RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

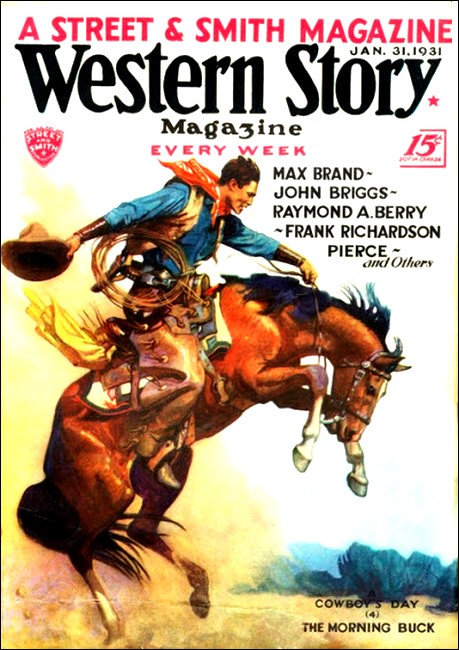

Western Story Magazine, January 31, 1931,

with "Chip Traps a Sheriff"

EVERY man has a special country that is fitted into his heart so snugly that it fills every corner. I know fellows who talk pretty nearly with tears in their eyes of the seashore, and the white curving of the surf, and the boom and the step of it; but they never can outtalk the lads from the high mountains, where the head and shoulders of things is lifted up so high that it almost breaks loose.

Then I’ve heard the real Kentuckian mention blue grass and big hills that never stop rolling from one edge of the sky to the other; yes, I’ve heard ’em mention blue grass, and horses, too.

Up there in New England things are smaller and put together more closely, but summer mugginess and flies and winter chilblains and wind can’t stop the New Englander from talking. He’ll tell you about a second growth forest, and the smell of the moldering stumps in it, and the autumn colors slashed through it like paint flung off a brush; and he’ll talk of the brook where it runs, and the brook where it stands still and lets a couple of silver birches look down into it to see how much sky is there.

Then you’ll hear people even rave a lot about sagebrush, and the smell of the wind that comes off from it when it’s wet, but for me there’s only one land that I feel God made when He was working in real earnest. The other parts of the world—well, He just made ’em for practice, but finally He got really interested, and then He made Nevada.

Yes, I mean that. Maybe I’m not talking about the part you know, because a lot of people are loaded right down to the water line with wrong information about that State. There’s a sort of a general impression that there’s some silver mining and sage hens in it, but they’ve got to scratch their heads to remember anything else.

Well, there’s too much Nevada for the people who live there to talk about. There’s about a couple of square miles of space for every hombre in that country—yes, man, woman, and child. And when you realize that mostly everybody is raked together in a few towns and mining camps, you’ll see that it’s possible to bump right into a lot of open space out in that direction.

I’ve bumped into it, boys. I’ve ridden it from the Opal Mountains to Massacre Lakes, and from Goose Greek Range to Lake Tahoe, and wondered how there could be that much real, fresh, sweet cold water in the world. And I know the ranges that sink their claws into the hide of Nevada, like the Monitor and Pancake and Hot Creek and Toiyabe and Shoshone and Augusta. I know that whole State. I know the dry feel of it on the skin, and the red hurt of it in the eyes. And I love it. There’s salt in my throat when I think of Nevada, but I love it, and I hope that I’ll live there and die there, God bless it!

But now I’ve got to particularize a little. You may have sage flats in your mind, but that’s not the part of Nevada that I mean. No, sir; I mean the place where God really turned Himself loose and did His best. He didn’t waste any time picking and choosing. He just reached out with both hands, and He piled up all kinds of slates and limestones and quartzites and granites, and for color He piled in some volcanic rocks that are some of them as blue as the sky, and some of them as red as fire.

He worked with this stuff and threw it up into great ridges and He chopped out the valley with the edge of His palm. He made things ragged, and He made things grand. He didn’t want to dull the outlines He had drawn with forests and such things. He wanted no beard on the face that He’d made; He preferred it clean-shaven, so He reached over to the westward, and He ridged up the Sierra Nevadas. There’s quite a lot of people in the State of Oranges and Hot Air—California, I mean—that think that the Sierra Nevadas were built up for their own special satisfaction, a kind of a wall and a turning of the back on the rest of the world; but really the only reason that the Sierras are up so high is to catch all the rain winds out of the westerly and pick out the mists and the clouds so that only a pure, dry air can blow over Nevada. God didn’t want those Nevada mountains and valleys to rust in the rain.

Well, when He’d finished off the main outlines, He says to Himself that He might give a few finishing touches, so He paved the valleys with fine white sand, and He polished up the mountains so that they’d shine, night and day. And then He says to Himself that this is the finest spot on earth, and what will He put into it?

Well, He finally picked out the jack rabbit that was biggest and fastest, and it could clear a mountain in its stride; and then He hunted up some coyotes that could run the rabbits down; and after that He got the wisest beast in the world, a big frame and a loose hide, and an eye like a man’s eye, and He put the gray wolf into the picture and yellowed and grayed it a good deal to make it fit in with the landscape better. Here and there He let a four-footed streak of greased lightning step through those valleys on tiptoe, and those antelope are the fastest and the wisest of their silly, beautiful kind. On the ground He laid rattlesnakes to catch fools, such as you and I, and in the air He put the sage thrasher and the Texas nighthawk, and the mourning dove, and in every sky He hung one buzzard.

Now He wanted to get some people in there to see all this picture, but He didn’t want many. So He just sifted into the rocks of His mountains some gold and silver, here and there. It wasn’t much. It was a trace. Just enough to make your mouth water, and not hardly enough to swallow. But the prospectors got the wind of it, and they came ten thousand miles across the world to have a look. Mostly they turned back on the rim of the picture—it was too black and white for them, and all the white was fire. The thermometer was ranging a hundred and fifty degrees in the year, and some had their hearts burned out, and some had their feet frozen. But a few went on in.

They climbed up onto the shoulders of those mountains and thanked God for a piñon, now and then; even the greasewood, and the creosote bushes and the sage seemed like company out there. They found their leads, and they sank their shafts into hard ground and banged and hammered all day long. They got mighty little, and they knew, mostly, that there wasn’t much hope. But still they felt mighty contented.

Why?

Well, it might have been because of the mornings, before they started to work and let their eyes go sinking over the white valleys, or the mountains beginning to tremble and blush in the early light. Or it might have been because of the evenings, when they sat dead tired and smoked their pipes, and looked at the evening rising just like a blue smoke out of the bottom of the rifts.

That was what I was doing.

I was just sitting there in front of my claim and figuring out that I had used up my last can of tomatoes, and sort of cussing a little, quietly and comfortably, all to myself; but my brain didn’t hear what my lips were muttering, do you see, because I was too really busy taking gun shots down one ravine filled with that blue smoke, and then down another choked with fire. And the white of the valley floor was still pure and very little clouded, and away off on the vanishing edge of things I could see a slowly moving cloud.

It was a dust cloud. It was raised by wild horses. I had seen them that morning, looking through that glass-clear air. During the night they would pass me, but on the following morning I would be able to see them again, traveling on at their unfailing lope in a two-day run to the water holes of the Shoe Horn Valley, away beyond.

I remember thinking of the wild horses, that I’d like to be out on the back of one of them, the wildest stallion of the lot, and go flowing on with the dusty stream of their march, and stay with them forever, contented. I mean to say, I felt that I was only sitting still on the bank of the river, looking; but those horses were in the river, they were in the picture, they were a part of it.

While I was thinking these things over, a voice says behind me:

“Why, hello, old Joe!”

I just pulled myself a little closer together. I looked up, but I was afraid to look behind.

“I’ve got them!” I said to myself.

I mean, when you’re out all alone for too long a stretch, sometimes the brain wabbles a little, and you’ll find a prospector turn as batty as a sheep-herder. For surely that voice I heard could not have come from any human lips. That boy Chip was likely to be anywhere, but he simply couldn’t have materialized there at my back.

I laughed a little, with a quiver in my voice. “I’ve certainly got ’em!” said I aloud.

“Look around, Joe,” said the voice again.

So I turned around and looked, and by thunder, there was the freckled face and the fire-red hair of Chip, sure enough! My heart jumped at the sight of him.

Also, my heart fell!

“YOU little sawed-off son of salt,” I said to him. “Where did you drop from?”

He hooked his thumb over his shoulder to indicate the mountainside that leaned back into the sky.

“Aw, over that way,” said he.

We shook hands. He had the same hands that I remembered so well. They hadn’t changed a bit; there seemed to be the same dirt darkening them around the first joints, if you know what I mean. No, all of him was just the same. He had sixteen years of growth on him, and a hundred years of sense, and a thousand years of meanness. All mixed and rolled and stewed together. Nobody ever talked down to Chip. Not more than once, I mean. One try was usually enough.

“Sit down,” said I. “You just walked out here a few hunderd miles and found me, eh? No trouble to you. What did you do? Learn the buzzard language and ask the birds which way to go?”

He sat down on the ground, laid his back against a rock, and folded his arms under his head. He was facing partly away from me, so that he could look at the same picture which I was seeing.

“Make me a smoke, Joe, will you?” says he.

I was about to throw him the makings and tell him to roll his own, when I saw that he was dead tired. There were violet shadows thumbed out under his eyes. Besides, just the asking for a cigarette was enough to show that he was beat. He didn’t smoke them often.

So I rolled him tobacco and wheat straw, and stuck it in his mouth and lighted it for him; and he didn’t budge a hand, but just lay there with his eyes half closed and looked at the picture in front of us.

The poor kid was almost all in. I said nothing for a time. I simply watched him, do you see? He smoked that cigarette to a butt and jerked it out, and he breathed deep three times before the smoke was entirely out of his lungs.

Then I said: “You’ve gone and got yourself a whole flock of new clothes since I saw you last.”

“Yeah,” said he, “you know the way Dug is. He’s always trying to dress me up.”

“Yeah. I know,” said I.

“That’s the trouble with Dug,” said the kid. “He’s kind of a dude.”

“Yeah. He’s kind of a dude,” said I, “but he’s all right.”

“Yeah, sure, he’s all right,” said the kid. “But he’s a dude. He’s always fixing himself up and dressing up. You know what he did down in Tahuila?”

“What did he go and do there?” I asked.

“He done himself up in Mexican clothes. All velvet and such stuff. And he went and got a big plume to curl around his head. He thought he looked fine. He was always standing around and spreading his legs and looking at himself in the mirror and curling his whiskers with one hand.”

“I bet you handed him something,” said I.

“Yeah. I handed him something,” said Chip. “But he didn’t care. He’s getting so he don’t care what I say to him.”

“He knows you kind of like him,” said I.

“Think that’s it?” said he.

“Yeah. That’s it,” said I.

“Well, maybe,” said Chip.

I swallowed a smile. He and Dug Waters were closer than brothers. I was pretty thick with them, too. But what they meant to one another was real blood. They’d owed their lives, each to each, I don’t know how many times.

“What did he do when he got all dressed up?” said I.

“Aw, he goes and crashes into a dance,” said Chip.

“Did they try to throw him out?” said I.

“Yeah, they tried,” said Chip, and yawned heartily. He went on: “He stayed quite a while, though. The furniture got sort of busted up, and his fine clothes were spoiled, but he kept the music playing, and he kept on dancing. I gave him the sign when the cops were coming, and then he left. But that’s the trouble with him. He’s always dressing up. You know how it is. You always get into trouble when you’re dressed up.”

“How’d you lose half of those suspenders?” I asked him.

“That was a shack,” said Chip. “He reached for me as I was getting off the back end of the caboose on a grade. He got half the suspenders, but he didn’t get me.”

“That’s good,” said I. “How about the sleeve of the shirt? What happened to that?”

“A funny thing about that,” said Chip. “The railroad cop, when he grabbed me, he grabbed so hard that when I popped out of my coat I had to tear that sleeve right out of the shirt, too, before I could shake him. You never seen a guy with a grip like that cop had.”

“Where was this?” I asked.

“Aw, in a railroad yard,” said Chip. “This was one of them mean cops. You know the real mean ones?”

“Yeah. I know.”

“He comes cruising up to me in the dark,” said Chip. “He makes a pass at me, and all his fingers are fishhooks, what I mean to say. He grabs me and he holds me. I have to peel out of the coat and the shirt sleeve. The talking that cop done as he heeled after me, you’d’ve laughed to’ve heard it, Joe.”

He himself smiled faintly, a little wearily, at the memory.

“That was hard on the shirt, all right,” said I. “You got a pretty bad rip in those trousers too.”

One side of them was almost torn away, and had been loosely patched together with sack twine.

“You know how it is about a window?” said Chip. “I mean, the nails that are always sticking out around a window? That was what happened. I was clean through and ready to drop for the ground, and nobody had heard a thing, and then I got hung up on a nail. It makes me pretty dog-gone sore, Joe, the way carpenters make a window. Dog-gone me, if I was a carpenter and called myself a carpenter, and set up for being a carpenter, I’d be one, and I’d hammer in my nails, and I’d countersink ’em—around a window, anyways.”

He was very indignant. His anger helped to take his weariness away.

“Yeah,” I said. “Carpenters are no good. Who’d want to be a carpenter, anyway? But what window were you climbing out of?”

“Aw, it was nothing,” said he carelessly. “It was just a bet I had on with Dug Waters. He said I couldn’t break into a house. I said I could.”

I began to perspire a little.

“What did you get, Chip?” said I.

He turned his head quickly and glanced at me.

“Whatcha think?” said he. “I ain’t in that line. I never ain’t going to be in it, either, what’s more.”

“That’s right,” said I. “You’re a good kid, Chip.”

“Aw, go on. I ain’t a good kid, either,” said he. “But I ain’t a thief. I don’t go around stealing. That’s all I don’t do.”

“Just a chicken now and then?” said I.

“That’s lifting. That ain’t stealing,” said Chip calmly. “You oughta know the difference between lifting and stealing, oughtn’t you?”

“Sure,” said I. “There’s a lot of difference. How do you feel, now?”

“Me? I always feel good,” said he. “How about you?”

“I’m all right. I’m just kind of down now, because I’ve used up my tomatoes.”

“Have you?” said Chip. “Well, you’re gonna get some more.”

“When?” I asked him.

“Pronto,” said he.

And he held up one finger to make me listen. I heard it, then. It was the thin, silver music of a bell, beyond the shoulder of the hill.

“What’s that?” I asked him.

“That’s my hoss and mule,” said Chip.

“Oh,” said I. “Then Dug Waters is coming after you, is he?”

“No,” said Chip.

“Who’s with ’em, then?” I asked.

“Nobody’s with ’em,” said he. “There’re by themselves.”

I looked at him pretty hard, but he paid no attention, as though there were nothing really worthy of attention in what he had said. He merely looked off across the blue and red of the evening, toward one great polished face of granite which took the light and gave it back as a mirror would.

“Maybe you’ve worked a charm on ’em?” said I. “And they can’t help following you?”

“I got a charm, all right,” said he. “I got the meanest mustang in the world, all right. He’s a charm! But he’ll follow me. He’ll follow me around like a dog, because he gets pretty lonely without me. He don’t feel nacheral at all without somebody in the saddle that he can annoy a little. If it ain’t bucking, it’s reaching around and taking a bite at my foot; and if there’s a cliff handy, he likes to walk right out onto the edge of nothing and bite a couple of chunks out of it, and he don’t turn back until the cliff is crumblin’ under his feet, and even then, he don’t hurry. Then he likes to give me a rub against a handy boulder along the way, that cayuse does. And if he ain’t bucking, he’s always humping his back like he was about to begin, so’s your nerves never get good and settled down.

“He’s so fond of makin’ me miserable that he can’t do without me. I’m his kicking post, and he certainly likes to kick. He’s lammed me three times on this trip, and he’s gonna lam me three times more; and I’ve seen the air around my head all full of his heels. That’s the kind of a mustang that he is! He can’t do without me. So I know that he’ll follow me, because he’s got a gift of scenting like a wolf, and so I hang a bell around his neck; and the mule is an old train mule, and follows that bell like it was a bag of oats. And when I get tired of fighting the cayuse, I hop off and take a walk ahead, like now, and he’s sure to come after me. First he balks, and pretends that he ain’t coming, but when he remembers what a lot of fun he’s had pounding me, he always gives in and comes along after.”

When Chip got through with this explanation, over the shoulder of the mountain, between two runty piñons, I saw the procession coming, the little mustang first, and a longlegged, knock-kneed, pot-bellied mule behind him.

That cayuse came up, and my burro began to bray, it was so glad of having company. Right up to Chip that mustang came, and reaches down and takes off the battered old felt hat that Chip is wearing.

“Aw, quit it,” says Chip, without turning his head, and sort of tired. “Quit it, and go off and lay down, or I’ll get up and slam you one.”

Well, it amused me a good deal to see the mustang drop the hat and go off to the side to pick at some bunch grass. It amused me, because it seemed as though he had understood.

He was the meanest-looking horse that I ever saw, with a Roman nose, and a red look about the eye; and there was that hump in the back that always means a hard gait and a mighty good bucker.

“How’d you come to pick out that horse, Chip?” said I.

“Out of a hundred,” said Chip. “I could have had my pick of the whole bunch; but while I was looking, there was a fight started in the corral between a great big sixteen-hand bay, with quarters like a dray horse, and this little runt. And they just backed up against one another and let drive. Every time the bay kicked I looked to see the runt exploded right off the face of the earth, like gunpowder. But every time it kicked, its fool heels flew over the back of the cayuse, and every time the cayuse kicked, its feet went into the big fat quarters of that bay like a clapping of hands. After a while the bay had enough, begun to squeal and run away, and this little wild cat run after him, and took out a chunk with his teeth while the bay was running. ‘Shoot that blankety-blank hoss-eating mustang!’ yells the boss. ‘No,’ I says, ‘sell it to me!’ So that’s how I got him.”

I got through laughing, and I said: “Where are you bound, and what for, Chip?”

“I’m bound to you from Waters,” said he. “Take off that saddlebag and you’ll see why.”

I went over and navigated around the bronco until I got the saddlebag off. I brought it back and opened it, and dumped out the contents on the ground; and what I saw was a whole stack of packs of cards, except that they were bigger than packs of cards, and at the ends of them I could see the figures.

And all at once I threw up my hands and let out a howl, because I knew that all that stuff was United States green-backs, lying there on the rocks before me!

SOMETIMES I had daydreamed about how good it would be if I could run into a flock of money like that—sort of have it poured down before me by the dropping of the tailpiece of a government truck, or something like that. I had always felt that the joy would run up through my veins as bright as silver.

But I was wrong.

At least, out there in the center of the Nevada desert, the first thing that I did was to throw a look around over both shoulders, and the second thing was to go and grab my rifle and shove some cartridges into it.

Even then I didn’t feel very easy, because my hands were shaking, and I was as cold as ice all around my mouth. My voice quaked when I came back to Chip and stood over him.

“You little son of torment!” said I to him.

He only grinned at me.

“Gimme the makings, Joe,” says he.

“You don’t smoke till you’ve done some talking,” says I.

He grinned again. He settled himself back against the rock as though it were a pillow and folded his arms under his head, with his skinny elbows sticking out on either side.

“Go on,” said he. “What d’you wanta know?”

“Everything,” said I.

“That’s easy,” says the kid. “Once upon a time there was a bank, and inside of the bank there was a president that knew how to suck the gold out of people like a spider does blood out of flies, and inside of the president’s office there was a safe all bright and shining and new and guaranteed, where the president laid up the gold. And now there’s the same bank, and the same president, and the same safe. But there ain’t any door onto the safe. Leastwise, there wasn’t the last time I saw it. And a couple hundred thousand dollars’ worth of lining is gone, too, right out of the president’s safekeeping.”

All the rocks and the mountains shifted and wavered a little as I heard this. I looked down at the little pile I had turned out of the saddlebag.

“Two—hundred—thousand!” said I.

“Yeah. Or nigher onto a quarter of a million,” says the kid.

I looked at the loot again.

It didn’t seem to me like stolen money. It seemed different; I can’t say why. Because there was so much of it, that it seemed almost right and good to have taken it. I thought of a lump of gold weighing eight hundred pounds. It would load down two mules solid. And that was what that little stack of paper meant. It was a treasure. That’s what I thought of it.

Murder came hot up in me. I want to be honest and tell the horrible truth about it. I had half of a mind to tap the boy over the head with the butt of the rifle and then all of this money would be mine. I took my knuckles a good hard swipe across my forehead, and then my brain was clear, and I was able to think and see right again.

I found that Chip was stretched out there in just the same position, looking up at me with a funny little smile.

He nodded. “Yeah, I know,” said he.

“Do you?” said I, and I stared down, and saw that his bright, wise eyes were full of information and understanding.

“Yeah,” went on Chip. “I had the same idea. When I started away, I was a mind to cut and run, and never see Waters again if I could help it. But then I remembered, and didn’t.”

“Remembered that he’d track you down?” I asked.

“No. I remembered that he wouldn’t try,” said Chip.

I let this idea go through me with an electric jump, and I saw that it was true. After all that Chip had done for Waters, Dug never would lay a hand on him, no matter what else he did. Not for a quarter of a million in hard cash.

“How did he do the trick?” I asked the boy.

“How did he do it? Oh, that was easy. He just chloroformed a watchman and cut his way in, and cut his way out. It was an easy job. That bank had plate-glass windows, and you could look through them into the lighted insides of the bank, day and night, and see the safe. And the light was still shining inside the bank all that night; but Dug, he just washed a couple of the panes of the window glass with soapy water, and after that, everything you could see from the street was a mist. And he worked inside as easy as you please.”

I nodded. I could see Waters, cool and easy and calm, doing his work inside the bank, with no other screen to protect him than a film of mist through which the passersby could half see. I thought of the cleverness of it, too—people who wandered down the street that night would never give the soapy windows a thought. But a curtain or a shade drawn would have been a different matter.

“Go on,” said I.

“To what?” asked Chip.

“To where you start and Dug stays back.”

“Well, they guessed at Dug, and he knew that they’d guess at him,” said Chip, “and just then they didn’t have anything on him, but they were pretty sure to lay a slick job like that to his door. So he sat still and let them grab him and third-degree him, if they wanted to. And while they were working over him, there was me, all dressed up in a new suit of clothes, and with a good saddlebag crammed with the stuff, hiking it down the railroad. I lost some of the clothes, but I come through with the loot.”

“How did you find me?” I asked.

“Well, I dropped in at Newbold’s place. And Marian Newbold, she went and cried all over me. And she was going to reform me and get me sure jammed into a school this time. But I managed to find out that you were off in this direction, so I slid out at night and barged along, and the next day I bought me this outfit and hit the desert up this way. I happened onto the place where you bought your own outfit, and they gave me enough of a lead to follow along for quite a ways. The rest was luck.”

I considered this for a moment. I mean to say, I thought of the nerve of Waters in trusting that fortune into the hands of the boy, and the dangers that the kid had gone through, beating his way a thousand miles, I suppose, to find me. But here he was, true as a homing pigeon, arrived at me!

It was an amazing thing. It was so amazing that I went over and unsaddled his horse and mule while I thought it over still longer. He got to his feet to help me, but I saw the waver of him through the dusk, and I told him to sit still. He could be the guest, tonight, and I’d take care of things.

I did. I dragged in the packs and the saddles under the boarding about the mouth of the shaft, and under the lean-to where I lived, though there wasn’t much room in that.

Chip had brought along all the supplies in the world. There was no reason why he should have bought both a horse and a mule; but he said that he really did not know how long he would have to cruise before he found me, and so he had prepared for a voyage of any length. With his pockets full of cash, he did not spare his funds, but he laid in the best of everything.

There were the cans of tomatoes that he had promised. And I don’t know anything better than canned tomatoes on a trip. They put seasoning into even the toughest old sage hen, and they make you a drink that beats beer, even—there’s a good, sour bite to it. He had jams, and the best kind of white flour, and the finest bacon you ever saw, and plenty of coffee, and the little runt actually put in some pickles, too. He sure was a regular food caravan, that kid!

We ate a supper that nearly burst us both, and then we laid back, and I stoked up on my pipe and pulled off my boots, and wriggled my toes in the cool of the night breeze, and saw the stars drifting and drifting up over the mountain heads, and showing through the valley rifts, until it seemed as though they were rising out of the ground and setting into it again like undying sparks from a fire.

“Now you tell me why you’re here, son,” said I.

“Because it’s a long time since I seen you, and I had to go somewhere,” said he.

I shook my head. I looked across the deadness of the firelight to the face of the kid, and the bright glint of his eyes.

“You liar, you come clean with me,” said I.

“Yeah, I’m coming clean,” said Chip. “The fact is that everything looked pretty good. And then I heard that Tug Murphy had hooked into the traces and was going to work on this job.”

Tug Murphy!

Dug Waters!

It was not the first time that they had tried wits against one another. And it was not the first time that Chip had thrown his weight decisively into the scale.

That Irish sheriff was not the cleverest fellow in the world, but he was a bulldog on a trail, and he was likely to get by persistence what smarter men missed, in spite of their brains. It gave me a stir to hear that name. I could see the red fighting face once more. I could hear the rasp of his voice against my ear.

“What has Murphy got to do with this game?” I asked.

“He’s on the trail,” said the boy. “I didn’t mind the others. I would have stayed put. They wouldn’t suspect me of anything. But Tug Murphy is different. He’s got brains, and he knows where to look for the most trouble. So, sometimes, he might give me a look. And a whole saddlebag full of stuff ain’t so easy to hide.”

“He’s a mean man to handle,” I admitted, “and he’s a hard one to get away from. There’s no doubt about that. Still, old son, I don’t quite know what brought you out here.”

“It’s like this,” said the kid gravely. “There was Dug Waters all surrounded night and day, with the dicks watching him and every move that he made. I couldn’t get to him to ask him what to do. And when I heard that Murphy was taking the trail, then I knew that I’d have to get close to somebody a little older and with more sense than me. And, of course, I thought about our partner. I thought about you, Joe. So here I am.”

“Hold on,” said I. “You thought about me?”

“Why, of course I did,” he answered quickly.

“But look here, son,” said I. “I don’t have any share in deals like this. I don’t work—in this line.”

“Yeah, but you’re a friend,” said Chip.

I stared at him. I saw his meaning. A friend is a friend, no matter what the strain.

“But, suffering Moses, Chip!” said I. “Don’t you realize that Tug Murphy knows that I’m a friend of yours and Waters’s? Isn’t he likely as not to come for me, if he hears that you’ve disappeared in this direction?”

THIS idea of mine had not occurred to Chip, it appeared. He scratched his head for a time and then nodded across the dimness of the firelight.

“It was a wrong steer that I had,” said he. “I ought to’ve remembered that the sheriff knew you were in with us in the jail break when we got Waters loose. I just forgot, kind of. I was a fool, Joe, I guess. But tomorrow I’ll start along.”

It made me feel sorry to see the boy repentant. That was a humor one didn’t often spot in him. Generally he was fighting back if you tried to corner him.

So I said: “Look here, Chip. It’s all right. Don’t you worry about the thing. I’ll manage it, all right. And after all, this is a tolerable big country for even the sheriff to find us in.”

“Aye,” said Chip, “but I’ve blazed the trail out here the second time. And just supposing that he should turn up!” His shoulders twitched. I saw him shudder.

“Well, it’s all right,” I said vaguely.

“It ain’t all right,” said Chip. “Because if he seen you with that saddlebag loaded with coin, what would he be thinking? Nothing at all, except that you were in on the deal.”

“Oh, I can easily prove that I was out here when the robbery took place,” said I.

“Yeah, but there’s receivers of stolen goods, and all of that,” said Chip.

“Yes,” said I. “There are those, all right.” I added: “You know a good deal about this stuff, it seems to me, Chip.”

He sighed, and then he answered: “You know how it is, Joe. I hear a lot from Dug Waters. And I hear a lot from his pals, too.”

“What pals has he got now?” I asked. “He was playing a lone hand, mostly, when I last heard about things.”

“You know how it is,” said Chip. “When a gent has played the game for a while, he gets sort of careless. I mean to say, he gets to thinking that he will always be able to beat it. And that’s the way with Dug. He’s nearly always beaten the law. And now he thinks that the law is a pup. He used never to trust nobody but me. Now he begins to trust everybody, it seems. He’s softening up a good deal, I guess!”

I could have sighed, myself.

It was a wonderful thing, the way that boy had stuck to Dug Waters. They loved each other. They would have died for one another. And Dug Waters kept the hands of the kid clean all the while that he himself was going from gun fight to robbery to knife brawls. He watched out for the lad all the while, and the lad watched out for him. I was mighty fond of Dug. He was a little elegant, and had his eyebrows in the air a good part of the time, but he was the real stuff, and a friend that never forgot you. And that last thing is the most important in the world, I think.

So I stared through the dull of the firelight toward the boy, and I wondered what would come of him, and how he could possibly live that life of companionship with Waters without eventually becoming as outlawed as Waters was. Waters was having a free spell. He had been cornered. He had stood trial. And one of the smartest lawyers in the Southwest had freed him. It cost Waters a fortune, but now his record was smudged. The herring had been pulled across the trail, and he could come and go with all the other legal-minded people of the world.

It was all right for Waters. But what about the boy?

I said: “What are you going to do about settling down, Chip, one of these days?”

“Settling down?” said he.

“I mean going to school, and all that,” I suggested.

“Oh, I dunno,” he answered gloomily. “Don’t be so dog-gone sour, Joe, will you?”

“All right,” said I. “We won’t talk about it.”

“I think about it plenty,” he went on. “But I can’t cut away from Dug. He needs me. He gets pretty crazy when he’s left to himself. He gets to acting like a lord, or something. He orders his ham and eggs on a gold plate, you might say. There ain’t any sense in that. And Dug needs me. I sort of straighten him out. He’ll listen to me—a little!”

He sighed again.

“You go to bed, son,” said I. “You’ve been up a long while, and you’ve had a long march.”

He nodded, stood up, stretched, and rolled down his blankets. But before he turned in, dead tired as he was, he went off and found the mustang and rubbed its nose with his fist.

“Good night, you old son of a gun,” said he. “I’m gonna be braining you one of these days.”

Then he came back and turned in.

But I sat up a while. I was bothered by several things. One was pity for Chip, and wondering what was to come of him. One was thinking of that saddlebag loaded with a fortune. And one was of Sheriff Tug Murphy, somewhere out in the desert, most likely, and very apt to be headed my way.

Well, it was a bad business, it seemed to me. But finally I turned in myself, and lay there for a while until the stars grew misty and dull; that was the moment I went to sleep.

I woke up with something tapping the sole of my foot. I didn’t open my eyes. I just said: “Don’t be a dang fool, burro. Get out of here!”

He used to have a way of doing that, that fool burro I had with me. I mean, he’d come and paw at my foot, or maybe at my hand, in the middle of the night. Just for meanness, or for company; I never could make out.

That tapping at my foot kept on. So I opened my eyes and looked up to the sky, and there I saw the moon riding well above the eastern mountains, and the cold of the night air was on my face and eyes, so that I knew I had been sleeping for quite a time.

Then I looked a little lower, and I saw the sombrero and the shoulders of a man standing below me.

I didn’t need another tap at my foot. I woke up pronto. And I sat up, too, and saw a burly fellow standing there with the moon over his right shoulder.

“Hello, Joe,” said he.

I recognized the voice. I recognized the iron rasp in it, I mean to say. It was Sheriff Tug Murphy!

“Hello, Tug,” said I. “This is a lucky kind of a surprise.”

I stood up.

“Yeah, I guess it’s kind of a surprise,” said Tug Murphy. “Just mind your hands a little. Don’t make no funny moves.”

“I won’t make any funny moves,” said I. I added: “What’s up? You’re not trying to hang anything on me?”

“I dunno that I’m gonna hang anything on you,” said the sheriff. “I’m just hankering after a little of your conversation.”

“That’s the way with bein’ bright,” said I to him. “People enjoy your talk so much that they just can’t get along without it. They gotta ride a coupla hundred miles across the desert to hear some more of it. Sit down and rest your feet, Tug. I’ll wake up the fire and get some coffee started for you.”

“You just step into your boots,” said Tug. “We’ll let the fire and the coffee take care of itself for a while.”

I dressed. And all the time I was looking out of the corner of my eye at the shine of the leather of the saddlebag that lay beside the dead embers of my fire. And in that bag there was enough to soak me into prison for ten years, I guessed.

I looked a little farther to the left toward the blankets of the kid. The blankets were there, but the kid wasn’t. There was no sign of him.

He must have heard a noise and waked and got away. I took it pretty hard of him that he hadn’t given me a sign, or taken away that danged saddlebag, at the least.

I dressed, as I say, and then I threw some wood onto the fire, and it began to fume and smoke. I filled the coffeepot with water out of the bucket. That water in the bucket was standing so still that a star had dropped down into it, I remember. And after the water got through slopping around, the image of the star came shuddering back again, all split and shattered into pieces. But settling down into its old self.

I was pretty thoughtful as I raked that fire together and put the pot on top of two rocks, where the flame started to lick at it and curl around it.

“A funny thing about a coffeepot,” said the sheriff. “It draws the fire to it, sort of. Ever notice that?”

“Yeah,” said I. “That’s a funny thing, but I could tell you a lot of funnier ones.”

“Like what?”

“Like you being out here,” said I. “What kind of a brain storm have you got, boy?”

Tug Murphy laughed.

“You mean you’re too dog-gone virtuous to be suspected, eh?” says he.

“Well, you know me, Tug,” said I.

“I know you, all right,” said he.

“And what have I ever pulled except a wad of tobacco out of a hip pocket?”

“That may be a true thing,” says he. “I dunno. That may be a pretty true thing. But you know how it is, old son.”

“What way?” said I.

“I mean, you know that rocks don’t melt very easy.”

“Yes,” said I. “I know that pretty well.”

“But still, there is fires that can melt ’em.”

“Go on, Tug,” said I. “I’m getting sort of tired of all this. What are you talking about, anyway?”

“I’m talking about two hundred and fifty-three thousand dollars!” says the sheriff.

I whistled. “That’s enough for me,” I said. “I’ll take that much. But what are you driving at?”

“That money’s missing from the bank,” said the sheriff. “And I’m out here after it. You see that I’m playing my cards all on the table in front of you, boy?”

“Yeah, I see that,” said I. “That’s a compliment that you’re paying to me, Tug. I’ve gone and wished a quarter of a million out of a bank and laid it up here. Is that it?”

I grinned across the fire at him, and he was still as serious as could be.

“I know that the kid trekked in this direction,” said he. “And I know that he must have been heading for you with the cash. Now I’ll tell you this. Turn over the boodle and there’s not a word more said. The bank wants it too bad. Turn it over, and there’ll never be a word said to you about the job, son!”

IT gave me a jump to hear him talk, and that I’ll admit. I mean to say, there was the saddlebag, still in the corner of my eye, and if the sheriff should open it—out would come penitentiary for me. And if I turned over the stolen goods, there was an end of the trouble. I tell you that I was tingling to tell him and just point out the saddlebag.

But then I thought of Dug Waters. He had been true blue with me. He had had my life in the palm of his hand once and he had let me go. He had saved me.

You can’t forget things like that. And there were other things between us—a lot of them. It’s true that I never had worked with him on any of his crooked jobs, because that’s not my line. But nevertheless, there had been a good deal between us, and I was mighty fond of Waters. There was the kid, too. What would Chip do if I let the saddlebag slip through my fingers into the hands of the law? He would never forgive me, and that was plain!

Well, during about a tenth part of a second I thoroughly sifted every one of these questions, and then I decided that, law or no law, danger or no danger, friends came first, and I couldn’t blab.

“Tug,” said I, “it’s a sort of inspiring thing to hear you ask me for a quarter of a million. It shows the kind of faith that you have in me. There may be a quarter of a million in these mountains, but my luck is so bad that it would take me a thousand years to get it. Right now I’m taking about four or five dollars a day out of this here ground, and breaking my back, at that.”

When he heard this he laughed a little.

“You know what I mean, old son,” said he. “I’m talking about cash from a bank. And the kid must have brought it here.”

“You mean Chip?”

“Who else would I mean?” said he.

The coffee was beginning to simmer and to throw up the nose of its steam straight out of the spout, and the fragrance spread around over the place and smelled pretty good.

“Chip’s not been here,” said I.

He lurched his shoulders forward and stuck out his jaw.

“He’s not been here?” he echoed.

“No,” said I, as steadily as I could. “He’s not been here.”

And I looked straight back across the fire into the eyes of the sheriff.

I could see the savage twist of his lips and the evil in his eyes. A mean man was Tug Murphy when his blood was up, and it didn’t take much to get it up.

“Have a can of coffee,” said I. “There’s no poison in it. Here’s some sugar, too.” I handed the things over.

He stirred in the sugar, still staring at me as though he could eat me.

“What you doin’ with sugar this long out?” said he. “How come it lasted so long?”

“You know,” said I, “that I’ve always had a sort of sweet tooth. So I take along a good supply. But the fact is that this isn’t my sugar.”

“No,” said he, “I’ll bet that it’s not your sugar. It’s the stuff that Chip brought.”

“Chip?” said I. “You’ve got Chip on the brain.”

“I got reason to have him on the brain,” said he. “He’s laid me the trickiest trail that I’ve ever followed—and I’ve rode after Indians, son!”

“Yeah, Chip could lay you a hard trail to follow,” I agreed. “But I guess you won’t find him here, Tug.”

He shrugged his heavy shoulders. The coffee was very hot, so he sipped it noisily. And then, breathing up it, he sipped it again. He was not a pretty man to watch, I can tell you, and he was staring at me as though I were red meat.

“Old son Joe,” said he, “I reckon that you’re lyin’ to me.”

“All right,” said I. “You go on reckonin’. And the real crook will be getting miles away from you.”

He only grinned. “You out here all alone?” he said.

“Me?” said I.

“Yeah. They told me back yonder that you’d come out all alone.”

I remembered the rumpled blankets of the kid, and I answered:

“No, I’m not alone. I was alone when I started, but I’m not alone now. A funny thing happened. You know old Chris Winter?”

“Yeah. I know old Chris,” said he. “I used to, anyway.”

“Well,” said I, “old Chris, he got it into his head that he’d strike out in this direction, and when he heard where I intended to prospect, he came along and found me, and we teamed up. It’s pretty good to have somebody to talk to, you know, even if it’s no more than old Chris.”

“Sour old sinner, ain’t he?” said the sheriff.

“Yeah. He’s sort of sour, but he’s all right,” said I.

“Where is he now?” asked the sheriff. “Does he smell sheriffs a long distance off and get restless and go walking?”

“You know how it is,” said I. “He’s got insomnia.”

“No, I don’t know how it is,” said he. “He’s got ‘in’ what?”

“’Somnia,” said I. “He can’t sleep very good.”

“Can’t he?” said the sheriff. “Maybe he ain’t got the words, but he certainly can play the tune. I recollect makin’ a trip through Inyo County in California, and old Chris Winter was along, and dog-gone his heart if he didn’t make the mountains tremble all night long, he snored so loud! I never heard such snorin’.”

“It must’ve busted down his nerves,” I suggested. “Anyway, he’s a pretty light sleeper now.”

“Dog-gone me, but I’m glad to hear it,” said Tug Murphy.

“So he gets up,” said I, “and he goes off for a walk in the middle of the night when he finds out he can’t sleep. It’s hard lines on the old feller, all right. But he don’t whimper much.”

“How long has he been out here with you?” says the sheriff.

“Quite a spell,” says I. “Let’s see: yeah—it’s quite a while, now, that the old boy has been out here with me.”

“That’s a mighty interesting thing,” said the sheriff. “Does he look kind of nacheral, too?”

“Why, sure he does,” said I. “That face of his couldn’t look anyway but natural. It would break, otherwise.”

I thought this was a pretty good joke, so I laughed a little, but I couldn’t help noticing that the sheriff did not seem to be in the least amused.

Then he says: “There’s a lot of interest in this for me. I’ve always been pretty interested in ghosts and spirits and things.”

“What do you mean?” says I.

“Why, man,” says he, “ain’t Chris been dead for three months and more?”

It was a hard jolt for me. It was a punch on the point of the chin, so to speak. I got my breath and my wits back as well as I could.

The sheriff went on: “Chris was workin’ on the Morgan and Rister crew, and he goes and falls down a shaft. Now, wasn’t that a fool thing for an old hand like him to do? But I’m glad to see that his ghost has come out here to carry on with the drill. He was always a wonderful good hand with a single jack, was Chris Winter.”

I let the sheriff carry along. I was trying to think. But I couldn’t make much progress. He was grinning and chuckling all the while.

“Well, Tug,” I said at last, “the fellow who’s out here as my partner is not Chris Winter. Though I wish that name had gone down. He is a light sleeper, though, and he don’t want to see you.”

“I’ll bet he don’t,” said the sheriff. “In a word, you might as well admit that it’s the kid.”

I shook my head. I grinned at the sheriff. I poured out another can of coffee for him; but all the while he was studying me with a lowering look, and presently he said:

“You know, Joe, that you’re stepping pretty deep into this business. I don’t want to do you no harm. So far as I know, you’ve always been straight. But if I have to take you back to town with me, they’ll slam you into the pen for a pretty long term. The judges and the juries around here in Nevada are getting pretty mean. You gotta fish and drag about fifty or a hundred square mile to get yourself a jury, in the first place; and all that riding the jurymen have got to do, day after day, it riles them a lot. They vote you guilty because they’re saddle-sore! Now, Joe, you straighten up and tell me the truth, and it’ll be all right. But if you don’t, I start trouble right pronto.”

I admired to hear the way that the sheriff put the case. It showed that he was a pretty straight fellow, at heart. I liked Tug Murphy before. I liked him better than ever, now.

But what could I do?

I already had thought the thing back and forth. He had proved me a liar, on the jump, and now what was I to do?

Well, finally I shook my head. I said:

“Tug, suppose that everything you think were true—which it isn’t—still, I wouldn’t help you any. You ought to know that I couldn’t.”

“Because the kid’s your friend, and Waters is your friend,” said he.

“Put it any way you like,” said I.

“Then—stick your hands out!” says he.

He took out a pair of handcuffs and held them on his left hand.

“Aw, come along, Tug,” said I. “D’you think that I’m going to try any gun play?”

“I don’t like to put irons on you, Joe,” said he. “I’ve seen you to be too dang decent for that. I don’t want to do it. Will you give me your word that you’ll sit tight and make no move while I take a look around this here camp?”

“Well, I’ll do that,” said I.

“Not make no move at all?” he insisted.

“No, I’ll sit tight,” said I.

He hesitated, and then he nodded. He dropped the things back into his pocket, and I was glad to see them go. Then he stood up and looked around the camp. There was not much to it, I know, but the mischief told him where to go. He walked out, first, and found the mule, and rubbed his hand along the side of it.

“The pack saddle come off this mule no later than tonight, Joe,” said he. “I can tell by the salt that ain’t rubbed out of the hair yet.”

I said nothing, because there was really nothing to say. I felt like a fool because I hadn’t rubbed the mule and the bronco down.

Then Tug came back toward the fire, stubbed his toe against the saddlebag—and opened it up!

He just pulled one handful out of that bag and stood there looking not at what he held, but across the fire, toward my face.

WELL, to make a pretty long story short, we started on the march for jail. We only waited for the morning, and then we lighted out together. The sheriff had come out with a change of horses. He had two good, tough mustangs, rather lumpy in the heads, and with hips like the hips of cows. But they could keep going through fire. And that’s the sort of horse one wants for riding through Nevada.

Tug Murphy was pretty decent to me. He just arranged a rope that run from one of my wrists to the other, and left about a foot of play between my hands. That way, I could make a smoke, light a match, and even do my share of work around camp when he halted. It was only, as you might say, a short hobble for my hands. The sheriff apologized for it. I’ll never forget his apology. He said:

“Look here, Joe. I could take you in with irons on, which would make you feel like a dog. Or else I could put nothing on you at all. But that would mean taking your word for honor first that you wouldn’t escape. And I’ve got no right to take your word on that. If you have a right good chance to bust me over the head and make away, you go ahead and do it. It’s your right. Because, as sure as tarnation, I’m takin’ you in for a long stretch up the river. But now I’ve got the rope on you, it makes me easier; it makes you more comfortable; and it’s better all around. Only, it makes me feel pretty mean to rope a man like a calf. And a he-man, and a real man, like you, Joe!”

I appreciated that compliment, coming from the sheriff. He didn’t drop many like it in his conversation, you may be sure!

Well, of course I couldn’t blame the sheriff. I only wondered what the deuce would become of me, and now and then, inside my mind, I certainly danged that boy Chip. For he had known that the sheriff was on his trail, and yet he had led right out to me. Well, now the thing was ended, and I was due for prison, and I groaned as I thought about it.

What shall I say about that inland voyage? I’ll only say this, that all the beauty went out of Nevada, as I rode along. All the beauty went out, and the ugliness came in.

The blue went out of the sky and the color went out of the distances.

For one thing, just as we started, the Old Nick stoked up in his furnace and turned on an extra blast. Perhaps I was not so used to the heat of the valleys, I had been working such a height up the side of the mountain; but when we dropped into the bottom, it was like dropping into a white road. The glare shot up through the eyes and came out at the top of the head.

I knocked along pretty much like a mule, with my head down. Sometimes a hot wind came shooting at us and the mustangs put their heads down and just shuddered and endured it. But they could not take a step until that wind had gone by, in a whoop. One of those blasts would take every drop of moisture out of the clothes and off the face, and just leave salt traces where the perspiration had been. When the horses were dripping with moisture, they would be wiped dry in ten seconds, and the salt lay all over their hides in little lines, like those the waves leave on the shore.

I’ve seen it hot in other places. Perhaps humid heat is worse. But I’ve never hankered after living on the hot side of an oven, and that was what we were riding through.

The sheriff didn’t mind it so much.

I wouldn’t have minded, either, if I’d been in his boots. He was pretty sure to get at least a ten-thousand-dollar reward from the bank, unless the bank was a set of pikers. Besides, there was the fame.

Tug used to talk over the possibilities of what he would get. It was his favorite theme all the way we rode together.

The first night we camped out in the naked flat, a dry camp. Tug wanted to shoot the burro and the mule. He said that he would charge the expenses off to his personal account. But I wouldn’t let him shoot the burro. That mean little beast had been company for me too long up there by the mine. It had seen me through some lovely spots, and I liked the cock of its long, wise ears. That burro could carry his own weight on a cupful of water and a ham sandwich, so to speak. I’ve heard the camel praised for powers of endurance, but the camel is a regular parlor exhibit compared with a real, hundred-per-cent Mexican burro. As for the mule, that belonged to Chip. I couldn’t tell the sheriff that—no matter how sure he was—but I gathered that it wouldn’t be a good idea to put a bullet through anything that belonged to that boy. I said so, and the sheriff saw the light.

“He’s Irish,” said the sheriff. “He’s Irish, like me. And you never can tell where an Irishman will put his heart. Might put his heart on a woman, a horse, or a stone. But when he does, that woman, that horse, and that stone he’s ready to die for. No, I guess that I’d better not shoot the mule. It might be Chip’s favorite.”

It was a strange speech to listen to, that.

So we slogged along right out into the flat middle of the desert. That was not a dry camp, thank goodness. There was a little pool of alkali water. It was scummed around the edges, and it was bitter as aloes. But it tasted good enough when it was made into coffee. We drank our coffee, and ate our flapjacks and bacon, and felt the heat still rising from the ground like steam.

Great Scott, how hot it was!

Then the night breeze wakened and came softly about us, flowing like water, and we took off our clothes mostly, and let it blow. And while we were lying there in the blankets, for a while, cooling and trying to forget that the next day’s march would be a lot worse than this one, the sheriff said:

“We’ll have decent water, at the end of that march. I know where the pool is. It’s fenced all around with rocks. It comes up and starts to flowing, and it goes about twenty feet and then goes down under the sand again. But it flows enough to keep it sweet, and it’s cool, too, and there’s a couple of specks of blue that fall into it out of the sky; but all the rest of the face of it is kept dark by the shadow of the rocks. It’s the kind of a water hole that a man could dream about.”

“Shut up, Tug,” said I. “I’m dreamin’ about it already. I’m thinkin’ how it will wash the road down my throat. That’s what I’m thinkin’ about. And the alkali—there ain’t any alkali in it, you say?”

“It’s as sweet,” said Tug, after a moment, “as heaven! As sweet as heaven with stars in it. And that’s what I mean! It’s a dog-gone honest spring, that’s what it is!”

All at once, I felt the whole lining of my throat go dry and crack with yearning, but I didn’t get up to take a drink from our pool of this evening. I knew a little too much for that. The more you drink of alkali water, the worse off you are, and all the sicker. It only keeps you from dying of thirst, and that’s all.

Says the sheriff: “Maybe they’ll make it twenty-five.”

I knew that he was thinking about how big his reward would be. I said nothing. Just then, the mule gives a snort, and then starts into a loud braying.

“What’s the matter with that fool mule?” said the sheriff, and sits up. “What’s it seen?”

“Nothing,” said I. “You know the way it is with a mule, Tug. You know why it starts in to braying, once in a while, like it was crying for help?”

“Yeah. I know what you mean,” said he. “You tell me why?”

“Sure,” said I. “It’s because even a mule gets so dog-gone tired of its own mean nature that it wants a change. And when you hear a mule bawling like that, it’s just up and asking heaven for a second chance.”

Tug Murphy lay back again onto his blankets, slowly.

“Maybe you’re right,” says he. “I never knew a mule very well without beginning to pity it, finally. They’re just sons of torment, Joe.”

“They are,” said I. “And that reminds me of a story about the—”

“They might even make it thirty,” says the sheriff.

I saw that he was back on the question of the reward, again. I said nothing. I’d heard enough on that subject.

“But then again,” said the sheriff, “you take a mean man like President Ranger of that bank, and he’s as likely as not to say that I done no more than what I was paid by the county for doing.”

This time I put in my word.

“Yeah, as likely as not,” said I.

The sheriff grunted.

“It’s a cool quarter of a million,” said he. “They oughta by rights pay me ten per cent, if they got any heart.”

“Uh-hunh,” says I.

“And even if they make it only five per cent, that’s twelve thousand five hundred.”

“Uh-hunh,” says I.

“But they wouldn’t be short sports. They’d have to make it a round figure. Say, fifteen thousand.”

“Or ten,” says I.

“Yeah. Or even cut it down as far as ten,” says the sheriff. “You talk like a regular banker, Joe. I bet you’d do fine behind the rails of a bank, collecting interest, and things.”

“Uh-hunh,” says I.

“Well, that ought to be rock bottom,” says the sheriff. “And on ten thousand, a man could do a lot. There’s Pig Weller has set himself up with a pretty good layout, all that a man would ask to have; and his whole outfit, land, and stock, and all, it only set him back eight thousand.”

“He didn’t get much stock for that,” says I.

“No, but he part paid on ’em, and they’ll turn into hard cash for him.”

“Uh-hunh,” says I.

“The old woman, she’d like to settle down,” says he.

Then he sat up again.

“What’s the matter?” says I.

“That fool of a mule,” says he, “where’s it walking to? And it’s got the horses right along after it.”

“Well, maybe it smells good grass,” said I.

“They’re stepping right out,” says he. “And yet I hobbled ’em pretty short. They’re stepping right out, for hobbled stock—”

Suddenly he jumped up to his feet.

“By the eternal nation,” he says, soft as you please, so that it sent a chill down my spine, “them hobbles have been cut!”

That got me to my feet, too, and I was in time to see some figure—it looked small—jump on the back of the sheriff’s best mustang and start off at a trot, and then at a canter, with all the rest of the live stock on lead ropes behind, and the burro last of all pulling back hard on its line!

I HEARD the sheriff groan. Then he grabbed his rifle and started pumping bullets at the disappearing caravan of horses, and mules, and what not.

But he had no luck. You could tell beforehand that he would have no luck. The cause being that moonlight is the worst light in the world for shooting. Everything seems clear, but at a little distance, and no one in the world can judge the distances.

I knew that he would miss, and he did miss.

And I saw our transportation wander off into the distance.

“Indians!” I yelled. “And this is why people that steal horses are hanged.”

“Indians your foot,” said the sheriff, strangely calm. “It’s Chip. That’s what it is.”

“Chip?” I shouted. “Chip leave me stranded like this? Never in a thousand years!”

“Who does he like better?” said the sheriff. “You or Waters?”

“He may like Waters better,” said I, “but he’d never do a trick like this to me—not in the middle of the desert!”

“You don’t know him,” said the sheriff. “But I do. Because he’s Irish, and the Irish blood is all red and black. There ain’t any blue in it. I’m Irish, too. But we’ll win through to Freshwater Springs!”

You can imagine that we didn’t wait. If we had to hoof it through those shifting sands, that slid back six inches under every step, there was no sense in waiting for the sun to come up and broil us. It was better to start tired than to start hot.

We sifted down our packs to almost nothing. We just kept one rifle, some food, and the saddlebag that had the quarter of a million dollars. Then we started across the gloom and silver of the moonlit desert.

I can’t tell you how the loss of our horses had widened that desert. The place had seemed big enough, before, but now it seemed a lot bigger. I can tell you. It was multiplied by ten.

Off we went, and I listened to the sand gritting and sliding under my feet, and I listened to the sand gritting and sliding under the feet of the sheriff.

He was very calm about it. Now and then he would break out into a short speech, but mostly he saved his breath.

“About fifteen years in jail,” he said several times. “That’s about all that he’ll get. And I hope that they make him perspire from morning to night for fifteen years, the way that I’m doing now. I hope that they keep the whip on him. Dog-gone his miserable hide!”

I nodded.

I was very fond of Chip, but if he really were guilty of this business I hoped that he would get plenty of punishment, and not have to wait for a future life to receive it, either.

Well, we slogged along. I don’t know how many of you have walked across blow sand. I hope for your own sakes that not many have. It’s lighter than water and a good deal more slippery. There’s no way of planting your feet that gives a good purchase. The best way is to turn your toes out and your foot on a bias. That way, you get more to push against. Well, even at the best it’s a bad business. It’s wading, and slipping, and sliding. Every pound that you carry counts for ten, in blow sand.

Pretty soon, we talked no more, but just buckled down, and laid into the work, and set our teeth, and hoped that Chip, or the Indian or whoever had stolen our horses, might land in the hot place.

Then the sun came up.

It didn’t waste any time warming up. It just slugged us in the head with about ninety degrees for a beginning. The instant that it got its eye above the horizon mist, it was blazing hot, and it kept right on blazing. You have no idea how the desert sun starts its business with the first signal and keeps right on until it sinks. It shoots from the hip, without a waste motion, and it keeps on shooting, all day long.

Our canteens lasted until the middle of the morning. Then we made a halt in the lee side of some rocks, and the sheriff swallowed a couple of times to ease his throat, and he said:

“Well, we’ll make the Freshwater Springs, all right. But it’s going to be tough.”

He was right.

He generally was right, but particularly about this. We slogged along through that blow sand with the sun getting hotter and hotter. It seared through a man’s shirt and burned the shoulders. It blistered the rims of the ears. It scorched the end of the nose. Now and then I raised my heavy, broad-brimmed sombrero, and tried to get some air on my head in that way. But it was no good. It let the steam off, so to speak, but it didn’t let any air in.

Well, I went along and endured it. Once you’ve got used to desert travel, you can remember other times when it seemed eternal, and yet it ended, some time.

But the worst part about the Nevada deserts is that there’s often a blue pile of mountains off somewhere on the rim of the horizon telling you about cold running water, and shade under trees, and winds blowing, and all such things.

I dreamed of palaces of ice. And I could have eaten the whole dog-gone palace!

Then we hove over a rise, and the sheriff laughed in a horrible, soundless way, and he pointed and said:

“There’s the Freshwater Springs. Down there, where the rocks are shining!”

Well, suddenly my feet were light, and my heart was light, and I stepped along free and gay and bold and could almost have sung, except that my throat was hurting me too badly.

We stepped along pretty briskly on that stretch, and then as we came closer to the rocks, the sheriff he gives a queer, choked yell, and then he breaks into a run.

I watched him. I thought that the heat and the thirst had driven him a little crazy.

But then I saw something that made me start running, also. For those rocks didn’t look the way rocks should look. They seemed to have been turned every which way, and their pale bellies were turned to the sun.

I ran as hard as I could, but I couldn’t keep up with the sheriff. He was a heavy-built man, but that day he fairly had the foot of me; and when I came up, puffing, and groaning, he was standing with both hands spread out, as though he were making an explanation, silently, to some one who could understand silence.

Then I saw for myself.

Freshwater Springs had been blown up!

Yes, there were the rocks, as I have said, scattered about, and now one could see how they were scorched and blackened, here and there. But the main thing was that the water was gone—all gone!

The rim markings of the pool were there. The sand was still almost damp enough to chew, if you know what I mean. But the water was gone.

Some fiend had dropped a charge away down the throat of the springs and had blown it, and the flow of the water had been stopped.

What could one do? Well, the next prospector who happened along might drop down another charge of powder and blow it again, and then the water would likely start running. But now it was lost.

And we had no powder!

I looked at the sheriff, and the sheriff, he looked back at me. He grinned, and his smile was a bad thing to see.

“Chip!” said he.

“Not Chip,” said I. “Chip would never do such a thing. Not Chip! Chip’s a partner of mine.”

Said the sheriff: “Am I Irish?”

“Yes,” said I.

“Do I know the Irish?” said he.

“You ought to,” I admitted.

“Did I say that Irish blood was all red and black?” he asked me fiercely.

“You said that.”

“And no blue in it?”

“No,” said I.

“That’s Chip,” said the sheriff. “He’s all red and black. The red in him is the way that he loves his friend, Waters. And the black is the way that he feels about everybody else.”

I shook my head. “He’s only a kid,” said I. “He couldn’t do it. He couldn’t have the heart in him to do it.”

“Aye, he could,” said the sheriff. “He’s got an Irish heart!”

I listened to him talking, and it seemed to me that there must be some other answer, but still my mind turned back again and again to the same thought. It was Chip. He had the reason to want to plague the sheriff, and if he plagued me at the same time—well, what difference did it make?

Anger came into me like steel, and I gritted my teeth, and wished that I had the neck of that boy in my hands. I would give it a twisting that would end Chip’s days of mischief.

“Chip done it,” said the sheriff, over and over. “Chip went and done it. He never stopped to reckon the time when I was pretty easy on him. I mean the time that I pinched Waters and could’ve pinched Chip, too. But I didn’t. I didn’t want to send an Irish spark like that to the penitentiary. Well, this is the way that he pays me back.”

It was an interesting thing to hear the sheriff talk like that, slowly, quietly, with a voice rusted and grating with emotion, and thirst. I listened to him, and I watched the bulldog working in his face, and I almost forgot my own thirst, I was so keen to see what was in the sheriff’s mind.

Well, after a time we thought the thing over, and we talked it over in just a few words, because not many words were necessary. The nature of the deed stood up and looked us in the face.

We had to get from Freshwater Springs—the very name was a torture, now—to the next water hole. And that water hole was a good seventy miles away.

Seventy miles, and sand to trudge through! Seventy miles! We would have to go slogging all through this day, and all the night we would have to keep marching, and most of the following day. And, at the end of our march, we’d come to a few swallows of muddy alkali water, if we were lucky.

I wanted to lick my lips, but I didn’t. I just pressed them in a little, and made the saliva flow a bit.

We sat there in the scanty shadow of one of the overturned rocks, and we decided what direction we would have to take. I knew that country pretty well, and we picked out the valley where I knew of a water hole that was said never to go dry—perhaps.

Then we got up and buried the saddlebag, and started off.

WHEN I put the saddlebag in so casually, I meant it.

It didn’t matter to the sheriff, either. All that mattered to us was seventy miles of desert sand—and how were we going to last out? We both had been through the grind before. We knew the desert. We weren’t romantic about it. But a few touches of that dry, hot wind would simply soak up the blood from our bodies; and we’d die.

It wasn’t so much body, either. It was mind that the heat worked on. It was well enough for the sun to scorch the body, but it was a different thing to let the thought of it start to campaigning in the brain. That was what drove men crazy.

So you can believe me when I say that we put away a quarter of a million dollars under the broken rocks of Freshwater Springs and gave it not a thought. And we marched on without once looking back. The rifle was there with the saddlebag, too. We had no use for that weight. We carried with us some salt, and a little jerked beef; and the sheriff kept his hunting knife on, not that he wanted it, I dare say, but because he would have felt undressed and strange without its handle to fumble as we went along.

Two hundred and fifty thousand dollars lay there under the rocks, and we would have changed the whole sum, believe me, for a single runt of a mustang to ride by turns, and to hang onto, to help us forward over the terrible stretch that lay ahead.

We had only one thing to be glad of, and that was that we had company. I think, for my part, that if I had been alone I would simply have stretched out there in the shade of the rocks and waited for death. Or perhaps I could have helped it on the way a little. But with a companion, a man doesn’t give in. The last thing that remains to us, it appears, is pride and a sense of audience. The sheriff was my audience. I was his audience. And so we just headed away for the cleft in the distant mountains where I knew that water could be found.

I think that the most awful part of it was the knowledge that the hours would crawl away before us like a worm, and that always we would be looking at that picture of blue distance, and that always we would seem to be as far away as ever, and that even when the picture turned from blue to brown, we would still have a ghastly march ahead of us, and that even when we could see individual rocks and trees, still there would remain terrible miles before us.

The clear air would take care of that.

Yes, the moment would come when we would suck our own blood to ease the horrible pain in our cracking throats.

And we both knew all these things. And we both knew that it was touch and go for us. That was the reason that we wasted no breath in talk.

The sheriff simply cut the cord that tied my hands. And I felt no particular gratitude for the act. It might be I who would hang onto reason the longest and be able to slap him on the back at the right moment, and clear his own wits, or curse him into a greater manhood.

On the other hand, it might be he.

So we left the rocks, and we started our voyage, and we walked all the rest of that day.

I don’t want to dwell on it. I don’t want to recall the horror of that sun, or the way it laid its red-hot hand against the backs of our heads and fried the brains. I don’t want to think of that day, because it makes my throat dry and crack—the mere thought. Now I can go and fill a glass with ice and pour in enough water to fill the interstices, and drink that water, and fill up the ice again, and sip once more, and let the blessed cold of it trickle slowly down my throat. But still it seems that the thirst can never be taken out of me. The water famine has its claws in my vitals once more, and I burn with it, in imagination, almost as badly as I burned on that day.

Before night came, I knew that we couldn’t succeed.

Already my tongue was badly swollen, and my lips were cracking till the blood ran down my chin. It was a painful thing to have to move my eyes, because the balls of them seemed to be lined and set in sharp crystals of quartz.

But we marched on.

The sheriff must have known we were beaten, too. His case was worse than mine, because he was a larger and a grosser man, and I could tell by his staring look, long before sundown, that he was looking his death in the face. But, you see, he would not be the first to weaken, and neither would I.

There was the strange picture of two men walking straight on toward inevitable death and never speaking about it, because each of us wished to break down the pride of the other and force him to be the first to whine. Twenty times complaints came pouring up into my throat and twenty times I ate those complaints and said no word of them. And once—once only—I heard the sheriff curse, and his curse was a groan.

Now, it was about the sunset time, when the next part of that adventure started. I mean to say, the sun was lying on its side in the west as hot and terrible as ever, nearly, but its cheeks were swelling, and it was plain that before long we would have the dark. And even that thought was no comfort because, some time during the dark of that night, the knees would fail under one of us, and that man would sink, and the other would turn and give him one look, and then drop in turn because of the bitter comfort of dying beside a friend.

But, as this sunset began, and the sky was starting to redden in the west, I saw the sheriff pause sharply and stretch out his arm.

“It’s begun,” I said to myself. “The madness is at him, and eating his brain like a mouse nibbling at cheese. It’s started on him, and he’ll be raving, in another moment.”

But he stood there like a statue, just pointing, and saying nothing until I turned my eyes with pain in the same direction.

Then I saw it.

Animals of some sort were coming toward us, strung out in a long string, etched strongly against the background of the western light, and dyed and blackened by the contrast. And while I watched them, and saw the nodding heads of the horses, I groaned aloud with joy.

They were not wild horses. No, now I could see a rider upon the first of the lot, and I thought that that must be the luckiest man in the entire universe, because he was in this desert, but he had a horse beneath him.

Suppose he were thirsty. Suppose he ran out of water. Suppose he had to drink. Then he could cut the throat of one of his lead animals—mules or horses—and he could drink the blood. And what a delicious drink that seemed to me, at the time!

The sheriff dropped his arm.

“Chip!” said he.

It rather staggered me, that idea. I stared again—one small rider, with several horses or mules behind—yes, and at the tail of all, the little outline of the burro, pressed against the ground, as it were.

“It’s Chip,” I yelled, as though I had made the discovery first.

The sheriff grinned, and as he smiled, the blood ran down his face from his broken lips.

But he nodded, and side by side, we turned toward that procession. It was Chip, and after all, he cared for us enough to want to give us a hand.

We marched toward him. The sun sank in the west. All was red fire behind, when we came within shouting distance of that youngster. And we saw him wave an arm to make us halt.

We walked straight on. The wave of an arm could not stop us. Suddenly something struck the sand at my feet, and a shower of that sand was scattered over my legs. Then the clang of a rifle dinted on my ears.

He was shooting to make us halt!

Well, bullets have a persuasive power of their own, and we stood still.

Then I heard Chip’s voice, not raised and strained but easy and cool as you please.

“You want water, you fellows?”

Want water? The very sound of the word worked at my saliva glands and made my throat crack again, and widen in hope.