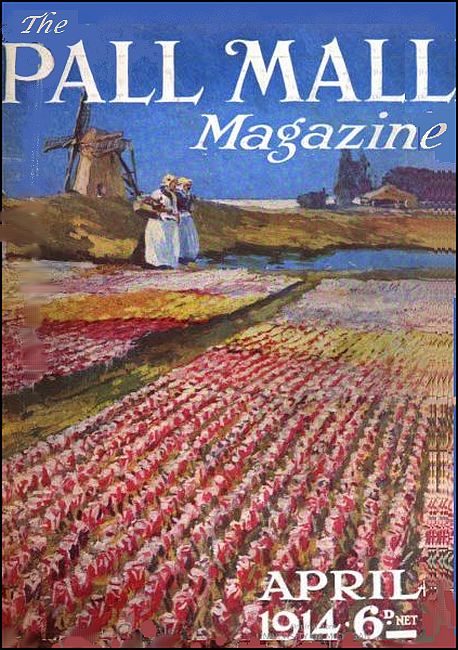

RGL e-Book Cover©

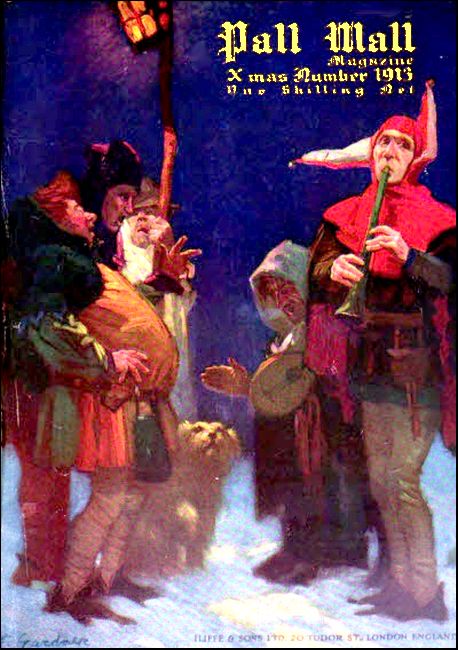

Based on a painting by John O'Connor (1830-1889)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by John O'Connor (1830-1889)

"Crimes of Old London,"

Title Page, Odhams, London, 1919

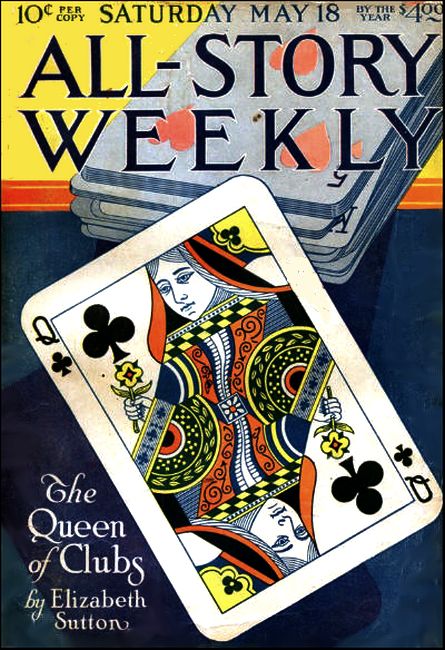

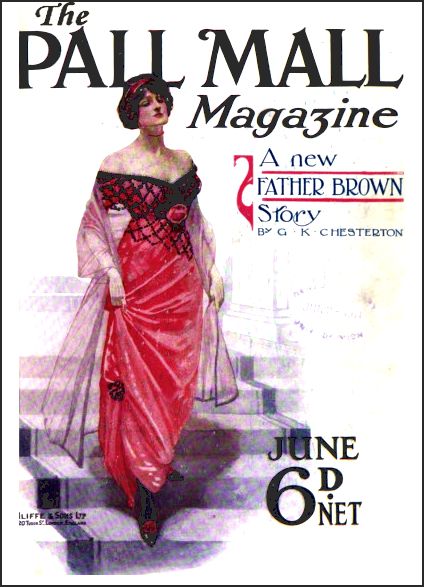

All Story Weekly, 8 June 1918, with "The Scoured Silk"

THIS is a tale that might be told in many ways and from various points of view; it has to be gathered from here and there—a letter, a report, a diary, a casual reference; in its day the thing was more than a passing wonder, and it left a mark of abiding horror on the neighborhood.

The house in which Mr. Orford lived has finally been destroyed, the mural tablet in St. Paul's, Covent Garden, may be sought for in vain by the curious, but little remains of the old piazza where the quiet scholar passed on his daily walks, the very records of what was once so real have become blurred, almost incoherent in their pleadings with things forgotten; but this thing happened to real people, in a real London, not so long ago that the generation had not spoken with those who remembered some of the actors in this terrible drama.

It is round the person of Humphrey Orford that this tale turns, as, at the time, all the mystery and horror centered; yet until his personality was brought thus tragically into fame, he had not been an object of much interest to many; he had, perhaps, a mild reputation for eccentricity, but this was founded merely on the fact that he refused to partake of the amusements of his neighbors, and showed a dislike for much company.

But this was excused on the ground of his scholarly predilections; he was known to be translating, in a leisurely fashion, as became a gentleman, Ariosto's great romance into English couplets, and to be writing essays on recondite subjects connected with grammar and language, which were not the less esteemed because they had never been published.

His most authentic portrait, taken in 1733 and intended for a frontispiece for the Ariosto when this should come to print, shows a slender man with reddish hair, rather severely clubbed, a brown coat, and a muslin cravat; he looks straight out of the picture, and the face is long, finely shaped, and refined, with eyebrows rather heavier than one would expect from such delicacy of feature.

When this picture was painted Mr. Orford was living near Covent Garden, close to the mansion once occupied by the famous Dr. Radcliffe, a straight-fronted, dark house of obvious gentility, with a little architrave portico over the door and a few steps leading up to it; a house with neat windows and a gloomy air, like every other residence in that street and most other streets of the same status in London.

And if there was nothing remarkable about Mr. Orford's dwelling place or person there was nothing, as far as his neighbors knew, remarkable about his history.

He came from a good Suffolk family, in which county he was believed to have considerable estates (though it was a known fact that he never visited them), and he had no relations, being the only child of an only child, and his parents dead; his father had purchased this town house in the reign of King William, when the neighborhood was very fashionable, and up to it he had come, twenty years ago—nor had he left it since.

He had brought with him an ailing wife, a house-keeper, and a man-servant, and to the few families of his acquaintance near, who waited on him, he explained that he wished to give young Mrs. Orford, who was of a mopish disposition, the diversion of a few months in town.

But soon there was no longer this motive for remaining in London, for the wife, hardly seen by anyone, fell into a short illness and died—just a few weeks after her husband had brought her up from Suffolk. She was buried very simply in St. Paul's, and the mural tablet set up with a draped urn in marble, and just her name and the date, ran thus:

Flora, Wife of Humphrey Orford, Esq.,

of this Parish,

Died November, 1713, Aged 27 Years.

Mr. Orford made no effort to leave the house; he remained, people thought, rather stunned by his loss, kept himself close in the house, and for a considerable time wore deep mourning.

But this was twenty years ago, and all had forgotten the shadowy figure of the young wife, whom so few had seen and whom no one had known anything about or been interested in, and all trace of her seemed to have passed out of the quiet, regular, and easy life of Mr. Orford, when an event that gave rise to some gossip caused the one-time existence of Flora Orford to be recalled and discussed among the curious. This event was none other than the sudden betrothal of Mr. Orford and the announcement of his almost immediate marriage.

The bride was one who had been a prattling child when the groom had first come to London: one old lady who was forever at her window watching the little humors of the street recollected and related how she had seen Flora Orford, alighting from the coach that had brought her from the country, turn to this child, who was gazing from the railing of the neighboring house, and touch her bare curls lovingly and yet with a sad gesture.

And that was about the only time anyone ever did see Flora Orford, she so soon became ailing; and the next the inquisitive old lady saw of her was the slender brown coffin being carried through the dusk towards St. Paul's Church.

But that was twenty years ago, and here was the baby grown up into Miss Elisa Minden, a very personable young woman, soon to be the second Mrs. Humphrey Orford. Of course there was nothing very remarkable about the match; Elisa's father, Dr. Minden, had been Mr. Orford's best friend (as far as he could be said to have a best friend, or indeed any friend at all) for many a long year, both belonged to the same quiet set, both knew all about each other. Mr. Orford was not much above forty-five or so, an elegant, well-looking man, wealthy, with no vices and a calm, equable temper; while Miss Elisa, though pretty and well-mannered, had an insufficient dowry, no mother to fend for her, and the younger sisters to share her slender advantages. So what could anyone say save that the good doctor had done very well for his daughter, and that Mr. Orford had been fortunate enough to secure such a fresh, capable maiden for his wife?

It was said that the scholar intended giving up his bookish ways—that he even spoke of going abroad a while, to Italy, for preference; he was of course, anxious to see Italy, as all his life had been devoted to preparing the translation of an Italian classic.

The quiet betrothal was nearing its decorous conclusion when one day Mr. Orford took Miss Minden for a walk and brought her home round the piazza of Covent Garden, then took her across the cobbled street, past the stalls banked up with the first spring flowers (it was the end of March), under the portico built by the great Inigo Jones, and so into the church.

"I want to show you where my wife Flora lies buried," said Mr. Orford.

And that is really the beginning of the story.

Now, Miss Minden had been in this church every Sunday of her life and many weekdays, and had been used since a child to see that tablet to Flora Orford; but when she heard these words in the quiet voice of her lover and felt him draw her out of the sunlight into the darkness of the church, she experienced a great distaste that was almost fear.

It seemed to her both a curious and a disagreeable thing for him to do, and she slipped her arm out of his as she replied.

"Oh, please let us go home!" she said. "Father will be waiting for us, and your good Mrs. Boyd vexed if the tea is over-brewed."

"But first I must show this," he insisted, and took her arm again and led her down the church, past his seat, until they stood between his pew end and the marble tablet in the wall which was just a hand's space above their heads.

"That is to her memory," said Mr. Orford. "And you see there is nothing said as to her virtues."

Now, Elisa Minden knew absolutely nothing of her predecessor, and could not tell if these words were spoken in reverence or irony, so she said nothing but looked up rather timidly from under the shade of her Leghorn straw at the tall figure of her lover, who was staring sternly at the square of marble.

"And what have you to say to Flora Orford?" he asked sharply, looking down at her quickly.

"Why, sir, she was a stranger to me," replied Miss Minden. Mr. Orford pressed her arm.

"But to me she was a wife," he said. "She is buried under your feet. Quite close to where you are standing. Why, think of that, Lizzie, if she could stand up and put out her hand she could catch hold of your dress—she is as near as that!"

The words and his manner of saying them filled Miss Minden with shuddering terror, for she was a sensitive and fanciful girl, and it seemed to her a dreadful thing to be thus standing over the bones of the poor creature who had loved the man who was now to be her husband, and horrible to think that the handful of decay so near them had once clung to this man and loved him.

"Do not tremble, my dear girl," said Mr. Orford. "She is dead."

Tears were in Elisa Minden's eyes, and she answered coldly:

"Sir, how can you speak so?"

"She was a wicked woman," he replied, "a very wicked woman."

The girl could not reply as to that; this sudden disclosing of a painful secret abashed her simple mind.

"Need we talk of this?" she asked; then, under her breath—"Need we be married in this church, sir?"

"Of course," he answered shortly, "everything is arranged. Tomorrow week."

Miss Minden did not respond; hitherto she had been fond of the church, now it seemed spoilt for her—tarnished by the thought of Flora Orford.

Her companion seemed to divine what reflection lay behind her silence.

"You need not be afraid," he said rather harshly. "She is dead. Dead."

And he reached out the light cane he wore and tapped on the stone above his wife's grave, and slowly smiled as the sound rang hollow in the vaults beneath.

Then he allowed Elisa to draw him away, and they returned to Mr. Orford's comfortable house, where in the upper parlor Dr. Minden was awaiting them together with his sister and her son, a soldier cousin whom the quick perceptions of youthful friends had believed to be devoted to Elisa Minden. They made a pleasant little party with the red curtains drawn, and the fire burning up between the polished andirons and all the service for tea laid out with scones and Naples cake, and Mrs. Boyd coming to and fro with plates and dishes. And everyone was cheerful and friendly and glad to be indoors together, with a snowstorm coming up and people hurrying home with heads bent before a cutting wind.

But to Elisa's mind had come an unbidden thought:

"I do not like this house—it is where Flora Orford died."

And she wondered in which room, and also why this had never occurred to her before, and glanced rather thoughtfully at the fresh young face of the soldier cousin as he stood by the fire in his scarlet and white, with his glance on the flames.

But it was a cheerful party, and Elisa smiled and jested with the rest as she reserved the dishes at tea.

There is a miniature of her painted about this time, and one may see how she looked with her bright brown hair and bright brown eyes, rosy complexion, pretty nose and mouth, and her best gown of lavender blue tabinet with a lawn tucker and a lawn cap fastened under the chin with frilled lappets, showing now the big Leghorn hat with the velvet strings was put aside.

Mr. Orford also looked well tonight; he did not look his full age in the ruddy candle glow, the grey did not show in his abundant hair nor the lines in his fine face, but the elegance of his figure, the grace of his bearing, the richness of his simple clothes, were displayed to full advantage; Captain Hoare looked stiff and almost clumsy by contrast.

But now and then Elisa Minden's eyes would rest rather wistfully on the fresh face of this young man who had no dead wife in his life. And something was roused in her meek youth and passive innocence, and she wondered why she had so quietly accepted her father's arrangement of a marriage with this elderly scholar, and why Philip Hoare had let her do it. Her thoughts were quite vague and amounted to no more than a confused sense that something was wrong, but she lost her satisfaction in the tea-drinking and the pleasant company, and the warm room with the drawn curtains, and the bright fire, and rose up saying they must be returning, as there was a great store of mending she had promised to help her aunt with; but Mrs. Hoare would not help her out, but protested, laughing, that there was time enough for that, and the good doctor, who was in a fine humor and in no mood to go out into the bleak streets even as far as his own door, declared that now was the time they must be shown over the house.

"Do you know, Humphrey," he said, "you have often promised us this, but never done it, and, all the years that I have known you, I have never seen but this room and the dining-room below; and as to your own particular cabinet—"

"Well," said Mr. Orford, interrupting in a leisurely fashion, "no one has been in there, save Mrs. Boyd now and then, to announce a visitor."

"Oh, you scholars!" smiled the doctor. "A secretive tribe—and a fortunate one; why, in my poor room I have had three girls running to and fro!"

The soldier spoke, not so pleasantly as his uncle.

"What have you so mysterious, sir, in this same cabinet, that it must be so jealously guarded?" he asked.

"Why, nothing mysterious," smiled the scholar; "only my books, and papers, and pictures."

"You will show them to me?" asked Elisa Minden, and her lover gave graceful consent; there was further amiable talk, and then the whole party, guided by Mr. Orford holding a candle, made a tour of the house and looked over the fine rooms.

Mrs. Hoare took occasion to whisper to the bride-to-be that there were many alterations needed before the place was ready for a lady's use, and that it was time these were put in hand—why, the wedding was less than a fortnight off!

And Elisa Minden, who had not had a mother to advise her in these matters, suddenly felt that the house was dreary and old-fashioned, and an impossible place to live in; the very rooms that had so pleased her good father—a set of apartments for a lady—were to her the most hateful in the house, for they, her lover told her, had been furnished and prepared for Flora Orford, twenty years ago.

She was telling herself that when she was married she must at once go away and that the house must be altered before she could return to it, when the party came crowding to the threshold of the library or private cabinet, and Mr. Orford, holding the candle aloft, led them in. Then as this illumination was not sufficient, he went very quickly and lit the two candles on the mantelpiece.

It was a pleasant apartment, lined with books from floor to ceiling, old, valuable, and richly bound books, save only in the space above the chimney piece, which was occupied by a portrait of a lady and the panel behind the desk; this was situated in a strange position, in the farthest corner of the room fronting the wall, so that anyone seated there would be facing the door with the space of the room between; the desk was quite close to the wall, so that there was only just space for the chair at which the writer would sit, and to accommodate this there were no bookshelves behind it, but a smooth panel of wood on which hung a small picture; this was a rough, dark painting, and represented a man hanging on a gallows on a wild heath; it was a subject out of keeping with the luxurious room with its air of ease and learning, and while Mr. Orford was showing his first editions, his Elzevirs and Aldines, Elisa Minden was staring at this ugly little picture.

As she looked she was conscious of such a chill of horror and dismay as nearly caused her to shriek aloud. The room seemed to her to be full of an atmosphere of terror and evil beyond expression. Never had such a thing happened to her before; her visit to the tomb in the afternoon had been as nothing to this. She moved away, barely able to disguise an open panic. As she turned, she half-stumbled against a chair, caught at it, and noticed, hanging over the back, a skirt of peach-colored silk. Elisa, not being mistress of herself, caught at this garment.

"Why, sir," cried she hysterically, "what is this?"

All turned to look at her; her tone, her obvious fright, were out of proportion to her discovery.

"Why, child," said Mrs. Hoare, "it is a silk petticoat, as all can see."

"A gift for you, my dear," said the cheerful doctor.

"A gift for me?" cried Elisa. "Why, this has been scoured, and turned, and mended, and patched a hundred times!"

And she held up the skirt, which had indeed become like tinder and seemed ready to drop to pieces.

The scholar now spoke.

"It belongs to Mrs. Boyd," he said quietly. "I suppose she had been in here to clean up, and has left some of her mending."

Now, two things about this speech made a strange impression on everyone; first, it was manifestly impossible that the good housekeeper would ever have owned such a garment as this, that was a lady's dress and such as would be worn for a ball; secondly, Mr. Orford had only a short while before declared that Mrs. Boyd only entered his room when he was in it, and then of a necessity and for a few minutes.

All had the same impression, that this was some garment belonging to his dead wife and as such cherished by him; all, that is, but Elisa, who had heard him call Flora Orford a wicked woman.

She put the silk down quickly (there was a needle sticking into it and a spool of cotton lying on the chair beneath) and looked up at the portrait above the mantelpiece.

"Is that Mrs. Orford?" she asked.

He gave her a queer look.

"Yes," he said.

In a strange silence all glanced up at the picture.

It showed a young woman in a white gown, holding a crystal heart that hung round her neck; she had dark hair and a pretty face; as Elisa looked at the pointed fingers holding the pretty toy, she thought of the tablet in St. Paul's Church and Mr. Orford's words—"She is so near to you that if she could stretch out her hand she could touch you," and without any remark about the portrait or the sitter, she advised her aunt that it was time to go home. So the four of them left, and Mr. Orford saw them out, standing framed in the warm light of the corridor and watching them disappear into the grey darkness of the street.

It was a little more than an hour afterwards when Elisa Minden came creeping down the stairway of her home and accosted her cousin, who was just leaving the house.

"Oh, Philip," said she, clasping her hands, "if your errand be not a very important one, I beg you to give me an hour of your time. I have been watching for you to go out, that I might follow and speak to you privately."

The young soldier looked at her keenly as she stood in the light of the hall lamp, and he saw that she was very agitated.

"Of course, Lizzie," he answered kindly, and led her into the little parlor off the hall where there was neither candles or fire, but leisure and quiet to talk.

Elisa, being a housekeeper, found a lamp and lit it, and apologized for the cold, but she would not return upstairs, she said, for Mrs. Hoare and the two girls and the doctor were all quiet in the great parlor, and she had no mind to disturb them.

"You are in trouble," said Captain Hoare quietly.

"Yes," replied she in a frightened way, "I want you to come with me now to Mr. Orford's house—I want to speak to his housekeeper."

"Why, what is this, Lizzie?"

She had no very good explanation; there was only the visit to the church that afternoon, her impression of horror in the cabinet, the discovery of the scoured silk.

"But I must know something of his first wife, Philip," she concluded. "I could never go on with it—if I did not—something has happened today—I hate that house, I almost hate—him."

"Why did you do it, Lizzie?" demanded the young soldier sternly. "This was a nice homecoming for me...a man who might be your father...a solitary...one who frightens you."

Miss Minden stared at her cousin; she did not know why she had done it; the whole thing seemed suddenly impossible.

"Please, you must come with me now," she said.

So overwrought was she that he had no heart to refuse her, and they took their warm cloaks from the hall and went out into the dark streets.

It was snowing now and the ground slippery under foot, and Elisa clung to her cousin's arm. She did not want to see Mr. Orford or his house ever again, and by the time they reached the doorstep she was in a tremble; but she rang the bell boldly.

It was Mrs. Boyd herself who came to the door; she began explaining that the master was shut up in his cabinet, but the soldier cut her short.

"Miss Minden wishes to see you," he said, "and I will wait in the hall till she is ready."

So Elisa followed the housekeeper down to her basement sitting-room; the man-servant was out, and the two maids were quickly dismissed to the kitchen.

Mrs. Boyd, a placid soul, near seventy-years, waited for the young lady to explain herself, and Elisa Minden, flushing and paling by turns, and feeling foolish and timid, put forth the object of her coming.

She wanted to hear the story of Flora Orford—there was no one else whom she could ask—and she thought that she had a right to know.

"And I suppose you have, my dear," said Mrs. Boyd, gazing into the fire, "though it is not a pretty story for you to hear—and I never thought I should be telling it to Mr. Orford's second wife!"

"Not his wife yet." said Miss Minden.

"There, there, you had better ask the master yourself," replied Mrs. Boyd placidly; "not but that he would be fierce at your speaking of it, for I do not think a mention of it has passed his lips, and it's twenty years ago and best forgotten, my dear."

"Tell it me and then I will forget," begged Miss Minden.

So then Mrs. Boyd, who was a quiet, harmless soul with no dislike to telling a tale (though no gossip, as events had proved, she having kept her tongue still on this matter for so long), told her story of Humphrey Orford's wife; it was told in very few words.

"She was the daughter of his gamekeeper, my dear, and he married her out of hand, just for her pretty face. But they were not very happy together that I could ever see; she was afraid of him and that made her cringe, and he hated that, and she shamed him with her ignorant ways. And then one day he found her with a lover, saving your presence, mistress, one of her own people, just a common man. And he was just like a creature possessed; he shut up the house and sent away all the servants but me, and brought his lady up to town, to this house here. And what passed between her and him no one will know, but she ever looked like one dying of terror. And then the doctor began to come, Dr. Thursby, it was, that is dead now, and then she died, and no one was able to see her even she was in her coffin, nor to send a flower. 'Tis likely she died of grief, poor, fond wretch. But, of course, she was a wicked woman, and there was nothing to do but pity the master."

And this was the story of Flora Orford.

"And the man?" asked Miss Minden, after a little.

"The man she loved, my dear? Well, Mr. Orford had him arrested as a thief for breaking into his house, he was wild, that fellow, with not the best of characters—well, he would not say why he was in the house, and Mr. Orford, being a Justice of the Peace, had some power, so he was just condemned as a common thief. And there are few to this day know the truth of the tale, for he kept his counsel to the last, and no one knew from him why he had been found in the Squire's house."

"What was his end?" asked Miss Minden in a still voice.

"Well, he was hanged," said Mrs. Boyd; "being caught red-handed, what could he hope for?"

"Then that is a picture of him in the cabinet!" cried Elisa, shivering for all the great fire; then she added desperately, "Tell me, did Flora Orford die in that cabinet?"

"Oh, no, my dear, but in a great room at the back of the house that has been shut up ever since."

"But the cabinet is horrible," said Elisa; "perhaps it is her portrait and that picture."

"I have hardly been in there," admitted Mrs. Boyd, "but the master lives there—he has always had his supper there, and he talks to that portrait my dear—'Flora, Flora' he says, 'how are you tonight?' and then he imitates her voice, answering."

Elisa Minden clapped her hand to her heart.

"Do not tell me these things or I shall think that you are hateful too, to have stayed in this dreadful house and endured them!" Mrs. Boyd was surprised.

"Now, my dear, do not be put out," she protested.

"They were wicked people both of them and got their deserts, and it is an old story best forgotten; and as for the master, he has been just a good creature ever since we have been here, and he will not go talking to any picture when he has a sweet young wife to keep him company."

But Elisa Minden had risen and had her fingers on the handle of the door.

"One thing more," said she breathlessly; "that scoured silk—of a peach color—"

"Why, has he got that still? Mrs. Orford wore it the night he found her with her sweetheart. I mind I was with her when she bought it—fine silk at forty shillings the yard. If I were you, my dear, I should burn that when I was mistress here."

But Miss Minden had run upstairs to the cold hall.

Her cousin was not there; she heard angry voices overhead and saw the two maid-servants affrighted on the stairs; a disturbance was unknown in this household.

While Elisa stood bewildered, a door banged, and Captain Hoare came down red in the face and fuming; he caught his cousin's arm and hurried her out of the house.

In an angry voice he told her of the unwarrantable behavior of Mr. Orford, who had found him in the hall and called him "intruder" and "spy" without waiting for an explanation; the soldier had followed the scholar up to his cabinet and there had been an angry scene about nothing at all, as Captain Hoare said.

"Oh, Philip," broke out poor Elisa as they hastened through the cold darkness, "I can never, never marry him!"

And she told him the story of Flora Orford. The young man pressed her arm through the heavy cloak.

"And how came such a one to entangle thee?" he asked tenderly. "Nay, thou shalt not marry him."

They spoke no more, but Elisa, happy in the protecting and wholesome presence of her kinsman, sobbed with a sense of relief and gratitude. When they reached home they found they had been missed and there had to be explanations; Elisa said there was something that she had wished to say to Mrs. Boyd, and Philip told of Mr. Orford's rudeness and the quarrel that had followed.

The two elder people were disturbed and considered Elisa's behavior strange, but her manifest agitation caused them to forbear pressing her for an explanation; nor was it any use addressing themselves to Philip, for he went out to his delayed meeting with companions at a coffee-house.

That night Elisa Minden went to bed feeling more emotion than she had ever done in her life; fear and disgust of the man whom hitherto she had placidly regarded as her future husband, and a yearning for the kindly presence of her childhood's companion united in the resolute words she whispered into her pillow during that bitter night.

"I can never marry him now!"

The next day it snowed heavily, yet a strange elation was in Elisa's heart as she descended to the warm parlor, bright from the fire and light from the glow of the snow without.

She was going to tell her father that she could not carry out her engagement with Mr. Orford, and that she did not want ever to go into his house again.

They were all gathered round the breakfast-table when Captain Hoare came in late (he had been out to get a newsletter) and brought the news that was the most unlooked for they could conceive, and that was soon to startle all London.

Mr. Orford had been found murdered in his cabinet.

These tidings, though broken as carefully as possible, threw the little household into the deepest consternation and agitation; there were shrieks, and cryings, and running to and fro.

Only Miss Minden, though of a ghastly color, made no especial display of grief; she was thinking of Flora Orford.

When the doctor could get away from his agitated womenkind, he went with his nephew to the house of Mr. Orford.

The story of the murder was a mystery. The scholar had been found in his chair in front of his desk with one of his own bread-knives sticking through his shoulders; and there was nothing to throw any light as to how or through whom he had met his death.

The story, sifted from the mazed incoherency of Mrs. Boyd, the hysterics of the maids, the commentaries of the constables, and the chatter of the neighbors, ran thus:

At half-past nine the night before, Mrs. Boyd had sent one of the maids up with her master's supper; it was his whim to have it always thus, served on a tray in the cabinet. There had been wine and meat, bread and cheese, fruit and cakes—the usual plates and silver—among these the knife that had killed Mr. Orford.

When the servant left, the scholar had followed her to the door and locked it after her; this was also a common practice of his, a precaution against any possible interruption, for, he said, he did the best part of his work in the evening.

It was found next morning that his bed had not been slept in, and that the library door was still locked; as the alarmed Mrs. Boyd could get no answer to her knocks, the man-servant had sent for someone to force the lock, and Humphrey Orford had been found in his chair, leaning forward over his papers with the knife thrust up to the hilt between his shoulders; he must have died instantly, for there was no sign of any struggle, nor any disarrangement of his person or his papers. The first doctor to see him, a passer-by, attracted by the commotion about the house, said he must have been dead some hours—probably since the night before; the candles had all burnt down to the socket, and there were spillings of grease on the desk; the supper tray stood at the other end of the room, most of the food had been eaten, most of the wine drunk, the articles were all there in order excepting only the knife sticking between Mr. Orford's shoulder-blades.

When Captain Hoare had passed the house on his return from buying the newsletter he had seen the crowd and gone in and been able to say that he had been the last person to see the murdered man alive, as he had had his sharp encounter with Mr. Orford about ten o'clock, and he remembered seeing the supper things in the room. The scholar had heard him below, unlocked the door, and called out such impatient resentment of his presence that Philip had come angrily up the stairs and followed him into the cabinet; a few angry words had passed, when Mr. Orford had practically pushed his visitor out, locking the door in his face and bidding him take Miss Minden home.

This threw no light at all on the murder; it only went to prove that at ten o'clock Mr. Orford had been alive in his cabinet.

Now here was the mystery; in the morning the door was still locked, on the inside, the window was, as it had been since early evening, shuttered and fastened across with an iron bar, on the inside, and, the room being on an upper floor, access would have been in any case almost impossible by the window which gave on to the smooth brickwork of the front of the house.

Neither was there any possible place in the room where anyone might be hidden—it was just the square lined with the shallow bookshelves, the two pictures (that sombre little one looking strange now above the bent back of the dead man), the desk, one or two chairs and side tables; there was not so much as a cupboard or bureau—not a hiding-place for a cat.

How, then, had the murderer entered and left the room?

Suicide, of course, was out of the question, owing to the nature of the wound—but murder seemed equally out of the question; Mr. Orford sat so close to the wall that the handle of the knife touched the panel behind him. For anyone to have stood between him and the wall would have been impossible; behind the back of his chair was not space enough to push a walking-stick.

How, then, had the blow been delivered with such deadly precision and force?

Not by anyone standing in front of Mr. Orford, first because he must have seen him and sprung up; and secondly, because, even had he been asleep with his head down, no one, not even a very tall man, could have leaned over the top of the desk and driven in the knife, for experiment was made, and it was found that no arm could possibly reach such a distance.

The only theory that remained was that Mr. Orford had been murdered in some other part of the room and afterwards dragged to his present position.

But this seemed more than unlikely, as it would have meant moving the desk, a heavy piece of furniture that did not look as if it had been touched, and also became there was a paper under the dead man's hand, a pen in his fingers, a splutter of ink where it had fallen, and a sentence unfinished. The thing remained a complete and horrid mystery, one that seized the imagination of men; the thing was the talk of all the coffee-houses and clubs.

The murder seemed absolutely motiveless, the dead man was not known to have an enemy in the world, yet robbery was out of the question, for nothing had been even touched.

The early tragedy was opened out. Mrs. Boyd told all she knew, which was just what she had told Elisa Minden—the affair was twenty years ago, and the gallows bird had no kith or kin left.

Elisa Minden fell into a desperate state of agitation, a swift change from her first stricken calm; she wanted Mr. Orford's house pulled down—the library and all its contents burnt; her own wedding-dress did she burn, in frenzied silence, and none dare stop her; she resisted her father's entreaties that she should go away directly after the inquest; she would stay on the spot, she said, until the mystery was solved.

Nothing would content her but a visit to Mr. Orford's cabinet; she was resolved, she said wildly, to come to the bottom of this mystery and in that room, which she had entered once and which had affected her so terribly, she believed she might find some clue.

The doctor thought it best to allow her to go; he and her cousin escorted her to the house that now no one passed without a shudder and into the chamber that all dreaded to enter.

Good Mrs. Boyd was sobbing behind them; the poor soul was quite mated with this sudden and ghastly ending to her orderly life; she spoke all incoherently, explaining, excusing, and lamenting in a breath; yet through all her trouble she showed plainly and artlessly that she had had no affection for her master, and that it was custom and habit that had been wounded, not love.

Indeed, it seemed that there was no one who did love Humphrey Orford; the lawyers were already busy looking for a next-of-kin; it seemed likely that this property and the estates in Suffolk would go into Chancery.

"You should not go in, my dear, you should not go in," sobbed the old woman, catching at Miss Minden's black gown (she was in mourning for the murdered man) and yet peering with a fearful curiosity into the cabinet.

Elisa looked ill and distraught but also resolute.

"Tell me, Mrs. Boyd," said she, pausing on the threshold, "what became of the scoured silk?"

The startled housekeeper protested that she had never seen it again; and here was another touch of mystery—the old peach-colored silk skirt that four persons had observed in Mr. Orford's cabinet the night of his murder, had completely disappeared.

"He must have burnt it," said Captain Hoare, and though it seemed unlikely that he could have consumed so many yards of stuff without leaving traces in the grate, still it was the only possible solution.

"I cannot think why he kept it so long," murmured Mrs. Boyd, "for it could have been no other than Mrs. Orford's best gown."

"A ghastly relic," remarked the young soldier grimly.

Elisa Minden went into the middle of the room and stared about her; nothing in the place was changed, nothing disordered; the desk had been moved round to allow of the scholar being carried away, his chair stood back, so that the long panel on which hung the picture of the gallows, was fuller exposed to view.

To Elisa's agitated imagination this portion of the wall sunk in the surrounding bookshelves, long and narrow, looked like the lid of a coffin.

"It is time that picture came down," she said; "it cannot interest anyone any longer."

"Lizzie, dear," suggested her father gently, "had you not better come away?—this is a sad and awful place."

"No," replied she. "I must find out about it—we must know."

And she turned about and stared at the portrait of Flora Orford.

"He hated her, Mrs. Boyd, did he not? And she must have died of fear—think of that!—died of fear, thinking all the while of that poor body on the gallows. He was a wicked man and whoever killed him must have done it to revenge Flora Orford."

"My dear," said the doctor hastily, "all that was twenty years ago, and the man was quite justified in what he did, though I cannot say I should have been so pleased with the match if I had known this story."

"How did we ever like him?" muttered Elisa Minden. "If I had entered this room before I should never have been promised to him—there is something terrible in it."

"And what else can you look for, my dear," snivelled Mrs. Boyd, "in a room where a man has been murdered."

"But it was like this before," replied Miss Minden; "it frightened me."

She looked round at her father and cousin, and her face quite distorted.

"There is something here now," she said, "something in this room."

They hastened towards her, thinking that her over-strained nerves had given way; but she took a step forward.

Shriek after shriek left her lips.

With a quivering finger she pointed before her at the long panel behind the desk.

At first they could not tell at what she pointed; then Captain Hoare saw the cause of her desperate terror.

It was a small portion of faded, peach-colored silk showing above the ribbed line of the wainscot, protruding from the wall, like a garment of stuff shut in a door.

"She is in there!" cried Miss Minden. "In there!"

A certain frenzy fell on all of them; they were in a confusion, hardly knowing what they said or did. Only Captain Hoare kept some presence of mind and, going up to the panel, discerned a fine crack all round.

"I believe it is a door," he said, "and that explains how the murderer must have struck—from the wall."

He lifted the picture of the hanged man and found a small knob or button, which, as he expected, on being pressed sent the panel back into the wall, disclosing a secret chamber no larger than a cupboard.

And directly inside this hidden room that was dark to the sight and noisome to the nostrils, was the body of a woman, leaning against the inner wall with a white kerchief knotted tightly round her throat, showing how she had died; she wore the scoured silk skirt, the end of which had been shut in the panel, and an old ragged bodice of linen that was like a dirty parchment; her hair was grey and scanty, her face past any likeness to humanity, her body thin and dry.

The room, which was lit only by a window a few inches square looking onto the garden, was furnished with a filthy bed of rags and a stool with a few tattered clothes; a basket of broken bits was on the floor.

Elisa Minden crept closer.

"It is Flora Orford," she said, speaking like one in a dream.

They brought the poor body down into the room, and then it was clear that this faded and terrible creature had a likeness to the pictured girl who smiled from the canvas over the mantelpiece.

And another thing was clear and, for a moment, they did not dare speak to each other.

For twenty years this woman had endured her punishment in the wall chamber in that library that no one but her husband entered; for twenty years he had kept her there, behind the picture of her lover, feeding her on scraps, letting her out only when the household was abed, amusing himself with her torture—she mending the scoured silk she had worn for twenty years, sitting there, cramped in the almost complete dark, a few feet from where he wrote his elegant poetry.

"Of course she was crazy," said Captain Hoare at length, "but why did she never cry out?"

"For a good reason," whispered Dr. Minden, when he had signed to Mrs. Boyd to take his fainting daughter away. "He saw to that—she has got no tongue."

The coffin bearing the nameplate "Flora Orford" was exhumed, and found to contain only lead; it was substituted by another containing the wasted body of a woman who died by her own hand twenty years after the date on the mural tablet to her memory.

Why or how this creature, certainly become idiotic and dominated entirely by the man who kept her prisoner, had suddenly found the resolution and skill to slay her tyrant and afterwards take her own life (a thing she might have done any time before) was a question never solved.

It was supposed that he had formed the hideous scheme to complete his revenge by leaving her in the wall to die of starvation while he left with his new bride for abroad, and that she knew this and had forestalled him; or else that her poor, lunatic brain had been roused by the sound of a woman's voice as she handled the scoured silk which the captive was allowed to creep out and mend when the library door was locked. But over these matters and the details of her twenty years' suffering, it is but decent to be silent.

Lizzie Minden married her cousin, but not at St. Paul's, Covent Garden. Nor did they ever return to the neighborhood of Humphrey Orford's house.

MR. JOHN PROUDIE kept a chemist's shop in Soho Fields, Monmouth Square; it was a very famous shop, situated at the corner, so that there were two fine windows of leaded glass, one looking on Dean Street and one on the Square, and at the corner the door, with a wooden portico by which two steps descended into the shop.

A wooden counter, polished and old, ran round this shop, and was bare of everything save a pair of gleaming brass scales; behind, the walls were covered from floor to ceiling by shelves which held jars of Delft pottery, blue and white, and Italian majolica, red and yellow, on which were painted the names of the various drugs; in the centre the shelves were broken by a door that led into an inner room.

On a certain night in November when the shop was shut, the old housekeeper abed, and the fire burning brightly in the parlour, Mr John Proudie was busy in his little laboratory compounding some medicines, in particular a mixture of the milky juice of blue flag root and pepper which he had found very popular for indigestion.

He was beginning to feel cold, and, not being a young man (at this time, the year 1690, Mr Proudie was nearly sixty), a little tired, and to think with pleasure of his easy chair, his hot drink of mulled wine on the hearth, his Gazette with its exciting news of the war and the Commons and the plots, when a loud peal at the bell caused him to drop the strainer he was holding—not that it was so unusual for Mr Proudie's bell to ring after dark, but his thoughts had been full of these same troubles of plots and counter-plots of the late Revolution, and the house seemed very lonely and quiet.

'Fine times,' thought Mr Proudie indignantly, 'when an honest tradesman feels uneasy in his own home!'

The bell went again, impatiently, and the apothecary wiped his hands, took up a candle, and went through to the dark shop. As he passed through the parlour he glanced up at the clock and was surprised to see that it was nearly midnight. He set the candle in its great pewter stick on the counter, whence the light threw glistening reflections on the rows of jars and their riches, and opened the door. A gust of wind blew thin cold sleet across the, polished floor, and the apothecary shivered as he cried out: 'Who is there?'

Without replying a tall gentleman stepped down into the shop, closing the door behind him.

'Well, sir?' asked Mr Proudie a little sharply.

'I want a doctor,' said the stranger, 'at once.'

He glanced round the shop impatiently, taking no more notice of Mr Proudie than if he had been a servant.

'And why did you come here for a doctor?' demanded the apothecary, not liking his manner and hurt at the insinuation that his own professional services were not good enough.

'I was told,' replied the stranger, speaking in tolerable English, but with a marked foreign accent, 'that a doctor lodged over your shop.'

'So he does,' admitted Mr Proudie grudgingly; 'but he is abed.'

The stranger approached the counter and leant against it in the attitude of a man exhausted; the candlelight was now full on him, but revealed nothing of his features, for he wore a black mask such as was used for travelling on doubtful rendezvous; a black lace fringe concealed the lower part of his face.

Mr Proudie did not like this; he scented mystery and underhand intrigue, and he stared at the stranger very doubtfully.

He was a tall, graceful man, certainly young, wrapped in a dark blue mantle lined with fur and wearing riding gloves and top boots; the skirts of a blue velvet coat showed where the mantle was drawn up by. his sword, and there was a great deal of fine lace and a diamond brooch at his throat.

'Well,' he said impatiently, and his black eyes flashed through the mask holes, 'how long are you going to keep me waiting? I want Dr Valletort at once.'

'Oh, you know his name?'

'Yes, I was told his name. Now, for God's sake, sir, fetch him—tell him it is a woman who requires his services!'

Mr Proudie turned reluctantly away and picked up the candle, leaving the gentleman in the dark, mounted the stairs to the two rooms above the shop, and roused his lodger.

'You are wanted, Dr Valletort,' he said through the door; 'there is a man downstairs come to fetch you to a lady—a bitter night and he a foreign creature in a mask,' finished the old apothecary in a grumble.

Dr Francis Valletort at once opened the door; he was not in bed, but had been reading by the light of a small lamp. Tall and elegant, with the pallor of a scholar and the grace of a gentleman, the young doctor stood as if startled, holding his open book in his hand.

'Do not go,' said Mr Proudie on a sudden impulse; 'these are troubled times and it is a bitter night to be abroad.'

The doctor smiled.

'I cannot afford to decline patients, Mr Proudie—remember how much I am in your debt for food and lodging,' he added with some bitterness.

'Tut, tut!' replied Mr Proudie, who had a real affection for the young man. 'But no doubt I am an old fool—come down and see this fellow.'

The doctor took up his shabby hat and cloak and followed the apothecary down into the parlour and from there into the shop.

'I hope you are ready,' said the voice of the stranger from the dark; 'the patient may be dead through this delay.'

Mr Proudie again placed the candle on the counter; the red flame of it illuminated the tall, dark figure of the stranger and the shabby figure of the doctor against the background of the dark shop and the jars—labelled 'Gum Camphor', 'Mandrake Root', 'Dogwood Bark', 'Blue Vervain', 'Tansy', 'Hemlock', and many other drugs, written in blue and red lettering under the glazing.

'Where am I to go and what is the case?' asked Francis Valletort, eyeing the stranger intently.

'Sir, I will tell you all these questions on the way; the matter is urgent.'

'What must I take with me?'

The stranger hesitated.

'First, Dr Valletort,' he said, 'are you skilled in the Italian?'

The young doctor looked at the stranger very steadily. 'I studied medicine at the University of Padua,' he replied.

'Ah! Well, then, you will be able to talk to the patient, an Italian lady who speaks no English. Bring your instruments and some antidotes for poisoning, and make haste.'

The doctor caught the apothecary by the arm and drew him into the parlour. He appeared in considerable agitation.

'Get me my sword and pistols,' he said swiftly, 'while I prepare my case.'

He spoke in a whisper, for the door was open behind them into the shop, and the apothecary, alarmed by his pale look, answered in the same fashion: 'Why are you going? Do you know this man?'

'I cannot tell if I know him or not—what shall I do? God help me!'

He spoke in such a tone of despair and looked so white and ill that Mr Proudie pushed him into a chair by the fire and bade him drink some of the wine that was warming.

'You will not go out tonight,' he said firmly.

'No,' replied the doctor, wiping the damp from his brow, 'I cannot go.'

John Proudie returned to the shop to take this message to the stranger, who, on hearing it, broke into a passionate ejaculation in a foreign language, then thrust his hand into his coat pocket.

'Take this to Francis Valletort,' he answered, 'and then see if he will come.'

He flung on the counter, between the scales and candle, a ring of white enamel, curiously set with alternate pearls and diamonds very close together, and having suspended from it a fine chain from which hung a large and pure pearl.

Before the apothecary could reply Francis Valletort, who had heard the stranger's words, came from the parlour and snatched at the ring. While he was holding it under the candle flame and gazing at the whiteness of diamond, pearl, and enamel, the masked man repeated his words.

'Now will you come?'

The doctor straightened his thin shoulders, his hollow face was flushed into a strange beauty.

'I will come,' he said; he pushed back the brown locks that had slipped from the black ribbon on to his cheek and turned to pick up his hat and cloak, while he asked Mr Proudie to go up to his room and fetch his case of instruments.

The apothecary obeyed; there was something in the manner of Francis Valletort that told him that he was now as resolute in undertaking this errand as hitherto he had been anxious to avoid it; but he did not care for the adventure. When the stranger had thrust his hand into his pocket to find the ring that had produced such an effect on the doctor, Mr Proudie had noticed something that he considered very unpleasant. The soft doeskin glove had fallen back, caught in the folds of the heavy mantle as the hand was withdrawn, and Mr Proudie had observed a black wrist through the lace ruffles: the masked cavalier was a negro. Mr Proudie had seen few coloured men and regarded them with suspicion and aversion; and what seemed to him so strange was that what he styled a 'blackamoor' should be thus habited in fashionable vestures and speaking with an air of authority.

However, evidently Francis Valletort knew the man or at least his errand—doubtless from some days of student adventure in Italy; and the apothecary did not feel called upon to interfere. He returned with the case of instruments to find the stranger and the doctor both gone, the parlour and the shop both empty, and the candle on the counter guttering furiously in the fierce draught from the half-open door.

Mr Proudie was angry; there had been no need to slip away like that, sending him away by a trick, and still further no need to leave the door open at the mercy of any passing vagabond.

The apothecary went and peered up and down the street; all was wet darkness; a north wind flung the stinging rain in his face; a distant street lamp cast a fluttering flame but no light on the blackness.

Mr Proudie closed the door with a shudder and went back to his fire and his Gazette.

'Let him,' he said to himself, still vexed, 'go on his fool's errand.'

He knew very little of Francis Valletort, whose acquaintance he had made a year ago when the young doctor had come to him to buy drugs. The apothecary had found his customer earnest, intelligent, and learned, and a friendship had sprung up between the two men which had ended in the doctor renting the two rooms above the shop, and, under the wing of the apothecary, picking up what he could of the crumbs let fall by the fashionable physicians of this fashionable neighbourhood.

'I hope he will get his fee tonight,' thought Mr Proudie, as he stirred the fire into a blaze; then, to satisfy his curiosity as to whether this were really a medical case or only an excuse, he went to the dispensary to see if the doctor had taken any drugs. He soon discovered that two bottles, one containing an antidote against arsenic poisoning, composed of oxide of iron and flax seed, the other a mixture for use against lead poisoning, containing oak bark and green tea, were missing.

'So there was someone ill?' cried Mr Proudie aloud, and at that moment the door bell rang again.

'He is soon back,' thought the apothecary, and hastened to undo the door; 'perhaps he was really hurried away and forgot his case.' He opened the door with some curiosity, being eager to question the doctor, but it was another stranger who stumbled down the two steps into the dark shop—a woman, whose head was wrapped in a cloudy black shawl.

The wind had blown out the candle on the counter and the shop was only lit by the illumination, faint and dull, from the parlour; therefore, Mr Proudie could not see his second visitor clearly, but only sufficiently to observe that she was richly dressed and young; the door blew open, and wind and rain were over both of them; Mr Proudie had to clap his hand to his wig to keep it on his head.

'Heaven help us!' he exclaimed querulously. 'What do you want, madam?'

For answer she clasped his free hand with fingers so chill that they struck a shudder to the apothecary's heart, and broke out into a torrent of words in what was to Mr Proudie an incomprehensible language; she was obviously in the wildest distress and grief, and perceiving that the apothecary did not understand her, she flung herself on her knees, wringing her hands and uttering exclamations of despair.

The disturbed Mr Proudie closed the door and drew the lady into the parlour; she continued to speak, rapidly and with many gestures, but all he could distinguish was the name of Francis Valletort.

She was a pretty creature, fair and slight, with braids of seed pearls in her blonde hair showing through the dark net of her lace shawl, an apple-green silk gown embroidered with multitudes of tiny roses, and over all a black Venetian velvet mantle; long corals were in her ears, and a chain of amber round her throat; her piteously gesticulating hands were weighted with large and strange rings.

'If you cannot speak English, madam,' said Mr Proudie, who was sorry for her distress, but disliked her for her outlandish appearance and because he associated her with the blackamoor, 'I am afraid I cannot help you.'

While he spoke she searched his face with eager haggard brown eyes, and when he finished she sadly shook her head to show that she did not understand. She glanced round the homely room impatiently, then, with a little cry of despair and almost stumbling in her long silken skirts, which she was too absorbed in her secret passion to gather up, she turned back into the shop, making a gesture that Mr Proudie took to mean she wished to leave. The apothecary was not ill-pleased at this; since they could not understand each other her presence was but an embarrassment. He would have liked to have asked her to wait the doctor's return, but saw that she understood no word of English; he thought it was Italian she spoke, but he could not be even sure of that.

As swiftly as she had come she had gone, unbolting the door herself and disappearing into the dark; as far as Mr Proudie could see, she had neither chair nor coach; in which case she must have come from nearby, for there was but little wet on her clothes.

Once more the apothecary returned to his fire, noticing the faint perfume of iris the lady had left on the air to mingle with the odours of Peruvian bark and camomile, rosemary and saffron, beeswax and turpentine, myrrh and cinnamon that rendered heavy the air of the chemist's shop.

'Well, she knows her own business, I have no doubt,' thought Mr Proudie, 'and as I cannot help her I had better stay quietly here till Francis Valletort returns and elucidates the mystery.'

But he found that he could not fix his thoughts on the Gazette, nor, indeed, on anything whatever but the mysterious events of the evening.

He took up an old book of medicine and passed over the pages, trying to interest himself in old prescriptions of blood root, mandrake and valerian, gentian, flax seed and hyssop, alum, poke root and black cherry, which he knew by heart, and which did not now distract him at all from the thought of the woman in her rich foreign finery, her distress and distraction, who had come so swiftly out of the night.

Now she had gone, uneasiness assailed him—where had she disappeared? Was she safe? Ought he not forcibly to have kept her till the return of Francis Valletort, who spoke both French and Italian? Certainly he had been the cause of the lady's visit; she had said, again and again, 'Valletort—Francis Valletort.' The apothecary drank his spiced wine, trimmed and snuffed his candles, warmed his feet on the hearth and his hands over the blaze, and listened for the bell that should tell of the doctor's return.

He began to get sleepy, almost dozed off in his chair, and was becoming angry with these adventures that kept him out of his bed when the bell rang a third time, and he sat up with that start that a bell rung suddenly in the silence of the night never fails to give.

'Of course it will be Francis Valletort back again,' he said, rising and taking up the candle that had now nearly burnt down to the socket; it was half an hour since the doctor had left the house.

Once again the apothecary opened the door on to the wet, windy night; the candle was blown out in his hand.

'You—must come,' said a woman's voice out of the darkness; he could just distinguish the figure of his former visitor, standing in the doorway and looking down on him; she spoke the three English words with care and difficulty, and with such a foreign accent that the apothecary stared stupidly, not understanding, at which she broke out into her foreign ejaculations, caught at his coat, and dragged at him passionately.

Mr Proudie, quite bewildered, stepped into the street, and stood there hatless and cloakless, the candlestick in his hand.

'If you could only explain yourself, madam!' he exclaimed in despair.

While he was protesting she drew the door to behind him and, seizing his arm, hurried along down Dean Street.

Mr Proudie did not wish to refuse to accompany her, but the adventure was not pleasing to him; he shivered in the night air and felt apprehensive of the darkness; he wished he had had time to bring his hat and cloak.

'Madam,' he said, as he hurried along, 'unless you have someone who can speak English, I fear I shall be no good at all, whatever your plight.'

She made no answer; he could hear her teeth chattering and feel her shivering; now and then she stumbled over the rough stones of the roadway. They had not gone far up the street when she stopped at the door of one of the mansions and pushed it gently open, guiding Mr Proudie into a hall in absolute silence and darkness. Mr Proudie thought that he knew all the houses in Dean Street, but he could not place this; the darkness had completely confused him.

The lady opened another door and pushed Mr Proudie into a chamber where a faint light burned.

The room was unfurnished, covered with dust and in disrepair; only in front of the shuttered windows hung long, dark blue silk curtains. Against the wall was hung a silver lamp of beautiful workmanship, which gave a gloomy glow over the desolate chamber.

The apothecary was about to speak when the lady, who had been standing in an attitude of listening, suddenly put her hand over his mouth and pushed him desperately behind the curtains. Mr Proudie would have protested, not liking this false position, but there was no mistaking the terrified entreaty in the foreign woman's blanched face, and the apothecary, altogether unnerved, suffered himself to be concealed behind the flowing folds of the voluminous curtains that showed so strangely in the unfurnished room.

A firm step sounded outside and Mr Proudie, venturing in the shadow to peer from behind the curtain, saw his first visitor of the evening enter the room. He was now without mask, hat, or wig, and his appearance caused Mr Proudie an inward shudder.

Tall and superb in carriage, graceful, and richly dressed, the face and head were those of a full-blooded negro; his rolling eyes, his twitching lips, and an extraordinary pallor that rendered greenish his dusky skin showed him to be in some fierce passion. His powerful black hands grasped a martingale of elegant leather, ornamented with silver studs.

With a fierce gesture he pointed to the lady's draggled skirts and wet shawl, and in the foreign language that she had used questioned her with a flood of invective—or such it seemed to the terrified ears of Mr Proudie.

She seemed to plead, weep, lament, and defy all at once, sweeping up and down the room and wringing her hands, and now and then, it seemed, calling on God and his saints to help her, for she cast up her eyes and pressed her palms together. To the amazed apothecary, to whom nothing exciting had ever happened before, this was like a scene in a stage play; the two brilliant, fantastic figures, the negro and the fair woman, going through this scene of incomprehensible passion in the empty room, lit only by the solitary lamp.

Mr Proudie hoped that there might be no violence in which he would be called upon to interfere on behalf of the lady: neither his age nor his strength would give him any chance with the terrible blackamoor—he was, moreover, totally unarmed.

His anxieties on this score were ended; the drama being enacted before his horrified yet fascinated gaze was suddenly cut short. The negro seized the lady by the wrist and dragged her from the room.

Complete silence fell; the shivering apothecary was staining his ears for some sound, perhaps some call for help, some shriek or cry.

But nothing broke the stillness of the mansion, and presently Mr Proudie ventured forth from his hiding-place.

He left the room and proceeded cautiously to the foot of the stairs. Such utter silence prevailed that he began to think he was alone in the house and that anyhow he might now return—the front door was ajar, as his conductress had left it; the way of escape was easy.

To the end of his days Mr Proudie regretted that he had not taken it; he never could tell what motives induced him to return to the room, take down the lamp, and begin exploring the house. He rather thought, he would say afterwards, that he wanted to find Francis Valletort; he felt sure that he must be in the house somewhere and he had a horrid premonition of foul play; he was sure, in some way, that the house was empty and the lady and the blackamoor had fled, and an intense curiosity got the better of his fear, his bewilderment, and his fatigue.

He walked very softly, for he was startled by the creaking of the boards beneath his feet; the lamp shook in his hand so that the fitful light ran wavering over walls and ceiling; every moment he paused and listened, fearful to hear the voice or step of the blackamoor.

On the first floor all the doors were open, the rooms all empty, shuttered, desolate, covered with dust and damp.

'There is certainly no-one in the house,' thought Mr Proudie, with a certain measure of comfort. 'Perhaps Valletort has gone home while I have been here on this fool's errand.'

He remembered with satisfaction his fire and his bed, the safe, comfortable shop with the rows of jars, the shining counter, and the gleaming scales, and the snug little parlour beyond, with everything to his hand, just as he liked to find it. Yet he went on up the stairs, continuing to explore the desolate, empty house, the chill atmosphere of which caused him to shiver as if he was cold to the marrow.

On the next landing he was brought up short by a gleam of light from one of the back moms. In a panic of terror he put out his own lamp and stood silent and motionless, staring at the long, faint ray of yellow that fell through the door that was ajar.

'There is someone in the house, then,' thought Mr Proudie. 'I wonder if it is the doctor.'

He crept close to the door, but dared not look in; yet could not go away. The silence was complete; he could only hear the thump of his own heart.

Curiosity, a horrible, fated curiosity, urged him nearer, drove him to put his eye to the crack. His gaze fell on a man leaning against the wall; he was dressed in a rich travelling dress and wore neither peruke nor hat; his superb head was bare to the throat, and he was so dark as to appear almost of African blood; his features, however, were handsome and regular, though pallid and distorted by an expression of despair and ferocity.

A candle stuck into the neck of an empty bottle stood on the bare floor beside him and illuminated his sombre and magnificent figure, casting a grotesque shadow on the dark, panelled wall.

At his feet lay a heap of white linen and saffron-coloured brocade, with here and there the gleam of a red jewel. Mr Proudie stared at this; as his sight became accustomed to the waving lights and shades, he saw that he was gazing at a woman.

A dead woman.

She lay all dishevelled, her clothes torn and her black hair fallen in a tangle—the man had his foot on the end of it; her head was twisted to one side and there were dreadful marks on her throat.

Mr John Proudie gave one sob and fled, with the swiftness and silence of utter terror, down the stairs, out into the street, and never ceased running until he reached home.

He had his key in his pocket, and let himself into his house, panting and sighing, utterly spent. He lit every light in the place and sat down over the dying fire, his teeth chattering and his knees knocking together. Like a man bewitched he sat staring into the fire, raking the embers together, rubbing his hands and shivering, with his mind a blank for everything but that picture he had seen through the crack of the door in the empty house in Dean Street.

When his lamp and candles burnt out he drew the curtains and let in the colourless light of the November dawn; he began to move about the shop in a dazed, aimless way, staring at his jars and scales and pestle and mortar as if they were strange things he had never seen before.

Now came a young apprentice with a muffler round his neck, whistling and red with the cold; and as he took down the shutters and opened the dispensary, as the housekeeper came down and bustled about the breakfast and there was a pleasant smell of coffee and bacon in the place, Mr Proudie began to feel that the happenings of last night were a nightmare indeed that had no place in reality; he felt a cowardly and strong desire to say nothing about any of it, but to try to forget the blackamoor, the foreign lady, and that horrible scene in the upper chamber as figments of his imagination.

It was, however, useless for him to take cover in the refuge of silence—old Emily's first remark went to the root of the matter. 'Why, where is the doctor? He has never been out so late before.'

Where, indeed, was Francis Valletort?

With a groan Mr Proudie dragged himself together; his body was stiff with fatigue, his mind amazed, and he wished that he could have got into bed and slept off all memories of the previous night.

Bur he knew the thing must be faced and, snatching up his hat and coat, staggered out into the air, looking by ten years an older man than the comfortable, quiet tradesman of last night.

He went to the nearest magistrate and told his story; he could see that he was scarcely believed, but a couple of watchmen were sent with him to investigate the scene of last night's adventure, which, remarked the magistrate, should be easily found, since there was, it seemed, but one empty house in Dean Street.

The house was reached, the lock forced, and the place searched, room by room.

To Mr Proudie's intense disappointment and amazement absolutely nothing was found: the blue silk curtains had gone, as had the silver lamp the apothecary had dropped on the stairs in his headlong flight; in the upper chamber where he had stared through the crack of the door nothing was to be found—not a stain on the boards, not a mark on the wall. Dusty, neglected, desolate, the place seemed as if it had not been entered for years.

Mr Proudie began to think that he had been the victim of a company of ghosts or truly bewitched. Then, inside the door, was found the pewter candlestick he had held mechanically in his hand when hurried from his shop and as mechanically let fall here as he had afterwards let fall the lamp.

This proved nothing beyond the fact that he had been in the house last night; but it a little reassured him that he was not altogether losing his wits.

The fullest inquiries were made in the neighbourhood, but without result. No-one had seen the foreigners, no-one had heard any noise in the house, and it would have been generally believed that Mr Proudie had really lost his senses but for one fact—Francis Valletort never returned!

There was, then, some mystery, but the solving of it seemed hopeless, No search or inquiries led to the discovery of the whereabouts of the young doctor, and as he was of very little importance and had no friends but the old apothecary, his disappearance was soon forgotten.

But Mr Proudie, who seemed very aged and, the neighbours said, strange since that November night, was not satisfied with any such reasoning. Day and night he brooded over the mystery, and hardly ever out of his mind was the figure of the young scholar in his shabby clothes, with the strange face of one doomed as he stood putting his heavy hair back from his face and staring at the little white ring on the old, polished counter.

As the years went by the rooms over the chemist's shop were occupied by another lodger and Mr Proudie took possession of the poor effects of Francis Valletort—a few shabby clothes, a few shabby books; nothing of value or even of interest. But to the apothecary these insignificant articles had an intense if horrid fascination.

He locked them away in his cabinet and when he was alone he would take them out and turn them over. In between the thick, yellow leaves of a Latin book on medicine he found the thin leaves of what seemed to be the remains of a diary—fragments torn violently from the cover—mostly half-effaced and one torn across and completely blotted with ink.

There was no name, but Mr Proudie recognised the handwriting of Francis Valletort. With pain and difficulty the dim old eyes of the apothecary made out the following entries:

'July 15th, 1687—I saw her in the church today—Santa Maria Maggiore. He is her husband, a Calabrere.' Several lines were blotted out, then came these words—'a man of great power; some mystery—his half-brother is an African...children of a slave...that such a woman...

'July 27th—I cannot see how this is going to end; her sister is married to the brother—Vittoria, the name—hers Elena della Cxxxxxx.'

'August 3rd—She showed me the ring today. I think she has worn it since she was a child; it only fits her little finger.'

Again the manuscript was indecipherable; then followed some words scratched out, but readable—

'As if I would not come to her without this token! But she is afraid of a trick. He is capable of anything—they, I mean; the brother is as his shadow. I think she trusts her sister. My little love!'

On another page were found further entries:

'October 10th—She says that if he discovered us he would kill her—us together. He told her he would kill her if she angered him; showed her a martingale and said they would strangle her. My God, why do I not murder him? Carlo Fxxxxxx warned me today.'

'October 29th—I must leave Padua. For her sake—while she is safe—if she is in trouble she will send me the ring. I wonder why we go on living—it is over, the farewells.'

Mr Proudie could make out nothing more; he put down the pages with a shudder. To what dark and secret tale of wrong and passion did they not refer? Did they not hold the key to the events of that awful night?

Mr Proudie believed that he had seen the husband and brother-in-law of some woman Francis Valletort had loved, who had followed him to England after the lapse of years; having wrung the secret and the meaning of the white ring from the wretched wife, the husband had used it to lure the lover to his fate; in his other visitor the apothecary believed he had seen the sister Vittoria, who, somehow, had escaped and endeavoured to gain help from the house where she knew Francis Valletort lived, only to be silenced again by her husband. And the other woman—and the martingale?

'I saw her, too,' muttered Mr Proudie to himself, shivering over the fire, 'but what did they do with Frank?'

He never knew, and died a very old man with all the details of this mystery unrevealed; the fragments of diary were burnt by some careless hand for whom they had no interest; the adventure of Mr Proudie passed into the realms of forgotten mystery, and there was no-one to tell of them when, a century later, repairs to the foundations of an old house in Dean Street revealed two skeletons buried deep beneath the bricks. One was that of a man, the other that of a woman, round whose bones still hung a few shreds of saffron-coloured brocade; and between them was a little ring of white enamel and white stones.

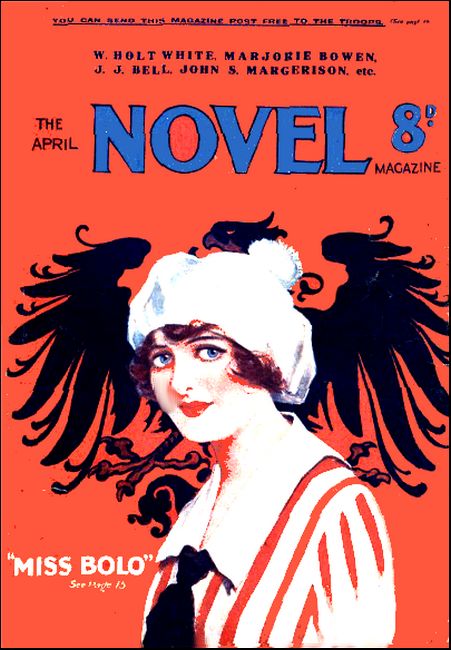

All Story Weekly, 29 June 1918, with "Heartsease"

ABOUT eleven o'clock at night on the 28th of August, 1696, the watchman on duty at the corner of Drury Lane and Queen Street was startled by a woman brushing past him at a run; he had the impression that she had come from the house just behind him, a respectable mansion of some importance.

He raised his lantern and turned its beams on the figure hastening away from him towards Lincoln's Inn Fields; it was a young gentlewoman decently habited, such a one as he had never seen alone after dark in this or any other neighbourhood of London, and he was minded to follow her, but that she appeared in no way discomposed or agitated; he thought that he had heard her laugh, as she passed him, in a contented manner.

"Belike she knows her own business best," he said to himself, thinking of elopements or clandestine meetings in the Fields, and so returned to his box at the corner.

His laggardly conduct was further induced by the weather, which was of a wildness seldom known at this time of year; tearing clouds obscured the moon, now in its first quarter, gusts of rain shook down the silent street, a wind fit to take a man off his feet raged from the north; and there was no one abroad; even the Lane was empty.

The watchman, with his thick cape about him, and withdrawn into the shelter of his box, could not dismiss from his mind that slender figure.

He began to recall certain details that had made little impression at the time; first, she had had no cloak, or mantle, or hat, or gloves, nothing but a muslin cap tied under the chin, and a grey gown of some fine stuff, and a little apron of silvered silk; secondly, she had worn at her heart a great bunch of heartsease—purple, yellow, and white.

He turned his lantern on the house which he thought was the one that the young woman had come from; but now he admitted himself mistaken, for the house was closed and shuttered; he knew that it belonged to Mr. James Fortis, Member of Parliament for Guildford, and that the family had been away some time.

The watchman shivered back into his box, so that he could no longer see the street, and, being warm and comfortable, presently dozed a little.

It was but a short while before the violence of the wind disturbed him and he sat up, almost expecting the box to be blown about his head.

His lantern gleamed down an empty street; he raised it, and saw, with an unaccountable start, the figure of a man standing on the steps of Mr. Fortis' house.

The stranger, who had started violently when the lantern light fell on his face, recovered himself and spoke.

"It is all right, fellow," he said quietly. "I am Mr. Stephen Fortis."

He seemed in some considerable perturbation, and stood there with the wind and rain blowing on him as if uncertain what to do, which air of agitation and hesitancy was foreign to this gentleman, who was a well-known lawyer and man of fashion.

"I thought the family was away, your honour," said the watchman, raising his voice against the storm.

"Everyone is away," replied Mr. Fortis hastily. "I am up from Guildford on business, and my brother lent me the house."

"There will be a servant here, then, sir?"

"There is no one."

"I thought I saw a young woman come from your house, sir; not that she could have been a servant—"

Mr. Fortis, who was a singularly handsome man, turned a face of such distress and alarm on the watchman that the latter was suddenly both suspicious and frightened.