RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by John Varley (1778-1842)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by John Varley (1778-1842)

"Hidden Saria," John Heritage, London, 1934

Title Page of "Hidden Saria," John Heritage, London, 1934

Frontispiece.

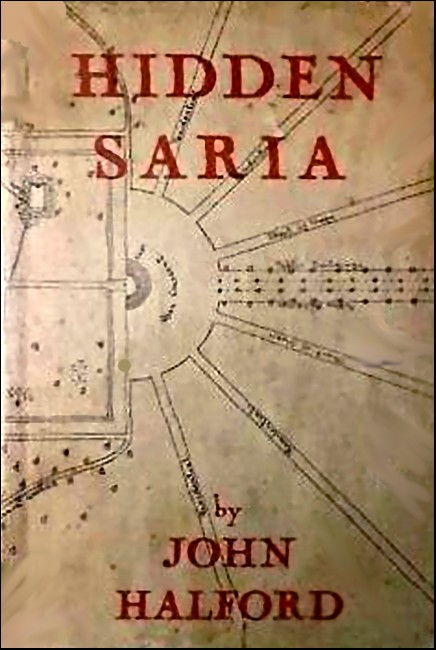

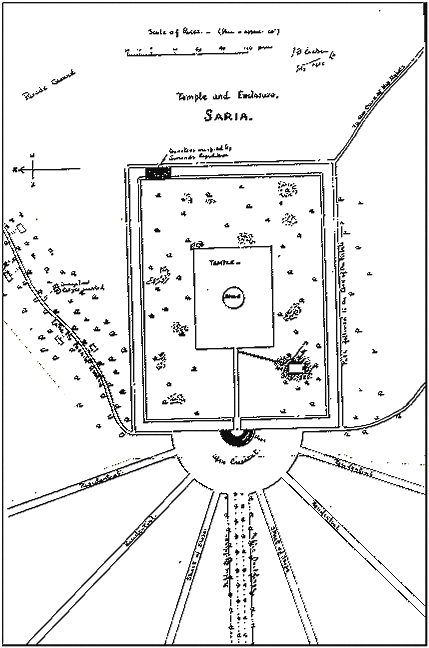

"Hidden Saria," Map of Temple and Enclosure

THAT I ever heard the story at first hand was sheer luck. I had been granted eight months' leave home and, on taking train to Bombay, I found as companions in the same compartment Major Simonds and Lieutenant Erskine; the former I had met when he joined "Intelligence" on the Frontier, and young Erskine I had known well for the last two or three years—in fact, from the day that his regiment had moved into quarters at the station which was the centre of my activities.

As the train started I remarked that a long time had passed since I had seen either of them; then that I wondered if Jerks Erskine had somehow achieved permanent leave, as I knew for certain he had not been near his regiment for about a year, and I had not heard of his being seconded; I continued that, when I came to think of it, Terrant, his alter ego, had disappeared at much the same time and had never shown up since; and that really this strange series of facts needed investigating.

Erskine looked across at Simonds inquiringly and, after a moment's hesitation, mumbled something about language leave. But Simonds cut in—and I can still clearly recall his words, "Now look here, Halford; you're of a nasty, suspicious nature and I don't trust your inquisitive habits an inch; if we'd had any luck at all we'd never have met you now,—and you'd never have thought of us otherwise. As it is, I can't have a bloated newspaper man nosing about our doings: I believe you've got some decent instincts somewhere in your make-up," and he smiled quite nicely, "so we'll tell you a story that I think will make you sit up;—but only on condition that you will give your oath never to repeat or refer to it in any way without permission from one of us. Political and personal interests are involved,—as you will soon see for yourself. I admit to you quite frankly that I'm afraid you may hear rumours which you will make a pretty story of; so I propose telling you the truth and stopping you in that way: how about it?"

I never noticed that long and boring journey from Peshawar to Bombay. I listened to a story that held me from beginning to end: at times, mentally halting at hearing such things, and then breathlessly catching up the narrative with the remembrance that it was Major Simonds who was coldly relating these events; events such as are incomprehensible in these days of mechanical civilization.

Later, on the boat, I took extensive notes: here, after a lapse of over twenty-five years, is the result.

"OH draw it mild, Jerks!" Terrant exclaimed. "That's all rot and novelists' romancing of the East: for instance, we have all heard the yarn about the conjurer who throws a rope up into the air and a boy climbing up the rope until he disappears into the sky; then the rope falls down, or something, and the boy is found in a basket: but I ask you,—have you seen the trick yourself or have you ever met anyone who did?"

It was during the cold weather, at Fateybad. After an excellent dinner at the club, Major Simonds, Captain Terrant and Lieutenant Erskine sat round the fire and the conversation had turned to the mystical legends of the Orient.

Major Simonds is a typical Anglo-Indian of medium height, wiry and sun-baked, not strikingly remarkable to look at except as an example of what he is,—one of those fortunate, inexcitable men who refuse to be hustled; he thinks before he speaks, and when he acts he means it: a bachelor of a kindly disposition, his interests are confined to his profession and the varied relaxations—sport, games and good-fellowship—that are part and parcel of it.

Captain Terrant is of a very different type, being decidedly good looking, tall and strongly built, one might almost say massively so: his piercing grey eyes and determined chin loudly proclaim a steady, purposeful disposition and a mind that is hard to change from any preconceived idea: he is worshipped by his men and is a joy to his brother officers: the fair sex he shuns and, on this account perhaps, is all the more sought after by its members.

John Erskine, known to all and sundry as Jerks—a name that exactly fits him—a devil-may-care subaltern: usually in trouble over some escapade or other, he is at all times in love with, and making desperate love to, three or four fair ones who, for a few weeks or months, divide his attentions until succeeded by a batch of fresh charmers. Tall and, be it said, lanky, his best friend could not call him good looking, but his cheery grin, his inane remarks and infallible good humour are more satisfying to a companion than could be any regularity of features. He is "Jerks" to all and the gay recipient of the chaff and leg-pulling that are usually his lot.

All three are officers in the 52nd Indian Cavalry, but for some years Major Simonds has held a billet in the Political Department of the Civil Service; now, on a few days leave, he is spending Christmas with his regiment.

Having discussed the latest regimental and station gossip, Simonds commented on the extraordinary rapidity with which news was spread amongst the natives, and described how he had lately been investigating a serious leakage of information from the Intelligence Department.

All babus—or native clerks—involved had been watched, and their correspondence examined, but without result; it was impossible for subordinates to use the government telegraphs for their purpose, and yet it had been conclusively proved that decisions arrived at in Calcutta, and known to two or three officials alone, became public property in the bazaars of Peshawar within six hours.

Erskine had informed his hearers that he could easily describe the method employed by the natives,—that it was simply a case of telepathy or possibly a projection of the soul or subjective mind: and it was this highly coloured explanation that brought forth Terrant's emphatic rejoinder.

But Simonds was not of the same mind;—"Since when has Jerks been numbered amongst the prophets? After all, Terrant, leaving the rope story out of the question, we must all admit that telepathy is a fact and that in such matters we of the West are ignorant babes compared with the oriental: we cannot say that such an explanation is ridiculous; clairvoyance and clairaudience are now, even in England, admitted to be possible, if not established as facts; and there is no doubt that if such things are possible, Jerks' theory would explain the mystery."

"Good heavens, Major, how many drinks did you accomplish before we joined you this evening? We shall have you starting a table-turning society next! Just because a few old gentlemen, with nothing better to do, get some hysterical lady to act as a medium and insist that she is talking to or receiving messages from somebody's maternal great aunt, it does not prove that these high-sounding delusions are facts. Have you ever, yourself, come across an indubitable case of clairvoyance or clair-what-did-you-say?"

"'Clairaudience',—that is, hearing things taking place at a distance, beyond the range of human ears. Yes;—a cousin of mine is clairvoyant, and I have been with him at times when he has, in his normal state, seen things that were happening at that very moment at a place two or three hundred miles away!"

"And look here, Terrant," said Erskine, "I think we all suffer from occasional lapses into a form of clairaudience; haven't you ever started whistling or humming a tune—perhaps even in the middle of a verse—and then been told by the person you were with that that very tune was just passing through his mind? In such cases I always think that my brain hears the tune in the other chap's brain and joins in,—if you understand what I mean."

"Yes, my son, I understand what you mean, but I can't say that I agree with you: I think that it is merely coincidence, or some remark has turned the thoughts of both of you into the same channel:—clairaudience, my aunt!

"As for this leakage of official secrets, we all know what wily brutes these natives are; they probably have holes in the walls through which they can listen to what is going on inside a room; and once they have got the news they want they can surely find some way to telegraph it,—either by code or by bribing a telegraphist or both; it's quite possible, isn't it, Major?"

"No, Terrant, I don't think it is: naturally that explanation was the first one we investigated, and no stone was left unturned to discover such a solution; but it was quite impossible with the precautions we took: on two or three occasions we did not speak a single word, but wrote everything, and still the result was the same. Well, it's no use arguing about it, we won't get any further. As for the rope yarn,—I never saw the trick myself, but I think that somebody must have, as the story is so generally known: I think that in that case the conjurer is a very skilful hypnotist, with the power to hypnotize a crowd:—you can't deny the fact of hypnotism, can you?"

"No; perhaps that is possible," Terrant admitted, "but the rest of your theories are a bit too steep for me!"

"Where are you two taking your leave next hot weather?" asked Simonds. "As a matter of fact, one of the reasons for my taking my Christmas leave here was to suggest that if you haven't got any very definite plans you might care to come with me. Rumours are coming through from somewhere far beyond the north-west frontier of some marvelous oracle or deity! Very vague of course, but I believe it is supposed to be a very beautiful goddess,—that ought to suit you, Jerks,—and there is a little uneasiness at headquarters about some of the lady's rumoured intentions. I have been told, unofficially, that if I cared to go and investigate the matter I could have leave for an indefinite period; I would have to take a couple of chaps with me, and no doubt I can choose who they should be. What do you think about it?"

"Just the thing for me!" Erskine exclaimed. "I am sick of cantonments, and roughing it for a year or so would suit me down to the ground: besides which—I've never met a goddess before, and of course one can't expect to get on in one's profession without experience, can one?"

Terrant hesitated a moment and then replied undecidedly; "I was rather thinking of starting to work for interpretership in Russian, but perhaps an exploring trip in that direction might be more valuable." Then coming to a decision, he added, "I'd like to go too, if only to keep Jerks in order; with his everlasting philandering he'll probably get the expedition into trouble, but I suppose we will have to risk that. Yes; I'll come; and we'll have a jolly good shot at exposing the oracle,—probably some rather crude conjuring trick: when do you expect to start?"

"Well, we ought to push off into Kashmir in April, as soon as the snow melts enough: I'm glad you two will come with me. I know we shall pull well together—we always have. I will let you know as soon as I hear from headquarters about your leave: of course, you quite understand that all this is absolutely confidential, not a word about it to a living soul,—we don't want to have our destination advertised: make out that we are simply going to shoot in Kashmir!"

MAJOR SIMONDS, having obtained Terrant's and Erskine's consent to join the expedition, curtailed his leave and returned at once to Calcutta. Before starting, however, he told them that he would make all necessary arrangements for their leave, and again impressed them with the necessity of complete secrecy about the trip: he advised them to write to their relations in England that they intended to go off for a three months' shoot in Kashmir in April: then, just before leaving the outskirts of civilization, they would send back a runner with letters telling of their change of plans and that they were going on an exploring expedition into the interior, whence they might not be heard of again for one or two years.

Erskine was, quite naturally, vastly excited over the prospect: to him it appeared to be a great compliment, being included in an important mission, notwithstanding his youth and inexperience. He frequently discussed the journey with Terrant and referred with glee to the goddess; he had already endowed her with all the beauty in the world, and his solemn conjectures as to whether her hair was golden or Titian coloured, her eyes violet or green, afforded Terrant hours of amusement.

The latter had long ago given up all attempts at persuading Erskine that there was no such being as the goddess or that, even if there were one, she was probably some ancient and hideous hag—such arguments were a futile waste of time. He now humoured him and, if he did not prove of much value in deciding those knotty points of detail, at any rate showed his patience and good temper by listening or appearing to listen intently to Erskine's sole topic of conversation.

Terrant also looked forward to the expedition with pleasure, as he anticipated obtaining information about the country beyond the frontier that would be useful to him in the future: he was also scientifically interested in the types of tribes likely to be met with and wondered whether, at their destination, the people would be short and stocky like the Gurkhas, or whether they would conform more to the tall and rather Jewish type of the Pathans and Afghans.

His interest in the rumoured goddess was practically nil, and he expressed his true opinion to Erskine when he said that she was probably old and horrible.

Being well occupied with their regimental duties, time passed quickly for both of them: after a few days Terrant had received a letter from Simonds instructing him and Erskine to apply in the usual way for three months' leave from April 1st, he informed him that this would be granted and that they would also receive, direct from headquarters, a letter granting them an extension of leave for an indefinite period.

The major told them to join him at Rawal Pindi on April 2nd, where they would find him busy completing the arrangements and equipment for the expedition.

In due course matters fell out as foretold: they were publicly granted their three months' leave and privately received permission to travel for as long as might be necessary for their purpose: and now but four days were to elapse before they should start to Pindi,

It was Sunday morning and Erskine joined Terrant, as was their habit, for an early morning ride: he found him unusually silent and inattentive; all attempts to rouse him proved unavailing until finally he asked him point-blank if there was anything wrong. Terrant's reply startled him;—he said, "No, Jerks old son, I'm not ill and there isn't really anything wrong at all; the fact of the matter is I had an odd dream last night and, for some reason or other, I can't get it out of my head!"

"An odd dream! Out with it, old man! I'll do the Joseph stunt and interpret it for you!"

"I don't think there is any interpreting necessary, and it's ridiculous of me to think about it at all, particularly as I never did have much truck with the ladies."

Erskine raised his eyebrows and grinned at Terrant, who continued, "It's all very well for you to smile, but it is probably entirely due to you and your ever-lasting drivel about your goddess. As a matter of fact I dreamed that I suddenly woke up, in bed, in my bungalow, and—"

"You dreamt you woke up in your own bed!" Erskine interrupted. "Probably it wasn't a dream at all; probably you did wake up!"

"If I did wake up, that makes it all the worse! But you listen! Well, as I said—I dreamt I woke up and there, just beside my bed, I saw a faint, hazy light which gradually took the form of a woman; she was marvelously beautiful—wonderful—and she just stood there and smiled at me!"

"Jiminy!" interpolated Erskine.

"She was in the midst of a sort of glow of very white light—rather as if she was standing in a beam of limelight, you know what I mean—and her hair shone like burnished gold. Her face,—well, it was amazingly beautiful, but I chiefly saw her eyes; I was held by them and they seemed to draw me towards her, helpless, with outstretched arms."

"Oh mother!" said Erskine.

"Suddenly, when I almost touched her, a great white cat appeared upon her shoulder, spitting at me and arching its back: I was so startled I fell back on my bed and the fall must have awakened me. It was a dream, but even now I hate that cat!"

During this recital every shade of amazement had passed over Erskine's face; he now burst into hoots of laughter, exclaiming, "Terrant, old egg; I always said you'd get it bad some day; but I wouldn't worry about a dream-fairy if I were you; they may be beautiful and all that but they're deuced unresponsive—if you know what I mean!"

A slight flush of annoyance passed over Terrant's face, but he finally accepted Erskine's hilarity with an air of resignation, only remarking, "Oh all right, laugh away; I suppose it is a bit of a joke,—but for heaven's sake keep it to yourself!"

Terrant so evidently wished the subject to be dropped that Erskine said no more about it and, rather silently, they returned to cantonments and breakfast.

On the following Thursday they entrained for Rawal Pindi.

Major Simonds met them at the station and naturally enough was immediately inundated with questions as to the progress he had made with his preparations; he refused, however, to give any answers until after dinner, but escorted them to the club, where they had a badly needed bath, and shortly afterwards joined him in the dining-room.

After dinner, over coffee and cigars, Simonds told them how he had collected the necessary mules and porters, light tents, tinned provisions and other necessaries.

He congratulated himself upon having succeeded in obtaining the services of a fine Sikh, Hernam Singh, who had joined the expedition in charge of the transport; this man had been for many years a native officer in a cavalry regiment and in that capacity had seen much active service on the frontier: he was thoroughly reliable and should prove invaluable to them.

On the previous day Hernam Singh had started with all the heavy baggage and the whole of his command to Srinagar, where he would await the arrival of the remainder of the party.

The major explained how he had been greatly assisted in his preparations by a native merchant named Moti All, a member of the secret service, through whose agency many of the rumours of the oracle had reached headquarters: he had helped collect the mules and had carefully chosen the porters, only engaging men whom he knew to be quite trustworthy; he had supplied all the equipment,—in fact it was really he who had formed the caravan.

Now they must wait two or three days in Pindi until a man should arrive who would be able to give them the latest news of the country of their search, and who might act as their guide.

Having discussed the few articles still remaining to be procured, and anticipating a heavy day's work before them, they retired early to rest,—all in the best of spirits and only anxious to be really on their way.

Two or three days passed rapidly, during which time all final preparations were completed, but still no word had come from Moti All concerning their guide: then their patience was sorely tried by a few days of idleness; at last, however, the time of inaction came to an end, and one night they were called by a messenger to the merchant's premises.

They passed quickly down the main street of the bazaar, but it was not to the shop that their guide led them: just before they would have arrived there he turned sharply down a narrow lane and they followed him, momentarily blinded by the sudden intense darkness. Very soon he stopped and whispered to them that Moti All had thought it best that the meeting should take place in the security and quiet of his private house, at the back of his store; and that while there was no particular reason for this precaution, on the other hand it would probably be just as well not to advertise this meeting by night; it could only cause talk and conjecture in the bazaar—a most undesirable eventuality.

Simonds muttered his agreement and they proceeded slowly onwards, stumbling sometimes over the uneven surface of the alley and silently cursing as they collided with one another: they turned another corner and soon were brought to a halt before a narrow doorway let into the blank face of one of the confining walls. By this time their eyes were accustomed to the faint light from the stars and from the glow over the nearby, busy street, so that they could perceive that they were in a typical alley of a native city—narrow, odoriferous, meandering between close walls that here and there showed by darker patches where were doors giving access to the secrets of the sinister houses.

Their guide gently tapped at the door, which was immediately swung inwards and held open by a tall, muscular-looking man: a few whispered words and they all entered a small courtyard and thence a room on one side, from which streamed a cheerful light.

Moti All awaited them there and welcomed them into a chamber that well-nigh dumbfounded them by its contrast with the squalor of the lane through which they had just passed. The room was large, comfortably lofty and softly lighted by massive lanterns hanging from the ceiling: along three sides stretched low divans heaped with cushions and covered with dull-coloured silk spreads; on the walls and floor were exquisite Persian rugs and in front of the divans low, carved, Kashmiri tables.

Having disposed his guests in comfort, Moti All summoned a servant, who brought to them Egyptian cigarettes and coffee that quickly filled the room with its fragrant aroma: he then explained that Yusuf Khan—the Pathan who had but lately returned from a trading and spying trip in the neighbourhood of their destination—had turned up that morning and should arrive for this meeting at any minute; moreover, he had seemed to be willing to accompany them as guide.

Moti All then settled down with them to await Yusuf Khan's appearance, meanwhile discussing the latest news and rumours from beyond the frontier, trade and ponies and bazaar scandal. He was a knowledgeable old man and kept them thoroughly entertained;—his intimate and detailed account of how Nao Roz, that amazingly beautiful young lady from Persia—courtesan, yes, but famed as well for her skill, her technique in the nautch, conversation and poetry—how Nao Roz had hoodwinked her wealthy, royal supporter while enjoying herself with her young, English subaltern lover was worthy of "Punch",—if it were modelled on the lines of "The Thousand Nights and A Night".

They were suddenly startled by the sound of scuffling and guttural words bitten off short and spoken low: in the silence that instantly fell they listened tensely until, with a bound, Terrant sprang from his seat and out of the door. Galvanized to action, the others followed him—a mere second or two later—but already Terrant had torn open the door into the alley and was disappearing into that darkness with the door-keeper after him. And as they halted in the courtyard, instinctively, to decide whence came the sound that had stirred them to action, from over the wall came a horrible gurgle that ceased abruptly.

But Terrant, arrived almost without, and as quick as thought, in the lane, saw a writhing, darker mass in the gloom and charged into it: and at that moment the same gurgle assailed his ears. On the outskirts of the struggle that proclaimed itself he stopped to decide what part to seize or hit and then was able to discern two struggling bodies bending over a shapeless blur beneath them. He grabbed for what he thought were two necks, drew them apart and crashed together with all his might what he hoped were two heads:—his hope was fulfilled; the heads met—unmistakably; and two bodies hung limp in his hands to subside into the dust when he released them. Then a portion of the blur on the ground rose swaying to its feet, drawing breath noisily: the remainder of the blur lay still.

Moti All now advanced from behind Simonds and Erskine, who stood undecided outside the gate: "Yusuf Khan, is that you? Did I not tell you to come silently—to make no noise; why do you embroil yourself in a turmoil at the gate of my house?"

The swaying figure steadied, gasped what was intended to be a chuckle and then broke into a short, harsh laugh: "Embroil myself in a turmoil, Moti All! Why do you permit three badmash (rascals) to lie in wait for and assault a poor stranger at your gate? Thank you, sahib," he turned to Terrant, "those two were throttling me; that other one will greet shaitan with his tongue sticking out. Hey, Moti All, shall I put them all over the wall of the house opposite? Two of them will awaken later and they can decide what to do with the third!" And without further to-do he picked up the three motionless bodies in turn and pushed them over the wall as he had suggested.

Terrant started laughing, almost uncontrollably, accompanied by a snigger from Erskine who obviously had something to say which he considered to be important; at last he managed to make himself heard, "I believe that is the wall surrounding Nao Roz's garden;—what will her 'wealthy supporter' say when he finds that complication in the morning?"

"Nao Roz's garden! Don't talk nonsense! What do you know about it, Jerks?" Terrant demanded impatiently.

"Oh—Moti All told me," was the reply; which was followed by the retort, "Sahib, I never—ouch—Yes, I told the sahib—I thought it might interest him!" in a squeak from the flustered merchant.

Terrant and Simonds turned towards Erskine but could see nothing of him more than a darker shape in the surrounding darkness, and next to him a shorter shape that seemed to be clasping its middle—in pain perhaps—and rocking back and forth unsteadily on its feet. The silence was cut short, however, by Yusuf Khan's calm voice saying, "Sahibs, sahibs; would it not be wise if we were to enter the house at once?" Advice so good that almost as quickly as they had appeared upon the scene the alley regained its usual desertedness and secrecy.

Followed by Yusuf Khan they crowded into the reception room and back to the seats they had been occupying when the disturbance occurred: Terrant eyed Erskine reflectively and rather grimly until the latter began to wriggle and finally, under the continued stare, to go red under his tan: really embarrassed, he at last exclaimed, "For God's sake, Terrant old egg, why fix me with the eagle-eye? I didn't start the blinking riot!"

"No," was the reply, "but I wonder—"

Here, however, Simonds intervened, "Don't worry about that now, we must get on with the business": and turning to Yusuf Khan he continued, "What happened outside, Yusuf Khan?"

"Well, sahib; just as I was approaching the door those three leaped upon me; by great good fortune I had my wits about me and I hit and kicked two of them; the third I finished before the other two recovered sufficiently to attack me again, and then I caught their hands in which they had knives: they had me by the throat, but I was twisting their arms when the Captain sahib arrived"; and then to Terrant he beamed approval, saying, "Sahib; that was very quickly and well done; those two will have sore heads for many days, and I think that some hours will pass before they know anything!"

Terrant smiled while he and Yusuf Khan looked each other in the eye and came to an instinctive and appreciative mutual understanding: and now, while he calmly bound up with a strip of linen a rather ugly looking knife-gash in his forearm, they could all take stock of this Pathan who was to be their guide to whatever adventures were to befall them. He was a splendid fellow,—tall, lithe and muscular; fair-skinned and hawk-like, with his hooked nose and steady blue eyes set off by the black, carefully tended curl that hung below his turban just in front of each ear. Simonds breathed a slight sigh of satisfaction and asked, "But who were they, Yusuf Khan;—ordinary dacoits who had been following you to rob you, or is there a feud on your hands at present?"

"No, sahib; I don't know who they were; I have no feud just now, and who would be fool enough to think it worth while to rob me? And I am sure that I was not followed—they must have been lying in wait in the alley!"

"Hmm—Perhaps it is something to do with the owner of that house opposite; perhaps it would be better for the amorous young officer if he discontinues his visits there," Simonds suggested. "What do you think, Jerks?"

"Can't make it out, major; it's strange, very strange. Who did you say lived there, Moti All?"

Simonds grunted, but now changed the subject, and they all settled down to discuss the business in hand. First and foremost Yusuf Khan was perfectly willing to act as their guide, and he was fully qualified to do so, having returned only about a month previously from that neighbourhood: at this moment he had come, at Moti Lal's command, from his home in the mountains beyond the Khyber Pass.

With deep interest they listened to all the information he had collected on his lately completed trip; he first described how the journey had to be made through the desolate, mountainous country beyond Kashmir; how it was then necessary to cross some high and terribly arduous passes in the Karakoram mountains: and how eventually they would arrive in a valley terminated by mountains of sheer rock that formed a bare and apparently unscalable wall; yet across these they must somehow pass in order to penetrate into the country of Saria, their destination.

He had heard that through this wall there was a secret passage and that it would be necessary for them to procure another guide over this last part of their journey; the headman in the village situated in this valley could provide a guide for them—if he would.

Yusuf Khan himself had not penetrated further than the village; he was alone, and had found out enough to justify his return. It was said that pilgrims from all directions and in great numbers were flocking into Saria to worship and petition the Marble Goddess, for such was the name accorded to this powerful deity. Further, he had heard that in a chamber of a vast and magnificent temple rested a marble statue of a woman of exceeding beauty; and further, that this statue talked, asked questions, gave orders, and advised.

Rumour had it that in Saria there were about three hundred thousand able-bodied men, in the prime of life, all perfectly drilled and trained soldiers; and that they were of a strange race, being tall and fair.

Through the advice and commands of the Marble Goddess thousands of recruits from amongst the pilgrims were every year remaining in her country and joining her army: but he had heard no rumours as to the purpose for which the army was being formed.

As to the Marble Goddess itself,—all sorts of stories were to be heard; all agreed that it was very beautiful and that undoubtedly a voice came from the statue itself: some even said that at night it came to life, when it was accompanied and guarded by a white cat.

Here Terrant broke in with an exclamation but, after exchanging glances with Erskine, he turned to Simonds and apologized for the interruption, saying that there was merely an odd coincidence which he would explain later.

Yusuf Khan then pursued his recital:—he had tried to learn the history of this goddess or statue or woman, but only met with small success: she or it had been worshipped in Saria since the beginning of time,—certainly during many centuries,—but it was apparently only during the last few years that she had taken any very active control of affairs; a long time ago, however, the king had been dethroned and the monarchy abolished at her command: now her priests held all positions of state and, under her, controlled the country.

Finally—as he had already told them—the journey presented every kind of difficulty and obstacle;—mountains and desert and extremes of climate; throughout the latter part no food of any kind would be obtainable and, during the dry season, as long stretches of desert must be crossed, they would have to carry sufficient water for at least four days: during the rainy season the mountain passes would be impassable owing to snow, and other parts through mud.

At this time of year they should allow fully two months for the journey each way, and that was to say that if they started at once, had no serious delays on the way, and succeeded in entering Saria, they must start on the return journey in four months at the latest after their arrival there if they hoped to return to India before winter should again block the passes.

On Yusuf Khan expressing his willingness to start at once, Major Simonds requested Moti All to give orders for their tongas to be ready to set out the following morning on their drive to Srinagar: then he continued, "What do you make of those three men outside; it seems to me quite impossible that anyone should be trying to stop our expedition; were they just dacoits lying in wait for any lone man who might come along?"

Moti All shook his head in bewilderment, "Sahib, I do not understand this matter; it is a true word that I have never known such a thing to happen in this neighbourhood; and it is so seldom that anyone passes through this alley by day or night that no robber who knows the city would think of lying in wait there; and what should lead strangers to such a secluded and hidden way? If Yusuf Khan is certain that he was not followed, I do not understand the affair at all;—it is a pity we could not bring lights so that we might examine those men. But Erskine sahib is quite right,—that is Nao Roz's garden opposite; perhaps her supporter fears intruders and set a guard who mistook Yusuf Khan for a favoured lover!"

"I do not know this Nao Roz," said that stalwart individual, "but if I did and if she is as beautiful as you say—" and he drew himself up, smiling complacently.

"I suppose we must leave it at that!" said Simonds, and having bade Moti All and Yusuf Khan good-night the three of them returned to the club, now quite frankly burning with speculation as to the goddess.

Having settled down, Simonds asked Terrant for the promised explanation of his outburst: Terrant recounted his dream with an air of great bewilderment and ended by saying, "You see, old man, that dream sort of haunts me and I don't see why it should; you know I have never worried about women, but that woman,—well, I can see her still! And the cat! What on earth can have made me dream about a white cat? Hang it all, it's over the odds, I call it uncanny!"

Simonds smiled, "Yes, it certainly was an odd dream for you to have; now if it had been Jerks we should have had nothing to wonder about. Of course, you had probably been thinking a lot about our journey and its objective, which would account for the woman; but the cat part is odd, and the coincidence of it all is more than odd. I can't suggest anything other than that there are more things in heaven and earth, etcetera: and you never know,—perhaps you will agree with us on that score before we return to civilization."

Terrant made no reply; but he was more concerned than he cared to admit; very soon afterwards he pleaded weariness and made off to his room.

After a short silence Simonds asked Erskine what he thought of it.

"Well, major," he replied, "I don't know:—ever since his blessed dream Terrant has gone about with a face as long as a month of Sundays; I suspect he feels swindled because he didn't get a chance to kiss the girl—certainly I would: I expect he will buck up, though, as soon as we get on the move."

THE next morning everything moved smoothly, thanks to Terrant, who, after an early breakfast, superintended the loading of the tongas with the remaining pieces of baggage that had not gone forward with Hernam Singh. And Erskine had been correct in his forecast,—the former visibly brightened up; action was evidently the medicine that he required.

The start was made without any delay, and at last all three felt that their long-looked-forward-to journey had begun: the days of tonga driving would certainly be irksome, but there was movement in it, and that was the great point.

Nothing unusual or of particular interest occurred between Rawal Pindi and Srinagar. The first few miles, across the plains, were as dusty as the plains ordinarily are, and then came the abrupt wall of the "Hills", the road rising a sheer six thousand feet to Murree. This is one of the famous hill-stations from which, in one direction, are seen the massed snow mountains of the Himalayas, rising one range behind another and affording a scene of grandeur that cannot be described; in the other direction, far, far below, the eye takes in that everlasting flatness of the brown, dusty, sweltering plains and—thanks heaven for something else to look at.

After Murree there is plenty to occupy the eye and mind: the tonga swings round corner after corner, and after each one a fresh view is opened up that is certainly the most beautiful in the world. And so the hours pass until the eye is wearied and satiated: then the body realizes how uncomfortable a conveyance is a tonga, and the halts where ponies are changed are eagerly looked forward to; what a relief it is to get out and stretch the cramped limbs, if only for two or three minutes! The longer rests where meals are served are watched for as are oases in a desert. But all things come to an end sometime, even the drive to Srinagar.

They found Hernam Singh watching the road for their arrival and, with his help, were soon installed in their rooms at the hotel. He reported that men and animals were in excellent condition and that a start could be made at any moment.

Major Simonds decided that the next morning they would engage in sorting the baggage and making the final division of it into loads; and on the following day they would break camp,—a plan that would give them a chance to obtain sufficient rest after their cramping three days' drive.

This programme was followed in its entirety: the arrangement of the baggage devolved on Terrant and Hernam Singh, whose experience in such matters enabled them to make a rapid change from chaos into order.

By the evening of the next day a goodly quota of miles were stretched between them and Srinagar: camp was pitched early so as to enable each man to become accustomed to his particular duties without hurry or confusion and, after a good bathe in a nearby stream and a hearty, well-earned supper, a peaceful first night was spent on the trail to Saria.

The days that followed were each a repetition of the previous ones; the weather was of course perfect, as two or three months were still to pass before the rains should break: the trail led onwards through beautifully wooded hills and snow-capped mountain ranges, and all the members of the party rapidly hardened into that perfect condition of health which is only attained through days and nights spent in the open air with a sufficiency of work and exercise.

Sundays were given over to rest, clothes washing and such repairs to the equipment as were necessary: and Simonds having obtained shooting licences for all of them, the larder was replenished with chikoor, or mountain partridge, and the skins of three bears were added to the baggage.

By the time they had crossed the Indus without mishap the journey had begun to lose its holiday aspect: their path led them along a range of bleak and barren hills, even the air seemed to have undergone a change and it was now a harsh and biting wind that had to be met: the water also was bad and all suffered from touches of fever.

For days they followed this range with increasing discomfort, so that it was with heartfelt thanks for even a small change that they saw the track at last leading down towards a river that had been running parallel to it and which it now crossed.

Yusuf Khan informed them that while the current was extremely swift, the ford was good; they accordingly decided to cross at once and pitch camp on the other bank, although the day was drawing to a close.

All went well until a mule stumbled, and in its fall knocked Simonds off his feet; he was immediately caught by the current and carried into deep water. Erskine was close at hand and, fearing that Simonds was hurt, plunged in after him: both were powerless against such a stream and could make no headway against it: slowly at first, and then more rapidly they were carried down while the icy water numbed their limbs.

Terrant, who was just entering the ford, heard the shouts of alarm and, recognizing the danger at a glance, called to Hernam Singh to follow him to a bend in the river about two hundred yards lower down.

Running at top speed he shouted to Simonds to swim as much as possible towards this bank and then, arriving at the bend, snatched Hernam Singh's turban from off his head, telling him to hold one end while he with the other prepared to dive into the river and, if possible, catch Simonds as he passed.

Fortunately the current bore Simonds and Erskine in towards him and just enabled Terrant to reach the former, who, in turn, caught Erskine: Hernam Singh, powerful as all Sikhs are, succeeded in pulling all three ashore.

The rescue was made just in time, for both of them were completely numbed and exhausted; a minute later they would have been quite unable to help themselves at all and, in all probability, could not have been saved. By this time Yusuf Khan and some porters had arrived on the scene, and with their help the two shivering men were supported across the ford to the spot where camp was being pitched.

A fire, blankets, hot soup and brandy soon restored their circulation, and they then sank into a deep sleep: Terrant, having got rid of his wet clothes and after a stiff tot of brandy, felt none the worse for his immersion; but, anticipating that the other two would probably be feverish, he gave orders that camp should not be struck at the usual early hour next morning.

Three days were passed at this spot, as both Simonds and Erskine woke up with fever; one day was sufficient for the former to throw off all ill effects, but Erskine could not move from his bed until the third day and was then very weak and out of condition. The journey was only resumed on the fourth day at his urgent request: he was still quite unfit to travel but, as he pointed out, their present camp was very unsuitable for a prolonged halt,—being situated on the bank of the river and with no shelter from the bitter wind that blew down from the snows every night.

Now they advanced slowly towards a massive range of mountains, looming up about forty miles distant, which they would have to cross by a sky-high pass: and before negotiating this natural barrier they considered it advisable to send back the runner with the letters to their respective relations which they had written during their enforced idleness while Erskine was sick: so, at a gaunt village, huddled under towering snow peaks, they cut their last link with home and civilization.

And here trouble, of which they had for some days sensed an undercurrent, came to its climax. Their porters had been very carefully picked over from a large number willing, nay eager, for a long engagement; and not one had been chosen who was lacking in experience and good chits (references). From the start they had proved to be willing, happy and sturdy; and in a remarkably short time they had settled down to clock-like regularity both in camp routine and on the march.

But a few days previously a marked change had imbued their demeanour; from happiness they changed to the morose; they appeared to have something on their minds and became sullen. Simonds had asked Yusuf Khan and Hernam Singh if they knew of any reason for this change, but only met with the reply that while they too had noticed it no complaint had been made to them: as their work had continued to be thoroughly efficient, it had been decided to take no notice of what was probably only a passing discontent or unhappiness at leaving the joys of civilization.

But now, on this morning, after sending back the runner, they were awakened by Yusuf Khan before light had made its first tentative appearance: he told them that the porters were hurriedly packing their own few effects and seemed to have every intention of bolting; Hernam Singh was at that moment trying to dissuade them and to find out the cause of their discontent, but with no success so far.

Having struggled into a few clothes, they joined the stir that could be dimly perceived in the faint light now dawning in the east. Simonds soon found the man whom lately he had appointed head porter and with whom he had struck up a friendship during long conversations on the march. The man evidently disliked this meeting intensely and at first met the questions put to him with a stony silence; but at last his own good feelings and his respect for Simonds broke down his reticence and he hurriedly muttered in little over a whisper, "Sahib; we must turn back; this journey is cursed, and we with it, if we continue."

"Don't talk nonsense," Simonds expostulated. "Who on earth put such foolish ideas into your head: certainly the journey will be hard—but what is that to such as you and us? And who should put a curse on us?"

By now a group of porters were surrounding them, murmuring among themselves, evidently undecided and perhaps wishful to be persuaded. Then, from the darkness outside the group, came a voice, saying, "Do not listen to the sahibs, they do not know of what they speak. I tell you that this journey is cursed and by one whose curses are not uttered in vain."

A shot rang out and Simonds ducked to the whistling hiss of a bullet as it passed his head:—then Yusuf Khan's voice, shouting, "I see who it is: Hernam Singh, catch him, he is running past you!"

Hernam Singh turned, but too late; he glimpsed a shadow disappearing amongst the rocks that encumbered the outskirts of their camp and, soon giving up the hopeless chase, joined the group that was now composed of the whole party.

That one shot angered the porters—it was one thing to bolt and leave them stranded in a desolate country, but quite another to deliberately attempt to hurt or kill sahibs whom they liked—and as a result, all the influence that the man had painstakingly achieved was shattered and annulled: they certainly seemed relieved at his escape and disappearance, but they all now freely admitted that he had caused their decision to turn back by his repeated statements that only ill would come of the journey, that none of them would return alive to their homes and that he knew this to be true;—for one who had great power in the country beyond the mountains had passed the word through to Srinagar that the expedition would be destroyed if it proceeded beyond this village. And now he had run away, and who was he? None of them knew him; he had joined the caravan at Srinagar, but none had known him previously or even from what village he came—doubtless he was the son of unmentionable parents and his future was unquestionable.

And so in a few minutes, with the disturbing influence removed, the porters were all as happy as they had been at the outset and, being somewhat ashamed of themselves, showed an increased willingness, combined with a disdain for hardship, that continued to the end of the journey.

Later in the day, during the midday halt, Simonds called over Yusuf Khan and Hernam Singh; having bade them sit down, he explained that while the trouble with the porters seemed to have been settled out of hand the whole business was so extraordinary and incomprehensible that it ought to be still further threshed out in order that they might be prepared to meet and parry any recurrence, if it took place; for, he pointed out, if similar discontent and alarm did occur again and if the porters deserted them, it would mean that they would be left in a situation that would probably be worse than if it had happened now.

Yusuf Khan nodded agreement and went on to voice his own thoughts. "Sahib," he said, "two things have happened;—when going to meet you in Rawal Pindi I was set upon, and I think those men intended to kill me; and now we find that a strange man succeeded in joining the expedition with the sole intention, apparently, of inducing the porters to desert at the first point in our journey where we could not possibly replace them. These things make me to wonder if news of our true destination has leaked out, and if someone does not wish us to reach that place, and so is doing all possible to prevent us!"

Simonds replied with decision: "That cannot be. Neither of these sahibs nor myself have mentioned to anyone anything other than that we were going shooting in Kashmir: I am sure that neither you nor Hernam Singh have so much as breathed a suggestion of anything more definite." The two natives, keenly listening to every word, nodded assent. "And in India," Simonds continued, "I know that not more than three men, high officials of the Raj, know anything whatsoever about our mission. No! No information, no suspicion can possibly have leaked out. As you say, Yusuf Khan, there have been two incidents, unusual happenings, and in this last one there is no reason that we know of. Perhaps now that that man has tried and failed and gone we shall have no further trouble; but we must all watch for the slightest sign. I suppose that fellow won't come after us and try again?"

Hernam Singh answered emphatically, "No, sahib; he could not follow us without food in this country. And I have been listening to the porters;—now that he is gone they wonder why they paid any attention to his words and think that he is a badmash who was planning to rob them during their return to Srinagar as an undisciplined party. And perhaps they are right!"

In three days they reached the point from which their path finally rose to the pass, and very soon the difficulties of the advance became extreme. The way was very narrow and covered with loose, rounded stones on which men and beasts forever stumbled and slipped,—often with great danger to themselves, for the track was continually twisting and turning along the face of a cliff, a fall from which would mean certain death.

Once the whole party narrowly escaped annihilation from a slide of stones which crashed down across their path with a thunderous roar: fortunately they heard the noise of the downfall far above them and succeeded in passing the danger zone in the nick of time; but even then they nearly suffered a catastrophe as their mules took fright at the din and almost cast themselves and their leaders into the abyss below.

The climb to the head of the pass occupied two and a half days of strenuous going: on the second night they camped at the snow line, and the following morning made a very early start so as to reach the summit, or as near as possible to it, before the snow should be softened and made heavy by the sun.

Erskine throughout the whole of the climb had only kept going by dogged determination; he suffered continuously from headaches and shivering fits, but succeeded in hiding these symptoms of fever from his companions: lack of sleep and the intense cold of this night completed the damage done by his exertions at a time when he should have been in bed, and now, notwithstanding the fact that the snow, hardened by frost, made the travelling easier than any they had met with for the last two or three weeks, he could scarcely force his limbs to do their work.

At their first halt Terrant, immediately noticing Erskine's condition, which was quite unmistakable, called Simonds and Hernam Singh aside to determine the best course to follow; Erskine was obviously on the point of collapse. They agreed that it was of course quite impossible to camp in such a cold and exposed position, and that therefore the only solution was to divide the burden of one of the mules between them and to make him ride.

Having partaken of a light and hurried meal, they arranged accordingly; Erskine was now nearly unconscious and had to be held on the mule, but the going was practically level and very easy, so that they succeeded in making rapid progress.

By ten o'clock they had crossed the summit and commenced the descent on the other side of the range; and soon, on rounding a spur, a view was opened up that was as balm to their hearts. Their eyes rested on a scene of great beauty;—spread out far beneath them lay a country the very antithesis to the one from which they had lately emerged: low lying hills, gently rising and falling, advanced to meet a second range of snow-capped mountains that shone and glittered in the far distance; innumerable little streams meandered on their way towards a river lazily flowing down the middle of this great valley that glowed a vivid green in the sunlight.

Such was the sight that met their eyes, aching from the glare of the snow, and inspired them to greater efforts.

With all the speed possible they pushed on down the slope and, after four hours, left the snow, halting on a little grassy plateau where they rested and ate a belated midday meal. But, while they were vastly thankful to once again bask in a warm sun untempered by a cutting wind, Erskine's condition gave rise to dire forebodings; every hour it was growing more serious and, though not violent, he was delirious—mumbling and sometimes shouting incoherences while staring about him with expressionless and glassy eyes.

Soon they resumed their march; the descent though steep was not difficult, and by six o'clock it was finished. They halted at a spot admirably suited for camping, a small open space surrounded and sheltered by trees and close to a stream of crystal-pure water. But anxiety for Erskine weighed heavily upon them.

CAMP having been pitched, Erskine was rushed into bed, while Yusuf Khan set out to procure eggs and milk from a hamlet which he remembered to be near by. Terrant constituted himself nurse-in-chief and settled down to watch his patient, only consenting to be relieved by Simonds for an occasional four or five hours at a time, to enable him to bathe and snatch some badly needed sleep.

During the two days that followed Erskine steadily grew worse, the fever ever mounting higher; periodically he passed through spells of exhausting delirium, apparently re-enacting his hopeless battle with the river, and on these occasions Simonds's and Terrant's full strength was needed to restrain him.

This night he reached the crisis, and it was with dread that they looked forward to the morrow; they both feared, though they did not say so, that his chances of recovery were practically non-existent.

For thirty hours, without a prolonged break, Terrant had watched and attended his friend, remaining quite oblivious to Simonds's offers of relief and urgings to take a few hours' rest; he now insisted on continuing his vigil until at any rate two in the morning, by which time they expected that either Erskine would have taken a turn for the better or that the end would come.

Simonds, knowing full well how useless would be any attempt to influence Terrant, had retired for a few hours' sleep; Erskine lay in a state of coma, his body exhausted by high fever and delirious struggles.

Towards midnight Terrant could no longer see any signs of life, but on bending over him found that faint breathing was still perceptible: reseating himself he considered the advisability of calling Simonds, but was suddenly overcome by dizziness;—all objects in view seemed to recede until they were infinitely distant; all power to move left him; he endeavoured to shout but was unable to do so:—then came blackness.

* * * * *

"Where is she? Where did she go?"

As Simonds approached the tent these words greeted him—in Erskine's voice, a trifle weak, perhaps, but perfectly clear and with no traces of delirium.

There was no light burning inside; hastily striking a match, his amazement was deepened into stupefaction by the sight that met his eyes. Erskine, half raised on his elbows, was peering into the darkness in front of him, while Terrant reclined limply in his chair, blinking and apparently but newly awakened.

Simonds lit the lamp; he expected to find that the candle had been burnt away, but there were several inches left and it immediately flared up brightly. Turning back to Erskine, he found that he was now lying back in bed, a smile on his lips; his eyes were clear and healthy-looking and every sign of fever had left him.

Pulling himself together and gazing in turn at Erskine and Simonds with a look of such complete bewilderment that the latter could not restrain his laughter, Terrant suddenly exclaimed: "Did I really hear Jerks speaking, or did I dream it?"

"Oh no, you didn't dream it! Just as I arrived at the tent I nearly collapsed to hear Jerks calling out something like 'Where is she, where did she go?'; he seems to have been dreaming, but the last thing I expected to find was to see him as fit as he seems to be now! But what is the matter with you?"

Simonds, however, was not yet to be enlightened, rather was he to be still further perplexed, for Terrant, after gazing at Erskine—a heavy frown, almost a scowl on his face—demanded: "Did you see—Dr—something, Jerks?"

"Well, old man, as a matter of fact I've just been through a most extraordinary experience: I suppose I dreamed it—but I saw it all as clearly as I do you now—I saw a girl! Ye gods, a peach of a girl, and she was deuced nice! And she was just like the one you described after that weird dream of yours!"

"Did she come to the side of your bed and rest her hand on your forehead and stroke your eyes; and was she wearing a curious old ring?"

"Good Lord, did you see all that! She did, and she was! And the old white cat stood on the edge and barked at you," said Erskine with a laugh, "but she made up for that, didn't she?"

"If you will excuse me," broke in Simonds, whose impatience during this conversation had been visibly increasing, "are you both mad, or am I? What the devil are you talking about?"

"Tell him, Terrant," said Erskine. "We both seem to have seen much the same thing, only perhaps your story starts earlier; I didn't see the lady coming in, did you?"

"Yes, I saw her coming; at least—well, this is what happened to me:—I suddenly felt most awfully rotten; I tried to shout to you, Simonds, but couldn't; and then everything went black: I think I must have been unconscious for a bit, but don't know for certain. Then I saw a glow of light in that corner over there; it grew stronger and brighter and, suddenly, there stood the same girl I had seen in that dream—exactly as I had seen her before: she walked across to the bed and stood looking at Jerks for a minute or two and then put her hand on his forehead. The white cat had come in with her, and when I tried to get up the brute jumped on to the bed and swore at me: then she looked across at me and somehow I absolutely knew I mustn't move!

"Almost as soon as she touched Jerks I saw him open his eyes: then, after a little while, she stroked him. She looked at him again for a bit and, after making a few passes over him, smiled at me and disappeared—sort of faded away!"

Erskine took up the tale—"I didn't see anything until I suddenly seemed to wake up and found her standing beside me with her hand on my forehead,—and such a cool, smooth hand. Yes, I noticed that ring of her's, a great red stone in a curious old gold setting: I felt as weak as a kitten and devilish seedy, but as she stood there I tingled all over with pins and needles,—just like one of those electric shock things; then, when she touched my eyes, all the headache and wooziness left me and, as she made those passes over me, it felt like waves of warmth passing through my veins and I could feel myself growing stronger. Then she glided away and disappeared!"

"A crazy enough yarn," exclaimed Simonds, "but that you should both see the same thing is more crazy still. How do you account for it, Terrant? Upon my word, I don't know what has come over you!"

"Oh, don't rub it in, major; I take back all I said in Fateybad: blessed if I can make head or tail of any of it and, coming down to bedrock, I'll be damned if this was a dream. The great thing is that Jerks seems to be pretty well as fit as a fiddle;—there isn't a scrap of fever left in him, so I suggest that we turn in and have a good sleep,—I feel as if I could do with one!"

This proposal met with all-round approval, and Simonds, muttering something about "These young fellows seeing things!" returned to his tent.

The following morning both Terrant and Erskine slept late: the latter, on awaking, immediately proceeded to get up, and found that he felt as well as he ever had except for a slight weakness in the knees,—and this he expected to overcome as soon as he had satisfied an appetite that occupied his every thought.

At about midday they sat down to lunch: Erskine's state of health dumbfounded them; Simonds and Terrant could scarcely believe their eyes, for the change from the previous day was too unnatural, too impossible, to admit of any explanation. He should now be as weak as a new-born puppy,—if not dead; instead, there he was sitting before them eating voraciously enough to put to shame the proverbial pig.

Very little was said concerning the incident of the preceding night: Terrant now fully believed that the "vision" they had seen would prove to be in the exact image of the so-called Marble Goddess: but no one could suggest how she happened to know of their particular existence and, as it would seem, the object of their journey; and if she were not aware of these two things how could she, or why should she, first show herself to one of them and later save the life of another—for nothing could persuade them but that Erskine owed his life to her.

Being quite unable to understand or explain the problem, they forthwith let the subject drop as a topic of conversation, but it remained in the thoughts of each of them and materially increased their desire to pursue their quest with as much speed as possible.

During the afternoon Hernam Singh and Yusuf Khan joined them in council to discuss their advance: the former was able to tell them that men and beasts were in good condition and thoroughly rested, and the latter that, by taking short marches, they would have very easy going for four or five days; then the range that they could see facing them at the far end of the valley must be crossed.

He went on to expound how this was perhaps the most dangerous part of the whole journey;—if luck were with them they should have no difficulty nor should they meet with any particular trouble or danger. But the pass had an evil reputation amongst travellers; out of a cloudless sky storms were likely to brew without any warning; at one moment the peaks on either side of the pass would be starkly etched against a blue sky, silent and peaceful giants, and then, within a few minutes, they might be completely blotted out in swirling masses of cloud accompanied by a bitter hurricane. Such storms brought heavy falls of snow, and then, from miles away, could be heard the deep rumbling of avalanches. Many a traveller had started under a clear and peaceful sky to accomplish the final march over the pass, and had been heard of no more.

The prospect was certainly rather alarming; pursed lips and raised eyebrows passed between Simonds, Terrant and Erskine as Yusuf Khan added story to story of disaster and death. At last he was evidently satisfied with the degree of respect for the mountains that he had instilled among his hearers, for he concluded with the encouraging words, "But, as I said first, sahib, if Allah looks on our journey with approval and if no evil influences are brought to bear, we shall doubtless cross to the other side with no more discomfort than that which must be met with at a great height: we have already passed through some dangers and our kismet seems to be favourable."

"A cheery bloke is our Yusuf Khan," said Erskine. "I was beginning to expect he was going to tell us of armies of demons that awaited the harmless traveller amongst the rocky crags: anyway, I've got the idea that, watching over our tottering footsteps, there's a friendly spirit which is a match for all the evil ones that usually function around and about these haunts; so I propose just hoping for the best!"

"I think that that is the way to look at things," Simonds approved. "The great thing is that by the time we get to the next bad going we should all be as fit as is humanly possible; easy stages for the next two or three days would seem to be indicated."

And so it was decided that on the next day they should start down the valley, advancing easily and unhurriedly to the point from which they must commence climbing.

The five days' march that followed proved to be of unqualified enjoyment; the climate was perfect, of comfortable warmth, and their way led them continually through shady woods and beside softly murmuring streams. On the third day they crossed the central river without mishap or trouble of any kind and when, finally, this stage of their journey was done the whole party felt refreshed from the trials that had culminated in Erskine's illness, and fully prepared to meet any ardours to come.

As they approached closer and closer to the range so were their eyes more frequently turned to the heights above them and to the narrow gap through which they must thread their way. But day after day the guardian peaks stood clear against the deep blue of the sky, and never once did they hear the menacing growl of an avalanche. Notwithstanding the towering height of the pass, the climb did not look at all serious—if only this fine weather would hold for two or three more days: a simple grass slope led up to the snow-line and thence onwards their route would take them between two glaciers and up an open snow-field to a defile that separated the two peaks.

They climbed easily but steadily and camped on a small island of rock that projected from the surrounding expanse of snow: but that night, being unaccustomed to such thin air, their sleep was restless and intermittent, so that it was with relief that they hailed the coming of dawn and prepared to set out with the first appearance of light.

From here their progress was slow; the slope was very steep and the snow on the surface frozen into a smooth sheet, so that men and beasts continually slipped.

Under the circumstances good headway was made, however, until Yusuf Khan approached Simonds with anxiety written all over his face; he pointed out some heavy clouds that were rapidly forming around the peaks and apprehensively searched the snow-field for some spot where they might take shelter during the fury of the storm that he insisted was gathering.

As it turned out Yusuf Khan's worst fears were well founded, for the clouds gathered and spread so rapidly that in a few minutes the party was enshrouded in the descending mist; whereupon a halt was immediately called and a plan of action framed to meet the case.

Yusuf Khan affirmed that their only safety lay in reaching shelter of some sort; and of this the nearest to be found was amongst the rocks at the base of the peak that towered far above them. It was clear that, climbing in a cloud as they would, and perhaps also in a dense snowstorm, individual members of the party and of the mules were likely to stray from the rest and be lost in crevasses. Hastily, therefore, they uncoiled light alpine ropes with which they had provided themselves against just such an emergency; then first joining the mules into two strings, they divided themselves into three groups; in the first were Yusuf Khan, Simonds and Erskine, who were to act as path-finders; then came Hernam Singh with one lot of porters and pack-animals, followed by Terrant with the other.

By the time these preparations were completed snow had begun to fall heavily, and in this the climb was resumed; Yusuf Khan acted as guide, with Simonds checking his direction by compass as far as was possible.

After struggling upwards for about an hour their danger was made terribly apparent, for suddenly a great streak of lightning momentarily blinded them, and was followed immediately by a clap of thunder that sounded as if the whole mountain was falling about their ears. Then the full horror of their situation made itself clear;—dislodged by the concussion of the thunder, an avalanche had started far above them and, while they could hear the swelling rumble of its descent they could see nothing through the snow-filled air.

Nearer and nearer sounded that ghastly roaring; would they be caught in its greedy onrush? Nearer and nearer; they could now feel its very breath—the icy wind pushed forward by its devastating advance: they were enveloped and blinded by a cloud of driven ice-sand before which they crouched; the noise became unbearable; the very spot on which they stood shuddered and swayed and, hell let loose, the uproarious mass passed them by. And they knew that they had felt the hand of death itself!

Gradually the following hurricane died down and they emerged from the cloud of stinging ice,—one terror passed: but still, far below, they could hear the hungry monster growling on its way. And this was but merely the overture to the devil's concert to follow; every moment the storm increased in violence, and they were now in the path of a screaming tornado that swept across the face of the mountains: lightning flash followed lightning flash so closely one after another that even through the driving snow they could see the peak above them, their objective, as it were spouting fire: the thunder was one continuous, ear-splitting chaos of sound, so that only by the frequent tremblings of the ground could they realize that avalanches were falling pell-mell and all around them.

The mules, first paralyzed with fear, were now blindly struggling forward with them,—slipping and stumbling, but ever creeping upwards.

They had almost reached safety amongst the rocks when suddenly Yusuf Khan disappeared; having borne too much to one side he had fallen into a crevasse that, crossing their path, barred their way: with little difficulty, however, they hauled him out by the rope that had held him dangling over a bottomless pit. Then, forced aside by the crevasse, they faced into the gale and groped their way along the face of the mountain, feeling every step, until at last once again they could turn and compel their wearied limbs upwards.

The storm was now dying down, the wind was less fierce, the lightning but seldom slashed the clouds and the thunder was grumbling away into the distance. At last, so dazed and wearied that they could scarcely think, they stumbled off the snow; somehow they had made in safety the refuge that none of them had really expected to see.

A few moments sufficed to find a spot sheltered from the wind by a massive, overhanging wall of rock, and here the porters soon had fires burning of fuel that they carried with them.

For two hours longer the snow continued to fall when, as suddenly as it had started, the storm ceased; the clouds melted away and the sun shone out; all was as peaceful and quiet as if such a thing as a storm were an impossibility.

Greatly rested and refreshed by the warmth of the fires and a meal they lost no time in setting forward again: it was now about three o'clock, and there only remained a short four hours of daylight during which they must cross the pass and find some spot on the other side where they could camp. Yusuf Khan said he was certain that there was another outcrop of rock, highly suitable for their purpose, to which he thought they could attain in time; and thus it proved.

A very little climbing sufficed to bring them to the summit and thence, making better going down hill than they expected, they reached the "island" in slightly over four hours. Evidently the storm had confined itself to the side of the range from which they had come as, shortly after emerging from between the two peaks, they left all the freshly fallen snow and marched forward easily over a slightly softened but sufficiently firm surface.

In darkness they pitched camp, and night found them completely worn out by a terrifying experience that had been added to a long day's march.

AS a bird flies they were now only about two hundred miles from their destination: unfortunately, however, the configuration and general character of the intervening country necessitated their taking a circuitous and winding route of fully double that amount. Yusuf Khan reported that impassable marshes occupied the plains lying directly between them and the mountains among which Saria lay hidden, and that these marshes were infested by snakes and evil spirits; that no man had ever been known to succeed in making his way through and that no one would consent even to try to do so now.

What could be seen of this country from their present position was so far from pleasing that no argument ensued as to the advisability of attempting to take the direct course: a start was accordingly made in a direction leading very nearly directly away from their true goal.

At first they marched along the face of the range, negotiating a gradual descent that offered no difficulties, and made excellent progress; but then they entered a tract cut up by innumerable streams and gullies, travelling in every direction, which had cut deep into the soft soil. The sides of these streams were usually from fifty to a hundred feet deep and nearly perpendicular, so that their way continually doubled and redoubled on itself.

And so ensued five days of heart-breaking work, and though marching hard for hours the last halting place could still be seen apparently only two or three miles behind them. However, this stage at last came to an end and they were rewarded by an easy and straight, but ever rising, path.

They passed between two mountains, like sentinels, that rose sheer from the plain in grim isolation, and then for six days advanced, always up-hill, over a bare and desolate expanse of hard, packed sand, scantily covered with coarse grass.

At the height of this plateau they were faced, in the far distance, by the mountains containing Saria—a single range of black, jagged rock that was here and there adorned by a snowy pinnacle—while a great, bitter lake lay at their feet. For two days, amongst ever shifting sand dunes, they passed along its shore,—scorched by the sun, bitten to the marrow by the wind and half blinded by driven sand.

These evil conditions prevailed until, after three days further marching, they camped at the foot of the mountains that towered, dark and forbidding, above them. Yusuf Khan declared that it would be impossible for mules or heavily burdened men to climb them and that, in any case, they were but the outer bulwarks of Saria. Nature, however, had at some period cleft a path through the solid rock; but so narrow was it and so well hidden that to find it without previously knowing its position would prove a task that might occupy an army for months.

Yusuf Khan led them directly to the entrance of this passage: they advanced towards a face of rock rising sheer and without a break for several hundred feet and, in amazement, those in the rear saw the leaders apparently disappearing into the rock itself.

A gully, about ten feet wide, here running nearly parallel to the face, had its mouth covered by a projecting lip: after a few yards it turned sharply and led directly into the heart of the mountain; its sides, cut clean as if by some gigantic knife, towered thousands of feet into the sky. And, although the gully was open and roofless, so great was its depth that the sky was only seen as a thread of something not quite so dark as the walls, and the gloom was so dense that it was necessary to light the torches which Yusuf Khan had previously made ready.

"What an extraordinary place and how very nicely nature has arranged it all!" said Erskine, who was walking with Simonds and Yusuf Khan at the head of the slender column; and turning his head over his shoulder he further soliloquized, "A weird show altogether!" Simonds turned too and agreed, thinking to himself that the sight reminded him of something, he could not quite make out what,—perhaps it was a picture he had seen, when a boy, in the great volume of Paradise Lost that they had at home; or perhaps it was Moses on the Mount;—for behind him, sinuously—like some slow moving snake—writhed the dark shadow, picked out here and there with splashes of light, that was the uneven column of men and beasts and the occasional, swaying, ruddy-hued torch flares leaving trails of murky, black smoke: on each side and closely encompassing them the stark and rugged, dark walls, overpowering in their enormous mass.

The floor was of smooth rock carpeted with sand, so that their advance was audible only as a dull murmur accentuated now and then when metal struck metal or rock, and all deadened and muffled under the blanket of the heights above them.

They turned a slight bend and halted abruptly—automatically; for facing them and faintly illumined by their own torches were men, armed men, rank upon rank of them, each more indistinct than the one in front and thus fading into the natural blackness so that it was impossible to estimate their numbers. Its rhythm broken, bumping into those in front of them, with muttered curses, their little column came to uneasy rest, while its leading members stared, silent with surprise, at the equally silent ranks that faced them.

"What's up; what's the trouble?" shouted Terrant from the rear.

"Blessed if I know!" muttered Simonds, and then continued loudly enough for Terrant to hear him, "Stand fast; somebody is here to meet us!"