THE big man stood winking and blinking in the sunshine. He might have been suffering from some hard-fought emotion, or just drawing back from the gates of a wasting illness. As a matter of fact, he was fresh from the gates of a gaol.

It all came back to him now, and the wiry threads of his full grey beard quivered. Was it four weeks or four years ago that he had lounged in the well of a whitewashed room and vaguely heard himself described as 'the Prisoner'? He could see the three sleek, well-groomed old gentlemen opposite him called 'the Bench'; he had wondered vaguely over the pink clearness of their cheeks and the amazing glossiness of their linen.

He hadn't done much; indeed, he and his 'pals' regarded the matter more or less in the light of a joke. There were eight thousand navvies, more or less, up in the 'Vale of Sweet Waters,' on that big Midland Water Supply Scheme—eight thousand men generally thirsty, and surely there was no great harm in the importation of a few kilderkins of muddy ale and a few gallons of raucous whisky. And if he, Long David, did make a modicum of profit on the transaction, why, it only covered the loss of glasses and mugs reduced to component parts what time the roysterers chose, to add to the doctor's account and the gaiety of nations. So long. Dave smiled and jingled the two 'quid' in his pocket—the usual penalty of shebeening—and hoped those pink-gilled Solons would hurry over the matter.

But they didn't. They took a serious view of the case and their own responsibility. There had been a good deal of illicit liquor-dealing amongst the huts. The prisoner must know that he was infringing the law; also he had used threats to Mr. Daniel Rhys, the smart local Excise officer who had so successfully brought him to book. The Bench were going to be lenient, yet firm. One month's imprisonment.

"One month's imprisonment!" He had never done anything wrong before; he had never robbed anyone of a farthing. Shebeening was mere sport, no worse than the predatory visits of a schoolboy to an apple-orchard. Besides, he had a little girl in Penymont Cottage Hospital. Couldn't he—

Well, it was all over now. The man who had lived in the open air all his life was back in the streets of Penymont again. He was wondering vaguely how he had lived through it all. As he looked down the narrow, white-washed street glittering in the sunshine, there was a hard, murderous lump in his heart. He had money in his pocket; the sign of the 'Oxford Arms' creaked invitingly, but he did not move. Then from the side street leading up to the hills came a procession.

There were some forty men altogether; big, reckless fellows, strapped as to the knee, with open-throated woollen shirts and caps of peculiarly villainous cut. They had come down from the hills to welcome Long Dave back again, to protest against the atrocity of his sentence. With the recollection of by-gone 'sprees' fresh in their mind, they could do no less. Gipsy and Dandy headed the deputation, the others glancing obliquely from the herd to the 'Oxford Arms.' Gipsy's big earrings flashed in the sunshine, the Dandy's unspeakable Newgate curl shed a halo over the proceedings.

"Well, old man," Gipsy cried cheerfully. "What O!"

"'Ow's the kid?" Dave asked sullenly and without the slightest apparent emotion.

"Spiffin'!" Dandy remarked. "Come to herself in the 'orspital 'ere same day as you was—was—well, it don't make no odds. Maddy's all right. Seems as she wandered away and got lost. Fell into a 'ole, she did. Some chap found her and brought her to the 'orspital. And never better than she is to-day. And as to yourself, Dave, why—"

"Come and 'ave a drop," Dave said shortly. "An' if you chaps is to keep friends along o' me, don't you go for to mention yonder place again."

"I knows what the feelin' is," Dandy said sympathetically. "Sorter 'ollowness in the pit of the stomach, first of all. Then you grows defiant—"

"Will you stow your jaw?" Dave cried furiously. "I put two quid in my pocket comin' down 'ere, to square the beaks, and I'm going to spend it. Come along."

The deputation yielded gracefully, no factious dissent marring the harmony of the proceedings. They flooded the big stone-flagged kitchen of the 'Oxford Arms,' they kept a sullen, and not too willing, landlord busy for some time. For Rees Thomas liked not the wild hordes from the hills—they scared his regular customers away, and during their rare visits the mortality of the crockery was enormous.

Into the midst of the fragrant group, rolling presently over the village street, there came a little dapper man in rusty black, a red-headed, foxy-eyed individual, with a fringe of rusty beard round his chin. His clean-shaven lips were shrewd and kindly, his slight frame suggested a deal of wiry strength. He was dressed in solemn black, a prehistoric top-hat rested on his head. A howl of derision greeted him.

This was no other than Daniel Rhys, the alert little Excise officer who had broken up so many happy little shebeens up yonder amongst the hills. Usually he had no lack of vituperative repartee, but he was fresh now from a meeting of chapel deacons, and he would fain have passed on in the brown study of contemptuous preoccupation.

"Lor'! what feet some people 'as!" Dandy said admiringly. "Just what I expected."

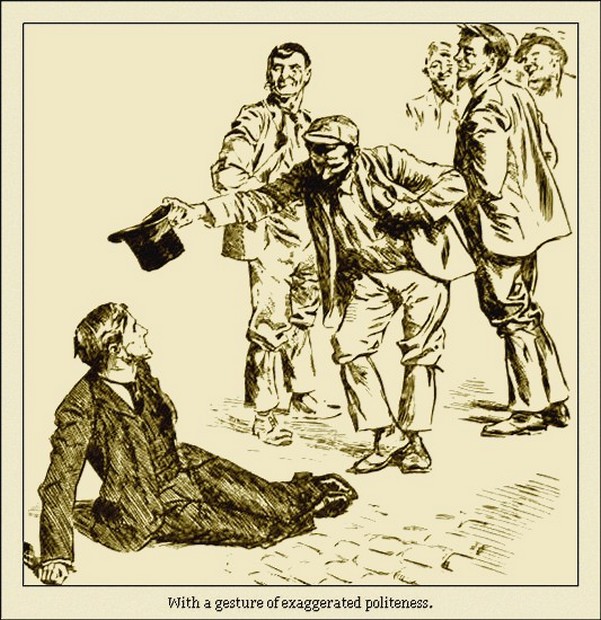

Mr. Rhys sprawled in the gutter as Dandy dexterously tripped him up, whilst Gipsy restored the ancient silk hat with a gesture of exaggerated politeness. Personal courage and cat-like sagacity ranked high amongst Rhys's virtues, but it was no time for a generous display of these attributes.

"Yess, you are a nice lot, whatever," Rhys said in the staccato tones of all true Llewellyns. "And I have not done with you yet—oh, no, indeed, look you. You hear that, Long David?"

Long David did hear it, and a sudden blind, unreasoning passion filled him. He stepped slowly forward as Rhys struggled to his feet and smote him heavily on the lips. Had the little man not been slightly off his balance, the blow might have been serious.

"Come out of it," Gipsy said anxiously. "I'm all for fun, and I ain't too proud to pay for it. But when it comes to a little lot 'without the orption,' I ain't on."

Rhys rose, slowly mopping his mouth as he did so. There was a deep crimson stain on his handkerchief as he removed it from his lips. Just for a moment a certain melancholy hung over the deputation. Rhys forced a smile to his lips.

"It's a day of atonement for us, yess," he said. There was just a suggestion of fanaticism about him. One often sees it in Welsh religious zealots. "A day for forgiveness. A kiss for a blow, look you. But there are other days. Long David, and we shall meet again, yess, sure."

"Aye, aye," Dave growled in his beard. "Any night you like. And there's more of the stuff where the other came from, and other ways o' hidin' it. If you ketch me out next time, you're free and welcome to do it, and no ill feelin' o' my side. But if I ketches you doggin' round o' nights, I'll kill you, sure."

He meant it, he meant every word that he said. And nobody knew that better than Daniel Rhys, who had lost a colleague not so very long ago. It was so easy for a belated officer to fall over one of those stone quarries in the dark, so difficult to prove that the disaster had not been absolutely accidental.

Rhys fell back from the ring of scowling faces around him, all of them looking murder, with the possible exception of Gipsy and Dandy. This keen warfare was all very well so long as a sovereign or two met the case, but gaol was a different matter. It would go ill with Rhys if he fell into the hands of these men on one of his midnight rambles, and well he knew it. The strong admixture of pluck and religious fanaticism that went largely to his making up blazed within him.

"I could get you another month for that, iss, sure," he said. "But no, my friend. You defy me! We shall see. Now you get out of my way, whatever."

Not without dignity he pushed his way through the jeering, soil-stained crowd.

Rees Thomas, discreetly irate, beckoned him into the shelter of the 'Oxford Arms.' With a final howl of derision the deputation went off, singing patriotic or other less desirable snatches, in the direction of the hills, where the claiming of the sweet waters went on night and day.

"A drop of brandy, Daniel Rhys?" the landlord suggested hospitably.

"Indeed, and I don't mind if I do, Rees Thomas," the Excise officer replied. "I never had no nastier blow than that, whatever."

"Blackguards!" said the other. "Why for you not tell him as it was you who picked up his little girl in the hills and brought her to the cottage hospital here, and your shoulder dislocated into the bargain? Why you no tell him that, Daniel Rhys?"

Rhys saw no reason for going into psychological details. As a matter of fact, he had stumbled over Long David's wild little slip of a girl up in the hills when nosing out shebeens. He had got out of a tight corner himself at the expense of a big jump and a dislocated shoulder-blade; but this had not prevented him shutting his teeth together and bringing the starved and unconscious child all the way down to Penymont, after which he and his assistant had gone back two days later and caught Long Dave 'in flagrante delicto.'

"He didn't know that I had anything to do with it, Rees Thomas," he muttered.

"Then you should have told him, yess, sure. Who saved that child's life, look you? Why, Daniel Rhys. And what does that blackguard do? Knock you in the mouth."

"But how could he know?" Rhys insisted.

The landlord, didactic—after the manner of his kind—could not see what that had to do with the nice ethics of the question. Nor could he understand that Rhys had a fairly high code of honour of his own; also he had an ambition to make his name a terror in the hills. Long Dave had challenged him again, and they should start fair. The child must not handicap either party to the fray.

"You are a great stupid donkey, whatever," said the aggrieved landlord. "And it's my belief as the girl is as bad as her father, look you."

Daniel Rhys finished up his brandy and went out thoughtfully. Unconsciously enough, Rees Thomas had let a flood of light into a dark corner. Perhaps, after all, that quick-witted, dark-eyed child had her uses. Also it was strange that he should have caught Dave red-handed after the child was out of the way, although for the last year his efforts in the same direction had been futile. On the whole, Rhys came to the conclusion that it was greatly to his advantage that child Maddy should know nothing as to the identity of the individual who had rendered her such timely assistance.

Long Dave's welcome back to the huts had done much to wash the prison flavour from his mouth. He was still silent and sulky, inclined to brood over what he called his wrongs, and a little too prone to harbour bitter feelings of revenge against Daniel Rhys, who, after all, was doing no more than earn the stipend paid him by a grateful country. If the conflicting elements came together again, the comedy might flame into tragedy of the most lurid kind.

Long Dave tramped up from the big wooden town at Cumguilt to his own lonely hut up on a spur of the hillsides. In many ways it was an ideal spot for the exciting and slightly remunerative sport of shebeening. In the first place, there were high ravines on either side of the long, flat, artificial tableland, a tunnel at the far end, and a sloping path, at the foot of which lay a cluster of huts, from whence ready and sinewy aid could be commanded should the authorities make anything like a raid in force.

There was a thoughtful grin on Dave's dark face as he entered the hut. A lean-to shed full of tools was on one side. By extending the hut a foot or so a long gut of big water pipes could be covered—at least, so far as a section of it was concerned. Later on these pipes would convey water to the thirsting Midlanders; at the present moment they were naturally empty, and the cover of a manhole stood open. By a little ingenious alteration the manhole might be taken into the hut—or outbuilding, rather—and here, ready made, was a natural hiding-place for barrels and bottles, beyond the ken of the sharpest Revenue officer of them all. For the first time for a whole month Dave's face cleared.

He sat in his chair chuckling, secure in the knowledge that he would make Daniel Rhys a walking derision amongst the hills, until the door opened and a child looked in. She danced into the room with a glad cry, her dark, gipsy eyes gleamed, her feet flashed as if the blood in her veins were quicksilver. A wild, eager, alert child, black as the night and cunning as the fox. A queer, Miss-like little elf, loyal to her friends, and hating her enemies with a passionate whole-heartedness.

"Daddy!" she cried. "Daddy, daddy!"

Dave's grim face relaxed still further. He forgot all about his wrongs; the prison taint seemed to slip from his broad shoulders; something seemed to soften at his heart and melt away. He lifted the child from her feet and held her at arm's length.

"So you are all right again?" he growled.

"Oh! I got better directly. Of course, you could not come to see me, because—"

She paused, with the subtle instinct of her sex for the word that wounds.

"And the other man, the good man who found me, didn't come neither," she added quickly.

Dave nodded abstractedly. He was not in the mood at present to entertain anything like a large measure of gratitude to abstract humanity. Under ordinary circumstances he would have sought out Maddy's friend and made a friend of him.

"Didn't do more than say his name was Foxy," Maddy said dolefully.

Dave nodded again. Not for a moment did he connect the aforesaid Foxy with Daniel Rhys. On the other hand, Rhys had kept out of the way simply because Maddy was Dave's girl. The little man was exceedingly fond of children—perhaps because he had none of his own—but he wanted a fair field and no favour.

"I guess you's been very unhappy, Daddy," the child said suddenly.

She saw the big man's shoulders heave; she saw the strained agony of his eyes. Very slowly he took the girl upon his knees.

"Nobody's goin' to know nothin' 'bout that," he said. "I'd done no 'arm—never did a chap out of nout. An' a month—a month long o' thieves and the like. Don't you never mention it; never let me 'ear of it again. An' if the man as I've got to thank for this ever comes here some night. .. an' he'll come, too—"

Maddy caught the lurid glare in her father's eye, the dull glare she had seen in the eyes of poor jealous Dick Martin the night he killed his wife. And they had taken Martin away and hanged him.

Maddy was terribly frightened, though she had too much tact to say so. A queer, lonely, imaginative child who lived quite alone, she knew and understood enough to astonish Dave if he could have seen into her mind.

"Nothing happens to you whilst I keep watch," she said.

Dave nodded again, this time more cheerfully. He kept clear of his mates for the rest of the day, and by nightfall had completed the annexe to his hut. Two days later and his store of excisable liquor bloomed again; the manhole held it safe enough, though Rhys's subordinates brought news to the effect that a couple of barrels and a can of suspicious shape had been delivered at Long David's hut over the hills from Rhyader. The little man's foxy curtain of whisker bristled as he went gaily off in pursuit of a search-warrant.

But Sir Pryce Llewellyn would have none of it. He flatly declined to produce the necessary document, without which no search could be made, unless he had a sworn information. For the police to raid a shebeen and capture the culprits red-handed was one thing—to issue a search-warrant on mere assumption was another. Sir Pryce had great respect for the majesty of the law, also his dignity still rasped under the recollection of the one time when he had appeared in the pillory of a certain weekly paper.

"You ought to know better, Rhys," he said. "Can you swear an information?"

Daniel was silent. He was sure of his ground, but he could not swear an information. He set his teeth together; his little eyes gleamed.

"Not this morning," he said, "but to-morrow, Sir Pryce. By to-morrow I shall be able to do it, look you. I shall know all about it, iss, sure."

Whereupon the Excise officer departed, and Sir Pryce retired grumblingly to Lady Llewellyn with the prophecy that Rhys would get his neck broken some night, and further desired to know how a man could be expected to keep his pheasants if the authorities were always harrying the navvies over every cask of beer they swallowed.

But Rhys had another point of view entirely. Seven o'clock the same evening saw him creeping up the valley in the direction of Cefro Tunnel, in the neck of which Dave's hut was situated. Because he fully appreciated the danger, Rhys was alone. His assistant Jenkins was a good man and plucky, but his tongue was loose and the gift of silence had been denied him.

There was only one way up to the hut, as Rhys well knew, and consequently there was only one way of retreat in case of disaster. And Long Dave would assuredly keep his word. Rhys was taking his life in both hands, and he knew it.

It was not a dark night, with a ragged moon showing now and again behind a jagged, racing cloud. Down below it was all still enough—so still that Rhys could hear the sound of voices from the cluster of huts at the end of the cutting. Presently these huts would each yield a man or two, who would join Dave and partake of his illicit hospitality. Dandy and Gipsy and Doolan and Gammon all had their habitation there, all of them were known to Rhys. If he could reach the scrub outside Dave's hut and lie there, why, the search-warrant would come as a matter of course. Rhys had been there before—invariably too late. Some sort of a signal had heralded his coming, and what the signal was had hitherto been a puzzle to Rhys. Now he had a pretty shrewd notion that he had solved the problem.

He pushed his way cautiously along, creeping like a fox that he was until he came to the first fringe of dusty blackberry bushes. Behind he could hear something moving. There was just the faint suggestion of a whistle, almost inaudible as yet, but rising.

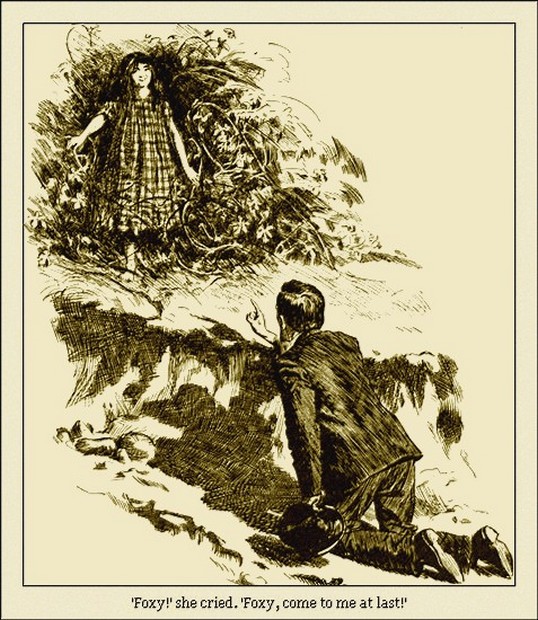

"Maddy!" Rhys whispered. "Maddy, are you there?"

The bushes parted with a sudden swish, and Maddy stood delightfully dazed. She had not the slightest idea that here was the enemy; indeed, her notions as to the utility or end of her sentinel's duty were hazy in the extreme.

"Foxy!" she cried. "Foxy come to me at last!"

It was not nice work, and rounded off badly with the fierce Nonconformist conscience which was a second nature; but the sophistical juggling of the theological mind was equal to the occasion.

"Then you haven't forgotten me?" he asked sheepishly.

Maddy's answer was practical and demonstrative. In the excess of her emotions she would fain have carried Rhys off at once to receive her father's warmest expression of gratitude. But Rhys was no chapel deacon for nothing, and he had his duty before his eyes. At the same time he was sufficiently human to wish that he hadn't come.

"Presently, presently," he remarked. "Plenty of time, whatever. And you won't leave here, my child?"

In Maddy's joyful emotion it never occurred to her to wonder whence Rhys had derived his local knowledge. But it did occur to him that he might gain all he desired without a primitive eclipse of himself in Maddy's eyes. Nobody could polish a drab lie into a pure white truth better than Rhys, but he shrank now from the child's gaze with an uncomfortable pricking of his cheeks.

"You just stay where you are for a minute," he said hurriedly, "because I want a word with your father alone. Then I'll come back presently, you see."

He departed with a mysterious nod, which to a more sophisticated mind would have suggested a shilling box of chocolates at the least. An occasional predatory lump of sugar was the extent of Maddy's education in the saccharine field. Still, she had imagination and anticipation.

Rhys crept on, feeling now that the ground was clear. If he could only look into the hut, only see the preparations made for the coming feast of reason and flow of soul, he would be satisfied. After that the search-warrant would follow as a matter of course, and then—

He had forgotten all about Maddy by this time. An exceedingly convenient cloud—no doubt designed by Providence for the especial purpose—had trailed darkly over the moon, a faint yellow light picked out the doorway and windows of the hut, from within came the dull stone clink of pottery, then the popping of a cork. Evidently Long Dave was going to celebrate his freedom with some style.

But the clink of the mug and the thud of the cork were by no means evidence in support of a search-warrant on the distinguished authority of Stone's 'Justice's Manual.' Moreover, Rhys was a Welshman to his finger-tips, and Eve was popularly supposed to be a Welshwoman. Rhys advanced cautiously and lifted the latch.

He looked in. He saw a long table and two lamps thereon. A half firkin of beer rested on the table, flanked by a dozen mugs and a tempting array of bottles. Then a shadow fell across the doorway, and an arm like a pillar of stone grasped Rhys by the neck and dragged him as a cork into the room.

"You dirty dog!" Dave said hoarsely. "So I've got your neck under my fist at last!"

The loquacity of his race was absent in Rhys at that moment. He was not so much keeping his breath to cool his porridge as to save his bacon. One eel-like motion of his head had sufficed to show him murder standing stark in Long Dave's two eyes.

Under any circumstances his feet had been planted amongst scorpions, but here he had caught David in flagrante delicto again, and, prosaically stated, that meant six months.

"What's your game, whatever?" Rhys gasped.

"I'm going to kill you," Dave replied. He spoke in a dull, mechanical way, yet with the air of a man after long deliberation. "I can swear that nobody saw you come here, and nobody will see you go. There's a deep pit full of water at the back of the cutting that they're filling up. This day week you'll be under forty feet of stone and shingle. D'ye hear?"

Rhys intimated by a gesture that he was alive to the situation. He had been more than once threatened with violence; indeed, he bore more than one honourable scar on his body; but this was a different matter altogether. With a sudden writhe and twist he slipped from Dave's grip and scrambled on hands and knees for the door. As Dave caught one foot the other struck him full in the mouth. With a stifled curse the big man drew Rhys to him and smote his head with a thud on the floor. For the next few minutes mundane affairs became as a dream to the unconscious Rhys.

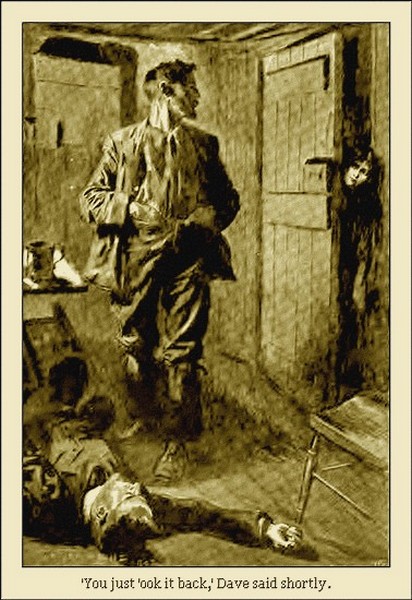

Dave rose slowly with an ugly smile on his torn lip. He crossed over to the door of the hut and whistled. Immediately the answer came.

"Go down to the huts and bring the lads up here, Maddy," Dave gurgled. "Tell 'em as there ain't any danger."

Maddy flew off presumedly, for no further sound of her voice came. Dave was standing over the prostrate body of his foe when Maddy looked in with sharp, beady eyes.

"You just 'ook it back," Dave said shortly.

"But you told me there was no danger," said Maddy. "And seeing that Foxy was here, and that you must have finished your business—Ah, ah! what have you done to him? What have you been and gone and done to my poor Foxy, you bad old father?"

"Oh!" Dave asked blankly. "What d'ye call 'im?"

"Why, Foxy, of course. The man who found me starvin' and dyin' yonder; the man as carried me all the way down to Penymont, and 'im with a dislikated shoulder all the time. And you've gone and killed my Foxy."

She bent over the prostrate body and wiped the bleeding face. Then she poured some illicit whisky into a mug and forced it between Foxy's lips. She did not feel faint or flurried, nor was she in the least timorous or afraid. She had seen too much death and disaster for that; had seen the strong man bleeding and quivering, death in its most repulsive form.. .. Rhys opened his eyes with a desire to know where he was.

"Oh! you're safe enough, dear," she said, with her arms round the prostrate man's neck. "I expect Daddy took you for one of them Excise men."

"Did," Dave growled. "An' that's a (lurid) fact."

"But you see it was all a mistake, Foxy," Maddy went on.

Dave looked grimly uncomfortable. All the passionate anger had died out of his heart. He stood leaning sullenly against the table, big and powerful in the lamplight, whilst Maddy's little black eyes seemed to be picking up all the broken threads of the story.

"Why didn't you tell me about it afore?" Dave asked.

"Didn't mean to," Rhys snapped, his curtain of red beard quivering. "I'm as good a man as you any day, look you, Long Dave. And I wanted to meet you in fair fight, whatever. Come to tell you what I did for the child, and where are you? Nowhere. I beat you every time, and your hands is tied for thinking of the child."

"And you're the man what sent Daddy to—Oh, Foxy! how could you?"

Rhys shrugged his shoulders. There was nothing to be said, for the simple reason that explanation was impossible. The child was too young to understand, and, being a girl, naturally had the lack of logical sequence that renders the sex so charming. Also his duty lay plainly before him. He ought to have escaped in the confusion, and he ought to have gone down to Penymont and sworn an information against Dave without delay. As a matter of fact, he did nothing of the kind; instead, he stood there looking so like a fool that his subordinate Jenkins would have hardly recognised him. Was ever a clean conscience in so sorry a plight before? It was Maddy who broke the strained silence.

"You're not going to take Daddy to—?" she asked.

"If he wants to," said Dave, with an effort that caused the big drops to stand out on him, "I'm ready to go, and be hanged to him!"

"Lord!" Rhys gasped. "Here's a pretty state of things, whatever! If I go away—"

"You can't," Dave said suddenly. "The boys is comin' up the cutting. They'd have your blood; they'd never trust you, not on your oath. No mor'n if you were a Welsh policeman."

Outside the sounds of ribald mirth came nearer. Gipsy was leading a song. Dandy and the rest were roaring over the chorus. Rhys stood panting shortly with his back to the wall, not in the least afraid and yet horribly hysterical. Maddy was watching him with eyes that filled her face with a wild black blaze. She saw the danger now.

There was no escape. And there were men outside who were ready for anything. Moreover, Daniel Rhys was the only man they feared. They would have only been too pleased to take the matter of retribution out of Dave's hands. Once let Rhys escape, and there would be another visit to Penymont Petty Sessions, and the gaol for all of them.

"Tell them Foxy isn't going to do them any harm," Maddy suggested.

Dave fairly laughed aloud. Even Rhys smiled faintly. There was deadly war between himself and the tribesmen, and nothing less mundane than an archangel would have convinced them to the contrary. The humour of the situation was not lost upon David.

"Now you're going to enjoy yourself," he said grimly.

Rhys set his teeth tightly together. The ragged curtain under his chin trembled. There was no longer any question as to the genuinely hospitable intentions of his host. It was bitter to be compelled to shield himself behind the child; but life was sweet, even to a man with the snug theology of Daniel Rhys.

"There's some place I can hide, look you?" he suggested eagerly.

Maddy pulled at his sleeve. Her dark eyes were blazing fiercely. There was a tiny room at the back of the hut which was all her very own. Into this she fairly bundled Rhys and closed the door behind him as the first of the roysterers burst into the hut. They came, eager and excited, greasy and redolent of the soil, filling the hut with that faint, sour smell that goes to the midweek toiler, who literally earns his bread in the sweat of his brow. A hard, reckless, bitter lot, most of them with a past, and all of them anarchists in embryo. If the whole pack of them could have been wiped off the face of the hills, the head ganger would have been frankly grateful.

"Where is 'e?" the foremost hand cried. "We tumbled to your message, Dave."

The speaker rocked to and fro with exquisite enjoyment, tempered with a sudden fear as he looked round the hut. The rest of them laughed loudly; they were in a playful mood—the playfulness of the cat about to spring. Dandy stood a trifle heavy and sullen in the doorway; over his shoulder peered Gipsy's slightly anxious face. If murder was to be done, he was prepared to accept his share of the responsibility. But as a matter of fact, Gipsy was here for peace.

"Just you trot 'im out," another suggested.

"I dun no what you mean," Long Dave said stolidly. "'Oo d'yer mean?"

"Why, Rhys, of course. Come, where be you a-hidin' of 'im?"

Dave shook his head solemnly. Beyond the ring of grimy faces he caught Gipsy's eye. The latter winked slightly, and Dave's soul was uplifted. As ill luck would have it, at this same moment Maddy came into the glare of the lamps. One of the roysterers caught her up and set her on his shoulder.

"Who're you got in yer bedroom, Maddy?" he asked. It was a pure venture, but the child was taken off her guard for the moment.

"Only Foxy," she said innocently. "Nobody else."

It was a critical moment. 'Foxy' conveyed little to the visitors. Long Dave looked imploringly at Gipsy. If those fellows only knew for certain who was listening to them, Rhys's end was at hand. And here was all the damning evidence on the table. The little man with the big earrings rose to the occasion.

"I seen the dog this mornin'," he said. "Foxy 'ull make a good 'un, if you don't go for to give him too much meat, Maddy."

"That's just what I tell her," Dave remarked wisely. "Gels allus spiles their dogs that way." With rare inspiration Maddy said nothing. Something told her that her beloved Foxy was in danger, or why should Gipsy pretend that he was a dog? And she had the most profound respect for Gipsy's many-sidedness.

"Dorg," came a voice from the edge of the pack. "A terrier, most like. Let's see 'im. I 'ad a bull terrier wunst as killed three score rats in—"

"This ain't no terrier," Gipsy retorted contemptuously. His foot shot out and caught Dandy fairly on the shin. That individual took the hint without the tremor of a muscle. "It's one of them poodles like Mr. Marrin the engineer's wife's got. Maddy took a fancy to one of them, and I nicked 'im."

"What's the game?" Dandy whispered hoarsely.

"Rhys is in yonder," the Gipsy replied; "and Dave's a-shieldin' 'im for purposes of 'is own. If we don't stop this little manoeuvre, it's murder will be the matter. An' I ain't goin' to 'ave my neck stretched if I can 'elp it—"

"An' there ain't no dorg?" Dandy asked.

"No, nor a cat, neither. Chuck it, Bill! 'Oo wants to see a black doormat out of a bloomin' circus? If it was a bull terrier, now! Leave the girl alone."

Maddy slipped off and Gipsy breathed easier. The first speaker refused to reface his opinions so freely.

"I dunno as I shouldn't like a dorg like that for my kid," he said. "What colour, Gipsy?"

"Black as yer 'at," Gipsy said, with rising irritation. "Got to be painful sober to know which is the business end of 'im. Wicious little beggar, too. Got me through the finger afore I could say—"

"I should like to see the dorg as 'ud bite me," the first man remarked. "I 'ad a Airedale—"

"Oh! sit down!" Dave roared. "On the floor anywhere. 'Elp yourselves."

A liberal construction was placed upon the suggestion, and the dog subject was forgotten. A thick cloud of pungent blue smoke lay like a curtain across the table. The uneasy feeling that the proceedings might be interrupted by the arrival of the authorities added pungency to the tobacco that already possessed a reeking zest of its own. As every man filled up his glass or his mug he dropped twopence or threepence in a bowl on the table. Then the thin, wiry man who had opened the proceedings absorbed a second whisky before he spoke again. He had the air of a man who has something on his mind.

"I quite understood as you'd got 'im," he said thoughtfully.

"I ain't got 'im, and, what's more, I ain't goin' to get 'im," Dave growled. "You can 'ave what drinks you like, boys, an' all the coppers is goin' to the 'orspital fund. After all, this 'ere little Rhys ain't doin' no more than his dooty."

"I'd like to 'ear that again," the malcontent said politely.

"I'll ram it down your throat if you like," Dave growled hospitably. "Rhys 'as got to get his livin' same as you and I. 'E ain't going to injure me to-night, and I ain't goin' to injure him after to-night."

"Clean off 'is bloomin' chump," said the misanthrope sorrowfully.

Mugs stood neglected on the table, pipes were suspended in mid-air. There was a half-shamed flush over Dave's face, but his eyes were steady. Gipsy was watching him with a flattering interest. This was one of the comedies that he loved so well.

"We're fools!" Dave declared. "Just fools. Why do we do this 'ere sort of thing when we can get better an' cheaper stuff at the canteen? Why, because it's agin' the law. An' it's Rhys's duty to see the law is kep'."

"I've knowed gaol affect a bloke's 'ead like that afore," said the discontented one.

"Maybe as you've found good points in Rhys?" Dandy suggested.

Dave brought his fist down on the table to a dancing jig of mugs and glasses.

"I 'ave," he cried. "He came 'ere to-night, and—and I let 'im go." It suddenly flashed across his mind that Rhys would appreciate this way out of the difficulty better than the dramatic production of his person. It would be much more likely to fit in with his sense of duty. "Why did I let him go? Because I found out as he was the man what carried little Maddy down to the 'orspital at Penymont. An' 'im with a damaged shoulder all the time. And why didn't 'e tell me? Because he wanted to beat me without a handicap."

"Got the feelings of a real sportsman," said Gipsy.

The misanthrope shook his head sorrowfully, but the feelings of the meeting were evidently against him. Gipsy had gone over already to the enemy, and Gipsy knew perfectly well who was in the little bedroom listening to every word of the proceedings. And, moreover, Gipsy was grateful to the man whose modest courage had averted an ugly tragedy.

"I don't want," said the misanthrope slowly, "to say as Dave's a coward—"

There was a sudden uproar, terminating with the violent opening of the door and a dissolving view of the speaker disappearing in a paste of red clay. Then there was a distant rumbling of threats to be left darkly to the future, drowned by cheers for Dave and Daniel Rhys. Only a strong sense of fairness and decorum restrained Gipsy from dragging Rhys out into the fierce light of popular approbation. The jugs and bottles were empty at length, and the company, having no longer any rational or respectable excuse for staying, lurched heavily homeward. Gipsy and Dandy brought up the rear.

"Mean to say 'e was there all the time?" the latter asked unsteadily.

"Mean to say as 'e's there now," Gipsy responded.

"Good old Rhys!" Dandy remarked, and lapsed into gloomy silence.

* * * * *

Rhys stepped out, blinking his eyes. His gaze was scrupulously and steadily averted from the table where evidence of illicit traffic was thick as leaves in Vallambrosa. He held out a lean, sinewy hand, which Dave grasped largely and painfully. It was characteristic that neither man met the other's eye.

"I've—I've been wrong," Dave said shortly.

"But not in the future, whatever," Rhys replied. "I heard you say so, yess. And it's a good thing, for you are a good man, Long Dave."

"Never no more," Dave responded. "If it hadn't been for Maddy, I—"

He paused and Rhys nodded. He knew all about that. Then he picked the blazing-eyed Maddy up and kissed her. His wonted loquacity had suddenly failed him. He was glad, and yet sorry, as he walked along—glad to have made a friend of the dangerous enemy, sorry because he was going to fail grossly in his duty.

"Call yourself an honest man, whatever?" he muttered, with the dim lights of Penymont in his eyes. "To think that I should pass a night in a shebeen, and the police none the wiser! But what can I do more than plead for this miserable sinner, and leave the rest to Providence, whatever?"

With which comfortable shifting of responsibility, Rhys went to bed untroubled by any odd thorns on the rose of his tender conscience.