(At a writing-desk in Sandgate)

"Are you a Polygamist?"

"Are you an Anarchist?"

The questions seem impertinent. They are part of a long paper of interrogations I must answer satisfactorily if I am to be regarded as a desirable alien to enter the United States of America. I want very much to pass that great statue of Liberty illuminating the World (from a central position in New York Harbor), in order to see things in its light, to talk to certain people, to appreciate certain atmospheres, and so I resist the provocation to answer impertinently. I do not even volunteer that I do not smoke and am a total abstainer; on which points it would seem the States as a whole still keep an open mind. I am full of curiosity about America, I am possessed by a problem I feel I cannot adequately discuss even with myself except over there, and I must go even at the price of coming to a decision upon the theoretically open questions these two inquiries raise.

My problem I know will seem ridiculous and monstrous when I give it in all its stark disproportions—attacked by me with my equipment it will call up an image of an elephant assailed by an ant who has not even mastered Jiu-jitsu—but at any rate I've come to it in a natural sort of way and it is one I must, for my own peace of mind, make some kind of attempt upon, even if at last it means no more than the ant crawling in an exploratory way hither and thither over that vast unconscious carcass and finally getting down and going away. That may be rather good for the ant, and the experience may be of interest to other ants, however infinitesimal from the point of view of the elephant, the final value of his investigation may be. And this tremendous problem in my case and now in this—simply; What is going to happen to the United States of America in the next thirty years or so?

I do not know if the reader has ever happened upon any books or writings of mine before, but if, what is highly probable, he has not, he may be curious to know how it is that any human being should be running about in so colossally an interrogative state of mind. (For even the present inquiry is by no means my maximum limit). And the explanation is to be found a little in a mental idiosyncrasy perhaps, but much more in the development of a special way of thinking, of a habit of mind.

That habit of mind may be indicated by a proposition that, with a fine air of discovery, I threw out some years ago, in a happy ignorance that I had been anticipated by no less a person than Heraclitus. "There is no Being but Becoming," that was what appeared to my unscholarly mind to be almost triumphantly new. I have since then informed myself more fully about Heraclitus, there are moments now when I more than half suspect that all the thinking I shall ever do will simply serve to illuminate my understanding of him, but at any rate that apothegm of his does exactly convey the intellectual attitude into which I fall. I am curiously not interested in things, and curiously interested in the consequences of things, I wouldn't for the world go to see the United States for what they are—if I had sound reason for supposing that the entire western hemisphere was to be destroyed next Christmas, I should not, I think, be among the multitude that would rush for one last look at that great spectacle,—from which it follows naturally that I don't propose to see Niagara. I should much more probably turn an inquiring visage eastward, with the west so certainly provided for. I have come to be, I am afraid, even a little insensitive to fine immediate things through this anticipatory habit.

This habit of mind confronts and perplexes my sense of things that simply are, with my brooding preoccupation with how they will shape presently, what they will lead to, what seed they will sow and how they will wear. At times, I can assure the reader, this quality approaches otherworldliness, in its constant reference to an all-important hereafter. There are times indeed when it makes life seem so transparent and flimsy, seem so dissolving, so passing on to an equally transitory series of consequences, that the enhanced sense of instability becomes restlessness and distress; but on the other hand nothing that exists, nothing whatever, remains altogether vulgar or dull and dead or hopeless in its light. But the interest is shifted. The pomp and splendor of established order, the braying triumphs, ceremonies, consummations, one sees these glittering shows for what they are—through their threadbare grandeur shine the little significant things that will make the future....

And now that I am associating myself with great names, let me discover that I find this characteristic turn of mind of mine, not only in Heraclitus, the most fragmentary of philosophers, but for one fine passage at any rate, in Mr. Henry James, the least fragmentary of novelists. In his recent impressions of America I find him apostrophizing the great mansions of Fifth Avenue, in words quite after my heart:—

"It's all very well," he writes, "for you to look as if, since you've had no past, you're going in, as the next best thing, for a magnificent compensatory future. What are you going to make your future of, for all your airs, we want to know? What elements of a future, as futures have gone in the great world, are at all assured to you?"

I had already when I read that, figured myself as addressing if not these particular last triumphs of the fine Transatlantic art of architecture, then at least America in general in some such words. It is not impleasant to be anticipated by the chief Master of one's craft, it is indeed, when one reflects upon his peculiar intimacy with this problem, enormously reassuring, and so I have very gladly annexed his phrasing and put it here to honor and adorn and in a manner to explain my own enterprise. I have already studied some of these fine buildings through the mediation of an illustrated magazine—they appear solid, they appear wonderful and well done to the highest pitch—and before many days now I shall, I hope, reconstruct that particular moment, stand—the latest admirer from England—regarding these portentous magnificences, from the same sidewalk—will they call it?—as my illustrious predecessor, and with his question ringing in my mind all the louder for their proximity, and the universally acknowledged invigoration of the American atmosphere. "What are you going to make your future of, for all your airs?"

And then I suppose I shall return to crane my neck at the Flat-iron Building or the Times skyscraper, and ask all that too, an identical question.

Certain phases in the development of these prophetic exercises one may perhaps be permitted to trace. To begin with, I remember that to me in my boyhood speculation about the Future was a monstrous joke. Like most people of my generation I was launched into life with millennial assumptions. This present sort of thing, I believed, was going on for a time, interesting personally perhaps but as a whole inconsecutive, and then—it might be in my lifetime or a little after it—there would be trumpets and shoutings and celestial phenomena, a battle of Armageddon and the Judgment. As I saw it, it was to be a strictly protestant and individualistic judgment, each soul upon its personal merits. To talk about the Man of the Year Million was of course in the face of this great conviction, a whimsical play of fancy. The Year Million was just as impossible, just as gayly nonsensical as fairy-land.... I was a student of biology before I realized that this, my finite and conclusive End, at least in the material and chronological form, had somehow vanished from the scheme of things. In the place of it had come a blackness and a vagueness about the endless vista of years ahead, that was tremendous—that terrified. That is a phase in which lots of educated people remain to this day. "All this scheme of things, life, force, destiny which began not six thousand years, mark you, but an infinity ago, that has developed out of such strange weird shapes and incredible first intentions, out of gaseous nebulas, carboniferous swamps, saurian giantry and arboreal apes, is by the same tokens to continue, developing—into what?" That was the overwhelming riddle that came to me, with that realization of an End averted, that has come now to most of our world.

The phase that followed the first helpless stare of the mind was a wild effort to express one's sudden apprehension of unlimited possibility. One made fantastic exaggerations, fantastic inversions of all recognized things. Anything of this sort might come, anything of any sort. The books about the future that followed the first stimulus of the world's realization of the implications of Darwinian science, have all something of the monstrous experimental imaginings of children. I myself, in my microcos-mic way, duplicated the times. Almost the first thing I ever wrote—it survives in an altered form as one of a bookful of essays,—was of this type; "The Man of the Year Million," was presented as a sort of pantomime head and a shrivelled body, and years after that, The Time Machine, my first published book, ran in the same vein. At that point, at a brief astonished stare down the vistas of time-to-come, at something between wonder and amazed, incredulous, defeated laughter, most people, I think, stop. But those who are doomed to the prophetic habit of mind go on.

The next phase, the third phase, is to shorten the range of the outlook, to attempt something a little more proximate than the final destiny of man. One becomes more systematic, one sets to work to trace the great changes of the last century or so, and one produces these in a straight line and according to the rule of three. If the maximum velocity of land travel in 1800 was twelve miles an hour and in 1900 (let us say) sixty miles an hour, then one concludes that in 2000 A.D. it will be three hundred miles an hour. If the population of America in 1800—but I refrain from this second instance. In that fashion one got out a sort of gigantesque caricature of the existing world, everything swollen to vast proportions and massive beyond measure. In my case that phase produced a book. When the Sleeper Wakes, in which, I am told, by competent New-Yorkers, that I, starting with London, an unbiassed mind, this rule-of-three method and my otherwise unaided imagination, produced something more like Chicago than any other place wherein righteous men are likely to be found. That I shall verify in due course, but my present point is merely that to write such a book is to discover how thoroughly wrong this all too obvious method of enlarging the present is.

One goes on therefore—if one is to succumb altogether to the prophetic habit—to a really "scientific" attack upon the future. The "scientific" phase is not final, but it is far more abundantly fruitful than its predecessors. One attempts a rude wide analysis of contemporary history, one seeks to clear and detach operating causes and to work them out, and so, combining this necessary set of consequences with that, to achieve a synthetic forecast in terms just as broad and general and vague as the causes considered are few. I made, it happens, an experiment in this scientific sort of prophecy in a book called Anticipations, and I gave an altogether excessive exposition and defence of it, I went altogether too far in this direction, in a lecture to the Royal Institution, "The Discovery of the Future," that survives in odd corners as a pamphlet, and is to be found, like a scrap of old newspaper in the roof gutter of a museum, in Nature (vol. LXV., p. 326) and in the Smithsonian Report (for 1902). Within certain limits, however, I still believe this scientific method is sound. It gives sound results in many cases, results at any rate as sound as those one gets from the "laws" of political economy; one can claim it really does effect a sort of prophecy on the material side of life.

For example, it was quite obvious about 1899 that invention and enterprise were very busy with the means of locomotion, and one could deduce from that certain practically inevitable consequences in the distribution of urban populations. With easier, quicker means of getting about there were endless reasons, hygienic, social, economic, why people should move from the town centres towards their peripheries, and very few why they should not. The towns one inferred therefore, would get slacker, more diffused, the country- side more urban. From that, from the spatial widening of personal interests that ensued, one could infer certain changes in the spirits of local politics, and so one went on to a number of fairly valid adumbrations. Then again starting from the practical supersession in the long run of all unskilled labor by machinery one can work out with a pretty fair certainty many coming social developments, and the broad trend of one group of influences at least from the moral attitude of the mass of common people. In industry, in domestic life again, one foresees a steady developmer^t of complex appliances, demanding, and indeed in an epoch of frequently changing methods forcing, a flexible understanding, versatility of effort, a universal rising standard of education. So too a study of military methods and apparatus convinces one of the necessary transfer of power in the coming century from the ignorant and enthusiastic masses who made the revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and won Napoleon his wars, to any more deliberate, more intelligent and more disciplined class that may possess an organized purpose. But where will one find that class? There comes a question that goes outside science, that takes one at once into a field beyond the range of the "scientific" method altogether.

So long as one adopts the assumptions of the old political economist and assumes men without idiosyncrasy, without prejudices, without, as people say, wills of their own, so long as one imagines a perfectly acquiescent humanity that will always in the long run under pressure liquefy and stream along the line of least resistance to its own material advantage, the business of prophecy is easy. But from the first I felt distrust for that facility in prophesying, I perceived that always there lurked something, an incalculable opposition to these mechanically conceived forces, in law, in usage and prejudice, in the poietic power of exceptional individual men. I discovered for myself over again, the inseparable nature of the two functions of the prophet. In my Anticipations, for example, I had intended simply to work out and foretell, and before I had finished I was in a fine full blast of exhortation....

That by an easy transition brought me to the last stage in the life history of the prophetic mind, ,as it is at present known to me. One comes out on the other side of the "scientific" method, into the large temperance, the valiant inconclusiveness, the released creativeness of philosophy. Much may be foretold as certain, much more as possible, but the last decisions and the greatest decisions, lie in the hearts and wills of unique incalculable men. With them we have to deal as our ultimate reality in all these matters, and our methods have to be not "scientific" at all for all the greater issues, the humanly important issues, but critical, literary, even if you will—artistic. Here insight is of more account than induction and the perception of fine tones than the counting of heads. Science deals with necessity and necessity is here but the firm ground on which our freedom goes. One passes from affairs of predestination to affairs of free will. This discovery spread at once beyond the field of prophesying. The end, the aim, the test of science, as a model man understands the word, is foretelling by means of "laws," and my error in attempting a complete "scientific" forecast of human affairs arose in too careless an assent to the ideas about me, and from accepting uncritically such claims as that history should be "scientific," and that economics and sociology (for example) are "sciences." Directly one gauges the fuller implications of that uniqueness of individuals Darwin's work has so permanently illuminated, one passes beyond that. The ripened prophet realizes Schopenhauer—as indeed I find Professor Munsterberg saying. "The deepest sense of human affairs is reached," he writes, "when we consider them not as appearances but as decisions." There one has the same thing coming to meet one from the psychological side....

But my present business isn't to go into this shadowy, metaphysical foundation world on which our thinking rests, but to the brightly lit overworld of America. This philosophical excursion is set here just to prepare the reader quite frankly for speculations and to disabuse his mind of the idea that in writing of the Future in America I'm going to write of houses a hundred stories high and flying-machines in warfare and things like that, I am not going to America to work a pretentious horoscope, to discover a Destiny, but to find out what I can of what must needs make that Destiny,—a great nation's Will.

The material factors in a nation's future are subordinate factors, they present advantages, such as the easy access of the English to coal and the sea, or disadvantages, such as the ice-bound seaboard of the Russians, but these are the circumstances and not necessarily the rulers of its fate. The essential factor in the destiny of a nation, as of a man and of mankind, lies in the form of its will and in the quality and quantity of its will. The drama of a nation's future, as of a man's, lies in this conflict of its will with what would else be "scientifically" predictable, materially inevitable. If the man, if the nation was an automaton fitted with good average motives, so and so,' one could say exactly, would be done. It's just where the thing isn't automatic that our present interest comes in.

I might perhaps reverse the order of the three aspects of will I have named, for manifestly where the quantity of will is small, it matters nothing what the form or quality. The man or the people that wills feebly is the sport of every circumstance, and there if anywhere the scientific method holds truest or even altogether true. Do geographical positions or mineral resources make for riches? Then such a people will grow insecurely and disastrously rich. Is an abundant prolific life at a low level indicated? They will pullulate and suffer. If circumstances make for a choice between comfort and reproduction, your feeble people will dwindle and pass; if war, if conquest tempt them then they will turn from all preoccupations and follow the drums. Little things provoke their unstable equilibrium, to hostility, to forgiveness....

And be it noted that the quantity of will in a nation is not necessarily determined by adding up the wills of all its people. I am told, and I am disposed to believe it, that the Americans of the United States are a people of great individual force of will, the clear strong faces of many young Americans, something almost Roman in the faces of their statesmen and politicians, a distinctive quality I detect in such Americans as I have met, a quality of sharply cut determination even though it be only about details and secondary things, that one must rouse one's self to meet, inclines me to give a provisional credit to that, but how far does all this possible will-force aggregate to a great national purpose?—what algebraically does it add up to when this and that have cancelled each other? That may be a different thing altogether.

And next to this net quantity of will a nation or people may possess, come the questions of its quality, its flexibility, its consciousness and intellectuality. A nation may be full of will and yet inflexibly and disastrously stupid in the expression of that will. There was probably more will-power, more haughty and determined self-assertion in the young bull that charged the railway engine than in several regiments of men, but it was after all a low quality of will with no method but a violent and injudicious directness, and in the end it was suicidal and futile. There again is the substance for ramifying Enquiries.' How subtle, how collected and patient, how far capable of a long plan, is this American nation? Suppose it has a will so powerful and with such resources that whatever simple end may be attained by rushing upon it is America's for the asking, there still remains the far more important question of the ends that are not obvious, that are intricate and complex and not to be won by booms and cataclysms of effort.

An Englishman comes to think that most of the permanent and precious things for which a nation's effort goes are like that, and here too I have an open mind and unsatisfied curiosities.

And lastly there is the form of the nation's purpose. I have been reading what I can find about that in books for some time, and now I want to cross over the Atlantic, more particularly for that, to question more or less openly certain Americans, not only men and women, but the mute expressive presences of house and appliance, of statue, flag and public building, and the large collective visages of crowds, what it is all up to, what it thinks it is all after, how far it means to escape or improve upon its purely material destinies? I want over there to find whatever consciousness or vague consciousness of a common purpose there may be, what is their Vision, their American Utopia, how much will there is shaping to attain it, how much capacity goes with the will—what, in short, there is in America, over and above the mere mechanical consequences of scattering multitudes of energetic Europeans athwart a vast healthy, productive and practically empty continent in the temperate zone. There you have the terms of reference of an enquiry, that is I admit (as Mr. Morgan Richards the eminent advertisement agent would say), "mammoth in character."

The American reader may very reasonably inquire at this point why an Englishman does not begin with the future of his own country. The answer is that this particular one has done so, and that in many ways he has found his intimacy and proximity a disadvantage. One knows too much of the things that seem to matter and that ultimately don't, one is full of misleading individual instances intensely seen, one can't see the wood for the trees. One comes to America at last, not only with the idea of seeing America, but with something more than an incidental hope of getting one's own England there in the distance and as a whole, for the first time in one's life. And the problem of America, from this side anyhow, has an air of being simpler. For all the Philippine adventure her future still seems to lie on the whole compactly in one continent, and not as ours is, dispersed round and about the habitable globe, strangely entangled with India, with Japan, with Africa and with the great antagonism the Germans force upon us at our doors. Moreover one cannot look ten years ahead in England, without glancing across the Atlantic. "There they are," we say to one another, "those Americans! They speak our language, read our books, give us books, share our mind. What we think still goes into their heads in a measure, and their thoughts run through our brains. What will they be up to?"

Our future is extraordinarily bound up in America's and in a sense dependent upon it. It is not that we dream very much of political reunions of Anglo Saxondom and the like. So long as we British retain our wide and accidental sprawl of empire about the earth we cannot expect or desire the Americans to share our stresses and entanglements. Our Empire has its own adventurous and perilous outlook. But our civilization is a different thing from our Empire, a thing that reaches out further into the future, that will be going on changed beyond recognition. Because of our common language, of our common traditions, Americans are a part of our community, are becoming indeed the larger part of our community of thought and feeling and outlook—in a sense far more intimate than any link we have with Hindoo or Copt or Cingalese. A common Englishman has an almost pathetic pride and sense of proprietorship in the States; he is fatally ready to fall in with the idea that two nations that share their past, that still, a little restively, share one language, may even contrive to share an infinitely more interesting future. Even if he does not chance to be an American now, his grandson may be. America is his inheritance, his reserved accumulating investment. In that sense indeed America belongs to the whole western world; all Europe owns her promise, but to the Englishman the sense of participation is intense. "We did it," he will tell of the most American of achievements, of the settlement of the middle west for example, and this is so far justifiable that numberless men, myself included, are Englishmen, Australian, New-Zealanders, Canadians, instead of being Americans, by the merest accidents of life. My father still possesses the stout oak box he had had made to emigrate withal, everything was arranged that would have got me and my brothers born across the ocean, and only the coincidence of a business opportunity and an illness of my mother's, arrested that. It was so near a thing as that with me, which prevents my blood from boiling with patriotic indignation instead of patriotic solicitude at the frequent sight of red-coats as I see them from my study window going to and fro to ShornclifTe camp.

Well I learn from Professor Munsterberg how vain my sense of proprietorship is, but still this much of it obstinately remains, that I will at any rate look at the American future.

By the accidents that delayed that box it comes about that if I want to see what America is up to, I have among other things to buy a Baedeker and a steamer ticket and fill up the inquiring blanks in this remarkable document before me, the long string of questions that begins:—

"Are you a Polygamist?"

"Are you an Anarchist?"

Here I gather is one little indication of the great will I am going to study. It would seem that the United States of America regard Anarchy and Polygamy with aversion, regard indeed Anarchists and Polygamists as creatures unfit to mingle with the already very various eighty million of citizens who constitute their sovereign powers, and on the other hand hold these creatures so inflexibly honorable as certainly to tell these damning truths about themselves in this matter....

It's a little odd. One has a second or so of doubt about the quality of that particular manifestation of will.

(On the "Carmania" going America-ward)

When one talks to an American of his national purpose he seems a little at a loss; if one speaks of his national destiny, he responds with alacrity. I make this generalization on the usual narrow foundations, but so the impression comes to me.

Until this present generation, indeed until within a couple of decades, it is not very evident that Americans did envisage any national purpose at all, except in so far as there was a certain solicitude not to be cheated out of an assured destiny. A sort of optimistic fatalism possessed them. They had, and mostly it seems they still have, a tremendous sense of sustained and assured growth, and it is not altogether untrue that one is told—I have been told—such things as that "America is a great country, sir," that its future is gigantic and that it is already (and going to be more and more so) the greatest country on earth.

I am not the sort of Englishman who questions that. I do so regard that much as obvious and true that it seems to me even a Httle undignified, as well as a little overbearing, for Americans to insist upon it so; I try to go on as soon as possible to the question just how my interlocutor shapes that gigantic future and what that world predominance is finally to do for us in England and all about the world. So far, I must insist, I haven't found anything like an idea. I have looked for it in books, in papers, in speeches and now I am going to look for it in America. At the most I have found vague imaginings that correspond to that first or monstrous stage in the scheme of prophetic development I sketched in my opening.

There is often no more than a volley of rhetorical blank-cartridge. So empty is it of all but sound that I have usually been constrained by civility from going on to a third enquiry;—

"And what are you, sir, doing in particular, to assist and enrich this magnificent and quite indefinable Destiny of which you so evidently feel yourself a part?"...

That seems to be really no unjust rendering of the conscious element of the American outlook as one finds it, for example, in these nice-looking and pleasant-mannered fellow-passengers upon the Carmania upon whom I fasten with leading questions and experimental remarks. One exception I discover—a pleasant New York clubman who has doubts of this and that. The discipHne and sense of purpose in Germany has laid hold upon him. He seems to be, in contrast with his fellow-countrymen, almost pessimistically aware that the American ship of state is after all a mortal ship and liable to leakages. There are certain problems and dangers he seems to think that may delay, perhaps even prevent, an undamaged arrival in that predestined port, that port too resplendent for the eye to rest upon; a Chinese peril, he thinks has not been finally dealt with, "race suicide" is not arrested for all that it is scolded in a most valiant and virile manner, and there are adverse possibilities in the immigrant, in the black, the socialist, against which he sees no guarantee. He sees huge danger in the development and organization of the new finance and no clear promise of a remedy. He finds the closest parallel between the American Republic and Rome before the coming of Imperialism. But these other Americans have no share in his pessimisms. They may confess to as much as he does in the way of dangers, admit there are occasions for calking, a need of stopping quite a number of possibilities if the American Idea is to make its triumphant entry at last into that port of blinding accomplishment, but, apart from a few necessary preventive proposals, I do not perceive any extensive sense of anything whatever to be done, anything to be shaped and thought out and made in the sense of a national determination to a designed and specified end.

There are, one must admit, tremendous justifications for the belief in a sort of automatic ascent of American things to unprecedented magnificences, an ascent so automatic that indeed one needn't bother in the slightest to keep the whole thing going. For example, consider this, last year's last-word in ocean travel in which I am crossing, the Carmania with its unparalleled steadfastness, its racing, tireless great turbines, its vast population of 3244 souls! It has on the whole a tremendous effect of having come by fate and its own forces. One forgets that any one planned it, much of it indeed has so much the quality of moving, as the planets move, in the very nature of things. You go aft and see the wake tailing away across the blue ridges, you go forward and see the cleft water, lift protestingly, roll back in an indignant crest, own itself beaten and go pouring by in great foaming waves on either hand, you see nothing, you hear nothing of the toiling engines, the reeking stokers, the effort and the stress below; you beat west and west, as the sun does and it might seem with nearly the same independence of any living man's help or opposition. Equally so does it seem this great, gleaming, confident thing of power and metal came inevitably out of the past and will lead on to still more shining, still swifter and securer monsters in the future.

One sees in the perspective of history, first the Httle cockle-shells of Columbus, the comings and goings of the precarious Tudor adventurers, the slow uncertain shipping of colonial days. Says Sir George Trevelyan in the opening of his American Revolution, that then—it is still not a century and a half ago!—

"...a man bound for New York, as he sent his luggage on board at Bristol, would willingly have compounded for a voyage lasting as many weeks as it now lasts days.... Adams, during the height of the war, hurrying to France in the finest frigate Congress could place at his disposal... could make not better speed than five and forty days between Boston and Bordeaux. Lord Carlisle... was six weeks between port and port; tossed by gales which inflicted on his brother Commissioners agonies such as he forbore to make a matter of joke even to George Selwyn.... How humbler individuals fared.... They would be kept waiting weeks on the wrong side of the water for a full complement of passengers and weeks more for a fair wind, and then beating across in a badly found tub with a cargo of millstones and old iron rolling about below, they thought themselves lucky if they came into harbor a month after their private store of provisions had run out and carrying a budget of news as stale as the ship's provisions."

Even in the time of Dickens things were by no measure more than half-way better. I have with me to enhance my comfort by this aided retrospect, his American Notes. His crossing lasted eighteen days and his boat was that "far- famed American steamer," the Britannia (the first of the long succession of Cunarders, of which this Carmania is the latest); his return took fifty days, and was a jovial home-coming under sail. It's the journey out gives us our contrast. He had the "state-room" of the period and very unhappy he was in it, as he testifies in a characteristically mounting passage.

"That this state-room had been specially engaged for 'Charles Dickens, Esquire, and Lady,' was rendered sufficiently clear even to my scared intellect by a very small manuscript, announcing the fact, which was pinned on a very fiat quilt, covering a very thin mattress, spread like a surgical plaster on a most inaccessible shelf. But that this was the state- room, concerning which Charles Dickens, Esquire, and Lady, had held daily and nightly conferences for at least four months preceding; that this could by any possibility be that small snug chamber of the imagination, which Charles Dickens, Esquire, with the spirit of prophecy strong upon him, had always foretold would contain at least one little sofa, and which his Lady, with a modest and yet most magnificent sense of its limited dimensions, had from the first opined would not hold more than two enormous portmanteaus in some odd corner out of sight (portmanteaus which could now no more be got in at the door, not to say stowed away, than a giraffe could be persuaded or forced into a flower-pot): that this utterly impracticable, thoroughly preposterous box, had the remotest reference to, or connection with, those chaste and pretty bowers, sketched in a masterly hand, in the highly varnished, lithographic plan, hanging up in the agent's counting-house in the City of London: that this room of state, in short, could be anything but a pleasant fiction and cheerful jest of the Captain's, invented and put in practice for the better relish and enjoyment of the real state-room presently to be disclosed: these were truths which I really could not bring my mind at all to bear upon or comprehend."

So he precludes his two weeks and a half of vile weather in this paddle boat of the middle ages (she carried a "formidable" multitude of no less than eighty-six saloon passengers) and goes on to describe such experiences as this;

"About midnight we shipped a sea, which forced its way through the skylights, burst open the doors above, and came raging and roaring down into the ladies' cabin, to the unspeakable consternation of my wife and a little Scotch lady.... They, and the handmaid before mentioned, being in such ecstacies of fear that I scarcely knew what to do with them, I naturally bethovight myself of some restorative or c9mfortable cordial; and nothing better occurring to me, at the moment, than hot brandy-and-water, I procured a tumblerful without delay. It being impossible to stand or sit without holding on, they were all heaped together in one corner of a long sofa—a fixture extending entirely across the cabin—where they clung to each other in momentary expectation of being drowned. When I approached this place with my specific, and was about to administer it with many consolatory expressions, to the nearest sufferer, what was my dismay to see them all roll slowly down to the other end! and when I staggered to that end, and held out the glass once more, how immensely baffled were my good intentions by the ship giving another lurch, and their rolling back again! I suppose I dodged them up and down this sofa, for at least a quarter of an hour, without reaching them once; and by the time I did catch them, the brandy-and-water was diminished, by constant spilling, to a teaspoonful. To complete the group, it is necessary to recognize in this disconcerted dodger, an individual very pale from sea-sickness, who had shaved his beard and brushed his hair last at Liverpool; and whose only articles of dress (linen not included) were a pair of dreadnought trousers; a blue jacket, formerly admired upon the Thames at Richmond; no stockings; and one slipper."

It gives one a momentary sense of superiority to the great master to read. that. One surveys one's immediate surroundings and compares them with his. One says almost patronizingly: "Poor old Dickens, you know, really did have too awful a time!" The waves are high now, and getting higher, dark-blue waves foam-crested; the waves haven't altered—except relatively—but one isn't even sea-sick. At the most there are squeamish moments for the weaker brethren. One looks down on these long white-crested undulations thirty feet or so of rise and fall, as we look down the side of a sky-scraper into a tumult in the street.

We displace thirty thousand tons of water instead of twelve hundred, we can carry 521 first and second class passengers, a crew of 463, and 2260 emigrants below....

We're a city rather than a ship, our funnels go up over the height of any reasonable church spire, and you need walk the main-deck from end to end and back only four times to do a mile. Any one who has been to London and seen Trafalgar Square will get our dimensions perfectly, when he realizes that we should only squeeze into that finest site in Europe, diagonally, dwarfing the National Gallery, St. Martin's Church, hotels and every other building there out of existence, our funnels towering five feet higher than Nelson on his column. As one looks down on it all from the boat-deck one has a social microcosm, we could set up as a small modern country and renew civilization even if the rest of the world was destroyed. We've the plutocracy up here, there is a middle class on the second-class deck and forward a proletariat—the proles much in evidence—complete. It's possible to go slumming aboard.... We have our daily paper, too, printed aboard, and all the latest news by marconigram....

Never was anything of this sort before, never. Caligula's shipping it is true (unless it was Con-stantine's) did, as Mr. Cecil Torr testifies, hold a world record until the nineteenth century and he quotes Pliny for thirteen hundred tons—outdoing the Britannia—and Moschion for cabins and baths and covered vine-shaded walks and plants in pots. But from 1840 onward, we have broken away into a new scale for life. This Carmania isn't the largest ship nor the finest, nor is it to be the last. Greater ships are to follow and greater. The scale of size, the scale of power, the speed and dimensions of things about us alter remorselessly—to some limit we cannot at present descry.

It is the development of such things as this, it is this dramatically abbreviated perspective from those pre-Reformation caravels to the larger, larger, larger of the present vessels, one must blame for one's illusions.

One is led unawares to believe that this something called Progress is a natural and necessary and secular process, going on without the definite will of man, carrying us on quite independently of us; one is led unawares to forget that it is after all from the historical point of view only a sudden universal jolting forward in history, an affair of two centuries at most, a process for the continuance of which we have no sort of guarantee. Most western Europeans have this delusion of automatic progress in things badly enough, but with Americans it seems to be almost fundamental. It is their theory of the Cosmos and they no more think of inquiring into the sustaining causes of the progressive movement than they would into the character of the stokers hidden away from us in this great thing somewhere—the officers alone know where.

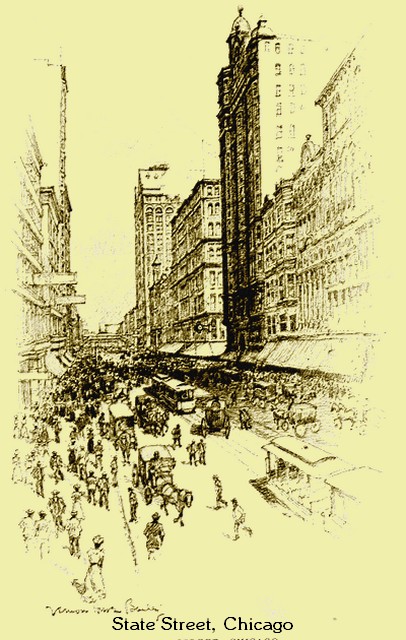

I am happy to find this blind confidence very well expressed for example in an illustrated magazine article by Mr, Edgar Saltus, "New York from the Flat-iron," that a friend has put in my hand to prepare me for the wonders to come. Mr. Saltus writes with an eloquent joy of his vision of Broadway below, Broadway that is now "barring trade-routes, the largest commercial stretch on this planet." So late as Dickens's visit it was scavenged by roving untended herds of gaunt, brown, black-blotched pigs. He writes of lower Fifth Avenue and upper Fifth Avenue, of Madison Square and its tower, of sky-scrapers and sky-scrapers and sky-scrapers round and about the horizon. (I am to have a tremendous view of them to-morrow as we steam up from the Narrows.) And thus Mr. Saltus proceeds,—•

"As you lean and gaze from the toppest floors on houses below, which from those floors seem huts, it may occur to you that precisely as these huts were once regarded as supreme achievements, so, one of these days, from other and higher floors, the Flat-iron may seem a hut itself. Evolution has not halted. Undiscemibly but indefatiga-bly, always it is progressing. Its final term is not existing buildings, nor in existing man. If humanity sprang from gorillas, from humanity gods shall proceed."

The rule of three in excelsis!

"The story of Olympus is merely a tale of what might have been. That which might have been may yet come to pass. Even now could the old divinities, hushed for-evermore, awake, they would be perplexed enough to see how mortals have exceeded them.... In Fifth Avenue inns they could get fairer fare than ambrosia, and behold women beside whom Venus herself would look provincial and Juno a frump. The spectacle of electricity tamed and domesticated would surprise them not a little, the elevated quite as much, the Flat-iron still more. At sight of the latter they would recall the Titans with whom once they warred, and sink to their sun-red seas outfaced.

"In this same measure we have succeeded in exceeding them, so will posterity surpass what we have done. Evolution may be slow, it achieved an unrecognized advance when it devised buildings such as this. It is demonstrable that small rooms breed small thoughts. It will be demonstrable that, as buildings ascend, so do ideas. It is mental progress that sky-scrapers engender. From these parturitions gods may really proceed—beings, that is, who, could we remain long enough to see them, would regard us as we regard the apes...."

Mr. Saltus writes, I think, with a very typical American accent. Most Americans think Hke that and all of them I fancy feel like it. Just in that spirit a later-empire Roman might have written apropos the gigantic new basilica of Constantine the Great (who was also, one recalls, a record-breaker in ship-building) and have compared it with the straitened proportions of Cccsar's Forum and the meagre relics of republican Rome. So too {absit omen) he might have swelled into prophecy and sounded the true modern note.

One hears that modern note everywhere nowadays where print spreads, but from America with fewer undertones than anywhere. Even I find it, ringing clear, as a thing beyond disputing, as a thing as self-evident as sunrise again and again in the expressed thought of Mr. Henry James.

But you know this progress isn't guaranteed. We have all indeed been carried away completely by the up-rush of it all. To me now this Carmania seems to typify the whole thing. What matter it if there are moments when one reflects on the mysterious smallness and it would seem the ungrowing quality of the human content of it all? We are, after all, astonishingly like flies on a machine that has got loose. No matter. Those people on the main-deck are the oddest crowd, strange Oriental-looking figures with Astrakhan caps, hook-noses, shifty eyes, and indisputably dirty habits, bold-eyed, red-capped, expectorating women, quaint and amazingly dirty children; Tartars there are too, and Cossacks, queer wraps, queer head-dresses, a sort of greasy picturesqueness over them all. They use the handkerchief solely as a head covering. Their deck is disgusting with fragments of food, with eggshells they haven't had the decency to throw overboard. Collectively they have—an atmosphere. They're going where we're going, wherever that is. What matters it? What matters it, too, if these people about me in the artistic apartment talk nothing but trivialities derived from the Daily Bulletin, think nothing but trivialities, are, except in the capacity of paying passengers, the most ineffectual gathering of human beings conceivable? What matters it that there is no connection, no understanding whatever between them and that large and ominous crowd a plank or so and a yard or so under our feet? Or between themselves for the matter of that? What matters it if nobody seems to be struck by the fact that we are all, the three thousand two hundred of us so extraordinarily got together into this tremendous machine, and that not only does nobody inquire what it is has got us together in this astonishing fashion and why, but that nobody seems to feel that we are together in any sort of way at all? One looks up at the smoke-pouring funnels and back at the foaming wake. It will be all right. Aren't we driving ahead westward at a pace of four hundred and fifty miles a day?

And twenty or thirty thousand other souls, mixed and stratified, on great steamers ahead of us, or behind, are driving westward too. That there's no collective mind apparent in it at all, worth speaking about is so much the better. That only shows its Destiny, its Progress as inevitable as gravitation. I could almost believe it, as I sit quietly writing here by a softly shaded light in this elegantly appointed drawing-room, as steady as though I was in my native habitat on dry land instead of hurrying almost fearfully, at twenty knots an hour, over a tumbling empty desert of blue waves under a windy sky. But, only a little while ago, I was out forward alone, looking at that. Everything was still except for the remote throbbing of the engines and the nearly efTaced sound of a man, singing in a strange tongue, that came from the third-class gangway far below. The sky was clear, save for a few black streamers of clouds, Orion hung very light and large above the waters, and a great new moon, still visibly holding its dead predecessor in its crescent, sank near him. Between the sparse great stars were deep blue spaces, unfathomed distances.

Out there I had been reminded of space and time. Out there the ship was just a hastening ephemeral fire-fly that had chanced to happen across the eternal tumult of the winds and sea.

(In a room on the ninth floor in the sky-scraper hotel New York)

My first impressions of New York are impressions enormously to enhance the effect of this Progress, this material progress, that is to say, as something inevitable and inhuman, as a blindly furious energy of growth that must go on. Against the broad and level gray contours of Liverpool one found the ocean liner portentously tall, but here one steams into the middle of a town that dwarfs the ocean liner. The sky-scrapers that are the New-Yorker's perpetual boast and pride rise up to greet one as one comes through the Narrows into the Upper Bay, stand out, in a clustering group of tall irregular crenellations, the strangest crown that ever a city wore. They have an effect of immense incompleteness; each one seems to await some needed terminal,—to be, by virtue of its woolly jets of steam, still as it were in process of eruption. One thinks of St. Peter's great blue dome, finished and done as one saw it from a vine-shaded wine-booth above the Milvian Bridge, one thinks of the sudden ascendency of St. Paul's dark grace, as it soars out over any one who comes up by the Thames towards it. These are efforts that have accomplished their ends, and even Paris illuminated under the tall stem of the Eiffel Tower looked completed and defined. But New York's achievement is a threatening promise, growth going on under a pressure that increases, and amidst a hungry uproar of effort.

One gets a measure of the quality of this force of mechanical, of inhuman, growth as one marks the great statue of Liberty on our larboard, which is meant to dominate and fails absolutely to dominate the scene. It gets to three hundred feet about, by standing on a pedestal of a hundred and fifty; and the uplifted torch, seen against the sky, suggests an arm straining upward, straining in hopeless competition with the fierce commercial altitudes ahead. Poor liberating Lady of the American ideal! One passes her and forgets.

Happy returning natives greet the great pillars of business by name, the St. Paul Building, the World, the Manhattan tower; the English new-comer notes the clear emphasis of the detail, the freedom from smoke and atmospheric mystery that New York gains from burning anthracite, the jetting white steam clouds that emphasize that freedom. Across the broad harbor plies an unfamiliar traffic of grotesque broad ferry-boats, black with people, glutted to the lips with vans and carts, each hooting and yelping its own distinctive note, and there is a wild hurrying up and down and to and fro of piping and bellowing tugs and barges; and a great floating platform, bearing a railway train, gets athwart our course as we ascend and evokes megatherial bel-lowings. Everything is moving at a great speed, and whistling and howling, it seems, and presently far ahead we make out our own pier, black with expectant people, and set up our own distinctive whoop, and with the help of half a dozen furiously noisy tugs are finally lugged and butted into dock. The tugs converse by yells and whistles, it is an affair of short-tempered mechanical monsters, amidst which one watches for one's opportunity to get ashore.

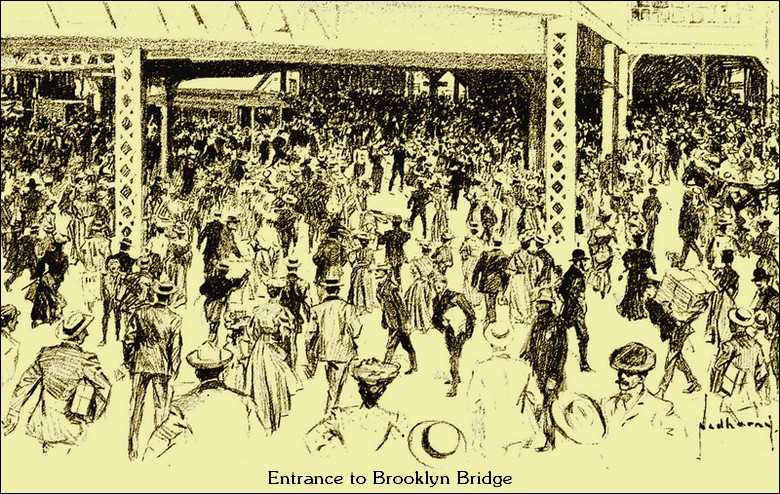

Noise and human hurry and a vastness of means and collective result, rather than any vastness of achievement, is the pervading quality of New York. The great thing is the mechanical thing, the unintentional thing which is speeding up all these people, driving them in headlong hurry this way and that, exhorting them by the voice of every car conductor to "step lively," aggregating them into shoving and elbowing masses, making them stand clinging to straps, jerking them up elevator shafts and pouring them on to the ferry- boats. But this accidental great thing is at times a very great thing. Much more impressive than the sky-scrapers to my mind is the large Brooklyn suspension-bridge.

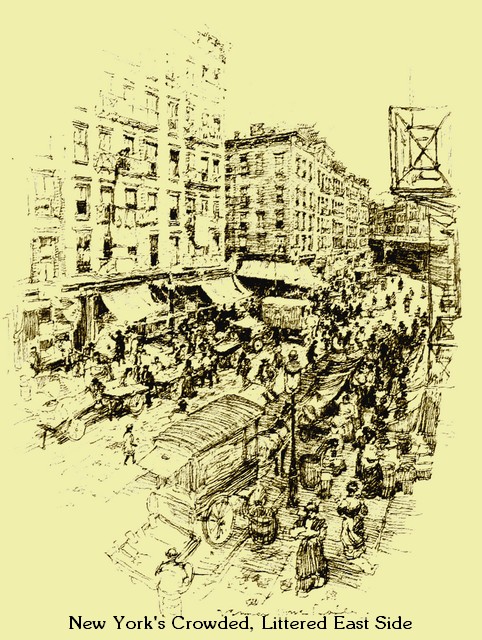

I have never troubled to ask who built that; its greatness is not in its design, but in the quality of necessity one perceives in its inanimate immensity. It tells, as one goes under it up the East River, but it is far more impressive to the stranger to come upon it by glimpses, wandering down to it through the ill-paved van-infested streets from Chatham Square. One sees parts of Cyclopean stone arches, one gets suggestive glimpses through the jungle growth of business now of the back, now of the flanks, of the monster; then, as one comes out on the river, one discovers far up in one's sky the long sweep of the bridge itself, foreshortened and with a maximum of perspective effect; the streams of pedestrians and the long line of carts and vans, quaintly microscopic against the blue, the creeping progress of the little cars on the lower edge of the long chain of netting; all these things dwindling indistinguishably before Brooklyn is reached. Thence, if it is late afternoon, one may walk back to City Hall Park and encounter and experience the convergent stream of clerks and workers making for the bridge, mark it grow denser and denser, until at last they come near choking even the broad approaches of the giant duct, until the congested multitudes jostle and fight for a way. They arrive marching afoot by every street in endless procession; crammed trolley-cars disgorge them; the Subway pours them out.... The individuals count for nothing, they are clerks and stenographers, shopmen, shop-girls, workers of innumerable types, black-coated men, hat-and-blouse girls, shabby and cheaply clad persons, such as one sees in London, in Berlin, anywhere. Perhaps they hurry more, perhaps they seem more eager. But the distinctive effect is the mass, the black torrent, rippled with unmeaning faces, the great, the unprecedented mul-titudinousness of the thing, the inhuman force of it all.

I made no efforts to present any of my letters, or to find any one to talk to on my first day in New York. I landed, got a casual lunch, and w^andered alone until New York's peculiar effect of inhuman noise and pressure and growth became overwhelming, touched me with a sense of solitude, and drove me into the hospitable companionship of the Century Club. Oh, no doubt of New York's immensity! The sense of soulless gigantic forces, that took no heed of men, became stronger and stronger all that day. The pavements were often almost incredibly out of repair, when I became footweary the streetcars would not wait for me, and I had to learn their stopping-points as best I might. I wandered, just at the right pitch of fatigue to get the full force of it into the eastward region between Third and Fourth Avenue, came upon the Elevated railway at its worst, the darkened streets of disordered paving below, trolley-car-congested, the ugly clumsy lattice, sonorously busy overhead, a clatter of vans and draught-horses, and great crowds of cheap, base-looking people hurrying uncivilly by....

I CORRECTED that first crowded impression of New York with a clearer, brighter vision of expansiveness when next day I began to realize the social quality of New York's central backbone, between Fourth Avenue and Sixth. The effect remained still that of an immeasurably powerful forward movement of rapid eager advance, a process of enlargement and increment in every material sense, but it may be because I was no longer fatigued, was now a little initiated, the human being seemed less of a fly upon the wheels. I visited immense and magnificent clubs—London has no such splendors as the Union, the University, the new hall of the Harvard—I witnessed the great torrent of spending and glittering prosperity in carriage and motor-car pour along Fifth Avenue. I became aware of effects that were not only vast and opulent but fine. It grew upon me that the Twentieth Century, which found New York brown-stone of the color of desiccated chocolate, meant to leave it a city of white and colored marble. I found myself agape, admiring a sky-scraper—the prow of the Flat-iron Building, to be particular, ploughing up through the traffic of Broadway and Fifth Avenue in the afternoon light. The New York sundown and twilight seemed to me quite glorious things. Down the western streets one gets the sky hung in long cloud-barred strips, like Japanese paintings, celestial tranquil yellows and greens and pink luminosity toning down to the reeking blue-brown edge of the distant New Jersey atmosphere, and the clear, black, hard activity of crowd and trolley-car and Elevated railroad. Against this deepening color came the innumerable little lights of the house cliffs and the street tier above tier. New York is lavish of light, it is lavish of everything, it is full of the sense of spending from an inexhaustible supply. For a time one is drawn irresistibly into the universal belief in that inexhaustible supply.

At a bright table in Delmonico's to-day at lunch-time, my host told me the first news of the destruction of the great part of San Francisco by earthquake and fire. It had just come through to him, it wasn't yet being shouted by the newsboys. He told me compactly of dislocated water-mains, of the ill-luck of the unusual eastward wind that was blowing the fire up-town, of a thousand reported dead, of the manifest doom of the greater portion of the city, and presently the shouting voices in the street outside arose to chorus him. He was a newspaper man and a little preoccupied because his San Francisco offices were burning, and that no further news was arriving after these first intimations. Naturally the catastrophe was our topic. But this disaster did not affect him, it does not seem to have affected any one with a sense of final destruction, with any foreboding of irreparable disaster. Every one is talking of it this afternoon, and no one is in the least degree dismayed. I have talked and listened in two clubs, watched people in cars and in the street, and one man is glad that Chinatown will be cleared out for good; another's chief solicitude is for Millet's "Man with the Hoe." "They'll cut it out of the frame," he says, a little anxiously. "Sure." But there is no doubt anywhere that San Francisco can be rebuilt, larger, better, and soon. Just as there would be none at all if all this New York that has so obsessed me with its limitless bigness was itself a blazing ruin. I believe these people would more than half like the situation. It would give them scope, it would facilitate that conversion into white marble in progress everywhere, it would settle the difficulties of the Elevated railroad and clear out the tangles of lower New York. There is no sense of accomplishment and finality in any of these things, the largest, the finest, the tallest, are so obviously no more than symptoms and promises of Material Progress, of inhuman material progress that is so in the nature of things that no one would regret their passing. That, I say again, is at the first encounter the peculiar American effect that began directly I stepped aboard the liner, and that rises here to a towering, shining, clamorous climax. The sense of inexhaustible supply, of an ultra-human force behind it all, is, for a time, invincible.

One assumes, with Mr. Saltus, that all America is in this vein, and that this is the way the future must inevitably go. One has a vision of bright electrical subways, replacing the filth-diffusing railways of to-day, of clean, clear pavements free altogether from the fly-prolific filth of horses coming almost, as it were, of their own accord beneath the feet of a population that no longer expectorates at all; of grimy stone and peeling paint giving way everywhere to white marble and spotless surfaces, and a shining order, of everything wider, taller, cleaner, better.... So that, in the meanwhile, a certain amount of jostling and hurry and untidiness, and even—to put it mildly—forcefulness may be forgiven.

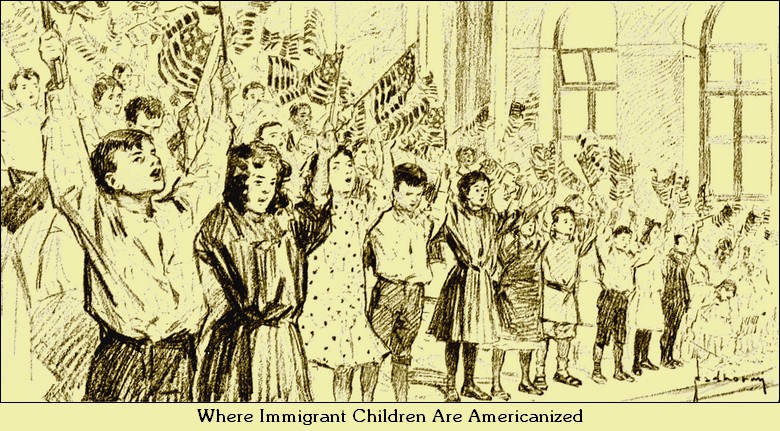

I VISITED Ellis Island yesterday. It chanced to be a good day for my purpose. For the first time in its history this filter of immigrant humanity has this week proved inadequate to the demand upon it. It was choked, and half a score of gravid liners were lying uncomfortably up the harbor, replete with twenty thousand or so of crude Americans from Ireland and Poland and Italy and Syria and Finland and Albania; men, women, children, dirt, and bags together. Of immigration I shall have to write later; what concerns me now is chiefly the wholesale and multitudinous quality of that place and its work. I made my way with my introduction along white passages and through traps and a maze of metal lattices that did for a while succeed in catching and imprisoning me, to Commissioner Wachorn, in his quiet, green-toned office. There, for a time, I sat judicially and heard him deal methodically, swiftly, sympathetically, with case after case, a string of appeals against the sentences of deportation pronounced in the busy little courts below. First would come one dingy and strangely garbed group of wild-eyed aliens, and then another: Roumanian gypsies. South Italians, Ruthenians, Swedes, each under the intelligent guidance of a uniformed interpreter, and a case would be started, a report made to Washington, and they would drop out again, hopeful or sullen or fearful as the evidence might trend....

Down-stairs we find the courts, and these seen, we traverse long refectories, long aisles of tables, and close-packed dormitories with banks of steel mattresses, tier above tier, and galleries and passages innumerable, perplexing intricacy that slowly grows systematic with the Commissioner's explanations.

Here is a huge, gray, untidy waiting-room, like a big railway-depot room, full of a sinister crowd of miserable people, loafing about or sitting dejectedly, whom America refuses, and here a second and a third such chamber each with its tragic and evil-looking crowd that hates us, and that even ventures to groan and hiss at us a little for our glimpse of its large dirty spectacle of hopeless failure, and here, squalid enough indeed, but still to some degree hopeful, are the appeal cases as yet undecided. In one place, at a bank of ranges, works an army of men cooks, in another spins the big machinery of the Ellis Island laundry, washing blankets, drying blankets, day in and day out, a big clean steamy space of hurry and rotation. Then, I recall a neat apartment lined to the ceiling with little drawers, a card-index of the names and nationalities and significant circumstances of upward of a million and a half of people who have gone on and who are yet liable to recall.

The central hall is the key of this impression. All day long, through an intricate series of metal pens, the long procession files, step by step, bearing bundles and trunks and boxes, past this examiner and that, past the quick, alert medical officers, the tallymen and the clerks. At every point immigrants are being picked out and set aside for further medical examination, for further questions, for the busy little courts; but the main procession satisfies conditions, passes on. It is a daily procession that, with a yard of space to each, would stretch over three miles, that any week in the year would more than equal in numbers that daily procession of the unemployed that is becoming a regular feature of the London winter, that in a year could put a cordon round London or New York of close-marching people, could populate a new Boston, that in a century—What in a century will it all amount to?...

On they go, from this pen to that, pen by pen, towards a desk at a little metal wicket—the gate of America. Through this metal wicket drips the immigration stream—all day long, every two or three seconds an immigrant, with a valise or a bundle, passes the little desk and goes on past the well-managed money-changing place, past the carefully organized separating ways that go to this railway or that, past the guiding, protecting officials—into a new world. The great majority are young men , and young women, between seventeen and thirty, good, youthful, hopeful, peasant stock. They stand in a long string, waiting to go through that wicket, with bundles, with little tin boxes, with cheap portmanteaus, with odd packages, in pairs, in families, alone, women with children, men with strings of dependents, young couples. All day that string of human beads waits there, jerks forward, waits again; all day and every day, constantly replenished, constantly dropping the end beads through the wicket, till the units mount to hundreds and the hundreds to thousands....

Yes, Ellis Island is quietly immense. It gives one a visible image of one aspect at least of this world-large process of filling and growing and synthesis, which is America.

"Look there!" said the Commissioner, taking me by the arm and pointing, and I saw a monster steamship far away, and already a big bulk looming up the Narrows. "It's the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. She's got—I forget the exact figures, but let us say—eight hundred and fifty-three more for us. She'll have to keep them until Friday at the earliest. And there's more behind her, and more strung out all across the Atlantic."

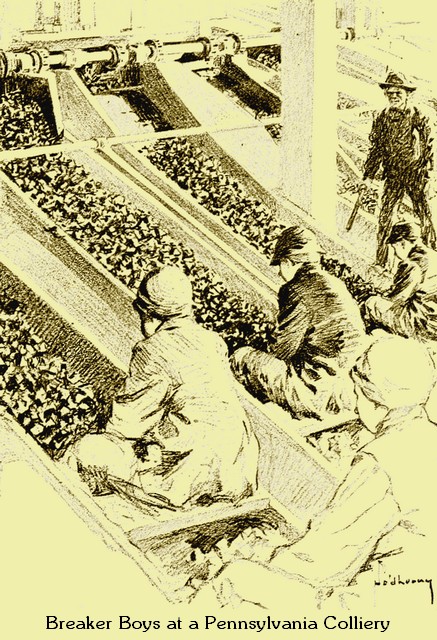

In one record day this month 21,000 immigrants came into the port of New York alone; in one week over 50,000. This year the total will be 1,200,000 souls, pouring in, finding work at once, producing no fall in wages. They start digging and building and making. Just think of the dimensions of it!

One must get away from New York to see the placc in its proper relations. I visited Staten Island and Jersey City, motored up to Sleepy Hollow (where once the Headless Horseman rode), saw suburbs and intimations of suburbs without end, and finished with the long and crowded spectacle of the East River as one sees it from the Fall River boat. It was Friday night, and the Fall River boat was in a state of fine congestion with Jews, Italians, and week-enders, and one stood crowded and surveyed the crowded shore, the sky-scrapers and tenement-houses, the huge grain elevators, big warehouses, the great Brooklyn Bridge, the still greater Williamsburgh Bridge, the great promise of yet another monstrous bridge, overwhelmingly monstrous by any European example I know, and so past long miles of city to the left and to the right past the wide Brooklyn navy-yard (where three clean white war-ships lay moored), past the clustering castellated asylums, hospitals, almshouses and reformatories of Black-well's long shore and Ward's Island, and then through a long reluctant diminuendo on each receding bank, until, indeed, New York, though it seemed incredible, had done.

And at one point a grave-voiced man in a peaked cap, with guide-books to sell, pleased me greatly by ending all idle talk suddenly with the stentorian announcement: "We are now in Hell Gate. We are now passing through Hell Gate!"

But they've blown Hell Gate open with dynamite, and it wasn't at all the Hell Gate that I read about in my boyhood in the delightful chronicle of Knickerbocker,

So through an elbowing evening (to the tune of "Cavalleria Rusticana " on an irrepressible string band) and a night of unmitigated fog-horn to Boston, which I had been given to understand was a cultured and uneventful city offering great opportunities for reflection and intellectual digestion. And, indeed, the large quiet of Beacon Street, in the early morning sunshine, seemed to more than justify that expectation....

But Boston did not propose that its less-assertive key should be misunderstood, and in a singularly short space of time I found myself climbing into a tremulous impatient motor-car in company with three enthusiastic exponents of the work of the Metropolitan Park Commission, and provided with a neatly tinted map, large and framed and glazed, to explore a fresh and more deliberate phase in this great American symphony, this symphony of Growth.

If possible it is more impressive, even, than the crowded largeness of New York, to trace the serene preparation Boston has made through this Commission to be widely and easily vast. New York's humanity has a curious air of being carried along upon a wave of irresistible prosperity, but Boston confesses design. I suppose no city in all the world (unless it be Washington) has ever produced so complete and ample a forecast of its own future as this Commission's plan of Boston. An area with a radius of between fifteen and twenty miles from the State House has been planned out and prepared for Growth. Great reservations of woodland and hill have been made, the banks of nearly all the streams and rivers and meres have been secured for public park and garden, for boating and other water sports*big avenues of vigorous young trees; a hundred and fifty yards or so wide, with driveways and ridingways and a central grassy band for electric tramways, have been prepared, and, indeed, the fair and ample and shady new Boston, the Boston of 1950, grows visibly before one's eyes. I found myself comparing the disciplined confidence of these proposals to the blind enlargement of London; London, that like a bowl of viscid human fluid, boils sullenly over the rim of its encircling hills and slops messily and uglily into the home counties. I could not but contrast their large intelHgence with the confused hesitations and waste and muddle of our English suburban developments....

There were moments, indeed, when it seemed too good to be true, and Mr. Sylvester Baxter, who was with me and whose faith has done so much to secure this mapping out of a city's growth beyond all precedent, became the victim of my doubts. "Will this enormous space of sunHt woodland and marsh and meadow really be filled at any time?" I urged. "AH cities do not grow. Cities have shrunken."

I recalled Bruges. I recalled the empty, goat-sustaining, flower-rich meadows of Rome within the wall. What made him so sure of this progressive magnificence of Boston's growth? My doubts fell on stony soil. My companions seemed to think these scepticisms inopportune, a forced eccentricity, like doubting the coming of to-morrow. Of,course Growth will go on....

The subject was changed by the sight of the fine marble buildings of the Harvard medical school, a shining fagade partially eclipsed by several dingy and unsightly wooden houses.

"These shanties will go, of course," says one of my companions. "It's proposed to take the avenue right across this space straight to the schools."

"You'll have to fill the marsh, then, and buy the houses."

"Sure."...

I find myself comparing this huge growth process of America with the things in my own land. After all, this growth is no distinctive American thing; it is the same process anywhere—only in America there are no disguises, no complications. Come to think of it, Birmingham and Manchester are as new as Boston—newer; and London, south and east of the Thames, is, save for a little nucleus, more recent than Chicago—is in places, I am told, with its smoky disorder, its clattering ways, its brutality of industrial conflict, very like Chicago. But nowhere now is growth still so certainly and confidently going on as here. Nowhere is it upon so great a scale as here, and with so confident an outlook towards the things to come. And nowhere is it passing more certainly from the first phase of a moblike rush of individualistic undertakings into a planned and ordered progress.

Everywhere in the America I have seen the same note sounds, the note of a fatal gigantic economic development, of large prevision and enormous pressures.

I heard it clear above the roar of Niagara—for, after all, I stopped off at Niagara.

As a water-fall, Niagara's claim to distinction is now mainly quantitative; its spectacular effect, its magnificent and humbling size and splendor, were long since destroyed beyond recovery by the hotels, the factories, the power-houses, the bridges and tramways and hoardings that arose about it. It must have been a fine thing to happen upon suddenly after a day of solitary travel; the Indians, they say, gave it worship; but it's no great wonder to reach it by trolley-car, through a street hack-infested and full of adventurous refreshment-places and souvenir-shops and the touting guides. There were great quantities of young couples and other sight-seers with the usual encumbrances of wrap and bag and umbrella, trailing out across the bridges and along the neat paths of the Reservation Parks, asking the way to this point and that. Notice boards cut the eye, offering extra joys and memorable objects for twenty-five and fifty cents, and it was proposed you should keep off the grass.

After all, the gorge of Niagara is very like any good gorge in the Ardennes, except that it has more water; it's about as wide and about as deep, and there is no effect at all that one has not seen a dozen times in other cascades. One gets all the water one wants at Tivoli, one has gone behind half a hundred downpours just as impressive in Switzerland; a hundred tons of water is really just as stunning as ten million. A hundred tons of water stuns one altogether, and what more do you want? One recalls "Orridos" and "Schluchts" that are not only magnificent but lonely.

No doubt the Falls, seen from the Canadian side, have a peculiar long majesty of effect; but the finest thing in it all, to my mind, was not Niagara at all, but to look up-stream from Goat Island and see the sea-wide crest of the flashing sunlit rapids against the gray-blue sky. That was like a limitless ocean pouring down a sloping world towards one, and I lingered, held by that, returning to it through an indolent afternoon. It gripped the imagination as nothing else there seemed to do. It was so broad an infinitude of splash at^d hurry. And, moreover, all the enterprising hotels and expectant trippers were out of sight.

That was the best of the display. The real interest of Niagara for me, was not in the water-fall but in the human accumulations about it. They stood for the future, threats and promises, and the water-fall was just a vast reiteration of falling water. The note of growth in human accomplishment rose clear and triumphant above the elemental thunder.

For the most part these accumulations of human effort about Niagara are extremely defiling and ugly. Nothing—not even the hotel signs and advertisement boards—could be more offensive to the eye and mind than the Schoellkopf Company's untidy confusion of sheds and buildings on the American side, wastefully squirting out long, tail-race cascades below the bridge, and nothing more disgusting than the sewer-pipes and gas-work ooze that the town of Niagara Falls contributes to the scenery. But, after all, these represent only the first slovenly onslaught of mankind's expansion, the pioneers' camp of the human-growth process that already changes its quality and manner. There are finer things than these outrages to be found.

The dynamos and turbines of the Niagara Falls Power Company, for example, impressed me far more profoundly than the Cave of the Winds; are, indeed, to my mind, greater and more beautiful than that accidental eddying of air beside a downpour. They are will made visible, thought translated into easy and commanding things. They are clean, noiseless, and starkly powerful. All the clatter and tumult of the early age of machinery is past and gone here; there is no smoke, no coal grit, no dirt at all. The wheel-pit into which one descends has an almost cloistered quiet about its softly humming turbines. These are altogether noble masses of machinery, huge black slumbering monsters, great sleeping tops that engender irresistible forces in their sleep. They sprang, armed like Minerva, from serene and speculative, foreseeing and endeavoring brains. First was the word and then these powers. A man goes to and fro quietly in the long, clean hall of the dynamos. There is no clangor, no racket. Yet the outer rim of the big generators is spinning at the pace of a hundred thousand miles an hour; the dazzling clean switchboard, with its little handles and levers, is the seat of empire over more power than the strength of a million disciplined, unquestioning men. All these great things are as silent, as wonderfully made, as the heart in a living body, and stouter and stronger than that....

When I thought that these two huge wheel-pits of this company are themselves but a little intimation of what can be done in this way, what will be done in this way, my imagination towered above me. I fell into a day-dream of the coming power of men, and how that power may be used by them....

For surely the greatness of life is still to come, it is not in such accidents as mountains or the sea. I have seen the splendor of the mountains, sunrise and sunset among them, and the waste immensity of sky and sea. I am not bUnd because I can see beyond these glories. To me no other thing is credible than that all the natural beauty in the world is only so much material for the imagination and the mind, so many hints and suggestions for art and creation. Whatever is, is but the lure and symbol towards what can be willed and done. Man lives to make—in the end he must make, for there will be nothing else left for him to do.

And the world he will make—after a thousand years or so!

I, at least, can forgive the loss of all the accidental, unmeaning beauty that is going for the sake of the beauty of fine order and intention that will come. I believe—passionately, as a doubting lover believes in his mistress—in the future of mankind. And so to me it seems altogether well that all the froth and hurry of Niagara at last, all of it, dying into hungry canals of intake, should rise again in light and power, in ordered and equipped and proud and beautiful humanity, in cities and palaces and the emancipated souls and hearts of men....

I turned back to look at the povv^er-house as I walked towards the Falls, and halted and stared. Its architecture brought me out of my day-dream to the quality of contemporary things again. It's a well-intentioned building enough, extraordinarily well intentioned, and regardless of expense. It's in granite and by Stanford White, and yet—It hasn't caught the note. There's a touch of respectability in it, more than a hint of the box of bricks. Odd, but I'd almost as soon have had one of the Schoellkopf sheds.

A community that can produce such things as those turbines and dynamos, and then cover them over with this dull exterior, is capable, one realizes, of feats of bathos. One feels that all the power that throbs in the copper cables below may end at last in turning Great Wheels for excursionists, stamping out aluminum "fancy" ware, and illuminating night advertisements for drug shops and music halls. I had an afternoon of busy doubts,...