RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

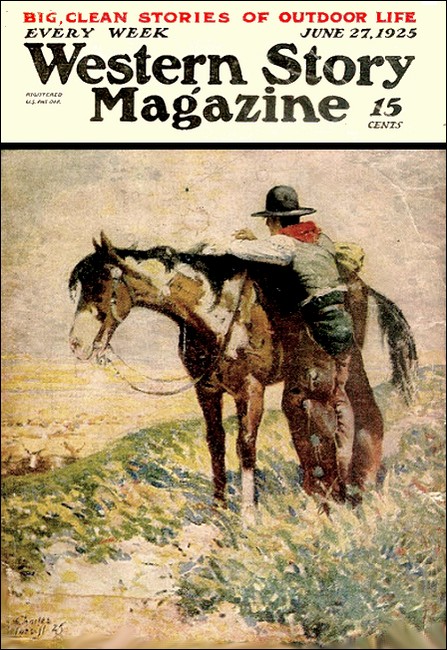

Western Story Magazine, 27 June 1925, with "His Fight for a Pardon"

WHEN I got down to see Molly O'Rourke, Sheriff Dick Lawton crossed my way with three of his hard-riding man-getters. Every man-jack of them was on a faster nag than my mule, but I kept Roanoke in the rough going, and Dick Lawton was foolish enough to follow right on my heels instead of throwing a fast man out on my course. For he knew what that course was. He had hunted me before, and it was a sort of unwritten law between us that, if I got into the mouth of the little valley where the O'Rourke house stood, I was free.

That may sound specially generous on his side. But it wasn't—altogether. Twice he had pushed his posse up that ravine after me, and it almost cost him his next election. Because that ravine twisted like a snake, back and forth, and it was set out with shrubs and trees as thick as a garden. I simply laid up in a comfortable shady spot, and, when the boys came rushing around the bend, I let them have it. So easy that I didn't have to shoot close to a dangerous spot. I could pick my targets. However, I think that there were half a dozen had wounds in arms and legs. Also, I pulled too far to the left on one boy and drilled him through the body. So, as I say, the sheriff nearly lost his election after that because it was said that he had ridden his men into a man trap.

So far as Dick Lawton was concerned, I knew that valley was forbidden as a hunting ground to him. And, of course, I could trust Dick as far as he could trust me—that is to say, to the absolute limit. Because, except when we were shooting at each other, we were the best friends in the world. I know that Dick never shot extra straight at me, and I know that I never shot straight at him. My guns simply wobbled off the mark when I caught him in the sights.

Well, as I was saying, I kept old Roanoke in the rough where he could run four feet to the three of any horse that ever lived—for the simple reason that a mule's hoofs and skin are a lot tougher than a horse's. By the time I got across the valley, there was a clean furlong between me and Dick Lawton's boys. So I took off my hat and said good bye to them with a wave that was nearly my last act in life. Because just as I put that hat back on my head, a .32-caliber Winchester slug drilled a clean little hole through the brim a quarter of an inch from my forehead.

I've noticed that when a fellow stops to make a grandstand play of that sort, he generally gets into pretty hot trouble. I sent Roanoke into the brush with a dig of the spurs, but the minute I was out of sight, I knew that there was no trouble left.

But I didn't slow up Roanoke. I didn't even stop to roll a cigarette, because I hadn't seen Molly for three months. You see, it was right after the Sam Dugan murder which some fools hung on me. Of course, Lawton hadn't the least idea in the world that I could have done such a rotten, treacherous thing. But they stirred up such a fuss that I didn't dare to try to slip in to see Molly. Because everyone had known for years that I loved Molly and got down to see her once in a while, and, when things were pretty hot, they used to watch her house.

So I slithered up the ravine until I got a chance to squint at the ridge, and there I found a little green flag, jerking up and down and in and out in the wind, on top of the O'Rourke house. I knew that was the work of Molly's father. I think that every day of his life the old man went snooping through the woods to see if the land lay quiet. If it was, he tagged the house with that little green flag—green for Ireland, of course—and then, when someone was laying for me near the house, he would hang up a white flag.

When I saw that green, I dug into Roanoke and sent that mule hopping straight to the house. As I hit the ground, I heard old man O'Rourke singing out inside the screen door of the porch: "Hey, Chet! Here's Roanoke to put up, and sling a feed of barley into him. Hey, mother, come and look at that dog-gone mule! Hey, Molly, there's that Roanoke mule wanderin' around loose in the yard!"

Chet O'Rourke came first, and his old mother at his shoulder, and then the old man came next. I grabbed all their hands. It was like stepping into a shower of happiness, I tell you, to get among people where the feel of their eyes was not like so many knives pointed at you. But I brushed through them pretty quick. I wanted Molly.

"Hey, Molly!" yelped old O'Rourke. "Ain't you comin' to see Roanoke?"

He laughed. I suppose that he was old enough to enjoy a foolish joke like that. I heard Molly sing out from the stairs beyond the front parlor. I reached the bottom of those stairs the same minute she did and caught her.

She said: "Chester O'Rourke, will you take this man away from me?"

I kicked the door shut in Chet's face and sat Molly on the window sill where the honeysuckle showered down behind her like green water, if you follow my drift. It would have done you good to stand there where I was standing and see her smile until the dimple was drilled into one cheek. She began to smooth her dress and pat her hair.

"My Lord," I said, "I'm glad to see you."

"You've unironed me," said Molly. "Just when I was all crisped up for the afternoon."

"Have they nailed the right man for the Dugan murder?" I asked. Because I was as keen about that as I was about Molly.

"They've got the right man, and he's confessed," she said.

I lowered myself into a chair and took a deep breath. "That's fixed, then," I said.

"That's fixed," she agreed.

"Why do you say it that way?" I asked.

"How old are you, Leon?" she said.

"I'm twenty-five."

"How old does that make me?" said Molly.

"Twenty-three."

"That's right, too. How long have you been asking me to marry you?" Molly asked.

"Seven years," I said.

"Well, the next time you ask me, I'm going to do it."

"Law or no law?" I said.

"Law or no law."

It made my head spin, of course, when I thought of marrying Molly and trying to make a home for her while a hundred or so cowpunchers and sheriffs and deputies, et cetera, were spending their vacation trying to grab me and the $20,000 that rested on top of my head as a reward. I moistened my lips and tried to speak. I couldn't make a sound.

"You know that I've done what I could," I said finally.

"I do. But now things are different."

"What do you mean?"

"William Purchase Shay is the governor, now."

"What difference does that make?"

"He's a gentleman," she said.

"Well?"

"I think he'd listen to reason."

"You want us to go see him?"

"Just that."

"I see myself handing in my name at his office," I said. "I guess he's not too much of a gentleman to want to make twenty thousand dollars."

"Money has spoiled you, Leon," said Molly.

"Money? How come?"

"You're so used to thinking about how much you'll be worth when somebody drills a rifle ball through you... that it's turned your head."

"Are you talking serious?"

"Dead serious," she replied. "Besides, you're not the only one that folks have to talk about now."

"I don't understand."

"Jeffrey Dinsmore is the other man."

Of course, I had heard about Dinsmore. He was the Texas man whose father left him about a million dollars in cattle and real estate, besides having a talent for shooting straight and a habit of using that talent. Finally he killed a man where self-defense wouldn't work, because it was proved that Dinsmore had been laying for him. The last heard, Dinsmore was drifting for the mountains.

"Is Dinsmore in these parts?" I asked Molly.

"He showed up in town last week and sat down in the restaurant...."

"Disguised?"

"Yes, disguised with a gun that he put on the table in front of his plate. They didn't ask any questions, but just served him as fast as they could."

"Nobody went to raise a crowd?"

"The dishwasher did, and a crowd gathered at the front door and the back."

"What happened?"

"Dinsmore finished eating and then put on his hat and walked out."

"Good Lord, what nerve! Did he bluff out the whole crowd?"

"He did."

"What's on him?"

"Just the same that's on you. Twenty thousand iron men."

"Twenty thousand dollars?" I repeated.

"You look sort of sad, Leon."

You'll think me a good deal of a fool, but I confess that I was staggered to find that there was another crook in the mountains worth as much to the law as I was. Between you and me, I was proud because I had that little fortune on my head.

"Twenty thousand!" I said again.

"Dead or alive," Molly said with a queer, strained look on her face.

"Why do you say it that way?" I said in a whisper.

"Don't you understand?"

Then I did understand, and I stood up, feeling pretty sick. But I saw that she was right. Something had to be done.

"I start for the governor today?" I stated.

Molly simply hid her face in her hands, and I didn't wait for her to break out crying.

I SAW the rest of the family for an hour or so before Molly came in to us. She was as clear-eyed as ever, when she came, but there was something in her face that was a spur to me. I did not wait for the night. I judged that no pursuers would be lingering for me in the valley of this late day, so I slipped out of the house, finding Roanoke refreshed by his rest and a feed of grain. I went away, without leaving any farewells behind me.

I cut across country, straight over the ridge of the eastern mountains. Just below timberline I camped that night—a cold, wet night—and I rode on gloomily the next morning until I was over the crest of the ridge and had a good view of the land that lay beneath me. It was a great, smooth-sweeping valley, most of it, the ground rolling now and then into little hills—but with hardly the shadow of a tree—and so on and on to piles of blue mountains which leaned against the farther horizon. They were a good hundred miles away. Between me and that range lay the city that I had to reach. You will agree with me that it was not a very pleasant undertaking. I had to get myself over seventy miles of open country to the capital of the state. Then I had to get seventy miles back into the mountains once more.

However, there was nothing else for it. That day I went down to the edge of the trees and the foothills, and there I rested until the verge of dusk. When that time came, I sent Roanoke out into the open and heading straight away toward the big town. He could have made the distance before daylight, but there was no point in that. I sent Roanoke over sixty-five miles that night, however, and he was a tired mule when I dropped off his back on the lee side of a haystack. I could see the lights of the town five miles off. Not a big place, you will think, but there were 35,000 people there, and that made it just about five times as large as any city I had ever seen in my life. It was simply a metropolis to me.

The dawn was only a moment away. So I walked away from the stack to a wreck of a shack in a hollow. There I turned in and slept solidly until afternoon.

I was thirsty and tired and hungry when I wakened. Besides that, I had a jumpy heart and the strain of the work ahead of me was telling pretty fast. The worst part of the trip was wasting that afternoon and waiting for the night. The edge of the sun was barely down before I was streaking across open country, and there was still plenty of daylight when I cut down a bridle path near the edge of the town and met an old fellow coming up. He was riding bareback, and I shall never forget how his white beard was parted by the wind.

He gave me a very cheerful—"Howd'ye,"—and I waved back to him.

"Well, stranger," said that old man, "where are you aimin' for, if I might ask?"

"Work," I said.

"Come right along with me."

"What kind?"

He had one tooth in the right-hand corner of his upper gum. He fixed this in a wedge of chewing tobacco and worked a long time at it until he got it loose. All the while he was looking at me with popping pale-blue eyes. I never before had noticed how close an old man can be to a child.

"Well, partner," he said, "young fellers is picky and choosey. I used to be that way myself. But when I come to get a little age behind me, why, then I seen that it didn't make so much difference what a man done. All kinds of work that ever I see gives you the same sort of an ache in the shoulders and an ache in the calves of your legs and in your back. Ain't you noticed that?"

I told him that I had.

He said: "Same way about chuck. I used to be mighty finicky about grub. It don't make no difference to me now. Once a mite of grub is swallered, what difference whether it was a mouthful of dry bread or a mouthful of ice cream? Can you tell me that?"

I could see that he had branched out on his special kind of information. Most old men are that way. They got a couple of sets of ideas oiled up in their old noodles, and, whenever they get a chance, they'll blaze away on them. If they're interested in oil wells, you can start talking about lace and they'll get over to oil wells just as easy as if you started with derricks. I saw that this was one of that brand. However, if he would talk, I saw that he might be of some sort of use to me.

So I said: "I've been back country for a long time. I want to have a try working in town."

He shook his head, very sad at that. "Son," he said, "I live only two mile out, but I have been to town only once this summer. And that time I come home with my feet all blistered up and my head aching from the glare of the pavements. I give the town up. If I was you, I'd give it up, too."

I said nothing, but I couldn't help smiling. The old chap began to nod and smile, too. He was a fine fellow, no doubt of that.

"Well," he said, "you can't expect folks to learn by their elders. If they did, people'd get wiser and wiser, instead of the other way. What you want to do in town?"

"Drive an ice wagon, maybe. I don't care. I never seen the town before."

"You don't say?"

"I guess that's the capitol building?"

"Yes, sir. There she is. That white dome. I guess you seen it in your schoolbooks when you was a kid? There she be. Look here, ain't you been raised right around near here?"

He had sagged a little closer to me while we were looking at the town, and now I caught him batting his bleary old eyes at me behind his glasses. I knew there was danger ahead.

"No," I said. "I've never been in the big town before."

"Oh, it ain't so big. Me, I've been far as Saint Louis. Now, there's a real city for you. It lays over this a mighty lot!"

"I suppose it does. But it hasn't many things finer than the capitol building, I guess."

"Well, I dunno. It's got a lot of banks and things pretty grand with white stone posts around them. And it makes a heap of noise. You can hear it for miles. But you can't hear nothin' here... except the scrapin' of a street car goin' around a corner, maybe."

As he finished speaking, out of the distance came the scraping noise just as he had described it—like a rusty violin string, very thin and far. The old man laughed and clapped his hands.

"Well," I said, "I suppose there are other fine big houses there. The governor's house must be mighty fine."

"Him? No, sir. William P. Shay ain't the man to live big and grand. He's livin' in his ma's old house out on Hooker Avenue right alongside the park... which has got so fashionable lately, what with the street car goin' out that way, and the park right opposite with the benches to set on. I passed that way once, and I never forget the smell of the lilacs passin' by Missus Shay's house. It was sure a sweet thing."

"I suppose that they're still there?"

"Yes, sir."

"Other folks got 'em, too?"

"Nary a one. Young feller, I can't get out of my head that I've seen you sure, somewheres, sometime."

I knew very well where he'd seen me. It was in some roadside bulletin board or perhaps just a handbill nailed against a post, showing my face and with big letters under it. I knew very well where he had seen me. I decided that I had better go right on into town and get lodgings before it was too dark. But after I had gone a little way, I leaned down as if to fix a stirrup leather and I had a chance to glance back. Old white beard was already over the hill.

I didn't suspect that he had seen too much of me. But when a man has been a fugitive from the law with a price on his head for seven years, it makes him overlook no bets. I recalled, too, that I was riding a mule, and that in itself was enough to make any man suspicious. So I snapped back to the top of the hill, and, through the hollow beneath, I could see the old man scooting along. He looked back over his shoulder, just then, and, when he saw me, he doubled up like a jockey putting up a fast finish down the stretch and began to burn his whip into that old horse he was riding.

I shouldn't have done it, of course. But I couldn't help wanting to make his fun worthwhile. So I fired a shot straight through the air.

I heard his yell come quavering back to me, and after that the horse seemed to take as much interest in the running as its rider did. He hunched himself like a loafer wolf trying to shove himself between his front legs while he beats for cover. It was a mighty funny thing to watch. I laughed till I was crying. By that time the old man had disappeared in the night and the distance. Then I turned around and saw that I had a big job to do and to do fast, because as soon as that old fogy got to a house with a telephone in it, he would plaster the news all over town that Leon Porfilo, on his mule, was heading straight for them, ready to make trouble, and lots of it.

How many scores of men and boys would clean up their old guns and start hunting for me, I could only guess. But right there I made up my mind that I couldn't enter that town on a mule. I put old Roanoke away in a little hollow where there were trees enough to shelter him and a brook in the center to give him water and plenty of long, coarse grass among the trees for provender.

Then I shoved my guns into my clothes and started hiking for the town. It was mighty risky, of course, because, if trouble started, I was a goner. But I decided that I'd be a lot less looked for on foot. You'll wonder, perhaps, why I didn't wait a few days under cover before I went in. But I knew that the next morning a hundred search parties would be out for me, unless I was already in jail.

IT was not so bad as I had expected. A city of that size, I thought, would be so filled with people that my only good refuge would be in the very density of the crowd, but, when I reached the outskirts, I found only unpaved streets and hardly anyone on the sidewalks saving the few workingmen who were hurrying home late to their suppers. And what a jumble of suppers! One acquires an acute nose in the mountains or on the desert, and I picked out at least fifty different articles of cookery before I had covered the first block.

I started on the second with a confused impression of onions, garlic, frying steak, stew, boiled tomatoes, cabbage, bacon, coffee, tea, and too many other things to mention. Nasally speaking, that first block of the capital town was like the first crash of a symphony orchestra. I went on very much more at ease through block after block with almost no one in sight, until I came to broad paved streets where there was less dust flying in the air—and where the front yards were not simply hard- beaten dirt with a plant or two at the corners of the houses. For here there were houses set farther back. Some had hedges at the sidewalks, but all had gardens, and most of the way one could look over blocks and blocks of neatly cropped lawns, with flower borders near the houses, and flowering shrubs set out on the lawns. There were scores and scores of watering spouts whirling the spray into the air with a soft, delightful whispering. They all had a different note. Some of them rattled around slowly and methodically like so many dray wheels, throwing out a spray in which you could distinguish each ray of water all the way around. There were some singing and spinning and making a solid flash like the wheel of a bright-painted buggy when a horse is doing a mile in better than three minutes. Once in a while a breeze dipped out of the sky and stirred the heavy, hot air of the street, and blew little mists of the sprinklers to me and gave me quick scents of flowers. But always there was that wonderful odor of the ground drinking and drinking.

I felt very happy, I'll tell you. I felt very expansive and kindly to the whole human race. Now and then I'd see a man run down the steps of his house and go out in his shirt sleeves and take hold of the hose and curse softly when the spray hit him and then give the sprinkler a jerk that moved the little machine to another place. Like as not, he jerked the sprinkler straight toward him. Then he would duck for the sidewalk and stand there, wiping his face and hands with a handkerchief and stamping the water from his shoes and "phewing" and "damning" himself as though he were ashamed.

But before they went back into the house, each man would stop a minute and look at the grass and the shrubs, each beaded with water and pearled with the light of the nearest street lamps—and then up to the trees—and then up to the stars—and then go slowly into the house, singing, most like, and stepping light. When those men lifted their heads and looked up into the sky, I knew that they saw heaven.

When one young fellow ran out from his front door, I saw a girl come to the window and look after him, and hurry him with: "The soup will be stone cold, Archie."

I couldn't help it. I stopped short and leaned a hand against a tree and watched him move the sprinkler. Then, humming under his breath, he ran for the house. There were springs under that boy's toes, I tell you. From what I could see of the girl, I didn't wonder. But at his front door, he turned and saw me still standing under the tree, watching, and aching, and groaning to myself: "Molly and me... when do we get our chance... when do we get our chance?"

He called out: "Hey, you... what you want?"

A mighty snappy voice—like the home dog growling at a stranger pup. He was being defensive.

"Nothing," I said.

"Then hump yourself... move along!" he snapped.

Perhaps you'll think that I might have been angered by that. But I wasn't. I was only pretty well sickened and saddened. If ever I were caught—and this night there was a grand chance that the law would take me—the dozen men in the jury box would be no better than the fellow—a clean-living fellow, with his heart in the right place—but snarling when he saw a strange dog near his house. Human nature—I knew it—and I didn't blame him.

"All right. I'll move along," I said.

I only shifted one tree down and stopped again. You see, I wanted to watch that fellow go striding into his house and into that dining room and watch his wife smile at him. Sentimental bunk? I know that as well as you do, but when a man has lived alone for seven years with mountains, and above timberline most of the time—seven winters, you know—well, it makes him either a murderer or a softy. I hardly know which is worse. But I was not a murderer, no matter what the world might say of me.

The householder had a glimpse of me again as he swung open his front door, and he came flaring back at me with the running stride of an athlete. I saw that he was big, and big in the right places. He was in front of me in another moment.

"I'm going!" I said, and I turned and started shambling away.

He caught me by the shoulder and whirled me around. "Look here!" he said. "I don't like the looks of you... and the way you hang around. . . who are you?"

I shrank back from him against a tree. "A poor bum, mister," I replied. "I don't want no trouble. But I was lookin' through the window. It looked sort of home-like in there."

"You're lying!" he argued. "By heaven, I'll wager you're some second-story crook. I've a mind...." He put his hand on me again.

You'll admit that I'd taken a good deal from him. But it's easy for a big man to take things from other people. I don't know why that is. Little fellows always have a chip on their shoulders. But big fellows learn when they're young that they're always too big for the other boys. But still, I was a bit angry when this young husband began to force his case at my expense. There were two hundred and twenty pounds of me, but down to the very last pound of me I was hot.

Just then the girl's voice sang out: "Archie! Archie! What are you doing?... oh!" There was a little squeal at the end as she sighted me.

"You see?" I said. "Let me go. I won't trouble you any. And you're scaring your wife to death, you fool!"

"What? You impudent rat...."

He started a first-rate punch from the hip, but I caught his wrist and doubled his arm around behind him in a way that must have been new to him. He was a strong chap. But he hadn't any incentive, and he hadn't any training.

We stood with our faces inches apart. Suddenly he wilted.

"Porfilo!" he said through his teeth.

"Do you think I'm going to sink a slug in you?" I asked.

I saw by the look of his eyes that he did, and it made me a pretty sick man, I can tell you. I dropped his arm and I went off down that street not caring a great deal whether I lived or died.

I went down that street until it carried me bang up against the capitol building in the middle of a great big square. Off to the right was the beginning of the park. I went off down the street that faced on it. I think I must have passed five hundred people in that square, but I'm certain that not one of them guessed me. It would have been too queer to find Leon Porfilo walking through a street. They passed me by one after another—which shows that we see only what we expect to see.

In the street opposite the park, it was easy going again. It was a fairly dark street because there were no lamps except at the corner, and the blocks were long. Lamps on only one side of the street, too—because the park was on the other side and that was a thrifty town.

I walked about half a mile, I suppose, from the central square, and then I found the house without looking for it. It was simply a great out-welling fragrance of the lilacs, just as the old man had told me. There was the yard filled with big shrubs—almost trees of 'em, and in the pool of darkness around the trees were rows and spottings of milk-white lilies. It was a good thing to see, that yard. It was so filled with beauty—I don't know exactly how to say it. It was filled with homeliness, too. I felt as though I had opened that squeaking gate a hundred times before and stepped down onto the brick path where the grass that grew between the bricks crunches under my heels.

Then I side-stepped from the path and among the trees. I went to the side of the house. I climbed up to the window in time to see the ceremony begin. About a dozen people piled into the room, and, when the seating was over, a grim-faced man sat at the head of the table and a pretty-faced girl of twenty-one or so at the other. Then I remembered that the governor's wife was not half his age.

I thought I understood one reason for the tired look on his face. There was nothing for me to do for a time, so I found a bench among the trees and lay down on it to watch the stars.

I waited until the smell of food went through me, and I tugged up my belt two notches. I waited until the humming voices and the laughter that always begin a meal—even a mountain dinner—died off into a broken talking and the noise of dishes. Then music, somewhere. Well, I was never educated up to appreciating the squeaking of a violin. A long time after that, somebody was making a speech. I could hear the steady voice. I could almost hear the yawns.

Somehow, I pitied the pretty girl at the far end of the table!

I WAITED a full hour after that. People began to leave the house, and finally, when the front door opened and closed no more, I began my rounds of the house. I found what I wanted soon enough. It was not in the second story, but a lighted window in the first, and I had a step up, only, to get a view of the inside of the room, and a broad-gauge window sill to hang to while I watched. The window was open, which made everything easier. There was not much chance for me to be betrayed by the noise I might make in stirring about, for the wind was slipping and rustling among the trees.

I was looking into a high, narrow room with walls covered with books and queer, old-looking framed photographs above the bookcases. There was a desk that looked as solid as rock. In front of the desk was the governor. I could have told that it was the governor even if I'd never seen him before, because he had that gone look about the eyes and those wrinkles of too much smiling that come to men who have offices of state. A man like that, when his face is at rest, is simply giving up thanks that he's not offending anyone.

The governor had a man sitting beside his desk—a man who looked only less tired than the governor himself. He was scribbling shorthand while the governor turned over and fiddled at a pile of papers on his desk and kept talking softly and steadily. All sorts of letters.

Well, he had to dictate so many letters, and make them all so different, that I wondered what fellow's brain could be big enough to hold so much stuff, and so many different kinds. I suppose that in that hour he dictated more letters than I'd ever written in my life. I could see new reasons every minute for that tired look. I began to think that he must know everyone in the state.

I heard the secretary ask him if he needed him any longer. I saw the governor look up quickly at him and then stand up and clap him on the shoulder and say: "Go home to sleep. I've not been paying enough attention to you, but forgive me."

I saw the secretary fairly stagger out of the room. Then there was the governor sitting over the typewriter and reading his correspondence on the one hand and picking at the machine with one finger on the other, and swearing in between in a style that would have tickled the ears of any cowpuncher on the hardiest bit of the range.

I didn't hear anyone tap at the door. But pretty soon he jumped up with the look of a man about to accept $10,000,000. He opened the door and the pretty young wife stood there wrapped up to the chin in a dressing gown. She looked him up and down in a way that smeared the smile off his face and left a sick look that I had seen there before. It was an old-fashioned house, and there was a transom over the door. She pointed at the open transom and said half a dozen words out of stiff lips. She didn't say much. Just enough. A bullet isn't very big, either, but, if it's planted in the right place, it will tear the heart out of a man. She jerked about on her heel and flounced away, and the governor leaned against the wall for a minute with all the sap run out of him. Then he closed the door and the transom and went back to the typewriter.

He was pretty badly jarred, though, and he sat there for a moment all loose, like a fellow with the strength run out of him. Then he shook his head and set his jaw and began to batter that typewriter again. I could see that he was a game son of a man. Mighty game and proud and clean. I liked him all the way through, and yet I felt a mite sorry for the girl wife, too, when I thought of the way the governor's language must have been sliding out through that transom and percolating through the house. I suppose that a real respectable house would take a couple of generations to work language like that out of the grain of it.

I slid a leg against the window and made just enough noise for the governor to stop work and sit with his head up. His right hand went back to his hip pocket—and came away again.

I stepped inside the room and was standing there pretty easy when he turned around. He didn't jump up or start yapping for help or do anything else that was foolish. He just sat and looked me over.

"Well, Porfilo," he said at last, "I suppose that you've tried to work out the most popular spectacular job in the state and decided that the governor's house was the best place for it. Is that it?"

I merely grinned. I knew that he would take it something like that, but it was mighty good to hear him talk up. It sent a tiny tingle through all the right places in me. I just took off my hat and made myself easy.

"What do you want?" he said, frowning as I smiled. "My wallet?" He tossed it to me.

I caught it and threw it back. I had both my hands. Somehow, I hated to show a gun to that man.

"Something bigger than that?" he said, sneering. "I suppose that you'll want the papers to know how you held up the governor without even showing a gun?"

I got hot at that—in the face, I mean.

"No, sir," I said. "I'm not a rat."

"Tell me what you want," he said through his teeth. "There was a time when I served as a sheriff in this state, young man. There was a time when I carried guns. And now the fewer moments I spend with you, the better."

"Governor," I said, "do you think I'm a plain skunk?"

"No," he said, very brisk, and with his eyes snapping. "I should call you whatever you please... a purple, spotted, striped, or garden variety of skunk. Never the common sort. Now what do you want with me, young man, if you don't want money? Is it a pardon?"

There was so much honest scorn in the governor's face, to say nothing of his voice, that all the starch went out of me. I could only mumble. "Yes, sir, that's what I want."

He threw up both his hands—such a quick gesture that it made a gun jump out of my pocket as quick as a snake's head out of a hole. I couldn't help it.

He saw the movement and he sneered again. "Porfilo," he said, "I suppose you are going to threaten to shoot me unless I turn over a signed pardon to you?"

I shoved the gun away in my clothes. I was beginning to get angry in turn.

"I've come to talk, not to shoot," I said. "I've come to play your own dirty game with you."

"Is my game dirty?" he asked through clenched teeth.

Oh, yes, he was a fighting man, that governor. I wished that his young wife could have seen him then.

"Isn't it," I asked, "a lot dirtier than mine? You beg people for their votes."

"Entirely false," he replied. "But I enjoy a moral lecture from a murderer."

"I never murdered a man in my life," I said.

It made him blink a little.

"But you," I continued, jabbing a finger into the air at him, "you get up and talk pretty sweet to a lot of swine that you hate."

He parted his lips to answer me, but then he changed his mind and sat back in his chair and watched me.

"About the murders," I went on. "I never shot a man unless he tackled me to kill me."

He parted his lips again to speak, but again he changed his mind and smiled. "You are an extraordinarily simple liar," he said.

It's a good deal to be called a liar and swallow it. I didn't swallow this very well. I snapped back at him: "Governor, I came here to see you because I was told that you're a gentleman."

"Well, well, Porfilo," he said, a little red, "who told you that?"

"A girl," I answered.

"The girl?" he asked.

"Yes."

"Good heavens, Porfilo, are you going to try to hide behind a woman who loves you?"

"I don't hide," I replied. "What I ask you to do is to go down the record against me and figure out where I've sunk lead into anybody that wasn't gunning for me. Was there ever a man I sank that wasn't a gunfighter and a crook before he ever started after me? There never was! I've ridden a hundred miles to get out of the way of trouble, when trouble was showing up in the shape of a clean, decent man. But when a thug came after me, I didn't budge. Why should I?"

"Well," he responded, "I'll tell you what you've done. You've made me listen to you. But just the other day Sheriff Lawton had two fine citizens shot by you."

"Leg and arm," I said.

"Yes, they were lucky."

"Lucky?" I said. "Do you think it was luck, governor? If I've practiced hard at shooting every day of my life for the last ten years, at least, do you think that I'm so bad that I miss at forty yards? No, Governor, you don't think that. Nor do you think that I've stood up to so few men that I get buck fever when I have a sight of 'em. No, sir, you don't think that, either."

The governor scratched his chin and blinked at me. But I was pretty pleased, because I could see that he was getting more reasonable every minute.

"I don't mind admitting," he stated, "that I'm inclined to believe the nonsense that you're talking." He grinned very frankly at me. However, I saw that I still had a long way to go.

"Are you armed?" I asked.

"No," he said, "because very often in my official life I have a reason to use a gun. And I'm past the age when pleasures like that are becoming."

"Are you taking me serious?" I said.

"More than any judge would," he replied.

"I believe you," I said, and I couldn't help a quaver in my voice.

I SAW that put back my cause several lengths and would make the rest of the running pretty hard for me.

He said in that stiff way of his: "Have no sentimental nonsense, Porfilo."

"I'm sorry," I said. Then I burst out with the truth at him, because I could see that there was no use trying to bamboozle him. "A man can't help feeling sorry for himself when he gets down," I said.

The governor twisted up his mouth, and then he laughed. It did me a lot of good to hear him laugh, just then. "As a matter of fact," he said, "not so long ago I was pitying myself. Now, young man, I think I can say that I like you. But that won't keep me for an instant from trying to have you hanged by the neck until you're dead."

"Do you mean that?" I asked.

"I'm too tired to talk foolishness that I don't mean," he responded. "I'll tell you what, Porfilo. If a petition for your pardon were signed by a thousand of the finest citizens in this state, that petition would have no more chance than a snowball in hell."

He meant it, well enough, and I could see that he did. It made me within a shade of as sick as I'd ever been in my life.

"Well?" he asked.

"I'm studying," I said, "because I know that I've got something more to say, but I can't figure out what it is."

The governor laughed, and said: "I come closer to liking you every minute. But why is it that you think that you have something more to say?"

"Because," I explained, "I know that I'm an honest man and a peaceable man."

He laughed again, and I didn't like his laughter so well, this time. "Well," he said, "I won't interrupt you."

"You know that I'm a crook?" I asked him.

"About as well as any man could know anything."

"Have you looked up my whole life?"

"A few chunks of it have been served up to me... such as the Sam Dugan murder."

"The rest of your information is about as sound as that!" I snapped back at him, thanking heaven for the chance. "The murderer of Dugan has confessed and is in jail now."

The governor blinked at me. "I didn't know that," he muttered.

"Of course, you didn't!" I cried to him. "Every time they have a chance to hang a crime on the corner of my head, that makes first-page news. Every time they don't know who fired the shot that killed, they say. . . ‘Porfilo'! But when they find out the facts a couple of days later, it makes poor reading. So they stick the notice back among the advertisements."

The governor nodded. I could see him accepting my idea and confessing that there was something to it.

"Well," I continued, "I ask you to start in and look up my life. It won't be hard to do. One of your secretaries can unload the whole yarn for you in about half a day's work. Then sift out the proved things from the unproved. Give me the benefit of a doubt."

"That sort of benefit will never win you a pardon from me," he said.

"I don't want a charity pardon," I declared.

"What kind do you expect?"

"An earned one."

"Confound it," said the governor, rubbing his hands together, "I like your style. Now tell me how, under heaven, you are going to win a pardon from me?"

"You've heard of Jeffrey Dinsmore," I said.

"I have."

"Is he as bad as I am... according to reputation?"

"Dinsmore is a... ," he began. Then he shut his teeth carefully, and breathed a couple of times. "I should say that he's as bad as you are," he said between his teeth.

"All right," I said. "Here's my grand idea that brought me as close to the rope as the capital city here."

"Blaze away," he coaxed.

"Dinsmore has twenty thousand dollars on his head, same as me."

"I understand that."

"We're an even bet, then?"

"I suppose so, if you want to make a sporting thing out of it."

"All right," I said. "What's better than two badmen...."

"One, I suppose," said the governor. "But I wish you wouldn't be so darned Socratic."

I didn't quite understand what he meant, so I drilled away. "The catching of me has been a pretty hard job," I said. "It's cost the state seven years... and they haven't got me yet. But it's cost them a lot for the amount of money that they've spent hunting me."

"Besides your living expenses," said the governor with a twisted grin that hadn't much fun in it.

I caught him up on that. "My living expenses have come out of the pockets of other crooks. I've never taken a penny from an honest man. Look up my record!"

At this, he seemed really interested and sat up, rubbing his fine square chin and scowling at me—not in anger, but as if he were trying to search my character.

"Well," he said, "you are the darnedest crook I've ever heard of... with twenty thousand on your head and pretending to live like an honest man."

"For seven years," I said, rubbing the facts in on him.

"Aye," he said, "but will you insist that you've been honest all the time?"

"I helped in one robbery, and then I returned the money to the bank. You can get the facts on that, pretty easy. I had about a quarter of a million in my hands."

"If you have a record like that, why hasn't something been done for you?"

"I was waiting," I said, "for a governor that was a gentleman. And here I am."

"Ah, well," he said, "of course, I'll have to look into this. It can't be right. Yet I can't help believing you. But what is this about earning your pardon?"

"I was saying that the state had spent a good many tens of thousands on me, and there doesn't seem to be much chance of letting up on the expenses right away."

He nodded.

"And this Jeffrey Dinsmore is a fellow with lots of friends and with a family with money behind him. It will surely cost a lot to get at him."

"It will," said the governor with a blacker face than ever.

"I want to show you the shortest way out."

"I'm ready to listen now. What's in your head, young man?"

"Let Dinsmore know the proposition. I say let it be a secret agreement between you and me... and Dinsmore... that if he brings me in. . . dead or alive... you'll see that he gets a pardon, and the reverse goes for me."

The governor stared at me with his eyes enlarged. He began shaking his head.

I cut in very softly—hardly loud enough to interrupt his thoughts. "I can promise you that there'll be no living man brought in. One of us will have to die. There's no doubt about that."

"I know that," said William Purchase Shay. "I believe you, Porfilo. By the way, are you a Mexican?"

"My mother was Irish," I said. "Away back yonder, there was a dash of Mexican Indian in my father's blood."

It seemed to me that his smile was a lot easier when he heard that. Then he got up and took my hand.

"After all," he said, "one gets good laws in operation by hard common sense." He paused. "Is there anything that you need, Porfilo?"

"Wings to get out of this town," I said.

He nodded very gravely. "I don't see how the devil you got into it."

"Walked."

"While they are out looking for a man on a mule! That was the alarm that came in... from the old man you shot at. Did you shoot at him, Porfilo?"

"The old scamp was burning up the country to get to a telephone and blow the news about me. So I thought I'd give him a real thrill and I fired into the air. That's all there was to it."

"There's seventy miles between you and the mountains where you are so safe," he said.

"Open country." I nodded. "And seventy miles to Mister Dinsmore, too."

"Are you sure of that?" asked the governor with a start.

"Why, that's where the report located him."

"The report lied, then. It lied like the devil!"

He said it in such a way that I could not answer him. I held my tongue until he reached out a sudden hand and wrung mine, and his eyes were fixed on the floor.

"Good luck to you... the best of luck to you, Porfilo."

I slid through the window, and, when I looked back, I saw him standing just as I had left him, with his eyes fixed upon the floor.

Well, I couldn't make it out at the time, but I figured pretty close, and I was reasonably sure that something I had brought into his mind connected with the idea of his wife, and that was what had taken the starch out of him.

However, I was not thinking about the governor ten seconds later. For, as I dropped from the window for the ground underneath, I saw a glint like that of a star through thin clouds. But this glimmer was among the leaves of some shrubbery, and I knew that it was a touch of starlight on the polished barrel of a gun.

WELL, when you hear people speak of lightning thinking, I suppose that you smile and call it "talk"—but between the time I saw that glimmer of a gun in the bush and the instant my heels hit the ground beneath, I can give you my word that I had figured everything out.

If I were caught, people would want to know what Leon Porfilo had been doing in the governor's office. Even if I were not caught, it would be bad enough, because there would be no end of chatter all over the state. But, as a matter of fact, if I wanted to help the reputation of a man who had given me a mighty square deal, the best way for it was to cut out of those premises without using a gun or even drawing one.

I say that I thought of these things while I was dropping from the window to the ground, and I hadn't much time besides that, for, as I hit the ground and flopped over on my hands to ease the shock, I saw a big fellow with two more behind him step out of the brush and the lilacs about five paces away. Five paces—fifteen feet!

Well, you look across the room you are in and it seems quite a distance at that. Besides, I had the night in my favor. But I give you my word that, when I looked at those three silhouettes cut out against the starlit lilac bloom behind them, and when I saw the big pair of gats in the hands of the leader—and the gun apiece in the hands of the men behind—well, I knew in the first place that, if I tried to run to either side, they'd have me against the white background of the house and fill me with lead before I had taken two steps. I turned that idea over in the fifth part of a second while the leader was growling in a professionally ugly way—if you've ever heard a detective make an arrest you'll know what I mean.

"You... straighten up and tuck your hands over your head pronto!"

"All right," I muttered.

He could not have distinguished the first part of my movement from an honest surrender. For I simply began to straighten as he had told me to do. The difference was in my right hand—a five-pound stone. As my hands flew up, that stone jumped straight into the stomach of the leader.

Both his guns went off, and there was a silvery clashing of broken window glass behind me. One of those bullets was in a big scrub oak. The other had broken the window of the governor's office and broken the nose of the photograph of Shay's granddad—and drilled through the wall itself.

But the holder of the two guns threw out his hands to keep from falling, and in doing that he backhanded his two assistants. One of them started shooting blindly. The other dropped his gun, but he had enough sand and wit to make a dive for me. I clubbed him over the head with my fist, as though it were a hammer, and, very much as though a hammer had struck him, he curled up. I almost tripped over him. By the time I had disentangled my feet, the chief was shooting from the ground.

But he was a long distance from doing me any real harm. The nerves of those three were a good deal upset. I suppose, in fact, that they had not had much experience in trying to arrest men who can't afford to go behind the bars and be tried for their lives.

At any rate, I was lost among those lilacs in a twinkling. At the same time, a considerable ruction broke out in the house. Windows began being thrown up and voices were shouting, and the three detectives themselves were making enough noise to satisfy fifty.

Under cover of that racket, I didn't bolt out onto the street in the direction for which I was headed. Instead, I whirled around, and, under the shelter of those God-blessed lilacs, I tore back down the length of the yard.

I cleared the house—and still all the noise was in the rear and out toward the street. When I got into the back yard, I saw one discouraging thing—a tall fence about nine feet high and a man just in the act of climbing over. He had jumped onto a box, and the box had crumpled to nothing under him as he leaped. However, he had made the top of the fence.

I had to make the same height, without a box to jump from. Still I wondered who was the man who was trying to make his getaway even before me? I didn't stop to ask. I went at that fence with a flying leap and got my hands fixed on the top of it. With the same movement, I let my body swing like a pendulum. And so I shot myself over the top a good deal like a pole vaulter. When I let go with my hands and while I was pendent in the air, falling, I saw that the man who had gone over ahead had stumbled just beneath me, and, like a snarling dog, he was growling at me. He fired while I was still hanging in the air, and the bullet clipped my upper lip and let me taste my own blood.

It's very bad to let an Irishman taste his own blood. It's bad enough to let one who's half Irish do the thing. At any rate, I went half mad with anger. I landed on him. He wasn't big, and my weight seemed to flatten him out.

It was an alley cutting through behind the grounds of the governor's house, and there was a dull street lamp in a corner of the alley. It shed not very much light but enough to show me a handsome-faced young fellow—not made big, but delicately like a watch, you know. A sensitive face, I called it.

Then I started on. One thing I was glad of, and that was that there was a neat-looking horse tethered at the end of the alley, and from the length of the stirrups—as I made the saddle in a flying leap—I sort of thought that it might have belonged to the fellow I had just left behind me.

I cut the tethering rope with my sheath knife from the saddle, and then I scooted that horse across the street and down another alley. I pulled him up walking into the next street beyond and jogged along as though nothing particularly concerning me were happening that night. A very good way to get through with trouble. But the trouble was that there was still hell popping at the governor's house. I could hear their voices—and more than that—I could hear their guns, and so could half of the rest of the town.

People were spilling out of every house, and more than one man who was legging in the danger direction yelped at me, as I went past, and asked where I was going. But that was not so bad. I didn't mind questions. What I wanted to avoid was personal contact.

Here half a dozen fellows on fine horses took the corner ahead of me on one wheel, so to speak, spilling out all across the street as they raced the turn. When they saw me, one of them shouted: "What are you riding that way for?"

I knew that they would be halfway down the block before they could stop, and, besides, I hoped that they wouldn't be too curious if I didn't answer. So I just trotted the horse around the same corner by which they had come. But one question unanswered wasn't enough for them. They were like hungry dogs, ready to follow any trail.

"Hello!" yelled the sharp, biting voice of that same leader, to whom I began to wish bad luck. "No answer from that gent. Let's have a look at his face!"

I could hear the scraping and the scratching of the hoofs on the horses as the riders turned them in the middle of the block with cowpuncher yells that took down my temperature at least a dozen degrees.

I was not marking time. I scooted my mount down the next block. The minute he took his first stride, I knew that the race would be a hot one, no matter how well they were fixed with horses. Because that little horse was a wonder! I never put eyes on him after that night, but he ran with me like a jack rabbit—a long-winded jack rabbit, at that. My weight was such a puzzle for him that he grunted with every stride, but he whipped me down that street so fast that I had nearly turned west on the next corner before the pursuit sighted me. But I failed by the stretched-out tail of that little Trojan, and, by the yell behind me, I knew that they were riding hard and riding for blood.

I turned again at the next corner, and, as I turned, I saw that two men were riding even with me. They had even gained half a length in the running of that block. I made up my mind right away. If they had speed, they could show it in a straightway run, because it kills a little horse to dodge corners with a heavy man on his back. So I put my pony straight west up that street, running him on the gutter of the street where dust and leaves had gathered and made easier padding for his hoof beats.

In a mile we were out of the town, but those six scoundrels were still hanging on my rear and raising the country with their yells and their whoops. I could hear others falling in behind me. There were twenty now, shoving their horses along my path. And every moment they were increasing in numbers. Besides, after the first half mile, my weight began to kill that game little horse. He ran just as fast, nearly, as he had before. But the spring was going out of his gallop. Then I was saying to him: "Just hold out over the hill and into the hollow. Just over the hill and into the hollow."

Well, they were snap shooting at me as I went up that hill, and the hill and my weight together slowed my little horse frightfully. However, he got to the top of it at last, and my whistle was a blast between my fingers. Fifty yards of running down that hillside—with my poor little horse staggering and almost dying under me. My heart stood in my mouth, for, if Roanoke were gone, I was a lost man with a halter around my neck.

But, no—there he was, sloping out of the brush and heading full tilt toward me. As I came closer, he wheeled around and began to shamble away at his wonderful trot in the same direction I was riding. So I made a flying jump from the saddle of the little horse and onto the rock-like strength of the back of Roanoke.

THERE was not a great deal to the race after that. I suppose that there were half a dozen horses in the lot that could have nabbed Roanoke in an early sprint. But the little gamester I rode out of town had taken the sap out of the running legs of the entire outfit. When I left him for Roanoke, that old mule carried me up the course of the hollow—where water must have stood half the year, by the tree growth—and, after he had run full speed for a few minutes, they began to drop back behind me into the night.

The moment I noticed that, I dropped Roanoke back to his trot. Galloping was not to his taste, but he could swing on at close to full speed with that shambling trot of his and keep it up forever. It did not take long. The hunt faded behind me. The yelling began to grow musical with the distance, and finally it died away—first to an occasional obscure murmur in the wind, and then to nothing.

I think we did thirty miles before the morning sun was on us. Then I put up and spent another hungry day in a clump of trees. But food for Roanoke, not for me, was the main thing at that time. When the day ended, I sent that old veteran out to travel again, and we were soon in the mountains, soon climbing slowly, soon winding and weaving ourselves up to cloud level.

Until I got to that height, back in my own country, I did not realize how frightened I had been. But now that the mischief was behind me, I felt fairly groggy. I sent one bullet through a pair of fool jack rabbits sitting side by side, the next morning, behind a rock. They barely made a meal for me. I could have eaten a hind quarter of an ox, I was so hungry. I kept poor Roanoke drudging away until about noon. Then I made camp and spent thirty-six hours without moving.

I always do that after a hard march, if I can. It is always best to work hard while there's the least hint of trouble in the offing, but, when the wind lets up, I don't know of a better way to insure long life and happiness than by resting a lot. I was like a sponge. I could work for a hundred hours without closing my eyes, but, at the end of that time, I could sleep two days, solid, with just enough waking time to cook and eat one meal on each of those days. Roanoke was a good deal the same way. We spent a day and a half in a sort of stupor, but the result was that, when we did start on, I had under me an animal that wasn't half fagged and ready to be beaten, but a mule with his ears up and quivering. My own head was rested and prepared for trouble.

I hit for my old camping ground—not any particular section, though, I knew every inch of the high range, by this time—the whole wide region above timberline—a bitter, naked, cheerless country in lots of ways, but a safe one. For seven years, safety had to take the place of home and friends for me. An infernal north wind began to shriek among the peaks as soon as I got up there among them. But I didn't budge for ten wretched days or more. I spent a shuddering, miserable existence. There is nothing on earth that comes so close to above timberline for real hell! I've heard naturalists talk about the beauties of insects and birds and what not above the place where the trees stop growing. Well, I can't agree with them. Perhaps I haven't a soul. But those high places make me pretty sick. When I see the long, dark line of trees end that cuts in and out among the mountains like the mark of high water, it sends a chill through me.

But for seven years I had spent the bulk of my life in that horrible part of the world. Seven years—eighteen to twenty- five. And every year before twenty-five is twice as long as every year after that time.

Well, I stayed in the old safe level, as I have said, about ten days. Then I dropped Roanoke five thousand feet nearer to civilization and stopped, one day, on the edge of a little town—right out between two hills where there was a little shack of a cabin standing. I knew that cabin, and I knew that the man inside it ought to know me. I had stayed with him half a dozen nights, and every time I used his house as a hotel, he got ten or twenty dollars out of me. Because that was one of the rules of the game. If a longrider struck up an acquaintanceship with one of the mountaineers, we always had to pay for it through the nose, in the end.

However, I couldn't be sure that old man Sargent hadn't changed his mind about me. I left Roanoke fidgeting among the trees on the hillside, for he could smell the sweet hay from the barn at that distance and his mouth was watering. Then I slid down the hill and peeked through the windows. Everything seemed as cheerful and dirty and careless as ever. Sargent had two grown-up sons. The three of them put in their time on a place where there wasn't work enough to keep one respectable two-handed man busy. There wasn't more than enough money for one man, if he wanted to be civilized. But civilization didn't harmonize with the Sargents. They wanted to live easy, even if they had to live low.

When I saw that there wasn't any change in them, I took Roanoke to the barn and put him up where he could eat all the hay he wanted. Because you can trust a mule to stop before the damage mark—which is a trust that you can't put in a horse.

Then I went to the house and the three of them gave me a pretty snug welcome. Old man Sargent insisted that I take the best chair—his own chair. He insisted, too, that I have something to eat. I had had enough for breakfast to last a couple of days, but I let out a link and laid into some mighty good cornbread and molasses that he dished up to me along with some coffee so strong that it would've taken the bristles off of pigskin.

I said: "How long ago did you make this coffee, Sargent?"

"I dunno," he said.

"He swabs out the pot once a month," said one of the boys, grinning, "and the rest of the time, he just keeps changing the brew, a little. A little more water... a little more coffee."

Well, it tasted like that, sort of generally bad and strong—mighty strong. I put away half a cup, just enough to moisten the cornbread that I swallowed.

"Have you come down to get Dinsmore?" said Bert Sargent.

The name hit the button, of course, and I turned around and stared at him.

"Why, Dinsmore has been setting waiting down in Elmira for three days," old man Sargent said.

"Waiting for what?" I asked. "I've been up in the mountains and I haven't heard."

Of course, they were glad enough to tell. Bad news for anyone else was good news for those rascals. It seems that Dinsmore had appeared suddenly in the streets of Elmira. At noonday. That was his way of doing things—with a high hand—acting as though there were no reason in the world why he should expect trouble from anyone. He went to the bulletin board beside the post office and there he posted up a big notice. He had the roll of paper under his arm, and he tacked it up with plenty of nails, not caring what other signs he covered. Well, sir, the reading of that sign was something like this:

ATTENTION, LEON PORFILO!

I want you, not the twenty thousand.

If you

want me, you can expect that I'll

be ready for you any day

between three and

four if you'll ride through Main

Street.

I'll let you know which way to shoot!

Jeffrey Dinsmore

I don't mean to say that the Sargent family told me this story with so little detail. What they did do, however, was to give me all the facts, among the three of them. When I had sifted those facts over in my mind, I stood up. I was so worried that I didn't care if they saw the trouble in my face.

"You don't like this news so well as you might, partner?" old Sargent said very smooth and swallowing a grin.

I looked down at that wicked old loafer and hated him with all my heart. "I don't like that news at all," I admitted.

The three of them exclaimed all in a breath with delight. They couldn't help it. Then I told them that I was tired, and they showed me to a mattress on the floor of the next room. I lay there for a time trying to think out what I should do, and all the time I could hear whispers of the three in the kitchen. They were discussing with vile pleasure the shock that had appeared in my face when I had been told the news. They were like vultures, that trio.

Well, I was tired enough to go to sleep, anyway, after a time. Then I wakened with a start and found that it was daylight. That was what you might call a real hundred percent sleep. I felt better, of course, when I got up in the morning, and in the kitchen I found old man Sargent with his greasy gray hair tumbling down over his face and his face as lined and shadowed as though he had been drinking whiskey all the night. I suppose that really low thoughts tear up a man's body as much as the booze.

He gave me a side look as sharp as a bird's to see if there was still any trouble in my eyes, but I put on a mask for him and came out into the kitchen singing. All at once, a sort of horror at that old man and at the life I had been leading came over me. I hurried out of the house and down to the creek. It was ice cold, but I needed a bath, inside and out, I felt. I stripped and dived and climbed back onto the creekbank with enough shivers running up and down my spine to have done for a whole school of minnows. But I felt better. A lot better.

When I went back to the house for breakfast, I saw that one of the two boys was not on hand, and I asked where he was. His father said that he had gone off to try to get a deer, but that sounded like a queer excuse to me. I couldn't imagine a Sargent doing such a thing as this, at this hour in the morning. I began to grow a little uneasy—I didn't exactly know why.

After breakfast, as I left, I offered the old rat a twenty- dollar bill, and he took it and spread it out with a real gulp of joy. Cash came very seldom into his life.

"But," he said at last, peering at me hopefully and making his voice a wheedling drawl, "ain't I give you extra important news, this trip? Ain't it worth a mite more?"

I was too disgusted to answer. I turned on my heel and left, and, as I went out, I could hear him snarling covertly behind me.

HOWEVER, I didn't like to fall out with the Sargents. I knew that they were swine, but, after all, I might need their help pretty early and pretty often in the next few years of my life.

I went out to Roanoke and sat in the manger in front of him, thinking or trying to think, while the old rascal started biting at me as though he were going to make breakfast off me. I decided, finally, that the only thing for me was to head straight for Elmira and take my chances there, because if I didn't meet Dinsmore right away, my name would be pretty worthless through the mountains. Besides, it was the very thing I had wanted.

But I had never dreamed of a fight in a town—and a big town like Elmira, that had everything in it except street cars. It had a four-story hotel, and a regular business section, and four streets going east and west. There were as much as fifteen hundred people in Elmira, I suppose. It was a regular city, and it seemed a good deal like craziness to try to stage a fight in such a place. As well start a chicken fight in the midst of a gang of rattlesnakes. No matter which of us won, he was sure to be nabbed by the local police right after the fight.

I wondered what could be in the head of Dinsmore, unless he had an arrangement with the sheriff of that county to turn him loose, in case he were the man who won the fight. I decided that this must be the fact, and that worried me more than ever. However, there wasn't much that I could do except to ride in and take my chances with Dinsmore. But one of the bad features was that I had never seen Dinsmore, whereas everyone had had a thousand looks at me in the posters that offered a reward for my capture.

Well, I saddled Roanoke and started down the Elmira trail. The first cross trail I came to, there I saw a board nailed on the side of a fence post and on the board there was all spread out a pretty good poster which said:

DINSMORE... TWENTY THOUSAND DOLLARS REWARD.

I made Roanoke jump for the sign to see the face in detail. It was rather a small photograph, but it was a very clear one, and I was fairly staggered when I leaned over and found myself looking into the eyes of the very same fellow who had climbed the back fence of the governor's house a second before me on that rousing night in the capital city. That was Dinsmore!

It wasn't a very hot day, but I jumped out of the saddle and sat down under a tree and smoked a cigarette and fanned myself and did some very tall damning. It was all a confusing and a nasty mess, of course. A mighty nasty mess. I hardly dared to think out all of the ideas that jumped into my mind. There had been the anger of the governor when I mentioned the name of Dinsmore. There had been a sort of savage satisfaction when I suggested that the other outlaw and I shoot it out for the pardon. That, together with the unknown presence of Dinsmore at the house—and the pretty face of the governor's wife—well, I was fairly done up at the thought, you may be sure.

I could remember, too, that Dinsmore, though he had always been a fighting man, had never been a complete devil until about a year before—which was about the date of the governor's marriage. I don't mean to say that I immediately jumped to a lot of nasty conclusions. But a great many doubts and suspicions were floating through the back of my brain. I didn't want to believe a single one of them. But what could I do?

The first thing was to throw myself on the back of Roanoke and go down that hillside like a snow slide well under way. Blindly as a slide, too, and the result was that as I dipped out of the trees and came into the sunny, little, open valley below, I got two rifle shots squarely at my face. I didn't try to turn Roanoke aside. I just jammed him across that clearing with the spurs hanging in his flanks, and I opened fire with both revolvers as I went, firing as fast as I could and just in a general direction, of course.

Well, I got results. Snap shooting is always a good deal of a chance. This snap shooting into the blind brush got me a yelp of pain that meant a hit and was followed by a groan that meant a bad hit. After that, there was a considerable crashing through the brush, and I made out at least three horses smearing their way off through the underbrush. But what mostly interested me was that the groaning remained just as near and just as heavy as before. So I went in search of it, and, when I came to the place, I found a long fellow in ragged clothes lying on his face behind a shrub. I turned him over and with one look at his yellow face I knew that he was dying.

It was young Marcus Sargent. I knew at once why he had been missing at the breakfast table. They had guessed that I would head straight for Elmira, now that I had the news. So young Marcus thought of the twenty thousand dollars and decided that there was no reason why he should not dip his hands into the reward. He wasn't a coward. He was in such pain that it changed his color, but it didn't keep him from sneering at me in hate. When you wrong a man, hate always comes out of it—on your side. But I didn't hate him, in turn. I merely thanked heaven that he had missed—and I didn't see how he had, because I'd watched him ring down a squirrel out of a treetop many a time.

"How did you happen to miss?" I asked him. "Handshake, Mark?"

The first thing he answered was: "Am I done for?"

I answered him brutally enough: "You're done for. You can't live two minutes, I suppose... that slug went through you in the spot where it would do me the most good."

"You're a lucky swine," said Marcus. "Well, anyway, I dunno that life is so sweet that I hate the leavin' of it. But over in Elmira... if you should happen to run across Sue Hunter, hand her my watch, will you? Tell her it's from me. You'll know her by her picture inside the cover."

I hated nothing in the world more than touching that watch. But I did it, at last, and dropped it into my pocket.

Marcus didn't want to die before he had done as much harm as he could. He turned on his own family, saying: "It wasn't me alone. The whole three of us talked it over last night."

"Look here, Mark," I said, getting a little sick as I watched his color change, "is there anything I can do to make you more comfortable?"

"Sure," he said, "lend me a chaw, will you?"

But before I could get it for him he was dead.

I didn't like this affair for a lot of reasons. In the first place, I've never sunk lead into a man without hating the job. Although I've had the necessity or the bad luck of having to kill ten times my share of men, there was never a time when I didn't loathe it, and loathe the thought of it afterward. But that was only half of the reason that I disliked this ugly little adventure in the hollow. I had a fair idea that the two or three curs who had ambushed me with young Sargent would now ride for Elmira full tilt and tell the sheriff of what they had tried to do and of where they had last seen me. So, in two or three hours, the sheriff might be setting a fine trap for me in the town.

Of course, I only needed a moment of thought to see that was a foolish idea. No matter how little the people esteemed me, they would not think me such a perfect idiot as to ride on toward the town after I knew that a warning was speeding toward it in the form of three messengers. No, the sheriff was really not very apt to lay a plot for me in the town. Rather, he was pretty sure to come foaming down to the place where I had been seen and try to follow my trail from that point. Well, I decided that, if that were the case, he could pick up my trail if he cared to and follow it right back to his own home town.

In short, my idea was that, when people heard I had appeared so close to Elmira, every gun-wearing citizen would take a turn on his fastest horse and treat himself to a holiday hunting down twenty thousand dollars' worth of "critter". I believed that town would be well cleaned out and that the best thing I could do was to drive straight for Elmira itself, simply swinging a little wide off the main trail. Perhaps nine-tenths of the fighting men would be out hunting me when I reached Elmira, hunting Jeffrey Dinsmore.

Jeffrey Dinsmore, slender and delicately made, and as handsome for a man as the governor's wife was lovely as a girl. Thinking of her and of Dinsmore, I could understand why it was that Molly O'Rourke was only pretty and not truly beautiful. Molly might grow plain enough in the face in another ten years, but the governor's wife was another matter. She would simply become charming in new ways as time passed over her head. There was something magnificent and removed and different about her. She was the sort of a person I wondered any man could ever have the courage to love—she seemed so mighty superior to me. Well, you can guess from all of this that I wasn't in the most cheerful frame of mind in the world until, about two hours afterward, I looked through a gap in the trees and the brush, and I saw about a hundred men piling down the hillside in just the opposite direction and knew that I had guessed right.

ELMIRA had turned out its best and bravest to swarm out to the place where my trail had been found and lost by those three heroes who accompanied young Mark Sargent. They had a long ride before them, and, no matter how fast they spurred back toward Elmira, they were not apt to arrive there until many hours after I had passed through. My chief concern now was simply lest there still remained too many fighting men in the town. But I was not greatly worried about that. I felt that I had reduced the dangers of Elmira to a very small point. The danger that remained was from Dinsmore alone. How great that danger was I could not really guess. It was true that he had established a great reputation for himself in Texas, but before this I had met with men of a great repute in distant sections of the country, and they had proved not so deadly on a closer knowing. Furthermore, when one has picked up another man and dropped him on the pavement, one is not apt to respect his prowess greatly. Which may explain fairly thoroughly why I thought that I could handle Mr. Dinsmore with ease.

I did not think, however, that he would be prepared for me in Elmira. I thought that I probably would be permitted to canter down the street unobserved by Mr. Dinsmore, because, if the entire town was so busy hunting me, it seemed illogical that I should drop into Elmira. I expected to canter easily through the town, with only the danger of some belated storekeeper or some old man seeing and knowing me, for the rest of the town seemed to be out in the saddle.

Of course, I hoped that Dinsmore would not be on hand, because after I had answered his first invitation and he failed to appear, it would be my turn to lead, and I could request him to appear at any place of my own selection. The advantage would then be all on my side.

Outside of the town I stopped for a time. I let the mule rest, and I took it easy myself. I had a few hours on my hands before the appointed time to show myself to little Dinsmore in the town. However, though Roanoke rested well enough, I cannot say that my nerves were very easy. The time was coming closer, faster than any express train I ever watched in my life. The waiting was the strain. Whereas Dinsmore, knowing that the fight might come any day, paid no heed, but could maintain a leisurely look- out—or none at all.

A pair of eternities went by at last, however. Then I swung onto Roanoke and started him into the town. Everything went on about as I had expected it. The town was emptied of men. The first I saw was an old octogenarian with his trousers patched with a piece of old sack. The poor old man looked more than half dead, and probably was. He didn't lift his head from his hobble as I rattled by. The first bit of danger that came into my way was signaled by the screaming voice of a woman.

"There goes Leon Porfilo! There'll be a murder in this town today!"

It wasn't a very cheerful reception, take it all in all. But I pulled Roanoke back to an easy trot, and then I took him down to a walk, because I saw that I was coming pretty close to the place of the rendezvous. When I passed that place—although I wanted most terribly to pass it fast—still I had to be at a gait from which a man can shoot straight—and I've never yet seen anyone but a liar that could come near to accuracy from a trot or a gallop. Try it yourself—especially with a revolver—and see what happens. Even a walking horse is bad enough. It's hard when the target is moving; it's a lot harder when the shooter is in motion.