Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

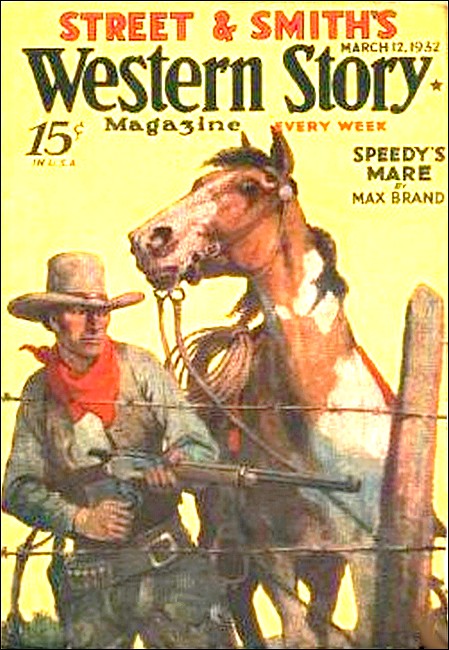

Western Story Magazine, 12 Mar 1932, with "Speedy's Mare"

HIGH on a hill above Sunday Slough, in the dusk of the day, three horsemen sat side-by-side, two very large, and one a slenderer figure. The sun had set, twilight had descended on the long gorge of the mining ravine, and the last dynamite shots of that day had exploded, sending a roar and a hollow boom whizzing upward through the air. From the highest of the surrounding mountains, the rose of the day's end had finally vanished, leaving only a pale radiance, and now the smallest of the three silhouetted horsemen spoke:

"Señor Levine, as you know, I've come a long distance, because it is the pleasure of a gentleman to defy miles when one of his brothers calls for him. But it is already late, and I must inform you that, instead of going to bed, I intend to change horses and return, before the morning, to my own house."

He spoke his English with the formality and the accent of a foreigner.

The largest silhouette of the three, a gross shape that overflowed the saddle, answered: "Now, look a-here, Don Hernando. I ain't the kind that hoists up a white flag before I gotta need to."

"That's the one thing that he ain't," said the third member of the party. "You take Levine, before he hollers, he's got his back ag'in' the wall."

"Aw, shut up, Mike, will you?" demanded the big man, without the slightest passion. "What I wanna say, if you'll let me, is that I ain't called for you, Don Hernando, except that I needed help. And everybody knows that Don Hernando is Don Hernando. It would be a fool that would yell for him, unless there was really a wolf among the sheep, eh?"

"Thank you," said the Mexican. He raised his hand and twisted his short mustaches, forgetting that the dimness of the light robbed this gesture of half its grace and finish. Then he said: "We all love to see reason according to our lights. What reason do you think you can show me, Señor Levine? This a wolf .. . those sheep . . . which may they be?"

"This sheep," said Levine, "we're the sheep. Me and my friends down there in Sunday Slough. There was a time, not far back, when we owned the town. What we said went. But then along comes the wolf, which his name is Speedy, what I mean to say. You don't need to doubt that. Because he's the wolf, all right."

"I have even heard his name," said the Mexican politely.

"You have even heard his name, have you?" said One-Eyed Mike Doloroso. "Yeah, and you'll hear more'n his name, if ever you got anything to do with him. You'll hear yourself cussing the unlucky day that you ever bumped into him. That's what you'll hear."

"One never knows," said Don Hernando. "He is not a very large man, I am told."

"Oh, he ain't so big," said Sid Levine, "but he's big enough. There was me and Cliff Derrick. Maybe you heard of him?"

"He was a very great man," said Don Hernando. "Yes, yes, some of my friends knew him very well, and one of them was honored by having the Señor Derrick steal all that he owned in this world."

"Cliff would do that, all right," said One-Eyed Mike. "I tell you what I mean. Derrick, he'd steal the gold fillings out of your teeth, while you was saying good morning and glad you'd met him. Derrick, he was a man, what I mean."

"Yes," said Don Hernando, "I have heard that he was such a man. And he was your friend, Señor Levine?"

"Yeah," said Levine. "I had Sunday Slough all spread out, and along comes Derrick, and him and me get ready to take the scalp of Sunday Slough so slick and careful that the town won't hardly miss its hair. Then along comes this no-good, guitar-playin' hound of a tramp, name of Speedy, that looks like a worthless kid, and that turns the edge of a knife, and bites himself a lunch out of tool-proof steel . . . what I mean."

"That I hardly understand," said Don Hernando.

Mike Doloroso explained: "What the chief means is this Speedy looks soft, but he's hard-boiled. He's more'n an eight-minute egg, is what he is. You take and slam him the works, and they just bounce off his bean, is what the chief means. He lunches on boiler plate, and dynamite sticks is toothpicks for him, is what the chief means."

"Aw, shut up, Mike. Lemme talk for myself," said the chief, "will you? Don Hernando, he understands English like a gentleman, all right."

"I think I understand what you mean about Don Speedy," said the great Don Hernando. "It is to get a surprise, to meet him."

"Yeah, you said it then, Hernando," said Levine. "A surprise is all that he is. I was saying that me and Derrick, we had things planned, and we had this here county all lined up, and tied, and ready for branding. And then we find out that Speedy is in the way, and first Derrick stumbles over him and pretty near breaks his neck, and then along comes my best bet, which it was my old friend, Buck Masters, that I had got made the sheriff of the county.

"Why, Buck Masters was worth ten times his weight in gold to me. He was set with diamonds, was all he was to me, and along comes that sneak of a wolf of a Speedy, and he picks off Buck Masters, too, and all that Buck gets is fifteen years minus hope, for pushing the queer, which was a rotten break for any gent, I say. And there's Derrick in for life, and a matter of fact, I mean to say, that there ain't any fun around here, like there used to be in the old days, when we had Sunday Slough all spread out and waiting to be scalped."

"I seem to understand you," said Don Hernando. "I also, in a small way, have a little town at my service. It is not much. We in Mexico have not learned the big ways of you americanos. It is very small that we work, in a modest way. Still, it is a comfortable town. Everybody pays me a little bit, not much, partly because I love my people, and partly because they have not much to pay. But we understand one another. If my friends make five pesos, one of them they pay to me, and all is well.

"They are poor, simple people. Some of their pesos they pay to me in oil, others in wine, others in chickens, or in goat's flesh. Fine flour and cornmeal they send to me. Their donkeys toil every day up and down the steep road that goes from my castle to their city. So we understand one another. I am not one who rides down suddenly and robs a man's house. No, not I ... unless the scoundrel has refused my rightful tribute to me. But I leave all of my people in peace. Like a great family, we live all together, Señor Levine, and that, I dare say, is how you lived here in Sunday Slough before this accursed Speedy, who I already despise, came to spoil your happiness."

"Yeah," said Levine with a sigh. "You can say that we lived like a happy family, all right. I won't say no to that. The boys didn't know where they stood, except that it was better a lot to stand on the sunny side of me. I can talk out to a fellow like you, Don Hernando, I guess?"

"Frankness is as frankness does," said Hernando, wasting a smile on the darkness—only the gleam of his teeth showed through.

"Now, then," said Levine, "in the old days, I ran the biggest gambling house in the town, and I got everything my own way. There's only one side to be on in Sunday Slough, and that's my side, what I mean. All the boys in the know are on the right side of the water, believe me. But along comes this runt of a singing fool, this here Speedy, and slams everything, and busts up the picture, and why, I ask you?"

"That I cannot tell," said the great Don Hernando.

"Because," said Levine, his voice warm with indignation, "because, if you'll believe it, I wouldn't let the low-down son of a sea hound get away with nothing. And there was a half-witted sap of a crooked prospector that was a friend of his, by name of Pier Morgan, that claimed to own a mine, and my friend, the sheriff, he turned that mine over to a friend of mine and got Pier Morgan jailed for vagrancy, which is being a tramp, to say it in good English. And Pier Morgan starts shooting his way out of jail, and only shoots himself onto the junk pile, and along comes this here Speedy that nobody had ever heard of, and he takes and picks Pier Morgan off the tin cans.

"Then he takes him off into the hills, and goes and gets him well, what I mean. And while he's getting well, Speedy, he comes down and gets himself a job as a seven-day man, I mean, as a deputy sheriff. You know how it goes. The deputy sheriffs, they didn't last more'n about seven days apiece, in those times, that's what kind of a wide-awake town we had around here, Don Hernando. But Speedy, he starts throwing monkey wrenches into the machine. He goes after my scalp, unbeknownst to me, and he picks off Cliff Derrick, and then my pal, Buck Masters, that was sheriff.

"And now comes along the election for sheriff . . . and whatcha think? If they don't go and put up Speedy for sheriff! Why, he ain't got no name, even, and he calls himself John James Jones, and they laugh their fool heads off, but they get all ready to vote for J.J.J. just the same. Now, I ask you."

"That would be hard on you, señor, to have him for the sheriff of the county?"

"It was heart failure and rheumatism to me to have him only for the deputy sheriff," sighed Levine, "so what would it be to have him for sheriff? There was a time, when my house down there, the Grand Palace, it took in nine tenths of the coin that was pushed over the felt or over the bar in Sunday Slough. And now what kind of a trade have I got? Nothing but the crooks that hate Speedy so bad that they won't patronize the joints that he lets run. So they come to me, and drink my booze, and run up bills and don't pay them, and the roulette wheel, it don't clear five hundred a week."

He hung his head for an instant with a groan, and then he went on: "Now, I'm gonna tell you what, Don Hernando. I know how to clean out this here Speedy. There's a friend of mine called Dick Cleveland, Crazy Dick, that was smeared around by Speedy once, and he's spotted the place where this Pier Morgan is finishing up, getting well and sharpening his knife for my throat at the same time. Now, Don Hernando, if I can snatch this here fellow, Pier Morgan, away, and put him in a safe place, this here Speedy will line out after him, and that'll take him out of my path, and, while he's gone, I clean up on Sunday Slough. Is that clear.. . I mean, is it clear if you're the place where Pier Morgan is taken to?"

"I see your reason, señor, but not mine," said Don Hernando rather crisply.

"I got five thousand reasons for you," said Levine.

"Reasons, or dollars?" asked Don Hernando.

"Both," said Levine.

In Sunday Slough, later on that day, Speedy, public choice for sheriff, sat in his office, which had formerly been office and home of the late sheriff, Buck Masters, now in the penitentiary where Speedy had put him. He sat at his window, much at ease. In dockets upon his desk were various documents that had to do with his workmen wanted by neighboring states, by neighboring counties. But Speedy allowed such business to roll off his back. He was interested in only one thing, and that was cleaning up the town of Sunday Slough.

The job would have been more than half finished, at that moment, except that Sid Levine was still decidedly at large. The great Levine was the major force with which, as Speedy knew, he had to contend. Although he had cut away, as it were, the right and the left hand of the gambler, there still remained the man himself, with his brain so resourceful in evil, and upon the subject of the great Levine the thoughts of Speedy were continually turning.

He heard a light, stealthy step crossing the porch in front of the little wooden building that housed him and his office. Then came a light knock at the door.

"Come in, Joe!" he called.

The door opened. Joe Dale, short, thick-shouldered, strong as a bull and quick as a cat, came into the room. He waved his hand in the dusk.

"Why not a light, Speedy?" he said.

"I like it this way. I think better by this light," said Speedy. He began to strum, very lightly, the strings of the guitar that lay across his knees.

"If you don't stop playing that blooming thing," said Joe Dale, "I'm gonna go on out."

"All right. I'll stop," said Speedy gently. And stretching himself, he settled more deeply in his chair and watched the other man.

"What's up, Joe?" he asked.

"I meet up with Stew Webber," said Joe Dale, "and the fool don't know that you've gone and got a pardon for me out of the governor. When he recognizes me, he pulls a gun. I kicked the gun out of his hand. I slammed that bird on the beak so hard that he nearly busted the sidewalk when he sat down on it. Then I told him what was what. He was gonna collect some blood money out of that, Speedy."

"He's a fool," said Speedy. "He's a fool, though I don't know him. How are things in town, Joe?"

"Everything's so good that it'd make you laugh," Joe Dale said. "I'll tell you what. There was a bird come into the Best Chance Saloon, and he starts telling the boys that he won't vote any ex-tramp for sheriff of this here county. And the boys listen to him a while, and then they take him out and tie him backward on his hoss, and give him a ride out of town. That's what they think of you, Speedy."

"I hope the poor fellow doesn't get a broken neck," said Speedy.

"No, he didn't get no broken neck," the deputy replied. "All he got was a fall, and a dislocated shoulder. One of the camps took him in off the road. He wasn't hurt bad."

"Dog-gone it," said Speedy, "I'll have to go and see him, tomorrow."

"Say, what are you?" asked Joe Dale. "A visiting sister of mercy or what?"

"Oh, lay off that, Joe," Speedy said. "What's the other news?"

"There was a riot started down in the Thompson Saloon. I got there as the furniture begun to break. A big buck hauled off and was about to slam me, but somebody yelled . . . 'That's Speedy's man!' Well, the big bozo, he just backed up into a corner and hollered for help, pretty near. He started explaining how everything was wrong that he'd been thinking. I lined him up and made him pay for the breakages, which he done plumb peaceable. Afterward, he bought drinks for the crowd. Thompson, he says that any bird that don't vote for you, and announces it loud and high, he don't get no liquor in his saloon. And election day, he's gonna run wide open, with free drinks for everybody. I told him that was a fine idea, but the Best Chance Saloon already had the same idea. He said that he'd go in one better than the Best Chance, because he'd loosen up and give a free barbeque, along with the drinks. It's gonna be a great day when you're elected, Speedy."

"Humph!" said Speedy.

"Like you didn't care, is what you mean to act like, eh?" Joe Dale commented. He sat down on the window sill, his big shoulders silhouetted against the street light.

"I care, all right," said Speedy. "But what I'm after is Levine, not the job of sheriff of the county. I don't want that job, Joe, unless I have to have it before I can get Levine."

"I know you want Levine," Joe Dale said, "but you're human, Speedy. You want the sheriff job, too."

"I don't," said Speedy. "I'm human, all right, but not that human. Hunting men isn't the kind of excitement that I want. Only I have to get Levine, because he's got so many others."

"I've gotta believe you, if you say so," answered Joe Dale. "But, if I was you and circulated around the town and heard the boys singing songs about Speedy and J.J.J., it'd give me a thrill all right."

"What's the rest of the news?" Speedy asked.

"There ain't any other news except you. It's all that anybody is talking about. All the big mine owners are gonna close up shop, that day, because they want to make sure that their men get a chance to vote for you on election day."

"That's kind of them," said Speedy. He yawned. "Anything about Levine?" he asked.

"Levine is cooked. His place don't draw no business, no more," said Joe Dale. "The tables are mostly empty, day and night. Levine is cooked in this town. It's a funny thing that the fool keeps hanging on."

"He'll hang on till he gets me, or I get him. He's no hero, but his blood's up."

"He's beat," declared Joe Dale. "He's only a joke, now. He's got no hangers-on."

"He'll have them five minutes after I'm dead," answered Speedy. "Oh, I know how it is with the boys. They like the top dog. You say Levine is beat, but I tell you that I'm more afraid of him right now than when he was on top of the bunch here. Bad times sharpen good brains, and Levine has a brain in his head, don't doubt that!"

"He has a lot of fat in his head, is what he's got," said the other. "You're all wrong, Speedy. Levine is finished in Sunday Slough. Gents have had a taste of law and order, and they like it better than Levine's rough-house. Only, Speedy, we oughta do more about the outside jobs. We get letters every day about thugs and crooks that've come over into our county. We're expected to clean up some of those boys. We oughta do it."

Speedy yawned once more, very sleepily. Then he said: "They behave, over here. They don't even lift cattle. They pay their way. I know a dozen of 'em around town, right now. But as long as they stay quiet, this can be their port of missing men. I don't mind having them about. I don't care how many other states and counties want them . . . all I want is peace in Sunday Slough. It was a rough nest when we came here, Joe, and now it's settling down, I think."

Joe Dale grunted, but, before he could answer, a rapid drumming of hoofs was heard, the rider stopping before the shack. Then, he threw himself from the horse and ran forward.

"Speedy! Speedy!" he called, in a guarded voice.

"It's Juan. It's the half-breed," said Speedy. Instantly he was through the window, going like magic past the form of Joe Dale.

The panting runner paused before him.

"Juan, you idiot," said Speedy, "what are you doing showing your face in town with a price on your head?"

Juan shook the head that had a price on it, as though disclaiming its importance, then he said: "Pier Morgan, the Señor Morgan, he is gone, Speedy!"

Speedy got him by the shoulders and backed him around until the street light, made of the dull shafts of distant lights, fell upon his face.

"Say that again!" he demanded.

"The Señor Morgan, he is gone. I, señor, have a bullet hole through the side of my neck. That is why the bandage is there. I still bleed, my friend. It is not for lack of fighting, but the evil one himself came and took Pier Morgan from me."

"D'you know the name and address of this evil one, Juan?" asked Speedy.

"It is Don Hernando of Segovia, señor. I saw his face only in part. But I knew the scar on his forehead. I was once one of his people. It was Don Hernando, and you will never see Pier Morgan again. He is gone to Segovia. He is gone forever."

"Where's Segovia?" snapped Speedy.

"A little on the other side of the Río Grande. It is more than a day's ride from this place, señor. But it might as well be the journey of a life, for those who go into it never come back. They are held in the teeth of Don Hernando forever! Ah, señor, it was not carelessness on my part, but. . .."

"Be still, Juan," said Speedy. "You know the way to Segovia?"

"I know the way, señor."

"Will you take me there?"

"I take you within sight of it," Juan said. "I do not dare to go closer. I have been in the dungeons of Segovia. I shall never go there again."

"I'll go all the way, Speedy," offered Joe Dale.

"You'll stay here and run Sunday Slough," Speedy answered. "I'll find out about Segovia on the way down, but I imagine that this is a one-man job. You know, Joe, that an army often can't take a place by open assault, but one crook can pick the lock of the gate."

SEGOVIA stood among rocky hills, bare as the palm of the hand. The town itself was an irregular huddle of whitewashed adobe, without a tree in the streets, without a bush to cast shadow. In fact, vegetable life could not exist beside the famous goats of Segovia which, men swore, could digest not only the labels of tin cans, but the tin as well.

How these people lived was a mystery which it was hard to solve. The naked eye could see almost nothing except, now and then, a dun-colored patch of cattle, scattered here and there in the distance. But distances mean little in Mexico, and a cow will run two days to drink of water on the third. A cow will walk thirty miles a day, grazing on a few blades of grass or tearing at a frightful cactus now and then. Still the cow will live and grow, becoming fat enough for marketing in the early spring.

So it was that the outlying herds fed the town of Segovia. In addition, it was said that some of the hardy inhabitants worked along the river, not as boatmen or agriculturists, to be sure, but in other sorts of traffic, generally done at night, work that pays well per hour, but whose pay and pleasure is well salted with death, now and then, death that spits out of the guns of federal patrols and Texas Rangers on the northern side of the stream.

Some of the sons of Segovia, also, went at times to the mines, or to very distant ranches, returning to their homes with money to blow in. They helped to support the two cantinas of the town and the little stores, where the women bought each day enough food to keep starvation off for twenty-four hours. There was even a store, in Segovia, where one could buy clothes, and it was notorious that the second-hand department of that store was filled with wonderful bargains, usually in styles and materials from north of the great river.

These people of Segovia were a race apart, a race all to themselves. Almost to a man, they were slender, agile, and strong. They were like their own goats, which seemed to eat the sand and the sunshine, for there was little else on the ground where they grazed. They and their ancestors had inhabited this place since the days of the conquistadores. The old Spanish blood mixed with the Indian in their veins. They were paler than other peónes. They bore themselves like caballeros. They were fierce, cruel, revengeful, patient, enduring. They loved their friends with a passion; they hated their enemies with still more fervor. They were people to be noted, and to be feared.

All of these terrible clansmen, for like a clan they clung together, looked down on the rest of the world, and looked up to the castle of Don Hernando Garcías.

It was not really a castle. Once, to be sure, the walls had been of stone, cut and laid together with the priceless skill of the Mexican stonecutters. But the centuries had cracked, molded, and eaten the big stones until they had fallen from their places, and a ragged mass of adobe finished in part the outline of the earlier walls.

Still, it remained a castle to the proud, stern peónes of Segovia. When they raised their eyes, a saying had it, they never found heaven or aught higher than the walls of the castle. For in that building, for three centuries and more, there had always been a Garcías called Hernando.

They were as like one another as peas in a pod, all those lords of Segovia. They all looked like the villagers themselves, that is, they were lean, hardy, tough-sinewed, erect, quick- moving, passionate of eye. They all wore the same sort of bristling, short mustaches. They all bore themselves like conquerors.

Sometimes when the people of the town were called the children of their overlord, there seemed to be more than words in the phrase, such a family resemblance existed among them. Their devotion to their lords of the castle, therefore, was all the more passionate and profound because they looked upon them, in true medieval style, as children upon parents. They rejoiced in the pride, cruelty, and wealthy grandeur of their masters and paid the heavy exactions of the Garcías family with perfect calm of mind. Most Mexicans are resolved democrats, but the men of Segovia preferred to be under the thumb of an autocrat.

For one thing, he preserved them from paying taxes to the state, for when tax collectors came to Segovia, they strangely disappeared, and finally they had fallen out of the habit of going to the mysterious little white town above the river. For another thing, according as he was a great and lordly freebooter, they themselves picked up plenty of profit from his expeditions. The present Hernando Garcías filled all the requirements.

He was rapacious, stern, and ruled them with a rod of iron. On the other hand, in settling their village disputes, he was as just as he was cruel. Furthermore, he had always had some large employment on hand. It might be the organization of a long march into the interior, where he harried wide lands and brought back running herds of the little Mexican cattle, to be rustled across the Río Grande and sold "wet" into the northern land. It might be simple highway robbery, organized on a smaller scale, but paying even better. It might be a midnight attack upon an isolated house or a mountain village. It might be a stealthy smuggling of liquor or drugs.

But he was always occupied and always providing employment for his "children", as the men of Segovia loved to call themselves. Since he had come into power, they rode better horses, wore brighter sashes, ate more meat. The cantinas offered them beer, wine, and distilled fire; they had money to buy it. What other elements could they have desired in a terrestrial paradise?

The sun of the day had set, and in the twilight the white town had been filmed across with purple, and the lights had begun to shine out of the doorways, flashing upon groups of children who played and tumbled in the deep, white dust of the streets. Then night gathered about the town, and it seemed to huddle, as though under a cloak, at the knees of the castle, and about the home of Garcías the stars drew down out of the clear sky—or so it seemed to the villagers.

It was at this time that a rider on an old gray mule came into the town, and stopped in front of one of the cantinas to play on a guitar and sing. His voice was good, his choice of songs was rich and racy on the one hand, profoundly sentimental on the other. His hair was dark, so were his eyes; his skin was the rich walnut color of Mexico; his handsome face seemed to fit exactly into his songs of love.

So a crowd gathered at once.

He was invited into the cantina. He was offered drinks. Then they brought him some cold, roasted flesh of a young kid, cold tortillas, hot tomato and pepper sauces. He ate with avidity, leaning well over his food, scooping it up with the paper-thin tortillas.

A jolly, ragged beggar was this minstrel, with a ragged straw hat on his head of the right Mexican style, its crown a long and tapered cornucopia. In the brim of it were a few twists of tobacco leaf and the corn husks for making cigarettes. Furthermore, somewhere along the road, he had found a sweetheart, who had rolled up a number of cigarettes and tied them in pretty little bundles, with bits of bright-colored ribbon. These, also, were attached to the brim of the hat.

He had on a gaudy jacket, the braid of which had tarnished here and ripped away there. His shirt was of silk, very soiled and tattered, and open at the throat. However, a splendid crimson sash was bound about his waist and narrow hips. The flash of his eyes and his white teeth as he ate, or as he sang, or as he danced, made the tawdry costume disappear, particularly in the eyes of the women who crowded about the door of the cantina to look on at the diversions of their lords and masters.

Particularly was he a master of the dance, and it was really a wonderful thing to see him accompany his flying feet with strumming of the guitar, while he retained breath enough in his throat to sing the choruses, at least. Furthermore, and above all, his spinning was so swift that he could unwind the sash that girded him and keep it standing out stiff as a flag in the track of his dancing, and so remain while, without the use of hands, he wound himself into it again.

The old men sat in the corners of the room and beat time with their feet and hands. Their red-stained eyes flashed with fire. The younger men stirred uneasily, nearer at hand. Sometimes one of them would fling his voice and his soul into a chorus. Sometimes one of them would dart out, with a bound, and match the steps of the visiting master. Whenever a village dancer came out to rival the minstrel, the ragged fellow welcomed him with such a grace, such a bright smile, and nodded in such approval of the flying feet, that each man felt Segovia had been honored and flattered.

It was almost midnight before this entertainment ended. By that time the minstrel had collected, it was true, not very many coins, but he had been surrounded by good wishes and ten men offered to give him a bed for the night. However, it appeared that the little glasses of stinging brandy had done more than their work on the minstrel. Like a drunkard, he declared that he would not bother any of them to put him up for the night. Instead, he would gain admission to the castle, where there were sure to be many empty beds!

They listened with amazement. Some of the good-hearted warned him that Garcías's household could not be wakened with impunity in the middle of the night, but the fume of the liquor, it appeared, had made him rash and, therefore, the whole lot of them flocked along to see the performance.

They even pointed out the deep casement of the room of Hernando Garcías, and then they crept away, into hiding in nooks and corners and shadows among the nearer horses to watch the fortune of the rash young entertainer, as he strove to sing and dance his way into the house of the great man.

DON HERNANDO was about to sink into a profound slumber with the peaceful mind of one who has done his duty and done it very well.

For a little earlier, that evening, he had arrived with his prisoner, the gringo, Pier Morgan, and had ridden up to his house, not through the village streets, but up the narrow and steep incline that climbed the face of the bluff and so came directly to the outer gate of the building. By this route he came home, partly because he did not wish to be observed, partly because he would thus have his prisoner closer to the dungeon cell in which he was to be confined, and partly, also, because he loved to impress and mystify his townsmen.

He knew that some of the household servants would soon spread everywhere in Segovia the news that a prisoner had come, a gringo. Even the little children would soon be buzzing and whispering. But just as surely as the story was bound to fill every house in Segovia, so sure was it that not a syllable would pass beyond. The secrets of Don Hernando were family secrets, as it were, and the whole town shared in them and rigorously preserved them.

The good Don Hernando, having lodged his captive in one of the lowest and wettest of the cellar rooms of the old house, posted a house servant with a machete and a rifle to watch the locked door. He had then gone on to his repast for the evening, content.

He had been told by Sid Levine that he would have to use every precaution to keep his prisoner from falling into the hands of Speedy again, and this subject constituted part of his conversation with his lady, as they sat together at table. She was a dusky beauty, and now that the years were crowding upon her and she was at least twenty-two, she began to be rounder than before, deep of bosom and heavy of arm. Her wrist was dimpled and fat, and so were the knuckles of her fingers. But her eyes were bright, and she carried her head like a queen, as befitted the wife of Don Hernando Garcías.

When she had seen and distantly admired the new thickness of the wallet of her spouse, he explained the simplicity of the work which he had done. It was merely to receive from one man the custody of another, and to ride the man down across the river and hold him in the house.

"This Levine, who pays me the money for the work, is a simpleton," he said. "He seems to feel that his enemy, Speedy, is a snake to crawl through holes in the ground, or a hawk to fly through the air and dart in at a casement. But I told the señor that my house is guarded with more than bolts and locks and keys, for every man within the walls of it has killed at least once. This vagabond, this Speedy, of whom they talk with such fear, had he not better step into a den of tigers than into the house of Garcías?"

The same fierce satisfaction was still warm in his breast when he retired to sleep, and he was on the point of closing his eyes when he heard the strumming of a guitar just under his window. For a moment he could not and would not believe his ears. Then rage awoke in him, and his heart leaped into his throat. It was true that the townsmen took many liberties. It was true that they acted very much as they pleased within their own limits, but those limits did not extend to the very walls of the castle. No, the space between the last of their houses and his own outer wall was sacred ground, and no trespassing upon it was permitted!

"A drunkard and a fool," said Garcías to himself, as he sat up in his bed.

He listened, and from the outer air the voice of the singer rose and rang and entered pleasantly upon his ear. It was an ancient song in praise of great lords who are generous to wandering minstrels. On the one hand, it flattered the rich; on the other hand, it poured golden phrases upon the singers who walk the world.

The purpose of the song seemed so apparent that Garcías ground his teeth. No man could be sufficiently drunk to be excused. He, Garcías, was not in a mood to allow excuses, anyway.

He bounded from his bed and strode to the window, catching up as he went a great crockery wash basin from its stand. With this balanced on the sill, he looked over the ledge, and below him, smudged into the blackness of the ground, he made out clearly enough the silhouette of the singer, from whom the music rose like a fountain with a lilting head. Garcías set his teeth so that they gleamed between his grinning lips. Then he hurled the great basin down with all his might.

It passed, it seemed to him, straight through the shadowy form beneath. Even the stern heart of Garcías stood still.

It was true that his forebears, from time to time, had slain one or more of the townsmen, but they had always paid through the nose for it. The men of Segovia were fellows who could be struck with hand or whip, by their master, but, when it came to the actual taking of a life, they were absurdly touchy about it. They insisted upon compensation, much compensation, floods of money, apologies, declarations of regret in public, promises that such things should never happen again. On certain occasions, they had even threatened to pull the old castle to bits and root out the tyrants.

So Hernando Garcías stood at his window, sweating and trembling a little, and cursing his hasty temper. For the song had ceased, or had it merely come to the end of a stanza?

Yes, by heaven, and now the sweet tide of the music recommenced and poured upward, flowing in upon his ear. At the same time, Don Hernando unmistakably heard the tittering of many voices.

"By heavens," he said, "the louts have gathered to watch this. It is a performance. It is a jest, and I am the one who is joked at."

He said other things, grinding them small between his teeth. It was excellent cursing. It was a sort of blasphemy in which the English language is made to appear a poor, mean, starved thing. For the Spaniard swears with an instinctive art and grace. There are appropriate saints for every turn of the thought and the emotions. And Don Hernando called forth half of the calendar as he cursed the minstrel.

He turned. The washstand was nearby, and on it remained the massive water jug, half filled with a ponderous weight of water. It was not so large a missile as the wash bowl, but it was at least twice as heavy, and it was the sort of thing with which a man could take aim.

The fear that he might have committed murder, the moment before, now died away in him. He wanted nothing so much as to shatter the head of the singer into bits. He wanted to grind him into the ground. So he rose on tiptoes, holding the jug in both hands, and he took careful aim, held his breath, set his teeth, and hurled that engine of destruction downward with the velocity of a cannon ball.

It smote—not the form of the minstrel. It must have shaved past his head with only inches to spare, but the undaunted voice of the song arose and hovered like a bird at the ear of Don Hernando. The jug was too small. He needed a large thing to cast. And presently his hand fell on the back of a chair. It was an old chair, the work of a master. It had been shipped across the sea. Even its gilding represented a small fortune, and on the back of it was portrayed the first great man of the Garcías line.

That was why it stood in the room of the master of the house. For every morning, when he sat up in bed and looked at the picture on the back of the chair, he was assured of his high birth and of the long descent of his line, for the picture might have stood for a portrait of himself. There were the same sunken eyes, the same hollow cheeks, the same narrow, high forehead, and even the same short mustache, twisted to sharp points. He thought not of the portrait, alas, as he stood there by the window, teetering up and down from heel to toe, in the grand excess of his wrath. But, catching up the chair, he hurled it out of the window, and leaned across the sill, this time confident that he could not fail of striking the mark.

It did not seem to him that the minstrel dodged. But certain he was that he had missed the target entirely, for the song still arose and rang on his ears! Then, lying flat on his stomach across the window sill, he remembered what it was that he had done. The chair must be smashed. Undoubtedly the portrait was ruined. Woe coursed through his veins. For it was plain that he had cast away with his own hand what was as good, to him, as a patent of nobility. He groaned. He staggered back into the room, gasping, and buried his fingers in his long hair.

Then he flung himself on the bell cord that dangled near the head of his bed, and pulled upon it frantically, not once, not twice, but many times, and, when he heard the bell jangling loudly in the distance, he hurled a dressing gown over his shoulders.

Hurrying feet came to the door of his room. There was a timid knock; the door opened.

"Manuel, fool of a sleepy, thick-headed, half-witted muleteer, do you hear the noise that is driving me mad?"

"I hear only the noise of the singer, señor," said poor Manuel.

"Music! It's the braying of a mule!" shouted Garcías. "Go down. Take Pedro with you. Seize the drunken idiot by the ears and drag him here. Do you hear me? Go at once! Go at once!" He seized the edge of the door and slammed it literally upon the face of Manuel.

It eased his temper a little to hear the grunt of the stricken man, and to hear the muttered names of saints that accompanied him down the hallway.

DON HERNANDO lighted a lamp and paced hurriedly up and down the room. From the windows, he heard again the tittering of many voices. Yes, it was as on a stage, and the crowd was enjoying him as one of the actors. Rage seized upon his heart. He thought of the ruined portrait on the chair and a sort of madness blackened his eyes.

At one end of the room hung various knives. He fingered a few of them as he came to that side of the room but, remembering the revolver, pistols, rifles, and shotguns that were assembled in a set piece against the opposite wall, he would hastily go back and seize on one of these, only to change his mind again. Nothing could satisfy him, he felt, except to feel the hot blood pouring forth over his hands.

Then came rough voices in the outer court and stifled exclamations from the near distance. That soothed him a trifle. He shouted from the window, leaning well out: "Bring up the wreck of the chair and, if you pull off the ears of the singer, I, for one, shall forgive you!" He retired and sat in another chair, deep and high, wide as a throne and with a tall back. Seated so, nursing his wrath, his fingers moved convulsively, now and again, as though he were grasping a throat.

Presently up the hall came the voices and the footfalls of Manuel and Pedro. The door opened. They flung into the room the body of a slender man, who staggered, almost fell to the floor, and then, righting himself and seeing the glowering face of Don Hernando in the chair in the corner of the room, bowed very deeply, taking off a tattered straw hat and fairly sweeping the goatskin rug with it.

"Señor Garcías," said the minstrel, "I have come many miles to sing for you. One of my ancestors sang for yours, generations ago. And so I have come."

The master of the house glared.

Pedro, in the meantime, was presenting him with the wreckage of the chair. The old, worm-eaten wood had smashed to a sort of powder. Of the back panel, in which the face was painted, there remained no more than scattered splinters. He picked up a handful of that treasured panel. Only a twist of a mustache, only one angry eye glared forth at him from the ruin. Garcías dropped the wreckage, rattling upon the floor, feeling sure that he would kill this man.

He surveyed him, the dark head and eyes, the large, over-soft eyes, like the eyes of a lovely woman. He regarded the smile, the sort of childish delicacy with which the features were formed.

Then he said: "Señor minstrel!"

The stranger bowed, brushing the floor once more with the brim of his hat.

The fool seemed totally unconscious that he was about to receive a thunderbolt of wrath that would annihilate him.

Suddenly Don Hernando smiled. It was a smile famous in the history of his family. Every Garcías had worn it. Every Garcías had made that same cold smile terrible to his adherents. All of Segovia knew it. Manuel and Pedro shuddered where they stood. But the idiot of a minstrel stood there with high head.

One thing was clear. To act on the spur of the moment would be folly. Together with the rich, red Castilian blood, there flowed in the veins of Garcías a liberal admixture of the Indian. That blood mastered him now and, still smiling, he told himself that time must be taken with this affair. The painting on the chair had been a work of art. The revenge he took would be a work of art of equal merit, a thing to talk about. Why not? The fellow was not of Segovia. He was not of the chosen people. He came from a distance.

So Garcías cleared his throat, and, when he spoke, it was softly, pleasantly.

Another shudder passed through the bodies of the two servants. Like all the others in the house, each of these had killed his man, but the smile and the voice of Don Hernando, in such a mood, seemed to both of them more terrible, by far, than murder.

"The Garcías family keeps an open house for strangers," he said. "We have rooms for all who come. But chiefly for such good singers. I wish to hear you sing again. Manuel, Pedro, take him down to the most secure room in the house. You understand?"

His fury mastered him. He thrust himself up, half out of the chair, with glaring eyes, but the half-witted minstrel was already bowing his gratitude and sweeping the floor with his hat, so that he entirely missed both the gesture and the terrible expression of the eyes.

Don Hernando managed to master himself. Then he said: "My friend, you will be well looked after. You will be put in a safe place. All the enemies you have in the world could not disturb your sleep, where I shall put you. You, Pedro, will sleep outside of his door, armed. You understand?"

"Señor, I understand," said Pedro. He had heard the songs of this man. In his heart he pitied him, for he saw that the naked wrath of the master was about to be poured out upon his head. But it never occurred to him to disobey. Besides, he was really a savage brute. So were all of that household, hand-picked brigands. He soon mastered any feelings of pity or of remorse.

"I understand," he repeated. "The deepest room of the house, señor, if you wish."

"Yes, the deepest . . . the deepest! The one with the strongest door," repeated the great Garcías through his teeth, "the smallest window, and the heaviest lock . . . the one where sleeping clothes are always ready, bolted to the wall. You understand? You understand?" His voice rose to a high, whining snarl, like that of a great cat. Then he added: "And in case he should want to sing, let him have his guitar. Yes, let him sing, by all means, if he wishes. I am only afraid that I shall not be able to hear the songs."

Manuel and Pedro grinned brutally. Their master laughed, but the fool of a minstrel was again bowing to the floor and seemed to fail to see or to understand his dreadful predicament. That was all the better. He would learn, soon enough, what was to befall him. The guards took him to the door of the room.

"Strip him!" shouted the great Garcías, and slammed the door behind the trio.

He went back, then, to the wreckage of his precious chair and picked up, again, the splintered wood upon which the remnants of the portrait appeared. Holding them tightly grasped in his hand, he groaned aloud, with such pain that he closed his eyes.

He went to the window. His rage was overcoming him, and he was feeling a trifle in need of air. From the open window, he could hear long, withdrawing whispers and murmuring down all the alleys that approached the face of the castle.

"Well," he said through his teeth. "Very well, indeed. They shall learn that the old spirit has not died in the blood of Garcías. They shall learn that, if nothing else." His spirit was eased as he thought of this. There is nothing that impresses a Mexican more than the signs of absolute, even cruel power. He was right in feeling that the men of Segovia would be impressed by the object lesson that he would give them in the person of the young minstrel, the unlucky stranger.

Still, when he lay upon his bed, about to fall asleep, he roused to complete wakefulness. For it occurred to him that the many bows of the singer, as he stood in the presence of danger, might have been useful in concealing a certain smug expression of self-contented pleasure which, as Garcías remembered, had seemed to be lingering about the corners of the eyes and mouth, every time he straightened. At all events, one thing was clear, the man was an idiot.

Then he soothed himself by devising torments. It was clear, above all else, that for the destruction of the famous Garcías portrait he deserved to die. With the placid emotions of a cat about to torment a mouse, the great Don Hernando finally fell asleep.

THE two house servants were conducting the young dancer and singer down winding stairs that sank toward the bowels of the earth, as it seemed. They grew narrower and narrower. The feet slipped in the moisture that covered the stones. The stones themselves were worn by the centuries of footfalls that had passed over them. Their steps echoed hollowly up and down the descending corridors. The head of the tall Pedro bowed, as he avoided the roof of the passage, rounded closely in. Finally they passed the mouth of a black corridor.

"Down there," said Manuel, "is the last dear guest that the Señor Garcías brought home with him. He, also, has a secure room. He, also, is guarded against intrusion. Oh, this is a safe house, friend. Danger never breaks in from the outside." He laughed, and his brutal laughter raised roaring echoes that retreated on either hand.

The minstrel merely said: "This should be cool. But also rather dark. However, darkness and coolness make for perfect sleep in summer."

They went on, the two servants muttering one to the other, and so they came to the last hall of all, in which there was the door of a single room. In the hallway lay slime and water half an inch thick, and the horrible green mold climbed far up the walls on either hand. There was a low settle in the hall.

"You'll sleep there, Pedro," said Manuel with a chuckle.

"A plague on my luck," said Pedro. "If I don't catch rheumatism from this, I'm not a man. It needs a water snake to live in a hole like this."

Manuel was unlocking the door. It groaned terribly on its hinges and gave upon a chamber perhaps eight feet by eight, and not more than five in height. It was like a grisly coffin. A breath of foul air rolled out to meet them.

"Is this . . . is this the room?" gasped the poor minstrel.

"Yes, you fool," said Manuel. "Strip him, Pedro."

They put the lantern on the floor. Between them they tore the clothes from the body of the poor singer and flung them to the floor. But when he was stripped, they paused, and looked him over in bewilderment.

For he presented not at all the picture which they expected to see, of a starved and fragile body. He seemed slender, in his clothes, to be sure. But he was as round as a pillar. He was as deep in the chest as he was wide, and over arms and back and legs spread a cunning network of muscles, slipping one into the other, strand upon strand. An anatomist, with a pointer, could have indicated his muscles without effort.

"Hey!" said Manuel. "He could be a bullfighter." He thumbed the shoulders of the captive. It was like driving the thumb into India rubber.

"But what does it mean, my friends," said the minstrel. "Why am I stripped? Alas, I am a poor man. I have done no wrong."

"Be quiet," said Pedro. "You were told about a secure room and this is it. And you were told about bedding and this is it, perfect to fit you, like a suit of clothes ordered from the tailor." As he spoke, he dragged a mass of chains from the wall, and then locked them around the wrists and the ankles of the trembling minstrel.

"Ah, my friends," said the youth, "this is cruel and unjust. Trouble will come upon your master for this act. Trouble, for sure, will follow him."

They left the room, slammed the door upon him, and turned the key in the lock.

"There's a guitar against the wall beside you. You can play and sing in the dark, amigo," were their last words.

They were hardly gone, when the minstrel raised his manacled hands to his head, and, from the base of a curl, he drew forth a little piece of flattened steel, like a part of a watch spring. With this, he began to work, cramped though his fingers were for space, upon the lock of the manacle that held his left wrist. He did not work long before the manacle loosened. It slipped away, and presently its companion upon the other wrist likewise fell to the floor. The singer stooped over his anklets. They presented a little more difficulty. But they, also, presently fell away, and he was free in the room. After that, he felt his way along the wall to the heap in which his clothes had been flung. There was a bitter chill in the air of the dungeon, and he hastily pulled on his garments, one by one, the shoes last of all. They had soles of thin whipcord, silent as the furred paw of a cat for walking over stone, and light as a feather.

When he was dressed, he went to the door and felt of the lock. To his dismay, he found that the whole inside of the lock was simply one large sheet of steel. The key did not come through the massive portal! He stood for a time, taking small breaths, because the badness of the air inclined to make him dizzy. But eventually he had a thought. Outside, in the corridor, Pedro the guard was already asleep, for the sounds of his snoring came like drowsy purring into the dungeon cell. So the prisoner found his guitar and lifted his voice in song. He took care in the selection of his music. The ditties that found his favor, now, were the loudest, and he sang them close to the door.

It was not long before there was a heavy breathing against the door, and then the loud voice of Pedro, exclaiming: "Half-wit, I, Pedro, wish to sleep! If you disturb me again, I shall come in there and make you wish that it were Garcías instead of me. He shall have only half of you. I'll eat the other half."

"Ah, amigo," said the minstrel, "I am as cold as a poor half-drowned rat. May I not have covering? The floor of the room is covered with wet slime and. . . ."

"Shiver, then," said the Mexican angrily. "I have told you before, what I shall do if you sing once more."

The singer waited until he heard the snoring begin again, and then, for a second time, his voice arose like a fountain of light.

The answer came almost at once. The key groaned in the lock, the door was thrust wide, and in rushed big Pedro, cursing.

From the shadow beside the door, the minstrel struck with a fist as heavy as lead, hitting home beneath the ear. Pedro slumped forward on his face in the slime.

He was quickly secured, ankle and wrist, in the manacles, which had just held the singer. The wet filth in which he lay brought back his senses after a moment or so. He opened his eyes, groaning, in time to feel the revolver being drawn from its holster on his hip and, by the light of the lantern, he saw the minstrel smiling down upon him. Exquisite horror overcame big Pedro. Agape, he looked not so much at the slender youth before him as at a terrible vision of the wrath of Garcías when the lord of the house should hear of this escape. He could not speak. Ruin lay before his eyes.

"Good bye, Pedro," said the minstrel. "Remember me all the days of your life and never forget that I shall remember your hospitality. As for your master, who you are fearing now, don't worry about his anger. He shall have other things to think of before many minutes."

He left the room before the stupefied Pedro could answer and closed the door gently behind him. He picked up the lantern and quickly climbed to the black mouth of the corridor down which, as he had been told, the last guest of Garcías was housed. He could guess the name and the face of that poor stranger.

Down that corridor he went, and presently around a sharp elbow turn the light of another lantern mingled with that of the one that he was carrying. He went on at the same pace, dropping the revolver that he carried into a coat pocket. He could take it for granted that, if a guard waited outside the door of this prison, the face of the singer would not be known to the man.

So he went on fearlessly and now saw the man in question seated on a stool that he had canted back against the wall. With his arms folded on his breast, he was sleeping profoundly. The minstrel laid the cold muzzle of the revolver against his throat and picked up the sawed-off shotgun from his lap. Then, as the rascal wakened with a start, he said: "Be quiet and steady, my friend. There is no harm to come to you except what you bring with your own noise. Stand up, turn the key of that locked door, and walk into the cell ahead of me, carrying the lantern."

"In the name of the saints," said the guard, "do you know that it is an enemy of Garcías who lies there?"

"I know everything about it," said the singer. "Do as I tell you. I am a man in haste, with a loaded gun in my hand. Pedro loaned it to me," he added with a smile.

The guard, one of those Oriental-looking fellows one sometimes finds south of the Río Grande, with ten bristles in his mustache and slant eyes, studied the smile of the stranger as he looked up and suddenly he felt that he recognized in this man a soul of cold iron. He rose with a faint gasp and, striding to the locked door, turned the key and stepped into the gloom within.

There, stretched on a thin pallet of straw, was the prisoner. He had not been stripped; there were no irons upon him. Plainly he had not excited the wrath of the great Garcías to the same degree as the singer, who now stooped over and fastened the manacles that were chained to the wall upon the wrists and the ankles of the guard.

The latter was moaning and muttering faintly: "The saints keep me from the rage of Don Hernando! Oh, that ever I was born in Segovia!"

The prisoner, sitting up, yawning away, settled his gaze beneath a frown at the other two and suddenly bounded to his feet.

"Speedy!" he cried. "I didn't know you, with the color of your skin and. . . ."

"We have to go on," said Speedy calmly. "There's something more for us to do before we leave the house of the great Garcías. He's fitted the two of us with such good quarters that we ought to leave some pay behind for him, Pier. Come along with me. This chap will be safe enough here. Rest well, amigo. When the others find you in the morning, or even a little before, they will give you the last news of us."

So he passed out from the cell and locked the door behind him.

Pier Morgan, in the meantime, was gaping helplessly at him.

"Speedy," he said, "I'm tryin' to believe that's your voice that I'm hearing. I'm trying to believe that. I've never seen anything finer than your face, man, and never heard anything sweeter than your voice. But how did you come here? Did you put on a pair of wings and hop in through a window?"

"Don Hernando asked me in," Speedy said, smiling faintly. "He even sent out his men and insisted on my coming in. He's a hospitable fellow, that man Garcías, and I can't wait till I've called on him again. How do you feel, Pier? Are you fit to ride a bit, and do some climbing, perhaps, before we start the riding?"

"I'm fit to ride . . . I rode all the way down here," said Pier. "And I can ride ten times as far in order to get away. This here place is a chunk of misery, Speedy. I've had something like death inside of me ever since I smelled this dungeon. Let's get out quickly and let your call on Hernando go!"

THE door of the bedroom of Garcías was locked from the inside. He had gone to bed, with the flame turned down in the throat of the lamp. Now he awoke, not that he had heard any suspicious sound, but because there was a sighing rush of wind through the room, as though a storm had entered.

The nerves of Garcías were not entirely at ease. His dreams had been pleasant, but very violent. In his sleep, he had killed the insolent gringo singer by scourgings that had flayed his cursed body to the bone. Again, he had toasted his feet at a low fire, he had tormented him with the water cure, and he had hung up the American by the hair of the head. Also, he had dreamed of various combinations of these torments, and, although it was true that Garcías was to be the torturer, and not the tortured, it was also true that his nerves were jumping. All the tiger in him had been fed in his sleep. And the tiger in him now demanded living flesh, so to speak.

At the noise of the murmuring in his room, like the rising whistle of a storm wind, he raised himself impatiently on one elbow and turned his head toward the door. To his amazement, that door was open! He rubbed his eyes and shook his head to clear away the foolish vision, for he knew that no one in the house would ever dare to attempt his locked door. Even if there were someone foolish enough to make such an attempt, the lock of the door would itself give simple warning, for the key in the bolt could not be stirred without making a groaning sound, audible all up and down the corridor outside.

He opened his eyes again and scowled at the offending door, but now the vision was more complicated. A man stood in the doorway and was gliding with a soundless step straight toward his bed. The light of the lamp was very slight but, as he stared, the bewildered Garcías saw that it was the face of the gringo minstrel who was all the time drawing nearer to him.

He grunted. In the distance, the door was being closed by a second shadowy figure. But there was always a weapon at the hand of Garcías, and now he snatched his favorite protection from beneath his pillow. It was a rather old-fashioned double-barreled pistol, short in length, but large in caliber. It was equipped with two hair triggers, and it fired a ball big enough and with sufficient force to knock a strong man flat at fifteen yards. He always had it with him, in a pocket during the day and under his pillow by night. It had served him more than once. He had killed men many a time in his life, but all other weapons had been less deadly than this old-fashioned toy.

So, snatching it out, he tried to level it at the gringo. But he found his hand struck down, a cleaver stroke, as it were, falling across the cords of his wrist and benumbing the entire hand.

The pistol slipped into the sheets of the bed. A second stroke, delivered with the flat edge of the man's palm, fell upon the neck of Garcías, where the nerves and the stiff tendons run up to the skull. He floundered a little, but with only vague movements. He was stunned as though with a club.

Before he was entirely recovered from the effects, he found that the minstrel was sitting comfortably on the edge of his bed, toying with that double-barreled pistol with his left hand, but in his right was a short-bladed knife, the point of which he kept affectionately close to the hollow of Don Hernando's throat.

The second shadowy form had drawn closer and stood on the farther side of the bed. With disgust, Don Hernando recognized the face of Pier Morgan. He had received twenty-five hundred dollars for taking Morgan into the southern land across the river. He would receive twenty-five hundred more for keeping him there, or for making away with him. This was a bad business, all around. He wished for wild hawks to tear the flesh of the minstrel.

"I see," said Garcías, "how it is. You tricked the guards and got away from them, but you know that you can't get out of the house. Well, then, I am to let you go . . . through me you wish to manage it, but I tell you, my friends, that you never can persuade me. I know that you will not kill me, because you fear what will happen to you before you manage to get clear of the house. You think that you still have a chance to talk to me and to give me orders, but every door and every entrance to the house is guarded night and day!" He laughed a little as he ended. His fury made his laughter a tremulous sound.

"Speedy?" said Pier Morgan, "we can't waste time. We must hurry."

He said it in English naturally. But Don Hernando understood the language perfectly. Also, the name itself struck his ear like the blow of a club. He stiffened from head to foot.

"You are not Speedy," he exclaimed through his teeth. "Your skin is as brown as. . . ."

"As walnut juice, amigo?" suggested Speedy.

The lips of the Mexican remained parted, but no word issued from them.

Then Speedy said: "You see how it is, Don Hernando? I knew that your house was so guarded that only a bird could fly in safely through a window. And I had no wings. So I came and sang at night, to disturb you. Do you understand?"

The teeth of the Mexican ground together. He said nothing.

"Then, when you were sufficiently annoyed," Speedy said, "you sent for me to get me into your house and throw me into your hole of a prison. But I expected that, Garcías. I was prepared for all of that trouble, and it was worthwhile, because I had to reach my friend, Pier Morgan. I knew that it would be hard to hold me in a cell, because I know the language of locks."

Garcías rolled his eyes toward the door of his own room.

"The others were no harder," said Speedy. "Besides, your men are all fools. Like dogs that are kept half starved. They have plenty of teeth, but no brains whatever. They pointed out the room where Pier Morgan was kept on the way down to your slimy pigpen in the cellar. One of your servants sleeps in one of those cells, and another sleeps in the second. They are not happy, Don Hernando, because they are afraid of what you will do to them when they are set free."

"I will have them cut to pieces," said Garcías, "before my eyes. I will have them fed to dogs, and let you watch the feeding, before you are cut to bits in your turn!"

"You are full of promises, Don Hernando," Speedy observed, "but that's because you don't understand how simply we can get out of your house through that window with a rope of bedclothes."

"Idiots!" said Don Fernando. "Segovia lies beyond, and will have to be passed through. And there are always armed men there!"

"True," said the minstrel, "and I shall let them know that I am passing. I shall sing to my guitar."

"Are you such a half-wit?" Garcías said with a snarl.

"They know that I was dragged into your house," said the other, "but they don't know that I was treated like a whipped dog."

"Ha?" said Hernando.

"Besides," Speedy said, "I shall have something to show them, which will prove that Garcías forgave me for disturbing him in the middle of the night."

"What?" demanded the man of the castle.

"A ring from your finger," said Speedy.

Don Hernando gripped both hands to make fists. His fury was so great that his brain turned to fire and threatened to burst. For he could see that the inspired insolence of this gringo might very well enable him to do the thing that he threatened.

"I shall believe when I see," said Don Hernando.

"You will believe and see and hear, all three," Speedy said, "for I shall put you on a high chair to look things over. I shall put you where you'll be found in the morning. Tie his feet, Pier. I'll attend to his hands."

Hand and foot, the lord of the town of Segovia found himself trussed and made utterly helpless. That was not all, for then a gag was fixed between his teeth. The language of Speedy was more terrible than the insulting treatment he was giving to his host. He apologized, every moment, for the necessity of being so rough with so great a gentleman in his own house. For his own part, he regretted such a necessity. He would do much to avoid the occasion for it. It was only, after all, that murder and cruelty and dungeon tortures were not popular on the northern bank of the river, and even here, to the south of it, the people must be shown an example. They must be shown that tyrants are also cowards and that cruel beasts are really fools. For that reason he, Speedy, intended to give the people of Segovia an object lesson in the person of their master.

As he spoke, he drew from the struggling hand of Don Hernando almost his dearest possession, his signet ring. It was merely a flattened emerald of no great value, but it was carved with the arms of the house of Garcías. That ring and the portrait which had been ruined that night were his two clear claims and proofs of gentility.

He saw the second one departing in the possession of the same scoundrel; he turned blind with fury. When he recovered from the fit, he was hanging from the sill of a window of his room by the hands, his back turned to the wall. Strong hands held him at the wrists. Presently his arm muscles would weaken. The strain would come straight upon bones and tendons. And then the real torment would commence. But what would that matter compared with the exquisite agony of being found in this humiliating position in the morning by the loyal populace of Segovia?

IN all the house of Garcías, among all of his people, was there not one careful soul to look out a window, at this time, and see the two villains who now clambered down their comfortably made rope of bedding to the ground?

No, well filled with food and drink, they were snoring securely in their beds. As for the guards, they would be awake. He always took pains to be sure that they would sooner risk their necks than fall asleep either at the main door or at the one that opened over the bluff. But now he wanted a guard outside the place, and not within the massive old walls.

His anguish grew. He turned his head and saw the wretches standing upon the paving stones at the base of his wall. He bowed his head to stare down at them, while rage choked him, and there he saw Speedy remove from his head the hat with the tattered straw brim and sweep the ground with it, making a final bow.

Anguish, shame, fury, helplessness, fairly throttled the great Garcías. He became alarmed. He was unable to breathe well. He had to give all his attention, for a time, to drawing in his breath deeply. Fear of strangling at once made his heart flutter desperately. He compared it to the beating wings of a trapped bird, a bird dying of fear. Aye, he was like a bird, he thought, like a chicken hanging by the feet in the market, plucked, ready for the purchasers to thumb before making sure that it was fat enough to buy and take home. If only he could cry out!

He had only his bare feet to kick against the wall, and he soon bruised the flesh of his feet to the bone. But no one answered. No one looked out of the adjoining windows to discover the master, so crucified in shame and pain. Then he heard a sound that fairly stopped the beating of his heart again. It was rising from the lower streets of the town, and it was the strumming of a guitar, and the sound of a fine tenor voice that rose and rang sweetly through the air.

It was true, then, that the rascal had determined to do all as he had said? Was he to outbrave the fierce men of Segovia and increase the shame of Garcías? A demon, not a man, was walking down the street and playing on that guitar, singing the words of those old songs.

But Speedy and Pier Morgan did not get unhindered from the town.

It was said that the men of Segovia slept as lightly as wild wolves, which they were like in other respects, also, and, when they heard the voice of the minstrel, one, then another and another, jumped up in the night and went out to see what the disturbance might be. For they had seen the fellow dragged within the walls of the house, and what had happened to him in there was much pleasanter to guess than to see.

So they came running out, a score of those ragged, wild men, and found the minstrel, as before, mounted on the ancient gray mare, with a white man walking at his stirrup. This was too strange a sight to let pass.

There was one elderly robber, long distinguished in forays, known as by a light, by the great white scar that blazed upon his forehead. He was gray with years and villainy, and music did not particularly tickle his fancy.

He took the mule by the bridle and halted it. "What is the meaning of this?" he demanded. "I saw you snatched into the door of the castle like a stupid child. High time, too, what with your caterwauling. Now you are here. Who set you free?"

"An angel, father," said Speedy, "walked into my room, wrapped me in an invisible cloak, and took me away, with this man."

"So?" said the desperado, darkening. "I'll have another kind of language out of you, before I'm through." He pulled out a knife as long as a sword, and glared at the boy in the saddle.

"If you're in any doubt," Speedy continued, "take us back to the house. If Garcías is wakened again, tonight, he will be interesting to the people who disturb him. You, however, are a wise man and know best what is to be done."

The veteran scowled. Some of his companions had begun to chuckle. They enjoyed this predicament.

"I ask questions when I can't understand," he said. "Now let me ask these questions again. Señor the singer, you will sing a new tune, if you try to make a fool out of me. You are here after midnight. So is this man. People do not start a trip at this time of the night."

"Look at his hands," said Speedy.

"Aye," said the other, "I see that they are tied together behind his back. And what do I understand by that?"

"You will understand," Speedy said, "when Garcías knows that you have stopped me in the streets and made me explain before the people. I am taking this man to a friend of Garcías."

"Ha!" said the man with the scar, coming a little closer, glowing his disbelief. "Taking him where? How will you prove that?" He snatched a lantern from the hand of another, and held it up to examine the face of Speedy.

The latter used the light, thrusting forward his left hand with the emerald ring on the largest finger. "Do you know the signet of Garcías?" he demanded harshly. "Would he give it to me for pleasure, or because of an important errand in his name?"

The other was stunned. He squinted at the ring. The face of it was well known. His companions were already falling back from the scene. They did not wish to interfere where the will of the master of Segovia was expressed in such unconditional terms as this.

The man of the scar no longer hesitated. He released the head of the mule and stepped back. "Well, amigo," he said, "there is a time for talk and a time for silence. This is a time for silence. Go along."

"Perhaps you wish to know to what place I am taking the prisoner?" asked Speedy. "You are many and I am one. You can force me to tell you even that."

The man of the scar muttered: "You can take him to Satan, for all I care."

Speedy rode on, slowly, through the last street of Segovia and into the plain beyond.

Once down the slope, he cut the cord that confined the hands of Pier Morgan and the latter gasped: "Speedy, I thought that we were finished when we came to the gang of 'em. I thought they'd certainly drag us back to the big house. And if they had . . . eh, what then?"

"Garcías would have burned us alive," Speedy answered. "That's what would have happened. But it didn't happen, old man, and the more luck for us. I thought that the ring would turn the trick, and it turned out that way."

"I've got other things to ask," said Pier Morgan. "But I'll ask 'em after we get on the other side of the river."

It was Pier Morgan who rode the mule across the shallows of the ford. It was Speedy who waded or swam behind until they struggled up the farther bank. There they turned and looked back over the dim pattern of stars that appeared, scattered over the face of the famous river.

Then Pier Morgan said: "Yesterday, I thought that I was ridin' my last trail, Speedy. And today it don't seem likely that I'm really here, on safe ground, and you beside me. You've got through stone walls, and locked doors, and raised the mischief to get me out of trouble. I ain't thanking you, Speedy. Thanks are pretty foolish things, after all, considering what you've done for me. I've used up nine lives, like any cat, and you've kept me on the face of the earth. That's what you've done. But still I'd like to ask you a coupla questions."

"Fire away," said Speedy, beginning to thrum very softly on the strings of his guitar.

"I dunno that I understand very well," said the other, "why you wanted to make this here Garcías so crazy mad at you. You done that on purpose, but I dunno what the purpose is."

"You could guess."

"Yeah, I could guess," Pier said. "I could guess that life was kind of dull for you up there in Sunday Slough. I could guess that you didn't have your hands full, and that you wanted to crowd in a little more action. So you got Garcías practically crazy. You wanted to make sure that he'd get together every man that can ride and shoot and come up to the Slough looking for your scalp."

Speedy chuckled a little. "Garcías can be a pretty dangerous fellow, I imagine," he said. "He has that reputation. But I wanted to have him so blind crazy with rage that he would hardly know what he's about. He'll never rest till he gets at me again, do you think?"

"No, he'll never rest," agreed Pier Morgan. "He'll certainly never sleep until he gets a whack at you in revenge."

"When he comes, he'll come like a storm," Speedy said, "and the first thing that he does will be to get in touch with friend Levine. Isn't that fairly clear?"

"Yeah. That's pretty likely."

"When that happens, I have a chance to scoop him up along with Levine. And then the charge is kidnapping, with you and me both for proofs of what's happened. Kidnapping of a man and taking him across a frontier is pretty bad and black for everybody concerned. I think, if my scheme works, I'll have Levine in for fifteen years, at least. That's my hope. Then I've done what I wanted to do . . . I've cleaned up Sunday Slough and given it a rest."

"All right," murmured Pier Morgan. "I'm behind you every step, but you must carry a pretty steep life insurance, old man."

LEVINE was at the breakfast table. His coat was off. He had not put on the stiff white collar that made him respectable for the day. He had rolled his sleeves. By way of a bib, a large cotton hand towel was stuffed in at his throat. This kept him from the necessity of leaning far forward every time he raised a dripping forkful from his plate. Fried eggs will drip. A ragged half of a loaf of bread remained at his left hand; a tall coffee pot and a can of condensed milk were at his right. The eggs were well flavored by numerous strips of bacon. The precious juices that might slip through the fork were salvaged by using the bread as a sort of sponge. In this way he made excellent progress.

He had a newspaper propped up in front of him, but he paid less attention to its headlines than to the cheerful conversation of One-Eyed Mike Doloroso, who was lolling in a corner of the room. Mike had just come in and made himself at home.

"Have something?"

"Nope," said Mike.

"Slug o' coffee, maybe?"

"I fed my face a coupla hours ago," said Mike. "I ain't a lazy hound like you, what I mean."

"You got nothin' on your brain to worry you, like me," said Levine. "You got nothin' but hair."

"Ain't I got Speedy to worry me, too?" asked Mike.

"Him? Aw, he don't pay much attention to you. It's me that he wants. What's that yowling out there?"

Mike went to the window. "Aw," he said, "there's a coupla dozen poor fools walkin' down the street carryin' a big banner that says J.J.J. for sheriff."

"Close the window and shut the yapping out, will you?" asked Levine testily. "That tramp, I'm kind of tired of thinking about him."

"Yeah," said One-Eyed Mike, "you shouldn't go and get yourself into a stew about him now. You're gonna have plenty of time later on, when he throws you into the pen for life."