RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

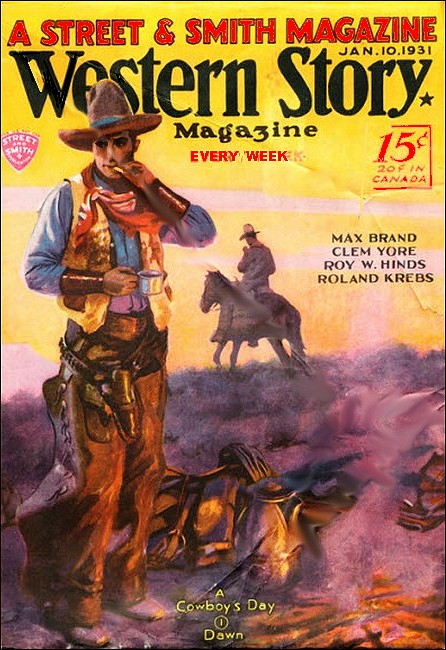

Western Story Magazine, January 10, 1931,

with "Chip and the Cactus Man"

IF he had had a quarter of an inch of rain a year, Newbold could have raised cattle in Hades. For that matter, we all felt that his range was a little worse than Hades; it averaged only a shade more than a quarter of an inch of rain most of the year.

What saved him, of course, was the western half of the range, where the westerlies piled up clouds at certain times of the year and gave that smaller section of his land a good drenching. When the grass petered out all to the east and south, we had to get the cows started through the teeth of the passes and work them over to the green section. They were a hump-backed lot, all gaunted up with thirst and the grass famine, before we got them to the western range, however. And after they hit the green feed they went at it so hard that a lot of them were sick at once, and a good number always died.

No wonder! Nobody but Newbold could have ranged cattle at all on the remainder of that mangy range. We used to say that he gave his cows a college course in gleaning, and that a Newbold yearling would gallop half a mile for a blade of grass and run three days for a drink. There wasn’t much exaggeration in the second remark, either.

Somebody with a mean nature, plus a sense of humor, gave Newbold his start by making him a donation of his first ledge of the range. That was when he was sixteen. That land raised nothing but coyotes and a few foxes, and even the foxes were out of luck in the district. A bear will dine on anything, from roots to grubs and wasps’ nests, but self-respecting grizzlies simply broke down and cried when they had a look at Newbold’s gift of land.

But Newbold didn’t cry.

He was raised with the silver spoon, at that. Old Man Newbold had made a fortune in lumber, another in cows, another in gold dust, and still another in land. But he used it all on high living and faro. He used to work up a faro system every year or so, and then he would go on a big campaign, but the faro always won. Take it by and large, faro always will. It beats the white men, and it beats the crooks.

So the old man died and left one son and heir; and that boy, who had been raised soft and high, was chucked out into the world with nothing much but hope to fill his poke. Then, as I was saying, an old friend of his father’s gave the kid a wedge of desert that was already overcrowded by a fox, a coyote, and half a dozen rabbits, all sinews and fur.

But Newbold took the gift with thanks. He started with about a cow and a half and a burro, by way of live stock. And when big outfits were driving back and forth across the range, and lost young cows and yearlings going across the boy’s sun-blasted land, he picked up those dying cattle for half the price of their hides, and then, as we all said, nursed them with pain and promises until they could walk.

I think that cows were afraid to die on Newbold’s hands; they had an idea that the earthly paradise was anywhere off his range, and they kept fighting and fixing their sad eyes on the future until they graduated and got to the butcher at last.

Yes, Newbold progressed so rapidly that when he was eighteen he fixed his eyes on more of that range. He took a trip clear to Chicago and walked in on the fellow who happened to own the rest of Hell-on-earth. When this man heard that Newbold wanted to buy, he looked him over and saw that he was all brown steel, like a well-oiled engine. He offered to rent him the range for about a dollar a year, but finally he sold it for something around a dollar an acre, which was sheer robbery, except for the green western valleys, which I have spoken of before.

So Newbold went back west again and got him some more batches of cows that had used up their first chance in life down to the last half-drop. And from year to year he walked his skeletons back and forth across his range, and lost a lot of them, but made a heap of money on the rest.

He took that range when he was sixteen. He expanded it when he was eighteen. And for fifteen years he raked in dollars off the rocks and blow-sands. In a good, fat country, I don’t think he would have done so well. He was one of those geniuses who know best how to make something out of nothing. He was a cactus among men.

At thirty-three, he looked forty-five. He was the hardest heart, and hardest driver, and the meanest boss in the world. He fed worse and paid less than any other outfit. But still he always managed to keep a crew together. In the first place, he was straight; in the second place, he treated himself worse than he treated his men; in the third place, he backed up his boys as though they were his blood brothers when they had a falling out with sheep-herders, or any other poachers; and in the fourth place, and, most important of all, any puncher who could say that he had lasted out a whole year with Newbold was sure to get a job wherever he cared to roll down his blankets and pick out a string.

The fourth reason was the one that brought me to his place. That, and because I had heard of him since I was a youngster, first as “the boy cattle king,” and secondly as “that hard case, Newbold.”

He was a hard case, all right. His only relaxation was a fight, and even in that line he didn’t get much relaxation after a time. He became too well known. Now and then somebody who wanted to make a reputation went up to the ranch and looked for trouble, but that man either turned up his toes on the spot or had to be shipped out for a long list of repairs.

It got so that Newbold would ride sixty miles to wrangle with a neighbor or to take up a remark that somebody else had said somebody else had heard about him. But even these long rides finally began to bring him in very short returns; and all that Newbold could do was to fight the weather, and the prices, and the railroads—three things that even Newbold couldn’t beat. Even so, he just about got a draw, as a rule.

I think it was because he was running out of trouble, except enough to kill five ordinary men, that he finally thought of raising hay in the western valleys of the range.

It was one of those paper schemes. You sit down with a map and draw a lot of lines. You fence in a lot of the best ground, and then you buy mowing machines and rakes, and you cut the crop, and cure it for hay, and you make a road through the passes, and when the eastern range is as bare as grandfather’s red head, then you have a lot of first-rate feed to stuff into the cows and pull them through until the next quarter-inch rain comes along and washes more mud and a little water into the tanks.

That was the scheme of our boss. A good, big scheme. And a scheme that might do wonders. The trouble was, in the first place, that fence building, and road making, and mowing machines, and two-horse rakes, cost money.

However, Newbold struck in on the scheme, and he did it in the true Newbold way. You would think that he would just sit down and write off an order to a big manufacturer of agricultural implements, and pretty soon we would go down to the railroad station and debark, a trainload of everything, covered with shining new blue, and red, and green paint.

But Newbold didn’t do that. He was ten miles too mean for that. First he got a one-legged machinist, and a seventy-year-old blacksmith, both of them willing to work for board and tobacco, so to speak. Then he put up a bow-legged shed, and he went away from the ranch on a three weeks’ trip.

All through the West, now and again a big farmer or rancher dies and his family splits up, and the first thing that is done is to sell off all the implements. As soon as the paint is rubbed off a gang plow or a mowing machine, it’s old. And as soon as it’s old, it’s not wanted. It may have been worked six months or sixteen years. That doesn’t matter. It’s simply old. I’ve seen a hundred-and-twenty-five-dollar mowing machine sell for five dollars, and a forty-dollar subsoil plow sell for one dollar, and a seventy-five-dollar running gear for a wagon auction off for seventy-five cents, and a five-hundred-pound heap of iron junk—chains, hammer-heads, haimes, plowshares—knocked down for a dollar and a quarter. Even junk dealers are not interested when it comes to bidding in on farm wreckage.

Well, Newbold was not proud, in that way. He went out and collected. He attended half a dozen sales, and first of all, up came a forge and a lot of blacksmith’s tools, and that sort of thing. And then we got an order to break mustangs to collar and harness; and we went down to the station and began to haul junk forty miles overland to the ranch. It was a long job, and a mean one, and those mustangs could kick off their harness faster than school kids can shed their clothes on the rim of the swimming pool.

But there was the whole mass and heap of stuff, at last. And first of all, he set to work at the forge under the tutelage of the blacksmith of seventy years; and the more intelligent of us—I was not one—were put under the one-legged machinist. He and the blacksmith, do you see, were to supply the brains, and we punchers were the hand power! It was a mean scheme, but then, Newbold was always mean. It was a cheap scheme, but Newbold was always cheap.

We worked for weeks straightening the knock-knees of wagons that had developed flat feet and rheumatism a generation before. We patched harness with secondhand rivets, rawhide, and baling wire. We took out the mysterious insides of mowing machines, and operated, and put them back again, praying all together. We unrolled miles of knotted, tangled, spliced, and rotten secondhand barbed wire. And a roll of barbed wire can play as many tricks as an outlaw mustang, and buck as high, and hit as hard, and bite as deep. Besides, it never gets tired.

But, to make it short, finally we fenced, and plowed, and sowed, and cut, and raked, and windrowed, that land and the hay crop from it.

And then the boss saw that we could never haul that hay in the loose clear across the passes over the so-called road that he had made. He had to get a machine and bale it.

And that was where the trouble started.

WELL, we got a fourth-hand device called a hay press. The name of it was Little Giant.

But it was misnamed. It wasn’t little. It was a full-grown giant when it came to making trouble. It had to be a giant, because it succeeded where everything else had failed.

Newbold had not really minded the stretch of trouble that he called a cow range. He liked it. The harder the fight, the more he was pleased; the longer it lasted, the better grew his second wind. Climate or no climate, rain or no rain, prices or no prices, he raised cows, he made men herd them, and he coined money.

And that’s why I saw that the hay press was a real giant, because, single-handed, it licked Newbold. It put him on his back. And he was a new man when it got through with him.

I never quite understood the workings of that machine. When he got it, it looked like a cross between a traveling crane and a moving van. It was these things, and something more. It had all the faults of everything, and none of the virtues. It broke the heart of the machinist, and it nearly killed the poor old blacksmith. I shall never forget how he used to sit with his head in one hand, and a broken piece of iron fixture in the other, too tired to swear, and too worried to sleep.

I remember right well the day that we finally hauled the hay press through the worst of the pass, having pried and prayed it over jutting rocks, through tight squeezes, mile after mile. We had chucked stones under the wheels in time to keep it from lurching forward down a slope and crushing the mustangs which hauled it. We had thrown a log under it in time to keep the obstinate fool of a thing from running backward into a ravine. I remember the day for these reasons, and because that was when a pinto beast working in the swing clipped me on the point of the hip with a well-aimed kick just as I was jumping out of range; but most of all, I remember it because that evening a man rode into our camp and sat down to eat with the boys.

He was Dug Waters, whom most people in those days called “White Water,” for a lot of obvious reasons. Mostly because, here and there, he had made as much noise and done as much damage as a river at the flood. He was a tall, gentle-looking man with a good deal of Adam’s apple, and an embarrassed smile. He had a way of crowding into corners and seeming to beg every one not to notice him.

But the boss noticed him, you can bet.

That fellow Newbold always had a good look at any stranger who sat down to eat his meat in our camp. As I said before, it was the worst chuck that ever was put before cow-punchers, and Heaven knows that cow-punchers never got much of the cream, no matter where they hung their bridles and tried to call home. But Newbold could watch a penny in the shape of sour dough as closely as a jeweler could watch a fine diamond.

At the table was where we liked him least.

He hauled up to where Waters was sitting and asked him his name and business, and when he found out that it was White Water himself, the boss almost choked. He told Waters to start for the sky line as soon as possible, and that the shortest road would probably be the smoothest. He said that he had never turned an honest man from his door, but that he would walk ten miles and swim a river to take the hide of a skunk.

Now, our boss was a known man, but so was Waters, for that matter; and the moment we heard his name and saw how quiet he was, we knew that he was really a dangerous fighter. I’ve never seen it fail. A fellow of many words never has so many bullets in his magazine. The quiet fellows who seem to think their way from word to word are the ones who wreck a saloon when the time comes, and shoot the tar out of a whole sheriff’s posse when they’re pursued.

Now, White Water was exactly that sort of a fellow, to judge by the look of him, and to listen to his reputation; but he didn’t pull a gun on Newbold. Yet I’ve never seen more cold poison than there was in the eye that he turned on the boss.

Finally he said:

“Newbold, I’m a sick man. I’m bound on a long journey, and I haven’t eaten a morsel for two days. I’ll tell you one thing more. I’m not begging on my own account, altogether. I’d see you hanged before I’d do that. But I’m asking you to let me sit here and eat a square meal. I haven’t a penny to pay you, but I’ll give you the bridle off my gelding, yonder. I can ride him just as well with a halter.”

We all watched the boss pretty carefully at this. And I think that almost any other man in the world would have thrown up his hands when he heard and saw the straightness with which White Water was speaking. But Newbold was all chilled steel. He was the stuff that they put in the nose of armor-piercing shells.

“Your bridle and you be danged together,” he said. “Get out of this camp before I throw you out! You’re a thug, and a thief, and a gunman, and I hate your breed. If you’re sick, you’re not as sick as I’d like to make you. I’d like to see you and your whole breed drop and the buzzards start on you before your eyes were dark. Now, start along before I use my hands on you!”

I thought that it would be guns, then, and a mighty neat fight, because it made no difference to the boss. Perhaps he preferred fists, but he was just as much at home with knives, or guns, or clubs, even, for that matter. It was a sight to see him there with the red light shaking from the fire over his long, lean, loose-coupled body.

But Dug Waters only looked up at him for a moment as though he were seeing a game bird, away off in the sky. Then he surprised us a good deal by saying:

“You don’t have to throw me out. I’ll go.”

With that he got up and left us, and the amazing part of it was that not one of us, in speaking of the thing afterward, thought that Waters was yellow. We all agreed that he must have had something on his mind. Pete Bramble said that he saw Waters stagger as he raised his foot to the stirrup to go off. And every one of us agreed that he had told the truth and was a sick man. He had the white look of a fellow with very little blood in his body—very little good blood, at least.

And Pete Bramble, after the boss had rolled into his blankets, looked around him at the silent circle of us and said:

“That’s gunna bring us bad luck. That’s going too far. When a man’s sick—” He stopped and puffed at his pipe.

The cook was standing there in his shirt sleeves, the fire shining on his greasy, red arms.

“When a man’s sick?” he echoed. “No, but when he’s hungry! Ay, or even a dog, when it’s gaunted all up!”

I think he was the worst cook in the world, but I loved him for saying that. We all did. For two or three days hardly a man cursed him for the way he made the coffee or burned the beans.

The next day we got the hay press down to its first location and set her up. It’s a hard thing to describe a hay press. In the first place, it’s a job I don’t like. The less I have to think about them, the better pleased I am. In the second place, I never understood them, and I never wanted to.

But I can say that this thing that turned big hay into small, so to speak, was a long box set upon one end, with a beater in it that worked up and down on long irons. The power that worked it came from four sweating mustangs, that scratched their way around and around on a circle, hitched to a beam. Halfway around the circle they were lugging to pull the beater up; the other half they were lugging to jam the feed down. And it was run, run, run for them except when the bale was made, and then the power driver yelled “Bale!” and dropped an anchor board that held the power beam in place until the bale was tied with wire.

The first thing that we did was to start out a fleet of four Jackson bucks. For the benefit of punchers who never saw a Jackson buck, I’ll say that it’s a thing with a lot of iron-shod and pointed wooden spears that stick out in front. Two horses work behind this line of spears with a wooden, open bulwark in front of them, and behind them sits the driver on a seat that has a single plowwheel under it.

It was my job, at first, to drive one of those Jackson bucks. I admired the contraption a good deal, right at first, but I used up my admiration plenty before the day was an hour old. The trick was to start out with the teeth of the machine hoisted, and while running empty, like that, the clumsy brute was sure to start sliding on a down slope where there was no down slope to see, or zigzagging over bumps where there were no bumps to find. And I ask any cow-puncher to imagine what a pair of broncos only half broke to the saddle and a quarter broke to harness would do with that sort of a stall on wheels weaving around them.

They kicked, and bucked, and threw themselves down, and reared to throw themselves backward, and then they started to run away. But the cards were stacked against those broncs. They were tied in front, and they were tied behind, and they were framed in on both sides, and when they tried to bolt, I just lowered the spears into the ground, and after they had plowed an acre or so, they admitted that they were beat.

So was I. I was kind of chafed a little, to tell the truth. I thought that riding for years in a saddle had given me an outside lining as tough as leather, but I was all wrong. That iron seat on top of that jolting, jouncing, jarring plowwheel found all sorts of new and tender places that I didn’t know were on the map.

Finally, the broncs were convinced that it was no good, so I started their work, which was to pick up as many shocks of hay as the buck would hold without spilling and shove them up to the back end of the hay press. The broncs would ram the load home well enough, but when it came to backing up, they couldn’t understand. They simply balked. Pete Bramble lighted matches and burned off their chin whiskers before it dawned on them that there were two ways of going, and one of them was back.

But still, it was a hard job. Between pulling my arms out of joint to back my ornery team of nags, and trying to steer that danged sidewheeling invention, and being bumped like a hiccupping rubber ball until my heart and stomach changed places and my liver and lungs got scrambled together, I was ready to quit by noon.

So I went up to the boss to tell him my idea, and there I had my first sight of the kid.

I have to take a new breath before I start talking about him.

THIS kid was about fifteen, I should say, very big for his age, and with a pair of smooth shoulders—the sort you see in a well-made mule. He looked more, but you could see that the bull was only beginning to appear in his neck and the mastiff in his jaw, and the mischief in his eye. His face was covered with bright-red freckles.

“They’re the sparks and the coals of fire that come out of the top of his head,” said Pete Bramble, one day.

For his hair was just the color of fire—red fire. This pug-nosed boy was sitting on a rock chewing a straw and looking like a simpleton, which is a talent that no grown man can divide with a fifteen-year-old brat. He had on about half a hat, with his red hair burning up through the holes in the roof. He had on a shirt that was minus a collar and one sleeve. His trousers were a sawed-off pair that once had fitted a man, and a big man at that. His feet were bare, and so were his calves, with white marks on them where the thorns had scratched.

Take him all in all, he looked like a young mountain lion with the fur peeled off and the hide tanned.

I looked at this young limb for a while, and then I sashayed up to the boss. He gave me the nearest relation to a smile that could be found in his house—about a fifth cousin, say.

“How is things, Joe?” says he.

“Kind of monotonous,” said I.

“Monotonous?” says he.

“Well, chief,” said I, “I came up and hunted for your shindig because I heard that there was some action to be found around your place.”

“Why, Joe,” said he, “I’ve always aimed to keep the boys amused and with enough to do so they won’t have to be rocked to sleep at night. I used to keep minstrels and such to soothe them down, but then I decided that I’d have to look up more for them to do. Matter of fact, I haven’t had no complaint like yours since I can remember.”

“That’s a funny thing,” said I, “and I’ll bet you ain’t been keeping your ear peeled close to the ground. Well, it hasn’t been so bad, mostly. Breaking in ten-twelve trained outlaws that you call range ponies every year was one pleasin’ feature that we all looked forward to, especially me.”

“I always guessed that you did, Joe,” says the boss. “You look so plumb graceful in the air.”

“There was other good features, too,” says I. “Like drinking tank water when the wriggles have to be strained out of it and vinegar mixed in; and eating beans twenty-one times a week; and exercising our jaws like lawyers on beef that we never could convince. And the ship’s biscuit was entertainin’, too, because it was a lot of fun to rap a chunk of it on the edge of the table and see the weevils come out and take notice who was callin’ at the front door of their old home.”

“Why, Joe,” said he, “it seems that I’ve been running a regular vaudeville show to keep you boys amused. I didn’t know that I was laying myself out to do that.”

“A regular college, too,” says I. “Couple of years up here would make a man pretty handy with some of the dead languages, because it’s a cinch that your cows don’t understand no living tongue. There’s some medical trainin’, too, because anybody that can nurse your yearlings through one of these winters ought to be able to set up a ‘first-rate’ practice giving the rich and the old and the feeble another ten years of life.”

“That’s an angle I never thought of,” said he. “I guess that I ought to start to charge admission, and here I’ve been all the time paying out regular wages.”

“It’s been a terrible mistake,” says I. “The boys all been wanting to speak about it, but you know—some fellows, they break right down when they find that they can’t give away a lot of their dough. We all thought that you must be one of that kind.”

“I see how it is,” says he, a lot more patient than I ever expected him to be. “My mistake is being too big-hearted and generous all the time.”

“I hate to tell you,” says I. “I hate to complain, but that’s the truth. Look at the way you put up a roof over the bunk house with the roof all patterned with holes, like an open-work shirt, so’s we could see the stars while we were lying in the bunks. A plain cow-puncher, he don’t expect that much care, and thought and trouble on the part of his boss. Though I must admit that it was handy to know when it was raining, and we could always tell when the cows was likely to freeze to death by the way we felt in the bunk house.”

“I see it all, now,” says he. “I’ve just been too kind!”

“Chief,” says I, “I’m a humble man, and I don’t like to complain, but the hard truth has gotta come out. We’re a rough lot, and a thick-skinned lot, and we have to be treated that way. Still, for the sake of education, and all that, I’ve stuck along on the job, but today is too much. There ain’t enough to do on that Jackson Creek to keep me awake.”

“Joe,” says he, “you fair make my heart bleed. Sitting there on that soft iron seat has sort of culled you.”

“Yes,” says I, feeling my way along, “about half a yard of hide has been culled right off me. And a fellow like me that has been used to riding thoroughbreds out of Thunder and sired by Lightning, you can’t expect him to have his hands full with nothing but a pair of those pets that I’ve been driving all morning.”

“They’ve been too well taught,” said he. “I can see that.”

“Yes, chief,” says I, “the fact is that it ain’t hardly possible to keep them from reciting their lessons all day long. They’ve been marking up a hundred per cent on me all the time!”

“It’s hard to bear,” says he.

“Yes,” says I. “I’m already limping a little. But I’ve been waiting and hoping that I would have something to do to keep my hands full and my mind occupied, but the only other thing that I’ve had has been a three-wheeled cartoon of a wagon that already knows a lot more than I’ll ever learn. It can find its way where I never would guess that there is one. That’s what I call a college-graduate wagon.”

“I’ve been admiring it myself,” said he. “And what’s the conclusion that you’re drifting all these ideas toward, Joe?”

“It’s a sad thing, chief,” says I, “but I’m going to vamose. I’m afraid that you’ve got the wrong kind of man in me. You oughta fill up your bunch with recruits from the old folks’ home, or a hospital, or something like that; the sort of people that wouldn’t ask to be more than just mildly occupied and amused for about twenty hours a day, the way I’ve been. You take old people, and they get childish again, and they don’t mind lying down and sleeping right through the whole of four or five hours a night.”

“Old son,” says he, “I see that you’re giving me the best advice in the world. I thank you, and I’m mighty grateful to you. But I can’t help suggesting that maybe I could shift your berth and give you another job.”

“What job?” said I. “What sort of a job on this Christmas Eve knitting party?”

“Why, there’s the forking and feeding job,” said he. “Pete Bramble has been pretty nearly going to sleep on his feet, over there with the Jackson fork. Why not change with him?”

“I dunno that Pete would want to change,” said I.

“I’ve got kind of an idea,” says he, “that Pete would actually change with anybody. Even the wire cutter, over yonder.”

This wire-cutting was a job that I hadn’t looked into much, so far, but I could hear a good deal from this fellow who was running the outfit there; sometimes the sound of him half a mile away went into my mustang like a whip and made him jump.

Here speaks up the red-headed kid.

“That wire-cutting job was made for me,” says he.

The boss looks him over.

“Ain’t you too old for that kind of active work?” says he.

“I’m getting kind of childish again,” says the kid. “I just want to stand around and play with toys like that all day.”

“You know all about hay presses, I guess?” says the boss.

“No, not all about ’em,” says the boy. “I’ve forgot a lot. But I used to build ’em. That’s all.”

“D’you think,” says the boss, “that you could cut as many wires in three hours as we can use in one?”

“I think,” says the kid, “that I could cut as many wires in one hour as you could use in three.”

“I guess you could,” says the boss, with a sneer. “I guess you could do that. I guess you’re a regular dollar-a-day man, ain’t you?”

“You know the way the saying goes?” said the kid. “Put up or shut up!”

Newbold jumped a little. Then he remembered that he was only talking to a kid. He looked at that boy again, up and down.

“Kid,” said he, “go over and do your stuff. Tell Bosh Miller that he can step down from that wire stretcher.”

The boy still sat where he was and chewed on the straw and twisted it slowly from one side of his mouth to the other.

“At a dollar per?” said he.

“If you can turn out as many wires as we use. Yes!” says the boss. “But if you spoil more than two of those wires—What’s your name?”

“Chip,” says the boy.

“If you spoil more than two of those wires, I’ll make you less than a sliver,” said the boss.

But he was talking to the dust that lad made as he streaked it for the wire cutter.

“Now, Joe, what are you saying?” remarks the boss to me.

“Well,” I said, “if Pete Bramble is chump enough to want to change jobs with me, I suppose that I’m chump enough to want to stay on and see how the thing turns out. That kid’s a whale!”

So I sauntered over to the stack and asked Pete if he wanted to change to my job.

He came blinking to me through a cloud of dust. He took me by both shoulders.

“Boy,” said he, “d’you mean it?”

“Sure,” says I.

He said not a word. He simply turned and climbed for the spot where my buck was standing. I looked down at my shoulders. There was a stain of blood on each of them.

IT’S a strange fish that can swim out of water; and the trouble with the whole business was that while Newbold knew all about cows, he did not know all about hay presses. Not half! He had a theory, and theories have wrecked greater men than Newbold.

A theory is the sort of thing that takes ten dollars, and sells on a margin when the market is climbing, and pyramids all the way, and makes three hundred and twenty dollars the first week, and ten thousand the second, and three hundred and twenty thousand the third, and ten million the fourth, and three hundred and twenty million the fifth, and ten billion the sixth—and there you are!

The seventh week that theory has the multimillionaires and all that small-time crowd asking for introductions; and the eighth week they beg for jobs, and the authorities vote a medal to the Napoleon of finance who kindly didn’t take up the whole of Wall Street and the rest of the country into the bargain.

Right at the beginning, Newbold showed us his theory.

He says:

“The shorthorn who sells me this machine, he says that it bales forty-five tons a day, and averages forty, because you gotta waste a little time taking it down, and moving it, and setting it up again. Now, we’ll allow five tons a day of lying to that crook. Still, we’ve got an average of thirty-five tons a day. We’ve cut three thousand acres, and we ought to bale twenty-five hundred or three thousand tons; and we ought to do that in ninety days. Now, ninety days is a lot of time, but so is three thousand tons a lot of feed. It ought to feed five thousand weak head of cows for a hundred days of the worst winter or the worst summer pickings. You see what that would mean to us.”

He always put it that way. He was always talking as though we were a company in which he was no more than the executive officer, say.

This same fellow who sold him the machine had said that the right pay was eighteen cents a ton to the bale roller, seventeen cents a ton to the feeders, and fourteen cents to the power driver.

But the chief did not remember that much of the talk. Only later we found out. What the chief offered us was just half of the right rates. However, even that looked pretty fat to us.

You take eight cents a ton, say, for forty tons a day, and you’ve got three dollars and twenty cents of any man’s money. And that makes close onto a hundred a month if you don’t knock off for Sundays.

And would we knock off? We would not! We lay around in our bunks, that first night, and we bought ourselves new saddles, and picked up thoroughbreds for a song, and won the Kentucky Derby with them, and took trips to New York and Cuba, and just raised heck in general.

Even the kid had done his share, and more than his share. He had hopped around from one end of that machine to the other and actually cut a lot more wires than the machine had managed to use up. He kept the wire fairly jumping off the coil, and the head-twister warm, he hummed it around so fast. We used a big wire for the central part of the bale, and a smaller wire for the ends. He could make the thinner variety fairly hop off the machine of its own volition. The bigger kind he had to strain over, bracing his weight to get down the stretching lever. But he never said no, and his production was steady all afternoon.

At the end of the day he goes up to the chief as fresh as paint and says:

“You gotta be congratulated on having one first-class man, Newbold.”

“Which man is that?” asks Newbold.

“Me,” says the kid. “If you don’t believe it, look at that!”

And he pointed back to a fine little stack of wires which he had cut and laid out. Newbold usually had a word when he wanted one, but this time he was plainly beat. He had to turn around and walk off, and that kid got on at a steady job with a man-sized salary of a dollar a day, which was real pay, in those days.

But I have to leave the kid, for a time, and get back to what was happening to the hay press.

The job of forking from the stack looked all right, and it sounded all right. All you had to do was to grab that three-cornered Jackson fork and plant it in a wad of hay. Then you yelled “Hey!” and the derrick driver started up his horse and jerked that load up into the air. And when it was dangling over the feed platform, you pulled the trip line and the load dumped down where the feeder could get at it. It looked easy. You seemed to be standing around a lot of the time, doing nothing.

But it didn’t turn out so easy.

For a starter, the fork weighed forty pounds, and all those pounds were put in the worst places. There were four long, curved teeth, needle-pointed, and always trying to get at your legs with a down-drop of a side flip, or some other dodge. And the trip iron had a sharp edge and was specially designed to clamp down over your fingers.

Then there was an art in using that fork. On the one hand, you had to dodge the spears of bucks as they came steaming in with all the push of two-mustang power behind them. And then as you side-stepped, you heard the feeder screeching at you for more hay. But you had to put in the fork just so. If you didn’t use the fork so that it divided the big, snarled masses a little, the feeder had to break his back muscling it apart. And if you tried to help the feeder by sending up small forkfuls, you half killed the derrick horse, which had to back up, all the time; and, in addition, you starved the feeder you were trying to help. Add to all this that you worked in a cloud of thick dust and chaff that filled your neck, and your throat, and your eyes, and it makes a pretty picture. But not strong enough for the fact. Nothing is as strong as the facts about a hay press, no matter how words are put together.

Well, I got through that afternoon, and when I came to the end of the working day—which was about dark, and long after sunset—I was almost too tired to wash my hands.

Then I waddled into the cook house along with the rest, and while I was looking at the greasy flapjack and sowbelly which the cook called our supper, and trying to make a start in eating, in came the chief, with hay burs sticking out of his hair and chaff down his back, stuck to his flannel shirt.

He had been adding up the tags of the bale roller, and he was pretty sour.

Then he said: “Nineteen goldarned tons!”

“Nineteen tearin’ wild cats!” said I.

The chief sat down at his plate, and looked at the flapjacks, and turned his head, and opened his mouth to say something to that red-armed clown of a cook. But he seemed to remember in time that he was the man who bought the food the poor cook had to eat, and that stopped his mouth for him a little.

Nineteen tons!

It was right. He showed us the books, and nobody would believe, and everybody took a look. Our bales were averaging about a hundred and eighty pounds, and we had only turned out a little more than two hundred of them. The feeders swore that they had pitched at least a thousand tons of blankety-blank hay down the throat of the what-not press; and the bale roller said they lied like something else, because he, personally, had taken out at least two thousand tons, and had tied, tagged, and rolled, and piled it.

Just then up speaks the kid.

Those greasy flapjacks didn’t bother him a bit. He ate them as though they were sponge cake and the sowbelly was honey. And he floated down his food with the alkali solution which our cook called coffee.

Says the kid:

“You know how it is, boys. You gotta learn. If I was up there on that feeding platform, I’d show you how to build your first feed big, and then taper them off so’s the last one is just a kick of your foot to knock some chaff down the throat of the old lady.”

We all looked at him. For my part I wanted to throttle him. The old man says:

“You know, do you?”

“Sure I know!” says the kid. “I used to build these here machines. You might say I invented ’em.”

“Well,” said the chief, “tomorrow morning you’re gunna climb up there onto the platform and show us. And you ain’t going to come down till noon.”

“Aw, that’s all right,” says the kid.

But he looked a little startled.

We dropped the beater in that mankiller at four sharp in the morning, and sure enough, there was the kid up there, with a pitchfork taller than his head.

And when he had said that he knew, he was right! You could drown him with a forkload of hay that crammed the platform to the far corners, but somehow or other he would manage to clear the feed table, and when it raised its ugly long lower jaw, sure enough there was a full bite for its long, square throat to swallow.

He built the first feed high and thick, and sloped it off, and packed it on top; and when the beater rose to the top of its height, he gave the upper layers of the feed a shove with the fork and started the load sliding even before the table rose. And so he poked a starter that nearly choked the press and got the bale well started.

And he could pick to pieces a tangle of hay that looked like a trail problem built up out of barbed wire. And even when the feed floor looked as bare as the flat of your hand, he seemed able to pick out another feed for the making bale out of the corners, here and there. But, all the time, he was riding me, out there on the stack, and calling down to me to find out if I was asleep, and how long had I been off baby food, and wasn’t I only part of a man, and when was the rest of the sandwich coming?

He not only had tongue for me, but he used to stir up the derrick driver, too. That driver was an Irishman by the name of Clive Rooney, and once Rooney started to climb up to the feeding platform and take the boy apart; but the kid stood right there and dared him to come on and told him he would straighten his crooked jaw for him and knock a whole vocabulary down his throat.

This line of talk cleared Rooney’s head a little, and he remembered that he was dealing with a mere kid. So he went back to his single-tree and derrick horse; but with every trip that the horse made out and back, Rooney gave one black look at the kid up there on the table.

It wasn’t Rooney alone, or I, that tasted the boy’s tongue. Sometimes he leaned around the corner of the press and asked the power driver if he had a team of prairie rabbits, or were they just burros; and he got that fellow to raging and throwing the whip into the ponies.

And still the brat had time to lean over the edge of the table and tell the bale roller a few things, and ask him if he thought he was rolling dice, and if he hoped to bale more than he could eat, and who had told him he was old enough to leave home.

He even had a few words for the drivers of the bucks, and the squeak of his voice cut clear and high through all the clangor of the press, and the cursing and shouting of the men.

After a while, he stopped bothering me. I guess he saw that I wasn’t to be made angry. And the fact is that I was too interested in watching his tactics to lose my temper. For he was playing the gadfly and driving the whole set of us, grown men though we were. He wanted us to bale hay, and he was making us do it.

Also, I could not help wondering how long he would last. He could not keep up the pace till noon, I knew. It was very plain that Chip knew all about feeding, and that he knew all the art of handling a pitchfork—for it is an art—but in spite of his craft, and his strength beyond his years, and his wild spirit, he simply could not stand there in the flying dust with the temperature a hundred in the shade—Heaven knows what it was in the sun fire and hay smoke where he was working—and push so many tons into the feed box forever.

We worked from four to six. Then we had breakfast. At breakfast, the kid was as gay as a lark, and taunting all of us; at ten o’clock we had a lunch of stewed prunes, bread, and coffee. The kid was still pretty chipper, but not quite so gay. He didn’t come down from the platform. He simply sang out:

“What’s the matter? You boys think you’re all at school and are getting paid for your recess time?”

He didn’t come down. He just disappeared, and I knew that he had flopped down flat on the table to rest there, in spite of the beating of the sun.

I finished off my lunch before the rest and sneaked a cup of coffee up to the platform. He was dead to the world, his eyes closed, his mouth hanging open. I shook him by the shoulder, and he got up with a start.

He gave me one hard look, tossed off the coffee, handed the cup back to me, and said not a word. He just got up and grabbed his pitchfork again.

I went back to the cook house and threw in the cup.

I said: “You’d best call down the kid from the feed table, chief. Or he’ll kill himself before noon.”

“Let him kill himself, then!” says the boss, and Rooney and a couple more chimed in with the same idea.

So I went back to watch, and to worry. For I began to guess that I’d said more than I knew, and come closer to the truth.

BELIEVE it or not, between four in the morning and eleven, that lad shifted fourteen tons from the feeding table into the feed box.

A whisper of this went around, and even the hard hands on that crew wanted to see the kid let off. Marvel or no marvel, of course he couldn’t keep on at that rate. Not at fifteen years of age. Only, I want to repeat that he didn’t look quite as young as fifteen. I want to say that for us all. We knew that we were doing something bad; we didn’t know really how bad.

But when eleven o’clock came and the boy was still at work up there on the platform, I was outright worried.

He had stopped all of his pestering talk, by this time. Through the rifts of the dust-smoke, I could see his face set and lined like the face of an old man. He was taking his punishment and never making a murmur. I don’t suppose it had occurred to him that there could be a man in the world like our chief, with a mind as small as an arrowhead, and a heart as hard!

The sun went higher, and kept pouring down a billion tons of yellow-white, scalding sunshine. We changed the power horses every hour. We changed the bale rollers every two hours. But the kid was still up there in the swelter of that furnace, never ready to say die!

Poor Chip!

Then Fate came along and offered him an ace from the bottom of the deck.

I mean, Miss Marian Wray came cantering up on her best saddle horse. It was a good deal of a surprise, though the Wray place was no more than ten miles away, which couldn’t be called any distance at all. But you wouldn’t expect Marian Wray to be that far away from home—not hardly with a company of troops for an escort, to say nothing of being all by herself.

For she was the real silver spoon, Back Bay, how d’you do aristocrat. She made me pretty sick, the way that she went around with her chin in the air.

I don’t mean to say that she snubbed anybody. She was the opposite to that. She was always friendly, and never let anybody go by without saying a few words, and the boys were crazy about her. But for my part, I never liked a peaches-and-cream, picture-book blonde. I never liked them a bit, and I liked Miss Marian Wray the least of the lot, with her democratic manner.

She even used to go to the dances, now and then. But she never stayed more than thirty-one minutes. Thirty minutes to stand around and admire the decorations, and say that things were “too sweet,” and the decoration committee had sure outdone itself, and that sort of rot. And then for one minute she slid out onto the floor with “Tex” Brennan, or somebody like that, that knew how to step, and made all the rest of the girls look like zero minus.

The funny thing about it was that the other girls didn’t seem to see through it, either. And the whole dang countryside, when you mentioned Marian Wray, just broke down and gibbered, and practically wrung its hands over her, and the women were as bad as the men. I suppose that they thought she was so rich and lovely and beautiful and everything that’s to be desired that there was no use in even envying her.

She was all dressed up like a regular range girl, with a broad-brimmed hat and a loose blouse, and divided skirts, and the look of her blowing along in the wind of the gallop was enough, I have to confess, to make a fellow’s heart jump.

But when she came up close, she was a lot more Back Bay than range. She had a tailored and a manicured look, as though three maids had been working all morning to turn her out like this.

Even the boss was staggered a little by the arrival of the girl. All the other men were hanging out their tongues, they were so anxious to hear two words spoken by this queen of the May. And even the chief almost took a few minutes off.

I say “almost,” but not quite. He just used the interval while the power horses were being changed, to chat with her, and all those grown-up fools of men craned their necks at that girl, and admired her, and grinned at her, and looked blushing and stupid, and ready to drop dead if she ever said the word.

“I see that you’re a great natural innovator, Mr. Newbold,” she said.

“Oh, I had a little idea. That’s all,” says Newbold.

And he grinned at her, too, wide and simple as any of the rest.

I bit off a hunk of tobacco from the corner of my plug, and while I worked it into a comfortable spot in the hollow of my face, and felt the cheek muscles pulling soft and easy over the point of the load, I looked that girl over and wondered a little at what soft-heads we men are. Because most days she would have hit me just as hard as she always hit all the rest. But that day I was too worried about the boy, and the perspiration in my eyes and the chaff down my neck. I couldn’t have been romantic for a thousand dollars a minute, paid in advance.

I just looked that girl over and said to myself: “Bunk! Give me something with a commoner look, because you’ll wear old sooner than any of the rest.”

She was going around and admiring everything. It was the first time she ever had seen a hay press in action. I heard her telling the power driver how terribly brave he must be to be out there behind those dashing, crashing horses, because suppose the beam should break, what would happen to him when it kicked back?

And she said to the bale roller how could anybody really do so many things at once, and wasn’t it wonderful how the human hand could work as if an independent brain were operating in it. Then she came back and gave me a look and she said what a frightful peril I was in, handling those four sharp, crooked, lancelike things. She called me Joe, too, because that was her idea. Look at Napoleon. He knew the name of all the men in his army, didn’t he?

Well, that was her trick. So dog-gone queenly that the meanest of her subjects was good enough to get a glad eye from her.

“You bet your boots, if you’re wearing boots,” said I, “that it’s a frightful peril—”

And I was about to add something else, when the dust cloud blew away from the feed platform and she saw the white face of the kid just as he sank his pitchfork into a wad of hay bigger than himself, a good deal.

“Great heavens, Mr. Newbold,” she sings out, with something in her voice that sent the pickled chills even up my back, “do you employ children—at cut wages?”

Did he employ children!

I thought that Newbold wanted the earth to open and swallow him, and I wished that it would, and never let him out again.

IT was not often that one had a chance to see the great Newbold put down. But down he was now. Just then that ornery boy, Chip, leans out from the table, after shoving down the last feed on a bale, and just as the driver yells “Bale!” the kid sings out:

“Hey, Newbold! Is this a dance that we’ve bought tickets for? Or what are all the skirts around for?”

I thought that Rooney would climb up and massacre that kid, when he heard the remark; and the bale roller leaned his head out after he’d jerked the bale out of the press and locked the door behind it, and gave the kid a glare.

But I understood.

Chip wasn’t cashing in on any female sympathy. And it gave my heart a stir. I can tell you, when I saw what an outright man the boy was. I knew that he was sick all the way to the bottom of his boots from the work he had done, but he wasn’t complaining! He was willing to leave the women out of the matter!

He said to Marian Wray:

You can imagine that the chief did not waste any time using the kid’s lead.

“You see—fresh kid that wants to show us how to run the hay press. I’m taking some of the crow out of the little rooster!”

“I know,” says Marian Wray. “Some of them are that way. Gutter ruffians from birth. I suppose one ought to pity the poor little wretches!”

But there wasn’t much pity in her, just then. She gave the kid a look that would have melted a galvanized iron roof; but Chip already had his back to her and was jamming a fresh feed down the throat of that old press. He was as game as they came!

He had given Marian Wray something to think about. She gathered the remnants of her usual smile about her—strange how pretty girls all learn to smile like actresses!—and pretty soon off she went.

As soon as she was hull down, I waited for the boss to call poor Chip off the table, and I even saw the boy give the chief one side glance, but Newbold pretended to have forgotten him. There was no mercy in that heart of his. And having cashed in on the boy’s pluck and spirit of fair play to get the girl out of the way, Newbold just left him up there to work his heart out.

It seemed to me that every minute would be his last one. I could see the boy wabble and shake as he staggered about. But he continued to stick that pitchfork into the hay; and he continued to heave the hay over into the mouth of the press; and his last bale was as fat and firm all the way through as his first one.

And, finally, the last long hour wore away from minute to minute, with the whole crew of us watching nothing but the fight that boy was putting up.

The fact is that he lasted until the sun was right over our heads, and by twelve, noon, he had shoveled sixteen tons of hay off that platform. I have had a lot of grown men who knew the business doubt the thing, but I was there and saw it done, and I added up the pages in the bale-roller’s book with my own fair hand.

It was eighteen pounds over sixteen tons, to be exact. And the boy was fifteen!

As I was saying, he kept right on until the cook banged on a pan at the door of his cook house to show that it was high noon by his stove, no matter what it was by the sun.

So the boys knocked off work, and the derrick and power horses were unhooked, and everybody started wiping chaff out of his shirt collar, and dust out of his eyes. But I watched the kid and saw him start down the side of the press, and then change his mind and come slowly over to the hay dump, which was slanting up to the feed table, half dust, clods, and the rest chaff. He lowered himself over the edge of the table and slid down.

Halfway to the bottom, his body slewed around, like a boat in a running current with nobody at the tiller, and he rolled the rest of the way.

You might have thought that he had given his head an extra hard knock on a lump of sun-fried earth on the way down, but I knew what was the matter.

I ran over and picked him up by the nape of the neck and had a squint at his face. He was blue around the mouth and white around the eyes. He looked like one of those painted monkeys. And he was limp as a dishrag.

So I hauled him over to the drinking water and doused him good and plenty, and dragged him into the shade under the cook house, and hoisted his legs higher than his head, and began to fan him.

The boys came around and helped. They didn’t say anything. Not a one of them had anything to offer. But one man took the fold of newspaper out of my hand and continued the fanning, and I remember how Pete took a soaked rag and squeezed out a steady stream of drops onto the hollow of the kid’s throat. They were an ugly lot of men. They were ashamed of themselves, and nothing is more dangerous than a man who’s ashamed of himself. He wants to get back his self-respect all in one stroke.

Big Newbold came up and said: “Well, the brat’s had his lesson, I guess.”

Nobody spoke, even then, but every man jack of us turned and gave the boss a good, thoughtful look. He said no more. He cleared his throat and pretended to get interested in the making of a cigarette. But I saw a small white spot in both of his cheeks, and I knew that even Newbold, if he couldn’t feel shame, could feel fear, at least.

We worked about a half hour, and still nobody spoke a word, except when one man would call another a chump, with underlinings, and shoulder him out of the way to take up his share of the work. For my part, I had made up my mind that Chip was dying, and that Newbold would be dead soon after, when the kid fluttered his eyelids, and looked at us in a puzzled way, and then sighed and closed his eyes again.

“Mommie!” says he, and turns over on one arm, and sighs again.

It knocked me all in a heap, for some reason. I mean, we didn’t need to see his birth certificate, just then, to see that he was two or three years younger than we’d been rating him. If we felt sick before, you can imagine how we felt when we heard him speak, and saw him turn and sigh, like a child in his bed when his mother kisses him good night.

Newbold took hold of me with an iron hand and moved me out of the way and leaned to have a look. He didn’t say anything. His face was better than a whole book filled with words.

Just then up pipes a quiet, musical voice, as cold as the snow-water in a mountain stream, and says:

“I see that you allowed him to keep right on showing you how to run the press, Mr. Newbold!”

It was the girl.

Her horse had cast a shoe, and she’d come on back at a walk to see what our camp could do about it, because she knew that we had a good blacksmith attached.

Well, it was the very worst thing that could have happened to us. It was the sort of a story that we would not like to have even men repeat. But as for a woman—why, it was a yarn that every woman in the countryside would eat up, and give forth again with embroideries. And every time the yarn was repeated, our crew would be made to seem more and more like cannibals—child-eaters!

Above all, to have Marian Wray talking about us, and starting the thing! For everything she said would be taken as an under-statement. My first thought was to start right then, horse or foot, and climb for the nearest railroad, and put a thousand miles of ’dobe between me and that scene.

I think that the rest had the same idea.

But the first thing we knew, there she was, sitting with the head of the boy in her lap, and not regarding us at all.

She just said: “The poor child! The poor little boy!”

And she ran her thin fingers through his dusty, chaff-filled hair, and brushed it back from his forehead.

This was only a starter. Somehow, she managed to convey that there was a thousand leagues of distance between such a “poor little boy,” and grown-up male brutes like us.

Perhaps she was right.

Then, while the iron was hot—melting hot—she said:

“You might stop pouring on the water. His temperature is already subnormal. We might as well try to save what’s left of his life.” But she added at once: “Though, of course, after the shock of this he’ll never be anything but the wreck of a man!”

We didn’t question her medical wisdom. It was a case where we felt that she had us with a strangle hold, and the less we said, the better for all of us.

I forgot exactly what she did. But I think that she asked us if we had any whisky, and begged our pardon for suggesting that we might be carrying such poison around with us. Poison? She was the poison, just then. She was poisoning us all. I swear that she even kept a little smile at the corners of her lips. And every now and then she raised her glance from the boy and fixed one or two of us, slowly, carefully, as though she wanted to remember our names and faces for future reference.

Altogether, it was a miserable time. I even forgot to feel any sympathy for the boy. I would rather that he had been run over in a stampede and turned into a patch of fertilizer on the ground than that he should have involved us all so deeply.

Now and then I gave Newbold a look, and after the second or third one, I was amazed to see that even the rhinoceros hide which he wore in the place of a skin had been pierced, and that he was suffering a good deal. Rather more than a good deal!

Finally he said: “Miss Wray, I didn’t know—”

She lifted her head, with that ice-cold imitation of a smile.

“You didn’t know what, Mr. Newbold?” she asked.

He faced her. I must say that for him.

“I didn’t know that I could be such a brute!”

I’m sorry to say what followed. She looked him right in the eye and answered:

“Oh, didn’t you?”

It was the wickedest remark I’ve ever heard passed along from one human being to another. And I’ve heard some pretty active tongues inspired with red-eye, at that.

Just then the boy stirs and groans.

“It’s all right,” said she. “It’s all right now, poor dear!”

At that, the kid sits bolt upright, with a start. He gives a look around, and stares at the girl.

“What’s all this kindergarten bunk?” says he. “Cut it out!”

And he got right up on his feet!

WELL, I must say that it did me a lot of good to see the boy fetch himself up to his feet again. He made a sort of wabbling first step, but he caught hold of himself again and leaned a hand against the rim of a cook-wagon wheel.

“Gimme the makings, Joe, will you?” says he.

I knew by the green of his gills that he didn’t want a cigarette. But I fished out the makings and began to roll one for him. I could see that he was making a play to kill time. The rest of the men could see the same thing.

But the girl did not understand. She followed the boy and says to him:

“Don’t you think that you’d better lie down again? You really are not as well as you think. Something has happened, my poor boy—”

He gives her a mean look. Then he turns to the rest of us.

“How does she get that way?” says he. “Lead me away from it, Joe, because it might be catching.”

It set Miss Wray back quite a few steps to hear these cracks.

But she kept on. When a woman has made up her mind that she’s being good, and that she’s on the right track, hardly anything will stop her.

“As a matter of fact,” says she, “hadn’t you better come home with me? My father has need of such a—man—as you are.”

She set off that word “man” as a concession, between a couple of her sweetest smiles.

Says the kid: “Who’s your old man, ma’am?”

“He’s Judge Arthur Wray,” says the girl gently, so as not to swamp the poor kid with the full glory of the name.

“Judge Arthur Wray? Judge Arthur Wray?” says the kid, cocking up one eye, as though he had to think hard to remember a name that everybody in the West knew as well as they knew the Tetons. “Oh, yeah. I remember, now. He’s the fellow who roped and hog tied the Injuns in that land deal, ain’t he?”

Well, it was true, some people said, that old Judge Wray had used more corn whisky than cash to get out of the Indians some of the best rangeland that cows ever grazed.

If it was not a tender point with the Wray family, at least it was plain that the girl had heard about it. She got a sunset-red into her face in no time at all. Perhaps she could have answered, but that terrible kid didn’t give her time.

He went right on:

“It might be that your old man wants a good hand on his place. But you tell him I’m mighty grateful, but that I don’t talk Injun good enough to be much use to him. And I do talk hay press.”

“Of all—” began the girl.

Then she stopped herself. Perhaps she remembered that she was about to say something trite. Perhaps she only cut off something always old but always new.

She just takes a fresh breath, however, and goes ahead. As I was saying, you can’t stop a woman when she thinks that she’s carrying the flag. She’ll keep on carrying it even while she’s walking over a thousand faces, grinding in her high heels.

“You’d better think it over. I left my father a few miles back, but we can pick him up on the way. And when I tell him—well, I’m sure that he’ll want to employ you. You know that there’s room for young—men—to rise with him. He had to go out on a hunt this morning, but I think we’ll find him on the way back.”

“Hunting Injuns?” asked the boy, who seemed to be all calluses and no tender places.

The girl was patient, and sweet as pie.

“Hunting a thing worse than Indians,” says she. “A real criminal, mankiller. A desperado,” she winds up. And shakes her head, and smiles again, as though the courage of old Judge Wray staggered her a little.

“What might his monicker be?” says Chip, the tough kid. “What’s his name?”

“My father’s name?” says she, as patient and angelic as ever.

“No. This here desperado’s,” says the boy.

“His name,” she said, “is Douglas Waters.”

“Hold on!” says the boy. “I didn’t know you played with a joker in the pack.”

“Joker?” says she, a little bewildered.

“You mean,” says Chip, “that your old man is out man hunting the squarest shooter, and the best bunkie, and the rightest puncher that ever rode the range? Is that what you mean? Then if I see him, I wouldn’t talk about a job, I guess. I’d talk something stronger.”

He turns to me:

“Joe,” says he, “come on over here and lemme show you something about the way to throw a Jackson fork, will you?”

“Sure,” said I.

I got hold of him under the elbow, and he gave me plenty of his weight to pack. And so we walked right out on the well-meaning Miss Wray!

She seemed to be lagging to leeward with most of the wind out of her sails, and I must say that our chief seemed to be swallowing a smile that would have choked a sperm whale.

I didn’t talk about Jackson forks. I just rushed the boy over to the shady side of the pile of bales and sat him down there, and then, with my hat, I fanned him.

He leaned back with his arms and legs sprawling, like a hopeless drunk. And his lips kept twitching in and out and up to the sides, like a man who is wondering whether he can last it out or not.

The first thing he said was: “Keep your eye peeled. Don’t let ’em see me—like this!”

“You’re as right as a trivet,” says I. I never knew what a trivet was. But so the saying goes. “Don’t you worry,” said I. “I’m keeping my eye peeled. If anybody shows, you’ll be drawing a design on the ground and teaching me something.”

His lips twitched a couple of more times before he managed to smile. And then he took my advice and began to draw lines in the dust. But he put his eye on me for a minute.

“You’re a partner, Joe,” he gasped. “You’re an old partner!”

I wanted him to lie down, until the sick fit passed. But I didn’t make the suggestion, because I knew that he wasn’t the kind that lies down. You find men like that, one in a million; and boys like that—one in the world.

He preferred to sit up and take his medicine that way. He would rather have been on his feet, I knew.

And, while I watched him fighting out his fight, and beating the game, I looked the boy over, and admired him a good deal more than I know how to say.

And I wondered at him, too, and thought to myself that, after all, boys are foolish when they wish to grow up. If they’re strong enough to sight a rifle and ride a horse, they can do most of what men can do. And if they can do these things, they’re about as good as men, take it all in all.

Besides that, they have advantages all their own. They’re all by themselves. A woman is a woman from the time she is old enough to take a baby doll by the scruff of the neck and call it hers. And a man is a poor, weak, sentimental, sickly servant of the grown woman, their house-builder, jack-of-all-trades, supporter, and royal jester. They reward him by putting a cap and bells on his head, and they give him, as a bauble or scepter, a pretense of admiration for the muscles and the brain power which is always used merely to support the wife and the brats.

A grown man is a grown idiot. That’s all. But a boy is different. That’s why a boy is the only four-square-to-all-the-winds creature in the world. He goes his own way. He hews to a mark and a line, and lets the chips fall where they may—and he generally hopes that they’ll fall in your eye.

And as I sat there, fanning Chip, and admiring him, I couldn’t help wondering at the ease with which he had settled beautiful Marian Wray.

She was beautiful. She was lovely enough to take off the top of a man’s head. One of her smiles was enough to keep a poor puncher awake at night, turning from side to side, for a month on end. She was so charming that she had taken the crew of the hay press into the hollow of her hand in no time at all. Just a look around had been enough.

But she couldn’t take Chip into the hollow of her hand. Not into the hollow of two hands, even. Indeed, she was helpless.

What was all her beauty to him? He would rather have had a shiny new .22 than all of her, ten times over. He would have traded a gross of Marian Wrays for a three-year-old mustang with a kink in its tail and fire in its eye.

So where the rest of the men had been paralyzed, he had walked right in and used his fists, so to speak, on the thin china of which she was made, and he had wrecked her, and blamed her father, and given her something to think about that would keep her turning from side to side for months on end.

Well, boys are a weakness with me. They always have been, and they always will be. I admire them. But when it comes to a show-down, I envy them more than I admire.

But as I sat there and looked at Chip, and thought of his power, and of what he had done that day, and might do again, I couldn’t help sighing when I remembered that, within a couple of years, he would be like all the rest of us. The arrow would strike him in the heel; the sweet poison would run through flesh and bone; he would become the same sort of maundering sentimentalist that we all know so well and understand so intimately, because we’re the same woman-ridden, adoring, despising caricatures of Samson.

The glory of Chip was sure to pass. He would come to his mortal doom, sooner or later.

But just then, he was complete, independent, sure as a fortified Rock of Gibraltar. And I looked at him as at a sort of super-creature.

Then he began to talk about the Jackson fork.

THE next three weeks I don’t like to think about, and I don’t like to write about.

First, the weather got hotter every day, and the hay press broke down every day.

Second, the chief fell in love with Marian Wray, and the hay press broke down every day.

Third, inside of forty-eight hours everybody on that crew hated everybody else, and the hay press broke down every day.

Fourth, and most important of all, the hay press broke down every day.

Taking the things one by one, I have to admit that the middle of the Nevada desert is about as hot as you can wish; but it was cool and crisp compared to the heat that we had out there on that pressing job. The last moisture was sucked out of the hay. You could break the stalks across as though they had been the stalks of straw, after the harvest. And the last moisture was drawn out of the men, also. We were all dry powder, and any word was likely to drop like a spark into a mine. Gun fights were not in order, quite; but I had two fist fights on my own account. The first one was all right; but the second was with Pete Bramble, and we beat each other to a pulp. I got an eye on me that looked like a leather patch, and poor Pete had to talk and eat on one side of his face for days afterward.

But somehow the worst thing that happened, next to the hay press, was the way that the chief fell in love.

“Fell” is the only word for it. He dropped about a mile, straight over the edge, and he landed so hard you could hear the splash.

You see, it appeared that old Judge Wray himself was thinking about buying a hay press, for reasons unlike those of Newbold. Wray’s land was so good that his cows simply couldn’t eat all the grass that grew, and so he wanted to fence off some sections and raise hay on them. There was plenty of sale for it. So he came over a number of times, and Marian came along with him.

Poor Newbold hardly ever looked at her, but you could tell at a glance what he was thinking about. He was out of his head about half of the time.

I heard them, for instance, talking together one day, and the judge says:

“A coat of paint would save that machine a lot. Put on a good wearing coat of heavy paint and the timbers wouldn’t crack in the sun so much. I’ve got some heavy gray stuff at home—”

“Dark gray,” says Newbold, “looking kind of blue in the evening light—”

“Who the deuce cares what it looks like in the evening light?” says Wray. “The bale this turns out—what would you say the weight is?”

“About a hundred and thirty-five, I’d say,” says Newbold dreamily.

“What?” says Wray. “I thought you said they’d average closer to two hundred!”

“Oh, you mean the bales,” said Newbold.

“What did you think I meant?” asked the judge.

Yes, Newbold was completely knocked over by the pretty face of that girl. Perhaps he was most attracted by his very sense of the impossibility of the thing. For after she knew how he had treated young Chip, her lip curled every time she looked at Newbold.

Not that Chip asked for sympathy from any one. She was scared to death of his active young tongue and never tried anything more than a smile with him after that first day when he let her down so hard.

But the weather, and the wrangling among the crew, and Newbold’s stunned look when the girl was around, were all nothing compared to that danged press.

Never could tell what would happen.

Sometimes it would be in the red-hot middle of the day when the only way to escape wishing to die was to keep working and perspiring, so that the oven-blast of the air would have something more than your hide to burn up. But usually it was in the dewy cool of the mornings, or in the evenings when the sun was not so full of sledge hammers—yes, usually it was when work was almost a pleasure that the press would give a groan, or a squeak, or a crack, and you could tell that something was sprained, or a bone broken somewhere.

Twice we had to spend half a day taking out the whole side of the box so as to work on the vitals of the affair. And again, something went wrong with the gears of the power beam, and we were a whole day out of pocket.

Yes, instead of averaging forty tons a day, we were averaging only about fifteen. It was sickening to think of!

But the only thing that kept us going and turning out even that much was the kid. He seemed to be able to read the mind of that machine, and he could tell in a moment just exactly what was wrong with it. He saved us time that way, and also he saved us a good deal by what he taught us about doing the work.

Before I was through, like the rest of the boys, I had tried my hand at everything on the job, from Jackson bucking to bale rolling and power driving. The bale rolling was the hardest and the most interesting.

All you had to do, when the driver yelled “Bale!” was to knock open the door with an iron bar, drop the bar, grab the five stiff wires as the wire-puncher shoved them through, cinch up and tie those wires with a fast figure eight—and if you were fast enough, you took the last wire right off the needle of the puncher—and then you hollered: “Tied!” And as the power driver started his team, the heater floated up, and as soon as it was clear of the table, the big first feed began to shoot down.

You had to get the bale out of the way and the door shut before that feed started to descend, and to do this meant grabbing the hay hook off the beam overhead, sinking it in the top edge of the bale, and while with one hand you jerked the bale out and broke it to the right across your knee, with the left hand you caught hold of the door, slammed it, and disengaging the hook from the bale you used that hook to pull over the locking bar.

After that, you simply had to roll the bale onto the scales, weigh it, write out its weight on a tag of redwood, and again on the page of your checking book, trundle the bale out to its place in the growing stack, and lift it into its berth, perhaps three feet high. Just as you were breaking your back to get that bale up, the power driver was sure to yell “Bale!” again, and back you sprinted for the dog-house to do the whole thing over again.

Well, it was a pretty hot business, but it was a thing full of knacks from the tying of those infernal wires to the rolling and lifting of the bale itself. Little Chip knew all about the tricks. He could fair make the bales walk along the ground, and nobody in the outfit could punch the wires through fast enough to keep Chip from waiting for the last one to come.

Of course, he couldn’t last long at it; but while he worked, he made things hum, and he showed us how to do it, and how to step so that not an inch was wasted. Sometimes it almost seemed as though he had built the first hay press in the world, he knew so much about the job!

But even the kid could not ward off the bad luck that followed that machine. And every day, what between the girl and the press, Newbold got blacker and blacker, and stared more and more at the ground, and not even Chip dared to sass him any longer.

Newbold used to walk out in the evening to the top of the nearest roll in the ground, and there he would stand as gaunt and melancholy as a scarecrow, staring over the surrounding acres, and weeping tears of blood in his heart because he knew that he would never have enough time, at this rate, to bale all the hay that he had cut. And to think of it lying there to first dry to powder, and then to be rotted by the winter rains, was enough to nearly kill him. He wasn’t tight, I suppose; but it was a torture to him to see any wastage.

The atmosphere around that place grew more and more charged, and pretty soon all of us knew that it was only a question of time before the sparks would begin to jump—sparks that might burn the life out of some one!

The trouble was that, even if things had gone smoothly, we were cow-punchers, not mechanics. To do the same thing hour after hour was worse than a gun play on us!

That was about the time when Sheriff Murphy came out to visit us, and with his visit came the beginning of the end. It was just after dusk. We all lay around on our blankets, which we had rolled out on shocks of hay, the head end higher than the feet. Now we lay on our stomachs, our chins in our hands. Some of us smoked cigarettes. Some of the boys smoked pipes, but, for one reason or another, every few seconds there was a faint glow, and the face of some one stood out in rosy dimness at one part or other of the circle.

I remember that big Cash Logan was talking, at the time, and telling about how he once had a fight with a Canuck lumberman, a regular log-driver; and how the Canuck, being a little pressed, had pulled a knife to help out; and how he, Cash Logan, had used a trick he had learned when he was a boy, turning a handspring and whanging the soles of both shoes fairly and squarely into the face of the other fellow.