There were no chapter or section headings in the paper book from which this ebook was made. A line of capitalised text marked the beginning of each "section." Numbers have been added to this ebook, at the point of each line of capitalised text, to aid in navigation. The capitalised text has been replaced with appropriate upper and lower case text.

| § 1 § 2 § 3 § 4 § 5 § 6 § 7 § 8 § 9 § 10 |

§ 11 § 12 § 13 § 14 § 15 § 16 § 17 § 18 § 19 § 20 |

§ 21 § 22 § 23 § 24 § 25 § 26 § 27 § 28 § 29 § 30 |

§ 31 § 32 § 33 § 34 § 35 § 36 § 37 § 38 § 39 § 40 |

§ 41 § 42 § 43 § 44 § 45 § 46 § 47 § 48 § 49 § 50 |

§ 51 § 52 § 53 § 54 § 55 § 56 § 57 § 58 § 59 § 60 § 61 |

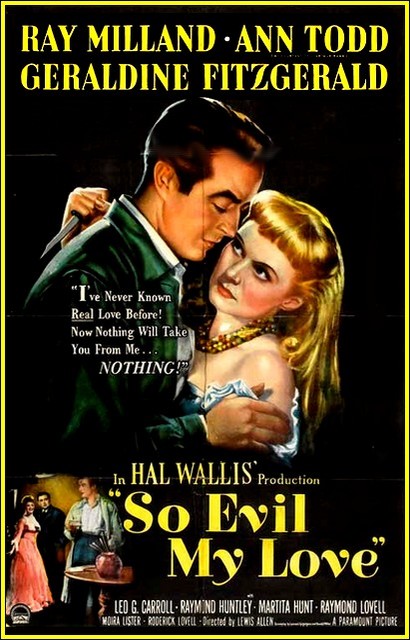

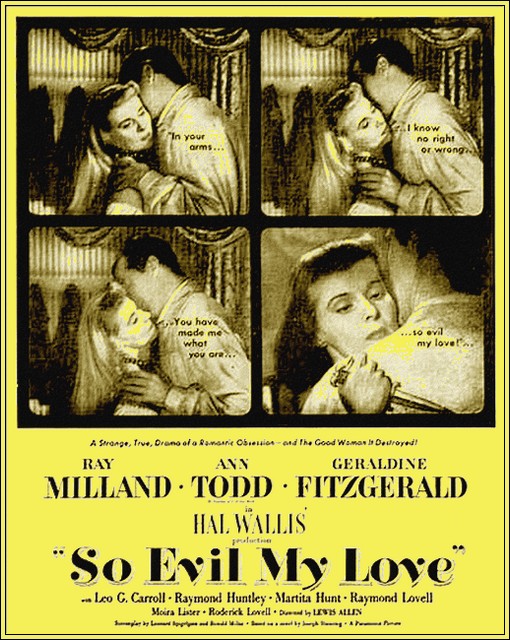

"So Evil My Love"—First edition book cover and poster for 1948 film

There was very little for her to see as Mrs. Sacret closed the mean door, on her empty home. There was no one in the street of small, ugly houses, the sky was a fleckless and pallid blue, the highroad that closed the vista showed cheap shops that were shuttered against the bleak Sunday, wisps of straw and paper lay in the gutter.

Mrs. Sacret paused and contemplated her surroundings with resentment that was the more acute as she realized that she was not more attractive than her neighborhood. A slight woman, thirty years of age, with ordinary features, hazel-colored hair and eyes and a subdued bearing, her graceful figure and feet were hidden under the shabby bombazine of a widow's mourning. Wrinkled cotton gloves concealed her hands; a black straw bonnet was tied by black ribbons under her chin and a crape veil concealed her face; she wore a silver brooch from which hung a cross twisted with a spray of ivy. Her pretty feet were deformed by trodden-over boots, their elastic sides were revealed as she bunched up her long skirts, awkwardly full in the gathers, under her mantle; her clothes had been made in meek and resigned imitation of the fashions worn by gentlewomen.

Mrs. Sacret had passed a dull day in considering her future, a subject that she could not hope anyone was interested in, besides herself. The widow of a missionary whose life and death were obscure, who had bequeathed her but a few hundred pounds and the little house before which she now hesitated, she had, since her return to England three months ago, been seeking a livelihood with daily increasing eagerness.

At first she had felt sure that some mission or society concerned with the spreading of the gospel message or the lot of the industrious poor would have secured her services as secretary or manageress, as matron or sister, and she was familiar with many who were ably directing the labors of those hard-working men and women employed in converting heathens abroad, or rescuing paupers at home. Mrs. Sacret had not only failed to obtain any such post; she had been made to realize the social disadvantages attaching to Dissent. In Jamaica these had not been obvious; if the Sacrets' humble mission was ignored by the Church of England chaplains, it was also respected by the Nonconformists among the sugar planters, and looked up to with awe by the Negroes who transformed all brands of Christianity into melody and color. In London Mrs. Sacret found the dividing line had become a wall—"only a Dissenter" was a usual term that dismissed as beneath notice the followers of a movement that had once overturned the country.

Thus forced back on the organizations run by sects of her late husband's beliefs, or near them, she had found them poor, largely run by volunteers, and indifferent to her plight. Frederick Sacret had not been in any way distinguished from his fellows save by certain good looks and attractions discernible only by his wife, and by her forgotten long before his death from yellow fever in a Kingstown hospital.

Nor was she, the daughter of a medical man and an Anglican, without a stiff gentility that made her slightly ungracious even when asking for a favor, and posts such as she wanted were, as she soon discovered, largely given as favors.

Still pausing in the empty street, her situation confronted her once more in the inner chamber of her mind where her alarmed wits sat in council.

Her parents had died when she, an only child, was a girl. Such relatives as she had were remote strangers; she was sure they would repudiate her and her misfortunes. An attempt to approach them on her marriage had led to rebuffs. Her father, who had never been more than the least popular doctor at Ball's Pond, Islington, was supposed by his family to have lowered his class, that of small Kent squires, by marrying the daughter of a local haberdasher, and Olivia, his child, had certainly descended again, by choosing a Dissenter and a missionary for her husband. The friends she had made at the Clapham School where she had been educated through the exertions and privations of her parents were scattered. She was never noticed either by mistresses or scholars and she had been at the select establishment only a year, for when her father died it was no longer possible to pay the fees.

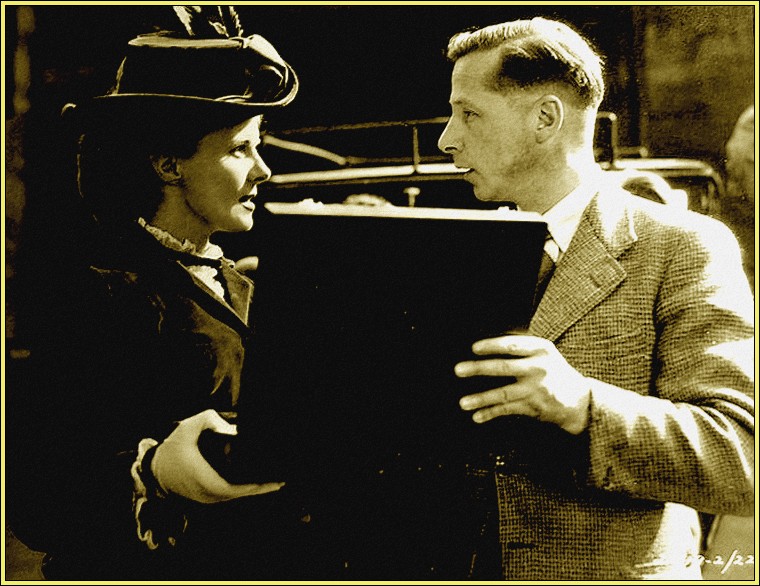

Ray Milland and Ann Todd in "So Evil My Love"

One girl had been kind, generous, even a little loving to the austere, plain and poor Olivia Gladwin, the pretty creature who had been Susan Freeman, then Susan Dasent, and who was now Susan Rue. Mrs. Sacret thought of Susan as she walked slowly along Minton Street toward drab High Street. She had last seen her former schoolfellow three years ago, when she, the amiable Susan, had been herself a widow, the wealthy Mrs. Dasent; then Olivia Sacret had sought her out and the two women had been very friendly. The episode stood out clearly in Mrs. Sacret's memory, as an exciting space of time, filled with a variety of interesting events, a short interlude in a monotonous life, for the Sacrets had gone to Jamaica a few months after the revival of the schoolgirl intimacy. Their correspondence, at first expansive, had soon ceased, for Susan Dasent could not write more than a scrawl, as Mrs. Sacret, who had so often done her lessons for her at the Clapham School, well knew, and was too lazy to continue even to send scrawls to the woman, who, in every sense of the word, had left her world.

A printed card with a penciled greeting had informed Mrs. Sacret of Susan's second marriage, a year ago. The address was that of a hired home at Clapham. She had not replied and when she had returned to London she had not known where Susan lived; they had no common friend nor acquaintance, the circles in which they moved did not touch anywhere. Though by birth at least equal, for Susan's father was a city tea merchant, and Dr. Gladwin would have considered him his inferior, the delicate intricacies of London society, as finely balanced as a precise work of art, sharply divided the dissenting missionary's widow from the wife of the prosperous and well-placed banker, Martin Rue.

Mrs. Sacret, however, on this dull Sunday afternoon, was resolved to attempt the renewal of the lost friendship. She used that word, firmly, in her mind; yes, she affirmed, it had been friendship between herself and Susan, who had been so lucky with her inherited fortune and her two opulent marriages. Susan who had always been so indulged and flattered, not only because of her wealth, but because she was pretty, easy and soft, good natured, with charming flattering manners. Even if Susan Rue had been in the place of Olivia Sacret, she would have done much better for herself than the missionary's widow could do. She was so gentle, affectionate and helpless that someone would have been sure to rescue her from any distress, while no one ever felt much compassion for Olivia Sacret, with her independent air and the hint of irony in her intelligent glance.

The lonely woman turned into High Street, then proceeded along it to the right; she had some way to walk; the omnibuses were infrequent and she avoided them whenever possible, as an affront to her gentility. She felt some satisfaction in her health. She had always been strong, the climate of Jamaica had not affected her native vigor, and she was well able to undertake the two miles or so to her destination, which was the Old Priory, Tintern Road, Clapham. Yesterday she had seen this address in the Morning Post that she had purchased in order to read the column headed SITUATIONS VACANT.

Nothing had been on offer that she did not shrink from applying for, and it had been with a listless sigh that she had turned over the journal and stared absently at COURT AND SOCIETY. There she had seen the announcement of the return of Mr. and Mrs. Martin Rue from Florence to their new house in Clapham. So Susan, after hotels and hired homes, had now "a place of her own."

At first Mrs. Sacret, lonely in her tiny parlor, had smiled sarcastically. Susan was being ostentatious, she did not come of a class that considered its movements of public interest, nor was her present position, solid as it was, comparable to the least of those remotely connected with the court. She had wasted her guineas to pay for this insertion at the bottom of a gazette to which her husband's wealth just permitted her an entrance.

Then another thought had entered the keen brain of Mrs. Sacret and she had stared at the print as if something extremely useful had been put into her hand, a purse of gold, a weapon of defense and assault, or a rope with which to haul herself from the misfortunes that threatened to suck her down from her precarious comfort and respectability. Here was the address of a friend, she emphasized the word, who would, in many ways, help her, despite the difference in their positions and the length of time since they had met. She was proud with the pride that is the only possible defense against the humiliations inflicted on genteel poverty, with the pride nourished jealously by the woman, chaste as maid, wife and widow, in a society where this virtue is no passport to ease or pleasure, with the pride of the Christian missionary who has been in spiritual domination over the heathen, and proud with the aggressive pride of a Dissenter, secretly ashamed of having left the ranks of a church that the Nonconformists might consider in serious, even damnable, error, but that English society held in unshakeable esteem.

Moreover, she believed in God, she knew herself for a righteous, self-sacrificing woman who desired nothing from life save a decent position where she could maintain her genteel pretensions and expend her energies in good works. The little house in Minton Street, and a daily maidservant, some place of consideration among her fellows and she believed she would be contented. The poverty of her childhood, her humble marriage, a dread of sinking to menial labor, unavowed fears of loneliness and the passive scorn or apathy of strangers who glanced at her once and never again, all made her cautious, unambitious, anxious for security.

Three months ago she had not wanted to know Susan's address; she had even hoped that chance would not bring them together, their characters and fortunes were so ill-adjusted. Mrs. Sacret knew that she herself was intelligent, well informed, industrious and resolute, while Susan was stupid, ignorant, idle and weak. Even their names jarred on their circumstances; the ambitious haberdasher's daughter who had married above her class had christened her child the romantic Olivia, from the heroines of an old play and an old novel, while the wealthy, prosaic parents of Susan had chosen the unpretentious name of an equally wealthy aunt who had been godmother to their heiress.

Mrs. Sacret had persuaded herself that she no longer wished to have any concern in the frivolous useless existence of Susan Rue. She had nearly destroyed the packet of foolish letters her friend had written to her during that brief return of their school days' intimacy, three years ago, when Susan had been so excited over her own affairs and so eager to confide in Olivia, who had been her stay and comfort at Miss Mitchell's Establishment for the Daughters of Gentlemen.

But now, the withering of her hopes, the pressure of her loneliness, the curiosity and envy engendered by solitary brooding, overcame her pride, compounded of such varying emotions, and she walked steadily toward the Old Priory, Clapham.

She was not sure that she wished to meet Susan, to risk finding her among smart, fashionable friends, but to look at the Rues' house, to learn the measure of their affluence—she considered that worth while. At the least it made a point to the empty Sunday afternoon, it would be an excuse for not attending the chapel in Gervase Square for the evening service.—"I went to see an old friend"—No one would miss her at that comfortable gathering, for she always kept herself apart, obviously superior to her company. As she steadily walked along High Street, between the shuttered shops, she thought of the gray chapel with distaste; if the Dissenters did not soon find work for her, she would return to the Church. An Evangelical clergyman would accept her without much demur. She had been brought up in those orthodox tenets, therefore it had been very easy to visit the Ball's Pond Chapel now and then when the preacher was of a particular repute, and there she had met Frederick Sacret. She liked his name, one letter altered and it would be "Secret"; life was only tolerable because of secrets hidden within her mind, guarded, seldom considered, never revealed.

She crossed the wide river by the ponderous modern bridge. A breeze blowing from the left, from the sea, disarranged her clumsy garments, the turned and ironed ribbons on her bonnet; her mourning looked rusty in the pale light. She felt discomfort from the wind and from being suspended above the flowing water, alone and beaten upon by the cold air, but neither the mud flats behind her, reaching to terraces before straight brick houses, nor the leafless trees and featureless huts of the market gardens on the shore before her, depressed her. The Thames and the prospects of gray river, gray shores blank of human beings, and blurred by a blister-colored mist, were not gloomy to the woman who carried her mood with her, and who was self-centered enough to have found the smooth tints, vivid sun and soft airs of Jamaica ineffective because she was unhappy.

She reached the farther shore, skirted the vegetable frontages showing cabbage stalks and untidy chicken runs and took her way along a poor street that led into a better neighborhood, then on to a small open common round which, at gracious intervals, were large suburban mansions standing in gardens overcrowded with shrubs and trees. The scene resembled a village green transformed by the spell of a vulgar magic. Where the noble Norman church should have stood was an ostentatious building of Portland stone, with a heavy spire, shut off by coarse railings and gate from the road. Where the homely inn with the ancient sign should have stood was a large public house, of bright brick and corrugated yellow plaster, with the absurd statue of a black bull on the parapet above the porch. Instead of cottages with flowers in front and orchards behind, there were these solid residences, in varying styles of hybrid architecture, with turrets, towers, conservatories, balconies so unrelated as to appear like the edifices put together at random by an impatient child from a medley of crude models. These ugly mansions, as yet unstained by the soot that rendered dingy the church and the public house, were fronted by stiff double drives, heavy double gates, dark foreign trees and ponderous shrubs with dark, dirt-laden foliage, and backed by the empty sky. Instead of the homely and cheerful gathering of the village green, carriages were driven slowly around and around by stout and ruddy coachmen accompanied by silent grooms. The immobility of these people, who, in their parts as servants, had almost ceased to exist as human beings, the steady sound of the slow moving horses and wheels, added to the somber ugliness of the scene that meant nothing save that money, without taste or tradition to control it, had been used lavishly for comfort, luxury and display.

Mrs. Sacret understood perfectly what she saw. It was Sunday and these cosy folk were visiting one another for tea; the carriages had come from another part of Clapham, or from another suburb. These mansions were not the most expensive in the neighborhood, farther on there would he others, where the inhabitants would not have to endure the old established if recently rebuilt public house, people who could afford two menservants. Her shrewd glance appraised the carriages; they belonged, she was sure, to families even more wealthy than those that surrounded this little common.

She went on slowly, beginning to feel fatigue; the liveried servants ignored her as she ignored them, though she was aware of the curiosity in their sharp eyes, and they were aware that she was a stranger and out of place in this select neighborhood. She wished to ask the way to Tintern Road, but it did not even occur to her that she could question these menservants; she went on as if they did not exist, knowing they were staring after her, hearing the sound of slow wheels and hoofs on the placid air. She passed the large common, crossing a corner of the harsh, urban grass; the faded black of her clothes blended nicely with the neutral tints of her background, English half tones, smudged with a still mist, as a painting is smudged with varnish. She was solitary and weary, conscious that she was on strange ground. Never had she lived in such a luxurious neighborhood as this, nor had any connection with the people who inhabited it. Once she had visited Susan, when they were girls, but the Freemans' house at Wandsworth had not been as imposing as these houses before her now, though far too imposing for her ease of mind; she had never repeated the experience though Susan's parents had been kindly.

She knew that if she ever did reside in such a wealthy suburb as this, it would be as a dependent, a companion, since she had not the qualifications for the post of governess, or as a housekeeper, very little more considered than the rigid servants on the carriage boxes she had just passed. She decided that she would not call on Susan. They were completely out of touch, only embarrassment could result to both of them from her unexpected and almost certainly inopportune visit. Better, she thought, to go back, cross the river and return to the mean decorum of Minton Street where, at least, she felt equal to her surroundings. But as she hesitated on the turn of her steps, she noticed a high wall, at right angles to the common, on which was painted in bold black letters, TINTERN ROAD, very plain for her to see.

It would be poor spirited, she reflected, to return without even looking at Susan's house, so she walked along the empty road that was bordered by the stout walls that concealed mansions and gardens of grandiose proportions. At generous intervals these were broken by gates leading to trim gravel drives, flanked by laurel, privet and lilac borders. On the second of these gates was painted, also plain for her to see, THE OLD PRIORY.

Mrs. Sacret could observe the house when she peered between the iron uprights of the gate, though it stood well back and was partly concealed by laburnum and acacia trees that grew in clusters behind the border of the drive. It was a building in the style of the Gothic revival, feebly copied, with castellated roof below the chimney pots, a tower with pinnacles, arched hooded windows, a Norman porch and wide steps with plaster dogs sitting at attention on the balusters. Mrs. Sacret could see, between the dirty boughs, a glitter of shining glass, the shape of outbuildings, a conservatory and stables.

"A great deal of money," she muttered; then she opened the gates cautiously, intending no more than a closer inspection of Susan's home, and her shabby dark figure, gloomy with the crape-edged mantle and skirt, the black bonnet, the widow's veil, approached the house, steadily, with delicate tread.

Mrs. Sacret was observant and well informed within her limited scope. She had natural taste, never yet expressed, and an ironic cast of mind, so she smiled at the ostentatious house before her, that she knew to be a sham in all the pretensions it implied.

There had never been a monastic establishment here; the name had been given vaguely, because of the supposed character of the architecture that had probably been chosen because of the name of the road by someone who could recall the ruins of Tintern, but not that it was an abbey.

Susan, thought Mrs. Sacret; it was built for her, it is quite new—or she renamed it.

And this reflection on Susan's clumsy stupidity strengthened Mrs. Sacret's self-confidence; she asked herself why she should be afraid of a foolish woman, however wealthy. The knowledge that she could have used money to better purpose than Susan had used it in this ugly place, consoled her for her poverty, her fatigue, and her dim prospects.

The place was truly ugly, even the shrubs and trees were clipped, overcrowded or badly planted, so that they seemed unreal, and they were an unnatural hue from dust; the mist hung in dark soiled drops from the harsh leaves of the mottled laurels, the grass border was without freshness. The house, of large ungainly proportions, was ill set, the stucco painted a drab yellow incongruous with the turreting, the Gothic intention, the chimney stacks, belching slow-rising smoke, were absurd, the monkey puzzle trees behind, crooked and twisted, the Venetian blinds at the windows another evidence of lack of taste. Mrs. Sacret could reasonably smile. Her own mean home was more seemly and pleasing for it was without affectation. But the Old Priory displayed impressive signs of wealth that Mrs. Sacret quickly noted; it was as neat as it was grandiose and the outbuildings, the glittering panes of the domed conservatory, the gardener's cottage in a rustic design, the speckless drive and steps, the shining windows, all showed the patient care of many humble hands.

"I might as well see Susan," reflected Mrs. Sacret and rang the iron chain bell that hung inside the porch. An elderly maid in a street gray poplin uniform opened the door immediately and stared with surprise at the dark figure of the widow smiling through the meshes of her crape veil.

"Can I see Mrs. Rue? Will you please tell her that a friend, Mrs. Sacret, has called—has come a long way to visit her."

The lady was gratified to observe that her genteel manner served her; the maid, though startled, asked her into the hall, and went in search of her mistress.

"So Susan is at home—is it lucky or unlucky that we shall meet?"

Mrs. Sacret glanced about her; the floor was tiled, the staircase marble, a window at the back filled with colored glass, blue, crimson and yellow, the walls were wood paneled and a large ornate iron lamp hung from the ceiling. It was very ugly, it was also very costly and well kept. Mrs. Rue would see Mrs. Sacret and the two friends met in the large room at the back of the house that gave onto the garden; a room luxurious, comfortable, cheerful. There was a grand pianoforte, a brilliant fire, and pots of forced flowers. The furniture was handsome, the chairs were softly cushioned, the tables displayed gold and silver trifles, the pearl-tinted wallpaper set off water colors of romantic scenery in wide mounts and gilt frames. Everything that Mrs. Sacret had ever associated with ease and luxury, if not with elegance and good taste, was present in Susan's surroundings, while she herself was dressed in a rose-hued taffeta, ruffled with blond lace, that was a sharp contrast indeed to the widow's dowdy black garments.

Susan was effusive, in the charming, breathless and rather foolish manner that Mrs. Sacret remembered so well. She ordered tea and pressed her friend with quick questions, the most often repeated of which was—"Where have you been? Why have you not written? I did not know where you were!"

"How should you," replied Mrs. Sacret. "My address is not ever in the Morning Post, that was where I saw yours."

"We must have some sherry!" cried Mrs. Rue, starting up, and with quick pretty movements she had soon brought out a fine cut glass decanter and heavy, glittering glasses from a Sheraton cabinet and poured out the tawny-colored wine, Bristol milk, nearly as strong as an old port.

"Oh, I don't take it," said Mrs. Sacret, "and not before tea."

"Do drink it, I expect you have come a long way."

"Yes, indeed, and not in a carriage either. I live in my little house in Minton Street that you may remember."

"Of course I remember it." Mrs. Rue drank her sherry then poured herself another glassful. "I did not know you were in London—when you wrote to me from Jamaica, after your—I mean—" She was confused, sighed and pulled out her handkerchief. "Oh, dear, you will have thought me so heartless; you wrote of your sad loss and I did answer, but you replied that your plans were unsettled and I never wrote again; do forgive me."

"My plans were unsettled," agreed Mrs. Sacret gently. "And I did not expect you to write, nor any explanations. Indeed, I hardly expected to see you again, Susan."

"Oh, why ever not!" exclaimed Mrs. Rue nervously.

"Our positions are so different. I came to London to look for work—and I haven't found any. It was only a chance made me come here, just the chance of seeing your address yesterday."

Mrs. Rue had drunk her second glass of sherry, she was flushed and restless. Mrs. Sacret thought she had been sleeping by the bright fire, sunk in the easy chair, in the room scented with the hothouse flowers, when her unexpected visitor had been announced.

"I'm afraid I startled you, Susan, coming like this—in my mourning. I am so sorry. I should have written; it was just an impulse. I really only intended to look at your house and go away again; then, somehow, I thought I would like to see you. I daresay that was ill advised." Mrs. Sacret sighed, her pleasant voice fell to a whisper. "I've been lonely and poor, and idle, for awhile now, and living so one gets things out of proportion."

"But, of course, I want to see you. I think of you so often," protested Mrs. Rue. "Oh, here comes the tea. Are you sure that you won't have a glass of wine first? It is so refreshing."

"No, just the tea, thank you, Susan, just that and a little talk about the past."

She glanced at the handsome tea equipage with the inevitable curiosity of the poor for the appointments of the rich—heavy silver, Worcester china, extravagant dainties, forced peaches and a pineapple were arranged on Brussels lace.

"We have pineries," chattered Mrs. Rue quickly fidgeting with cups and plates. "Martin is interested in seeing what we can grow. Do you like the house? Martin bought it last year—I altered the name to the Old Priory—because of Tintern Road."

"So I supposed. I know your romantic taste, Susan. No, not any cream, I am not used to rich food; indeed I live very plainly."

"Oh, yes, on principle—as a Christian missionary."

"And because I cannot afford anything but the cheapest fare."

As she ate her sponge finger and sipped her China tea she regarded Susan critically. In her soft pink dress the pretty plump young woman was much like a rose herself, a loosened summer rose, soft, warm, luxuriant; she glowed, with her sanguine complexion, her bright brown hair, her blue-gray eyes, her white teeth, into one radiance that slipped into the pearls around her throat and the diamond bracelets at her wrists. Everything about her was expensive and Mrs. Sacret was surprised that she should be sitting alone on this Sunday afternoon; surely she had any number of friends; but questioned, Susan Rue replied, no, she was not expecting anyone, and Martin was away, spending the Sunday with his mother at Blackheath. "And what was the little talk about the past you wanted, Olivia?"

"Oh, our school days and then, three years ago, when you used to come to Minton Street, after Captain Dasent's death."

"Yes, you were very kind to me then, Olivia; of course I shall never forget it. I don't know what you thought of me, I mean, I was so foolish, feather headed, as you used to say, and you were such a comfort, allowing me to write to you and pour out all my troubles."

"They are over," smiled Mrs. Sacret. "I haven't come to remind you of them. I'd forgotten them until I came upon some letters of yours in an old box."

"Some letters of mine! I suppose you burned them—as rubbish?"

"No, I didn't. I can't think why. I suppose I felt a little tenderly about them—about the days when we were such intimate friends."

"It doesn't matter—they are safe with you."

"Why, Susan, you speak as if there was mischief in your letters—or harm. You know if there had been I should never have been your confidante." Mrs. Sacret smiled charmingly. "And now you are so happy—"

"I don't suppose that you approve of second marriages," interrupted Susan Rue uneasily. "But I was very young—and sad—and not fit to manage my business, and in a conspicuous position—a widow with money.

"Pray don't explain to me, dear," murmured Mrs. Sacret. "Of course you were right to do as your heart bid you—"

"My heart," muttered Mrs. Rue, staring at her untouched cup of tea.

"And you are lucky, also. Two rich husbands—no, I don't mean that in a vulgar sense, but you were just born to be petted and a little pampered, Susan, and to have someone to look after you. I am very glad, indeed, to see you so handsomely established."

Susan Rue sighed. She seemed much disturbed by this sudden appearance of a figure from the past, and her facile, impulsive nature was without defenses against the serene skill with which Olivia Sacret probed into her simple affairs. After a further short conversation the missionary's widow learned that her rich, lovely and indulged young friend was as lonely as she was herself, lonely and a little frightened. Her second marriage was not very successful. Martin was jealous, censorious and mean—yes, that was it, he was mean; though she had two fortunes to dispose of, he watched all her expenditures and begrudged her the comforts to which she was entitled. Why, as Olivia must have noticed, she had not even menservants, and then he disliked her going about, or entertaining, and she led a very solitary life. Martin was always at his office, or with his mother, or worrying about his health. Why, when they were in Florence, where she had expected to be gay, they had hardly left their hired villa and met no one. It was only on his glasshouses that Martin was prepared to spend money, on the pineries, the conservatories. And she, Susan, was tired of the tasteless forced fruit, the pallid forced flowers and the delicate ferns over which Martin fussed so continually—as if they were human. Olivia Sacret listened to this ingenuous confession with a sense of power; at a step she had regained her old ascendancy over this weak nature. Susan felt an obvious relief in pouring out her frivolous, futile complaints to this girlhood's friend, and Olivia slid easily into her old position of confidante.

"You should have waited, dear," she said sympathetically. "And married Sir John Curle. I saw that his wife is still—an invalid."

At this Susan showed a startling agitation.

"Oh, please, Olivia! Don't ever mention that name, now please don't. Martin is so jealous."

"What does he know about it? That name?"

Susan began suddenly to weep. "We were seen together—and talked of—a little—you know—he was married, though Lady Curle had been separated from him so long—and was weak-minded, and someone, of course—I think it was his mother—told him—and he is always casting it up at me."

"Casting what up?"

Susan sobbed speechlessly.

"Why, I never came here, after all this time, to distress you," cried Mrs. Sacret rising. "I never thought—I supposed you were happy—there now, do dry your eyes, before the maid comes, or what will she think I have done to you?"

Susan made a childish effort at control.

"I never see him, now, never," she murmured. "It is all past—and I can trust him—"

"Of course. I don't see why you disturb yourself. I'm sorry I mentioned the letters—"

"The letters, please, please, burn them, Olivia."

"Certainly, if you wish. Only—"

"I know what you want to say. I ought to have thought of it before—to have looked you up—to have done something for you."

"What do you mean, dear?" asked Mrs. Sacret softly, bending over the voluptuous figure of her friend in the soft scented silks and laces. Susan Rue glanced up with wet, frightened eyes.

"You said you had not found a post—and that you were poor."

"Yes—hut I know what to do."

Susan shrank from the serene gray eyes whose gaze was fixed on her so steadily. "Of course," she whispered. "I understand. Will you come and live with me? I need a companion."

"I did not think of that position," replied Mrs. Sacret, concealing her intense surprise, "in anyone's house."

"Oh, I mean as a friend—as if you were a sister, everything as I have it—and—and—pocket money."

"Pocket money?" repeated Mrs. Sacret.

"What do you want?" asked Susan Rue wildly. "I can only give you half of what I have myself—by pocket money I meant a salary—say two hundred a year—and presents—and nothing for you to do."

"How extravagantly you talk," said Mrs. Sacret, withdrawing across the hearth. "I never came here to ask for anything."

"I know why you came. I've often expected you'd come. But I thought you were in the West Indies—you were always a good friend to me," added Susan rising. "And I have no one," she dabbed her eyes, "to talk to—and I'm sure I'm not offering you too much. I'm very tiresome to live with."

The maid entered to fetch the tea equipage and Mrs. Sacret skillfully turned the conversation to an easy commonplace, under cover of which she took her leave, kissing Susan's hot cheek kindly and promising "to think over" what had been said and to "write soon."

The missionary's widow found her little house mean and even bleak after the luxury and comfort of the Old Priory. It was easy to smile at Susan's ignorance and poor taste, but the interior of her pretentious dwelling was, Olivia Sacret considered, desirable. She had not before noticed how agreeable money could make life. When she had last seen Susan she had herself been absorbed in her own affairs, her marriage and her work; both had then seemed exciting, now, in retrospect, dull. She noticed the drafts under the ill-fitting doors, the rubbed drugget, the sagging chairs. She had never tried to make her home pleasant, believing vaguely, that to do so would be frivolous, even wrong. She sat long beside her scanty fire, in the light of the oil lamp with the opal globe, thinking of Susan, and then, with a start, of God. She should pray for Susan, so worldly and so selfish, and she was surprised that she had forgotten to advise her friend to pray, to question her on her religious duties that she had never faithfully fulfilled. Mrs. Sacret could not understand how it happened that she had so lost, not only her professional manner but her professional attitude of mind, when with Susan. Usually she was suavely ready to offer spiritual consolation to the distressed. She supposed it had really been astonishment that had so shaken her out of her mental routine. Astonishment at Susan's confusion, her confession of an unsatisfactory marriage, her dismay over the letters, and her extraordinary offer to Olivia—an offer beyond even Susan's reckless generous nature to make.

"She was frightened." The three words almost formed themselves on Mrs. Sacret's pretty lips; a stir of impatience made her rise and, taking the lamp, go into the basement kitchen. She prepared herself a tidy supper of cold ham and cocoa, while she pondered: Frightened of what?—and ate it, sitting at the scrubbed table and staring at the cold black-leaded grate.

The letters. So she thought of them now, as if they were the only letters in the world. Susan had wildly hoped that they were "safe," had asked that they might be destroyed, but Olivia Sacret remembered them as harmless, ill-written chatter, silly accounts of her flirtations with Sir John Curle, and her regrets as to his hopeless marriage. Mr. Sacret had not liked Susan's behavior, he had said she was being "talked about," though she was always prudently chaperoned by relatives or paid companions, and had wished his wife to discountenance the lovely widow. But Mrs. Sacret had continued to receive the confidence of her friend and to allow her to visit the house in Minton Street, not only out of sympathy with one who was so gentle and kind, but because, secretly, she liked the romance—there was no other word—that Susan's unfortunate love affair provided. Neither could she see anything wrong in the situation. Susan had behaved very well; her tone had been, from the first, one of renunciation. She had visited Lady Curle in her sad retreat, tried to make friends with her, and had, together with Olivia, prayed for her recovery to normal health. Nor was Sir John less noble; his attachment to Susan, though sudden and violent, had never, she had promised Olivia, been more than whispered. And soon after the Sacrets had gone to Jamaica, he had left England. Nothing could have been more proper, though Olivia had considered the second marriage regrettable. Susan should have remained a widow, but she was so weak!

Susan was so weak. Mrs. Sacret shivered. The kitchen was cold. It was stupid to be wasting the fire in the parlor; she left her soiled dishes on the table, took up her lamp again and ascended the short steep flight of mean stairs; in the narrow passage she paused. The letters were in her bedroom, in the bottom of a hair trunk; she wanted to read them again for she had forgotten all of them save their general trend. She had never even read them carefully, as she had never listened carefully to Susan's gushing talk. But it would be mean to read the letters with a curious, prying eye. They must be burned, as Susan wished, and burned unread, that would be the honorable action.

Olivia sat again between the lamp and the fire that she mended with a frugal hand. Thoughts had been aroused in her that were not easily dispelled. Surmises and questions raised not lightly parried or answered.

She again forgot God and the prayers she should have put up for Susan, so unhappy and bewildered.

The missionary's widow drooped in her hard chair, her graceful body taking on lines of unconscious elegance. She considered the sharp difference between her fate and that of Susan's. For her, next to nothing, and soon, nothing at all, but the position of an upper servant, scarcely higher than that of the gross, servile men she had seen today behind the fat horses, lazing away the barren Sunday afternoon. For Susan, everything that most women desired. But Susan was not happy. An intense curiosity stirred in Olivia Sacret. She tried to puzzle out the reason for the other woman's trouble. Susan had always been gay and careless, her only grief had been her hopeless affection for Sir John Curie, but surely that had never been very deep, or she would not so soon have married Martin Rue? Olivia had expected to find Susan, in her usual shallow way, cheerfully content and the center of admiring friends. But she had been alone. And unhappy. I should like to see Martin Rue, reflected Olivia, but checked herself with a false piety, horn of long habit. But I must not be prying, I must be very sorry for Susan and try to help her. Tonight I shall pray for her, and tomorrow I shall burn the letters and write to Susan to tell her that I have done so.

She began to compose the sentences, wise, kind and well turned, that she would send her friend. She would offer her excellent advice about "turning to God," and she would conclude by suggesting that they had better not meet again, as their lives were so different. The room darkened about her; she startled to find the lamp going out with a nasty smell of paraffin oil. She had forgotten to fill it. She had neglected her house in order to undertake that useless walk to Clapham. Olivia Sacret had been trained to feel guilty on the least excuse and "to take the blame" in the part of permanent scapegoat for any daily misadventure. She had always considered that this attitude gave her an air of becoming meekness, until her husband, in the irritable tones of an invalid, had once told her that her ready assumption of guilt covered a secret and unshaken self-satisfaction. Then she had lost her zest for this form of abnegation, but the habit remained. Now she began to think of her afternoon's adventure as not only senseless but sinful.

She turned out the lamp, lit a candle and went upstairs to her chilly bedroom, with the white dimity curtains, white honeycomb quilt on the narrow bed, the framed texts on the cheaply papered walls, the yellow varnished furniture. She looked at once toward the trunk that contained all her intimate possessions; tomorrow she would burn the letters unread. Again she dwelt on the lines that would renounce this unsuitable, perhaps dangerous, friendship. Yes, perhaps dangerous, for it might arouse in her feelings of envy, of regret, a sense of power.

"Our lives are so different," she had resolved to write to Susan, but as she put out her candle and shuddered into the cold bed, her thought was—but Susan offered to share her life with me, and that thought remained with her throughout a sleepless night.

The morning after brought Mrs. Sacret a distasteful post, a refusal to consider her application for the secretaryship of a tract society, small bills from small tradespeople, a letter from the doctor who had attended her husband in Jamaica, "enclosing my account, distressed to send it, but I am not a rich man."

Nor am I a rich woman, thought Mrs. Sacret. This old debt nagged her; she would, now and then, pay a few pounds off, but it still remained, a heavy sum for her poor means. The little daily maid was sullen, the mood in which she usually returned to work on Monday. Mrs. Sacret suspected her of being on the point of "giving notice." The missionary's widow was acutely aware that she was not popular as a mistress; even incompetent servants could "better themselves" in the houses of rich people. It was not so much the low wage that irked as the poverty of the establishment. The hired "helps" loathed having to account for every stick of firewood and pinch of tea; they scorned empty cupboards and all the shifts of genteel penury. "I can manage by myself, of course," Mrs. Sacret told herself as she had told herself before. But she never did so manage, for long. Not only did she secretly dislike housework, she dreaded the loneliness. Another woman who brought in some neighborly gossip was at least some company, someone to talk to, if only in a tone of distant patronage and reproof.

Mrs. Sacret put down her irritating correspondence and rose.

"That is what I have come to—someone to talk to—I really am without friends, or even acquaintances." She was frightened, but added resolutely, "It is the Lord's will." She fetched Susan's letters; they lay beside a few of her husband's books, his spectacles in a worn leather case, some linen bags of cowrie shells and red and black seeds and a papier-mâché box that had belonged to her mother. The letters had been kept out of friendship for Susan and for no other possible reason, Mrs. Sacret was sure of that. She took them downstairs and the fire was burning brightly in the high narrow grate; it would have been simple to have laid them on top of the glowing coals but she hesitated.

Now that this friendship that had meant so much to her, that had been really the most exciting, the brightest episode in her life, was ending, it seemed harsh to destroy these letters without glancing at them again and recollecting the warmth and the pleasure of those few weeks when she had received Susan's wholehearted confidence. She did not glance at the packed lines of Susan's crooked words, she read them carefully, intently, as she had never read them before, read them by the light of Susan's fear and distress and extravagant offer. Then she folded them up carefully and the blood showed in her face, making her appear younger, more comely.

The letters were harmless, of course. Perhaps a little ambiguous. Susan expressed herself so poorly. Some of the sentences might mean what Mrs. Sacret until now had never for a second supposed they could mean, and that, of course, they could not mean.

The gilt-edged sheets were returned to their envelopes and put aside resolutely, as if they had been a temptation. Still with that brilliant glow on her cheeks, Mrs. Sacret picked up the Morning Post and tried to read the column under SITUATIONS VACANT. But her glance strayed from the tedious familiar "wants" that she had never been able to satisfy. She felt a thrill of panic as the deadly fear touched her that possibly she would never be able to qualify even for the more humble posts. She had no impressive housekeeping experience, no talents as a companion, she was not much liked anywhere, had never been needed by anyone. She saw herself being interviewed by a prospective employer and sent away as "unsuitable," she saw herself entering her name on the books of a domestic agency—qualifications? A little amateur sick-nursing, a little meager housekeeping, a Dissenting background, no friends, no "references." I shall not come to that, she resolved, at once, but what is to prevent me—?

She turned over and put down the paper and looked at the letters. She intended to burn them, but while they existed she felt important, even powerful, and she desired to prolong this sensation, even though she knew it was absurd. When the letters were destroyed she would, she was sure, feel unprotected, defenseless, of no consequence to anyone, even Susan. I suppose Susan would give me a reference, she thought. I could ask her for that, even if we were no longer friends. Mrs. Sacret stared at the folded sheet of newspaper. One word heading a paragraph took her eye.

Blackmail.

She hardly knew what it meant at first, then she knew, clearly. Taking up the paper she read the case.

The journalist commented that "this horrible crime was rarely brought to light because social ruin awaited the victim who, at last, in f his desperation, appealed to the law, after having been bled of thousands of pounds for years. Many, in this terrible position, preferred suicide to exposure."

Mrs. Sacret was fascinated by the prospect of unknown and terrible strata of life presented to her by these sentences; for the first time she stared over the edge of her own narrow world, for the first time realized how narrow it was. Crime. She never read even the rare and decorous reports of evil in the newspaper she only bought recently because of the SITUATIONS VACANT column. The Dissenting periodicals and pamphlets, the instructive and enlightening books published by Anglican societies filled her time and her mind.

The reported case was gloomy and pitiful. A man, in his youth, had served a short sentence for petty theft. He had prospered under another name, and one who had known him in prison had blackmailed him for half a lifetime. "Commonplace," the judge had remarked, "and of a fiendish cruelty."

Mrs. Sacret reflected on that. She was in the midst of crime and cruelty in this vast city that she had always considered in terms of her modest, respectable home, the school that was beyond her father's means, the Dissenting chapel set, the wealthy set where Susan belonged, Minton Street, and High Street with the dingy shops and dingy people hastening or loitering along.

Perhaps some of those passers-by were criminals. "Commonplace," the judge had said. People like myself, she thought. I'm commonplace. Perhaps they look as I look.

Blackmail.

She had an impulse to thrust the letters into the center of the fire, between the bars, but was stayed by a sound uncommon in Minton Street, that of a carriage and horses.

It was but a step to the window, and she was soon staring out of it. Susan was without, in an elegant barouche, behind a pair of spruce chestnuts, a footman was coming to the mean door, but his mistress, leaning forward, saw Olivia and waved to her with an anxious smile. So, there are menservants, if not in the house, reflected Mrs. Sacret. No moment to be filling the room with the smell of burning paper.

She turned and thrust the letters behind the worn books of piety on the narrow shelf by the fireside. She felt excited because Susan had come to see her so soon and with such pomp. I certainly have an influence over her, and I must use it to her advantage. This reflection covered her real feelings that were confused, and unacknowledged, even to herself.

The footman brought a request for Mrs. Sacret to join his lady for a drive in the park, but Susan followed him before her friend could answer.

"The dear little room!" she exclaimed, glancing around the parlor nervously. "How well I remember it and how happy I am to be here!"

She was prettily dressed in a mignonette green silk, with dark red roses in her bonnet, but she looked, to Mrs. Sacret's sharp gaze, tired and agitated.

"You will come for a drive, won't you, Olivia? There is sunshine. Have you considered my proposal?"

Mrs. Sacret felt so keen a sense of power over this eager anxious creature that she could not resist using it.

"I have not had time, Susan. It is such an important matter. It would quite alter my way of life if I were to accept. I am not a very young woman." She crept behind the prosy tones and dreary platitudes of her husband's profession. "I am a widow. Frederick would have wished me to continue his work."

"You are going abroad again, as a missionary! You did not tell me that!"

Mrs. Sacret was vexed at this interruption, given in a note of relief.

"Really, Susan, you need not be so anxious to be rid of me! I shall not cross your path. I was about to write to you stating this. I did not suppose that you would call so soon."

"Then you won't accept my offer?" asked Susan, stepping nearer, her bright clothes, hair and face making the room seem very dingy.

"I said I had to think it over—really, I still don't understand it—so extravagant—"

"I have the money, my own money that Martin can't touch."

"I know." Mrs. Sacret thought dryly of Susan's two fortunes, apart from her share in the Rue income. "But your suggestion was so unexpected. I have not even met your husband. He might not care for a third person in his house."

"Oh, Martin often says, when I am moping, or cross, why don't you get a companion!"

Susan was glancing around the room again, her gaze resting at last on the fire.

"Did you burn the letters?"

"I don't understand why you worry so over those letters, Susan. Of course they are harmless, or I should not have kept them so long. I was reading them again—"

"Reading them again?"

"Of course. I wanted to remind myself of those days when Frederick was alive, and we were all happy."

"I was not happy. I nearly went out of my mind."

Mrs. Sacret scorned this confession of what she did not understand, passion. She considered Susan hysterical.

"You soon married again, dear," she remarked softly.

Susan pulled out her handkerchief.

"I do want you to live with me, Olivia. You have always helped me—from our school days—I am quite wretched—"

"Why?" asked Mrs. Sacret kindly. "You have so much."

Susan gave three reasons for discontent; Martin was dominated by his mother, an odious old creature who lived at Blackheath; he was always fussing over his health and doctoring himself; and according to his own morose habits he kept his wife shut away from the life to which she was used.

"How should I help you?" asked Olivia Sacret. "I am not entertaining. I know no one save some dull chapel people. I am outside London society."

"So am I," said Susan. "The Rues are so eccentric they never have moved in any circles—and yet they won't know Father's friends, because he was a merchant, so I am really isolated. No one likes Martin very much."

And you, thought Mrs. Sacret, have not the spirit to create your own life.

"I know you are very religious," continued Susan ingenuously. "And Martin would not allow me to go to chapel. But I could attend church regularly."

"Don't you now smiled Mrs. Sacret.

"Oh, I get such headaches! But that is because I am so moped. There is nothing to do all day."

"It is ridiculous." Olivia Sacret spoke more to herself than to the other. "I must not think of such a thing! It is just a whim on your part, Susan, because you are out of humor."

"Indeed, indeed, it is not—but if you don't like my silly frivolous life, I daresay it would be very boring to you—then I won't tease you—if you'll destroy the letters."

"And if I don't destroy the letters?"

"How can you be so cruel!"

"Really, Susan! There is nothing in those letters—anyone might not see."

Susan sighed deeply and twisted her hands in the pearl-colored gloves. "What do you want?" she whispered.

Mrs. Sacret was startled at her own thrill of triumph. It was as if Fortune had knocked at her door, with both hands full of gifts.

"I don't know," she said slowly. "It is rather late for me to be wanting anything."

"Oh, no," replied Susan eagerly. "You have never had a chance—you were always so bright and clever—"

"But poor, Susan, and plain."

"Oh, no! You have such pretty coloring—your eyes and hair are just the tint of a ripe hazelnut—but those dreary clothes—Oh, I'm sorry, you are still in mourning—but I should like to see you handsomely dressed."

"Would you? You are very generous."

"Only burn those silly letters."

"Of course. But—Susan—supposing I was to burn them, here—in this grate—now—would you still want me to live with you and to see me in fine clothes?"

"Certainly—what do you mean, dear?" But the faltering tone, the quick flush, the averted glance betrayed Susan.

The simpleton! thought Mrs. Sacret scornfully. She doesn't care for me in the least; she is frightened.

Aloud she suggested that the horses had waited long enough; she would like the drive after walking the pavements so long, and she went swiftly upstairs to put on her bonnet and mantle.

Halfway up she recalled that she had left Susan alone with the letters, and paused sharply. But what did it matter? I meant to burn them; besides, she will never think of looking behind the books.

When she returned to the parlor she took the precaution of approaching and glancing at the fireside shelves. Behind the shabby volumes, the letters were still there. Susan was by the window, tapping her foot nervously.

The luxurious drive was a keener pleasure than Mrs. Sacret had believed it could be; not only did she enjoy the comfort and the distinction of her position, she felt as if at last she was in her rightful place and that the social aspirations of the haberdasher's daughter and the squire's son, frustrated in themselves, had now been realized in her. This was what she really was, a lady, not a missionary's widow. Her marriage, the chapel, Jamaica, seemed now not to matter, even never to have happened.

But her present elevation was a delusion; soon she would return to Minton Street and the search for a "situation."

Susan chattered, but with a certain shrewdness, arising, Mrs. Sacret thought, from desperation.

She tried to discover her friend's prospects and hopes of employment and was not easy to mislead on these subjects.

"It must be very difficult for you, Olivia," she insisted. "It will be hard for you to find a position you like—you have been searching for months, haven't you? And though you are so clever, you haven't those horrid, dull qualifications needed for a good post."

"Why do you think I am clever?" asked Mrs. Sacret sweetly. "I haven't been very fortunate, have I? Not done much with myself!"

"I don't think," replied Susan, with one of those uncomfortable flashes of insight that even stupid people will show, "that you ever bothered enough with yourself. You were always rather tired and just did the easiest things."

Yes, that was it, Mrs. Sacret agreed. She had always lacked enterprise, boldness; she had never made anything of herself. Oppressed by poverty and the frustration it brought, she had slipped into the only marriage that was offered, done her duty in an insipid way, tried to earn a living in a timid fashion, yet she had always felt a surge of rebellion, a potential daring. I must have been, truly, as Susan says, tired.

"Yes," she agreed aloud. "I have been lacking in—much. And I am rather weary." Suddenly she disclosed herself. "I have been walking about London for months, looking for work, always disappointed."

"Oh!" exclaimed Susan, grasping her friend's hand affectionately. "You must come with me and rest—even if only for a short time."

"I might, dear," agreed Mrs. Sacret, as the horses turned out of the park, toward Minton Street. "That would not commit either of us to anything, would it?"

Mrs. Sacret prayed to god when she first entered the Old Priory that she might be enabled to help her friend, and she used those words when explaining herself to her Dissenting acquaintances. "I am trying to help a friend, who is lonely and not very happy. I do not know how long I shall stay with her."

No one was interested, she had always been too aloof from the chapel, save when she mentioned her future address, then she saw a gleam of surprise and envy on several dull faces.

They have to admit, she thought, that I have good connections and that I am what I always claimed to be, a gentlewoman.

She resolved to take no money from Olivia; this was to be a visit, no business arrangement. She would stay three months at the Old Priory, then look for a situation, this time from a comfortable background, with more confidence, and among Anglican institutions. Dissent dropped from her easily; she found no difficulty in returning to a church that she had never really left. It would be so much more convenient and improve her standing in her new position. After all, she would not need to change her God or her prayers. "I do really intend to be of service to poor Susan," she assured this Deity and herself.

It was gratifying to be able to pity Susan. A few days at the Old Priory showed Mrs. Sacret, trained in observation of her husband's flocks, her friend's commonplace troubles. Martin Rue had the appearance of a robust young man, blond, comely, a stolid Anglo-Saxon. But his temperament was that of a middle-aged invalid; an expensive education had left him incompetent in everything except perhaps his business of which Mrs. Sacret knew nothing, with no interests beyond his own ailments, his medicine chest and his hothouses.

He was away frequently, either at the city offices of the bank—St. Child's—of which he was a partner, at his club, or with his mother. Although he received Mrs. Sacret civilly he warned her not to encourage Susan in "frivolity" and hinted that she was inclined to make acquaintances of which he could not approve, and that he had had "to drop" most of the people she had known when he married her, including her first husband's family, the Dasents, who belonged to a "fast military set." Mrs. Sacret with her landed gentry descent and her impeccable character was an exception to these strictures, but she felt a common dislike between herself and the master of the Old Priory.

The idleness of the couple interested the guest, used to an ordered existence full of insistent, if futile, duties. Ever since her return to London her search for work had kept her occupied and fatigued. At the Old Priory there was nothing to do when the short daily routine was over.

Susan was a fair if disinterested housekeeper. The servants were adequate, the house comfortable, her husband managed the menservants and the stables and grounds were as orthodox as the mansion; if there was no sign of taste in either, there was none of disorder. Mrs. Sacret suspected waste and extravagance on Susan's part, but these were well hidden. She had her own money as well as her allowance to make good any insufficiencies.

After she had seen the cook and given her orders she had the empty hours on her hands. A visit to the shops, to the dressmaker, to the lending library, a call on some woman she hardly knew, or a visit from some such acquaintance, a drive in the park, such were Susan's days. She had no accomplishments and could not even play croquet or whist, tat or embroider, the only books she read were love stories. When she talked to her new found friend it was always of the past.

The long heavy breakfasts were eaten in silence as Mr. Rue sat behind the Times; the long heavy dinners accompanied dragging conversations Mrs. Sacret found more tedious than silence. The master of the house had the dyspeptic's complaints of his food, the mistress of the house the nervous defense of the woman bored by both the man and his meals. After dinner Mr. Rue would go to his smoking room and Susan and Mrs. Sacret to the pleasant garden boudoir, as it was termed, and there while away the evening, Susan vaguely admiring her friend's active fingers, for Mrs. Sacret could not sit quite idle and would sew or embroider diligently. Once old Mrs. Rue came on a visit; her son was the only child of a late and brief marriage and she doted on him. A large, colorless, expensively dressed woman, she took on life and even brilliancy through emotion when she regarded her daughter-in-law. At once she was frankly menacing to Mrs. Sacret whom she asked into the luxurious bedroom always reserved for her at the Old Priory.

"A queer idea for Susan to have a companion."

"I'm not a companion. A friend."

"Oh! It has been a long visit. A mistake to interfere between husband and wife."

"I never interfere."

"A third person in the house is awkward."

"Not for Susan. She was so much alone."

"I knew she had been complaining. She could find plenty to do if she looked after my son. Before he left home it took all my time to take care of him. He is very delicate."

"This is his home now, isn't it? And I'm sure he doses himself too much; he should see a doctor, instead of making up his own medicines."

The two women exchanged level looks of dislike.

"You would hardly know anything about that, Mrs. Sacret."

"I do. I used to keep a dispensary and learned something of drugs."

"You were a missionary, Mrs. Sacret. Church of England?"

"My husband and I worked as Christians, Mrs. Rue. We never thought in terms of denominations."

"I see, Dissenters," said the elder lady. "My son is High Church. You have a very pretty dress on, Mrs. Sacret—very fashionable for mourning.

"Susan gave it to me," smiled Mrs. Sacret. "She has bought me a wardrobe. I had nothing fit for this house. She has her own money and it pleased her to spend it like this."

Mrs. Rue flushed at this cool defiance, and her faded eyes glanced contemptuously at the other woman's plain, well-fitted cashmere gown, with the delicate cambric collar and cuffs, and the ruffles and buttons of black velvet. Mrs. Sacret's hazel-colored hair was brushed to a pale shimmer and hung in a black chenille net. She wore jet earrings that set off her fine complexion.

"You have discarded your widow's cap," said Mrs. Rue, with a shudder that shook her own starched and crape erection. "And before your year's mourning is over."

"Does that matter to you?" asked Mrs. Sacret sweetly.

The elder woman trembled, her fat fingers pulled at the glossy silk stretched over her fat knees.

"This is my son's home. Susan should think of him—"

"She does. Too much. Too often. She is afraid of him."

"What do you mean! Martin is the kindest of men!"

"And Susan the meekest of women. Perhaps you're glad to have it confirmed, Mrs. Rue—for you must have known it, that Susan lives in fear of your son—of his grumbling, his bad temper, his snubs."

"And she called you in to protect her, I suppose?"

"Perhaps."

"This is very insolent. I shall speak to Susan and you must go. You are making mischief, I can see that. You suddenly appear—"

Mrs. Sacret interrupted.

"No, I was at school with Susan. I've always been in her confidence. I shall not leave unless I wish. Only Susan could make me."

"She shall," declared Mrs. Rue, rising, shaking out her weeds; the two widows faced one another. "I shall desire her to do so."

"Susan will never send me away. I told you she was very meek. Timid. She is afraid of me—also."

"Why?" demanded Mrs. Rue, with an eager, pouncing look. "Because I am the stronger character."

"You spoke as if you had a hold over her—"

"A hold?" Mrs. Sacret smiled haughtily.

"I always thought Susan might have something to conceal—"

"Did you? How uncharitable of you!"

The elder woman, intent on her own line of thought, ignored this and continued.

"I suppose you knew her when she was making herself conspicuous with Sir John Curle, a married man."

"I told you, I've known her since we were children."

"Bah!" exclaimed Mrs. Rue, throwing all civility aside. "I understand you very well. You have everything to gain from Susan, you mean to stay here, in idleness, in my son's house—"

"On Susan's money—"

"She ought to hand it over to her husband."

"So she has. Nearly all of it. Like a fool. But she has kept enough—"

"For what you want. I quite understand."

"And so do I, Mrs. Rue."

The elder woman suddenly lowered her panting voice.

"It was a most unsuitable marriage for my son. A chance meeting at the house of a new acquaintance—and he became infatué with this—stranger. She was being talked about—a silly, common, frivolous creature." Mrs. Rue labored with her venom. "Of course my son soon found out his mistake." She paused, her gasp for breath was a sigh, she approached Mrs. Sacret and spoke confidentially. "If you know anything," she whispered, "it is your duty to tell my son—"

"What could I know?" asked Mrs. Sacret sweetly.

"I thought—usually—it's letters—indiscreet letters. If you had any—"

Mrs. Sacret slightly flinched and the other staring woman perceived this.

"You ought, as a Christian woman, to show them to my son." She cast down her eyes and added, "He would be a good friend to you. He has influence—a position, whatever you want. He is, really, I repeat, the kindest of men."

Mrs. Sacret hesitated on the verge of extreme plain speaking but controlled herself, said "good afternoon" and left the room.

This blunt interview had been exhilarating to Olivia Sacret. She so seldom spoke frankly and there had been a minimum of hypocrisy about Mrs. Rue, who had as good as admitted that she suspected Susan of having an uncomfortable secret and her friend of using this as a "hold" over her. Moreover, the stout widow had practically offered to buy this secret, in order to ruin her daughter-in-law at a higher price than Susan could pay.

Olivia Sacret was not shocked or alarmed; she was, however, extremely interested and her sense of power increased. Now she was important to Mrs. Rue as well as to Susan, she who had been so insignificant, even so slighted.

This was the first time the letters had been mentioned since she had come to the Old Priory, but they were constantly in her mind and she kept them locked in a cashbox she had bought for this purpose, in the bottom of her chest of drawers, which was also locked. She admired Mrs. Rue's shrewd guess. How notable that both she and Susan had at once attached such importance to the letters! Indiscreet? No, they were quite harmless. Mrs. Rue had only surmised their existence, she would suppose them much more compromising than they were. Mrs. Sacret paused in her reflections at this word "compromising"—that was the word people used when they meant that indiscretion caused a doubt to be cast on a woman's reputation.

She threw off the muffling sentence she had mechanically formed. Mrs. Rue wanted to ruin Susan, to be rid of the hated interloper, to regain her son. Therefore Mrs. Rue was prepared to deal with the stranger she had found unexpectedly at the Old Priory and whose presence she could only account for by—blackmail.

Mrs. Sacret used the word boldly to herself; she flushed, not with shame, but excitement. She was too sure of herself and her own motives to feel in the least abashed at the position in which she found herself. Susan felt embarrassed, if not guilty of—indiscretion. Mrs. George Rue had revealed herself as an odious person, mean, jealous, backbiting. Martin Rue cut a poor figure between his overbearing mother and his cowed wife. I must pray for all of them, reflected Mrs. Sacret. I must try to bring peace and good will to these unhappy people. Perhaps God sent me here just for that.

She thought that possibly the consciousness of the worthiness of her intentions was giving her this stimulated energy; she felt more vital than ever before, her old existence shriveled away and she flexed her hand as if pulling strings. It was astonishing to her that she had spoken so sharply to old Mrs. Rue. She had never faltered before the sharp assaults of a woman so much older and better placed than herself; indeed, she had enjoyed her own forceful handling of the interview.

Mrs. George Rue had spitefully remarked on her elegant dress. Remembrance of this 'made Olivia Sacret look more earnestly than usual into her mirror. She was nearly a pretty woman, perhaps could easily be a pretty woman. A strange reflection, this in Susan's handsome cheval glass: the missionary's widow, in her mourning, the woman who had, years ago, parted with all expectations, all hopes of anything save a drab routine leading to the chapel burying ground.

She smiled at herself. I'm still young. Of course, it is the rest, the good food, the good clothes. She did not add even in her thoughts, that it was also something else that flushed her smooth cheek and brightened her clear hazel eyes, the knowledge that she possessed power over other people.

Susan, who had been confused and silly during dinner began to weep as soon as she was alone in the garden room with Mrs. Sacret. "You see how detestable Mrs. George Rue is?" she complained. "She only comes here to torment me! You heard how she sneered and showed me up! And Martin supported her!"

"Yes," agreed Mrs. Sacret. "And I don't understand how you endure it. Why don't you display some spirit? You have some of your own money—and you could make your husband give you what he invested for you—"

"I should never dare to ask him!" sobbed Susan.

"Instruct your lawyer, dear."

"Oh, that would mean a shocking quarrel!"

"As for that—isn't it a quarrel, now?"

"Oh, not like that would be! Martin doesn't scold so when his mother stays away and when he hasn't just seen her—"

Mrs. Sacret reflected that she did not know the whole of the story of Susan and her husband; they spent hours together in the large formal bedroom and dressing room upstairs—perhaps they were not entirely estranged, nor Susan entirely open with her friend. Perhaps there was something in her marriage that Susan wished to keep. To Mrs. Sacret's taste Martin did not seem worth contending for, she found him slightly repulsive in spite of his youth and good looks that accorded so unpleasantly with his nervous nagging and intense concern with his health, a habit formed and encouraged by his possessive, ignorant mother. She was always able to get hold of him, reflected Mrs. Sacret, by fussing over his chest or his headaches—she made a coward of him for her own ends.

"I wish I had had children," sighed Susan, pulling the long bell rope.

Mrs. Sacret rallied to this new topic that Susan had never touched on before.

"I am glad I did not," she replied. "The responsibility would have been too great. They might have inherited Frederick's poor constitution. The Lord knows best."

"Oh, dear, we both married invalids!" exclaimed Susan, wiping her eyes on her long lace handkerchief.

"I don't think Mr. Rue is an invalid, he has been cosseted by his mother; he doesn't take any exercise, either, and then, those medicines he makes up himself—"

"I'm sure you are right," murmured Susan. "What can I do? I have no influence, and, as you say, dear, his mother encourages him in all his whims."

"You had him alone in Florence. I wonder you persuaded him to go abroad."

"I didn't. He thought the climate would be good for his chest. We had the dullest time! Martin sat on the veranda all day."

"He should have been cured."

"No—he caught a chill, the sun drops suddenly and the nights are bitter; really our room was like a vault at night and only a pan of charcoal with which to heat it."

The maid entered and Susan ordered a bottle of sherry and some glasses to be brought.

Mrs. Sacret turned to her own affairs.

"I have an applicant for my little house, Susan. I told you I put a card in the window? I found a letter on the mat, when I went there yesterday. From one Mark Bellis, a painter. I wrote to make an appointment with him."

"I hope that means you are staying here indefinitely, dear."

"Why, no. I thought I would let the house for three months, then I shall have rested and be able to go back. I can't afford to allow it to remain empty."

"I wish you would permit me to give you—a—stipend," said Susan hurriedly and timidly.

"You pay for my clothes, dear."

"But—pocket money—"

"No. I could not. I have no expenses. I don't even pay anyone to look after the house. I do that myself. I have sufficient money. I'm here to help you, Susan. Not to make a profit for myself. I've to pay poor Frederick's doctor's account."

Susan glanced at her swiftly.

"Have you burned the letters, Olivia?"

The servant brought in the sherry and two glasses. Mrs. Sacret waited until she had gone before replying.

"I had forgotten all about them, Susan. They are so unimportant."

"Yes, of course. Where do you keep them?"

"I believe they are in the bottom of my little trinket box," said Mrs. Sacret carelessly. "With some other dear souvenirs. Really I shall dislike to destroy your handwriting, reminding me of those happy days."

She believed that she spoke sincerely, and she looked in a kindly fashion at Susan. But behind the kindness was curiosity. Susan drank two glasses of sherry in silence and her friend bent over her gossamer needlework.

Martin Rue entered awkwardly on the privacy of the two quiet women, seated daintily in their satin and gilt chairs in the rosy glow of the silver lamp. He glanced at once toward the sherry bottle.

"You drank enough at dinner, Sue," he rebuked abruptly. "A pint of red wine, and more than enough sherry for a lady—and why two glasses? Mrs. Sacret always says she doesn't drink alcohol."

"Oh, but tonight I thought I would like a glass," smiled Mrs. Sacret coolly. "I often do—though I refuse it at table—drink a little sherry here with Susan. Do you object, Mr. Rue? Is the wine measured out?"

"I like to keep a check on it," he replied with hostility. "The weekly expenses are very heavy."

"I pay my own wine bills, Martin," whispered Susan, looking away from him. "You know that I have to have some to keep up my strength."

"For what, pray?" he interrupted rudely. "And I wish you would not order wine—nasty stuff from the stores, fit only for bad cooking."

"You always lock up yours," retorted Susan, flushing. "And please don't scold me so often, in front of Olivia, too."

"Oh, Madam here knows all your secrets, of course!" exclaimed Mr. Rue with temper. "My mother says—"

Mrs. Sacret swiftly interrupted.

"Does she, sir? Neither of us wish to hear what she says, do we, Susan?"

Emboldened by this defiance, Susan gulped her third glass of sherry and agreed. "No, we really don't. We are sick and tired of your mother, Martin."

"You dare to tell me that—with this—friend—of yours abetting you?"

Mr. Rue turned with a vulgar politeness to Mrs. Sacret. "Madam, I don't consider you a good influence on my wife. My mother supports me in asking that you bring your visit, your very long visit, to an end."

"I shall leave when Susan desires me to do so, Mr. Rue." Mrs. Sacret had no difficulty in maintaining her composure; she felt fully justified in what she did and not in the least afraid of this bullying man. "I am protecting poor Susan from these two disagreeable people," she told herself, as if she were two entities, one of which dictated to and advised the other. "It must be God's wish I should do so."

"Yes, it is my house as well as yours," declared Susan with forceful feebleness. "And I'm sure that Olivia is the only company and the only comfort I get. Why do you want her to go?" she added tearfully.

"Yes, why, Mr. Rue?" Olivia Sacret covered up this weakness on her friend's part. "I never interfere with you and I cost you nothing."

"That's as may be," he rejoined, with a full stare at her costly clothes, "but I like my house to myself."

The missionary's widow had some satisfaction in noting the crude defects in her opponent. She had met his type, considerably softened by austere training, in her chapel work. A mother's darling, a school bully, idle, stupid and vain, mean and ostentatious. He married Susan for her money without caring for her in the least, she thought. And now he would like to return to Blackheath and be pampered by that doting old woman again.

Her fingers hurried over her needlework with delicate precision and an implied rebuke at idleness, while the unhappy couple remained sunk in a sullen silence. Susan drooped in her chair, staring from reddened eyes at the two stained glasses from both of which she had drunk. Her husband stood gloomily by the hearth, his hands in his pockets, his dark clothes out of place in the frivolous dainty room and the pink lamplight.