RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

All-Story Weekly, 13 July 1918, with "Devil Ritter"

Fantastic Novels, May 1949, with "Devil Ritter"

A power more than human, a will to absolute evil--such was he. All who had tried to save her from him perished... Must her true love also die?

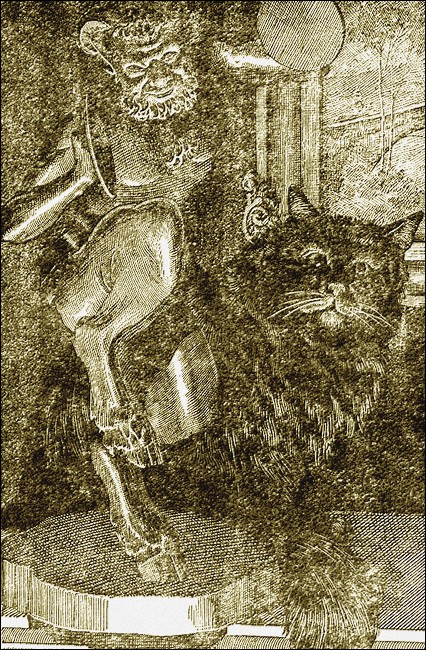

Detail from Headpiece in "Fantastic Novels"

Abdallah cowered behind the bric-à-brac,

safe, at least, from the eyes of Devil Ritter...

WHEN a man is stretched out in a comfortable chair with his feet propped on the back of another, a good book in his hands and silver drifts of smoke rising from his pipe to tangle under the shade of a reading-lamp, it requires nothing less than a catastrophe to recall his attention and make him change his position.

Jim Crawley did not change his position, but he looked up from his book with a scowl and stared at the ceiling. A soft, hurried footfall sounded from the room above, a continuous padding sound like the tread of a cat. All that evening, the night before, the night before that, for a week he had heard this ceaseless walking with a slight creak at regular intervals as the man turned at either end of the room. Crawley removed his pipe, blew a thin stream of smoke into the air and decided gravely: "Insomnia or plain nerves."

In spite of this solution the continued sound troubled him. He was glad when it broke off, a door closed overhead, and the stairs of the old lodging-house groaned under a descending step. He glanced a comfortable eye over his room where the spoils of his many wanderings lay here and there, and then went back to his reading.

For perhaps half an hour his peace was unbroken, then the door flew open and a man jumped into the room, shutting the door quickly but noiselessly behind him.

Crawley sprang up from his chair with an exclamation.

The other stared at him with an odd expression, half fear and half horror, and whirled back to the door with a cry. Before he could open it Crawley had him by the shoulder; under his ample grip he seemed to feel the shoulder of a skeleton—there was no suggestion of flesh to his touch. The slightest motion of his arm sufficed to jerk the stranger back against the wall where he flattened himself, one hand clutching at the smooth surface for support, the other hand clutching at an inside pocket of his coat. Crawley seized that hand and yanked it out. It came bearing a heavy automatic. He tore it easily from the nerveless fingers of the owner.

"Now what in hell—" he began, and stopped short.

The other man was trying to speak, but only a faint whisper came from his white lips.

"Out with it!" said Crawley.

"I seem—I seem," stammered the man, "to have come to the wrong room."

"With a gun," finished Crawley.

The other reeled where he stood, and a sudden pity took hold of Crawley He half carried the man to a chair, propped him up in it, and forced him to swallow a stiff drink of brandy.

"What is it?" he went on in a gentler voice. "Were you up against it, my friend, and decided to get the price of a meal at the point of a gun? I'm not very flush myself, but I have enough to—"

He stopped short, for he had taken another glance at the gun. It was of the most expensive make, and the handle was heavily chased with gold. Any pawnbroker would give fifty dollars for such a weapon. He looked curiously at the thin face of the stranger, now not quite so colorless.

"It has been simply a childish mistake on my part," said the man, making a visible effort to seem at ease. "Here is my card. I have the room just above this on the third floor. I—I simply mistook the rooms in—in a fit of absent-mindedness. And then at the shock—I mean the surprise of seeing someone in the room—"

He had to break off, for his voice was as unsteady as the hand which extended a card to Crawley. It bore the name of Vincent Cadmon Noyes. Crawley hesitated a single instant. Then he reached out his large brown hand and shook with the stranger.

"Glad to know you, Mr. Noyes. My name is Crawley—Jim Crawley."

The cold, slender hand pressed his slightly. Noyes rose.

"You'll forgive my foolishness?" he said with an uncertain smile.

"If you'll pardon my roughness," answered Crawley, "we'll call quits. Will you stay awhile?"

Noyes dropped back into the chair. There was a strange thankfulness in his eyes as he accepted the invitation.

"I'm very glad to," he said. And then by way of explanation, "it's hard to leave such a comfortable chair when one's fagged. And I'm worn out."

"No wonder," said Crawley, with a touch of irritation, "you walk such a lot."

A question flashed in the eyes of Noyes, but he attempted to laugh.

"Have I bothered you with my tramping up and down?"

"A little," confessed Crawley. "What is it? Insomnia?"

"No," said Noyes, and then hesitated; "yes, I think it's as much insomnia as anything else."

He shifted his eyes about the room, evidently intent on finding some new subject for conversation. For an hour he maintained a broken talk about little or nothing. Nevertheless Crawley was not bored. There was a singular atmosphere about Noyes which fascinated him. It lay in nothing that he said—it was rather an indefinable and sinister emotion which the lean, white face and the haunted eyes inspired. One detail of his actions peculiarly caught the attention of Crawley. His visitor had moved the chair until it directly faced the door. By so doing he brought his face in the full glare of the electric light, but when Crawley suggested another position, he shook his head and insisted that he was too comfortable to move. It was quite late before he rose.

"Good night, Mr. Crawley," he said. "You've given me the first pleasant evening I've had in—" He stopped short, and then went on, "May I come down to see you again?"

"Glad to have you," said Crawley heartily. "Hope you get rid of that—er—insomnia."

"Thanks," responded Noyes, "I think—"

He broke off with a sharp gasp and clutched Crawley frantically by the arm while he stared up at the ceiling.

"In the name of Heaven, man—" began Crawley angrily.

"Hush! Hush!" whispered the other. "Didn't you hear it?"

"Hear what?"

"The footstep in my room!"

"Look here, Mr. Noyes, you let your imagination run away with you. There wasn't any sound from the room above us."

"I tell you there was! There was! I heard it! They're in my room waiting—"

"Who are in your room? Come, come; this is childish!"

Noyes relaxed his hold on Crawley's arm, but he had to lean his weight a moment against the back of a chair. He drew out a handkerchief and wiped his forehead.

"You are—are sure you heard nothing?" he asked, stammering.

"Not a thing in the world."

Noyes turned to him with a sick smile.

"Perhaps you are right. It was just my imagination. Good night again."

"Good night."

He went to the door and hesitated, with his hand upon the knob.

"I say, Noyes," said Crawley, a little more gently than he had spoken before, "do you wish to have me go up to your room with you—just to make sure that they are not up there waiting for you?"

Noyes turned to him with an almost ludicrous gratitude.

"God bless you," he said "If you will—"

"Of course," said Crawley, and he started out up the stairs after the younger man, muttering to himself, "plain neurasthenia—have to be gentle with such a fellow!"

AT the door of Noyes' room he paused and banged loudly. An instant of silence followed, and then a peculiar spitting sound. Crawley set his square fighting jaw and reached a hand toward the trembling Noyes.

"Give me that revolver," he said.

"Is there—is there anyone there?" asked Noyes in a shaken voice.

"I don't know," said Crawley, "but I'll find out in half a second."

He flung the door open and made a single crouching step, the revolver poised. A great, black Persian cat stood in the center of the floor, with back bowed and hair bristling. Perhaps it was the green shade of the lamp which made the animal's eyes seem of that color.

The big cat spat at him.

"Nothing but a fool cat," said Crawley, drawing a long breath. "Noyes, I must have caught some of your nerves from you."

"Abdallah!" said Noyes. "No one but Abdallah!"

He entered the room with a cautious manner.

"You say that as if the cat were a human being," Crawley said, smiling.

The other made no answer. His hand was at the knob of a closet door. He threw it open with a quick gesture and stepped back hastily from before the dark opening, into which he peered.

"What's the matter?" asked Crawley, with a contempt which he could not entirely keep out of his voice.

"I—I merely want to put my hat away," said Noyes, and accordingly he tossed his hat upon the shelf inside the closet. When he turned he cast a shrewd glance at the bed. Something told Crawley that as soon as Noyes was alone he would take a careful look under that bed.

"Now, my friend," said Crawley, "better trust in me. Tell me, who are 'they' you mentioned awhile ago?"

Noyes started, but made a strong effort to pretend he did not hear the question. Instead he pointed.

"Well, well!" he said. "Abdallah has started to make friends with you already!"

The big Persian was rubbing affectionately against Crawley's knees.

"Sure," said the latter. "I always get along well with animals."

"Yes, but Abdallah is a little different. Quite a lot different from other animals. Won't you sit down awhile? Here's a box of rather good Havanas"—he lighted one as he spoke—"there's a siphon and a bottle of Scotch at your elbow and if there's anything else you want to be comfortable, perhaps I can get it for you."

"Thanks," said Crawley, sitting down and selecting a cigar from the box beside him. "I won't drink just now. What makes the cat different from other animals, Noyes?"

His host laughed a little constrainedly.

"Some people in India have an idea," he said, "that when a human soul transmigrates into an animal, once in a million times it carries some of the human qualities of mind and thought with it—along with other weird powers."

"Transmigration of the soul?" queried Crawley dryly "Bunk, my dear fellow. Who's managed to fill you up with that sort of rot?"

The other man shrugged his shoulders, but his face remained serious.

"Rot? Yes, it may be all rot. I don't know. I'm merely telling you what has been told me. The original owner of Abdallah declared that the cat was one of those peculiar freaks which possessed human qualities."

"Humph!" grunted Crawley, and he stretched his muscular hand toward the Persian. "Come here, Ab, and help me enjoy a laugh at that theory of your master." The cat, which up to that time had remained fawning about the feet of Crawley, now turned its back and walked toward Noyes, who regarded Crawley with a quiet smile of triumph.

"I suppose," said the big man, "that you take that as a sign that the cat understood what I said?"

"No, no! Not that—entirely. Even the queer chap who used to own this cat didn't think that of him. What he did claim was that the cat caught a very vivid impression of—how shall I call it?—of psychic states."

"That so?" said Crawley, totally disinterested. "Just what do you mean by that?" Noyes regarded him with cautious eyes, as if seeing how far he might bare his soul to this stranger.

"Some people think," he said at last, "that the soul is more or less divorced from the body even during life, do you see?"

"Go ahead," smiled Crawley, "it sounds interesting anyway."

"Exactly. Well, they go on to maintain that when the mind thinks it actually goes in presence to the object of which it thinks."

"Do you mean to say," said Crawley, irritated, "that they mean that when I think of the Philippine Islands one second and of the city of London in the next instant, my mind has actually gone to those places?"

"You laugh, of course," said Noyes, in a tone of slight disappointment; "but that's exactly what they mean. Of course it's an absurd idea, isn't it? For instance, they hold that if you think of a person in London, that person, if he be peculiarly gifted in his perception, will know you are thinking of him, for he will feel the actual presence of your aura. In fact, they go so far as to say that quite exact thoughts can be read at a great distance."

"Nonsense!"

"Of course it's nonsense. But after all, Mr. Crawley, there's really nothing more wonderful in this than there is in wireless telegraphy."

"Well, let's get back to this wonderful cat."

"To be sure, Abdallah."

The cat had curled up at his master's feet and lay watching Crawley with steady eyes.

"That's what the owner claimed for this cat. He swore that Abdallah could distinguish the presence of the thoughts of others. By the way, I've never seen him take such a fancy to anyone as he takes to you."

"Come here, Ab," said Crawley, by way of a test.

The big cat rose like a trained dog and walked to him, jumped up to his lap, and lay curled there, purring like a small buzz-saw and digging his claws carefully into the trousers leg.

"Well, I'll be damned!" exploded Crawley.

The cat turned and looked him in the face with uncanny gravity. It gave Crawley an immense desire to change the subject.

"You've been in India?" he asked.

"Most of my life."

"I've roamed about a good deal, but never landed there. Hope to some day. What part do you come from?"

"Burma. Here, I'll show you a picture of my place. My eye, how I'd like to see it!"

He went to a trunk in the corner of the room, opened it hastily, and from an upper rack pulled out a handful of papers. Of these he selected one and turned to Crawley. As he did so one of the papers fell from the trunk to the floor. It was the photograph of a remarkably beautiful young girl, whose grave eyes stared directly up at the big man.

"Here's the house," said Noyes; "one of the coolest places in Burma, on my word."

"Humph," said Crawley, "I'm more interested in the picture of that girl. Will you tell me who she is?"

He pointed toward the photograph. Noyes turned to the picture, then with a low cry picked it up and threw it back in the trunk. When Crawley saw his host's face again, it was deathly pale. The Persian jumped from his lap and stood in front of its master, staring up to him and switching its tail slowly from side to side. Noyes crossed to the table and poured a stiff drink of the Scotch, but Crawley paid little attention to him. He was too busy trying to decipher to his own satisfaction that low cry of Noyes. It had sounded like the word "Ires." He decided that it must be "Iris," for that was a girl's name. He rose.

"I won't bother you any longer this evening," he said. "Good night, Noyes."

The other came to him and took his hand. His face was still white.

"You'll think me an awful rotter, won't you? These frights of mine— At least, I wish you'd come up to see me once in a while. I grow devilish—lonesome!"

Crawley muttered a nondescript answer and passed through the door. He was wondering if "Ires" or "Iris" was one of "they."

THAT night and the next day the face of Ires or Iris, whichever it was,

stayed constantly in the thoughts of Crawley. For the first time in many

months he felt a deep discontent with his wandering life in which periods of

action were like rare oases in a vast desert of inactivity. When the evening

came he had to fight against the temptation of going up to Noyes' room. The

memory of the horror Noyes showed at the sight of the picture helped to keep

him away. It was not likely that the man from India could be induced to speak

of the girl.

Crawley stayed in his room, filled with an unreasoning, sullen anger against his own weakness. His book could not interest him. He tried three pipes in succession and found them all tasteless. Finally he went to bed early to escape from the oppressive loneliness. In the morning he would make plans for leaving New York.

A dream of women's faces and a voice repeating "Ires, Ires," over and over, pursued him in his sleep. He woke in the middle of the night with a choking in his throat, and a faint cry in his ears. He could not make out exactly whether the cry were a part of his dream or a reality. He was quite sure, however, that it came from Noyes' room, and he knew that whether a dream or a reality it was such a cry as had never before come from the lips of a human being. Some disembodied soul in torture might have wailed in such a manner.

He lay back in bed and found himself so excited that he started to count sheep in order to call back his sleepiness. His nerves grew more and more on edge. In the black silence of the room his imagination repeated that faint, horrible cry, until his nerves were so aroused that he could almost hear the dull beating of his heart. In five minutes he was up and in a dressing-gown, for he could stand the suspense no longer. He went up to Noyes' room and knocked heavily at the door.

After a breathless interval a faint voice said, "Who's there?"

"Crawley."

"Come in!" The words came in a great relaxing breath from the room. He threw open the door. All was pitch-dark save for two phosphorescent points of light. He stepped to the center of the room, fumbled a moment, and then switched on the lamp. The light developed into Abdallah, who stood beside the bed, and in the bed Noyes was hunched up under the clothes like a frightened child. His black shadowed eyes stared across with a peculiar hopelessness at Crawley.

"What was it?" asked Crawley.

"What do you mean?"

"The sound—the damnable cry—did it come from this room?"

Noyes shuddered under the twisted clothes and extended a slim arm toward the cat. Abdallah was creeping toward the door after the unmistakable manner of a cat stalking prey. Yet he seemed alive with fear, his hair bristling and his tail switching in slow curves from side to side. At the door he crouched flat an instant and then passed his claw under the edge along the crack. After a moment he turned and fixed his round green eyes steadily upon Noyes.

"Oh, God!" moaned the man from India, and covered his face with his hands.

Crawley stepped softly to the door, threw it open, and stared into the utter dark. A breath of cool air struck his face. It was almost as if an invisible presence stood before him. He closed the door and went back to the bed.

"Noyes!" he said, and shook the man by his skeleton shoulder.

"Yes."

"Look up at me."

Slowly the haunted eyes rose to meet his inquiry.

"I can't stand this any longer. Tell me what is happening or what is going to happen here."

"You can't stand it any longer? I tell you, I've stood it for a year!"

He laughed, and Crawley felt as if someone had knifed him in the back.

"What have you stood?"

He waved his hand to the four quarters of the compass.

"This!"

Crawley understood. That was the horrible part of it. He understood, though he knew not what.

"Do you think I've been like this always?" went on Noyes. "I tell you, a year ago if I'd seen a man act like this I'd have thought what you now think of me. I can't help it! I can't help it!"

His voice rose to a wail. Crawley wiped his forehead and found it cold to his touch. He sat down on the bed beside Noyes.

"What has happened?"

"I have seen it again!"

"What?"

"Ires!"

"What does that mean? Is it a name?"

"I don't know. God or the devil understands—I don't. If I knew, do you think I'd be like this? I know I'd give a thousand pounds if Abdallah had a human voice for ten seconds!"

"There's some danger threatening you. Come, come, Noyes, be frank with me. I mean the best in the world to you."

"I don't doubt that. But what can you do? If I am helpless, you are blind. What can you do?"

Crawley opened and closed his sinewy fingers once or twice.

"I can do a good deal, my friend. I can do a surprising lot. What is Ires?"

"I have seen her again! She was clearer than ever."

"Who, Ires?"

"No, no, no!"

"In the name of God, Noyes, are you mad?"

The terror did not leave Noyes, but a certain dignity came to him. His lean hand touched the brawny fist of Crawley.

"My dear fellow," he said, "your heart is big enough for a thousand, but you cannot help me. I am doomed beyond help or hope."

"By Ires?"

"I don't know."

Crawley ground his teeth. It seemed impossible to make any headway.

"Tell me one thing, Noyes, and I'll ask no more."

"Aye, ask a thousand things, so long as you'll stay here and talk. But in the name of mercy, don't leave me!"

At the very thought of such a catastrophe Noyes was a shaking wreck again.

"Is that girl whose picture I saw last night named Ires?"

Noyes regarded him with a pity which for a moment conquered his terror. "Are you interested in her, Crawley?" he asked.

"I am!"

"Then God help you!"

"Don't look at me as if I had one foot in the grave, Noyes. I tell you I'm interested in her. What of that?"

The man from India clutched the shoulder of the big fellow in both hands.

"Cut the thought of her out of your heart. Take a ship and go to sea. At least she will not follow you!"

"Tell me seriously, Noyes. Is she the leader of some crew of cutthroats?"

"No, no! Crawley, she's the loveliest, the purest-hearted girl in the world."

"I believe you," said Crawley with tremendous earnestness.

"But you must shun even a thought of her as you would shun the thought of the devil. There's ruin in it, Crawley; horrible ruin—like mine!"

He jumped out of his bed with one of his spasmodic bursts of activity, crossed the room in his pajamas, and took a picture from a bureau drawer. He handed it to Crawley, who saw a handsome boy of twenty-two or three with big smiling eyes.

"Guess who it is?"

"Some friend of yours, Noyes?"

"Yes. Myself."

"Tut, tut! My dear fellow—look—the picture is dated a year ago or a little over. You're ten years older than this boy."

"It was the girl—the girl of the picture, Crawley. She changed me. Yes, I'm a hundred years older than that boy, but one year ago I was he!"

Crawley stared at him for a long moment and saw that he spoke the truth.

"At least tell me who she is."

"I don't dare. I tell you, if a hundred armed men were around me all sworn to protect my life, I wouldn't dare to tell you who and what she is."

Crawley got up to pace the room. His brain was so confused that no two thoughts followed in consecutive order. Even admitting that this poor fellow's mind was badly disarranged, there was still a certain earnestness which made his words convincing.

"If you will not tell me of her," he said, at last, "tell me of Ires."

"It is a dream. Five nights—seven nights I have dreamed it, more and more clearly. This night it was a sunshine reality. Therefore I know that I am about to die."

Crawley shivered, started to speak, and then decided to hold his comments till the end.

"It begins with her—the girl of the picture," said Noyes. "She leans over my bed and smiles and beckons to me. I rise and follow her. We go down to the street. Then the dream goes blank. When it brightens again we stand in front of a house. I see it very clearly. I can almost make out the number over the door. Above the house are the burning letters: 'I-R-E-S.' Mr.—ah—Crawley, the horror, the cold, fearful horror that comes over me when I see those letters—those yellow letters of fire! I stand there for a long time. I look down to the girl. She is gone—she has vanished from my side—I know that I am left alone in the power of—I know that in this house I shall die. Somewhere in that house my dead body shall be found. And at that point I wake from my dream!"

He sank down upon the bed, his head drooping.

"If you are afraid—" began Crawley.

"I do not fear death. Death is merciful. One touch, and there is the end. But this fearful expectancy—this horrible, long-drawn delay. It is that which maddens me. It is that which had changed me from the boy of that picture to—to this nameless thing you see, Crawley. Once, I was strong, almost as you. But the dropping of the water day by day, a drop an hour, will drive a man mad in time."

"If the danger approaches you," cried Crawley, "pack up your trunk and flee. Take the ship you recommended to me. Take a train. Get away from that power you speak of!"

Noyes smiled faintly.

"I have fled all the way from India, and she has followed me."

"Who?"

"The girl—the girl of the picture."

"Go to the police. Tell them. They will see that you are protected.

"I told the police in London. They laughed at me. If I had persisted in my story, they would have had me locked up as insane. Crawley, there is not a soul between heaven and hell who will believe my story. A year ago I would have laughed at it myself!"

"Noyes, there comes the morning in at the window. I am going back to my room. Do you mind? If you wish I shall stay here and talk longer with you."

"Go if you wish, Crawley."

"In the name of Heaven, man! Don't say it that way. Buck up. Put out your jaw. Fight! In a month you'll—you'll laugh at yourself!"

The daylight seemed to have restored some of Noyes' courage. He looked at Crawley with merely a weary despair.

"Adieu, my dear fellow," he said.

Crawley crushed his hand in a strong grip and went to the door. There Noyes overtook him and touched him on the shoulder.

"On second thoughts," he said with his faded smile, "I think we had better say 'Good-by!'"

"Rot!" exclaimed Crawley. "I'm going out today, and this evening I'll be at the theater. After that I'll come home and we'll have a Scotch and soda together."

He went down to his room, not to attempt to sleep, but to sit with his head in his hands thinking, thinking, thinking. One by one he added up the details Noyes told him. Sometimes in this way it was possible to draw a conclusion which would not occur at the first moment. The beautiful girl, the word Ires, the strange powers of Abdallah, the uncanny power which pursued Noyes—what was that power? Obviously it could not consist of the girl alone, for Noyes had referred to that power on several occasions as "they." Perhaps there were men associated. There must be men. If so, what was their nature, and how many were there? He should have many questions to ask Noyes that night. Granted half an hour of frank conversation and he vowed that the mystery would be a mystery no longer. What made him doubt his ability to solve the puzzle was the picture of Noyes as he had been only a year before; a strong, cheerful face now turned to the hollow-eyed wreck he knew. No dream of fear could accomplish such a change in such a man. All day the queer affair haunted his mind.

At the theater that night he saw the figures on the stage through a haze, while the forms of Noyes and the girl of the photograph played before his mind. He could not rid himself, in particular, of the voice of Noyes as he said good-by.

He tried to convince himself that it was merely the causeless melancholy of a neurasthenic, but an unreasoning depression filled him with the memory. After the theater he was in such haste to return to Noyes and shake hands to be sure that the man from India was still in the flesh, that he took a taxicab.

TOO many thoughts occupied his brain, so many weird conjectures, that he fell into that peculiar mood in which man's senses grow acutely aware of all that passes around him, but the facts are telegraphed slowly to the mind. In this absent-minded way he saw two men help a third from the door of a limousine which stood at a curb, and then walk up the stairs with him. The man in the center was evidently very drunk, for his head tilted loosely forward, and his whole body hung helplessly on the arms of those who assisted him. Two pedestrians who passed at the moment turned their heads and laughed at the spectacle.

Crawley smiled to himself, but he had noted the incident rather with the mind than with the intelligence. The car ran on for a couple of blocks when Crawley, glancing again out of the window of the taxi, suddenly called out to the chauffeur to stop.

Far away, looking down a side street, he saw the great electric sign, "United States Tires." It shocked him back into vivid consciousness. He remained for an instant in the mental confusion of a man waked from a profound slumber. The chauffeur had drawn up to the curb and now opened the door in some alarm to find out what was the trouble.

Crawley descended to the street in a daze and paid the driver of the machine. In his confusion he hardly knew why he left the car. It was because he felt a startling connection between that electric sign, "United States Tires," and the drunken man who was carried up the steps by his two friends. He shrugged his shoulders and when the taxicab started down the street he almost called out to it to stop and take him in again. He resisted the impulse. The chauffeur would have thought him mad.

He stood a moment on the street corner puzzling out the queer sense of horror which possessed him. He looked about and found the street very dark and seemingly narrow. Still he could not determine what cause there was for that depression. In some obscure way it was connected with the sign, "United States Tires," and the sight of the drunkard. It was one of those subconscious impulses which torture the brain. Something was required of him, something which must be done at once. What was it? He gripped his hands and set his teeth, but the acts only increased his nervousness and did not clear his mind.

He walked out in the middle of the street and scrutinized the big sign, flaming far away. That brought nothing to him. He closed his eyes and tried to visualize the picture of the drunkard being carried up the steps. The house was one of those common affairs with brown fronts, of which there were countless thousands in New York. There was nothing by which he could identify it. He remembered that as the three men reached the top of the steps the helpless man's foot struck against the stone and his whole body swayed back. He must have been totally unconscious.

Finally he knew what he must do, and that was to find the house if possible. The thought of going to it filled him with dread for what reason he could not tell, perhaps the limousine was still in front of the house. In that way he would be able to identify it. Yet, why should he be curious about the affairs of an intoxicated man?

He could not help it. He turned and started back down the street at a brisk pace. The street was empty of limousines or of any other machines. The houses with brown fronts were innumerable on either side. He went on, scanning each house as he passed in a vague hope that he might remember something when he saw the right one. In the distance flamed the sign, "United States Tires," blotted out wholly or partially by each building as he walked along.

He came to an abrupt stop; he felt his blood run coldly back to his heart.

Over this house all the distant sign was blotted out except the letters at the very end: IRES. Ires! That was the word which young Noyes had seen over the house of his dream. Yet this place was uninhabited. The windows were blank of shades or curtains. Across one glass was affixed a rental sign. Nevertheless he found himself involuntarily climbing up the steps. It was rather unearthly, but it also had an element of the ridiculous. He would not have believed such a freak of a hard-headed man like himself. With a smile he tried the door, and then started, for it gave way readily to his touch.

A dark, empty hall confronted him. He lighted a match and held it above his head. As far as he could see into the gloom the hall was barren of furniture and everywhere the floor was gray with dust. A thrill of nameless horror caught him with a great desire to turn about and run down the steps to the open streets. Under the emotion his hand trembled violently and the shaken light of the match filled the hall with turbulent seas of shadow. The sight of that touched him with shame and set his blood in circulation again. He closed the door with a slam, cleared his throat loudly as if to warn of his coming, and lighting another match, he started a progress through the rooms.

They were all empty on the first floor. Dust was everywhere. The boards creaked under his heavy step again and again, and each time he started and looked behind him. There were closets to be opened. It was very unpleasant. He found his forehead cold and damp. In the end, having gone through each room, he heaved a breath of relief. There was nothing there, and of course, he could now leave this place.

Yet, the sinister whisper of conscience called him back and drove him with hard-set jaw up the stairs to the second story. He threw the first door open with a jerk and stood tense, with his fist tight, ready to strike. The room was empty, and the pallid moonlight slipped along the floor. The sight restored more courage to Crawley. His tremors reminded him unpleasantly of the way in which Vincent Noyes had thrown open the door of his closet as if he expected an animated skeleton to fall out against him.

He was smiling at this thought when he threw open the door of the second room. The smile froze on his lips into a meaningless grin. There sat Noyes beside the window with the moon full upon his white face. He was grinning back at Crawley in a ghastly manner and his eyes looked directly into the big man's face.

"Look here!" broke out Crawley. "Don't be a damned ass, Noyes. You gave me no end of a start. What's your idea in coming to a deserted house like this? What do you—"

He stopped. It was hard to talk in the face of that unchanging grimace. Noyes must have a queer sense of humor. He approached the man and dropped a hand on his shoulder. Even through the clothes he was aware of the stiff coldness of lifeless flesh.

Crawley jumped back. Still the eyes stared at him, but it was the filmed glance of one who has looked on death, and the grin was the mirth of one who smiles at the end of the world. All his courage deserted him. It seemed as if the corners of the room were filled with invisible but watching presences. He ran out into the hall, and then down the stairs. The moment he started to flee, wild terror possessed him. The stairs seemed infinitely long. When he reached the door of the house he was ready to yell for help.

OUTSIDE, the fresh air gave him new life, but it could not wipe from his

memory that gaping smile, that idiotic and horrible grimace. When he rushed

into the police-station ten minutes later, men jumped up and stared at him,

for the image of death still looked from his face. It was not until he had

given his story to the sergeant in charge that his self-possession in a

measure returned. Even then he had not the courage to go with them to the

house. He described it by locating the street and naming the house which had

over its front the four fatal letters:

IRES.

IN half an hour the sergeant returned. The body had been taken to the morgue.

The doctor stated that he believed death to be caused by shock. There was no

sign of a wound in any part of Noyes' person. The police lieutenant now

appeared and made Crawley rehearse the details of his story over and over

again.

Crawley began with the fact that Noyes was a fellow lodger at his address. From that point he went on to describe the three men whom he had seen walk up the front steps of the house. Here, he had to lie. He had to say that the face of Noyes was visible to him in profile and that at first he wondered why he should be in such a part of the city in such a condition. They would never have believed the queer process by which he came to stop his taxicab and go back down the street inspired by an electric sign!

The rest of Noyes' story, as far as he knew it, he left untouched, for he was beginning to understand why the London police had laughed at the tale. As far as he told the tale of the discovery, the police believed him absolutely without suspicion that he might have a hand in the murder—if it were a murder. His sincerity was pointed by the still horror which lingered behind his eyes. At last they let him return home.

He went immediately to Noyes' room. It was, of course, empty, save for the cat. Abdallah came and fawned upon him, and when he left the room, after noting that there was no sign of disorder or a struggle there, the big cat followed him downstairs. When he sat down in his chair the Persian sat down on the floor in front of him and watched him with steady yellow-green eyes. He could not refrain from returning the stare.

"What is it, Abdallah?" he said at last. "Are you going to be happy staying with me?"

The cat rose and rubbed against his leg.

"That means yes, eh? All right, old fellow. Tell me when I can do anything to make you comfortable."

Abdallah rose and commenced to walk up and down the room, pausing to turn his head now and then and stare at Crawley.

"What's the main idea?" asked the man. "Do you want me to get busy—get on the job? What job? Find the men who did away with your old master?"

The cat meowed plaintively, and Crawley started in his chair.

"My God!" he muttered. "There I am talking to a cat—talking to myself! In six months I'll be in the condition of poor Noyes! No, Noyes was only a nervous boy, and I'm—" He arose and stood before his mirror. A scowling face looked back at him, a lean, weather-hardened face, with a square-cut fighting jaw. The sight comforted him. At least it would be a fight, and if they did not fight hard enough he would land them in the end. The resolution calmed him, and when he went to bed he fell into a deep and dreamless sleep.

The jangle of the telephone roused him the next morning. It was the police, who wanted him that day for testimony before the coroner's jury. He faced the prospect without a qualm. Even when he rehearsed the story he must tell, he felt no thrill. After breakfast he came back to his room for a quiet half hour to think over the case and for the hundredth time muster one by one all the facts as he knew them or as Noyes had told them. The scratching of Abdallah at the door interrupted his musing. A light footfall was going up the stairs. Perhaps it was the police, come so tardily to examine Noyes' room. Abdallah mewed softly, eagerly. He opened the door and looked up the stairs. Someone was in the very act of entering Noyes' room above.

Abdallah whisked into the hall and up the stairs. Crawley followed at a stealthy pace, but before he was half-way up the stairs, the low cry of a woman started him to a run. He flung the door open and saw within the room a woman kneeling, with big Abdallah in her arms, covering the cat with a thousand caresses. She turned her head with a little start toward Crawley, and he found himself looking into the face of Ires, or whatever her name was, whose picture Noyes had accidentally allowed him to see—the sight of whose face had so mortally terrified the man from India. Moved by the stern silence of Crawley, the girl dropped the cat and rose to her feet. In reply he closed the door behind him and set his broad shoulders against it.

"So, my dear," he said, "you've walked right into my hands."

The dark eyes widened a little, but otherwise there was no sign of shock or fear.

"And may I ask who you are?" she said.

"You may," he answered. "I'm Jim Crawley, and I'm a friend of the dead man."

"Dead!" she repeated with a heavy inflection.

"My dear Lady Mystery," he said, "large eyes won't serve you now!"

If it were acting it was very well done. She stared at him in that stupid manner of one who hears a disaster too great for comprehension. That white-faced horror called back a vivid image of poor Vincent Noyes—how he had frozen with terror when he saw the picture of this girl.

"Come, come!" he said, frowning to call up his tardy anger. "Now that this damnable business is consummated, do you think to make me blind and shuffle your way out of it?"

"Dead?" she said again.

"Aye, dead, dead, dead! Vincent Noyes is dead and you'll suffer for your part in it or—"

She caught a hand up before her face and swayed. Crawley laughed.

"Sit down in that chair and talk reasonably," he said. "Maybe you'll find it easier to talk with me than to the police."

She sank into the chair immediately behind her, sank heavily and lay there with her head fallen back as if all the strength had slipped from her. Crawley walked to her, dropped a hand on her wrist, and feeling the faint flutter of the pulse, he jerked open a window and stood over her with folded arms, waiting for the cold air to bring her back to life. Her lips stirred before her eyes opened: "Vincent!"

He leaned close to her. Before her senses returned she might murmur some confession which would damn her in the eyes of the law.

"Yes," he whispered. "Yes—dear!"

"I—have prayed—prayed for you—but I was helpless—against them!"

Her eyes opened. She sat up with a moan and caught his hand in both of hers.

"You didn't mean it!" she pleaded. "They haven't hunted him down at last!"

Crawley stood back with a scowl. He wanted to believe this merely clever acting, but grief has a way of its own. Her eyes wandered.

"It is better that it is done," she said. "He is at rest at last, and I—"

She ran to Crawley and closed her hands on his coat.

"Were you his friend?"

"Yes," he answered, deeply troubled.

"Then you will be my friend, too. You will not let them take me back."

She caught his hand and placed her slender white one inside it.

"You are strong! See, how strong you are and how weak I am! Keep them away from me; I am afraid; I am afraid! No, no! Such strength as yours cannot help me!"

SHE broke into convulsive sobbing, a childish wail in her voice, and a tremor passed through Crawley. For an instant longer he fought against the surging pity which beat like waves against his colder judgment, then he gave way. The sense of her delicate femininity was stronger than a man's hand to disarm his suspicions. With one arm about her, he led her back to the chair and as she sat down again he kneeled close to her and caught a faint odor of violets, an ethereal fragrance which added a touch of poignant melancholy to his compassion.

"What is this trouble?" he asked earnestly. "Who are 'they'?"

She shuddered and shook her head.

"How can you expect me to help if you will not tell me?"

"I don't expect you to help me—now."

"They are too strong?" he suggested.

Her eyes wandered past him again with that singular expression of waiting which he had noticed in Vincent Noyes' face many a time.

"Yes, they are too strong." She rose with a start. "I must go back."

"To them?"

She hesitated, as if deciding whether or not she could risk confiding in him so great a secret.

"Yes, to them."

"By God!" said Crawley with a sudden outpouring of rage. "You shall not go—or if you do, I'll go with you!"

She smiled sadly on him.

"You must not," she said. "I know you are strong. I guess you are brave. But bravery and strength are useless against them. You would throw yourself away, and in a way so terrible that if you were only to guess at it now, your face would grow as pale—as mine!"

The feeling of impotence maddened him.

"Here's a lot of fol-de-rol and nonsense," he said, "and if you give a real man a chance to work for you, you'll find these devils, whoever they are, will fade away into a puff of mist—a little sulfurous, maybe. Will you give me the chance?"

She opened her purse to take out a handkerchief and a tiny square of colored cardboard fluttered to the floor.

"I dare not tell you more about it," she said. "I have already talked too much. I must go."

In a daze he watched her go to the door and then turn, holding out her hand in farewell. Suddenly he realized that he must not let her go. It grew vastly important that she stay with him if only for two minutes longer. He took her hand and did not relinquish it for a moment.

"Tell me only this," he said, keeping his voice gentle. "Why did Vincent Noyes, if he was dear to you, fear you like—"

"Like death," she said, without a tremor in her voice, though she was very pale. "He feared me so because—because I meant that to him, and I—"

"Hush, hush!" he broke in. "If it tortures you so, you shall not speak of it. I shall find some way to search out the heart of this horrible affair, but I shall not suspect you—"

"My name is Beatrice," she said.

"Only Beatrice?"

"I dare not tell you more of it."

"I shall not suspect you, Beatrice. I only ask you to give me one clue—say one word—which will help me to find them. Will you say it?"

"Don't you see?" she cried with a sudden passion which transfigured her in spite of her sorrow. "It is for your sake that I refuse to let you know. If you were not his friend"—and here she made a sweeping gesture about the room as if the presence of the dead man were still palpable there—"if you were not his friend, I should tell you everything and pray for your success; but I cannot see you thrown away."

She lowered her voice to a sad solemnity which checked his protest.

"You cannot help me, any more than you could help him. You would be lost as he was lost, in trying to save me. Good-by."

He followed her hastily through the door, but she turned to him gravely.

"You will not follow me? I do not wish it!"

He stared at her an instant, then bowed and returned to Noyes' room. For some time he stood with his back against the door, his hands clenched. Something had changed in him, though he scarcely knew what. He felt like one awakened from a vivid dream, or rather like a cynic who has seen base metal transmuted into gold.

Finally the glamour wore away a little and he remembered with a start that he had allowed this girl to leave him without obtaining the least clue from her of either her address or her name. The idea made him flush with shame. Perhaps she was even then laughing at him. If it were acting, he finally decided, she had deserved to escape.

He began to pace up and down the room, thinking first of Vincent Noyes, then of the girl, Beatrice, and lastly, strange to say, of himself. For he began to feel alone, bitterly alone. He felt like one who sits in a drearily familiar room and hears voices below, vague voices of many people, and he cannot tell whether they speak in anger or in happiness; but he wishes to be among them, for they seem to be living, and he seems to have no share in the world.

So it was with Jim Crawley. Tragedy had passed him in the form of Vincent Noyes; romance had looked on him from the eyes of Beatrice; and now that they were both gone, he wished to be in the heart of the mystery more than ever, for that seemed the one reality in the world. He paused in his walking and raised from the floor the little square of thin cardboard which she had dropped from her purse. It was the seat-check of an opera-ticket.

Only this flimsy thing remained to connect him with the girl. This was all he had through which to trace her. Abdallah rubbed against his leg, meowing loudly. He glanced down with a muttered curse, and then hurried to his own room, where he sat down and buried his face in his hands to ponder over all the details of the strange case.

THE more he thought the more he regretted having allowed the girl to go

without forcing her to tell him frankly all that she knew. Nevertheless, if

what she said was the truth, he had advanced somewhat. Noyes had feared the

girl and she admitted that he feared her with deep reason. How she could

unwillingly be a danger to the man from India, he could not dream.

Nevertheless, this was her statement.

Furthermore, the same power which killed Noyes now threatened her. If it did not threaten her, at least it controlled her in the most sinister manner, kept a seal upon her lips, bounded her actions, and kept her under such an omnipotent dread that she dared not even appeal for aid.

If such a thing had happened five centuries before, he might have attributed it to religious superstition which forced people to do strange and terrible things in the name of a creed.

If he could not find religion here, at least there was something more than earthly in that which had threatened Noyes from afar and wasted him to a shadow with the constant dread of death. It was on the girl in a scarcely less perceptible degree. It was like an unseen hand which dragged her away from him at the moment she was on the verge of telling him something which he could use as a clue.

He defined this thing then as a criminal force operated by men or women or by both; but probably by a great many, since they were so ever present.

But this supposition was far from satisfactory. There was big Abdallah, whose brute soul had sensed the danger before its coming.

In spite of himself Crawley was forced back on the belief that there were something more than earthly in the affair—some terrible control of mind over mind—a spiritual tyranny which was greater than the force of body, which could even extend its authority to the mute beasts.

He crossed to the window and jerked it up, for his cynical, practical mind revolted against this sense of mystery. With a great relief he felt the fresh air. He glanced down to the little slip of cardboard which he still held. That at least was tangible reality. It occurred to him that the little torn seat-check might be the means of bridging the gap between himself and this affair of the other world, for as such he could not help considering it.

Certainly, to make any progress, he must see the girl again, and this clue might lead him to her. If she had gone once to the opera she might go again, particularly since this sorrow had come to her and any diversion might be welcome. She might even sit in the same seat.

The opera bored Crawley, with its impossible attempt to combine the artistic elements of decoration, music and drama. Moreover, it strained his pocketbook; so he seldom went. Nevertheless, he decided to attend the next three performances and for that purpose resurrected an old pair of field-glasses from his baggage. Twice he sat in his seat straining his eyes or turning his glasses in all directions, but without seeing a face which, in the slightest degree, resembled Beatrice.

The third occasion, as in the fairy-tale, brought him better fortune.

She sat in a box in the grand tier to the right of the house. Immediately after the first act he spied her in a black gown, and his glasses showed a notable string of pearls around her throat. The dress changed her greatly, but he could not be mistaken in her face. What made his heart fall was the gaiety with which she conversed with a thin-faced man beside her, a fellow in early middle age. Crawley could see nothing but her profile, for she was continually turning her head and laughing with her friend. If she had truly been struck with sorrow for the death of Vincent Noyes, nothing could recall her to such good cheer.

Shame for his gullibility made his face hot and he bit his lip. In the anger which immediately followed he vowed silently and devoutly never to leave the trail of the mystery until he had brought down justice on the criminals.

Toward the end of the intermission her companion left the box, and the third person in the box came from the rear. He was a tall, leonine figure with a rather square cut, tawny beard. Crawley trained the glasses on him with sudden interest. It seemed to him that he had never seen a man who suggested more indomitable strength. Even through the beard he guessed at the powerful set of the jaw. The hand which rested on the back of Beatrice's chair as he leaned over was white and massive. Such a hand in the stormy middle ages would have chosen for a weapon the shattering mace, rather than the trenchant sword.

She looked up to him as he bowed, and what a change came over her face! Her smile grew fixed, her eyes widened, and she altered as if powder were sifted over her skin. It was not the expression of a moment. It lingered while he stayed there smiling, speaking apparently very slowly and without emphasis. He withdrew to the rear of the box and almost immediately the slender man entered and took his former place at the side and slightly to the rear of Beatrice.

As the lights grew dim, Crawley saw that she was laughing once more, but now his heart beat more easily, for he guessed at some compulsion behind that mirth.

During the second act he heard nothing of what passed on the stage, for he was laboring to decipher the meaning of the three figures in that box. He came to a conclusion that the leonine figure had some connection with that power which controlled Beatrice and which had struck down Vincent Noyes. Otherwise there was no explanation of the change which came over her when he stood behind her chair. As for the slender man, perhaps he was a stranger or a chance acquaintance. Perhaps he was the renter of the box and had invited Beatrice and the big man. At least it seemed that for some purpose of him of the tawny beard she was forced to be pleasant to the other man.

This conclusion solved no mystery, decided nothing. But the very hope that he had seen one of those who represented "they" set the blood tingling in Crawley's veins.

His field-glasses never moved during the next intermission, and when he saw the tall man rise, murmur a word to Beatrice and the other, and then leave the box, Crawley rose from his feet with a thundering heart. He had located the box carefully before starting; in the corridor of the grand tier he located it without difficulty and entered. She was leaning very close to the slender man, and just as Crawley entered, they broke into laughter. He waited a moment to enjoy the music of her voice.

PARDON me," he said, and advanced upon them smiling.

The laughter died suddenly from her face as she turned to him, hesitated, and then: "Mr. Helder, this is Mr. Crawley."

"You remember that secret?" said Crawley, his head turned toward Beatrice as he shook hands with Helder.

"Of course I do," she said calmly, and he blessed her inwardly for her poise.

"Well, I have a clue!"

"Really?"

"In fact, I can show you the very man!" He turned to Helder gaily. "If you will excuse us a single moment."

"Surely," nodded the other, his eyes brightening in sympathy with the mysterious jest.

Beatrice shook her head and a slight frown warned him.

"Are you positive?" she said reluctantly.

"You will be astonished when you see—and hear," he said confidently.

"Very well." She rose.

Crawley picked up her coat.

"Quite a draft in the corridor," he suggested. "Don't know where it comes from, but perhaps you'd better take this."

He read in swift succession her surprise, doubt, worry, and finally acceptance. At the entrance she turned a little.

"In a moment, Mr. Helder." And then she was with Crawley in the bustling corridor where men and women hurried up and down and the air was filled with a dozen faint and ensnaring perfumes.

"Now tell me quickly," she said, "What madness has brought you here? How were you able to follow me?"

"I haven't time to answer either question," he said calmly, taking her arm.

"Where are we going?"

"Down to the street."

"The street?" She stopped abruptly.

"Please don't do that. People will be noticing us in a moment. That fleshy gentleman is staring already."

"Mr. Crawley, you are only embarrassing us both."

"Beatrice—" She started a little. "It is the only name by which I know you."

She stopped again determinedly.

"We must go back to the box instantly. Leave me and I shall go back alone."

"Have you no trust in me?"

"I tell you I have no trust in anyone. All I know—all you must know—is that I dare not be seen with you. Mr. Crawley, I swear I am thinking of your own welfare!"

There was a thrilling seriousness in her tone. She took his hand in both of hers.

"To please me—for my sake—go now—at once—forget me forever. For my sake and for your own!"

"Do you think I have come to you on some trifling matter?"

"No, no, no! It is because of a—of a man's death. You still hope—"

"It is because of no dead man," and then seeing her lips part in her wonder: "I have come for the welfare of a man who is alive—very much alive."

"Who can it be?"

"Can you think of no one?"

She caught her hands together and in her murmur there was a despair which stirred Crawley more than if she cried aloud: "Yes, yes. Oh, why was I ever born!"

"If you will come with me I will bring you face to face with him within five minutes."

"I dare not go! Who is it?"

"You will know him well enough when he speaks to you."

"No. You see that I cannot! I am watched. I shall be missed—and if I am suspected of having—"

"There is nothing in this man for you to fear. He merely wishes to speak with you for five or ten seconds—merely to see you. He would trade all his hopes of happiness for that."

Her eyes, pitifully misted, dwelt on his.

"Does he care so much? And I—may I trust you? Will you give me your word to bring me back?"

"I will take you wherever you wish after you have heard this man. We could be back by the time that the third act commences."

"Mr. Crawley—"

"We waste time—and all your moments are precious, you say."

"Yes, for he might come back sooner than he said, and—let us go, quick! quick!"

He hurried her down the stairs, stopped for his hat and coat, joined her again, and led her to the street. As the taxi-driver opened the door of his cab, she hesitated again and her hand closed nervously on his arm.

"It is not far?" she said, half pleading.

"In five minutes," he murmured, and then in a low voice to the driver: "Go straight ahead; turn in a few blocks; keep traveling in a circle and never get more than five blocks away from the opera-house until I tell you where to go."

When he took his seat and the machine started, she huddled far away against the side of the car, staring straight before her. He watched her for a moment in silence, until she turned impulsively toward him.

"I have never done so wild and thoughtless a thing," she said. "Pardon me. I do trust you, Mr. Crawley; but some force in you seemed to make me come whether I would or no."

He answered nothing, but sat with his head bowed, thinking desperately, but making no progress in his thoughts. Her coat slipped away a little from her shoulders and as they passed a street-lamp the light gleamed on the white skin.

"It is almost five minutes," she said anxiously. "Are we almost there?"

"We are there," he answered. "It is a cheap subterfuge, but I had to see you alone."

All of her face was in shadow, but her eyes grew strangely luminous.

"Mr. Crawley!"

He said gently. "There is no danger. I have told the driver to keep within five blocks of the opera-house. He will travel in a circle and when I give the word he will take you straight back."

"Then start him back at once!"

"I will if you wish, but you promised to hear this man speak."

"But you said—"

"That ten seconds of speech with you meant the world to me, and I did not lie. I could not talk in the opera-house. I knew you would not listen while that tawny-haired man was near you. Tell me, is he one of 'they'—one of those forces which control you?"

She was silent.

"You need not speak."

"I WILL speak," she said at last. "Yes, he is one of them, but he is the least. You saw him. You can judge if he is a trifling man to cross in even the smallest thing—but he is the least of them. That is your warning! See, I read your mind, in part, and I know that you are planning how you can tear me away from that power which you vaguely guess at! If you had the slightest knowledge of it, you would flee from me as if from the worst plague and you would cross continents to place a distance between yourself and me."

"Nevertheless, I shall not leave you."

"You shall not?"

"If you insist on going back to the opera-house I will go with you. I will take that leonine fellow aside and tell him my suspicions to his face."

"No, no! That would be utter ruin."

A hush fell on them as they stared at each other through the cessation of a sound, but like a light that is blown out.

"Why have you followed me?" she asked at last, and the strength was slipping from her voice.

"I couldn't stay away. I tried."

The light at a crossing flared into the car and showed his face set in stern lines. She shrank and whispered as though someone might overhear, "I am afraid!"

"If there were no one waiting for your return in the opera-house, would you be afraid?"

"I don't know. I dare not think."

"Have they a right on you?"

She shook her head.

"But I have a claim—the claim of love."

She raised her arm as if to ward him off.

"You look as if you hate me," she murmured, but he saw belief go flushing up her throat and shine in her eyes.

"You do believe?" he said. "If you will trust me I can fight for you against the devils in legion."

"I try to understand."

"Is it hard to do?"

"It is like music, is it not?" she whispered.

He said, "For three days I have been alone, even in crowds I have been alone. And now perhaps I have only this moment to see you, but I am as happy as if eternity were in a second."

Her eyes looked past him.

"Beatrice, do you care at all? Have I the ghost of a chance?"

He could not tell whether it was only a drawn breath or a whispered "Yes." And still her eyes dreamed.

"Beatrice!"

"Yes?"

"Do you think you could learn to care for me?"

"I dare not think!"

"Answer me!"

"I think—perhaps!"

"You care already?" He leaned still closer, and suddenly she clung to him, and in a broken voice: "I do care. Oh, I do care. It is mad and rash and cruel to you, but this moment is mine and yours, and they have all my life!"

A sob stopped her, and his heart rose into his throat and made him dumb. She spoke.

"They are strong, but their power is that of devils—and yours is the strength of a man. I am not shamed. I am too starved for happiness—and you can give it to me. Oh, my dear, your voice to me is like sunshine in a room that has been dark for ages—come closer—see, something unfolds in my heart like the petals of a flower touched by the light. Take me, and hold me, and kiss me."

AND after that, time stopped. The street-lights shone over pavements newly

wet with rain and pointed a thousand diamond lances at them as they whirled

past. They saw nothing. The traffic reared about them, thousands of voices,

bursts of laughter, chatter of words, the whir of starting automobiles, the

sudden screaming of horns—they heard nothing.

But Time claims its own, however far they may wander. It found Beatrice, and with its cold touch froze her smile.

"It is late!" she cried. "It is hours and hours late! Turn back for the opera-house—quickly, Jim!"

Her accent, lingering over that new-learned word, made him catch his breath.

"Do you dream that I will let you go back to them?"

"You gave me your word!" she pleaded. "You gave me your word to turn back when I asked. It's for your sake, Jim!"

"Will you hold me to my promise?"

"I must!"

He groaned, but leaning forward gave the order to the driver.

"YOU know that I am not thinking of I myself?" she asked tremulously.

"But how can I help you, Beatrice, if you will not give me a chance to fight against them?"

"Jim, Jim, you must never fight against them. Promise me!"

"Do you think they can cow me as they frighten a timid girl?"

"Dear, even strong men are afraid of devils and have no shame of their fear."

"What are they? What is their power? I shall go mad unless I know."

"Jim, as long as you don't know what that power is, you will have a chance of happiness, but if you know—"

"What then?"

"The thing which haunted Vincent Noyes to his grave was his knowledge of that power."

Crawley shuddered. He would never forget the dull-eyed despair of the man from India—that nerveless grip on life—that deep and hopeless foreboding of death.

"Promise me you will never ask me again, Jim?"

"I shall wait until you come to me of your own will."

"We are almost there. You will find a way to come to me again?"

"In spite of hell," he answered quite fervently.

As the machine turned the last corner, she cried out in fear. He looked out the window of the car and saw the street black with people and full of automobiles starting away from the entrance of the opera-house.

He could feel her trembling as she shrank against him for protection.

"Look!" she moaned and pointed a wavering arm.

He saw the tawny-haired man, a head above the crowd, standing near the door of a waiting automobile and scanning the pavement up and down with a last searching glance. Then he stepped into the machine which instantly moved off.

"Shall we follow him?" asked Crawley.

"I am afraid. If he knows I have been with you, he will—"

"How will he find that out?"

"His devil will whisper it in his ear—describe your face—even give him your name."

The cold sweat was on Crawley's forehead.

"What fiend could tell him that?"

"The fiend is I!"

He caught her by the arms and made her face him.

"Beatrice, what madness is making you rave?"

"Jim, dear Jim, it is the horrible truth. I could not keep it from him."

"Why?"

"You have promised not to ask."

He ground his teeth.

"You shall not go back to him," he said firmly.

"If I fled a thousand miles from him he would bring me back. Take me to his house. It will be terrible to face him, but easier now than later."

Crawley leaned forward and spoke to the taxicab driver.

"That is not the address!" exclaimed Beatrice.

"It is the place to which we are going."

"What is it?"

"My lodgings."

"Jim!"

"I gave you my word to bring you back to the opera-house when you wished," he said, "and I did it. Now you are going to do what I say."

"No; no! no! Don't you understand? Jim, think of Vincent Noyes! Let me go from the machine or I shall cry out!"

"If you try to, I'll stifle you with my hand. I mean it."

"Dear—"

"I won't listen."

"It means death."

"Perhaps. In the meantime there's only one thing that I fully understand about this whole affair, which is that the longer you stay with 'they' the more hopelessly you fall into the toils. The time's come to break away. If I can't see my way against them, then I'll simply fight blindingly."

"Jim, it's for your sake that I wish to—"

Her voice trailed away. He sensed rather than saw her settle back against the cushions. Her hand found his and relaxed there.

"I'm tired—deadly tired, Jim," she whispered.

The taxicab drew up in front of his lodging. He paid the driver and then helped Beatrice up the dingy stairs to his room, where Abdallah forgot his dignity to welcome her. Beatrice held the big Persian in her lap. They both seemed to watch Crawley with a half-sleepy and a half-expectant interest.

"And now?" she asked.

"It's very late," said Crawley, "so we'll stay here tonight. Early tomorrow morning we start for the country. I know a place up in the Connecticut hills. It will be very beautiful at this time of year—the old inn—we shall go there."

She closed her eyes, smiling faintly.

"It is so pleasant," she murmured, "to do without fear what another commands. I have been armed with suspicion, and now I can lay my armor aside. I feel—like a cat beside a warm hearth, Jim!"

Her low laughter died away suddenly. She started erect in the chair.

"Jim! How can I go gadding about the country like this with you—and here in your room tonight—"

She started to rise, but his gesture stopped her.

"It's all right, my dear," he said calmly, "you needn't worry about that."

She regarded him with a puzzled frown, as if she strove to believe him but found it a hard task.

Her lips framed a word but made no sound. Crawley crouched in front of her and gathered her hands into his.

"If I am to fight for you I must have a legal right to do so," he explained.

The wide frightened eyes made him wince.

"You will trust me even in that, Beatrice?"

She sighed. It was as if all her cares went from her in that breath.

"You have said you love me, Jim?"

"God knows I do, dear!"

"Then if I love you it must be right, mustn't it? I am so tired, all at once, that I can't think."

He was very grave and his jaw set to a grim fighting line.

"I shall make it right. I'll ask nothing of you now except to fight for you. If I win, then in time, perhaps we will be truly man and wife."

SHE smiled, a dim obsolete smile like that of an ancient woman encouraging

the rash optimism of a child. A new, choking emotion made him turn sharply

away and begin pacing the room. She watched him in absolute silence. Finally,

he glanced and saw that she slept with the same faint, sad smile as if

depreciating her happiness. Very vaguely he guessed at the utter weariness of

soul which allowed her to sleep at such a time.

He raised her gently in his arms. She did not waken. Her breath came regularly, softly, against his cheek. He laid her on the bed. She sighed and her lips moved. Crawley leaned over until he could hear the word. Once, twice it was repeated. He straightened up suddenly, his eyes deep with awe. After that he pulled a cover over her, watched her pale beauty for a moment, and then went to the open window.

Outside was the holy night. Looking up between two lofty, stern walls, he could see the sky and guess that it was blue. The red flare of the city dimmed the stars, but slowly he grew aware of them. He had forgotten that they shone over New York.

They called him back to the sacred moments of his life, to his boyhood, to all things of reverence which had gone into his nature. There was something very like to a silent singing in the heart of Crawley, and behind his lips a vow like that of the crusaders.

Here a low moan from the sleeper made him turn suddenly. Her face was flushed. She was frowning. One arm was thrown above her head and the hand was clenched. Evidently she was dreaming unpleasantly, and whatever that nightmare was it seemed to have a meaning for Abdallah. Even as Crawley turned, the big Persian uncurled himself on the chair where he slept and crouched with rising hair and switching tail, suddenly roused to a fighting watchfulness. Something of what Noyes had said of the cat came back to Crawley and made a coldness around his heart.

Abdallah leaped from the chair and padded swiftly to the door where he sniffed at the crack along the floor. Instantly, however, he turned, and with bristling hair and eyes like yellow points of hell-fire, he ran back and leaped upon the bed.

Beatrice still stirred in her sleep; her hand remained clenched; her lips moved. Abdallah stole from her feet toward her head with the manner of a wild animal stalking a prey. Then he crouched, his tail still switching angrily from side to side, and fixed his blazing eyes upon the face of the sleeper. The unearthliness of it turned Crawley's soul to water. He had seen the cat fawn about Beatrice only a few moments before. Evidently she had known the cat of old, but now Abdallah acted toward her with all the singular mixture of hatred and fear which Crawley had observed in him on that night when he had said good-by to ill-fated Vincent Noyes.

He crossed the room hurriedly and leaned over Beatrice. She still struggled in her nightmare and from her whisper he gathered only the word: "No, no, no!" repeated over and over again. She was fighting against something in her sleep, fighting bitterly. Under the faint light her forehead gleamed with moisture, and at the sight of her mute suffering a tremendous wave of pity and tenderness swept over Crawley.

Instantly there was a change! Her whispering ceased. The flush died down. Something in her face went out like a snuffed candle. A weary smile touched her lips. Her hand moved until it encountered Crawley's by chance and closed about it. The soft touch thrilled the big man. Her smile died; slowly her fingers relaxed; she was sunk again in a profound and dreamless sleep.

Crawley straightened up, feeling as if he had performed some wearisome physical labor. Abdallah was curling himself up at Beatrice's shoulder and purring loudly. Crawley crossed to a chair and sank into it, his face buried in his hands.

No matter what the odds, if it had been an affair in which he could use his physical strength he would have wagered on success in the end, but against the sinister power which reckoned nothing of space or time and which crept into the sleep of its victims he felt utterly helpless. Between that power and the sleeping woman he loved, he was the only barrier. How slight for all his experience and all his strength! He walked in the night while a thousand hands reached out after her, invisible, deadly hands. Crawley interlaced his powerful fingers behind his head and groaned in an agony of impotence.

The gray dawn came at last, and in the opposite mirror his face showed lined and set like that of a sick man. Once more, with a falling heart, he thought of Vincent Noyes.

SHE woke at last into another personality. It seemed as if her sleep had brushed from her mind all the thoughts of the preceding day. In the face of this fresh, radiant beauty he found it impossible to mention his plans until she came to him and dropped her hands on his shoulders.

"And now?" she asked.

"And now?" he repeated dully.

"Don't we go to the country today?"

"I—" he began, and found it impossible to go on.

"Have you changed your mind, Jim?" And her voice went low with anxiety. "No, no!"

With a great effort he managed to meet her eyes. It seemed to him that he could look an unfathomable distance into their clear depths.

"We have three things to do," he said mechanically. "First, to buy you some clothes—you can't go in an evening gown, you know; then to get two tickets for the country, and last, to be married... Beatrice, am I right to let you sacrifice yourself because of your need to a man you do not know, and—"

"Oh, my dear!" she cried, and her voice, with a hint of both tears and laughter, sent a thrill of tenderness through Crawley. "I have known you always; I've been waiting for you all my life!"

Yet when they left his room she seemed aloof again, for there is a native strangeness in all things of beauty. All day she was humming and singing softly, and there was almost a dancing cadence in her step. And how full of changes!

She was like a butterfly, dressed in clinging filmy stuffs, when he left her at a Fifth Avenue shop and went out to get the ring and the license. When he returned he found his butterfly transformed by a walking-suit into an almost Puritan drab, saved only by a soft touch of color at the throat.

THE wedding was an affair of the other world, even though it took place in

the City Hall. Some one droned words before them to which they returned

answers. He was told to put a ring upon her finger, and then they were man

and wife. It meant nothing. Her forehead was cold when he touched it with his

lips. Even at the last moment, when they entered the Grand Central Station

with Abdallah in a basket, he expected her to break suddenly into mocking

laughter and leave him there with a heart filled only by a dream. Not until

they sat in the train, not until the train itself had started, could he look

on her and feel that she was really his.

They got off at New Haven and hired an automobile to drive out to Willowdale Tavern. It was really more of a private dwelling than a hostelry. An atmosphere of domestic privacy could never be quite divorced from the old colonial house even by modern commercialism. It lingered about the old prints on the walls. It faced one in the dignity of the white columns of the porch. It creaked in the antique furniture.

Their rooms occupied a corner of the second floor. They were spacious apartments, eternally cool, and eternally peaceful. Abdallah signified his approval by curling up to sleep in the spot of sunlight on the flowered carpet. There was only one touch of modernity or art, and that was a bronze statuette of a satyr. This stood upon the mantelpiece, a roomy shelf, which, by the size of the fireplace, was forced up some six feet from the floor. All the rest of the room was softly old-fashioned. And as a final touch to complete the spell, against the window brushed the limb of a great maple-tree, bright with small new leaves.

Its movement seemed to beckon them out into the spring evening, and Beatrice could not remain inside. So they took a generously winding road fenced with thin-topped poplars on either side, so that as they looked up they found the sky always patterned in a different manner by the delicate tracery of the branches. She was infinitely gay and interested in all that she saw.

The New England landscape was a new world to her and he was kept busy telling the names of birds and trees and flowers. And then he had to talk about the country, as far as they could see it. It was a favorite place with him on week-ends, and he knew all the lore—what old colonial families had lived on such and such a place—and where the early settlers had built a blockhouse for security against the Indians, and how they held it, too, on more than one occasion against great odds.