THERE was a sudden rush of figures, the suggestion of a badly acted quarrel, the gleam of a revolver-barrel or two, and the crowd round the roulette-table realised that a bold attempt to rob the bank was in progress. To add to the dramatic swiftness of it, someone in the conspiracy had cut off the electric light, so that the greater part of the big saloon was in darkness.

The thing had come so unexpectedly that the croupier, old and hard in the ways of the wicked, could only bend over his bank and hug the shining metal there, much as a hen squats over her chickens when a hawk is overhead. An arm shot out of the half-gloom, and the croupier, his head laid open by a heavy blow from a loaded stick, ceased to take any further interest in the proceedings, snoring like a pig. Just for a moment it looked as if the amazing audacity of the proceedings were going to be crowned with success. Two or three revolver-shots rang out in quick succession, women of all kinds clung together and screamed, a shrill whistle trilled somewhere in the distance.

All this about half past six on a rather dark February evening, the hour when the saloons of Monte Carlo are not at their fullest, and an attack like this would be most likely to succeed. The three Englishmen who had just come in looked at one another, doubtful of what to do next. They were not in the least frightened; they would have been capable of anything, had only somebody given them the lead. The lead came unexpectedly from a man who was struggling with a tangled knot of humanity on the floor.

"Hi, there, you look a likely lot," he gasped. "Trip up that chap with the red hair. Get him down and jump on him. I can manage the rest."

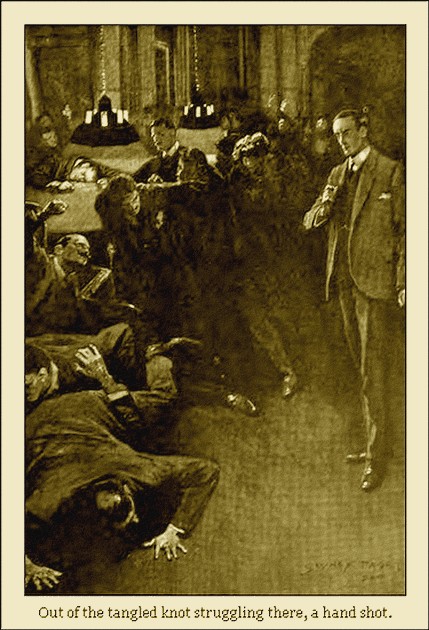

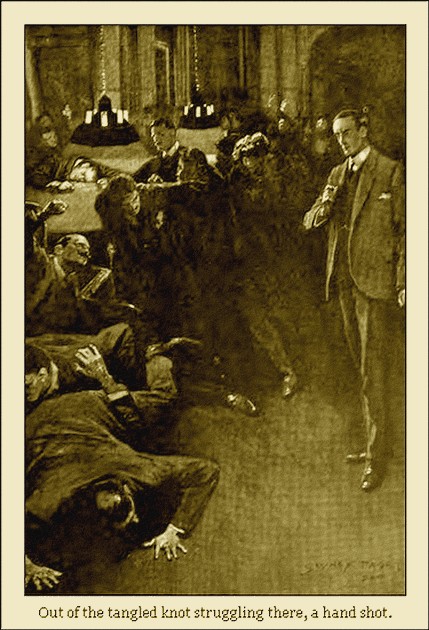

Two of the Englishmen moved to the attack. There were no more revolver-shots, seeing that the noise of conflict was likely to do more harm than good. The third Englishman did not move. He was slighter than his companions, and though his mouth was hard and firm almost to the verge of cruelty, he was still palpably in the grip of some lingering illness. He seemed to be fascinated, too, by a queer sight that met his gaze from the floor. Out of the tangled knot struggling there, a hand shot—a nervous, sinewy hand, with a peculiar scar in the shape of a crucifix upon it.

"Come on, Duckworth," one of the other men called. "Twist that fellow's arm behind him."

But the man called Duckworth never stirred. He was like one who sees a ghost. The sinewy hand with the scar upon it was no longer visible, for it had got back to work again; the eager watcher could not discover what body the limb in question belonged to. He was still standing in the same dazed way when the lights came up again, and the saloon filled with men in uniform. The raid was over almost as soon as it had begun, there was a buzz of excited conversation, and pale, fair cheeks began to draw blood again. The other two Englishmen were still breathless from the struggle.

"An American gang," one of them panted. "Headed by a chap who has a bad reputation on two continents. By Jove! that fellow would have made a big name as a soldier. Pretty mad thing to try, all the same. Heart worrying you again, Duckworth?"

"It wasn't quite that, Herries," Duckworth stammered. "Of course, the excitement was trying to anybody in my wretched state of health. After the adventurous life I have lived in America, a little thing like that could not hurt me. But in the middle of that struggle I had a shock that seemed to knock the breath out of my body."

"Saw something unpleasant, eh?" the third man asked. The other two were good average Englishmen of the better type—clean-lived, well-groomed, sportsmen both. "Sight of that croupier with his head cut open?"

"Croupiers are cheap enough," Duckworth said somewhat brutally. "It wasn't that, Gilroy. A hand shot up from the floor where those fellows were struggling—a brown hand, with a scar like a crucifix upon it—the hand, mind you!"

"You don't say so!" Gilroy cried. "Quite sure that you are not mistaken?"

"Perfectly certain," Duckworth replied. "There was the clean mark of the crucifix, exactly as you described it that night in Rome. My dear chap, it is impossible for two men to have a mark like that on the back of a hand. You can imagine the effect that the discovery had upon me, with my nerves in their present condition. That fellow has followed me here, he has got on my track again."

"You mean to say," Herries said slowly, "that the man in question—"

"Is looking for me to murder me. Yes, I do. He tried it in Rome, as Gilroy knows. But for a bit of luck I should have been killed in my bedroom at the Maremma Hotel. It is terrible to be tracked and followed by a merciless, murderous assassin like this. If I only knew the man by sight, if he would only come out in the day-light—"

Duckworth paused and shuddered. Yet he had a justly high reputation for courage.

"Well, anyway, you've got a chance to drag the ruffian into the open now," Herries said cheerfully. "You will be able to recognise your assailant in future. All you and Gilroy have to do is to go before the local police and swear an information—"

"But I tell you I am as much in the dark as ever," Duckworth protested. "Let us go over to Nice and dine at the Gordon Hotel—my nerves call for a private room. I saw the hand and the scar plainly enough, but in the struggle and the semi-darkness it was impossible to identify the particular body to which the hand belonged. All I know is that my enemy followed me here, and that I have had a fortunate warning of the fact."

The speaker looked like a man who has the fear of the rope about his neck. Herries was inclined to make light of the matter. All they had to do was to keep their eyes open for a man with a peculiar scar on the back of his right hand. Once they found him, it would be a very easy matter to hand him over to the authorities. Perhaps he was already in custody, perchance he was one of the gang of captured desperadoes.

"I don't think so," said Duckworth thoughtfully. "The scarred right hand seemed to be on the side of authority; anyway, he had a pretty good grip on the red-haired chap. But for the life of me I could make nothing of his face, or even the colour of his clothes."

"Bet you a fiver I find the chap before twenty-four hours have passed," Herries boasted. "If we buck up, we shall just catch the 7.5 train to Nice, where we will dine at the Gordon Hotel. And we'll humour old Duckworth with a private room."

The colour was creeping into Duckworth's pale cheeks again, his mouth had recovered its hard lines. Herries and Gilroy were old school and college chums, their 'people' were intimate, but of Duckworth neither of them knew much. He alluded to no past, beyond the time when he had gone to California, where he had made a fortune in the goldfields, and where he had met with many strange adventures. But his form was correct, he was well dressed, he gave very good dinners at a small house of his own in Hill Street, he always contrived to get the cream of the Scotch moors and the Norfolk partridge-shooting. A man like that forms a very desirable acquaintance in these days of semi-illiterate financiers and foreign magnates of doubtful origin. In their frank, short-sighted way, both Herries and Gilroy summed Duckworth up as a 'good sort; just a little close, you know, but a dashed good sort, take him all round.' It was the philosophy of the club and the smoking-room, so that Duckworth's position was assured.

He did not look particularly assured as he adjusted his dress-tie in front of the glass in his bedroom before joining the others at the Gordon Hotel. True, he was just getting the better of a most malignant attack of rheumatic fever, which had left his heart in a sad state, but that did not altogether account for his slackness to-night. His mind went back to that night in Rome, a little more than a year ago, when Gilroy had saved his life from the man with the scarred hand, the same man who was after him now. It came back to him that he had never quite satisfactorily explained to Gilroy why that mysterious and murderous attack had been made. He had said something about a revengeful madman who had some fancied grievance in connection with gold-mining and a disputed 'claim,' a man whose face he had never seen, and Gilroy was pleased to accept the explanation. Gilroy was a gentleman as well as a man of the world, and he had expressed no vulgar curiosity—there were doubled-down pages in the life of everybody, as he knew perfectly well.

The other two were waiting in the lounge of the hotel for Duckworth. Though the house was crowded, they had managed to get a private room, where dinner would be served in a few minutes—a room on the first floor, with a balcony looking out towards the sea. The crowd in the lounge was getting on Duckworth's frayed nerves.

"Let's go up to the room and sit in the balcony," he suggested. "We shall have just time to get through a cigarette there before dinner."

It was cool and fresh on the balcony, and the silence of it was soothing. Presently, from the dining-room came a clear, sharp voice demanding to know things, the apologetic whine of a waiter, and a peremptory order for somebody to go and fetch the manager.

"Some Johnnie trying to commandeer our room?" Herries suggested. "Come on, you chaps. I dare say it's one of those all-devouring Yankees."

A tall man with a beard stood before the fire, addressing the manager. He was perfectly dressed, and his manner seemed to be good. That he was annoyed about something was apparent from the expression of his face.

"If it is a mistake, then it is yours," he said. "I ordered this room this morning—I even arranged for those very flowers. It was settled with the head waiter. As I am a stranger here, I paid for the dinner in advance. The fact that my three friends have been detained in Paris makes no difference. This room is mine."

"But, m'sieur," the hotel proprietor protested, "as you are quite alone, and your friends are not arrived, and as the other gentlemen have ordered dinner here—"

"I am afraid we are out of court, sir," Herries said pleasantly. "We came from the balcony to dispossess you by force of arms, if necessary. But after what you say, we can only bow to the inevitable and resign ourselves to the table d'hote."

"Which is half over by this time, sir," the stranger said. "Moreover, the table d'hote dinner here is frequently open to criticism. Are there three of you?"

"There are three of us exactly," Herries said. "Let me introduce myself by name. This is my friend, Mr. Gilroy. Here also is my friend, Mr. Duckworth, who is an invalid. It was to please him that we engaged this room. But after your recent remark to the landlord, I am afraid that we must retire gracefully."

The stranger smiled and shook his head.

"My name is Harrington," he said—"a cosmopolitan at that. Let me make a suggestion to you. Why not dine here with me? I have ordered a special dinner for four, but my friends have been detained in Paris. You look like getting no dinner at all. Is the suggestion that you should be my guests too inconvenient to you?"

"It's deuced kind of you," Gilroy said warmly. It seemed to him that the metal rang true. "I am sure that my friend Duckworth will make no objection."

"Your friend Duckworth will be confoundedly glad of the opportunity," the latter said. "The suggestion was very kind and thoughtful of you, sir. It's a very odd thing, but I seem to have heard your voice before."

"Same idea occurred to me," Herries remarked. "By Jove, I've got it! Weren't you in the Casino to-night when the row was going on?"

"And didn't you ask us to lay hold of that red-headed chap?" Gilroy cried.

"You have guessed it," Harrington smiled. "Directly the dispute began, I tumbled to what was going to happen. When the first shot was fired, I felt certain of it. And I had some little grasp of the kind of reputation that that red-headed man enjoys. So I just dropped to the floor and clipped as many of the gang by the legs as possible. They were all on the top of me, and it was only now and then that I got a glimpse of anybody. Then I spotted you two gentlemen as being likely fellows in a fight, and I called to you."

"Where did you get to afterwards?" Gilroy asked.

"Oh, I was dragged off with the rest. The fools of police took me for one of the gang, and they were all for clapping me in durance vile, but for the intercession of a French officer who happened to know me pretty well. Audacious thing, wasn't it?"

The rest admitted that it was, and at the same moment the waiter came in with the dinner. The respect entertained for him by Harrington's guests was deepened as the meal proceeded. It had been chosen with care and taste and a nice discrimination, which same remark applied to the wines. The Englishmen felt that their lines had fallen on pleasant places. They sat round the table toying with their liqueurs and cigarettes, quiet and restful now and at peace with all the world. A little colour had crept into Duckworth's pale face, he seemed to have forgotten his fears. Harrington looked at him from time to time with a sympathetic interest.

"You have had a very bad turn, Mr. Duckworth?" he asked.

"Well, yes," Duckworth replied. "I caught rheumatic fever out duck-shooting before Christmas. I had a fearful time of it—in fact, it was touch and go with me. The worse of it is that the malady has affected my heart so dreadfully. I'm a bundle of nerves at present. It seems odd to be like this; because up till lately, when I heard nerves mentioned, I regarded the word as a mere abstract quality. For a man like myself, who has roughed it for years in California, the idea of being a broken-down invalid is terrible."

Harrington's dark face showed distinct traces of interest.

"So you know California?" he said. "I also know the States very well—in fact, I made most of my modest little fortune there. What part?"

"Up along the ridges by Sierra Gradanna principally. Know the region?"

"As well as I know myself," said Harrington. "I nearly lost my life there on one occasion. But we won't talk of hairbreadth escapes to-night, as you look so white and tired. I'm afraid that the shindy in the Casino was too much for you."

Duckworth hesitated as if about to say something.

"It was a shock," he said after a pause; "not exactly the row, but something that happened then. I am to a certain extent a creature of circumstances. It was my fate some years ago to incur the hatred of a lunatic whose name I don't even know; indeed, I should not recognise the man even if he stood before me at the present moment. That fellow followed me to Europe with the full and deliberate intention of taking my life; indeed, he would have succeeded once a while ago, had it not been for my friend Gilroy here. I saw that man in the Casino to-night."

"Indeed," Harrington replied. "This is deeply interesting. But there is one point that I do not quite follow. You say you would not recognise your mysterious antagonist if you met him in the flesh, and yet you say that you saw him to-night."

"Certainly I do. He was on the floor in the melee. I did not see his face; I could not for the life of me tell you what he was wearing. But I recognised him by a peculiarity that would render him conspicuous anywhere. On the back of his hand was a scar in the shape of a crucifix. That is also the mark of the beast on the right hand of the man who has come all these miles to take my life."

A short, queer laugh broke from the lips of Harrington. His dark face changed, then altered again to its normal expression in a dazzling flash. He very quietly apologised for his mirth.

"Pardon me," he said; "I had forgotten how serious—But the strange coincidence! However, we will come to that presently. If Mr. Duckworth—"

"Do you happen to know anything of the man with the crucifix scar?" Gilroy asked at length.

Harrington leant back in his chair and coolly surveyed the company from behind his cigar.

"Yes," he said very slowly and distinctly, "I know the man with the scar very well indeed."

The muscles of Duckworth's thin mouth quivered. He breathed hard, as if he had recently been undergoing some trying physical exertion. The others were deeply interested, but they showed no emotion of any kind—it was to them like the unfolding of the last act of some fascinating play. The stranger was absolutely quiet, too, though a close observer would have noticed the whiteness of his knuckles as his clenched right hand lay on the table. The tendons of the wrist were rigid.

"It is very fortunate that we have met, sir," Duckworth said.

"So it would seem," Harrington replied. "But before I tell my story I should like to hear yours. That comes first in proper sequence, I think. I should like to know whence you derived your information about the star-shaped scar, seeing that you have never been face to face with the owner of it. Are you a good shot?"

The question sounded natural enough, but Duckworth backed from it as if it annoyed him. He was understood to say that he knew something of the use of the gun.

"Oh, that won't do," Herries cried. "My dear chap, why this morbid modesty? You must know, Harrington, that or friend is a marvellous shot, especially with the revolver. Have seen him mark the nine pips on a white card at fifteen paces.'

"What has my shooting to do with it?" Duckworth asked with some irritation.

"I may come in later on," Harrington said quietly. "But first let me know how the secret assassin is identified with the star-shaped crucifix."

"That is where I come in," Gilroy proceeded to explain. "The thing happened in Rome two years ago. It was soon after I had met Duckworth, and we were travelling together at the end of the summer. Duckworth—if he will excuse me saying so—is rather a reticent kind of chap, and not given to confidences. All the same, he hinted to me that he had a something that he was afraid of. I put it down to nerves, and thought no more about the matter for the time. We were staying at the Maremma Hotel, a house which is only on two storeys, as you know, and which has a garden on two sides of it.

"Duckworth had gone to bed fairly early one evening, for we had had a tiring day, and I was preparing to do the same thing in my room, when I heard a scuffle and the noise of blows. Then somebody called for help, and I heard a revolver shot. I don't know why, but the memory of what Duckworth had told me flashed into my mind, and I rushed into his room. It was pitch dark, for the electric lights were out, but I could hear the struggle going on by the bedside. I called out, and a tall figure made for the window. He was outside before I could lay my fingers on the electric light switch, and all that I could see, looking towards the window, was a hand on the ledge. I suppose the fellow was holding on with one hand to steady himself for the drop into the garden below. I could just see that hand for an instant, and no more. On the back of it was a scar in the shape of a crucifix."

Harrington nodded thoughtfully. He appeared to be deeply engrossed in the story, though he did not look once in the direction of Duckworth. He helped himself to a fresh cigarette and poured a little more claret into his glass.

"All this is exceedingly interesting," he said. "The dramatic part appeals to me. Mr. Duckworth has a deadly enemy whom he cannot identify save for the peculiar scar. The man with the scar is the sword of Damocles hanging over his head. The knowledge of that near presence gets astride his nerves. Is not that so?"

"I'll not deny it," Duckworth said gloomily; "especially in my present state of health."

"Let us get on a bit further," Harrington proceeded. "Did you bring the matter before the authorities?"

"No, I didn't; I had no desire for any unnecessary fuss. I don't mind saying that I took a great many precautions to throw my would-be assassin off the track—"

"With the result that there has been no further attempt on your life? You have seen and heard no more of the man with the scar from that day to this?"

"Not till I saw that queer, maimed hand in the Casino to-night. You may argue that this is no more than a strange coincidence, but I know better. That fellow has got on my track again; he has followed me here. There could not be two men with scars like that. But seeing that you know the fellow perfectly well—"

"Stop a minute," Harrington interrupted. "Don't let's go too fast. In the first place, tell me what is the real or fancied grievance that the man with the scar has against you. Didn't you say it had something to do with gold-mining."

Duckworth nodded curtly. Evidently he had no disposition to be communicative. He shuffled about in his chair; he seemed to be uneasy under the gaze of Harrington, which was turned full upon him now for the first time.

"Come," the latter urged. "It is only fair to yourself that you should make your case good. When you have spoken, then I will present the case from the point of view of the man with the scar. And if your story rings true, I will promise you one thing—you will never have cause to fear the man with the scar again."

"You will tell us all about him?" Gilroy asked eagerly.

"Certainly I will," Harrington proceeded, "when Mr. Duckworth has spoken."

"But I assure you there is little or nothing to tell," Duckworth exclaimed. "It was merely a case of diamond cut diamond up in the Sierras yonder. We were not mining in the strict sense of the word; we were placer-hunting—that is, looking for pockets of gold washed down by the water from the snows, or placed there ages ago in the Glacial period. As you know, they were a pretty rough lot in those old days."

"I know that by painful, personal experience," Harrington said gravely.

"Well, I had to take care of myself. I had located a likely spot on the spur of one of the mountains, and I had pegged out my claim. I couldn't work it for a couple of days, for the simple reason that I was down with a touch of fever. When I went back in due course, I found that somebody had taken my place. I found the fellow and ventured to expostulate with him. He threatened me with what would happen when his partner returned. You know how one word leads to another in that quarter, and it soon came to the drawing of weapons. I was quicker on the trigger, and my man went down with a bullet through the lungs. We were fighting on the edge of a narrow plateau, with the valley two thousand feet below us, and he went headlong back over the edge and was seen no more. Nobody could ever have found that body. It would lie there for ever under the snows. But I tell you it was a fair fight."

Duckworth uttered the last words with a snarling challenge in them. His face was deadly pale, and little beads of moisture stood out on his forehead. Nobody spoke, the interest was too great for mere trivial interruption. It was only Harrington who asked a question at length.

"Did the partner intervene?" he suggested.

"Not in a manly, straightforward kind of way, curse him!" Duckworth said. "I tell you the claim was mine, and not a soul in the world could fairly dispute it. I was myself in those days, and feared neither man nor devil. I worked that placer pocket single-handed for a week, and I took out of it over two hundred thousand pounds' worth of gold-dust. So far as I was concerned, I had finished mining. When I had done, the partner came back just too late to meet me, for I had started for San Francisco. This partner was the man with the scar on his hand, though I had never seen him and never heard his name. But another successful man who got to 'Frisco a day or two afterwards brought tidings of the fact that a mysterious ruffian had sworn a bitter oath against me, and that he was going to follow me to the end of the earth. As the fellow did not know me by sight, and had never heard even my people's name, I did not give myself any great thought over the matter until that night in Rome. And if there was anybody who can say that I have not told my story honourably, I should like to meet him face to face. I think that is about all."

"It is certainly your turn now, Harrington," Herries suggested.

"Yes, I fancy it is my turn," Harrington said slowly and distinctly, "especially as I told you that I know the man with the scar on his hand quite well."

"He must be an abandoned scoundrel, a poisonous ruffian!" Gilroy said hotly.

"Well, it sounds odd, but I cannot quite agree with you," Harrington proceeded in the same smooth and even manner. "Let me present the story from the point of view of the other man. When you have weighed the two narratives up, you shall judge between them. And when you have done so, I will undertake to produce the man with the scar on the right hand."

The little audience thrilled; even the two healthy, clean-lived Englishmen were conscious of the fact that their pulses were beating a little faster than usual.

"We will call the man with the scar Clarkson if you like," Harrington proceeded. "He had left the good old country, meaning England, ten years ago, to seek his fortune. No need to speak of his ups and downs, of which he had many. He was a man of few friends; he had left nothing behind him in England but one little girl, of whom he was exceedingly fond. This little girl was delicate and needed more than the man could send her. He worked very hard for her, he led a clean life for her sake. And after many adventures he reached California, and there, together with a partner called Challis, he struck a rich placer of gold. It was an opportune find, for the little girl was ordered to the South of France, and but for the gold she must perforce have remained in England and died. She did die, as a matter of fact, because at the last moment the gold was not forthcoming, and I will tell you why.

"The placer was difficult to work, because it lay on the sheer side of the mountain—it had only been located at all by means of rope. But then it was enough to make the fortunes of more people than one. They decided to rig up a kind of crow's-nest, and procured the necessary timber and ropes. They got the thing going at last, they worked the whole of one day, perhaps the happiest day those two passed in their lives. They were just going to knock off work for the day when they heard a shot at the head of the spur. It was quickly followed by another, there was a sudden jar on the rope, and then they were going headlong into the valley, and both of them fell two thousand feet below. The rope had broken.

"After the first second or two, memory deserted the sole survivor. He recollected nothing more till he woke two or three days later in a shepherd's hut, more dead than alive. He had been lucky enough to be thrown off a cushion of snow into a great bed of dry litter in an old stream, and by a most amazing miracle he escaped altogether. Of his partner the man heard nothing more, he was for ever buried in the snows of the hillside.

"There is no reason to dwell at length on that. As soon as Clarkson could get about again, he tried the hillside once more with some new tackle; at any rate, the gold was still there, and there was no reason why he should not procure it. But the gold was no longer there—somebody had come along and removed the lot of it. It was a startling discovery, for the secret had been well kept, and it struck Clarkson all of a heap at the time. He began to make inquiries quietly; but nothing came of it until the second day, Clarkson got a pointer or two from a man called Mad Billy. Mad Billy had met with an accident in a mine, which had turned his brain. He did odd jobs about the place, and as to the rest, he spent his time gloating over imaginary finds. And Billy had a story to tell."

Harrington paused and lighted a fresh cigarette. He glanced round the table to see that the audience were following the story. There was no need to do anything of the kind. The two Englishmen were looking at the speaker with parted lips, Duckworth's face was pinched and blue.

"Gentlemen, the thing was no accident at all. According to Clarkson, another man had got on the track of the secret. He had watched the rigging up of the crow's-nest, and in his secretive, furtive way Billy had watched him. He had seen the other man spying, and his movements had excited the suspicions of poor Mad Billy. The plan of the stranger was simple in the extreme. He dared not show himself against the edge of the cliff with the snow for a background, because there were other men mining there, and there—he had a better notion than that altogether. He was a fine shot, as fine a shot as our friend Mr. Duckworth here."

Duckworth started slightly and coughed. He seemed to have trouble with his breathing.

"The sound of a revolver would arouse no suspicions there. So the revolver was fired twice from the cover of some shrubs—Mad Billy looking on all the time—fired full at the rope that held the cage where Clarkson and his partner were working. The shots were true and straight so that they cut the rope as clean as a knife. It was a pretty scheme, because, as the rope was shot in two, there would be no suspicions of foul play; the thing looked just as if there had been a flaw in the new rope; and, indeed, I could not tell the difference when the rope was shown to me."

There was a long pause before anybody spoke. All of them seemed to feel that Harrington was coming to the crux of his story.

"You see, this was no madman's chimera," he went on again. "Billy's tale was well backed up. But the gold was gone, and the man had gone also, and the child died, and Clarkson swore a great oath of revenge. A little time after that, Clarkson had the luck that he no longer wanted, so he left California, taking Billy with him. Billy was the only one who could identify the ruffian who had done that thing. For a year or more they hunted Europe in an aimless kind of way. It is rather strange that I should stumble by accident upon the man that Clarkson was seeking."

"But I don't see," Herries cried, "that you have done anything of the kind. So far as I can see—"

"Pardon me," Harrington said, "but your friend Mr. Gilroy gave me the clue by telling me all about that business in Rome. The man with the scar on his hand was Clarkson. Clarkson shall tell the rest of the story in person. Let me produce him."

Harrington's voice had suddenly grown hard and cold. He stretched out his right hand and laid it with force on the limp right hand of Duckworth, who started at the touch.

"Take my serviette," said Harrington in the same cutting voice, "and dip it in the finger-glass. Now rub it across the back of my hand hard—hard!"

In a dazed kind of way Herries did as he was desired. Then a quick, gasping cry arose from all round the table, as a brown stain of paint peeled off Harrington's hand, and the red edges of a scar like a crucifix rose in the place. Duckworth's mouth was trembling: he looked into the face of the man holding him with fearful eyes.

"Behold the man!" Harrington said. "I am Clarkson. It was in Rome that I ran my quarry down, at the Maremma Hotel. Billy spotted him as he entered his bedroom one night. All he would say was that the object of my search was in his bedroom. I asked no questions, I aroused no suspicions, I took Billy's word for it. I had made up my mind that the man should die. His life belonged to me, I was going to take it. Mr. Gilroy knows how I was prevented; the rascal whose hand I hold knows how he baffled me subsequently. And when Billy died six months ago, I decided to abandon my search altogether—it seemed as if Fate had deserted me. But the accident of circumstances is on my side at last; by sheer good luck I have found my man. Had Mr. Gilroy said nothing about that affair at Rome, I should have parted from you all on good terms. Heavens! I might even have become a friend of this fellow!"

Duckworth attempted to say something, but the words clung to his twitching lips.

"What he tells you is a lie," Harrington said. "What I say is no more than the truth. Let him stand up and deny it if he can. Let him try to refute me. One thing is certain, he does not escape me again. Stand up!"

The command was harsh and stern. Mechanically Duckworth obeyed. He rose slowly to his feet, holding on to the table for support. There was no reason to deny the accusation, no reason why the others should not urge him to that course. His guilt was stamped on his face. He pressed his hand to his heart and suddenly sat down heavily again. He had fallen forward with a crash against the glasses there, then lay quite still.

"You are wrong, sir," Gilroy said in a hoarse whisper. "He has escaped you. He is dead."

Duckworth lay there, dead, truly enough. And outside, the stars shone, there was light laughter on the air, and the soft sound of music in the distance.