RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

THE stage manager took the matter very seriously. He stood with his back to the big wood fire in the holly-decorated hall and frowned at the telegram in his hand. The man in the beehive chair smiled. Nothing mattered to him so long as he had left London and Fleet street—especially Fleet street—behind him. Carlton Dane was in holiday mood. Just now, to the brilliant chief of the Comus, nothing mattered. This combination of editor, journalist, and playwright had escaped from the trammels of office for three weeks, and he was not seriously disturbed to bear that Lottie Lane had sprained her ankle practising loop threes at Prince's.

"What's the good of worrying about it, Daintry?" he asked.

"But, my dear chap, it's your play!" Daintry protested. "And look at our reputation! The Marston House Christmas theatricals have become almost classical. We are the first amateur combination in England. The 'Morning Post' never gives us less than a column. You know that we treat ourselves awfully seriously. We shall have two hundred people here on the night that your 'Fly in Amber' is produced. And everybody knows that Willoughby Chesney is going to play the comedy at the Atheneum in the spring."

"I did not sell it to him till after it was arranged that my comedy was to be produced here, Daintry."

"My dear boy, what has that got to do with it? Chesney liked the play so well that he made no objection to your comedy being produced as a Marston House attraction before it saw the light on his own stage. There is nobody who can take the part Lottie Lane was cast for—at least, no amateur woman I can think of. And you sit there smoking your cigarette as if it were a mere trifle."

"What are you going to do about it?" Dane asked.

"There is only one thing to do," Daintry said, sorrowfully. "We shall have to give the part to a professional. There is no one here who could play Hilda Lorrimer."

"Oh, yes, there is, my dear boy. I need hardly say that I mean Mrs. Leatham."

"Hilda Leatham!" Daintry cried. "My dear fellow, my reason is tottering. To think that I should have overlooked her! And she is in the house all the time! If she will take the part, I shall regard Lottie Lane's sprained ankle as a blessing in disguise. I'll go and find her."

Hilda Leatham was curled up in a big armchair, in the library, gazing thoughtfully into the heart of the red log fire. The book she had been reading had fallen from her lap, and lay on the floor. It was a very white, slightly weary, but beautiful face that looked up as Daintry entered. The deep violet eyes were slumbrous now, but they suggested passion and sorrow, contentment and amusement, all at once. She stretched her long, lithe limbs, her present pose was easy and peaceful.

"What's the latest trouble?" she asked.

"Is my face so eloquent as that?" Daintry retorted. "Mrs. Leatham, I am worried. The fair reputation of the Marston House Dramatic Society is in danger. Lottie Lane has met with an accident, and cannot play Hilda Lorrimer in Dane's comedy. There is no other amateur I know of who can take the part. But that won't permit them all wanting it. And that is why I kept the dire tragedy to myself, will you play it?"

A wave of colour swept over the beautiful, pallid face. Daintry could see the eager trembling of the red lips, the flash in the velvet eyes. A little sigh escaped Hilda Leatham.

"I'm afraid not," she said, with lingering reluctance. "You see, I promised my husband."

Daintry looked away for a moment. It seemed a sufficiently feeble excuse. If gossip were anything like true, Hilda Leatham had not seen her husband for a year. They had been a devoted couple at first; but latterly they had drifted pretty widely apart. Leatham was away shooting, or fishing, or something of that kind; Norway, South Africa, the Rockies had all been visited in turn. The house in town had been let. Leatham and his wife travelled from one country house to another, but they never stayed under the same roof. The excuse nettled Daintry.

"But these are private theatricals," he urged. "Who could object to them? I am more anxious to make a success of the first venture, especially as Chesney has paid us so tremendous a compliment. The play will be a frost without you or Miss Lane. We have no woman who could carry the part, Mrs. Leatham, I throw myself entirely on your mercy."

A thin smile flitted over Hilda Leatham's face. The temptation of it stirred her pulses. She had been very fond of her profession—to give it up had been a wrench. The artistic chord was touched; the old ambition stirred in her breast. She had loyally kept her promise; but then there was a vast difference between the amateur and the professional stage. A rebellious red glowed in her cheeks. And the part was certain to be a good one, or Annabel Henson, of the Atheneum, would never have taken it. She stood up now, a tall, thin, graceful figure, with the firelight glistening on her glorious hair. She held out her hand to Daintry.

"Very well," she said. "I'm bored to death. I was never made for an outdoor woman. Let me have the part after dinner, and I will play it. I have given my word."

Daintry went off in a rapture of delight, "Prince's," after all, was a blessed institution. The cloud of misfortune had lifted, and the light of Marston House shone more brilliantly than ever. The success of the new comedy was assured. Daintry made his big announcement during dinner—a declaration welcomed with the most unbounded enthusiasm. There was no sign of jealousy anywhere; indeed, the whole thing was accepted as an intervention of a benign and farseeing Providence. Hilda Leatham took her typed part presently and returned to the library. She was not likely to be interrupted there; indeed, Daintry had issued something like a proclamation to that effect.

The lights were dim and faded, and the red heart of the fire was warm and grateful. From the dark brown walls the pictures of dead-and-gone Daintrys looked down. Here was the fine fragrance of Russia leather that seemed to go with well-appointed libraries. There was something in the aspect of the room that appealed to Hilda Leatham. All the artistic impulses, the glowing temperament, were aroused now as she looked at the typed sheets in her hands. She was going to live again after the hibernation of the last year or so. If Philip had only asked her a question or two; if he had only given her a chance to explain. But he took everything so seriously. She had not told the truth as to her visit to Archie Mead's rooms; but then Phil would not have understood. It was quite a harmless lie, after all. Archie had never cared for anybody but——

But what was the use of dwelling on that? The whole thing was done and ended, and she must make the most of what life held in store for her. Still, she had given up everything for Phil. She honestly thought that the sacrifice was all on one side. If Philip had only given her a chance!

She turned resolutely to the typed slips in her hands and began to read. Oh, it was a fine comedy enough. Chesney's judgment was rarely at fault, and he had pronounced "A Fly in Amber" to be the daintiest effort he had ever read. The tears and laughter were beautifully balanced, comedy and pathos walked hand in hand. Even as a story the play was worth reading.

But it was something more than a story. As Hilda read her interest deepened. There was something oddly familiar about it, some suggestion of a closer chapter from her own life. And yet nobody knew anything about that, for she had not told a word of it to anybody. She was not picking up the threads of her part now, she was reading a thrilling drama. She came to the end of it presently, and the loose sheets fluttered into her lap.

"The long arm of coincidence," she murmured. "But never was a coincidence like this before. If Philip had only been a friend of Dane's! But they have never met; he told me so to-night. And here is the story of our own misunderstandings told in the play! And if Philip had stood for his portrait he could not have been more faithfully drawn than the hero of this comedy. Surely Carlton Dane would never have invented this. Somebody must have told him the outlines of our—I wonder if I dare ask him? Still, nobody but Philip and myself know and we are too proud to tell a soul. It must be a coincidence. And I shall play the part as I never played before because it's me. I shall be able to confess everything to the audience, and they will cheer and applaud and give me the whole of their sympathy, because they will feel for me and think that I was right after all. They will love me all the more for the humanity of my folly. And yet it hardly amounted to folly. Indiscreet, perhaps, but then in Bohemia we have our own code. I am sure it is a kind and Christian one. And if Phil were only here to see for himself. Oh, what am I saying?"

She covered her burning face with her hands, and the tears trickled through her fingers. Well, she would go on with it, she would get all the sympathy she needed. And those people would applaud Hilda Lorrimer, unconscious that they were taking the part of Hilda Leatham. She picked up the sheets again. These were experiences of her own, little words and manners she used daily. Really, she must ask Dane where he got it all from. All a dream, perhaps.

"I'll get him to tell me in the morning," she said. "But how—how could he know?"

What did he know? And where did his knowledge come from? Not from Philip Leatham, at any rate. He was the last man in the world to tell a soul of his troubles. And yet here was the story of the tragedy set out so that all who ran might read. After all said and done, Hilda Leatham had asked Dane nothing. She made up her mind to watch him at rehearsals instead. It was not an easy matter, for she was an artist to her finger tips, and she could do nothing but throw herself heart and soul into her part. Still, there were chances.

The last dress rehearsal was a veritable triumph. Everybody seemed to feel that a high note had been touched. The leading lady dropped into a chair and regarded Hilda with a sort of quivering admiration.

"My dear, you are marvellous," she said. "To use the expressive vulgarism, you are it. You are the wife who has allowed her feelings to get the better of her. And anybody would think you were playing a chapter from your own life. I felt as if I could strike you for not telling your husband everything, especially as he had found you out. And yet your pride has all my sympathy. Mr. Dane, the part will never be played so well at the Atheneum."

"That I am certain of," Dane smiled. "Though I hope nobody will repeat my opinion. Your husband did the stage a sorry service when he married you, Mrs. Leatham."

Hilda listened to it all vaguely. She was waiting for her chance to come. It came presently when light refreshments were served on the stage. Dane came over and congratulated her.

"They expect an audience of over two hundred to-morrow night," he said. "They little realise what a treat there is in store for them. If I had written that part for you, I could have done no better."

Hilda Leatham turned her velvet eyes on her companion. "Are you quite sure you didn't write it for me?" she asked.

"How—how could I?" Dane stammered. "It was only by the merest accident—a most, fortunate and blessed accident, I admit, but——"

"I was speaking at random, Mr. Dane. I am interested in coincidences. Now, do you know that you have stolen a story and founded your play on it?"

"My dear lady, the story was given me. I was told that I could do what I liked with it."

"You mean that my—but that is ridiculous. I am rather afraid that we are at cross purposes, Mr. Dane. Let me put it another way. Is your play founded on facts?"

"Upon my word I believe it is," said Dane, with the air of a man who has made a discovery. "I didn't realise it until this moment. In a way, the plot of 'A Fly in Amber' came to me from an outside source—in the form of a short story."

"Oh, yes, I had forgotten you were the editor of the 'Comus.' Please go on. A—a friend of mine had a precisely similar experience as that which befell Hilda Lorrimer in the play. And it occurred to me that perhaps in some way you had—you understand——"

"Been made a confidant of? Nothing of the sort, I assure you. The plot came to me as a story—a short story submitted to me in the usual way. The story was there, and the pathetic humour of it. A gem in the rough—the very rough. I wrote and told the author so, and asked him to come and see me. He declined, and gave me the plot to do as I liked with."

"You mean that you never saw him? Haven't the slightest idea who he is?"

"Precisely. So far as I am concerned, the incident is at an end. How the idea was used you have seen."

"You have made up your mind that the writer of the story was a man?"

"I am certain of it. The handwriting, the style, the final chapter, everything points to that conclusion. And the story was written from the man's point of view. The hero is a good bit of a Puritan, though he married a wife who had been on the stage. He finds that his wife is corresponding with an old actor admirer of hers, he knows that letters are being smuggled and concealed. He has one in his hand. He follows his wife and sees her in the arms of the actor admirer——"

"That he didn't!" Mrs. Leatham said, vehemently. "I—I beg your pardon. Go on."

"Really, there is very little more to be told. The hero is a little blind, a little self-sufficient. He makes no allowance for his wife's artistic temperament. He magnifies a sentimental impulse into a guilty secret. He gives the woman no chance to explain, and she is far too proud to ask for one. That is practically all the story. But on the stage it has to go further. I have to get sympathy for the woman and show that she has really acted with a clean mind, and on a generous impulse."

"You have done it magnificently, Mr. Dane. Please go on."

"Is there any need to tell any more? I think if the man who wrote the story saw the play he would understand. I am taking it for granted that the story is a human document—a page from the history of that man's life. It must have been, because the story as a story was so crude and badly constructed. That's why I had to elaborate it in my comedy. And I want everybody to feel that the tragedy is behind it."

Hilda Leatham breathed a little more freely. "It is all exceedingly interesting," she murmured. "Then all this is based on a chance short story and elaborated out of your wonderful insight into human nature? I began to think for the moment that you actually held the secret of my—my friend's trouble."

"No. Authors are frequently accused of that sort of thing. They get indignant letters from strangers. Sometimes the letters are pathetic, and ask for advice. The writers assure us that we have exactly portrayed their own lives and troubles. How could it be otherwise when so many books are written? You can assure your friend that she is perfectly safe, if her husband is that class of fool——"

"I am afraid that he is," Mrs. Leatham said, unsteadily. "If he were here to see the justification——"

A whimsical smile crossed Dane's face. "Many thanks," he said. "You have given me an idea for still another play. Why not try and get him here? And get your friend as well. Once he has seen the last act of 'A Fly in Amber,' and watched your marvellous vindication of the heroine, he will abase himself before his injured wife. Now, if I could only work that scene into a play——"

But Mrs. Leatham was no longer listening. There was a dim look in her eyes as she moved away. She was a little dazed by the events of the evening; just a little carried away by her personal triumph. It was like one of the old first nights come back again. She had given up all this for the sake of a husband who had never even tried to understand her. Perhaps if he were present to-morrow night—but what was the use of thinking of that? She had not the remotest idea where he was. Slaughtering some inoffensive animal in some distant part of the world, probably. What did it matter? What did anything matter now? She would think of nothing but the triumph of the morrow. At any rate, she was going to live for the next few hours.

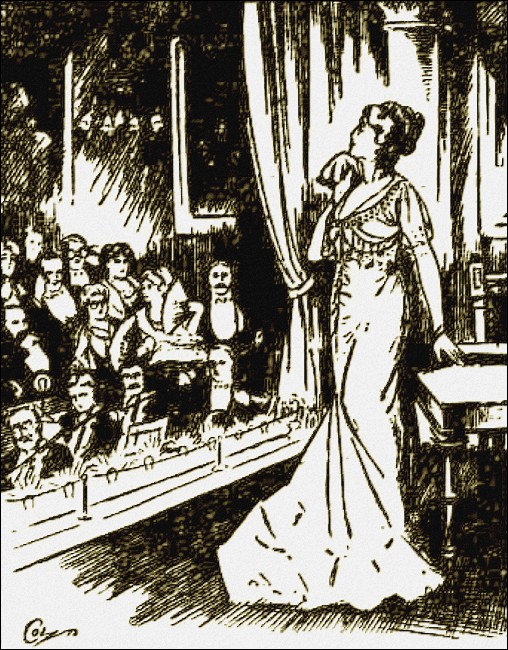

After all, there was nothing like it. She had all the people there in the hollow of her hand. The cream of the county was there—charmingly dressed women, beautifully groomed men. For the best part of ten minutes that glittering crowd had hardly breathed. Hilda played upon them as if they had been a harp and hers the hand that swept the strings. There would be an elaborate supper presently, but nobody was thinking of that. They were all heart and soul with the beautiful figure in the centre of the stage. Hilda paused just for a moment, and for the first time her glance swept the audience. And there, in the second row of the stalls, was the man she was mechanically playing to all the time—her husband!

And there... was the man she was mechanically playing to all the time—her husband!

Her splendid training stood her in good stead now. Another glance, and she understood. Philip was staying with his friends, the Heywoods. Here they were in front with him. They had come from some forty miles away; but that was nothing for the average motor-car. And Philip would not know till he got there, seeing that Lottie Lane's name was on the programme. He would never have expected——

The curtain came down at last amidst thunders of applause. The Marston House company had surpassed themselves. There were tears in Mabel Heywood's eyes as she turned to Leatham.

"I have never seen anything finer," she said. "And your wife was splendid—splendid! Actually I didn't know that she was performing here this evening."

"Neither did I," Leatham said. "Didn't somebody say that she was taking Miss Lane's part at the last moment? I suppose I had better go and congratulate her. It would look rather strange if I didn't add my leaf to the rest of the laurel crown."

Leatham spoke with a lightness he was far from feeling. He was getting over the dazed feeling, and he began to see the clear daylight at last. It was some time before he found himself alone with Hilda. She looked at him with a smile that sparkled, with eyes moist and unsteady.

"Have you learnt anything to-night?" she asked, mutinously.

"I have learnt a good deal during the past year," Leatham said. "Would you mind walking with me as far as the little conservatory beyond the library? There is nobody there; in fact, I looked to see. Hilda, it seems to me that I have been incredibly foolish."

"When did you imagine that you could write a short story?" she asked.

"Oh, I understand. I've puzzled it all out. Dane based his play on that miserable effort of mine. Making you the heroine and giving you a chance to justify yourself was his idea, I suppose. But why, oh! why didn't you tell me?"

"My dear Philip, you never gave me the chance. You jumped to the conclusion that I was in love with Archie Mead. The poor boy did fancy that he was in love with me at the time; but he really cared for Ada Grace. It was her letter that I was sending on to him because her people were dead against the match. And if I did kiss him, and you saw it, why, it was only a kiss of congratulation. You never made the slightest allowance for the artistic temperament, Phil, and if you had not written that story and come here to-night we should have drifted apart for all time. Oh! my dear boy, if I had not loved you as I did, do you suppose that I should have given up the stage? Ah! you don't know what the feeling is. Why, I convinced even you to-night; I could see that by your face. And when you come to learn——"

"My dear Hilda, I have learnt many things the last year. I have learnt that there are two sides to every question. I daresay all these people know——"

"They know nothing. Dane may guess; but he is discreet and human. If you still care for me——"

"My dearest," Leatham said, hoarsely, "I shall always care! I have been the most miserable fool in the world. And I might have given you a chance to—to——"

"Act," Hilda said, unsteadily. "But my pride was too deeply touched for that. And, besides, I was not acting to-night. It was real, real, real!"

Her hands flitted out to him, and he caught her to his breast.

"Always act like that, darling," he whispered, as he kissed her. "Make it real to me, remembering after that I am a poor, dull creature. And I shall understand now. And—and, dearest, what a Christmas!"<</p>