RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Albert Henry Collings (1868-1947)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Albert Henry Collings (1868-1947)

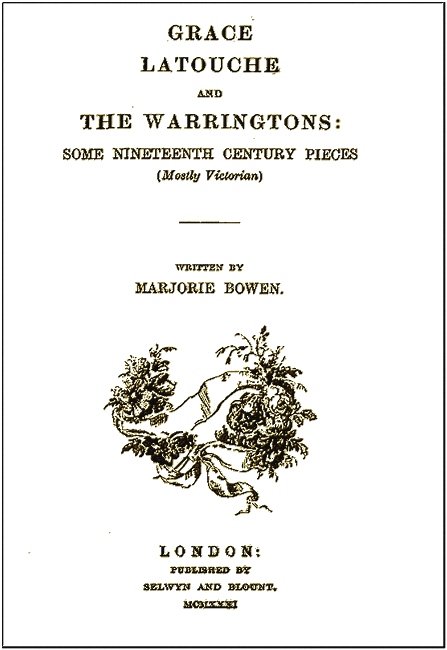

"Grace Latouche and the Warringtons,"

Selwyn & Blount, London, 1931

"Grace Latouche and the Warringtons,"

Selwyn & Blount, London, 1931

"Grace Latouche and the Warringtons,"

Selwyn & Blount, London, 1931

A SUBTLE essence of Victorianism pervades these "nineteenth century pieces," and there are many signs that Miss Bowen has enjoyed the writing of them. She is at her very best when recreating a past, not too far distant to alienate those who are shy of historical fiction, and far enough to provide excuse for numerous little embellishments of courtliness, coyness, dignity and romantic affection. There are stories of ghosts, elopements, love, murder and mystery. Perhaps the best of all is "The Crown Derby Plate," but the title story which tells of a dignified woman of "easy virtue" who is forced to spend an evening in the company of an ultra-respectable wife and mother is a very close second. All the stories, whether dramatic, amusing or macabre have point: their great virtue is that they are stories, and do not depend upon the finishing touches, graceful though these are.

The Spectator, London, 5 September 1931

Alcander, being now entirely at liberty (and coming into £700 a year), determined to travel into foreign countries, and in a letter to Amasia, informed her of his design; the reading of this had such an effect on her that she was found hanging in her chamber.

"Female Credulity," Lady's Magazine, 19th century.

MRS. LATOUCHE dropped the green damask curtain between herself and the sleeping youth. The nurse and doctor had departed with a discreet hush of step, look and gesture, which distinctly conveyed—"He had better be alone with you when he wakes, if he wakes at all..."

Grace Latouche folded her small hands in her lap and leant back in the low chair; her movements were naturally graceful. It was a summer afternoon, and this woman had always found a peculiar quality of tedium in English summer afternoons spent in the country. The blinds were drawn in the spacious, light and exactly furnished bedchamber, but Mrs. Latouche could see on the pale squares of holland the lightly moving shadows of the trees without, and she visualised perfectly the empty space of the sunny park that surrounded Warrington Hall.

Custom, order, tradition and conventionality lay over the whole place like spells—to Grace Latouche like a blight; as she mused in the stately quiet of the solitary mansion set in the large austere landscape she felt as if nothing occurred in this establishment that had not been sternly regulated for generations. She was sure that the servants had been in the family from father to son, from mother to daughter, that the clocks were all wound at a set hour, that no picture or piece of furniture had been moved within living memory, that Mrs. Warrington knew exactly what she possessed in her china closet, her linen cupboard and her still-room; even a great tragedy, even a possible sudden death, had not been able to disturb the immemorial tedium of this English mansion on an English summer afternoon.

Grace Latouche sighed. She had listened with decorum to the doctor's solemn talk.

"It is the crisis of the illness, we must be careful, his life may depend upon your presence."

These sentences hung in her mind. She knew that the doctor and nurse had thought her too composed; they and the servants had, of course, all been hostile. The master of the house she had neither seen nor expected to see; of the mistress she had had one glimpse. Mrs. Warrington (and Grace Latouche could estimate what the effort had cost her) had received her in the formal hall. Repelled by the cold atmosphere of the mansion, by the absence of the master, Grace Latouche had almost returned to her chariot and driven back to London, but the other woman's look had induced her to remain. Mrs. Warrington had been weeping, and her face was hideous with terrible grief.

"Her son," thought Grace Latouche, "and I suppose he's dying."

While the footman took (with disdain she was sure) her parasol and her shawl, Mrs. Latouche had gracefully played with the buttons of her pearl-coloured gloves which fastened at the wrist, and, her lovely face shrouded by the plumes of her bonnet, had listened courteously to Mrs. Warrington's difficult words. But the only one of the broken sentences that Mrs. Latouche answered was:

"You will understand that we could do no less than send for you."

To this she had replied: "And you will understand, Mrs. Warrington, that I could do no less than come. Shall I go upstairs and wait?"

"If you will be so good," said the poor trembling mother.

And Grace Latouche thought: "How cowardly of the husband to leave it all to her!"

Alone in the pale shadowed bedroom Mrs. Latouche watched those delicate waving shadows on the opaque holland blind and the languor of her tedium nearly overcame her high spirits. She was a woman who loved activity and abhorred the kind of life typified in Warrington Hall. Never could she recall any time passing so slowly as this time measured by the porcelain clock on the mantelshelf—five minutes, ten minutes, a quarter of an hour, twenty minutes, half an hour, and still the pale young man had not stirred; his outline showed rigid beneath the quilted and flourished-satin coverlet.

Grace Latouche moved the curtain again. He lay as the nurse had arranged him, sunk in the flounced pillows. On his handsome face was that look of illness and dishevelled fatigue that is so pathetic on the countenance of extreme youth. His left arm and shoulder were swathed in bandages.

They had told her that he had shot himself for love of her; the bullet had been extracted but pleurisy was feared.

"It would be a fight"—the doctor had used the conventional phrases—"for his life." And it was supposed that the best chance of safety lay in the presence of the woman for whose sake he had committed—Grace Latouche again in her mind quoted the doctor—"this desperate act."

"One never knows," that had always been her philosophy; but she was surprised and startled that Harry Warrington, of all people, should have committed this—Mrs. Latouche substituted for the doctor's words another—"folly." She had known him quite well—in Paris, in London, as she had known also quite well dozens of such young men. She was very sorry when the agonized appeal of the distracted mother had come to her little house in Cork Street; she had never hesitated a moment in her response. She was extremely grieved, she was also extremely bored, and she asked herself—Would she be expected to sit for hours in this sick chamber?

They were treating the whole affair as if it were sacred and required a kind of ritual, and she smiled to herself, having an unfortunate kind of wit, and wondered, "Was she the priestess or the victim of these solemn rites?" Would the family continue to ignore her? The Honourable George Warrington shut in his study—the Honourable Mrs. Warrington shut into her boudoir...And what—she could not help a further smile at that—did they intend to do if the beloved Harry recovered?

A maid brought in tea, an elaborate refreshment which she arrayed in decorous silence on a rosewood table.

"Mrs. Warrington, ma'am, thought you'd rather have it here than come down to the drawing-room."

Grace Latouche smiled.

"Naturally," she replied, and thought: "I suppose I am good enough for Harry's bedroom but not for his mother's drawing-room."

The maid was subdued to utter decorum, but Mrs. Latouche caught in her eye a feminine flash over the pearl-grey French gown garnished with knots of sarcenet ribbon, the heavy lace cuffs and fichu, the bonnet, the silvered feathers, the carved cornelian garniture—all so different from anything the girl would have seen before at Warrington Hall.

"Thank you, I shall do very well," said Mrs. Latouche.

"And you are to ring the bell, ma'am, if you require anything more."

"I'll not be likely to require anything more."

The tea was lavish—exquisite cakes, hothouse fruits, filigree silver, embroidered linen but she was to eat it alone. Mrs. Latouche was not offended. The maid, at the door, said very respectfully:

"Mrs. Warrington will be joining you, ma'am."

Mrs. Latouche's surprise was hidden under a casual "Thank you." She noticed then that there were two cups and two plates, and she was curiously touched. It was always difficult for her to see anybody forfeit something they cherished, and she knew that Mrs. Warrington, in coming to drink tea with her, was forfeiting something highly valued indeed.

The mistress of the house entered, the other lady rose, and they gave each other a small curtsey. Mrs. Warrington looked steadily at her son, pulled the curtains a little further on the poles as if shielding him from some visible annoyance, flicked at a speck on the coverlet and joined Mrs. Latouche at the tea-table.

"You have had everything you require, Mrs. Latouche, the maid has shown you into the other room where you can make your toilet and repose yourself?"

"I have everything I require, thank you, Mrs. Warrington, but I have preferred to remain here."

"That I can understand, I also should prefer that we remain here. If we drink our tea quietly I do not think we shall disturb Harry, and I should like to be quite near, you know, in case——"

"Certainly," said Mrs. Latouche.

Their glances just brushed each other. They were both too well-bred for their curiosity to have any offence in it. Mrs. Latouche thought, "She has never met a woman like me before, and I really cannot remember now when I last met a woman like her. Yet I understand her so well. She looks fifty, but I suppose she is not so very far from my own age."

Mrs. Warrington wore a dress of steel-blue bombazine, a matron's cap, collar and cuffs, a gold chain across her bosom. She was the type of whom people say vaguely—"I should think she was handsome once."

"It was good of you to come, Mrs. Latouche."

"Not at all, Mrs. Warrington, I could do no less, as I remarked before."

"You will understand, Mrs. Latouche, that this has all been a very great shock to me and must excuse any defect in your reception." She poured out the tea and added, above the other woman's murmured acceptance of these apologies, "You will excuse my husband, he would have wished to receive you, but he is entirely overcome and has shut himself in the library since—since the accident."

"Pray do not concern yourself," replied Mrs. Latouche; "I came here for one purpose only, that which you desired of me."

Mrs. Warrington handed her the cup of tea and took this occasion to look at her straightly—at the lovely face, the bare throat, the upper bosom above the rich lace, the auburn curls rolling over the fine shoulders, at the delicate fingers which glittered with too many and too large jewels.

"It must have been a great shock to you," she remarked.

"Of course, Mrs. Warrington, I was very distressed; I knew Harry"—fearful of giving offence she slurred that over—"your son—well, we had met in London, in Paris, and, two years ago I believe, in Rome."

"My son travels a great deal," said Mrs. Warrington, flatly. "He is very young and has distressed his father on many occasions——"

"I understand," interrupted Mrs. Latouche, gently. "When I received your note this morning I knew I could not do otherwise than come immediately, but I am afraid that you do not quite understand the situation between myself and your son, Mrs. Warrington."

The mother glanced at the bed, the other woman was almost afraid before the courage and the resolution that showed in that look.

"I must tell you, Mrs. Latouche, exactly what happened."

"Is there any occasion, Mrs. Warrington, to give yourself pain?"

"My pain is of absolutely no moment," replied the other woman with a quiver of her lip. "I have to tell you what occurred. My son, Harry, interviewed his father on the question of yourself. He wished, as you must know, Mrs. Latouche, to marry you."

Mrs. Latouche shook her head.

"No, I did not know that." She was aware that the other woman thought she was lying.

Mrs. Warrington hurried on with her narrative.

"It seems, from what his father tells me, that he became quite frantic and violent at the first hint of opposition. This is difficult to put to you without offence."

"I never take offence," murmured Grace Latouche; "it is hardly ever worth while."

"My husband is a man of most rigid principles; I dare say"—and this was spoken with an effort—"to you and your world, a narrow-minded and hard man, Mrs. Latouche. He considered that—he and I had decided"—proudly she associated herself with her husband—"that this marriage was altogether unsuitable; Harry is only nineteen and you, Mrs. Latouche—"

"I suppose," said that lady, gently, "your husband, Mrs. Warrington, described me 'as old enough to be his mother.' I was born in eighteen-ten, the year famous for the comet, the vintage and for myself, perhaps——"

"You are older than my son, Mrs. Latouche, that is admitted, and of a different experience——"

"I wish you would not disturb yourself with this recital. I can comprehend the whole interview so well...Poor Harry, I am very grieved. His father, I suppose, gave him the most absolute refusal?"

"I must admit that he did, Mrs. Latouche. There was a quarrel between them; I could hear angry voices, that is very uncommon for my husband is of a most controlled disposition. Harry left the room in an extremely agitated condition. I entered soon after to soothe his father. There was a miniature of yourself on the table——"

"There are many about," said Mrs. Latouche, "I fear even they may be purchased from various artists—against my will, but there it is. I have never given Harry a miniature."

Again she knew that the other woman thought she was lying. "She will believe, I suppose, that creatures like myself always lie," she thought, wearily, "so I had best be silent and listen to what she has to say."

"Harry went straight to the gunroom," continued Mrs. Warrington; "before I could get the brief facts from his father someone—one of the grooms—heard the shot——"

"I beg you, Mrs. Warrington, do not thus discompose yourself. You must have had a most terrible, a most exhausting experience; believe me, you have my intense sympathy."

Mrs. Warrington held herself rigid.

"That sounds grotesque," she said, breaking through her own formal decorum.

"I'm afraid it does," said Mrs. Latouche. "The situation is a little grotesque, is it not? I am doing my best, but I also must explain something to you. Harry has never asked me to marry him, and if he had ever done so I should have refused."

She saw a look of blank incredulity and offended horror in the matron's face; she added, in a deprecating tone:

"Indeed, Mrs. Warrington, I suppose it seems very peculiar to you that women like myself do receive offers of marriage and do refuse them. You see, it is rather difficult for me to get back into your world, though it is one that I was bred in. I am, by birth, a gentlewoman and I can, therefore, understand your point of view. No doubt the least name that you would give me is 'the notorious Mrs. Latouche.'"

"We tried to think of you," said Mrs. Warrington, in an unsteady tone, "as a woman whom my poor Harry loved, adored."

"It is very ingenuous and charming of Harry to adore me, but, well—he is not the only one. I have known others recover."

"I suppose, Mrs. Latouche, there have been no other young men committing suicide for you?"

"Heaven forbid!" said the lady, gravely. "And this—this accident—I cannot understand. I have given your son no encouragement, but I suppose I shall have difficulty in persuading you of that. He was no more to me than one of the companions of a companion, one of the young men who came to my salon, a friend of a friend—I hardly believe that we had three interviews alone—"

"What does any of that matter?" cried Mrs. Warrington. "There is the fact." She looked again towards the bed.

"But I cannot understand why Harry should have gone to his father for his consent to a marriage which had never been even suggested to me," said Mrs. Latouche. "The poor boy must have completely lost his sense of—of humour, shall we say, Mrs. Warrington?"

For the first time since this strange interview began Mrs. Warrington showed definite hostility towards her guest.

"Harry could hardly have supposed that he would have been refused," she said; and behind her was all the force and majesty of rank, money, position and an honourable name.

She contrived in the tone in which she uttered that brief sentence to name Mrs. Latouche "outcast" as plainly as if she had spoken the words, but the other woman's equanimity was not disturbed, she had the perhaps fatal gift of always seeing the other person's point of view and she could very well put herself in Mrs. Warrington's place. She thought to herself, not without tenderness:

"Poor woman, to her I am an adventuress, a Jezebel, why, I suppose she doesn't know the name she thinks I ought to have, and she's his mother and has no other child, and I dare swear her husband is a black tyrant, cold and violent; yet, why should I pity her? After all, she thinks herself so much my superior and knows very little of anything. She's his mother—but, what's that but a mere animal function, yet she stakes so much pride on it? I've been a mother, too, but was I any the better for it? My baby is in a Roman cemetery—she's never had that experience, why should I pity her?"

Mrs. Warrington was looking at her guest with her pale formidable eyes, at once cold and eager.

"You have overthrown all my plans," she said. "I intended—yes, Mrs. Latouche, this will surprise you very much—but I intended to ask my husband for his consent to this marriage."

"That would have meant a great sacrifice on your part, I am sure," replied Grace Latouche, quietly, "and I am obliged to you for the compliment, I honour you for your self-abnegation. Believe me, I could not, in any circumstances have married your son."

"But why?" asked Mrs. Warrington.

"Must I give you my reasons? He is too young, he—well, I don't love him, Mrs. Warrington."

"But love," stammered the matron, as if she had not taken that word over her lips for many years; "but love, Mrs. Latouche, is this a question of love?"

The other lady interrupted these stammerings:

"I suppose you think, Mrs. Warrington, that with women like me love does not enter into our—shall we say, without offence—our bargains? Marriages can be bargains, too, you know. I have been married twice, but each time for love. Love does not always last, you know; but that does not say that while it endures it is not genuine. But I speak of affairs which have not been marriage, but which have had in them love and, while they lasted, fidelity. I do not want to hurt you, I wish to make it clear why I should not marry your son."

"You will find it difficult to convince me of that," replied Mrs. Warrington, and her tone was now stern as if she were aware that she dealt with a sly and subtle adventuress.

"How can I convince you?" smiled Grace Latouche. "I must convince you, there can be no false pretences about this. I have come to be near your son until he recovers consciousness, I want myself to make him see reason; I want him to tell you before me that I never encouraged him; there was never talk of any entanglement."

"This is extraordinary," murmured Mrs. Warrington.

"Believe me, Mrs. Warrington, I find it most extraordinary. I am deeply distressed, I wish to assist you, but you must believe me. Perhaps," she added, "you will believe me if I tell you that I am in love with someone else."

Mrs. Warrington flushed a dull unbecoming red.

"There was another name mentioned," she muttered, looking aside. "I heard it—Count Alexis..."

"Count Alexis Poniatowski," said Mrs. Latouche; "yes, his name has been connected with mine. You will have heard, perhaps, that he has stayed at my cottage, Villa Violetta, outside Parma!"

Mrs. Warrington appeared to shudder and Mrs. Latouche smiled.

"I suppose that all sounds very gaudy and theatrical to you? But, really, there are violets there, you know, fields of them, that is how the Villa gets the name. I know," she added, in a tone of sympathy, "when one is in England on an afternoon like this or, even more so, on a Sunday, these things seem quite impossible, but they are there. I believe you would really like the Villa Violetta and the violets. They have the three colours in two varieties—double and single; white, deep purple and light mauve. And, as for Count Alexis Poniatowski, he is most interesting and cultured—you must not think of him, please, because of his name—as I know English people do—as quite a cheapjack, you know..."

Mrs. Warrington was silent, she seemed to wither and withdraw into herself.

"But it is not of this gentleman I would speak, there is another man; I have met someone who, if the chance offered, I would marry."

"But he has not asked you to marry him?" asked Mrs. Warrington, who seemed to feel her way stiffly about an alien and hostile world.

"No," said Mrs. Latouche, "he has not asked me. I met him in romantic circumstances, in France; I have entertained at my little house in the rue du Bac; we have corresponded. It is quite a delicate little affair I am telling you of, Mrs. Warrington; I want you to know where my heart lies."

Mrs. Warrington rose.

"Mrs. Latouche," she said, sternly; "I cannot conceive how Harry could have been so mistaken. You must excuse me for troubling you—I had no conception that this could be the truth; you must forgive me if I doubt, even now, it is the truth."

Mrs. Latouche also rose.

"We must not dispute," she said, sweetly; "we might awake your son."

"But what am I to say to him," exclaimed Mrs. Warrington, "when he does wake? It is almost better that you went, that he did not see you."

"That is as you please. I came here on your urgent summons and also because I had to tell you that there was some mistake."

"And I suppose," said Mrs. Warrington, leaning against one of the posts of her son's bed, as if unable any longer to stand upright without support, "that it was stupid of me to expect any candour from you."

"I suppose you've heard dreadful things of me, Mrs. Warrington?"

"No," replied the other woman, "I have heard nothing at all, except your name, and that is quite the worst, you understand, when one hears nothing of a woman but her name, and just notice how people look..."

"I see," replied Mrs. Latouche, thoughtfully, "that is how it is done, is it? I have often wondered how ideas about women like me are conveyed to women like you; now I understand—just the name and a look."

"We—we do not discuss you or your companions at all," said Mrs. Warrington, breathing quickly.

"No, I understand, I was brought up like that myself, Mrs. Warrington. Now, I am afraid we disturb your son, he is beginning to move a little. Do you want me to go or stay?"

In an instant, Mrs. Warrington was all maternal terror.

"No, you must stay, indeed you must; your name was his last word." She hurried to the door, whispering in the pompous doctor and the officious nurse, who were waiting in the anteroom.

Grace Latouche moved to the head of the bed. The young man was stirring as if from a natural sleep. She ventured to touch his hand, then his brow—surely of a normal coolness? The hastening doctor confirmed her hopes, the fever had fallen, the young man had sunk from the last swooning delirium of illness into a healthy sleep. He opened his eyes, conscious, clear-headed; he smiled at his mother and Mrs. Latouche. In tones of guarded tenderness Mrs. Warrington said, bending over the pillow:

"You see she is here, Harry; I sent for her at once. She came and has been waiting by your bed."

Mrs. Latouche despised herself for noticing the accomplished way in which Mrs. Warrington dropped into the part of the ministering angel, and the delicacy with which she stressed her own sacrifice in sending for the outcast.

"Thank you, Mother, I'd like to speak to her," whispered Harry.

"Not now, my dear boy, you are not strong enough."

"I'm quite strong enough, thank you, Mother, and I'd rather get it off my mind."

"Perhaps you could tell me in a very few words," said Mrs. Latouche, looking with soft compassion at the pallid face and shadowed eyes; she was thinking of herself, too, for was she not quite indifferent to the young man save as regarded pity? And how impossible to spend the night in Warrington Hall, with a master who would not see her and a mistress who had to make an effort not to draw her skirts aside! The young man, Mrs. Latouche admitted reluctantly to herself, must be, what she had never suspected him to be, a fool.

With her (no doubt unconscious) air of renunciation and sacrifice the mother tiptoed away, followed by the solemn doctor and the blank-faced nurse.

Grace Latouche's manner became more natural when relieved of these formal presences. She sat down by the bed, reached for the sick youth's hand and said, reprovingly:

"Why, Harry, how did you come to be so foolish? I would hardly have believed it. I thought you was so sensible."

Harry smiled and not, as she noticed instantly, in any languishing or lovesick fashion.

"What have they been telling you?" he asked.

"That you asked your father's permission to marry me, that when he refused you went off in a pet and shot yourself. Your poor mother is in torment and, I suppose, your father is too; though for him I have less pity. And what were you doing with my miniature? I never gave you one."

"They have got the whole thing wrong from beginning to end. They sent for you?" whispered Harry.

"Yes, but ought you to talk, my dear?"

"I must talk. You won't wish to stay, will you?"

"Well, I don't want to if I can get away. But, do tell me what it all means. You don't look to me as if you were dying of love."

"The shot—that was an accident—a confounded accident. I was in a temper and went to the gunroom, started cleaning a pair of pistols and didn't notice that one was loaded... That's all there is to that."

Mrs. Latouche laughed with relief.

"Why, let us have your mother in and tell her immediately." She reached out her hand for the bellrope. But the boy said in a thick whisper:

"Don't, please don't; I've got something else to tell you—I'd rather she went on thinking that I did it because of you. You see, my father and I did have a quarrel, and about you——"

"About me?"

"Yes, won't you please come closer to the bed? I'm not very strong yet and I feel that I shall go to sleep again, but I want you to help me—"

"Of course, I 'llhelp you, Harry, I came here to help you; but I feel so relieved that you didn't do it intentionally, and because of me. Tell me now, honestly, Harry, I didn't lead you on and make you fall in love with me, did I?"

The dark head on the sumptuous pillow shook "No."

"Oh, I am so relieved, I never wanted to do that to anyone. I have told your mother, and I'd like to tell you, Harry, there's someone else whom I met in Paris——"

"I don't want you to tell me about that," said the boy. He closed his eyes and appeared exhausted, but his words though low were distinct.

"Why?"

"Well, Mrs. Latouche, you see I know all about it."

"You know all about it—about my little romance in Paris?"

"Yes, and that was what the quarrel was about. You did give a miniature to that man, didn't you?"

"Yes, in a little violet morocco case."

"Well, if you were to go into the library now you'd find it there, unless he's destroyed it. You see, Mrs. Latouche," he moved his head so as not to see her, "that man is my father. He was staying at the Embassy in Paris and he met you in the Luxembourg—someone told me about it. He didn't give you his real name. My mother knows nothing at all."

Grace Latouche laughed quickly, she could always pick herself up quickly after she had been thrown: she said swiftly to herself—"After all, is the marriage of this boy's mother so much? I guessed he went under an assumed name and was married. But, how infinitely more charming and interesting than Harry—Harry's father! the man whom I imagined to be a dull provincial tyrant!"

"But what had it to do with you?" she asked, "and how did you venture to speak to him about it?"

"I don't know—it came up—I made an occasion...then there was the miniature and one or two other things. I could see that he was really—well——

"In love, I suppose?" said Mrs. Latouche.

"I don't like to think that."

"What were you considering?"

"Just one person—my mother."

"That woman," whispered Mrs. Latouche.

"Well, she's also in love—if you like to put it that way—and has been for the last twenty-five years. I suppose he and I are all she's got, and—I'd rather she thought I was a confounded fool, infatuated with you, and shot myself, than know——

"—that he, perhaps, came to stay with me in the Villa Violetta?"

"Yes. You won't let him do it, will you?" he added with a childlike accent.

"Your mother is a stranger to me, Harry, and I don't know you very well. I have long since ceased to be bound by—just convention, tradition."

"I thought you'd be sorry for her."

"Why shouldn't she be sorry for me?"

"I don't think there's been anybody else, and if you were to leave him alone...You see, he's really fond of her. They've been extremely happy until now." His voice was becoming very faint.

Mrs. Latouche rose.

"You mustn't talk so much," she said.

She put on her bonnet over her smooth fashionable curls and tied the sarcenet ribbons under her chin.

"I'll go now. I suppose he excused himself, when she found the miniature, by putting it on to you?"

"Yes. What are you going to tell my mother?" he asked, drowsily.

She did not answer but touched the bell.

Instantly, Mrs. Warrington, the doctor and nurse were on the threshold.

Mrs. Latouche swept up to them.

"Harry and I have had a candid talk," she said. "He is quite cured of his folly, his illness has effaced his—whimsey. It often does, you know—a kind of fever that passes with a little bloodletting. He will not disturb you with his 'infatuation' any longer, Mrs. Warrington. He is quite sensible."

A flush and tremble of joy broke over Mrs. Warrington's features and by that the other woman could gauge how deep her sufferings had been, how hard the restraint she had put on herself. She held out a hand which she had not done before. She followed Mrs. Latouche to the door, while doctor and nurse decorously bent over the bed where their patient was again falling into a natural drowsiness.

"Thank you, Mrs. Latouche."

They were out on the landing. Mrs. Warrington added, impetuously:

"I am sure you are a good woman at heart."

"Thank you, Mrs. Warrington, and please don't take my hand if you'd rather not..."

"I should not like to hurt you—"

"I'm afraid I've hurt you, Mrs. Warrington."

"Well, after all, there's a good deal I don't understand. I should like to take your hand, and, please, may I wish you good luck and felicity with whomever it was—the man you said you would marry if you had the chance?"

"Thank you, again."

They clasped hands and dropped a little curtsey.

"Please go back to your son, Mrs. Warrington."

Grace Latouche went alone down the stairs. Behind her tinkled the bell to summon a footman. She walked slowly. On the next landing were two large doors. The footman waited for her before one of them. She asked him coolly:

"Where do those doors lead to?"

"One, ma'am, to the library, the other to Mr. Warrington's study."

Mrs. Latouche paused, slowly buttoning her short pearl-coloured gloves at the wrist.

How easy to scribble a line on a leaf torn from her tablets, to send the footman away on some excuse to fetch her shawl or parasol, and slip a message under the door. Or, again, how easy to hand it to the footman, saying, "Pray take that to your master."

But what would that message be? "I have found out who you are, it makes no difference, meet me in the rue du Bac or in the Villa Violetta."

Easy to let him know that she was not outraged, or shocked, or frightened; that, in brief, she really loved him beyond all such considerations. Did she not owe him so much outward compassion? Had he not, enclosed in there, suffered more than his wife, or Harry, or herself? Harry would recover. Mrs. Warrington would always have Harry.

Grace Latouche took a long time to button her gloves. She told the footman to go ahead of her, to get her parasol, her shawl, to see if her chariot were ready. Poor Mrs. Warrington had wished her, with what pain and effort she, Grace Latouche, could value—"Good luck" in her love affair, and she had said, "I believe you are a good woman at heart." Mrs. Latouche knew what Mrs. Warrington meant by "a good woman."

She leant against the door, a charming figure in her frivolous Parisian dress of flowing silken folds, her furbelowed bonnet and rich laces. She seemed a butterfly that the lightest breeze would blow to its destiny. She did not touch the handle of the door, nor write a note to slip underneath. She said, very low, an echo of a whisper:

"Good-bye, my dear," and went downstairs, got into her chariot and drove back to Cork Street.

When she arrived there she lowered her veil for her face was as disfigured from weeping as had been Mrs. Warrington's face when she had met her that morning.

WHEN she could no longer hear the last echoes of the departing carriage-wheels, a sense of desolation overcame Lucy's already drooping spirits. She was pierced by the childish pang of "being left behind," that indescribable regret which comes from seeing off a gay party of pleasure from which you are the only one omitted. Even most of the servants had gone on the picnic and Lucy was alone with Mrs. Bartlet and a maid. Three carriages and the light wagonette, laden with laughing people and baskets of provisions, had driven off merrily to Okestead Woods to hold there the great picnic for Emily's birthday.

Only Lucy had been left behind.

Lucy stood at the window of the drawing-room and looked on to the long terrace. It was early morning and already very warm. To-day would be cloudless and very sunny, everyone had predicted that, as amid laughter and merriment they had entered the carriages, all eager for the picnic. Lucy had helped to pack the baskets and tie the ribbons round the birthday cake. She had felt rather like a heroine, for everyone was so sorry that she was not able to join them in the long-anticipated festival. Her sisters, Caroline and Emily, had clung round her neck, almost with tears in their eyes amid their kisses.

"Dear Lucy! Sweet Lucy! what a pity! How unfortunate! Are you quite sure you cannot come?"

Then her mother, so tender and regretful, and her father disappointed in the midst of his pleasure, and Mary Fenwicke, her close friend, protesting that she would not go but stay behind to keep Lucy company; and Kate Sorrel, offering to return at midday and "see how Lucy did"; and Aunt Charlotte who had had to be almost pushed into the carriage, so desirous was she of remaining with Lucy; and Uncle Ambrose, with hearty kindness declaring that it was all nonsense and that he was sure Lucy could come with them. Then the young men, Mr. Matchet, Mr. Lemoine and Mr. Gray, all declaring that the picnic would be robbed of its brightest lustre if Miss Lucy did not condescend to keep them company, until Emily began to pout in pretence of a jealousy and all laughed together; but Lucy continued to excuse herself. Really, she could not come; yes, she had felt like a heroine then, the centre of all that love and tenderness, affection, consideration and kindness.

Now that they had really gone without her, now that the last farewells had been waved and there was silence in the house, in the gardens and on the terrace, and the long sunny summer day quite empty of events was before her, Lucy felt no longer like a heroine, but rather like a naughty child who, for some misdemeanour, has been deprived of a treat. She began to wonder why she had refused to go. Certainly, last spring—that late, long cold spring—she had been quite seriously ill, but now she was completely recovered and, though the doctor had said she must not exert herself or become excited or fatigued, she had not given much heed to that mandate until to-day. But this morning, after waking up early and joining the chattering group who were congratulating Emily on being nineteen years of age, and after presenting the beloved sister with a sarcenet bag exactly flowered by herself, she had felt a sudden languor and a complete inability to join the picnic, a panic terror at the thought of being in the midst of all that cheerful good company and overcome by sudden illness; so she had confided to her mother that she did not feel able to go and Mrs. Middleton had anxiously agreed that it would be far better for Lucy to remain quietly at home with Mrs. Bartlet.

The picnic was to be at Okestead Woods and the drive was long; the day, too, would be long, for they intended to stay until the full moon was high. Two of the gentlemen had flutes and there would be dancing and singing, perhaps a charade. Yes, it would all be very exciting and fatiguing, and it would be far wiser for Lucy, if she felt nervous or languid, to remain at home.

Lucy did not really want to remain and she disliked very much the idea of giving herself any importance, or, possibly, clouding the pleasure of others. Yet there was an ominous throbbing in her temples, a sense of faintness over all her limbs, a palpitation in her bosom which warned her that if she joined the picnic she would be but a burden to others and a misery to herself.

Well, the question had been decided and she had been left behind, standing on the terrace in the sunny early morning, with silence about her and a long empty day before her; presently this same warmth and silence began to soothe her. Her wave of disappointment passed and she was grateful that there was this long spell of quietness ahead; she would have nothing to do for hours and hours, but sit in the warmth, or perhaps sleep, or gossip a little with Mrs. Bartlet, her old nurse. Yes, after all the regrets had gone, she was glad that she had found the courage to say that she could not face the picnic.

She felt very languid and fatigued, it was delicious to be alone and know that there was absolutely nothing to do. The sun would go on shining for hours and after that there would be the moon. There was no cloud in the sky nor any care in her mind; even that piece of needlework for Emily, which had rather weighed on her (for she was often weary and had to force herself to do the fine embroidery), even that was finished. She had learned, too, her new piece on the harp, which had been of some difficulty; no need to worry any more over that. No one would come near her all day, for everyone knew that this was Emily's birthday and that the whole family always went on this fourth of August to Okestead Woods.

Mrs. Bartlet would give her the luncheon she most liked; afterwards, perhaps, she would go and lie in the chaise longue under the cedar trees, or wander into the warm garden where the peaches bloomed, or, perhaps, if she felt strong enough, go as far as the wishing-well in the woods of Ruslake Manor.

Mrs. Bartlet brought a chair out on to the terrace and without fussing, folded a long white silk shawl with a heavy fringe round Lucy's frail shoulders.

"Oh, Mrs. Bartlet, but the sun is warm!"

"Never mind, my dear, it's possible you might get a chill, even on a day like this. Now you don't feel moped and melancholy, do you, the others being gone?"

"Well, I did a little at first," confessed Lucy shyly, "but now somehow I feel glad that there's nothing to do; isn't it delicious here, Mrs. Bartlet—like one of those places in a fairy tale, under an enchantment, you know."

She settled herself into the comfortable chair and drew round her muslin gown the silk shawl, she liked the feel of it on her bare arms and the warmth of the sun coming through the silk. She folded her sandalled feet on the footstool Mrs. Bartlet had brought and smiled at her kind attendant.

"It seems a sad shame, miss, that you should be denied the pleasure of the picnic after such a long preparation and looking forward to it. That was it, you did too much and overtaxed your strength. You know the doctor said that you'd got to be careful."

"Well, I am being careful to-day," smiled Lucy; "I am just going to lie here and do nothing."

Mrs. Bartlet looked at her with tender affection and thought, with a swelling pride, how beautiful this young nursling of hers was—Miss Caroline and Miss Emily were pretty girls, but Miss Lucy was like an angel, the old nurse believed. She had clusters of pale hair, a complexion so delicate and with such a wild-rose stain in the cheek, features of so pure an outline and eyes of such a radiant blue... Mrs. Bartlet considered, with a kind of satisfaction, that probably the picnic had been spoilt for all the young gentlemen by the absence of Miss Lucy. She had seen Mr. Gray's look when he heard the news...

"Well, they weren't any of them good enough for Miss Lucy; there was no one in the whole neighbourhood good enough for Miss Lucy, and that was the trouble of it—no one good enough."

"Shall I bring you your needlework, miss, or a book?"

"No, thank you, Mrs. Bartlet, I'll just do nothing; for a while, at least."

Alone on the terrace Lucy also was thinking of Mr. Gray. She knew then, what she had not been quite sure of before, that she was glad to be rid of Mr. Gray and his little timid attentions; she "half"-liked him and she tried to puzzle out why only "half." She had had of course insistent and secret dreams of what a young man should look like and how he should behave, and, to a certain extent, Mr. Gray had fulfilled the ideals exacted by those dreams, but only if she looked at him glancingly, sideways; if she ventured (and it was not often that she had so ventured) to gaze at him directly, or to consider him seriously, not only had he not fulfilled her ideals, but there was something about him that irritated, almost disgusted, her—little imperfections which, to her fastidiousness, had been distasteful, just a look, or an accent, or a line wrong, and she had wished to flee him for ever. Yes, she was glad to be rid not only of the excitement, hurry and confusion of the picnic, but also of the courtesy and attention of Mr. John Gray.

As the sun grew stronger, rising in a steady blaze behind the old red-brick manor-house, Mrs. Bartlet brought out a parasol and fastened it cleverly above the chair; Miss Lucy did not yet care to move, but lay there languidly.

Large single red roses spread their petals over the brick front of the house. She gazed at these two shades of colour close together—the hard, purplish bricks and the frail crimson roses; even as she looked some of the petals fell from the golden stamens and dropped on the terrace; white butterflies, the quintessence of summer luxury and idleness, floated past. When the faint sweet summer breeze stirred the heavy blue air, a waft of perfume of fruit and flowers was borne to Lucy's nostrils.

She could not remember the house ever having been so empty before; when she turned her head she could see through the long windows into the drawing-room—all the familiar possessions, her little desk, her harp, Emily's workbox, the portrait of their grandmother, the marble chimneypiece, the shelves with all the books she had known since childhood—never before could she remember the drawing-room empty like that.

Then all the rooms above—the bedrooms, the little sittingroom—all empty! their windows open on the summer air. She began to muse on how old the house might be, and how many generations of Middletons might have passed up and down those shallow stairs from the drawing-room now empty to the bedrooms now empty...

How old was the climbing rose tree, glowing against the bricks? How many years since those steps had been laid down which led to the stone-flagged garden, and the sundial amidst bushes of myrtle and rosemary? For the first time in her life Lucy Middleton did not seem herself to belong definitely to her own time and generation, but to be part of the silent empty house, the silent empty garden, and one of the company of all those other people who had once crossed this terrace.

She fell asleep, and when she awoke felt much better and declared to the watching Mrs. Bartlet that she was indeed quite recovered and that if the picnic had been starting now she would have been ready to join them. She looked indeed, the gratified nurse thought, not only well but blooming...for a long while she had not coughed.

Lucy went into the empty drawing-room where the blinds were drawn against the sun and ate some of the carefully-prepared luncheon, specially set for her there. Mrs. Bartlet remained to keep her company and they began talking about Okestead Woods. That, apart from Lucy's absence, had been the one blot upon a charming day. Mr. Middleton had long wished to purchase Okestead Woods which had been the scene of all the family's picnics and which lay exactly on the borders of his estate.

"I do think Lord Weybourne might sell them to the master," lamented Mrs. Bartlet.

And Lucy said: "Well, he might answer—Father has written twice, you know, but there has been no reply. Of course Lord Weybourne is always in London, but there's the steward. I suppose there is an explanation."

"I suppose so, miss; the master would have been delighted if to-day, Miss Emily's birthday, he could have said the woods were his. And, after all, they're not worth anything, and with all the land there is belonging to the Hall one wood or less wouldn't make any difference."

"I expect it's all right," smiled Lucy. "Father will hear soon, but, as you say, it would have been much pleasanter if he could have heard to-day."

After luncheon she went upstairs, according to the dainty habit of a lifetime, to change her morning dress. She put on (though she was alone and to gratify what whim she knew not, for she was very free of vanity) a fine figured silk with a broad blue ribbon fastening under her breast. Then she came downstairs and, taking out her harp, played over her piece; then went to the harpsichord and sang over the song that she had been diligently learning:

"Angels ever bright and fair,

Waft, O waft me to your care!"

"It's a sad thing, that, Miss Lucy."

"Yes, I suppose it is in a way, but it's pretty, too, and father likes it. I think I'll go for a walk now."

"I shouldn't do that, Miss Lucy; every time you get a bit of strength you mustn't use it up. You sit out on the terrace again and I'll get you presently a dish of tea."

"Why, I've only just had luncheon."

Lucy went out on to the terrace. The sun was very strong and she was glad of the parasol, even in the shadow of the house there seemed a dazzle of light. The perfume of fruit and flowers was stronger and she could smell the box and laurel, the rosemary and myrtle growing in the flagged garden. Her heart was quite free—empty as the house and the day; she mused impartially.

Mrs. Bartlet, finding solicitous occasion to pass through the drawing-room and look at her young mistress, thought resentfully: "It's a pity there's no one—not anyone good enough."

Lucy came in from the terrace and asked for the white kittens. Mrs. Bartlet brought them and she played with them on the cushions of the long sophy between the windows.

"Do you know, Mrs. Bartlet, I do think I ought to go for a walk; I am quite well now and I feel it was so silly of me not to have gone to the picnic."

Mrs. Bartlet did not answer; her quick trained ear had heard a footstep outside and she said, with the utmost surprise:

"Why, there's someone here!" and stepped out of the tall French window, expecting she knew not whom, but prepared, with stern dignity, to send away any possible intruder.

A young man had crossed the terrace and stood directly fronting Mrs. Bartlet. He was, in the housekeeper's eyes, a very manly and splendid figure; he wore a uniform, tagged and braided; he was dark, handsome and agreeable. He said, smiling pleasantly:

"Why, I thought everyone was out; I've been round to the front entrance but could make no one hear. Could I see Mr. Middleton or Mrs. Middleton?"

"The family is out sir," replied Mrs. Bartlet, "and most of the servants. This is Miss Emily's birthday and everyone has gone on a picnic."

"How odd that I should have chosen to-day," said the young man, with an even more charming smile. "I have come with a message from my uncle, Lord Weybourne; it's about Okestead Woods. Two letters have been unaccountably overlooked and Lord Weybourne was very anxious that Mr. Middleton should have an answer to-day. I am staying there and offered to come over in person."

Mrs. Bartlet knew perfectly well that she should have taken this message and courteously dismissed the young man, repeating her assurance, "The family is out, sir, there is no one at home," but Mrs. Bartlet hesitated. She knew who he was—Captain the Honourable Simon Greeve, Lord Weybourne's heir—the man who would be master of that great name and that great estate, a soldier on the famous Duke's staff, a hero, too, no doubt, and handsome as the prince in the fairy tale.

Mrs. Bartlet's thin face flushed. How odd that Miss Lucy should have stayed behind just to-day! Why, he made all those other gentlemen, Mr. Gray, Mr. Matchet and Mr. Lemoine, look like so many broomsticks.

Captain Greeve, seeing the housekeeper's hesitation, said:

"Well, perhaps you would give that message to Mr. Middleton, and say that he will hear from my uncle tomorrow?"

Mrs. Bartlet moved aside from the window; she replied: "There's Miss Lucy at home, sir, if you would like to speak with her; she understands all about the Okestead Woods. You see, they used to play there as children, and it's become like home to them." And she added, with an unconscious note of invitation in her voice, "Wouldn't you care to see Miss Lucy, sir?"

"Of course," smiled Captain Greeve, "I should be absolutely delighted to speak to Miss Lucy. Will you ask her if she would care to receive me?"

Mrs. Bartlet went inside the drawing-room where Lucy was playing with the two white kittens on the long sophy.

"Here's a visitor for you, Miss Lucy."

"Oh, Mrs. Bartlet, I couldn't see anybody to-day. I heard you talking—it's a man, isn't it? Please send him away—with compliments, you know, and say that my father will see him to-morrow."

"But, Miss Lucy, it's Captain Greeve from the Hall and he's come about the Woods."

"Let him leave a message with you," whispered Lucy; "do not let us talk here so long, it seems discourteous."

"It is discourteous," said Mrs. Bartlet, firmly; "that's just what it is, miss. It's a hot afternoon and he's walked over from the Hall, and you can do no less than ask him in and give him a dish of tea."

"Do you think so?" asked Lucy, doubtfully.

Mrs. Bartlet had always been a firm model of all the decorum, the proprieties and the conventionalities, and her advice surprised and impressed her charge.

"You'll like him, Miss Lucy," whispered the housekeeper.

"Well," smiled Lucy, "I'm bound to see him now after this long delay, for it would seem as if you had described him and then I had refused; so ask him to come in, please."

She stood up, putting the kittens down on the sophy, and came forward as Captain Greeve entered through the tall French windows. Mrs. Bartlet repeated:

"A visitor for you, Miss Lucy, Captain Greeve!"

The girl dropped a little curtsey, the young soldier bowed. She had never seen a man like this and was too innocent to disguise her wonder, and he had often heard of absolute loveliness but never before beheld it...they looked, therefore, at each other for a second without speaking; both given a certain ease by the sense of the empty house and the empty garden and park about them and the languorous sweetness of the full summer afternoon.

"I'll bring a dish of tea, miss," said Mrs. Bartlet, with a tone of triumph in her voice.

"Please, will you be seated," said Lucy, "and tell me—you have come about Okestead Woods?"

He said yes, and how strange it was that he should have chosen the day when all the family were abroad at that very place.

"Indeed," smiled Lucy, "and it is strange that I was not there, too; but I was ill last spring with a cough and to-day felt languid, but now I am completely recovered."

"You would like me to go?" he said. "I intrude upon your kindness; it is but a matter of leaving a message."

"Please stay," said Lucy, "and please be seated."

He took carefully the satin chair by the hearth and she sat again on the sophy, and she thought how the whole room, nay the whole house, the whole manor, seemed but a background for his personality.

"Lord Weybourne, Miss Lucy, is very willing to sell the Woods; he is sorry that there has been a delay in answering the letters."

Lucy flushed:

"Oh, father will be delighted. We have always wanted them, you know."

"Why?" smiled Captain Greeve, "are they different from any other woods?"

"Well, they are to us; we have always gone there for picnics, there is such a splendid view, and little groves, and certain trees that we know so well and even call by names. You," she added shyly, "you are not often here, you would not know the places, I think."

"No, I have not often been here; once or twice as a child, but I do not think we met."

"No, we have never met before."

"Miss Lucy, isn't that odd?" asked the young soldier.

And as her gentleness, her loveliness, her simplicity further enchanted him, he could not keep some tenderness from his voice.

"Is it not odd that we do meet at last, like this? I thought, even as I left the Hall, there was some magic in the afternoon."

"Is there," asked Lucy, "some magic abroad? It has been very still here. I have been alone all day, but not lonely."

She added in her heart, "It was this that I was waiting for and, therefore, was quiet and content." Aloud she said, "I watched the roses, just a few petals fell, it was so warm."

"The very height and crown of summer," said Captain Greeve.

Mrs. Bartlet carried in the tea and Naples cakes; Lucy noticed that she had brought in the Crown Derby service and the best silver as if this were a festival, and that her face was set in lines of rare satisfaction and pleasure.

Miss Lucy had never been alone with a young man before, but she was not shy nor frightened, for this seemed some familiar friend. Her face flushed to a more delicate rose blush and her blue eyes sparkled with an even more radiant brightness.

With ease, with grace, with a half-compassionate, half-admiring tenderness the young soldier allowed her to entertain him. They talked together of little things—of music, of flowers, of the long, sweet, fair summer that had followed the desolate winter and spring, of Okestead Woods, of the picnics, the games and plays that had been held there by happy children, and of all other trivial, charming matters which, on their lips, were neither tedious nor insipid. Soon, all that they said had a delicious interest for each other. When she spoke, he listened as if all her words were as new as charming; when he spoke, she was silent to hear, as if her ears were ravished by new and unheard-of delights.

When Mrs. Bartlet came to remove the tea equipage Captain Greeve told Lucy that he was home for a long leave and that he must plan a dozen excursions for her to recompense her for the picnic missed to-day. Did she know this and that? Would she go here and there?

"But, 'tis I who must guide you," laughed Lucy; "we have some charming places in the Manor grounds."

"How easily they talk together," thought Mrs. Bartlet, with a swelling heart; "they look like accepted lovers already. Why, this has been a sheer stroke of Providence, that she should remain behind and he see her by herself like this, not surrounded by those chattering misses, Kate Sorrel and Mary Fenwicke, or even by her two sisters, Emily and Caroline—but, all by herself, in her beauty, her dignity and her grace—the sweetheart!" Here, at length, was a lover worthy of her, who had walked in out of the still summer afternoon just like the prince in the fairy tale who came to wake the Sleeping Beauty.

Mrs. Bartlet had given the gorgeous young man many shrewd looks. She knew, and there was a pang in that, that he was Miss Lucy's superior in birth, wealth and fortune, but she had never heard any evil of him and she trusted him; he had honest eyes, a serious manner; she could swear he was not one '"of your young 'flyaways,' who make a play of catching maidens' hearts like butterflies in a net. No, there was respect in the way he looked at Miss Lucy and, more than that, a breath-catching surprise." He seemed to Mrs. Bartlet's triumphant, piercing gaze, like a man amazed at the extent of his own good fortune, and Miss Lucy—Miss Lucy was transformed; Mrs. Bartlet herself had not guessed how gay, how charming, how lovely she could be...she had bloomed like a flower, long-closed, suddenly struck by the sun and opening wide to the golden heart.

"Oh, Mrs. Bartlet, I am going out! I am going to show Captain Greeve the beech grove and the wishing-well and the little stream with the forget-me-nots, though it's rather late to see the flowers!"

"Well, miss, don't tire yourself," smiled the housekeeper. "You know you were supposed to rest to-day."

"But, indeed I am quite recovered now."

"You must not let me take her," said the young man, "if she should remain indoors."

And he looked humbly at the housekeeper as at the lawful possessor of this new-found treasure. But Mrs. Bartlet was not going to interfere with Providence, nor do anything to mar this sudden and perfect idyll.

She hurried upstairs and fetched her mistress's straw bonnet with the white sarcenet ribbons, the azure shawl which matched the blue ribbons round Miss Lucy's waist, a little reticule with handkerchief and vinaigrette within, and the long white silk gloves and brought them down, that Miss Lucy might not lose a single moment of Captain Greeve's company by going up to fetch the things herself. The usual cautions were on her lips but not in her heart as she bade them "Godspeed!" as if they were going on a long magic journey.

"You won't go far, and you won't tire yourself, Miss Lucy. You'll be back before it's dark, and I can trust you, Captain Greeve, sir, for indeed she's not very strong yet."

"Oh, but I could walk miles!" laughed Lucy, "and I am absolutely weary at being penned up in the house. If I had a carriage I would go off to Okestead Woods and join them all and tell them the good news!"

Mrs. Bartlet watched the two figures crossing the terrace. How well matched in youth and grace and joyous pleasure in the summer day! Slowly, side by side, they walked, he accommodating his step to hers, she laughing. Mrs. Bartlet could not remember when she had heard Miss Lucy laugh like that. Twice she turned back to wave, her sweet face shadowed beneath the deep bonnet, her sweet figure shadowed by the parasol.

When they came to the steps Mrs. Bartlet saw that he tenderly took her elbow to guide her little feet.

"Ah, well, if ever there was a match made in Heaven that was; maybe he could marry a fine lady with a pot of money for dowry; but he's seen the world and knows a sweet face when he sees it, and he's not likely to find a sweeter than Miss Lucy's; and she, God bless her! has found somebody worthy of her at last."

They crossed the garden and paused to mark the time upon the sundial, he lifting his fob to set his watch by it, and then they went on across the flags, and she was conscious of a most delicious warmth—the sunshine penetrating her thin dress on to her limbs. She must show him the kitchen garden, the peaches and the plums behind the netting, or preserved in linen bags, and the slow, lazy buzzing bees and wasps; the withering currant bushes gave out a pungent sweetness, the large black fruit hung under the curling yellow leaves; and then, like a child enjoying unobserved mischief, she must peep into the greenhouse and show him the exotic plants growing there and the frames for winter violets. Then into the park and to the beech grove, a spot she had always loved where the shade was thick and golden.

It was like a temple—the floor paved with last year's beech-mast, the roof the interlaced leaves of the trees through which the sun poured, rendering them transparent yellow-gold like cloudy amber.

The young man could hardly believe that she was mortal. She had caught his heart and his fancy; the suddenness of their meeting, the loneliness of their meeting-place, the off-chance that had brought them thus together—all this combined to give her a glamour of which he was almost afraid; he believed that if he put out his hand to touch her she would vanish. He tried to use his reason and analyse her coldly, but this he could not do, there was certainly something about her which eluded him; she was, he could have sworn, different from any other girl or woman he had ever met; her pure gaiety, her extraordinary high spirits, something crystal clear and radiant in her person and her manner, her light joyousness, and yet the utter absence of even a trace of coquetry. So could he have imagined a goddess or a fairy treading the earth for a few hours.

They passed through the beech grove into a deeper wood where the sun could scarcely penetrate and came to the wishing-well in a deep grove with ivy, maidenhair and harts' tongue.

"In the summer, earlier, there are violets," she said; "this is called Diana's Wishing-well, or, sometimes, the Nuns' Wishing-well. Diana was, in a manner, a nun, you know."

She found the cup chained to the rock amid the tangled ferns.

"See, you must drink, holding it in both hands, and wish."

She dipped it into the water and held it, brimming full, up to him, their hands met beneath the bowl and the pure drops fell upon their fingers.

"I wish that I may never be less happy than I am to-day, Miss Lucy, but that is perhaps asking too much of the most indulgent of gods."

"Now you have spoilt your wish, for you must tell none what it is."

"May I not have another, Miss Lucy?"

"No," she answered, "there is only one wish for each, and, if you speak it, it is lost."

"You have yours, Miss Lucy; your luck has not been broken."

"Why, I had mine long ago, sir, when we were all children. We came here on our several birthdays and had our wishes."

"And what was yours—but I suppose you must not tell it me, even after so long?"

"Yes, I may tell it now—after a year or so one may speak; but it was nothing, or something foolish—I think it was that I might not live to grow old."

They went on into the wood—O lovely day! O serene afternoon!

They did not know where they went or of what they spoke, neither cared to measure the extent of their enchantment. On several occasions he did force himself to remember the housekeeper's injunction.

"You are sure you are not fatigued, Miss Lucy, I do not overwalk you?"

But she seemed at the zenith of good health and spirits.

"Indeed, I was never less tired than now."

All her childhood's haunts, all the glades she had peopled with youth's brightest fairies, they visited together. In a Grecian temple on a little height they paused and looked over the rolling countryside below the park, saw the wheat-sheaves piled together in the lowlands and the church beyond, its delicate spire rising above the elms and oaks, and over all the blue cloudless sky; the shadows were long when they turned homewards, the full, generous day was nearly ended when he left her on the terrace. He lingered so long in his farewell and spoke so often and so passionately of their next meeting:

"To-morrow, Miss Lucy, soon?"—hat it might be as if he feared never to see her again.

Mrs. Bartlet was waiting for her, not anxiously or with any regret, Miss Lucy was safe with him—the honoured damsel with the chosen knight.

At length he was gone, but not the brightness he had brought with him.

"Why, Miss Lucy, there's adventure! Never have you had such a thing happen to you before, have you?"

"Oh, Mrs. Bartlet, I took him to all the places—you know, the Wishing-well—though he spoilt the wish by telling it me—the beech grove and the little temple where you can see the lowlands and the church, and all the other happy places; oh, Mrs. Bartlet, I think he loves me!"

The old nurse drew the girl to her bosom.

"And I'm sure he does, my dear."

"And he's coming again to-morrow, Mrs. Bartlet, and the day after that. And do you think anyone will be displeased? And, hush! you must not say I told you—I don't know how it came that I spoke the words, for he never said anything of it to me."

"But looks are enough, my dear; the being together and his finding you like that. And who would have thought, Miss Lucy, you being alone here would have had a visitor like that?"

"Love," thought Lucy. "Love itself—that's who my visitor was!"

"You're not shivering, Miss Lucy, you're not overtired? I've got some supper for you."

"Oh, Mrs. Bartlet, I couldn't eat anything, but I will wait up till the others come home to tell them." And she laughed. "I must tell them about Okestead Woods, must I not? And, you know I had forgotten about them until this moment—and yet that was the cause of his coming—O blessed, happy woods will they always be to me!"

The picnic party were late; the moon was high and glorious, but Lucy Middleton would not go to bed, she sat in the lamplit drawing-room, looking out on to the moonlit terrace. What had he said—how had he said it—how had he moved and glanced? She could neither eat nor drink and Mrs. Bartlet, listening to more confidences, found her clinging hand hot.

"Oh, Miss Lucy, you've never taken a chill! Did you go into the beech wood? It's always cool, on a sunny day."

"We went into the beech wood, Mrs. Bartlet, but I never took a chill. I am well, I never felt better—"

"Yet, my dear, you must not sit up for them any longer; they're late—who knows how later they may not be? The young people enjoying themselves and the master and mistress not wishing to interfere with their pleasures, and all thinking you abed and asleep hours ago, Miss Lucy dear."

"They don't know what's happened to me," said Lucy, "they never can guess what's happened to me."

She turned suddenly, and peered past the circle of lamplight.

"Why, surely that's someone outside! Do you think he's come back, Mrs. Bartlet, do you think he's forgotten something?"

The nurse turned; she, too, thought she had heard a footstep, like an echo of that manly step of the afternoon on the terrace without. She thought she discerned in the moonlight the shape of a figure.

"Why, there wouldn't be another visitor for you to-day, Miss Lucy, at this time of night."

No, it was all fancy, they had not seen or heard anything.

"People sitting alone, and being excited, as you might say, Miss Lucy, waiting for others to come home, between the moonlight and the lamplight on a summer evening like this, often think they see and hear things."

"And maybe they do, just happy fancies come, as it were, to life."

Her high spirits dropped from her, she seemed suddenly fatigued.

"I certainly thought there was someone there," she added, vaguely. "Queer that you should have said 'another visitor for you, Miss Lucy'—have I had two visitors to-day or one?"

"One, and one only, and that's enough, my dear. But you are tired and you are coming upstairs now with me."

"Yes, I am tired, I don't think I'll wait up any longer. I suppose I walked farther than I knew. My head's beginning to throb again, and I have got that pain in my side. Yet, I don't want to go to sleep." She struggled to shake off languor. "Shall I play the harp a little, Mrs. Bartlet, or sing 'Angels ever bright and fair'?"

"You'll do nothing, Miss Lucy, but come up to bed. If you've over-fatigued yourself, Miss Lucy, I shall never, never forgive myself for letting you go."

The girl went upstairs slowly, the kind old nurse behind her, and into her little bedroom, the white, precise room, with the oval pictures and the dimity bed, which the moonlight filled with silver.

She stood musing, swinging her bonnet by its strings.

"Oh, this is a lovely night, Mrs. Bartlet, don't let's have the candles yet!" Then, "Oh, I am so happy. He's coming to-morrow, you know!"

She sat down by the bed.

"I shall be asleep when they come back, but don't tell them about Okestead Woods—I want to do that myself."

"No, Miss Lucy, I won't tell them. That's a piece of news for you to give them, and you've got something else, too, haven't you?"

The girl continued to swing her bonnet to and fro.

"I am so happy," she repeated. Then, suddenly: "Oh, I am going—there were two visitors, I thought someone came for me!"

"What do you mean, Miss Lucy?" cried the nurse, in swift and deadly panic.

But Lucy had fallen lightly across the bed, her beautiful hair encircling the pale face; she murmured again—"I'm going...someone has come to take me...I can't stay."

As Mrs. Bartlet lifted her she had ceased to sigh or smile.

Along the moonlit drive came the gay sounds of the picnic party returning.

MARTHA PYM said that she had never seen a ghost and that she would very much like to do so, "particularly at Christmas, for you can laugh as you like, that is the correct time to see a ghost."

"I don't suppose you ever will," replied her cousin Mabel comfortably, while her cousin Clara shuddered and said that she hoped they would change the subject for she disliked even to think of such things.

The three elderly, cheerful women sat round a big fire, cosy and content after a day of pleasant activities; Martha was the guest of the other two, who owned the handsome, convenient country house; she always came to spend her Christmas with the Wyntons and found the leisurely country life delightful after the bustling round of London, for Martha managed an antique shop of the better sort and worked extremely hard. She was, however, still full of zest for work or pleasure, though sixty years old, and looked backwards and forwards to a succession of delightful days.

The other two, Mabel and Clara, led quieter but none the less agreeable lives; they had more money and fewer interests, but nevertheless enjoyed themselves very well.

"Talking of ghosts," said Mabel, "I wonder how that old woman at 'Hartleys' is getting on, for 'Hartleys,' you know, is supposed to be haunted."

"Yes, I know," smiled Miss Pym, "but all the years that we have known of the place we have never heard anything definite, have we?"

"No," put in Clara; "but there is that persistent rumour that the House is uncanny, and for myself, nothing would induce me to live there!"

"It is certainly very lonely and dreary down there on the marshes," conceded Mabel. "But as for the ghost—you never hear what it is supposed to be even."

"Who has taken it?" asked Miss Pym, remembering "Hartleys" as very desolate indeed, and long shut up.

"A Miss Lefain, an eccentric old creature—I think you met her here once, two years ago——"

"I believe that I did, but I don't recall her at all."

"We have not seen her since, 'Hartleys' is so un-get-at-able and she didn't seem to want visitors. She collects china, Martha, so really you ought to go and see her and talk 'shop.'"

With the word "china" some curious associations came into the mind of Martha Pym; she was silent while she strove to put them together, and after a second or two they all fitted together into a very clear picture.

She remembered that thirty years ago—yes, it must be thirty years ago, when, as a young woman, she had put all her capital into the antique business, and had been staying with her cousins (her aunt had then been alive) that she had driven across the marsh to "Hartleys," where there was an auction sale; all the details of this she had completely forgotten, but she could recall quite clearly purchasing a set of gorgeous china which was still one of her proud delights, a perfect set of Crown Derby save that one plate was missing.

"How odd," she remarked, "that this Miss Lefain should collect china too, for it was at 'Hartleys' that I purchased my dear old Derby service—I've never been able to match that plate——"

"A plate was missing? I seem to remember," said Clara. "Didn't they say that it must be in the house somewhere and that it should be looked for?"

"I believe they did, but of course I never heard any more and that missing plate has annoyed me ever since. Who had 'Hartleys'?"

"An old connoisseur, Sir James Sewell; I believe he was some relation to this Miss Lefain, but I don't know——"

"I wonder if she has found the plate," mused Miss Pym. "I expect she has turned out and ransacked the whole place——"

"Why not trot over and ask?" suggested Mabel. "It's not much use to her, if she has found it, one odd plate."

"Don't be silly," said Clara. "Fancy going over the marshes, this weather, to ask about a plate missed all those years ago. I'm sure Martha wouldn't think of it——"

But Martha did think of it; she was rather fascinated by the idea; how queer and pleasant it would be if, after all these years, nearly a lifetime, she should find the Crown Derby plate, the loss of which had always irked her! And this hope did not seem so altogether fantastical, it was quite likely that old Miss Lefain, poking about in the ancient house, had found the missing piece.

And, of course, if she had, being a fellow-collector, she would be quite willing to part with it to complete the set.

Her cousin endeavoured to dissuade her; Miss Lefain, she declared, was a recluse, an odd creature who might greatly resent such a visit and such a request.

"Well, if she does I can but come away again," smiled Miss Pym. "I suppose she can't bite my head off, and I rather like meeting these curious types—we've got a love for old china in common, anyhow."

"It seems so silly to think of it—after all these years—a plate!"

"A Crown Derby plate," corrected Miss Pym. "It is certainly strange that I didn't think of it before, but now that I have got it into my head I can't get it out. Besides," she added hopefully, "I might see the ghost."

So full, however, were the days with pleasant local engagements that Miss Pym had no immediate chance of putting her scheme into practice; but she did not relinquish it, and she asked several different people what they knew about "Hartleys" and Miss Lefain.

And no one knew anything save that the house was supposed to be haunted and the owner "cracky."

"Is there a story?" asked Miss Pym, who associated ghosts with neat tales into which they fitted as exactly as nuts into shells.

But she was always told: "Oh, no, there isn't a story, no one knows anything about the place, don't know how the idea got about; old Sewcll was half-crazy, I believe, he was buried in the garden and that gives a house a nasty name——"

"Very unpleasant," said Martha Pym, undisturbed.

This ghost seemed too elusive for her to track down; she would have to be content if she could recover the Crown Derby plate; for that at least she was determined to make a try and also to satisfy that faint tingling of curiosity roused in her by this talk about "Hartleys" and the remembrance of that day, so long ago, when she had gone to the auction sale at the lonely old house.

So the first free afternoon, while Mabel and Clara were comfortably taking their afternoon repose, Martha Pym, who was of a more lively habit, got out her little governess cart and dashed away across the Essex flats.

She had taken minute directions with her, but she had soon lost her way.

Under the wintry sky, which looked as grey and hard as metal, the marshes stretched bleakly to the horizon, the olive-brown broken reeds were harsh as scars on the saffron-tinted bogs, where the sluggish waters that rose so high in winter were filmed over with the first stillness of a frost; the air was cold but not keen, everything was damp; faintest of mists blurred the black outlines of trees that rose stark from the ridges above the stagnant dykes; the flooded fields were haunted by black birds and white birds, gulls and crows, whining above the long ditch grass and wintry wastes.

Miss Pym stopped the little horse and surveyed this spectral scene, which had a certain relish about it to one sure to return to a homely village, a cheerful house and good company.

A withered and bleached old man, in colour like the dun landscape, came along the road between the sparse alders.

Miss Pym, buttoning up her coat, asked the way to "Hartley" as he passed her; he told her, straight on, and she proceeded, straight indeed across the road that went with undeviating length across the marshes.

"Of course," thought Miss Pym, "if you live in a place like this, you are bound to invent ghosts."

The house sprang up suddenly on a knoll ringed with rotting trees, encompassed by an old brick wall that the perpetual damp had overrun with lichen, blue, green, white colours of decay.