RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

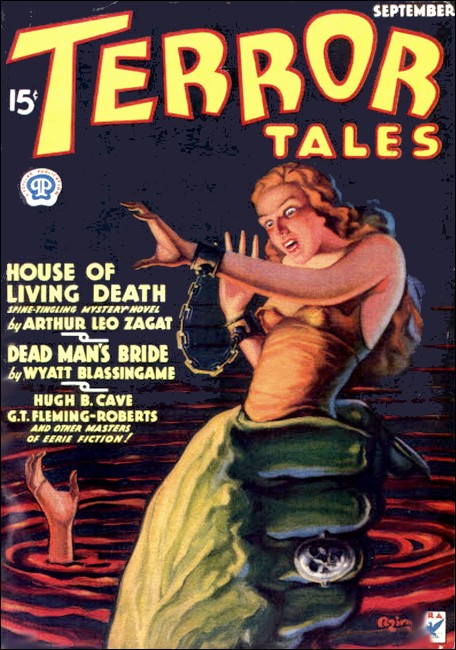

Terror Tales, September 1934, with "Hands Beyond The Grave"

A plain tale, simply told, by a man who lived two lives—and suffered much in both!

IT happened on the night of October twelfth, in my ancestral home near Huntleigh, Massachusetts. The events of that night mark the turning point in my life, and so far as this record is concerned, nothing that preceded it is pertinent. It is as if I, Robert Mercer, have lived two lives—the first, that of an ordinary, fairly fortunate young man, born into a conservative, well-to-do family—and a second, one which I sincerely hope is nearing its end, as different from the first as night and evil are different from day and virtue.

But before I begin my tale I must assure the reader that what follows is a simple, reportorial statement of fact. I must beg indulgence for those portions of it which seem completely incredible. I can only say that they happened to me.

The house had been home to my family for generations. I myself had returned from Paris to take up my residence there but a short time before. I had come back to marry my childhood sweetheart, Sylvia Blanding, and our wedding day was but a week distant. The Blanding and Mercer farms adjoined—the families had been neighbors since Revolutionary days—and now at last they were to be united.

That night I retired at ten o'clock. I was always alone in my house at night, for my cook and housekeeper slept at her own home, a mile or so down the state road, and my chauffeur had his quarters above the garage. On this occasion, after retiring I read for perhaps a half-hour; then, becoming drowsy, I put aside my book and switched off the bed lamp.

Then I slept. I slept soundly, untroubled by dreams or subconscious forebodings. Yet when I awakened, hours later, I was instantly aware, through some mental process too swift and mysterious to report, that a fundamental, all-embracing change had occurred in my life!

My eyes opened to behold a luminous gray shape, poised immovably above the footboard of my bed! No sound came from it, and at first I could discern no form to it. Yet as I looked I saw that it had a form. Dim though it was, there were limbs, a gray body—and a face without features. The thing had human shape!

How shall I express it? This ghostly form did not seem of itself to have caused that mysterious change which had occurred in my mind. It was as if I awoke with full knowledge of what had happened to me and that the luminous shape was but a symbol of it. And I was struck with a feeling of horror which I cannot hope to convey in words—a horror far out of proportion with the weirdness of the thing above the footboard of my bed.

Yet even in the extremity of my horror, I noted the cold October moonlight pouring in from the tall north windows of my bedroom, making silvery washes across the polished floor, and marked the oddity that the eerie shape seemed akin, in the nature of its luminosity, to that moonlight. Was the thing moving now? Or was it merely shimmering—vibrating within itself? I tried to thrust out of my mind the consciousness of the change which had come over my mind and personality like a thunder-clap, and decide on a course of action. I felt an impulse to address the ghostly shape and ask it what it desired of me; but I thrust this idea out of my mind as being starkly mad.

AT the same moment I remembered the presence, on the

south wall of my room, of a couple of crossed

javelins—heirlooms which had been handed down for no one

knows how many generations. And oddly enough I felt then that,

with one of these ancient weapons in my hand, I would be better

able to cope with the weird form. For I knew without thinking

that I must cope with it—to save myself!

However, it was a good five minutes before I finally mustered enough courage to slide slowly over to the right side of the bed and lower a foot tentatively to the floor. Here I paused; I was somewhat reassured to note that the shape had not changed its relative position. Cautiously I lowered the other foot to the floor and, trembling violently in every limb, slowly stood erect.

I felt my knees go suddenly weak as I saw now that the vibrating movement of the thing was increasing in rapidity. This seemed to my mind to presage a threatening advance; and somehow I felt completely incapable of escaping the onslaught of the thing, should it attack me.

There was only one mode of relief open to me—action—however ill-considered or ineffective. I could stand the strain on my nerves no longer and resolved to risk everything on a dash for the javelins. I sprang with all the agility I possessed for the south wall.

But quick as I was the gray thing was not less swift. Although it maintained the same relative distance from me that it had while I was in my bed, it arrived at the place where the javelins hung at the same moment I did! I wrenched one of them from the wall and turned to confront the eerie shape. It now hung comparatively motionless, pulsatingly poised a few feet above the floor—ready, it seemed, to leap upon me!

Complete panic claimed me. My breath came in a painful gasp that seemed to leave my throat raw. I jabbed madly at the wavering shape.

I had no real hope that my thrust would have any effect. I would not have been surprised if the weapon had passed through the thing with as little result as if it were composed of a glob of moonlight.

Yet the shape exploded with a deafening detonation! It was as though a piece of field artillery had been discharged in the room. For some moments I stood, stunned and deaf, unable to realize what had happened and somewhat of the impression that I had been blown to bits.

Eventually my mind functioned again; my ears regained their ability to hear. I was alone in the room, I am sure; even the shape was gone; yet the first sound to reach my ears, after they had recovered from their temporary deafness, was a human laugh—low but clear, coming I could not tell from what direction! Human—and yet surely it had been uttered by no living being. In it were contempt and derision diabolical in their intensity. It was the laugh of a fiend from hell!

I STOOD rooted to the spot, sick with terror, as the last

notes of the hideous sound died away. I waited, trembling. But

when it was not repeated, I did a strange thing. I lay back on

the bed, seemingly calm!

It occurred to me, merely as an idea, that I might call Mason, the chauffeur, or even go out and spend the rest of the night with him in his quarters; yet I made no move to do so. I seemed of a sudden to be lacking in all initiative, to have no real desire to leave the house. A harrowing thing had happened—a thing unearthly yet none the less real. And its final impact upon me had been so great that I no longer felt even terror!

Yet I did not sleep again. I lay on my bed, exhausted and mentally numb, until dawn. Such thoughts as I had during that time were vague and imponderable—I do not even remember them.

With the coming of dawn I seemed to think more clearly again. Whatever had caused my listless numbness, it was slowly leaving me. Now I remembered vividly the events of the night, and my reason told me to scoff at them as at the disordered imaginings of a nightmare.

Yet I could not scoff. I knew those things had happened. And oddly enough, now that the lethargy was leaving me, fear was coming back. I felt that I was in danger; I knew that I needed aid.

I tried to plan a course of action. By now it seemed the height of folly to call Mason. Somehow I knew he could be of no help to me...

More than anything else in the world, I wanted Sylvia. I wanted to talk to her, to look into the calm blueness of her eyes and find peace again. I wanted the soft coolness of her white hands on my brow, dispelling my troubles. Were I but to call Sylvia she would come to me and comfort me.

Would to God I had done so! Then, though it might not have changed what was to happen, at least she would have known—and understood—when the fatal hour came...

But masculine pride intervened. Here was I, I said, having allowed myself to be made into a terror-wracked weakling—and I wanted to call on the woman I loved for aid. She above all others must not see me as I was now. In the end, I forced all thought of Sylvia from my mind.

Naturally enough, the one I finally decided to seek out was my closest friend, the one who was to serve as best man at my wedding—Dr. Howard Crandall of Boston. I could ‘phone him and ask him for medical advice—ask him to drive out and examine me. And in the back of my mind was more than that. For Howard, besides being a physician of reputation, was Research Officer for the Massachusetts Psychical Research Society. He had talked to me often of the strange happenings he had, at the first through scientific curiosity, witnessed and investigated in this office—happenings and manifestations for which he could find no possible explanation by human means. In our talks, I had played the materialist and the scoffer, had chided him for what I called his belief in spirits. Now, I did not feel like scoffing—felt even that his knowledge might help me. At least it might prove to me that I still retained my sanity, a thing I had begun to doubt. I would call Howard as soon as I had breakfasted.

I arose to find myself still somewhat dull and groggy, dressed and made my way downstairs. To my surprise I found that Martha, my housekeeper, had not yet arrived, though it was now nine o'clock. All that day she did not appear; the reason I never learned...

THE day was dark, the sky heavily overcast with low-

hanging clouds which carried the assurance of rain before many

hours had passed. Abruptly, now I was assailed with a fear of the

coming storm and of being alone for another moment in this great

house the atmosphere of which, so calm and peaceful before, had

abruptly become surcharged with an inexplicable threat. Terror

was upon me. And if it sounds like the abandoned terror of a

coward, it must be remembered that I was struggling with an

assailant which seemed to attack my mind at the same time that it

manifested itself outwardly. Again I knew that a profound change

had occurred in my mental processes. My own mind was not master

of my body—yet it had a master!

I could stand this no longer, I would call Howard at once. I stumbled to the wall telephone and put in the call for Boston.

Once I had done so, relief flooded over me like a refreshing wave. I felt somehow strengthened. I sat down beside the telephone and waited confidently.

But the relief was only short-lived. Even as I sat waiting, it began slowly to be replaced by fear—a creeping fear, that seemed to presage a return of the stunned horror I had felt in the presence of the eerie shape. I turned in my chair, half- thinking to see some hideous nightmare thing making its way toward me from behind.

There was nothing there, and I knew even as I looked that there would be nothing to see. Nothing to see, and yet the fear crept upon me, increasingly stronger. It seemed it must soon overwhelm me—it seemed that it meant to overwhelm me, before I could talk to my friend!

And then, like hope flashing in the darkness of dread, the telephone rang! I staggered to my feet. It seemed I would never reach it, never be able to raise the receiver from the hook. Yet by an effort of will I did so.

"Hello Bob," I heard Howard's cheerful voice calling to me across the miles.

Yet I could not answer, for at that instant something seemed abruptly to be constricting my throat—something that might almost have been human fingers! For that first moment I could only gasp into the mouthpiece in an agonizing attempt to speak. Terror, blind, unreasoning terror overwhelmed me. When at last I did manage to speak it was only to whisper hoarsely:

"Howard... Howard... for God's sake come—quickly!..."

I could manage no more. I tore at my throat in a futile attempt to loosen the invisible fingers that were choking me into insensibility. Then, as if it were the work of a fiend angered at my partial success, the receiver ripped loose from my clutching fingers. The telephone was jerked sideways from its fastenings, as though dealt a smashing blow with a sledge-hammer! It hung dangling from the wall by its wires.

As I looked at it with startled eyes, the fingers, momentarily loosened, tightened again about my throat. There was a roaring in my ears; lights danced before my eyes. I felt myself falling... falling into space.

And as I fell, there dinned in my ears the mocking sound of fiendish laughter...

IT was nearly an hour later that I came back to consciousness to the sound of pounding at the door and the wildly ringing bell. I was sprawled upon the floor. My tongue was swollen and my throat parched and dry. I was weak and sick; yet for the first time in twelve hours my brain seemed perfectly clear and I felt master of myself. I struggled to my feet and feebly made my way to the door.

It was Howard Crandall. He had driven at top speed from Boston to reach me. His face reflected his concern and alarm as he saw mine. He entered quickly and closed the door behind him, supporting me, as he did so, with a strong hand under my arm. He aided me to a chair.

"Bob!" he exclaimed as he did so. "What the devil happened to you? Who... what was it?"

He eased me into the chair and stood over me, holding my pulse and regarding me with searching, worried eyes.

"I... I wish I really knew," I said weakly. "Damn it, Howard, am I ill... am I going mad? I'll tell you what's been happening here..."

Briefly, I told him. I was hardly begun before he had drawn up a chair, facing me, his gray eyes snapping with interest. He could hardly contain himself until I had finished.

"Good Lord, Bob!" he burst out then. "Why man..," He broke off, laid a hand on my shoulder, then said quietly. "No, Bob, you're not going mad by a long shot. And it isn't advice from me as a medical man that you need, but..."

He stopped again; it was obvious that only through great effort was he managing to retain some degree of professional calm. "I'm going to look around a bit," he said. "If I don't find..." And then he was off, almost at a run through the house.

I was still too weak to want to follow him, and I sat and waited for his return. He was gone a long time, and he ransacked the house from cellar to garret searching with truly scientific thoroughness as I realized later, for some slightest shred of evidence that would admit of the possibility of some natural explanation of the things that had occurred. But when he came back again his excitement was even more evident.

"Bob," he said, and there was a trace of awe in his voice, "there's something tremendous loose here... something astounding. It looks as if you have turned into a remarkably potent physical medium... Still," he added, and it seemed to me that even he showed a trace of fear then, "it can't be that either... It's more like the Charlotte Armand poltergeist case that Price recently reported in Arcachon, France, only more powerful—much more powerful..."

A little of my confidence had returned with his presence. "Good Lord, Howard," I said with a half smile, "what the devil are you trying to make out?"

HE did not smile. He sat silent for a long moment,

staring thoughtfully down, before he answered me. Then he said:

"Bob, I don't know. I don't myself admit the existence of

spirits. If we workers in psychical research didn't keep to our

attitude of scientific inquiry, God knows where we'd end—in

the madhouse, perhaps. What we try to do is to investigate the

actuality of such astounding things as have just happened here,

to see if there is any possible way in which they could have

happened naturally—explainably. Sometimes there

is—more often there is not. So there's one thing we can't

deny—that unbelievable, fearful things do happen, where

there is no possible natural explanation of their so happening.

There is no possible explanation unless we admit to the

existence of an unknown force not open to scientific

analysis."

"Good God," I said, and my voice sounded strangely flat and subdued. "Then you think—"

"I don't know," he interrupted tensely. "I'm a medical man; I could say you've been the victim of nervous hallucinations. But hallucinations don't rip telephones from the wall. I could even say that you're telling tall stories and up to silly trickery. Knowing you as I do, I know how absurd that theory is. But as a scientist interested in psychical research, I'm going to admit both possibilities and investigate myself."

He paused momentarily, and there was a troubled light in his eyes. "Meanwhile, Bob," he said then, "as a friend only, I'm going to advise you to leave this house—at once..."

I looked at him searchingly, a little astonished even after all that he had told me. "But Howard! You don't really think it's as bad as that!..." I think I was secretly hoping for reassurance.

He leaned over, placed a hand on my knee. "Yes, Bob," he answered. "I do... think it's as bad as that. What it is I don't know—but one thing I'm certain of—it means you no good. I mean to stay on and find the meaning of this mysterious force. I think I'll get Mrs. Crumb down from Boston and see what she can do. A lovely little old lady... She's not a professional medium—never accepts money. But she's a true sensitive and always gets results. Between us we should be able to track this thing down. Until we do—well, there's on need to mince matters, Bob—until we do, you're in danger of some sort—very real danger—as long as you stay in this house. I want you to leave for a few days. Take a run down to Boston—or better still, go over to Sylvia's. I don't think you'll have any trouble once outside this house..."

Howard's suggestion brought upon me again with renewed force my desire to be with Sylvia in this time of trouble—a desire that had not really left me since I had first thought of calling her. Yet, for a reason I could not then have put in words, I was afraid to call her. With some vague premonition of what was to come, I feared to have her near me...

But I wanted to take Howard's advice. I could go to Boston as he suggested. After all that had happened, it seemed wise and sane. And yet, I found myself hesitating.

"It's all very well for me to go packing off," I said, "but what about you and Mrs. Crumb? Don't you think you'd be taking quite a chance? This force, as you call it, doesn't strike me as a thing to be trifled with. Not judging by the power it's already shown... I'd much prefer you to forget the whole business and leave with me. I've troubled you enough."

"Indeed, no," he assured me. "We have thoroughly adequate ways of protecting ourselves against these so-called malign forces. But you run along and forget the whole thing for a few days. In the meantime, I want to see this thing through. I'm sure Mrs. Crumb will want to as well, once she knows what's happening."

I doubted then, and still do, that Howard had any real idea of the terrific power of the murderous force he so lightly challenged that day. I argued with him for some time; but his professional interest was strongly aroused and he would not listen to me. I soon came to realize that he would gladly risk any danger to witness a demonstration of the talents of the thing that had assailed me.

"In that case," I said flatly and yet finally, "I'm staying on, too. I'm seeing it through."

God knows I did not want to stay. I spoke those words in a voice that seemed not my own. Howard looked at me searchingly, and I think he felt the strangeness of my tones.

He argued to no avail. I would know that he had used physical force to propel me on the way. And yet, I am sure it would have helped not at all. Even then I knew without the thoughts forming into words that even had I gone away, I would have come back. I knew that I was not myself any longer; that an invader had entered my mind, my very soul; an invader so strong that he could direct my actions and the words I spoke. At times in my strength I might fight him off—yet sooner or later, when I was off guard or weakened, he would come back. Already my will had ceased to be my own. And so I stayed. Stayed on to learn that the horrors which had been my lot were but paltry things compared to those to come...

IT was just getting dusk when a knock came at my bedroom

door. It was Howard. Having failed to persuade me to leave the

house, he had at last administered a sedative and packed me off

to bed. I had slept soundly, and awoke much refreshed.

While I slept he had sent Mason—who still knew nothing of what was transpiring in the house but fifty yards removed from his quarters—to Boston with a note to Mrs. Crumb. She had returned with him. And now, Howard assured me, she was in the process of preparing an excellent dinner for the three of us.

I bathed and dressed, then went downstairs to meet Mrs. Crumb. Pleasant odors were wafting from the kitchen, and there I found her—a sweet-faced little old lady with white hair and kindly blue eyes. Her hand-clasp was surprisingly strong and firm, and for the time it seemed to drive away the feeling of dread and unnamable horror which had so long possessed me. There was confidence in that hand-clasp—confidence of her ability to deal with the enigmatic thing which was dominating me.

But a short time before, Howard informed me, she had fallen into an involuntary trance. She had received a warning from one whom she called her guide, that a powerful intelligence was attempting to establish connection.

"So now your mind can rest at peace, Mr. Mercer," she assured me. "We will bring this restless spirit to terms."

She, at least, apparently had no doubts as to the nature of the force, in contrast to Howard's conservatism in labeling it. Somehow, this appealed to me. She accepted the existence of malignant spirits with a calmness which robbed them of much of their menace.

Poor woman! How tragically ignorant she was of the boundless horrors beyond the gates at which she knocked!

After dinner we repaired to the library. We seated ourselves before the log fire Howard had built in the fireplace, Howard and I on the divan and Mrs. Crumb in a chair on our left.

She sat down and closed her eyes at once. Howard and I sat in silence, smoking our after-dinner cigars and watching her. In a few moments her breathing became heavy and regular and she slumped far down in her chair, seemingly in deep slumber. But at last she stirred restlessly, as if troubled by dreams, and muttered something unintelligible. Her fingers fluttered on the arms of the chair. I looked at Howard; he nodded.

"It's coming through," he said.

Abruptly, Mrs. Crumb straightened in her chair, as if awakening, although her eyelids remained closed. For a moment her lips moved inaudibly. Then, seemingly, she spoke. But the voice she spoke in was so different from her own that, involuntarily, I looked about the room to see what stranger was present—although the sounds obviously were coming from her lips.

The voice was clear and loud, and definitely that of a man!

"I am John Alcott, Mrs. Crumb's control," it said. "I am having great difficulty in coming through to you because of the presence of a very powerful intelligence:—a cruel intelligence. I must warn you—"

Abruptly, the voice had stopped, as if a telephone plug had been pulled from its jack! Mrs. Crumb again slumped in her chair, seemingly deep in slumber; and for a time silence reigned in the room, broken only by the crackling of the fire on the hearth. But to me that silence was filled with dreadful portent of nameless evil.

Then, without warning, a second voice crashed into the silence—a voice much more powerfully masculine than the first. This time Mrs. Crumb did not change her position, nor did her lips appear to be moving, although strangely, the voice seemed to proceed from her mouth.

"The time has come for vengeance!" cried the voice. Uncannily, it seemed to fill the room with reverberations and echoes. "I have waited long. At last I have developed my power to the point where no living person may thwart, me. Be warned! At last I have found the instrument of my vengeance. He is mine! Let him alone!"

The voice paused, yet the echoes rolled eerily about the room. I felt coming over me once more the nameless terror which had shadowed me for so many hours. Now it seemed certain that it would engulf me. Angered by my helplessness, my body was yet drained of every ounce of strength and will to fight. I turned to Howard for strength—but momentarily even his face reflected the stark horror which shone in my eyes. Then he shrugged and nodded reassuringly.

The voice returned. "You are skeptical of my power," it said in ominous tones that would have seemed theatrical but for the force of conviction they carried. "I shall strive to convince you. But whether or no, remember—" and here the voice rose to a roar that dinned in my ears like the trumpets of Doom—"I have a serious and fatal mission to perform. Interference means death!"

The voice ended in a thunderclap which seemed to shake the house to its foundations!

WITH a low cry, Howard sprang to his feet and stood

peering about the room, as if expecting to find someone lurking

in the shadows. He strode to the wall and flicked the switch,

turning on the lights in the chandelier. Obviously, we three were

the only occupants of the room...

Howard came back and resumed his seat. "Extraordinary, extraordinary," he muttered thoughtfully. "Never saw anything like it."

I waited in silence for a further word from him; but he seemed wrapped in thought, unconscious of my anguish. I could bear it no longer.

"Howard!" I burst out. "For God's sake, what does it mean? Am I—?"

A crash drowned my words. At the far side of the room, an entire row of books had seemingly been dashed from the top rack to the floor!

I wanted to scream madly, to dash from this house of horror. Yet I stood helpless, chained by an unthinkable dread.

Howard, with an appearance of calm, walked over to inspect the books and the wall. Barely had he satisfied himself that no explainable agency had been responsible for the crash, when chaos descended.

One after another—singly, at first, and at last, all those remaining in a final crescendo of destruction, every movable thing in the room on shelves, hanging from the walls or resting on the tables, was swept crashing to the floor. Books, vases, bric-à-brac, pictures, lamps—all crashed about us—as if we were experiencing an earthquake. Or, as if the end of the world had come...

Then again there was silence. I was trembling in every limb. Looking into my eyes, Howard most have seen the sheer terror written there. Perhaps hoping to quiet my fears, he shrugged his shoulders with seeming indifference, and spoke.

"You have done a great deal of childish damage, force or spirit or whatever you are," he said, "but that is all. It is not difficult to exercise strange powers over inanimate objects; but what will this avail you? You need not think you can control my friend, or any living being, and cause them to work whatever fiendish ends you pursue."

A laugh came—the laugh that was that of a fiend! It rose higher, higher, louder than ever I had heard it before, till it filled the room. Then the voice spoke again.

"Why," it said, "do you think Robert Mercer did not leave this house today as you advised him? Why did he not go elsewhere, where my power for the time at least would not have been so strong over him? Do you think he did not want to go? He did... but I willed otherwise! His will is helpless in my hands—helpless until my vengeance is fulfilled!"

Involuntarily, Howard shuddered; but he quickly gained control of himself. "Not," he answered, "while Mrs. Crumb and myself are here to battle with him against you."

"Fool?" said the voice. "You do not know against what powers you have pitted your poor strength. Leave this house, while life is in your body and reason in your brain. Death—and worse than death—will be your portion if you strive to divert my descendant from the charge I shall put upon him."

And when Howard made no reply, the voice added: "If still you do not fear my power, then tomorrow you will. If both you interferers do not leave this house—tonight—then a greater horror than you can even dream of is in store for you. Tonight!..."

And with a sound that was like the sweeping of a hungry hurricane, the voice was gone!

We were brought back to reality by a startled cry from Mrs. Crumb. She had awakened from her trance to see the shambles about her. Apprehension was on her kindly old face.

"What does this mean?" she asked dazedly.

Howard explained to her all that had happened. When he finished, Mrs. Crumb closed her eyes for a moment, and I could see a shudder shake her small frame.

"It is dreadful," she said. "It is a truly malevolent spirit. It may be we can do nothing. I had a terrible vision—oh, it was far worse than anything I have ever experienced. Hands—horrible, bony hands—I could see nothing else. They came to me out of the dark, then receded. Each time they came closer. At last I felt their cold, cruel touch upon my throat..."

"You must go at once, Mrs. Crumb!" I burst out. "Both of you must go. You can do nothing for me. You must go to save yourselves!"

She looked up at me. A great fear lighted her clear, blue eyes, yet she shook her head.

"Oh, no," she said. "We could not leave you—in his grip. Never. We have a great task before us. We may not be successful, but we must strive to reason with this discarnate being. He must be turned from his terrible purpose..."

She paused, looked off into space with that pathetically frightened expression lurking in the depths of her eyes.

"Ah, those hands," she whispered. "I am afraid. They were so long and curved and white—so strong and cruel..." She gave a little, choking gasp, and finished almost inaudibly, "The—the—the ends of the fingers seemed to have been dipped in blood..."

IT was late, that night, when at last we retired to our separate rooms, for such troubled sleep as we could gain. For hours, it seemed, I had argued with Howard and the kindly Mrs. Crumb, begged them to leave this dwelling of mine that had become a house of horror. All to no avail...

"I have devoted my life to this work," Mrs. Crumb said firmly. "I am not going to leave it because danger threatens."

And Howard growled: "I'm going to stick with you, Bob, and see this thing through. I'd be a fine physician to let myself be frightened by a lot of melodramatic threats from apparently sourceless voices. It's the most amazing thing I could ever hope to meet with in a lifetime of psychic research, and I want to track it down. This house, where the strange force first manifested itself, is the place to do it. Furthermore, it's obvious that whatever the thing is, it's mesmerized you to the point where you can't leave the house—and I'm certainly not going to leave you here to fight it out alone. That's final, Bob. Now, let's get on to bed..."

Frankly, the thought of spending another night in that house terrified me; I was certain that sleep would be next to impossible. But Howard and Mrs. Crumb were able to soothe my fears a little. Both were confident—foolishly confident, God knows!—that there would be no further manifestations that night. Both felt that on the morrow they might be able to exorcise the evil influence which seemed to have enveloped me like a shroud, leaving me a terror-stricken weakling. How they proposed to accomplish this I do not know. Mrs. Crumb, I remember, mentioned the possibility of "enlisting the aid of good spirits." Howard did not explain. Yet their confidence, their very self-assurance in the face of the threat, calmed me a little. As much from a spirit of bravado as otherwise, I found myself at last going to my room and retiring.

And strangely enough, I slept at once...

In retrospect, I can fully understand the evil source of that suddenly-induced slumber. Ah, how trustfully, how blindly we mortals relinquish consciousness in the seductive arms of Morpheus. We regard it as a friend—a priceless boon that "knits up the raveled sleeve of care," giving sanctuary from the troubles of the day!

But I have cause to know sleep as a traitor—as a siren who can lure away the guardsmen of the inner temple in volition and leave it unprotected against the invasion of the shadowy enemies of mankind—who live in the dark and whose only weapons are the unconscious bodies of living men.

For a long time my sleep was troubled by vague dreams. They were fearful dreams—nightmares of twisting shapes which no words couched by humankind can express. Nightmares in which I seemed to be one with chaos and confusion, and one with the whirling cosmos. All the while, terror had me tightly in its grip—and yet I did not awaken.

Then, with the abruptness of a lightning flash, the whirling vagueness took form and color, became a picture.

I seemed to see the room in which Mrs. Crumb was sleeping—and yet I could not have said that I was there, in the room. On the bed I could see the little old lady, peacefully sleeping. The vision came closer.

As that happened, Mrs. Crumb seemed to awaken with a start. She opened her eyes. I could see into their depths. In them stark terror was written! Terror—and something else I could not name.

I followed their stricken gaze—and knew then what else it was I could not name.

For out of nothingness two hands had come, two hands that crept slowly upon her. They were hideous hands, long and curved, white and somehow cruel hands. And the ends of the fingers were red—as if they had been dipped in blood!

Closer they came to her. She opened her mouth as if to scream—but the scream was but a choking gasp. For already the hands were about her throat, throttling the breath of life from her body.

I wanted to cry out, to tear at those encircling hands. But I was helpless, seemingly incorporeal; I could do nothing. I stood, silent and unmoving, while life was torn from the helpless little woman's body; watched as that body relaxed in the lassitude of death. Then the hands left her throat.

And as they moved away, back into nothingness, I screamed aloud. For I knew in the dream that the hands were my own!

I CAME awake, then I found myself in my bed. My pajamas

were dripping with sweat, but fear was a cold and clutching thing

in my breast.

As I came awake, the door burst open and Howard rushed in. His sleek hair was tousled and there was worry in his eyes.

"Bob!" he burst out. Then relief spread over his features as he saw me still in bed. "What was it? I was awake and heard you cry out. Nightmares, I suppose..."

"Mrs. Crumb!" I cried in answer. "Has she—what has happened to her?"

He looked puzzled. "Mrs. Crumb? Why, I'm sure she's all right. Her door was closed when I passed it. She's sleeping. What have you been dreaming?"

So real was the terror of the moments just past that I leapt out of bed. I would have rushed past Howard and out the door, had he not restrained me.

"Calm yourself, old fellow," he said. "You've been having nightmares and you're not awake yet."

"But Howard!" I cried. "I dreamed that a horrible thing happened to her... to Mrs. Crumb. We must go to her—now!"

He tried to hold my arm, muttered something about not disturbing the poor woman's sleep. But I shook off his detaining hand. I rushed madly down the hall, stopped at the door of Mrs. Crumb's room. I pounded madly, and when no answer came, I tried to open it.

It did not move. I realized, then, that it was locked—soundly bolted from the inside with a modern lock. And yet, that knowledge gave me no comfort. I threw all my weight against the door.

Howard had followed. He must have sensed some reason now, in the terror he had seen in my eyes, realized that no answer had come from the occupant of the room. For he placed his sturdy shoulder beside mine.

After tense moments, the door crashed inward. We rushed to the bed.

The horror of that moment will live in my memory as long as my body lives. My reason totters when I think of it, and because of it, and one other moment that followed, all that I ask of death is forgetfulness. Yet knowing what I do now of the life beyond, I know that death can never bring me that one boon. It is the final curse put upon humanity by the forces that evolved our existence.

Ghastly gray in the faint moonlight that sifted in through the window, Mrs. Crumb's face stared up at us. It was horribly contorted with agony and terror. The little old lady was dead. She had been throttled, and her neck still bore the marks of the fingers that had choked her!

Something snapped in my brain at the sight. I collapsed to the floor as blackness overwhelmed me...

WHEN I recovered consciousness a few moments later, I was

back in my bed. Howard sat in a chair at my side, watching me

anxiously. As soon as he saw that I was awake he began talking to

me, quietly and steadily.

"You must get a grip on yourself. Bob," were his first words. "This is a terrible thing that has happened; but our only salvation lies in keeping our heads clear and our courage up..."

He talked on... Then he did not know? It was plain he did not know... I rose up in bed and stared at him. He broke off abruptly and looked at me in vague alarm.

"You fool!" I screamed. "Don't you realize that I killed her?"

For a moment Howard was thunderstruck; but he quickly recovered from his surprise. "Nonsense," he said. "The door was locked on the inside. Didn't we nearly break our shoulders opening it?..."

I sank back in the bed with a bitter laugh.

"And you," I said, "are Research Officer for the Massachusetts Society for Psychical Research!"

How I cursed myself then, for having trusted his and Mrs. Crumb's theories regarding the mysteries they dabbled in. Why had I not followed the dictates of an inner conviction which, but a few hours before, had warned me that my only safety lay in having myself locked up—in a prison, if necessary—until I could be sure that I was no longer haunted by the discarnate demon that hovered about me? Had I done so, Mrs. Crumb might have been saved. Now...

"You're quite right, Bob," Howard was saying. "I deserve the rebuke. Yet I still do not believe that you killed her, that you are a murderer."

Strangely, it seemed then, in that moment the face of the woman I loved, of Sylvia Blanding, flashed before my eyes. It seemed to give me strength. I climbed out of bed. "In any case," I said with more firmness than I had been able to muster for hours, "you've done enough coddling of me. There's been murder in this house, and I lie in bed, treated as if I were an invalid."

Howard nodded. "Again you're right.

I had planned to notify the authorities of Mrs. Crumb's death as soon as it seemed safe to leave you. I'll drive in with Mason, since the phone isn't working..."

"And I," I said with decision, "am going with you. I shall turn myself over to the police, and confess to the murder of Mrs. Crumb. That will force them to lock me up."

"But Bob!" Howard protested. "You can't do that! You didn't kill her... and even if you did, you weren't responsible at the time..."

"Perhaps not," I answered. "And neither is a mad dog responsible for his killings. Howard, at present I'm as dangerous as a mad dog. Remember that Mrs. Crumb was killed only because she stood in the way; but this fiendish force that is driving me has a darker goal in sight. He will kill—or force me to kill—again. Someone—some person entirely innocent of wrongdoing, perhaps, will not be safe until I am behind bars. It is the only way."

For a time Howard continued to protest; but in the end he was forced reluctantly to agree. It still lacked an hour of dawn, but we felt that no time should be lost. He went to his room to dress, while I did the same. I was putting on my coat as I heard his footsteps on the stairs. He was on his way down to call Mason.

I stepped out in the hall to join him—and stopped dead in my tracks.

Moving toward me down the dimly-lighted hallway, with sinister. sureness, was the ghostly, luminous shape I had seen the preceding night!

I turned to flee; I opened my mouth to cry out; and then it was upon me.

It struck me not as a hard object, but as a thing without body. It struck with the force of light, and it seemed that the light of a million worlds was about me, was ringing in my ears and filling my body and taking possession of me...

I CANNOT say that unconsciousness claimed me then, though I would to God that it had. It was unconsciousness of a sort, and yet I was conscious. I can only describe it by saying that another being seemed to have entered my body, my soul. And yet, in a still far corner of my brain, there lurked a remnant of the self, of the soul that was I. And lurking there, it knew dimly the things that my body did, knew the horror of them, and yet was powerless to control it!

At first I remember only that an indescribable wave of cunning seemed to sweep over me, urge me into action. It was that cunning, I know—though it is but dimly remembered now—that caused me to slip softly down the back stairs of my house, unknown to Howard, while he was on his way to call Mason. It was that cunning which caused me soundlessly to open the door, to slip into the night with the quiet of a creeping snake. And then I was free.

Free—for what? I did not know then—and yet I knew. I knew that I was on my way to consummate a greater horror than yet had been my lot. I knew that the force which had me in its grip was now driving me to the fulfillment of the destiny to which it had appointed me.

That little part of me that still lurked in my brain knew these things, and a great fear was upon it. The fear of the thing I was about to do, though I knew not what it was, was a greater fear than I had ever known before. And yet, feeling this, the part that was I was powerless to act!

I do not know the path I took that night. I did not know then. I remember the feel of thick grass under my feet as I made my way through fields and meadows no longer familiar. Sometimes I walked, sometimes I ran, stumblingly; but always I went forward, with the certainty of doom.

The grayness that precedes the dawn seemed to have transformed the leafless trees in the fields into gaunt specters, and they reached out their naked branches toward me as I passed, like skeleton fingers. I remember that. I remember dimly a garden wall that I stealthily slipped over, and a locked door that I somehow opened. And stairs that I climbed with the whispering silence of a shadow.

These things I remember but dimly, as they registered faintly on the small corner of my brain that was myself, and they did not seem what I later knew them to be. But from this point on all things that happened came more clearly to me; and as they did so the stark terror in me mounted. Yet I went on...

I was in a room now, into which the morning grayness was creeping like the pale face of death. In the far corner was a bed, and on it a sleeping form; I crossed to it and bent over the sleeping one. And my hands were closing about a smooth, white throat, slowly, inexorably closing.

I looked into the face; and in a blinding flash I remembered. And as if the flood-gates of hell had been loosed upon me, horror swept over me in a torrent.

For the face of the sleeper was the face of Sylvia Blanding! And my hands were about her throat!

GOD in heaven! What words are there to describe the

horror of that moment? I tried to cry out, to warn her, and my

words were soundless. I tried to draw my hands away from that

slim white throat, yet they were held there as if in a vise.

Slowly they closed more tightly, and I was powerless to stop

them!

Then—horror greater than all horrors—Sylvia awakened! Her blue eyes opened and she looked up at me with a nameless fear in them. Looked up and saw that it was I!

Oh, God! I thought. Why can I not die—die spiritually and physically—at this moment? Wh-why are the lurking horrors that dwell beyond the pale of death permitted to visit the innocent living? Why can I not call out to her—if only to tell her before she passes through the Shadow that it was not I who killed her?

I tried—God knows I tried. And I spoke. Yet I swear it was not I who said these words that I heard myself saying, in a voice that was not my own:

"You die, Sylvia Blanding—and with you dies the Blanding line! May you all burn in hell!"

These words came from my mouth, yet they were not mine! And as they were ended, and I looked down into the fear-stricken eyes of my beloved, a laugh sounded in the room. It was the laugh I had heard before—the laugh of a fiend from hell.

Somehow that sound filled me with such horror that the small place in my brain seemed to grow a little larger. And slowly, a little strength that was my own flowed into me. My mouth opened again, and words that were my own came forth.

"God help me!" I cried.

And almost with the words, I felt my strength grow greater, and my hands drew slowly away from Sylvia's throat.

Yet even as they moved away, I saw other hands appear to take their place. These others seemed to come from my own body, to extend from my own hands. They were white and cruel, and the ends of the fingers were red as if tipped with blood!"

While I tried with all the strength of my will and body to fight those hands, to struggle with them and pull them away, their grip grew tighter. I saw Sylvia struggle feebly, saw her terror-filled eyes distend as her white brow darkened.

Dimly I realized then the thing that I must do to save Sylvia. Those clutching fingers were not mine—yet they came from me and without me they would be powerless. I must destroy myself!

Not all my strength could tear those hands away, but the power of movement had returned to me. My eyes focused on a weighted brass candlestick that sat on a stand beside the bed, and I knew what to do.

As in a dream I picked it up. I raised it high above my head. Silently I prayed for strength to do this thing.

And with all the power of my body, I sent the heavy brass stick crashing against my own skull!

There was only blackness then...

CONSCIOUSNESS came back to me but slowly. I saw first

that I was in bed, and then that I was in a room strange to me. I

felt a cool hand upon my brow, and looked up into Sylvia's

eyes!

For a moment I felt that I must have died, and that Sylvia, too, had died. But as I saw the troubled smile on her lips as she looked down at me, I knew we still lived. I knew before Sylvia spoke that I had succeeded only in making myself unconscious with the blow, but that it had been enough—that the hands had left Sylvia's throat even as I sank to the floor.

"Sylvia!" I said. "Thank God...!"

She smiled now more happily. "You must be very quiet, darling," she whispered. "You fractured your skull—to save me. But Howard says you're coming through..." She leaned down and kissed me, and I knew the first happiness I had known since the awful nightmare began.

Howard entered the room then, and his eyes lighted up when he saw that I was conscious. "I knew you'd make it, old man," he said with manifest relief.

He had trailed me to Sylvia's, I learned then, too late to stop me. But it was he who had spirited me away into the hills, and with Sylvia's help had tended me.

There was a dull throbbing in my brain, but aside from that I seemed well. I raised myself on my elbows and looked about me. Across the room from me was a mantel, and above it a mirror. Looking in it, I beheld a strange being that was myself.

I was not yet thirty then. But beneath the bandage that encircled my brow, deep lines were written across my face. And my once black hair was white!

Seeing this, full realization of all that had happened flooded back to me. I thought of Mrs. Crumb—and I sat bolt upright in bed.

"Howard!" I burst out. "What is there for me to do? Shall I give myself to the police?"

Sylvia's face paled at my words. Howard thought a long time before he answered. "No," he said at last, "not that. Above all, not that. I have had one session with the police. They think you mad; they half thought me mad as well. If you gave yourself to them, they would lock you in a madhouse.

"And that," he said, "would be hell indeed, for you are sane. The world may think otherwise, but I know you are not mad.

"There is but one thing to do, Bob—and that is to flee. Escape to another country. I will help you."

"And I," said Sylvia, "shall go with you, Bob darling."

"No," I protested. "You must not go. Sylvia. You must be far away. You don't know—"

"Howard has told me—everything," she said quietly.

"But this force... this fiend... he might make me kill you yet..."

"I shall go with you," she repeated.

THANKS to Howard, we made our way to this remote spot.

Here we were married, Sylvia and I, and here we live simply,

almost in solitude. I have tried to forget the horror of those

two nights and a day, and with Sylvia I have found happiness, and

almost I have found peace.

Together we have delved into the darker pages of my family history... More than a hundred years ago, there lived a fiend who bore the name of Mercer. He lived with the devil in him, and he died with a curse on his lips for the Blandings, and for their children who came after them...

You might say that it was but the blood of this fiend, running through my veins, that caused me to do the things I did. But Howard, who has seen destruction wrought, and heard the voice shaking the very walls, would not believe you. Sylvia, who has felt and seen those cruel white hands about her throat, would not believe you. And I, who have gone through two nights and a day of hell on earth, I would not believe you.

I think I have beaten the fiend. Though he still desires Sylvia's life, I am sure that he can never force my hands about her white throat again. With but frail human strength, I have beaten him.

Have I? Sometimes of an evening, when Sylvia is singing about her tasks inside our cabin, and I sit alone outside the door, with the smell of the pines in my nostrils and my eyes on the distant hills, I wonder... Will he come back to claim me in the end?

And so, though Sylvia and I are happy, I can never quite say that I have found peace...