A Collection of Chinese Rarities in the possession of Karl August Graf von Aspremont Reckheim at the Château Halstadt in the Archbishopric of Salzburg. [The Empire, 18th century.]

FIVE MUSICAL THEMES

With an accompaniment for trumpets set for the Imperial Army of the Czar of All the Russias under Prince Zadikov at the Château Brockenstein. [Bohemia, 18th century.]

Variations on a Spanish theme composed for the Duque de Sommaja by Carlo Barlucchi. [Spain, 18th century.]

Set for the Imperialist forces under the command of Albrecht von Wallenstein, Duke of Friedland, Sagan, Glogau and Mecklenburg, Count Palatine, at Castle Karolsfeld, outside Nuremberg. [The Empire, 17th century.]

A Florentine night-piece composed by Nicolo Antonio Porpora for His Serene Highness the Grand Duke Gian Felice of Florence. [Italy, 18th century.]

>Set for His Most Catholic Majesty King Philip V of Spain on his arrival at Madrid. [Spain, 18th century.]

A PLAY

A Burletta performed before His Serene Highness the Margraf Karl Wilhelm of Baden-Dürlach and His Excellency the English Resident, Sir William Fowkes, in the theatre of the château at Karlsruhe, on the occasion of the birth of his grandson, Karl Frederic, afterwards first Grand Duke of Baden, in 1728. [Italy, 18th century.]

DIVERSIONS

...And Prince Clement Louis of Grafenberg-Freiwaldau, Generalissimo of the Imperial Forces, in a summer pavilion outside Mons. [Spanish Netherlands, 18th century.]

A design by Giovanni Battista Piranési for an Almanac by John Evelyn, Esq. [Rome, 18th century]

A philosophic discussion between the Queen of Sweden and some others in the fountain court of a palace in Rome. [Italy, 18th century.]

a visit to verona to see the ruins of the amphitheatre

"When the sun grew troublesome it was the custom to draw a covering or veil quite over the Amphitheatre. This veil they oftentimes made of silk, dy'd with scarlet, purple or some such rich colour. The effect the colour of this veil had upon the audience that sat under it is finely described by Lucretius." (Remarks on several Parts of Europe by J. Breval, Esq., 1726.) [Italy, 18th century.]

Told to the Cardinal Archbishop, Prince Louis de Rohan, at Strasbourg, of the Maréchal le Duc de Villars and the revolt of the Camisards. [Cevennes, France, 18th century.]

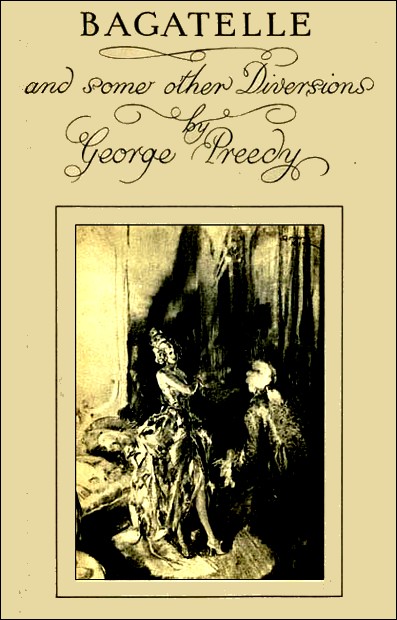

Bagatelle - Cover of First Edition, 1930

The Author who offers these tales has called them Bagatelle (a game, a diversion, a trifle), having been moved to write them through the poignant appeal of those aspects of the past, the decorations of peoples and an age long since gone, which to most appear but a game, a trifle—bagatelle. They might be named, too, stories of empty palaces, of closed mansions, of deserted castles, built to affront the enemy in the game of war, or to entertain the friend in the game of pleasure.

The roofless towers of Karolsfeldt where the oak grows near the hearth of the great hall and the trees of the heavy forest have encroached up to the fallen walls—the tarnished mirrors in the gilt and stucco pavilions hidden in airy woods or agreeable parks—a lonely villa on the Brenta—a straight-fronted, shuttered palace facing the fountain where the gladiators washed their wounds outside the Roman Coliseum—a secret and dark-balconied residence in a narrow street of Madrid—an extravagant château close to the Russian frontiers...These places in their loneliness, decay, neglect and partial ruin still mark the quiet solitudes or forgotten streets of European cities and possess for some a bitter-sweet fascination.

These dwellings, where the long-since dead kept their toys and beguiled the nostalgia for the unattainable (with which we are all so desperately familiar), are easily peopled by phantoms that soon take a definite shape and play out their own story without any help from the writer, who takes the part rather of transcriber than that of author; he is, at least, conscious of no invention and endeavours to describe people and scenes that arise as naturally from these ancient habitations, parks, pleasaunces, as mist from a lake at the close of an autumn day, or pungent perfume from a plucked and dying flower.

Some of the episodes are grim enough; behind the ribbons, the lutes, the cupidons, grins the mask of tragedy; yet—bagatelle—all of it, for these people are dead and seen through the medium of a dream.

They inhabit no known country, but they claim an eternal existence in those memories of the past that torment, perplex and solace some of us; they are purged of grossness; gorgeous ghosts, they enact their parts splendidly, their passions are romantic, their actions seldom lack the heroic outline; since they died their persons have taken on a richer beauty, their characters a nobler cast; they are grander than when they lived; so much we may allow them in recompense for the dust that covers their memories.

Their tragedy shows through a veil of resignation; their comedy is hard, cynical and grotesque, they have a little the air of actors who have played the same part many times, for they are perfect in their words and easy enough to flourish in their gestures; most of them are profoundly lonely and some profoundly unhappy; all feel cheated, thwarted in ambition or passion, or dissatisfied to agony with the bagatelles of their moment.

It may be protested that they are to the last degree artificial, mere puppets adorned with tinsel, but to those who understand them they have the essence of accomplished, successful humanity, disappointed (as always) in its final achievement; they are worldlings defying their own negation; they are creatures who pile up games and trifles at higher cost with fiercer greed, the more they realize their own futility; the men taste the brittleness of success, the women the limits of beauty; all, men and women, pursue each other in vain hoping to clasp the long-lost, the perfect lover, and always embrace delusion.

Their world is opulent about them and all is man-created; they move in palaces, pavilions, parks, gardens; if they glimpse a cottage, a heath, a field, they turn away wearily; the open country means a battle, a hunt, or boredom; to a siege, a chase, a march, a journey, they desperately carry the elements of carnival, music, players, clowns, dwarfs, fine clothes and furniture.

They discuss philosophy (that cloudy disguise of lack of faith), they bandy terms, but they believe in nothing save their own secret and endless disappointment.

The writer who has evoked them despairs of rendering them as they appear to his "inner eye," but has not lacked earnestness in the attempt.

A Collection of Chinese Rarities in the possession of

Karl August Graf von Aspremont Reckheim at the Château Halstadt in the

Archbishopric of Salzburg. [THE EMPIRE, 18th Century.]

The covered waggon, with faded blue hangings drawn closely at the sides, halted at last, after a long journey, at the gates of Château Halstadt, one of the finest mansions in the Archbishopric of Salzburg. Captain Engel van Dollart dismounted from beside the driver's seat, gave a thick grunt of relief, took off his shabby hat and scrub wig to wipe a bald, glistening head while he gazed stolidly, unimpressed but satisfied, at the handsome stone piers and rich scroll work of the gates that bore, in every possible space, the arms of Aspremont Reckheim and Zringi.

The Dutchman then eyed the waggon with alert suspicion, as if he feared that some one behind the curtains would draw these and look out; but the rough canvas was not disturbed; the two stout horses stood patient, sweating in the sun; the German coachman and the German grooms on horseback waited with stupid indifference for the Captain's commands.

This personage called up his Dutch servant, a heavy fellow with a waddling gait.

"This is the place, Cornelis. A fine estate, hey? A very wealthy patron, hey?"

Master and man smiled at each other slowly; Cornelis replied with a placid grin:

"You were sure of that, Captain, before you took so much trouble. It has been a very tedious journey."

"A very tedious journey," repeated Van Dollart. "Now I get the reward for it, hein? While I am inside you guard the waggon—careful, Cornelis, careful and prudent to the last. One never knows."

The gate-keeper had now opened to the modest cortége; the covered waggon turned and was driven up the long avenue that emphasized the correct splendour of the mansion. Captain van Dollart followed on foot; it was an August day, clear azure gold, a few snow-white cloudlets floating above the tall trees; on the double-winged staircase of the château, Warriors and Virtues in stone guarded the pretentious entrance; above the tympanum a flag curled on a pole; a glitter of gold threads outlined the arms of Aspremont Reckheim and Zringi.

Van Dollart despised and detested all this display; he was in love with his misty native flats, his trim house of neat dull pink brick with the precise step-gable in the Prinzengracht at Amsterdam, his quiet, heavy wife with the double chin and starched linen hood and collar. Van Dollart was a dour Churchman, a good citizen and, as a man, had only one fault—this was, perhaps, sufficient—he would have done anything for money.

Giving a jealous glance at the covered waggon he ascended the wide stone steps, entered, sombrely and rudely, the grand open doors and asked the waiting lackeys for their master.

The valet stared at the large uncouth man with his clothes of a seaman's cut, his formidable pistols, his resolute, ugly, leather-skinned face, and listened to his broken German.

"Tell your master that I have brought—what he asked for—Captain van Dollart of the 'Water Dog,'" said the Dutchman firmly and cautiously. "It is outside in the covered waggon—what he asked me to get."

While the message was being taken to the master of the château, Van Dollart waited indifferently among the fine marbles, sparkling lustres and silken tapestries of the vestibule. From the window he kept his eye cocked at the covered waggon on the gravelled space beyond the steps, with Cornelis hulking in front of the blue curtains, and beasts and men waiting patiently in the sun.

In a few moments he was conducted into the presence of Graf Aspremont Reckheim, whom he greeted with an odd surly lack of respect.

The noble owner of Halstadt had finished his early repast and was sitting in complete idleness over a stale copy of the "Gazette de France." He was a man more fortunate than Van Dollart (who despised him), believed any man had a right to be; his descent was partly Hungarian; his father's mother was a relation of that Emeric Tekéli who had fought with the Turks against the Emperor Leopold, and his own mother had been a sister of the elegant Zringi who had been executed in Vienna, but who was better remembered for the long, high-waisted coat he had made fashionable in Paris. The Aspremont Reckheims, very loyal subjects of His Imperial Majesty, had inherited the two immense fortunes of these rebel Hungarian Princes, and their present sole representative had received the rank of General Commandant of Hungary, which post gave him, a good Catholic, fine opportunities of keeping in order the Protestants his ancestors had died to assist. Nor had he neglected these chances and was, in consequence, so keenly hated by the Magyars that he sometimes found it agreeable to leave his famous palace at Vesprim (which rivalled that at Kassel for magnificence) for the more sober splendours of Halstadt. Van Dollart, grim Protestant, loathed this ruthless persecutor of the faith, Van Dollart, honest, sober citizen, quiet family man, detested this costly libertine of whom he had never heard anything save what he considered evil, but he continued to serve him, for Aspremont Reckheim paid with lavish prodigality.

For years the Dutchman had brought rarities and curiosities from the East and sold them to the purchaser who never haggled over increased prices; every voyage "The Water Dog" took from Amsterdam there were commissions from General Graf Aspremont Reckheim; each time something more uncommon, more difficult was required, for the soldier was one of the most considerable collectors of his age. Van Dollart was always very clever in nosing after these treasures, very adroit and unscrupulous in obtaining them, very greedy in asking more and more of those orders which, slipped across the tables of an Amsterdam bank, were so readily changed into good golden florins.

In this very room lined with pale green brocade were vases of celadon, clair de lune, and Imperial Yellow, adorned with prunus and magnolia blossom, which Van Dollart had obtained by not the most fastidious means and sold at not the most reasonable figure, while the Ching-Té bowl with fishes in copper-red (three hundred years old, at least) which now held the sugar for the chocolate, had cost the blood of some obscure heathen.

"I expected you before," remarked the nobleman pleasantly; he never asked the Dutchman to sit, but his courtesy was otherwise perfect.

Van Dollart replied without any title of respect.

"What you asked was not easy. I doubted I should do it at all. The return voyage was delayed. And," added the Dutchman grimly, "it was a rough overland journey from Amsterdam. And I had to come myself, there being no one I could trust with a matter like that."

"So I suppose. I believe you always earn your money."

"Amsterdam, Cologne, Coblenz, Frankfurt, Würzburg," recited the Dutchman, checking the stages of his travels on his coarse fingers, "it has been very expensive."

"You want more than I promised—the five thousand rix dollars?"

"Yes. There would not be much profit on that."

"I'll pay more. If the merchandise is worth it—"

"Eight thousand rix dollars?"

"Yes." Graf Aspremont Reckheim agreed easily; he would win half that by the bet with Culembach—besides, this particular rarity was worth it; he smiled in a way that made the Dutchman frown, though most people would have thought the nobleman very agreeable to look at. His notorious face and figure had the dark, swift, impatient Magyar grace and beauty; his name of Karl August suited him very ill, for he had nothing of the Teuton. As the Dutchman pouched the bankers' order he would (without scruple had it been safe to do so) have strangled his customer for a base, dangerous, subtle beast from the East—like the cruel black panther or the sly, slim snake...a persecuting Papist too.

Almost Van Dollart was tempted not to trade with him again...almost—but the money?

Karl August looked at the Dutchman as if he understood those slow thoughts of hate, and continued to smile. He had good cause; he had always obtained what he wanted, and till now, at thirty years of age, he had contrived to escape both conscience and satiety. He had no complaint to make about fortune, and fortune by her continued gifts seemed to show that she had no complaint to make about him; he certainly graced his destiny and embellished all the favours he received from an immoral providence.

"Is she beautiful?" he asked; then added, "You would be no judge."

"Eh, who?"

"The Chinese woman."

"I never thought about it—she is Chinese."

"Young?"

"Young indeed."

"You have her here?"

"Yes, in the covered waggon."

"Is she sad, afraid, angry?" smiled Karl August.

"I don't know. She has never said anything—how should she? She speaks only Chinese."

"You have really been very clever to get her—how did you?"

"A tale better not told. We went inland as far as Chuchow. We had to kill several heathen and one of my men got an ugly cut. Never mind. She is the daughter of what they call a Mandarin—a Princess to them. I can tell you, eight thousand rix dollars is low."

"If she is really beautiful I will give you more. You know I have never cheapened my pleasures." It had always been his pride not to do so; he had always led every fashion, exploited it in the most costly and extravagant way, and never bargained the price; at Vesprim he had a hermitage, a classic ruin in marble, a village of dwarfs, a pyramid, and a temple above a cascade; at Halstadt he had kept his Chinese curiosities; a pagoda, a pavilion, a garden, and, in the house, the rarest collection of famille rose, overglaze of Wan-Li and Chia-Ching, T'ang and Sung ware.

And an exquisite assortment of women's clothes and ornaments.

It was these which had first made him want a Chinese woman to complete his rarities; as he looked at the lines, lustres and lights of the translucent porcelain, this want had become a desire; when Culembach had bet him four thousand rix dollars that he could never gratify so fantastic a wish, the desire had become a longing; while skilfully and cruelly repressing a rebellion in Transylvania his secret thoughts had been of little else than the Chinese woman.

He went to the window, gazed beyond the curtains of peach-bloom velvet made to match the vases Captain van Dollart called "liver-coloured"...there was the small covered waggon, the horses patiently waiting...a Chinese woman inside...Culembach would be furious, not only because of the money, but out of jealousy; neither he nor any other man of Karl August's acquaintance, however much they might boast of their experiences, had ever possessed a Chinese woman.

Van Dollart grinned at him, showing tobacco-stained teeth.

"Will you please come and take her? I want to be on my way."

Karl August preceded the Dutchman into the summer sun; he was considering the sumptuous, exquisite effects he would achieve with his new possession, how delicately she would be lodged in the pagoda of peacock blue tiles, in the pavilion of green and yellow lacquer, and how tastefully he would adorn her from his store of jade, rock crystal, onyx, malachite, rose quartz, enamelled gold and filigree silver.

As they descended the steps the Dutchman said with dull malice:

"She is not alone."

"She has a servant? I told you to provide that."

"No. There is some one I had to bring with her from China."

Karl August paused on the step and looked up; with his hand on his hip, his black hair yet undressed, curling on his shoulders, and his air of swift action impetuously arrested, he seemed like the model for one of the heroic gaudy statues behind him, who flaunted stone plumes into the rich air.

"Who have you brought?" he demanded. "I thought I could trust you, Van Dollart."

"The person who is with her," replied the slow Dutchman, "is better able to look after her than anyone I could have supplied. As a Papist, you will agree."

"As a Papist?" The stare of Aspremont Reckheim was contemptuous for the insolent heretic.

"It is a nun."

"A Christian nun?"

Van Dollart grinned with delight at the impasse before the detested customer.

"Truly a Papish nun. There is a missionary station at Chuchow. They try to convert the heathen. I don't grudge them the name of good women."

The Dutchman licked over his words, considering with relish the dark face turned on him with such angry expectancy.

"One of them was abroad on her errands when she saw us taking the Chinese lady away. And followed. She marched after us to Hangchow. She tried to rescue the Chinese lady. I prevented that, but I couldn't make her leave, she stayed with her day and night."

"And you allowed it?" asked Karl August fiercely.

"My men would not interfere, they thought they had done enough. There was a manner of superstition about it, though one was a heathen and the other a Papist."

"But I thought you had more resource?"

"Resource? I should have had to kill one of them to get them apart. You can do that yourself."

Karl August was not so exasperated as the Dutchman had hoped to see him; his flash of wrath passed; as violence (unchecked, unpunished) was always in his power, he had not yet met a situation with which he could not deal. He descended the stone stairs, leaving the heavy Dutchman behind, and stood before the covered waggon. Cornelis eyed him with stolid curiosity, the Germans were all humility, one drew the blue curtains. Karl August was so eager to see the Chinese woman that he scarcely concerned himself about the nun; but, as they were seated side by side, he could not observe one without observing the other.

The Chinese woman was very beautiful, exactly like those ladies in lacquer, porcelain, rice-paper painting, carved stone and ivory already in his possession; she was pale, pallid gold in complexion, with ebony eyes and hair and a smooth small vermilion mouth, her robe was dead-leaf brown and flecked with those broken lines used by Chinese artists to represent cracking ice; two pins of lapis lazuli were in her glossy locks; the nun wore the garb (rather soiled) of the Ursulines; Karl August saw at once that she was French and well-bred.

"Is it possible?" she asked, "that you are General Aspremont Reckheim, the instigator of this heartless outrage?"

"I am indeed. Captain Van Dollart has, no doubt, informed you."

"Everything." The nun spoke more in compassion than indignation. "You have actually spent a fortune to abduct this unhappy creature from her home and country, and for what purpose?"

"Merely to complete my collection of Chinese rarities."

The nun gave him a challenging look; he had the impression that she was a woman of some experience, and might if a bigot, prove difficult, but he did not greatly concern himself about her because he was so enraptured with the Chinese woman who, for her part, neither spoke nor moved.

He begged them to alight and they obeyed, the Chinese woman responding to a touch from the nun; the covered waggon with the curtains now drawn moved away, the Dutchman staring back with a sombre curiosity and a sulky vindictiveness.

Never had Karl August viewed any dearly-bought treasure with such satisfaction (and he had had his moments of delicious achievement) as he now felt on gazing at the Chinese woman; he was even grateful to the nun for giving her company and protection; nothing, he began to consider, more suitable could have been devised, and he would be willing to return the zealous missionary to China at his own cost.

He conducted them to the Chinese pavilion which he called after the fashion of the day, Bagatelle, and there suggested that the nun should take refuge in one of the convents at Salzburg until she felt inclined to journey back to Chuchow.

The nun declined to leave her charge.

"She is neither a slave nor a toy, monseigneur."

"I happen to have bought her, madame."

With that pity which, with her, took the place of scorn the nun informed him that a human being could not be traded, and that the Chinese woman was a princess, a person of education and culture, that her family would be in grief and desperate mourning for her, and that she herself, during the tiresome voyage by land and sea and land again, had endured every possible discomfort and alarm, "Consoled only by my company, monseigneur."

Karl August, with folded arms, leaning inside the pavilion door, listened while the nun pleaded the cause of the Chinese lady who showed no concern, but stood meekly, her hands in her sleeves.

"The least that you can do, monseigneur, is to return her to her home. I am willing to accompany her to Chuchow."

"Why," he asked, "do you take such a considerable interest in a heathen, a creature held to be of less account than the heretics who are slaughtered like rats in Hungary?"

"She is a woman," replied the nun, "and for your deeds of violence of which you boast, may God forgive you!"

"You try my patience," said Karl August, "the Chinese woman is mine and I shall do as I please with her. I intend you no harm, but do not provoke me. I command much power."

"But I more," the nun defied him, "God, the Pope, and the Emperor are behind me."

Karl August was slightly uneasy at this; he reflected that the three personages she had mentioned were all bigots, and that he owed his own high fortunes to the fact that he had assumed bigotry; no slight to the Church was ever tolerated in the Empire.

"If you attempt any harm to this noble maiden," added the nun gently, "you will bring on yourself the retribution for all your crimes."

Karl August considered this amusing, but tiresome; he asked the nun if she understood Chinese: "if so, demand of the woman if she cannot be content here."

"I speak very little Chinese, but I can assure you that she will die of a broken heart and home-sickness."

Karl August returned to the château, considering how he should, with some decorum, be rid of the nun. The situation was almost stupid, almost touched him with ridicule...he cursed Van Dollart...the man was either a fool or malicious...the nun must go before Culembach knew of her presence...the Chinese woman must appear at the supper where and when he claimed his bet. Meanwhile he sent down to the pavilion a palanquin containing all the Chinese garments and ornaments that he had been for years collecting and gave instructions for the Chinese woman to be elegantly maintained. So occupied was he with these affairs and with thinking of his new acquisition that he forgot his rendezvous at the chase until the hunt swept up to his door, Culembach calling out to him for a laggard, and the horns blowing in jolly fashion of reproach.

Culembach's sister, Hedwig Sophia, rode up and down the gravelled space where the covered waggon had rested. Karl August came out on to the winged staircase to answer her greeting; he was to marry her in six weeks' time and since Van Dollart's visit he had forgotten it; warm-coloured, yellow-haired, voluptuous, Hedwig Sophia smiled under her cockaded hat, waved her whip—had he not recalled the rendezvous of the chase? She loved him and this showed in her looks and gestures, she cared nothing for his reputation nor his wealth. She was infatuated with the man himself; she was a widow and had learnt toleration of male failings; she was very jealous but even more prudent; rather than weary her lover she had resolved to endure his infidelities.

Hastily he joined the chase, excusing himself with Van Dollart's visit—"some new fangles from the East."

"Anything for me?" smiled Hedwig Sophia.

"Everything for you," he lied agreeably. They rode fast, side by side, down the wide allée; he wanted to marry his companion but he was thinking of the Chinese woman and considering that he might delay his marriage so as to have more leisure with his new mistress...perhaps he would take her to Vesprim and enthrone her in the ice grottoes or amid the village of dwarfs—or even build her another pavilion there and a grove of silver birch trees. At the first courteous opportunity he outrode Hedwig Sophia and came up with her brother who was leading the chase through the park of beech and chestnut; he told him that Van Dollart had brought the Chinese woman safe as a pearl shut in an oyster from Chuchow to Halstadt, trust the sly, grim Puritan Dutchman, eh?

Culembach was chagrined; though a reigning prince he was not rich and the wager was high; he laughed and tried to undervalue the prize—a small, yellow, shrunken creature, he knew...such a one had been found abandoned in the Turkish camp outside Buda...Hesse Darmstadt had been infatuate with her, but for his part, he preferred to have his monstrosities in porcelain. "And, look you, Reckheim, I'll see her before I pay."

"She is beautiful," asserted Karl August, with a confidence odious to the other. "And most rare, different from any other woman you ever saw. I would not take for her twice what I paid. Chinese, not African or Turk, like the egg-shell paste of Te-Hua, where the pink is fused from gold. To-morrow evening you shall see her, she is no more than seventeen and, in her own country, a princess."

Immediately he returned from the chase Karl August, refusing the invitation of Hedwig Sophia to ride home with her, hastened to the pavilion called Bagatelle, in the Chinese garden. Lamps of porcelain and lacquer had been lit in the lattice windows; their thin, fine light made long elegant shadows from the delicate leaves of young bamboo and yellow maple; the twilight was hushed and luscious. Karl August peered through the curtains, the Chinese woman was within, she had arrayed herself in one of the robes, coral red, orange-yellow; she had made herself tea in one of his services of Wu Ts'ai or five-colour ware with ruby-backed plates, she had set a branch of pearl-colour maple in one of his bronze vases, and appeared at home and happy; her hands, moving in the wide blue satin sleeves, were like flowers drifting on water, opening and closing in a kind breeze; they were the hue of pale clover honey; where the shadow stole over her throat it was the warm tint of amber; dark gold appeared in her eyes and hair where the light burnished the black lustre; her mouth had the fresh, dewy redness of a petal plucked as it unfolds in early summer from the bud. Karl August did not enter the pavilion; the nun was seated inside the door; her habit appeared grotesque among those Eastern trifles, her face appeared old, ugly, sad, compared with the face of the Chinese woman; as Karl August left Bagatelle he noticed that a wooden crucifix had been fastened over the curved horns hung with bells, at the entrance. He began to be more uneasy, disturbed by sensations new to him; it was remarkable that he, who had committed so many lawless acts of violence, could not now commit another; it would really be easy to force away the nun; he was not, he assured himself, superstitious, and he did not believe in God—scandal could be avoided; why, then, this detestable hesitation?

He passed a disagreeable night; his mind dwelt most curiously on the Chinese woman; he believed she could give new variety to an emotion he had almost staled, she was more than beautiful, she had some magic...

When a flying post brought news from Vesprim of a revolt among the heretics, Karl August was an angry man; he declared that the Emperor's business could wait until he had finished his own and sent orders to his lieutenant to burn and slay without pause or mercy. To punish himself for his cowardice he kept away from the pavilion; but he sent an order to the nun that the Chinese woman must be sent up to the château that evening to sit beside him at his supper-table. The nun's reply was submissive, "But if she is not returned by eight o'clock I shall come to fetch her."

Karl August raged because he could not have the insolent woman removed; sulky and violent he meditated a revenge that would be the sterner for being deferred; he knew himself capable of complete cruelty; his uneasiness increased.

There were six gentlemen at the supper, companions in arms and pleasures. The windows were open on to the monstrous moon, the melody of caged nightingales, on the voices of Siennese boys singing to zithers, and on the steady, recurrent splash of a fountain that was as monotonous as a heart-beat.

The decoration of the room was Chinese. White satin on walls, and chairs with tiny figures of mandarins, a plum-coloured carpet with blue dragons petalled like chrysanthemums, a table of cinnabar lacquer the work of two generations, a hanging lamp of inlaid ivory and shell, services of egg-shell porcelain, sang-de-boeuf, Lang-Yao, and flambé or red copper glaze; some of the priceless curiosities "The Water Dog" had brought, packed among the coffee, tea, pepper and spices in her hold, to Amsterdam. An aromatic odour still clung to these delicate objects; the air was perfumed with cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon and attar of roses; in contrast to this exotic elegance the six guests showed robust and hearty, with their fair, red faces, their curled, powdered hair, their bright coloured velvet and satin coats, their Paris paste and steel appointments cut to a diamond glitter.

The Chinese woman entered, carried in her palanquin; she could not stand for more than a moment on her tiny feet in the slippers stitched with sequins; she was placed carefully, as if she had been a doll, beside Aspremont Reckheim; the gentlemen all gazed eagerly at this curiosity; they were really not sure that she was alive. Her quilted outer robe of sea-green silk being removed by Karl August showed her dress of festival gold, a massed design of webs and blossoms in bullion threads, her sash of azure satin, stiffened with silver wires, her necklets of white jade, of smoked crystal, of scarlet cords with beads of rose quartz, tourmaline and chrysolite; above the smooth black billows of her hair quivered metallic flowers of silver, copper and gold, which appeared finer than nature in filaments, pistils and petals that stirred with the least movement. All of the guests had travelled and each possessed a closet of curiosities, but none of them had ever seen any rarity like this wonder.

She bowed, and then spoke.

A little cascade of meaningless sound soft, mellow as drowsy notes from the soft-plumed throat of a bird, fell from her vermilion lips; she bowed again, folded her hands into her sleeves, was silent.

They murmured surprise, admiration, envy; Culembach had his rix dollars bond ready; he slipped it along the table. Karl August pocketed it without satisfaction; he was tormented by the desire to know what the Chinese woman thought and felt, to possess her mind and soul as well as her person; never had he heard anything so tantalizing as that soft incomprehensible speech; he had never failed, one way or another with a woman before, but now he was baffled; he glowered where he should have been triumphant. And before the Lang-Yao clock struck eight he sent her away because of the intolerable nun, who would, he was sure, keep her word.

Culembach lingered after the others had gone; Karl August scowled at the continued intrusion; he wanted to go down to the pavilion which would be glittering in the moonshine...he had other treasures to give her, a bracelet of yellow jade, a bowl of alabaster so fine as to be transparent, a box of vermilion orange lacquer...perhaps, if he put these before her she would speak again in that meaningless and enchanting language.

The Margraf of Culembach began to praise the Chinese lady...he offered to buy her...

"As a dilettante?" asked Karl August.

"As a man," said Culembach.

Karl August refused to consider any offer; Culembach said that he would give more than money; his Arab-Polish horse called "La Folie," who was the most perfectly trained animal in the Empire, his pair of bleu de roi Sèvres vases which had taken three years to paint. As Karl August remained contemptuous Culembach offered his summer palace in the mountains that the other had often envied. On receiving an abrupt refusal the Margraf, a short-tempered man, purpled in the face; the two parted in dislike of each other; this was the first time that Karl August had quarrelled with the brother of Hedwig Sophia. The Margraf's offers had put the final value on the Chinese woman; she was indeed priceless; her owner could think of nothing for which he would surrender her. Yet he allowed the days to pass without disturbing her, because of the nun, because of some sacred magic which enclosed her, because of something in himself? Was he being drawn into a new unimagined world? He did not know; he became melancholy, moody, yet excited and violent; if only he could discover what the Chinese woman was thinking, if she was happy, if he could make her happy, what she was saying when she bowed and spoke sweetly, rapidly. Every day he visited her and sat, brooding, on a divan, while he watched her; the nun was always present and he had ceased to resent this; he gave the Chinese woman a little zither and she played on it thin melodies of heartbreaking sadness. The greatest pleasure of Karl August was, however, to watch her unperceived, to linger hidden among the maples and bamboos while she walked by the pond or sang at her window, or drank tea, or played with a white cat.

Culembach rode over frequently and tried to bargain for what he called this bibelot de prix. He also seemed fascinated by the Chinese woman whom, however, he had only seen once; the two men began to detest each other; the Margraf pointed out that General Aspremont Reckheim's post was in Hungary—what leave had he to linger in Salzburg, while there was a revolt in his command?

Hedwig Sophia came too frequently to Halstadt; Karl August suspected her brother of making trouble; the lady longed too often to be taken to the pavilion, the pagoda, and on excuse or refusal became too sweetly submissive. She knew, of course, from her brother, about the Chinese woman and she was sick with terror lest she should lose her lover; she was afraid of his abstracted air, his gloomy indifference to her caresses, his dark, sullen face; she wished to marry him and go to Hungary to quell the rebellion, to please him she would have witnessed the slaughter of hundreds of heretics, but Karl August suspended all his affairs.

He gradually made a confidante of the nun; she was of his own world and intelligent; she appeared to like him, she was at least very tolerant; he endeavoured to discover from her every scrap of information about the Chinese woman...her mind, her nature, her habits, what she believed, or wished, or feared...

The nun knew very little; she could not, save for a word or two, understand her companion's speech, but she always declared that she was very home-sick; at night she would weep and pray to a little crystal image which to Aspremont Reckheim was a toy, but to her a god.

Always the nun ended:

"You must assuredly send her home, monseigneur, it is your only chance to palliate a great wrong. No doubt you acted more in wantonness than malice, but now you understand that you have not bought a carving or a jewel, but a human creature."

"Give me some credit," Karl August would reply bitterly, "that I have not molested her."

The nun had a smile for that.

"You cannot. You do not dare."

The haughty, violent man raged. He stared at himself in many mirrors; he had always disliked his person, inherited from a defeated people he had betrayed; no powder could efface that black hair, no art alter those straight fine features, no imperial uniform make him appear of the conquering race. A Magyar, one with those he crushed and slew...he had burnt a church once with a hundred worshippers within, and watched while his troopers thrust the wretches back into the flames...every face shrieking to death had been like his face...detestable, and giving him the air of a renegade. He passionately wished he was like Culembach, the dominant Northern stock...who did he appear to the Chinese woman?

She remained unchanged; patiently she waited through the luscious autumn days. The lilies on the pond withered, the bamboos and maples shed their leaves, the sunshine took a mellower tinge; in meek resignation the Chinese woman waited; only her songs became more plaintive, her music the melody of an exile, and her slanting eyes glittered with tears as she prayed to her crystal god.

"Send her home before the winter," said the nun.

"Sell her to me," insisted Culembach.

"Marry me," implored Hedwig Sophia.

While the Emperor's commands came stern from Vienna:

"Go immediately to Hungary."

Aspremont Reckheim did none of these things. He was entirely, and, for the first time in his life, occupied with his own soul; he ascended to stormy heights and grovelled in murky depths; all his possessions became earthly baubles, the wind in the bare trees at night was of peculiar importance; the sight of the moon touched him to nothingness, and the vapourous sunshine was bitter-sweet to agony; he was in full pursuit of something flying beyond his reach, a chase that would snatch him off the globe into darkness, for what he sought was hidden surely beyond the farthest star.

Culembach one evening penetrated the Chinese garden; he only saw all the lattices of the pavilion flicked down and heard the mournful note of a zither; but Karl August posted a guard of his own regiment round the Oriental pleasance.

With the waning of October came the news of the sacking of his château at Vesprim; the rebels had broken into his costly grounds, smashed the pyramid, lit bonfires in the grottos, kicked to pieces the ice caves, set free the dwarfs in the village. These tiny monsters had frolicked up to the mansion and, mad with liberty, destroyed all they could discover, then drunk themselves to death amid shards of porcelain, tatters of silk and fragments of gilt wood. The rabble had cracked the cedar-wood chapel as if it had been a nut; angels, saints and crucifixes were tumbled out to be trampled into the parterres of the coronary garden. At night the flames of Vesprim appeared to smite the moon; blood, bones, and the value of a million rix dollars were consumed.

Close on this news Hedwig Sophia rode to Halstadt, her mood beyond subterfuge or prudence.

"Why do you linger? See what has befallen. There was no such palace save at Kassel."

"I can build another," he replied sternly, "if I am not too old for playthings."

Golden, rosy, flushed, distracted with emotion, Hedwig Sophia passionately replied:

"Playthings? You think of nothing else. You are a fool for this Chinese woman."

"You know of her, then?"

"Oh, am I imbecile? Theodor, also, is obsessed by her—what is it? I have suffered it long enough...Do you not think of me at all? Do you not think of your duty? You will be ruined, disgraced, if you do not go to Hungary."

Striking her hand with her riding whip Hedwig Sophia trembled in the rich firelight.

"For a Chinese woman!" she cried.

"She is not my mistress," he said dryly. "I cannot even speak to her. I have never touched her."

Amazed and frightened, Hedwig Sophia asked: "Why?"

"I do not know."

"But you keep her there, hidden at Bagatelle? Theodor heard her sing."

"He'll not again. Yes, I keep her there, immaculate. She is like nothing you could imagine, Hedwig. I cannot speak of it."

"But you love me." Hedwig Sophia was hurried into open avowal of her pain. "This is a whim, it can, it must be dispelled. We will go together to Hungary and regain what you have lost."

"I have lost nothing," mused Karl August.

"You have lost me," retorted the passionate woman, "and I was something to you once."

Very little; how women overestimated themselves! He could not tell her that, nor how many fair women, soft, easy, there were in the world, very ready to the hand of a man like himself. Her rank prevented Hedwig Sophia from knowing how ordinary she was; she pleaded with him hopelessly; she really believed the man bewitched, and though she loved him no less for that she endeavoured to sting him with taunts.

"How can you dally here? You must be a scorn at Vienna—nothing will save you if you do not go at once—I could not marry an idler—or, is it a coward?"

"Tell your brother to come and ask that," he suggested, thinking he would relish an opportunity to quarrel violently with Culembach.

"I will, oh, I will!"

She flung away; he thought he could hear her angry sobbing long after she had gone; he was indifferent to her suffering, she was pampered, selfish, cruel, as he had been.

The posts from Buda and an Express from Vesprim waited in his antechambers while he was closeted with the nun; he had sent for her from the pavilion, which he had not visited for several days; a faint blue haze lay over the park; the nun warmed cold fingers at the frost-clear fire.

General Aspremont Reckheim stood with his hands clasped behind him; he wore a careless civilian dress and had neglected to pomade the black locks that he detested.

The nun smiled at him pleasantly; her face was peaked and thin between the folds of linen; she stooped slightly, some small dead leaves clung to the hem of her grey robe.

"You have held out against me a long time," he said.

The nun continued to smile.

"I love the Chinese woman," said Karl August.

"Then you will send her home, of course?"

"No."

"You do not love her, Monseigneur."

"It is terrible how I love her—I cannot endure to see her because my thoughts of her torment me so. I meant the affair for a jest, for a caprice, to win a wager and a little mistress for a while. I have been horribly ensnared."

The nun considered him with pity.

"Yes, that is how it happens. One does lightly a wicked deed and it closes on one's soul like a vice."

"I have done worse things," he replied, "and never heeded them."

"Perhaps this is the punishment for them all, Monseigneur."

"It is enough," he sighed. "She is so hemmed in that I cannot approach her...hedged about—what with?"

"Innocence, Monseigneur."

"I have overcome that before."

"Alas, Monseigneur!"

"You have laid a spell round her." He tried to smile. "You have conquered. I will marry her."

The nun shook her head.

"She is not a Christian."

"I will have her baptized; I will give her my mother's name."

"She would not understand. She does not care for you. She only longs for her home. If you keep her she will die."

"I would not let her die. I can make women happy and I love her so much—"

"Then, certainly you will return her to Chuchow. Love has only one way, Monseigneur, it serves, it does not think of self; either," added the nun, "you use a word you do not understand, or you know what I mean."

Karl August looked away.

"What should I do when she was gone?"

"Take up your duty. Return to Hungary and endeavour to obtain justice and mercy for the rebels and heretics your kinspeople."

"It is too difficult. I cannot part with her and I'll not tolerate them. You are defeated."

"Not I, but you, General Reckheim."

He dismissed her; with a sweep of his wide cuff and heavy ruffles he knocked over all the stupid trifles on his bureau, splinters of egg-shell porcelain scattered on the carpet; he stamped on them while the posts waited.

For three days he was shut in his rooms; at nights the frosts fell and the dawns were slow and heavy; a despatch from the Emperor awaited his pleasure; another week's delay and he would be superseded in his command; Culembach wrote violently demanding explanation, satisfaction for an insulted sister; all this was chaff in the wind to Aspremont Reckheim. He went down through the still cold, the bare park to the withered winter-bitten Chinese garden where the pavilion showed stark amid the desolation of the trees; the brilliant tiles were rimed with frost which had melted in drops of moisture on the bells above the horned gate, there was no sound of zither or voice.

"How has this come on me who was so sure of myself? I, who did not know of the unattainable, to be overcome by desire I I, who was always resolute, to be thus baffled I I shall never know her heart or her mind, or what she said in her lovely language; she will never lead me into the world where she moves."

He did not cross the confines of her domain, but, returning to the château, sent a letter to the nun:

Take the Chinese woman back, command my means. I leave for Buda.

And he thought: "When they are gone I will have the Chinese gardens, the pavilion and the pagoda demolished—and never again will I trade with Van Dollart."

General Aspremont Reckheim appeared in the full accoutrements that he had so long put aside, and rode at the head of the troop of horse he was leading to the Imperial headquarters near the ruins of Vesprim. The wan day had wasted to the bleached grey of twilight; the dark soldier saw nothing but a mist-bound horizon; his companions rode apart, awed by his grim air of gloom; he had not reached the limits of the estate before he was overtaken by a Heyduck with a bruised face, urging an exhausted horse; his panted news, gasped out as his master drew rein, was brief.

"The Margraf has carried off the Chinese woman."

This was to Karl August as if the scornful hand of God had, out of the menacing sky, struck him one blow...and sufficient.

"They surprised us, five hundred men—the Princess Hedwig Sophia was there—the instant, sir, you had departed."

Karl August turned back at the gallop; by using three relays he arrived at Culembach's château by nightfall.

No one thwarted his entrance; he believed that some catastrophe beyond violence had occurred; he had outridden his company and entered the house alone; room after room was empty and quiet; he would not call her because he did not know her name; in a high ornate chamber he found the nun, very weary, and praying; she saw his face and said:

"You must not kill them. They have been very gentle. Besides, it was too late. She would never have reached home; she was dying."

With her old, tired gait she preceded him to the next room.

The Chinese woman was on a sofa; Culembach and Hedwig gazed at her in silence, holding hands for company in their guilt; Karl August did not see them or their misery; he knelt beside the sofa and said words he had never said before, save falsely.

"Forgive me, for God's sake, forgive me!"

The Chinese woman sat up and looked at him; she bowed, she spoke directly to him, a low murmur of delicate sound. He was sure that she spoke only to him not to the nun; never would he know what she said; she could not speak for long, for she was occupied with the matter of dying. She bowed again and turned to her repose; she seemed to fold herself together, like a flower, furled petal by petal round a dead heart.

Never would his pursuit overtake her, never would she teach him her speech, nor admit him to that world which he now knew of and must ever weary after; never could she relieve his desolation.

Dead, she appeared no more than a toy, Bagatelle, an Eastern puppet on the coquettish sofa. Karl August looked inwards and found detestable company; himself grinning in loneliness.

With an accompaniment for trumpets set for the Imperial

Army of the Czar of All the Russias under Prince Zadikov at the Château

Brockenstein. [BOHEMIA, 18th Century.]

Miss Pettigrew was familiar with Europe and Europe was tolerably familiar with Miss Pettigrew; she had permitted herself every indulgence save an indiscretion; those who knew most about her, applauded her the most warmly—for tact, elegance and an inflexible courage, concealed behind the most becoming air of timidity; those who knew least about her, admired her for a great lady whose dignity was never flecked with blame; all who knew anything of her, conceded her greater gifts than her too celebrated beauty; she never forgot any circumstance, however trifling, and she never lost her composure in any event, however disturbing. She was extremely well-bred and so finely trained that she never allowed any of her lovers to discover that she was an intelligent woman; she knew, exquisitely well, how to give an enchanting air of caprice to the most adroitly conceived plan, how to beggar a man negligently as if she had no idea of the value of money, and how to confer her favours with an air of sweet, overwhelmed reluctance, as if she succumbed for the first and last time; she had a high sense of honour, but this, masked behind the laughing grimace of folly, was a masculine code; that of her own sex, from her early years, she had found trivial and inconvenient. Her secret regret was that she had never met a man quite worthy of her talents; no one with that right mingling of honour and humour, grace and spirit, to deal with her exactly as she was, no more and no less than himself.

Miss Pettigrew had been visiting the Electoral Court of Dresden and had found it rather dull; the most interesting portion of the population was at the war; Miss Pettigrew discovered the time was long between the opening of the campaigns and the closing, when the troops came into winter quarters and made the cities lively. With unperturbed good spirits, however, she retired with the Ursins Trainel to their château of Brockenstein between the darkness of the Bohemian forests and the brightness of the river Moldau. Like thunder on a midsummer day the distant bolts of war rattled in the background of a fête champêtre; Ursins Trainel was an old man, his wife timid, the others of the household were servants; rumours began to deaden the air with panic, refugees pressed against the haughty scrolls of the iron gates of the Park, crept to sleep in the wide allées, and begged for bread at the doors of the château; refugees from Silesia...

Prince Zadikov, the commander of the troops of the Czar of All the Russias, putting under his heel a rebellious Poland, striking a rebellious Silesia, was advancing to face the Circle of Franconia in Munich; with every flash of news that came, fear grew more horrible at Brockenstein; the Ursins Trainel had no interest in the tedious war, but they were technically enemies of Russia...if Zadikov should chance to march that way...no one knew his objective...if it was Munich, then Brockenstein lay directly in his path; M. d'Ursins Trainel was faced with the alternative of abandoning his property, his peasants, his dignity, or risking a visit from Zadikov.

This general had the worst of reputations; cruel, unscrupulous, implacable, extravagant..."a Tartar, in one word," said M. d'Ursins Trainel, sitting gloomily in his great shadowed salon and drinking tea from a cup of powder blue; the small agitated company began to decry Zadikov; there was no crime they did not charge to his account, no vice with which he was not familiar.

Miss Pettigrew sat at a desk slightly apart; her wardrobe was a little depleted; she was making a list for her next visit to Paris: a roll of watered bronze silk for a cloak, a pair of green velvet slippers, a garland of jasmine flowers in pearls...She looked up to listen to what they were exclaiming, in terror and rage, of Zadikov.

"They say he plays the harpsichord exquisitely," she remarked, "I should like to hear him."

"The man is—beyond our discussion," declared M. d'Ursins Trainel coldly, "there is nothing detestable that he has not done—"

"I hear he has good manners," said Miss Pettigrew, reflectively. "I should like to see him."

"You may have the opportunity," replied one of the ladies drily, "and then you would repent your wish—though you have always been slightly enamoured of the Devil—"

"He is, at least, grand seigneur," remarked Miss Pettigrew, "while le bon Dieu—eh, a pity that the Almighty never understood good breeding."

"I fear you have no soul, Miss Pettigrew, possibly no heart," sighed Madame d'Ursins Trainel, "you put virtue at a discount."

"Because it has done so much harm," smiled Miss Pettigrew, "encouraged ill manners, muddy complexions and sour speeches...virtue, eh? What is it but an invention of those who have nothing else to boast of?"

While they conversed there came further news of Zadikov—the worst; he was marching straight on Brockenstein with his Russian and Imperial troops (for the campaign, at least, the Emperor leagued with the Czar), his Cossacks, Uhlans, Black Cuirassiers...a trail of fire, blood and ruin across Silesia as across Poland; he had crossed the Vistula on pontoons, he would soon be crossing the Moldau.

"He grows flowers," said Miss Pettigrew, "he will be interested in your glasshouses, Monsieur."

She added to her list: "blue velvet corsets cut very low, saffron silk garters with knots of coral beads..."

The Château was to be abandoned, every one must fly as best they could, back into Bavaria, to Munich or Nuremburg; every coach, horse and waggon was brought out of the stables; the men looked up all guns, powder, swords, knives; the women ran from room to room, snatching up and packing ornaments of gold and silver, of fine porcelain and alabaster.

Miss Pettigrew disliked confusion and agitation. She retired to her chamber; it was a delightful day in September and from her high window she looked on a voluptuous prospect of shimmering gold—wood, mountain, river, azure horizon...it would be an evening, a night, such as many vaguely love but few know how to enjoy...but Miss Pettigrew was an expert in such delicacies of delight; she leant from the window and allowed the afternoon breeze that floated from the upper plumes of the airy trees to disturb her locks of dark English gold...when her hostess hastened in on her she found her thus with her possessions untouched.

"Are you not packed, Miss Pettigrew? Are you not ready? There is no time, not a moment! Everyone is departing...most are gone."

"Nay, dear Madame, do not be alarmed. I have never heard of women of our position being inconvenienced."

"We deal with Zadikov," Madame d'Ursins Trainel spoke in despair. "He sent a detachment of Cossacks this morning to demand the surrender of Budweis, our nearest town...we have just heard—they refused."

"Fools!" remarked Miss Pettigrew.

"Fools indeed I The town is unfortified...it will fall in half an hour...the Cossacks returned to Zadikov with the threat to pillage the entire country...he will make his headquarters here...Eh, Mon Dieu! come at once."

"I have seen a pillaged town," said the English lady thoughtfully. "I remember it very well—those crazy wretches in Budweis—children, too, and old people...I might have had daughters myself."

Madame d'Ursins Trainel did not listen to this, she was weeping.

"The Burgomaster is here, he has repented his obstinacy and is imploring us to help him; we can do nothing but advise the inhabitants of Budweis to fly with us—"

"Such as have horses or carts," smiled Miss Pettigrew, "I believe the Russians are in excellent condition—how long before they overtook this poor rabble?"

"They must take their fortune!" cried Madame d'Ursins Trainel, distracted. "Do you come and not waste your time."

"I will follow you," replied Miss Pettigrew, to be rid of her. The lady fled, and, in the hurry of her mischances, forgot her foreign guest; Miss Pettigrew called her maid; the girl had gone. Miss Pettigrew herself took from the wardrobe a shift of Indian mull worked with a million white flowers, transparent as a breath of vapour, and a holster pistol inlaid with ivory which had belonged to her father, slain at Philipsbourg; she placed both on her bed and went downstairs; in a short space of time the tumult had stilled; everyone had left the château. From a window on the stairway Miss Pettigrew could see the procession of coaches, of carts, of horses, winding along the high road towards Bavaria; their laborious overladen progress gave them a depressed and defeated air; not every one had left the château. In the salon where lately they had been drinking tea sat the Burgomaster of Budweis—a man overwhelmed by disaster; but he had had the fortitude not to follow the others; he had remained to face the consequences of his own folly; few, thought Miss Pettigrew, can do more.

He rose, the stout elderly man, amazed at the appearance of a lady in the château he had believed so swiftly deserted, stood stammering, for an explanation?

"There is none," Miss Pettigrew reassured him. "I dislike hurried journeys—they have overlooked my absence, no one is of importance in a panic. You, sir, retire to Budweis—?"

"You remain here—alone?"

"My fancies make a crowded company. Why were you so imprudent as to refuse to surrender the town?"

"I was badly advised...the burghers were afraid of their property..."

"And now must be afraid for their lives."

"Alas! if I could die for all—"

"You cannot. Budweis will be sacked to-morrow, unless—"

"Unless?" he demanded, eager at the sparkle of hope in her words.

"Prince Zadikov should prove merciful."

The Burgomaster began sorrowfully to relate some of the cruel stories current about the Russian; Miss Pettigrew interrupted:

"Eh, we all have our legends! Perhaps I can save Budweis."

"You! Pardon me, but you! You remain here...?"

"To meet this Tartar, this monster, this dragon...Compose yourself, sir, and return to Budweis to tell your citizens to hope."

"Pardon me again, Madame, but what do you know of Zadikov?"

"That he is an expert in music—in flowers—we shall have points of contact—the décor, too, the evening, how exquisite! The man must have some sensibility."

The Burgomaster did not quite understand what the lady meant, but he gathered courage from her beauty, her resolute air, her serenity.

"It is a tradition of Budweis," he faltered, "that in the ancient days it was saved from a ravening beast by a virgin martyr—"

Miss Pettigrew kept a smile from her eyes.

"I hope Prince Zadikov will be no more a ravening beast than I am a...a martyr," she replied gravely, not to offend the old man's simplicity. "Now, sir, return to Budweis."

"Shall I not send you some women...at least?"

"Mon Dieu!" murmured Miss Pettigrew, with recollection of some of the good wives of Budweis, "tell them to keep within their walls."

She got rid of him, saw him riding away amazed on his mule, and returned to the emptiness of the château...a virgin martyr She laughed, not without irony and her face became serious; she had experienced so much, the rise and break of passion, the ebb and flow of emotion, the smooth conveniency of compromise, the surge of rebellion, the look of disillusion in her own mirrored eyes the moment before satiety when disgust must be strangled at birth, the moment before consummation when some gorgeous hope must be foregone—she had learnt so much, balance, humour, grace, tolerance, to overlay the tedious years with rich trifles, to enjoy every possible beauty and delight, to keep her dignity immaculate. She had evolved a philosophy and morality in one: miss no pleasure, weary no one and allow no one to weary you, be an epicure in your indulgences...never confess and never repent...flee boredom as the most deadly of the sins...She had not always had as pleasant a background as this, so many clothes in her trunks, so much money in her pockets...she had known her reverses, like Zadikov...she, like him, had been sometimes in retreat, and would be again in full flight one day, before the enemy tracing wrinkles in her face and fading the dark amber of her hair...but, to-day—"Perhaps," said Miss Pettigrew, "we can both be victorious."

She was not alone in the chateau; a negress waited in the corridor, seated on a stool between two gilt model cannon and caressing a silver deerhound; the lady remembered her for doing her a kindness, when Madame d'Ursins Trainel had chided her for laziness; the creature was faithful, then...She looked up at Miss Pettigrew with tears in her handsome eyes and caught the end of her scarf, imploring to be permitted to stay; she, of all of them, had noticed that the English woman had remained in the chateau.

"Poor Corinne," said Miss Pettigrew, "certainly you may stay—there is nothing to be afraid of—the dog, too?"

Yes, the dog was loyal to the negress; he had refused to leave her; they looked charming, the lady thought—Corinne, strong and graceful, her bronze body wrapped in a glittering scarlet tissue, an agraffe of yellow plumes bound to her black curls, the hound fine and light as a curling feather, pale as a moonbeam.

Miss Pettigrew reflected.

"The salon shows signs of disorder, see to that, Corinne; we must be clever and leave nothing to chance. Then you will see what they have left in the house and prepare some supper—set it out, wine and fruit, as elegantly as possible, set it out in the salon."

The negress sprang up, eager and delighted at being used; Miss Pettigrew directed her to arrange the great room that opened so nobly on the terraces and the steps; here a chair overturned, there a vase toppled down, a tapestry awry, a couch upset, a screen fallen, all soon deftly arranged, and the beautiful harpsichord painted with garlands of tender amorini and stately laurels opened, and set in place; fresh candles put in the lustres and in the brackets. Before they had completed these adjustments the patrols of Zadikov were entering the park, frightening the deer, disturbing the cool silence of the long glades; the sun had disappeared behind the high boughs of the chestnuts and elms and filled the air with the vaporous glow of unearthly gold. Miss Pettigrew glanced at herself in the mirror behind the harpsichord; she had made no alteration in her attire, she appeared as an English gentlewoman, in grey sarcenet with slim ruffles, her hair but slightly powdered, her face as it had smiled from the canvas by Mr. Gainsborough when he had painted her but last year.

The patrols had reported the château deserted; Zadikov and his staff rode negligently through the park; Zadikov, whose life had been all action, admired the contrast of this fine repose, the graceful vistas, the flying deer, the lofty, whispering trees, the fastidious château, elegant behind the wide terraces and shallow steps, with the fountain in front where a nereid in marble blew up long jets of water into the azure air. Zadikov and his officers dismounted. The long windows beyond the terrace stood open as if to receive them; the Russians ascended the steps, slowly, carelessly, jaded after the long march. Miss Pettigrew came to the window and looked at them; she was slightly shortsighted and narrowed her eyes in an effort to discover which was Zadikov. Perceiving her, the Russians stopped and spoke quickly, one to another; she guessed what they said—"A trap!" She knew that Zadikov lived under the constant menace of assassination; she came out on to the terrace, to the head of the steps, and one man detached himself from the hesitant group and came straight up to meet her—Zadikov—she knew him better by that action than by his cords and laces, his orders and sashes.

"Prince Zadikov," she said, in French, "I regret that I can only offer you a poor entertainment, such as it is, you are welcome."

He answered in French as correct as her own.

"Whatever it is, I am grateful, Madame."

His officers were crowding up behind him, as if to threaten and protect; Miss Pettigrew smiled.

"I regret, Monseigneur, that I cannot receive your friends—I am inconvenienced by lack of service, of provisions—I am alone in the château."

"You are alone?" he repeated.

"No, I forgot—there is a negress and a dog—the only creatures not afraid of you, Prince Zadikov; will you enter?"

He looked at her steadily; he was as well-trained in quick scrutiny as she; he did not pause but leisurely followed her across the terrace, telling his officers to wait for him.

"You are French, Madame?"

"English."

"Ah—and alone?—here? You knew I was coming..."

"Certainly. And your reputation. I wanted to receive you."

Zadikov smiled.

"Seldom have I had a prettier compliment." He entered the great salon, then filled with golden dusk, following her.

She saw his glance flicker to the large gilt screen behind the supper table; she had not thought of that, nor of the attempts on his life—it would be very natural that he should take this for a trap; she could see the angry suspicious faces of his officers as they, despite his orders, crept closer to the open windows.

"Will you believe that I am alone here?" she asked courteously. "Will you accept my company this evening? I know nothing of politics, little of war—your Highness will risk nothing but—boredom!"

"I am never bored," said Zadikov; he moved so that he stood with his back to the screen; had there been anyone behind it, he could have been killed instantly.

Brave! thought Miss Pettigrew; her blue eyes kindled into a flashing look that gave a radiant lustre to her charming face; she negligently moved the screen, revealing the emptiness of the room.

"Your officers are still alarmed for you, Prince Zadikov; will you tell them to find their quarters elsewhere—there are the farms, the outbuildings, other houses between here and Budweis."

"You command very well," smiled Zadikov, "and you may command my leisure—the day is over." He went to the window and spoke to the officers; Miss Pettigrew saw them reluctantly depart; she smiled to think that they should be afraid of her who was so utterly in their power—an army surrounding her complete helplessness.

She asked her guest to be seated; she took from him his hat with the stiff black cockade, the light cloak covered with autumn dust. She laughed quietly to see how perfectly he controlled what must be a baffled amazement, with what audacious readiness he accepted this improbable adventure; some of the tales she had heard of him ran through her mind; she studied her monster, her Tartar, her dragon, her ruthless devouring tyrant. The appearance of Gregory Zadikov gave the lie to these ferocious epithets; he had a charming, slightly melancholy countenance, devoid of any definite expression, a person more elegant than powerful, a manner of instinctive magnificence well curbed by careful good breeding; those who described him as a bearded Muscovite, or a yellow flat-faced Eastern, were grotesquely wrong; and they forgot what Miss Pettigrew had always remembered, that he had been educated at Versailles. He was set off with the most extravagant of military bearing; his hair was as exactly rolled and pomaded as if he had just left the barber's hands; Miss Pettigrew had seen many a gentleman at St. James's less precisely ordered than Zadikov after his march; nor was there any offence in the reserved scrutiny he gave her; she had read a coarser appraisal of her charms in the eyes of men of a better reputation.

"Why did you want to know me?" he asked, carelessly on his guard.

"I hear you play the harpsichord divinely," smiled Miss Pettigrew, "I should like to hear you."

"Who told you that?" he asked. He had faintly coloured, and amused, she wondered who had last brought the blood to his serene face.

"You grow flowers also, there is one here in the glass-houses I should like to show you—Corona Imperialis, rare, Monseigneur, if not unique."

Zadikov was pulling off his fringed gloves. When Corinne opened the door behind him he did not look round; Miss Pettigrew noted that; he had not had the château searched; did he trust her, or was he outrageously foolhardy? She hoped the latter; she had always wanted to meet a man worthy of her utmost art. Corinne lit the candles, soft blooms of mellow light in the tender dusk; the twilight beyond the windows was a hyacinth azure, the sky above the trees of an infinite depth of voluptuous purple. Corinne had arranged the supper exquisitely—a melon in a silver basket, Bon Chrétien pears on a jade green dish, Venetian glasses with ruby stems, such cold meats and pasties as she had found in Madame d'Ursins Trainel's larder, fastidiously set out, wine in long tawny gleaming bottles...

"Have you enjoyed your life, Monseigneur?"

"Immensely; and you, Madame?"

"I also immensely; an evening like this—lovely, is it not?"

Zadikov looked at her earnestly.

"Lovely, indeed!"

"You have a fine taste—a delicate appreciation—of beauty, Prince Zadikov?"

"No one has denied me that quality."

"I am not concerned with what others you have—only with that. You are fastidious in your choice, and neither scruples nor fears would prevent you taking your choice once you had made it?"

"You read me exactly," he replied; he had lost his artificial look of composure, and she saw that his eager dark face was beautiful.

"And will read you no further, so much knowledge will serve our brief acquaintance."

"Who are you?"

"Mary Pettigrew, of Waygood Boys, Somerset—but it is a long while since I was there. Will you take your supper, Prince Zadikov?"

"I cannot," he said, "read you as you do me; no, not even that little way—"

She poured his wine.

"You are married, Monseigneur?"

"Inevitably and inconveniently, Madame."

"My condolences—for the lady."

"You would not be in her place?" he smiled. "No, I do not see you there—you have never married for you are not a woman—you are an enchantment," he ended with sudden gravity.

"Take me as that and we shall do very well."

"How can I take you as anything else? One must call in magic to explain—an unprecedented situation."

He was close to her now, the other side of the small table, and her level look considered him more keenly; was there not, after all, something dangerous in that face?—the cheek-bones too high, the lips too full, the eyes too dark—a savage, perhaps, beneath the brilliant veneer.

"You sack Budweis to-morrow?"

"Yes. Need we talk of it?"

"I ask you to spare the town."

She saw disappointment darken in his glance, as if he had found the solution of her mystery, and found it commonplace.

"That, then!" he answered, not without an inflection of contempt, "the mouthpiece of those whining burghers—what you ask is impossible. I have heard of Deliliah and Judith—I am not to be wrought on, even by an enchantress."

"I do not try to seduce you," smiled Miss Pettigrew. "Never have I taken less trouble with any man—I did not even change my gown. I have put greater pains into pleasing—those less powerful—"

Her eyes became thoughtful; she was recalling a night in Venice, a rendezvous beneath the Colleoni statue, when she had worn a cavalier's attire—severe, trim, gaitered, buttoned from toe to chin—but, afterwards, in the locked chamber of the Capo del Moro she had worn nothing save a cloud of gauze and diamond garters...Zadikov saw that reflective look, as if she had forgotten him, and he was piqued.

"And yet you make a monstrous request. What is Budweis to you?"

"Nothing. I am a stranger here. I have scarcely seen the place. I ask you not to sack Budweis."

"I have promised my soldiers the plunder. That is sufficient."

"Your word is so inviolable? What is one town more or less to you, Monseigneur?"

"Exactly the same as one lover more or less to you, Madame."

"A trifle, then. And you can let Budweis go?"

"No," smiled Zadikov.

"No?" Miss Pettigrew raised her fine eyebrows. She leant back in her chair, her hands folded languidly in her lap; twilight and candlelight fluttered over her in mellow shade and glow, on all her hues of pearl and amber and rose; she looked past Zadikov at the warmth of the night beyond the open window where troops, trees and heavens were all hidden in one trembling depth of blue, the deep blue of hyacinth, of dying summer, of her own eyes—a little weary, a little veiled by the memory of tears.

Zadikov got to his feet; Miss Pettigrew did not stir; gentle and tranquil she gazed into the night.

"What would you give me if I spared Budweis?"

"Nothing."

"Why did I ask? You could give me nothing I could not take—"

She detected arrogance and impatience in his tone; he had revealed exasperation and given her an advantage she serenely used.

"I never thought to hear a man of quality speak so crudely! I believed you were more subtle. Do you think I stayed here to save Budweis? I wanted to meet you. Do not disappoint me."

"I regret I spoke so—falsely. I know you could give me what no cost or menace could buy—I am not so barbarous—forgive me."

"I see you will not disappoint me. And when I said 'nothing' I was wrong. If you will spare Budweis I will give you the new lily, Corona Triumphalis, Corona Imperialis, which grows very well in the glasshouses here."

"A town for a flower!" smiled Zadikov. "It is true that I am an ardent collector—but, no."

Miss Pettigrew pressed him no more; she went to the harpsichord and set out a sheet of music, and lit the candles either side; the quivering reflections gleamed on the wreaths of amorini, of laurels. "Will you play for me?" smiled Miss Pettigrew—"it is a lovely night; do you not sometimes consider how soon they pass—nights such as this, so warm, so still, the sweeter the dream the briefer—and, who knows if, in the last sleep, we dream at all?"

"I've thought of that," replied Zadikov unsteadily, "is it that which torments us?"

"We miss so much," said Miss Pettigrew. "A hundred years hence we shall be ghosts in an old story—no one will care if Budweis was sacked or no—this music will be out of tune and my face fading on a canvas—'Ah, giovenezza, come sei Bella!'—Do you know that melody? How many women have you loved, Prince Zadikov? And if the sum of them all were here to-night would you not find these few hours worth one cruelty foregone?"

Her voice was full of caresses, of tenderness, of invitation, but when he approached her she looked at him with irony.

"Corinne has prepared the apartments of M. d'Ursins Trainel for you, Monseigneur—do you wish for your friends, your secretaries, your valets—you have work to do to-night?"

Zadikov repeated:

"The day is over, and with it those affairs of the day."

"You are well-guarded, eh?" smiled Miss Pettigrew. "How many sentries about the chateau? How many soldiers encamped in the park?"

"You, too, have your defences," he answered. "I think I have never met a woman so well protected."

"You can hardly have met a woman more alone, Monseigneur. I move solitary in all my designs."

"Yet you are unapproachable," he sat down by the harpsichord; he was weary, clouded by melancholy. She had roused (he knew not how) old torments that he usually lulled by swift action; the nostalgia for the unattainable, the secret, surprised regret (never confessed) that success, power, glory, were not in achievement what they had seemed in anticipation; the gloom and sadness latent in his blood stirred an intolerable pain; he grinned as if tortured physically, and asked her what she thought of while she pondered by the mute music?

"Of our deaths. If you die first I shall hear of it—the battle, eh?"

"Please God," Zadikov crossed himself.

"But, perhaps, an assassin, an illness, possibly the scaffold, Monseigneur—at least pomp, high above the crowd—clamour and amaze, But if I die first you will hear nothing—it will be obscurely one night when the candles are put out for the last time, when the wreaths and garlands are withered, to be no more renewed, when the silks are folded away and the gems set aside for another woman's pleasure...Play to me, Prince Zadikov, and give me another memory."