RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

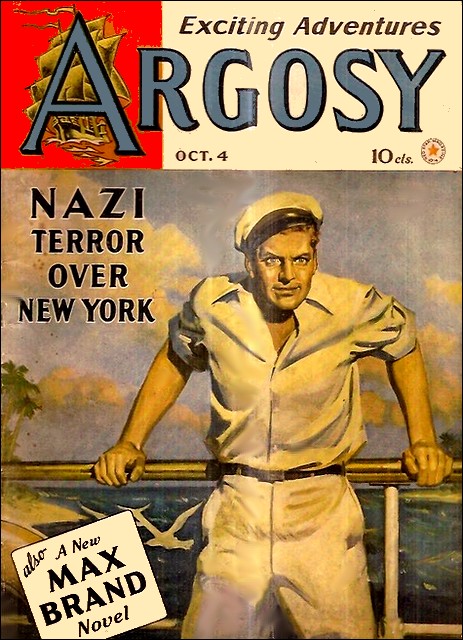

Argosy, October 4, 1941, with first part of "Seven Mile House"

| Chapter I Chapter II Chapter III Chapter IV Chapter V Chapter VI Chapter VII |

Chapter VIII Chapter IX Chapter X Chapter XI Chapter XII Chapter XIII Chapter XIV |

Illustrations 8, 11 and 17 are by S. Maxwell, all others by Ronald Bocking.

TIME once more was standing still for Samuel Kennedy. It had such a habit of pausing, and he with it, that he had gained from the world nothing but a great deal of amusement; in every business enterprise he had been a complete failure. Now he sat on a rock with his hat at the back of his head and focussed his enlarging glass on the silken nest of a trapdoor spider.

Samuel Kennedy.

He had been there for an uncounted period; and he himself could not tell how long he would remain with the sun gathering force towards the zenith and scalding through the back of his shirt.

He knew nothing about the West which he had just entered, but every portion of the world he visited became a wonderland to him. These desert hills, in which nothing had apparent existence except patches of low brush, clinging like smoke to the ground, in reality teemed with life, as he now discovered. In the round field of his glass, the grains of sand showed big. They glistened as though they themselves were a source of light. Small pebbles lay with blue shadows beside them. There was a tiny plant with bristles instead of leaves and a single blossom not a quarter of an inch wide, but the glass of Kennedy showed the blue of the cup, dusted almost to the lips with golden pollen. In addition to the spider's nest with whatever it contained, a lizard as grey and thin as a splinter of rock lay on a stone some ten or twelve inches from the silken door. It was in an attitude of attention, its head lifted, one forefoot advanced half a step, its translucent tail still curved down the side of the stone. For endless minutes it had maintained this posture, studying the huge black shadow and the motionless man above it.

At last it moved, darting two or three inches, pausing, darting again. It left the mark of its tail on the sand, thin as the shadow of a wave in water. In these two or three quick advances it had come much closer to the spider's dwelling. What was the bourn of its journeying, wondered Kennedy. Out of instinct or memory, to what nook was it bound where insects might come within its reach? Perhaps the little blue flower with its cup of gold was the bait which it would use. But here the lid of the spider's house flicked open and a shadow darted from it. By the time Kennedy had his glass trained on the proper spot, the lizard and the spider were twisted into a rolling knot. Sand scattered about them. A little puff of dust rose and shone in the sunshine. In the pallid shadow which it cast beneath, the lizard lay still with the fangs of the murderess fixed in its thigh. The glass of Kennedy showed how they were being driven deeper and deeper. What old Greek was it who spoke of a woman calmly murdering, "like a spider, stabbing and poisoning without malice"? Kennedy shivered. He rose to his feet.

Now that he stood erect, that world of life and death at his feet was removed suddenly to unimportant distance but he had been enriched by one more bit of knowledge, he had stored another picture in the gallery of his brain. If was time now to remember that he was hungry, above all that his throat fairly crackled with thirst, so he took a swallow from his full canteen and started again up the pass. Something more than hunger or thirst troubled him, however. Characteristically he paused to find out what it might be, whether an external object or an unhappy thought; for Kennedy was the very epitome of leisurely action and something in his nature prevented him from doing more than one thing at a time.

It was one of the grey stones at the top of the next low hill that had bothered him, he discovered. A sense of motion had registered on the very margin of his field of vision and in the haze of his subconscious mind. He turned and stared. There was no more movement, but as he centred his attention he was first aware that something watched him from among the rocks and then he made out the head of an animal as grey as the stones. Instantly all was clear in spite of that protective colouration. A wolf sat there not a hundred feet away and surveyed him without fear.

Perhaps the murder he had just witnessed had left a chill in the nerves of Kennedy, but when he saw the beast so insolently at watch within stone's throw, he could not help remembering that he had no sign of a weapon with him except a very ineffectual little pocket knife. He picked up a rock with good, jagged edges. It fitted his hand in the most friendly way and made him feel a little better, yet he could not keep from his mind some of those childhood stories we read of famine and man-hunting wolves. Those are winter tales, but hunger can have as sharp a tooth in the desert as in the snow. He waved his rock. He shouted. The beast did not so much as lower its pointed ears.

Panic jumped up into the throat of Kennedy, but it always was an odd habit of his to try to outface fear. Besides, all logic forbade him to believe what his eyes were seeing. Generations of hunters with high-powered rifles have made the wild animals of the West as timid as birds when man is near. This calm defiance was totally incredible. So Kennedy found his long legs carrying him straight up the slope to investigate. He was by no means one of those fearless athletes who find something in themselves that may be trusted in any emergency. Instead, he was a tall, spare New England type, with the strength fitted close to the bone, and his lean face, habitually smiling in a dream, grew alert only at intervals. It was not reckless self-confidence that sent him up the hill now, but an impulse of sheer curiosity as avid as that of a child. He might be called a random investigator, but he gave to every problem a consideration as patient as science itself.

Halfway to the shoulder of the hill he paused, for he saw a blackened smudge of mud or of dried blood on the head of the beast.

Perhaps this was the explanation. Some crippling injury prevented the animal from moving. Kennedy went on again with more confidence. He was only a few steps away when the creature flung itself towards him without a snarl, with only a silent uncovering of its fangs and a bright green devil in its eyes. The spring of the spider on the lizard was not more swift, but now an invisible hand jerked the beast to the ground. A chain rattled. Through the bristling neck fur Kennedy saw a collar studded with copper.

He was only a few steps away when the creature flung itself towards him.

He drew a long, sighing breath of relief and lighted a cigarette with deliberation. Another little mystery had vanished under an inquiring eye. It was not a wild animal at all. It was simply a dog on a leash whose handgrip was wedged into a rock crevice so that the poor brute could not get free. Kennedy, blowing out smoke through mouth and nose, looked into other details of the situation in a far more relaxed state of mind. In some accident the big police dog had been injured; its master had fastened it here and would return in due time.

Another man would have gone on, now, perfectly satisfied, but Kennedy was a dweller upon detail. The green murder that still shone in the eyes of the dog intrigued him. And now that it began to pant he noticed that the tongue was discoloured and thick. Something else about it seemed strange; he realised after a moment that the oddity lay in the dryness of that tongue. Not a drop of saliva seemed to brighten it.

Now that he had pored upon the central figure, for a time, Kennedy shifted his attention to the rest of the scene. A few steps up the slope appeared the mouth of a cavity, partially masked by brush. When he went to it, he saw upon the sand inside a mark as though a body had been dragged. Furthermore, there was a vague imprint near a stained patch on the ground as though at this point the dog had lain on its side, bleeding. From that place the trail of its footfalls came to the mouth of the cave, but there disappeared.

Kennedy, sitting crosslegged, brooded over the little problem through a second cigarette, for his mind worked slowly, slowly. In a pinch, for quick deductions, he was almost the worst man you could find. His mathematics were not those of a lightning calculator, but rather those of one who deliberates in the terms of a new geometry which contains an extra dimension. He was remembering, finally, that two days before there had been a violent wind-storm; some of the fine dust it carried was still in the innermost recesses of his knapsack. And now he could begin to approximate some conclusions. The dog, it seemed, had been dragged into this cavity and left lying there. At least two days before, it had roused, walked from the cave, and become fastened—by chance or by the purpose of its master—in the rock crevice. The wind-storm had erased the trail it made in leaving the cave. Now Kennedy could go still farther. The only sign of a man's approach was his own trail, deeply marked and shadowed in the sand. No-one had been near this place for two whole days, therefore, and the dog had been caught in the rock by mere chance.

He returned to the consideration of the dog. The blood matted on its head did not entirely conceal a furrow, deeply ploughed from between the eyes to the top of the skull. And here the interest of Kennedy grew again to a fever-point. Very apparently the animal had been shot down, dragged into the cave, and left for dead. And in the world of men, how many brutes are there who will murder a dog? Furthermore, in such a spacious wilderness of sand and rocks, who would bring out a dog upon a leash? The enigma grew wider and deeper. Kennedy, dreaming his way into the dark continent of human impulses and purposes that might have inspired these strange actions, began to smile a little, as a hungry man might do, imagining a table loaded with French cookery. He was deeply content.

It might well be that the savage temper of the dog had caused someone to shoot it. As for this, Kennedy soon could find out. At least two days of bleeding and of heat had starved the animal with thirst. Kennedy took off his hat, from his canteen poured some water into it, and held it at arm's length so that the dog, crouched at the end of its chain, barely could reach it. Instantly the poor beast was drinking. The green left its eyes. Its thick brush of a tail commenced to sweep the ground as it looked up to Kennedy with entreaty. All fear left Kennedy then. The last drop of his canteen finally went into the hat and was gone. By that time his hand was stroking the long, dusty fur. Through the thick of it his finger-tips found the great ribs, one by one. But his mind was reaching back beyond this moment to that other scene, more than two days before, when someone with a careful deliberation had shot the dog down and then, even in this untravelled wilderness, bad chosen to conceal the body. The mere facts were trivial compared with the possible motives and Kennedy was lost in the consideration of them, when the whining of the grey dog roused him. The big fellow, straining at his leash, was pointing steadily into the north-west.

UP through the pass Kennedy was led, his hand on the grip of the leash. It seemed less a trail than a hope that the dog was following, sometimes ranging from side to side, sometimes with lifted head studying the wind. It was love of the master that kept the tail a-wag and the body quivering. As he watched that eagerness the heart of Kennedy began to ache a little, for who was there in this world that yearned to be near him as this poor beast desired the scent, the touch, the closeness, the divine voice and eye of the master? That bullet fired on the hillside seemed more and more like an attempt at murder than the mere slaughter of an animal, and the purpose of Kennedy hardened with every step of the journey as steel toughens under hammering.

Beyond the throat of the pass the country opened. In the canyons among the high hills trees appeared. Even the desert air was altered by almost imperceptible fragrances and gave a sharper, more living breath. But this wider landscape, this more capacious horizon, seemed to baffle the dog. He sat down on his haunches and, pointing his nose straight up, seemed about to howl with misery; but his sides laboured and his throat strained without the uttering of a sound. Either instinct or a strict teacher had taught him to hunt in silence. And after a moment he resumed his search.

He took a much more wandering course now, looping more and more generously from side to side, and pausing on every rise of ground to study again all the messages that came to him down the wind. Kennedy, looking back, saw that he was being drifted still in the direction of the north-west which they had followed through the pass, but he could guess that it was a blind trail. As for himself, he was perfectly helpless except, later on, to make inquiry after a man who had owned a German shepherd dog of this description. But human beings were rare in this sunburnt part of the world, and towns were separated by almost astronomical spaces. It was better to trust to the love of the dog to find the criminal, his master.

They came now into sight of a gleam of water that appeared and disappeared among the hills with a fringing of trees along the banks and green meadowlands in some of the lower places. It seemed to Kennedy that the dog must make a true line for the stream, and Kennedy's own throat was parched by thirst; but the beast kept to his hunt with a passion and Kennedy permitted himself to be led where the dog would go.

It was his nature to commit himself to a moment utterly, and to be swallowed up by each successive event. He could almost disappear in a room filled with people, sitting in some corner where he was least in the way and, with his characteristic faint smile, drinking in all that was said, keeping himself so motionless that nothing about him stirred, for an hour at a time, except his eyes. So now he abandoned all effort to direct the dog, but let himself be drawn mindlessly here and there. That which he studied, that in which he lost himself, was the headlong devotion of the animal. He thought of love itself, calmly, for it never had come close to him; but he could not fail to realise that it was the mainspring which turns men into heroic patriots, brainless fools, high poets, tiresome bores. It is the one earthly impulse which must exist in heaven also. As for himself, there had been a few stirrings of the blood and the spirit when he was with women, but he always was too busy recognising the beginnings to permit them to develop. In a sense, he destroyed his life by too much thought, as a plant may be destroyed by too much sun. Now he studied blind love in the struggles of the dog to find his owner's trail.

They came to a hill beyond the top of which the heads of trees were showing, beyond which also he heard a music of falling water that reminded him violently of his own thirst. The sound, therefore, gave him both pleasure and pain.

The hill was composed chiefly of a brittle, blue shale, noisy underfoot except where a little soil had collected, here and there, and permitted grass to grow. To the left, a small landslide had dropped into the narrows of a canyon, filling it several feet deep with a rubble that held several large boulders. More large stones appeared along the top of the hill, a semi-circle that looked like part of an old Indian fort. He barely had noted these details when the dog almost wrenched the leash from his hand. It began to run with nose to the ground, uttering a small, moaning noise of unutterable excitement and joy, along the very edge where the slide had commenced and where a few of the boulders had been displaced.

Back and forth, the dog hurried, studying the place so carefully that Kennedy examined it also. He even took out his enlarging glass and grew minute in his search, but all that he could see, where the boulders had been rooted, were a few marks in the rock as though made by the narrow end of a pick.

The dog lifted its head, studied the wind with eyes almost closed, like a connoisseur studying the bouquet of a wine, and then made a few tentative steps down the slide. What it started Kennedy completed. The slope was so sharp and the shale so crumbling that he found himself skidding and floundering down to the bottom of it, dragging the dog after him. There he paused to take breath, leaning on one of the large, fallen stones. But this wealth of loose, workable ground seemed to excite the dog as soft garden soil often will do. He began to scratch furiously, as Kennedy dried the sweat from his fore head and prepared to go down the canyon. A formidably deep growl brought his attention again. A shallow trench had been scraped out by the dog and it exposed some buried animal, or at least a tuft of brown hair from which the wind began to blow the dust. Something about the lightness of that hair troubled Kennedy. He leaned to look at it. He gripped a heavy stone beside the blown fur and pulled it out. The pocket he had made received a little run of the pulverised shale and as it flowed away, Kennedy saw exposed beneath the hair a human forehead, eyes half closed, and the face of a man as far down as the bridge of the nose. There was no sense of death. It was rather as though the fellow were standing there beneath the debris of the landslide lost in deep thought from which presently he would look up.

In a few moments Kennedy I had drawn up the dead man and laid him on the top of the broken shale. There was some hundred and eighty pounds of him. He was perhaps 30, a well-made six-footer dressed in a linen suit, a handsome man who seemed, by his smile, to have discovered that death was amusing, but a little contemptible. A deep abrasion on the right side of his head showed that he had died quickly, but since his face was turned in that direction he seemed at first glance quite untouched. The wound, the half-closed eyes, the smile brought up in Kennedy a rising horror; he half expected the dead to rise, to be at ease, to speak cheerfully, to go among other men, unconscious of that gaping hole in the side of the head. And all the while the sun blazed like an angry eye from a broad golden seal ring on his hand.

He found the very stone which had dealt the wound, its ragged projection on one side made to give the blow and covered with the red coagulation. On one side of it, as Kennedy surveyed it with his enlarging glass, he found a slight fuzz adhering, and his fingers plucked away a little quantity of this. He commenced to roll it together as he looked back to the dead man.

Here, then, was the master. No, for the dog kept the chain of his leash taut, trying to pull up the slope, and bringing down another shower of the crumbling shale. But there was something more important than the dog's trail, now. Kennedy led or dragged him down the ravine's windings.

A slight stickiness on his thumb and forefinger made him aware that the fuzz he had picked from the side of the rock had turned into a little, compacted thread. This interested him. It indicated that the fuzz had come from a waxed surface. He took a page from his notebook, put the thread inside it, and replaced the folded sheet in his book. It might have a voice and speak for itself, later on. He continued up the draw with the dog. He had not gone a hundred steps before be came into the wider valley through which the stream ran, stopped by a mill-dam that backed up a bright-faced little wheel over which the water above the dam poured uselessly except to keep its voice alive in the landscape. But the mill was only one of a number of sheds and barns which grouped like a little village around the central building. This was an old, rectangular affair completely surrounded by two-storey verandahs and painted white. It looked like an old Southern plantation house in an absurd setting, for the backdrop was of gaunt blue mountains and the foreground was the riot of Western hills, pale under the sun. A freshly-painted sign above the entrance to the main building announced that this was the "Seven Mile House."

"SEVEN miles from what?" pondered Kennedy. "Seven miles from nowhere!"

He considered this scene with his customary leisure until he had noticed the dim presence of what might once have been well-defined road passing down the valley. It wound out of sight, perhaps towards the ghost of a town that once had been seven miles away; or there might still be, in the distance, some stumbled-kneed old crossroads village. At least there had been nothing large enough to show on even the most detailed map. It seemed to Kennedy that he had entered not only a new country, but a removed section of time. When he started towards the Seven Mile House he would hardly have been surprised to see a figure in hoop-skirts come out through the door.

The dog in the meantime found something ardently satisfying on the ground among the thousands of footprints. He wavered for a moment back and forth, then took a straight line to certain obscure pick-marks upon the boulders which seemed to indicate that they were artificially loosened, perhaps artificially set rolling to bring down the landslide. If that were true, a. murdered man lay now in the ravine; and these foot prints which the dog followed so earnestly were the trail of the murderer.

The very soul of Kennedy warmed to this suggestion. Concerning the master of this dog he had had certain pungent questions to ask long before; the questions now would deal with something far more important than attempted dog-murder. There grew in Kennedy an ironical hunger to see this great brute fawn at the feet of his master or his mistress. It would be a betrayal through blind love.

Perhaps he was a little too full of these thoughts to keep his grip firm on the chain, or else the scent of the master grew strong enough to give the grey dog an added strength. At any rate, near the verandah of the tavern the big fellow burst suddenly away from him and bounded up the front steps with his nose still down. The chain, flying to the side, crashed against the open door; then the dog disappeared in the dim interior, his nails making mud scratchings on the floor. Kennedy hurried after. A woman screeched. The screech settled into a high scream that made goose-flesh run up the spine. He thought of the lizard and the spider-fangs; but that had been silent torture. There was no cessation in this screaming it seemed to him. The voice struck high C, and stayed there.

He ran across the hallway. It was large, shadowy with coolness that washed like water over his hot body, and descending into the well of the hall he saw the curve of a white stairway with a red carpet running up the treads. He saw himself, also, gaunt and forward leaning, as his image ran across the face of a big mirror. Except in bad dreams, be never had seen himself before so clearly. And blundering into the adjoining living-room, he found a white-haired old lady plastered against the wall in a corner with her arms rigidly stretched above her head and her eyes shut tight by the violence of her yelling. In fact the grey shepherd looked bigger, more wolf-like than ever, within the boundaries of a room. Now he was sniffing and nosing among the cushions of a davenport at the end of the room. Kennedy repossessed himself of the chain.

He found a white-haired old lady with her

arms rigidly stretched above her head...

"Madam," said Kennedy, "when you care to stop screaming, will you tell me who generally sits at this end of the davenport?"

The old lady still yelled, but now it was with her eyes open, and when she saw the wolf turned into a dog her screech slowly faded like the noise of a baby which runs down the scale and dies away as it sees the bottle. Other footfalls coming from a distance, perhaps were bringing thought of comfort and safety to her.

"Oh heavens," she said, staggering towards a chair, "do something—take that beast away—I'm dying—I can't breathe—."

"Let me reassure you, Madam," said Kennedy, "your colour is very good, and this little excitement, at your age, may take the place of exercise. You will eat a very good dinner this evening."

A Latin face, dark beneath a cook's hat, had appeared at the doorway, looking in cautiously before leaping at danger. Past him hurried a pretty woman of 27 or 28. She wore an orange-coloured dress of some sheer fabric with cool patterns of heavy green yarn stitched on it. Her dark hair she wore knotted in a classical chignon to make her more beautiful than ever, in Kennedy's opinion, and her haste in coming, like a soft wind, blew the dress against her young body. Kennedy remembered, suddenly, to remove his hat. This permitted the sweat to run down his face, but his spirit, was pleasantly cooled by what he saw.

"Dear Mrs. Lancaster," the lovely lady was saying, "what on earth has happened?"

"Do something for me," said Mrs. Lancaster. "l can't breathe... and my heart... Oh, Julie Vernon, I'm dying... that dreadful monster sprang at me..."

Julie Vernon turned to Kennedy. He was enjoying the sight of her so much that he could not help smiling. The dog, in the meantime, was trying to get to other places in the room, following a living scent, and since he was hard held, the rug at which he pawed began to rise in large waves. It was characteristic that Kennedy had almost forgotten the dog and everything else in order to enjoy and study in detail this picture of a pretty woman.

"Orange and yellow-green," said Kennedy, "is one of the useful contrasts, don't you think?"

She spared a glance for her dress and another at Kennedy before she said, quietly: "Will you take your dog out, for a moment?"

Kennedy took his dog out. There was no hurry. Resident in this tavern, he now was assured, was the murderer, and he could trust the nose of the dog to find him out. From the hall he heard the whimpering noises of Mrs. Lancaster as she was led or carried up to her room, but Kennedy employed himself in enjoying the features of the scene before him. Yonder at the top of the hill of blue shale the dog had found the trace of his master; here by the tavern he had found it again. There on the hilltop the hills stood up like bright islands from the sea and the sun was throwing fire on the eastern mountains. From the corner of his eye he saw Julie Vernon come out on the verandah.

He turned to her, still smiling. She seemed incurious. Her manner was definite and a little cold.

"I am Samuel Kennedy, Miss Vernon," he said.

The dog, finding a new scent on the ground, gave him a sudden perk that almost unbalanced him.

"Do you usually turn your dog loose in an hotel, Mr. Kennedy?" she asked.

"I have offended you," said Kennedy.

"No," she said, "I was curious. I just wondered."

"The truth is that he is not my dog," said Kennedy.

"Only an acquaintance?" she suggested, and her smile turned up the corners of her mouth like the smile of Vivien Lee.

"You know the grey-blue davenport in there?" asked Kennedy.

"Yes," she answered.

"I wonder which of the guests is most in the habit of sitting there?"

"I haven't the slightest idea. Why?"

"Because the person who does is apt lo be the master—or the mistress—of this dog."

She did not seem particularly interested.

"No-one has brought a dog to Seven Mile House," she said.

"The very point I have in mind," smiled Kennedy. "Who started with a dog towards Seven Mile House and wound up without him?"

She interrupted the course of his inquiry.

"Do you know that your dog may have cost me Mrs. Lancaster and 20 dollars a day?" she asked.

"I'm sorry your prices are so high," said Kennedy. "I hoped to stay here for a day or two."

"I hope that Mrs. Lancaster doesn't die of shock," said Julie Vernon.

"She will not, you can be sure," said Kennedy. "She needs only a little attention."

"Are you a doctor?" asked Julie Vernon.

"No," he answered.

"I thought not," she said. "What attention would you suggest?"

"A drink of hot, aromatic tea. A cold towel on her head. A hot-water bottle at her feet. And a caressing voice to speak to her softly. This incident will give you such a chance to baby her, Miss Vernon, that she will want to stay with you for ever, even at 20 dollars a day. Which brings me back to my point. What is your lowest charge for a man and a dog?"

"We don't allow even lap dogs in the hotel." she said.

"Don't you?" he asked. "What harm do they do?"

"It's the rule," she answered.

"So there is no place at all for me here?" he asked.

"There could he in one of the cabins," she said.

She pointed at several little out-buildings that once might have served varying purposes, from blacksmith shop to smokehouse, in the days when Seven Mile House first won its name. But now they were brightly painted, with patches of lawn near their front doors and flowers blooming here and there.

"Are there stoves in them?" he asked.

"No," she said.

"At this altitude," said Kennedy, "the evenings will be very chilly, and the nights more so."

"Yes," she agreed.

"It is quite delightful," said Kennedy, "to meet such a frank hostess. What is your cheapest price?"

"Five dollars," she said.

His long face fell and grew still longer.

"Or, considering you have the dog," she said, "we might make it three."

"How amusing, and how pleasant," said Kennedy. "Thank you very much."

She laughed, but Kennedy only smiled.

"By the way, there is something else, very serious," he told her.

"More serious than Mrs. Lancaster?" she asked.

"Oh, yes," said Kennedy. "Up the ravine there, just beside this tavern, not a hundred steps from this spot, there has been a small landslide."

"Yes, Mr. Kennedy," she said. "We heard it last night and went to look at it by moonlight."

"Do you remember just when it was?" he asked.

"Just ten minutes after eight," she said. "Why?"

"And could you tell me where everybody in the tavern was at that time?"

She made a pause, but she had grown used to him already as an eccentric.

"I wasn't here myself, but nearly everybody else was on the verandah smoking after dinner," she said. "Why?"

"Because buried in the landslide I found a dead man," said Kennedy.

"Because buried in the landslide I found a dead man," said Kennedy.

THE cook, two stable-boys and a farmhand brought in the dead body. They used a door for a stretcher and Julie Vernon walked beside them. Kennedy and the dog brought up the rear.

"What shall we do? Where shall we take him?" asked the girl.

"To a cool place, I suppose," said Kennedy. "And then let the police know about it."

They took the body to the toolshed. Julie Vernon brought out a sheet to cover the man after she had sent one of the stable-boys riding across the hills to carry word to the police and to bring back some sort of a conveyance to take him away. She seemed surprised to find Kennedy there.

It was a rattletrap of a shanty with cracks a finger's breadth broad that let the westering sun stain the earthen floor with yellow stripes. It housed saws, picks, shovels, long spades to turn up deep garden soil, rakes, coils of hose, hammers and sledges and mauls, axes and a few sawbucks, across two of which rested the bier of the dead man. Big spiderwebs, loaded with dust, sagged from the ceiling and the rafters. Kennedy forgot these things as he sat on another sawbuck with the restless dog at his feet and made notations in his book. He had an excellent memory, but he kept it razor-sharp with these continual notes. The dead man, he had learnt, was one William Harrison, a mining promoter who made headquarters in the little cross-roads village of Canyon Gap, some ten miles to the north. Here he picked up and sometimes grubstaked prospectors to run legends and rumours to the hard ground of fact. On occasion he went off to the big cities to show his ore samples and tell his tales of gold. He had come to Seven Mile House five days before, on foot. The old road was blocked by a hundred slides, since the early days, but guests for Seven Mile House generally wrote in long ahead and were met with horses and pack mules at the nearest stop on the motor bus line. Almost no-one from the surrounding district could afford the prices of Seven Mile House in its reincarnation under the management of Julie Vernon, but men who wanted excellent fishing, deer hunting in season, or the pleasure of mountain trails, were tempted by this remote tavern. The very name of it spelled a certain romance. Ladies who wanted long, long silences; writers who had waited in vain for inspiration in cities; artists who wanted to try on canvas the impossible distances and colours of that Western country, were apt to hear of Seven Mile House and chance its remote charms. For three years Julie Vernon had kept quite a full house, winter and summer. She laid a good table, provided good riding and pack animals, excellent guides, and charged three prices for every service. People who serve the very rich learn to do so without conscience; Julie Vernon had forgotten her conscience.

So William Harrison had walked across eleven miles of tough going and appeared at the tavern, five days before, and it was rather surprising that a man of moderate means should have chosen such an expensive resort. Yet it was not the first time he had come, and that was why information about him from people in the tavern came so easily to Kennedy. He noted these facts in his notebook, but what he particularly noted had nothing to do with the past of the dead man. It concerned itself with the rather odd behaviour of Julie Vernon when she came in sight of Harrison's body.

"Fear of more than death," was the phrase that Kennedy selected.

The dead body in itself was of course enough to upset the nerves of the girl, but there had been something a little more than mere physical shock when she stood over Harrison. The shadow from the western side of the ravine had left her standing in sunshine, but covered the dead man with filmy darkness, so that he seemed to be lying in clear water. And after that first natural recoil there had seemed to be in her, under the examining of Kennedy, something like a quick dread of the eyes around her, a startled glancing over the shoulder, and then a hard, stern control which she fixed upon herself. To Kennedy these reactions were at least kindred to guilt. And though it was fixed in his mind that the owner of the dog was the actual killer, he could not he sure; besides, more than one hand can be engaged in the same crime.

These were his thoughts and his notations as he sat on the sawbuck in the toolhouse, and the sense of guilt in the woman gave her to Kennedy a sort of added attraction, like piquancy in food. When she came now into the tool house with the sheet, she made an abrupt pause.

"Still here?" she asked.

She made an abrupt pause. "Still here?" she asked.

"It's an opportunity, you know," said Kennedy, looking up at her with his smile, and searching casually but deftly among the thousand shadows and lights which compose the human eye.

"An opportunity?" she repeated.

Without waiting for his answer, as though already sure that it would be merely one more oddity among a growing collection, she drew the sheet up over the body of William Harrison. She tucked it in about the feet and shoulders, oddly like a mother caring for a child at night; but here the sheet covered the head as well. It was cloth worn thin by much laundering and fitted the features so closely that instead of hooding the face it merely seemed to turn it white. The very likeness came through in a way, as when a sculptor has roughed out the stone, but not yet come to the detail.

Such things as this always interested Kennedy. He stood up, the better to look at this dead man turned into a statue, as time often makes our great men into heroic monuments. The fingers of Kennedy itched for his notebook.

"Yes, an opportunity—this chance to sit here," he said. "We can't make friends with death, I suppose. But we can try to get used to it."

She looked at him with something between a smile and impatience.

"You talk rather like a book," she said.

"Do I? I'm sorry," said Kennedy, from the heart. He had heard this before, and it abased his eyes with introspection. Glancing down in that way, he noticed among the picks which leaned against the wall one which was not rusted like the rest. The narrower point of it was cleaned by recent use and just inside the point there was a little lump of blue dust.

He remembered the blue shale of the landslide, the boulders which must have been set rolling to cause it. This was undoubtedly the very tool which had been used for the murder. What perfect timing, what invention, what brain the killer had used so that his hands might seem to be clean!

He looked up at the wide, intellectual forehead of Julie Vernon.

"I'll be going over to my cabin," he said.

"Dinner at seven, or seven-fifteen," she said, briskly. "There are cocktails at a quarter to seven in the lounge."

He stood at the door, holding it open for her. She seemed at first about to protest. Then, as though this gesture were a command she did not know how to refuse, she went through the door ahead of him, but there remained in Kennedy a distinct impression that she had wanted to stay behind him, she really had wanted to be alone with the dead.

BEFORE dinner he fed the grey dog on the narrow brick terrace behind the kitchen and Maria the kitchen maid stood by. She was a voluble creature, with the bloom slightly faded and a small, dark harvest beginning to appear on her upper lip. Words flooded readily from her, and as Kenned fed the dog he asked questions. He did that feeding by hand, some three pounds of ground, raw meat. He held it in small portions on the flat of his palm. At first the great dog sat with his head turned, his eyes averted, as though he had forgotten, in his scorn of all human beings except one, that there was such a thing as food in the world. At last, when the drool from his mouth already betrayed him, he made a snakelike movement and clipped the meat neatly out of the hand of Kennedy. It was as though the steel shears of a machine had snapped up the food. Maria had screamed, for she had expected, she said, that the hand of Kennedy would be taken as well as the food it held. However, the dog was as accurate as a butcher's knife. He accepted every mouthful in the same way, except that towards the end he no longer turned his head away and there was even a lifting of his eyes, furtively, to the face of Kennedy between bites.

It was not a quick process, and in the meantime Kennedy learnt a great deal from the garrulous Maria. Of course she was willing to talk at great length about the death and all the circumstances connected with the fatal landslide. Kennedy, adding up her names and places, discovered with unhappiness that there had been twenty persons as guests or employees of the tavern, that evening. William Harrison was the twenty-first person. However, most of the twenty could be accounted for.

The gardeners all were at work by lantern and moonlight repairing a break in the dam, for fear the water in the swimming pool would escape before the morning. The cook and Maria were in the kitchen, the chambermaid-waitress and the waiter were busily serving coffee and brandy to the guests on the front verandah. These guests were nine in number after William Harrison left them and took his cigar up the canyon for an after dinner stroll. Alexander McDonald stood at one end of the verandah, singing between puffs of his cigarette. The rest sat with their coffee. Three people were not on the verandah. They were Camilla Cuyas, that Spanish refugee who wore the lovely jewels, Julie Vernon, and Daniel Fargo, writer and ex-cattleman. Julie and Fargo—it was an accepted fact that he was trying to marry her—were out walking together. Camilla Cuyas had claimed that she was in her room, too tired to come downstairs even when she heard the roar of the landslide. Everyone else had run to look at the place where the rubble had piled in the ravine. Out of all of this flood of information, Kennedy, docketing names rapidly, decided that suspicion certainly could fall only on those who were not present and accounted for. That left only three names. He listed them in his notebook, afterwards, in the following fashion.

"Julie Vernon, certainly possessing a strange interest in the dead man, with hints and small motions of guilt about her.

"Daniel Fargo, blind with love of Julie, an ex-cattleman with violence in his past life. Perhaps the owner of the dog. For something connected with Julie he readily would have killed Harrison.

"Camilla Cuyas, a girl apparently full of moods, sometimes very dark ones. She is unhappy and never has forgiven the world for her loss of a home, etc. She was much with Harrison during his stay here. Jealousy?"

In his cabin, after feeding the dog, Kennedy finished making these notes. Even more interesting, to him, were the facts he had gathered about Harrison. Before being a promoter of mines of dubious value, he had been a lawyer with an Eastern practice. He was a handsome, alert fellow, self-confident and obviously a practiced hand with women. He had been constantly with the two beauties at Seven Mile House, Camilla and Julie. He was the sort of a character with a dozen handles by any of which hate could take hold upon him.

Kennedy finished his notes in haste. He was amused to find himself in the role of detective and this very list of suspects he could remember to have found in detective stories. He wished that he had more than three. Yet after all he had a very unfair advantage over all fiction detectives—he had at hand an infallible means of discovering the criminal who was responsible or partly responsible for the death of Harrison. He had the grey dog. The moment it fawned on any of these people the mystery was ended. The dog in fact was his main focal point of interest.

It roved through the little cabin, now, sometimes rearing to look through the window, sometimes pausing to look into the face of Kennedy with grieving, impatient eyes, full of speech. There was not one instant of yielding to familiarity or affection. The love of this beast had been given once and for ever. When Kennedy ordered it to come or go, or sit or lie, it paid no attention or else threw him a look as though it never had heard human speech before. In five minutes, however, this mute instrument would be pointing the way to the gibbet for someone in Seven Mile House.

He put it on the lead again and went outside. In the cabin the rushing sound of the water over the dam had given him the sense of a strong and steady wind blowing down the hills. Actually the world was still and the stars sparkled like frost in the sky. Even without a breeze the smell of the pines made breathing a delight.

He went around the back of the tavern. It leaned right against the hill, so that the first verandah was absent, here, and from the edge of the second verandah, in several places, it was merely a step to the sharp slope. He climbed up among the trees and found himself once again at the crest from which the landslide had descended. The moonlight was bright enough for him to see the debris in the valley and a shadow marked the place where he had drawn out the buried man. Far away, mountains retired like clouds in the moonshine.

Certainly every soul at the tavern not present and accounted for was worthy of suspicion, even Camilla Cuyas. From her room, she could have crossed the verandah, stepped on to the hillside, and reached the crest in sixty seconds, while Harrison, leaving the front of the tavern, would have required three times as long to follow the windings of the ravine until he came to the narrows of it. Sixty seconds up, and less than that back to the tavern for Alec McDonald, for instance. Julie and Daniel Fargo, of course, could have posted themselves at their ease. But the time had now come to use the dog for definite action. Kennedy rounded Seven Mile House until he was under the windows of the lounge. It was a large room with a big, deep fireplace in which now a pile of logs a foot in diameter were burning. Julie Vernon kept the other lights dim so that the yellow of the flames would give a flattering light to the ladies. It was cocktail time. Julie Vernon herself passed titbits. The waiter was on hand to serve the drinks, but most of this was done by Fargo. The possessive attitude of partnership was not the only means of identifying him as Julie's preferred suitor. The big dark man kept his eyes drifting after her whenever she moved. He looked as remote from this little party as an eagle sitting on a crag above busy little fishhawks. It was easy to believe what Maria had said about him and his horses and his guns and his stern ways.

It was even easy to identify, from Maria's chatter, the guests who were unimportant to Kennedy, such as old Mr. and Mrs. Gerald Bowman, starched little figures in one comer pretending to drink a glass of sherry apiece. They were brown from the outdoors where they painted tremendous landscapes every day. There was Dr. Geoffrey Lewis, as fat as a toad and as ugly, Harvey Dunton, the lecturer, talking with professional gestures as though from a platform to Christopher Mills, who had travelled the world round and round and picked up nothing but names of places, that peculiar mental bric-à-brac which makes some idiots feel rich. Mrs. Martha Lane, who also painted, was a woman with a good, tanned, middle-aged face, and she was making compassionate conversation with Hallowell Johnson, already stupid with drink. All that his millions had brought him was a bleared eye and a thick-tongued ability to talk about Rhine wines.

None of these people mattered to Kennedy. He kept watching Julie Vernon and Daniel Fargo. Fargo was the man for him; and yet he remembered that, in detective fiction, at least, the first suspect was rarely the guilty fellow. The other two suspects were at the piano. Alec McDonald singing Italian popular songs and Camilla Cuyas accompanying him on the piano. It seemed interesting that the four under shadow were coupled in pairs. She was not quite as attractive as Maria had led him to expect; a bruised look of sleeplessness about the eyes detracted from her, but she partly covered this with a Latin vivacity which kept her smiling. Alec McDonald was another cheerful soul, but his good will seemed to come from the heart, not inherited manners. He was not fat, but rather plumped over and rounded by excellent living that kept his cheeks pink. He sang very well, rolling out his words with the true Italian "r" trilling through them. He loved his own singing, giving himself blindly and happily to the high notes, but able to look about and smile and nod his sympathy with anyone who showed appreciation during the ordinary course of a song. He was the sort of a fellow who made a party go. Not even little Gerald Bowman seemed so incapable of crime as this fine figure of a man, but the suspicion of Kennedy suddenly switched from Daniel Fargo to the singer. He began to suspect McDonald violently. A man with such a genial exterior, if there were real evil in him, would be a devil indeed.

He lifted the forepaws of the dog until the great grey head was above the level of the window sill and it could see everything inside the room. There was an instant convulsion of the shepherd. Recognition of his owner came upon him like an explosion of joy. Before Kennedy could catch hold on the chain again, the big fellow was off and away from him, scattering sand and gravel as he dashed around the corner of the house.

Recognition of his owner came upon him like an explosion of joy.

Kennedy followed as fast as he could. He was furious. He had intended to bring the dog to the door of the room and mark the sudden stroke of agony of apprehension in some face. He had intended to loose the shepherd then and let it kiss its owner to death, like an innocent Judas. But this drama was stolen away from him. He would arrive only in time to see the culprit spotted. The recognition scene itself was lost to him.

As he bounded up the steps of the verandah and hurried into Seven Mile House, he heard an outbreak of feminine cries of terror. When he reached the lounge the room still was in commotion, but instead of finding the dog at the feet of someone, it lay in the farthest corner as still as a stone, its head lifted, the blazing excitement of its eyes fixed on empty space!

JULIE VERNON was more than a little angry. If she had had a liking for Kennedy it was gone now. She said sternly: "Mr. Kennedy, you must know that this can't be allowed. If you're amusing yourself in your own peculiar manner..."

"Oh, Julie Vernon," said McDonald, "don't be hard on a poor devil whose dog gets away from him!"

Mrs. Lancaster, flushed and happy with two cocktails, began to hiss dreadful things about the dog and the man to her nearest neighbour.

"He's not my dog, you know," said Kennedy. He looked calmly about him and added: "He came in here as though he were on the trail of his owner. I wonder who it could be?"

He scanned every face among his four suspects, but gathered not a whit of harvest.

"Please take him out," said Julie Vernon.

"I'd like to," said Kennedy, "but I've only known him half a day, and he looks dangerous just now, don't you think?"

"Come boy! Here boy! Here boy!" called McDonald loudly, slapping his knee.

The dog still stared at some fascinating emptiness in space. McDonald shrugged his shoulders and made a gesture of surrender.

"The dog doesn't speak my language," he said, and laughed.

For all his bigness and sleekness, he seemed rather one who had to have his hands occupied. These fingers of his automatically produced a ball of twine from a pocket and while he watched the dog and the others he made the twine, with a noose in the end of it, jump up and down and spin like the rope of a well-trained cowpuncher. The picture of this stuck in the mind of Kennedy because it was done without a thought and yet there was a good deal of skill involved.

Others were coaxing the big shepherd. Daniel Fargo went the closest, holding out his hand very near until the beast uncovered its fangs with a silent snarl.

"How noble and how proud and how savage," said Camilla Cuyas. "Big one—attention—venga!"

The dog, first jerking up its head as though in surprise, rose slowly to its feet.

"Ah, good! It is really your dog?" asked Julie Vernon. "Do you own it?"

"But I never saw it before!" cried Camilla.

"Look out! Look out!" exclaimed someone. "I think that brute is dangerous."

For it was crossing the room towards Camilla as though it were stalking a bird, lifting up its feet one by one and putting them down with a catlike caution as it glided forward. Either it meant mischief or else it was being drawn forward against its will by some extraordinary compulsion. Camilla Cuyas uttered a faint screech and fled behind a table and here Kennedy, who felt that he could not pretend fear of the dog any longer, caught up the chain that dragged behind it. He told everyone he was very sorry and started to leave the room. At the door he paused.

"Do keep the beast out," Julie Vernon had said.

He answered, turning: "I'll do my best. But you can understand how it is. He's found his owner and he'll want to return."

"Oh, but I'm not his owner," exclaimed Camilla.

"Perhaps not," agreed Kennedy.

"But there's not a single person in the room that he'll come to," shrilled Mrs. Lancaster. "Except that poor frightened child there."

"However," said Kennedy, "a very well-trained dog can be ordered by a whistle or a word or even by a gesture, I've heard, to stay at a distance. There's no doubt about it. Through the window, there, he recognised someone in this room. And then be broke away from me. Can't you all help me in trying to find out who might possibly have owned a dog like this—and then shot it down—and left it for dead yonder in the hills?"

He went on out, leaving a dead silence. Then a rising buzz followed as mutual suspicion entered that room, like bees coming out of a hive to do their hunting. There might be some danger to him, he felt, in announcing himself so frankly; on the other hand if he kept the dog quite unlinked from the trail of the murder, perhaps he would be better off in the end; and this seemed to be a case in which many heads might be better than one. If there was anything that malicious questioning could bring to light about a past ownership of dogs, in all that company, he felt reasonably sure that he would hear about it before very long.

The shock and the bewilderment of failure still accompanied him back to the cabin. He had been very sure, when the dog struggled away from him at the window, that he was on the very verge of learning everything. Now it seemed that his ace of aces was not a trump at all, and the dog might be of not the slightest use to him. He would have given the very breath of his nostrils to know what unseen signal from the owner bad sent the big animal to crouch in a corner.

In the cabin, he closed the shutters of the window and locked the door to make sure that the dog should not escape. And as he turned the key, he heard the scraping of the nails against the door inside, almost as high as his head. He found in the night around him a new presence that quickened his pulse a little and created thin electric tensions all through his body. He felt at first that it was something he was hearing in the fall of water over the dam; and again it seemed to Kennedy that something odd was in the stars above him, but when he looked up they were the same dim frost across the sky with bright icicle gleamings here and there.

He was almost at the entrance to Seven Mile House again before he realised that it was fear which followed at his heels and waited before him behind the shrubs. No amount of plain thinking could have disturbed him or taught him as much as this, but now he realised that someone in the room where the singing went on again so cheerfully was now his enemy, an enemy with one murder already scored and therefore ready, in an emergency, to take the same desperate step. He breathed deeply a few times, using the diaphragm, and yet he still felt a sense of breathlessness as he entered the tavern. Even as be passed through the lighted rooms, there remained the sense of someone peering at him through the doorway behind and of another waiting for him just beside the next threshold. In this way he came again to the lounge.

There was a slight pause in the conversation when he appeared. But Alec McDonald, his head back as he took a hearty high note which sobbed an adieu to "Napoli," kept right on with his song. The talk resumed, softly, out of respect to the singer. And Julie Vernon came to him with a smile and a cocktail.

She offered it to him on a tray, with some bits of toasted cheese and paprika on small crackers.

"It's an Old Fashioned," she said. "You look as though you needed something strong, Mr. Kennedy."

"Thank you so much," he said. "The dog is a brute to handle."

"Isn't he?" she agreed. "But don't you think you've made some of the trouble for yourself?"

He grew conscious that there was a change in her. She kept on smiling, but her eyes were colder than anything he could remember—as chilly as the stars which whitened the sky this night.

"Trouble?" he asked, wondering over her and yet searching her at the same time. "Do you really feel that I've made trouble on purpose?"

"No. I don't suppose you intended it," she said. She laughed a little, a fine crystal, chilling sound. "But you're always so frank, Mr. Kennedy, aren't you? Was it just being frank when you asked everyone to help you find the owner of this wretched dog?"

"It seemed a natural thing to do," said Kennedy. "I do want to find out, you know."

"So you simply tell my guests that someone among them is a beast who would shoot down his own dog and leave it for dead in the hills?"

"I hadn't thought of it that way," said Kennedy. "I was simply trying to be direct."

"But are you ever entirely direct, Mr. Kennedy?" she asked.

"Oh, I see," he said, "you wish to be a little rude."

"Not at all," she answered. "After this odd performance of yours, I wouldn't be surprised if I had an empty house inside the week. Let me be direct myself. Will you let me ask you to leave Seven Mile House in the morning?"'

"Yes, certainly."

"I'm so sorry," she said, still smiling, and turning away from him.

The song of Mr. McDonald had not yet ended, but Camilla Cuyas, as she ran through a final flourish of the keys, looked up under her brows at Kennedy with such a bright, steady malice that he remembered again how he had felt in the open night, when fear came to stand beside him.

DINNER would have been a difficult thing for Kennedy to sit through if an ordinary type of man had been inside his skin, so many hostile eyes were on him, but even this hostility was something for him to observe and to study. Above all, Julie Vernon, her man Fargo, and Camilla Cuyas had no use for him. Fargo, his head high, his eyes challenging, seemed ready to break out at him at the first opportunity. No-one talked to him except McDonald. Kennedy was grateful.

McDonald said: "What do you do with yourself in the world, Mr. Kennedy?"

"What would you say?" asked Kennedy.

"I'm no judge," said McDonald. "What do other people say about you?"

"They say that I've studied too many things and know too little about any of them, geology, or ornithology, or architecture, or history. As a matter of fact, they accuse me of taking more leisure than I can afford. I haven't anything that would rate as a passion, except travel and detective stories."

One or two people smiled. No-one laughed.

"Maybe he's been in your Italy, Mr. McDonald," asked Dr Geoffrey Lewis.

"Oh yes," said Kennedy. "I brought away a part of it, too."

"Oh, did you? What part?" asked Mrs. Lancaster.

"All I could carry in my head," said Kennedy.

"Oh, is that all!" said Mrs. Lancaster, relaxing. "What does that amount to?"

"A lot of things," said Kennedy, with his smile. "The curve of a gondola's prow, and the gondolier's voice bellowing at the corner of a canal. Dante's house in Florence, a crooked street behind the market, rain over the Campagna, pigeons in Siena, a wine shop in Ostia, a magnolia tree blooming at Como, and Judas kissing Christ in Padua."

"I thought you might be a collector," said MacDonald.

"Oh, I am," said Kennedy in his gentle voice. "I collect all sorts of things that don't have to go into trunks. There's no use packing and unpacking all the time. And as the play says, in the end you can't take it with you."

"I see," said Camilla Cuyas, in a voice as dry as her smile was bright. "A moral philosopher, Mr. Kennedy?"

"Not at all," said Kennedy.

"I got to Italy once myself, on a cattle boat," said Fargo. "But all I found there was sour wine and headaches. Anyway, I learned enough of the lingo to ask my way around but I never found what Kennedy saw."

"And what are you interested in mostly now?" asked Julie Vernon, absently.

"Murder," said Kennedy. He had hoped to find some sharp reaction and he found it indeed. Each of his suspects started violently, but so did everyone else at the table. "In a story I've been reading," he added.

"Speaking of landslides..." began the doctor.

"Oh, but who is?" said Mrs. Lancaster. "Oh, let's not speak of them."

"I was wondering about mining accidents," said the doctor, glaring at the old woman. "And Mr. MacDonald is a mining engineer. There are such horrible cave-ins, aren't there? I always wonder why the timbers are not more looked to so that everything can be more safely secured."

"The trouble is," said MacDonald, "that when the ground starts moving timbers may be mere matchwood in front of it. When a hundred million tons start slipping, for instance. I've seen timbers that were two feet through, of good, seasoned, solid wood, smash up slowly, like soft candy."

"Horrible!" said Mrs. Lancaster. "It makes me frightfully ill to think of it."

"It's made a lot of people dead, even," said MacDonald. He turned his cheerful face and smile around the table. He really had a very genial manner and Kennedy warmed toward him. "Unstable ground," he added, "is queer stuff. When miners enter an old stope, for instance, they never speak aloud. They whisper, because vibration, even just the faint touch of a vibrating human voice, may be enough to start a thousand tons falling.

"You hear one pebble fall, far away. Then something like the rustling of a skirt—if you've ever heard that rustling, any miner will listen to your stories the rest of your life, because you're a lucky chap to have lived through it. After the rustling, the big stones begin, or the whole ruin may come down with a rush."

"What dreadful danger!" said the doctor. "Strange that men can be induced to work underground."

"Oh, life is always cheap," said MacDonald.

"But can't the uncertain ground be studied and the miners forewarned?" asked Kennedy.

"Yes, of course," said MacDonald. "You get so that you can almost read the mind of a drift after you've gone into it and looked around for a while. You have practice but beyond that you have instinct that tells you when the ground will move—say in thirty days. It's best not to be wrong about it."

"Were you ever wrong about it?" asked Mrs. Lancaster.

"Yes. Once," said MacDonald.

"Do tell us," she begged.

"You wouldn't like it," said MacDonald. "I didn't like it at the time."

But still he kept on smiling, and Kennedy remembered that smile when he was back in his cabin. What he chiefly regretted was that he had not poised and prepared that single word "murder" in such a way that it would have told more sharply. It was tact that he should have used in making that remark. Tact would have enabled him to choose a moment when his three suspects were right under his eye, and then it might have meant something.

As it happened, he had dropped his depth charge into a whole school of fish, and every one of them had been alarmed. There was no use looking for degrees. He remembered, with a smile, Mrs. Lancaster's small scream. He was beginning to wonder if the old lady did not really dote on violent sensations.

He turned out the light and sat in the darkness for a time, adding up all his faults and frailties. He could not help wishing that the Creator had added several things to his gift-basket. He would have chosen a little more grace, better looks, and above all he would have prayed for bravery.

This thought pursued him. On his other adventures he had not needed it so much, but now he found himself horribly tempted to pack his knapsack and leave Seven Mile House, even in the middle of the night. For no matter how he had tried to smooth it over, his use of the word "murder" at the table this night must have revealed a great deal to the killer of William Harrison.

The dog, roving back and forth unhappily through the cabin, stood up to look out the window. When he had dropped down, he turned to Kennedy and poked him with his nose. Kennedy obediently got up and looked out.

It was not late, but every light was gone in the tavern. A clouded moon shone somewhere in the east and showed him a woman going toward the toolshed.

Gun in hand, Julie stole toward the dead man...

Kennedy got out of the cabin instantly. He hurried down by the bank of the stream and came up toward the toolshed from that side, which was farthest from Seven Mile House. There was a dim light now inside the shed. It was so faint that hardly any radiance escaped through the big cracks in the side of the shanty, but when Kennedy had his eye at the first aperture, he saw Julie Vernon leaning over Harrison's body. She had drawn the sheet back to his hips and as she bent above him, Kennedy would have given a great deal to see her face. However, he dared not change his position. She unbuttoned Harrison's coat, turned back the flaps of it, and drew his wallet from his inside pocket. Here Kennedy in his excitement leaned forward with such weight that the flimsy board gave with a creak under his hand. Julie Vernon started around, shining the electric torch straight at him. Brighter than the light, in the eyes of Kennedy, was the businesslike automatic which she lifted. And more important still was her face, left in such shadow that he could rather guess at than see the flare of the nostrils, the hard, quick resolution. Through the crack just before his face, he swore that she must be seeing him, but after a moment she turned away to open the wallet and after an instant of search to take from it what seemed to him a folded bit of newsprint. The wallet she then restored to the pocket, rebuttoned the coat, and drew up the sheet as it had been before.

Julie Vernon started around, shining the electric torch straight at him.

Kennedy, walking as on thin ice, tiptoed back from the toolshed. He had gained the shelter of one of the willows by the bank of the stream, when a light brushed through the branches. He half expected a bullet to come crashing after it, but then he saw Julie Vernon outside the shed turning her flashlight back and forth. He had reached his shelter barely in time. He feared that she might examine the ground for footprints, but after an instant she turned back to Seven Mile House and disappeared in the entrance hall.

And suddenly Kennedy knew that he must follow her. That gun and the look of her, ready to use it, had frightened him badly enough, and yet the imp of the perverse was driving him straight after her, for he must in some manner read what she had taken from Harrison.

So he found his feet carrying him steadily up the steps, across the verandah, and through the unlocked front door of the tavern. He passed through the living room. Beyond it, Julie Vernon stood in the unlighted lounge, but the dying fire on the hearth gave it a certain amount of illumination.

"Oh, Miss Vernon!" said Kennedy.

She turned sharply about and threw something behind her toward the hearth. Into the flames it seemed to go, and he felt with a pang greater than his fear that he had lost his opportunity.

"Yes? Yes?" she answered, lifting her voice high with the second word.

He paused in the doorway.

"It is a bit damp and chilly out there in the cabin," he said. "I put on my clothes again—and then I thought perhaps I could get an extra blanket?"

The tension passed slowly from her. Yet she made a brief pause before she answered: "Very well. I'll bring you one."

She crossed the living room, saying brusquely over her shoulder: "If you'll come this way, please..."

"Certainly," mumbled Kennedy around a cigarette, vainly snapping a lighter to ignite it. And as she went on through the doorway, he slipped back to the fire on the hearth. There was still a thin ghost of a hope that the crumpled paper might have rolled through the coals and onto the dead ashes. In fact, he found a tiny twist of newsprint dusted over with ashes in a corner of the hearth. He pocketed it.

He slipped back to the fire on the hearth.

When he reached the hall, Julie Vernon was coming down the stairs with a white blanket over her arm.

His cigarette was burning, but to explain his delay he kept on whirling the wheel of his lighter with an impatient thumb.

"These gadgets," he said. "A man will make a fortune if he manufactures one that really goes."

"I daresay," said Julie Vernon, waiting for him to go.

"Good-night, and thanks," said Kennedy, turning to the door.

"Good-night," she said.

"You don't like me at all, do you?" he said, holding the door open.

"Isn't that an odd question?" she asked.

"Oh, I expect the truth," answered Kennedy. "It generally hurts, but I like to have it."

She came suddenly to him and looked up into his face. She was serious. There was not even a hint of a smile, and this masculine gravity made her look older. He could see the small wrinkles around her eyes and one shadowy mark in the center of her forehead that he had not noted before.

"Are you honest, Mr. Kennedy?" she asked.

He was about to smile and say that he hoped he was fairly honest but an odd impulse towards confession swept over him.

"I don't know," he found himself saying. "Honesty's something to pray for, I suppose, not something to own. Mine gets away from me. God made me a simple fellow but sometimes I'm dodging behind that simplicity and having all sorts of ideas."

"I thought so," she said. "What are you after, Mr. Kennedy? Just what is on your mind?"

"There's sleep on my mind, just now," he said, and tried to smile,

It was no use.

"That's hardly true," she answered. "I'm afraid that you don't intend to close your eyes at all."

"Well, I'll do my best. And good-night again."

"I'm afraid that it's goodbye, isn't it?" she asked, gravely.

He got outside the door, somehow and went hastily across the porch. He was halfway down the steps before he realized that a tall figure had been standing on the verandah, wrapped in a coat or cloak. Now he glanced back over his shoulder and made sure that the form was there. He did not speak, and there was no word from the other, but he knew in his cold, shrinking heart that Daniel Fargo was there, on watch.

WHEN he reached the cabin, a new fear came up in him, a grisly conviction that something waited for him inside. At the door he hissed. He heard the dog instantly on the move but this did not deny the possibility that the dog's owner might be with him. When he pulled open the door, the big body of the shepherd almost knocked him flat as it sprang through the gap. He made a frantic clutch at the chain and caught it by a lucky chance. The shock jerked him to his knees and one hand but it stopped the dog, which was busily at work with its nose to the ground.

Someone decidedly had been there in the past few moments. He dragged the big dog back into the cabin and lighted the lamp again. What looked like a pool of blood glistened red in a corner. It proved to be a fine cut of steak. As he lifted it, the dog came up hungrily but after a sniff or two turned away without touching it.

Wolves, they say, will come to know poison by its smell; and this dog seemed more wild than tame.

This was the second effort the killer had made to remove the dog from his trail. Perhaps he had worked the window open, spoken to the poor beast and caressed it before he tossed in the poisoned meat?

Kennedy secured the shutters of the window again. Still he was not alone. There were crevices in these walls, not so large to be sure as those of the toolshed, but amply big enough, here and there, to let an eye look in, and where an eye can look, a gun can shoot. The wind which had been rising now was a strong sweep down the valley and it whistled around and into the cabin of Kennedy with a chorus of small, shrilling voices.

That twist of paper seemed to him now more important than poisoned meat or pointing guns. He hooded the light of his lamp so that it shone freely on one point only. Then he undid the bit of newsprint which had been in his pocket. It was torn by the tightness of the twist it had been given, but he was able to smooth it out fairly well and piece in from imagination the few words which had disappeared.

It was a news clipping of some length, which read:

"At 9.55 last night the jury in the Crittenden murder case filed into the jury box, the judge appeared in his robes, the court was brought to order, and the foreman read a verdict of 'Not Guilty.'

"The crowd, which had been waiting since eleven in the morning, seemed of a divided mind. There were some catcalls and whistles mixed with a burst of applause.

"The defendant, Jessica Vance, as calm as she had been through the entire trial, thanked each of the jurors in person, posed for camera shots, and then fainted. Her attorney, William Harrison, then..."

Here Kennedy stopped reading for a moment. He was drinking in his information too rapidly, it seemed. William Harrison, he remembered, had been a lawyer in the East before he took up mining promotion. And the initials of Jessica Vance were those of Julie Vernon. So Harrison had appeared here with this little document which was no more than a reminder of the past. And what could Julie Vernon do with Seven Mile House, if it were known that she once had been tried for murder? In American courts, it seems, innocence never is proved. The very atmosphere of crime seems to exude from our legal processes, and the stigma once attached to a name never can be washed clean again.

Was it blackmail that Harrison wanted? Had Julie Vernon and big Daniel Fargo between them disposed of this unwelcome guest? He could remember, from the tale of Maria, that Harrison had been a lot with Julie Vernon. Of course he had, for who could refuse anything to a man who knew so critically much about the past?

It might well be that Julie, however aware of danger from Harrison, had not lifted a hand to get rid of him. In that case, Fargo might have acted.

Kennedy returned to the clipping. It was one of those old New York stories, one of those fine flowerings which have their roots in Wall Street and bloom on Broadway. Mr. Crittenden, a broker who appeared richer than he was, had interested himself in his pretty young stenographer, who had stage ambitions.

A play had been chosen. Arrangements were being made to buy it. Casting problems had been put up to a producer. And then everything went sour. Suddenly the play no longer was headed for the boards. And a day or so later Mr. Crittenden was shot in his apartment. It was not a very mysterious killing, because Miss Vance had a key to the apartment. However, it was not definitely proved that she had lived with her employer. Neither was it proved that she owned a revolver or that she had fired the shots which killed Crittenden.

There was another possibility. It was known that a woman had entered the rooms of Crittenden that night; but there was a possibility that Crittenden's wife, from whom he had been separated for some time, might have used her old key to the place. It was this that saved Jessica Vance.

But though the jury acquitted her, it was not hard to understand why she had chosen to erase the old name and enter the world with a new one. It was not strange that she had desired to live as far from New York as Seven Mile House, either. And if a William Harrison who once had secured her acquittal appeared in her life again, surely she would be clay in his hands.

Kennedy touched the flame of his lighter to the clipping and watched it burn to a black ash that turned gray, dissolved, and floated into the air, lifted by the fire that consumed the last corner. Then he hastened to put out the lamp. Even after that, however, to his jumpy nerves it seemed that the wind was filled with angry voices that gathered in the distance and ran toward him.

He stretched himself on his bed, the blanket still huddled about him. He could not think very well. The best he could do was to watch the crawling of the moonlight which entered through a bit of glass that served as a skylight and could be lifted in hot weather to give the small room better ventilation. The rectangular patch of light had left the floor and was lifting along the frame of the door. It reached the brass knob, in due time, and the attention of Kennedy, as he lay there fixed on the glistening metal. That was how he happened to see it move.

We ourselves that we are dreaming, that it is illusion, when such things occur. So did Kennedy, sitting bolt upright, his heart in his throat. And the wind, shaking the little cabin from top to toe, screamed for him like a mad thing.

The knob turned back, hesitated, once more moved slowly to the left, paused, and again turned back to the normal position. If the master of the dog were standing there, why did not the brute scent him and go wild with joy? But then Kennedy remembered that the gale was blowing from the opposite direction.

He waited with hysteria growing up in him; then he bounded from the bed, turned the key, and jerked the door open.

The whole air of the cabin seemed to rush out past him in a single breath, but no-one stood at the door. The dog, struggling to get past him, he caught by the lead and permitted him to get a few steps into the open, but here a drift of clouds blackened the face of the moon and Kennedy could see no more. After all, there were plenty of trees behind which this nightwalker could have disappeared.

Courage faded out of Kennedy swiftly. He pulled the dog back inside the cabin and sat down again with his face in his hands. But that was blinding himself to danger that might break in at him. He sat erect. The skylight, through which the moon was shining again, was like a pointed gun.

Still that curious brain of his was examining the situation, twisting it, turning it, moralizing. The hand which had come there and turned the doorknob, prepared for murder, had hesitated to break down the door! Yet the noise hardly would have reached the Seven Mile House, in this outcry and yelling of the wind. One thrust of the shoulder would have beaten the door in, of course. But if it failed to do so, the man inside would be roused and alert for his defense. But what had he for defense except his bare hands?

His mind kept turning back to murder. It is the only common madness. One can understand war-killings when masses of men go over the top in a shouting passion. But murder that goes forehanded about its work is incomprehensible. Even now Kennedy refused to believe that an enemy had stood there outside his door, softly fumbling at the knob.

He swept his things into his knapsack, laid three one-dollar bills on the washstand and went out into the open night with the wind pushing him forward, lengthening his strides until it was like walking downstairs.