RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

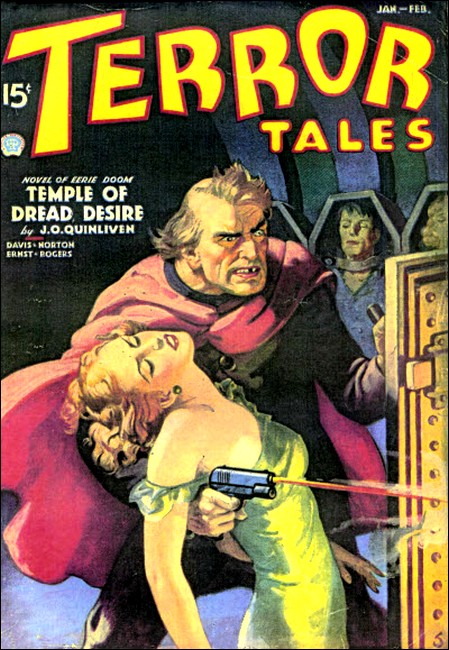

Terror Tales, Jan-Feb 1937, with "Flowers That Bloom In Hell"

Eerily, horribly tragic was the manner in which the beautiful women of Blackhawk Lake disappeared from their homes and the arms of their loved ones. But more terrible by far was the manner in which they returned, one by one, bearing on their minds and souls the ineradicable imprint of deathless horror—and on their bodies the ghastly flowers that bloom in hell!

I KNOW it was the tragedy at Crow's-Nest that crystallized the feeling in my heart—the knowledge in my brain—that something unutterably dreadful was gaining control of Balisande and Blackhawk Lake. I had felt it and sensed it before. After that I knew it.

It was Louise's screams, her repeated shrieks that something was holding her, coming from the infernal depths of the blazing cottage that drove the cold iron of that terrible conviction into my heart. Something was holding her! But what could it be—in a place that had become a raging furnace?

Bob had gone down to the boat landing. His little sneak-box had drifted away from its moorings and he had borrowed my canoe to go out and get it. He was in the middle of the lake when he first saw the blaze. I saw it before he did, I think—and yet by the time I got there, it was hopeless to think of being able to live long enough to dash in there and rescue Louise. God! The horror of having to stand out there and listen to her screams and be unable to do anything about it! I took off my coat, wrapped it about my head and made a mad plunge toward the front door. The heat was like a stone wall, repelling me. The flames billowed out fifteen feet in front of the house, and in two seconds my coat had shriveled to a cinder—like a cobweb in front of a blow- torch. I fell back, my hair aflame, my brows and eyelashes singed off and my face, arms and shoulders blistered raw...

Then Bob came.

I dread telling about it. I've tried to banish the fearful picture from my mind—but it will go with me to my grave.

Louise had stopped shrieking that something was holding her, and whatever it was had apparently released her. How in God's name she ever lived long enough to get to the window, we'll never know; but the flames were probably confined mostly to the walls of the house, and perhaps the place she had been inside was relatively free from fire. At any rate, her face, blackened, tortured, appeared suddenly at the side window near the front of the house, and her arms reached out through the flames piteously toward Bob.

I was practically prostrated from my burns or I would have grabbed him. But I couldn't even get started toward him, and in an instant he had hurled himself at the window. I saw him swallowed up in flames—and closed my eyes in agony at the sight.

Perhaps from excess of mental and physical pain I passed out for a few moments. At any rate, it seemed only an instant had passed when I opened my eyes at the sound of terrible, soul- chilling laughter above me. I looked up, and there was Bob—or what had been Bob. It was a blackened, seared body of a man with scraps of flaming clothing still clinging to his limbs. His face was a dreadful distorted mask of mindless anguish. The sounds he was making were like idiot laughter, and he held something toward me which he grasped in his right hand. It was a moment before I realized what the thing was—just a moment. And then I was drowned in the terrible sickness that comes with plethora of horror...

Bob had reached his wife. He had tried to pull her out of that raging inferno by her arm... Her arm...

THAT was the first—a dreadful warning to the rest of us.

But one does not run from intangible, half-superstitious

fear—not in these supposedly sophisticated days. We could

not explain to ourselves why Louise had been shrieking that

something was holding her—and so we made our minds close

themselves to the enigma, which is the way of the minds of human

beings. Nature abhors a vacuum, and modern intelligence cannot

tolerate unanswerable questions. We have a deep-rooted instinct

to ignore those things which balk our ready, facile

explanations.

We looked at each other with veiled questions in our eyes, but none dared to put those questions into words—and it was not until Hobart Lindon's wife disappeared, and then horribly came back to him, that we knew this thing must be faced squarely and unequivocally...

Hobart Lindon and his charming blonde wife lived in the next house south along the shore from Crow's-Nest, which had been poor Louise and Bob Kingsley's home. One night at dinner time Lindon, wearing a faintly worried expression, knocked at the door and inquired of Grace whether she had seen Harriet, his wife, that day. I heard Grace tell him that she had met her down at the beach that afternoon, and then, taking the paper I had been reading with me, I went to the door.

"What's the matter, Hobe?" I asked.

"Oh, nothing—nothing..." he muttered. "I—I just thought it rather strange when she didn't show up at dinner time. I mean, she didn't leave any word with the girl, or phone, or anything— you know."

He was much more worried than he seemed—I sensed that. I knew something else, too: he was having the same sort of a cold, hard feeling in the pit of his stomach that I was having—only intensified a hundred times, probably—since it was his wife.

"Oh... she probably got all absorbed in one of those impromptu bridge games that are always getting started around here," I said, trying to sound reassuring. "She'll probably have returned by the time you get home."

That was perfectly reasonable. It was entirely likely—a thousand-to-one bet, as far as the probabilities were concerned. And yet I didn't believe a word of it. I knew—knew—something terrible had happened to Harriet Lindon. But poor Hobart grasped at the suggestion with pathetic eagerness. He bade us a hasty good-night and almost ran away down the path.

I stood there for a moment, watching his hurrying figure disappear in the dusk. Then I went back into the living room, put down my paper, donned my coat and went out after him, tossing the word over my shoulder to Grace that I would "be back in a minute."

As I went out the door I heard her murmur, "Oh, God grant she is safe!"

I WALKED in without knocking. Lindon, who was sitting, staring

into space as I came into the living room, looked up at me with a

drawn expression on his face.

"Steve," he said, "what in hell's wrong with this place?"

"Why—nothing that I know of, Hobe," I hedged. "What, exactly, do you mean?"

He threw out his hands in a distressful gesture. "Oh, damned if I know," he said. "Maybe I'm nuts; but ever since Louise Kingsley died I've had a feeling that this place is—well—haunted. I feel as if we're living under a threat of some kind..."

He paused and looked at me helplessly, as though at a loss as to how to go on.

"Well," I answered, "of course that was a horrible affair. It made everybody sick and depressed, naturally—"

"Steve," he interrupted suddenly, "did you ever hear of a guy by the name of Blauvelt who used to live in the valley, out there, before they made a lake out of it?"

I gave a start of recognition. It was Jake, the woodcutter who lived on the island in the middle of Blackhawk Lake, who had told me of "old Blauvelt." I had gone to his house in the hope of persuading him to adz out some beams for the downstairs rooms of the home I was building for Grace and myself on the south shore of the lake. He had greeted me as, I later learned, he was in the habit of greeting all newcomers to Balisande.

"Ye better not settle here," he had said. "This place's got old Blauvelt's curse onto it. He's gonna git to r'arin' pretty soon— and it won't be no fittin' place to live after that. There'll be hell to pay, mister."

I tried to question him, make him explain the vague nonsense he was mumbling, but I soon gave it up. It was obvious to me, at the time, that Jake was not quite "all there." It was strange, though, the depressing effect on my nerves and spirit his words had had.

"I have heard the name mentioned recently," I told Lindon.

He nodded. "He is supposed to have disappeared just before the valley was flooded to make Blackhawk Lake," he said. "He had lived there in his hut down on the south slope of the hill that is now Blackhawk Island. He was a peculiar duck, no one knows how old, but at least eighty, and is supposed to have been a fire- worshipper."

"A—what?" I interjected.

"A fire-worshipper—sort of a Zoroastrian, you know. He lived like a hermit, and is supposed by the natives to have spent all his time practicing some sort of black art and studying esoteric books which filled his cabin. He positively refused to sell out, when the promoters of Balisande approached him, so they had the titles examined for that particular tract, found that Blauvelt had just squatted there and that it was still open to homesteading. They had enough influence, of course, to get around a little thing like that—so old Blauvelt had to get out."

He paused and looked at me with a peculiar expression that I could not analyze at the moment.

"Understand," he went on, "I'm no believer in ghosts—or anything in that line. I'm just telling you this yarn as it was told to me...

"Well, the story goes that old Blauvelt didn't move out, after all. Or if he did, he came back again—so the natives hereabouts think. Anyhow, he is supposed to have died in his cabin when Wine River was diverted to flood the valley. They claim that as soon as the water hit the cabin a column of smoke and fire shot thirty feet into the air, and that the water over the spot where the cabin had stood boiled for three days and nights. The natives say that old Blauvelt put his curse on the lake, and that the smoke and fire signified the manner in which that curse would be executed..."

"Oh, but that's poppy-cock," I broke in. "There's one of those old hermits in practically every community in the mountains, I'll wager. And the natives are so backward they're hardly less superstitious than the original settlers. You can't believe—"

"As I told you," interrupted Lindon, "I take no stock in the supernatural aspects of the things—but there's no question about the smoke and fire. I talked to a number of people who saw it— among them, one of the engineers who put the project through. His explanation of it was that the water had hit an unsuspected deposit of phosphorus pentoxide."

"Well," I said, "that would seem to make any other explanation unnecessary."

"Yes," began Lindon, "except that—"

Suddenly his voice went dead, his eyes, focused on something behind me in the doorway, went wide with unmistakable and unutterable horror, and his face was abruptly drained of every suggestion of color.

I felt the short hairs on the back of my neck stirring, and icy panic suddenly envelop my body. I knew in that instant that I would give every cent I possessed if I could escape having to look upon the thing at which Hobart Lindon was staring—but as though enslaved by a dreadful, irresistible lodestone, my head began to turn...

It was seconds before I identified the woman who stood in the doorway. Her perfect body was completely nude, and she stood there as motionless as a marble statue. On her face was an expression of mingled agony and terror that distorted it almost beyond anything human, but she spoke no word, made no sound of any kind. And between her full, firm breasts was a smudge of blood. In the center of that smudge, as though it grew there and nourished its roots in the woman's breast, was a brilliantly colored yellow-and-scarlet flower.

Then I recognized the woman—it was Harriet Lindon. The flower, I knew, was a specimen of the rare fleur de feu—flower of fire!

DR. SYMES looked at me gravely through his glasses. He was a tall, serious man with even more of an air of self-possession than the usual deliberate calm of his profession.

"The laceration in the integument between the breasts," he said, "was caused by the insertion of a red-hot needle, about one-sixteenth of an inch in diameter. It was pressed down at a vertical angle for a distance of fully two inches until the instrument came in contact with the sternum. The stem of the flower was then thrust into the hole."

"God!" I whispered. "That fiend—what monster could have conceived of a thing like that?"

The physician's serious eyes continued to hold my own. "There were weals across the back," he went on, "which were obviously caused by a whip. As to the condition of Mrs. Lindon's mind, I am not yet prepared to make a positive diagnosis. I have called in Calverly and Henshaw of the Princeton Foundation for consultation. I have never encountered anything quite like it either in practice or my studies. It might be a rare form of traumatic shock—but the syndrome offers many startling peculiarities. The strange, automatic gesture of raising her fingers to her lips every time she is questioned as to the identity of her assailants, for instance, presupposes a residual memory-image which is inconsistent with the apparent and otherwise complete amnesia. However," he added, with a sudden curious change of timbre in his voice, "I am quite certain that the loss of memory is genuine, and not simulated."

I gave a start and looked at him searchingly. "You say that," I said, "as though you had half-expected Mrs. Lindon to have shammed amnesia."

For the first time Dr. Symes' eyes wavered. He cleared his throat and looked down at the floor.

"As you remarked," he said, "there is a fiend, or a monster, behind this sad affair. Mrs. Lindon could not have been blamed even if she had attempted to fake loss of memory. Regard for her husband's state of mind would almost have compelled her to do so, had it not actually been induced..."

"You mean—"

Still with his eyes on the floor, Dr. Symes nodded. "The worst part of Mrs. Lindon's experience left traces only a physician would recognize," he said quietly, but with an undercurrent of deadly wrath behind his words. "But there is no possible doubt as to their nature and what they signify. We may at once discard any hypothesis of a supernatural agency at work here. No ghost could be as brutal—or as lustful—as Mrs. Lindon's attacker!"

I could not be as sure of this as Dr. Symes seemed to be. Despite the assurances of my reason, my twentieth-century skepticism, I could not forget the story which had been recited to me by Hobart Lindon. It is the type of story that has occurred and recurred many times in the history of the human race. Could all of these stories then, have been nothing more than myths, without any trace of factual foundation? Why, if that were actually the case, have they been so persistent in cropping up in some form or another in every country and in every age?

But we could proceed only on the hypothesis that our enemy, or enemies, were nothing more than rapacious, diabolical human beings.

A HALF-DOZEN of us had gathered in the Sages' office that

afternoon. Neither of the bereaved husbands was present. Poor Bob

Kingsley was confined to a sanatorium, where already his sanity

had been despaired of. Hobart Lindon was prostrated from grief

and shock. There were Finnley Challenger, a chemist, Robert Huff,

the violinist, Hal Sanger, a construction engineer, and a couple

of other men with whom I had only a bowing acquaintance, besides

myself. We all lived on the side of the lake adjacent to the

Kingsley and Lindon properties. We arrived singly and in pairs,

and took seats in the anteroom, as the Sages' secretary reported

that they were both busy.

The Sages—Pearson, and his brother Joseph—were the owners and promoters of Balisande and Blackhawk Lake. They had bought up half a county, built a dam, and within two years' time created one of the outstanding beauty-spots of the state. The lake was about three miles long, half as wide, and contained a fairly large island in its center—the top of what had been a knob hill. The brothers Sage then divided up the environs of the lake, and the island, into 40-foot lots and began selling them.

They had certain restrictions as to whom they would sell the lots—some of which we all knew about, and others which we did not suspect until later. They had other requirements regarding the type and cost of the houses that were to be built—but, being excellent architects gifted with fairly consistent good taste, these requirements were obviously the things that were largely responsible for making Blackhawk Lake the perfect beauty-spot it eventually turned out to be. It was in all its physical aspects, at least, a nearly perfect residential community. The water of the lake was not potable—having a strange, metallic flavor, the cause of which had so far evaded analysis; but this was of no consequence as we had a separate water supply.

We sat there and discussed the recent tragedies at Balisande in low tones for a few minutes, and presently the door to the Sages' private offices opened, and a stocky, florid individual with private detective written all over him came out, closely followed by Pearson Sage.

"Just leave it to me, Mr. Sage," the former was saying. "I'll run this bird to earth, if he's still around here."

"And don't forget the special investigation on the other party," replied Sage. "You might start with old Jake, the woodcutter on the island. He seems to know more about him than anyone else, hereabouts—although Jake, himself, is a little cracked, I'm afraid..."

They shook hands, and Sage turned to us. "Good afternoon gentlemen," he said, then, raising his voice, "Joe, come on out here."

Joseph Sage appeared smiling, and greeted us effusively. He was so different in his physical aspects and character from Pearson that it was difficult to believe that the two were even distantly related. He was small, thin, with lank dark hair brushed back in an unsuccessful attempt to cover his bald crown, and his manner was that of an oily, obsequious Uriah Heep. Pearson, on the other hand was tall, big-boned with a florid complexion and a loud-voiced, domineering manner. He was the "front" for the pair—but it was pretty generally understood that Joseph furnished the brains of the partnership.

Without waiting for any word from us, Pearson started haranguing us.

"I know you have come regarding the recent distressing incidents that have taken place down at the lake," he said, "and I'm happy to inform you, gentlemen, that everything has already been taken care of. I have retained the services of one of the country's outstanding firms of private detectives, ordered them to spare no expense in bringing the guilty party or parties to light. The gentleman whom you just saw leaving is head of the firm, and is personally taking charge. We expect—"

"What steps have you taken to protect us against possible further activities of the criminals?" interrupted Challenger. "Have you hired any guards? The local police are incompetent."

"Mr. Murphy, the gentleman I was referring to, and his firm have undertaken that aspect of the matter, also," replied Pearson Sage smoothly. "I think we need have no fears, gentlemen, as to—"

Suddenly the outer door of the anteroom swung open to reveal the figure of a young Negress in the costume of a housemaid. I recognized her as an employee of Robert Huff's. Her eyes, rolling wildly until their whites showed in startling contrast to her dark skin, darted over us, until they were found and came to rest on Huff's figure. Then she just stood there, wordlessly staring at the man, with abject terror like a grotesque mask on her face.

As though he had a premonition of what was to come, Robert Huff rose shakily to his feet and took a single step toward the girl.

"What—what's happened?" he gasped, his voice a harsh whisper.

Slowly, her glaring eyes still fixed on Huff's face, the girl raised her right hand. We saw, then, what had escaped our notice before. That hand held a bloody stemmed flower—a crimson and yellow fleur de feu!

"Mis' Huff," said the girl haltingly, "she done disappear 'bout two hours ago. I thought she's gone next do' an' neveh reckoned no hahm had come to her—ontil I foun' dis flowah on de front po'ch—"

CLARA HUFF had disappeared in broad daylight, and before I

reached my home that evening, I found that Harriet Lindon's

frantic nurse had phoned Dr. Symes with the report that her

patient was missing from her bed. The nurse said she had gone to

the bathroom for some hot water, had been gone not more than two

minutes at the most, and returned to find that Harriet had

disappeared. On the bed there lay another of the blood-stained

fire flowers.

Finnley Challenger came to my house early that evening—shortly after dinner. He stood at the door, his lean, tanned face containing a curious mixture of fear and embarrassment.

"I hate to ask you to do this, Steve," he said, "but would you and Grace mind staying with us, tonight? You see—Meg is frightfully worried and, well, you know how women are." He laughed a little ruefully. "I don't think she's afraid I can't take care of her alone—but you see, our house is next to the Huff's, and..." He stopped in obvious embarrassment. I understood. Beginning with Crow's-Nest on top of the hill, the houses visited by disaster had in each instance been the next in line south to the last visited. First the Kingsleys, then the Lindons and the Huffs—now... Challenger's house was third in line down the hill from Crow's-Nest. I couldn't blame him for his anxiety.

"Of course we'll come, Finn," I said.

And a half-hour later the four of us were seated about a bridge table at the Challengers' pretending that it was important not to make an opening bid with less than two and a half quick tricks. In my hip pocket reposed my old service Colt .45, making an uncomfortable but reassuring bulge; and I knew that a .32 target pistol was stuck in Challenger's belt beneath his coat.

We played rottenly, nobody even making a contract in the first hour—so we were relieved when Meg suggested that we give up and go to bed.

The room the Challengers assigned to us was directly across the hall from their own. Grace and I disrobed quickly and crawled into bed, both of us worn out, and, at least in my own case, oppressed with a strange, unusual lethargy. My senses were not so dulled, however, that I forgot to put my gun under my pillow.

I was asleep almost immediately, my last conscious impression being the knowledge that Grace's round, cool arms were about my neck and her soft, delicious body pressed close to my own. Will I ever live long enough to expiate that careless, besotted lapse into unconsciousness, when my every faculty should have been more alert than ever before in my life? Will the bitter canker of self-accusation ever leave my heart because on that night, of all nights, I did not remain awake and watchful at the side of the one who meant more than all the rest of the world put together to me? I know that it will not. I know that nothing I can do will... But enough of that...

How long I slept I do not know—nor, for that matter, can I definitely say that I really awoke while the things I am about to record transpired. The whole episode occurred in such a dream- like, unreal fashion, leaving such a vague, unworldly impression in my brain, that I cannot definitely say that I was awake while it was happening.

At first I was vaguely aware of a strange sort of dead white light emanating from a point near the door of our bedchamber—the door which I had securely locked before we had retired. Next, that light seemed to coalesce and solidify into the outlines of a softly luminous body. The body moved slowly toward the bed on which Grace and I lay, locked in each other's embrace. It bent over, and I felt soft fingers gently loosening my arms from about my wife's body; felt Grace's arms slipping from about my neck.

That act was like a dull wedge forcing itself slowly and painfully through the thick layers of my stupor, not quite reaching the seat of my consciousness but at least arousing my brain to a somewhat sharper perceptiveness. I seemed to see the woman more clearly, then. I could not recognize her face, although I knew that it was beautiful, and that it wore an infinitely sad, indescribably pitiful expression. I knew that her white, glowing body was nude—and that in a red smudge between her naked, pointed breasts a terrible flower bloomed in dreadful luxuriance...

A DULL, phantasmal hell swirled in my brain. Unutterable

shrieks, prayers and curses churned within my dead, sleep-locked

body— impotently, futilely, silently. Grace, my beloved, my

adored wife was being torn from my arms—and I was utterly

powerless to move a muscle in her defense! She was being abducted

to some unimaginable hell by one who had come back from it,

perhaps at the behest of its dread master, to claim her as

another doomed victim of her own ghastly fate!

Then I was aware of another presence in the room—and I knew that I was looking upon a being that had no right to show itself upon this earth. The thing seemed to have the shadowy lineaments of a human body—but there was nothing remotely human about its head! That head was a great, bulbous sphere which gleamed, like the body of the woman, with a dull, dead light. It was a head without features, save for a black, yawning hole in its center which never closed or opened further, or changed its shape in any way.

The thing advanced, now, to the side of the bed on which my wife lay. Roughly, as if impatient of her slowness, it thrust aside the woman who stood there and, bending down, thrust its arms about Grace's lax body and lifted it effortlessly to its shoulders. Then it whirled about, and made off through the door of the bedchamber, followed slowly by the nude woman. The door closed, and black maggots of madness swarmed over my brain, stifling the last vestiges of partial consciousness that struggled inside my skull, plunging me into the inky depths of nightmare-ridden oblivion...

And it was dawn before full consciousness returned to me.

My waking sensation was of pain in my right arm—but that was soon forgotten as horrible memory flooded back over my mind, and I frantically reached out to Grace's side of the bed. It was empty!

It had not been a dream, then—a horrible phantasy born of my fears...

I sprang out of bed and ran with quaking knees to the door. It was still locked. I unbolted it, flung it open, and dashed across the hall to the door of the Challengers' bedroom. It, too, was locked, and there was no response to my frantic pounding. I sprang back and hurled my body against its panels. It burst open and I fell inside, headlong. Scrambling to my feet I rushed to the bed and looked down...

I have seen a number of gruesome corpses, but never a more horrible one than the one my distended eyes glared at in that moment. I knew that the body must be that of Finnley Challenger— but there was nothing about its face to tell me so. There was no face. There was only a bloody pulp in which no features save a few glaringly white teeth which still clung to the lower jaw were discernible. The rest was a mass of red, minced flesh and grey, blood-streaked brain matter. Of Meg Challenger there was no sign...

IT was the act of an insane man—the beating I gave Pearson Sage that day. But in the extremity of my anguish and terror for Grace I was indeed insane. And the calm urbanity with which he met my wild torrents of verbal abuse and hysterical accusations was too much for me. I slugged him unmercifully until his secretary had called frantically for the police, and they were pounding up the stairs.

A coldness suddenly settled on my brain, then, and I realized that I must at all costs avoid even temporary arrest. Every moment was precious beyond price, until I had located my beloved Grace—and I was firmly convinced that if she were to be found, I must do it. I was completely without confidence in the "nationally known firm of detectives" which Pearson had hired.

Precipitately I fled down the fire-escape, and was off in my car before the police could regain the sidewalk. I abandoned the machine on a side road near my home, and made off through the woods covering the western slope of the valley. I resolved to set up a vigil that would last until I had either found Grace—or been forced to give her up as lost forever.

Throughout the day I sat there on the slope of the hill, my eyes roving over the valley and the lake in a never ceasing scrutiny. Hardly a person was to be seen. Occasionally the burly figure of a derby-hatted man would appear, poking about in an aimless fashion—undoubtedly one of the Sages' hired operatives. The residents of the Lake District, however, were obviously staying close indoors. I hoped bitterly that their vigilance would be more faithful than mine had been.

Late in the afternoon I saw the figures of a man and a woman emerge from the house to the south of mine, climb hurriedly into an automobile, and make off toward the east at a terrific rate of speed. Very wisely, Ted Weymouth and his wife had decided to join in the exodus to the city. I cursed myself for not having insisted that Grace and I do likewise...

AS night fell the panic that had been festering in my heart

ever since Grace's disappearance began to reach insupportable

proportions. I had steeled myself to motionlessness throughout

the day because I was sure that there was nothing to gain through

any other course. I dared not move about too freely, lest I be

picked up on the assault warrant that had undoubtedly been sworn

out against me by Pearson Sage, and, on the other hand, my only

chance to accomplish anything of value lay in the admittedly

remote possibility that I might be able to observe something from

this lookout point which would develop a clue.

Forlorn hope—but what else?

But with the coming of darkness, even that possibility vanished. However, it would now be possible for me to move about in comparative safety, and it occurred to me that the best starting point on my search was the spot toward which Pearson Sage had directed the detective, Murphy—the woodcutter's hut.

Accordingly, as soon as darkness had closed down over the valley, I began descending the slope.

Before I reached the bottom of the hill, the moon rose above the rim of the valley, and cast its pale, eerie beams over the accursed lake. I paused, looking down at that ill-omened pool of water with tears blinding my eyes. How delighted Grace and I had been with the beauty of this place—never guessing what utter foulness it cloaked! And now that its sinister nature had been revealed, how was I to force it to give up its terrible secret?

Somehow, I never doubted that the key to the horrible riddle lay, in fact, in the lake. And now, as though in confirmation of that theory, a weird, blood-chilling scene began to be unfolded before my eyes.

My attention was suddenly caught by the appearance of a black, spherical object which popped abruptly out of the water about ten yards from the shore. In the silvery path the moonlight made across the lake, it moved steadily toward the beach, rising gradually higher and higher above the surface as it progressed forward. Presently, the entire sphere was above water, and I saw that a vaguely man-shaped form supported it. My heart leaped as I identified it with the dreamlike apparition I had seen the night before. Behind it, then, appeared in succession a number of other forms. These, however, were much smaller, and while roughly spherical in shape, seemed to be of some shining, plastic material. Then, as these latter shapes gradually emerged above the surface of the water and moved toward the edge of the lake, I saw that they were supported by the white, gleaming bodies of nude women!

There were three of these nude figures, all with their heads encased in what, at that distance, appeared to be sacks of black rubber, and bringing up the rear was another sphere-headed body like the first.

My heart was throbbing in my chest like a kettle drum. There could be no possible doubt that those female figures belonged to three of the beautiful women—perhaps my own Grace among them— who had so mysteriously disappeared within the past thirty-six hours. Whatever horrible things had been done to them, at least they all lived. There was hope... hope...

I HAD to exert every ounce of my will power to keep from

dashing headlong at that weird group; but I knew that I must wait

until the purpose of the captors became apparent. Besides, I had

no assurance that Grace was one of the three women, and in the

event that she was not, I might be able to locate the place where

she had been hidden by quietly trailing them.

The group paused on the shore of the lake, and the two sphere- headed men—it was clear, now, that those spheres were nothing more than diving helmets—proceeded to remove the bag-like arrangements from the heads of their captives. This finished, the group turned and proceeded westward along the shore, the men in the diving helmets leading and bringing up the rear as before.

As quietly as possible, I crept down the side of the hill, fearful that I would lose sight of the group before I learned its destination. Then I saw how I could cut in and head it off, if it kept its original direction, by angling down a small gully that ran into the lake. Taking the risk of losing sight of the weird procession for a few moments, I jumped into the gully, and ran as noiselessly as I could toward the lake. In a few moments I emerged a few yards from the shore, and took a post behind a large maple that grew near the mouth of the gully.

For a few panicky seconds I thought that the group had turned off into the woods, but soon the reassuring sound of feet scuffing softly through the sand reached my ears, and I crouched tensely in my hiding place, my eyes riveted on the point where the sounds indicated they would soon appear.

Soon the bulbous-headed leader came around the bend in the shore, and after him, still in single file, came the ivory-bodied women, walking with a peculiar mechanical listlessness, their eyes, discernible now in the white light of the moon, fixed and staring as those of a sleepwalker. On the breast of each was the horrid red and yellow flower that was the emblem of their hideous bondage. But Grace was not among them.

I cursed savagely beneath my breath and reached for my gun. Then I hesitated. Was not, after all, my first plan the wiser? Would it not be more intelligent to let these people lead me to their destination? Was it not possible that an overt act of mine at this time might result in my losing Grace forever, when a little patience might be rewarded by my reaching her side?

But then a surprising thing happened. The group suddenly came to a halt, and with one accord turned and faced outward toward the lake. Then they just stood there without making a sound or a movement, the gleaming forms of the women lined up between their grotesque guards, as though engaged in some weird, silent ceremony.

My scalp crawled with the eerie conviction that I was witnessing something that was strange beyond human comprehension. What human mind could conceive of the things that had been done in Balisande within the past two days? There was an inescapably supernormal quality to everything that had happened—an air of unearthliness about the whole ghastly proceeding which defied the ability of any merely mortal agency to cope with it. I was oppressed with a strange and panicky feeling of helplessness—of bitter despair and the sense of inevitable failure...

Perhaps ten minutes passed, without a sign or sound of movement from the strange assemblage on the beach. Then, from afar— apparently from the edge of Blackhawk Island in the center of the lake, a tiny beam of light made its appearance. It gleamed for a moment, and then disappeared, only to flash on and off again twice more—after which it remained off.

As though it had been a signal which they were awaiting, the group turned and silently filed away in the direction from which they had come.

As soon as they had disappeared around the bend of the shore, I emerged from my hiding place and cautiously followed them. I kept a dozen yards in their rear, clinging close to the shadows at the edge of the woods.

Presently they paused at the point from which I had seen them so strangely emerge from the water, and the leading guard proceeded to replace the sacks on the heads of the women. This completed, the file turned and, led by one of the men in diving helmets, walked straight out into the lake.

A sudden plan now presented itself to me, and I tensed my muscles for action. I waited until the bulb-like head of the leader had disappeared beneath the surface of the water, and then I sprang from my cover and rushed into the water in the wake of the rear guard. I reached him without his giving the least sign that he had discovered my presence, and savagely jabbed my gun into his back.

He came to a stop immediately and slowly turned around until he was facing me. I peered into the window of his helmet, and made a gesture with my left hand meant to indicate that he was to remove his headgear. Instead of doing so, however, he made a sudden lunge at me, and attempted to strike the gun from my grip.

If I could have done so, I would have merely stunned him with a blow on the head from my pistol—but his helmet made that impossible, and I dared not lose too much time struggling with the fellow. Deliberately I swung my gun up and shot him through the left shoulder.

As the fellow collapsed, I dragged him toward the shore until we had reached shallow water. There I hastily removed his helmet and donned it myself. With a silent prayer that I had not been too long, I hurriedly waded off in the direction in which the procession had disappeared, and soon I was walking along the bottom of the lake in Stygian darkness, completely immersed in the water.

I stumbled against unseen obstructions, moving with the lagging, aggravating pace of a person in a dream, and soon was without any sense of direction or assurance that I was actually following my quarry.

Suddenly, however, a dim light showed in front of me and slightly to my left. The light rapidly increased in power, and took the form, blurred and indistinct though it was, as seen through the water, of a lighted open doorway. The illumination which it cast through the water lit up the forms of two of the women, the other woman and the leading guard, having apparently disappeared. One of the women now stepped through the doorway, the other remaining where she was, and the door immediately closed, shutting off the light and plunging everything into dense darkness. Fearful of losing my orientation I too remained motionless, confident that I had guessed the nature of this lighted doorway, and that it would open twice more—to admit the woman and then myself, masquerading as the guard now lying senseless on the beach.

In a few moments my deductions proved correct. The door opened, the woman stepped through, and the door closed again. I moved up to the submarine portal, and after an interval it again swung open. I stepped into a small, brilliantly lighted, water- filled room.

AS I had suspected, the tiny chamber was a water lock, and no sooner had the heavy, mechanically operated door swung into place behind me than there was a distant, muffled sound of pounding pumps, and the level of the water in the room began to lower. In a short time it was below my shoulders, and I reached up to remove the helmet.

However, a sudden thought halted my movements. Undoubtedly I was being watched, and the helmet furnished me with at least the rudiments of disguise.

I waited motionless, therefore, until the water had all been pumped out of the room. After that there was a prolonged interval during which nothing happened, and I began to have the uneasy conviction that my ruse had been discovered. I saw, now, that there was another door directly in front of me, and about five feet from the floor I discovered a small, thick pane of glass set into it, behind which it seemed to me I could discern a pair of malevolent eyes glaring at me.

Then a thought struck me that sent my heart into my mouth. This helmet disguise of mine was no disguise at all! The clothes I wore differed radically from those worn by the man from whom I had wrested the helmet. I was dressed in white shirt and tweed trousers. He had worn dungarees and an undershirt...

If anything else were needed to convince me that I had betrayed myself, it was the continued delay in admitting me beyond that second portal. Doubtless my captors were debating on the most expeditious manner of disposing of me. Would they simply reflood the chamber, wait until the small oxygen tank attached to my helmet had exhausted itself, and thus kill me by drowning? Or would they...

Abruptly my suspense was ended by the opening of the door. Getting a grip on my nerves, I promptly advanced through the portal. It swung closed behind me.

I found myself confronted by a gaunt, beady-eyed individual with a long ragged white beard. He held an automatic pistol in his skeletal but steady hand, and the gun was pointed squarely at my heart.

For a moment the man's small glinting eyes surveyed me with a cold, searching scrutiny. Then the bearded lips shrank back to reveal blackened and broken teeth in a sardonic, diabolical grin. The gaunt left hand raised with an unmistakable gesture toward my helmet.

I raised my arms and began to lift the device from my shoulders— and my captor cannily moved several yards away from me, as though he had divined my suddenly formed intention of hurling the heavy object at him as soon as I had it off my head.

His move defeated my purpose. It would be suicidal to attempt it now; so I dropped the helmet at my feet.

I was in another small chamber, but little larger than the lock. Most of the space was taken up with a pump, an electric motor to operate it, and several diver's helmets scattered about on the floor. But this room had stone walls and a concrete ceiling, both sweating and discolored by moisture.

Again my captor subjected me to a careful scrutiny, his small eyes squinting until they were almost lost in the wrinkles which surrounded them. At last he straightened a little, wagged his gun at me.

"Turn around," he grunted in a hoarse, dry voice, "with your hands up!"

I obeyed, and heard his slithering footsteps advancing over the stony floor toward my back. A quick, light hand swept over my hips, paused at the bulge in my right hip pocket, extracted my automatic.

"All right," came the grating voice again, "now lie down flat on your face—and be very sure that the least attempt of resistance on your part will mean a bullet through your brain."

I complied, but held my muscles tense in readiness to take advantage of the least show of relaxed attention on the part of my captor. At his direction, I placed my hands behind me with wrists crossed after I had lain down face to the floor. I could feel him fumbling the loop of a leather thong over my wrists, and knew that he was using only one hand for the job. It was plain that he was taking no chances, and was keeping me covered with the gun in his other hand. Jerking the thong tight he next ran a loop about my ankles. Then he put down his gun and secured both ankles and wrists with many turns of the thongs.

Helpless as a mummy, I was grasped under the arms and dragged to a door in the opposite wall. This door, also, had a window in it, somewhat larger than the one in the other, and my captor now lifted me up and propped my body against the door jamb so that I could look through the window into the room beyond.

The old man chuckled raspingly. "Reckon ye got a right to see the next operation," he croaked. "Hope ye enjoy it!"

He chuckled again, and paying no attention to my wild curses he picked up the helmet I had worn, opened the door carefully, just wide enough to permit the passage of his body without throwing my own off balance, and went inside, closing the door behind him. I saw him shuffle across the large, whitewashed, brilliantly lighted room and disappear up a crude staircase at the far end.

The room beyond the door was almost bare of furnishings. In its center, under a bank of brilliant, high-wattage globes, was a nickel and porcelain-finish operating table. Beside it on a smaller table was an assortment of bottles, and beside that a centrifuge on its own stand. On the other side of the table was a glazed cabinet full of shining surgical instruments. Next to it was a steam sterilizer. The place had the appearance of a well- equipped operating theatre—and the sight of it aroused such dreadful forebodings in me that I began to shake with a dreadful palsy of terror, and the sweat oozed from every pore. What terrible sight was I doomed to witness in this ghastly place?

IT could not have been more than a few minutes, although it

seemed hours, before, suddenly, two white-robed and masked

figures appeared descending the stairs. The second, from his bent

form, and the beard straggling below his gauze mask, was

obviously the old man who had captured me. But the first was a

tall, straight figure whose black eyes, jutting forehead, and

thick black hair were faintly familiar as he looked in my

direction. He stared at me for a moment through the window, then

frowned and turned back to the old man, seeming to address him,

although no sound penetrated through the door. The old man

shrugged, and the two of them walked across the room, disappeared

through another door in the right wall. In a few moments they

emerged, bearing between them the stumbling, apparently half-

unconscious form of a nude woman.

The girl's head drooped forward, the hair obscuring her face, and it was not until, turned toward me, the two men had lifted her feebly struggling form to the operating table, that my worst fears were realized—I recognized—my wife.

I had never ceased for a moment to fight against my bonds, although the only result of my struggles was that the leather thongs had cut deep into my wrists. Now, in my frenzy of terror and rage, I tried to slam my body against the door, and almost lost my balance. I recovered, stared with horrible fascination at the dreadful scene about to unfold before my eyes.

The old man was already busy with ether cone and bottle, acting as anesthetist. In a few moments he removed the cone, and the other man, who meantime had clipped and shaved the hair from the right front occipital region of Grace's skull, removed from the instrument cabinet a tray containing a colorless fluid, from which his rubber-gloved hand took a small scalpel. Handing the tray to the old man, he bent over Grace's head and made three quick strokes.

I shivered with sickening horror as the knife flashed twice more, and the fiendish surgeon tossed it into the cabinet. From the tray, then, he took a number of small surgical clips, and with them pulled back the flap of flesh he had loosened from Grace's scalp. Next he took up a small circular instrument—and I groaned aloud. That instrument, I knew, was a trephining saw!

This, then, was the manner in which the brains of the beautiful victims of this devil were robbed of their memories, rendered incapable of describing what had been done to them—or who had been guilty of the horrible deeds! A spot on their brains had been touched—perhaps removed—and from that time forward their minds would be blank of all that had preceded. Three women had suffered this dreadful mutilation—and now, Grace...

Perhaps I half fainted in that moment. At any rate I lost my balance and fell to the floor. As I did so, landing in a doubled- over position, I felt my arms slip downward on my hips. Instantly my brain cleared, and I thrust downward harder. Within a few moments I had forced the sweat and blood-slippery bonds on my wrists far down on my hands, straining with all my strength against the leverage furnished by my hips. Suddenly, with a flaying of the skin from the back of my hands, the thongs slipped off—and in the next instant I was clawing wildly at the bonds on my ankles. Freed of those, I hurled myself against the door—and instantly knew that I could never break through it. It was of solid steel, as firmly fixed in its frame as the portal of a bank vault. The window would not permit the passage of my body, even if I should break the glass.

Madly I glared through that window, and cursed wildly as the diabolical surgeon wielded his saw. This was not death but worse than death for the one whose life I prized immeasurably above my own. Grace, in a few minutes, would become a replica of the poor, mindless things I had seen emerge from the lake. Her eyes would mirror only the suffering, speechless vacancy that had been in the eyes of Harriet Lindon. She would no longer be my wife—she would not even know me, if she ever saw me again. Better—far better that we should both die now than live like that!

A sudden desperate thought whirled me about, drew my eyes to the levers and switches arranged on the opposite wall. These, I knew, controlled the water lock and the pumps. Supposing I opened the doors of the lock, allowed the chamber I was in to become flooded—then smashed the window of the door between me and the operating room. In a few seconds the entire apartment would be flooded. Grace and I would die a clean, relatively painless death—and our enemies—they would die with us!

With a mad cry I sprang for the levers...

THE water was rising about my hips. My eyes remained riveted

to my wife's form. I was bidding her an anguished, silent

farewell, when a sudden splashing caused me to turn. There,

waist-deep in water, stood Meg Challenger, her wide blue eyes

staring at me vacantly, her nude body braced against the torrent

rushing about her.

I was at a loss to account for her presence, until I realized that she must have strayed from the party I had come in with, and had only found her way in after I had opened the doors of the lock. She carried her helmet under one arm, and as I watched, she lifted it slowly in front of her in both hands, and turning to the left, walked slowly across the flooded floor with the vague, dreamlike motions of a sleep-walker.

The water was now above the top of the window, which I broke with a sharp blow of my fist. The water flooded into the room beyond as though a dozen fire hydrants had released it. I cast a fleeting glance inside, then turned back to Meg. Somehow, although I felt I would rather have Grace die than go on living as a mindless automaton, I did not consider that I had the right to make such a decision for Challenger's wife. I started toward her—and came to a sudden halt.

Meg had gone to a sort of cupboard in the left wall of the room, had opened it and was placing her helmet inside. But apparently she became aware that there was yet need for wearing the helmet. She stared at the water with a puzzled, intent expression on her face, and then, with a vague uncertain gesture, withdrew it from the shelf and began fumblingly to try to replace it over her head.

I forced my way through the water to her side and quickly adjusted the helmet for her. Then I dashed back to the window, a wild thought beginning to take form in my brain. It was obvious that Meg's mind was not completely gone. As soon as this, after her operation, she was yet able to follow a primitive course of reasoning and react to it with appropriate logic. Had I, perhaps, been too hasty in assuming that the minds of those girls had been completely ruined? Was I sacrificing Grace's life needlessly— when it was possible that, in time, she might be brought back to her former normal state?

As I glared through the opening, I saw the surgeon and the old man in retreat before the flood, running up the stairs, leaving the senseless body of my wife on the table. I yelled to them, but in a moment they had burst open the trap door at the head of the stairs and disappeared to the regions above, leaving Grace to a fate that her own husband had devised. I battered at the door senselessly, crying out to Grace in the hopeless effort to rouse her. Yet even if I had been able to, how could she escape from that watery trap...?

Then a sudden idea occurred to me, and taking a deep breath, I thrust my head and right arm under the water where it was flowing through the window, and groped about on the inside surface of the door until my hand touched the knob. Turning it, I was swung violently into the room as the door flew open under the pressure of the water behind it, and then was hurled headlong to the floor.

Due to the increased area of expansion, the water level now sharply dropped, but it was pouring in furiously through the lock, and I knew that it was only a matter of minutes before the entire chamber would be flooded to the ceiling.

As I struggled to my feet, I heard the sound of shots coming from above, but I had no time to speculate on them. I hurled my body through the water and gained Grace's side.

She was still under the influence of the anesthetic, and my heart froze as I saw that her skull had been cut through in a complete circle the size of a half-dollar. The flap of scalp was still held back by surgical clips—to move her in that condition would almost certainly result in death, or an irremediable injury to her brain.

The water had now reached my knees. My frantic eyes fell on a bottle labeled "Dakin's Solution", which I knew to be a safe and effective sterilizer. Clipping a wad of gauze from a roll in the cabinet, I saturated it with the solution, carefully bathed the wound in my wife's scalp. Then, removing the clips, I replaced the flap over the section that had been trephined, covered it with gauze, cotton, and surgeon's plaster.

No time, now, to attempt a crude job of suturing. The water was above my waist before I had finished bandaging Grace's head. That done, I lowered her gently back on the table. Then I plunged through the water in the direction of the smaller room. I searched in vain for Meg, but apparently she had succeeded in escaping through the lock. Then I forced my way over to the cupboard, flung open the door, and discovered that there were two helmets left. I snatched them up and dashed back into the operating room, only to come to a sudden halt just inside the doorway.

Standing there by Grace's body, still clad in his gown and mask, a revolver clasped in his hand and pointing directly at my chest, stood the fiendish surgeon.

THE water swirled around us, creeping steadily higher up our

chests. Then the man spoke.

"Bring me those helmets!"

Slowly I advanced toward him, holding the helmets in either hand above the level of the water. He took the helmet out of my extended left hand and tucked it under his right arm, taking care that the movement of clamping it against his side did not spoil his aim. Then he reached for the helmet in my right hand.

But in handing the first helmet to him I had prepared myself. The movement had permitted me to thrust my left shoulder forward and my right one back without exciting his suspicions. Now, with all my strength, I hurled the helmet in my right hand straight at his head.

He tried to duck—and at the same moment pulled the trigger. I felt a sudden searing pain in my left shoulder. He dropped the helmet, slumped against the cabinet. In the next instant I was upon him. I wrenched the gun from his nerveless fingers, but he held up his hand in a dazed, weak gesture, and knowing that now he was harmless, I forbore to shoot him. I hurled the gun across the flooded room, and diving beneath the water, retrieved the two helmets.

The surface of the operating table was already awash. Quickly I raised Grace to a sitting position and adjusted one of the helmets about her shoulders. I prepared to don my own. Then I halted at the sound of my late adversary's voice.

"The other women are in there, if you care to rescue them, too," he said, and as I turned I saw that he was pointing feebly toward the door from which I had seen him and the old man bring forth Grace. Then I gave a start. He had taken off his gauze mask and his features were revealed. The man was Dr. Symes!

"If you hurry," he continued, "you can get them out and upstairs. The trap door is locked from this side."

I finished putting on my helmet as I strode toward the door he had indicated. It opened inwards; I turned the knob and it flew back with a crash. The water poured in. However, the lights were still burning, and I could see two nude women—Clara Huff and Harriet Lindon—standing in the middle of the room, clasped in each other's arms and trying to brace themselves against the torrent, expressions of vague, puzzled alarm on their faces. Grasping each by an arm, I hurried them out of the room, released them at the door, and strode over to the operating table. I caught up Grace's lax form and made for the trap door at the top of the stairway.

Clara and Harriet followed me mechanically. I slid back the bolt on the door without difficulty, and thrusting upward threw it open. I glanced back at Dr. Symes just in time to see the renegade physician raise a scalpel high in the air before plunging it deep into his heart. He sank below the level of the water immediately. A second later a hint of red appeared on the surface...

DAWN was breaking as Pearson Sage and I drove back from the

hospital where I had left Grace. He and his brother, and a

coterie of detectives had greeted us as we emerged from the

flooded operating room. The trap-door, I found, had opened into

the kitchen of the wood-cutter's cottage—which had been a

blind for the nefarious operations Pearson was now explaining in

detail.

"Symes tried to buy the lake from me almost as soon as it was finished," said Sage. "He had discovered that the explosion which occurred when the water hit old Blauvelt's cottage had been due to a chemical reaction set up by a deposit of a rare and very valuable mineral salt. This salt is readily soluble in water, and the whole lake, therefore, had become a tremendously valuable reservoir. Jake said that Symes had already conducted secret experiments with sufferers from arteriosclerosis and sclerotic hearts, and had wonderful success.

"Disappointed in his efforts to buy the lake, except at a price he could not afford, he determined to force down its value by instituting a reign of terror. He imported crook workmen from New York, bought old Jake's silence and aid, and constructed that underground operating room and marine lock under Jake's house. Then he had Jake spread the story about old Blauvelt and his curse, and started in on a series of abductions which were pulled off in a manner to give weight to the supernatural theory.

"Murphy soon decided that something was screwy about Jake's place, and set a close watch on it. He was careless enough to let himself be seen last night, and Symes ordered the women sent to the mainland until he found out what Murphy was up to. You saw them and followed them back. Grace wasn't with them because she was still unconscious from the drug they had given her.

"When we raided the place about ten, we caught all the workmen and Jake—but Symes escaped through the trap door which we didn't locate until you emerged from it. He apparently chose suicide rather than escape drowning with you and face the charges of murder that would be brought against him. Jake will get the works for chopping up Challenger with his hatchet. He had to kill Finn because he awoke him in trying to stick a hypodermic full of morphine into him. Symes succeeded in your case—being, of course, more expert at the process..."

Sage paused, and I felt his glance as, for a moment, he took his eyes from the road.

"By the way, Purcell," he said in a sympathetic tone. "What did they say at the hospital about—Grace?"

"Too early to tell much about it yet," I replied. "The doctor thinks no great damage was done—but we won't know for awhile..."

There are some things too painful, too personal, to confide to even the most intimate friends...

It has been three months since that dawn. Grace is back with me, now, and almost daily she shows improvement. Her mind is clear, perfectly sane—but her memory is still practically blank. She remembers certain incidents of her childhood, and daily she is remembering more of them. It is as though her memory is beginning at the start of her life to rebuild itself. But I have tried in vain to arouse recognition of later events in her life. To all suggestions I have given her she has shown no reaction whatever... To all, that is, save one: Mention of that ghastly room beneath the lake, or of the diabolical Dr. Symes, or of the fire flowers, invariably produces the same reaction. Her eyes become dull, as were the eyes of the first three victims of the renegade physician's villainy; her features fall into an expression of intense terror and suffering—and slowly a finger rises to her lips in the age-old gesture of silence...

But this is the memory I had hoped would never return to her...