RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

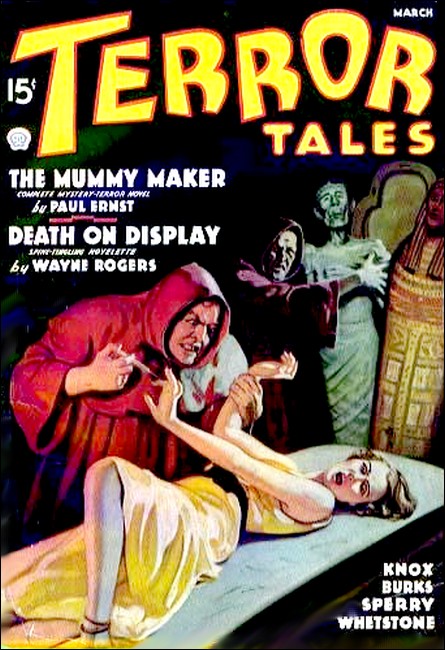

Terror Tales, March 1936, with "My Brothers From Hell"

The legend told of a compulsion that was upon the Barons of Hill House which drove them from their restless graves. Peggy Boynton beheld the consummation of a curse that had pursued her through centuries of terror...

PEGGY BOYNTON shivered and snuggled deeper under her coverlet. A chill drizzle was pattering at the windowpanes like the tapping of ghostly fingers, and the wind moaned around the turrets and towers of the old castle like a lost soul. She was sorry, now, that she had plagued Randolph, her husband, into making this visit to the home of his birth, the ancestral mansion that had housed his family since the thirteenth century. She was tempted to run into Ran's room and arouse him—get him to pack and take her away from this gloomy old castle right now—tonight. But she knew that was childish, and besides Ran was ill and needed his rest...

It wasn't only the storm and the gloominess of Hill House that had made her feel like this—there was something else: some indefinable, eerie quality of threat in the atmosphere of the place. It was as though all the bloody crimes of the Boynton clan in centuries past had left a poisonous, stifling miasma of doom clinging to its walls. As if...

Suddenly Peggy's slender body tensed and her eyes flew open to stare about her in the dank gloom of her great high-vaulted bedroom. She seemed walled in by the inky blackness which was relieved only by a faint greenish light that came from the south and east windows—and occasional blue-white flashes of lightning.

The girl had been almost on the point of dozing off when something had awakened her. What was it? Her ears strained to catch a repetition of the slight rustling sound that had seemed to come from some place near the right side of the bed. Was someone there in the room with her? She held her breath and fixed her eyes on the point in the darkness from which the sound had seemed to come. The next flash of lightning would reveal— With an almost audible hiss the lightning came in a blinding flash. For the space of two seconds it lit up the room with a brilliance stronger than daylight—and Peggy's staring eyes fixed on a ghastly figure standing there at the side of her bed!

The face of the thing was a nightmare mask. Its eyes were grotesquely huge in a head that was without a brow and was covered with a matted mass of long black hair. Its nose was a thick, upturned snout, and its mouth was a flabby gash from which protruded enormously long, discolored canine teeth. The lightning which revealed it seemed to light fires of bestial desire in the protruding eyes of the thing, and before the flash flickered out, Peggy saw huge, hairy hands darting toward her.

The girl's scream of abandoned terror was lost in the resounding crash of thunder following the flash, and as she felt the bed-clothes being jerked from her body, she leaped from the opposite side of the bed. The thing was between her and the door to Ran's room. Her only means of exit was the door on the opposite side of the room opening out onto the hallway. With heavy footfalls pursuing her flying feet at ghastly speed, she flung herself across the room and grasped the doorknob. Good God—she would never have time to escape before the thing was upon her! She wrenched at the door, yanked it open and darted through, slamming it behind her as something heavy thudded against it on the other side.

She whirled about, frantically clutching the knob, trying to hold it in a neutral position so that the latch would stay engaged. But her hands were covered with the icy perspiration of stark fear, and she knew that the slightest effort on the part of the thing in her bedroom would succeed in twisting the knob in her hands. She waited in paralyzed dread for the feel of its turning.

Another scream was rising in Peggy's throat, but the icy paralysis of suspense that gripped her as she stood there, waiting for the fateful turning of that doorknob, stifled the sound before it could be born. Then suddenly the sound of a soft footfall behind her swung her about, shocked free the rigid muscles of her throat so that a small, half-smothered cry escaped her. The thing in her bedroom had somehow circled around and was coming upon her from behind...

But no. Her terror-blinded eyes at last became focused on the figure approaching her from the south end of the hall, and in the dim glow of the single night-light she recognized the tall, dark figure of her brother-in-law and host, Sir George Boynton. The man approached and stopped within a few feet of her, taking in the rounded beauty of her slender form in its diaphanous night- dress with his burning, deep-set black eyes.

"What is the trouble, my dear?" he said at last as Peggy, her hysteria of fear overcome by sudden consciousness of her déshabillé drew up her hands to cover her breasts.

It was several seconds before the overwrought girl could gasp out a fragmentary recital of what had happened in her bedroom. At mention of the grisly figure she had seen bending above her as the lightning flashed a curious expression of rage crossed Sir George's face—and was immediately replaced by a look of amused deprecation.

"Surely, my dear girl," he said in his deep, sepulchral tones, "you have been dreaming. How could such a being gain entrance to Hill House? But, if it will make your rest easier, I shall explore your room for you."

He went past her, opened the door to her bedroom and disappeared inside, closing it after him and leaving Peggy standing in the hallway alone. The girl looked fearfully up and down the hall where Stygian shadows lurked in the corners, where the muted sound of wind and rain seemed to people it with flitting phantom shapes of terror.

She shivered, and hesitantly opened the door of her bedroom.

Sir George was standing in the middle of the now brilliantly lighted room, apparently looking about with great care. At her entrance he turned, looked up and smiled.

"You see—there is no one here," he said. He went to the bed, lifted up the hanging coverlets so that she could look underneath. He opened the clothes-press in the corner, showed it to be empty.

"But—but—it was over there," whispered Peggy, pointing to the far side of the room. "Maybe it went into the bath—or even Ran's room..."

"Very well—we shall see," said Sir George. He crossed to the bathroom, opened its door. He turned on the light, and even from where she was standing Peggy could see that it was empty. She followed him through to her husband's room, then, as Sir George turned on the light, looked about carefully in every place that the thing could possibly have hidden itself. But this room, too, was empty.

She glanced at the pale face of her husband who, disturbed by the light, turned restlessly and muttered something in his sleep. Cautioning Sir George to silence with a finger upon her lips, the girl turned out the light and tip-toed out of the room, followed by her brother-in-law.

She thanked Sir George, admitted that it must have been a dream, and bade him good-night as he bowed himself out of her room.

But Peggy had no intention of sleeping in that room any more this night. For all that she began, herself, to believe that she had merely experienced a nightmare, she could not bring herself to turn out the light.

She waited until the sound of Sir George's foot-steps died out, then she slipped on a lacy peignoir and satin mules, crept silently down to the library on the first floor. Turning on a reading light, the girl selected a book from the shelves and curled up with it on the divan.

BUT for some reason, Peggy seemed unable to get interested in

what she was reading. The atmosphere of the gloomy old castle was

like the incessant, monotonous dropping of water upon the girl's

spirit. She glanced up fearfully, from time to time, vaguely

aware that an indefinable something was menacing her... At last,

with a tremulous sigh she closed the book and returned it to the

shelf, but as she did so another title caught her eye: Evrard

Boyne and the First Barons of Malmsey.

She gave a delighted little cry, her fears for the moment forgotten. This, she knew, was a history of the beginnings of her husband's ancestral line. She eagerly took the book from the shelf and returned to curl up on the divan.

The history of the Boynton line, as Peggy Boynton knew, was a dark and tragic one. The book, written by a member of the family during the later years of the nineteenth century, recounted with amazing frankness how, apparently under the doom of the age-old curse of the Boynton clan, the origin of which was unknown, murder, treachery and disaster had been visited upon the family. "It is significant"—Peggy read—"that the victim of violent death in each generation has been the then Baron; and the person suspected of his murder in each instance has been the Boynton next in line for the title..."

Peggy had smiled when Randolph finally confessed to her that the reason he had never returned to Hill House, and never wanted to do so, was because of a family agreement that had been made after the publishing of the volume she was reading. That agreement stipulated that the Boynton in line for the title should, upon his fifteenth birthday, be removed from Hill House to some foreign country and there remain until the death of the Baron. After which event he was free to return and claim the title.

But Sir George's urgent invitations to Randolph and his new wife, and Peggy's own arguments had eventually won him to a violation of the agreement...

Peggy did not feel much like smiling, now. Her nightmare, if it was a nightmare, coupled with the growing feeling that the old castle hid some dark, grisly secret, lent the words she was reading a deep and sinister significance...

Somewhere in the house a board creaked. It was a small thing. Old houses are forever groaning and crackling as time dries the last of the moisture from its boards, but Peggy's nerves were taut and raw. She gasped and let the book fall from her hands. In that instant all the hidden, mysterious menace of the old house seemed to become concentrated about her, like the enfolding meshes of a black shroud. The girl knew suddenly, with utter, stark conviction, that someone was descending the great stairway in the hall. She rose to her feet on slow, quaking limbs, her hands pressed over her furiously pounding heart, and turned her widening, fear-stricken eyes toward the portières of the doorway...

Who was coming down those stairs? Was it the creature of her nightmare come to hideous, physical life?

She heard no more sounds, but the girl knew with a knowledge that did not depend upon her physical senses, that some presence, dire, threatening and unearthly, was approaching...

At last, after an infinity of waiting, the portières stirred, and a tall, somber figure stepped into view, paused at the entrance, one hand clutching the draperies, the other grasping the hilt of a poniard hanging at its waist.

Peggy gasped. It was Sir George—but a Sir George who was curiously and ominously changed. Replacing the long lounging robe she had last seen him in was a doublet of black velvet. His long, bony legs were clad in trunks and tights of black wool, and on his feet were the long-pointed shoes that had not been worn by Englishmen since the reign of the second Edward. But the change in Sir George extended beyond his costume, for his face seemed to have also undergone a sinister transformation. Darker, infinitely menacing, it was marked by a look of feral sensuality that deepened as the Baron came pacing slowly toward the quaking girl, his dark eyes lighting with ominous fires as his gaze devoured the lines of her lithe figure.

"GEORGE—" gasped the frightened girl as she backed

against the rows of books lining the wall—"what—what

do you—?" She choked off, a gust of terror seeming to drive

the last bit of breath from her body as the sable-clothed

apparition leaped at her like a springing cougar, its long, bony

hands outstretched avidly.

Then she was being clasped in a rigid, bony embrace, feral eyes blazing with black fires of cruelty and passion were devouring her, and a taloned hand was ripping the nightdress from her breasts.

Peggy screamed, and with a frantic strength born of hysteria, wrenched herself free from the Baron's grip. Sir George let her go for the moment, standing and watching her as she crouched in the corner against the mantel piece; then he was coming on, a leering smile contorting his thin-lipped mouth like a satyr's grin.

Peggy screamed again, called Ran's name frantically, and tried to dodge under the arms of the archaically-clothed figure, as Sir George sprang upon her the second time. But she was caught, trapped helplessly there in the corner by the fireplace, and the Baron caught her with a low chuckle, and, forcing her head back, planted his lips upon hers in a stifling and brutal kiss.

Peggy felt her senses leaving her, even as she shuddered at the cold clamminess of her attacker's hands as they pawed avidly at her body—and then her glazing eyes were caught by a movement of the portières at the doorway. Sudden joy and relief flooded over her, and before she thought she cried "Ran—Oh, thank God!" and Sir George released her and swung about with a snarl, his hand flying to the poniard at his hip.

Then it was that Peggy saw that her husband, like Sir George, was clad in the hose and doublet of a long-past period, excepting that in Randolph Boynton's case, the costume was of a shade of deep maroon, instead of black.

Wonderingly, stricken with a weird sense of fantastic doom, the girl's hand distractedly went to her forehead, pushed back her disheveled, raven hair as she moaned softly in fear and bewilderment. Meanwhile, her husband was pacing slowly forward, his blazing eyes fixed upon the snarling face of Sir George, and in his hand, its point raised and poised for a deadly thrust, was a long, gleaming rapier.

"Oh, God," moaned Peggy suddenly, as her husband's intent became all too obvious to her. "Oh, no—Ran—no, no... not that—!" But her husband came on, paying no heed to her frantic appeals. Sir George had drawn his long poniard, and, stood, now, with his legs spread, poised on the balls of his feet, the poniard held in his right hand, and thrust out before him.

Then, suddenly, Randolph Boynton lunged forward, the blade in his hand flashing like living fire and singing a shrill, frantic song as its steel clashed with the poniard in his brother's hand. Sir George had parried the thrust, and now forced Randolph to leap quickly backward with a savage riposte. But Randolph recovered quickly, leaped aside, thrust again, and with a powerful twist of his wrist, flicked the poniard from George's hand and sent it sailing across the room where its point sank into the wainscoting with a thud.

Randolph thrust a third time, and now Peggy's horrified eyes saw the gleaming blade of the rapier in her husband's hand disappear into the breast of the Baron's doublet for two-thirds of its length; and then its point emerge redly from between the Baron's shoulder-blades.

Sir George gasped hoarsely, and with a savage jerk Randolph freed the blade from his body. The Baron stared at his brother with eyes spread in a glare of stricken horror. He raised on his tiptoes and took several quick steps forward as his riven heart banked the blood in his arteries. Then he whirled, a ghastly, minuetting skeleton in raven black, and as a red stream came gushing from his mouth, crashed headlong to the floor, the bright arterial blood quickly puddling into a ghastly halo about his head.

Without a sound Peggy slipped senseless to the floor in front of the divan and lay still.

WHEN Peggy regained consciousness the silence of the great

house had resumed its sway. Staggering dazedly to her feet she

gazed distractedly about, her eyes instinctively seeking the spot

where she had seen the stricken form of Sir George topple to the

floor. The spot was vacant now. There was no sign of blood, no

indication that a fatal struggle had taken place in that

room—and, strangest of all, Randolph had disappeared.

What had become of the body of Sir George? Why was not the thick Axminster carpet stained indelibly with his life's blood—and why had Randolph left her thus, to recover as best she might from the shock and terror of what had happened?

Then Peggy, with a sense of weird wonder that quickly changed to overwhelming relief, looked down at her nightgown and peignoir. In her struggles with Sir George they had been all but torn from her body. By the time her husband had appeared she had been stripped half-naked—but now her gown showed not the slightest tear, it clung to her slender form, shadowily molding its rounded perfection, as whole and dainty as when she had put it on.

The girl sank with an incredulous sigh to the divan. It didn't seem possible that a dream could be so real—so horribly life-like in every particular. But there could be no questioning that it had been a dream—and the more the girl thought about it, the more its remembered air of actuality faded into the gossamer texture of a weird nightmare. After all, it had been too fantastic, too utterly impossible to have been anything else, despite its vividness. It was a companion to the dream about the monster...

Nevertheless, although the girl's mind was forced by the evidence of her eyes to accept this explanation, some half- smothered faculty of cognition repudiated it completely. A hidden sense was shrieking faintly in the back of her brain. There was a tension around her heart that took no account of the logical processes of her reasoning—and dread and terror of the evil that lived in this ancient house crouched in the corners of the great room like black panthers, poised to spring.

Suddenly Peggy jumped to her feet. She could stand it no longer. She dared sleep no more in this house where dreams came to tear her heart with terror and living dread. She would go to Ran and, ill as he was, insist that they leave immediately. There was something dreadful lurking in the dark halls of Hill House—some fearful menace that, so far, had expressed itself in incredibly vivid nightmares—but that might soon take another form. A form that might destroy them both...

The girl walked quickly from the room, almost ran up the broad stairs and came to a sudden halt at the stair head. The door to Sir George's room was open, and light was pouring out into the hall. Peggy went falteringly forward, something leading her on down the hall to that open, lighted doorway. She passed the closed doors of her bedroom and Ran's, went on as her heart struggled with inexplicable dread—went on as that faint voice in the back of her mind shrieked its warning. Then she was at the doorway, was fearfully peeping into the jamb at the scene inside the room—and horror swept over her brain in an icy flood...

"Ran!" moaned the girl. "Oh, Ran—" She took two faltering steps into the room and sank weakly into a chair on the verge of fainting. The room seemed to spin around her as though she were inside of a huge top, but her horror-widened eyes remained fixed on the tableau at the foot of the great bed.

It was her dream come to overwhelming, terrific reality. Her husband stood with wide-spread feet, a long, bloodstained rapier gripped in his right hand. His eyes were fixed on the prone body of Sir George Boynton who lay stretched at his feet in a pool of vivid blood which still trickled from gaping mouth and nose! In only one respect did the horrible picture differ from the one in her vision: both the living man and the corpse were clad in pajamas and lounging-robe—not the archaic trunks and doublets of her dream...

RANDOLPH BOYNTON, pale, shaking with horror and physical

sickness stood beside his wife's seated figure and stroked her

hair soothingly. "It all happened so quickly—so

inexplicably," he murmured. "I awakened with a sense that

something was wrong—went into your bedroom and found that

you were gone. I was not alarmed—thought, probably, you had

not been able to sleep and had gone down to the library to read.

But I felt a need of seeing you. I came out of the room, started

walking down the hall toward the stair head. Then I saw a light

under George's door, heard someone talking in a low tone. Knowing

that old Martha, the cook, was the only one in the castle besides

ourselves—since George sent the rest of the servants

away—I was curious to know whom George could be talking to.

I knocked on the door, and immediately the voice ceased. There

was a long silence, and then George's voice said to come in.

"George was standing there at the foot of his bed. He had on his lounging robe and as I came in he glared at me, seeming for some reason to be very angry. I told him that you had disappeared from your room, asked him if he knew where you were. He didn't answer for a long time, just kept staring at me with a sort of calculating, enraged glare, and when he did speak it wasn't to reply to my question. He just said, 'How long have you been out there in the hall?' I told him I had just gotten there. Then he wanted to know if I had heard anyone speaking in his room. He actually seemed to be out of his head with some mysterious, unreasoning rage, so I thought best to mislead him. I said that I had heard no voices. 'You're lying,' he shouted, 'but what you learned will do you no good!'

"Then he ran across the room, took that long poniard from the wall and rushed at me. I caught up a light chair and beat him off. I tried to reason with him, to find out what he suspected me of knowing; but he just kept boring steadily in, obviously intent in running me through with the poniard at the first opportunity. I was driven back against the wall, beating him off as well as I was able with the chair—but I was sick and weak, I knew I couldn't last long. Then I noticed two crossed rapiers on the wall near the spot George had gotten his weapon, and I worked my way down to them. I hurled the chair at George, and that gave me time to grab one of the swords from the wall.

"He hesitated when he saw that I was armed, but only for a moment. Then he threw himself upon me and we began fighting in earnest. I drove him backward clear across the room, begging him all the way to stop this nonsense and explain himself. But he kept grimly silent. Finally I got him over by the big 12th century tapestry in the corner. He was in a bad spot and he knew it. It was just a question of time before I could beat his guard down and get in a killing thrust—only I had no intention of doing any such thing. I merely meant to wear him down—if I didn't wear out first—or disarm him and truss him until we could get his head examined by a psychiatrist. But he was desperate as a cornered rat—and he lunged at me. I didn't thrust—I was just holding my blade out in front of me—but he literally impaled himself upon it... He staggered to the middle of the room and collapsed there at the foot of the bed... He muttered something about a curse as he fell—I couldn't make out what he was saying, but, of course..."

"Yes," murmured Peggy, "of course... the curse... Oh, darling, why did we ever come to this dreadful old house. Why was I such a fool—?"

"It's so strange," muttered her husband, "that George insisted so upon our coming. In spite of his scoffing about the curse of the Boyntons, he must have feared me... Why did he want me to—"

He cut off suddenly as a figure at the doorway caught his attention. It was old Martha Chilvers, the only servant that remained of the formerly large staff of Hill House. It was she who had ushered them into the house upon their arrival that afternoon; she who had cooked and served their dinner. Sir George had explained that his needs were few, that old Martha, alone, was able to care for him and the house adequately. But Randolph knew that the real reason was lack of money...

Martha Chilvers was fully dressed. She had on the same gown of rustling grey silk they had first seen her in. She was a curiously constructed woman, tall and heavily built with a heaviness that seemed composed not of fat but of bone and muscle. Her large, craggy face and skull betrayed the sufferer from hyperpituitarism, and her pale blue eyes gleamed out of their deep-sunk sockets with a strange and startling effect.

She stood there unmoving, weirdly impassive as her whitish, cold eyes took in the details of the tragedy. Not a flicker of emotion was visible upon her rugged, masculine face. Her coal- black hair was drawn straight back from her high broad forehead, her large bony hands were folded, held close in at her waist. Suddenly, having said not a word, nor betrayed by the slightest sign that the scene in her master's bedroom had affected her emotions in a way, she turned and walked down the hall.

Peggy glanced up as she felt her husband sway against her shoulder. His white, drawn face frightened her with the realization that he was very ill. She jumped to her feet, threw her arms about his shivering body. "Oh, darling," she murmured, "you weren't to blame. You had to defend yourself—even if he was your—"

"Yes—" muttered Randolph croakingly—"my brother... my own brother—and I killed him..."

"Hush, darling, don't—"

A sob choked her. "Come, you must go back to bed. I am going to call a doctor..."

Randolph's large frame leaned heavily on her slight one, as she guided his faltering footsteps down the hall and into his own bedroom. He sank in a state of collapse upon his bed. Peggy removed his slippers, drew the coverlet over his body and stood for a moment looking down at his pale, pain-lined face.

The girl felt her self-control breaking, shattering in her breast like a thing of brittle glass. What in God's name were they to do? Should she not force Randolph, ill as he was, to get dressed, and the two of them attempt to escape before he was apprehended for the killing of his brother? But she knew how futile any such attempt would be. They would never be able to get out of England. Already Martha was probably calling the police. They were doomed, the two of them. A broken sob escaped the girl as she felt the malevolent spirit of the old house closing in once more over her heart like a terrible, icy hand.

CONSTABLE RHODES arose from his inspection of the body of Sir

George Boynton and straightened his lanky frame to its full

height. His mild grey eyes fastened themselves on Martha

Chilvers' icy blue ones. "So his brother killed him, eh? Ran him

through with that sword."

"I can only repeat what I told you," said Martha stiffly. "I heard noises upstairs. I dressed myself and came up. I found Mr. Randolph standing there with a bloody sword in his hand and Sir George's body lying on the floor. Mrs. Boynton was seated there on that—"

"Yes, yes," interrupted the constable, "you told me all that before. But there was no eye-witness to the killing unless it was Mrs. Boynton—is that right?"

"The only persons left alive in this house," stated Martha precisely, "were myself and Mr. and Mrs. Boynton. I have told you that I didn't—"

"You're sure," interrupted Constable Rhodes, "that there is no one in this house but the people you have mentioned?"

The leathery skin on Martha Chilvers' face paled a shade or two, but after a moment she replied in a firm but somewhat lower voice, "No one!"

The constable's eyes lost some of their mildness as they bored into the woman's; but Martha's gaze never wavered under his. Finally the constable grunted and looked away. "There's some talk in the county," he muttered, "about—" Suddenly his eyes swept back again to Martha Chilvers.

The woman's solid frame seemed to stiffen slightly, her bony hands to grip each other tightly, but she gave no other outward manifestation of emotion.

"—about you and the Baron, Miss Chilvers," went on the constable. "They say that you are—"

"Stop!" The word came like a pistol-shot from the woman's tight-lipped mouth. "How dare you—how dare you repeat the idle, vicious gossip that—"

The constable drew closer to the woman, holding her with his eyes that now were without a trace of their customary mildness. "It's no use, Miss Chilvers," he said, and his voice was not unkind for all the steely sharpness of his gaze. "You might just as well make a clean breast of the matter here and now. This is murder, Miss Chilvers, and there is not a thing in any of your lives that will not be uncovered. You had no hand in this matter, you say—and therefore you have nothing to hide..."

"Why are you persecuting me like this?" broke in the woman. "I have told you how the crime was committed—and you haven't even made an attempt to arrest the guilty person. How do you know that he won't escape while you're here plaguing me?"

"All in good time," returned the officer. "You, yourself told me that Mrs. and Mr. Boynton are in the brown room, and that Mr. Boynton has been ill ever since dinner. It is not likely they will try to escape. I have two deputies outside, and have disconnected the magneto of Mr. Boynton's car. No—we will leave the questioning of Mr. Boynton until after the coroner arrives from Sheffield. In the meantime—"

"In the meantime," snapped Martha frigidly, "I shall tell you nothing more. I know nothing else that could have any possible bearing on this—this terrible tragedy!"

"Very well," said the officer after a moment, "then I shall tell you, Miss Chilvers: Twenty years ago, shortly after you entered the service of Sir George you conceived and bore a son. That son was an idiot. He has been kept in quarters in the basement of this house. He has never been seen by anyone but yourself and his father... Sir George—except—"

Like the cry of a soul being tormented by the fires of deepest hell a scream shattered the murky stillness of the night. It rose quavering and terrible—and choked suddenly off as though the throat that uttered it had collapsed through sheer horror. The man and the woman in the room with the body that had once been Sir George Boynton, eighth Baron of Malmsey, exchanged startled glances, and then the constable, with two springs of his long, powerful legs had dashed across the room and was at the door...

RANDOLPH'S eyes were closed, his breathing became deep and

regular. Peggy tip-toed to the wall and switched off the light.

Then she sank into a chair near the window where she could watch

the pale blur that her husband's face made in the dark. She felt

the poisonous blackness of the night closing in upon her with all

its malevolent promise of evil and menace, but she knew that Ran

would rest better with the lights out. The storm had blown over,

and the moon was breaking spasmodically through the scattering

clouds, and that gave her some small comfort.

Her mind had become dulled with suffering and terror, and she could bear to think no longer about what had happened this night in Hill House. What the morrow would bring she dared not guess... Perhaps the coroner's jury would accept Ran's explanation of self-defense... After all, there was no witness of the crime... Perhaps...

Physical and emotional weariness was overcoming the girl and her head nodded for a moment—then suddenly she was alertly awake, her eyes fastened on a place on the wall near the head of the bed upon which her husband lay. Was it a trick of the shifting shadows of the room, or had a portion of that wall become suddenly, inexplicably blacker?... As if a door had opened into darkness beyond— The shadow was rectangular, sharply defined even in the obscurity of the room—and now another shadow seemed to emerge from it—a shadow of irregular, grotesque outline. A leaden weight of terror was gathering in Peggy's stomach, an icy wind seemed to stir her hair, to play over her neck and wrists, but she could not move—could not utter a sound...

Now the shape had detached itself from the rectangular shadow, was creeping slowly toward the bed upon which Ran lay—and Peggy knew with horrible certainty that she had seen it before—that it was the shape of the inhuman monster that had leaned over her bed earlier tonight, inaugurating a train of horrors that had immersed her life and Ran's in blackest tragedy.

As she watched, paralyzed and helpless, the grotesque figure reached the bed, paused a moment as moonlight straggled through the windows at the south end of the room, dimly illuminating the macabre scene with a ghastly, greenish light. Now Peggy could see the bestial face with its horribly long canines, its snouted nose and flabby, grinning mouth. The nightmare figure was gazing down at the sleeping figure of her husband with an expression of malevolent glee. For a moment it seemed to gloat on the helplessness of its victim—then slowly one of its arms raised above its head. In its huge, extended fist was a long dagger that reflected the pale gleams of moonlight. Now it was poised, ready to flash down— Peggy screamed. With a supreme effort she shook off the paralysis of terror that gripped her. She sprang from her chair and darted toward the obscene figure standing at her husband's bedside. With a bestial snarl the thing swung to meet her, slashed at her viciously with the dagger in its hand as she closed with it.

But the thrust was illy aimed. The monster's wrist struck her shoulder and the knife was jarred clattering to the floor. Then its huge-boned arms were about her, its foul breath was invading her nostrils, suffocatingly, sickeningly...

Suddenly the thing gave an unearthly yell and released her. In the same instant the lights of the room flashed on, and Peggy sank half-fainting to the floor. Randolph dropped the dagger he had swept up from the floor and which was now dyed crimson, and caught her collapsing body. The bark of a gun roared out in the room and the monster shrieked again, crashed on the bed from which Peggy's scream had roused Randolph. Constable Rhodes stood in the doorway, a smoking revolver in his hand.

THEN there was another shriek, and Martha Chilvers swept by

the officer and ran to the writhing figure on the bed. "My

son—my son!" she moaned. "What have they done to

you...?"

"Not half what will be done to him if he lives long enough to be tried for the murder of his own father," growled Constable Rhodes as he picked up the dagger and inspected it carefully. "Too bad you had to use it on him, sir," he said, turning to where Randolph knelt beside his wife on the floor, "but I reckon the nature of the wound in Sir George's back, and the shape of this thing will be enough to prove what weapon killed the Baron—and whose hand it was in when the fatal thrust was given... Even though the fingerprints must be pretty-well messed- up by your own—"

"What do you mean?" interrupted Randolph Boynton. "Are you trying to tell me that that thing is George's son—and that it was he who killed the Baron?"

"Just so," replied the officer. "You see, sir, when I examined the body of Sir George, I found it in a curious condition. It had two wounds in it: one, a superficial wound in the left side that had been delivered from the front by the rapier that was lying there on the bedroom floor—and another, the fatal wound which had penetrated to the heart, and had been delivered from the back by a much shorter, thicker blade...

"The first marks of blood on the floor were near that big tapestry in the southeast corner of the room... Now I know this old house pretty well, Mr. Boynton, although I've never been in it before. But, you see, my father was constable in this county before me, and he was in office when Sir George's father met his death—through heart-failure, so they say—although there's others that claim Sir George helped his heart to finish off the old... But never mind—that's another story. As I was saying, my father told me all about the secret passages in this old house. It's a regular honeycomb of them. They run through the thick partitions of every room, and connect with each other and even have stairways going down to the basement, and connecting with all the upper floors. I knew that one entrance was behind that tapestry. I tore it down and found the panel that opened into it. Sure enough, there were new footprints in the dust—so it looked to me like somebody had taken, advantage of your fuss with the baronet to do away with him...

"We've long heard stories in the county, sir, about an illegitimate, idiot son that Martha Chilvers had borne the baronet—and I thought it might be advisable to track down that story before I went any further. So I was just questioning Miss Chilvers when—"

"You can't do anything!" shrieked Martha Chilvers, turning a dreadfully contorted face toward the group in the middle of the room as she bent the moaning body of her son. "He's not responsible, I tell you. That devil, George, put him up to knifing Mr. Randolph, so he would inherit his money. George was ruined financially, and he planned to get his brother here, force poor Carl to stab him in his sleep and then kill Mrs. Boynton—or throw her into that dreadful dungeon downstairs where he has kept poor Carl all these years. But you can't do anything to him, I tell you—my poor boy is not right in his head—he is not responsible..."

"He kicked me," came the childish wail of Carl from the bed. "I went through the wall in the pretty lady's room to see her—but she ran away—then papa came in and cursed at me and kicked me. Made me get back into the wall and wait until the man had gone to sleep. But instead I went to papa's room, and waited behind the big curtain. And I stuck him in the back for kicking me, I did—"

"Yes," interposed the constable. "Then you came back to stick the man, as your papa had told you to do—didn't you?"

"Yes," mumbled Carl. "Papa said he would give me some toffee—"

The constable went over to the bed and examined the idiot giant's wounds. He tore up one of the bed-sheets and bound the bullet wound in his arm and the slash on his shoulder-blade. "You'll be all right," he said. "Pretty soon you'll be going to a nice home, Carl. You won't have to live down in the cellar any more. Don't you think he'll be better off there, Miss Chilvers?" he added turning to the weeping woman.

"Oh, yes," sobbed Martha. "I would have put him away long ago—some place where I could have visited him often. But George feared the scandal that might come of it—and it seems that he had his own cruel uses for the poor thing. He has not let me see him for the past few weeks, or Carl would have told me about it, as he did just now... He isn't really a bad boy—"

Randolph had helped Peggy to a chair and was bending above her solicitously. She looked up at him, smiling a little wanly. "You see, dear," she murmured, "there was nothing to the curse of the Boynton's, after all. Sir George is dead by the hand of his own son—but a son who could never inherit the title—because he is illegitimate!"

Randolph Boynton nodded soberly. "Perhaps so, my dear," he murmured, "but I know a method of doing away with the whole matter for all time... I intend to renounce the title, sell the estate—for its mortgages, probably—and return to the United States. What do you think of that?"

Peggy grasped his hand, raised it to press it against her cheek. "I think that would be wonderful," she said.