RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Administered by Matthias Kaether and Roy Glashan

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

ONE of the last stories Faust wrote was a long novel, "After April." According to the editors of The Saturday Evening Post: "'After April' ... is the strange and disturbing love story of a man and a woman who had experienced in their lives the worst which a war, already old and skilled in the flagellation of human hearts, can bestow. For persons who have looked upon death and those other things which are more unbearable, there can be no happy ending—nor any unhappy ending, either. For their sufferings are merely historical warp and woof in the tapestry of human experience." In this novel we catch a glimpse of Faust's literary maturity. It makes one wonder what Faust might have produced, had he averaged writing only one book a year rather than twenty.

—Quoted from: Jon Tuska & Vicki Piekarski, The Max Brand Companion, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1996.

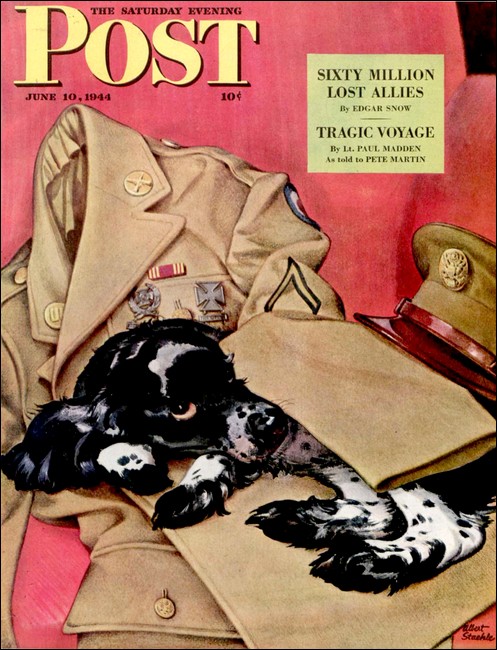

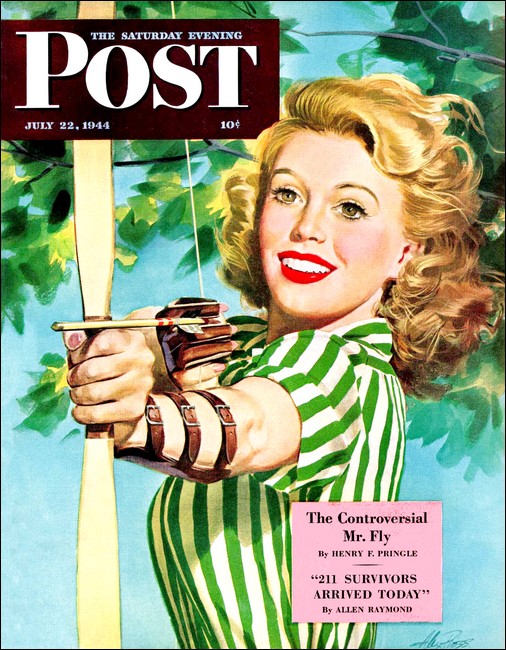

The Saturday Evening Post, 10 Jun 1944, with 1st part of "After April"

Miraculously, Peter Gerard had found his lost wife—but she was a stranger who neither knew him nor wanted him. Beginning the dramatic story of a pilot who deliberately hunted death in the sky.

THE hospital was an old barn made over, and in May of 1940 the acrid smell of antiseptics had not yet killed the fragrance of centuries of stored hay in what had been the loft. It was the time of Dunkirk, when the RAF was trying to maintain a shelter above the refugee thousands on the beach, and therefore the hospital beds were fairly filled with the wounded, but for the moment there was only one patient in the office of Dr. John Grace. This was a thirty-year-old Hollander, Peter Gerard, who had been flying hardly ten days with the English, although already he carried other marks of the battle. He stood before the doctor, stripped to the waist, with a bit of old bandage around his head where he had been grazed by shrapnel, and another high on his left arm, which a bullet had nicked. The doctor finished dressing a small but ragged cut across his ribs made by another shrapnel fragment in the air over Dunkirk this day. Now Doctor Grace held in his hand the hospital record of this man and shook his head over it.

"In ten days, this is your fourth visit," he said in his loud voice. He had been a baby specialist, a famous pediatrician, and he used to say that was why he was at home taking care of the RAF. "Because they're all babies," he would say; "just little babies that have to be petted and spoiled and spanked."

Now he looked up at Flight Lieutenant Gerard with a great scowl. "How many Jerries on your score?" he asked.

"I'm not quite sure, sir," said Gerard, his English accent perfect, though he had to labor over it a little. He was one of those dark Hollanders, straight-standing, with a fine head, and all the flesh thumbed from the body by hard exercise. Every breath he took showed his ribs from top to bottom.

"You're not quite sure of your score? Why the devil aren't you?" asked the noisy doctor. "Is it so good that you have to be modest?"

Peter Gerard was not annoyed. He had been looking out the window, now dimmed by coming twilight and a heavy fall of rain, so that there was hardly a view of the hills of Kent, but rather a mere smudge of green, like a stain in the glass; now he withdrew his attention from this and looked back at the doctor.

He said in his slow, careful way, "There were three before this afternoon, I believe. I'm not sure how many will be credited to me today."

"What would you guess?" asked Doctor Grace, peering up under his brows; and the young nurse in attendance held her breath as she listened.

"I believe there were four," said Peter Gerard. His lips twitched into a smile that came and went in a flash as he tasted pleasure infinitely deep and savage. "Yes, five, perhaps."

And his glance dropped slowly, as though he were watching something at a distance plunging rapidly through the air.

"Let's say you've got eight of them, then," said the doctor, staring at the nurse until her eyes lost their brilliance and she started breathing again. "Eight of them, and, therefore, we'll have to take good care of you."

"Sir?" said the Dutchman, touched instantly with concern.

"The fourth time you've been in here, and the third patch on you," said the doctor, and he looked at Peter as though he were a smoky glass that could not be seen through, like the green panes of the window. "Look here, my fine-feathered Dutch friend, a patch beside a patch is neighborly, but a patch upon a patch, that's outright beggarly."

"Very good, sir; very amusing, doctor," said Peter, still anxious.

"Look at his sour face," said the doctor to the nurse. "I wish you'd take him out for an evening and make him laugh once or twice, Nelly."

"I can't do that, sir," she answered. "He has his own private war with Hitler, and he's all wrapped up in it."

"He doesn't like women," said the doctor, terribly outspoken. "For instance, you're a pretty girl, Nelly, a damned pretty girl, but he won't look at you."

"No, sir?" said Nelly, smiling at the flier.

Peter turned on her a troubled eye that had not the least recognition in it. "But naturally, yes, yes," said he, doing his best.

"That's no good," said Doctor Grace. "Don't try to hide yourself from me. You can't slam doors in my face, young man; not if I decide to find out about you. These surface scratches don't matter, but what's your invisible wound? I'm going to put you to bed here for a month and find out."

"No, sir; I can't do that," said Peter, alarmed.

"Afraid, eh?" the doctor roared. "Afraid of the long rest and the monotony, are you, the rows of white beds, the days without end, the chatter of voices that you have to hear?"

"I'm in perfectly good flying shape, sir," Peter told him, picking up his shirt. "I can't stay here."

"You can't, eh? I'm your superior officer. Lieutenant Gerard, and I can order you into this hospital as long as I please."

Peter stopped, halfway into his shirt, and stared helplessly.

The voice of the doctor might be mere friendliness or it might be the voice of authority. With this nation, one never knew what to do. A slap on the shoulder may make a friend for life—or shake the Empire to its foundations.

"Go into that next room," commanded Doctor Grace. "Do as I tell you and step along."

Peter Gerard clicked his heels and made of himself as much of a soldier as he could without a shirt.

"Yes, sir," he said. "With the major's permission, I will merely check over my plane first and—"

"What the devil do we have ground crews for? Why do we have plane captains?" broke in the doctor. "They'll check the plane better than you can... What's your profession?"

"A lawyer, sir."

"Well, you can't talk yourself out of my hands, even if you use Dutch. Get on in there."

"I beg your pardon, sir, but I have a necessary engagement this evening, and if I am permitted to report tomorrow morning—" said Peter.

"You have received an order, sir," said the major coldly.

"Yes, sir," said Peter Gerard and, turning slowly, he forced his feet to carry him through the doorway into the next room.

"Blood count!" roared the doctor after him.

"Yes, sir," said a distant voice, and the door closed behind Peter.

"What do you think of that, Nelly?" asked Doctor Grace.

"He seemed, actually, to be a little afraid of the hospital, doctor, didn't he?"

"Of course he is. He's afraid of anything that may keep him out of the air. Don't you understand why?"

"No, doctor."

"Can't you guess?"

"Perhaps it's because he's so eager to make a great score?"

"Do you really think that?"

"No," decided Nelly, "I don't think he's very eager about anything."

"You're wrong again," declared Doctor Grace. "He's eager to do one thing in the whole world."

"To do what, doctor?"

"To die.... Come, come, now, don't fall into a state of shock. Hamlet was only a fellow in a book, but there have been crowds like him who've lost their taste for living. How do we know what the war has taken from Peter Gerard or what's left for him? He's lost something—he's lost his country and perhaps something more. I intend to find out what it is." He commenced to walk the floor. "Babies, babies, all of them," he growled. "Babies that can't speak or won't."

The door opened from the hall and into the room came a young air-force group captain, big and broad enough to be a weight- lifter. Two sergeants were behind him.

"Yes, Allan, what do you want?" snapped the doctor, continuing to pace the room.

"Good afternoon, doctor," said the big young man. "I understand that a Lieutenant Gerard has just reported to you?"

"What of it?"

"I'd like very much to have a word with him."

"You can't."

"Is he that badly hurt, doctor?" asked the captain.

"No. But in a way, yes. Don't bother me."

There was a moment of pause.

"Very well," said the captain stiffly. "Good afternoon, sir."

He had turned to the door again when the doctor said, "Wait a minute, Denham. Come back here. How long have you known this Gerard?"

"I've never seen him, but—"

"Then you're no use to me.... Hold on a minute. Why do you want to see him?"

"Will you tell me one thing first?" asked Denham. "Perhaps."

"Was he badly wounded this afternoon?"

"No. Not this afternoon."

"I'm glad—I'm very glad of that," said Denham, taking breath.

"Why?" asked the doctor. "What's the matter with you three?" He looked at the two sergeants. "What does Lieutenant Gerard mean to you?"

"He's been keeping the flies off Baby all afternoon," said Denham, grinning. "Baby Blue is our bomber, you know, and the Jerries almost had us. One motor gone and the other coughing. When we began to trail smoke, you should have seen the Jerries come for us, zooming."

"And this Gerard kept them away, did he?"

The older of the two sergeants said, "The finest thing I ever saw, sir."

"Stood up there over us and knocked them away," said Denham. "I think he got four, didn't he, Joe?"

"And another one was awful sick," said Joe.

"He stayed upstairs for us all the way home," said Denham. "Didn't have a pint left when we landed. We went over to the fighter strip and asked for the pilot of that Spitfire, but he wasn't there, and when we found out that he was in the hospital—"

"What do they think of him in his squadron?" cut in the doctor.

Denham hesitated. "Well," he said, "the fact is—"

"They don't like him, do they? Too dark and deep, eh? Good Englishmen don't like faces that haven't the look of plenty of beef and beer. The man won't talk; looks as though he had a bellyache all the while?"

"They seem—well, not very fond of him. But we are, doctor. May we see him for a moment?"

"The three of you? I wouldn't crowd him."

"I'm sorry, boys," said Denham.

"All right, sir," said Joe. "You'll talk for all of us, sir."

The sergeants went out.

"Step in there and get Gerard for me, Nelly," said the doctor.

She hurried into the next room.

"Is something very wrong?" asked Denham.

"About as wrong as could be, Allan," said the doctor. "This Dutchman is one of the suicide boys. You understand?"

Peter Gerard came back, with his shirt on once more.

"This is Captain Allan Denham. Peter Gerard," said the doctor. "He flew the bomber you herded in today."

"It was a sweet piece of flying, and shooting, too, mind you," said Captain Denham, as they shook hands. "It was a bit of all right."

"Captain Denham," said Peter, "you make too much of it. It was like fishing. Your plane was perfect bait, and as their fighters kept rising, I only had to sit on the bank, so to speak, and keep dropping in my hook. I was too small for them to see."

Denham looked at him for a moment and then made up his mind to laugh.

"I'm glad you're here, Allan," said the doctor. "I've just remembered your park at Denham Hall. A good place for resting. Well, I want you to take this fellow home with you and find out what's thinned his blood."

"I beg your pardon," said Peter, troubled.

But the doctor went on loudly, "Or else I'm putting you in a hospital bed for a fortnight. You hear me, lieutenant? ... He's a sick man, Allan, and I may not have the right kind of medicine here."

"You are under the weather?" said Denham, looking him over. "They've nicked you too often and taken too much out of you. I'm for home tomorrow, if you can arrange to come."

"I'll do the arranging," said the doctor.

SO, on Friday, Peter Gerard was with Denham in a big charabanc

loaded with men off on leave. The captain did what he could to

make conversation, but it was little use. The Hollander was

perfectly but formally polite and his attention wandered away

from time to time toward the hills and big, open woodlands, as

though all that beauty were something far removed and dimly to be

wondered at. His silence was that of a man enduring constant

pain. They got out at Denham Hall and walked up through the park

to the house. It was the classical country home, with trees as

old as England, lawns smoothed by centuries of rolling, and all

the romantic nonsense of evergreen labyrinths, a model little

Chinese garden, and iron deer standing alert in the clearings.

The hall itself was a big Georgian place with Ionian columns

about the entrance. Denham led the way past this.

"We live in the south wing," he said. "You know how it is since all the fugitives have been crowding into England; every room is working and the owners just take what's assigned to them. It's the only way."

Denham's wife opened the door to them. She was a pretty girl, but as still as a mouse, and one had to look twice to discover her charm. She held Peter's hand for an extra instant as they met.

"Allan has told us about you," she said, "and we're very, very happy to have you here."

In spite of her quiet, he had a sense of entering her life deeply and intimately.

For living quarters they had only the great hall of the house, a fifty-foot room screened into sections. The kitchenette was arranged around the huge fireplace to use its flue; the dining- room portion contained a big table with a mosaic top and gilded legs. There were tall mirrors everywhere and several ancestors were framed on the walls—a woman with a starched ruff choking her, a dyspeptic gentleman in armor, and other faces looking out at them through darkening windows of the past.

There were no closets, but there were improvised racks for hats and coats and clothes thrust out from the wall which gave an effect like a laundry or a cleaner's shop. A bow window was curtained off for the bedroom of Denham's sister, and Peter was to sleep on the living-room couch. While he was being shown around, the sister came home from the factory across the fields. She wore overalls thick with grease, and had a black smudge across the bridge of her nose. She was one of those rare girls who are not tied up in the hips and shoulders, and she walked with a good easy swing and brought down the heels of her brogans with as hard a thump as any boy. She slumped into a Louis Quinze chair, hands in pockets and feet far apart.

"Man, am I tired!" she said. "We came within five pieces of the plant record today, my gang did; and my boss says I'm as good a man as any of the lot of them."

"This is Peter Gerard. Charlie," said her sister-in-law.

"Hello, Peter," said the girl.... "Is that beef I'm smelling, Audrey? You haven't some real beef in that oven, have you?"

"Charlie!" said Audrey. "Don't you understand? This is the man who brought Allan back safe from Dunkirk."

"Oh, no, is it?" said Charlie. All the pertness faded out of her instantly. She came over to Peter and took his hand. "But you don't seem so terribly—I mean, I wouldn't have expected you to—" she said.

She had fallen into such confusion that she could not finish the sentence, except with a bit of laughter.

"I'm not a bit that way, I hope," said Peter, smiling a little, and just then there was a tremendous crashing fall on the floor above them, and a prolonged struggling.

"It's that pair of Danes practicing jujitsu again," said Audrey. "They have a plan for kidnaping Hitler, I think."

But while Denham laughed with the others, he was watching his Hollander with a curiously deepened interest, for he had not expected this lighter touch. It was like laughter in a sickroom.

"Go wash your dirty face, darling," said Audrey, loving her with her eyes.

"All right," said Charlie.

"And put on that blue frock."

"Do you like blue?" Charlie asked Peter, over her shoulder. "It's my lucky color."

"It's my favorite," he said, and once more Denham felt deep approval.

"Gin and bitters?" asked Denham. "It's the making of the British navy, you know."

You can tell a great deal about a man by the way he takes his gin and bitters. Peter absorbed his like a fellow with an iron palate.

"We're awfully crowded here," said Denham. "I hope you won't mind."

Then dinner came on, and Charlie appeared in the blue dress with a red flower in her hair. Now that her hair was up and the smudge off her nose, she was a very pretty thing to look at. But it was the roast beef that had to be admired in wartime, not a mere girl. There were only two ribs of it, but the family stood about with exclamations, and then Allan carved it with geometrical precision, into four exact quarters. His wife put away the trimmed bones for soup.

Charlie wanted to talk about the war.

"Tell me the best tricks you have in the air," she said to the guest. "What do you think up in the pinches?"

"It's just a matter of patience and training," he told her.

"Ah, is that it? ... Listen. Allan," said Charlie, "and maybe you can learn to be something more than just an old soldier."

"You train your plane very carefully," Peter explained to her, "and then, when you get in trouble, your Spitfire does all the thinking for you, just like a circus seal."

It pleased Charlie. They all laughed, and doors were opening to admit him more deeply to their company.

"And when you see the Jerries," she said fiercely, "what's the first thing you think of?"

"I only hope they won't hurt me too much, too soon," he told her.

Charlie shone on him. "I'm so glad you brought him home, Allan," she said. "You never had such good taste before. Why, he's just silly and one of us—just exactly!"

She was so wholly bright and gay that even Peter seemed to be forgetting everything except this moment. There was added to the cheerfulness a phonograph somewhere in the house, playing a concerto by Mozart, as careless and beautiful as bird song, and no louder. Still farther off in the house, men's voices began suddenly to sing Holland's great marching song that has carried her men to war so many times.

"Those are the Dutchmen that were moved into the north wing today," said Charlie. "Ah, I forgot that they are your people, Peter. Perhaps you'll have friends among them?"

"Friends? Yes, perhaps," he answered.

The song kept rising. When there is food and any drinking, the spirits of young men cannot help lifting, but as the volume swelled and the words entered the room more clearly, the eyes of Peter forgot his companions and looked away at something that faded and dwindled in an unhappy distance. Audrey and Allan looked quickly down at the table, but Charlie kept her eyes fixed upon his face of pain.

THE couch made an ample bed for Peter that night, but as he

tried to sleep, the moon slipped through the window and shone in

his eyes. He sighed, utterly spent, but an old premonition told

him that he would wait vainly for sleep now, hour after hour, so

he got up and dressed and went, as soundlessly as he could, out

of the house, with his image walking beside him in the great

mirrors.

It was warm summer night in the park. No matter how late, the phonograph still kept alive the tremor of Mozart's violins, so that the music followed him among the trees until he came to a fountain that was tossing its bright head in the moonlight and keeping up a murmur like the soft rushing of wind. The fountain figure was a Diana, with bow in one hand and the other arm over the neck of a deer. On the big stone bench, with her chin on her fist, Charlotte was contemplating Artemis with a frown.

"This is a bit late, Charlie, isn't it?" he asked her.

"I'm all right," she said. "I'm not a wounded aviator."

She was a little sharp about it, and instead of walking on, he said, "May I sit down?"

"Just bend your knees," said Charlie.

He took the place beside her and offered a cigarette. She said no, brusquely, so he lighted one and blew the white smoke at the moon. They were silent for a time.

"What do you think of that Diana?" she asked, breaking in on him.

"Silly, isn't she?" he said.

"You bet she is," agreed Charlie, sourly. "I don't like her or anything she stands for."

"Am I wrong in thinking that you don't talk very much like most English girls?" he asked.

"I had an American friend, is why," said Charlie. "He was swell. So I picked up some of his lingo. No good?"

"I like it very much," he told her. "I think it goes."

"With me, you mean?"

"Yes. Because you're brisk. And you go about things with a good swing."

"Like a boy?"

"Yes."

"Well, I'm not a boy."

"Of course not," he agreed.

"I don't feel so brisk and easy just now, either," she told him.

"I'm sorry," he said. "You didn't sleep well?"

"I did not. And why, do you think?"

"A little indigestion?" he inquired, with concern.

"Indigestion?" she said, and looked at him with disgust. "I wish it were only that!"

He waited. She said nothing.

Then she said, "I went and fell in love. Bang! Just like that."

"But isn't that all right?" he asked.

"No, it's miserable. I can't even draw a deep breath.... Did you ever?"

"Draw a deep breath?"

"No, fall in love?"

He was startled. "Yes," he said, after a moment.

"Just like that—bang?"

"Yes," he confessed, "Just like that—bang!"

"You would," she said. "You'd be that way, all right. But did you fall in the right place?"

"Yes," he said; "right while it lasted."

At this, she looked quickly up to him, then she began to stroke the lion's head that made the arm of the bench.

"Tell me about it, will yon?" she asked.

"No, please."

"Poor Peter," she said, "you're in dreadful pain. I know what it is. Oh, I know!"

"Will you tell me about him?"

"No.... But why shouldn't I? He's a foreigner, and that's bad, isn't it?"

"I'm a bit foreign, too, you know."

"Yes. I suppose you are," said Charlie, sighing.

"He must be very happy about it," he suggested.

"No. It's all rotten," said Charlie. "Tell me something."

"Yes?"

"You're one of those forever-and-ever people, aren't you?" she asked, sharply and suddenly.

"Perhaps," he answered, smiling at her. "I'm afraid so."

"I am too," said Charlie. "And don't smile."

"Certainly not," said he.

"Oh, Peter, it's so horrible. And I'm so sick, sort of, in the stomach."

"That's the way it is," he told her. "It would do you good to talk about him, probably."

"He's glorious and wonderful and modest and gentle and sweet and everything," she said. "Do you believe me?"

"Of course I do, Charlie."

"Isn't it rotten to have a name like that? How can a man be serious about a girl named Charlie?"

"Millions of men could, I'm sure," he said.

She jumped up. "I'm going for a walk. I can't stand it here. It's so stuffy. I wish—I wish there were a storm or something," she said.

"Shall I go with you?" he asked.

"No, no, no. I want to be alone," said Charlie. She changed her voice, "I don't mean to be rude."

"You're not, my dear," said he. "And I hope you'll be happier, too, someday."

"Thank you, Charlie."

"But I should wish just one thing—that you could see a little more clearly—especially by moonlight."

"But I see very well, actually," he answered, astonished.

However, she was already hurrying away at a walk, and then at a run. He looked after her and shook his head, but he had realized long before that he never would be able to understand any of these English very well.

IT was strange what peace and what relief from pain there was

for Peter with the Denhams. But by noon Sunday he was growing

nervous. From the windows, the three of them watched him striding

off through the garden that morning, moving at an eager, quick

step.

"What is it?" asked Audrey softly. "What do you think. Allan?"

"Look here," said Denham. "A man loses his country, his friends, his property—everything. Is it surprising that he's pretty much down? Expect him to be the life of the party? At that, he tries to do his share."

"He as much as told me. It's a woman," said Charlie.

"I don't think so, dear," said Audrey. Why not?" said Charlie. "Because it's old-fashioned for a man to be quite like that about a woman," she answered.

"He is old-fashioned," said Charlie, half angrily.

"Some of the refugees actually go out of their heads, you know," suggested Denham through pipe smoke.

"He makes the best sense I ever heard," said Charlie, "but his heart's gone."

"I don't think it's a girl, old thing," said Denham, "If it were, he's had something to make him forget her."

"Such as what, please?" asked Charlie,

"You, Charlie," said Audrey, smiling.

"Me? Oh, good Lord, Audrey, he thinks I'm nothing. I'm a juvenile. I'm a boy. That's all."

"You're plenty," said her brother, "and you've been handing yourself to him on a silver tray."

"He doesn't like that, does he?" asked Charlie wistfully. "He wants something that has to be hunted down and won, and all that. Men don't want gifts. They want to gamble."

"Darling," said Audrey, "aren't you a little embarrassed?" She smiled as she spoke, but she was a bit shocked.

"Why should I be embarrassed?" asked Charlie, opening her eyes. "Do you think I'm proud? I'd beg, borrow or steal him, if I could."

"Well, that's what will happen, then," said Denham.

"His heart's in the highlands, his heart is not here," said Charlie. "His heart's in the highlands, a-followin' the deer. Oh, damn it all. He'll be leaving by noon, you know."

"He's here for a fortnight. Doctor's orders," said Denham. "I told you all about that."

"What's doctor's orders to that kind of a man?" asked Charlie. "You'll see."

They had a chance, actually, before noon. Peter Gerard came in with a bit of color from his walk, but with a troubled look. He took Denham aside to say, "I find I have unfinished business that will take me back to camp."

"You're here under doctor's orders, you know," Denham warned him.

"Of course, I shall see Major Grace as soon as I return," said Peter. He went to put his things in his bag.

"Was I right," whispered Charlie.

"You were," agreed Denham.

"Oh, I wish I'd been wrong—I wish I'd been wrong," said Charlie, and flung out of the house.

They watched her hurrying over the lawn. A group of the young Dutchmen hailed her, but she went past them with lowered bead and left them staring after her.

"This is all getting too romantic and silly," declared Denham, but his wife silenced him with a look as Peter joined them again, carrying his baggage.

"Have you rested a little here, really?" Audrey asked him.

"It was like catching up with year of sleep," he said. "Won't I have a chance to say good-by to Charlie?"

Audrey looked at him with an odd smile. "She's having the blues," she said.

"I hope she won't be too serious about that fellow, whoever he is," Peter ventured to say.

"Has she told you about him?" asked Audrey suddenly.

"Yes. Do you know him? She told me that he wasn't English," said Peter, "and that bothered me a little."

"Did it?" said Audrey, lifting her brows.

"I mean, it's somewhat difficult to judge people who are strange to one's ways of living and speaking, don't you think?" asked Peter.

"Not always," said Denham curtly.

"You know this man quite well, do you?" said Peter.

"Yes, I know him well."

"And, of course, he's all right?" asked Peter of Audrey.

"I think he is," she answered. "I think he's very much all right. Poor Charlie!"

"Come along," said Allan.

Peter went down the path with him toward the bus stop.

"Just a bit enigmatic, aren't they—young girls, I mean?" suggested Peter.

"Some of the men are a little balmy too," said Allan, strangely sour.

DOCTOR GRACE discouraged the loitering of malingerers in the

waiting-room of his hospital by filling it only with benches that

had no backs, and on one of these Peter spent four hours that

afternoon, sitting erect and permitting the world to recede until

the sounds and motions were no more important than the winds and

rains and voices of last year, which he never could feel or bear

again.

The doctor himself opened the door presently, and, seeing the dreamer who had forgotten the world, he walked to him and sat down on the bench at his side.

There he remained for a moment, steadily watching, but there was not a sign from Peter.

After a while the doctor said, "Pleasant place, that Denham Hall, isn't it? And what did you think of Lady Maud?"

Peter, opening the invisible shutter that had closed off his brain, saw Major Grace sitting near him on the bench.

"I hadn't the pleasure of meeting Lady Maud, sir," he said.

"You couldn't help it," said the doctor. "For three hundred years she's been hanging on the wall and scratching out everybody's eyes. How's Charlie?"

"She's fallen in love," said Peter.

"Not seriously," said the major. "Wait a moment.... Yes, by heaven, she's old enough now. My sweet Charlie in love! Who's the man?"

"Not English, it seems," said Peter, with concern, "and that's, perhaps, a difficulty."

"You think so?"

"I mean that emotions aren't readily translated, for one thing. And Charlie is so wholehearted that, if she were wrong, she might continue wrong the rest of her life. Don't you agree?"

"You like her?"

"I think she's very charming. She's like—well, she's like nothing but herself."

"I hope you told her that," said the doctor.

"I wonder if I did?" mused Peter.

"This foreigner—what do Audrey and Allan think of him?"

"They both seem to approve, as a matter of fact."

"Tell me his name, will you?"

"Wasn't it stupid of me not to ask?" said Peter, shaking his head at himself.

The doctor drummed his fingers for a time on his bared teeth, an ugly habit of his, and studied Peter with a blank eye that was like a piece of witless optical glass.

"So you couldn't stay down there for a couple of weeks?" he asked.

"With your permission, sir?" asked Peter hopefully.

"You come from Rotterdam," said the doctor. "When were you last there?"

"On May fifteenth, sir."

"That was the day after the bombing?"

"Yes, sir."

"As I remember it, the Jerries told the Rotterdam people to show red flares if they surrendered, so as to avoid being bombed. They showed the flares and then the Jerries came right on in to bomb?"

"Yes, sir."

"And strafe?"

"They flew over just above the tops of the houses," said Peter. He spoke very slowly and began to draw himself up straighter. "They machine-gunned the people in the streets. All together, I think thirty thousand died."

"Your own family, Peter?"

"My grandmother, my wife."

The doctor was silent for a long moment. "I don't think we'll insist on hospitalization for you," he said at last. "You may report to your commander when you please."

"Thank you, sir. Then permit me?"

"Certainly," said the doctor, and watched the Dutchman turn smartly and retire with a thirty-inch step in a soldier's cadence.

IT was not long after this that Peter's squadron was ordered

to France, where the sky was filling with the German planes and

the panzer divisions set the country thundering and echoing like

an iron bridge. The squadron was always in retreat, based on one

airfield after another, closer and closer to Paris. When Peter

had a chance to take a look at the city, it was because his plane

had been shot out from under him, and he had to wait for a new

ship.

Those days of the fall of France were not like anything else that ever was on earth. A whole continent, twenty centuries of thought and being were burning like a grass fire, and yet there was a sort of gaiety in the air, a crazy, reckless laughter; for France, as she burned, cast a bright light. Time was the only thing that mattered—time for help to come from England, time to halt the Germans or time to escape from them. Money was nothing. People spent the savings of years in a day, and the night places were jammed. Napoleon brandy was the drink, and the oldest Burgundies and Bordeaux.

Peter wandered through the Paris night, watching the queer ways of people who are dying before they have been touched by death, for the soil of France is as close as flesh to the Frenchman, and now there were conquerors devouring the country, sacred name by name.

That night the Place de la Madeleine was jammed with people, so that the busses had to crawl through at a walking pace, their horns screeching. Peter was far out in the street, away from the curb, when he was passing that famous old restaurant, Larue's. A gay party from the place was taking taxicabs—men in white ties, women in dinner dresses and summer furs. But all he was seeing of them was one girl with dark hair and eyes as she looked up to the man beside her. The shock in his blood and in his brain made him dumb for a moment, but then he shouted, "Nancy! Nancy!" in such a voice that people twisted about to look at him.

The pressure of the crowd was too great to permit rapid motion. Peter struggled like a fly on sticky paper. He yelled her name again, waving his hand frantically, and now she looked directly toward him. Her eyes met his, dwelt on them, and passed him over without the slightest recognition. The next moment she had disappeared in the cab. He saw it move away through the crowd, cutting a way with its horn, and still he was shouting, helplessly far away.

He went hack to his hotel, bewildered, like a man walking between two worlds, for he had forgotten the hope of happiness.

At his hotel, when the concierge saw Peter's face, he was amazed. "Has the war ended for you, monsieur?" he asked. Peter had him put two men on the telephones to check every hotel in Paris where there was any likelihood that Nancy might stay. There was a surer way than that of getting her address. He tried to put through a call to Nancy's Aunt Olivia in England, who would be in touch with her, certainly, but, of course, he discovered at once that all the lines were pre-empted by the government or the military.

Then he thought of the newspapers. He could go to a newspaper and advertise.

On the advertising form at a newspaper office he wrote, "Leaving Larue's restaurant at ten last night was Mrs. Peter Gerard, five feet, five inches tall, dark hair, blue eyes, age twenty-two, wearing a black dress, a white summer fur. Two thousand francs reward for quick information giving her address."

When be finally got to the window to put in his ad, the clerk was reading out the notice turned in by the woman who had preceded him, his pencil checking the number of the words and his dull voice reciting, "Lost, one chow dog, answering to the name of Alex, soot-black around the muzzle, with a distinguished carriage."

The evening went by in confusion, like the shuffling of a peck of cards. In the Crillon Bar he discovered that alcohol once more had a taste and an effect. It was tremendously jammed and people were tipping with hundred-franc notes.

Midmorning of the next day. Madame Charent came to see Peter with a copy of his advertisement in her hand. She was a lean old crow, but she still dressed her feathers smartly. If one did not see the hungry evil of her face, she still had the outline and the air of any young cocotte on the hunt for men.

"You have seen my wife?" asked Peter.

"Wife?" said Madame Charent, and grinned horribly at him. "Yes, monsieur!"

Peter grew a little sick, but he could not have said why. "You know where she is now?"

"She is with me," said this hag.

Peter stared at her. It was impossible not to think certain thoughts that took the blood out of his brain and left him dizzy.

"Let us go at once, then," he said.

"Certainly, monsieur, after we have made our little arrangement."

"Will you tell me why you are sure that it is she?" he asked.

"Monsieur, she was last night at Larue's. She wore a black dress. She had a white summer fur. And she is five feet and five inches tall."

"And her name?" asked Peter, still strangely dubious.

"Monsieur, names are not people."

"What do you mean by that?"

"I mean that I am a busy woman. Do I return alone or does monsieur come with me?"

He put two big, garish thousand-franc notes into her hand, which closed hard over the money to digest its meaning. Then she took him to the house.

It was a mansion not far from the Étoile, four tall stories of dignity under a classical cornice, and half a dozen expensive cars parked up and down the curb seemed to go with it.

"Monsieur Henri Lavigny's house," said Madame Charent. "His widow is studying ways of forgetting him."

To illustrate her point, a burst of laughing voices, men and women together, came ringing from an open window through the warm June air.

They went into a great entrance hall paved with a checkering of black-and-white marble, and the eyes of Peter touched on a pedestal that supported a Greek head in marble, a girl's head with a pathetic, mutilated smile; nothing else entered his mind except the sense of cool space as he went up the grand staircase with Madame Charent.

"They are all in madame's room," she said, as they entered the upper hall. "She doesn't sleep well, except when she has company. So she keeps around her the people who have lost.

"Lost?" asked Peter.

"Yes, yes," said Madame Charent. "You meet them everywhere today. Those who have lost an address, a country, a fortune or a wife."

She pushed open a door. Cigarette smoke misted the interior and a pungent fragrance like that of an expensive bar came out to Peter.

"One moment, please," said Madame Charent, and stepped into the doorway.

"Pardon, messieurs-'dames," said Madame Charent in a loud voice. "There has arrived Monsieur Peter Gerard, who has lost a wife. He believes that she is here."

A woman's voice said, "I don't recognize the name, but then, names are so variable. Has any of you misplaced a husband?"

There was laughter.

"Who is this Monsieur Gerard?" asked the woman.

"An English aviator, madame," said the porter's wife.

"A flier? Then bring him in and let the poor fellow see with his own eyes that she isn't here."

Madame Charent turned to Peter.

"You see, monsieur, that you are welcome; you are almost waited for," she said and, drawing him into the room, she closed herself out.

There was a mist of smoke, and beyond the mist a dazzle of sunshine slanted from a window, and beyond the dazzle sat his wife. The rest of the world was lost to him. If the moment of coming death floods the mind with a swift montage of the life that is about to end, then this instant was the end of dying, and as he looked toward Nancy the saddest moments of his grief since be had lost her came back in pictures now made rather beautiful because this joy was in the ending.

In this way, blindly, for a second, be was drifting out of unhappiness into a glory; but then reality returned and he saw that the girl found nothing in him. She had looked at him and her eyes were passing on, and to her he was nothing.

The pain from which he had almost escaped poured back through the familiar channel in his heart. The room closed around him.

There were seven people, still in dinner clothes, and two servants. In the bed, against a heap of pillows, reposed Madame Lavigny in a nightgown ruffled about the throat and sleeves. A crisp little maid leaned over the bed to brush the hair of her mistress. Madame Lavigny was in her early thirties, still pretty, though somewhat damaged about the eyes. By dieting and exercise, she had scrupulously adhered to her original lines. She said, "I'm so sorry for your loss. Won't you rest here with us a while?" She held out her hand.

Peter, all trembling, kissed the hand. Yonder by the window he had seen the bright ghost of Nancy again.

"You are overwrought, my poor friend," said Madame Lavigny kindly. "Perhaps we can help you a little, because we are trying to pretend that nothing matters.... Hal, introduce Peter to everyone.... Gaston, some wine for monsieur." Hal was an Englishman of fifty, silver-haired, lean and hard of face. He had the sardonic air of one who observes life without sharing in it. He shook hands with Peter, his eyes touching intelligently on the barred ribbons which decorated Peter's uniform. He began to speak with an impersonal detachment.

There was a blond girl with a smile that kept persisting as though through the force of a life habit, though her eyes were emptied of happiness.

"This is Elsa," said the Englishman.

"How do you do, Peter?" she said, and looked at him with a mournful touch of hope that died instantly.

"We have decided to use first names only," explained Hal, "in the short time that's left to us.... Elsa has left a title and everything but a few family jewels behind her in Leipzig, because at the last moment the Nazis discovered just how anti-Hitler she is.... And this is Sonya."

Sonya was dark, with high coloring and an ugly intelligent face. She stood up to shake hands. "I'm very happy to see you. My brother also, it was in the air that he was fighting," she said.

"Sonya is Russian, of course," said Hal. "She and I are old friends of Madame Lavigny, but now there is no difference between old and new, because there is a very near and dear fraternity of pain.... And here by the window is someone we find so lovely that it is extremely difficult to see, at times, the shadow that goes with her brightness. This is Adrienne."

He was bowing to this strange duplication of Nancy.

"How do you do, Peter," she said, and the voice also was familiar, yet it did not seem quite Nancy. It lacked something, he felt, of the clear small music of that voice, which, over a telephone, sounded like a child, desolate, lost. Or perhaps he was too shocked to hear clearly, for the girl looked at him without the least recognition. Was not this Adrienne older also? And even while smiling she established distances between herself and the world. His voice stopped in his throat. He could not speak.

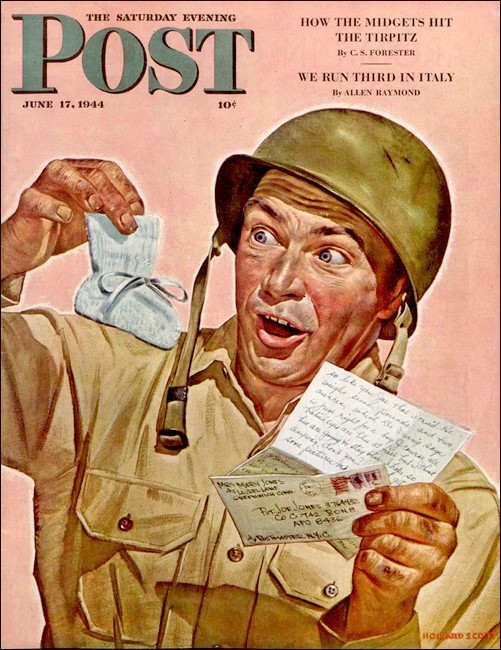

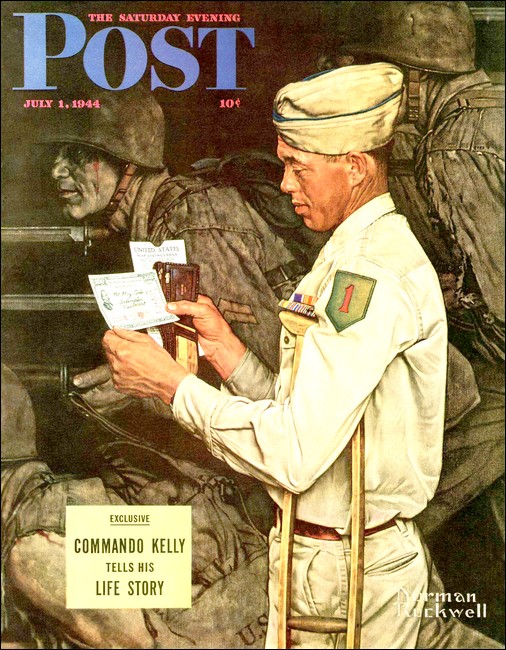

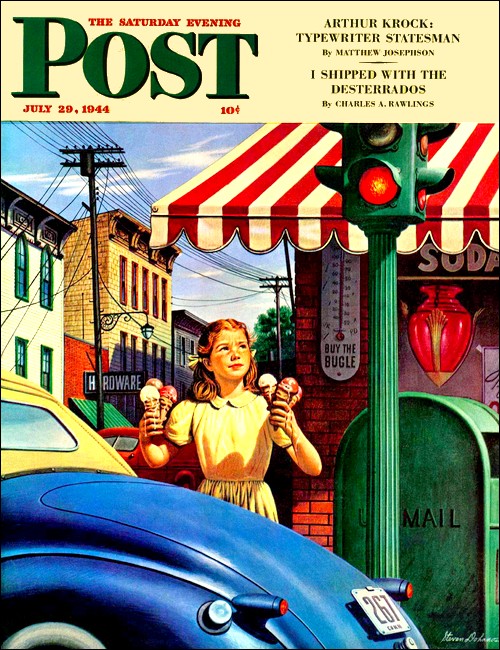

The Saturday Evening Post, 17 Jun 1944, with 2nd part of "After April"

THE Englishman continued kindly, covering his silence, "The two hundred and twenty pounds yonder drinking champagne out of a tumbler—that handsome young man is Jimmy. He is a football hero; he sells automobiles, and he practices yoga so be can drink more champagne and have smaller headaches. As for me, I am the skeleton at the feast. If there is beauty, there ought to be also a beast, don't you think? But I've almost overlooked André. He is a racing driver, a little too rough to win many races."

Being much the nearest, André shook bands with Peter first.

"Be careful of him, Peter," said Madame Lavigny. "He sometimes breaks fingers, he's so rugged.... Aren't you rugged, André?"

André grinned at Peter. "Very happy," he said, and bore down with the full force of his grip. But there is a trick, in shaking hands, of holding out the forefinger and pressing it against the wrist tendons. Peter had learned it years ago from his fencing master.

"Damn!" said André. "So you know about that?" He laughed very cheerfully. "This is a real one," he said.

"Of course he is," said Hal. "Unhappiness is always real. How do I know that I am, that I have being? Well, sir, in spite of Bishop Berkeley, let someone step on my toe and all doubt leaves me. I suggest that you talk to Sonya. She is real, too, and sorrow kills sorrow, you know. Like cancels like."

The manservant, who wore a crisp white coat, gave Peter a glass of champagne as he remained standing beside Adrienne at the window.

"Nancy," he said.

A small ripple of shadow ran over her face. "Nancy?" she echoed, with a touch of concern.

He had counted up the differences between her and that which was lost to him, and yet the similarity remained so overwhelming that he could not believe in a chance exquisitely cruel as this nearness which, it seemed, was merely cold illusion.

Nothing rose in her eyes to greet him as he showed her a golden medal struck with the bearded head and the name of the great Admiral de Ruyter. It was a little twisted, and marred with a sharp indentation. "Do you remember?" he asked. "Nothing?" She shook her head as she looked. The big American was quite drunk. Now he stared at Peter with huge, solemn eyes.

"He thinks she may have forgotten him," he said. Someone laughed, but Madame Lavigny said, "Hush, hush! No one, please, be unkind."

From the corner of his eye, Peter could see her touch her finger to her forehead. They thought him out of his mind. Now this Adrienne was humoring him.

She looked up at him with the kindest eyes in the world, saying, "Sit down here in the window seat, please, and talk to me."

He sat down as a woman in the street below began to scream, not wordlessly, but with such a rapid flow of protest that not a syllable was clear.

"Quick, Hal," said Madame Lavigny. "Drown her out with the radio."

The Englishman spun the dials, and after an instant a loud voice exclaimed from the air, "The planes of France are swept from the sky. The Maginot Line now is helpless, taken from the rear. Our brave armies are dashed to pieces by a metal monster. Paris is declared an open city. Our time grows short, but, nevertheless, let it be glorious. The final judgment on a man or a country is not how we live, but how we die."

Hal snapped off the radio quickly, but Madame Lavigny already was weeping silently. "I'm very sorry," said Hal.

"You have reason, monsieur," said the maid, looking at him almost with hate. "She's started again, and may God tell me what to do now!"

"Give her more air," said Jimmy.

He went to the bed, and in his enormous arms swept up Madame Lavigny together with the bedding that covered her. This bundle he walked with, lightly, up and down before the windows. She kept sobbing with bitter, hopeless grief.

"There, there, honey," said the giant. "Don't you be worrying too much, but just let yourself go. Let go all holds. Henri's not in the room, but he may be mighty close to us. Why, Louise, a man's out of sight the minute be just steps around a corner, but the thing that counts is knowing what a fellow is, not where he is. Jimmy's going to take you out to Texas, where there's two- three hundred miles for your eyes to handle of a morning, and he's going to put you on a rocking-chair mustang and ride you right into the blue of the hills where you can't tell how the mountains leave off and the sky begins."

The maid had been following as her mistress was carried back and forth. Presently, she said softly, "She is asleep. Monsieur Jimmy, and God reward you."

He took her back to the bed and laid her down gently. She remained deeply asleep, one arm falling out helplessly beside her.

"Shall we go now?" asked Sonya, whispering.

"No, no," said the maid, "but keep on talking or she'll be awake in a moment again."

Adrienne had been following all this with an interest so intense that her face was open to the study of Peter, and by this time be had looked into her as deeply as into a well. She began to give him her attention again.

"You seem better now," she said. "Aren't things beginning to clear up for you a little?"

"May I ask you a few questions—Adrienne?" he asked.

She smiled at him as though pleased to hear him use the name. "None of us asks questions here," she said gently.

"It's only to find out to whom you belong."

"Oh, Peter, must we all be owned by someone?"

"I mean your mother and father?"

"Everyone in my life is dead."

"Adrienne?"

"Yes, Peter?"

"If I speak to you about your uncle and your Aunt Olivia in England, does that mean nothing?"

"You terribly want it to mean something, don't you?"

"Yes, terribly."

"And it seems to you that once we were very close and dear to each other?"

"Yes, so it seems."

"I'm so, so sorry," she said, with infinite kindness.

He was unable to speak, and, as though she could not endure his pain, she put her hand over his.

He heard Elsa saying softly, "André, when they reach me, will you promise to be close?"

"Yes, always."

"And they're not to have me? You will make it so that I die?"

"Yes, yes. Elsa."

The moaning voice of Madame Lavigny said, "Poor Peter, he also has lost something forever. He must bring his things and stay with us here."

"I shall be very happy to," said Peter, rising.

"Then I can sleep again," she sighed, and closed her eyes.

"If I take my eyes from you," said Peter to Adrienne, "you won't dissolve in thin air? I won't lose you?"

"I'll stay flesh and blood, I promise," she answered, trying to smile.

IT was not easy to move in Paris that day. Peter had thought

of rushing to his hotel and quickly back again, but even in the

last hour there was a change and the whole population seemed to

be pouring into the streets in flight.

Loudspeakers in the squares, here and there, were bawling out details of the fall of France. The panzer divisions were everywhere. The German army had become ubiquitous throughout the land and the world was falling in ruins. Peter found himself struggling against strong currents of people who had in their eyes a vision. It was a long time before he found a taxi stopped in a traffic jam.

The taxi drivers of Paris are a race apart. They are only half French and the rest is pure devil. Rain cannot penetrate their hides, wine cannot make them drunk. They have the voices of foghorns, the manners of pirates, and, like cats, they can see in the dark. This fellow Peter had found was like a cat with a shaved face. However, he got Peter to the hotel, where he packed his bag and then found nobody at the desk to receive the money for his bill. He put a generous amount on the counter, and, even as he was turning, saw it snatched up by another hand, but that hardly mattered. Perhaps before long in this dissolution of the universe he would stop making even the gesture of honesty.

He was back in the taxi now, passing a hundred francs to the driver to encourage him to hasten. But there was no need. Inspired, the man blasted holes in the thickest traffic with his screeching horn. Even so, they were at a crawling pace most of the way, and thought came back into the mind of Peter. This land, famous for beauty, was to be possessed by Germans, just as Nancy was now possessed of another name and soul. However, there is in this world courage to endure and love that may heal.

When he reached the house of dead Henri Lavigny, he saw the front door standing wide open, and somehow this was a curious shock to him. He asked the driver to wait, and hurried inside. The wind passed before him into the lofty hall. In a panic now, be ran up the staircase to the room of madame.

It was empty. It looked as though a looting army already had passed through. Chairs were overturned. The great pier glass which had held the beauty of Louise Lavigny so often was cracked across from top to bottom, and the clothes of the bed slumped in a long twist onto the floor. Drawers had been jerked open, a hundred small objects littered the room, and the chair by the window seat was empty.

He fled out of the room, down the hall, down the stairs with a wild voice that rang in his ears, calling, "Nancy! Adrienne! Nancy!" But it was unlike any sound he had ever uttered before. To have lost her once was nothing, but this was forever.

On the lower floor, he turned back into the house, through a great formal drawing room with a silk Persian rug on the floor, then into a state dining room, where he found the same butler who had been serving the guests in the room of madame. He sat now with a wine cooler at his side and two bottles in it. On a silver platter before him was an omelet, and be was serving himself a portion of it onto a plate of white, exquisite china. He did not look up.

"They are gone? All?" cried Peter.

"All," said the butler, and took a good bite of the omelet, which he savored with care.

"Have you a ghost of an idea where?" asked Peter.

"Where?" asked the butler, and dismissed the idea with a shrug.

Peter dropped a handful of paper money beside the man. The fellow blew on it, and when it floated to the floor he laughed.

"To a new world, monsieur," he said, and drained a glass of the champagne.

Peter ran from the room and the house. His taxi driver, with a raised monkey wrench, was keeping back a crowd that wanted to enter his cab.

"Where are they going? What road are the people taking?" Peter asked him.

"South, on the Bordeaux road, monsieur," said the driver. He laughed, totally at ease. "This is like the Marne in reverse."

"Bordeaux, then," said Peter, committing himself to the gamble.

THAT road to Bordeaux was a picture of the end of the world.

There was no place to flee, but all France was fleeing, five

millions in Paris, three millions took to the road, and most of

them seemed to be on the way to Bordeaux.

There were automobiles of every size and kind; there were wagons, trucks and the huge, clumsy carts drawn by the stallions of the peasants; hayracks appeared, loaded with the goods of a whole family, even including the stove; dogs had packs strapped on their backs; there were handcarts with the man pushing at the handles, the wife and children tugging on a rope ahead.

The driver stopped his car. "There is no use, monsieur," he said.

"The traffic will clear presently," urged Peter.

"Listen, my friend!" said the driver, holding up a finger for attention, and far up the road into the horizon, chorus after chorus, Peter heard the horns singing out in protest. The jam was thick as far as yelling horns could be heard.

"Now we have the real democracy again," said the driver. "And every man does better on foot."

"I think you're right," said Peter, and paid three times the bill.

"Thank you, my friend," said the driver. "But if I were you, I would get out of that uniform. You see?" He pointed up, and high, high against the upper clouds Peter saw a great wedge of planes flying in threes. Into the motor uproar along the road the noise of the huge engines descended hoarsely, like the calling of wild geese on an autumn day when all the countryside lies asleep.

For hours, Peter struggled up the edges of the road or through fields beside it. There was not one automobile that he could afford to miss, for in the one he skipped might be Adrienne.

It was nearly five o'clock when he found her. She was almost lost in the rumble seat of a big roadster driven by Jimmy, the American, and at Jimmy's side was Madame Lavigny. Peter stepped on the rear bumper, and the girl turned her head to him with startled eyes. But a moment later she was smiling and holding out her hand.

"How have you found me?" she asked.

"Because there is something that keeps us from being too far apart," he said.

"Oh, is that it?" she said, shaking her head sadly over him.

"You still think that it's all illusion?" he said.

"We won't speak of it. The war gives visible and invisible wounds," she said, "but in all this dreadfulness, you and I will be kind to each other, won't we?"

"Yes, Adrienne. Yes, my dear."

She shrank from the word. She went on, "And if I say the smallest thing that gives you pain, will you tell me?"

The misery of speaking to the new ghost that now inhabited her was too much for him. He broke out, "Adrienne, isn't it possible for you to look back and remember something?"

"Do we have to look back?" she asked.

"Not if it makes you unhappy. Nothing that makes you unhappy."

"There is today, and isn't that enough?"

"Yes," he said. "Then that makes everything all right, so long as I'm here with you."

"Will that be half enough?" she asked, with such a wistfulness that his heart gave a great knock against his ribs.

"It must be. I shall make it enough," he said.

"And no questions, please, please?" she begged.

"There are no questions. Nothing matters. Everything else is gone."

"How kind you are!" she said. "How lovely and kind! No one else has been like this."

She looked more like Nancy than ever, for no matter how quick the flight from the Maison Lavigny had been, they had had time to change, and now she wore a gray suit of light summer tweed with a scarf of airy red chiffon about her throat.

"Don't you want this seat?" she asked, pointing to the place beside her.

Jimmy turned from behind the wheel and shook a finger at them.

"Steady; voices may wake her," he whispered.

And Peter saw that Madame Lavigny was soundly asleep, as though the frantic chorus of the horns were a soothing lullaby.

"I was so sorry to run off," Adrienne was explaining, "but the radio news became frightful all at once, and everybody wanted to leave. I simply blew along with the others, like a leaf."

Just ahead, voices shouted, and then, like sirens running up close to the ear in a nightmare, three dive-bombers screamed down out of the sky—straight down, it seemed. They flattened out, machine guns began to rattle like riveting machines. They were gone overhead, so close that Peter could see the smile of a pilot. After that, the automobile horns were silent as chickens after a hawk has swooped on the henyard, but from the swath which the Nazis had cut along the traffic, voices began to cry out in agony.

It was a fine, intimate taste of horror, and yet it meant wonderfully little to Peter compared with what he had seen in Adrienne during the attack. People had been throwing themselves out of cars to the road, crawling under the machines, regardless of the fact that long before they had found shelter, the attack would be past them at three hundred miles an hour, but Adrienne, with an odd smile, had sat up and watched the murder with a sort of bright interest. Nancy, who had been so timorous, what would the real Nancy have done? Another thought began to chill the blood of Peter, for just as he himself had flown against the Germans with a smile, because they could do him no further harm, so it seemed to him that there was the same cold heart behind the smile of the girl as she watched the machine guns spitting their rapid tongues of fire. It was mere illusion, be told himself, but he knew that it made of this moment something he never would forget.

"The thing to do is to try it on foot," said Peter.

"I wonder," said Adrienne calmly.

"We ought to get away from the main road and follow the side lanes that travel in the same direction. There might be even a lift for us, now and then."

She looked at him intently, patiently trying to read something in his face.

"I won't be bothering you with questions, Adrienne," he said.

"No, you won't, will you?" she decided. "Then I'll go.... Jimmy, good-by."

"Hush," Jimmy whispered. "She's still asleep. Can you beat that?"

THEY walked down crooked lanes that vaguely wound toward

Bordeaux among the thrifty fields of France and under spots of

shade from the pollarded trees which, every year, gave up their

crop of firewood. Nearly the whole way was deserted, except when

a stray automobile, now and then, rushed past them and left a

mist of dust in the air, slowly settling. And yet the fear of the

Germans had preceded them, and several times they saw, vanishing

far off on some other side way, the carts of peasants, hugely

piled with their belongings.

Adrienne, whether she thought him touched in the mind or not, had come to accept him in the most cheerful and friendly manner. And when he looked back upon it, he felt that there was something touching, something greatly surprising in the way she had left Jimmy and gone with him. She managed to maintain her smiling, though he could not be sure whether it was a sort of desperate indifference or real courage. And every moment he studied her, his assurance that she was Nancy grew dimmer. The resemblance that had seemed so absolute at first, now was by no means so complete. Every moment his heart was lifting in recognition or failing again in doubt.

The day grew old. The sun stretched their shadows longer and longer down the white road before them when she asked if they could stop for a moment. A clear little rivulet flowed across the road under a culvert, and Adrienne, sitting beside it, pulled off shoes and stockings and dipped her feet in the stream. The skin was chafed red; a round raw spot was on one heel.

"But you haven't been limping," said Peter, sitting on his heels to look at the damage.

"Limping? Because of this?" she said, and laughed a little at the thought. "Of course not."

He looked up at her, remembering how the best of soldiers will straggle when they are footsore, but he said nothing. His mind was too full of the realization that Nancy hardly could have had the grit to act like this.

"We can't go on far with your foot in this shape," he said. "There's a peasant's cottage over there. We'll see if they can put us up for the night."

Luckily, he had a perfectly fresh handkerchief of thin linen, and after he had tied it over the chafed heel, she still was able to draw on her shoe.

They came up through the barnyard of the cottage, of hard- compacted dirt with an ancient pump on a wooden platform in the middle of it. It was time for chickens to be at roost, but several of them were picking about here and there, and at the sound of footfalls, a dozen more flew down out of a shed and came cackling about them. A moment later, cows were mooing in the barn.

"What's the matter with this place?" asked Peter.

"I don't think there's a soul here," she said.

"But I see a light." he pointed out.

They went to the window and looked into a dimly-lit bedroom with a great old-fashioned bed built into a corner and in the opposite wall a crucifix in a little niche with a candle, down to its last quarter of an inch, burning in front of it.

They went back to the kitchen door and knocked. The echo walked briefly through the house and was still.

"No one here," said the girl, and pushed the door open.

In the kitchen there was a stove, a heavy wooden table, scrubbed white, two chairs, a bench, and on the walls a pair of gay posters, relics of the last World War, and now kept, probably, rather as decorations than as mementos.

"Hello, hello!" called Peter.

He crossed the room and opened the next door into a sort of parlor with a faded carpet on the floor, some family photographs under glass on the wall, also a memorial wreath in wax. There were some stiff little chairs with plush seats badly worn, and on a center table there was a strip of cheap brocade on which rested a few books sustained by a pair of brass book ends.

"Not a soul, not a soul here," said Peter, and only discovered then that the girl had not followed him.

He found her in the bedroom, lighting a fresh candle at the weltering flame of the old one, and he watched her put the new taper in place.

The glow of it was now stronger than the daylight, and it stained her face and hands with rosy gold. Her fingers, he thought, were thinner than the hands of Nancy.

"They've run away," she said, when she felt the eyes of Peter on her. "They ran so fast they even left money behind them. I found this on the floor." She held up a fifty-franc note. "Besides, look on the kitchen stove," said Adrienne, and led him back to it.

She lighted a lamp that rested on a wall bracket, and then he was able to see the black iron soup pot, a third full, with a crust of white grease over the liquid; and a smaller pot that was full of dark beans. On the table, part of a loaf had dried hard.

"They were just about to eat," said Adrienne. "Soup and beans and bread."

Peter looked into the shadowy soup pot with a face of disgust. "Horrible," he said.

She took a big iron spoon out of a table drawer and scraped the upper white layer from the soup.

"Delicious!" she said. "Carrots and small onions and herbs and good beef stock. It just hasn't been clarified yet. Let's see what's the matter with those cows; they're making such a racket, they probably need to be milked. Can you milk a cow?"

"Everybody in Holland can do that," he answered.

She was rolling up her sleeves, then taking a gingham apron from its hook on the wall.

"There's a lantern on that peg," she said. "Will you light that, and then we'll see what needs to be done."

She went briskly on the rounds with him. There was a little creamery room adjoining the kitchen, and in it stood a cooler made of burlap drawn over a frame, so that water from a pan on top could siphon down over the cloth and keep the contents of the cooler chilled. The siphon rags were dry, and on the shelves inside several pans of milk had soured.

"What a waste!" said the girl, sniffing.

But she gathered up a small round cheese while Peter refilled the water pan. Then they went into the barn. It was very old. The lantern light floated up among great beams that were sagging in the center from the weight of centuries. From the mow, which was half filled, came the ineffable sweetness of hay. And above an empty manger, two cows in head stalls stopped lamenting and looked with great expectant eyes toward these humans. Beyond them was a gray mule with eyes that turned green in the lantern light, and past the mule was its harness-mate, a pleasantly fat brown mare.

The cow's swollen udders made Adrienne exclaim. "Poor things," she said. "Hurry, Peter. There's a pail back there in the dairy room. You take care of the livestock—and you won't forget to water them, will you? I'll rouse up a fire and start supper."

He worked busily for an hour, milking, stowing the milk in the broad-faced tin pans of the cooler, then laboring at the big handle of the pump until the small trough beside it was full. The cows alone drank it dry; the mule and the horse consumed a second filling.

When he had finished his work, he came back through the barnyard and stood a moment to breathe the odors of the fields. Adrienne began to sing a little French nursery air. He listened with a great, hungry query in his mind, but so far as he could remember, he never had heard Nancy sing during their brief weeks together.

He went slowly into the room. She was flushed with the heat of the stove, and the savor of good cookery filled the sir. In a skillet, an omelet was browning through its last delicate moments; two bowls of thick kitchen-ware stood on the table, filled with steaming soup; there was a display of cheese and bread broken into chunks, and two glasses beside a bottle of white wine.

She displayed the bottle on high. Suddenly his heart filled so full that it almost burst. He could not speak.

"Poor Peter, what is it?" she asked anxiously. "What has gone wrong?"

"May I say it?"

"Yes; whatever will help you," she said, and came up close to search his face.

"Then tell me how could God, if there is any kindness in Him, make two women so like?"

"Is it terrible for you? To keep seeing me and thinking of her?"

"It makes me take a deep breath now and then. That's all," be said.

"But you're holding fast to one thing, aren't you? You know now that I'm only Adrienne?"

"I try to know it, but I'm still half blind," said Peter.

"You're so kind, so good and so dear to me that I wish I could help you and that poor, poor girl."

He took hold of himself strongly. "But there's nothing to do," he said, "and the omelet is overcooking, the wine is getting too warm, and Adrienne can't be an angel forever." He hastened to pull up her chair on the far side of the table. He uncorked the wine and poured for them both. "To happy endings!" said Peter, and they drank.

THE soup was strong and full of good savors. They drank it and

he watched her way of handling the bread, not daintily, as an

English girl like Nancy is taught to do, but with a more honest

and hungry abandon, such as one sees in Continental table

manners. The omelet came on then, done to a turn.

"Adrienne," he said, "you are a chef—a Cordon Bleu. I salute you."

They had a coarse green salad with cheese. Then coffee, the bitter French coffee, perfectly made, blacker than the River Styx. As they sipped it, she took one of his cigarettes and they smoked together. Nancy never had touched cigarettes, but Adrienne breathed tho smoke in deeply, like an addict.

After a moment she covered a yawn. "I can't sit up long," she said, "but if I lie down in there, will you come and talk?"

"You should sleep."

"No, I'll rest enough lying flat."

Once she was stretched on the great bed in the adjoining room, she groaned softly. She lay with her arms thrown out and her eyes closed while the waverings of the candlelight flowed dimly over her face and her smile.

When he had drawn up a chair beside her, she said, "Now tell me about Nancy."

"I'd better not start on that."

"The more you talk it out, the more you'll see the differences between us. It will do you good. There are no troubles that words can't help—except for sore feet," she added, and chuckled a little.

"Do they burn like fire?"

"No. Not really...." Her voice had grown slower.

"I think you could sleep," said Peter.

"No, I'd like to lie just this way and taste the sleep that's going to come. The falling asleep is the thing, not the sleeping.... Do you know something?"

"Yes, I know that this is happiness."

"For me too," she said. "I don't suppose there are ten acres in the farm, but I think that would be enough to make a life for me.... Tell me how you first saw her, Peter."

"Were you ever in Rotterdam?" he asked. "It was on a Rotterdam pier. There was a breeze—the kind that only blows in April.... What is your favorite month?"

"Should I say April?"

"Yes, if you please,"

"All right. April is the loveliest month in the year."

"Yes, because it's the time of the returning year. One day the trees are still black as iron, and the next, there are level streaks of green in the branches. She was like April. With a promise in her, you know? Now, you, Adrienne, you are really beautiful, but Nancy was only pretty; she seemed barely started in life, almost transparent. If you looked in her eyes steadily enough, you could see her soul."

"Her whole soul?"

"Yes. All of it.... Do you draw or paint or anything like that?"

"No, not a bit. Did she?"

"She was sitting on the pier doing a color sketch of the laundry that had been hung out on a barge. She was trying to put in the swing and slant the wind gave the wet underwear. That was when I met her." He paused, thinking back.

"And then?" she asked.

"She was a tourist, and presently she had to catch a train, so, of course, I offered to take her in my car. When she saw it she began to laugh. It was one of those gas-savers, no bigger than a beetle. But I told her that one day it might grow up, and already it could find its way about."

Adrienne laughed. "I like that," she said.

"Well, I managed to make her miss the train by pretending to believe the time that an old clock was telling—the hands hadn't moved for a hundred years. And I got her into the old church where other Peter Gerards were buried six hundred years ago. But at last we were there on the station platform, with the train disappearing down the track. I think I'd better stop there."

"But why?"

"Because I remember how she stood there on the platform and looked up to me like a frightened child, and how my heart gave a tremendous knock against my ribs. I could hardly speak out loud, I was so busy vowing to love her and keep her and care for her forever."

"Yes," whispered Adrienne.

Peter, astonished, saw that tears were appearing on her face. He sprang up and leaned over her.

"Nancy! Nancy!" he cried. "Have you come back to me?"

"No—hush!" said Adrienne, without opening her eyes. "But it hurta me terribly when I hear about you two, because then I see—"

"What is it, Adrienne? But you've been in tears."

"It's only that I see how much you've both lost.... But would she always have been like that—like April to you always?"

He thought back before he said solemnly, "Yes, always. There was a spirit in her, Adrienne, that never could be changed."

THE parlor couch was as hard as a road, but on it Peter fell

sound asleep and dreamed once more of the Holland sky, with great

white clouds sailing through it barely over the church steeples.

But it was still thick night when the sleep left him like a dark

cloth twitched from his face, and he lay for a moment looking up,

a sense of ruinous disaster aching in his nerves.

He stood up and looked from the window. In the east, the first pallor of dawn was commencing, by no means as bright as the stars, and the chickens had not yet left their roosts.

He took a lighted lamp through the kitchen and tapped on Adrienne's door. The moment he had done it he was sorry, because when her voice answered, there would be nothing for him to say unless it was to confess that he had waked up in the night like a child, afraid. But, in fact, no answer came. He rapped again, then hastily pushed the door open and found no Adrienne. Nothing lived in the room, except the last gutterings of the candle-flame under the crucifix. She had made up the bed neatly. On the table she had left two hundred-franc notes for the peasants, if they returned, and the money gave him assurance that she was gone.

The first pink was staining the east when he left the cottage and stepped out into the empty world. Now the sun was rising; the chill of the night left the air, and from a hill's low crest he saw a cart in the next hollow, the driver on the seat, a woman in peasant costume on top of the load of hay. There was no Adrienne.

A baby Austin paused beside him, a bearded man at the wheel.

"To Bordeaux, monsieur?" he called.

Of course be accepted gladly. For where would Adrienne be heading except to Bordeaux?

The owner of the car was a Jacques Cordier, middle-aged, ebullient, like a man traveling toward a lifelong happiness. He began to sing as he started up his car, and stopped his song to apologize.

"This is a sad time for our beautiful France," he said, "but it is release from prison for Jacques Cordier. In Rouen I have a factory and put metal caps on shoelaces—a business that comes to me with a childless wife. Instead, I have a brother-in- law with five terrible infants. But now, thanks to Herr Goering, the factory is gone—pouf! My miserable people have fled to Dijon. May the Germans be there soon and pull the whiskers of my brother-in-law, and let me die for my country in peace. The planes fly over, the bombs fall. I stand in the open and hold up my hands like a peasant in summer praying for rain. Quickly, I am blessed. First on the engine-house, crash! It is gone. Then on the machine-shop, bang! And they are gone too. I come home, I laugh, I drink some good red wine, I swallow some excellent Roquefort. 'Madman!' yells my wife. 'Fool and thief!' screams my brother-in-law. 'Do you not see that this is the end?' 'My dear friends, my loved ones,' say I, 'do you not see that it is the beginning?' So they are behind me, and I laugh and sing. That Normandy is behind me also, the curse of Saint Martin upon it. There is a Norman mold that grows in Norman cellars, a Norman cold that breeds in Norman walls, a Norman wind that moans and howls like a dog all winter long. Adieu, Rouen; forward, Jacques Cordier!"

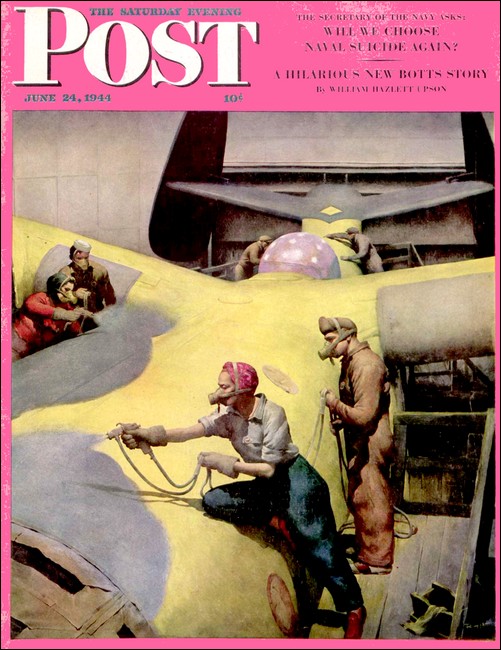

The Saturday Evening Post, 24 Jun 1944, with 3rd part of "After April"

THAT evening the rumors flew through Bordeaux that the cabinet had resigned; Raynaud was out, Pétain was in. Into Bordeaux, a city of two hundred and fifty thousand people, three millions were packed, and the three millions cheered the name of Pétain. "He will do something, that Pétain," they said. Other rumors multiplied. Churchill had come in person and promised an English division a day until the German tide was checked. The Americans would help all they could. There was still hope.

Other rumors poured on the heels of this—Pétain had offered to surrender France, had ordered the French army to cease fighting. It was news more terrible than the German bombs which began to fall on the harbor that night.