WHAT his real name was, it doesn't matter. There were one or two cynical inhabitants of Nagaska who averred that he did not know himself; but that was a libel, though uttered in no carping or ungenerous spirit, for the man who was known as Jim Baxter was a long way the most popular person in that little community on the fringe of the North-West Frontier, where they farmed in a casual sort of way in accordance with the almanack, and a few of the more adventurous spirits did a little mild silver mining.

It was a sort of Sleepy Hollow, that little neck of valley between two ranges of mountains, and there life moved slowly, for they were a contented race, earning just what they wanted and no more, content to let the world go by as long as the snows were not too severe and a plentiful supply of firewood was to be had for the asking. Papers came to the little settlement occasionally, but if they failed to materialise from the station eight miles away, nobody troubled and nobody cared. Now and again they heard stories of crime and outrage, and on one occasion a notorious malefactor had invaded the settlement in search of food, and with the North-West Police hot upon his track. He had not looked in the least like the popular villain depicted by a highly-coloured press—in fact, he was insignificantly small, very ragged and dirty, and he had made no effort to hold up a peaceful community at the business end of a revolver. On the contrary, he had crawled almost on his hands and knees, and had begged for food like some harmless tramp, so that even the children had gathered round him quite fearlessly and without a shadow of hesitation. Still, he was a desperado, as his record showed, and, when the time came, put up an exceedingly pretty fight, during which two of the North-West Police had been severely wounded. But in the eyes of the people of Nagaska he had appeared more like a cat driven to bay by half a dozen dogs. And that, so far as the oldest inhabitant could remember, was the only bit of excitement Sleepy Hollow had ever seen.

But all this, of course, has nothing to do with Jim Baxter. He had drifted there eight or nine years ago, a tall, powerful man dressed in grey tweeds of a pattern unknown to Nagaska, though when Phillips, local superintendent of the North-West Police, first set eyes on him, he muttered something to himself that sounded like "Bond Street." For Phillips was an Englishman of family and a man of some means, and he belonged to the North-West Force only out of sheer love of the hardy life and an unholy thirst for adventure. He tried, in his genial, courteous way, to find out something about Jim Baxter, but that individual was not to be drawn. He admitted freely enough that he was an Englishman, and that there were powerful family reasons why it had become necessary for him to turn his back abruptly upon the land of his birth, to all of which Phillips listened sympathetically enough, though when he asked Jim whether he had ever worn His Majesty's uniform, the latter coloured up and reminded Phillips quite politely that there were limits to ordinary curiosity.

"All right, my friend," Phillips had said. "I don't want to barge in. But, you see, I am responsible for law and order in this part of the world, and I like to know as much as possible about newcomers."

"That's all right," Jim had replied. "I'm not a criminal and I'm not exactly a pauper—that is, I have enough to keep myself in clothes and food and an occasional glass of whisky."

With that the conversation came to an end, and Phillips went his way, with the intention of keeping his eye upon the stranger. But there was really no occasion, for the months went by and the years rolled on without any outbreak on the part of Jim Baxter, who settled down in the little community as if he would like to stay there all the days of his life. He did nothing except lend a hand occasionally up there in one of the small silver mines, but this was more to kill time than anything else.

He built himself a shack, where he spent most of his day reading—indeed, Jim's big box of books had given him quite the reputation of a scholar in those parts. But they were novels, for the most part, English classics ranging from Richardson down to Kipling, with a sprinkling of French literature. And with these for his sole companions Jim Baxter lived quite contentedly for upwards of nine years.

Not that he was, even in the slightest sense, a recluse. To begin with, he was exceedingly popular with the small handful of children there, who ran in and out of his shack at all times of the day without the slightest fear or hesitation. They would drop in to dinner or tea or supper, when Jim would tell them stories and see them safely home afterwards.

He was a familiar figure in the saloon, where it was said that he could hold more Canadian whisky than any two men in the settlement, which was no libel, though no man in that congenial company had ever seen Jim the worse for liquor during the nine years he had been there. He was a past master in the art of chaff and repartee, a big, easy-going, genial giant of a man who spent his money freely and apparently had no enemy in the world.

Whence he derived his means, no one knew, and no one particularly cared. Once a month he repaired regularly to Fort Falcon, the trading station some six miles away, where the police had their headquarters, and whence came supplies of all sorts upon which Nagaska depended. There he would transact certain business at the bank, and come back with his pockets full of dollar notes, which apparently lasted him for a month to the very hour. If there was anything of the man of action about him, he disguised it carefully, for apparently a more indolent man never breathed. And so things had drifted on for the best part of a decade, and it looked as if Jim had settled down to live and die there, when the thing happened that stirred Nagaska to its depths and brought it face to face with a peril which nobody had ever anticipated, but which was dire enough in all conscience. It was one of those bolts from the blue that swooped down out of a clear sky in the twinkling of an eye.

It was rather late autumn, a red and flaming autumn touched with gold, with just a touch of frost in the air to warn the people in the settlement of what was coming, so that outdoor workers pushed on in the usual leisurely way, the wood for the winter was gathered in, and the few odd animals belonging to the inhabitants had come back to the stables. A little later on the snows would come down in earnest, and for the next few months the little community of Nagaska would be cut off from the rest of the world, to sleep and hibernate, and eat and drink like so many squirrels till the spring thaw came and they could get into touch with civilisation once more. But this was entirely in accordance with the ordinary course of things, and so long as the little garrison was provisioned for the winter, nothing mattered.

There would be plenty doing in the course of a week or two, when every man, woman and child would be pressed into the service of the State, and every horse and vehicle busy on the road between Nagaska and the Fort. It was characteristic of the inhabitants that this was always left to the last moment, which mattered very little, because they knew almost to a day when the first fall of snow would take place. At least, that was the easy philosophy of the place, and they all acted up to it religiously. It never seemed to occur to anybody that one of these years Our Lady of the Snows might take it into her head to come down in her white and shining beauty a week or two before the annual advent of her court, in which case it might go mighty hard with Nagaska. It never had occurred to anybody, and by the same process of reasoning it never would, which is a form of philosophy not entirely confined to rude communities.

And, curiously enough, it was Jim, of all men, who raised the very point one evening soon after the frost came, as he lounged on an empty apple barrel in the saloon, with a glass of whisky in his hand, What would happen, he wanted to know, if the big snow came down suddenly?

"It never has," the oldest inhabitant said, "and, consequently, never will."

"Ah, but suppose it does?" Jim persisted. "It isn't impossible, Methuselah."

"Nothing's impossible in this world," the old man said solemnly, "but that's very near it."

"Very likely," Jim agreed. "But it might come—the big snow, I mean, when you couldn't get to the Fort perhaps for a fortnight."

"There's enough here to go on with," another optimist said, "enough for a fortnight."

"And after that you'd starve," Jim went on.

"Guess we should," another philosopher put in.

"But suppose there was nothing here," Jim returned to the point. "It's only a wooden shack, after all, and there are at least fifty barrels of petroleum out there. Supposing the saloon caught fire? It wouldn't last a quarter of an hour. And what should we all do then?"

The conversation was growing uncomfortable; it was felt by the slow-witted opportunists about the stove that Jim was trespassing on the debatable lands of good taste. So they bade him fill his glass again and talk about something else, which, in his amiable, obliging manner, he did. Then they went their way presently, each to his shack to sleep and dream and give no heed to the morrow. A big wind had got up during the evening, a raging gale from the north-east, with the smell of the snow in it, so that they were all eager enough to get under cover and feel the warmth in their bones again.

But not for long. For presently out there in the clearing appeared a spark or two of light, then a tongue of flame and a quick roar of a conflagration. Presently there was a report that shook the whole settlement, so that the men came hurrying out, hastily wrapping themselves in their skins, to see what convulsion of Nature had taken place.

And there was the saloon one blaze of fire. The flames ate up the dry wood greedily, they raced from beam to beam and room to room until presently they reached the barrels of petroleum in the sheds behind. Then followed a great sheet of dazzling fire, the roar of an explosion, and the place where the store had stood was just no more than a big handful of glowing ashes. The whole thing was over in a few minutes. Fortunately no lives had been lost, but beyond the small amount of food in every shack, not another mouthful remained in the settlement. Men talked over the calamity in low voices as they stood there, with heads down in the piercing gale, and muttered of what they would have to do on the morrow to make this thing good. It would be a case of all hands to the pump, so to speak, with every man and every animal on their way to the Fort in search of food. And with this decision uppermost, and with the houseless saloon keeper and his wife accommodated for the night, one and all turned their backs on the soul-searching gale and burrowed into their shacks like so many rabbits.

It was bitterly, bitterly cold, far colder than it ought to have been at that time of the year, and the voice of the snow was singing in the air. There would undoubtedly be a fall before morning, not heavy, perhaps, but it was coming, and Jim Baxter, as he turned into his buffalo skins, asked himself an uneasy question or two. It seemed strange that this calamity should befall within an hour or so of the discussion in the saloon. And if it did come in real earnest, then assuredly the little community at Nagaska was face to face with starvation. Then Jim put the matter out of his mind and went to sleep.

He woke up the following morning to the realisation of a white world. For a time, at least, it seemed to him, in a dim, uncomprehending sort of way, that the dawn was long in coming, before the real truth came home to him. Then he saw that the windows were piled high with snow, he could hear the hiss against them, and when finally he dragged himself out of his skins, he saw stark tragedy lying there before him.

For it was no herald of the coming winter that had come down on the gale in the still watches of the night, but the real thing itself—several feet of snow, with every sign of more to follow, and the north-west wind tearing round the house like a pack of angry wolves in search of their prey. It was intensely, bitterly cold, too—a freezing, biting cold that sent Jim headlong to the stove, where he piled up the logs and set about getting his breakfast.

This he did in his usual calm, methodical way, eating his bacon slowly and deliberately, filling his pipe afterwards. He knew perfectly well what Nagaska was face to face with, and not for a moment did he try to belittle the danger. He knew that the lapse of a day or two would see the end of the last ounce of food in Nagaska. He knew that the people over there at the Fort would not trouble anything about the settlement, for had not the authorities there every reason to believe that the big store in the village was amply supplied for all immediate needs, at any rate? And for the moment Fort Falcon would be busy looking after itself.

It was only a matter of six miles, but six miles of desolation and possible death for anyone who had the temerity to face the danger.

All this Jim knew perfectly well, and he knew perfectly well what he was going to do. The thought did not trouble him in the least as he sat there before the stove, smoking his pipe until at length it was finished, after which, with considerable difficulty, he made his way down to the little building which was parish room or school house—in fact, anything according to the point of view of the inhabitants. And there, as he expected, he found a little handful of men gathered round the stove, discussing the situation deliberately, with reminiscences of similar happenings.

There was no hurry, of course—nobody ever hurried in Nagaska. They would probably sit and talk and talk for hours. Jim stood there in the doorway, contemplating the ancient fathers with a humorous gleam in those sleepy eyes of his.

"Pretty bad, isn't it?" he asked.

"Well, I guess it is," the old man known as Methuselah drawled. "I've been here, man and boy, for nearly eighty years, and I disremember the big fall ever coming as early as this. And it is the big fall all right."

"So it seems," Jim said drily. "But say, boys, did you ever have the big fall before you got the winter provisions in before,?"

Old man Methuselah shook his head.

"Never," he went on. "We always goes by the almanack, and it's never throwed us down before."

"And you have never had a fire here before?"

"Well, that's an act of Providence," the old man said solemnly. "That's what it is —Providence."

"Very likely," Jim agreed. "But I've always been told that Providence helps those who help themselves. Now, look here, boys, it's up to us to do something. They won't worry about us over at the Fort, because they'll conclude that we have got enough to go on with for a week or two. Of course they don't know the store is burnt down, else they'd make an effort to get through to us with a few loads of provisions. Seems to me we've got to get to them."

"Ah, but how?" the old man asked. "It can't be done, Jim. There's no livin' man could face it. And, mind you, there's more to come, lots more."

"And meanwhile?" Jim Baxter asked.

The little group round the stove shifted uneasily. It was felt in a vague sort; of way that Jim was hustling, and anything of that sort was quite foreign to the ways and customs of the settlers in Nagaska, And yet there was not a single man there who did not realise the danger.

"How long can you last out?" Jim went on.

There were various opinions, more or less deliberately enunciated, but, generally speaking, it came out reluctantly enough that two days would see Nagaska on the verge of starvation. Jim beamed genially on the crowd.

"That's just what I want to get at," he said. "Now, we ain't going to starve—at least, the women and the kids ain't, if I've got anything to do with it. Somebody's got to go; the question is, who?"

They looked at one another apprehensively, for there was not a man there who did not thoroughly understand the lurking perils that lay in every yard of that six miles of snow. They began to discuss it with one another in whispers; they told tales of lonely settlers cut off in snows less deep than this, who had lain down and died within rifle-shot of their own shacks. And then someone a little more enterprising than the rest suggested that they should draw lots for it.

"Yes, that's right," Methuselah said. "And you can put my name in the hat, too."

"There's a fine old sportsman for you," Jim cried. "But there are not going to be any lots, not if I know myself. Listen to me, boys. Somebody's got to go, and there isn't one of you who is not married. You haven't all got children, but you've got wives. Now, I haven't either, not even relations in the proper sense of the word, and if anything happens to me I shan't be missed, except perhaps by the kiddies here. I'm a pretty useless sort of individual, but none of you have ever told me that. That's why I am going. And, what's more, I am going now. If I don't get there, you'll be no worse off, and if I do get there —well, I shall be no end bucked. So I'm going, whether you want me to or not."

They tried to dissuade him, they protested that every man should take his chance alike, but in his genial way Jim talked the others down; and so presently, with all the village to see him off, he set out on his errand across that white world, with the powder stinging in his face, and the wind smiting in mighty blows as he turned his eyes, in the direction of the distant pine ridge beyond which Fort Falcon nestled like some hawk on its eyrie. The pine ridge was guide enough, so that for the next three hours he fought unsteadily through the snow, that here and there was waist-deep, until the shades of night began to fall, and he had made four miles of his journey. By this time he was amongst the pines, that tossed and moaned overhead like things in pain. He had been most of the day coming so far, and now that splendid animal strength of his was beginning to fail. He was realising that he was not quite the man he had taken himself for, and he somewhat whimsically wished that his reputation as a champion whisky drinker had been a little the less merited. By this time his lungs were roaring like a pair of bellows, his eyes were nearly blinded by the white glare, and he was going over at the knees.

But still he struggled grimly and doggedly on, until at length he came, in the pitch darkness, to the crest of the ridge and between the flurries of snow looked down at the valley on the other side, where he could see the lights of Fort Falcon shining through the gloom. All this was encouraging enough, but, on the other hand, there were another two miles to go, and once Jim had put the shelter of the ridge behind him he encountered the full force of the gale.

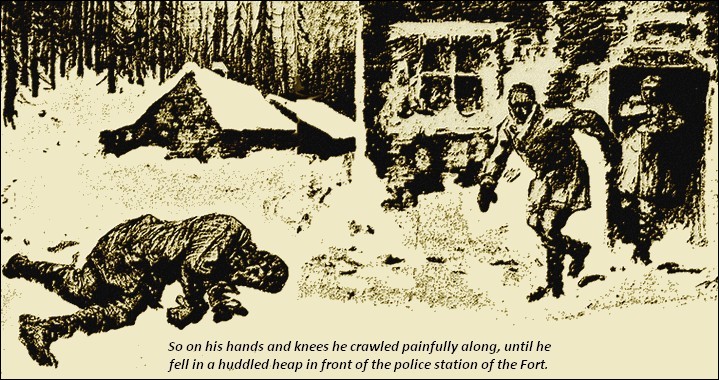

It turned him round more than once as if he had been no more than a piece of paper. The piercing cold stabbed him to the bone. More than once he dropped to his knees, absolutely exhausted and worn out; then he struggled to his feet again, clenching his teeth and fairly sobbing with rage and disappointment to find himself thus baulked and broken with the haven absolutely in sight.

It was pitch dark by this time, so dark that he could only feel his way. He stumbled on mechanically down the slope until he was within half a mile of the Fort, where he collapsed altogether. He dragged himself slowly and painfully to the lee side of a hummock, where he was fain to lie down and rest. When he opened his eyes again, the sun was shining overhead, and the fury of the gale had abated. His hair and moustache were frozen to his face, and he had a curious sort of feeling that his ears were gone. He knew now that everything depended upon the final effort; he knew that he might win through, and he knew, too, that the end was near at hand as far as he was concerned. So on his hands and knees he crawled painfully along, until he fell in a huddled heap in front of the police station of the Fort. There he was picked up presently and carried into a room, where they laid him before the stove and tended him as carefully as if he had been a little child. They fed him and poured brandy down his throat, so that presently he came back to his senses again, and smiled to find that his efforts had not been in vain. Phillips was bending over him to catch the first words that came from his lips.

"Don't hurry," he said. "Take your time. Now, in the name of fortune, what's this madness, Jim?"

Slowly and painfully Jim explained. When he had finished, the troop looked from one to another in astonishment.

"I wouldn't have believed it possible," Phillips said. "I don't think there is another man on the American Continent who could have done it."

"That's good hearing," Jim panted. "At last I begin to realise what I was born for. Now, look here, Phillips, I'm done for. No, you needn't shake your head. I can see it in your face, and even if I couldn't I should know. You'll see to those people, won't you?"

"Of course I will," Phillips said. "We'll get all the teams out and rush supplies over to Nagaska within an hour. If the snow holds off, there's nothing to be afraid of. The doctor will be here presently."

Jim smiled faintly.

"Let him come if he likes," he said, "but I'm past all surgery. What's the good of pretending? You know it as well as I do."

"Well, you're pretty bad," Phillips admitted.

"I guess I am. I can hardly see you now."

"Poor old chap!" Phillips said. "Is there anything I can do for you? Any message? Anybody I can write to? You know what I mean."

Jim shook his head.

"No," he said. "There's nobody wants to hear from me; just say nothing and do nothing. Take my pocket-book, when I am dead, and destroy it, and that's about all."

It was, for those were the last words Jim Baxter ever spoke. And there was nothing in the pocket-book of any account, or so Phillips said. And there the record ends, except in the hearts of Nagaska, whence it will never fade.