THE woman sat there, flirting her fan to and fro listlessly, her dark eyes bent upon the stage as if she were absolutely lost in the brilliant new comedy which was being presented for the first time by the great actor-manager of the Comus Theatre. She lay back in her stall, haughty and listless and indifferent, as if compelled to admiration in spite of herself. She looked every inch the grande dame going through a round of pleasure and accepting it all entirely as a matter of course. She was beautifully, naturally dressed; diamonds shimmered in her dark hair; there was around her that nameless atmosphere which seems to always go with wealth and breeding. She might not have had a single care in the world; she might have been one of those spoilt darlings of society for whom, presumedly, Providence has intended the universe, to the exclusion of all others. Despite her coldness and her beauty and her air of absolute aloofness, there was now and then a flicker of the delicate nostril and a tightening of the haughty mouth which told of pain, either physical or mental. She laid her fan down upon the vacant stall on her left and clasped her long-gloved hands together.

There were several people in the theatre who had regarded more or less curiously this dark, stately beauty sitting there all alone. It was possible to speculate as to the meaning of the empty stall by her side. There was admiration as well as envy and sundry glances cast in her direction, and yet at that moment Stella Clinash would have been perfectly willing to have changed places with the humblest little domestic servant perched up far above in the roaring red atmosphere of the gallery.

She was glad now that her husband had not come. She was fiercely glad that Clive Clinash had stayed away. He had meant to come with her, of course, for the Clinashes were alone in London. They were only over from Buenos Ayres for a short stay. They had intended to get back to South America in the course of a day or two. Almost at the last moment there had come a telegram from Clinash to the Dominion Hotel, where they were staying, saying that he had been detained on important business and would probably join his wife in the theatre a little later on.

She had been rather glad to get this message. Sooth to say, she was a little tired of sight-seeing; she would have preferred an evening at home in her own sitting-room. But, then, there was the chance that Clinash would go straight to the theatre, and he would be greatly disappointed to find his a wife absent. Therefore she had gone alone, with that strange feeling upon her that something was going to happen. It seemed to her that she had never hated London so much as she did at that moment; it seemed to her that it would have been far wiser to remain at Buenos Ayres, but Clinash would not hear of it. Besides, they had only been married a few months, and Stella Clinash had always been a solitary woman, and when she had come to find a home and husband she clung to both with a tenacity and passion which, at times, fairly frightened her. Like most people who pass for being cold and self-contained, she had depths of feeling and emotion of which Clinash, with all his love and admiration for her, knew nothing.

And he had taken her on trust, too. He had found her eighteen months before, getting a precarious living in London as an addresser of envelopes. He had fallen in love with her on the spot, and had, in his impetuous way, asked her to marry him. Just for the moment she had hesitated. There were reasons why she should have refused. And yet, when she came to think of the drab monotony of the life that lay before her, she hesitated no longer. She wanted someone to lavish her affection upon, and here she found him. For Clinash was rich and prosperous, he was young and fairly goodlooking, and—well, there was only one end to a struggle like that.

And now all the misery and unhappiness had gradually faded like an ugly landscape blurred in a cloud of mist. The ice had gradually melted from round Stella's heart until she could stand there in the sunshine of her own happiness and wonder what she had done that God should be so good to her as all this.

That was up to a few moments ago. And then she had seen him standing there by the entrance to the stalls, glancing casually round the theatre as if he were in some way connected with the management. He stood there neatly dressed in a dark frock suit, a glossy hat was perched upon his head, and his round, hard face and keen grey eyes seemed to be taking in the whole audience. Stella Clinash recognised him at once. She would have recognised him anywhere and in any circumstances. There were no delusions in her mind on the score of his failing to remember her. She felt his eyes running the measure of the rule over her, she saw him turn and say something to a theatre attendant, then presently he vanished and another man suspiciously like him took his place. There was no facial resemblance between the two, but they were both cast in entirely the same mould, both of them trim and clean and reserved, both of them speaklng of the Criminal Investigation Department of Scotland Yard to anybody who had ever had any contact with that dread institution. And although the second man never for one moment looked in Stella Clinash's direction she knew perfectly well that he was waiting for her, and that she would have to speak to him before the performance was over.

Well, the thing was finished now. She had had more than a year on the other side of the golden gates, and now the barriers of desolation yawned before her. And the strange thing was that she was not frightened, she did not seem to be in the least alarmed, or angry, or unhappy. She had been the sport of Fate too long to accept a blow like this with anything but resignation.

Clive would have to know. Indeed, she blamed herself now for not telling him before. But she had been afraid to do so; she had been afraid to risk the happiness which had suddenly opened before her in such dazzling splendour. She had temporized, and the time was lost, and now it was too late. Still, she must let her husband know, she must prepare him for the inevitable. It would never do for her to bring disgrace upon his honoured name. He must abandon her to her fate, he must never see her again; no one must know that guilty secret but themselves. And perhaps, when she had served her sentence out, he might be disposed to remember that for over a year she had been a good and faithful wife to him. He might be willing to make some provision to save her from want in the future. Fortunately, they knew nobody in London; it would not be an easy matter to trace her back to the Dominion Hotel, and Clive would be clever enough to hide all her tracks. Of course, he would be sorry, for she knew how genuinely fond he was of her; but at the same time his good name must not suffer, and in that respect she would help him to the best of her ability. Why, oh, why had she returned to England at all? Clinash's own call had been imperative—a business crisis that demanded his presence in England. Most men have these moments of commercial peril. And she had risked it all to be with him—not to lose a moment of her glorious happiness, as a love-sick girl might have done. Oh, the incredible folly of it!

She ·had thought it out now. She waited till the curtain fell on the third act, then she beckoned a programme-seller in her direction. From her purse she took out a half-sovereign and placed it in the girl's hand.

"Don't ask any questions," she murmured. "Procure me at once a sheet of paper, an envelope, and a pencil. I am going to write a note which I want delivered at the Dominion Hotel at once. If you can manage this for me the half·sovereign is yours. All I ask you to do is to be silent and say nothing of this."

The girl nodded. Perhaps the request did not strike her as being particularly strange. She came back presently with writing materials, and Stella Clinash wrote her letter. It was characteristic of her that her handwriting was firm and neat, that the letter was perfectly coherent and collected.

"There," she whispered; "will you take that now?"

"At once, madam," the girl replied. "You can rely upon me. Besides, I am going that way."

The comedy was drawing to a close now. Stella Clinash looked at the watch on her wrist, and saw that it was half-past eleven. No doubt Clive had received her letter an hour before. He would have made up his mind by this time exactly what to do.

Already some of the audience had begun to leave the theatre. She rose calmly and drew a wrap round her shoulders and over her head. Then she walked quite steadily and collectedly through the vestibule up to the folding doors, where the man with the hard, keen face appeared to be awaiting someone. Stella drew a little quick breath, and her lips quivered as she touched the man on the shoulder.

"I think you are waiting for me," she said, quietly. "I don't happen to know your name, but you recognise me."

The man turned and smiled good-naturedly.

"Detective-Sergeant Swift," he said, tentatively. "You are Stella Treherne. Rapson asked me to wait here. He recognised you, though, as a matter of fact, he was looking for somebody else. Hard luck, isn't it?"

The man spoke in a friendly enough tone. There was nothing of the traditional man-hunter about him. He was merely a machine cut and drilled and polished to a diamond hardness. Possibly in private life he was as generous and good-natured as other people. But he had his duty to perform, and he meant to do it.

"I don't want any sympathy," Stella said, coldly. "I am quite prepared to take the consequences. And yet, if a thousand pounds would be the slightest good to you, I am prepared—"

Swift turned aside apparently unheeding.

"Don't say that," he whispered. "Because you see, it would make no difference. And if I mentioned it to the magistrate tomorrow morning— But perhaps I didn't exactly catch what you said. Would you like a cab?"

"That is kind of you," Stella said, in the same strangely even voice, "I suppose I ought not to blame you so much as the iniquitous system of which you are at once the slave and tool. Of course, I must have a cab. I could hardly walk through the streets to the police station dressed like this."

"Of course not," Swift agreed. "But wouldn't you like to go anywhere first? Would it not be as well to get as far as your hotel or your rooms, where you can procure a change of clothing? Of course, it is no business of mine to pry into your present position, but, judging from what one can see, matters appear to have gone very well with you of late. I presume you are married?"

The blood Hamed into Stella's face.

"Is that necessary?" she asked.

"Well, of course not," Swift said, with some sign of confusion. "But we flatter ourselves we can always tell the difference between the woman who—well, you know what I mean."

"I am obliged for your good opinion," Stella said, calmly. "Married or not, at the present moment I am a woman who has to face a trouble entirely alone. And I have done no wrong; or, at least, if I have, I have paid for it dearly enough, God knows. Why do you hunt us like this? Why don't you give us a chance to lead a clean and honest life? Why should we be dragged month by month to report ourselves at the nearest police-station? You know it always results in the same exposure. Our employers get to hear of it, and the same weary struggle begins over again. I am sure that two-thirds of the criminals on ticket-of-leave find their way back to jail again simply because of this cruel system of yours. It would be far kinder to keep us under lock and key till the sentence is worked out. As a sensible man, you must know I am speaking the truth."

Swift shrugged his shoulders. It was not for him to question the iconoclast* methods of his department. He was a mere pawn in the game of diabolical chess which the police are unceasingly playing with the criminal classes. And, besides, he had expected some sort of passionate outburst like this. They mostly behaved in the same fashion. The people were beginning to pour out of the theatre now. Stella standing there, tall and slim in her white dress, was attracting attention. A cab came up, and Swift stood aside for Stella to enter.

[ *"iconoclast" (sic) - perhaps a typographical error for "iron-clad." ]

They drove along silently through the well-lighted streets. They passed the portico of the Dominion Hotel, where the porter was standing with his hands behind him. As the great front of the building stood out red and bold Stella caught her lip between her teeth and blinked the tears from her eyes. But she was not going to give way, she was not going to pity herself. She had played her game and she had lost it, and she was prepared to pay the price. Still, she turned cold and faint and dizzy as the cab pulled up presently outside a police—station. There was something horribly familiar about the place, something so repulsive about the whitewashed walls and the bare, clanging passages. A couple of policemen sitting there in the charge-room, stolidly eating their suppers, looked up with a certain languid curiosity as Swift and his prisoner entered. But they were too used to these fiery, dramatic entrances and exits to do more than take in the details of the woman's dress and the cold, proud frostiness of her face. An inspector sitting behind the table glanced interrogatively at Swift.

"Stella Treherne," he said. "Charged with failing to report herself. Released on licence about twenty months ago and only been heard of once since."

The inspector bent over the table and scribbled something on a sheet of paper. From his point of view it was all a matter of business. Had Stella appeared there either in rags or in silken attire he would have displayed the same lack of interest or emotion.

"Want to send for your friends?" he asked. "You can't appear like that to-morrow morning, you know. What is your address?"

"My address is refused," Stella said, quietly. "You know my name, and that is sufficient. As to the rest, I must make the best of it. There are reasons why I cannot give you my address—imperative reasons why my present friends must not know what has happened to me. I have money in my purse. I suppose I can keep that, and perhaps one of the female warders will get me something from one of the adjacent shops in the morning. As there is no charge against me, except for failing to report myself, I must ask you to let me retain possession of my money."

The inspector scraped his jaw thoughtfully.

"Seems reasonable" he said. "Very well; we will do what you require. Is there anything you would like before morning? Perhaps you would like to send out for some food?"

Stella fairly shuddered at the suggestion. The mere notion of food filled her with loathing and disgust. There was absolutely nothing she wanted, she said. Her one desire was to be alone. In a dreamy kind of way she followed a policeman presently along an echoing flagged passage. She heard the quick turn of keys in well-oiled locks, she was once more back in those horribly suggestive environments where life has lost its savour and where the word "hope" becomes no more than a mocking, empty sound. All that banging of doors and clicking of keys seemed to be superfluous; such a waste of strength and tyrannical grip to hold one so small and crushed and miserable in durance vile. She had no inclination to shirk the inevitable. Had all the doors been thrown wide before her she would have made no attempt to escape now. For what good would such a thing have been? By this time her husband knew everything and he would act accordingly. Already she was beginning to think of him less now as her husband than as Clive Clinash. She would never see him again. It did not seem to her that she wanted to. At all hazards now, she was going through with it to the bitter end. She would be sent to one of those dreadful convict prisons, there to serve out the rest of her sentence. But, at any rate, after that she would be free; her term of imprisonment embraced no subsequent police supervision. Once it was over and done with she could go where she liked and do as she pleased.

She sat down there with ber head in her hands on that cold, hard travesty of a bed, the like of which she knew only too well. From time to time she could hear the heavy tramp of feet along the corridor; from time to time some drunken woman prisoner burst into horrible screams. Now and again from a cell close by a man was singing a snatch of comic opera in a pleasant tenor voice. Then gradually the sounds died away, and in an uneasy manner Stella slept.

She woke presently chill and cold in the grey dawn, and the whole thing came back to her with overwhelming force. She was hungry now, and yet the mere thought of food was repulsive to her. Gradually the atmosphere grew warmer. She could hear sounds of life and movement about the place. A little later the door of her cell opened and a hard-featured woman looked in. She threw a bundle on the floor, with an intimation that everything necessary was there, and withdrew. · Here was a chance to do something, however trivial, to pass away the time. Stella's rings and jewellery had been taken possession of the night before, but her dainty dress looked hideously grotesque in the pale light of the morning. She stripped it off and cast it aside as if it had been some loathsome thing. She was almost thankful to find herself in coarse, ill-fitting black garments, with a plain straw hat. At any rate, there was no chance of any acquaintance recognising her now. There would be no opportunity for the sensational joumalist to make half a column of copy out of her story.

The time had come now. She was walking across the courtyard. She stood presently in a dreamy kind of way with her hand clasping the dock; she heard her name mentioned, then the magistrate appeared to be asking her a question.

He was a kindly-looking man, and Stella took fresh heart of grace.

"Come," he said, "I am waiting for you to speak."

Stella looked up dreamily. The question seemed to be floating around the roof of the court before it reached her ears. She had been watching a bee climbing up one of the windows, fighting angrily for liberty; she was intensely interested in the efforts of the little insect. Would it manage to reach the ventilator or not? she wondered. She was more concerned with this now than with her own future. She was quite anxious about it. She gave a little sigh of relief, at length, when the bee reached the opening and sped away into the open air. Then it was that Stella came back to herself, and the knowledge that the grey-haired old gentleman opposite to her was asking her questions, and looking at her not unkindly from behind his spectacles.

"I don't know," she murmured. "I beg your pardon; I was not listening."

"What have you, then, to say?" the magistrate asked.

Stella shook her head wearily. What was the use of saying anything? She knew perfectly well that any plea for mercy on her part would pass unheeded. After all said and done, the police were doing no more than their duty. It was all part of the diabolical system, part of the constant warfare which went on between the law and the criminal. She would have to go back and finish her sentence. She had been warned on the first day of her liberty that there would be no trifling in this matter. She had lost everything now, position, reputation, husband, all at one feel swoop. There was nothing more to be said or done.

The magistrate still paused. So far as Stella was concerned, she had lost all interest in the proceedings. Somebody had jumped up in the well of the court below the dock and commenced to address the magistrate. He spoke clearly and well; evidently he was quite at home with this kind of work. In the same dreamy, half—blind fashion Stella could see that his shrewd, clean-shaven face was kindly enough. She gathered that he was saying something on her behalf. She heard this advocate of hers addressed presently as Mr. Hallam. She wondered in the same dull, groping way where she had heard the name before. Then it flashed upon her that this was a famous barrister whom she had read of over and over again. She knew that he was a man at the head of his profession; she realized that he would not have left other and more important work had not his fee been a handsome one. There could be no question as to who had procured the services of Mr. Hallam, K.C. Her husband must have sent him, and in a way Stella felt grateful.

She glanced wearily round the court to see if she could see Clive anywhere, but he had not put in an appearance. He would never forgive her, of course, he would never want to see her again; but that would not necessarily prevent him from acting a noble, manly part, and doing everything he could to lighten her sentence. She was more interested now; she began to follow eagerly and carefully what Hallam was saying.

"With all due respect, sir," the advocate said, in his smooth tones, "with all due respect, I urge this as an exceptional case. As to the facts stated by the policel have nothing to say. My unfortunate client was certainly convicted at the Old Bailey four years ago on a charge of fraud and conspiracy under her maiden name of Treherne. As a matter of fact, there would have been no sentence of penal servitude if the prisoner had not been identified by the police with a certain notorious woman criminal whose name it is not necessary to mention. That was quite a mistake, and would have been shown at the trial had my client been properly represented. I appeal to Sergeant Swift, who has charge of this case, to confirm this statement. It was only after my client disappeared that these facts came to light."

"That is so, your worship," Swift admitted.

"An unfortunate mistake was made. We did our best to find the prisoner after she vanished, but without effect. But that does not touch the present charge—the charge that the prisoner failed to report herself and rendered herself liable to arrest and to be conveyed back to prison, there to serve out the balance of her sentence."

"Oh, I am not contesting the point," Hallam cried. "I am entirely in the hands of the Court, but I have proved that a cruel mistake has been made, and that my client ought never to have been sentenced to penal servitude at all. It is not for me to question the system which compels criminals on licence to report themselves to the nearest police-station, but I do say that in certain cases it is harsh and unnecessarily brutal. Take my client's position as an instance. For a year after she came out of jail she had an exceedingly bitter struggle to live, but there was nothing against her, and when the opportunity came for turning her back upon England, when she had a chance of a happy marriage and a new life in a foreign country, the temptation was too much for her. My client is well-born, she was carefully brought up, and yet she knew what it was more than once to spend the night out of doors. Think of the temptation, think of the opportunities! How many women would have hesitated? I venture to say, not many. She never told her husband. It is only within the last few hours that he has made this terrible discovery. And he is is man in an exceedingly good position in South America; he is rich and respected. He would have been here to-day, but he is utterly overcome by this unexpected revelation, and unfortunately he cannot get here. If your worship likes, I will hand the name up to the Bench. You will quite see there is nothing to be gained by making my client's husband's name public."

"Is this a fact, Mr. Hallam?" the magistrate asked.

"I give you my word for it, sir," the barrister responded. "My statement will probably be confirmed by the circumstances in which my client was arrested last night. Now I am going to ask you, sir, to exercise your discretion in this case and allow this lady to be released on her own recognisances. When you have read the name which I propose to write down for you—"

"No," Stella Clinash cried, suddenly, "I implore you not to do anything of the kind. I would rather suffer any humiliation than allow my husband's name to be dragged into this business. I am quite prepared to face the consequences of my folly. I shall never see my husband again. He will never want to see me. I greatly regret that he should have sent this gentleman here to-day. Oh, can't you see that I wish to get this over as soon as possible? Can't you see what an unspeakable humiliation this is to me? Send me back where I came from. At least I shall be beyond the reach of starvation there. I was not so guilty as they said; I was the tool of others, though I do not want to shirk my responsibility. I deceived my husband, and that is the knowledge that hurts me most."

The passionate words rang through the court; the few reporters and the handful of the public present followed with breathless interest. Here was an unexpected human drama unfolding itself before them—a story more profoundly tragic than anything ever yet seen upon the stage. Stella ceased to speak; a silence fell upon the Court. It seemed to her that she had the sympathy of everyone present.

"This is unusual," the magistrate murmured. "I am sure this unfortunate lady will think better of what she says when she has time for consideration. I cannot blind myself to the fact that had the true facts of the case come out during the trial she would not be here at all. Also, I have not overlooked the inspector's statement that there is nothing against the prisoner since she came out of jail. After all said and done, it is merely a technical offence which has been committed, and I think the interests of justice will be served by a nominal sentence of a day's imprisonment—in other words, the prisoner is free to leave the dock now."

Stella seemed barely to comprehend. There was something like a murmur of applause from those present in the court. A warder touched her on the arm and intimated that she might go. She did not seem quite to understand what the sentence meant. She stood there dazed and confused in the body of the court, trying to collect her scattered senses. Her advocate was still addressing the Bench. He wanted to know if this persecution was to continue. He desired to know whether application would be made to the Home Secretary to remit the inconvenience of these periodical calls upon the police. The magistrate shook his head doubtfully.

"That will be in your own hands, Mr. Hallam," he said. "I presume the police would raise no objection. They have no desire, of course, to turn this into a persecution."

"I am obliged to you, sir," the barrister said. "I may assume, therefore, that so long as my client is outside the jurisdiction of the Court no steps will be taken."

The magistrate shook his head with a smile.

"Ah, now you are assuming too much," he said. "I think you have no cause to be dissatisfied. Next case, please."

Stella wandered slowly out of court. She stood in the open air, undecided as to what to do or where to go next. She seemed to understand that Hallam wished to speak to her. He was asking her to wait for one moment, and then he had certain things to say.

Stella murmured something; she hardly knew what it was. She was free to go now. She had all the world before her. There were just a few shillings in her pocket. All she wanted now was to be alone, to get away from all who knew her, to start life afresh. She turned and' walked rapidly down the street until she came into the thick of the traffic; then she drifted on the breast of the tide—a human derelict, alone and friendless.

"I shall manage," she murmured to herself. "It can be no worse than it was before."

It was a warm night, fortunately, so that it would be no great hardship to sleep out of doors, and anything was better than the foul, horrible den in which Stella Clinash had passed the last two nights. Her money was all gone now, with the exception of one solitary sixpence, to which she clung tenaciously. She was tired and worn out. Her one desire was to fall down somewhere and sleep. She walked along the Embankment, looking in vain for a quiet corner where the lynx eye of the law might possibly overlook her.

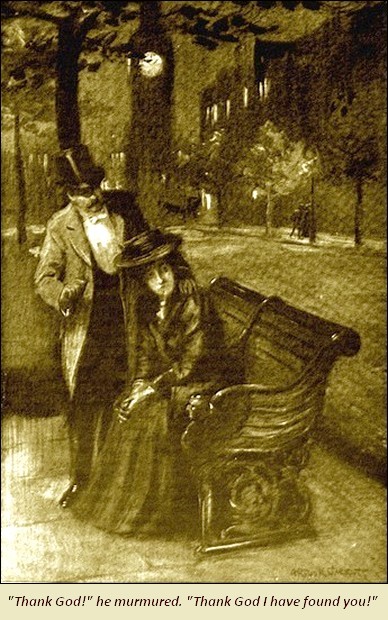

The clock at Westminster was striking ten, the Embankment was more or less deserted, save for a hansom cab or two taking more fortunate people to some place of amusement. Here was a seat at length where Stella could sit down and rest her weary limbs. She lay back there drowsy and half unconscious. She wondered vaguely what this man was doing, this man who was moving from seat to seat closely scrutinizing the miserable outcasts who were resting there. She could see that he was well dressed, that he was wearing a light coat over his evening clothes. Then something rose in her throat and her heart gave a great leap as she recognised her husband. She bent down so that he might pass. Surely he would never recognise her in the ugly black garments which she wore. But all the same he paused before her, and then, as if sure that he had come to the end of his search, he laid his hand upon her shoulder.

"Thank God!" he murmured. "Thank God I have found you! I have been searching high and low for the last three days. It is only by a mere accident that I have come across you now. Come along."

"Come," Stella asked, vaguely, "where?"

"Oh, not here; this is no place for explanations. Good heavens, do you suppose I am so black and hard as to desert you like this? When you know everything you will see I am more to blame than yourself. But come along, everything is ready. I have moved to another hotel. Nobody knows that you are the wife of Clive Clinash. Directly I got your note I sent your maid away on a pretext. A telephone message will fetch her at any moment. I have moved everything to the Blenheim Hotel. They think I am expecting my wife every hour. Come, you can change and dress, and we can have supper. Oh, my poor child, how white your face is! What awful rings you have under your eyes! Why, you are starving."

All this in a voice of infinite tenderness and feeling. Stella had risen to her feet. She could see nothing of her husband's face because her eyes were blind with tears. She wanted to run away; she wanted to leave him there and hide herself once more under the cover of the darkness. But she was too weak and spent for that—too tired and worn-out to make even the semblance of a struggle.

When she came to herself again her head was on her husband's shoulder; she could feel his strong arm about her. She was being half led, half carried. She was in a hansom presently; she could hear the click-clack of the horse's hoofs on the asphalt. Then she was passing through the brilliantly-lighted vestibule of an hotel. She was in a luxuriant bedroom with all her own things about her. Here were her jewels and her silver toilet accessories. Here was the warm bath that she needed. Then presently, in the same aesthetic dream, she found herself looking at her own slim, graceful prcsentment in a looking· glass.

The diamonds were in her hair again, a bunch of yellow roses nestled at her throat. There was a smile on her trembling lips now, the dark eyes were liquid with happiness despite the black rings below them. And yet Stella was full of contempt for her own weakness, half ashamed of a resolution she had made because she knew that it would never be carried into effect. It was good, oh, so good of Clive to treat her like this, to say nothing of the past, never to allude even by so much as a look to the disgrace which she had brought upon his good name. And here he was again with his arm about her waist gazing fondly into her face. He was seated opposite to her now at the supper-table, and Stella was eating as, it seemed to her, she had never eaten before. The events of the last three days seemed to be disappearing like the mists of some hideous nightmare, they seemed to be drifting into space.

The table was cleared presently and they were alone in that luxuriously-appointed sitting-room, where the lights were discreetly shaded and the soft gloom invited confidence and the opening out of hearts.

"Aren't you going to scold me?" Stella whispered. "Do you know what I meant to do? I meant to go away and never see you again. I meant to disappear and fight my own battles in the future, because I have treated you abominably, Clive, and I am not worthy to be called your wife; but the temptation was so great, the life I had led so awful, and—well, I really and truly loved you, and I can think of no better excuse than that. You may think that I was cold and reserved, but behind it all—"

She paused, and for a moment it seemed as if she had no more to say. What more was there to say?

"I know, sweetheart," Clinash murmured, "I know. I heard all that happened in court the other day, and I believe I read your mind then as if it had been an open book. And because you are so weak I love you so well. It is good to know that you were so ready to come back to me. Perhaps the knowledge of it flatters my vanity. But that matters little or nothing, because from the very first you never deceived me at all. When I married you in London eighteen months ago I knew the history of your troubles as well as I know it now. I was aware even then of the cruel injustice of your sentence. But I did not tell you I knew, because—well, why should I torture you? Perhaps I thought that if I let you know you would have refused to become my wife. But if I had foreseen this I would have sacrificed everything rather than imperil your future. I know that that was a mistake now. But you longed to come, and I—well, every man in love is a fool sometimes."

Stella looked into her husband's face wonderingly.

"You knew?" she murmured; "You actually knew? Oh! you are not deceiving me, Clive? You are not trying to make the way smooth and pleasant for me?"

"My dearest, I am telling you no more than the truth. The first time I ever saw you was in court on the day of your trial. I think I fell in love with you then. It might have been love born of pity, but it is none the less true and sincere for that. And I felt then, as I feel now, that you are the victim of circumstances, and that the man who was really behind that conspiracy took advantage of your lack of knowledge to get you to alter the date on those telegrams for him. Of course, you were not blameless, but you were more of a child in the matter. And in the interest I had in watching your case I forgot for a moment my own troubles."

"Your troubles," Stella murmured; "what were they?"

"Well, simply that I was practically a prisoner, too. I was out on bail; I was waiting to be tried. My case came actually next to yours. Oh, it was a bad business, and I am making no attempt to palliate it, but it was the only slip I ever made in my life, and I registered a vow there and then that when I came out of jail I would seek you out and make you my wife. It seemed to me that we had much in common, that we should have nothing to reproach one another with. And when I did come out the struggle was too hard for me to think of anything but bare existence. Like you I felt the iniquity of that reporting system, and like you I deliberately broke it. I had marvellous luck abroad, and in a few months I came back a rich man. The rest you know. And you know now why I dared not appear in court the other morning, why I had to keep out of the way for fear that I should be recognised too, and for fear that our happiness would collapse altogether. For your sake I had to take risks. But it turned out for the best. Luck was on our side for once. And, you see, I must get back to Buenos Ayres without delay. My whole prosperity turns upon it. And now I must ask you to forgive me."

"Is there any question of forgiveness between us?" Stella said. The tears were running down her cheeks now. "Do you know, I am almost glad. It seems a strange thing to say; but I am. And now, when do we sail? I shall know no happiness while I remain in this country."

Clive stooped and kissed his wife.

"To—morrow," he whispered. "I have arranged that. And all our future is bound up in that word—to-morrow."