but, when I got to the steps leading up to it, I sort of lost my nerve again. By the time I was in front of the door, I was feeling pretty wobbly and weak. The door was about three times as tall as me, d'you see? And there was a pane of glass in the middle of it, with a light shining behind it, and over the top of the door there was an arch like the arch of a bridge. I waited, trying to get up my courage.

Down the main street of the town come a bunch of cowpunchers riding, yelling. I looked away from the house, and in a gap of the trees I could see the 'punchers riding across a lighted window. I could see the glitter of their slickers. I could see the glisten of their sombreros blowed straight back into their faces by the wind of their galloping. They was riding to beat the band, whoopin' it up.

I wished I had been with them instead of standin' there on the porch, wonderin' how I'd be able to look the fine folks in the face if I ever got inside.

Then I thought about the gun. So I went up and banged the knocker. There was steps on the inside right away. Then the door was opened, and I looked up to see the face of a big black man about seven feet tall. He give me a look from head to foot.

"What foh you come heah, white boy?" says he to me.

It sort of peeved me to have him talk like that. "I got a message from the President," says I. "That's why I'm here."

He drew back one foot, like he wanted to kick me off the porch, but I done what I often seen Missouri Slim do when he got into a pinch. I put one hand into my pocket and stuck out the fingers so's it might look as though I'd grabbed a gun or something like that. The man stared at that bulgin' pocket and stopped moving his foot. He didn't think that I had a gun, but he wasn't quite sure. He wanted to slam me right off that porch, but he figured that there was just one chance in ten that I might have a chunk of lead under my fingertip. I didn't blink an eye.

"Come along, sonny," says he. "If you-all's hungry, jus' trot aroun' to the back door. The cook's feedin' everybody today."

"Go call the judge," says I. "I can't waste no more time talkin' with a low colored servant."

His long fingers started working. He sure was mad.

"Call the jedge to talk to a piece of poh white trash like you?" says he. "Git out of that doorway, sonny, before Ah close the door!"

There wasn't no time to waste. There wasn't no time even arguing about it. Inside that there house was the gun that should belong to me. Between me and that gun was a long pair of legs and a mean Negro. I didn't hesitate none; I just closed my eyes, hoped that I wouldn't break my neck and that he wouldn't fall on top of me, and dived for his legs.

DID you ever watch horses in a corral? It ain't always the big ones that are cocks of the walk. The sassy ones are the ones that do the bossing most of the time. Once, I seen a mean little sorrel cow pony back up to a great big draft horse, and they started exchanging kicks. The big horse kicked so dog-gone' hard that her shots went wild. Her hoofs kept shooting above the back of the sorrel, and, when she dropped her hoofs between kicks, the sorrel would plant her—Crack! Plot! Biff! You could hear those hoofs landing a half mile away.

Pretty soon the big mare had enough and went off, squealing and shaking her head. After that, she didn't have nerve enough to drive a yearling away from her feed box. Mind you, that sassy little sorrel wasn't aiming to take any licking. If one kick had landed on her, she'd have run lickety-split to get clear. She just fought while the fighting was good, and happened to win.

Well, that's the way with me. I don't mind taking a chance, but I don't hang around when I see things going against me. I dive for that colored gent's knees. He was standing with his legs a little apart. My head went through the gap. My shoulders hit his shins, and he sat down with a yell. He missed my head when he sat down. Before he could get up, I was on my feet and had hold on a big round-headed cane. I grabbed it in both hands.

"If you make a move at me," says I, "I'll bash your head open."

He got up, groaning-he had twisted an ankle when he went down. "The jedge'll have you in jail for this!" says he.

And there stood the judge himself! He was laughing so hard and so silent, that the shaking of his body kept the whole floor trembling.

He says to the servant: "Sam, I'm sorry this has happened. I suppose you were both at fault. Go back to the kitchen, and have another piece of turkey." Then he turned around to me, while I was putting up the cane and looking mighty foolish. "Son," he says, "you've seen football games, I presume?"

"Nope," says I.

"Well," says he, "that was one of the finest tackles that I've ever looked at. Come on with me!"

I went all cold and sick. "Judge," says I, "can't it be between Santa Claus and me? Do I have to go in there and face the rest of the people? Look here, I'm... I'm as ragged as a scarecrow, and..."

"You are," says the judge, not making no bones about it. "But I'm going to change you. Tommy has a suit he's never worn that's a shade too small for him. It would do very well for you, I think."

Well, can you imagine that? A whole new suit of clothes! He took me upstairs, and, while I was diving out of my clothes and sliding through a bathtub full of water, the judge himself was laying out the clothes. I got into 'em in a jiffy.