RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

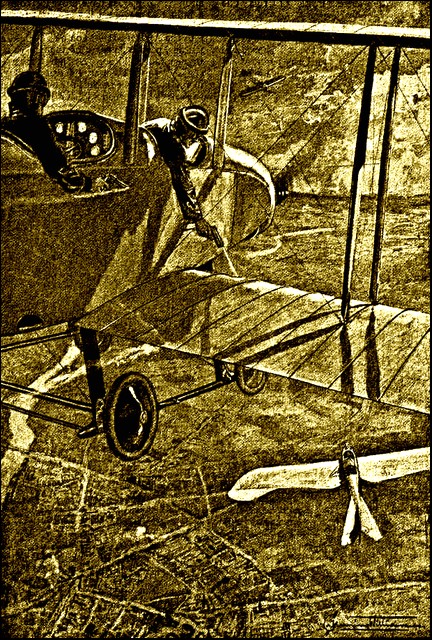

A pistol fight between a British Bristol biplane and a German

Taube monoplane, with a French Blériot flying to join the attack.

NO real thing is ever simple, for simplicity is reached by attraction, and this great struggle of the nations that thunders about the world is made up of many factors and presents innumerable aspects. Primarily it is a struggle of the spirit of freedom and pacific civilisation against the long-gathered attack of German militarism; but into this issue come elaborations, in the Russian situation, in the Balkan developments, in the mute but very real conflict to control the war between Imperialism and Liberalism in Great Britain, for example. And sustaining German militarism is German patriotism, a thing one may still honour even when one considers it to be at present aggressive and misled. And German militarism in itself is not simple. We are fighting against a double-headed monster. A moiety of it is as old as old Prussia. The Junker-directed soldiering and the military policy of Germany are to-day extraordinarily the same as they were in the days of Frederick the Great. And a moiety of it is newer than the present century. This extreme efficiency in the German organisation of material, the new devices and inventions, the Kruppism, the Zeppelinism, present absolutely unprecedented aspects of war. The journalistic mind has seized upon this duality in its denunciation of the "Krupp-Kaiser combination." And, so far as the Kaiser-Junker side of the war is concerned, that head may be counted dead and done for already. The old swagger, the prancing monarch, the flags, the dumb, brave obedience of the ranked soldiers, the shouting victories, the war pictures—these things have gone to join pikes and chain armour in the historical museum. The Kaiser now keeps out of the limelight for fear of aerial bombs; the Crown Prince, having confused his strategy and stolen snuff boxes, has passed into a mysterious obscurity; the once invincible massed infantry has fallen in swathes at Liège and Mons and a score of fights; it has choked the Belgian rivers until the waters have found new courses; its prestige has melted to nothing before the steady fire of English "mercenaries" in open order; in Flanders it has fled before Hindu bayonets and screamed at the sight of brown faces; the German cavalry has been ridden through by the British, one to three. The old soldierliness of the German, booted and spurred, has departed out of the world. Coming to the fore to replace it is the new thing—the industrious and voluminous German intelligence concentrated upon war material. The submarine, the Zeppelin, the great gun, the entrenching plough, must save Germany now, if Germany is to be saved from the punishments of her aggressions. The old war passes into the new war.

Now, the new war is no invention of Germany's. But it is a fact too little heeded in this world that the type of mind that is least creative is often the one that can best use an invention. The aeroplane is American, the submarine is French, the ironclad was first American, then French, and then English, the "navigable" is French, the private armaments firms, that are now the most portentous fact in the world, began their career in Great Britain. Armstrong came before Krupp. We reap what we have sown. Essen and Frederickshaven are only the reaction of the methodical, indefatigable German mind to the initiatives of the intellectually more virile peoples. But it is certainly a terrible reaction. Every fresh phase of the war shows more clearly how completely the German imagination has been obsessed by the idea of systematic war preparation. All the energy of sixty million people has been concentrated upon the scientific war business in a way that is almost incredible to the versatile anarchic American or Englishman or Frenchman. Every fresh phase of the war, indeed, justifies the determination of the Allies to end for ever the belligerent culture of Germany. For four decades all German life has been made to subserve that dream of a scientifically perfect war equipment. It has drained the life and wits out of the cavalry and infantry that were once so able; it has left German diplomacy brainless and tactless; it has eaten up the literature, the philosophy, the criticism, the emotion of a whole people. But it has certainly been carried out with a magnificent thoroughness. An organisation of equipment, a military intelligence department, a system of military espionage, a scientific preparation of war plans, have been carried to a pitch unparalleled in the world's history. Our generation has been privileged to witness the spectacle of a military machine in action such as mankind has never seen before and, I hope, will never tolerate again. It is useless to pretend that all the Allies together have anything to equal the marvels of the German apparatus. It is by the forces inherent in sane humanity, by the individual superiority of their rank and file, by a desperate resolve to endure militant Germany no longer, that they win and will continue to win in the face of these tremendous achievements, gathering fresh allies with each new confirmation of German efficiency.

Let us consider the novelties this war has produced. In the first place, it is a petrol war. For the first time war has been fought over a country so highly civilised as to possess abundant good roads. This gave Germany an immense advantage. She found Luxemburg, Belgium, and, in a lesser degree, France, unprepared for her onslaught, as every sane country whose abilities are intelligently dispersed must necessarily be unprepared. The Germans, therefore, had all the advantage of an armed monomaniac who attacks suddenly, and their first rush upon Paris was made by the best-equipped host that has ever carried fire and murder through a peaceful countryside. Vast railway sidings had been prepared upon the Belgian frontier to facilitate the movement of troops; special great guns were ready to smash the obsolescent Belgian fortresses. These first German hosts were so equipped that even the field-glasses for the riflemen who were to pick off the French and Belgian officers had not been forgotten. The surprise of Liège failed, indeed, but the big guns remedied that. Namur, Maubeuge, were cracked like walnuts. The wave poured on. Over this stupendous advance soared an overwhelming number of aeroplanes, and along every road poured the automobiles. It was the mechanical perfection of belligerency. Before it there retreated thin lines of khaki riflemen, shooting very well, and a field artillery handled by Frenchmen and Englishmen, and to the north certain troops of curiously embittered Belgians, unconvinced by these machines. The collapse of France looked for a time inevitable. Yet these men outfought the German soldiers. Slowly, day by day, they corrected their disadvantage of material. Slowly the friction of the resistances was beating the best and biggest army in history.

Within a few miles of Paris the German rush collapsed. The roads behind, choked with its killed and wounded, smashed automobiles, and broken guns, served no longer to maintain the supply of food or ammunition. The obstinate Belgians had broken up their railway system and got all their rolling-stock away, and at a little distance from the Prussian frontier the German supplies had to take to the congested and ploughed-up highways. Slowly the resistance gathered, and, as I write, the huge ruins of that great invasion, the most tremendous advance in history, beaten back from the Marne, strained by a perpetual stretching to the west, perish slowly along the line of the Aisne. And all the while Germany has been using petrol. No doubt German foresight provided great stores of petrol for a three months' war. But the war still goes on, conquest fades from the German dream, and the Germans have used petrol beyond measuring for transport, for Zeppelins, for those remarkable incendiary bombs that flared through the streets of Antwerp, for every conceivable purpose. There are no German sources of petrol. Only from America and Roumania—neither of which countries is anxious to see the German military monomania dominate the world—and through the by no means enthusiastic channels of Holland, Norway, and Denmark can petrol reach Germany. So that it may be possible for the United States and Roumania presently to turn off this war as one turns off a gas-jet. That is the first extraordinary aspect of this unprecedented war. Suddenly it may become preventable through the sheer waste of this one necessity.

And the next most remarkable aspect of this war is the fact that compulsory military service, combined with the telephone, the telegraph, and the modern facilities of transport, has practically abolished the "civilian." Germany evidently intends to put her whole adult male population into the fighting line before the end of this war, and she has made a prisoner of war of every adult male of mobilisable age of the Allies that she could catch. Her punitive treatment of towns and villages has practically abolished the last immunity of the "non-combatant." Entire populations are fighting now, and fighting with a disregard for the ancient amenities of warfare, for which the German scientific conception of permissible pressure and strategems is directly responsible. It is a very curious and instructive thing to talk to Belgian refugees or British wounded soldiers, and to mark the savage resentment that has developed against the Germans since the first month of the war. At first the English were quite good-tempered. Slowly the Belgian outrages have turned their kindly dispositions to hatred. If a German raid were now to reach England, it would not be fought simply by the Regular troops; it would be set upon and lynched by the general population. The last traces of the eighteenth-century convention that war was a business confined to men in uniform are fading out of human thought under the stress of "scientific" methods.

And then come the actual machines.

There is something preposterously logical in the way in which metallurgy and chemistry and engineering have, under sound commercial stimulus, taken the ancient claptrap of militarism and worked it out in Europe and on the high seas. The Germans have permitted this to happen to the completest extent because they are the most thorough-minded and least subtle people in Europe. Devotion to military preparation bores all intelligent minds, but it has bored the phlegmatic German less than it has bored the English or Irish or French. And their Prussian Government has used press and picture to make the business attractive and exciting to its vulgar tax-payer. It has always, to give them something for their money, kept a good shop-window in the street, and from this it has followed that at times the German goods have been rather of the shop-window than the efficient type. This is particularly the case with the aircraft. Zeppelins have proved as complete a failure as we journalist prophets foretold. Their sole feat has been to drop a few bombs into the Antwerp streets on a still night and murder, perhaps, a score of inoffensive men, women, and children. As an agreeable side-consequence of the war, I have now staying in my house an electrician who was a Garde Civile of Antwerp, and who left the town only after the wire entanglements, in which he bad been keeping certain wires alive and dangerous, were smashed up. He saw a number of shells fall—he was knocked off his "velo" by the concussion of one of them—and he has given me very illuminating particulars of the whole business. His contempt for the Zeppelins is extreme. The six that "rained fire" upon Antwerp in the newspaper headlines were fabulous monsters—none shared in the bombardment at all—and of the earlier visitants one was ripped in eleven compartments and disabled by rifle fire alone. It escaped capture only by dropping all its bombs en masse and everything else that was detachable—happily into a field. Except in calm weather these huge gas sausages are uncontrollable and useless. And the German aeroplanes, though extremely numerous and a source of grave inconvenience as range-finders for the artillery in the earlier stages of the war, are individually inferior to the British. Both the English and French chase and destroy them. The observers fight with repeating rifles, and the Allied machines seem to be not only better handled, but quicker and easier to manoeuvre. The combatants fly with the view of getting a raking fire across the antagonist's propeller, so that he is unable to reply except at the risk of breaking his own blades. Slowly but surely the aerial ascendancy is being recovered by the Allied Powers. It is not only that they make better machines and faster, but that they make better aviators. The northern Frenchman and many Scotch and English types have a much greater aptitude than any German for all this sort of work; and it is probable that as the battle-line sags back towards the Allied objective in Westphalia, the Allies will have the complete command of the air, and Germany will fight blind.

It is as a scout, and more particularly as an accessory to the artillery, that the aeroplane figures in the new war. With regard to artillery, the Germans have the advantage that results from intensity of intention. Of any gun it may be said: "Why not a larger?" There is no limit to the size of guns except the sanity of their makers. There is, for example, no scientific improbability in making a gun that could be fired from New York to smash London. There are only moral and everyday practical objections. Such a gun could be made, loaded, and fired, if all America wanted to have it and Europe did not interfere to prevent it, and London could be destroyed and burnt by it. Incidentally, New York would be shaken to pieces by the concussion, and most of the people of the Eastern States would be spun about like straws in a whirlwind; but these considerations would probably not restrain a people really obsessed by the culture of military magnificence. And in the making of guns, the Germans, even if they have not yet gone to that extent, have at any rate carried the answer of "Why not a larger?" to a quite astonishing point.

It is manifest that if a nation devotes its full energies to such a research, the other nations in the world must either put a stop to that development, or follow suit, or go under. So far as ordinary field guns go, the German artillery, if more numerous, is in no other way superior to that of the Allies. But in the matter of big guns they altogether outclass their antagonists. A new piece is put upon the chessboard of war, in the form of guns vaster than any pre-existing siege guns, great guns that can yet be moved—cumbrously, but still moved—from position to position. At a blow, therefore, fixed fortifications are abolished as a refuge for inferior forces on the defensive, and the whole strategic method is changed. These pieces are so large that they must be fired by gunners using electricity at some slight distance, and they must be extremely destructive to all the small gear in the immediate vicinity. They can be fired only at an enormous cost, and, with any chance of success, only at a fixed target. They must need emplacements of very great solidity, and obviously they are open to counter-attack both through the air and by ordinary troops. They need, therefore, a strong guard to protect them, a little complete defensive force with ordinary guns and machine-guns, and they are far more valuable to a superior attacking force than to a retreating one. They also need open and good communication for supplies, and they are of no avail against infantry in a sanely contrived system of trenches and against an infantry attack. Their use means the thrusting forward of a kind of gun-fort into the enemy's country that may easily become an embarrassing entanglement. The larger they are, the more formidable they are, the more do they commit their user to a certain line and certain positions, and compel their antagonist to dispersed tactics and movement. They are, indeed, a species of military Juggernaut; one figures the little soldiers about them, hauling them forward to perform their wonders, very much like the servitors of a new religion. These things are, indeed, strangely like gods—squatting, gaping, death-sending gods—to which men have given their souls.

These monsters have cracked the armour of Belgium and France, but they cannot break the net of entrenched men that now holds the bled and weary German armies. At Verdun and Belfort the French have advanced and entrenched, so that the forts are beyond the utmost range of the new German deities. These lift their black muzzles in vain towards the useless forts they can no longer injure. Legend has it that still larger guns are being made—guns that will fire across the Channel from Calais to England. But let them, if they can, fire from Berlin to London, and burst their hearts with their effort. It matters not to the Allies, if men care more for freedom than buildings. Germany may put her last strength into these guns; they will not bring back the troops whose bodies already choke the streams and trenches from the Meuse to the Yser, and from the Marne to the Scheldt. Each month Germany and Austria waste against a growing enemy, in killed, wounded, and prisoners, close upon a million men. Before the spring they must be worn down and pierced and outflanked, and then this titanic ironmongery will fall a spoil to the civilisation its existence has outraged.

No doubt much ingenuity will stand between the Allies and the capture of Essen, where these things are made, and which is the real heart of the new Germany we fight. But Creusot-Schneider, Armstrongs, Vickers-Maxim, are on their mettle, and the Allies are no longer lax. They are fighting for their lives now, with better brains and better men than Germany. The Germans begun, and the Allies will end, at their maximum of destructive efficiency. Strange dragons and wonderful beasts of steel will battle in Westphalia before the end, but the end will be the downfall of Essen and Kruppism for ever.

Upon the sea the warnings of the prophets have also been confirmed. The great ironclad, though still necessary for the control of the ocean, is no longer the unchallenged mistress of the seas. There is no perfect command of the seas any more. The mine and the submarine, elusive and unavoidable, have made the narrow waters unsafe even for an overwhelmingly predominant fleet. Naval warfare has become a mechanical assassination. The successes of these insidious devices are not, it is true, considerable enough to destroy a predominance, but they can distress and hamper and keep an enemy out of shallow waters and protected straits and river mouths to a quite unprecedented extent. They have not been able to prevent the English transporting enormous quantities of troops and material to France, nor have they opened any way for a retaliatory raid, but they have kept the Grand Fleet out of the Baltic and off the Friesland coasts and islands. They are purblind antagonists, one must admit, that must be blundered upon, and such successes as they have had have been attained chiefly by ruses—by the submarine waiting upon some decoy ship—a trawler with the Dutch flag, or such-like Teutonic device—that stopped the victim ship by provoking a challenge, and so made it a mark. After the Hawk was sunk, a submarine followed the solitary boatload of survivors as a shark will follow a raft, in the hope that some other British warship would expose herself by slowing down to pick up these exhausted men.

If you try to imagine the mental states of the officers of that submarine, you will realise why this paper is headed "The Lifeless Monster that Kills the Souls and Bodies of Men." You will realise why the spirit of man rises in revolt against these hellish new developments of his ancient crime of war. For it is not only that men now suffer wounds more horrible than any that the swords and spears of ancient warfare were capable of inflicting at the worst, not only that they are rent and smashed as no men have ever been rent and smashed before, not even by the insanest tyrants, not by the cruellest savages who ever contrived torments, but that their minds are deadened and distorted to the service of these mechanical devils. In Antwerp, when my visitor left it, there were splashes of blood about in the streets everywhere, and after one explosion there was picked up, amidst much other débris, the arm and shoulder-blade of a woman with some bloody rags of clothing. One man was sitting by his dying wife. There was an uproar in the street, and he went out upon the balcony to look at the Zeppelin at which the forts were firing shrapnel. He was hit by the shrapnel bullets and immediately decapitated. His wife, unaware of his misadventure, called to him and then called again. She kept telling him in her fading voice to come in out of the danger.

You see what the scientific development of armaments is doing for the world.

There is no way of stopping this scientific development of warfare without a common law against war equipment, the setting up by a confederation of states, above all existing governments, of a common law that shall rule the earth. This may be possible when the militarist delusions of Germany are destroyed. It certainly will not be until they are. For all the rest of the world is sick of war. And presently one neutral Power will probably hold in its hands the decision, because it will control petrol and other necessary supplies. The United States, by declaring war upon Germany, could oblige her to evacuate Belgium, indemnify her antagonists, and disarm in two months without risking a soldier. The United States, if her people had a mind for it at the present time, could force an abandonment of armaments and a universal agreement to substitute litigation for fighting, upon the whole world. Every week of mutual exhaustion now going on in Europe increases the tremendous power of intervention that the United States may exercise.