RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

Blue Book, October 1946, with "Son of Julius Caesar"

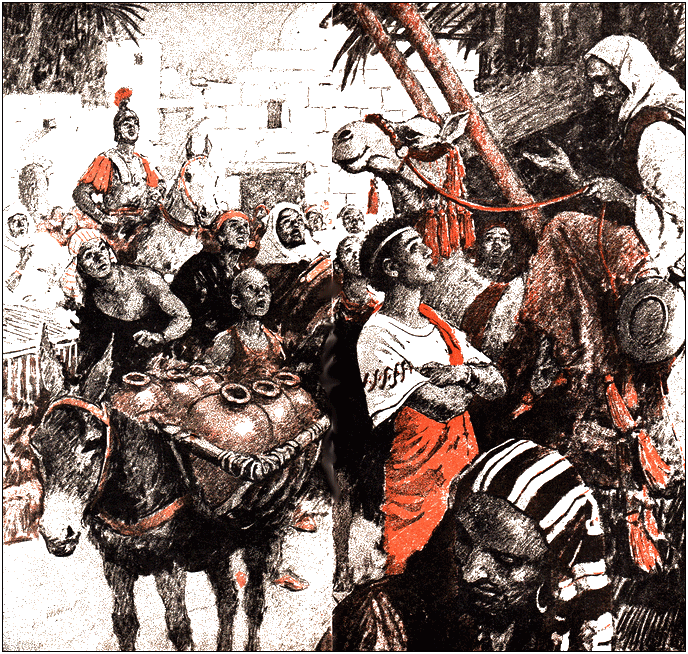

These Sphinx Emerald stories are a veritable

Outline of History.

Here the tragic young Caesarion dominates

the scene.

THE finest house in Berenice—not so very fine, at that—stood on the sands above the harbor, looking out to sea: the Red Sea, blistering hot in this midsummer. Behind the town the desert mountains reached back to mid-Egypt. The caravan trail came from Coptos on the Nile here to Berenice, the route of all commerce between Egypt and the Far East. Here in the shallow harbor of Berenice ships were crowded, awaiting the July change of monsoon. Then for six months the winds would blow eastward, the merchant traders coursing before it to far India, whence they would return when the monsoon changed again and blew westward for another six months.

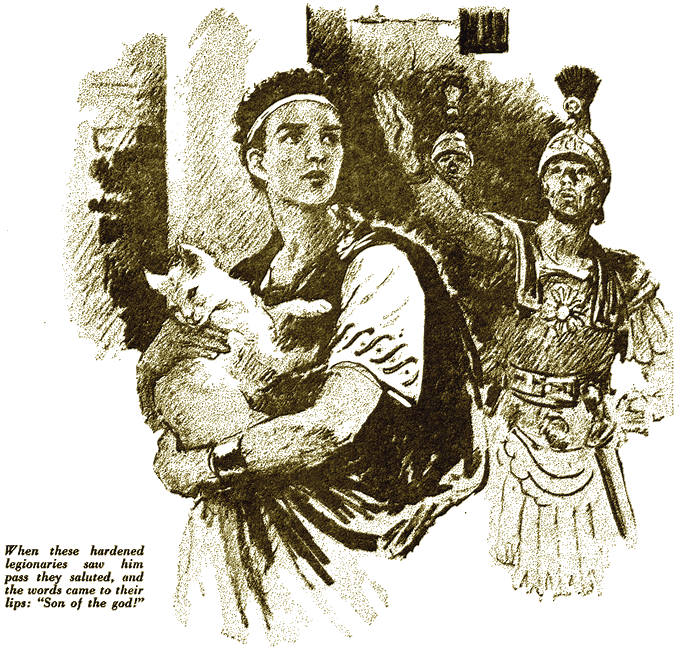

The house was stocked with luxuries for the boy, his tutors and his guards, who stayed here waiting for the ships to move. The tutor Rhodon was a pleasant, amiable weakling of forty-five, a Greek; the soldiers who guarded the house had small respect for him. These soldiers were Romans, men who had served Marc Antony; and they were blindly devoted to the boy. He was seventeen; he had passed the ceremonies of manhood, and had been crowned as co- ruler of Egypt with his mother Cleopatra; but to these hardened legionaries, he was "the boy." When they saw him pass, they stiffly saluted, and the murmured Roman words came to their lips:

"Son of the god!"

For Julius Caesar had been deified and was worshiped as a god. This boy was like him in every way. He was, in fact Caesar, the son of Julius Caesar, though he was usually known by the affectionate diminutive of the name, Caesarion.

Yet, though Caesarion was son of the divine Julius, and King of Egypt, with many another shadowy title, it was the tutor Rhodon who was nominally in command here. Cleopatra and Antony were in Alexandria, besieged by the vindictive and ambitious Octavian; in desperation Cleopatra had sent her son here, with immense treasures, to join the fleet for India, and to seek refuge in Hindustan, where there were no ambitious Romans. They had come. The ships were ready, with the treasure on board—but until the monsoon broke, could not move...

"We never spoke of this in Alexandria, so I don't understand it very well," said Caesarion. He and Rhodon sat in the patio of the house, nominally reading Homer. "You say that Octavian is the nephew and the son of my father?"

"Your father adopted him in the Roman fashion, yes," said Rhodon, "but acknowledged you as his son before he died. So Antony is dead! Poor Antony—he was a noble fellow in his day."

A courier had come that morning with the dread news from Alexandria.

"Will Octavian harm my mother?" Caesarion asked. "She always said he was a vicious beast. They called him 'the Executioner' in Rome."

"No, he'll not harm her; she's perfectly safe." Rhodon stretched leisurely. "He's not a bad sort, really. He's Caesar now, of course."

"But I'm Caesar!"

"Yes. And you're King of Egypt; but Octavian has Egypt, and you haven't. We'll make up for that in India. I have letters from your mother to all the princes there, if you decide to go there."

"If?" Caesarion looked keenly at the Greek, who smiled.

"Yes. It's for you to say, of course. We'll know by the next courier what's taken place in Alexandria."

"I'm going down to the shore and think. I want to be alone," said Caesarion.

He rose and left the palace, bidding the guards stay where they were. Trudging through the hot sand, he went down to the beach, where the tide was out, and sat by the water, looking out at the listless ships.

He sat by the water, looking out at the listless ships.

Indeed he was like his father, finely carven of features, hard-limbed, driven by a fierce will and resolution; yet at the moment he was bewildered by destiny. He knew that he was the dream of his mother's life. For him Cleopatra had plundered Egypt, had gathered this fleet, had made certain that by her defiance of the conquering Octavian he might safely get away to the Far East, with followers and treasure fitting to a king.

But now—this news about Antony's death was grave. It would be days ere the monsoon broke, and days might count heavily. Nor was Caesarion at all sure that flight was his wisest course. He did not know fear. Assuredly he had no fear of Octavian, the money-lender's son who had wormed his way into the family of Caesar by marriage and by adoption, a cold, cheaply conniving rascal, and a coward. Such a man could not hurt the son of the divine Julius. According to the philosophers, a man was the only person who could harm himself; no other could.

So, thought Caesarion, it was odd that Rhodon seemed to think Octavian a great and splendid person. Rhodon, whom his mother trusted, ought to know the truth. With a sigh, Caesarion stirred, took from his girdle a gem that flashed with pale green fire in the sunlight, and holding it in his palm, began to study it.

The gem was an emerald that Cleopatra had given to him when he was made co-ruler of Egypt with her. Some said it was from the ancient crown jewels. There was no other like it in the world. It was a natural cabochon, of second-rate shape and color. Poor heroic, foolish Antony had said it was accursed; but Cleopatra had loved it, and so did Caesarion. But not for itself, nor for the thing in it.

Amazingly, when one gazed into the great gem through an enlarging glass, a shape appeared in it, clear-cut and distinct. The flaws and bubbles contained in this, as in all emeralds, came together at one point and assumed the exact shape of the Sphinx. Caesarion had heard there were two identical Sphinxes, one by the Pyramids, and another, almost forgotten, in the desert hills east of the Nile, near the petrified forest. This bit of beryl was a freak of nature—but it had also something more, something that fascinated him and gripped him in steely hands. It had a power.

HE stared at the stone now, as always, with a fearful and

complete absorption. It stirred him out of himself; it wakened

strange, wonderful things within him, caught at his imagination

like a blast of clarion trumpets. Antony had cursed it furiously.

A priest had said that it held the magic of the gods. His mother

had called it most beautiful, as in fact it was. But to Caesar's

son it was magnificent and splendid beyond words. It awed him,

enthralled him, brought majestic thoughts and fantasies to his

mind. It spoke to him of the great father he had never known in

the flesh—the man who was now worshiped as a god.

In sheer sober fact, this Sphinx emerald had been famed in history for its hypnotic power, which was never twice alike. It stripped the beholder of poses and drew from him the secrets of his inmost being, whether noble, glorious, base or cowardly. It called to the surface the real person, the character at bottom. To the son of Caesar, it whispered of grandeur and authority and command, shaming him bitterly for being the fugitive that he now was...

When he had gazed into the great green stone for a lengthy while, he tucked it away and rose, and returned to the hilltop house. When he came back to the courtyard, where his tutor sat writing, there was a glory in his face that made the guards stare after him, astonished.

"Rhodon!" His voice held a bite—it was the voice of Julius. He sat and caressed the cat which had joined him. It was an enormous sacred cat such as was worshiped at Bubastis in Lower Egypt, and had been given him there as they passed through. The animal had some affection for him.

"Tell me something: My mother—Antony—all of them hate and fear Octavian terribly. They said Egypt was not safe for me, that he would pursue me to the world's end, that only in India could I find refuge, that he means to kill me because I am the real Caesar, son of Julius. Now that we're far from Alexandria, ready to depart for India with the ships—I ask you, are these things true?"

Rhodon, troubled by this appeal, fingered his chin thoughtfully. He was an honest fellow in his own way.

"Well, Caesar, at least they thought them true," he responded. "Antony fought this man for the world—and lost. Until he began to grow old and dull, he had every talent and gift and ability, and the greatest luck in everything. Your mother had the one thing he lacked—something which most men lack; and that is loyalty. In her eyes Octavian was what they called him in Rome—the Executioner, who slew everyone in his road to power. He was a real friend to Caesar, who adopted him in return. Your mother saw him only as a rascal, a cheap and merciless cheat from the gutter. She told the truth, as she saw it... I'm trying to be quite honest, you see."

"Then try harder," snapped Caesarion. "I know what they said and thought. I'm asking now what you yourself think, regardless of prejudice? Do you hold this man Octavian to be a scoundrel?"

Rhodon smiled uneasily.

"No scoundrel is such, Caesar, entirely. The vilest gutter-rat may show charity or kindness. The noblest prince may be guilty of the lowest deeds at times. This man has great luck, great ambition, and a certain hard ability. You, as the true heir of Julius, stand in his way; a dangerous place indeed. However, since you're thinking about such matters, show me your mind. What do you yourself think about him?"

"I'll tell you," said Caesarion, a flash in his eye. "Octavian has won his way to the top in Rome. He has mastered Antony and my mother; he has Egypt. A man can't get to such position by being a fool or a coward or rascal. He must have character, strength, nobility of a sort. Luck alone can't make or break a man."

"True, yes," murmured Rhodon. Perhaps he was conscious of his own weakness as compared with the vibrant energy of this young man.

"And am I, Caesar, to run away from the shadow of this false Caesar?" Scorn and anger blazed in the words. "Did my father, Julius, earn his fame by running and hiding his head like an ostrich? I've no ambition to fight him, of course—I've nothing with which to fight him, and no reason for it either. If I thought he'd grant me some small place of my own where I could live and study in peace, I'd take it gladly."

RHODON looked startled. "Careful, my son! Octavian has no

loyalty to anything, I warn you! No loyalty to the gods, to

family ties, to anything at all!"

"And can you tell me such a man rules the world? I don't believe it. Such a thing is in itself a contradiction," snapped Caesarion.

Rhodon gave him an uneasy glance. "I wish you'd stop playing with that accursed emerald," he grunted. "I agree with Antony that the stone has a devil in it."

Caesarion's features softened.

"I agree with my mother that it has a high nobility in it that neither you nor Antony could ever comprehend," he said with flat finality... "No word yet from the ship captains about sailing?"

"We can't sail till the monsoon breaks."

"Even if we want to sail! I'm not sure that I'm sailing, Rhodon. You may yet learn to your surprise that your pupil has Caesar's will, no less than his name," said Caesarion abruptly, and turned into the house. Rhodon looked after him with eyes of fear. This young fellow had a mind of his own, certainly, and might kick over the traces...

Next morning came, with never a wisp of cloud to break the heat-filled coppery sky. Caesarion and a number of the guards took to the water, shark-knives at their waists, and swam out to the ships among them; but the water itself was warm and lifeless, and the sport palled on them. They came ashore, slipped into cool garments, and then, hearing the shouts of arrival, turned to the town, where a caravan was just coming in from Coptos, on the Nile below Thebes. Such caravans arrived almost every day with goods and lading for the ships.

In the marketplace of the hot, sun-smitten little town, they found it. With the horses and asses and men there was one camel—a strange beast of burden, almost unknown as yet in Egypt; and everyone was gathered to stare at him. The rider was a tall, one-eyed, dark man. He smiled when Caesarion came up to stare curiously at the camel, and spoke in very good Greek.

"So, young sir, you stare at the strange beast? Well, they're common in other lands; and the Romans, I hear, mean to put them to work in Egypt. Ugly, eh?"

"Hideous," agreed Caesarion; "yet somehow attractive, like ugly men."

"Quite true." The one eye peered sharply. "Perhaps you can tell me where to find in this town a certain party to whom I have an errand. I have goods to go aboard the ships yonder, before I return to Coptos, and also have a letter to deliver to one Rhodon, a Greek. It is a letter from some person at court—the former court."

Caesarion turned and met the one sparkling, glinting eye. His own eyes were very bright and quick. He pointed to the villa on the hill above town.

"That's his house, for the moment. He's my tutor."

"Oh! Indeed!" The dark man's tone changed. Astonishment came into his one eye.

"A negligent tutor, to let his pupil wander about the place thus," he said, in his voice a subtle play of meaning. "Sir, my name is Chandra Ghose. I am a trader of Alexandria, though I was born in farther India." His voice dropped almost to a whisper. "Should I salute you as do the Egyptians, with both palms down?"

Caesarion met the one firm, glinting eye. He caught the allusion instantly. Only a Pharaoh was saluted in that fashion—and he himself was a Pharaoh, the last Pharaoh of Egypt. He gathered that this Indian was a friend.

"You certainly should not," he replied, laughing a little. A slight stutter crept into his words. It came only at excited moments, an inheritance from his long-dead father. "It would make people stare. Have you a letter for me also?" the lad asked.

"No," replied Chandra Ghose. "Only a message—a little one of three words: _Trust no one._ A woman gave me the message, and repeated the two last words—_no one!_"

Caesarion met the one glinting eye and nodded.

"Thank you," he said. "I'll take you to Rhodon, if you like."

The Hindu joined him.

"Careless guards, careless tutor," he said, low-voiced.

"What need to be careful?"

"I'll tell you. When first I came to Alexandria, a year or more ago, I fell in with a retired Roman soldier. He was an old fellow who had served with Julius Caesar in Gaul, wherever that is, and had been invalided. Well, we went to a ceremony not many months ago. We saw the crowning of young Caesarion. This old fellow—his name was Aulus something—nearly had a fit. He gripped my arm and panted. He had known Julius intimately, he told me, and then pointed to the new co-ruler. 'That is no boy yonder,' said he; 'it is the divine Julius himself, in person!' The story might interest you."

The story not only interested Caesarion; it delighted him beyond measure; it complimented and excited him, as did any intimate little story about the famed father he had never known. He took the arm of the tall brown man and pressed it.

"Thank you, thank you," he said. "I am pleased, of course! Tell me—a courier came yesterday with the sad news about Antony. Tell me—"

He paused as though unable to form the question.

Chandra Ghose nodded. "I was still at Alexandria when it happened, then took a fast boat upriver to join my caravan at Coptos. Yes, he is dead. Why do you call it sad to die? In my country, we know that death is an easy thing; it is birth which is hard. Of course, no one likes to die; but after all, it is a natural, an inevitable thing, a kind thing like Karma."

"What is that? I never heard of it."

"Some call it Fate, though we know it to be far more than fate—not a blind thing, but one of old purpose," said the Hindu. "The will of the gods, which is never blind or meaningless. Destiny were a better word."

"Oh, I understand that, of course!" exclaimed Caesarion. "A kind thing, you say?"

"Precisely, young sir. The Autocrator"—this was the title by which Antony had been known in Egypt—"is dead, and far better so. Is it not better to die at the height of fame, like the Greek hero Achilles, than to live on through old age in shame? Die, face the judgment of the gods, face the future in the other world—why, that's a little thing! A brave thing, perhaps, yet a little thing to us folk of India."

While thus talking, they had come to the house occupied by Rhodon. Caesarion halted.

"Wait, before we go in," he said. "I started to ask you about the queen. She gave you that message?"

"No, it came through one of her faithful women," said Chandra Ghose. He hesitated, then went on: "I understand that she departed by her own choice, rather than face the shame which Octavian destined for her."

"Departed?" Caesarion had turned quickly. "Departed? Oh, surely—"

The dark man nodded. "It is hard to be born; it is easy to die," he repeated.

For one moment Caesarion stood as though paralyzed; then he came to life, and beckoned one of the guards, who approached.

"Take this man to Rhodon," he ordered, then turned and strode away into the house.

It was the bitterest moment of his life. The little queen, his mother, was dead. She had gone, after assuring his safety and future. Those ships in harbor held what treasures of Egypt she could gather for him—everything for him. The little laughing queen whom everyone loved, was gone—gone into the darkness.

He locked himself in his room. The cat Ptah came and sat at his door, unblinking, but no one sought to disturb him. The unexpected sharp news from Alexandria left everyone stupefied. The impossible had happened: Cleopatra the queen, last of the Ptolemy line, was dead.

Rhodon, at first stunned, quickly recovered and kept Chandra Ghose in talk, kept him for the noon meal, kept him afterward, rather drawn to him. A peculiar fellow, this Rhodon, and not a forceful man. He had won many prizes at school, had taken up tutoring, and because of his command of the ancient Greek tongue had been given the post of tutor to Caesarion. He had known the queen very well.

"I think," Chandra Ghose told him, "you'll have a visit from a fellow named Aurone. I don't know if he's a Greek or not, but I fancy he's a rascal; he has a bad reputation. He was with our caravan, and was heartily inquisitive about everyone here at Berenice, asking me if it were true that Caesar's son were here, and so forth. He smells in my nostrils, and I warn you to be careful."

"May the gods repay your kindness!" said Rhodon. "Do you sail with the ships?"

"Certainly not," replied the Hindu. "I put my goods aboard, check everything with my supercargo, and in three days shall return to Coptos, where my boat awaits me for Alexandria. What is that little tiger I saw when I arrived?"

"A cat. These Egyptians worship certain cats at a place called Bubastis. This one is of the sacred breed, and was presented to my pupil there. The animal is furred, and suffers here from the heat."

Chandra Ghose pressed for information about the cat-worship. Rhodon could not give it; he knew almost nothing of the Egyptians or their involved religion. No Greek did. Alexandria, its rulers, its general population, all were pure Greek. The city was cut off from Egypt and had few contacts with the land it ruled...

Late in the afternoon, when the siesta hour had passed, Aurone came to the house and asked for Rhodon. He was confident, assured, rather sly, and frankly stated that he was no Greek but a Cilician. Rhodon disliked and distrusted him at sight.

"What business do you have with me?" he demanded.

"Lord, I need your signature and that of Lord Caesar to a receipt," Aurone responded, with a wink. "It was suspected that you were here. I was sent to give you certain epistles. The receipt must bear your two signatures. The letters are to you both."

Rhodon was startled. Letters? More letters? Did bad news have no end?

"Who sent you?" he inquired.

"My lord, I was not paid to talk, but to deliver the letters, which will speak for themselves. In fact, I saw them written and signed."

"Wait here," said Rhodon. They were in the cool courtyard. "I'll go and find my pupil."

On the way, he found and girded on his sword, a leaf-shaped Egyptian weapon. He was no swordsman, but anyone could use this cruelly efficient blade. He saw Ptah at the door of Caesarion, tail curled about feet, and knocked.

Caesarion opened the door. He was pale; his usually bright and burning eyes were dull and swollen.

"There is a caller, a fellow named Aurone, a Cilician," said Rhodon. "He bears letters but will not deliver them without our signatures. Are you able to come and see him?"

"Able? I'm a man, not a child," said Caesarion calmly. "Letters from whom?"

"The fellow won't say. Chandra Ghose warned me against him; we must have a care. It may be some trick. He may be an assassin, or a spy sent to discover your whereabouts."

Caesarion smiled scornfully. "Poor Rhodon: you look flushed and ill, and no wonder. Don't you think I'm capable of dealing with any Roman agent or assassin? So the trader from India warned you? Good. I like that dark man. He rings true; his one eye has an honest spark of flame in it. Come along, and we'll see this Cilician. Who could be sending us letters, if _she_ is gone?"

Rhodon was startled by the change in the speaker. The boy had become a man; grief had worked a hardening change in him. His voice had firmed and deepened, his manner had become imperious. At the door he stooped and touched the cat Ptah, who rubbed head against his leg.

"Too hot for you here," he said. "I know it. You're another reason."

"Reason?" Rhodon caught at the word. "For what?"

"For what I intend to see you about in the morning, when we've slept over this news. Come along."

Caesarion led the way back to the patio. Rhodon followed, wondering at the change in him. Aurone was sprawled in a chair, lazily. He glanced up at their approach, looking at Caesarion with quick sly gaze.

Caesarion halted. "You are the messenger?" His voice almost crackled. "Do you want a whip over your back to teach you respect, fellow?"

Aurone sprang up and made respectful salute.

"Now hand over the letters, if you bear any," snapped Caesarion. "You shall have your receipt if I choose to give it."

Aurone, looking like a whipped dog, humbly saluted and produced a small scroll. Caesarion took it, saw that it was addressed to himself and Rhodon, and broke the seal that tied it. He opened it and glanced at the Greek writing, looked again, and read it through. Then he handed it to Rhodon and gave his attention to the messenger.

"Where did you get the epistle? Speak fully."

Aurone cringed. "Lord, at the Lochias palace. I was taken there. I saw the letter written. The general sealed it—"

"What general?"

"I do not know. He had the red cloak of a Roman general. They called him Octavian."

Caesarion exchanged a glance with Rhodon. Octavian, or Caesar, would naturally be dwelling in the Lochias palace, that ancient regal palace of the Ptolemies.

Caesarion called a guard, and pointed to Aurone.

"Take this man to a scribe. When he gets his receipt written, bring him back and we will put our seals to it."

AURONE was led away. Rhodon, having read the letter,

turned to Caesarion, his flushed features excited. He did look

ill; fever, perhaps.

"It's from Caesar, yes," he exclaimed. "Yet I can't believe it."

"He calls me Caesar!" broke out Caesarion. "Did you note that? Return in safety, and I can have my heritage—my heritage! It's a safe-conduct, Rhodon! It promises everything I want!"

"Promises are cheap," murmured Rhodon. "Don't believe him. Rather, credit the last message that came: _Trust no one.__ _That way lies safety."

"Safety! Caution! Prudence! Security! By the gods, who wants to live a life of security!" burst forth Caesarion with impetuous force, passion in his face. "Well enough for you—you're a Greek. I'm a Roman, the son of Julius Caesar! Security? Hell take it! Life isn't won by cowards who seek only security—it must be won by overcoming obstacles! It's no end in itself. My mother's dead. I'm my own master now, with my own life to live. I obeyed her. Now I obey my own heart."

"Sleep on it," weakly advised the Greek.

"Right. We'll do that. I want nothing to eat, anyway—I'm off for a walk, then to bed and seek what counsel the gods will send... Oh, here's our man."

Aurone was brought in with his receipt. Rhodon and Caesarion applied their seals to it, and the messenger departed.

So did Caesarion, with the "little tiger" stalking after him, tail a-twitch. He went to the lonely shore and sat there through the twilight, with the cat in his arms—the only thing that loved him now. He sat until the far sea darkened, and the stars twinkled above, and lights sprang in the town; then he rose and went striding up toward the lights and came to where animals and bales of goods stood about campfires while men ate. He looked for the one-eyed man and found him, and came and sat beside him.

"When," he asked, "do you return to Alexandria? Or do you return?"

"Yes. I have a boat waiting at Coptos," said Chandra Ghose. "I leave here in three days. Because of the desert heat, we leave at sunset and travel at night."

"Leave tomorrow night instead. I and my guards go with you. Name any price you desire. It can be done; so do it. We'll need horses."

Chandra Ghose sat motionless. "I have an agent; I can leave things to him, yes. It can be done," he said slowly. "But this letter-carrier saw you only this afternoon. Now you suddenly decide to change plans and go back. I distrust that man; I distrust your wisdom."

"Do you refuse?"

"No. Ask me the same thing in the morning, and I'll agree. In sleep the gods give counsel."

Caesarion understood. The man was a true friend; he wanted only to be certain.

"Thank you." He stood up. "I shall come to you in the morning. You speak truth."

He turned away and went to the house on the high sands. He spoke with one of the guards; Rhodon, he learned, was shaking with fever and shock. He got a lighted lamp, went to his own room, and lighted the larger lamp here. The cat Ptah came in after him and curled up in a chair.

Caesarion sat at the table. He got out the queer emerald with the Sphinx-figure inside it, and placed it under the lamp to catch the full glow of light. From a chest he took a doubly convex glass which enlarged objects, and began to study the emerald through this. He saw, not a little stone he could hold in his palm, but a huge expanse of shimmering green spaces, and his breath began to come faster as he looked.

No hint here of grief. They were dead—his mother and the Autocrator both—but of this nothing came into his brain. An easy thing, death, the Hindu trader had said. In the green depths gathered other senses, waking very different thoughts in him, appealing to different phases of him. He was the son of the divine Julius. Octavian, if made aware that he sought nothing except his heritage from that Julius, could not refuse it; had not the man promised him safe-conduct?

The shameful sense of flight, of hiding, completely left him. In its stead came the grateful idea of dealing with the greatest man in the world, Octavian. This was his right. He was not destined to treat with little people, with lesser men. The son of Caesar must meet with Caesar himself, face to face, as with an equal. There lay justice for one who sought only equity and his Roman heritage. Octavian undoubtedly realized this himself, and in consequence had promised him safety if he returned. The greatest man on earth could not be a cheap and petty rascal!

Thus spake the stone, the glinting depths of beryl, as though the Sphinx within it had found tongue. Caesarion had never felt the power so firmly, so surely; the rush of thoughts swept over him and roused him out of himself. He leaped up and went to Rhodon's room, close by. He saw Rhodon reading by a night lamp, and went to him.

"Not asleep? Feeling better? Good. Do you want to return with me to Alexandria?"

Rhodon laid aside the scroll. "I cannot, my son. My old fever has come back. I'm frightfully weak tonight. Have you decided to go back, despite everything?"

"Because of everything." Caesarion spoke crisply, decisively, yet calmly. "I know now that my mind will be the same tomorrow, Rhodon."

"I can't prevent you or forbid you."

"No. That safe-conduct from Octavian changes all our plans. I'll go to him and see what he has to say. I'll claim my heritage from him. With my little mother dead, I'm the sole King of Egypt. He can have Egypt. I want no more than some little quiet corner of the world, and recognition by Rome as Caesar's son."

"It's not a great thing to ask," Rhodon said. "Yet is it wise? Think of this tonight, my son. Here you have escape assured, immense treasures, a clear future—"

"And shame," said Caesarion, smiling. "A heavy burden to bear! No. I am Caesar, I shall act as Caesar would have acted in my place. Besides, think of Ptah! The poor cat suffers here in this hamlet at the world's edge. I shall take him and leave him at Bubastis, where the Nile tempers the heat."

Rhodon made a helpless gesture.

"She is dead; Antony is dead—does anything matter now?"

"Cheer up! Guard the treasure. If I don't return, take of it what you like, and go whither you like. I leave tomorrow evening with Chandra Ghose. See you tomorrow," said Caesarion cheerfully. "And I'll leave you a gift, old friend. You may not like it, yet it will serve to remind you of me, and of my mother. Good night."

FEVER came back on Rhodon full force that night, and with

morning he was tossing in delirium. With the following morning it

had passed, leaving him clear-headed but quite weak. In the

afternoon the captain of the guards came to him, anxiously.

"Lord, I cannot keep it from you," he said. "Caesarion took Plancus and Caius with him, ordered the rest of us to remain here with you, and departed with that one-eyed trader, the other night. He took the cat with him also."

"Then it cannot be helped," said Rhodon. "But he had a letter from Octavian, promising him safety."

The soldier spat. "A promise from the Executioner is a bag of empty wind. We can still mount and ride after them, if you order it."

"He is Caesar, and King of Egypt," said Rhodon. "Let the gods who caused this happening look to their own work."

Two days later Rhodon was up and around, when one of the guards reported that he had just seen in the village the Cilician, Aurone, who had brought the letters. He summoned the captain to go with him, girt on his sword, and they went into the town. Sure enough, they came upon Aurone at the tavern, deep in wine. Rhodon bared the leaf-shaped sword, and the fellow shrank from him in fear.

"Spare me, lord, spare me!" he cried. "I have repented the ill I did—"

"What ill? Name it." Rhodon spoke coldly. "Was that letter false?"

"I know not," replied Aurone, trembling and spilling his wine. "The Roman general who paid me to bring it—he ordered me to wait here; if the letter brought the boy to him, I would receive double pay. He is—he is sending soldiers—"

Rhodon drew back his sword for the thrust, then checked himself.

"Vile dog that you are," he said, sheathing the weapon, "your death would not undo it. I leave you to the gods and your own sorry conscience."

He beckoned the captain, went out, and covered his face. But the captain, who was a veteran of Caesar's 37th Legion, stepped quickly back into the tavern, and presently returned, wiping his sword. He, at least, indulged no scruples.

OCTAVIAN sending soldiers here? Fear seized the tutor at

this information. He went home sweating. They gave him a little

packet Caesarion had left for him. In his own room, Rhodon

unwrapped it, and the Sphinx emerald fell into his hand. He

looked at it a long while; he was afraid to die. At last he rose,

trembling, filled a purse with money, stole out of the house,

went into the town and secured a horse.

He rode like a madman along the caravan road to Coptos and the Nile.

He rode like a madman along the caravan road.

He reached Coptos, a haggard wreck, and took passage on a boat

bound downstream for Alexandria. He let his beard grow, took

another name, kept to himself. The good river air banished his

illness. He tried to get news of Caesarion, but could learn

nothing at all. In fact, he was almost afraid to ask. He knew

that emissaries of Octavian must even now be seeking him.

At Alexandria he was astounded by the flood of propaganda going around, spread by the Romans. Calumny of every sort was being heaped upon Cleopatra and upon Antony. The good, the virtuous, the noble Octavian was the hope of Egypt, the savior of the world; Augustus, they were already calling him.

Rhodon lingered not. Under his new name he got passage with a caravan bound for Syria. It was leaving on the morrow, And then, as he walked down the great Canopus Avenue that bisected the city like a sword, he came face to face with Chandra Ghose.

Despite the beard, the entire disguise, the one-eyed Hindu knew him instantly, and crooked a finger.

"Come along to my bazaar. There's a huge reward offered for you. With me you're safe."

Rhodon obeyed in miserable terror; his nerves were cracking up. Chandra Ghose sat with him in the cool rear room of the bazaar, dimly lit, and food and wine were brought. They ate and drank; upon Rhodon's lips trembled the one question which had no answer. The Hindu nodded.

"Yes. I know. I witnessed everything. I'll tell you about it."

This is what he told:

Upon reaching Alexandria, Caesarion made no secret of his presence but went straight to the Lochias Palace and demanded audience with Octavian. There was a delay, and finally he was led to the audience hall. Upon the throne at the far end sat a man pallid and spotted of skin, a man who shunned sunlight and cold water alike. He kept his guards close.

A murmur passed through the ranks of soldiers and officers as Caesarion walked toward the throne on the dais, where he himself had sat as King of Egypt. For he held his head high; his eyes were bright and sparkling; there was a slight confident smile upon his lips, and many of those present had intimately known another like him.

"The divine Julius himself!" went the awed whisper.

Octavian also had known that other. As he watched the approaching figure, his cold eyes became touched with fear and his cheeks grew more sallow. He must have known that this was a moment when anything might happen; one word from the boy, and half these Romans would draw sword for him in hysteric ecstasy.

Caesarion halted at the edge of the dais and threw up a hand in salute. There was something gayly boyish about his looks, his words.

"_Ave, Caesar!_" he cried. "I, who am also Caesar, salute you! I have come to accept your promised protection, and to claim my heritage from the divine Julius my father!"

A stillness had settled upon the hall; in it was distinctly heard the uneven, sniffling breath of Octavian as the Roman tried to make reply, and could not. With an effort, his chill voice at last managed slow words.

"It—it is dangerous for two Caesars to be in the world at the same time."

The cold eyes, the cold voice, seemed to shock Caesarion with disillusion. In this instant he must have seen the whole truth. His shoulders squared, his features changed and hardened. He looked at the sallow, pimply man before him. Scorn and contempt glittered in his bright eyes, and bitter understanding.

Octavian, fearing a word too many, crooked a shaky finger at the guards.

"Quickly! Do it now—quickly!" he croaked—and they obeyed him.

THIS was the tale Chandra Ghose told. Rhodon put his

pallid face in his hands, and his shoulders shook as broken words

came to his lips. Then he gulped wine and tried to pull himself

together.

"Let me—let me show you something." He made a pitiful effort to change the subject and tugged at his girdle. "He left it for me—his mother had given it to him. Look."

He brought out the emerald and tumbled it on the table. The one eye of Chandra Ghose swooped upon it. A look, a swift examination...

"By the thunderbolt of Indra!" exclaimed the trader in awe. "This is a wonder of the world! It will make you wealthy—I can give you a huge sum for it—"

Rhodon shivered.

"Be quiet," he said. "I am going to hide myself in Syria. What good is money to me? This is a memory of those whom I loved and served. I do not like it, but I shall cherish it while I live. And when I come to die, perhaps I shall return to Egypt with it."

His words died away. He took back the emerald, wrapped it in its cloth, and put it into his girdle again. He gulped more wine. The tension was broken now, and he began to speak of Caesarion's death. A frightful thing, he said, a sad thing.

"Don't be absurd," struck in Chandra Ghose, almost in contempt. His voice firmed and echoed in the little room. "Nothing of the sort. The boy would have lived amid wars and tumults; he would have suffered spiritually. Our plans are human and fallible; those of Karma have a hidden purpose, one wiser than we realize."

He paused briefly, sipped his wine, then continued in words that Rhodon was to carry with him into Syria and obscurity:

"A sad tale, at first glance. Yet in reality it is one of those things we cannot explain, which work for good in a way we cannot see. There lies the truth."

In later days Rhodon wrote down all these things; but the Romans got wind of the manuscript and destroyed it. So they thought, at least; yet a copy survived.