RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a public domain wallpaper

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a public domain wallpaper

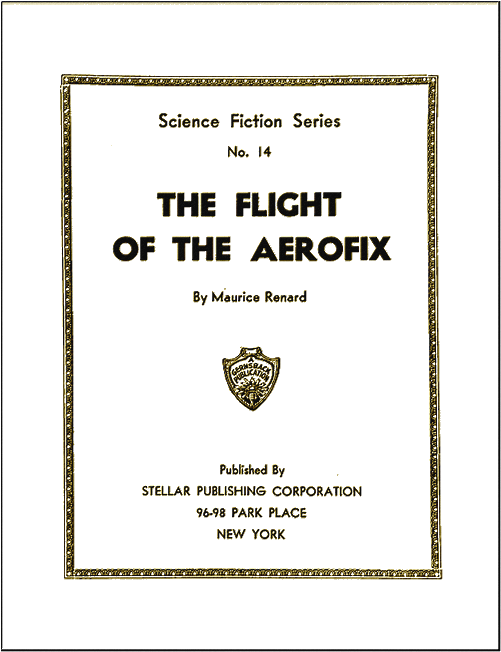

"The Flight of the Aerofix,"

Stellar Publishing Corporation, New York, 1932

This book is one of the following series of chapbooks issued between 1929 and 1932 by Hugo Gernsback's Stellar Publishing Corporation, New York.

1. The Girl from Mars by Jack Williamson and Miles J. Breuer, 1929

2. The Thought Projector by David H Keller, 1929

3. An Adventure in Venus by Reg Michelmore, 1929

4. When the Sun Went Out by Leslie F Stone, 1929

5. The Brain of the Planet by Lilith Lorraine, 1929

6. When the Moon Fell by Morrison Colladay, 1929

7. The Thought Stealer by Frank Bourne; The Mechanical Man by Amelia Reynolds, 1930

8. The Torch of Ra by Jack Bradley, 1930

9. The Thought Translator by Merab Eberle; The Creation by Milton Mitchell, 1930

10. The Elixir by H.W. Higginson, 1930

11. The Valley of the Great Ray, Pansy E. Black, 1930

12. The Life Vapor by Clyde Farrar; Thirty Miles Down by Drury D. Sharp, 1930

13. The Man from the Meteor by Pansy E. Black, 1932

14. The Flight of the Aerofix (1909) by Maurice Renard (anonymous translation), 1932

15. The Invading Asteroid by Manly Wade Wellman, 1932

16. The Immortals of Mercury, Clark Ashton Smith, 1932

17. The Spectre Bullet by Thomas Mack; The Avenging Note by Alfred Sprissler, 1932

18. The Ship from Nowhere by Sidney Patzer; The Moon Mirage by Raymond Z. Gallun, 1932

Readers are advised that "The Flight of the Aerofix" contains racially-biased lanuage typical of the period in which it was written.

After a mysterious explosion, the crew of a yacht rescue a man from the Atlantic and hear his strange story. Number 14 of the Science Fiction Series chapbooks published by Hugo Gernsback.

TOWARDS ten o'clock in the morning, the man we had rescued opened his eyes. I was prepared to see the usual recovery, the feverish fingers passed across the brow and to hear "Where am I?" whispered in a feeble voice. Not at all. For some seconds the man who owed his life to us remained perfectly still, with a lost look. Then his eyes lit up with life and intelligence, and he lent his ear to the noise of the screw and the lapping of the waves against the hull.

Sitting up in his narrow berth he inspected the cabin as coolly as if neither Gastan nor myself had been there. We next saw him turn to the porthole to look at the sea, and then examine us one after the other with a stare as void of curiosity as of good manners, regarding us as if we had been pieces of furniture which had escaped notice up till now. Then, with crossed arms, he relapsed into a deep reverie.

To judge from his looks this stranger was a well-bred man, with handsome face and well-shaped hands; and his clothes, wringing wet as they had been, seemed those of a gentleman. So his behavior annoyed my companion and surprised me, although I had been long accustomed to see in Gastan himself nobility under the bearing of a yokel, and breeding misallied with an insolent manner.

But Gastan, seeing him at the same time quite well and yet so unamiable, waxed impatient.

"Well," he said arrogantly, "how are you now? Better, eh? You are better, eh? You are better?" he repeated, again and again, and obtained no reply.

"You are in luck's way," said Gastan. "Without us, you know, old buck—Well? Are you deaf? Can't you open your mouth?" he said angrily.

"Are you hurt?" I said, pushing my friend aside, rather to put a stop to his speech than to inquire after the health of our taciturn friend. "Tell me—are you in pain?"

The man shook his head and continued to follow the thread of his thoughts. My fears grew, and I exchanged an anxious look with Gastan. I don't know if the man intercepted it, but I fancy I saw the glimmer of a smile in his eyes.

"Do you want anything to drink?" I said.

Pointing at me he spoke with a queer foreign accent:

"Doc-tor?"

"No," I replied cheerily. "No, No!" And, as his eyes still questioned me:

"A writer," I replied, "an author. You understand?"

He made a gracious gesture of assent, almost a bow, and poked his chin inquisitively towards Gastan.

"I—I do nothing," the latter said with a laugh—"a man of leisure." Adding, in imitation of my own words: "a do-nothing, an idler. You understand?"

I watched the effect of our graciousness on our visitor's face, and then quickly I made a diversion.

"This gentleman is the owner of the yacht," I explained. "You are the guest of Baron Gastan de Vineuse-Paradol, who has picked you up. And I am Gerald Sinclair, his traveling companion."

But instead of giving us his name and status as I had intended him to do, the man reflected for a moment and then laboriously articulated:

"Can you tell me what has occurred, please? I have completely lost all memory from a certain point."

This time his intonation, agreeably incorrect, revealed itself as the English accent.

"Well," explained Gastan, "it was quite simple. The launch was lowered. The sailors fished you out."

"But before that, monsieur—what happened before?"

"Before what? You don't mean before the explosion, I suppose?" said my friend mockingly.

The man looked stupefied.

"What explosion, monsieur?"

I had a presentiment that Gastan was growing angry, so I intervened once more.

Then addressing the man with no memory I said:

"Monsieur, I will tell you all we know of your adventure. I hope that it will refresh your memory, and so enable you to give your host a complete description of the occurrence to which he owes the honor of your acquaintance."

NOTWITHSTANDING that I underlined the words "your host" with

look and accent, my listener did not wince. He knotted his hands

round his propped-up legs, put his chin on his knees, and awaited

the continuation of my story.

I went on: "You are on the steam-yacht Océanide, monsieur: owner, Monsieur de Vineuse-Paradol; captain, one Duval; her port, Havre. And you are safe. She is a fine boat, 90 metres in length. Her registered tonnage is 2,184, she steams her fifteen knots an hour, and her engines indicate 5,000 horsepower. There were only my host and myself, in addition to the crew of ninety-five, until we came across you. It is not much, as the yacht has twenty-four cabins like yours. But Monsieur de Vineuse's cruise, on account of its length, attracted no one but your humble servant. We are returning from Havana where my friend was pleased to choose his own cigars on the spot, so to speak. And so—and so—"

I quite expected to have made a great impression with that touch about the cigars, carelessly introduced, but I might have spared my breath.

"So, monsieur, our return journey was accomplished in peaceful monotony until three days ago when something went wrong with the engines. We had to stop. Today is the twenty-first of August; so it was the eighteenth. We set about repairing the broken coupling-rod on the spot, and the captain was desirous of profiting by the delay to strengthen the rudder. We were lying in 40° N. latitude, and 37° 23' 15" W. longitude, not far from the Azores Islands, 1,290 miles from the Portuguese coast, 1,787 miles from the American coast—just two-thirds of our journey, in fact—and we only started again at daybreak this morning.

"Now the day before yesterday—Friday, the nineteenth—we were walking up and down the quarter-deck, in the interval between our nocturnal meals, smoking in the moonlight. All the constellations, even the planets, seemed to glitter. There was a continuous shower of shooting stars, and on the inky background of the night their white traces lingered so long that you might have taken them for mysterious chalk-marks describing parabolas on the blackboard of the heavens.

"Absolute silence reigned. The crew was asleep. One heard but the dull sound of our india rubber soles on the deck planking. We were making perhaps our twentieth turn on the deck when a whistle came up from the far distance to starboard of us. Almost at the same moment we saw rather high up in the sky, and on the same side, a glimmer of light. It passed over the yacht, the whistling accompanying it. The latter grew louder, swelled, and then died away altogether.

"That, by the by, is the conclusion we formed almost immediately—that it was a meteor. The man on the watch agreed with us, although he had never seen anything similar during his thirty years of service; and the captain, who was called on deck by the whistling, inclined to the theory of a bolide when he had heard our explanation."

Then I looked hard at the man. He hugged his knees more closely, shut his eyes, and waited for me to continue.

"You can imagine," I went on, somewhat crestfallen—"you can imagine that the meteor supplied us with a topic for conversation. Each one of us held diverse views about it. I upheld a certain relation that had struck me between its rate of speed and the duration of the whistle; and Monsieur de Vineuse gave us his opinion—a perfectly feasible, but somewhat unusual one. According to him, the bolide, which we had so far thought to have burst from the sky, quite possibly may have come out of the sea; there was nothing to prove the contrary.

"To tell you the truth, the sudden, appearance of this body bearing straight for the ship had no doubt been disturbing, and we had given a sigh of relief to see the projectile pass so high above us; all the more that, at the very moment of our deliverance, its infernal whistling made us duck our heads, which is what your warrior calls 'saluting the ball'!

"In short, we hoped from the bottom of our hearts never again to have to undergo such experimental astronomy. But that did not prevent the phenomenon from reappearing last night somewhat later, towards one o'clock in the morning, with complications in other ways dramatic.

"Yesterday, Monsieur de Vineuse, who was growing tired of this idling on an empty ocean, under a sky full of dangers, gave orders that the business of repairs was to be carried on day and night. Relieved every two hours, a working party was set at the broken coupling-rod in the engine-room, and another in the launch at the disabled rudder. The latter had finished their job and were getting ready to climb back on to the yacht at the very moment when the strange bolide sounded its periodic whistle in the distance.

"ACROSS a sky as brilliantly luminous as that of the night

before, we all saw the pale light grow, rise, and glide towards

us. Monsieur de Vineuse said he thought it passed slower than

before, and in my opinion the whistling was deeper in tone and

less shrill.

"But all at once there appeared in its place, swift as a streak of lightning, a sun. It ceased moving westwards, and the whistling was lost in a terrific detonation. I felt as if an invisible fist had punched me in the diaphragm. The shaken air seemed to throttle me. I could feel the plates of the Océanide trembling. A wind got up, which died down almost immediately, and waves rose on the sea only to disappear in the same manner. Then we very distinctly heard a shower of things fall into the sea. One of them sank quite near the launch, rose, and started to swim; that was you, monsieur, clinging to the bolts of a sheet-iron door, a curious kind of sheet-iron, light as a feather, because it bore you up as you floated.

"You were picked up unconscious and, not knowing if you had been alone aboard the aerolite, the captain caused the launch to search over a radius of two miles.

"As you were still unconscious, notwithstanding our care, we undressed you, put you to bed, and watched over you during the search.

"And now—shall we be allowed to know whom we have the honor of entertaining?"

The man wagged his head but made no reply.

"And the metal plate?" he said at length. "The floating plate, and the fragments?"

"Well," said Gastan, "they remained behind on the spot where you took to the water. Duval, the captain, decided it was ferro-aluminum, and of such poor quality that it was not worth taking aboard."

The stranger smiled openly, on seeing which my friend assailed him in a tone of cheery remonstrance:

"I say, tell us your little game, won't you? We won't give you away! It was an airplane, what? It was your airplane that burst, wasn't it?"

Then the other in his queer, clownish jargon said:

"Monsieur le Baron," he said, with slow utterance, with extremely little ceremony, "Er—your desire is—er—that I should explain why I am here—uninvited, and how and why. For now I—er—I remember everything very well. But before the recital, permit me, Monsieur le Baron, that I—-er—if you please, I am hungry—that is to say, I have a splendid appetite. Have you got my clothes?"

"Your own duds are not dry," said he, taking it for granted that his slang would be understood. "For the matter of that, they will never be fit to put on again. Here are your purse and your watch which were in your pockets. What do you think of those blue serge trousers and the pilot-coat with its gold buttons? Don't you like them?"

"Have you no black clothes?" asked the man, seizing hold of his purse.

"No; but why black? Your own clothes were grey."

"I should have preferred black, but no matter, it can't be helped!"

Meanwhile Gastan had opened his guest's watch like the badly-brought-up schoolboy that he was.

"I couldn't look inside your purse," he confessed.

"No," replied the man calmly; "it has a secret fastening."

"As for your ticker, look at those initials," exclaimed Vineuse with a burst of laughter. "The case bears a C and an A entwined. What are you called? Artful Charles, eh? Ha, ha, ha!"

"My name is Archibald Clarke, at your service, monsieur, and I am an American from Trenton, New Jersey. As for my story, I hope to have the privilege of telling it to you directly after lunch. Will you kindly lend me a razor?"

Gastan was furious. He swore at the intruder's manners (I mean at Clarke's), and he only changed his opinion at the sight of the American's (I mean at Clarke's) entry into the dining-room.

Mr. Archibald Clarke ate and drank conscientiously without uttering a syllable. He poured himself out a small glass of Scotch whisky with his coffee, lit a claro (a dollar, even at the manufactory) and, holding out his hand to us, said: "Gentlemen, I thank you."

Then, drawing two or three puffs in succession (value at least two cents a puff) he started speaking slowly, feeling for his words, and even perhaps for his ideas.

DOUBTLESS, (he began) you know the Corbetts—by name—of Philadelphia? No? After all it is not unnatural. In France one may well ignore the existence of a far-distant couple who, as a matter of fact, have made all the principal discoveries of these last years, but who have had the ill-luck to make them at the same time as other savants quicker to divulge their secrets to the world. Edison, the Curies, Berthelot, Marconi, Renard discovered nothing which my brother-in-law Randolph, and my sister Ethel Corbett had not made their own,—only the former made their discoveries a little earlier. So much so that my unlucky relatives were doomed to carry out their work of genius while an unexpected rival proclaimed his own discovery which was identical. 'Too late,' appears to be their device. That is why you have not heard of them.

Well, then, the other day, the eighteenth of August, as I was leaving my office, a telegram was handed to me, signed 'Ethel Corbett,' begging Mr. Archibald Clarke, chief accountant at Roebling Brothers, cable manufacturers of Trenton, New Jersey, to repair without delay to Philadelphia.

An hour later, the Pennsylvania Railroad having put me down at West Philadelphia Station, I was driving in a cab to Belmont.

The cab passed through the western suburbs, crossed a bridge, and reached the open country. During the journey night had fallen, but so star-filled was it that I could recognize afar off my brother-in-law's house.

I recognized it, messieurs, and my heart sank. In the whole imposing block of buildings only one window of the living room was illuminated.

Jim, the negro, opened the door to me in the dark, and led me to Corbetts' bedroom—the only one lit up.

I saw that my brother-in-law was in bed, and that he looked feverish and yellow. At that moment my sister came in. During the last four years I had only seen her face in the magazines. She had scarcely changed at all. Her dress had the same boyish cut, and her short hair was scarcely touched with grey, in spite of her years.

"How do you do, Archie?" said Randolph. "I had no doubt you would come as quickly as you could. We are in need of you—"

"So I should imagine, Randolph. What can I do?"

"Help—"

"Don't tire yourself," interrupted my sister. "I will tell him everything quickly, for time presses. Archie, we have built—No, there is no need for anxiety. Randolph is in no danger.

"We have built, in deepest mystery—Randolph, Jim, and myself—a highly interesting machine, Archie. And for fear that someone should once again forestall us, we have always vowed to give our machine a trial as soon as it should be finished. As ill-luck will have it, influenza has interfered with our plans. Today, at this identical moment, the thing is ready, and Randolph on the road to recovery. Nevertheless, it is impossible to postpone the experiment, and three people are necessary for the maneuver. Who is to take Randolph's place? I am. Who is to take mine? Jim. And who will take Jim's place? Why you, I thought."

"ALL right. Forget what is over and done with, Ethel. I have

come to make myself useful."

"We shall run some danger, so be warned—"

"That is all the same to me. I have come to make myself useful. Show me my bedroom. I will go to bed at once so as to be quite fit tomorrow morning."

"Tomorrow!" exclaimed Corbett. "It isn't tomorrow—it's now, at once! There, it is striking eleven o'clock! Go, my dear boy; go, and don't waste a minute!"

"What, the experiment—now, in the middle of the night?"

"Yes, it has to take place out-of-doors. And if it were daylight, would our secret remain a secret, I ask you?"

"Out-of-doors? Good! After all, what is it, really?"

But Ethel was full of impatience.

"Come along, then, as it is all settled!" she cried. "Everything is ready."

"Au revoir, Archie," said Randolph, "till tomorrow evening!"

"What? Till tomorrow evening," I exclaimed as I followed my sister. "You are taking me on a journey, it seems. Till tomorrow evening? But Randolph said we were not to be seen in broad daylight. So we are to stop somewhere before dawn? Where shall we spend the day? In fact where are we going to?"

"To Philadelphia."

"I beg your pardon! To Philadelphia? But we are there already!"

"Quite so, my worthy but stupid brother! We shall make a circuit, and return."

She led the way along an interminable passage, then through the workshop.

There one could see clearly. Through the glass roof the stars and the rays of the rising moon shone on a chaos of strange forms. To reach the further end of the room we had to walk in zigzag fashion, among the most fantastic disorder; step across barriers of iron ties which seemed to rise up against us; avoid weird creatures of steel, crouching on their four wheels; and also creep past unexplained mills with sails twisted screw-fashion.

Ethel threaded her way amidst this queer conglomeration without knocking up against anything. As for me, I but escaped the wiles of a rubber tire coiling round my feet, to succumb to the noose of a rope twisted in artful folds.

Catching hold of what seemed to be an iron shark, I managed to free myself, but only now to knock up against some sort of a wooden bird. But probably the presiding Sprite of Invention had put my valor sufficiently to the test, for all at once I found myself face to face with Jim, in the shed.

This shed was as big as the nave of a cathedral, and served as a hangar for the aircraft. They were standing all around it. The moon shone on their more or less shapeless bodies. With spherical wings, oval, spindle-shaped, all these planes standing against the wall seemed to be drawn back with deference to a kind of shining partition which stretched itself along the middle of the hall. Ethel pointed it out to me and said:

"There is our engine."

Then she started a low-voiced conversation with Jim.

"Oh, oh!" said I. "So that is the engine? Hum! An automobile—astonishing—or perhaps a boat?"

As far as I could judge in the half-light, where electric arcs uselessly dangled their foolish globes, the thing was a gigantic knife-blade, not with a cutting edge, but extremely pointed. I can find no better comparison.

At the stern I made out a triangular rudder.

"Oh, it's a boat!" I said to myself. "And yet, no; it's an automobile."

PUSHING away with her foot some stools which were lying on the

ground, Ethel opened a door in the side of this titanic

blade.

"There is your seat," said Ethel. "You will be at the helm, I in front of you. Jimmy in front of me. Oh, don't let us have any false modesty, please! We shan't ask you for your pilot's certificate, my dear boy. The use of the rudder is an exception. Perhaps you will not have occasion to touch it."

But—but where were the windows? No windows?

"How are we going to see our way?" I murmured. "How are we to know the road if it is an automobile, the shoals if it is a submarine, the mountains if, improbable as it seems, it proves to be an aircraft?"

At that moment my sister's voice rang out, intrepid and quivering with joy:

"Jim, open the doors of the shed! It is time to let our pet loose."

And the negro burst into a roar of laughter. I confess I have no great affection for blacks and their guttural talk. They always speak as if suffering from a sore throat. But Jim, with his husky laugh—no, you can't imagine how he disgusted me. However, the darky slid back enormous folding doors, and from top to bottom of the building a star-filled opening widened out.

"We must make haste," Ethel said. "I want to start punctually at midnight. Well, what is it, Archibald?"

"You—Are you not going to start the engine?"

"Oh, oh!" exclaimed Ethel, as if I had proposed something perfectly ridiculous. "That would be a nice job, wouldn't it, Jim?"

"Yes, ma'am," gurgled the negro with an irritating laugh.

As she leaned with all her weight against the back of the enormous machine it glided gently forward.

"Oh, she is well poised today," said Ethel simply.

And turning her back to the Schuylkill River, an action which effectually did away with any nautical hypothesis, she pushed the vessel towards the centre of the track in a westerly direction.

"You must forgive me, my dear boy, but I will explain the mechanism of the thing en route. For the moment I am too anxious."

WHAT a world of emotion sounded in her words! Through how many months of laborious anxiety had my companions awaited this thrilling moment?

At present, its size diminished by the grandeur of its background, the engine seemed less terrifying. Seen from the front, one saw nothing more than a huge sword-blade looked at from the point. Walking a little way off, to look at the whole effect, I discovered one or two slight excrescences on the top, invisible in the shed, and there were several more on the right and left sides. Ethel tested the blocks between the wheels.

We entered the great blade. Jim shut the hermetically closing door, and those soft, natural sounds that I had taken for absolute silence died in our ears.

At first I thought that the darkness filled the cabin, and again I began to fall into a non-comprehension of this expedition undertaken by blind prisoners, when my eyes were drawn to a pale spot of light above Ethel's seat.

It was a kind of large lamp-shade, luminous in the interior. I will try and describe it: a large hemispherical funnel hung mouth downward, its pipe disappearing straight up into the ceiling. This pipe could be lengthened at will like a telescope. Ethel pulled down the funnel, which fitted over her head, and gave to her face a livid pallor. Then she made me sit down in her seat. To my amazement, I seemed as if by magic to be transported outside.

I could have remained for a long while with my head under the marvelous lamp-shade if my sister had not regained her seat.

"Why, what do you find so fascinating in this playing with lenses?" she grumbled. "Every submarine in our Navy has one nearly as good."

From the funnel issued a blue, phosphorescent light. One after the other the instruments could be distinctly discerned in the gloom. Jim was bending over a compass.

He laughed no longer.

"Yes, ma'am," he said, "we'se exactly on the line from east to west."

"Good! Archie, to your helm; keep it perfectly straight until further orders, as if you were coxing a rowing-boat. Are you there, Archie?"

"Yes."

"Are you there, Jim?"

"Yes, ma'am."

"Good! Stand by; let her go."

"Hallo!" I exclaimed. "What's that?"

Ethel had taken no notice of my exclamation. She was watching a dial and calling loud the figures it registered:

"1000, 1200, 2000, 3000! Jim, check on the statoscope; 3500, 5000. That's right, isn't it?"

"Yes, ma'am."

"6000. 8000. 10000 feet. At last! Ah, 10800—that's too much!"

SHE seized a pendant chain and hung on to it. Now, this

resulted in a gurgling of gas escaping from a valve in what I

will call the attic up above us, and the needle of the barometer

worked itself back to the figure 10000.

"We have arrived," proclaimed Ethel. Then, looking at the clock above the negro's head: "Five minutes to. Good! We will start punctually at midnight."

"Upon my word!" I said at length, unable to contain myself any longer. "Upon my word! We shall start?" you say. "Have we not started already?"

"No."

"What do you want, then? What do you want to do, Ethel?"

"Go round the world, Mr. Inquisitive."

"Round the world—in one single day. Is she trimmed, Jim?"

The horror of an ascension with a mad-woman disguised as an aeronaut dimmed my gaze, and it was through a mist of fear that I saw the infernal Zulu busied with a spirit-balance. He had found the engine's nose was dipping imperceptibly.

Ethel declared that, after all, it was of no importance. The compass consulted confirmed her opinion, and she smiled and murmured:

"Excellent; heading full west."

"Start the engine, Jim. Make contact."

Jim pressed a big button. Immediately behind the partition at our backs, with a low and yet powerful purring, the invisible engine woke to life. It hummed louder and louder, and as it became stronger a wind seemed to blow round us, freshen, and grow into a storm-wind, then into a veritable tempest. A gale shrieked by the whole length of the craft; it became a simoon, and then a cataclysmal typhoon, and then something far worse, unknown to men until now. Streams of wind keen as endless javelins rushed through the chinks of the doors, notwithstanding their close fit. An army of vipers could not have hissed louder. They made a little tornado rage in the cabin itself.

At Ethel's command, Jim caulked the doors and stopped the draughts with tar driven in with a chisel. While this was doing, Ethel was examining a long, graduated scale, whereon a pointer moved forward continuously, and she enumerated more figures: "400, 500, 600, 700, 800."

I must explain that the figure 800 was proclaimed with an air of triumph, and at that very instant the pointer stopped on the scale and the column of mercury in the thermometer's tube, while the noise of the motor and the whistling of our passage remained constant.

Ethel showed me a graduated scale, whose indicator was permanently fixed at the figure 800.

"That," continued my sister, "is a speedometer—a kind of patent log. It indicates a rate of more than 13⅓ miles a minute, which is as nearly as possible 800 per hour."

"By Jove! We are moving at—"

"No, my dear boy, we are not moving!"

"Upon my word!"

"We are not moving. It is the air which slips by us. Our bark is motionless in a flying atmosphere. And that is why, Archie, I have christened her Aerofix."

"Oh!"

"Yes; wait a little. Now I am at your service. Only this tap to turn off. There, I am ready for you. And now we'll let some light into your mind and into this cabin."

AND my sister turned up the electric light, whose intensity

put out the moon and stars on the ground of the periscope.

"It is the air that moves?" I resumed in a fever of curiosity.

"Look here, my dear boy, Philistine as you are, have you never thought how ridiculous men are in the way they travel? Ridiculous to move themselves as they do, with great expenditure of steam, petrol, or electricity on a moving globe when it is enough to remain stationary above it."

"But," I hazarded, after scrawling some calculations on a scrap of paper, "I remember that the earth is 25,000 miles round. This being the case, as it takes twenty-four hours to pivot on its axis, it ought to pass by under the machine at the rate of 1,040 odd miles an hour—"

"Not so bad for a clerk in a cable factory! The man of figures begins to show in you. But, my dear stupid brother, it is at the equator that you find a girth of 25,000 miles, and at the equator alone; if we had ascended at Quito, for example, the speedometer would register 1040. But as Philadelphia, whence the Aerofix ascended, is on the 40th parallel, N., which measures but 18,000 miles, as it is nearer the pole, so the globe only revolves at about 750 miles per hour.

"Above all, observe, the higher the ship rises on the bosom of the mass of air drawn into the terrestrial race—elevation which enlarges a little the circle we seem to describe—the greater is the speed of the fluid which surrounds it, because the latter is getting farther away from the centre of rotation. This peculiarity would augment the effort which has to be made to remain stationary against a stronger current, if this vapor that one finds in ascending did not become more rarefied as the speed grows greater. The more furiously the wind buffets us, the less body it has, so the ram pierces it with the same ease, the two phenomena counterbalancing each other."

"But why remain stationary at 10,000 feet?"

"Because the highest peak on the 40th parallel does not quite reach this altitude. And we don't want a collision with the Rocky Mountains, do we?"

"So we follow this 40th parallel strictly?"

"Strictly. Maybe, one day our machine will be able to direct its fixity by our gravitational mechanism, or perhaps by the assistance of the earth's progression in its orbit. It would then be a question of attaining immobility by proper relation with the sun, so as to accomplish an oblique trajectory round the earth—at least, to appear to journey in this wise. But we are far from that at present. Today we must follow our chosen parallel like a rail. The rudder is merely an accessory designed to put the aviator in the right direction at the start, and to combat any dangerous winds during the descent. Nolens volens we are globetrotters, my dear boy. Look at the compass; its needle will not fall off one point in twenty-four hours except for the declination. The north is always on our right."

"So," I stammered, dazed and overcome—"so we shall be in Philadelphia again tomorrow, having covered all the 40th parallel. Is that the 'circuit' you spoke of?

"That is so. Now look at the clockwork globe. It is at once an indication of our successive positions, and an epitome of the whole thing. The point of the immovable needle represents the Aerofix. Every twenty-four hours the same places pass under it. Tomorrow Philadelphia will make its appearance. But we shall be a little late because of the time lost in taking up our station, and in re-catching the drag of the earth."

I felt beads of sweat pearling my brow, and the palms of my hands were wet.

"Confound the heat!" I grumbled. "And this infernal whistling! You are speaking at the top of your voice, and yet I can scarcely hear you."

"Yes. It is all caused by the friction of the air. Don't you find it stifling?"

She uncovered some small apertures pierced in the doors giving on the outer air by means of pipes bent aft in the direction of the wind. These ventilators were exceedingly well thought out, and a delicious freshness soon made itself felt. My sister continued:

"What trouble we had to find a remedy against the excessive heat! Ralph invented a heatproof coating with which the hull is painted—a non-conducting layer—"

I WAS about to give expression to some judicious reflections on the subject of air, and on the contradictory qualities it manifests—of chilling bodies moving at a great rate, and heating those moving at a prodigious rate—when my sister put out the light again.

Once the dizziness induced by the darkness was dissipated, I saw Ethel capped with the periscope, livid under its milk-white light.

"Their Serene Highnesses the Rocky Mountains!" she proclaimed. "Look at them, Archie!"

Under the full moon the swathed glaciers trailed their opalescent forms like comets' tails, and a flying whiteness lit up our transparent floor; their curves swelled beneath us; their great peaks sprang at us. It was a flock of mountains in a panic. They all sank away. The summits, dipping, re-entered the zone of the invisible. The sky, free of clouds once more, filled the periscope with its magnificence.

And on the instant the glass flooring seemed to sparkle with innumerable facets, and to become a be-diamonded pane, with the living fire of a gem in its dancing lights. The negro was seized with a foolish gaiety, his hoarseness increased with his joy, and became a raucous hilarity. He choked, heaving his shoulders, and gurgled some remarks in honor of the Pacific. Ethel confirmed him:

"Yes. Here's the ocean, right enough; twenty-two minutes past three. It is punctual to its tryst."

A cry escaped me: "If we fell—"

"Fear nothing, cowardly brother mine. The Aerofix is solidly built."

"H'm!" said I, put out by her assurance, and wishing to make a better effect. "Truly, it's a very fine 'heavier-than-air,' a very fine one—"

"It is a gravity-repelling ship Archie. No monoplane could sustain itself or retain its grip in this atmospheric avalanche—its hold would be too slippery. You see, we have conquered gravitation. But as you can well understand, in dealing with an Aerofix, that portion where the motor is found must be absolutely of a piece with the envelope, otherwise the former, following the rotation of the earth, would spread itself on the cording and break it, if it was not itself crumpled at the very outset. So our vessel is built of one single sheath, the metal of which is a strange alloy of aluminum, and of another substance which weighs the same as cork, but unfortunately somewhat lacks resistance. This hull is divided into two floors by a horizontal partition. The upper floor, up above has the gravity-repelling device whose nature is known only to us. The 'ground floor' is divided into three compartments—the cabin in the middle, where I now have the pleasure of instructing you; forward, an exceedingly narrow receptacle, where the Corbett accumulators are stored, a light but almost inexhaustible source of electric energy to operate the gravity-repellers; and lastly, aft, the engine-room.

"Ah, that motor! It is our pride and glory! You think, perhaps, of millions of horsepower. Not at all. The Aerofix has nothing in common with a steamer, which, struggling against a strong current, should have just sufficient force to prevent its drifting and keep it in position. We have really conquered the pull of mother earth; and just enough to maintain us at the height we wish.

"Our motor does not propel the Aerofix, but it delivers it from the drag of the earth. It is a generator of the power of inertia. Do you understand? And, if it produces the same effect as an airplane launched from east to west, it employs very little strength in) so doing."

"But what is it?" I asked. "On what principle—"

"Ah, just that I cannot tell you!"

"You know my discretion—"

"Look here, Archie, I will put you on the road to it. Don't ask me anything further. Do you remember those tops called gyroscopes with which we played as children? They spin in all positions on a taut string, without falling. On this support they form the most amazing angles, and seem to defy the laws of equilibrium and gravitation. The gyroscope takes the place of acquired speed. It is this power which a special arrangement of machinery has allowed us to increase. Behind you, six gyroscopes, six perfected tops, revolve in a void."

"Good heavens! Supposing they stopped without notice?"

"IT would have to be a very unlikely accident. Brennan has

shown that after one has cut off the motive power a gyroscope

will continue to revolve for twenty-four hours, eight of which

can be turned to account. An accident could only come about by

the destruction of—of—certain special machinery. And

unless it were done on purpose—"

"Ethel, Ethel! I am simply astounded."

"You can imagine, I suppose," went on my sister, "how I managed to move the vessel so easily? Weights hung underneath it, equalizing the lifting force, which was thus neutralized, so that our ship even before the degravitator was turned on only weighed the few pounds necessary to keep it down on the ground. These compensatory weights were detached automatically from the cabin. It was the simplest kind of 'Let go all!' Oh yes, the smallest detail is thought out."

"But," said I quickly, "is there no chance of this heat flashing the machinery."

"Don't be alarmed. Even the enormous and explosive bag of a balloon cannot explode except by contact with a flame or spark. It is a chimera!"

"Very good; say no more. I understand the system thoroughly, though at first I took your auto-immobile for an indubitable motor."

"What depth have we beneath our feet? What is the depth of the sea here?" I asked.

"Anything from 3500 to 7000 feet. We are somewhere between the 140th and the 160th meridians."

"Yes; true. It will soon be five o'clock."

"Five o'clock at Philadelphia, but not at any place we visit. Here it is always midnight. Midnight goes on with us. Today the Aerofix fulfils her midnight journey, motionless in the terrestrial space and as we count time."

Fear clutched at my throat.

"True, the sun never rises," I observed.

"Naturally. The sun is always on the other side of the earth.. After a fashion it plays hide-and-seek with the machine. Midday begins to rewarm the flying Antipodes. Since we are in the central point of that darkness which sweeps, or seems to do so, round the globe, Archibald, we shall lose a day of light, and shall have lived, on the other hand, a night too long. Later on, when our discovery will be made use of, when everyone will possess his own Aerofix, daytime journeys will no doubt be made, probably at least by foes to darkness who will be able to live facing eternal sunsets or bathed in the glories of unending dawn. Look at the sky on the ground of the periscope: the cupola of the one is reflected on the cap of the other, nothing moves but the moon. Even the constellations advance no longer. You might think the clock of the heavens have stopped."

"I know one that goes admirably, nevertheless," said I. "It is in my stomach, and repeatedly strikes the dinner hour."

We dined.

You will have noticed, gentlemen, by the manifestations of my hunger, that your humble servant's courage had risen a little. It rose a good deal more after our meal. Brisked up with excellent tinned provisions, and a glass of brandy, I found myself no more uncomfortable in this narrow sheath than in the corridor of a Pullman car. Only a general lassitude bore witness to the nervous strain I had just undergone.

But folded in the warm half-light, the peace following a good dinner weighed down my eyelids. They closed to the monotonous cradle-song of the whistling air and the humming gyroscopes. As if through a fog I heard the clock strike, and Ethel murmur that we had done nearly half of our journey. And then sleep entirely overcame me.

"Hi! Hi! None of that, my dear boy! You were asleep, I believe. Come! Come! I may need you any minute. You must keep a lookout, you must be vigilant."

"Humph!"

"Think of the charms of Japan, which we are now traveling over."

"To the devil with your Japan!" I retorted. "It is as black as if it had snowed soot."

JIM seemed intensely amused.

"And as to you, shut up," I said, drawing myself up. "You have no right to be so amused at the word 'soot,' old chimney-sweep!"

"Hush! Hush, Archie! Keep your seat."

The negro was bent double, his shoulders shook with a secret joy, and across his heavy face I caught sight of a thick-lipped smile. But Ethel's imperious tone had quieted me. I asked her dryly, still a little vexed: "Where are we?"

"Some miles west of Pekin. That is the Gobi desert."

"Still 10,000 feet above the earth?"

"No, of course not. Ten thousand feet above the level of the sea. The mean altitude of the desert brings us as near as 5,000 feet to the land."

For a long while I struggled against sleep. To overcome it I tried to interest myself in various things: my companions' attitudes; the changing faces in Ethel's curling hair; in all these supine countries where strange men slept on extraordinary beds under twisted roofs. But imagination in no wise takes the place of knowledge, and I knew nothing of all these out-of-the-way lands, and I could not even distinguish a tree! I was reduced to inventing the world after the fashion of children who stride across a wooden hobby-horse, and remain lost in deep thought imagining the road they have travelled.

None the less I suffered two alarms.

The first was caused by a shock, a very slight one, at the ram of the aerostat. Something soft had got in its way. My sister dissipated with a word the fear which had made me jump. She had seen in the periscope two large wings which were no sooner viewed than they were eclipsed.

The second alarm was due to the negro. Looking half wild he suddenly got up in his seat, asking: Were we always in the right direction? It would be too terrible if we had deviated, because of the Tianshan Mountains 10,000 feet in height. He himself was too unnerved to have taken note. A glass of brandy put fresh life into him. Becoming once more lucid and self-possessed, he took up his place again before the clock.

At length my sister announced gaily, like the steward of a dining-car:

"The first luncheon is served! It's well after midday."

"After midday," I repeated, assuring myself of the darkness. "Midday at midnight."

The Chinese firmament starred the shade of the periscope with its cosmographic dome, like those maps of the heavens curved in their imitation and called uranoramas. The night's blackness seemed tinged with green. Clouds, similar to our cumuli, hid and revealed the same stars, the solitary exception being the moon which, rising, had enlarged its melon-slice, and travelled to the southeast.

Lunch seemed like supper. And dinner resembled it. We did not do the latter much justice. The nocturnal afternoon had slipped by. The Caspian Sea, Turkey, Greece, Calabria, Spain, and Portugal had succeeded one another, invisible and lacking all interest for us. An unreasoning irritation made me beat my foot on the transparent floor, through which we could discern nothing. I became restless. I moved about in the confined space, and I was childishly overjoyed when towards a quarter to twelve I received the command to be at my post. My sister added that they were going to stop the engine and put a brake on the gyroscope so as to gradually regain little by little the drag of the earth, and ultimately be enabled to land at Philadelphia.

The electric light shone with a hard glitter. Jim pressed a big button and pulled over several levers which caught in a serrated rack. In the after-hold one could hear the steel shoes grinding against the spinning tops. The humming grew deeper, the air whistled less and less strongly, and the speedometer's indicator began to run backwards.

I clutched the handles of the steering-gear feverishly. My sister had ordered me not to make use of them without a given signal. At times, beneath my feet, some great Atlantic liner, glitteringly illuminated, striped the glistening stretch of sea with its white and red lights.

The situation lasted for what seemed to me an excessively long period. Leaning over my sister's shoulder to catch sight of her face, I found it expressing great annoyance.

"We are not slowing down enough," she said in answer to my question. "I am afraid of passing by Philadelphia."

"Do you not think we might land in one of the suburbs? Even if it were more than 100 miles out of the town."

The negro shook his head.

"No, Jim, we had better not, had we? It is no good to dwell upon it. I set to work too late—"

"Well, what's the trouble?" I exclaimed. "Once stopped, you back your engine."

"Archie, you are an ass! The ship, as you yourself very sensibly observed, is not an automobile but an auto-immobile. To go back on our flight the earth would have to begin revolving in the opposite direction, and the end of the world would follow your little fantasy, because of the shock. No, no; we are well supplied with everything we need; the only sensible thing to do is to make a second tour of the planed and to slow down earlier. Start the engine again, Jim, and take off the brakes."

WHILE she was forming this exasperating decision, which was immediately put into action, a misty patch, seemingly spangled with fireflies, unrolled itself at the bottom of the abyss— Philadelphia was passing.

"Poor Randolph," sighed Ethel, "how anxious he will be—" And without taking breath she launched out on a small, dry, wordy discourse after the manner of people who expect to be blamed by their opponent, and will not let him speak. Accordingly she took it on herself to inform me of the best method of making Belmont after the next day's descent. As she wished things, the apparatus must not come to ground at more than fifteen miles from the town; from there a truck could haul it to the hangar, which would be re-entered before daybreak.

In spite of her verbosity the word "daybreak" loosed the flow of my lamentations.

"Daybreak, alas! You may well say so, my good Ethel, I am just longing for it. It seems to me that the sun has gone out forever. Well, there, I came to make myself useful, I am resigned! But promise me that we shall be at Philadelphia tomorrow without fail."

"I swear it! Tomorrow at one o'clock or a little after. In one way or another by our maneuvers we have lost sixty minutes. Jim, put back the globe of the clock 800 miles."

But now Ethel busied herself with procuring necessary repose for herself and her assistants. She and Jim were to take watch and watch about. As for me, the strayed outsider of this expedition, I unexpectedly got leave to do what I liked. I think our captain rather feared the jumpiness that I had shown before in my abuse of Jim.

Worn out with fatigue I stretched myself on the glass floor, the pedestal of my seat between my legs. Under the cloak of rest I became a victim for long hours to the horridest nightmare. But no dream could equal in extravagance the fabulous reality. And my awakening seemed the beginning of a nightmare more horrible than all the others.

I knew fear, and made a despairing movement. Whereupon my hand struck something cold and smooth. It was the brandy bottle. In three seconds—time for a bump—I could conquer my panic. What was I thinking of? Since the memory of man fear had never seized on my valorous soul!

Nevertheless the sinister visitant returned to the charge, and to exorcise it I had recourse to frequent draughts of courage. And courage of this sort tastes good. Valiantly I swallowed it, without reflecting on the consequences of valor assimilated in this wise, incorporated in liquid form, in this confined cell where I shared my sad lot with an impudent negro and a well-bred lady.

And so my intemperance was big with consequences, and very considerable ones which I will confide to you alone.

It was seven o'clock when, passing over the Balearic Isles, Ethel gave orders preparatory to stopping.

"Now, then, Archie, wake up; you have slept enough. Take your tiller-ropes."

"Ay, ay, Madame Corbett," said I, with a gracious smile, "entirely at your service, Madame Corbett."

Quickly turning up the light, my sister looked me up and down. During the whole day that she had had me behind her she had never looked to see whether I slept or woke. My joyous countenance now merely showed a keen and highly legitimate satisfaction at landing at last at Belmont.

The brakes made a grating sound. The wind began to go down. My companions, busily occupied, did not cease from manipulating one after the other the infinity of regulating instruments. I was ashamed of doing nothing. But a just pride filled my heart at the thought of the services I would render with my rudder. They should see what a pilot I could be! Yes, there should be no two opinions about that! I was jolly well going to astonish Mrs. Ethel the masculine, and that rapscallion of a chimney-sweep! "One! two! port your helm. One! two! starboard your helm."

And just "to see" I pulled alternately on either hand. Needless to say, the rudder did not move. Held stiffly in the atmospheric stream, whose speed lent it the resistance of a solid, it was almost prevented from turning on its pivots. My efforts made me breathe hard; my tiller-ropes seemed screwed to something perfectly immovable. And it enraged me!

"You shall, you brute!" I said inwardly, to the recalcitrant rudder. "Move you shall, if I die for it!"

Thereupon, I pulled for all I was worth, and so violently, that one of the rods detached itself from the cursed thing. Unable to check my effort I pulled away a great length of it from the bulkhead.

"Hallo!" I said to myself, suddenly sobered. "I hope they won't notice anything!"

IT was extremely unlikely. The thoughts of the other two were

on their maneuvers. The accident might, perhaps, be made good. So

I fumbled about with my rod trying to refix it. But the rod,

which ran through the whole body of the motor, had got out of the

orifice whence it issued from the stern of the ship, and it was

the act of an idiot to try to put it back without entering the

engine-room; to try from a distance to readjust it to the

rudder.

Nevertheless, that is what I tried to do, with puckered brow.

All at once, anger overcame me. I banged the rod in with all my force, backwards and upwards. Something it met with gave way as easily as a bit of cardboard. It went through. I felt the end of the rod caught in the hole it had made, and I pulled it out with a brusque movement. Whereon a distinct whistling made itself heard, rising shriller than that of the surrounding air-current. Ethel was listening. Desperate, and perceiving that the rod was still stuck in something soft and hampering, I tried to tear away the clinging hindrance.

My sister and Jim turned round on hearing the suspicious whistling, and saw me on my feet tugging at the cordage with both hands. They sprang forward.

Too late!

The hidden entanglement had come away in the outer darkness, and far down beneath us there was a sort of frying sound which crackled, crackled—

"Good heavens, Jim!" cried my sister, "something is afire! I seem to hear sparks striking. Quick—quick—run—"

Jim fled towards the gyroscopes and I, losing my head, opened a door on to the void.

But I had no time to throw myself through it. A furnace-flash, a deafening thunder, a paroxysmal impression of light, and a most terrific uproar. I clung to the metal door and lost consciousness. The end of the story, gentlemen, you know more about than I do.

* * * * *

MR. ARCHIBALD CLARKE had ceased speaking. Open-mouthed, we watched him finish his last claro and his last glass of liquor. Thanks to him the box of cigars had diminished, and the circle of whisky in the bottle had sunk to a very thin disc like a fluid counter. We had frequently interrupted Mr. Clarke with admiring "oh's!" and "ah's!"

Gastan looked at him, wide-eyed, staring at this sole survivor of such an incredible freak. Mr. Clarke rose from his chair, and leaned against one of the portholes. Their little round openings lined the panels of the dining-saloon, like so many seascapes set in medallions; but they would have been considered wretched canvases, circles which cut out the mass of sea and the empty sky, to enclose them in flat geometrical shapes, which the horizon split into two sections, one green, and one blue. The American declared "that it was not at all pretty."

"Well, my man? Well?" murmured Gastan, who was meditating on Clarke's exploits.

"And so, monsieur," I said after a moment to Mr. Clarke "—and so your sister and the negro are dead?"

"Almost certainly," he replied.

And Mr. Clarke threw the stub of his cigar into the sea, as if Ethel Corbett's end and the destiny of Jim and the fate of a cigar-stump weighed all the same upon his phlegmatic soul.

"Niggers. Pooh! You know what they are. A dirty race! As to my sister—Well, the poor girl sometimes had these whims. That story of the legacy—you can't imagine—But what is the good of wasting words upon the subject? Bah!"

"Monsieur," said I at length, "can you explain this to me? When the Aerofix passed through the air above the Océanide, I noticed something strange about the whistling. The first day it began to make itself heard (I am careful not to say after the appearance of the vessel, for its light could not be perceived afar off) very much later than, when still invisible, the vessel issued from the horizon. And the Aerofix had, on the other hand, sunk far into the west, while we could still hear its whistling.

"The second time, there was approximate coincidence of duration between the sound of your vessel and the rainbow-like curve it would have made had it not been for the accident."

After a moment's reflection, Clarke explained: "It is very simple, Mr. Sinclair. The first day, having attained a point above the Océanide, we scarcely slowed down at all, and our speed was superior to that of the sound—which travels at 1090 feet per second. You grasp my meaning? The second day, our slowing down was more marked, and would have about equalized the two rates. Do you want further details?"

"Unnecessary!"

"After all, it is merely a problem for the Lower Form: given a train, etc.—"

"But, by Jove!" exclaimed Gastan, "with your powers of understanding, which seem very unusual, it is hardly possible that you cannot give us some tips about the Aerofix. The gravity-neutralizer, for instance?"

"I have told you all I know," replied Clarke, "and if I have confided in you—under the seal of secrecy—it is because you fished me out of the water, and your anxiety to know my story had to be satisfied. I can only tell you again that the working parts of the motor, its interesting parts, were hidden from me, and in no circumstances did I catch sight of them, nor was I enabled to form an idea of them."

Until we reached Havre, where Mr. Clarke took leave of us, it must be acknowledged that he kept an inveterate silence, not only regarding the "fixed flight," but on every other subject. We had great difficulty in dragging any details out of him about Trenton, the cable manufactory, and his beloved Roebling Brothers. And then, again, he would only speak to me. It was plain he did not like Gastan and, as long as circumstances forced him to frequent his host's society, he was civilly grateful towards him but remarkably laconic. As soon as the Océanide came alongside the landing-stage, Mr. Clarke, having refused the wherewithal Gastan had offered to lend him to return home, left us with a low bow, and crossed the gangway at a run.

The result of his departure was naturally to relegate Mr. Clarke to one's list of souvenirs and ideas. An absent person is no more than a thought; and as such his whole being—simplified, classified, reduced to essentials—appears to us with its peculiar characteristics as violently marked as in a character on a stage. Those who are dead and those who travel, one seems to look at from afar off; of their finer shades and of their appearances one can perceive but one dominant color, and that a mere silhouette, often enough caricatured. Mr. Clarke bore the aspect in our memories of some extraordinary puppet. The fellow's eccentricity jumped to the eve, as they say. Now that he was no longer with, us, a palpable witness of the marvelous adventure, his tale seemed like a dream to us, and he himself an hallucination.

I proposed somewhat late in the day to institute an inquiry on board. We set to work. It was carried out rather unmethodically, and merely ended in exasperating our curiosity. The sole information we gained concerned the tips he had distributed. Before leaving, Mr. Clarke had tipped the crew and the servants magnificently. That this cashier scattered the contents of his purse like a nabob already seemed to form an indefinite kind of charge against him. But that was not all—these gratuities had been paid by him, an American, coming straight from Pennsylvania, in French banknotes and louis!

SOME weeks after my return I was the owner of quite a little

"dossier" concerning Mr. Clarke, and the events preceding his

fall into the Atlantic.

First, there were newspaper cuttings and bulletins from various observatories noting such showers of shooting-stars as occurred on the 19th, 20th, and 21st of August, and the passing of a bolide across Europe during the night of the 19th to the 20th. Then there were, ready-translated for my use, divers attestations of Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese correspondents dwelling on the 40th parallel, who certified having spent the nights of the 20th and the 21st of August, up and about, without observing any abnormal light, or hearing any unusual whistling.

That they had seen nothing was not unnatural; Mrs. Corbett cut off the electric light when they were above continents. But that they heard nothing—what do you make of that? Now, regarding the question of these depositions, it was necessary to have guarantees of the perfect good faith of their signatories.

There were also translations of letters, but letters sent from Philadelphia and from Trenton. They form a formidable pile of evidence against Mr. Clarke.

Certainly there was a Fairmount Park at Philadelphia; and in Fairmount Park, west of Schuylkill River, a place, Belmont, with an open plain surrounded by hills "exceedingly suitable for launching an airplane," as our civil informant observed. But the Corbetts did not exist.

At Trenton, among the manufacturers of pottery and the less honest fabricators of Egyptian scarabs, the cable manufactory of Roebling Brothers was known. But no cashier in the establishment answered to the high-sounding name of Archibald, or to the crisp and clear-cut one of Clarke.

Our man had again become "the sinister being," "the unknown," "the castaway."

"Le Voyage immobile", Mercure de France, 1909

"Le Voyage immobile", 1919 and 1822 editions

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.