THE little woman clung impulsively to Jim Stacey's hands as if they were buoys in a tempestuous sea and she drowning in the social gulf for want of a friend. And, indeed, Mrs. Arthur Lattimer was in a sorry case, as her pleading eyes would have told a less astute observer than her companion.

As to the scene itself, it was set for comedy rather than tragedy. Down below a new Russian contralto was delighting the ears of Lady Trevor's guests; the rooms were filled with all the best people; the little alcove where Stacey was sitting was a mass of fragrant Parma violets and cool, feathery ferns; the electric lights were demurely shaded; indeed, Lady Trevor always made a point of this discretion in her illuminations. There was no chance for the present of interruption, so that Stacey was in a position to listen to his companion's story without much fear of the inquisitive outsider. Gradually the look of terror began to fade from the grey eyes of Mrs. Arthur Lattimer.

"My dear lady," Stacey said, in his most soothing tones, "I shall have to get you to tell it me all over again. You see, I have been out of town for the last two or three days, and only received your hurried note an hour ago. You will admit that stating a case is not your strong point."

"What did I say?" Mrs. Lattimer asked. "I am half beside myself with trouble. Did I make it quite clear to you that I had lost the great Asturian emerald?"

"I gathered that," Stacey said. "I am also under the impression that the emerald was stolen."

"It was stolen, "Mrs. Lattimer affirmed. "I was wearing it—"

"Wearing it?" Stacey echoed. "Surely that was a little indiscreet. But how came the Empress of Asturia's jewel in your possession at all?"

"I had better explain, "Mrs. Lattimer went on. "As you know perfectly well, my husband is a dealer in precious stones. He is probably the greatest man in this line in Europe. You are also aware that the Empress of Asturia is in London at the present moment. She has a fancy to try to match that priceless stone; in fact, if possible, she wants two more like it. She came very quietly to our house in Mount Street and saw my husband on the subject. Of course, he held out little hope of being able to execute the commission, but he said that he had heard of a couple of likely stones in Venice, and that, if Her Majesty would leave the emerald with him, he would see what he could do. To make a long story short the stone was left with him, and up to three or four days ago was locked away in his safe—a small safe that he keeps in his study."

"Lattimer showed you the stone, of course?"

"I have my husband pretty well in hand," Mrs. Lattimer laughed. "He showed me the emerald the next day, and a sudden fancy to wear it came over me with irresistible force. It was no great matter for me to get possession of the key of the safe. My husband was away, too, for a night, and on Monday evening I went to a bridge party at Rutland House, wearing the emerald as a pin. I was just a little frightened to find my borrowed gem so greatly admired. We were having supper about twelve o'clock—a sort of informal affair at a sideboard in the drawing-room—and I was induced to hand the stone round. Without thinking, I unscrewed it from the pin and stood there laughing and chatting keeping my eyes open all the same."

"Knowing something of the kind of woman who is a professional bridge-player?" Stacey laughed.

"Precisely," Mrs. Lattimer said. "There were one or two present whom I would not trust very far. Well, in some extraordinary way the stone was lost. Nobody seemed to know where it was; nobody would confess to having taken it. I am afraid I lost my head for the moment. I know I said a few hard things; but there it is—that stone is gone, and unless I can recover it by midday to-morrow I am ruined, absolutely ruined."

"Your husband?" Stacey hinted.

"Knows nothing. I have not dared to tell him. I have waited till the last possible moment on chance of the stone being recovered. You see, I stole the key of the safe and made my husband believe that he had lost it. It is a wonderful safe of American make, and no one in London can unpick it. My husband telegraphed to New York to the makers to send a man over, and he arrives by the Celtic to-night. Unless the stone can be found first—"

Stacey nodded sympathetically. He quite appreciated the desperate condition of affairs.

"I see," he said, thoughtfully. "If the stone turns up, you will contrive to find the lost key and restore the gem to its hiding-place. And now I must ask you if you suspect anybody."

The pretty little woman flushed slightly. She glanced about her as if afraid that the Parma violets might become the avenue that leads up to a libel action.

"Yes," she whispered. "It is Mrs. Aubrey Beard."

"Oh!" Stacey muttered. "So the wind sets in that quarter. My dear lady, this is a serious thing. Mrs. Aubrey Beard has a high reputation. She is the wife of a Cabinet Minister, and, so far as I know, has none of the society vices—"

"Oh, hasn't she?" Mrs. Lattimer sneered. "Why, that woman is one of the most inveterate gamblers in London. It is an open secret that her bridge debts amount to over five thousand pounds—at least, they did last night, and I haven't heard that they were paid to—day. But this seems to be news to you?"

"Well, yes," Stacey admitted. "If Beard knew this there would be a separation. Now tell me, what grounds have you for making this accusation?"

"My dear Mr. Stacey, I am making no accusation whatever. I am merely telling you whom I suspect. To begin with, Mrs. Beard hardly touched the stone at all, though I could see her eyes flash strangely when she saw me wearing it. I have very little doubt that she guessed my little deception. You will remember that Mr. Aubrey Beard was in the Diplomatic Service at the Asturian capital, and that his wife would have every opportunity of becoming acquainted with the Royal jewels. At any rate, she hardly touched the gem, and seemed a great deal more interested in a dish of chocolate bon-bons in front of her. She is passionately fond of sweets."

"I suppose, practically, your supper consisted of that kind of thing?" Stacey asked. "Being no men present, you would naturally think very little—"

"Oh, of course," Mrs. Lattimer said, airily. "We had very little else besides a few grapes and a sandwich or two. Mrs. Beard was nibbling at her chocolates up to the very time we left. It was then that she dropped a remark which aroused all my suspicions. She said she hoped that I should find my emerald again, and that if the Empress of Asturia was seen wearing one very like mine I should not accuse her of theft."

"Really, now," Stacey said. "This is most interesting to a society novelist like myself. In other words, Mrs. Beard practically accused you of stealing the very thing that you charge her with appropriating. She let you know quite clearly that she guessed exactly what had happened. It was a hint to you that if you saw anything you would not dare to make it public. You have honoured me with a difficult problem to solve, and I have solved many. Mrs. Beard is a cleverer woman than I imagined; but suppose she has already disposed of the emerald?"

"But she hasn't," Mrs Lattimer whispered, eagerly. "If she had done so, she would have paid her bridge debts. You know how necessary it is to discharge obligations of that kind. I feel quite sure that the emerald still remains in Mrs. Beard's possession."

"Meaning that she has found no way of disposing of it?"

"Not yet. I have had her carefully watched, and I have come to the conclusion that her cousin, Ralph Adamson, is in the conspiracy. Of course, you know he is a great admirer of Mrs. Beard's; there is nothing wrong, but I am certain that he would do anything for her. I know he was at her house for a long time the day before yesterday, and that he subsequently paid a hurried visit to Amsterdam, where, I understand, it is a fairly easy matter to dispose of stolen jewels. If he had been successful with his errand, Mrs. Beard's bridge debts would have been paid by now. But what is the use of our talking like this? You know the whole story; you can see the dreadful position I am in. Is there any possible way of getting me out of the difficulty before to-morrow afternoon?"

"I have worked out some sort of a theme," Stacey said, thoughtfully. "Your letter was very incoherent, but now that I know all the facts I begin to feel sanguine. Tell me—"

"Oh, I will tell you anything. Your very presence gives me courage. I see that you are going to ask me a question of the utmost importance. What is it?"

"It is important," Stacey said, gravely. "I want you to try and remember exactly what sort of bon-bons Mrs. Beard was eating on the night that the robbery took place."

Mrs. Lattimer laughed in a vexed kind of way.

"What a frivolous creature you are!" she said. "As if a trivial thing like that could possibly matter."

"My dear lady," Stacey said, in a deeply impressive manner, "the point is distinctly and emphatically precious. I pray of you not to speak at random. Was it not somewhere in the Far East that the accidental swallowing of a grape—stone changed the destinies of a nation? Think it out carefully."

"You are a most extraordinary man," Mrs. Lattimer said, almost tearfully. "So far as I can recollect, the sweets in question were chocolate fondants filled with almond paste. Yes, I am quite sure that that is a fact, for I remember Mrs. Beard saying that almond paste was her favourite sweet."

"We are getting on," Stacey said. "My education on the head of feminine gastronomy is somewhat limited, but I have a hazy kind of idea that these particular dainties are fairly large in size. They would be nearly as big as my thumb, I suppose?"

"Quite that," Mrs. Lattimer said, gravely.

"Ah! then your humble maker of romances is not to be baffled. My way lies clear before me. Now, one more question. Did I not understand from Lady Trevor that Mrs. Beard is going to put in an appearance here to-night?"

"So I believe," Mrs. Lattimer replied.

"She is giving a dinner to semi—Royalty and will not be here till comparatively late. I feel certain she will come, because I saw Ralph Adamson just now listening to the new contralto."

Stacey rose gaily from his seat and fell to admiring the banks of violets with which the room was lined. He caught Mrs. Lattimer's reproachful eye and smiled.

"À la bonne heure," he said. "Give yourself no further anxiety. The curtain is about to go up, the play will commence. If that emerald is still in the possession of Mrs. Aubrey Beard, I pledge you my word it shall be restored to you before you sleep to-night. Smile as you were wont to smile, and come with me."

THE great contralto had finished her song amidst the tepid applause which passes for enthusiasm in society, and for a moment the proceedings seemed to languish. In the great salon some two hundred of the chosen ones had gathered, waiting like children for someone to amuse them. A social entertainer followed, only to be received and dismissed in chilling silence, which it is to be hoped was somewhat compensated by the size of his cheque. Stacey came cheerfully forward and shook hands with his hostess.

"I began to think you were going to throw me over," she said. "So awfully good of you to offer to come here and amuse these people. Upon my word, society nowadays is worse than a set of school-children. What should we do without our society entertainers? You have such clever ideas! Is it possible that you have a new sensation for us to-night?"

Stacey intimated modestly that it was just on the cards. He noticed the reproachful way with which Mrs. Lattimer was regarding him. He sidled up to her presently.

"It is all part of the system," he said.

"Like Mr. Weller's reduced counsels. It is not when I smile that I am at my joyous zenith. I am here to-night exclusively on your business, and if I do play the clown there will be a good deal of the tragedian behind it. I promise you that there is a large percentage of method in my madness."

There was a murmur among the languid audience, a kind of electric thrill which was in itself a compliment to Stacey. Apart from his literary fame, as an originator of novel and frivolous amusements he had a reputation all his own. There was a good score of men and women present who could have told stories of his marvels, and who could have risen up and called him blessed had it been discreet to do so. There were others present who looked upon Jim Stacey as a mere society scribbler and charlatan, but these only added piquancy to the situation.

At the earnest request of Lady Trevor, Stacey proceeded to do a few simple experiments in the way of thought-reading. An immaculate youth, utterly bored and blasé, lounged up to him and remarked with casual insolence that he had seen this kind of thing just as well done, if not better, at a country fair. Stacey smiled indulgently.

"I dare say," he said. "But, you see, I have apparently mistaken the intellectual level of a portion of my audience. If you like I will endeavour to read your thoughts, provided always that you can concentrate your mind long enough upon any given topic."

"Tell me what is in my pocket, perhaps," the other said. "There is a challenge for you, Stacey."

"Which I accept," Stacey said, promptly.

"If anyone will blindfold me, I am prepared to give a strict account of the contents of Mr. Falconer's pockets, only he must promise me that he will think of nothing else during the whole of the experiment"

There was a ripple and stir amongst the audience, a kaleidoscope whirled and flashed on many-coloured vestments, and a sea of white faces turned in Stacey's direction. One of the ladies present emerged from the foam of fashion and whipped a cambric handkerchief across Stacey's eyes. His victim stood a little way off, so that the performer could just touch the tips of his fingers. There was a long, tense silence before Stacey commenced to speak.

"I begin to see," he said, in a thrilling voice, which began to carry conviction to a section of his audience. Whatever the man might have been, he certainly was a consummate actor.

"I begin to see into some of the secrets of the typical gilded youth of our exclusive society. Imprimis, in the vest-pocket, a gold cigarette-case; the cigarette-case is set with diamonds and bears in one corner two initials which are certainly not the initials of the fortunate owner. Inside the case are three cigarettes and half-a-dozen visiting-cards, which also do not bear the impress of the carrier's autograph. If Mr. Falconer likes I will read out the names printed on those cards, beginning at the bottom and working backwards to the top. The first card is that of a lady——"

"Here, I have had enough of this," Falconer burst out in some confusion. "I don't know who has been playing this trick upon me, but I consider it anything but good form, don't you know."

A ripple of laughter ran over the sea of eager faces as Falconer backed away from the table, his face a healthier and rosier red than it had been for some time past. Stacey's challenge to his victim to complete the experiment was met with a direct negative.

"Then you won't go on?" Stacey said, in his most insinuating manner. "Pity to break it off just at the interesting stage, don't you think? I was just about to tell your friends the story of that cheque in your waistcoat-pocket—"

Something like a cry of dismay broke from the unhappy Falconer, and the brilliant red of his face turned to a ghastly white. As he slipped away, Stacey turned to the audience and inquired if anybody else there would like to try the same experiment. Quite a little knot of men came forward.

"Cannot I induce some of the ladies to give me a chance?" Stacey pleaded. "It seems to me manifestly unfair—"

"Fortunately for us we have no pockets," Lady Trevor cried. "We keep all those things in our conscience. Positively, we shall have to send Mr. Stacey to Coventry if he does not hold his wonderful powers a little more in hand. I dare say there are men present who are so marvellously honourable and pure-minded that they have nothing to disclose. If there are any such here, let them come forward for Mr. Stacey to experiment upon."

"My dear Ada, what would be the use of that?" a frisky dowager shrieked at the top of her voice. "We don't want to sit here and listen to the simple annals of the good young man who died, so to speak. Won't someone kindly come forward—somebody with a terrible past——and let Mr. Stacey reveal the scandal for us?"

A frivolous laugh followed this suggestion, and somebody maliciously suggested that the speaker herself might afford information for many piquant revelations. A tall, military-looking man came forward and suggested a new variation of the interesting séance.

"Wouldn't it be much better," he said, "if we changed possessions with one another and gave Mr. Stacey a chance of guessing who the different articles belong to?"

"Wouldn't it be better," another man remarked, "to drop all this nonsense and proceed to something more rational? After all said and done, if Mr. Stacey can do this, he can forecast where things are hidden at a distance."

"Of course I can," Stacey said, with cheerful assurance. "Would you like to try me? Will somebody be good enough to give me a sheet of paper and envelope? I should prefer to have Lady Trevor's own letter-paper, so that there could be no suggestion of confederacy in the business. Will anybody come forward and write a note for me——only just a few words?"

As Stacey spoke he glanced significantly at Mrs. Lattimer, and indicated the man who was standing by her side. She seemed to understand by instinct exactly what he meant, for as the paper and envelope came along she snatched eagerly for it and placed it in the hands of the man by her side.

"You do it, Mr. Adamson," she said. "We can always trust you, because you are so cool and clear-headed, and if there is anything wrong you can easily detect it."

The tall young man with the dark eyes and waxed moustache shrugged his shoulders and smiled. Someone pushed forward a small table, on which stood an inkstand and a pen. The would-be writer gave Stacey a supercilious glance, and intimated that he was ready to begin.

"That is very good of you," Stacey said.

"Just a few words. Write—'It is not safe where it is. Bring it with you to-night.' No; there is nothing more. Lady Trevor, will you be good enough to hand me that little silver basket of sweetmeats which I see on the china cabinet behind you? All I want now is a small box—a cardboard box, about four inches square."

The whole audience was following the experiment breathlessly by now. It was almost pathetic to see the childlike way with which they gaped at Stacey. They watched him with breathless interest as he folded the note and placed it in the cardboard box. Then he very carefully picked out a chocolate fondant from the silver basket of sweetmeats and gravely placed it inside the box.

"This particular confection is not exactly what I wanted," he said, with the greatest possible solemnity. "I should have preferred a fondant tilled with almond paste. This I imagine to be Russian cream, but no matter. I will now proceed to tie up the box and place a name upon it. I will ask Lady Trevor not to look at the name, but to get one of the footmen to take it to the house for which it is intended. That is all, for the present."

Lady Trevor signalled to a passing servant and intimated that Stacey had best give the box into his custody direct.

"You are to go at once," she said, "and deliver this package at the address written on the outside; but perhaps Mr. Stacey would prefer that you placed it direct into the hands of the person for whom it is intended?"

"That was the idea, "Stacey said. "I shall have to crave your patience for half an hour or so, and, meanwhile, I shall be only too pleased to show you another form of entertainment. Before doing that I should like to have something in the way of supper and a cigarette. Surely Mr. Adamson is not going! Oh, come, seeing that you are part and parcel of my experiment I really cannot permit you to go in this way. Come along with me as far as the supper-room and join me in a glass of champagne and a cigarette."

Adamson turned and Stacey took him in a friendly way by the arm. Once in the hall the latter's manner changed and his face had grown stern. His eyes were hard and brilliant.

"Not yet, my friend," he said. "There are many things I can do, and many things I know which would astonish you if I were disposed to betray the secrets of the prison-house. If you are discreet and silent all will be well, but if you elect to defy me—well, there are certain episodes connected with a period of your life which would be just as well—"

THE supper had been over for some little time, and most of the guests who were not playing bridge or otherwise frivolously engaged had gathered in the salon intent upon seeing the sequel to Stacey's experiment. Mrs. Lattimer sat there with flushed cheeks and glittering eyes. The suggestion of the military-looking guest that an interchange of pockets should be made had been carried out. If this had been intended, as doubtless it was, to give Stacey a fall, it had been a long way from being successful.

He had snatched the handkerchief from his eyes and was just getting accustomed to the glare of the room when his glance met that of Mrs. Lattimer. She turned her head swiftly in the direction of the doorway, where stood a handsome woman, whose cold, beautiful face was watching somewhat critically the scene in front of her. It did not need a second look on Stacey's part to recognise Mrs. Aubrey Beard. He could see, too, that under that cold surface something in the nature of a volcano was raging. He could see that cold, icy bosom heave tempestuously, for the diamonds on her breast flashed and trembled like streams of living fire. Stacey quickly turned and whispered something in the ear of Ralph Adamson. The latter seemed to hesitate a moment; then, with bent head and lips that trembled, disappeared slowly through a doorway leading towards the conservatories. In the same cold, stately way Mrs. Aubrey Beard came forward and languidly asked the source of all this amusement.

Her glance at Stacey was icy enough—indeed, there was no love lost between them. It seemed hard to believe that this placid, emotionless creature could have been the reckless gambler that Mrs. Lattimer had proclaimed her.

"Ridiculous," she said, in her stately way. "It is preposterous to believe that Mr. Stacey could do these things without the aid of a confederate."

"Oh, they have their uses," Stacey said, airily. "For instance, I don't mind admitting now that some of this business to-night has been what I may be allowed to term a game of spoof. I have half-a-dozen friends here to—night who gave me all the information I wanted and acted as my lieutenants, and very well they did it, too, as you all must admit. But it is not all nonsense, as I am prepared to prove, if Mrs. Beard but challenged me."

"Is it worth while?" the fair beauty sneered. "I don't think anybody would accuse me of being Mr. Stacey's confederate. If he can guess—for it could be no more than guesswork —what is in my pocket he is welcome to his triumph."

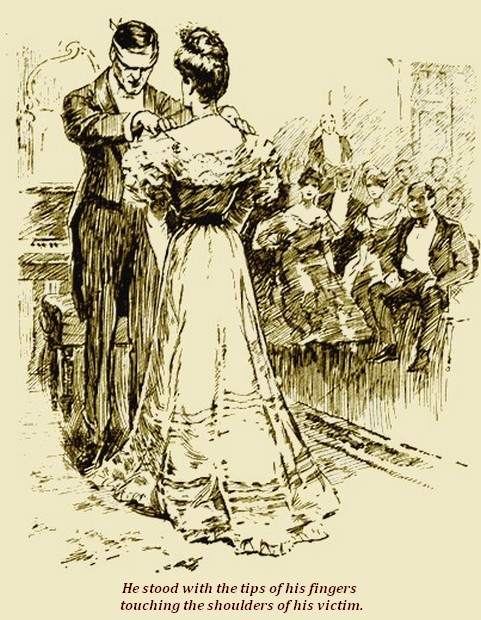

Stacey's keen eyes blazed for a moment, then he resumed his normal expression. He asked for someone to blindfold him; he stood with the tips of his fingers touching the shoulders of his victim. The flesh, cold as it looked, seemed to burn under his touch.

He could hear the quick indrawing of the woman's breath. Every nerve in her body was quivering.

"I do not see much, "he said, in a dreamy kind of voice. "Nothing but a handkerchief in Mrs. Beard's corsage. But stop! There is a small object wrapped up in that handkerchief—a small cardboard box. I can see through that cardboard box now. Inside is an oblong object, brown and sweet to the taste; it is nothing more or less than a chocolate, an ordinary common chocolate filled with Russian cream; at least, I suppose it is filled with—Russian cream. Good heavens, some of you will remember—"

Stacey paused abruptly and tore the handkerchief from his face. He seemed to be greatly moved by some overpowering emotion; he glanced almost with horror into the eyes of the cold, stately woman opposite. She had not moved, she had not changed, save for a burning spot on either cheek and a peculiar convulsive twitching of her lower lip.

"This is more or less part of my experiment with the chocolate creams," Stacey said. "You will remember that a chocolate cream was the simple object that I placed in the cardboard box which was to be dispatched to an address known only to mysel£ I was challenged to discover a certain object hidden somewhere at a distance, and in my own mind I decided where that object was and what it was. Presently I will show you. Meanwhile, I ask Mrs. Beard to admit that I have been absolutely successful, and to produce the small box which she has wrapped in her handkerchief.

The speaker turned just for a moment and his eyes flashed a stern challenge into those of the woman opposite. Very slowly and reluctantly she placed her hand inside the bosom of her dress and produced a lace handkerchief in which lay the small cardboard box which Stacey had dispatched by hand of the footman. The breathless audience watched Stacey as he opened the box and took therefrom apparently the same bon-bon which he had placed in the receptacle some half-hour before.

"I see you are all utterly mystified," he said. "Indeed, I am quite sure that Mrs. Beard is as mystified as the rest. Before successfully concluding my little comedy I should like to have a few words with Mrs. Beard alone. I flatter myself that Mrs. Beard is just as anxious for a few words with me."

The woman bowed coldly. Not for an instant had she betrayed herself She led the way in the direction of the library, and once there Stacey closed the door. He wasted no time in words; he raised the chocolate fondant to the light and snapped it in two. From the inside there fell a wondrous green shining stone—none other than the famous emerald belonging to the Empress of Asturia. Stacey spoke no word: he stood there waiting for the inevitable explanation. Then Mrs. Beard began to speak.

"You are a wonderful man," she said, hoarsely. Her breath came fast, as if she had been running far. "I stole that emerald the night of the bridge party at Rutland House. I managed to conceal it, without being seen, in that chocolate fondant. I had my bridge debts to pay; I dared not tell my husband. I pass before the world as a cold, unfeeling woman, but my love for my husband has hitherto been the one passion of my life. I will not ask you how you have discovered all these things, for you would not tell me if I did. You seem to have guessed that my cousin, Ralph Adamson, was in the conspiracy, and you are correct. By what means you tricked him into writing those lines to-night, and getting me to place myself red-handed in the lion's jaws, I cannot pretend to understand, but there is the emerald and here is my confession. I have said a great deal for a proud woman like myself; all I ask you to do is to make it as easy for me as you can. If there is any exposure—"

"My dear madam, it is entirely in your hands to say whether there will be exposure or not," Stacey explained. "If you leave it to me,I will show you the way out. Mrs. Lattimer came to me with the facts, and I carefully engineered this little comedy with a view to saving my fair friend's reputation and sparing you a humiliating scandal. Still, it was not fair of you to try and close Mrs. Lattimer's mouth by letting her know that you were aware to whom this magnificent stone really belongs. By doing so you thought to frighten her and place her in such a position that she dare not accuse you of the theft. What we have to do now is to go back to the salon and make the dramatic announcement that I have been entirely successful in the matter of my experiment. If you could smile a little I should be greatly obliged. Yes, that is better. Now let us pretend to be talking upon quite indifferent topics. Anything will do."

There was a sudden hush in the conversation and a rustling of skirts as Stacey and Mrs Beard entered the salon. Mrs. Beard was smiling now; she beamed quite graciously upon her companion, though the brilliant red spots still burnt upon her cheeks like a stain.

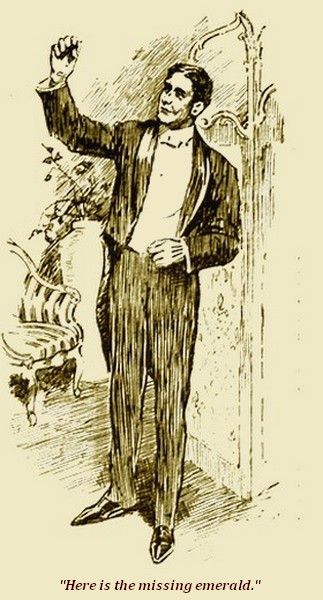

"You will all be glad to know that my experiment has been a perfect success," Stacey said. "I was challenged to-night to say where some object was which was hidden at a distance. It is an open secret to you all that a few nights ago Mrs. Lattimer lost a valuable emerald; it occurred to me that the finding of this stone would be a fine trial for me, and incidentally an exceedingly good advertisement. I cannot betray the secrets of the prison-house and tell you the inner significance of the bon-bons, for that would be revealing my occult science. Sufficient to say I divined the hiding-place of the missing stone. It was carried away quite by accident that night in a fold of Mrs. Aubrey Beard's dress. Perhaps she was coming here to bring it back; at least, I will not insult the lady by any other supposition. At any rate, here is the missing emerald. It may have been a case of mental telepathy; it was very strange that it should occur to Mrs. Beard to search the folds of that dress at the very moment when I turned my will-power in the direction of the hiding-place of the stone."

Not a soul there but believed every word that Stacey uttered. His manner was complete and convincing. He turned towards Mrs. Lattimer and pressed the shining jewel into her hand.

"Not a word," he whispered. "Take it all for granted. If there were not so many fools in the world I could not have carried this thing off as I have to-night. I will call upon you to-morrow and explain everything. Meanwhile, go up to Mrs. Beard and thank her. Gush at her—kiss her, if you are not afraid of being frozen. Above all, be discreet and silent."

Stacey turned away and walked in the direction of the refreshment-room. He found Adamson there, moodily smoking.

"The play is over," he said. "The comedy is accomplished, and you will understand that this is emphatically a case where the least that is said is the soonest that is mended."