From the American Armed Forces Edition, 1940

Joseph Shearing is not a man but a woman. Mrs. Gabrielle Margaret Vere Campbell Long has finally confessed to the authorship of the "Joseph Shearing" novels. For some time she had been suspected as the author "who indeed possesses many of the necessary qualifications, such as a knowledge of English Bohemian life and of French and English criminology."

Mrs. Long is an English historical novelist and short story writer, born on Hayling Island, the daughter of a Moravian clergyman. As a child she was haunted by nocturnal fears, and she deeply disliked the Bohemian life led by her emotionally unstable mother. She taught herself to read and to paint, disregarded the fact that she seldom had enough to eat, and made the most of the materials at hand.

She studied art at the Slade School in London and spent a year in Paris absorbing French history and local color. Her first novel was published when she was sixteen. It was a success, although she waived royalties and received only sixty pounds by grace of her publisher. More favorable terms were arranged for subsequent works, and she began a steady "grind" of writing to support her extravagant mother and her sister.

After about ten years she married Don Zeffrino Emilio Costanzo, a Sicilian who died in 1916. a son survived. In 1917 she married Arthur L. Long of Richmond, Surrey, and by this marriage she has two sons.

Joseph Shearing is not the only pseudonym Mrs. Long has adopted. Her best known one is perhaps Marjorie Bowen, her only feminine nom de plume. Under it she has some sixty-odd titles to her credit.

She has three other male pseudonyms: "George Preedy," "Robert Paye," and "John Winch." As "George Preedy" she has written about twenty books. "Robert Paye" and "John Winch" have each written only four or five.

The Joseph Shearing novels number about a dozen. The first of these, called Forget-me-Not in England but changed to Lucille Clery; A Woman of Intrigue in the United States, dealt with the same Paris murder case—the murder of the Duchesse de Praslin in Paris, 1847—as did Rachel Field's All This and Heaven Too. It was re-issued in 1941 as The Strange Case of Lucille, Clery.

Of the Shearing novels, Sally Benson wrote in The New Yorker that "there are many adjectives that apply to all Mr. Shearing's books: evil, sinister, ghostly, strange, baleful, terrible, relentless, malevolent. Such experts in murder as Edumnd Pearson and the former Scotch barrister William Roughead have declared openly that the Shearing novels are the best of their kind published today. Mr. Shearing is adept at stitching together his swooning heroines, his young baronets, his flickering candles in their tall sconces, his hothouse fruits in high silver-gilt epergnes with a strong, red thread of murder. Mr. Shearing is a painstaking technician and a master of horror. There is no one else quite like him."

[Compiled from information in Twentieth Century Authors by Kunitz and Haycraft, published by the H. W. Wilson Company.]

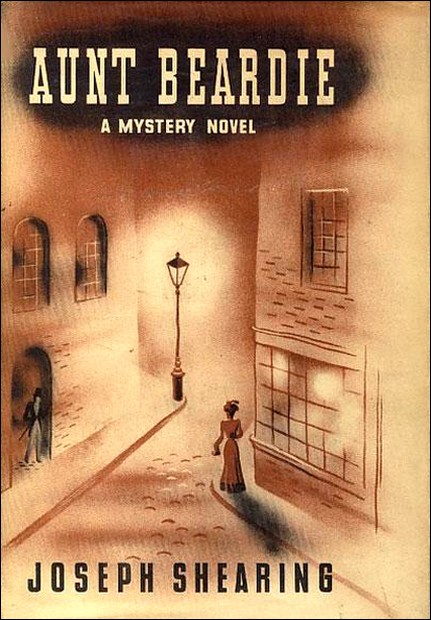

Cover of first US edition (Harrison-Hilton), 1940

A young man lay on a hard bed and stared at the square

of bright blue

sky he could see from his attic window. He was ardent and ambitious and his

plans were taken up with a brilliant future. It should not be so difficult

for him to gain all he wanted, he argued to himself, for these were

tempestuous times, when the ordinary rules of society were set aside, and it

was only strange and embittering that he had not already found a chance of

enriching himself.

It was true that he was poor and of humble birth and of humbler occupation,

but he had taken great trouble with himself and he was naturally

gifted—sharp-witted, adroit, of distinguished manners and a noble

appearance—strange heritage for one who was little more than a peasant!

So far he had not been able to turn these advantages to much account. Many

circumstances that he tried to forget had been against him, and he was still

no more than twenty years of age.

He did not notice the square of blue sky nor the coral-coloured buds of apple

blossom against it, resting on the gnarled, lichen-covered boughs; nor did he

hear the shrill, lilting songs of the birds that fluttered to and fro in the

old grey trees, or note the bittersweet smell of earth newly wet by rain, or

the almost intangible odour of springing grasses.

He was unconscious, too, of the hardness of the pallet on which he rested, of

the poverty of his attire, for with his well-kept hands clasped behind his

dark head he was staring into a golden future. He wanted everything that

evoked the lust and ambition of ordinary men: money and fame, an easy life

with an heroic lustre, a beautiful woman for his wife, and noble friends to

be subservient to him.

The scope of these desires was one reason for his ill success; every chance

that had come his way had seemed to him too mean for his abilities. He did

not want to shine in his native suburb, or even to be a great man in his

native town. He longed always for large affairs, and often turned over in his

active mind how he might make the acquaintance of those in high places.

This dreamer felt that his gifts were sufficiently brilliant to allow him to

await patiently a fine chance. He had not been idle; there was his daily

work, his humble work, his part to play among his fellows.

And he had to be careful not to arouse their suspicions about anything

unusual, possibly dangerous, in his manner or mind, for these were times when

a man might be clapped on the shoulder in the morning by the hand of

authority and be a headless corpse by the evening.

But with the few pence at his command he had purchased books, and in the

attic that was his allotted chamber and was too poor a place to excite

anyone's curiosity, he had studied, using logic and imagination instead of

experience, teaching himself all that he believed would be useful when he had

achieved his ambition and moved easily among the wealthy and the nobly born.

Whenever he went abroad he marked eagerly those of better condition than

himself, how they behaved and spoke, what manner of dress they favoured.

He had strong natural gifts of dissimulation also, and it often amused him to

play different parts, altering the tone of his voice, even the lines of his

face, adjusting his garments so that his personality was quite disguised.

Though his thoughts were wholly selfish and of his own aggrandisement and the

glory that should one day be his, they were not without a certain gloss of

grandeur. They had the purity and the simplicity of youth, and his face,

framed by dark masses of chestnut hair and lit by the sun falling through

that poor, unglazed window, had a not ignoble beauty, while the unconscious

smile that lifted his lips as he dreamed had charm and pathos, as well as

hard and cynical lines.

The fugitives were at the end of their resources, quite overwhelmed by terror and dismay.

M. de Saint-Alde looked at his daughter in despair. What a fool he had been! He had always considered himself a capable man, but then, he had never been faced by circumstances so atrocious as these.

What was he to do? Where to go? He had weathered five or six years of storms successfully, keeping in with this side and that, using his enormous fortune, as he thought, entirely to his own advantage, to save him not only from debt and imprisonment but to keep him in a comfortable position. And here he was, stranded, with his young daughter, almost a child, on his hands. And what was in front of him?

The last, and as he feared the crowning, misfortune was that the servants had left them. And here they were in this inn, in the suburb of Orleans, not knowing where to turn and with a hubbub increasing about them. His one small consolation was that his daughter did not seem to realize her peril or even to fret at her discomfort. She sat looking plump and sleepy, like a stupid little bird, on the hard chair in the dirty parlour, her head nodding on her bosom, her eyes blinking drowsily.

Poor child! M. de Saint-Alde's agitation almost overcame him. He knew what had happened to girls no, older than she was, in Paris where now anarchy ruled.

But that he should have failed like this!—that was so inexplicable. He who had been so cautious, who had friends in every camp, or so he had thought...

The host of the Saint-Louis looked at him suspiciously. M. de Saint-Alde had lost his usual prudence, his usual sense of men and matters, his worldly understanding. He stammered out his orders afraid to spend too much or too little. He gave the stupid story that he was a merchant, travelling in wine, that his servants had fallen sick.

The host walked away, shrugging his heavy shoulders. He was not interested in the lies that fugitives told him.

'Perhaps,' thought M. de Saint-Alde bitterly, 'he is going to denounce us to the police.'

Then with his native shrewdness and common sense piercing through the confusion of his distress, he thought: 'Tell what to the police? What have I done? They can bring nothing against me, nothing!'

But he knew that this logic was in the circumstances mere foolishness. He did not need to have 'done anything.' He had attracted the attention of those in power who disliked him, who envied his wealth. All his money would be confiscated, all that fortune he had piled up with so much difficulty...

He thrust his fingers into his hair, which was damp with sweat.

'I must control myself, I must get some courage. What must be done? Where can we go?'

It had been exactly like a lunatic nightmare, and he had had a good many nightmares in the last few years.

That hurried flight from Paris to Versailles, when his loan to d'Artois was discovered, believing that there it would be quiet and safe, and then the warnings from friends, the meeting of those whom he believed to be spies in the streets, the arrival of the frightened woman with whom he had placed his daughter, for safety as he believed, saying that she could no longer have the responsibility...the child looking at him, asking him what was to become of them, what was happening, and yet all the while quite trusting and good-natured, which in a way made matters worse...his frantic attempts to find 'a woman friend to look after the girl, or even a maid. Impossible! Everything in confusion!

And then the sudden resolve to fly with all the money he could lay hands on. Where? To England, he supposed, though he had no great love for that country. But it was the nearest asylum. And with money one could buy security and comfort, he still believed, anywhere.

But how to get to England? He almost beat his fists on the table, soiled with sops of wine and crumbs, in his impotent distress.

Why, they might be murdered and robbed that very night. He had gold and his dead wife's jewels worth a considerable amount in his valise. There was the carriage, too—he had had to pay an extravagant price for that, though it was the shabbiest equipage he had ever ridden in. It was waiting in the inn yard now. Should he spend his money in pay ing for horses to take them farther? But take them where? And dare he trust the postillions?

The best thing he could do would be to get to Brittany; he knew that country. St. Malo—that was the place. But he had no map. 'I must have lost my head like a coward,' he thought. 'I came away in such a hurry I didn't bring anything that was essential.'

He had got passports, but one needed to renew passports every few months when the chief of the Government changed. His identity papers were weeks old and might be of no use. The men who had signed them might already have gone to the guillotine.

For myself I don't care,' he said to himself mechanically, as the host brought in a litre of sour wine and placed it on the table before him, 'but for Estienne it is horrible.'

This was not sincere, although the reflection was made in the privacy of his own mind. Deep in his heart he did care for life, for his own safety. He had been successful and had enjoyed his existence, relished his brilliant career and the handling of large sums of money, enjoyed his social success. He was still a youngish man, though worn out by work and pleasure. He was very much afraid of prison and of violent death.

Trying to control himself, he went over to his daughter. She asked him sleepily when they were proceeding on their way and where they were going.

The terrors of the time did not seem to afflict her, even unconsciously. She had been at her pension for demoiselles since she was five years old, when her mother had died she was almost a stranger to her father, but her soft youth and her foolishness moved him to an almost uncontrollable tenderness.

He patted her hand, his own flesh trembling as he touched hers.

"We shall be all right, we shall be gone in a while. Rest yourself, my child, rest yourself. Eat your bread and milk, anything they give you."

"Oh, I'm not hungry, Papa, I ate so many biscuits and so much fruit in the coach. I think it would be better to go on." She looked round with ingenuous disgust. "It is very dirty," she added, "is it not? I do not like the look of the so vulgar people."

"Hush, hush, my child, you must not say those things, you do not know who is around us."

The banker returned to the table, glanced at the wine with a shudder and pushed it away from him. He did not want that to upset his digestion and fuddle his mind still further. He had felt ill ever since they had left Paris. Even at Versailles his stomach had been turned constantly by some queasy sight or smell. He was not as strong as he had thought he was, his head throbbed and he was subject to fits of giddiness. He was a stout man, not ill-looking, but out of condition. He sat there in his handsome clothes, his flabby face in his hands, trying to think of a way out...

The landlord put his head, garnished with a greasy red cap, around the door and said insolently: "The police will want to see the passports of the citizen and the citizeness." And with that had slammed the door again.

'Shall I bribe him?' thought M. de Saint-Alde. Then a wave of almost suffocating bitterness overcame him. He thought of the five million livres that he had lent to M. d'Artois. Why, it had been that sum of money which had enabled the Prince to escape to the Rhine, where he lay now with a considerable army, comfortable, even luxurious, on basketfuls of English gold!

'If I could only get there,' thought M. de Saint-Alde. 'I'd get it back out of him or live on him indefinitely.'

What a fool he had been! He had thought his loan a measure that secured his future. At the time it had seemed that the Revolution could not last long and that the Bourbons would soon return. And then what might he not exact in the way of gratitude for that large sum of money!

But no, the Prince had fled, and letters written to him at his camp on the Rhine had not been answered.

'But I've got the papers,' thought the banker, patting his waistcoat, 'and I'll keep them. Maybe it'll be all the dowry that Estienne will ever have.'

Yes, there were the Prince's papers, with his seal and bond to repay, and at a handsome interest, the five million livres that enabled him to escape the scaffold his brother and sister-in-law had mounted. Then how much more good money had been spent in bribing members of the Convention, trying to keep them his friends and on his side! What a fool he had been! He had really believed that they thought him useful, even necessary, that they counted on his advice, that they wanted him to keep his bank open.

He tried to stop his thoughts. He remembered the papers that one who was still his friend had shown him. There was his name on a list of proscribed. That meant the guillotine, perhaps, two or three days after his arrest.

Well, he had got as far as Orleans. He reached out a trembling hand, hardly knowing what he did, and after all gulped down the sour wine.

The door opened and the banker started, thinking that this was the police, but a young man of prepossessing appearance stood inside the doorway, looking at him shrewdly.

The banker, confused, taken aback, rose and bowed. He might be speaking to some high local functionary for all he knew.

The bow was returned courteously and the young man came to the table. He was tall and well made and wore a long green travelling-coat with several capes, a beaver hat stuck at a rakish angle, and his dark chestnut hair in a horn buckle. His features were pleasant, even noble, although their complete symmetry was spoiled by the fact that his eyes were rather too deep-set and too close together. He had a bearing at once proud and dignified, and his greeting to M. de Saint-Alde was cordial.

"I heard," he said, with a slight air of mystery and speaking softly, "that a gentleman—a nobleman, perhaps—was in this little inn with a young lady—his daughter, possibly."

The young man's voice was low and pleasant and was raised at each of these questions. 'The banker, thinking that he had found a friend, perhaps a protector, nodded eagerly; he was past subterfuge and attempts at discretion.

"Yes. You are a resident in Orleans, you are prepared to help me, monsieur? I cannot tell you how grateful—I am not unknown in Paris."

The stranger put his finger on his lips.

"We will not exchange names, if you please," he remarked. "At least, I do not care to give mine. The reason in these times you may find easy to guess."

"Certainly, certainly," agreed M. de Saint-Alde, also keeping his voice low. "But I should like you to know who I am." And he gave his name and a brief recital of his history of The last few weeks.

The young man listened attentively.

"I am in some difficulties myself;" he admitted. "I am afraid I cannot imitate your frankness and tell you what they are."

"Indeed, sir, I do not ask your confidences," protested M. de Saint-Alde. Of weak and indolent nature, he clung at once and almost desperately to this younger, stronger man who seemed in everything more resolute and more capable. "If you could help us..." he stammered, and glanced towards his daughter, who was now sound asleep in the hard chair with the chintz-covered cushions.

The young man looked in the same direction. His eyebrows went up slightly.

"I see your situation, monsieur, with so young a girl—why, she is little more than a child."

"And motherless. I was not able to obtain a maid or any other female to accompany her. What do you suggest we do?"

"I suggest you leave the country," replied the young man, narrowing his eyes and tapping in a determined manner with his forefinger on the table. "Neither you are safe nor am I. I am making for the coast myself. I am, as it happens, a Breton, I know Brittany like the palm of my hand and I intend to go to St. Malo. You will find it crowded with refugees, no doubt, but I believe it will be possible to get a ship to take us to Plymouth."

These words were like balm to the distracted banker.

"May I put myself in your hands?" he begged. "I have a certain sum of money with me."

"That should make it easier, but in these times it is not possible always to purchase even bare safety with large amounts of money. But if you will put yourself in my hands I will see what can be done."

Without saying so in so many words, he then gave the banker to understand that he was an émigré, that he bore a well-known name and was in considerable danger; that he had been to Paris on some secret and difficult mission and now was endeavouring to return to England to communicate with some royal prince, possibly the Duc de Bourbon, M. de Saint-Alde thought, who was in hiding there.

There was nothing in the young man's manner or appearance to belie this story. He was dressed in middle-class fashion, it was true, but then, as he had said himself, he was in disguise. When the landlord entered he spoke to him with the gesture and accents of a man of the people, but M. de Saint-Alde was quite ready to accept that as part of the disguise also.

After half an hour's conversation he had put his affairs, with a sigh of the most desperate relief, in the hands of this capable young man, who at once proceeded to engage horses, a coachman and a postillion.

M. de Saint-Alde had pressed into his hands a wallet full of gold, and the young man appeared to make pretty good use of this. He got the man and child out of the inn, had their passports sent to the Town Hall, countersigned and brought back, and by the middle of the June night they were all three on the road that was to lead them by quick stages and with little repose to St. Malo.

The banker's worst anxiety was relieved by feeling himself again a free man and treated as a respected member of the upper class as he sat in the coach with his daughter sleeping against his shoulder, and he now began to thank the young man for his services and to express the hope that he had not taken him from his own affairs.

"No," said the stranger. "Indeed, I am only too honoured to be of service to one so distinguished in the Royalist cause"—and he bowed in the narrow space of the coach gracefully enough—"as yourself, M. de Saint-Alde. If I must still delay giving you my name, it is not because I mistrust you but because I am under a vow not to disclose it. As it is awkward, however, for me to be incognito, pray call me M. Bernard."

"I assure you, my dear monsieur," replied the grateful banker, "I had not the least curiosity to learn who or what you are or what your mission is. Indeed, I feel as if I had had enough of politics and intrigue for all my life. It is sufficient that you have given me such inestimable advice and service. I hope I shall live to repay you."

And full of confidence and relief and even of joy in the reaction from his late state of terror, the banker disclosed to his friend that he had lent a large sum of money to M. d'Artois, and he tapped his breast where he kept the precious papers with the Bourbon seal and the signature of the young Prince.

"Of course, my dear monsieur," he concluded, "this revolution will soon be over, the State will be at rights again, and the Comte de Provence on the throne, for we must conclude that the Dauphin has been murdered like his father."

"Then you, M. de Saint-Alde," said the young man, leaning back in the carriage while his eyes gleamed in the faint glow of the lamp that fell through the open window, "will be an extremely rich and extremely fortunate man. Why, you will have titles, orders, perhaps a dukedom, and some noble man, maybe a Prince for your daughter."

"Oh, I don't rate my services as highly as that," said M. de Saint-Alde, with a slightly unctuous laugh, for he did indeed see the future in some such rosy glow as the other traveller had depicted.

He explained, with a sigh, that his daughter was his only child; he had had two sons, but they had died young. His wife had died some years ago, also, and he was not inclined to marry again.

"Indeed, I have been absorbed in affairs, in keeping my head above water, in running the business of the bank, you understand. Though I don't hope for anything so extravagant as you suggest, I suppose indeed that I shall get my reward when the Bourbons are restored."

"You should claim something handsome for your devotion."

"Oh, I am glad to risk my neck out of pure loyalty."

The young man looked out of the window. The artificial light of the carriage lamps, the misty blue of the rising moon, outlined his profile with an unearthly light. The banker, for a brief second, was disturbed by something in that face, a lift at the corner of the lips that was hardly a smile, a downcasting of the eyelids. As if an icy hand had pinched his heart, terror shot through the fugitive. Suppose he is a spy? Some creature of the revolutionary Tribunal?

The next instant, M. de Saint-Alde, who was always sanguine, dismissed this terror. But the young man, who certainly was extremely acute, appeared to have sensed this suspicion, for he turned his head slowly and remarked:

"You have been very trusting, M. de Saint-Alde. You put into my hands your life, your daughter, your money—everything you have."

"I cannot be deceived in one of your bearing," said the banker, bowing. "It is obvious that you are of distinguished birth, shall we say a nobleman? I have no reason to doubt your tale that you are on an important secret mission. After all," he added, rather lamely and foolishly, "you might have doubted me."

"I have seen your picture in the public prints, and read something of your career in the news-sheets and gazettes. You gave yourself out as a revolutionary. You were one of the Commissaries of the Public Treasury, and this help you gave to the Royalists must have been all done secretly."

"My dear monsieur, how on earth could I have remained in Paris had I not given out that I was on the side of the revolutionaries? And a pretty penny it cost me to keep in their good graces. I was even an officer in the National Guard."

M. Bernard, as he wished to be called, had hitherto taken no notice of the girl, but now he glanced at her, narrowing his eyes in an effort to discern her sleeping form that, cloaked and hooded, pressed against her father's side.

"It is very trying for mademoiselle. Does she not find such hurried journeying, such lack of rest, troublesome?"

"She's a schoolgirl," replied the father, "she understands nothing. She knows that for business and political reasons I am obliged to leave France hurriedly. Indeed, she has shown no concern. She is either very courageous or, poor child, very stupid."

"Shall we not call it innocence?" smiled M. Bernard. "A rose leaf blown before the storm! What shall it know where it goes or whence it came!"

This remark uttered in a thoughtful tone surprised M. de Saint-Alde. Again he had a slight touch of that queasy-uneasiness concerning the character of his companion. But he had, as M. Bernard himself had said, put everything in this stranger's hands, and it was too late now to think of anything in the way of doubt or suspicion. He was himself, this stout, tired man, extremely exhausted. He had hardly slept; it had been indeed a panic-stricken flight ever since he had left Paris...one disaster after another, and they crowded into his mind now, preventing him from resting—beginning with the desertion of his servants and his clerks...

Again M. Bernard seemed to read his mind, for he remarked coolly:

"You have had one good piece of good fortune, M. de Saint-Alde. You have kept, you told me, your valise with the money."

"Yes, and some banker' drafts too. They will be honoured in Lombard Street. And others, too, on Hamburg. I shall not be too badly off until the storm blows over."

"Have you enough to hire a boat? We shall find a number of refugees, as I said, at St. Malo and it may be difficult to get passages. But if you can pay a good round sum—"

"I would rather go as a passenger, both myself and my daughter. If I spend too much money on hiring a boat, what shall I have to live on when I reach England?"

"Well, leave it to me. I shall make as good a bargain as possible. I can assure you that I am no novice at this sort of business."

M. de Saint-Alde took this to mean that M. Bernard had been to and fro several times since the Revolution began and was an adept at making all the necessary tedious and perilous arrangements.

So it proved; they had no difficulties at any of the halts; M. Bernard acted as courier and steward of all, their fortunes. He spent very little of the money that M. de Saint-Alde gave him—less than a quarter, perhaps, of what the agitated banker would himself have scattered as bribes and fees. And when they reached St. Malo, both father and daughter were in fairly good spirits.

The girl had the resilience of youth. She liked the strangeness of the adventure, such a contrast to the monotonous days at her school where only now and then had disjointed tales of the strange happenings in the outer world come through. She had read something about England and looked forward to seeing that country. She scarcely remembered her mother and she had had no home life so she had nothing to regret in leaving France. Never before, indeed, had she had her father's company for so long a period, and his kindness to her, and the solicitude of M. Bernard for her comfort, were very grateful to one who had hitherto been merely a little girl, snubbed, ignored and lectured.

Estienne was fourteen years of age and it was impossible as yet to see what manner of woman she would become, though her good breeding was obvious. She was plump, well developed, with a brilliant complexion, black hair, blue eyes and indeterminate features. Naturally lazy, she was also ignorant and inexperienced to a degree unusual even for so young a girl, for she had never had a mother's teaching in social usages nor any companions of her own age beyond the other girls in the pension who had taken no heed of her because she was so indolent and dreamy and seldom mingled in their gossip or their sport.

The absconding maid had taken with her most of Estienne's band-boxes and valises and she had little with her besides the white-sprigged muslin dress with the pink sash, the pearl-coloured pelisse and chip straw bonnet that she wore.

St. Malo was, as M. Bernard had predicted, full of refugees waiting for boats to take them to Plymouth or, in some cases, Hamburg. Most of the inns were full, but their young escort contrived to find accommodation for the banker and his daughter without much difficulty, although the lodgings consisted of but two closet-like rooms of an inn in a suburb of the town. These, however, were clean and the landlord and his wife civil.

A good meal was at once provided, and the weather was balmy and sunny. The sea, which they were so soon to cross in leaving their native land, perhaps for ever—this thought was in the background of M. de Saint-Alde's mind, optimistic as he was—lay smooth and glittering as glass.

The perils that they had been through lay behind them, dark and sombre, hardly to be believed, and their spirits rose at the prospect of life again in the new land.

M. de Saint-Alde knew himself to be a good financier, he had important connection in London and knew besides several well-known people there. Now that he had control of his nerves again it was not difficult for him to visualize a very successful career in London. His gifts for business and finance could not be ignored or kept down. His ancient title, his proud lineage, would help him he knew well enough. He would be able to have his daughter taken under the wing of some compassionate English gentlewoman; altogether the future did not look at all grey, mid M. de Saint-Alde beamed pleasantly on the young man who had achieved what seemed to him almost a miracle.

M. Bernard looked a little tired and strained from the fatigues of the journey, all of which he had taken on his own shoulders. But he was extraordinarily sharp, adroit and clever; as M. de Saint-Alde noticed with great admiration. He surely must be a person who had done this sort of thing again and again, he pondered, when the young man came and told him of the round sum for which he had sold the carriage and how modestly he had contrived to settle the dues of the postillion and the coachman.

The one difficulty now was to find a ship; passages were all booked on the packets that lay in St. Malo harbour, for there had been in the last few days well-founded rumours of risings in Brittany and the native nobility were hurrying from their châteaux as fast as they could gather a few valuables together.

"We shall have to hire a boat," said M. Bernard. "There is a small packet that is willing to take us to Plymouth for not too high a sum. It is possible that I might find someone to share this expense with us."

"With us!" exclaimed M. de Saint-Alde in a tone of delight. "Is it possible, my dear fellow, that you are going to England with us?"

"My destination is certainly England," replied the young man, with a quiet smile. "If it pleases you, I will accompany you on the same packet, paying, of course, my share of the expenses."

M. de Saint-Alde bowed. Nothing could have delighted him more. This would mean that all the troubles of the voyage would fall on his young friend's shoulders. And as for the money, he cared little about that; he had the indifference towards expense of the man always used to handling large sums. He still could not realize that he possessed nothing in the world but the gold in his valise. It seemed to him that he had the almost incalculable resources of the bank behind him. And, indeed, he was justified in supposing that he would easily make money when he reached London.

So he was lavish with what he had in hand, and never inquired how much M. Bernard was paying for his own expenses, although that young gentleman kept presenting scrupulous accounts. But the banker laughed them aside and told him good-humouredly that he might now hire the packet and be quick about it, and if he could find someone else to share the expenses so much the better.

This conversation took place in the morning, and by the early afternoon M. Bernard returned to the little inn in the suburb, Les Trois Etoiles, bringing with him a stout, elderly, red-faced man who was leading a pretty little girl.

"I found this good fellow down at the quay endeavouring to secure a packet for himself and his little mistress," said M. Bernard, "and I have brought him here, seeing that mademoiselle is about the same age as your own little daughter."

On seeing another girl, Estienne had come forward from the window-seat where she was sitting idly watching the sea—she had never seen the ocean before. She curiously examined the other young lady, to whom she at length courteously gave her hand and whom she kissed on the cheek.

Her elderly companion proved to be a servant of her father, M. de Vernon, the name of a noble Breton family well known to M. de Saint-Alde. The servant, with much agitation, for he deeply felt the responsibility of his little mistress's safety, told his story.

The entire Vernon family intended, upon the news that an insurrection in Brittany was imminent, to go to England, where they had friends. But at the last moment Madame de Vernon, who was expecting another child, found it impossible to travel. Her husband had remained behind to protect her and had sent his daughter with the servant, whose name was Gilles, ahead with a certain sum of money and a packet of introductions to English people. However, he was not supposed to need them as M. de Vernon, his wife and the baby would follow almost immediately, joining Gilles and his little charge, Vivienne, at Plymouth.

The old man, who had been in the service of the Vernon family all his life, as his father had been, had undertaken this mission with mingled zeal and trepidation. He was eager to serve his master to the death, but he was also almost overwhelmed by the responsibility for his daughter. All the women servants had fled from the château, he explained, save wily his own daughter, who had remained in attendance on Madame de Vernon.

He concluded his simple and yet piteous story by saying that he had found it impossible when he reached St. Malo to engage passages for himself and his charge.

The money that his master had given him had not been sufficient, for M. de Vernon had not counted on such a rush of fugitives to St. Malo and the subsequent rise in the charges for hiring boats and securing passages.

M. de Saint-Alde was touched by the faithful servant's predicament, and commended M. Bernard for bringing him and the little girl to Les Trois Etoiles.

"My good fellow," he said, "your troubles are now at an end. You shall come with us—I have money for all. If you have not sufficient to pay your passage your master shall owe it me. Well do I know the Vernon family; their name is one of the noblest in the armorial of Brittany. Indeed, I believe that M. de Vernon's father was among my acquaintances and a client of the bank."

Gilles began to stammer out his gratitude and relief at being taken under the protection of a gentleman who would be able to bring so much more weight and influence to bear on their difficulties than he could himself. M. de Saint-Alde put all this aside good-humouredly.

"Look at the two demoiselles, how they have already made friends," he said, and he nodded towards the two little girls who were kneeling in the padded seat at the window of the inn parlour, pressing their noses against the glass and staring out to sea.

Vivienne was twelve years old, two years younger than her new friend. She had lived a very different kind of life, having been intensely happy with her young father and mother in the beautiful château with the farm and the home fields, and the tenantry and servants whom she had loved ever since she was a baby; it had required the utmost weight of her father's authority and her mother's tearful entreaties to leave all this with Gilles.

But something of her home-sickness and her regret at this hurried departure from her dear home was assuaged by the interest of this new friend. She had never been to a pension and had few companions of her own age. Like Estienne, she had had two brothers who had died very young. She remembered them with regret and told little anecdotes about them now to her companion.

The girls were soon, at this rate, on very good terms, although Estienne had little to talk about except a parrot, a dog and a cat= all of which had been beloved by her when she had been at the pension.

M. Bernard, who seemed inexhaustible, left the party for a while, but soon returned with the news that he had hired a boat. It was a German packet, the Sachsen, captain Peter Henlein. For fifty livres, to be paid in advance, he undertook to take M. de Saint-Alde and his daughter, Gilles and Mlle de Vernon, and M. Bernard to Plymouth.

Half of this sum Gilles was about to produce, but M. de Saint-Alde waved it aside.

"Fifty livres will not make a large cut in what I have brought with me," he said, and he told M. Bernard to go to his portmanteau and take out the required amount.

It was M. Bernard who had packed the belongings of the banker, who himself had been too ignorant of the ways of the world and too unused to travelling in this fashion to conceal his gold with much success. It had all been tied together in rouleaux of louis d'or in two large valises. These M. Bernard had taken out and distributed over the luggage, in the linings and hidden inside the rolled stockings and linen of monsieur and mademoiselle.

He now called Gilles aside and told him he was to play bodyguard over the money, not letting the two valises under any excuses out of his sight or anyone who handled them.

"It must not be suspected there's gold there," he said, "or we shall infallibly be robbed. And remember, it is all that you and your little mistress and M. de Saint-Alde and his daughter will have to depend on for some time to come."

After he had gone to conclude negotiations for the hire of the boat, Gilles asked M. de Saint-Alde who the young gentleman was, and the banker found that he had no answer ready.

But he replied with assurance, "Of course, my good fellow, you can see he is a gentleman, a nobleman, probably. He has good reason for his disguise, for I believe him to be on some secret mission for the Prince de Condé or the Duc de Bourbon in London."

And he added a good deal in praise of the young man who had rescued them, M. de Saint-Alde began now to think, from almost certain death.

The banker was rather surprised that Gilles did not at once acquiesce in his estimate of their protector, for now he had begun to think of M. Bernard as that.

"Under your permission, sir," said the servant, "but I don't know what to think. He doesn't seem to me, this M. Bernard, who has no title or nom de terre, to be an aristocrat."

The banker was surprised.

"I can't understand how you say that," he said, really baffled, for he knew that servants were quicker than anyone else at noticing class distinctions. "Of course, he disguises himself as a common fellow now and then. He alters his voice and his tone, and it is extraordinary the difference he can make in his face. But I never questioned his faith."

"No doubt he is honest," said Gilles with a deep sigh, "but I would myself that we were in the hands of someone we knew, not this mysterious stranger."

M. de Saint-Alde laughed; he was in a good humour.

That evening, before the sunset, the five of them embarked on the Sachsen.

All went tranquilly on the voyage from St. Malo—the ship was small, rude, but decent accommodation was offered to the two young ladies, who were respectfully treated by Captain Henlein and his sailors; the food was wholesome and the men's quarters clean.

M. de Saint-Alde allowed his spirits to rise still higher. The golden weather was like a gloss over everything, and after all, what had he left behind that he regretted? The last few months, even years, had been full of pressing anxieties and continual alarms. He had had to scheme this way, plan that way, intrigue, bribe, flatter. Well, he was an adept at all that kind of thing; but he was glad it was over. He began, in sentimental mood, to plan a peaceful life for himself and his daughter, who still seemed a stranger to him, in England, famous, as he had always understood, for its domestic felicities.

Besides, he carried the major part of his fortune with him. What need to regret his handsome hôtel in Paris, his country house, richly garnished as they might be with furniture, pictures and tapestry? What need to regret his chests of silver and gilt when he carried with him the letter from M. d'Artois acknowledging the debt of five million livres? That was certainly good for a dukedom when the Bourbons regained their own. And M. de Saint-Alde, although he had lived in the centre of events in Paris for so long, firmly believed that the Revolution had spent its force and that there would be a restoration in a few months' time, when the armies now gathering on the Rhine would march in triumph on the capital and restore a Bourbon on the throne of Saint-Louis.

M. Bernard seemed also in good spirits, but he kept himself rather apart from the people he had helped with such zeal and tact, and M. de Saint-Alde commended this withdrawal as a delicate courtesy.

M. Bernard had a cabin to himself and often had his meals there, although once or twice he appeared at the common table over which the captain presided.

M. de Saint-Alde had noticed two things—he was trained to observe—one was that there were several passengers on board the packet, although he believed that he and Gilles had hired it between them. The other was that the Breton servant appeared anxious, sombre and dissatisfied.

Sorry for his poor old man, who was weighed down by his sense of responsibility, M. de Saint-Alde took an opportunity of speaking to him, and the Breton at once broke out with what seemed to the banker a very curious suspicion. He said he did not like the ship, the captain, or those other passengers. Why did they keep themselves so apart, not speaking to anyone?

M. de Saint-Alde said he was not surprised at this, since they were obviously of an inferior class.

"I suppose the poor wretches could afford to pay very little and so were smuggled off at the very last minute. It certainly is not fair, for we bargained for the ship for ourselves; but who can refuse a charity under these circumstances? For myself, I have met with such good luck these last few days after experiencing such sharp reverses that I am not, my good fellow, inclined to grumble at such details as these."

"Maybe not, monsieur," replied the old servant heavily, but with the respect due to one of M. de Saint-Alde's rank. He looked at him wistfully. "I wish I could feel as secure as you do, monsieur. I have the charge of mademoiselle, you understand." He wiped his sweating forehead. "She is a very great responsibility. I am too old. Ah, that madame should have been brought to bed at such a moment! A few weeks one way or another and she could have crossed."

"It is indeed unfortunate, but I have no doubt that your master and mistress will soon follow and you will have a happy reunion at Plymouth."

"God grant that it may be so," sighed the Breton. He crossed himself and closed his eyes for a moment and the banker saw that his prayer was earnest and fervent.

"Why are you so downcast?" he asked kindly. "Look at me. I have, in a sense, lost everything, yet I am far more cheerful than you, who could have had very little to lose."

"I think of nothing," replied the servant, "but fulfilling my trust. I wish now that I had waited and booked passages on another packet. Now, that M. Bernard"—he lowered his voice—"I wish that you, monseigneur, were not so confiding and generous. I wish that I could be sure that this person is a gentleman, a young noble on an important mission. You have noted, sir," he added anxiously, "how he keeps himself apart?"

"I think that that is courteous, tactful behavior. He does not wish to force us to acknowledge an obligation, he does not wish to press his acquaintance upon us."

"I wish I could think so, monsieur."

"Why are you so suspicious of him?" asked M. de Saint-Alde curiously.

He was even a little amused at the doubts the servant had of the young man who had proved such a friend, almost a saviour, to himself and Estienne.

Then the servant confessed that he had been over M. Bernard's cabin when that young gentleman had been on deck and that he had found nothing there to satisfy him that the young man was of noble birth, not so much as a monogram, no sign of a coat-of-arms, nothing marked with a noble name...

M. de Saint-Alde was further amused; this was the first time that he had looked at life from a servant's point of view. Of course, they considered these things; they were always looking out for what he, as a nobleman, took for granted—coats-of-arms, armorial bearings, signet rings, all these trappings and fripperies that perhaps were going to be swept away soon, for ever. He looked thoughtfully at the servant, the good, honest old man who had his own values that nothing would induce him to forsake, and he said kindly:

"One must judge by other details. The young man said he was disguised, on a mission of great importance. No doubt he has been told to be very careful to destroy every evidence of his rank."

"But he should tell you, monsieur," urged Gilles earnestly. "There is no reason why he should keep it secret from you, who are also a fugitive and who bear a name and have a position and whom he cannot possibly mistrust."

This was said so earnestly and was such good common sense that for a moment doubt did flicker over M. de Saint-Alde's mind, but he dismissed it as he had dismissed the strange suspicion that had pierced him when he had looked at the profile of his new friend as they had driven in the coach through the night.

"No, I think he tells the truth, my good fellow," he said at length. "If only for this reason," he added with a smile, "that I cannot see any object for his telling me a lie. Who could he be, and what does he gain by the service that he renders me?"

"Great gentlemen," replied the servant mournfully, "although they may be clever and good men of business like monseigneur, still are strangely unsuspicious. You don't know the lower classes as I do, monseigneur." The servant shook his head.

"I have heard of adventurers who are willing to take advantage of these horrible times. I've learned to be suspicious of anyone who doesn't explain himself clearly. There are spies, too. One can't be over prudent."

The banker agreed that this was reasonable enough, but he added that the young man's appearance, dress and manner did not allow of his being the lowest type of scoundrel, as Gilles would make him out to be, for no one but the meanest of creatures, both in character and in birth, "would attach himself to me at the moment when my fortunes are so fallen that it is not likely I can reward anyone."

To this comment, the old man retorted by asking M. de Saint-Alde straight if he took M. Bernard for a gentleman.

The banker found it difficult to answer this truthfully. In fact the question seemed to him wholly unnecessary. There was something strange about the young man, and he had noted more than once how easily he assumed different characters. But of his tact, skill and cool nerve there could be no question. There were certainly no insignia of aristocracy about the stranger, as Gilles had observed and the banker had noted for himself, yet he did not seem like a peasant or a clerk or indeed a member of the middle classes.

M. de Saint-Alde ended by shrugging his shoulders. After all, what did it matter? Once at Plymouth and they would probably never see M. Bernard again.

He concluded his meditation by saying:

"I think you can put your mind at rest, Gilles. This man—gentleman or adventurer—can do us no harm, and he has already done us a great deal of good. I owe him much gratitude and should not really be discussing him with you."

The servant bowed.

"I am glad to hear your opinion, monseigneur," he said, but he did not seem in the least reassured.

After they had been at sea two days, M. de Saint-Alde began looking out anxiously for the coast of England. As there was no sign of it and the placid horizon was unbroken by the white cliffs that he was so eagerly searching for, he went to the captain, asking him if they were out of their course and how it was in this fair weather that they had taken so long to reach the British coast.

Captain Henlein then informed him, drily, though civilly, that they were not making for Plymouth but for Hamburg. He added that he supposed one port was as good as another to the fugitives so long as they escaped from France, and in this weather the voyage to Hamburg would not take very long and that from that port they might very easily and at small expense remove themselves to England.

M. de Saint-Alde then vehemently reproached him for his deception, and the captain replied by saying that M. Bernard, the man who had engaged the ship, had not been very particular as to which port they made for and that his, Henlein's, port of register was Hamburg and he would not be able to land in England supposing he made for that destination.

M. de Saint-Alde was vexed, though not greatly disturbed. He had his banking connections in Hamburg as well as in London, and he had his ready money and his precious promissory note from M. d'Artois safely on his person. He knew that there were a very large number of refugees in Hamburg among whom he might find acquaintances and friends. Besides, if he did not like the place, no doubt, as Captain Henlein said, it would be quite easy to journey from there to England. Still, the deception was vexatious and he remembered that Gilles had warned him about the young man who had befriended them...on the other hand, he could not see what possible advantage M. Bernard could gain by landing himself in Hamburg. Indeed, if his tale was true, it would be the greatest inconvenience for him, for he was supposed to be bound, with important papers, for London.

He looked out for the young man, and finding him leaning against the taffrail in a melancholy attitude, told him of the captain's action.

At this M. Bernard showed more emotion than M. de Saint-Alde had observed him display before, and remarked passionately that the fellow was a scoundrel and that it did not suit him, M. Bernard, at all to go to Hamburg; he must put in to an English port...

He then went to find the captain, and M. de Saint-Alde, watching them curiously though not with much interest, saw that they were engaged in an animated conversation which seemed likely to lead to a quarrel. The end of it was, however, that M. Bernard returned to M. de Saint-Alde and said that there was no moving the captain from his resolve and they must make the best of their bad luck, only congratulating themselves that they had escaped from France.

"It plays the devil with all my plans," he complained gloomily. "I shall be late for my appointment in London. The first thing I must do when I get to Hamburg is to find out how I can obtain a passage in some vessel going at once to England."

M. de Saint-Alde then asked about the other people who had so kept to themselves during the voyage, and M. Bernard said he had spoken of them to the captain, who had told him they were all Germans, most of whom had been in service in France and were returning to their native country, and that they had known from the first that the vessel was bound for Hamburg.

"It does not seem to me," remarked M. de Saint-Alde good-humouredly, "that you were quite so clever as you thought you were, M. Bernard. You have picked on a dishonest captain and we have been deceived, and possibly swindled, since we paid in advance. It will cost us a great deal more to get to London via Hamburg than if we had gone to Plymouth."

At these reproaches, though so kindly given, M. Bernard seemed greatly disturbed and begged the banker to forgive him. This M. de Saint-Alde at once did; after all, he was not much annoyed by the setback, and he still remembered with gratitude the good services M. Bernard had rendered. They might, but for this stranger's help, be still waiting at St. Malo with every prospect of the "sans culottes" marching on the town, not only to rob them but to cut their throats as well. But there was one who did not take the news so placidly. To old Gilles it was a disaster, a confirmation of his worst terrors.

"It is impossible!" he exclaimed. "Good God, but it is impossible!" when M. de Saint-Alde told him kindly enough that the captain was making for Hamburg and that they were in his hands and it was no use putting up a resistance. "I have promised my master and mistress to bring my young lady to Plymouth. They will be waiting for me there. How am I to communicate with them? How send a letter?"

The old man's distress was piteous; he seemed like one who had received a mortal blow; he existed only to fulfil his trust to his master, and despite his own endeavours he had, as he thought, betrayed that trust. M. de Saint-Alde in vain tried to reassure him. It was not easy to persuade the old Breton, who had never left his native province, that he could send a message from Hamburg to Plymouth, because the banker himself knew that it would be difficult to do this. He urged him, however, to be calm and promised him that if he was short of money he, the banker, would advance him some to keep his young mistress in comfort until he could communicate with his master. But the old man's distress was not to be assuaged; it rose instead into a rage. He declared that this M. Bernard was a trickster and an adventurer and had betrayed them all.

"Don't you see, monseigneur, it doesn't suit him to take us to Plymouth. He doesn't want to be unmasked. You'd soon find out when we were in England that he was no Royalist spy or messenger. He wouldn't be able to keep the game up there, he would have to prove who he was or disappear—and it wouldn't suit him to do either."

"Hush," said M. de Saint-Alde, "I am sure you are wrong. The young man is indeed as angry as we are, and remember the conditions at St. Malo. It was not easy to get passages at all."

The banker then took the agitated old man by the arm and led him away to his small cabin.

"I beg you, my good fellow, to take this setback quietly. I am responsible for my daughter as you are responsible for your mistress. They are two young girls, almost children, they have only us to protect them, and this M. Bernard. And, according to you, he is not to be relied upon. The captain is a German, the crew and those other passengers are German, or Swiss. They will have no sympathy with our desire to go to England; it suits them to go to Hamburg. You will understand, then, that we are helpless, and if we make any protest, disturbance or quarrel, we may find it very much the worse for us. I don't mind telling you that I carry a very large sum of money and I suppose you have a few valuables. These people, who have deceived us once, might attack us and rob us if they had the least provocation."

Gilles listened but did not seem to comprehend this good advice. He stood with mechanical respect before M. de Saint-Alde and, when that gentleman had finished, went with a stumbling gait out of the cabin; the banker followed, afraid that the old Breton would not be able to control himself.

Seeing the captain going up to the bridge, Gilles stopped him roughly, called him a scoundrel to his face, and pulling out a pistol that he had stuck in his belt, pointed it at him, declaring that he would have the boat turned towards Plymouth or shoot the man where he stood.

Captain Henlein had been prepared for something of this kind from one or other of his passengers and he was ready for it. The old man, strong as he was for his years, was no match for the stalwart German, who disarmed him by striking at his wrist, sent the pistol spinning down the deck and over into the sea, and then laid Gilles low by a blow to the chin. With that he passed on to the bridge, looking right and left as if to warn any other malcontents of the punishment that was likely to await them. M. de Saint-Alde called out for help, and two of-the crew lifted the fallen man and carried him down to his cabin, while the banker protested violently at the treatment meted out to the poor old man. The sailors, however, affected not to understand French. But presently a tatterdemalion kind of fellow who declared he was the ship's doctor came to examine the unconscious man. He spoke a few words of English, with which M. de Saint-Alde had a slight acquaintance, and informed him that Gilles was suffering from a stroke, apoplexy—some kind of fit.

"He is too old, he should not have come. He should have stayed and taken his fate. At his age one cannot run away from death."

So, with a leer, the self-styled physician, for M. de Saint-Alde believed he was nothing of the sort—left the cabin.

It was useless for the banker to call after him that the man was not suffering from a fit but from the results of the blow from the captain; M. de Saint-Alde felt that he was cornered, that the so-called doctor had been put forward to give evidence on the part of the captain so that there might be no fuss or possible inquiry when they reached Hamburg.

'As if we could do anything,' thought M. de Saint-Alde bitterly. His transient and superficial high spirits left him as he realized the desperate position he was in—a man who had lost his rank, his country, his citizenship, a man whose word would not be taken against that of the rascals on board the Sachsen...they would say he was a refugee, a Frenchman flying from his own country, a criminal for all they knew, whose passports were false perhaps.

The distracted banker turned back to the cabin. The old man was still unconscious. Perhaps it was true, perhaps he had had some kind of fit from the shock of being felled by the heavy fist of the German captain. His features were drawn and congested, his eyes half-open. There was a wound on the back of his head, blood was congealing in the stiff white locks.

M. de Saint-Alde kept watch by him, giving him such medicines as he knew how to administer from his own travelling case—restoratives, and fresh bandages for his wounded head.

Once or twice M. Bernard looked in. He seemed deeply moved by this wretched incident, but warned M. de Saint-Alde with what the banker admitted was good common sense not to thwart the captain further.

"There's nothing to prevent the wretch murdering us all, throwing us overboard and stealing our luggage. As no doubt he would de if he knew the valuables we carry."

At that moment the banker felt that the valise full of gold, which he had thought of hitherto with such satisfaction, was a curse; remembering his daughter he winced with alarm.

Gilles recovered his senses for a few seconds; grasping with feeble, contracting fingers the warm plump hand of the banker, he tried to make a gesture towards the corner of his cabin where his small portmanteau stood. His withering lips endeavoured to form two words: 'the demoiselle'...

"Yes, yes, I understand! I promise!" said M. de Saint-Alde. "I will look after the young lady. I will give her your property, your papers, everything you have. I swear to you, by God"—he raised his hand and spoke solemnly—"I will do all in my power to keep the pact you cannot, and deliver Mlle Vivienne to her parents."

He did not know if Gilles had heard or not; the old servant sank into a stupor and before morning was dead.

The captain came to look at the body, by which M. de Saint-Alde still sat. He was not a religious man, but he had been on his knees, praying. The Breton had died without the last rites and consolation of his Church. That had been his final and supreme sacrifice to the family he had served so faithfully.

The captain repeated what the ragged-looking doctor had said—that the old fellow had died of a fit; he should never have undertaken the journey at his age. Then the body was sewn up in a tarpaulin and without ceremony cast into the sea, weighed down by two lumps of lead, the price of which Captain Henlein demanded from M. de Saint-Alde.

All the banker's energies were now concentrated on keeping the news of the tragic and unexpected death of her only friend and protector from Mlle de Vernon.

She shared a cabin with his daughter, and on the dawn of the day that Gilles died, M. de Saint-Alde, exhausted and overwrought, went down the passage to the cramped cabin, opened the door cautiously and looked in.

The two girls were asleep on the one couch, their arms lightly flung one over the other, their plump faces side by side. A dear friendship had sprung up between them, because of the similarity of their situations, their ages and their loneliness. The light, reflected from the water, beginning to glisten in the glow of the dawn, shone through the porthole on their closed eyes, candid brows and parted lips.

M. de Saint-Alde, who had thought so little of his own daughter in his crowded days at home, was now deeply moved by the sight of this youthful innocence. Neither of these girls had any protector, at least under the present circumstances, except himself. He hoped that he would be able to save them from all harm and indignity.

He noticed that on Mlle de Vernon's face were traces of tears. He remembered that she was not, like his own daughter, leaving a school with a neglectful father, but that she had been taken away suddenly and, as it were, violently, from a home where everything was dear and charming, from parents whom she passionately loved and who adored her. He noticed, even through his tender and poignant solicitude, the beauty of the girl who was, he had been told, but twelve years of age. Unlike those of his own daughter, her features were carefully and delicately formed. Her hair had that fair colour which was neither gold nor auburn nor silver but rather the hue of new cedarwood, and fell in smooth, heavy loops like bands of ribbon either side of her face and on to her shoulders.

The girls had not undressed; they wore their muslin day gowns, their pelisses spread over their feet, their sandalled toes showing from the edges of the garments. No blankets had been given them and it was cold on the water.

'I must,' thought M. de Saint-Alde, 'keep the news from her while she is on the ship. That will be difficult, but when we reach Hamburg it will be easier. I shall say that Gilles has gone ahead to find rooms. I shall take her to stay with me and Estienne, and then I must tell her that Gilles has gone ahead to Plymouth—I don't know, some tale to keep her quiet. The poor child! God save and protect us all!'

He closed the cabin door carefully and went in search of M. Bernard.

That young man was now composed, even cool, in his demeanour, and M. de Saint-Alde had ceased to ask himself whether he was an adventurer or a Royalist in disguise, a gentleman or a commoner. He was a fellow Frenchman, one who had professed friendship for him, and they stood together under peculiar, perhaps perilous, circumstances.

He told him of the death of Gilles and of his own undertaking of the guardianship of Vivienne de Vernon, and of the kind deception he meant to put upon her.

M. Bernard agreed at once to all these schemes; he declared he would be a party to them and do what he could to help look after the child and to distract her from the loss of her guardian.

This kind plan proved not very difficult of execution, for Vivienne de Vernon became slightly seasick, and was unable to leave her cabin.

Estienne waited upon her tenderly, and so absorbed were the two girls, one in her own malaise, the other in her new duties as nurse, that they never thought to question where Gilles was.

When Hamburg was reached, Vivienne had somewhat recovered, but her eyes were unnaturally bright, her cheeks flushed, and she was a little dazed and bewildered as the other girl, on whom the motion of the ship had had no effect, helped her onto the deck.

Captain Henlein did not prove to be the complete scoundrel that M. de Saint-Alde had suspected him of being. Grateful, perhaps, that no inquiries were made into the death of Gilles, he gave his French passengers all possible assistance. He explained to the customs-house authorities how it was they had landed in Hamburg when they intended to go to England, smoothed over passport difficulties, and made no effort to detain, as M. de Saint-Alde was fearful he would, any of the baggage.

Henlein, who seemed to consider himself a hero for saving so many refugees, recommended to them a hôtel on the outskirts of the town, which he swore was occupied by honest, respectable folk. It was a place, he emphasized, where the young ladies might safely stay.

All this passed in broken English and such few words of German as M. de Saint-Alde could muster, for M. Bernard appeared to know no German whatever, and if he knew any English he did not bring it forward, but stood apart during these negotiations.

"I suppose we'd better go to this hôtel," said M. de Saint-Alde doubtfully, looking at the two girls sitting together on the valises, which had been placed on the quay. Vivienne had begun to miss Gilles and was crying softly on her friend's shoulder. The banker endeavoured to reassure her timidity.

"Your steward, your friend, mademoiselle, has gone into the town on some business," he explained lamely. "You must come with us, we will look after you."

"Yes," said Estienne, "you must be brave. We are not in England after all, we are in Germany; but we are safe."

"But it was at Plymouth I was to meet my father and mother, they will be waiting for me there!"

"Never mind, dear, we can send them a message. I believe Plymouth is quite near to Hamburg, isn't it?" Estienne looked imploringly at her father.

"Yes, yes, everything will be all right. You must not grieve yourself, my child."

He patted Vivienne kindly on the shoulder, then looked at M. Bernard, who was standing, motionless and silent, his hands clasped behind the long skirts of his green, many-caped riding coat, looking down at the two girls with a strange expression on his face. Was it a calculating look? M. de Saint-Alde wondered. Or was it pure compassion?

M. de Saint-Alde turned to the taciturn young man.

"Monsieur, I owe you a great debt of gratitude. I am afraid I cannot repay you at the moment. There is really nothing I can do for you in this strange city. But I remain deeply obliged to you. I shall be at your service in the future if ever I can repay."

He waited rather awkwardly at the end of this formal speech, expecting the young man to take his leave; but M. Bernard gave him a quick glance and said with a dry smile:

"I am afraid, monsieur, that you can oblige me, and immediately. I am penniless. I was to have met someone at Plymouth who would have given me money. I know no one in Hamburg. I am afraid I am dependent on your charity." He glanced at the valises as much as to say, 'I know that you have plenty of money, and in the most desirable form—gold.'

Instinctive breeding made M. de Saint-Alde reply at once: "But naturally, monsieur, what I have is at your disposal."

But his own fleeting suspicions and the clearly defined denunciation of poor Gilles occurred to him, and he added quietly: "Of course, sir, being, as you have said, a gentleman of rank and on Royalist business, you will be able to produce your credentials to some banking house here. You will be able, no doubt, among the refugees with which the place is, I understand, crowded, to find some friend or acquaintance. I can hardly suppose that one who is a Royalist messenger will be without resources in the city of Hamburg."

The young man's expression did not change.

"There are a large number of people who would stand guarantors for me if I cared to reveal my name," he said, "but at present I am under pledge not to do so. But if it is inconvenient to you, monsieur, to lend me a few livres—"

M. de Saint-Alde interrupted at once.

"I cannot unstrap the valises on the quay. Perhaps you will be good enough to see if you can hire a carriage and come with me to the hôtel that Captain Henlein recommended."

Despite his apparent ignorance of the German language, M. Bernard was able to secure a vehicle. The driver was told the name of the hôtel, and the two men and the two girls entered the carriage, with M. de Saint-Alde fervently commending himself to the many saints whom he had since his childhood forgotten.

The worst of his fears were not realized. The hostelry proved a pleasant enough place. It was a posting-house on the highroad, with a large beer-garden attached where tables were set out under vines already rusting and dusty from the summer heat. The rooms were large, cool and clean; according to M. de Saint-Alde's standard it was peasant accommodation, but he was thankful to have it and so easily.

The good woman of the house was all sympathy for the forlorn and tired young girls, and it was impossible to doubt her good faith and her good will as she mothered them up the wide, shining stairs to the best room the place afforded, followed by a stout chambermaid bearing hot water and clean towels.

The care of the two girls being thus for the moment off his mind, M. de Saint-Alde asked M. Bernard into the room he had chosen for himself.

Peasant accommodation indeed, but a pleasant place, and it stirred some nostalgia in his heart, as if once, in his long-lost youth, he had stayed at such a place and loved it...perhaps at his foster-mother's cottage in the South...he did not know, and put the thought from his mind.

The oak floor sloped to the door and was dark golden, shining from beeswax, and gave out a pleasant odour. The windows were latticed, and fide linen curtains, hand-worked with a blue design, were drawn across the midday sun. The vine leaves without made a moving pattern of shade on this white linen; similar curtains were at the bed tester; the coarse coverlet was white and fragrant.

Lulled by the smell of herbs and lavender M. de Saint-Alde felt far away from Paris, its mud-coloured streets, its processions and torchlight and drum-beats, the hot, dirty pavements, the excited slatternly mob and the guillotine and those pools of coagulating blood running between the cobbles that one came upon now and then. Yes, far away from all that...

He looked down at the valises with a sigh of relief. There was enough money for himself and the two girls he had under his protection to live quietly for some while. He felt a pang as he looked at the modest valise that had belonged to Gilles, the Vernons' servant...The banker did not know what was in it; no doubt some money, perhaps jewels as well as papers. He must make an inventory of them and seal the property up until he could hand it over to M. de Vernon.

But now his business was to appease M. Bernard and get rid of him. Get rid of him—the phrase had come into M. de Saint-Alde's mind without his being aware of it. He did not want to admit that his regard for the young mars was tainted with suspicion. No, all that M. Bernard had said was just and reasonable; yet M. de Saint-Alde would not be sorry, now that he was in a friendly city, among honest people, to see the last of the slightly mysterious stranger.

He asked him, civilly but somewhat coldly, what were his immediate needs until he could present his credentials and obtain funds.

M. Bernard asked for fifty louis d'or and M. de Saint-Alde counted this sum out, thinking to himself that there were fifty louis d'or less in their entire fortune...and that when this gold came to an end—he did not like to pursue the thought. Of course, by then they would have left Hamburg and be in Plymouth. He wondered what the fares to Plymouth would be, wondered what connections he could establish in Hamburg, if after all he would find friends and acquaintances there.

He shut his mind away from these thoughts. His plump, well-cared-for hands did the unusual work of unstrapping the valise and counting out the rouleaux of gold louis d'or.

He again gave formal thanks to M. Bernard for all his services and wished him luck on his mission.

The young man bowed very courteously and took his leave, without any comment on the future or expressing any hope that he would meet M. de Saint-Alde again.

The banker, to his own surprise, distinctly felt a weight lifted from his heart. 'That poor old Breton—servants are always superstitious—has poisoned me against the young man,' he thought. And then he put the whole incident out of his mind, for his cares were immediate and pressing. The welfare and future, the safety and dignity of the two girls, and how to break to Vivienne de Vernon the news of the death of Gilles, and her own isolation from her parents; together with the difficulty and perhaps the impossibility of communicating either with. Brittany or with Plymouth.

He felt now acutely his lack of practical knowledge of the small, necessary details of life—secretaries, stewards, valets, all manner of servants always arranged these things for him. He did not know, for instance, what would be a reasonable charge for the keep for the three of them in a place like this. The first thing would be to find out a bank and get the French gold changed into German currency. No, the first thing was to see that the money itself was safe. There was a large press in his room, big enough to hide two or three human beings, and into this he put his valises, then emptied all the gold into one, locked that, locked the press and put the key into his pocket. Even then, should the least suspicion that he had so much money with him leak out, it was possible for him to be robbed, no doubt murdered too. The place seemed pleasant and honest enough, but there must be bandits about here as in any other country. It was a posting-station also, which meant that the mail coaches would be coming and going, passenger coaches, too, no doubt. That beer-garden would be a meeting-place for the riff-raff of the town...

M. de Saint-Alde looked at himself in the mirror that hung above the toilet-table, and he was amused despite his poignant distress—for he was a man with a delicate humour—at his own appearance. He would scarcely have recognized that flabby face streaked with sweat and dust, the hair in which pomade and grease stuck in ugly patches, the soiled cravat badly knotted, the salmon-coloured satin waistcoat stained and creased, the plum-coloured coat that seemed suddenly to have become wrinkled and ill-fitting. Never before in his life had he gone so long without his clothes being attended to. He had thought before he left Paris of buying himself a republican outfit, trousers and a tailed coat, but there had not been time. Now he would have to buy suitable attire—that was another expense.

The girls, too, what had they with them? Very little, probably. He smiled again to think how he was daunted by these small problems—he, the man who had dealt with high finance, given loans to exiled Royalty and bribed a whole Convention.

He took out his case of pistols and opened it, looking keenly at the weapons. They were handsome, of ebony and mother-of-pearl, engraved with his coat-of-arms and his marquis's coronet. Then he closed it up—the weapons were too rich, they might excite envy. He unlocked the press again and added the case of pistols to the valise full of gold. His movements were full of caution.

Life was not going to be worth living like this, always suspicious, alarmed. He must buy a plain weapon for his ordinary protection—that would mean another outlay of money. His sword, too, he had kept with him; it was a dress weapon, also rich, worth a good deal, no doubt. And again his arms were engraved on both the blade and scabbard. Should he wear it about Hamburg, would it be conspicuous? He ended by hanging it up in the cupboard on one of the pegs for cloaks. He would buy a plain sword as well as a plain pistol.

When he unpacked his case of toilet articles in gold and ivory, also with his crest, he was struck as he had never been before by their costly look. In his Paris hôtel they had seemed just part of the furniture, in this room they seemed out of place. They, too, were locked away.

He had some jewellery, opals and emeralds—a great deal had been left behind, but something had been brought with him. These, too, he looked at and they also were locked away.

There was a large fortune now in the press; he had to find an excuse for never opening it when the chambermaid was about. After all, perhaps these people were simple and honest, but he must soon move with his treasure and the two girls. They must hire a house somewhere, but what of servants? Some stupid peasant woman, perhaps, would come in and work for them.