IT seemed to Jack Clifford as if a lid had been shut down somewhere and the noise and roar of London stifled out of existence. Everything was so quiet there, so different to what he had imagined the interior of a newspaper office to be. There was no bustle, no struggling or noise, merely a suite of silent, green rooms where men worked feverishly under the light of shaded lamps. Wickham, the editor of the Daily Herald, welcomed Clifford into his own sanctum and indicated a chair.

"I hope you don't mind," he said. "As a matter of fact, I have sent for you professionally. To put the case in a nutshell, we have been receiving from time to time exceedingly valuable pieces of news from a mysterious old man who calls himself Levetsky. I don't mind telling you that I regard this as a nom de plume. The man has been to see me more than once, and he always comes with something very startling in the way of news, especially news relating to the Eastern Europe problem."

"Your paper appears to be very well served in that respect," Chfford said. "On more than one occasion you have fairly startled London. That letter from the Kaiser, for instance."

"My dear fellow, that was no thanks to our enterprise. A verbatim copy of the letter was supplied by this Levetsky. He would accept no payment, he refused to give any account of himself, and left us to publish it as we liked. You see, we have always taken the side of the Progressive Party in Russia, and I understood Levetsky to say that be was merely showing his gratitude. I hesitated for a long time before publishing that letter, but, as all the world knows now, I was perfectly justified in doing so. On no less than six occasions we have brought off the most remarkable coups, and all owing to that extraordinary old man who comes and goes in the most mysterious fashion and who is never wrong. Which brings me to the point. About nine o'clock to-night, Levetsky called to see me, but I was busily engaged then and could not give him an interview. I sent a message down to ask him to come back about half-past ten, to which he replied that he might not be able to do so; at the same time he sent me a few lines in an envelope—I presume, as a guarantee of his bona fides. I tell you I fairly jumped when I read the contents of that note."

As he spoke, Wickham bent forward and whispered into Clifford's ear. His voice was low and impressive.

"I don't want a soul to know this," he said. "According to this morning's papers, the Czar was more or less a prisoner in the Kremlin Palace, practically owing his life to the courage of a regiment of Cossacks. That is what all Europe believes, but Levetsky tells me that the Czar is at present in England and is hiding at Buckingham Palace at this very moment. I tell you, Clifford, this is the kind of "scoop" that makes an editor's blood tingle. Common sense inspires me to trust Levetsky implicitly and make a blazing feature of his information in to-morrow morning's Herald. The man has never played me false yet, and I don't see why he should now, but I have got a fit of editorial stage fright upon me and I dare not risk it."

"I'm not surprised," Clifford said. "I can see your dilemma exactly. Here is a chance of a lifetime, and yet if the information proves to be false, you do your paper incalculable damage. But tell me, where do I come in?"

"Well," Wickham said, "you are the one man in London I can trust in a crisis like this. An old Secret Service man like you is better than half-a-dozen detectives. I quite expect that Levetsky will come back here about half-past ten, and I shall see him and get full particulars. I want you to wait outside in the corridor and follow Levetsky. Find out all about him, and according to your report, so I shall act in the matter of this exclusive information. It does not matter if you fail to make your report to me before half-past one this morning, as we don't go to press till after two,"

Clifford looked up eagerly with the light of battle gleaming in his eyes. Here was an adventure after his own heart—something dark and mysterious, and with a strong suggestion of danger about it. He nodded briskly.

"You can count me in," he said. "I only wish I was dressed better for the part. One does not generally go off on this sort of excursion in an opera-hat and a dress-suit. Still, I dare say I can manage to borrow an old overcoat from one of the staff."

The matter was arranged to Clifford's satisfaction. He waw still talking to Wickham when an assistant came up and whispered something to his editor. The latter turned immediately to Mr. Clifford.

"Here's our man," he said. "If you wait outside, you will get a glimpse of him as he comes up the stairs."

It was too dark in the corridor for Clifford to get more than a hazy impression of the visitor. He was of medium height, and would have looked taller but for a painful stoop in the shoulders. He dragged his left leg after him as if it had been maimed in some accident; altogether he suggested an old man who had suffered much by contact with the world. The slightly aquiline features were almost smothered with a mass of black moustache and beard, the eyes were hidden beneath the shadow of a large-brimmed hat; altogether the purveyor of exclusive information bore a strong resemblance to the typical Nihilist of the stage.

* * * * *

It was half an hour later before Chfford had an opportunity of shadowing his quarry. The old man passed down Tudor Street on to the Embankment and turned presently into one of the walks beyond Temple Gardens. The electric lights cast clean shadows of the trees on the gravel, beyond the shrubs where was an inky mass of darkness. The old man limped along for some time, with Clifford strolling some twenty yards in the rear, then he turned round suddenly and waited till the amateur detective was alongside. It was quite clear to Clifford's mind that Levetsky meant to speak to him.

"You will pardon me," he said, "but I am going to ask you to do me a favour. It is only a small matter."

Somewhat to Clifford's surprise, the speaker's English was not only correct and bespoke a man of education, but there was a ring in it which proclaimed the fact that Levetsky was accustomed to giving orders and in the habit of being obeyed.

"Certainly," Clifford said pohtely. The adventure was shaping after his own heart. "I shall be only too delighted. My knowledge of London, like that of a certain historic personage in fiction, is extensive and peculiar. My purse, alas! is not so extensive, though it may be equally peculiar. Still—"

"Mr. Clifford will have his joke," the Russian said, with a quiet smile. "I think you will admit, sir, that one good turn deserves another. I am not in the least annoyed that Mr. Wickham had me followed to-night; he has the interests of his paper to safeguard, and he was prudent to act as he did. My good fortune lies in the knowledge that Mr. Wickham selected Mr. Jack Clifford to play the part of his detective."

"This is gratifying," Clifford said. "This, if I may so put it, is fame. But I fail to see why I should go out of my way—"

"Precisely," Levetsky smiled. "A little time ago, you were interested on behalf of a certain Cabinet Minister who had become entangled with a lady whom we will simply speak of as the Countess. He wanted to prove what you suspected—that the Countess was no more than a police spy and an adventuress. In this case, luck stood you in good stead, for an anonymous letter which you received enabled you to persuade the Countess that the air of London was dangerous to a constitution like hers. Not to make too long a story of it, Mr. Clifford, I sent you that letter."

"Did you really?" Chfford exclaimed. "Now, that was devilish—I mean, exceedingly thoughtful of you. You may command my services in any way you wish."

Levetsky's manner changed; he became suddenly curt and stern. With a swift, flashing glance around him, he drew Clifford behind a clump of bushes and commanded him to take off his overcoat. Once this was done, Levetsky took a pair of scissors from his pocket, and, coolly untying Clifford's cravat and unfastening his collar, he proceeded to cut away the whole of the shirt-front and neckband, to which extraordinary proceeding Clifford acquiesced without a murmur. It was one of the strange, bizarre kind of things that he was accustomed to himself.

"This is all very well," he said, "but what am I going to do?"

"You are going to be me," Levetsky said. "See, I discard my coat and the scarf which is about my neck, then I place this apology for a dress-shirt about my breast, and tie the collar, so. Also, I take your opera-hat like this, then I slip on the overcoat, so, and button the two bottom buttons. In the darkness of the night I pass for a gentleman going home after dinner. Then I dress you up like this: I place over your face my ragged moustache and beard, then my wig and the slouch hat. When the man who is watching for me by Cleopatra's Needle sees me emerge from the Gardens, he says to himself: 'That is not my man'; then, when he sees you coming out of the Gardens, he says: 'Ah I here is the old fox! Let me follow him.' But I do not want to be followed, because I am going to your Buckingham Palace; on the other hand, I want you to be followed. You will walk straight from here down the Embankment and over Westminster Bridge. Your adventure will not be entirely free from danger, so that if you are afraid—"

"I am not in the least afraid," Clifford said. "On the contrary, I am looking forward to the adventure with great eagerness. If I am kidnapped—"

"Which is more than probable," Levetsky said coolly. "In that event, you must ask your captors to send for Colonel Azoff. Unless I am greatly mistaken, the gallant colonel is an old official acquaintance of yours, and it would be a great misfortune to him if anything happened to you at this moment."

"That is right," Clifford said drily. "A little matter of forgery which would be exceedingly awkward for a member of the Russian Ambassador's staff if the thing became public."

Levetsky smiled with the air of a man who knows all the circumstances of the case. He stood in the darkness; then, as he bent forward and a ray of light flickered for a moment on his face, Clifford could see that his aspect had entirely changed. He was no longer bent and old; he stood there alert and vigorous, his powerful face as if cut in marble. There was a long scar on the left cheek. All this Clifford noted in the winking of an eye. It was not for him to ask questions. He was ready to obey.

"What am I to do now?" he desired.

"Merely to carry out instructions," Levetsky said. "Now that you are figuring in my disguise, I see a resemblance to me which is remarkable. Unfortunately, my enemies have penetrated my disguise, and this is why you are appearing, so to speak, as a wolf in sheep's clothing. I dare say so clever a mimic as yourself could copy my slouch and my limp. All you have to do now is to walk along the Embankment and stroll across Westminster Bridge. As your bishop said in the story, we can leave the rest to Providence."

SOMEWHERE or another a clock with a remarkably sweet chime was striking the hour of eleven. Clifford sat up and began slowly to collect his thoughts and review the events of the past hour or so. He could distinctly remember limping across Westminster Bridge; he recollected that he had paused there to look down into the water; the bridge had been singularly quiet for that time of night. There were practically no passengers on foot, so that Clifford seemed to have London to himself. He was enjoying the adventure keenly enough; he half expected at any moment to be pounced upon by something weird in the way of a malefactor, so that he took no notice of two men who came along arm in arm, as if they had just left the Houses of Parliament. In a casual sort of way Clifford could see that they were in evening dress; just before reaching him, one of them paused to light a cigarette. The match went out, and Clifford understood the smoker to say that it was his last.

"You got a match?" he said, addressing Clifford as a man of that class would speak to the derelict.

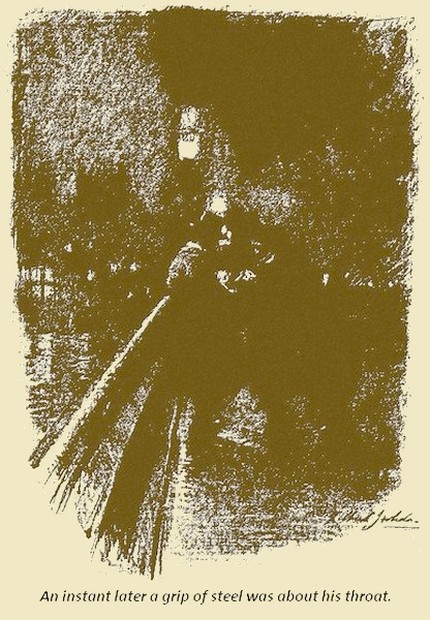

Chfford fumbled in his pocket; he did not notice that the second man had dropped behind him, and an instant later a grip of steel was about his throat. Something sweet and pungent was crammed into his mouth and nostrils; the whole world fainted away into a kind of easy dream. Clifford's last recollection was the sound of a cab-whistle and the jog-trot of a horse on the roadway.

It had all come back to him now. He was feeling a little dizzy and sick from the effects of the drug, but his head was rapidly clearing, and his courage came leaping to his finger-tips. At any rate, he had not been decoyed into any loathsome den, for the apartment in which he found himself was a singularly well-furnished one, and could only have belonged to a house in the best part of the West End. From the absence of noise, Clifford guessed that he was at the back of the house. He saw that the three windows were shuttered and fastened with iron bars. A closer examination revealed the fact that the bars had been screwed into the shutters. Also the heavy door was locked on the outside. All this Clifford found out for himself with the aid of a box of vestas, then his eyes fell upon the artistic arrangements of electric light, there was the snap of a switch or two, and the fine room was bathed in a flood of subdued illumination.

Clifford surveyed himself critically in a fine old Florentine mirror suspended over the fireplace. Evidently his captors had handled him more or less carefully, for, beyond a slight disarrangement of his wig, his disguise remained intact. He had probably been brought here and placed on the couch to recover from the effects of the drug. The more he looked around him, the more convinced he was that he had been forcibly conveyed to the house of someone who did not lack means and whose resources were ample. A box of cigarettes, flanked by a pint bottle of champagne and glasses, stood on a side table which in itself was an admirable specimen of Chippendale's earlier methods. "This is thoughtful," Clifford murmured to himself. "It would be ungenerous not to accept such a delicate hospitality."

Clifford drank the wine and smoked a cigarette in ruminative silence. It was borne in upon him presently that he was not alone in the house, as he had at first imagined. It had occurred to him that those who were in search of Levetsky had probably hired a house for the purpose of spiriting their prisoner away. But presently Clifford could hear the ripple of an electric bell, the opening and shutting of distant doors, and then a man's voice laughing heartily. The man was not alone, evidently, for his mirth appeared to be shared by a woman, whose delicate treble mingled musically with the bass of her companion. So far as Clifford could judge, the sound came from an adjoining room. Then, as his upturned glance detected a large ventilator, Clifford understood. The ventilator was open, and by means of a trinity of chairs it was possible to look into the next apartment.

This room was furnished, if possible, more luxuriously than the prison-house. A couple of servants in livery were engaged in removing the remains of an elaborate supper, round a card-table by the fireplace two men and two women were seated. Clifford's features expanded into something like a grin as he noticed the face of one of the men there, but the grin became a chuckle as he took in the woman with the diamonds in her hair. Clifford had made up his mind what to do. He removed the chairs and, crossing over to the fireplace, coolly rang the bell.

There was a sound presently as if the card-party had been disturbed; there was a click in the lock, and the door opened to admit a figure, tall and well proportioned. The newcomer was in evening dress; Clifford recognised him for one of the card-players.

"What do you want?" he asked haughtily. "There is everything here that you can possibly require; if you are disposed to be quiet, you will come to no harm for the present."

"It is not the present that troubles me," Clifford said. "I am thinking of the future. What are you going to do with me? I cannot remain here."

"You are not likely to remain here," the other said with a grin. "The air of this country does not agree with you; besides, you are too busy with affairs which should not concern you. Once you are back in Russia, we shall know how to deal with you."

"Oh, indeed," Clifford said drily. "You are perhaps aware of the fact that there is no extradition for political offences in England. "If I choose to object—"

"You will not be in a condition to object," the other man said. "Pouf! The thing is as easy as kissing you hand. You are our brother—our poor brother who is sick unto death. A little more or less of that drug with which you became acquainted to-night, and you are in a condition of practical insensibility all the way from London to Paris. We travel with a doctor from the Embassy who is certifying as to your condition. A little more of that drug, and you wake to find yourself in St. Petersburg. You understand?"

"Oh, precisely," Clifford said. "From your point of view the programme does not contain a single flaw. But in the first place I will ask you whom you take me for?"

The other man bowed and smiled. There was a strange, meaning look in his eyes.

"In diplomacy it is always well to be discreet," he said. "If I ask for you at your rooms, I inquire for Levetsky. I know you by no other name. St. Petersburg will know you by no other name. To go still further, Siberia will know you by no other name; and when you tell the governor of Tobolsk gaol that you are not Levetsky, but —er—a much more important personage, he will laugh at you and place your petition to the Czar in the stove."

"I need not go so far to petition the Czar," Clifford said. "A hansom cab would take me to His Majesty in ten minutes. Pshaw! Do you think I don't know that the Little Father is in Buckingham Palace at the present moment?"

Clifford was enjoying his part in the comedy immensely. He had thrown himself into the part of Levetsky heart and soul. It was a pure pleasure to him now to see the look of amazement and alarm which had spread itself out over the face of his companion.

"What I say is evidently news to you," he went on. "It is probably news to the Embassy also—but send Colonel Azoff to me."

"Azoff?" the big man stammered. "I—I don't understand what you mean. Besides, he is not—"

"Oh, yes, he is," CHfford cried. "He is in the next room playing cards with Countess Czerny. Tell him that if he doesn't come to me at once, nothing can save him from standing in Bow Street dock to-morrow morning on a charge of forging the signature of—well, we need not mention the name of the nobleman."

The listener passed his hand across his forehead as if to gather together his scattered thoughts. He muttered something under his breath and cast a malignant glance in Clifford's direction. Then he turned on his heel and left the room, carefully locking the door behind him. No sooner had he gone than Clifford buttoned the borrowed coat around him and removed every trace of his disguise, which he carefully stuffed away under the couch. He could hear the whispers and muttered conversation in the next room, but there was no more laughter and no further sounds of gay enjoyment. The key clicked in the lock again, and Colonel Azoff entered the room. Clifford was standing looking into the fireplace, so that it was impossible for the new-comer to see his face.

"What is the meaning of this?" Azoff demanded, "and who are you to send me so insulting a message, by—"

"Softly, my dear Colonel," Clifford said as he wheeled round. "You are always so headlong, so impetuous. You do not seem to realise that I have run a considerable risk, and incurred a considerable danger also, to see you to-night. But won't you sit down? It is so much better than standing."

No reply came from Colonel Boris Azoff, of the Czar's Household. He stood there gnawing at the end of his waxed moustache, his dark eyes fairly bulging from his head. He seemed utterly incapable for the moment of comprehending the fact of Clifford's presence. The latter lay back in an armchair in sheer joy of the situation.

"You are not well," he said. "Something seems to have upset you. You do not seem to understand why I am here—"

"But how did you get here?" the Colonel burst out at length. "We thought—we thought—that we had laid hold, but I must not mention that name. My dear fellow, you are in great danger here. You must get away at once. At any risks, I must clear you out of the house. This is no place for you."

"But where am I?" Clifford asked. "In what part of London?"

Azoff' made no reply. He seemed to be utterly lost in contemplation of a problem beyond his mental grasp.

"I must not tell you," he said presently. "I could not betray a confidence like that. There has been some terrible mistake here. In the exercise of our duty we have been endeavouring to lay hands upon—upon a man called Levetsky. I could have sworn to-night that I saw Levetsky carried into this room—"

"Impossible!" Clifton cried. "The man you call Levetsky is at the present moment at Buckingham Palace, where he is having an interview with your Emperor."

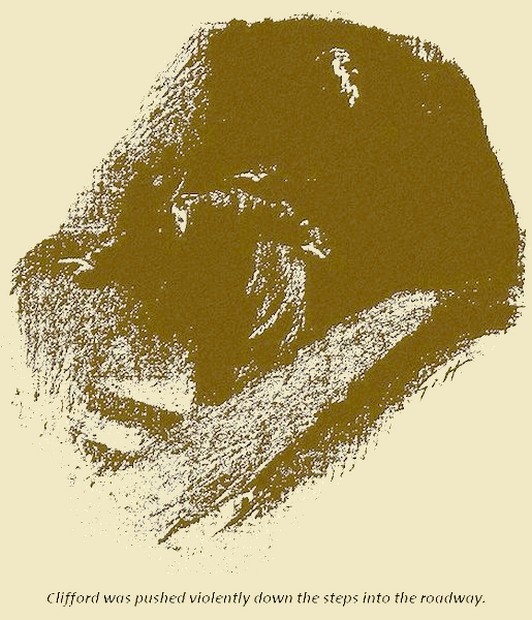

It was the crowning stroke in Clifford's little comedy. He saw Azoff stagger back as if he had been struck with a whip-lash. He saw the great drops standing out on the Russian's forehead. Then, with a wonderful effort, Azoff pulled himself together and threw the door wide open. Silently he beckoned Clifford to follow him into the great wide hall. A moment later and Clifford was pushed violently down the steps into the roadway, and the door was banged behind him. He could hear the shooting of bolts and the rattling of chains, followed by a long ripple of electric bells. Clifford could make out the outline of trees opposite, and a long row of fine houses stretching on either hand. It was just a moment before he could make up his mind to the exact locality in which he stood.

"Belgrave Square," he muttered. "795, Belgrave Square. I must not forget the number. I must find out who lives here. Hi, cabby! I want you to drive me as far as the office of the Morning Herald; an extra shilling if you get me there in twenty minutes."

The cabman grinned as Clifford jumped into the hansom, the horse's head was turned towards the East as they flew along.

WICKHAM was pacing restlessly up and down his office as Clifford came in and cast aside his slouch hat and cloak and demanded that someone should take a note to his rooms and procure him a shirt and collar.

"Oh, Heavens, yes!" Wickham said irritably. "You can have a whole hosier's shop if you like. But you look as if you have been having a good time of it. Only do get to the point."

"I have had an excellent time of it," Clifford said cheerfully. "But I know what you want. Our friend Levetsky has not come back, and you are worrying yourself into fiddlestrings as to whether or not you shall publish that important news about the Czar. Well, you can do it; it is absolutely correct."

"Is that really so?" Wickham exclaimed. "You are quite sure of it? But, seeing that there is plenty of time, you might just as well relate your adventures."

Clifford proceeded to tell his story at considerable length. He saw the face of his companion gradually clearing as he went on with his convincing narrative.

"Then I'll risk it," Wickham said. "There is only one thing wanted to round off the account perfectly. Of course, it is out of the question to believe that the man who calls himself Levetsky is no more than an obscure refugee who has suffered at the hands of the Russian Government. It is equally absurd to say that the Czar would come on a secret mission to England merely to meet this clever old man. If we could only get at his name—"

"I have," Clifford said coolly. "I am prepared to bet anything you like in reason that I can give you the proper name of the man who calls himself Levetsky. Mind you, it would be a distinct breach of faith on my part to do so without our mysterious friend's permission. But the first thing we have to do, it seems to me, is to find out who lives at 795 Belgrave Square. Just hand me over the London Directory, will you?"

The volume in question stood on Wickham's desk, and Clifford rapidly fluttered over the leaves. He was not a man usually given to the display of emotion, but his face was a study in astonishment as he bent down once again to read the figures.

"Well, if this doesn't beat me I " he cried. "Number 795, Belgrave Square, owner and occupier. Prince Boris Gassells. Good Heavens, Wickham, if you only knew what I know, what an eye-opener it would be for you! Of course, the name of Prince Boris Gassells is quite familiar to you?"

"Rather," Wickham said drily. "Why, he was the man who last year very nearly succeeded in bringing about a proper Russian constitution. If he had had his own way, Russia would have a parliament like England by this time. As it was, the old official party deliberately conspired to ruin the Prince, and he escaped with his life by getting away to England. I understand that when he arrived here he was practically penniless, for his estates were confiscated. Mark me, if that man had had a better chance, he would have saved Russia, and the official gang knew it. It is any odds, Clifford, that the Czar is here now with the sole intention of settling matters with the Prince."

"You've got it," Clifford said drily. "Wonderful what a grasp a journalistic mind has! At any rate, there is one thing you may be sure of—Levetsky will not return to-night, and you may set about preparing your big 'scoop' with an easy mind. I'll drop in and see you to-morrow evening, and I shall be greatly astonished if I am not in a position to afford you matter enough for one of the most sensational articles that ever bucked up the circulation of a newspaper. Good night."

* * * * *

London seethed with excitement next morning, once the true inwardness of page five of the Morning Herald was grasped. The air was full of rumours which were more or less dissipated as the day went on by an official acknowledgment of the fact that His Imperial Majesty the Czar had paid a flying visit to London for the purpose of consulting King Edward on matters of a private family nature. It was also intimated that the Emperor was already on his way back home, and that he was accompanied by Prince Boris Gassells, and that important constitutional changes were in contemplation. It mattered very little to Wickham what the evening papers had to say. They were welcome enough to their crumbs of late information, for the cake had been his. He was therefore prepared to receive Clifford in a genial frame of mind when the latter put in an appearance at the Herald office after dinner.

"I can tell you the story in a few words," Clifford said. "I gave you an elaborate description last night of what happened to me at that house in Belgrave Square. My main cause for astonishment was the audacious trick played by my friend Colonel Azoff and his companions on the man called Levetsky. Now, you told me that Prince Boris Gassells came to England a poor man. You had utterly forgotten that he used to spend six months of the year in London, and that he had a house of his own in Belgrave Square. After his disgrace he let the house furnished and thus found means to live. On this occasion the house was not let, and the Prince lived there in strict retirement with one old servant, occupying between them a small room in the basement. Colonel Azoff and the other man, whose name I cannot ascertain, wanted to get hold of Levetsky and take him back to St. Petersburg. I know how anxious they were to do that, or I should not have had so striking an adventure last night. But just mark the audacity of these people. They actually obtained possession of the Prince's house and conveyed Levetsky —that is, myself—there where no one would dream of looking for him. They were perfectly safe, as you will see quite plainly. But, mind you, they knew what I only discovered last night, and what you have suspected for some time—namely, that this so-called Levetsky was a man in a much higher position than he pretended to be. My dear fellow, you are very sharp as a rule, cannot you guess who our friend Levetsky really is?"

Wickham shook his head as if the puzzle was too much for him. He turned eagerly to Clifford for an explanation. The latter rose and walked excitedly up and down the room. "Why, the Prince himself, of course," he cried. "Azoff and his companions knew that all the time. They also knew that the Czar was in England, and they were perfectly well aware what he came for. As those people belong to the corrupt Court party, it was absolutely essential to move the Prince out of the way. Therefore they managed to get into his house and plant their own servants there. Then they, fearful perhaps that he should tumble to their scheme, set out to kidnap him and keep him a prisoner in his own residence. The thing was audacious and yet so absurdly simple. As soon as ever I looked at the Directory last night, I guessed exactly what had happened. I had my suspicions before, mind you, for I had a swift glimpse of Gassells when he was changing dresses with me. No wonder, my dear fellow, that this shabby old 'Levetsky' was in a position to come down to your office and give you these wonderful pieces of exclusive information. You will also see why he was so anxious for it to be known that the Czar was in London. Depend upon it, before many days are over, both of us will hear from St. Petersburg, from the Prince direct. And now, my dear chap, if you cannot make a really interesting column out of what I have just told you, why, you are not the brilliant and versatile journalist that I take you for."

Wickham grinned as he reached for a pad of copy-paper and a quill pen. The light of inspiration that gleamed from behind his golden spectacles was striking. He held out a warm hand to Clifford.

"I can't thank you now," he said. "I am going to be exceedingly busy for the next hour or two. Good night, my pearl of Secret Service agents, and pleasant dreams to you!"