RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

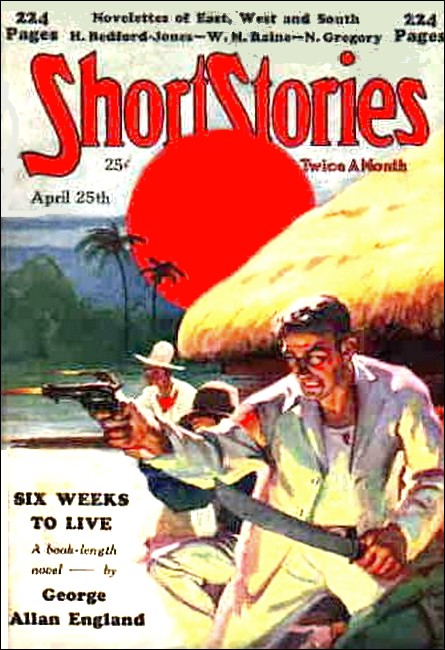

Short Stories, 25 April 1932, with "The King-Makers"

The last of a long line of emperors stages a comeback under Yankee auspices.

CONNOR had dressed for dinner, and was rather impatiently awaiting the return of Stanley. It was nearly eight, and time to dine. From his open window he listened to the occasional outburst of rifle or machine-gun fire, coming from the Japanese settlement. Luxurious as it was, the Tientsin Club was beholding parlous times.

Earl Stanley, the booming, raucous-voiced, energetic lawyer from San Francisco, was one of the few men who knew the truth about Connor.

To Tientsin at large, Connor was merely a pleasant young man who had inherited vast financial interests in China, who played polo, raced horses, spent his money languidly, and on the whole was quite an ass. To a very few on the inside, he was known as an energetic young man who mixed largely in political affairs—not for his own interest, but for the good of China.

Tonight he was worried about Stanley, who had no business running around town by himself; while entirely capable, even to speaking Chinese, Stanley was a stranger in Tientsin and had only recently come on a visit from San Francisco. For Japan had occupied Mukden, was seizing all Manchuria in her grasp, and China was in the throes of wild and ineffectual protest. From the native city, bandits and alleged patriots had flooded into the Japanese quarter of Tientsin to kill and rob. Native mobs were being shot down, and all Tientsin was in alarm and uproar.

The telephone jangled sharply. Connor picked up the instrument, and heard the voice of the missing.

"Connor? Stanley speaking. Say, I'm over in the French settlement, in Rue Favier—a small restaurant called the Rendezvous des Tirailleurs, close to Rue Gros. You can't miss it. Get here quick as a taxi can roll you. Fetch along my traveling cap and a pair of pants."

"Excellent!" Connor chuckled. "Why not a pair of slippers?"

"Hey, this is no joke!" came the response, sharply urgent. "Police been after me yet?"

"No."

"This is something big. Get here on the jump, will you?"

"Sure thing."

"And, say! Bring along some Chinese chap you can trust, will you?"

"Right."

CONNOR got the club desk on the wire and found that his

car and chauffeur were on hand. Catching up Stanley's cap and an

odd pair of trousers, he rolled them up hastily, left his room,

and two minutes later was stepping into his car beside the

driver, a rotund little Szechuan man named Wang, who was

absolutely devoted to him.

He was soon rolling down Victoria Road toward the French settlement. A far, thin sound of rifle-fire came from the Japanese quarter ahead, then was hushed. Connor knew that Stanley must be in some sort of a mess, which was nothing new. Since his arrival in China, Earl Stanley had been thrusting his eager head into all kinds of trouble, from which he seemed to emerge by a miracle without great damage.

The police, Connor noted, were out full force, and files of troops were marching through the streets. There was no danger outside of the Japanese quarter, however. The car swung down Hsinyuen Road and angled off through the French settlement to its destination, which was a small, very ordinary, none too high grade restaurant. Telling Wang to park the car and follow him, Connor strode in.

A few people were in evidence. There was no sign of Stanley in sight. The proprietor came up, rubbing his hands, and Connor asked a question. The Frenchman opened his eyes wide.

"Ah! It is M'sieu Connor! Come with me, m'sieu. In the private room off the balcony. Your friend is discussing business. There is some excellent Vouvray, m'sieu, actually of the '21 vintage! And dinner has been awaiting your arrival."

"Serve it, then," said Connor curtly. Wang followed him, and the French, who never ask questions and are surprised at nothing, paid no heed.

From a small balcony at the rear, opened a private room of some size. The proprietor knocked and flung open the door with a flourish. Connor stepped in. Wang followed him and closed the door. Then, after one slack-jawed stare of utter astonishment the chubby Wang slipped down on his knees, put his palms on the floor, and bowed his head between them.

Connor saw the action, but failed to comprehend it for a moment. He looked at Stanley, brawny, breezy, in great good humor, who was talking with a native; a young Chinese who wore black-rimmed spectacles, his features rather weak. He was oddly attired in a heavy sweater pulled over a native robe. Something vaguely familiar about his face struck Connor, but he could not place the man.

"Hello! Attaboy! Good work!" Stanley leaped to his feet with a sudden laugh. "So you don't recognize my pal, eh? He understands English but prefers Mandarin. Don't know him?"

The native met Connor's frowning gaze, and smiled.

"When we last met," he said in purest Mandarin, "I was not wearing these clothes."

"Good lord!" exclaimed Connor in amazement. Then he bowed. "A surprise indeed, your—"

"Shut up! Sit down!" barked Stanley. "Wang, you fool, get up! Connor, we're all in one hell of a fix. So is Henry, here. Call him Henry, for the love of mike! Here's the waiter."

Not one waiter, but two, who brought an excellent meal and with it a couple of bottles of Vouvray. Connor lit a cigarette and appeared at his ease. Wang stood stiffly in one corner, a trace of fear in his eyes. Stanley spoke in rapid English, using as much slang as possible; he knew that Frenchmen never speak English but always understand it.

"You're wise now, are you? All right. I met up with this bird a few blocks away, at the edge of the Jap quarter. Hell of a fuss going on over there, a lot of shooting. This gazebo was looking pretty dazed. No one about, luckily. Come to find out, he'd had a row with the little brown brothers. Don't know why as yet. Some sons of T'ang had shown up with bombs, too. He's got a bullet- hole in his coat and was scared stiff. I bet the Japs are moving heaven and earth right now to find him, too. His establishment was in their settlement, you know."

Connor nodded. "Why did you speak of the police?"

"Well, a Jap officer came along. This guy started to run and the Jap got nasty, so I pasted him good and hard. They'll get me by the description, sooner or later. I shoved this bird along and landed him here. Safe enough. Didn't dare go anywhere else."

CONNOR'S keen, tensed features were immobile, but he said

nothing until the waiters had departed.

He needed those few moment to recover from the abrupt shock. He was inwardly stunned, incredulous, doubting his own senses. This young native in the sweater and spectacles was Henry Chang- yin. He was the last of the line of the great Nurhachu, founder of the Manchu empire, and the throne of the Yellow Dragon was his by rights.

Exiled like the other Manchu princes, Hsuan, as he was usually termed, had lived in retirement in the Japanese settlement, supported by the Japanese. He was a quiet sort, without great force, educated by English tutors. The sons of T'ang, the republican Chinese of the north, hated and feared him as being the rightful emperor, a pawn waiting in the hand of Japan.

All this leaped across Connor's mind in a flash, all this and more. With an effort, however, he kept himself under control. Like a man who has found some great pearl in the gutter, he feared for an instant lest destiny were mocking him. Then, like a flash of fire speeding through his veins, he accepted the sudden swift gamble. He saw a dozen things he could do, great things, daring things. Here in his hand, for his own use—if he could hold it—was the pawn whose move could shake the entire Oriental world.

The door closed, the waiters ware gone. Connor drew a deep breath and gave Stanley a look.

"I understand about the coat and pants now. Well, who's running the show?"

"What d'you mean?" demanded Stanley, his wide, forceful features wrinkled up in a frown. "What show?"

"This," said Connor. "All of it. You and I can't both run it. We have different notions."

Before the lawyer could reply, Hsuan leaned forward, gravely.

"My friends, I am hungry. Abandon formality and let us eat," he said. "From this moment I become Henry, nothing else. Who is this son of Han? Let him sit with us."

This was shrewd enough, as Connor realized. Wang was indeed a son of Han, a Chinese of the south. This Henry was no fool, then!

The alert and hungry emperor who had no throne, insisted that they pitch into the meal, and himself set the example. Connor soon understood that he was suspicious of everything around him, and quite timid. Between bites, he spoke freely, and in naive fashion laid before them a singular and alarming situation. Connor, whose brain was already driving far out and around, probing a dozen possibilities, began to feel his head very loose on his shoulders. Stanley had picked up a whole package of dynamite, which might send them all up together at any moment.

"My friends," said the spectacled native, "the Japanese are determined to take me to Manchuria. They want to make me emperor in Mukden, to rule for them. I do not wish it. I am comfortable, happy, peaceful. They threatened, bribed, tempted me to go. When the chance came tonight, I ran away.

"But now, what? I have nowhere to go. I can trust nobody at all. Can I trust you? I do not know. Everybody I trusted has betrayed me. Tonight the Chinese came to kill me. I have no money. I have nothing. I am not safe anywhere. The only man I could trust absolutely is old Jung Tien, the former mandarin, who keeps a shop in the native city. He has a few former red bannermen of his own clan, who would serve me faithfully. But how can I reach them? I do not know my way. I am helpless."

Indeed, the man was pitifully helpless. He was caught in the net of destiny. This last of a great and able line was terrified by the very thought of becoming a puppet emperor in the city that had produced his ancestors.

THE Manchurian bannermen throughout China, exclusively

warriors in the days of the empire, had been dispersed or

slaughtered when the empire was overthrown. He had no party, no

backing. He had behind him only the loyalty of a few scattered

men. He could trust no one, and he had no future.

Having said all he had to say, having spoken out his feeble soul, he ate and drank avidly. Stanley leaned forward and put his hand on Connor's arm, his brown, vigorous features all alight, his voice lowered.

"Connor, I see what you mean about running the show. Well, you are! It's your party. You do whatever seems best to you, and count on me to stand by."

For an instant Connor's quick, warm smile flashed out, then was gone again. Excitement was rising high within him. Here was indeed something to fire his imagination! And, his hunger somewhat appeased, he began to speak.

He had not touched the wine, yet he was stirred out of himself, lifted to far heights. The greenish-gold wine was, however, quite extraordinary. As Stanley observed, only vintners could tell why the best Vouvray is frequently found in the worst restaurants. Henry partook of it freely, and his dull eyes brightened, and animation crept into his cheeks.

"Let's look at the situation sensibly," said Connor, with easy familiarity. "You say you've no money, Henry? I thought the Chinese government had been paying you half a million dollars a year?"

"That was the agreement, but they paid nothing," said Henry. "The Japanese have paid for everything."

"Oh!" said Stanley. "Then, in that case, I should think—"

Connor kicked him under the table, and he subsided.

"Don't think, Stanley. Now, what's the situation in the north? Japan wants Manchuria and practically has it. The League of Nations will flutter like a lot of old women. Japan will nominally back down, but will leave Manchuria in the hands of her own puppets. That is, unless actual war ensues. Anything's possible. Japan will set up a new government in Manchuria. The Chinese won't dare fight, for their whole government has gone smash. So Japan wins—except for the three of us sitting here! She ought to win, too. The Chinese cannot govern themselves. Now, listen to me, Henry! If you say the word, we'll go!"

The keen eyes of Connor were narrowed, alight, dancing eagerly. Stanley watched them with delight, perhaps guessing what thoughts were racing through the agile brain.

"Where will we go?" asked Henry, blinking.

"To glory or the devil!" and Connor laughed. "What do you care? You're the last of the Tsing dynasty, who came out of Mukden and carved themselves an empire. Half of China is republican and hates you, the other half wants a man, a leader, a name, and will erupt like a volcano if he appears. You are the volcano, Henry!

"Appear suddenly in Manchuria, alone, with no Jap backing. Proclaim yourself, and what happens? Thousands of men will join you overnight. There'll be a storm of men in the north, such as hasn't been seen since Nurhachu threw his horde over the Great Wall! You've nothing to lose, everything to win. We'll get you into Manchuria—"

"How?" asked Henry. A touch of color had risen in his face. He reached for the Vouvray and refilled his glass. "Not by train. That's impossible. And—"

"By ship, of course. Leave that to me." Connor brushed aside the query. "General Ma and whatever is left of the army up there, will gather behind you like a shot. The Japs have broken him now; he'll do anything to save face!"

"But we happen to be in Tientsin," put in Stanley. "And no use blinking it—the Jap secret service is a wow! They won't lose any time picking up Henry's trail. That's why I told you to bring a native with you. You take Henry off, leave your friend Wang—he'll pose as the native who came here with me. Get the idea?"

Connor nodded. "Right. Henry, get into those pants. Give Wang your spectacles."

"I can't see without them!" exclaimed the Manchu plaintively.

"You don't need to see. You'll come with me. Stanley, if the Japs do run you down, face it out. Wang is a splendid liar. He's the chap you met, and so forth. Cover up. Get me?"

"Right." Stanley nodded coolly. "And where'll you be?"

"Getting backing. Money, men, supplies." Connor swung about to the Manchu, who was climbing into the trousers. He abandoned his jocular manner and swung into grave, sonorous Mandarin. "Your Majesty! Great Maternal Ancestor! Do you agree! If you say the word, we'll carry you to a throne in Manchuria, the throne of your ancestors—and you'll stand for yourself!"

"What will you get out of it?" asked Henry, reaching for his wine-glass. Connor laughed.

"Nothing. A timber concession, perhaps, if you must give me something."

"Agreed!" Henry straightened up before them. Sudden enthusiasm shook the slight, irresolute figure. The loose mouth tightened, a flash leaped in the dark eyes. "Agreed! Not a puppet, but a real ruler? Agreed! Yes! The lowered flag will go up again. The Manchus will have an emperor. It is agreed! I have heard of you. They say you are honest. I will do what you say!"

Connor lifted his untouched glass.

"Agreed, then. To Hsuan, emperor of Manchuria, ruler of the Manchus!" His voice chimed on the room like a bronze bell. There was a click of clinking glasses, then Connor flung his own against the wall and came to his feet with the crash.

"Ready? Henry, come along with me. Back at the Tientsin Club in an hour, Stanley."

"Maybe." Stanley burst into his booming laugh. "So long! See you in jail!"

THE Chinese city was seething. Students were parading, anti-Japanese mobs were in full swing, orators spouted on every street-corner. Massacre and death were in the air, and all ears listened for further grim drumming of machine-guns from the Japanese settlement.

No one heeded Henry, in slouchy European garb like thousands of others, a cap pulled over his eyes. Connor had left his car, and now piloted the confused Manchu on foot, into the great thoroughfare called Pei-ma-lu. In this street was the shop of Jung Tien, who sold brocades, silks and other materials for ladies' shoes. Henry, who had seldom left his own residential grounds, knew only vaguely where the shop might be.

Fortunately, Connor was quite at home in the bewildering array of medieval signs hanging out before the shops. Presently he saw the oblong vermilion cloth hanging from a yellow bar, that betokened Jung Tien's trade, and on nearing the shop in question, found that eminently Manchu name inscribed beside the door. Like most of those in the street, the shop was open for tourist business, and Connor walked in with his companion.

"I seek the honorable Jung Tien," he said to the shopman who approached. "Henry, remain here and look at materials."

Five minutes later, Connor stood in the rear room. With him was a vigorous, hearty man of seventy years, who had taken one peep out into the shop and then gone ashen gray.

"No time to explain," said Connor. "Can he remain with you for a day, undetected by those who seek him?"

"Yes, of course," stammered old Jung. "The son of heaven—"

"His name is Henry, and he is a student. Tomorrow night we depart for Manchuria. There the emperor Hsuan proclaims himself—if he's not found first. Half a dozen Manchu bannermen to accompany him. Can do?"

The old eyes flashed. "Yes! My grandson Jung Toy will lead them."

"Once there, can men and money be expected?"

"Men? Of course. Money? Yes." Jung eyed him keenly. "I have heard of you. Men say you are a superior man. Hm! Five million China dollars when you reach Manchuria; they are ready now for delivery. Another ten million, as soon as it can be rushed from various cities. Say, ten days."

"Enough," said Connor, with a nod of satisfaction. "The dynasty of Tsing still has faithful supporters, I see! I will send you word where to bring him tomorrow evening."

"How shall I know if the word comes from you?"

Connor laughed. "The messenger will bear Henry's spectacles as a token."

HE left the shop, giving Henry a clap on the shoulder in

passing, and so passed out into the street again. His whirlwind

visit must have left old Jung Tien in a morass of incredulity;

but the old ex-mandarin had spoken up like a man. No doubt some

Manchu organization existed, some means of raising men and money

quickly if there was any chance of another Tsing reaching a

throne.

And meantime, Henry was safely bestowed, with the most faithful of men around him.

Connor caught a tram and headed back for Victoria Road. His first exultation, his wild and fanciful concept, had taken solid form. Now he had realities to face. He saw that getting Henry out of Tientsin by rail was an impossibility, for the Japanese controlled the railroads. The roads at this season were impassable for cars. There remained only the sea route, safest and quickest—even air was out of the question.

"And everything going down the Peiho River will be watched alow and aloft!" thought Connor. "Most of the Manchurian trade is controlled by the Japanese. Hm!"

The more he fronted it, the more acute grew the problem. Getting away by rail or air could be managed, but reaching the other end was the ticklish part. Remained the sea, involving a trip down-river to the Taku anchorage, with Japanese warships, troop ships and spies on every hand. Spies formed the chief obstacle, for they were legion. Not Japanese alone, but Chinese, Koreans, Russians and others. Connor's problem was not in getting away, which might be managed, but in getting away to a particular destination. The obstacles were insuperable. The more he thought about it, the more he realized this.

He walked into the club, found no trace of Stanley, and went on up to his room.

Lighting a cigarette, he smoked it out in vain thought. There were many things he might attempt; the devil of it was, he could not afford to fail! There would be no second chance. He had to win through or go under.

Connor came suddenly to his feet. At this moment the door was flung open to admit Stanley, with Wang at his heels.

"I've got it!" exclaimed Connor excitedly. Stanley slammed the door.

"You have, by gad! They're on to us. You weren't gone five minutes before they showed up. Chap named Honzai, colonel on the general staff. He made me sweat, let me tell you! Connor, how far can these fellows go, anyhow? It's got me worried!"

Connor chuckled. "No doubt. And you're right. What happened?"

"Oh, I bluffed. They're on, but they can't prove anything. They'll be here any minute. I imagine they're getting British law behind 'em."

"Good!" exclaimed Connor. "Wang, clear out, quick! Now, Stanley, when Honzai gets here, let me do the talking. You'll back me up in anything?"

"You bet!" boomed Stanley. "With me at your back, shoot the works!"

So it was agreed.

BEING in a club, and also in the British settlement,

everything was managed very deftly and without commotion. It

might have been a party of old friends to whom Connor opened his

door. Colonel Honzai was a lean, trim, efficient man of

indeterminate age, whose eyes were very alert behind his

spectacles. Whatever were his intentions in bringing two aides

and a pair of English inspectors, he stifled them on being warmly

welcomed by Connor. He promptly agreed to a private conference,

and his party passed into the adjoining room, occupied by

Stanley, The latter closed the door and rejoined Connor and the

Japanese colonel.

"I know why you're here, of course," said Connor cheerfully. "You're after Henry, eh?"

Colonel Honzai blinked. "You do not evade, sir?"

"Of course not!" exclaimed Connor. "My friend Stanley, here, is quite out of it. You want Henry, and I've got him. And I'm the only one who knows just where Henry is."

"This," said the colonel stiffly, "is not the way to speak of imperial majesty. Respect—"

"Respect be hanged! He's a weak-kneed young man, and between you and me, he's scared stiff," said Connor, with an air of confidential frankness. "I promised to help him get away from Tientsin, and I shall keep my promise."

"Yes?" said Honzai quietly. "I have heard of you, Mr. Connor. I have even suspected that you might not be exactly what you appear on the surface—"

"Correct! None of us is," cut in Connor amiably. "Well, I'm going to help Henry get away, so that's settled. He's not paying me for it, either. If you interfere, you'd not find him at all. That would be rather silly, wouldn't it? It would be much better policy," he added thoughtfully, "if you were to help me get him away."

Colonel Honzai regarded him steadily for a moment.

"Oh! And where does he desire to go?"

"Anywhere, no matter," said Connor carelessly. "Now, if we were to take him aboard a ship and put out to sea, the outcome would be simple. That is, if it were worth our while."

Colonel Honzai suddenly brightened. "Ah! You would discuss finances?"

"Exactly."

For a moment Colonel Honzai remained silent, but the light in his eyes betrayed inward excitement. Abruptly, he came to his feet.

"You will excuse me for one half-hour? I am a very humble cog in the machine. I shall return, with your permission, and continue the discussion."

"By all means," said Connor cordially. "But, my dear sir, bear just one thing in mind! It is not every day that one catches an emperor. You comprehend?"

White teeth flashed beneath the stubby mustache, and the officer bowed.

"Nippon is not stingy, gentlemen. Good-by for the present."

He gathered up his entire escort and departed. When the door closed behind them, Stanley held a match to his pipe. Over the flame, his eyes drove out at Connor.

"You seem amused."

"I am!" and Connor laughed exultantly, his eyes very eager. "That chap is quivering all over this minute! I fitted things right into his plans! They could ask nothing better than to get Henry away from here quietly, without a fuss, in secret. The news will go out later that he's at sea, bound across the gulf for Dairen and the Manchurian throne! Beautiful! Too late for objections, too late for anything!"

"Hm!" said Stanley drily. "Well, I said it was your show, and I'll back it, sweet or bitter. Everybody else has been selling out that poor devil, so we might as well get our share."

An expression of the utmost amazement leaped into Connor's face. He saw that Stanley was entirely serious.

"Indeed?" he said. "You've no compunction about it, I hope?"

"I'm not letting you down," said Stanley. "I don't like it a damned bit, but I'll not go back on my word. It's the only thing to do, I suppose."

"Absolutely. They'll supply us with some sort of craft. We put to sea with him. A destroyer overhauls us and takes him off—giving us gold in exchange. It's simple."

"Very," said Stanley, with a grimace. "I knew you'd do the one thing that nobody else would dream of doing! Well, I'm going downstairs and write a letter or two."

"Do. Come back when Honzai shows up."

STANLEY departed. Connor broke into swift laughter, settled

down in a chair, and got out his pipe. Wang sidled into the room

and departed again at a gesture. Connor was puffing away

complacently at his pipe when Stanley returned, bringing Colonel

Honzai with him. The latter bowed and accepted the chair Connor

offered.

"I can make an offer," he said abruptly, bluntly. "Ten thousand."

"Agreed!" exclaimed Connor warmly. "Ten thousand English pounds—"

"No, no! Wait!" broke in the other with marked agitation. "You mistake! Ten thousand China dollars, is the very top sum I can—"

"Then go back and talk again." Connor leaned back in his chair. "I meant to ask fifty thousand gold dollars, American dollars! The price is now sixty thousand. Within five minutes it becomes seventy-five thousand." He smiled at the staring officer, quite calmly. "There will be no argument, no bartering. You may accept my terms, or adopt your own course. Henry is in Chinese hands, well beyond your reach, and unless I get him away he will probably be killed. I can save him. You cannot. Perhaps you prefer to have him dead?"

Colonel Honzai was more than perturbed. He was stirred to the very bottom of his emperor-adoring soul. Puppet or not, Hsuan was a potential emperor, and he said as much. It was obvious that he did not want the Manchu dead. The pawn on the board was of supreme importance.

"Yet you cannot be in earnest!" he went on, blinking rapidly. "Such a sum—"

"Manchuria is worth it. You want to put him on the throne, don't you?"

"We did yes. What is now planned, I do not know. You will be arrested, you will be—"

"Which won't help you one bit," said Connor. "Sixty thousand. Half in advance. The remainder on delivery. In three minutes the price goes up. Yes or no?"

"Yes. Yes!" The other gulped hard. "You have a plan?"

"Of course. So have you. Thirty thousand tomorrow morning, delivered here. Agreed?"

Colonel Honzai accepted a cigarette.

"Agreed. Then what is your plan?"

"That you provide a small craft with a Chinese crew you can trust. At the Taku anchorage, any time after dark tomorrow evening," said Connor coolly. "We'll come aboard in the course of the evening and sail about midnight. By morning, we'll be at sea, bound south. Your captain may decide upon a course with you. One of your destroyers or other craft can meet us in the morning, and we shall be helpless to resist."

Colonel Honzai relaxed in his chair, and positively beamed on Connor and Stanley.

"Much as I had planned it myself!" he approved. "We must not arouse his suspicions, of course. English officers—hm! Yes, I can arrange that. There is a steam-yacht now available to us at Taku, the Hokko Naiban. How will you get down to her?"

"Railroad down to Tangku," said Connor promptly, "then take a launch out to the anchorage off Taku. What assurance have I that we'll not be molested on the way?"

"You may feel safe," was the reply. "We desire no excitement, no commotion. You, sir, are a very astute gentleman. You will understand."

Connor smiled. "It is a pleasure to do business with you, colonel."

The other rose and bowed. "Tomorrow morning you will receive the stipulated sum, also exact information as to reaching the Hokko Naiban. That is all? Good night."

Colonel Honzai took his departure, trim and efficient. When he was gone, Connor swung around to Stanley, his eyes blazing with exultation.

"Done!" he exclaimed vibrantly. "Thirty thousand in gold! Can you beat it?"

"Yes, blast you!" said the lawyer bluntly. "With thirty pieces of silver!"

Connor burst into a laugh and caught Stanley in his arms, shaking him.

"Stanley, old chap—and you'd still stick by me! Bully for you! And there's thirty thousand for the emperor's war-fund, a fast boat to get away on, the little brown brothers working hard for us—and won't they be hopping mad when they wake up, eh? Get the point now, do you?"

CONNOR had few preparations to make, and no one he dared trust.

A messenger arrived at the club next morning with a large packet of bank-notes and word that the launch of the Hokko Naiban would be waiting at the Tangku railroad station wharf from eight o'clock until twelve that night, with Captain Farson in command.

Wang, bearing the emperor's spectacles, was sent to the shop of Jung Tien, carrying most of the bank-notes as a contribution to the Manchu's war-chest, and very explicit instructions for Jung Toy—the Talented Jung. Stanley, who was new to China but who had all sorts of legal and illegal friends in shipping circles, was sent after certain essential information. Connor, aware that he was undoubtedly being shadowed, left the club with an air of hurried importance and went to the park, where he sat on a bench for an hour or more, reading the papers.

He returned to his room at the club to find Wang just back. All was well, and the orders would be followed to the letter. Ten minutes later, Earl Stanley showed up, vigorous and breezy and self-confident as ever, thoroughly enjoying his risky intrigue.

"This Farson is a fairly bad egg," he reported. "He was let out by the Burns Philp people a couple of years back. Has been running a China coaster ever since, and last year shifted to a Jap line. An Englishman doesn't go to work for Orientals unless he's pretty far down, as a rule. This yacht in question is a good craft. Belonged to some wealthy Jap who died here two or three months ago, but she's old and out of date. Has been for sale cheap. Suit you?"

"Fine," said Connor. "You're a good investigator. The club is getting us a compartment and four tickets to Tangku this evening. We get there at eight-thirty. If Jung Toy does his part, everything's jake."

"Suppose we get double-crossed?"

"How?"

"I dunno, feller." Stanley grinned. "If this was San Francisco, I could tell you. They might figure we'd double-cross them, and beat us to it."

"Possibly. God gave us brains to meet emergencies, but not enough to foretell the future."

SHORTLY after dark that evening the three of them piled out of

a taxicab at the East Station and drew a little apart from the

milling throng. They were presently joined by a tall, lean Manchu

of forty years, and his servant. Jung Toy exchanged a few words

with Connor, then turned away and departed. The servant remained

and accompanied them to their compartment, where, with a sign of

relief, he donned his black-rimmed spectacles and peered

around.

"Are we safe?" he asked. Stanley clapped him on the back.

"As safe as we are, or safer, so cheer up! With us behind you, my boy, your future is assured. Connor is a quiet chap and doesn't expand in true American fashion, but yours truly has no false modesty. We're off on the big play, and we'll push you over or go bust!"

Henry had no more to say during the twenty-seven miles to Tangku Station.

While Connor might have avoided the various changes by having the yacht come upriver to the French settlement wharf, his general scheme would thereby have incurred distinct peril. Until they reached the Taku anchorage off the river mouth. Captain Farson would undoubtedly remain in touch with Honzai's agents.

Both Connor and Stanley were well aware that, even if their entire program succeeded, the future was uncertain. Proclamation of Emperor Hsuan was one thing, establishing him in power would be something else again. To this, Stanley was supremely indifferent, being all set for a splendid and glorious adventure, bubbling over with enthusiasm. Connor's thought was all for the ulterior consequences. He had private information that the entire Chinese government meant to resign. China was in the most complete chaos, and if Manchuria suddenly proclaimed an emperor, the last of the Tsing dynasty, anything would be possible.

"Can't say I think much of our emperor," observed Stanley, as he and Connor went into the passage for a smoke and a breath of air. "You confounded Irish have always picked magnificent morons to follow, from the Stuarts on down the line. However, I suppose it doesn't matter."

"This chap may show up better," said Connor thoughtfully. "Blood will tell, you know. Give this poor devil a chance, and I believe he'll surprise us all."

He was to remember these words later, in a bitter moment.

AT Tangku Station, they found Captain Farson—a saturnine

gentleman with a heavy jaw, who introduced himself, shook hands,

and brought up porters. Henry was entirely ignored. At the wharf

was a large river-launch hired for the occasion, as Farson

explained, and with no delay they were off and chugging down

toward Taku and the marshlands. Connor remained on deck with

Farson, the others going into the cabin.

"You're fully acquainted with this business, Cap'n?" asked Connor.

"Aye." Farson chuckled. "Rather neat, I call it."

"So I think. You'll sail as soon as we're aboard?"

"Aye. It'll take us two hours to reach the yacht."

"Then I'll get a bit of sleep."

The time dragged. It was close to eleven when the lights of Taku appeared, and a bitter cold night it was; in another three weeks the river would be frozen over for the winter. The lights of several steamers showed across the bar. The launch headed straight for the outermost light, and upon drawing near, Connor perceived that the yacht was no large one. The gangway was out, lights showed.

Chinese seamen and two other white officers waited at the head of the ladder. Galloway, the chief engineer, was a burly man with a black eye and cut-up face, smelling far and wide of rum. Hawkins, first officer, a small man, was mild of feature, apologetic of manner.

"We'll get under way at once," said Farson, after performing the introductions. "Mr. Hawkins, be good enough to show our friends to their cabins."

He started for the ladder. Connor followed him.

"I'll just come along, Cap'n. Want a word with you, if you don't mind."

Farson waited on the bridge, obviously none too well pleased.

"Something I forgot to tell you," said Connor cheerfully. "This chap we're taking off sent a couple of his wives and their servants by launch, down-river from the city. They'll be along at any moment, so we'd better wait."

"Wives!" and Farson snorted. "Man, we want no yellow women aboard!"

"You can't help it," said Connor. "He said they'd be dressed as men, anyhow. It won't hurt to humor him a bit."

Farson gave grudging assent, and called down to leave the gangway as it was.

"Sailing on short notice," he said, "and haven't got the craft shipshape, but the cabins are in fair condition."

"You're cleared for Shanghai?"

Farson hesitated. "No, for Dairen."

Connor shrugged and made no comment. The figure of Stanley appeared on the ladder. Connor, under the overhead light, beckoned him.

"We're double-crossed," he said softly. "As soon as they're aboard and we get under way, cut loose! They'll probably be good and seasick after an hour of this swell—we'll have to act at once. I'll handle the bridge, here. You attend to Hawkins, then take over the engine-room. Tell Wang to sweep the decks with the Manchus, clap every man into the forecastle. Get me?"

"You bet," assented Stanley. "What's up?"

"Don't know yet. Here he comes. Well, how's our friend below?"

"Groaning already," and Stanley chuckled as the captain joined them. "The river-swell finished him. He's turned in, and he'll stay put. Steam up, Cap'n?"

"Aye. Damn the delay! Steward's fetching us up some hot coffee, gentlemen. Better step inside and be comfortable."

They followed him into the pilot-house, where a small table was spread. After a moment Hawkins appeared, was told of the delay, and offered no comment. The yellow steward came with a tray and set out sandwiches and coffee.

Connor knew that if the river-trip had made Jung Toy and his men seasick, as was not unlikely, the game was lost.

THE waiting was interminable. Farson's dark eyes studied his

two passengers alertly, as though he were sizing them up,

preparing for something he knew was coming. Connor understood

those glances perfectly, and deliberately put on his gayest and

most reckless air.

At length a hail came from the lookout forward. At the bridge rail, Connor looked down as the shape of a launch swept in under the ladder. His voice bit out, and that of Jung Toy made brief answer. He turned to Farson, as Stanley went on down the ladder to meet the arrivals.

"It's our crowd. You're all clear now."

"And high time," said the skipper. "Mr. Hawkins! Take that crowd down and let 'em bunk with their boss or where they like. Then get our hook up and we'll go."

Shrill Chinese voices sounded, a whistle shrilled, the rattle and bang of steam winches echoed across the rolling waters.

Ten minutes later, Connor sat in the bridge house. Farson stood watching the hooded binnacle as the engines sent the Hokko Naiban swirling out to sea and the lights behind dropped into the distance. At the steam steering gear stood a Chinese seaman.

"Steady as she goes," ordered Farson, and turned with a sigh of relief. "Well, we're off! You'll not mind a trip to Dairen and back, Mr. Connor?"

"Not in the least," said the latter carelessly. "You don't mean that we're going there?"

"Aye. The plans were changed. Instead of a ship meeting us—what's that?"

From somewhere forward a shrill, high voice shrieked in the night. Connor's hand slipped out his pistol.

"Turn your back," crackled his voice. "Put 'em up—stand quiet!"

THE ship was taken. The capture was rapid, if not painless. Galloway looked into Stanley's pistol and submitted like a lamb. Surprisingly enough, the only officer to show fight was little Hawkins, who knocked up Stanley's weapon and drove in like a game-cock. Stanley laughed, knocked him sprawling, and locked him into his own cabin. The steward also put up a battle, firing a fruitless shot at Wang, who promptly knifed him. That was the only shot fired. The eight men in the crew, caught completely by surprise, were rounded up forward and the hood of the forecastle was locked upon them, together with the off watch of the black gang.

Captain Farson remained on the bridge. Jung Toy took up his post in the engine-room, while Stanley mounted to the bridge to report, with Wang trailing him.

"Officers all had gats," said Stanley, "Extra guns in their cabins, too. Our crowd is well armed now."

"Japanese pistols, eh?" said Connor, examining one of the weapons. Captain Farson glowered at them, a flame in his black eyes, danger in his dark features.

"You'll all sweat for this! It's piracy, that's what!"

"True," said Connor. "You're excused, Skipper. Wang, take him below and lock him in his cabin. Watch your step, Farson, for Wang is rather expert with a knife. So long."

They departed. Secure in the knowledge that everyone aboard, except the men feeding the fires, was safely locked up, Connor took up the chart which the skipper had been using, and Stanley peered over his shoulder.

"About a day's run across to Dairen, eh?" said Connor. "They figured it was no use having another craft meet us; that Farson could run over there and land our Manchu friend. Instead, we'll run up north to the head of the gulf, and land there at any fishing village. Then straight over the hills, across the railroad, and the job's done."

"You're far from Mukden, aren't you?" asked Stanley.

"Sure. We need to be, for the Japs are there. Once in the hills, we'll proclaim him and the rest will be like a rolling snowball. Stanley, we've done it! We're headed north now, and this time tomorrow night we'll be somewhere in Manchuria. Congratulations all round!"

"Huh! You've handled it well," and Stanley chuckled. "We ought to haul Henry out and have a celebration, but he's sick. Since the course changed, she's quit rolling. He'll probably be up and around by morning. What's the program? Details, I mean."

"Hm! It's midnight now," said Connor. "We have only to keep heading north; nothing in the way. I'll put Wang at the helm, and the Manchus on guard. You and I grab off some sleep, for we'll be needing it by tomorrow night, when the real work begins."

CONNOR was emphatically no seaman, and neither was Stanley. To

both of them it appeared that a fairly sensible chap like Wang

could keep the yacht headed into the north, especially as he had

only to set the steam steering gear and leave it alone. It never

occurred to either of them that such things as currents, leeway,

and the curiosity of a Chinaman to see how mechanical

contraptions worked, might affect their plans.

Thus it happened that the Hokko Naiban went tearing full speed ahead under the cold stars, straight up the gulf of Liao-tung, hour after hour. Half a dozen Manchus prowled about her decks or hung over her rail, unhappy men. Her officers were locked up. Little Wang had his sweet will with the steam steering gear. Down below, Jung Toy grimly held the luckless stokers at work, poised on the gratings above them like a lean dark fiend in hell.

By grace of the Manchu gods, no lumbering junk was encountered that night. But when Wang sent a hurried summons for Connor at sunrise, imminent disaster threatened. The yacht was a scant two miles off shore, the mountains piling up to port in the sunrise glory, and she was yawing back and forth as Wang tried the lever at different points on the slide. To the northeast was a trail of black smoke lifting against the sunrise sky.

Connor dashed for the bridge, cursed the sleepy Wang and sent him below. A moment later the yacht swung and held steadily, a little off shore. They were nowhere near the head of the gulf, but undoubtedly well past Chinchow and the end of the Great Wall, so that the mountains rising to the left were certainly Manchurian soil.

Stanley, yawning, appeared on the starboard ladder. Connor was calling to him, when he stiffened abruptly. From somewhere below lifted the sharp explosion of a pistol.

"Engine-room on the jump, Stanley!" exclaimed Connor. "That's vital. Whatever happens, keep control there. I'll see to things here."

Stanley disappeared. Connor jumped for the port ladder and slid down. As he struck the deck, Wang appeared before him, his long knife running blood.

"Quick, master!" broke out his panting cry. "The captain smashed his door and got out. He ran aft. There was a Japanese soldier with him, who shot one of our men. I got him—"

"A Japanese! Are you sure?"

Wang pointed down the passage. "There is his body."

Connor broke aft at a run. He nearly stumbled over the body of a Japanese officer in uniform. Impossible as it seemed, it was true. Something of the explanation flashed over him in this ghastly instant. Farson had broken out. Somewhere aboard there must have been Japanese in hiding—and Farson had gone aft! Another shot and another rang out.

Connor came to an abrupt halt as he cleared the superstructure. Before him lay the after-deck, and at the companion-way he saw two of his Manchus. Both had been shot down. One of them was weakly trying to throw up his weapon. Plunging across the deck at them were four little brown men in uniform, accompanied by Farson.

Without hesitation, Connor grimly threw up his pistol and pressed the trigger. Farson spun around and pitched sideways. The dying Manchu fired pointblank and one of the Japanese fell almost on top of him. The others separated, broke back for cover—but not before the amazed Connor recognized one of them as Colonel Honzai.

Two shots cracked out. Connor felt one of the bullets twitch at his hair.

"Wang! Wait here, bide your time, get down to the cabins to our Manchu friends."

"I can go through the ship from forward, Master."

"Do it, then. Bring him up to the bridge," snapped Connor.

He hurriedly retraced his steps. As he reached the cross passage into which the cabins of the officers opened, he came face to face with Galloway, who wildly waved a pistol.

"Ye fool, hands up!" yelled the chief. "The ship's ours—"

Connor shot him between the eyes.

A CABIN door smashed open, a pistol erupted almost in his

face. His own weapon spurted flame until the hammer clicked on

nothing. A Japanese face grinned at him in ghastly wise, and over

the body tripped Hawkins, plunging forward, coughing as he died.

No others. Connor caught up the unused pistol from the hand of

Hawkins, dropped his own empty weapon, and dashed for the

ladder.

He was halfway to the bridge again, when an outburst of yells and shots came from the forward deck. He glanced around, and a groan broke from him. The crew were loose, and knives were flashing in the level sunlight; two of his Manchus were in the midst, shooting. One of them went down, then the other. The Chinese scattered.

Only Jung Toy remained of his six men, unless he were also dead.

Connor came to the bridge. An oath broke from him, as he saw a signal fluttering up the halyards. Two Japanese stood there, behind the bridge, absorbed in their task. They faced about swiftly, flung up their weapons, but too late, Connor's bullets brought them down with relentless precision. Glancing about the horizon, Connor saw that the smoke to the northeast had become a long, low hull, evidently racing to meet them.

He started into the pilot-house, whistled down the tube. Stanley made response.

"All serene down here. Just bagged two Japanese. What's up?"

"Honzai's aboard with a bunch of men. Can you hang on there for five minutes?"

"You bet."

"Good. When I ring for half speed, drop everything and get up here on the jump."

"Attaboy! Shoot the works!"

Already Connor's hand had swung the steering gear. The yacht swerved a little, headed straight for the shore. Two miles away, or less. She was at full speed, water spurting from her sharp bows. Ten minutes at the outside, figured Connor.

He straightened up, wiping a blur from his eyes—blood. He was hurt, but had felt no pain where a bullet had gashed across his forehead. He winced as his fingers touched the place. Putting down the pistol, he got out his handkerchief twisted it about his head, and knotted it, to keep the blood from his eyes.

A spurt leaped in the water, dead ahead. Then the heavy bark of a gun. The destroyer, now coming in to overhaul them, loomed larger each instant. Connor looked at the rocky, hilly coast ahead, and his eyes were hard as flint. Two minutes, three minutes had gone. The scrape of feet sounded on the ladder, and he caught up his pistol.

IT was Wang who appeared. After him came the lean, dark Jung

Toy, who turned and gave his hand to help his master; Connor saw

blood running down from his brown fingers. Then appeared the last

of the Manchus, and Connor gave him a surprised glance. The young

man was very pale and had lost his spectacles. He was wearing a

fur-trimmed robe of yellow brocaded silk, and this had changed

his entire appearance. He had suddenly become an emperor, a

Manchu, the son of heaven indeed. Stripping the Occidental

garments from him, made him what he was.

"What has happened?" he asked, blinking around.

"Nothing," said Connor grimly, and motioned the others into the bridge-house.

Five minutes, six, had elapsed. The shore was closer now. Black ragged reefs stretched out into the water ahead. He leaped swiftly to the controls. The yacht's course changed slightly. She headed straight between two of the reefs, where showed black jutting rocks coming close up to the strip of beach.

Connor put out his hand to the engine-room telegraph and swung the lever to half speed.

A scream rang out overhead, a shell burst on the shore among the rocks; the sharper report of the gun floated after. The destroyer had plowed down close, within half a mile.

"Mr. Connor!" sounded a shrill voice from below. "Mr. Connor! May I come up?"

"Come on," responded Connor grimly.

Colonel Honzai appeared, ascending the port ladder, his hands empty. He was in uniform. As he caught sight of the last of the Manchu emperors, he saluted respectfully. Connor swung over the lever to "stop," trusting that someone below would heed the signal, and darted out to the bridge-rail, gripping it hard. With a rush, Stanley appeared, pistol in hand. Honzai began to speak, but a shrill and terrible yell of fright arose from the decks below. He swung around and saw the black rocks swooping for them.

"Hang on, everybody!" shouted Connor.

Stanley joined him, caught hold of him and of the rail. Colonel Honzai, aghast, joined both of them. There was one moment of utter stupefaction, as the yacht sped between the reefs. Her speed had slackened, her engines had ceased—someone had obeyed that final order. Another outburst of yells and cries from below.

Then a tremendous crash. A violent lurch, an awful sound of splintering, rending, smashing. The act of a madman had been accomplished.

A SECOND shock. The whole vessel shuddered and shook, crash

followed crash as the masts splintered, the smokestack toppled

over. With the bottom ripped out of her, the yacht staggered to

rest. Her prow heaved up on the sand of the shore as she canted

over sharply to starboard.

Connor dizzily came to his feet, shoved his pistol into the face of Honzai.

"Hands up! Cover him, Stanley!"

Stanley, clawing himself erect, obeyed the command. Connor turned into the bridge-house, caught the emperor by the shoulders, helped him up. Wang was already on his feet. Jung Toy rose more slowly, then sank back on his knees, and prostrated himself before the man in the yellow robe.

"Son of heaven!" he said in a faint voice. "Son of heaven—"

His head fell forward on his blood-black hands. His body relaxed, then tumbled suddenly sideways and fell, sprawling, into the scuppers. Connor caught the dazed Hsuan by the arm and led him outside, and pointed.

"Come!" he cried out, his voice ringing vibrantly. "We're ashore, do you understand? It's over. We'll get away before that destroyer can land men. We've won the game!"

"You had better surrender," said Colonel Honzai. "I have three men left—"

"And you're a prisoner." Connor flung an exultant laugh at him, and turned to Hsuan. "We'll clear the way, Your Majesty! The game's won! Follow us, set foot on Manchurian soil, your own soil, the land of your fathers! Stanley, clear the way, and I'll follow with him!"

"Attaboy!" boomed the wild, reckless voice of Stanley. "Hurray! We'll make the grade—"

"Stop!"

The last of the Manchus lifted his head. Suddenly his figure had come erect. A new light flashed in his eyes, a new firmness showed in his flaccid features. Even Connor, despite his agony of haste, was checked by this look, this manner, this voice. The blood of Nurhachu had come to life at last, for one vibrant moment.

"Colonel Honzai!" he exclaimed. "These two white men and their servant have done their best for me, have accomplished miracles. If I place myself in your hands, will you swear by the emperor whom you hold sacred that they shall not be harmed, but returned to Tientsin, free and unhindered?"

"I swear it!" The Nipponese drew himself up and saluted. "By the sacred imperial house—"

"No!"

THE cry burst front Connor. He whirled, flung out his hand at the Manchu. His face was contorted, touched with blood from his wound. His voice was hoarse, agonized, terrible to hear.

"Listen! Look! There's plenty of time, plenty! They're just lowering boats—we'll break the way for you, get you ashore, take you safe inland! Don't give up, when men have died to get you here, when Jung Toy gave his heart's blood for you—don't give up! Play out the game, go down fighting if you must—"

"No," said the Manchu, and the word was firm and hard as a blow. His eyes met the strained gaze of Connor with implacable resolution.

"My friend, you do not understand. I resign you, I resign everything. I refuse to have more men die for me. I do not want war and death, in order that I may sit upon a throne. I want peace! When I agreed to your plan the other night, I was drunk with wine. Now I shall retire within myself and seek peace. Colonel Honzai, you are of the noblest blood in Japan. Your honor is inviolate. I bargain for these men, not for myself. I accept your word."

The officer bowed respectfully and drew in his breath with a hiss, after the custom of his people.

"My word is pledged," he said.

Connor looked at them, his face white as death. Then he heaved up his arm, flung his pistol out over the rail, and staggered. The strong arm of Stanley caught him.

So the last of the Tsing dynasty passed over the sea to Dairen, and whether to a throne or to some darker destiny, Connor did not know for a long while afterward. Nor, to tell the truth, did he care greatly, for his heart was bitter.

But Earl Stanley laughed his great laugh, and went booming on down the China coasts in search of what he might find awaiting him.