RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

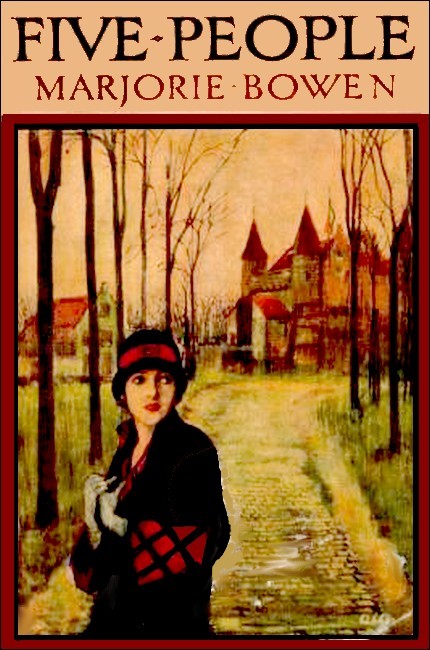

Dust Jacket of "Five People,"

Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1929

Cover of "Five People,"

Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1929

THIS is the third modern novel from Miss Marjorie Bowen and her work in modern writing has certainly been more powerful and more vivid than ever her long series of historical romances. Five People is a book of remarkable psychological insight and its plot is intricate and simple at once, as is the way of nature itself, the basis of all that truth to life which it is the novelist's business to attain. Here is a book stronger in many aspects than anything its finely imaginitive writer has hitherto written.

SHE fastened a thin bracelet of gold silk rosebuds round her wrist and thought: "How happy I am. How happy I have always been."

And a light fear shadowed this reflection: "Is it possible always to be so happy?"

She smiled at this fear; of course she would always be happy, because this happiness was the result not only of her circumstances, but of her disposition; she gave and received light to and from everything about her; nothing unkind had ever pierced the radiance of her personality.

Her smile dimpled as she studied the childish ornament she had fastened gaily round the fair wrist she so innocently admired; she sat looking down at her curved hand lying at ease on her satin knee.

The scene was a Paris flat, a choice and secret apartment concealed in the graceful and melancholy garden of the sombre and despoiled building of one of those ancient convents still standing among the network of modern activities adrift from their time and purpose, not far from the Rue de Sèvres, yet defended by several obscure and lonely streets from the noise and vitality of the modern thoroughfares.

This apartment that Helen St. Luc had occupied for ten years had been that part of the convent that had formerly been set apart for the use of great ladies temporarily retired from the world, or permanently forced into a secular retreat dignified by the approximity of sanctity.

These stately rooms, lofty mannered and shadowed half the year by the tall trees in the deserted garden, had housed many a noble dame whose stately retreat from temptations that no longer tempted had earned her a holy reputation in her old age, many a wit and belle whose later years here had effaced a dubious and splendid youth.

People said it was a queer place, inconvenient and out of the way, for a woman like Helen St. Luc to live in. Gloomy too, especially for a woman living alone, for the centre of the building was only occupied during the day, as a tapestry and embroidery school, and the other wing was merely used as a storehouse by an antique dealer.

Under Madame St. Luc's flat lived the concierge and his family; these were her sole company in the ancient convent of Ste. Angelique. She loved the queer place and had always been wealthy enough to do as she pleased; she was not there very much, for her life, her interests and her friends were all cosmopolitan; but she never stayed anywhere else when she was in Paris, and was always, she declared, happier here than in any other part of the world she knew.

It was an evening of full summer. Helen St. Luc was seldom in Paris in the summer; she went to her bedroom window and gazed out into the shadow of the lime trees from which the green-gold flowers and fruit drooped in profusion. These trees were as high as the building; between the pale transparent leaves that the last light transmuted into the colour of amber, Helen could glimpse the garden, always deserted; the sweeps of grass, the neglected parterres, the overgrown box, the old bushes of roses and geraniums, the little painted summer-house where the nuns had sat and sewed; the mossy cracked basin of the dry stone fountain.

In the faint jade-green sky that arched over Paris hung the new moon, a vivid crescent in the heavens still pulsating with the withdrawing light of the sun.

Helen drew her silver brocade curtains further apart, so that the scent of the lime blossoms and the hesitating twilight came full into the tenderly lit room; Helen used candles of yellowish scented wax. As she stood so, taken with a curious little sense of uncertainty, she frowned slightly with the emotional woman's effort logically to pursue a thought to a clear conclusion, usually a fruitless effort.

She was the daughter of a middle-class Englishman and a Frenchwoman of no family and the widow of a Provençal perfume manufacturer of mean origin, but wealth and some chance trick of nature had given her that grace, that allure, that air of fragility and delicacy, the exquisite lines and poise associated with, but not always the result of, pure patrician blood.

Madame St. Luc was pale, of medium colouring, with uncommonly large grey eyes and a mobile mouth, rather wide and constantly trembling into a smile, her features were of ordinary feminine prettiness; it was her carriage, her movements, her hands and arms, her lovely feet, that made her beautiful; if she had had to jostle along with the crowd she might all her life have passed unnoticed, but placed, adorned, set off with every advantage, no person of taste could have overlooked her uncommon grace. Thirty-three years old, she had never shed a tear save out of gentle compassion for some stranger, and for one personal grief, her father's death; brought up as the only child of a widowed father, she had been completely happy, married at twenty-three to an elderly man she did not love, she had still been completely happy. When he had died she had not been callously glad to be rid of a burden; it had been a sincere sorrow.

With deep tenderness the kind old man had kissed her "Good-bye."

"Thank you for seven years of happiness," he had said. "And now you must marry Louis Van Quellin."

That was three years ago, and Helen had not yet married Louis Van Quellin.

She owed a deep respect to the memory of Etienne St. Luc. She did not know the exact nature of her feelings towards Louis Van Quellin.

Some day she would marry him, of course, for he was already part of her life, but she felt no deep urge to do so; her present existence was very pleasant and hers was a nature to be long satisfied with a delicate and distant devotion. Nor had he pressed her, nor intruded on the delectable ground of their tacit understanding; he, too, was fastidious and fine with a certain added melancholy that she entirely lacked.

He was a man of peculiar character, of too many gifts, too much money, and one overwhelming obsession, rooted in an extravagant remorse.

This obsession was a sick girl, his half-sister, whose affliction was the one shadow over the brightness of Helen, who was so warmly piteous towards Cornelia; she loved the poor, ineffective cripple creature, really loved her, and had often thought:

"I should not like to take Louis away from her until she is better. No, not even by a little."

And she persuaded herself that this was why she had so constantly evaded the moment of a definite promise to Louis; she would have liked, before there was any precise talk of marriage, Cornelia to be cured.

There was always talk of her cure, first this treatment, then that; first one doctor, then another; hope was never dismissed, never allowed out of sight...Superb Helen left her bedroom and went into the salon that overlooked the courtyard by two lofty windows the entire height of the walls, which were hung with faded tapestry of faint lavender, cinnamon and rose hues, where heraldic beasts upheld fantastic shields on close packed fields of flowers.

Every object in the room was lovely and costly; the candle-light picked out from pools of shadow the acacia wood furniture, the chairs covered with white satin Chinese stitchery, the long wreaths of carved cedar wood fruit above the pelmets of the window and the slender mantelpiece, the puce coloured and saffron coloured crystal vases holding tuberoses, lilies and clove carnations, and the long straight yellow silk sofa near the gilt work-table and gilt bookcase where Helen usually sat.

When she entered this room she found Louis Van Quellin standing by the open window, through which the last twilight flowed to mingle with the golden flush of the candle radiance. She knew him so well that she could tell at once, from the very way he stood, that he was depressed. And his depression could only mean the one thing. Cornelia was worse, or, at least, not so well.

She asked before he had time to speak:

"Shall I go and sit with Cornelia to-night?"

"No. Why? She has a great deal of company. Even too much." It was as if he defended himself. "She is never alone."

"Of course. But I do not like to take you away from her—even for an evening, when she is not well."

"I did not say she was not well," he smiled. "You guessed that."

"Well, yes." She seated herself on the yellow sofa, the folds of her dress, which were stiff, of a ribbed silk in a dark petunia colour, made a flow of darkness in the blonde faded tints of the lovely gracious room.

"It is not so." She could see that he was denying his own conviction. "Cornelia is very well. Let us be alone together this evening."

They were due at the reception of a famous artist where fêtes en plein air were at present so fashionable, but Helen said at once:

"Shall we not go? Shall we stay here?"

"If that would please you? I like your old garden better than the park of M. de Guerin."

"Of course it pleases me. We will have coffee here and then go out."

"Everything pleases you, doesn't it?"

He smiled tenderly at her docility, her desire, so delicate and fine, to share her gaiety of spirits.

She considered him a little before she answered; this man, whose full name was Louis Van Quellin Van Paradys, came, as she came, of mixed ancestry; his mother English, his father Flemish, of an ancient and rather remarkable family, whose estate had been at one time of such princely beauty as to gain the name Paradys, which hereafter had remained to the Van Quellins, together with considerable wealth gained as bankers and spent as nobles.

Louis Van Quellin was a celebrated collector of all forms of rather exotic, over-refined and subtle objects of beauty; some people said that he would marry Helen St. Luc only to add another choice piece to his already world-famous collection.

He was now in his thirty-fifth year, very quiet in manner and appearance, with an aquiline face and close hair, slightly dark reddish; his eyes were rather too light, and this pale clear grey hawk's look from the dark face was discomposing to most people, for the expression was often both cold and lonely and always proud and keen, so that the finished courtesy of his manner seemed discounted as a mere surface pleasantness; his intimates called him un grand homme manqué, he was not idle, but seemed to disdain ambition.

Helen St. Luc was now, after her scrutiny, moved to confide in him, not so much for the sake of the confession, but to rouse him from one of those fits of inner abstraction which she knew and faintly disliked in him, as she faintly disliked anything that was not absolutely candid and clear.

"Do you know, just before you came, I was looking out on the lime trees—and I had a moment of fear—just a little stir of fear—that I was too happy."

"Polycrates and the ring," he quoted, smiling, taking her very lightly.

"Yes! But that is an unfortunate illustration, isn't it? Polycrates sacrificed his favourite ring and it was brought back to him—and afterwards he had all manner of misery."

"Sacrifice something that cannot be brought back," he suggested with a hint of mockery. "Polycrates threw his ring into the sea and a fish swallowed it—you could make a more definite offer to the gods—sometimes there is no possibility even of a fish."

Helen St. Luc leaned towards him, trying to understand his mood.

"What? I would like to sacrifice something—tell me what."

"Seriously? Now what could threaten you?"

"I don't know. Polycrates didn't, did he?"

"All a clear horizon, isn't it?"

"Yes—everything has been so happy for me. I came out of happiness, my father had a smooth, easy life. I've been too cherished, too comfortable, and ahead, well, as you say, Louis, what could happen to me?" She finished with a tender coquetry.

"Nothing. You haven't an enemy in the world."

"Nor a relation," she laughed. "Yes, it is all dangerously bright. Quick, what do we sacrifice?"

She rose and looked mischievously round the room, yet really watching him.

Louis Van Quellin took up something she had said.

"Have you really no relation, Helen?" He had always seen her surrounded by so many friends, she was so popular, so much of the world, that this thought of her inner isolation seemed strange.

She shook her fine little head.

"No—but yes! A cousin, I do believe. I had an uncle," she reflected, "who went quite definitely to the bad, like people used to in those days. You know, Louis, the absolute black sheep who was so shameful you could not speak of him and seems so old-fashioned now. My father hardly mentioned him. He died long ago, before I was born, but there was a daughter—my cousin, of course."

"She would be hardly likely to affect you," said Van Quellin, without much interest in what she said, but absorbed in watching the tender animation of her delicious face.

"No—she may be dead too, for all I have heard—I don't know where she is, if she is alive. I believe they went to Australia. My father was always helping them."

"I wonder why you have thought of her to-night?"

"Oh, yes, it is strange—but I do sometimes think of it. My poor uncle was an engineer too, and with my father at first. He left the firm in some awful disgrace just before father's big success—it seems sad." She spoke earnestly. Helen could be earnest in a second when thinking of other people's griefs.

Van Quellin lightly mocked her sudden interest in this dead trouble; to tease her he turned and picked up, as the first object that came to his hand, a long graceful vase in pink alabaster. "What of your sacrifice to the gods? This vase I brought you from Greece."

"Ah, Louis, I value that!"

"Isn't that what you throw away? What you value?"

She laughed at the discovery of her insincerity.

"Of course. Well, I will sacrifice it. I am too happy."

Van Quellin was surprised at the seriousness obvious under the raillery of her manner; he fancied that she was slightly, unaccountably nervous, yet he had never known Helen nervous, but he had always believed that the most sensible of women were at heart superstitious, and that it was kind to humour them in their superstitions.

"Very well," he said, "I will throw the vase from the window, and when you hear it crash below you will know that your sacrifice has been accepted by the gods—"

"My beautiful vase!" cried Helen a little breathlessly.

With mock drama Louis Van Quellin held the lovely rosy shape up and out of the open window that gave directly on to the quiet shadowed courtyard, empty save for Van Quellin's car near the old iron gates.

"I pray the high gods to accept this offering from one afraid of her happiness," he cried.

Helen's pearly laugh followed his words; she came close beside him and her silks rustled over her hastened breathing as she pressed into the window space.

Van Quellin dropped the vase.

"I didn't hear the crash," whispered Helen with an excited shiver.

They leant out but could see nothing in the soft gloom save the dark shape of the empty building, the sky, now a limpid violet, and the sinking crescent of the new moon; below was a mere well of shadow, with the pompous twists of the gate showing in the dimmed headlights of the car in which Van Quellin had driven, from his place at Marli.

"I will go down and see," smiled Van Quellin.

While he was gone, Helen's maid brought in her cloak.

Helen ordered coffee; she was rather vexed at the loss of the vase, yet secretly pleased that she had really carried out her unaccountable and, of course, foolish whim.

She put on her cloak and went to the window again; the tranquil harmony of the evening was exquisite with pulsations of dying light, with fading drifts of lime perfume, with the ripple of unseen trees coming and going on the fragile trembling of the furtive breeze.

Van Quellin returned; he held the intact alabaster vase.

"It fell on a pile of sacking," he explained, "some unwrappings from the tapestry people's goods. You see, Helen, we have been saved from the consequences of our own foolishness."

He put the vase back in its place; she saw that the incident meant nothing to him, and dutifully she laughed it off as a jest that had been carried far enough.

"How lucky—I am glad to have my vase back," she answered. "One cannot often be foolish with impunity."

But she glanced at the rejected offering with a suspicion of dread; Van Quellin had been right in thinking her a superstitious woman. The invisible menace to her flawless content seemed to have become suddenly definite. This was perhaps because the happiness of which she had been frightened was really established on nothing more stable than money and her own disposition; she had nothing else.

Her father had been what the world she now moved in but did not belong to, and never would belong to, still called a self-made man; he had been a very successful engineer, wealthy, kind, prudent, but reserved and solitary, not a morose or melancholy man, but one in whom the natural gaiety seemed to have been quenched; he had made few friends, and though he had loved Helen deeply, she had not seen very much of him; in the pleasant life he arranged for her, with a certain anxiety, he had himself taken little part; it had been with a certain anxiety too that he had insisted on her marriage to a man much older than herself, but a kind man, a reliable man; it was as if Mark Fermor had wished to consolidate his daughter's position; he was not strong and he continually told her that she had no one but himself; her mother was long since dead, and her mother's people were negative; insignificant and obscure French provincials; even in the tender regard of his daughter Mark Fermor's marriage had been vague and ineffective; she had never thought that grief for her mother had made of her father a quiet, slightly depressed man.

Soon after Mark Fermor had arranged this sensible successful marriage for his cherished daughter, he died, rather suddenly.

That had been Helen's one grief; yet not as deep a grief as it might have been, for her father had kept her so apart from his own simple reserved life that she had never been able to love him as it was in her nature to love; yet she knew how he loved her, and the pang of the unexpected parting had been poignant enough.

Mark Fermor had been away for a few days and returned to his London home a sick man; he had caught a chill that ended in sharp bronchitis, and Helen had hurried from France to find him dead before her arrival.

He left her a considerable fortune; he had founded a firm success and made a good deal of money by the invention, early in his career, of a new brake system, and his business had been one of steady and increasing prosperity.

Yet he left her nothing but the money; she never thought of, yet sometimes faintly sensed, the fact that she was really very much isolated, a waif and stray among the kind, pleasant people who caressed her in so amiable a fashion.

The death of her husband had further emphasised her position; once again there was nothing left her but money, and, by her own wish, not much of this. Etienne St. Luc had provided generously for his own people, none of whom was well off, for he, like Mark Fermor, was a self-made man.

Helen might have known that she was lonely had it not been for Louis Van Quellin; this man, her superior in everything but character, had something grand about him that gave a splendour to all his actions.

During her husband's lifetime his acquaintance had been the colour of her days, and since he had been her declared lover she had known this happiness of which she was afraid; yet Helen, who had never realised passion, was not sure that she loved this man any more than she had loved her father or Etienne St. Luc.

Possibly it was this uncertainty that was like the shadow behind the radiance of her delight in life; perhaps the shadow came from her sense of being indefinably alien to her world, even a little alien to Louis Van Quellin; she knew that he loved her almost with reluctance; that he unconsciously condescended, that he was moody, melancholy, obsessed by an invalid, that it was despite himself that he was tempted by her, Helen's gaiety, candour and simplicity.

Afraid of happiness she had said; it was really of Louis Van Quellin that she was afraid; such frankness as hers is always afraid of what it does not understand.

While she drank her coffee and listened to him talking, with a sort of reluctant interest, of his recent treasures purchased at a sale in Brussels, she was looking at an engraving by Guidon that hung beside the fireplace.

It was the portrait of a man in rigid modern dress, a man with a humorous, cheerful face, from which the humour and the cheerfulness seemed to have been sharply withdrawn—a portrait of her father, Mark Fermor.

HELEN received her letters on the eve of her departure for Marli, where the Van Quellins had an elegant little château that had lately pleased the errant whim, the sick mood of Cornelia Van Quellin.

Neither Madame St. Luc nor the Van Quellins followed the conventional conceits of fashion; despite the immense number of their acquaintances and a certain conspicuousness in their position they lived rather apart from other people; and Helen, since her husband's death, had discontinued much of her social life; she, besides, had not much but the paternal fortune; ample, of course, but not sufficient to leave much margin after the ordinary requirements of a wealthy, generous woman had been fulfilled.

During her widowhood she had kept up the flat in London, a flat in Paris, and not lived very much at either, but mostly in quiet and exquisite hotels or with some of her charming and affectionate friends.

She was going now to stay for a few days with the Montmorins, always the friends of Louis Van Quellin and now her friends.

As she motored out of Paris she read the letters her maid had handed her. She had taken them gaily with a sense of pleasure in seeing several familiar writings.

Reading these light agreeable letters occupied her until the car was out on the long straight French road so uniform and exact to a pattern of efficiency, and a cheap envelope addressed in an illiterate hand lay neglected on her lap.

Two of the women who wrote to her asked her when she was going to marry Louis Van Quellin; Helen smiled, she had guessed that she was wearing out the patience of her friends by this prolonged dalliance; and she wondered, as she read these two letters, one after the other, asking the same thing, quite why it was that she did still hesitate, quite why she still kept Van Quellin at a distance, very gaily and tenderly, yet still at a distance.

She thought that it was because of Cornelia; she had always been so sensitive about coming between brother and sister, and from month to month had beckoned a beguiling hope that the girl might suddenly be cured.

And yet it was a little something besides that; something more personal, something that Helen could not quite label, perhaps a little uncertainty as to Louis Van Quellin, perhaps, though this sounded absurd, an indefinite, unacknowledged fear of putting herself wholly and for ever in his power.

Still distracted by this subtle reflection, Helen picked up the remaining letter; she received a certain amount of appeals for charities, and even begging letters, and she thought this was one of them, and opened it with reluctance and a distaste for the vulgar envelope and common handwriting at once sprawling and cramped.

In the shaded electric light that filled the pearl-tinted interior of the car Helen St. Luc read:

My dear Cousin Helen,

I don't know if you you will get this, I don't know your address, I expect that you have hardly heard of me. I am your Uncle Paul's daughter. My mother is blind and crippled and we live together here. I don't suppose you ever come to a place like this. If you ever did it would be nice to see you, as I have no other relations. I often see your picture in the paper. Perhaps if you get this you might let me know.

Your affectionate cousin,

Pauline Fermor.

Madame St. Luc was deeply shocked; she forgot her other

correspondents and even Louis Van Quellin as she turned over and

over this wretched letter.

An inevitable flush of humiliation coloured her gentle face at his claim of kinship from someone whom she felt to be degraded; absolutely without vanity or arrogance, Helen yet detested, unconsciously and instinctively, all that was vulgar, and brought up as she had been, living as she lived, it could not fail to come as a stab that she was herself related to vulgarity and commonness.

And instantly after this sensation of disgust came, wonder; she stared at the address printed carefully in irregular letters at the top of the letter.

In England? So near to London? Why, then, this silence of a lifetime, why had her father, on the very rare occasions when he had mentioned his brother's family, spoken as if they had gone to Australia—and the mother blind and crippled!

How old would this Pauline be?—her own age or a little younger, and quite illiterate—a council school education, if that—how did she live? What did she do? No one who could write that letter could be much above a servant, and what did she want—why had she suddenly written?

Helen revolved these questions in rapid dismay, but it never occurred to her that she could ignore the letter or fail to be of the utmost possible service to the writer; yet she was both bewildered and aghast at the task, the problem, and, as it seemed to her, the menace, suddenly confronting her; why a menace?

There was nothing save what was silly and pitiful in this letter; yet Helen felt that the sheer fact of the existence of this cousin was a threat to her own happiness; she knew dim stirrings of remorse, a doubt as to the past, a wonder as to the events that had made such a cleavage between two women of the same age, the same blood, who were the sole survivors of their family.

"I must ask Louis," thought Helen, "exactly what I ought to do."

And as she thought of Louis Van Quellin she thought of her pink alabaster vase that had been so strangely returned to her; she laughed, though a little ruefully, at herself; but she could not resist connecting this portent with the letter from this cousin Pauline. She observed nothing more of the road, and it was absently that she noticed the car sweep through the wide gates of the Château Montmorin and along the smooth gravel drive; the rich summer air was suddenly bitter sweet with the perfume of box hedges, of lime blossoms and of privet blooming in the star-lit darkness; the long, low gracious windows of the château showed the opal and amber light of hidden lamps and a flare of crimson damask roses in the open casements between the looped back curtains of pale gold silk; through these wide set windows came the intermittent half muted playing of a violin, very exquisite and precise.

As Helen descended from her car Madame de Montmorin was on the terrace steps to welcome her; Helen divined a sort of compassion in this lady's kind greeting.

"You are rather late, my dear child—perhaps you are not too tired to go over at once to Geaudesert? Cornelia"—this a little anxiously—"is urgently asking for you—"

"I will go at once," answered Helen in a slightly absorbed fashion; her mind could not immediately be freed from the thoughts evoked by Pauline's letter, and she was used to Cornelia's moods, depressions and relapses.

"Is Louis there?" she added.

And Madame de Montmorin, still holding her warmly by the shoulders, kissed her again and said:

"Why don't you marry Louis; wouldn't it make things easier all round?"

"Jeanne," replied Helen seriously, "I am afraid things are too easy—for me at least, as they are. Do you know that I was so scared at being too fortunate that I tried to sacrifice my pink alabaster vase—you know, the ring of Polycrstes!"

"You silly child!" The elder woman caressed the soft tender face that looked so audaciously charming and yet so appealingly gentle; there was a peculiarly disarming quality about Helen's beauty; she had never yet evoked jealousy.

"Louis threw it out of my window," she added with a little grimace, "and it fell on some sacking and didn't break. What do you think of that, Jeanne?"

"That you were luckier than you deserved to be—really, Helen, your superstitions are shameless! Now will you go over and see Cornelia, and when she is quieted, Louis can bring you back here to supper—"

"Louis will not like to leave her—"

"My dear," said Madame de Montmorin calmly and firmly, "you must not allow Cornelia to become an obsession. I was telling Louis so to-day; it will be three lives spoiled instead of one if you are not careful."

"That sounds rather brutal," answered Helen wistfully; her emotions always ruled her mind, and her naturally good judgment was usually obscured by sentiment.

"You need saving from yourself," remarked Madame de Montmorin affectionately.

M. de Montmorin had put down his violin and come on to the steps to greet his guest; he brought with him a large gilt basket of peaches adorned with the pure blooms and glossy petals of rose coloured camellias; one of the perpetual offerings that went from Château Montmorin to Beaudesert.

During the few moments' drive Helen was uneasily thinking of Pauline's letter; she felt a rather subtle shame in showing it to Van Quellin; not for herself, but for this unknown cousin; it seemed like an exposure, like an affront, to show that letter to such a man as Louis Van Quellin.

Yet she was too entirely dependent on him to be really able to act without his advice, besides being, by nature and training, the type of woman always to refer all problems to a man.

Beaudesert was a small, elegant, ancient building, something between a toy château and a toy farm. It stood sheltered by a bouquet of tall trees in a gracious and careless little park, and close to the house was a pond, darkened by weeping willows, where the still artificial water, the drooping boughs and the pure whiteness of the swans against the tourelles of the house, were like a scene from an eighteenth-century pastoral; Cornelia's room looked on to this delicate, formal and melancholy view, and Helen found her, late as it was, sitting by the long open window looking out on to the stars and the willow.

Cornelia Van Quellin was eighteen years old and had something of the sad beauty of anaemia, the pallid loveliness of the disease that used to be masked under the gentle word "decline"; her Irish mother had died of tuberculosis at twenty-four, having captured the fastidious taste of her husband by precisely this unearthly fragility, this exquisite and fatal bloom.

All her life Cornelia had been ill, and as well as the symptoms of hereditary weakness, she was afflicted with a definite injury to the spine, the effect, as was generally believed, yet sometimes doubted, of a fall. Louis Van Quellin, a boy of sixteen, had taken the baby, his step-sister, tossed her up and dropped her, with the consequence of this disablement of body for her and a disease of the soul for him; several doctors had assured him that if this poor child had been healthy, the injury would have healed easily enough and that her present state of health was due to her disease, not to her injury; the remorse was ineffaceable; years of lavish care, of prodigal expenditure, had not balanced the boyish carelessness in Louis Van Quellin's sensitive mind, and he evinced for this pathetic child of his father's second marriage a devotion and a solicitude that touched the fantastic.

Cornelia did not, as so many chronic invalids do, possess any remarkable gifts of character or personality. Her spirit was as faint and ineffective as her body, her mind seemed as helpless as her limbs. She was gentle and affectionate and her own passion was the absorbing desire to be "cured"; from her couch, her chair, her carriage she frantically pursued the gleaming wings, the averted face of Hope.

Helen placed the basket of peaches on the table by the bed.

"I have just arrived, Cornelia. I came over at once. How beautiful your room looks, darling. M. de Montmorin sent you some of his peaches; see they are the same colour as the camellias—"

She lifted out two of the pure rosy blossoms and placed them on the girl's knee; Cornelia moved her head, heavy with fallen wreaths of glossy chestnut hair, on the cushions.

"I wanted to see you," she whispered, "and now you have come lam too tired to talk."

There was a nurse in the room, one of the two who were always with Cornelia, and Helen glanced at this woman apprehensively; surely the girl looked, even for her, very ill.

"Louis is on the balcony in the bedroom; don't you want to see him?" murmured Cornelia.

"Presently—when I have seen something of you—"

Helen sat on a low bergère by the invalid's sofa; she felt to-night, and for the first time, curiously unable to cope with the sick girl's melancholy; it must be, she thought, Pauline's letter like a weight on her spirits, usually so volatile.

This little room, which was circular, being in one of the tourelles, was entirely furnished in giltwood and orchid-tinted satin, and over-loaded with exotic flowers—carnation, jasmine, tuberose, verbena and roses, Cornelia's one definite taste; these stood on little shelves and brackets in crystal vases that they entirely hid, so that the sprays and cascades of blooms seemed to grow from the satin walls. Through the open inner door showed the palest lilac blue of the bedroom, the great uncurtained windows open on to the immaculate purity of the night, and a hanging lamp of such vivid glass that the light seemed to shine through a bed of tulips.

Cornelia wore a lace robe, a jacket of white fur and held spread over her knees a wrap of opal coloured velvet, on which the two red camellias showed with rich intensity; she had the long curved throat, the full red lips, the heavy eyes, the transparent carnation and the abundant reddish hair that is the beauty of decadence and sometimes even of imbecility.

Helen, so alert, so vivid, with her quick movements and changeful face, always flushing and smiling into animation, was a piquant, perhaps cruel contrast to the sick girl, as her quiet grey wrap and long swathed grey motoring veil were in contrast to the exaggerated luxury of the room.

Cornelia closed her eyes with an air of exhaustion, and Helen sat silent, looking out on to the pond and the willows faintly visible below.

She knew that Louis was standing on the light iron balcony of the inner room; she could see when she turned from where she sat, the long graceful line of his figure, and she knew also that he must be aware of her presence; from the fact that he remained on the balcony she guessed that he was in one of those strange moods when he seemed isolated in an impenetrable loneliness which her warmest affection was powerless to combat.

Helen, looking through the lamp-lit room at that motionless masculine figure, almost like a shadow, felt, for the first time during her relations with Louis Van Quellin, a tiny thrill of fear, an absurd fear, a grotesque fear—the fear of losing his love.

She had been always so sure of him that she had become almost indifferent to the value of this man as complete security and long use will breed a certain indifference even towards the most magnificent possessions.

Now, from this trivial fact that he had not come forward at once to greet her, she suddenly, in a chill clearness visualised a world without the love of Louis Van Quellin and found it intolerable.

If Cornelia had not been there she must have risen at once and gone to him; as it was it cost her an effort to remain placidly by the sick girl.

Cornelia looked up suddenly; the lustre of her large eyes, heightened by the wild rose flush on the pale cheek beneath had that over-luxuriant life that breeds death.

"I have something important to say," she whispered.

Helen endeavoured to dismiss all thoughts of Louis and to concentrate on Cornelia; this was more difficult as, for the first time, she found the exotic atmosphere of this sick room oppressive, the perfume of the masses of hothouse flowers too violent, and the unearthly beauty of the invalid girl too unnatural and painful; she would have liked to have escaped into the cool of the garden and sat alone under the willows that enclosed the pond, in the tranquil stillness of the murmuring evening.

"Something important, Cornelia?" She took one of the invalid's pallid damp hands in her firm fingers.

"Yes, I was afraid to speak to Louis—so I had to wait till you came and to-night you are late," complained Cornelia fretfully.

"Afraid to speak to Louis? But why?"

"He would not do what I wanted."

"But, Cornelia, he always does what you want."

Helen spoke very gently, but she was thinking of what Madame de Montmorin had said of Cornelia becoming an "obsession."

"He wouldn't allow this," replied Cornelia. "I know Louis—"

"What is it?" asked Helen; she had never known Louis flinch from any extravagance to gratify Cornelia.

"I wish to try a faith cure," said the girl most unexpectedly. "I was reading in the paper about a Mrs. Falaise, an American, who had the gift of healing—people are going to her from all over the world."

Helen was truly dismayed; she now agreed with Cornelia that this was the one thing that Louis would refuse his sister: Mrs. Falaise, whether sincere or not, had a flamboyant reputation and had more than once been in the courts as a witness at the inquests on her patients; yet that sparkling Hope they all pursued, might, to Cornelia, wear, for a space, even the aspect of a charlatan, and Helen could not endure to check this piteous enthusiasm.

"Mrs. Falaise?" she hesitated. "Perhaps there is something in her, Cornelia. Of course there is a great deal in a faith cure, but I think it is your own faith and the faith of those who love you—"

"But that hasn't cured me, has it?" interrupted the sick girl restlessly. "I don't really get stronger, Helen, it is all pretence that I do; every day I think—tomorrow—but to-morrow is just the same, and I'm grown up now. There is so much to learn. I want to dance, to play games, to drive a car—and I can't learn anything till I can walk, can I? I would like nice dresses too, not just these dressing-gown things, and oh, Helen! I would like the pain to stop!"

Her head drooped back on the pillows as if she was exhausted with so long a speech.

Helen thought that she would willingly give her anything, even the services of Mrs. Falaise.

Cornelia opened again her pathetic eyes, so unhealthily luminous behind the fringe of thick lashes.

"I get so tired of the pain, Helen, headaches and aches in my back and on my chest. I don't tell Louis about it, he gets so frantic, but it is there and I am so weary of lying down."

"But you are so much better this summer, all the doctors say so."

"I don't feel it—and even if I did, what is the use if I can't walk? I don't want to be better just lying on a sofa—I want to be like other girls."

Helen's heart contracted with anguish; "like other girls!" Could this ever be possible, whatever "cure" was effected? The very shape and look of Cornelia marked her out as one apart, dedicated her to disease and suffering, the commonplace joys she longed for could never be hers; at the very best she would always be languid, frail, ailing, only kept alive by all the resources of science and wealth.

Looking up into Helen's grieved face, the sick girl continued:

"And there is another thing. If I was well you would marry Louis at once, wouldn't you?"

Startled, Helen answered:

"You must not think of that, dear."

"But I know that you don't want to take him away from me."

"I could never do that," replied Helen warmly. "You will always be first with Louis."

"But that isn't right, is it?" asked Cornelia with amazing clearness of judgment. "I want to be well so that Louis doesn't have to care for me so much."

"Dear child," protested Helen, troubled, "you must not think of such things."

"But I do, I have so much time for thinking. Louis loves me—to make up, because he is so sorry. I want to set Louis free from that—I want someone to love me just for myself."

She pressed her handkerchief to her glazed lips and her eyes flashed through the crystal of tears.

"My darling, that will not be difficult." Helen had never seen so far into this wounded child's soul and she was confused and overwhelmed.

"Some people might think me pretty," continued Cornelia wistfully. "That is why I won't have my hair cut off, though it does make my head ache."

"You are lovely," said Helen softly. "Everyone thinks that, dear."

And in her romantic, sensitive and emotional mind she was thinking that surely it would be easy for some man to love Cornelia even as she was, to take over Louis's task of consoler and protector; Helen, though she knew that the idea would have been considered impossible, crazy and wrong, would willingly have seen Cornelia loved and even married; it was this isolation from all hope of the dearest relation in life that was thwarting the girl's chance of health; to Helen the role of Cornelia's lover did not seem impossible; but there was no such lover; the girl was dedicated to the nunnery of her sick chamber.

"Will you speak to Louis about Mrs. Falaise?" persisted Cornelia. "Tell him that I have set my mind on it—even the chance makes me feel happy—tell him that."

She was moving restlessly on her cushions, the pearly drops of weakness showed on the brow beneath the cherished crown of hair and the incredible scarlet of the lips were trembling.

"Of course I will speak, now, at once, if you like."

Cornelia pressed her hand, but did not answer; she was suddenly too exhausted to speak, and huddled together in her pillows, with closed eyes fell asleep at once. Helen crossed over to the nurse who sat near the bedroom entrance with the unobtrusive needlework.

"You heard what she said, nurse?" whispered Helen. "What do you think of it?"

The pleasant efficient woman rose.

"Of course there is nothing in it, Madame St. Luc."

"But if she believes there is, might not just that confidence do her some good?"

The nurse shook her sensible head.

"I'm afraid not. I've seen that sort of thing tried; you see, there's the reaction; perhaps these people work on them until they think they are better, there is a fearful lot of excitement and then a dreadful relapse. Miss Van Quellin," added the Englishwoman seriously, "couldn't stand anything like that—I'm sure any doctor would say so—and that is another difficulty you'd have. If you called in anyone like Mrs. Falaise, no doctor would go on with the case. I wouldn't care to nurse Miss Van Quellin myself, with anyone like that about," she finished firmly.

Helen was helpless before this combination of professional prejudice and sheer common sense.

She sighed. "I am sure that Mr. Van Quellin will not allow it," she answered, "but it is such a pity that she has set her heart on it."

"A great pity," agreed the nurse and went quickly across to her patient, while Helen entered the inner bedroom where Louis Van Quellin was still waiting on the low fronted balcony.

She had two troubles to bring him; Pauline's letter, which seemed so alien to this life, and this unfortunate business of Mrs. Falaise; that perfect happiness that had frightened her when she tried to sacrifice the vase was not hers to-night; in the light of the lamp, the bedroom showed large and pale in faint hues and sparse of furniture, to balance this the lamp gave a false rosiness; here were neither carpets, curtains nor flowers allowed, the two big windows stood perpetually open, and yet neither fresh air nor perfume could efface a faint clean odour of drugs.

At Helen's step in this room Louis Van Quellin turned and came in from the balcony; she knew at once that he had been waiting and listening, and she checked her advance with a queer sense of something formidable in her way. As she almost imperceptibly paused Louis Van Quellin came close to her and took her in his arms with a gesture that was, for him, impatient, yet sullen.

HELEN wanted to say: "I love you! I love you!" but she was taken by surprise and rather bewildered by his sudden intensity of feeling precisely when she had been, for the first time, slightly fearful of his perfect allegiance; so she was silent, and when he released her, clasped his arm, a little shaken.

And while she was framing some too-careful speech she saw that she had made a mistake by this silence, for he was instantly withdrawn into himself and became at once so coldly composed that it was impossible for her to refer to what he had just done—to his sudden clasp and impatient kiss.

Helen knew that she had allowed a notable moment to be rejected and a certain regret further quenched the lightness of her spirits; for a second she saw her long dalliance as a melancholy thing, and she had a queer consciousness of time, flowing away, steadily and swiftly, stealing with inexorable precision, day and night, all the joy of life and finally life itself.

"Come on to the balcony," said Louis. "It is so cool there, almost as if we were on the tree tops."

The bouquet of trees that sheltered Beaudesert did here encroach upon the bricks, and the green gold bunches of leaves of the maples and the erect red-stemmed leaves could be plucked from the end of the balcony, while from the other side was the view of the pond and the willows, the long trailing boughs now as still as the water beneath the summer stars.

Van Quellin stood so that the maple leaves brushed his shoulders and the luxuriant light of Cornelia's lamp was on him; the authoritative, aquiline face, slightly too narrow, looked neither kind nor gentle to-night, and the pale vivid eyes, that same clear uncommon crystal grey that Helen had actually seen in a captive hawk, were full of a haughty but none the less poignant loneliness, that both touched and frightened Helen. Leaning against the twisting iron scrolls of the balcony she told him what Cornelia had said about Mrs. Falaise.

Despite the sound advice of the experienced nurse, she finished:

"I think I should humour her, Louis, if I possibly could."

"I know," he answered, "that is what you do, humour people, isn't it?"

Helen felt a double meaning in his words, but would not notice this, nor did she look at him, but away into the chill peace of the night.

"I think Cornelia needs some—well, excitement—perhaps it is difficult to realize, Louis, the sheer boredom of her life—"

"Dr. Henriot thinks differently—he says that she is definitely stronger this summer and should be absolutely quiet."

"Very well for the body, Louis, but the mind!"

"Do you think that a woman like Mrs. Falaise could really do any good?"

Helen hesitated.

"I think if Cornelia believed—"

"It is impossible. I am really in the hands of Henriot. I couldn't of course suggest such a thing to him—and personally, I think it nonsense—"

"There seem to have been some wonderful cures," murmured Helen wistfully.

"Nervous and mental perhaps—but for organic disease! No, Helen, you must try to get the idea out of Cornelia's head. When," he added sharply, "does she see the papers? I try to keep them from her—"

"Oh, it was an article on faith healing in some very discreet periodical, and Mrs. Falaise was mentioned—"

"A pity," he remarked. "Anything of that kind is out of the question, Helen."

The words were like a courteous rebuke, and Helen felt herself put gently away from and forbidden to pursue the subject. She glanced up quickly at his face, the clean line of cheek and chin, the too firm set of the full lips and those clear intently gazing eyes; she had of course always known that force and power underlay this man's grace and careless accomplishment, but now, she thought, reluctantly, that he might be perilous, might dominate too utterly, taking her away from much that was dear, much that was essential to her life; even as now, when he was quietly intolerant of her aching desire to champion Cornelia's whims.

A breeze that seemed to have come from very far away, and leaped upon them suddenly, rustled the tree tops behind Van Quellin, and that was all the sound between them.

She was thinking:

"He is displeased with me—how often he will be displeased with me!"

And he:

"If she really only loved me! But she is in love with the whole world, not with me!"

It was easy, he was brooding, for people to laugh and sneer at love, to treat it as an episode or a diversion, but to love a woman like Helen was a tremendous thing, a thing you could hardly overvalue. Why, to love her was to have all the current of your days changed, it meant living deliciously, passing from one exquisite emotion to another, being tormented by her alluring absurdities, soothed by her delightful sympathy, stirred by the vivacity of her gaiety. Ah, you couldn't put it into words, she made music of the commonplace harmonies of every day, she gave to the most ordinary sky the colours of the rainbow; and she did not really love him, she was not really his; she might think she did and was, but he knew better—and this semblance of love was to him like a loaned treasure that might any moment be withdrawn.

Helen was speaking again:

"I've got something else to speak to you about, Louis—my own little bother this time; my cousin has written to me, rather a dismal sort of letter, and I don't quite know what to do about it."

"Your cousin? You were speaking of her the other day. And now she has written to you!"

"Yes, I suppose she must have been writing at the very time I was talking of her—a sort of telepathy, wasn't it? The night I tried to sacrifice the alabaster vase!"

Helen spoke rapidly, nervously, and Louis Van Quellin was moved to say (so well he knew her):

"Was there anything unpleasant in the letter?"

"Unpleasant? No, but it came as a slight shock—difficult to explain, but she was so vague to me, lost in the void, and then suddenly she was there."

"I know. What does she say?"

"Nothing really, it is just to bring herself to my notice; she must, poor thing, want us to be friends."

"How did she get at you?"

"Through a newspaper she saw, I suppose, some snapshot; anyhow they forwarded it to Paris—here it is."

She gave him the letter, taking it from the silk satchel on her arm, and he turned so that the rosy-toned light of Cornelia's lamp fell over the sheet.

When he had read it he handed it back to Helen and said:

"There is a great deal behind that letter."

"You mean?" Helen was puzzled, still a little anxious.

"I think the writer intends a very great deal more than she says—she wants you to do something for her, this letter is a kind of speculation on your character, she just risks on the chance that you are kind, generous."

Helen defended the unknown relative.

"I don't see why she shouldn't want to know me; that is quite natural, isn't it?"

"But why," asked Louis instantly, "did she keep silence so long?"

Helen had no suggestion to offer; the past was as shadowy to her as it was to Pauline Fermor, only when to one woman these shadows were dark and dreadful, to the other they were bright and lovely.

Louis Van Quellin answered his own question.

"I expect that it was the mother—some hostile influence there, holding the daughter back—"

"Hostile tome?" asked Helen, surprised. "But why? Father was very good to her mother—to all of them."

"There seems to have been some very decided estrangement—you don't know anything about it?"

"No—only what I told you. I really hardly knew of the existence of this cousin, certainly not that she was living in England—"

"And the mother blind, and evidently things going hard with them—there is something curious in the story."

He reflected a little; he was taking the matter more seriously than Helen had thought he would; she had rather hoped that he would make light of Pauline Fermor.

"What are you going to do?" he asked imperiously.

Thus directly challenged Helen fell into confusion, not because she did not know her own mind, but because she was afraid that Louis Van Quellin would not approve her decision.

"What would you suggest I did?" she asked with a pretty appeal in her voice.

"Have nothing to do with it," he answered promptly. "Don't answer that letter."

"That is impossible," said Helen quickly.

"Well then in the briefest way possible, and leave her alone; if you don't deliberately seek her out, you are not likely to meet."

"I don't know why you advise that, Louis."

"Just ordinary sense," he replied tolerantly. "This woman can have nothing in common with you. I don't like her letter nor her handwriting."

"You are very arrogant, Louis. She is, well, illiterate," replied Helen gently. "I suppose she was never educated and she must be very poor. I daresay she earns her living at some hard work—"

"I know, but I didn't mean that, only that letter is too simple, it isn't genuine—it's crafty; if she was absolutely sincere she wouldn't write like that. An ignorant person is usually very elaborate and long-winded—she would explain why she had never written before, go into the past—"

"Why should she know more of it than I do?" interrupted Helen.

"She knows some version of it—her mother has told her something, people who are fortunate don't trouble why they became so, those who aren't try to blame something—this woman born your equal, and sunk as she must have sunk, hasn't submitted without protest and rancour, Helen."

The gentle heart to whom he spoke resented this cold sagacity.

"Madame de Montmorin will be wondering what has become of us," she answered. "Let us go, Louis, while Cornelia sleeps."

But if she hoped to direct him from the subject of Pauline Fermor she was disappointed. As they crossed the park that sloped to the ornate gardens of Château Montmorin, he asked:

"What have you decided about your cousin, Helen?"

"When lam next in London I shall go and see her—"

"I think you make a great mistake."

"I'm sorry, but I cannot see anything else to do," murmured Helen.

"It will be painful for you—you don't know what the milieu is."

"I can guess from that letter."

"But you don't know it, Helen. You haven't really been near anything sordid in your life."

"That sounds like a reproach," said Helen, troubled. "I've been very selfish—"

"Don't," he answered roughly. "I didn't want you to say that; I don't want you to be bothered in the least by this; I don't," he added rather passionately, "want you to see this woman; if you do, you will be anxious to make amends.

"Why not?" asked Helen.

He took her arm to guide her lightly in between the tall chestnut trees that formed a scattered belt on the edge of the park; the stars glimmered low between the slender trunks, and here and there flashed between the thickly leaved boughs.

"Because it can't be done," he answered. "You can't make amends to anyone—if this cousin wanted help and you gave it her she would only detest you."

"Why should she detest me?"

"Because she isn't like you and never could be," he answered as if he was humouring a child; she replied to his tone more than to his words.

"You are very wise, Louis, and I can't argue with you, but all the same I am going to see my Cousin Pauline."

"At least let me go first."

"No." Helen was quite resolute now. She felt that to send Louis Van Quellin would be to expose this unknown Pauline to humiliation. "That is impossible, Louis, I must go myself."

"Then I will come with you."

Helen was doubtful even of that, but she made no further protest.

"Will you go to London in September?" she asked.

"Towards the end of September, yes. I must go to Paradys for a month or two, and then to Brussels. I will leave Cornelia here, if you are staying with the Montmorins—"

"Yes, I've promised Jeanne to remain till I go to London. I like Marli."

"Cornelia really loves the place—and Henriot can stay here—"

He spoke as if he hardly was thinking of what he said; the lights in the château windows now showed across the level sweep of grass and parterres and very distantly came the melody of the slow violin.

"When are you going to marry me?" added Van Quellin seriously.

Helen did not want to reply; she was still thinking of Pauline and Mrs. Falaise, both unpleasant difficulties that had yet to be faced, and the question of Louis reminded her, rather sharply, that her liberty of action was becoming jealously circumscribed; if she had been married to Louis she would probably have been actually forbidden to have anything to do with Pauline Fermor.

"What are you delaying for?" he urged. "Aren't you quite sure?"

"You know lam quite sure, Louis," she answered faintly. "It is Cornelia."

This was true, but there was something besides, and he knew it.

"You must not think of that," he answered harshly. "Henriot told me to-day that things will never be different for Cornelia—she may live for years, even to be old, and she may be, probably will be much stronger, but—"

His firm voice ceased, and Helen was grateful to the merciful veiling bloom of the summer dark that hid his passion and his pain.

"Louis," she said; and now she spoke entirely without reserve. "Does Cornelia really like me? I should have to go away for ever if she didn't really like me—"

"Cornelia loves you, Helen; everyone who knows you loves you."

They were walking across the garden now; the smell of the box hedges was like an aromatic in the air.

Helen could not altogether satisfy herself that her marriage would not hurt Cornelia; not so much for the reason, which one could speak of, that it would take her brother away from her, as for the reason, which one could not speak of, that it would be melancholy for the sick girl to be daily witness of that particular happiness that she must never know.

But Louis Van Quellin insisted on his own viewpoint; he would have no more hesitations nor refinements. "The alterations I am having at Paradys will be finished in the early spring—your rooms, your gardens; will you marry me then, Helen?"

She felt that it would be an unkindness, almost a meanness to dally any longer, perilous too with a man like this; and though she did not want wholly to surrender to him (and she guessed that marriage with him would mean a complete surrender) still less did she wish to lose his love or any tittle of his complete devotion.

"I will marry you in the spring," she said simply. "April—Louis, will that please you? I hope," she added wistfully, "that you will be kind to me and just sometimes let me do as I like—even if it is silly."

"I shall not thwart you in a single whim!" he conceded with a sudden rise of spirits.

"Ah, whims!" answered Helen. "It is one thing to indulge one's whims and another to let one really have one's own way."

Louis Van Quellin thought so too, but he did not care to enlarge on the subtle difference.

The supper was served on the terrace, lit by the saffron electric lamps cunningly contrived among the frail trails of jasmine that floated from the brick front of the château; this light ended with the terrace; below the garden was in darkness, and beyond were the darker park and dense hedges of blackness where the groves of trees were reared up against the pellucid night sky, where the stars flashed coloured rays with a cold intensity of radiance.

Helen was suddenly very tired and oppressed with her problems—the problem of how to soothe Cornelia on the question of Mrs. Falaise, and the problem of what quite to do with this unknown cousin; both these would have appeared trivial to many, perhaps most people, but Helen's life had been unclouded even by difficulties slight as these.

She noted the animation that Louis showed, the conquering look in those pale formidable eyes, and she dreaded the struggle there would be with him on the subject of Pauline Fermor.

MADAME DE MONTMORIN rose.

"Helen, lam sure that you are very tired—that long motor drive and then going straight to Cornelia—it is really late, and you are to come upstairs at once."

Helen was glad of these affectionate commands; she was not only tired, she wished very much to be alone and to read quietly again the letter of Pauline Fermor; as the men watched the pale, soft dresses of the women fade into the dusk beyond the saffron of the lamplight, M. de Montmorin said:

"Helen agitated! I have never noticed that before."

And Van Quellin, immovable, pushed back his easy chair in the shadow by the balustrade:

"The poor child has two worries—the first is purely chimerical; Cornelia took a fancy to calling in that American faith healer, Mrs. Falaise' and Helen thinks she ought to be indulged." He lit a cigar and the spurt of the light showed his long hands. "Of course it is impossible, and I fear that Helen thinks me a brute."

The elder man made a little gesture that regretfully dismissed a charming feminine folly.

"The other," continued Van Quellin out of the pleasant dusk, "is more important—a cousin has appeared out of nowhere."

"Helen's cousin? I did not know that she had any relations."

"Nor I till the other day; this is the only one, the daughter of an Uncle Paul."

"Why is it a trouble to Helen?"

A slight silence fell; it was tacitly understood between the two men, both of noble birth, that the beloved Helen was of a meaner origin than the admiring people among whom she moved, but it had, naturally, never been mentioned.

Now, Van Quellin at length said to this old friend of his, who had also been the friend of M. St. Luc:

"Helen's father was an engineer, you know, a mechanical engineer, the son of a gentleman farmer I think; there were two brothers, and the other, Paul' was a scoundrel; he seems to have died under disgraceful circumstances, leaving a widow and this daughter unprovided for."

"Wasn't the other M. Fermor a very wealthy man?"

"Yes, after the success of his new brake system, the patent brought him in hundreds of thousands. I never met him; he died soon after Helen's marriage—he seems to have lived very quietly and to have made few friends. Helen has an etching of him. I like his face."

"Didn't he help his brother?" asked M. de Montmorin.

Van Quellin shrugged his shoulders.

"Helen believes so; of course she only knows what her father chose to tell her, and there was, at any rate, a complete cleavage between the two. Helen is—as you see her, and this woman writes a letter like a kitchen-maid from a back street in an English country town."

M. de Montmorin was shocked.

"That is disgusting," he remarked.

"Yes. There is something behind it too, after a silence of thirty years!"

"Afraid to approach the father perhaps?"

"But M. Mark Fermor has been dead eight years."

M. de Montmorin reflected a moment; then asked:

"What do you make of it?"

"I don't quite know till I've heard something more about M. Paul Fermor. I'm going to make inquiries in London; if he was a real outsider this girl may be as bad, and I don't know anything about the mother. She is blind, by the way."

"How do they exist?"

"I don't know at all; I didn't like the letter. It seemed to me artificial and sly. Hopelessly illiterate."

"How horrible for Helen," said M. de Montmorin. "And for you," he added carefully.

"Yes. You can understand the appeal to one of Helen's temperament! The poverty, the blind mother, the only relation she has in the world, and so on. Helen's so tender-hearted and romantic—will just allow herself to be tormented and despoiled."

"You must prevent that."

"Yes. It isn't so easy without hurting Helen. It is a delicate matter too. They are not my relations, and Helen has her own money."

"If she only gives them money," suggested the elder man, "it will not so much matter, but I fear, with Helen, it will not stop at money."

"Of course not," replied Van Quellin calmly, "she will overwhelm them with attentions. Naturally they are entirely unpresentable."

"The girl might not be, she's Helen's cousin."

"My dear Montmorin, you have not seen the letter she wrote!" replied the young man dryly. "The mother must have been of the lowest class to have allowed them to sink like this, the father was a drunkard and a wastrel, and the Fermors," added the aristocratic Fleming unconsciously, "were hardly gentle people; Helen is scarcely prepared for what she will find."

"You must not allow them to see her alone."

"Certainly not. I hope she won't see them at all; but she is bent on it, as soon as she returns to London in September."

M. de Montmorin could deeply sympathise with the acute though well-concealed annoyance of Louis Van Quellin; he was a wide-minded, sensible, tolerant man, and could easily appreciate the present-day discount of aristocracy, yet himself a cadet of one of the oldest French families, he must appreciate the vexation that a man of Van Quellin's birth must always have felt at Helen's frankly middle-class origin; fine breeding was a tradition and a natural tradition with the Van Quellins and the mother of Louis had been a rather austere and narrow English patrician.

While Helen stood absolutely alone this question of her antecedents had been a very deeply concealed irritation; now, it had come, with the discovery of these incredible relations, very prominently to the front.

M. de Montmorin, with an elderly Frenchman's fine flavour for subtle emotions, wondered if Helen quite knew what her championing of these relations would mean to Louis Van Quellin; he would never be able to tell her, and she—and that was where the middle class would show in sweet Helen—would never be able to guess.

"It is a thousand pities," remarked the old man sincerely, "that this has risen."

The seriousness with which he spoke showed Louis that he had been completely comprehended; M. de Montmorin had appreciated the sting about which neither of them could speak.

"Helen," said the young man slowly; he always lingered a little over her darling name, for sheer pleasure in the sound, "is too good-hearted; wherever she goes she comes back with an empty purse; she always spies out some recipient for her alms."

"Without you these people would have found an easy victim—do they ask for any help?"

"No. I feel that is to come, the letter is very cautious. Of course the woman would never have written if she had had any decent reserves—what could," added the young man impatiently, "she have brought herself to the notice of Helen for, if not for some hoped-for benefit?"

"Exactly. I don't understand the long silence; even if they dared not approach M. Fermor, they must have been easily able to trace Helen's movements since her marriage."

"Of course. I am sure there is something unpleasant behind that letter. I'm afraid that Helen feels that also—she is so superstitious," he smiled tenderly. "She really was in earnest about her vase, and then when I brought it back whole—the ring of Polycrates, you know, she was quite disturbed."

"You should have broken the vase yourself, Van Quellin."

The young man shook his head.

"You can't cheat with Helen."

M. de Montmorin saw that; impossible to deceive that fine candour, that complete trust.

"That will make it more difficult as regards this cousin," he remarked.

"Ah, yes, you may be sure that Helen will have her own way," and he spoke regretfully, as if he did not altogether care for the prospect of Helen having always her own way.

Madame de Montmorin joined them; she took the chair that Helen had left between the two men.

"Helen is very tired," she said. "Something is troubling her. What was it that Cornelia wanted to see her about so urgently?"

"A certain Mrs. Falaise, a faith healer; Cornelia had the caprice to want to try the woman; of course impossible."

Jeanne de Montmorin took this very seriously.

"Louis, you must be very careful that Cornelia never meets a person like that; she could not endure the excitement. I am quite sure that it would kill her."

"Naturally I should not think of it," replied Van Quellin briefly.

He rose and went to the terrace balustrade that still seemed to hold the warmth of the long day's sun, and looked across the dark park to where Helen had looked; he guessed that she had been thinking of Cornelia, and he allowed himself to dwell on the fact that the sick girl, for all her slightness and humility, was powerfully affecting them both.

And he decided that this poignant burden was enough; he would have nothing to do with Helen's obscure cousin.

Even as he was resolving this, Helen, upstairs in her bedroom, was writing an affectionate letter to this same cousin.

ALL these reflections, hesitations, influences and counter influences ended in one clear fact; on a bright afternoon in September, six weeks later, Helen St. Luc drove out to see Pauline; and Louis Van Quellin was with her in the car.

He had defeated her on the subject of Mrs. Falaise; nothing more had been said, for weeks now, about the American faith healer, but he had not been able to defeat her on the matter of Pauline Fermor.

Helen had only been a few days in London when she insisted on seeking out her cousin; Van Quellin had only been able to obtain the privilege of accompanying her; and this had been conceded with reluctance.

"You're hostile, Louis, and it will show," she said. "I don't think it quite fair for you to come."

But he was there, and apparently in the best of good humours; the day seemed brimful of sunshine that overflowed everything with prodigal light, the rich fields, the yellowing trees, the bronze and crimson fruit in the orchards were all drenched in this mellow radiance.

Helen began to lose the sense of the squalor that letter had conveyed; she thought of Pauline in one of these little white cottages, singing at a latticed window while the quiet old mother dozed among the autumn flowers in the garden shaded by an apple tree; and she told Van Quellin, with much enthusiasm, of this picture she had evolved from the inspiration of the delicious countryside.

He smiled, but kindly.

"You forget they live in a town."

But no, Helen was not daunted; the town proved to be wholly charming, with an enchanting high street sloping down to the trickle of the river across the lush meadows.

But Louis still smiled.

There was a pause while inquiries were made for "Fernlea," Clifton Street. Helen refused to recognise the ugliness of these names, or the visible surprise on the part of the inhabitants that such a lady in such a car should ask for them; but directions were at last given and the car turned out of the old streets with the air of spare dignity, into a congerie of modern streets straggling up the hill; and Helen found that there could be dingy, meagre quarters even in the most engaging of ancient towns; and as the car slowly moved down the narrowness of Clifton Street, she began to feel foolishly nervous.

Pauline had not replied to her affectionate letter, promising a visit in the autumn, and she had not let her know of her coming.

This on the stern solicitation of Louis, who did not want a scene staged for their benefit, but to discover these people in the ordinary vocations of their ordinary life; Helen had agreed, for it never occurred to her that a surprise visit could embarrass anyone; she had not the shrewdness that can guess at things entirely beyond personal experience.

But as she realised the dilapidated modernity of Clifton Street, she saw that it was impossible to take either the car or Louis Van Quellin to "Fernlea."

She made the chauffeur back and stopped him at the corner by the pillar box where Pauline had posted her letter to her cousin.

"You must wait here for me," she said hurriedly. "I will go and see what they are like—if they want to see you or not," she added dubiously, for both the magnificence of Louis and the elegance of the car looked cruelly out of place against this background of stingy drabness.

"If you don't return soon I shall come and fetch you," returned Louis; he did not mean to give her more than ten minutes.

Helen went nervously along the wretched little street; conscious of frousy heads behind white Nottingham curtains at the windows, and dirty gazing children at the tiny gates; the sordid air of the city slum dweller was here mingled with the spiritless apathy of the peasant; Clifton Street gained an air of mingy decency by this close proximity to the open country, but also a dullness almost an imbecility, unknown in cities.

Helen found "Fernlea."

The house was incredible to her; or rather not a house, only a portion of a house as a crazy paling bisected the garden and the low windows of the miserable little building, making it into the dwellings.

The low window in "Fernlea" was masked by the lead colour of the badly washed curtains pinned together in the centre, and garnished with a card with the word "Apartments" in silver on a harsh blue ground; the last rain had traced lines on the dirt of the window-pane, dust and soot lay thick on the peeling stucco of the sill.

The door was blistered; neglect had turned the knocker and the letter box acid with verdigris colour, and in the fanlight was another card, "Apartments," hanging slightly crooked.

The small square of garden was a mere tangle of sprawling seeding marigolds, the upper window had the faded blind pulled down.

Helen stepped back to make sure that there was not some mistake; but the word "Fernlea" was written in chocolate brown on either of the short plaster pillars at the gate. There was something so repellent, even sinister, about this blank dismal house that Helen would have turned away, in sheer cowardice, if it had not been for the thought of Van Quellin waiting in the car, and of having to confess her failure to his amusement.

As she timidly raised the knocker and saw her beautiful gloved hands resting on that horrible little door she was conscious how out of harmony her clothes were with this visit; she had come dressed plainly, but she had nothing in her wardrobe that would have been suitable for "Fernlea."

She had to knock again before the door was opened; and then it was only moved cautiously, a mere suspicious slit; Helen could not know that the few people who came to this house passed round the back to the door that opened into the scullery.

Helen saw the face of a young woman against the murk of the cramped hall, a peculiar face she thought it, with the grand brows, the scowling eyes and the mass of dried bay leaf coloured hair slipping down her back.

"Is Miss Fermor here?" asked Helen nervously. "Miss Pauline Fermor?"

Pauline opened the door wider; in this slender stranger in the pearl coloured coat and collar of smoky fox fur and the black hat with the single drooping grey plume, she had not recognised her cousin; she thought of a possible lodger, but saw at once that this lady was too fine for "Fernlea," so answered sullenly, without any attempt to please:

"I'm Pauline Fermor."

"Then you are my cousin," said Helen, holding out her hand. "May I come in and speak to you?"

Pauline had something of the sensation of the poor Arabian fisherman who rubbed an old bottle and evoked a genie; her letter to have brought this creature to her doorstep!

Helen had written certainly, and spoken of a visit, but Pauline had never given any credence to that.

She flushed dully, and just touched the outstretched hand with her soiled fingers.

"Please come in." She led the way into the parlour, that was only used by the occasional summer lodger.

The cramped hall, the shabby room, half stifled Helen; the atrocious wall paper, ornaments and fusty furniture, the cheap piano loaded with little vases, the paper flowers in the grate, the stale, rancid, enclosed air she found unbearable.

"It is so strange that we have not met before," she smiled.

"Very," said Pauline.

With keen, swift glances she was noting every detail of Helen's person; the other cousin dare not make this close scrutiny; she had a distressing impression of a shabby serge frock and a dirty apron, ruined hands and a manner of dreadful defiance.

"You said that you would like to see me," she continued, bravely pursuing her point, "so I have come as soon as I returned to London."

"I never thought that you would," returned Pauline bluntly.

"Oh, why?"

"Well—look at us."

Even Helen's ready sweetness could not immediately find an answer to this.

"You would hardly think," added Pauline, "that our fathers were brothers."

And she continued to regard her cousin with those darting glances of hostile curiosity.