RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1450-1516)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1450-1516)

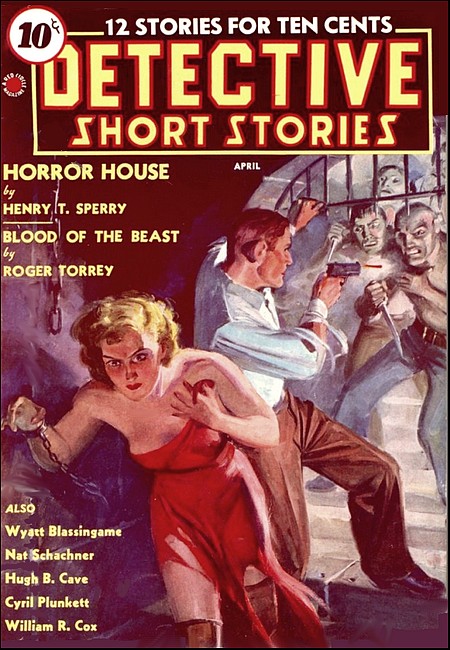

Detective Short Stories, April 1938, with "Horror House"

John Harbison could live on indefinitely—

if he obeyed every whim of a sex-mad doctor!

JOHN HARBISON was trying to understand. It was difficult, because his mind seemed unstable, his perceptions vague and dreamlike. He heard the words Dr. Faustus was saying and understood their general import; but he couldn't realize, quite, that they applied to him. Someone had died, and then, in some utterly incomprehensible manner, had been brought back to life again. Could it actually be he, John Harbison, whom the doctor was referring to?

The physician who had assumed this rather fanciful alias—perhaps, as some people thought, because he had sold his soul to the devil—talked on in a low-pitched, patient voice. He seemed kindly, affable, as he talked to John Harbison who lay there on the operating table in that room of cold glaring white and glittering steel. And John Harbison was listening carefully, trying to remember, trying to understand these things the kindly doctor was telling him, but which for a long time seemed beyond any human being's understanding. Too terrible, too painful for his groping strangely numbed brain to grasp all at once. And finally, when he did understand, it was too much for his overwrought nerves, and he lost consciousness again.

But this unconsciousness was not like the first. It was as if he had slipped off to sleep—a sleep troubled by nightmares, strange distorted visions of what had actually happened, colored and twisted by the fathomless horror of the situation he had awakened to there on Dr. Faustus's table.

Through it all Myrna's face swam like a pale, diaphanous moon. There were other faces, too. Shapes of furies and demons that seemed, somehow, vaguely recognizable. Their eyes glared at John Harbison from out of his dream, and their lips moved in an insane, squeaking gibberish.

The kindly Dr. Faustus leaned over and looked at his patient. And then, suddenly he wasn't kindly any more. A muttered imprecation bubbled from his thick lips as he pulled back the lid of his patient's right eye, and his face fell into lines of bestial rage.

"Karl!" he roared. "Karl, you fool, come here."

Almost instantly a wasted, tallow-faced youth appeared in the doorway of the operating room. The light of abandoned terror blazed in his phthisically-bright eyes as the flabby bulk of the doctor hurled itself at him.

Like an enormous, black tarantula, the doctor was then moving with surprising swiftness for one so ungainly-looking, so fat and flabby. One puffy, mottled hand reached out and grasped the boy called Karl by his skinny throat and shook him viciously back and forth, snapping his head forward and back on its frail stem of a neck, as though the boy were nodding a series of hysterical affirmatives to what the doctor roared at him.

"Dummkopf!" snarled Dr. Faustus. "Why did you not give him enough oxygen? Quick, get the tanks!"

With a final terrific shake he hurled the youth out into the corridor, so that he fell on the slippery tile floor, sliding almost as far as the opposite wall before he was able to scramble to his spindly legs and stagger off.

With another mumbled oath the doctor whirled about and strode on his fat legs to the side of his patient. He loaned over the body on the operating table, looking anxiously into the pale face, fumbling at the wrist for the pulse.

Soon Karl returned, trundling along two tanks on a rubber-tired hand-truck. Without direction from the doctor he adjusted the cone over the nose and mouth of the patient, and turned a small wheel controlling the valve of the tanks.

John Harbison's chest rose and fell with steadily increasing tempo until, at a signal from the doctor, Karl turned off the flow of oxygen and removed the cone.

Slowly the dream-wraiths faded out of John Harbison's mind, and a cool, white blankness took their place. His skin tingled with a cold, vibrant sensation. His tongue and soft palate felt stiff and numb as he opened his eyes again, and gazed upward at the quivering fleshy mass of the doctor's face.

DR. FAUSTUS had not been able to throw off the habits and

mannerisms acquired during the course of thirty years' practice

of legitimate medicine, even after he had left the paths of

ethical procedure far behind him. He still had the professional

bed-side manner. He was kindly, solicitous, as he practiced his

criminal, dark science upon the helpless bodies of his victims.

As his delicately-wielded scalpel carved living death into the

souls of his unfortunate prey, he clucked and murmured pitying

phrases. He was genuinely sorry for his "failures." He provided

them with comfortable rooms, fed them well, watched them and

guarded them with paternal solicitude until they died,

horribly.

For a long time John Harbison gazed up into the flabby, dewlapped mask that was the face of Dr. Faustus. And gradually, now, he began to realize what had happened to him. And with that realization came a false feeling of strength, generated by the white heat of the fury that surged suddenly in his brain.

John Harbison thought he was cursing: he thought that he was going to smash that soft balloon-face above him with his big, hard fist—but be was mistaken. He had become so weak that he could not even force his vocal chords into response to his desire to swear.

Later John Harbison lay with bandaged head upon his cot and watched a weird parade pass to and fro before the open door of his room. AH manner of men passed that door, bent on slow, mysterious errands. They were young men and old men; but they had several qualities in common: they walked with shuffling gait, their faces were uniformly drawn and pale, devoid of expression, and not one ever turned his bend to look into John Harbison's room.

He started calling out to them, but still they paid him not the slightest attention. Karl came, then, and warned him to keep silent.

"The doctor does not like it," said Karl.

"God damn the doctor," John Harbison said, glad that he could at least curse again, although be was still very weak.

DAYS passed, each day the counterpart of the one preceding.

Every morning Karl came and conducted him to the operating room.

Here Dr. Faustus injected a small amount of colorless fluid into

his arm hypodermically. Then he had to sit in a glittering cage

of glass, nickel, and brass for fifteen minutes, while he

experienced slight electrical shocks, and his nostrils were

assailed by a strange mephitic odor.

He was gaining strength rapidly, now: but the state of his mind and nerves did not improve. This seemed to cause the doctor to worry. He had trouble sleeping, and finally, apparently with great reluctance, the doctor began giving him hypodermic sleeping injections. The doe-tor also tried to reassure his patient, talking to him, during his frequent tirades of towering rage, with his uniform kindly patience. But he had little success, for this was one patient who could not forget and who would not surrender, even though he knew his case was as hopeless as though six feet of sod had been heaped above him.

For John Harbison was no longer a name that meant anything in the world of living men. He had died out of that-world as all men must eventually die out of it. A civil employee had examined him and made the pronouncement of death official. And the body of John Harbison had lain on the floor of the room in which he had found the dark girl, with a bloody path plowed across his head. But the girl had gone, by that time, along with the two thugs who had burst into the room, shortly after he had arrived. The Coroner said death had resulted from traumatic shock, and turned the body over to the two white-coated internes who appeared and carried the body out to an ambulance that had been parked by the curbing in front of the house, before John Harbison had even entered the room of the dark girl.

And John Harbison knew that although he lived again, he had left that other world as definitely and irrevocably behind him as though he had stayed dead. Dr. Faustus made that clear. He lived by virtue of the injections and the "treatments" in the glass cage. They must be administered every twenty-four hours or he would die, again. But if he stayed under the doctor's care, and endured the "treatments" and injections regularly, he might live on indefinitely. So Dr. Faustus said, and so John Harbison, perforce, believed.

THEN one day, after a particularly careful examination, the

doctor told John Harbison that he had completely recovered.

"Yes," said Dr. Faustus, "I think I may congratulate myself on your case. My technique is decidedly improving. Frankly, for a while, I feared that I had suffered just another... failure."

He wheezed suddenly, and his eyes rolled sideways in their fat-rimmed sockets, as though he feared the approach of something from the direction of the corridor. John Harbison thought of the ghastly, blank faces of the men who passed to and fro before the door of his room, day after day; and he wondered about the failures of Dr. Faustus.

Then the doctor licked his rubbery lips, and stretched them into that benevolent smile that John Harbison had come so to hate.

"I think you will be able to begin your duties, tomorrow," said Dr. Faustus.

"Duties? What duties?" asked John Harbison.

"The duties of an amanuensis," said the doctor with a fat smirk. "You were, in your former life, I understand, a rather well-known newspaper correspondent. The talent which brought you near the top of your profession will enable you to discharge the great obligation which you incurred when I restored your life to you. I am sure you will be glad to avail yourself of this privilege."

"Life!" snarled John Harbison. "Do you call this life? I can't leave this place; I can't even communicate with my friends. I am kept here like a prisoner, a slave to you and your Goddamned injections and your electric-olfactic treatments, as you call them. Why can't I go for a day at a time—returning for treatments every twenty-four hours?"

"I have already explained to you," said Dr. Faustus, "that I withhold all contact with the outside world from my patients for their own good. The hazards of normal life would inevitably result disastrously for them. And it is a bit unreasonable for you to insist that I give my secret to the world, merely so that you can resume what you are pleased to call your life. Kindly remember that you are, to all intents and purposes, dead to that life. It was I who rescued you from death, and restored you to another sort of life—not, perhaps, as pleasant as your former one—but better, surely, than death."

"I am not so sure," said John Harbison gloomily.

"Oh, come," laughed the doctor in his jolly bedside manner. "After all, you are rather well-treated here, it seems to me. And I ask very little in return. Perhaps you are not in a mood to appreciate it, at present, but I assure you that I am offering you a chance to share in my immortality. I say this without vanity. It is a simple fact that I, who have mastered the great enigma of death, will loom in future history as the greatest figure produced by the human race. How can it be otherwise? And the means I have been forced to employ, the fact that the members of my own profession would denounce me instantly, if they knew of the work T am engaged in—all this will be forgotten. Or, if remembered, it will redound to the discredit of my critics."

IN the end John Harbison agreed to undertake the work. Not

through gratitude or fear, but because he knew that he must find

some sort of activity for his harried brain, ne had begun to feel

that he was going mad. Horrible dreams tortured his nights.

Dreams in which he seemed to be eternally tossed about among the

storm-swept billows of a bloody sea.

That feeling of impotence, of terrifying weakness was utterly new to John Harbison. Big-framed, strongly-muscled, and possessed of a clear sharp brain, he was a man for whom life hitherto had held no terrors, no obstacles worthy of the name. And lately that fearful feeling of physical and mental incompetence had been assailing him during waking hours. It was as though his resistance to the attack of this inner foe had been formerly too strong for it while he was awake, but that he was losing ground to the extent that even with all his faculties on the alert he could no longer fight it off successfully.

He explained his symptoms to Dr. Faustus, at last, his mounting terror conquering his pride.

Dr. Faustus listened carefully, pulling out his lower lip with thumb and forefinger, and then letting it snap flabbily back in place, as though it were a thick rubber band. His face showed no surprise, only disappointment and depression.

"Yes, yes," sighed Dr. Faustus when John Harbison had finished. "I feared it was too good to last. I had hoped.... Well, never mind. You must get to work at once. You have a duty of inestimable value to the human race to perform. It will be your privilege to perpetuate for the benefit of posterity the record of my achievements—but you must hurry. I cannot tell definitely how much time you—we—will have..."

John Harbison glared at him for a long moment.

"That means I am going mad," he whispered huskily, and felt his knees give beneath him a little.

"Oh—no, no!" spluttered the doctor. "Not that at all—not at all. I—I merely meant that—well,—the sooner the better, you know. You're quite all right—quite all right."

He chuckled with a sound like buttermilk gurgling from a bottle.

But John TTnrhison knew that he lied, and in the end he began to work feverishly, hoping that thereby he might save himself—perhaps stave off indefinitely the ghastly thing that gnawed at the root of his reason.

The doctor arranged for him to work in the laboratory where there was a small table and a typewriter that had been set aside for him. Several days he spent in assembling the records of countless experiments, listening to the doctor's explanations, taking dictation from him, and outlining the book which he was to make out of all this.

But the doctor was impatient. He could not sec the need for all this preliminary work. "Why don't you just start in and write the thing?" he asked, childishly petulant.

So, really caring little how imperfect his book should be, John Harbison started to write. He found relief in the process, respite from the phantasms and strange fears that plagued his mind. But he was still in an over-wrought condition, irritable, on edge. He snarled at the doctor, to be met, always, with a kindly humoring attitude that merely heightened his irritation.

THEN came the day when the door of hell swung open upon the

house of Doctor Faustus.

A scream was the beginning of it. A piercing, long-drawn shriek that was like the cry of a soul experiencing its first stab of infernal fire. It was answered, immediately, by other shrieks, and the customary silence of the great house seemed blasted for all time.

Howls, wild shouts, eldritch wails echoed along the long corridors, rose faintly from deep in the bowels of the building, seemed to pour forth from every part of the house, as though every stone in it had suddenly become endowed with the voice of a maniac.

John Harbison leaped to his feet, hurling over the small table on which his typewriter rested. He stood trembling, fighting to keep from breaking, himself, into mad gibbering.

The doctor cursed and scrambled to a door at the far end of the room. He wrenched it open, disappeared for a moment into the small closet behind it, and came out with a long bull-whip in one hand and a pistol in the other. Still muttering curses he dashed out into the corridor.

John Harbison groaned and clutched the sides of his head with his hands. Those ghastly wails out there seemed to find a response within him that tore frantically at his brain for expression. An hysterical impulse goaded at him to raise his voice in a long shriek, to laugh wildly, to throw things about.

He shuddered and bit his lip until the blood came.

Then a different sort of sound arose above that mad bedlam in the corridor, and hearing it, he straightened suddenly and felt his brain instantly clear of the encroaching spasms of madness that had been beating in on it, as though borne on the waves of horrid sound.

For, while it was a scream of pure terror, that new shriek was unquestionably different in timbre from the other sounds raging in that house. There was, somehow, a note which carried conviction to John Harbison's mind that it emanated from a sane person. Without doubt, moreover, it had been voiced by a woman.

He sprang through the door into a human maelstrom.

It seemed to him that these maniacs had become obsessed with a senseless, raging fear of each other and of themselves. They tore and bit one another like rabid animals. They clawed their own cheeks with their fingers, shrieking. Some lay writhing upon the floor, foam flecking their lips, and their eyes seeming to start from their sockets.

He gasped and struck down two frantic creatures who flung themselves upon him, mewling and slobbering. Near the center of the corridor he made out the figure of the doctor, whose right arm rose and fell with a slow rhythm as though it were tired of its activity. The raving men were making no effort to avoid the lashing whip which was being wielded on their faces and bodies. They seemed not to know that they were being struck, until they fell, stunned or blinded. They clawed and struck at the doctor and at each other with complete impartiality.

John Harbison fought his way forward, striking out when he had to, but for the most part merely shoving a way through the tangle of legs, arms, and bodies that obstructed his path. He had covered half the distance to the doctor's side when something struck him from behind. He felt a pain as though red-hot pincers bad been sunk into the nape of his neck, and he knew that rabid teeth were tearing his flesh.

The force of the attack bore him to the floor. The man who had leaped upon his back was jarred off by the force of the fall, his teeth ripping loose from John Harbison's neck. Then evil-smelling, howling bodies were piling over him, tearing at his clothes and flesh, battering at his face with wild blows. Two claw-like hands were inching up his chest, under the pressure of another man's prone body, feeling for his throat. And John Harbison, whose arms were pinned to the floor, was helpless to fight them off, even after they fastened on his windpipe and began squeezing with terrible, merciless strength.

Time for one shout to the doctor, he had, before his breath was imprisoned in his chest and dancing lights began to flash before his eyes, to be followed by all-enveloping blackness.

THE blackness continued even after John Harbison opened his

eyes and knew he had regained consciousness. He lay for a few

moments staring upward into the dark, wondering confusedly if he

were blind. He was aware of intense cold, of a horrid odor. Then

there was a slight scraping off to his right, and the sound of a

low whimper.

John Harbison lay very still and closed his eyes again. Perhaps, if he were indeed blind, there was light for the thing that had whimpered to see that his eyes had been open—that he bad regained consciousness.

Then his outstretched fingers carried to his brain the impression of slimy stone surfaces. He was lying on floor of stone flagging, and the damp cold air suggested that he was in a cellar.

The whimper sounded again, followed by a long-drawn sigh. Then the scraping noise was repeated, and John Harbison was aware that something was stealthily approaching him. Something pawed at his leg, seemed to take direction from it and pattered up his body. Then he was grasped by his right hand, and he felt soft pudgy fingers pressing into his wrist.

John Harbison flung himself upward and struck out in the darkness. He felt his knuckles connect with flesh and bone, and the next moment his arms were encircling a large soft body.

"Don't—don't," gasped the doctor's voice. "It's I, John—Dr. Faustus. I was just taking your pulse again, my boy. You've been out for several minutes."

"Where the devil are we?" asked John Harbison, releasing his hold and standing up in the darkness. "And what, in God's name, is that awful smell?"

The doctor was silent for several moments. Then he whimpered again, like a wounded puppy.

"Ach, Gott, John," he said, "we're in a terrible predicament—terrible!"

He wheezed and gurgled in his throat, and John Harbison felt the pudgy moist fingers tighten on his wrist. Then a grisly memory came back to John Harbison and a ghostly wind seemed to fan the back of his neck. The morgue .... that was where he had smelted that horrible mephitic odor before. Only this was much worse.

"They've imprisoned us, John," husked the doctor fearfully. "Imprisoned in a horrible room in the cellar where— where...."

"Your private charnel house, I suppose," said John Harbison. "Where you throw the poor devils after they've died as a result of your tinkering with their bodies and brains."

"You put it very unkindly, John," whimpered the doctor. "You see, I couldn't very well dispose of them on the outside—"

"Shut up," snarled John Harbison. "There must be a way out of here. Think, man. Isn't there a partition we could break through? Another door—?"

Suddenly he broke off. There was a clanking sound, a rattle of a bolt and chain behind him. He whirled just in time to see a door open at his back. He threw himself bodily at the opening and found himself suddenly standing outside in the middle of a vaulted corridor, surrounded by the now quiet inmates of Dr. Faustus' house. The Doctor was but a step behind him and, having gained his side, turned and surveyed the humble blank faces before him with a swift questing glance.

What he saw in those faces apparently, reassured the physician, for he said "Hah!" in a triumphant tone, and brushed the surface of his palms together in o satisfied, complacent gesture.

"So you've decided that you'd rather go on living than be revenged for your fancied grievances, have you?" said the doctor in a cold, gloating voice.

"Randolph," he continued, turning to an extraordinarily tall, lean individual who, in spite of his extreme emaciation seemed to have a stronger light of intelligence in his eyes than the others, "I suspect you of being the instigator of this affair. I'll deal with you shortly. In the meantime, all of you go to your rooms—immediately!"

The men made uncertain shuffling movements, as though undecided whether or not to obey the doctor's command: then, with one accord, they turned their faces toward the man the doctor had called Randolph.

Randolph blanched, realizing, no doubt, that he was being tacitly condemned by his companions as their ringleader. But he recovered himself after a moment.

"We have had no treatments, doctor," he said, "some of us for longer than twenty-four hours."

He spoke softly, humbly, but there was a dangerous light far back in his deep-sunk eyes. The doctor saw it and went white in his turn. He knew, in that moment, that his dominance over these shattered men hung by a thread. He realized that this was the moment to put his power to the test; but he quailed before the prospect failing to bring them to heel and, perhaps, of instigating another riot.

BUT he was spared the necessity of making a decision for the

time, for at this moment a repetition of the shriek, that had

first brought John Harbison charging into the maniac-cluttered

corridor, came to their ears from the upper portion of the

house.

The patients of Dr. Faustus stiffened at the sound, and John Harbison noted how their eyes began to roll, as though they were being threatened by some dire influence. The doctor gasped, and tensed himself, stepping a little back, as though preparing for an attack.

John Harbison wheeled about and threw up his arms.

"Wait," he shouted in a great voice that thundered in the corridor. "Be quiet, and listen to me for a moment."

The madmen turned terror-filled eyes upon him.

"Wait," repeated John Harbison. "There is nothing to get excited about—nothing is going to hurt you. Go to your rooms as the doctor told you to do. He will begin giving you your treatments immediately!"

While he was speaking the doctor had been plucking fretfully at his arm. Now, as the men, with whining, animal-like murmurs begun to slink off, John Harbison turned irritably to the doctor.

"Well, what is it?" he demanded.

"That scream—" said the doctor. "I'm afraid something is happening to Gretel. She screamed like that a few minutes ago. I tried to get to her, but—"

"Who the devil is Gretel?" broke in John Harbison.

"She's my daughter," explained the doctor. "I'm very much afraid, John, that she's—"

AT this moment John Harbison discovered the doctor's pistol

lying near the opposite wall of the corridor where it had been

dropped and forgotten, apparently, during the doctor's struggle

with his patients. He scooped it up and dashed for the

stairs.

Shriek followed shriek, guiding him to the last room opening off the upper corridor. Reaching the open door of this room he paused in horrified amazement at the scene within.

A gigantic man, whose back was turned toward the doorway, was leaning over the body of a girl which lay on a divan. As John Harbison appeared at the door, this man was engaged in tearing the last of the girl's clothing from her shoulders.

John Harbison shouted and sprang forward as the man turned with a snarl, staring with blazing wolfish eyes over his tremendous shoulder at the intruder. Then he whirled about, his lips writhing back from broken black teeth, his arms dangling apishly. He seemed to grin ghoulishly as he roared like a lion at bay and sprang.

John Harbison shouted again and fired. There was time for one more shot, and the beast-like man was upon him. The momentum and weight of the great body bore him to the floor, the pistol jarring from his hand with the impact of his fall. But he rolled over immediately, and the heavy body, suddenly inert, sloughed down at his side, turning face upward and revealing two bubbling holes in its chest. The giant sighed hoarsely twice, little red bubbles rising and bursting from the two holes; then he coughed and was still.

John Harbison got to his feet and shook himself. Then he looked at the girl on the couch. She had raised herself on one arm and was looking at him. Suddenly, strangely, she smiled.

"Oh," she said. "It's you. You have rescued me again, haven't yon?"

John Harbison recognized her. It was the dark girl in whose room he had been killed.

There was the sound of hurried, heavy feet in the corridor and Dr. Faustus, wheezing mightily, was among them.

"Daughter!" he gasped. "What has happened?"

He stood in the doorway, puffing and gazing in blank amazement at the girl, the dead giant, and John Harbison in turn.

The girl smiled faintly. She seemed to have recovered her composure completely, and to be not in the least embarrassed by the fact that stockings and shoes constituted her sole apparel.

"One of your little pets decided to pay me a visit," she remarked casually. "I expected that it would happen some time. But it was my fault because I forgot to lock my door. Have you got a cigarette, John Harbison?"

Suddenly the doctor seemed to awake to the impropriety of the situation.

"Here, here," he wheezed, bustling forward. "Yon haven't any clothes on, my dear girl. That brute—My God! Here. Harbison, you had better go back to the office. Er—thank's awfully, old man—for—er—"

He divested himself of his coat and wrapped it about the girl's shoulders. Then he turned, waving his hand toward the door as he looked owlishly at John Harbison.

The girl gave her father a look of pitying contempt, and then smiled sweetly at John Harbison as he shot her an angry glance, turned about and strode from the room.

HE knew, now, that he had been the victim of a plot. That

girl—Gretel, the doctor had called her—it was she who

had called him that night, told him that she was a friend of

Myrna Travis's, that she must see him immediately concerning

something that affected Myrna's happiness. He had been a fool to

fall for that without calling Myrna first. But Gretel had warned

him against doing that. Oh, she had been clever, this Gretel had:

told him he mustn't let Myrna know; because Myrna would never

consent to the sacrifice John Harbison must make for her....

So he had come to the address the girl had given him, and he hadn't been in her room three minutes when two thugs had burst through the door and grabbed him. One had tried to jab him in the arm with a hypodermic, but John Harbison had put up too much of a fight for that. He had knocked the man sprawling and was choking the life out of the other one, when the man he had felled pulled a gun and fired. There was only blankness after that until he awakened in Dr. Faustus' operating room.

He went into his room, sat down on the side of his bed, cupping his chin in his hands. He stared at the floor in a mood of desperate melancholy.

Myrna—he must try to forget her. To think that he had ever wondered if he really loved her! They had known each other so long, come to take each other so much for granted. Sometimes he had felt that it would be a mistake for them to change their relationship to a more intimate one. But now she represented for him a veritable heaven of peace, sanity, and the joy of living.

Lost... lost

DURING the two days following things went on very much as

before the outbreak of the maniacs. The doctor had resumed giving

them their daily "treatments," and they seemed as quiet and

subdued as they ever had been. Nevertheless, John Harbison sensed

a tension in their attitude, a strange sort of brooding

watchfulness that he had not noticed before. Then, on the

afternoon of the third day John Harbison raised his eyes from his

typewriter to see Gretel standing in the doorway of the

laboratory, a pensive, quizzical smile lighting her really lovely

face.

John Harbison did not return her smile, but arose from his chair with grudging courtesy and said, "Come in," gruffly.

"Heavens!" exclaimed the girl, still smiling. "You're not very cordial, John Harbison."

But she came forward and seated herself gracefully in the chair John Harbison had just vacated.

John Harbison laughed shortly, staring down at her. "You 're either an idiot, like the rest of the inmates," he growled in a deliberately insulting tone, "or you're just plain dumb, to expect cordiality from me!"

The girl stared back at him for a moment, apparently surprised by this low-voiced outburst, then she threw back her head and laughed ringingly.

"You're quite charming, John Harbison," she gasped, when the paroxysm of merriment had passed, "even when you're rude. But really, you shouldn't hold it against me that I was instrumental in bringing you here. Father is a fearful tyrant, and I am deathly afraid of him sometimes. I am always very obedient to him and I never thought of disobeying him that day when he ordered me to telephone you and say the things I said. Of course, I didn't know what a nice person you are, then. I was only doing what I have done numberless times before, when father needed new patients to experiment upon...."

She paused as the frown on John Harbison's face deepened. She looked at him with an expression of wondering innocence, as though she could not account for his apparent non-acceptance of her explanation, and John Harbison, noting that expression felt something resembling awe at the realization that here was a woman as completely devoid of human feeling as the devil's mistress, herself.

"Do you mean to tell me," he husked, finally, "that you see nothing wrong in luring poor devils up here so that fiend of a father of yours can turn them into living dead men—into helpless brutes with minds of animals—"

"Oh heavens," interrupted the girl again, "I didn't lure them all up here. Only you and a few others. Most of them father gets from a morgue, and a certain prison where he has an arrangement with the Warden. But I help him in other ways. And, after all, if father is finally successful, won't he have accomplished something of—as he calls it—infinite benefit to the human race?"

"No!" shouted John Harbison. "Not even if he is successful. And any way, he can never be successful. Listen to this —here is something your illustrious father dictated himself."

He strode to the table and searched through the pile of papers upon it until he found the page he wanted. Straightening he read:

### QUOTE

"... and so it appears that the brain cells governing the higher functions of the body, being structurally more delicate, are the first to deteriorate. It is obvious, at any rate, that none of the cells can long stand up under a complete lack of oxygen, and it is of the utmost importance that the first steps in procedure A-2 be taken immediately following death. Even in such cases, when procedure A-2 was begun within two seconds after the diagnosis of death was made, profound changes had evidently occurred in the patient's cerebrum which, while not immediately apparent, began to manifest themselves in a complete syndrome of incipient schizophrenia within from a day to three days after the operation."

Suddenly he broke off.

"I don't know why I'm reading this to you," he said; but even as he spoke the words, the answer to his question came to him. The doubts he had been harboring concerning his own sanity had driven his nerves and self-control almost to the breaking point. He had reached the place where he must talk to someone —anyone, even this cold, self-centered woman—about the terror that had been threatening to engulf him for almost a week.

"Listen," he said, coming forward and gripping her tensely by the shoulders; "the doctor thinks that in spite of his other failures, in spite of the fact that some disintegration always takes place in the brain cells after death, in my case he has been completely successful. But he doesn't understand how he has succeeded. And I .... I sometimes think—sometimes I'm afraid I'm going mad—that the usual process of deterioration is merely slower, in my case—"

THE girl rose suddenly to her feet, and stood looking at John

Harbison with the light of fear in her eyes.

"But I thought—I thought—" she began.

"Yes?" he prompted with fierce eagerness. "You thought—what? What did your father tell you about me? Does he really believe that he has saved my sanity....?"

A calculating look came into the girl's eyes, and fear died out of them.

"I think you arc sane, John Harbison," she said; "but you are worrying, you are allowing the uncertainty to unbalance your nerves. Really, you are acting like an hysterical child. You should make more of an effort to get a grip on yourself." She slipped her hand into his and started leading him toward the door. "Come," she said, "I have some excellent brandy in my room. Perhaps a few drinks will—"

At this moment the door of the laboratory opened to reveal the rotund figure of Dr. Faustus. With a glance the doctor took in the details of the tableau of John Harbison and the girl standing hand-in-hand, and a look of petulant anger swept into his eyes.

"So," he said addressing his daughter. "Up to your usual monkey-shines, are you, Gretel? Mein Gott! What a hussy I have for a daughter .... Come, off to your room, with you."

He waddled over to his desk and sat down as Gretel, throwing a vicious look at him, and muttering something beneath her breath, tossed her head and walked out of the room.

THE next morning a shriek awakened John Harbison. At first he

did not identify the sound, but when it was repeated he realized

that it proceeded from some woman in mortal agony. Hurling on his

bathrobe he ran into the hallway just as another scream reached

his ears, apparently from the direction of the laboratory. He

dashed down the hall and threw open the door of the

laboratory.

The sheet-swathed figure of a girl rested on the operating table and over her body on either side leaned Karl and the doctor, the latter with a hypodermic needle poised in his hand. As John Harbison burst into the room the doctor looked up and scowled.

"Get out!" he shouted. "This doesn't concern you—get out, I say!"

From the table the fear-twisted features of the girl looked up at him imploringly.

"Oh, save me," she wailed. "He's mad. He's going to kill me and then bring me back to life again. Help me, help me!" she broke off, sobbing.

John Harbison sprang forward, but the doctor hastily jabbed the needle into the girl's arm, just as John Harbison caught him by the shoulder and spun him away with such force that the doctor lost his footing and fell to the floor. Karl was on John Harbison, then, lunging forward with a scalpel which he wielded like a dagger, trying to bury it in John Harbison's heart. But he missed his aim and the next moment went crashing into oblivion as John Harbison's fist cracked his jaw with a blow that hurled him half-way across the room.

The doctor had bounced to his feet like a huge rubber ball. His eyes almost disappeared into the puffy folds around their sockets, and his whole face swelled and grew blood-red with berserk rage. As John Harbison turned to meet Karl's attack he saw his chance, and catching up a light steel chair, crashed it down on John Harbison's head, just as the latter sent Karl sprawling on the floor.

John Harbison had a sensation as if someone had thrown a bowl of warm milk into his eyes, and then he sank into oblivion.

The doctor stood over his body for several seconds, breathing stertorously, the beet-like color gradually ebbing from his face. Then he turned his gaze on the girl, but she had fainted and lay there on the table, very white, and breathing almost imperceptibly.

"Verdammt!" exclaimed the doctor, as though in disgust.

And then a slight noise in the hall caused him to glance suddenly in that direction. He saw nothing, but went to the door of the laboratory and peered out cautiously. But not cautiously enough.

As he stuck his head out of the doorway he had a half-glimpse of a gaunt, flying figure bearing down on him from his left, but before he could move a muscle it was upon him, bearing him to the floor with the force of its charge. A wild eerie yell broke from its lips as the doctor went down, and it was answered, as though it were a pre-arranged signal, from every part of the house.

THEN Doctor Faustus was fighting for his life. Bone fingers

were searching for his throat. Wildly-aimed kicks glanced off his

round skull, crashed into his ribs, ground into his groin.

Frantic fists pummeled every portion of his body and long finger

nails ripped the flesh from his flabby cheeks.

Spurred by over-powering terror he gathered his strength, rolled suddenly over and over along the floor, momentarily escaping the clutches of his tormentors and even succeeded in scrambling to his feet.

But only for a moment.

In the next instant he was literally submerged in a struggling mass of howling, berserk mad-men. They clung to his arms, hands, and legs, and about his neck, like weird human festoons, and bore him shrieking to the floor. There he struggled and screamed until skeleton-like fingers suddenly shut off his windpipe. Then, for a while he merely struggled with increasing feebleness, until life slipped out of the quivering mass of flesh that was his body, and even the maniacs at last realized that they were mutilating a cadaver and not a man.

After that they quieted down, gradually, and stood grouped about the tall, spider-like man who seemed to be their leader, and who had been the first to attack the doctor. The eyes of this man glowed with a fierce light of insane satisfaction as he glared down at the prone figure of the doctor. Then he turned and looked in the direction of the laboratory. Speaking no word he started walking in that direction, the others following him with a blank trance-like look on their faces.

THE girl, Gretel, was perhaps the logical result of her

environment. Cold, cruel, and unscrupulous, she had never before

betrayed any of the usual feminine emotions. Her father had told

her she was an emotional moron, and she believed that this was

true. Still, she had fallen in love, after her own peculiar

manner, with John Harbison. But she had no wiles, knew not how to

go about attracting the man. She knew that she was beautiful, and

she thought that, perhaps, this would be enough. Her two

interviews with John Harbison had shown her that it wasn't. He

regarded her scowlingly, seemed to loathe the very sight of her.

He knew her for his betrayer. Obviously he hated her.

For the first time since childhood Gretel wept. She cried at night until her pillow was wet. For hours she wept after her encounter with John Harbison in the laboratory. She had suddenly become a woman. But she was still unscrupulous, still coldly calculating. She wanted John Harbison and she was determined to have him, cost what it might. His own happiness and peace of mind were secondary, even negligible, considerations. But in spite of all her planning, her carefully thought-out traps which she could, somehow, never succeed in springing, she finally admitted to herself that she was defeated. She was learning the bitter lesson that it is impossible to force a person to love one. And force, the sort of ruthless, lawless force she had learned the technique of from her father, was the only sort of tactics she understood.

And so Gretel wept the night through.

Toward dawn she had what, for her, amounted to an inspiration. She suddenly decided to tell John Harbison everything. She could not make matters worse, and there was a chance that he would forgive her, come to look upon her as a human, desirable woman—as, indeed, she was. And—she would tell him of her love for him. Perhaps—if only out of gratitude for what she could tell him—

And then Gretel heard the scream. The scream that awakened John Harbison, that aroused the inmates of the sinister house of Dr. Faustus to the murderous mania that such a sound always whipped into their twisted minds. But Gretel did nothing about it. She had heard such sounds before, had witnessed their effects on the poor lunatics in that house. She knew of the whip and the gun with which her father never failed to subdue them, and her orders, on such occasions, were always to stay within the confines of her locked room.

Later she heard the sounds of the rioting maniacs. She heard more screams but did not identify them as her father's. Indeed, they sounded like nothing human. But they were worse, more abandonedly horrific than any she had ever heard before. She shuddered and felt cold—a novel reaction, for her.

Then silence fell. She waited for several minutes before unlocking her door, opening it a crack, and peering into the hall. For the moment it was empty, but just as she was about to venture out, the door of the laboratory swung open and a group of men appeared hearing a limp body which she recognized with a gasp as being John Harbison. Behind this group came another, bearing the sheet-swathed form of a girl whom Gretel also recognized. It was Rosemary Travis, the daughter of Dr. Oliver Travis who, Gretel knew, was her father's greatest rival in medicine and his sworn enemy.

THE two groups of inmates disappeared into next room off the

corridor from the laboratory; and a few seconds later reappeared

and re-entered the laboratory, closing the door behind them.

A few minutes more the girl Gretel waited, and then she tip-toed softly up the corridor to the room into which she had seen the bodies of John Harbison and the girl disappear. Peering within she saw these two lying side-by-side on a cot; both very still and white of face.

Gretel gasped, and a curious mixture of emotions assailed her. She knew a terrible moment of dread as she noticed the pale face of John Harbison, and the look of death upon it. And then he stirred and moaned, but her gratitude at this reassurance that he still lived was tinctured by an unreasonable feeling of jealousy at seeing him lying thus, by the side of a beautiful young woman. Indeed, this sensation quickly dominated all the other emotions in Gretel's heart, and she advanced upon the figure of the unconscious girl with a fury blazing in her eyes that was not quite sane.

John Harbison stirred again and opened his eyes. The back of his head felt wet and horribly painful as it lay upon the pillow, and a blinding headache prevented him for a moment, from seeing that he lay beside the girl he had attempted to rescue from the table of Dr. Faustus; kept him from realizing that this girl's life was even now being more direly threatened than ever it bad been by the mad science of the evilly brilliant doctor.

But some instinct, powerful enough to bring the girl out of her fainting fit, warned her that death was close upon her, and she awoke in time to see the slim hands of Gretel advancing toward her throat.

Rosemary Travis screamed, and grasped the other girl's wrists, as Gretel's hands reached their goal.

That sound brought John Harbison back to full consciousness; but so stunned was he by the incongruity of the situation he had awakened to, that for a moment he was unable to move a muscle. Then, with a curse for the pain the sudden movement cost his battered head, he reached over and grasped Gretel by her forearms, wrenching her hands away from the soft throat they had been closing upon with lethal strength.

"In God's name what sort of a devil are you?" he groaned, his head spinning with a dizzy nausea, so that he had to fight with all his strength to prevent the girl's arms from slipping from his grasp.

And Gretel's eyes, tear-filled, and blazing with frustrated wrath, softened and became stricken with anxiety as she saw that he was badly hurt.

Jerking her arms loose from his weakening grasp she swept around to the other side of the bed, and knelt beside him, burying her face in his chest and breaking into wild despairing sobs.

IN the meantime Rosemary Travis had struggled to her feet, and

stood looking down at the strange tableau on the bed with wide,

uncomprehending eyes. Very beautiful, John Harbison thought her,

as he watched her while Gretel sobbed on his breast. Like a slim

Grecian goddess she stood, clutching the sheet which imperfectly

concealed the perfect curves of her glorious body. A strange,

unnameable emotion clutched at his throat as he noted the

frightened, wondering look in her wide blue eyes, saw the

terrified question in them as she gazed at him.

Sickness and giddiness swept over him and he closed his eyes with the grief and pain of a thought which came to him in that moment. For the sight of this girl brought home to him with devastating weight, the knowledge of all he had lost through the gift of spurious life from the hand of Dr. Faustus.

Gretel was sobbing, murmuring broken phrases, wetting the shirt over his chest with her tears. Suddenly she raised her head and gazed into his eyes for a long moment, looking at him with a strange expression as though weighing a question in her mind.

Then she began speaking, and John Harbison heard the story of how he had been tricked. Learned that the physician who had examined him and pronounced him dead had been too hasty; that Karl, discovering later that this was the case, as he prepared John Harbison's body for the experiment of Dr. Faustus, had been persuaded to keep the truth from the doctor by Gretel.

Between spells of uncontrollable sobbing this girl, who had once seemed so cold, so cynical and unemotional, poured forth her confession into the incredulous ears of John Harbison, while the other girl stood and gazed from one to the other in mute amazement.

"I knew that you would not stay here if you knew the truth," Gretel whispered, her lips close to his ear; "and so I let father convince you that your life depended on your staying near him. For ever since that day when I first called you to me, I have loved you, John Harbison—"

Then, as if it were a ribald commentary on the girl's confession of love, a wild cacophony of insane laughter suddenly broke on their hearing; and John Harbison tensed in anticipation of the breaking out of another horror in this house of multiple horrors.

BUT it was with a new feeling of joyous power to cope with the

worst that the house of Dr. Faustus might offer that John

Harbison rose to his feet, despite the still bleeding and painful

wound in his head.

"Stay here," he curtly ordered the two girls, and strode from the room, closing the door behind him.

The sounds of laughter, more subdued now, but containing a maniac, triumphant note that chilled his blood, came from the direction of the laboratory. But John Harbison hesitated not a moment. He walked down the length of the corridor and flung open the door of that chamber of horrors. And as his eyes took in the significance of the scene that now met his gaze, his brain comprehended what had happened even before the words of the tall, gaunt ring-leader of the madmen reached his ears.

This man stood at the side of the operating table, around which were ranged the other victims of Dr. Faustus's dreams of scientific glory. Upright on the table, itself, sat the quivering, white-faced bulk of the doctor, himself.

"And so, doctor," came the sepulchral tones of the cadaverous ring-leader, "you are now in a position of gain firsthand information as to the efficacy of your methods. You see, we feared that, perhaps, you were not as intensely interested in the problem of restoring us to a normal condition as you might be. Now, however, that you have been, yourself, brought back to life under the identical conditions imposed upon us, we are almost sure that you will be spurred on considerably toward the achievement of the goal that means so much to all of us."

A sudden plan formed in the brain of John Harbison, and he quietly closed the door and returned to his room. His intrusion upon the scene in the laboratory had not been noticed. He entered his room and closed the door behind him, standing there for a moment, looking at Gretel, who regarded him with an unspoken question in her eyes, trying to formulate in words the thing he had to tell her.

"Get one of your gowns for this girl, Gretel," he said at last, suddenly deciding to postpone telling her what had happened to her father. "We are all three going to get out of here as soon as it is humanly possible. I don't think we have anything to fear from your father's—patients—but it would be best to take no chances with them."

"I suppose father is dead?"

John Harbison paused.

"Not exactly," he said at last.

For a long moment Gretel looked at him, and again the man was struck by this woman's quality of cold detachment.

"I think I understand," she said finally and moved toward the door. John Harbison stepped aside and the two girls walked out into the corridor, toward Gretel's quarters. John Harbison followed them and stood guard outside the door while they went inside.

THE silence of tongueless dread brooded over the house of Dr.

Faustus, as John Harbison waited in that long dark hallway. No

further sounds came from the end in which the laboratory was

located, and John Harbison mused on the curious fate of this

doctor whose mad science had, at long last, overtaken him.

Then the door of Gretel's apartment opened and the two girls came out to him. But John Harbison had eyes for only one of them. Rosemary Travis was a vision of youthful loveliness in the dark cloak which Gretel had given her, her crown of golden hair in startling, brilliant contrast to the somberness of the wrap.

Then Gretel spoke, her eyes darkening with a hidden pain, as she watched the expression in his face.

"Good-bye, John." she said. "You can take Rosemary Travis back to her father, now. I will stay here with mine and try to help him and his poor slaves. He was evil and unscrupulous enough to try to sacrifice Rosemary merely because he hated Dr. Travis, her father; but he is all I have and I think he still cares for me in his strange manner. That, after all, is the only sort of emotion—if it is emotion—that I understand."

She extended her hand and John Harbison grasped it.

"Are you sure." he said, "that you want to stay here?"

"I am sure, John," she answered: "but I hope that, you do not feel it is necessary to inform the police about us. There is nothing left to be done for lather or his patients that anyone can do but father, himself. Perhaps he may yet discover the thing he has sought so long—the thing he was tricked into believing he had found when he thought he had brought you back to life, if he does, everything will be forgiven him, I suppose. And if not—no one can help him or his victims.... Good-bye."

She turned, then, and quickly re-entered her room, closing the door behind her; ami John Harbison looked deep into a pair of blue eyes that regarded him with an expression that sent a slab of joy that was almost physical pain into his heart.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.