RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage German print

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage German print

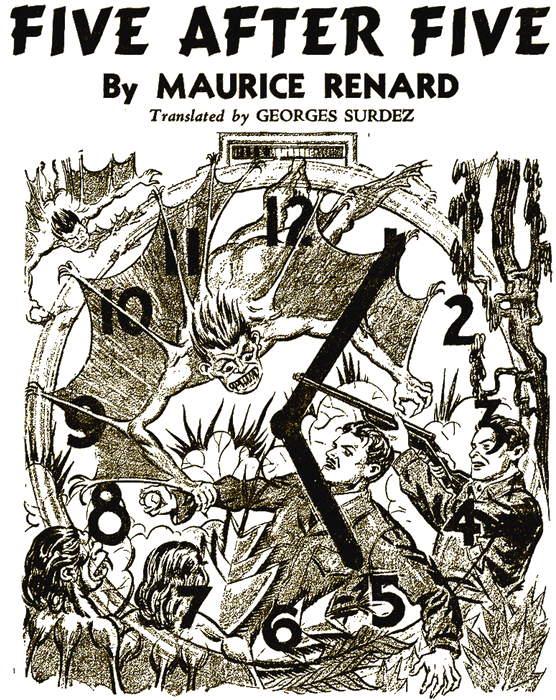

Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1941, with"Five After Five"

The detonation roared out like a clap of thunder.

Time and Tide Wait for No Man—

Unless He Can Find a Way of Killing Time!

I HAD joined my friend Mauclair for a few days' rest at his country place in the Champagne District of France. Mauclair is perhaps the most famous geologist his country has yet produced. He thought we both needed a short vacation from our work for the Museum. I was easily persuaded. He left Paris for the country late in October, and I followed two days later.

"Get your coat on," Mauclair suggested, after I had cleaned up from the dusty train journey. "It's getting cool now and I want to show you my hobby—my mushroom cellars."

"How far?" I asked.

He pointed through the window toward the crest of a hill.

"Up there. See that slope? It's honeycombed with underground passages. They're abandoned quarries, Paul. I use two of them for raising mushrooms. There couldn't be a better place. If it sounds dull to you, bring along your shotgun."

I took my shotgun and a bag for game, and we started. The path rose easily through denuded vineyards. We climbed slowly toward a patch of woods mottled with the rusty, bronze hues of autumn. Not a breath of air stirred the branches. Constantly we heard the whisper of dead leaves dropping from the trees.

We paused before entering a sort of sandy trench arched over by acacias. It was then that I first noticed the fog. The mist seemed to be engulfing the lowlands like a gray veil that thickened second by second. A flat cloud hugged the village of Cormonville below. Invisible trailers spun across the gorge, impalpable streaks, stagnant and increasingly opaque. Over the plain, long vapory bars formed and multiplied.

"Better hurry," Mauclair said. "It'd be easy to catch cold here."

I followed him down the sunken path. After a few steps, the surroundings grew hazy. I passed a hand over my eyes but that haze persisted.

"Aren't you afraid of getting lost in this fog?" I asked.

We were passing between walls of tawny sand streaked with chalky earth. He picked up a handful of earth, crumbled it in his fist, and offered it to me. I saw nothing save fragments of shells, some of which, due to their small size, had remained intact.

"Remember what I was telling you?" he said.

I recalled perfectly. The plain, stretching beyond our vision, seemed to be moving like the ocean. The small villages scattered here and there reminded me of rocky islands. The clumps of pines somehow suggested coral reefs. Even the road in the distance, so straight and white, might have been mistaken for a breakwater.

"This country resembles the sea as a son resembles his father," Mauclair had said. "Those hills, far over there, first emerged from the sea during the Eocene period, when the waters subsided through the centuries."

"Yes, I remember what you said," I replied. "But what about this fog?"

"No chance of losing my way. I know this part of the country blindfolded. Anyway, fogs are never too thick around here. If you don't mind walking faster, we'll soon be through this one."

The path rose sharply, and soon the air cleared. To my surprise, however, I noted that the village of Cormonville was no longer visible. The valley was filled with nebulous billows, stretching to the horizon, obliterating everything.

From where we stood, the country was like a vast, smooth steppe covered with snow. I had the impression that a deluge had marooned us, the sole survivors of Earth, on this hilltop.

This feeling was fleeting, for we heard the voices of wood-cutters and the chirps of birds rising from the blanket of mist. Muddy swamps held the moisture, last vestige of the Paludal Era, followed by the Lacustral, which in turn was succeeded by the Marine Epoch.

INDICATING the hollow which opened before us, Mauclair said:

"My mushroom cellars are over there."

We followed a path which circled downward around the crest. A line of firs grew from a steep slope on our left. To the right, tufted with briars, the slope swooped downward and vanished in the fog.

The Sun, which had shone so brightly for a moment, was now a pale disc blurred by vapors. I barely had time to see the openings of five or six quarries which pierced the slope at intervals when the Sun disappeared.

A wan obscurity surrounded us. We could see the dim outline of walnut trees emerging and vanishing again in the gloom. Against my objections, Mauclair continued toward the cellars. He advanced without hesitation, although we could no longer see the path. A moist odor penetrated my lungs. My eyebrows were wet. Drops clung to my garments.

Yet the haze thickened steadily. It was like a disease of space, it filled the void so completely. It muffled the sound of our steps. It was so heavy that it suffocated us, and so dense that a fish might almost have lived in it—as when the sea had covered this country.

MAUCLAIR stopped finally. I could no longer see my feet. In

the fog pressing about us, another fog was rising. It was icy,

biting into the flesh of our legs.

"We'd better wait until this is over," Mauclair said. "Otherwise we'd get lost. It can't last long. Interesting spectacle, isn't it?"

"What will happen to us?" I asked. He laughed. "Nothing to worry about."

Now we could only see ourselves from the waist up, then the neck, then—nothing! I had the horrible sensation of having been plunged in an icy fluid. Although I held my hand before my face, I could not see it. I could feel every nerve in my body bristling.

"What surprises me is that a hygrometrical fog does not turn into rain at this altitude," the geologist said. "Rain? Ice! But this terrible cold is not even freezing the moisture on our clothing."

I licked my lips.

"Salt!" I gasped.

"Right. It's like sea water. So that's why this fog didn't turn to rain."

"Did you ever see anything like this before?" I asked.

"Never. We'll make a report on it. Definition: 'Absolute obscurity, yet a dull white.' Ah, it seems to be clearing up."

Our surroundings became more luminous. I discerned Mauclair's shadowy silhouette, which materialized gradually as a whole, instead of piece by piece as it had disappeared.

"What the devil does this mean?" Mauclair cried. "We stopped on the path."

"Well?" I asked.

"Well, what's this reddish sand we're standing on?"

"Perhaps we strayed off—"

"Off where? Red sand here? Never knew of any."

"Perhaps it's the effect of this salt fog," I offered. "A combination of its chemicals with those of the earth. But the appearance of this soil is still uncertain. It seems to float."

He stooped, examined the red sand.

"There's a breeze starting," I announced. "Can't you hear it through the trees?"

"The fog isn't moving," he retorted. "Consequently there can't be any wind."

"But that sound of wind in the trees, to the right—"

"There are no trees to the right."

"No trees? But we can hear the sound of the wind."

"That's not the wind," he insisted.

"What is it, then?"

"We'll soon know. The fog is lifting."

The light was increasing swiftly, the cold dwindling. Vague objects became perceptible, boulders, tufts of grass. After examining the grass, the geologist uttered an exclamation.

"Look at this!"

He was interrupted by a trumpeting cry, raucous and ferocious. We stared at each other with startled eyes.

"Look at this grass," Mauclair whispered again.

"Tropical grass," I muttered. "Growing in France—"

"Listen now. That's what you mistook for the wind. It's some vast body of water."

THE wavering light was increasing constantly. We saw something

that proved to be a column, rather dilapidated at the top. Behind

it reared similar columns.

"Paul, look over there—that tree!" The crest of the column emerged from the obscurity of the fog. A palm tree was taking shape before our eyes! Farther away, another column became a tree in the same misty fashion, then the other columns grew visible.

Suddenly we discerned the edge of a body of water. Waves of aromatic balsam odors came to our nostrils. The waters rustled loudly, then whispered. The light drifted through the fog like a photographic print clearing in a hyposulphite bath. Second by second, the phantasmagoric scene became steadier, sharper, deeper. The circle of our vision seemed to be about twenty paces in diameter.

"This is something like the mirages of the desert," Mauclair said. "But it is a strange one. Instead of giving the impression of being seen at a distance, it actually seems to surround us."

"Yes," I agreed. "But stranger still, it appears to cover a large area, and to affect our hearing and smell as well as our vision."

"A mirage which makes us see, hear and smell something which is at a great distance from us. Sight, hearing and smell are all related, connected in space from the spot where we stand and the locality we see projected on the fog around us as on a screen. I know such red sand. Let's see—in Egypt, eh?"

"Farther south," I answered. "I think these are equatorial plants. See, there are nopals, a baobab—"

"What!"

"And those palms over there," I whispered. "Their tops spread out like peacocks' tails. Don't you recognize them?"

"The dichotomous species of South Africa, of Madagascar!"

"Yes," I said. "The Flabellaria Lamanonis, found at the Cape in Madagascar—or here in the Tertiary Age!"

"The Tertiary Epoch? What do you mean?"

"Look at those arborescent ferns, near the aloes."

"They're osmonds, the Ceylon species," he replied.

"You're wrong. An extinct species."

"Are you sure? You're right! Look, a parasol palm. Rose laurels, camphor trees, myrtle, birch—"

"Vine stocks, English oaks, walnut trees."

"Angiosperms. We've landed in the middle of the Neozoic period!"

The sound of the waters swelled to such a volume that we both swung about sharply. We saw only the fog and the gentle slope of red sand sinking into it. A foamy crest spurted and spread a lacy pattern at our feet. A second billow followed with the roar of a cataract.

"The sea!" I shouted. "The sea which existed here millions of years ago!"

"No longer a mirage of space," Mauclair said gravely, "but a mirage in time. We have the illusion of having moved in time without moving in space. Look!"

The fog was receding at last. It hung overhead like a nebulous ceiling. But in the other dimensions, the countryside was plainly discernible. We saw enough to identify the approximate contours of the region near Cormonville, by its overhanging bluff and by the ravine skirting the antediluvian beach.

THERE could be no doubt of it.

Some phenomenon of time and space showed us the Marne region of France in its prehistoric form. These oaks and maples were the first trees of that species to grow in Europe. That vine was the first vine of Champagne. A horrible cry tore through the haze above us. We saw the fading shadow of something monstrous, winged.

We were both trembling. The first trumpeting call was repeated in different directions in the vastness around us.

"Proboscidian, isn't it?" Mauclair asked.

"Right," I said. "Elephas meridionalis or primigenus."

"Damnation! I wonder if this mirage can be felt too?" He crouched and fingered the grass. "It can."

I removed the birdshot from my gun, slipped in two ball cartridges instead.

"We must be dreaming!" Mauclair said, when he saw me doing this.

"We're not dreaming," I replied. "Men like you and me are not affected by the same hallucinations at the same time. We can see, hear, smell, even taste and touch a scene from the past."

Furnace heat abruptly weighed us down. Our damp clothing steamed. I removed my hunting jacket. The Sun, enormous and red, rose in a halo of haze. I glanced at my watch.

"Isn't the Sun strangely placed?" I exclaimed.

Mauclair couldn't help smiling.

"You have forgotten that the Earth has not ceased rising along the ecliptic." He drew out his watch. "Actually it is now four-twenty in the afternoon. We must recall that. But artificially—that is, according to the Sun in the mirage—it is about ten in the morning, and springtime."

We talked without taking our gaze from the immense stage on which the infancy of the planet was being magically reproduced. The zone free of fog was widening around us. I saw a fin break the surface of the sea, a serrated fin that rose, arched and disappeared.

The salty tang of the sea, combined with the smell of the pine trees, made our blood race. The palm grove followed the line of the red strand. Through a gap in the trees we could see a bluff, a wall of marly clay, and the gaping opening of a cavern.

The vegetation interested me more than anything else. There were plants of extravagant dimensions. Some bore voluminous corollas, of deep violet color, with golden yellow pistils. At the base of the tree trunks was a tangled mass, in which the aloes darted their spiny tentacles like those of a greedy octopus.

Where the swollen ovals of the cactus brandished hoops bristling with spikes, it was a scramble of green, torturous tendrils at the bottom of the enormous ferns. The struggle for life was evident beneath the shrubbery.

In the gloom of the undergrowth appeared bluish pyramids, half fern and half larch, both tree and shrub. Each of them supported huge, monstrous, gargantuan pears.

Perspiration stuck on our cheeks. The sky was overcast. But now the last shred of mist vanished like frost in the Sun. The sea, rippling with waves, stretched out before us. The hill behind rose darkly from the gloom as we had seen it rise from the fog. It tipped an inlet flanked by two peninsulas. We stood on one of these spurs of land. The other was opposite us.

It was a length of reddish soil, sprinkled with a few sequoias which grew nearer together as they receded toward the mainland. The back of this little bay was furry with the greenish woods which reached us, thinning out as they grew toward the tip of our peninsula.

From that forest came six mighty elephants!

WITHOUT being conscious of moving, we found ourselves

crouching in the shelter of the rocks.

The titanic animals passed one by one, silhouetted sharply against the sky. It was hard to distinguish their tusks. Mauclair claimed that each one had four. I maintained that there were but two. We could not decide between the elephas meridionalia, antiquus or primagenus. We could not ascertain to what period of the Cenozoic Age the mirage had transported us. It was not the Eocene nor the Pliocene. The sea and the vegetation proved that. But was it the Oligocene or the Miocene? Something else settled the question.

The leading mammoth paused, spread his huge ears, gave an ear-piercing blast and lumbered swiftly behind the hill. When his comrades followed, the Earth seemed to quiver. To the north appeared a dark mound moving through the trees, its top looming over the crests of the tallest firs.

"A dinotherium!" I whispered. "Yes," Mauclair said. "A mastodonic tapir of the Miocene Age."

A sort of land whale, it seemed lost, constructed for the colossal reaches of the ocean. We knew that it was not at home on land and would soon be gone.

We were lucky enough to have the opportunity to examine him at leisure. He raised his stumpy trunk in the direction the mammoths had gone. Then the huge beast trotted to the tip of the promontory which concealed the northern horizon. There he started to root in the ground.

Above the sea, we saw a flight of huge flying animals, which were skimming the waves as they approached the coast. Suddenly they hurled themselves at the dinotherium.

The massive animal rose, hemmed in. The screaming horde swung above him, harassing him. Then, one after the other, the attackers landed on his mountainous back. The beast turned tail, howling. His yells resounded like the bellowing siren of an ocean liner.

His tormentors, soaring again, escorted him on his flight, screeching fiendishly. For a long time we followed the scene with our eyes.

"I'd give five years of my life for binoculars right now," Mauclair said, squinting in the Sun. "As it is, I only have my watch. What were these flying things?"

"Pterodactyls?" I suggested.

"No. The flying lizards no longer existed at this epoch. What horrible howls! I can't think of anything like the sounds they made, except for—"

"For what?"

"A monkey might scream like that."

"You're right," I agreed. "But let's talk in a lower voice. We don't know what might be lurking near us."

The foliage of the palm grove quivered. Swarms of gnats danced in the midst of the transluscent obscurity. The jungle was awakening each moment. I could not rid myself of the feeling that some monster had seen us and was watching us.

"Let's get on the other side of this rock, so that it will be between us and the land," I suggested.

"Good idea," Mauclair said. "But I expect to see this mirage dissolve any moment."

"Until it does," I remarked, "we'll be in a rather precarious position."

T HE sea was breaking at the base of the rocks when we reached them.

"Let's stay here," Mauclair said. "The main idea is not to attract attention by moving too much. Also, it might prove dangerous to wander around in a mirage. Don't forget that the country we're seeing is only superimposed on the locality where we really are. In this antediluvian void, one might run into a tree that's quite real. That, I think, is our sole peril.

"That must be it!" he cried, punching one fist into his palm. "No matter how complete the mirage is, it is nothing but an image. How stupid of me! The images of the elephants couldn't have done us the least harm. They are imprisoned in their epoch exactly as we are in our own era."

"I'm glad to know that," I said, for his confidence was contagious. "Those monsters can't see us, since mirages are not reciprocal. African mirages never are."

"Naturally." The geologist nodded. "We can have a memory of the past, but not of the future. If we had shouted as loud as we could, the dinotherium and the mammoths would have heard and seen nothing."

So we left the shelter of the rocks. The tracks of our boots dented the hard sand. Mauclair stood with his arms folded across his chest, staring at the waves.

"There it is, the sea of Earth's early days. Everything that breathes comes from the sea. At the time we're seeing now, she has loosed her grip on the continents. The Reptilian Age is already long past. The mammal and the bird have replaced the reptile, and soon man shall arrive."

"You know," I said, "as long as we're traveling in the past, I would have preferred the era preceding this one. It would be something to see the dinosaurians."

"Bah!" he snorted. "All your diplodocus, megatherium and other iguanodons were really a marine population. They spent most of their existence in the sea, not as the books and museums represent them, on land. Don't feel sorry about it. Wasn't the dinotherium we saw a survivor of the giant mammals?"

"Yes, but not a Saurian," I said regretfully. "If I could have chosen, I would rather not have gone so far back. I'd like to have seen the age when man was just emerging from the stage of the brute.

"Wait a minute," I objected. "Man's ancestor has always existed. In the Pliocene Age, I'll grant you that no men existed such as in the Stone Age. But there must have been some species extant."

He nodded. "Apelike, somewhat more sullen, a bit more talkative, and not as quadrimanual. They lived in troops, instinct telling them that union meant strength. But they lived far from here."

"In Oceania, wasn't it?"

"Yes, in Oceania, the cradle of mankind. Nowhere else have anthropomorphic fossils of the Pliocene strata been discovered. Remember the pithecanthropus discovered by Eugene Dubois in Java? It came from a strata that immediately followed the era we are seeing now—"

"Was it really a man-outang?" I interrupted. "We can construct anything we want from a few teeth, a piece of skull and a femur."

"I'm surprised to hear you talk like that, Paul."

"But such a femur!" I cried. "What a weird thigh it must have come from, covered with bony knobs that have never been explained, except by the ingenious excuse of rheumatic ailments. Imagine the ape-man with rheumatism! Perhaps in the glacial periods, but never in the Pliocene Age. It's crazy."

"It's nothing to laugh at," Mauclair said. "The Java bones Dubois found are bones from Pithecanthropus. The knots on that femur might indicate badly knit fractures. How can we know?"

"The birds are coming back," I announced. "They're fishing over there. It looks as if their plumage is white. Maybe it's just an effect of the sunlight falling on them, though."

"I'd like to know what they are," Mauclair grumbled. "But I guess there's no hope. Let's not waste time. We'll try to identify what's near us. The woods, for instance."

HE walked forward cautiously, arms extended before him He was

convinced he might run into a tree from the original landscape,

unseen in the mirage.

"Look!" I whispered. "Look at the cavern!"

Phosphorescent spots had appeared in the gloom of the cavern in the hill.

"I'm going over there," Mauclair stated.

"Don't be an idiot. It might be extremely dangerous."

"Supposing this mirage fades," he argued, "won't you be eternally sorry that you spoiled our chance to see something?"

"And can't you see that those are red-rimmed, ugly eyes watching us?"

"Are you mad? How can they see in the future?"

But I held him, for I was guided by an inner instinct stronger than reason. He finally gave in and contented himself with a long distance examination.

"Notice anything strange about that ray of sunshine?" I asked.

"Which ray?"

"The one shining into the cavern. The two eyes nearest the entrance—aren't they above the ray? If they were the eyes of an animal standing on the ground, we could see the animal in the ray of light."

"Good deduction!" he exclaimed. "Then those eyes must belong to an animal clinging to the roof of the cavern."

In the depths of the cave, the number of glowing eyes increased rapidly. Foolish as it seemed, I could not help keeping a close watch on the surrounding country. The palm grove, bisected by the streak of reddish sand, cast its deep shadow to the right and left of the cavern.

Now I saw that this gloom was also pierced by glowing eyes. There was a pair at the base of each of the huge pears we had noticed before, and this Argus-eyed forest scanned us with all its hypnotic pupils.

"Your 'pears' are merely bats," Mauclair said. "Hanging head downward, they swing from the tree branches and the roof of the cavern in their conventional position. But they must be diurnal creatures. I think those sea birds we saw were also bats."

The sight of an ordinary bat nauseates me. As I stared at the cave and the palm grove, with its population of bats suspended heads downward, I felt my stomach turn. Impulsively I stooped and picked up some small rocks. My first stone missed the opening, smashed on the wall and fell into a pile of rubble. The second hurtled into the depths of the cavern. Instantly there rose a frightful clamor which seemed to come from the bowels of the cave. We saw something stir in the obscure depths, take shape as it advanced beneath the flaming eyes.

"A man!" I breathed.

"An ape!" Mauclair whispered. It was a biped walking erect, possessing a small, ball-shaped skull, prominent jaws, large, protruding ears, and a body covered with hair. Without a doubt, this was Pithecanthropus, man's first ancestor! Because of some strange alliance, he was living with huge vampire bats, sharing their home. He had no right to be alive in that era!

THE man-ape halted on the threshold of the cavern, opening his

closely set eyes which he had kept half-shut. In the full light

of the Sun, we saw something unbelievable about him. We expected

to see him stark naked—but he was draped in a long

maroon-colored leather cloak, which hung to his heels and

completely covered his body.

"A coat!" Mauclair gasped. "The beast was really civilized!"

Pithecanthropus frowned as an ape might, then turned his head in manlike fashion. The tumult in the cave died out.

"He is looking at us, I tell you," I whispered anxiously.

"It seems he is," Mauclair admitted. "But though he is looking at us, he can't hear us. Obviously that's impossible." He smiled reassuringly and cried out to the human beast: "Hey, there, grandpa! What's your name?" Then he burst into a laugh of derision at my fears.

But now the creature stretched out an arm, from which hung a fold of his maroon cloak. His mouth opened, revealing a maw bristling with fangs. He yelped out a complicated barking. "Hattuix, tuix, tuix! Hirah-ah! Rak! Rak!"

As the jabbering issued from his leathery lips, a band of similar beings emerged from the cavern. Then a line of them stepped into view from the palm grove and the clumps of pines to the left. An ammoniacal stench, like that of a monkey cage in the summer, assailed our nostrils. Horrible howls filled the air. A bestial, hostile swarm surrounded us. All of them wore maroon-brown leather cloaks like their chief's. They shook them angrily.

I wanted to race back to the shelter of the rocks on the shore. But flying swiftly over the waves came a flock of the huge birds we had seen before.

"Flying men!" Mauclair shrieked.

It was true. They were flying men. The maroon cloaks of the primates which surrounded us were in reality great folded wings! The 'pears,' the birds, the bats, the pithecanthropes—they were one and the same—flying men.

We were hemmed in on all sides. They fluttered above us, obscuring the daylight. We could not flee in any direction. Instinctively we had huddled back to back. I handled my gun nervously.

"You see," I stammered. "The mirage is reciprocal. We see them and they see us."

I felt Mauclair shrug his shoulders.

"Natural phantoms," he said doggedly. "Try to remember all you can of this, Paul. So man finally lost his wings through disuse! Evolution punished him for his laziness, the same as it punished the penguins for theirs."

The pithecanthropes—or, since they were winged, the pteropithecanthropes—were for the moment content with observing us. Mauclair, eternally the scientist, was thinking aloud. The better to remember what he saw, he was making verbal notes. I could hear him registering the following points:

"Face, negroid and prognathous. No sign of civilization. No fire. Rudimentary language. Chief the strongest, not the oldest. As among animals, equality of the sexes. No weapons. The wings —unequaled, joining arms and legs. That explains the protuberances of the Java fossils! These are intermediate beings between the bat and the flying squirrel, but they are neither insect-eaters nor rodents. They are fish-eaters descended from the pterodactyls. All of the Terrestrial fauna is descended from saurians. Agree to that, Paul?"

"We've got to do something," I said nervously, looking at the horde around us. "Any minute now—"

"There's no danger," I heard him grumble. Once more he complained about the lack of equipment for recording.

"Use your watch," I suggested with some irony. "You can at least know the time—our time."

"Five after five."

"Quick, hide it!" I cried. "It excites them. Put that watch away. They're going to attack!"

ARK, heavy objects dropped on us. I stepped aside. A paw, tipped by claws and covered with hair, grasped the hand holding the watch.

Mauclair fell. One of the creatures struggled with him. The back of the brute's head was exposed to me. I shouldered my shotgun and fired.

The detonation roared out like a clap of thunder. Heavy smoke surrounded me, blotting out the Sun of this far-distant age. The smoke lingered, thickened.

Then I understood that it could not clear, for it was the fog which had returned. The flash of my shotgun had shaken it, dissipating the pictures which had played upon it.

We were back in the twentieth century!

The darkness of evening had come and a light rain fell through the mist. In the gloom, I could see Mauclair stretched at my feet, face downward. He regained consciousness with a moan.

"They've almost killed me," he groaned.

His hands were clammy as those of a corpse. Frightened, I chafed them roughly. As he stared about, his face was twisting. At last he rose with a great effort.

"Let's go home," he muttered.

Looking around for some branches I found two and quickly made a cross on the ground. Twenty feet farther on, we found the pathway, where I made another cross. A few minutes later we met wood-cutters, returning to their village. They had seen nothing save the fog, heard nothing but the gunshot.

"The phenomenon was located to a restricted area," I said, when they left us.

Mauclair descended the slope as quickly as he could. An owl, flitting by silently, made him draw his head down between his shoulders and raise his hands in alarm.

At last we were in the safety of his small chateau.

We agreed that we would keep our adventure secret for the time being. This was not hard to do, for later that night, Mauclair became ill. He was weak and his hands had remained as cold as those of a corpse. I got him to bed.

Luckily the fever abated by morning. The doctor prescribed rest, quiet, sleep. But Mauclair wanted to speak to me first.

He wanted me to return to the scene of the mirage and locate the site of the cavern. It must be located at all costs, for he was sure it would contain invaluable fossils. He congratulated me on my forethought for placing the crosses on the ground to mark the spot.

I brought along laborers equipped with picks and shovels. The two crosses had not been moved. The location of the first showed the way to the second, and the second showed the position of the cavern.

But the work of centuries had pushed the ridge about twenty feet forward. That would have required digging a gallery of this length. But two feet to the left there was the opening of a quarry tunnel. I measured the twenty paces along its wall. The workmen attacked the right side, removed rock and soon struck the soft clay.

At about three in the afternoon, I told them to stop.

No cavern had been found. I believed it must have caved in during the geological upheavals of the centuries. But upon sifting the soft clay, we found bones.

IT was a skeleton—the fragments of one, identical with

the one Dubois discovered in Java. The arms and leg bones all had

the well known knobs, which are neither badly knit fractures nor

the effects of disease.

They are truly apophysis to which the tendons of the membranous wings were attached. These fragments, when assembled, formed an almost perfect skeleton. It may be seen in the Museum under the supposedly fantastic name of Pteropithecanthropus Erectus. It has also been called the Anthropopterix, and is best known as "the Winged Man of Cormonville."

The time mirage had given us this great discovery. That it was a reciprocal mirage, Mauclair and I were convinced. We were convinced of it until later, when a workman brought me something else he had found in the pit we had excavated there.

It was a right hand, glued to the boggy clay in which it had rested. The crumbly white bones of fingers clutched a round, fossilized object. I pried it from the fingers and stared at it in bewilderment. At length with a knife I pried it apart.

Covered with a mineral crust, the bent and disclosed hands of a watch pointed to the time:

"Five after five."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.