"DO you wish to speak to me, General Sherlock?"

"My dear boy, I desire to do more than that," the veteran replied. The white head was bent, the tired eyes were heavy with trouble. "I wish to save you from a ghastly tragedy."

There was a nervous thrill and intensity in the words enough to carry force under any circumstances, but, coming from one absolute stranger to another, they seemed to bite into Ralph Cheriton's consciousness like a saw.

Yet, under other circumstances, he would have laughed. But a gentleman does not usually deride the beard of the veteran who has seen sixty distinguished years in the service of his country.

"These are strange words, General," he replied.

The war-worn soldier sighed. His hair was white as the Afghan snows, his face was covered with deep lines; what the man had once been was mirrored only in his eyes. And those eyes were unutterably sad.

"You are absolutely a stranger to me," he said. "Beyond my own household, I have seen no fresh face for years. My excuse for calling upon you is that this house once belonged to my family. An aunt of mine died here, my grandfather died here—he committed suicide."

"Indeed!" Cheriton murmured politely.

"Yes, he threw himself out of the dormer window, at the top of the house. Within a year, two uncles of mine and an old family servant also committed suicide in a precisely similar manner. I make no attempt to explain the strange matter—I merely state the fact."

"A most extraordinary thing," Cheriton replied.

"More than extraordinary. Do you know that I often dream of that dormer window in the night, and wake up with a strange longing to come here and throw myself out, as my relatives did before me? One night, in the Afghan passes near Kandahar, the impulse almost deprived me of reason for a time. Now you know why that window was bricked up."

Cheriton was profoundly impressed. He would have repudiated any suggestion of superstition, the hard enamel of a hard-ended century had long been forged over that kind of folly. Still, the fact remained. Only recently Cheriton had sold out of the Army and purchased Bernemore House, the scene of the tragedies mentioned by Sherlock. Of the evil reputation of the dormer window he had heard nothing. The fret of seventy years had rubbed the story from the village tablets.

It was a little disturbing, because for some time Cheriton had had his eye on that built-up dormer window. It was a double one and a fine bit of architecture.

Accommodation downstairs for the irresponsible bachelor was limited, and it seemed good to Cheriton to unseal the windows and make a luxurious smoking-lounge of the room originally lighted by them. This thing had been done, and only the previous evening the room had been greatly admired by such men as were even now staying in the house.

"Only yesterday I heard what you were doing," the General remarked, after a long pause. "Believe me, it is painful to drag myself thus from my solitude. But my duty lies plainly before me. To sit down quietly and allow things to take their course would be murder."

Sherlock's words thrilled with an absolute conviction. There was none of the conscious shame of a man who whispers of Fear in the cold ear of Courage.

"But, surely, General," Cheriton stammered, "you don't suppose that this family curse, or whatever it is, holds good with strangers?"

"Indeed I do, Captain Cheriton. Did I not tell you that a valued old servant of our family met his death in the same horrible way?"

"But his mind might have become unhinged. You are, of course, aware that suicide sometimes takes the nature of an epidemic. No sooner does a man destroy himself in some novel way, than a score of people follow by example."

A little pool of light glittered in the General's eyes.

"You are an obstinate man, I see," he said.

"Well, I like to get to the bottom of things. To be perfectly candid, if I do what you suggest, I shall be laughed at. It is only a very brave man, or a very great fool, who is impervious to ridicule. And I'm bound to confess to a strong desire to investigate this business further."

"Then you won't close that window again?"

"General, this is the beginning of the twentieth century!"

General Sherlock drew himself up as if shaking the burden of the years from his shoulders. He seemed to expand, his voice grew firm, the tiny pools in his eyes filled them with a liquid flame of anger.

"I see I must tell you the whole shameful story," he said. "My duty lies plainly before me, and I must follow it at any cost. My grandfather was an unmitigated scoundrel; he broke his wife's heart, he drove his daughter and his sons from him. There was also a story of a betrayed gipsy girl, and a curse—the same curse that was to fall on this house and those who dwelt there for all time—but I need not go into that. For years my grandfather lived here alone, with an old drunken scoundrel of a servant to do his bidding; indeed, it was rarely that either of them was sober."

The General paused, but Cheriton made no response.

"Well, the time was near at hand when the tragedy was to come. It so happened, one winter evening, when the snow was on the ground and the air was cold, that a coaching accident happened hard by. It so happened also that one of the injured was the daughter of my grandfather, to whom I have already alluded. She was badly hurt, but she managed to crawl here for a night's lodging. It was quite dark when she arrived, dark and terribly cold. Ill and suffering as she was, my poor aunt was refused admission by that scoundrel; they thrust her out in their drunken fury, to perish if she pleased. She staggered a few yards into the courtyard, she lay down with her face to the stars and died. No words of mine could convey more than that.

"The room with the dormer window was my grandfather's den. It was late the following afternoon before he came from his debauched sleep; the setting sun was shining in the courtyard as he looked out. And there, with a smile upon her face, lay Mary Sherlock—dead.

"A cry rang through the house, the cry of a soul calling for mercy. Then, in a dull, mechanical way, the wretched man drew to the window, he flung back the leaded casement, and cast himself headlong to the ground. Then—"

The General paused, as if unable to proceed, and held out his hand.

"I can say no more," he remarked presently. "If I have not convinced you now, then indeed my efforts have been wasted. Good-bye. Whether or not I shall ever see you again rests entirely with yourself."

"I am not unmoved," Cheriton replied. "Good-bye, and thank you sincerely."

Under ordinary circumstances they were a cheerful lot at Bernemore. Cheriton was a capital host, he chose his company carefully, and Ida Cheriton, a wife of six months' standing, had charms both of wit and beauty.

She looked a little more dainty and fragile than usual, as she sat at the foot of the dinner-table; her grey eyes were introspective, for there was another joy coming to her out of the future, and it filled her with a soft alarm. In her own absent fit she did not notice the absence of mind of her husband.

It was summer time, and no lights gleamed across the table, save the falling lances of sunshine playing on flowers and bloomy grapes. The air was heavy with the fragrance of peaches and new-mown clover.

There were perhaps a dozen people dining there altogether. Dixon and his wife, of Cheriton's old regiment; Michelmore the author and his bride, with a naval lieutenant named Acton, and Ida Cheriton's brother Charlie, a nervous, highly strung youth, with a marvellous record still making at Oxford.

"What's the matter with Cheriton?" Acton demanded, when the last swish of silk and muslin had died away. "Pass the cigarettes, Dixon. Out with it, Ralph."

"I dare say you fellows will laugh at me," Cheriton remarked sententiously.

"I dare say," Acton replied. "I laugh at most things. You don't mean that you have found a tame ghost or something of that kind."

"It isn't a ghost, it's a story that I heard to-day. I'm going to tell you the story, and then you can judge for yourselves."

Cheriton commenced in silence, and finished with the same complimentary stillness. On the whole, Acton was the least impressed.

"I am bound to confess that it sounds creepy enough," he remarked. "But a machine-made man can hardly be expected to swallow this kind of thing without a protest. I'll bet you on one thing—no unseen hand could ever lure me to chuck myself out of that window."

"I wouldn't be sure of that, Acton," Michelmore said gravely.

"Ah! you're a novelist, you have a profound imagination. A pony I sleep in that room to-night, and beat you a hundred up at billiards before breakfast to-morrow."

No response was made to this liberal offer, for latter-day convention is not usually shaken off, influenced by neat claret imbibed under circumstances calculated to cheer. Only Cheriton looked troubled.

"Well, somebody's got to knock the bottom out of this nonsense," Acton protested. "General Sherlock has done some big things in his days, but he's eighty years of age. Let us go up to the smoking-room and investigate. There's a good hour or more of daylight yet, and we may find something."

With a certain contempt for his own weakness, Cheriton complied. Once in the room, he could see nothing to foster or encourage fear. The apartment was furnished as a Moorish divan; it was bright and cheerful. From the dormer window a charming view of the country was obtained. Acton threw the casements back and looked out. His keen, sunburnt face was lighted by a dry smile.

"Well, how do you feel?" asked Dixon.

"Pretty well, thank you," Acton laughed. "I have no impulses, nor do I yearn to throw myself down, not a cent's worth. Come and try, Charlie."

Charlie Scott drew back and shivered. Cheriton's story had appealed vividly to his sensitive, highly strung nature.

"Call me a coward if you like," he said, "but I couldn't lean out of that window as you are doing, for all Golconda. I could kick myself for my weakness, but it is there all the same."

Acton dropped into a comfortable lounge with a smile of contempt. Scott flushed as he saw this, and timidly suggested that the windows should be closed. With a foot high in the air, Acton protested vigorously.

"No, no," he cried. "Believe what you please, but do not pander to this nonsense. If you should feel like doing the Curtius business, give us a call, and we'll sit on your head, Charlie. But in the name of common sense leave the windows open."

A murmur of approval followed. The line had to be drawn somewhere. As yet no note of tragedy dominated the conversation. Acton and Dixon were deep in the discussion of forthcoming Ascot, and Cheriton joined fitfully in their conversation. Only Michelmore and Scott were silent. The novelist was studying the sensitive face of his young companion, a face white and uneasy, lighted by eyes that gleamed like liquid fire. His glance was drawn to the open window, he sat gazing in that direction with a gaze that never moved.

Thien, in a dazed kind of way, he rose and took a step forward. His eyes were glazed and fixed in horror and repugnance. He looked like a man going to the commission of some vile crime against which his whole soul rebelled. Michelmore watched him with the subtle analysis of his tribe.

For the moment Cheriton seemed to have thrown off the weight from his shoulders. He was lying back in a big arm-chair and discussing the prospects of certain horses. And he was just faintly ashamed of himself.

But Michelmore's quiet, ruminative eyes were everywhere. He was watching Scott with the zest of an expert in the dissecting of emotions, but ready in a moment to restrain the other should he go too far.

It was a thrilling moment for the novelist, at any rate. He saw Scott creeping gently like a cat to the window, groping with his hands as he went, like one who is blind or in the dark. The horror of a great loathing was in his eyes, yet he went on, and on, steadily.

Michelmore stretched out a hand and detained Scott as he passed. At the touch of live, palpitating human fingers he pulled up suddenly, as if he had just received an electric shock.

"Where are you going to?" Michelmore asked in a thin, grating voice.

"I was going to throw myself out of that window," he said.

"Oh! So Cheriton's story had all that effect upon you. Take my advice, and chuck your books for the present. You are in a bad way."

"I'm nothing of the kind, Michelmore. I'm as sound in mind and body as you are. Even if I had never heard that story, the same impulse would have come over me on entering this room. You'll feel it sooner or later, and so will the rest of them. The impulse has passed now, but after to-night you do not catch me in here again."

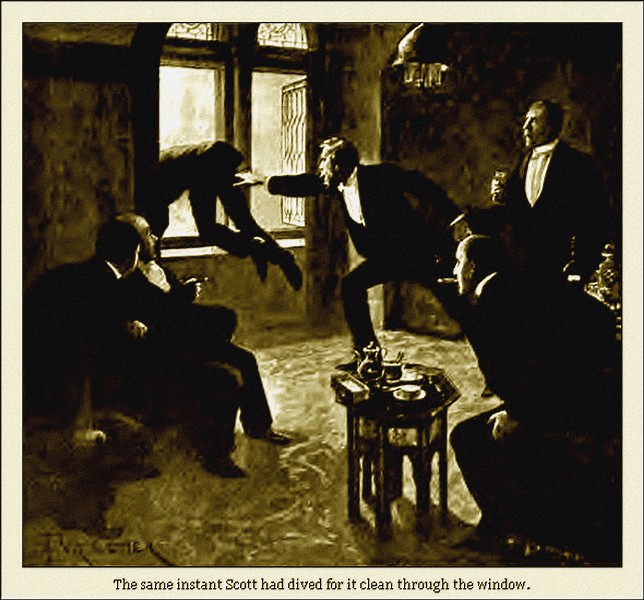

Michelmore did not laugh, for the simple reason that he knew Scott to be speaking from sheer conviction. His was no mind diseased. It was impossible to note that clear skin and clear eye, and doubt that. Michelmore stepped across the room to answer some question of Acton's, and for the moment Scott was forgotten. When the novelist turned again, a cry of horror broke from him.

He saw Scott rise to his feet as if some unseen force had jerked him; he saw the victim of this nameless horror cross like a flash to the window. Then he darted forward and made a wild clutch for Scott's arm. At the same instant Scott had dived for it clean through the window. There was a vision like an empty sack fluttering from a warehouse shoot, and then a dull, hideous, sickening smash below.

Though the whole room took in the incident like a flash, nobody moved for a moment. Who does not know the jar and the snap of a broken limb, the sense of all that is to follow, and the void of pain for the merciful fraction of a merciful second? And then—

And then every man was on his feet. They clattered, heedless of necks, down the stairs, all save Acton, who crossed to the window. He saw a heap of black and white grotesquely twisted on the stones, he saw a slim white figure in satin staring down at a bruised face no whiter than her own.

"God help her!" Acton sobbed. "It's Mrs. Cheriton."

It was. She stood motionless like a statue until the men reached the courtyard. Scott had fallen at her very feet as she was passing into the garden; a single spot of blood glistened on her white gown. She made no sound, though her face twitched and the muscles about her mouth vibrated like harp-strings. Cheriton laid a shaking hand on his wife's shoulder.

"You must come out of this at once," he said hoarsely.

But the fascinating horror of the thing still held Ida Cheriton to the spot. If she could only scream, or faint, or cry—anything but that grey torpor and the horrible twitching of the muscles!

Not until the limp form of Scott was raised from the flags did sound come from Ida's lips. Then she laughed, a laugh low down in her throat, and gradually rising till the air rang with the screaming inhuman mirth.

Cheriton caught Ida in his arms and carried her into the house. The curse of Cain seemed to have fallen upon him. It was he and he alone who had brought about this nameless thing. With a sense of agony and shame, he averted his eyes from those of his wife. But he need not have done so, for Ida had fainted dead away upon his shoulder.

Meanwhile, they had laid Scott out upon a bed brought hurriedly down into the hall. He still breathed; a moan and a shudder came from him ever and again. The horror of his face was caused by something more than pain. Then Cheriton came headlong in.

"Can I do anything!" Acton whispered.

"Yes, yes!" Cheriton cried. "For the love of Heaven go for the doctor! Ride in to Castleford, and bring the first man you can find. Go quickly, for my wife is dying!"

Scott was not dead. The fall had been severe and the injury great, but the unfortunate man still lingered. It was nearly midnight before an anxious, haggard doctor came downstairs.

Cheriton was waiting there. For the last two hours he had been pacing up and down the polished oak floor chewing the cud of a restless, blistering agony.

"My wife!" he gasped, "she is—?"

"Asleep," Dr. Morrison replied. "She is likely to remain asleep for some hours. To be candid, Mrs. Cheriton is under the influence of a strong narcotic. There was no other way of preserving her reason."

"She has not suffered in—otherwise? You know what I mean. Morrison, if anything like that has happened, I shall destroy myself!"

The man of medicine laid a soothing hand upon the speaker's arm. He noted the white, haggard face and the restless eyes.

"You would be none the worse for a tonic yourself," he said. "Mrs. Cheriton is suffering from a great shock. Apart from brain mischief, I apprehend no serious results. What we want to do for the present is to keep that brain dormant. In any case, it will be some weeks before Mrs. Cheriton is herself again. You must be prepared to find her mind temporarily unhinged."

Cheriton swallowed a groan. Then he asked after Scott.

"No hope there, I suppose?" he said.

"Well, yes, strange as it may seem. There is concussion of the brain and a fractured thigh, but I can detect no internal injuries. I can do no more to-night."

Ida Cheriton was sleeping peacefully. There was no sign on her face of the terrible shock she had so lately sustained. She breathed lightly as a little child. As Cheriton entered, Mrs. Michelmore rose out of the shadow beyond the pool of light cast from a shaded candle.

"I am going to stay here till morning," she said.

Cheriton protested feebly. But he was too worn and spent to contend the point. The last two hours seemed to have aged him terribly. The crushing weight of terror held him down and throttled him. General Sherlock's face rose up before him like an avenging shadow. A wild longing to fly from the house and its nameless horror came over him.

Quivering and fluttering in every limb, Cheriton crept downstairs again. A solitary lamp burned in the hall, the house had grown still and quiet. Acton sat in the shadow, smoking a cigarette.

"I have been waiting for you," he said. "The others have gone to bed. It seemed to them that they would be best out of the way, only, of course, they earnestly desire to be called if their services are required."

"Hadn't you better follow their example?" Cheriton asked.

"What are you going to do, then?" Acton suggested. "My dear fellow, I simply couldn't go to bed to-night. Not that I am impressed by this horrible business quite in the same way as yourself—I mean as to its occult side. It's a ghastly coincidence, all the same."

"It may be," Cheriton said wearily. "Heaven only knows!"

With a heavy sigh he rose from his place and crossed the hall. A deadly faintness came upon him, he staggered almost to his fall. His eyes closed, his head fell upon his breast—a strange desire to sleep came over him.

"I'll lie here and close my eyes for a bit," he said.

In a long deck-chair Acton made his friend comfortable. Exhausted Nature asserted herself at length, and Cheriton slept. A minute or two later and the sound of his laboured breathing filled the hall.

"He'll not move for hours," Acton muttered. "Now's my chance."

He moved away quietly, but with resolution. The level-headed sailor, with his logical, mathematical mind, a mind that must have a formula for everything, was by no means satisfied. He would get to the bottom of this thing. If he could do nothing else, he would rob the situation of its unseen terrors.

Without the slightest feeling of excitement, and with nerves that beat as steadily as his own ship's engines, he proceeded to his room. From thence he took a fine hempen rope, and, with this in his hand, proceeded to creep along till he came to the chamber of the dormer window.

Quite coolly he passed in and closed the door behind him. He switched on the electric light and opened the windows wide. Then, with a smile of contempt for his concession to popular prejudices, he proceeded to scientifically arrange the rope he had brought with him. An hour passed, two hours passed, and then Acton rose laggardly to his feet. His face had grown set and pale, his eyes were fixed upon the open window.

* * * * *

Meanwhile, Cheriton had been sleeping like a man overcome with wine. An hour or more passed away before the nature of his slumber changed. Then he began to dream horribly—awful dreams of falling through space and being drawn down steep places by evil eyes and mocking spirits.

Then somebody cried out, and Cheriton came to his consciousness. His heart was beating like a steam hammer, a profuse sweat ran down his face. All the dread weight of trouble fell upon him again.

"I could have sworn I heard somebody call," he said.

He listened intently, quivering from head to foot like a dog scenting danger. It was no fancy, for again the cry was repeated. In the stillness of the night Cheriton could locate the direction easily. It came from outside the house. From one painted window a long lance of moonlight glistened on the polished floor. Outside it was light as day.

With trembling hands Cheriton drew the bolts and plunged into the garden.

"Who called?" he asked. "Where are you?"

"Round here, opposite the courtyard," came a faint voice, which Cheriton had no difficulty in recognising as that of Acton. "Bring a ladder quickly, for I am pretty well done for. Thank goodness somebody heard me!"

Cheriton found a short ladder after some little search, and with it on his shoulders made his way round to the courtyard upon which the dormer window gave. At this very spot the tragedy had taken place.

"Get the ladder up quickly!" Acton gasped.

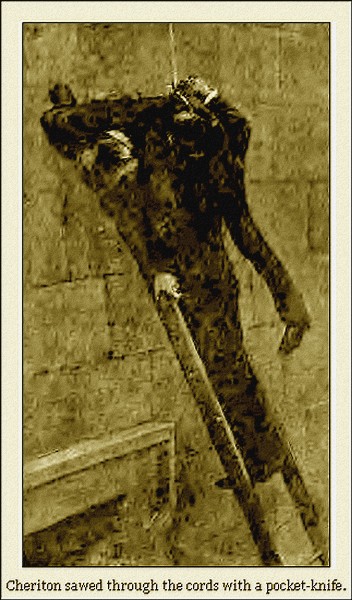

Cheriton complied as swiftly as his astonishment permitted. Acton was suspended some fifteen feet from the ground by a rope firmly tied about his body. He was hanging head downwards, and making feeble efforts to right himself and get a good hand-purchase on the rope. As the ladder was reared he contrived to get a grip and a foothold. He panted and gasped like a man who has been forced under water till his strength is exhausted.

"In the name of Fortune," asked Cheriton, "what does it mean?"

"Get me free first," Acton gurgled. "This rope is sawing me in two. You shall know all about it presently. Just for the moment I would pledge my soul for a glass of brandy and soda-water."

Cheriton sawed through the cords with a pocket-knife, and then helped the limp figure of Acton to the ground. A minute or two later, and the latter was reclining on a chair, with a full tumbler clinking against his teeth. The colour filtered into his cheeks presently, his hand grew steady.

"I wouldn't go through the last half-hour again for a flagship," he explained. "After you had gone to sleep, I made up my mind to test the dormer window business for myself. So as to be absolutely on the safe side, I fastened the end of a coil of rope to the stone pillar inside the window frame, and the other end I made fast round my own waist. Then I lighted a cigarette and waited.

"It was perhaps an hour before I experienced any sensation. Then I found that I could not keep my eyes from that window. I abandoned the struggle to do so, and then I had a mind-picture of myself lying dead on the stones below. I could see every hurt and wound distinctly. A violent fit of trembling came over me, and I was conscious of a deep feeling of depression. My mind was permeated with the idea that I had committed some awful crime. I was shunned by everybody about me. The only way out of the thing was to take my own life. Then I rose and made my way to the window.

"I give you my word of honour, Cheriton, I struggled against that impulse until I was as weak and feeble as a little child. I had entirely forgotten that I was protected from damage by the rope. If I had remembered, I should have most certainly been compelled to remove it, and by this time I should be lying dead and mangled in the courtyard. I would not go through it all again for the Bank of England. The horror is indescribable.

"Well, I fought till I could fight no longer. With a wild cry I closed my eyes and made a headlong dash for the window. I flung myself out. I fell until the cord about my waist checked me and nearly dislocated every limb. Then came the strangest part of this strange affair. Once I was clear of that infernal room, the brooding depression passed from me, and my desire was to save my life, to struggle for it to the end. I was myself again, with nerves as strong and steady as ever, and nothing troubling me beyond the weakness engendered by my efforts to get free. I was forced to cry for help at last, and fortunately you heard my call. And I'm not going to doubt any more. For Heaven's sake have that window blocked up without delay!"

Cheriton turned his grey face to the light.

"I will," he said. "It shall be done as soon as possible. How faithfully General Sherlock's prophecy has been verified I know to my sorrow."

Scott would recover. There was an infinite consolation in the doctor's fiat, which he gave two days later. His recovery would of necessity be painfully slow, for the injuries were many and deep-rooted. But youth and a good constitution, in the absence of internal injuries, would do much.

As yet Scott was unconscious. Nor was the condition of Ida Cheriton very much better. It had been deemed prudent to tell her the good news so far as Scott was concerned, but it seemed to convey very little impression.

For, sooth to say, the patient was not progressing as well as she might. She did not seem to be able to shake off the strange mistiness that clouded her intellect, she could only remember the horror she had seen. Charlie was dead, and she had watched him come headlong to his destruction. During her waking hours she lay still and numb, the horror still in her eyes.

"It isn't madness?" Cheriton asked hoarsely.

"No," Morrison replied. "I should say not. The shock has caused the brain to cease working for a time. Personally, I should prefer delirium. I can only pursue my present course of treatment. When the trembling fits come on, the drug will have to be administered as ordered. I will take care that you have plenty of it in the house."

There was no more to be said, no more to be done, only to wait and hope. One or two drear, miserable days dragged their weary length along. The house was devoid of guests by this time; it was better thus, with two patients there fighting for health and reason, and the whole place was under the sway of two clear-eyed nurses whose word was law.

As yet no steps had been taken to have an end put to the cause of all the mischief. Under the circumstances that was impossible. Anything in the way of noise would have been sternly interdicted, and it was out of the question to dispense with din and clamour with masons and bricklayers about. Not that there was any danger, for everybody shunned the haunted room like the plague. Not a servant would have entered it for untold gold.

A great stillness lay over the house, for it was night again. Downstairs, in the dining-room, Cheriton dined alone, and smoked gloomily afterwards. The soothing influence of tobacco was one of the few consolations he possessed. He rose for another cigarette, but his cupboard was empty.

In the trouble and turmoil of the last few days the all-important tobacco question had been forgotten. It seemed to Cheriton that he had never thirsted for a cigarette as he did at this moment. He positively ached for it.

Then he recollected. On the night of the tragedy they had all been smoking in the room with the dormer window. There were a couple of boxes up there, both of them practically intact. To get them would be an easy matter.

Cheriton hesitated but a moment, then he passed up the stairs. As he opened the door of the haunted chamber and turned up the light, he saw the window was open, for nobody had entered since the adventure of Acton there. Cheriton grabbed the boxes of cigarettes and turned to leave the room.

As he did so he glanced involuntarily at the open window. He shuddered and closed his eyes. When he opened them again, he found, to his surprise and horror, that he was some feet closer to the window than before. A cold perspiration chilled him to the bone, he tried to move and tried in vain.

When he did move, it was to advance still nearer to the window. Suddenly there came over him a wave of depression, the same feeling of dull despair so graphically described by Acton. It drew him on and on.

"Great Heaven!" he groaned, "I am lost! My poor wife!"

Then a strange thing happened. A light foot was heard coming up the stairs. A moment later and Ida stood in the corridor in full view of her husband. She made a sweet and thrilling picture, in her white, clinging gown covered with foamy lace; her shining hair hung over a pair of ivory shoulders.

"Ralph," she said, and her voice was low and sweet, "I want you."

She had risen from her bed in the temporary absence of her nurse. Something in her clouded brain bade her seek for her husband. In a dim fashion she saw him, knew that he stood before her.

She advanced with a tender half-smile. A sudden ray of hope jostled and almost released Cheriton's frozen limbs. Then he saw that the danger was likely to be doubled, the peril hers as well as his.

"Do not come any further," he cried. "Do not, I implore you!"

Ida paused, half irresolute. What was Ralph doing there, and why did he look at her with that face of terror? Then the cloud rolled back from her brain for a moment. It was from that fatal room that Charlie had gone to his death. A quivering little cry escaped her.

"Come to me!" she implored. "Come to me, Ralph. Why are you in that awful place? If you do not come, I must come to you."

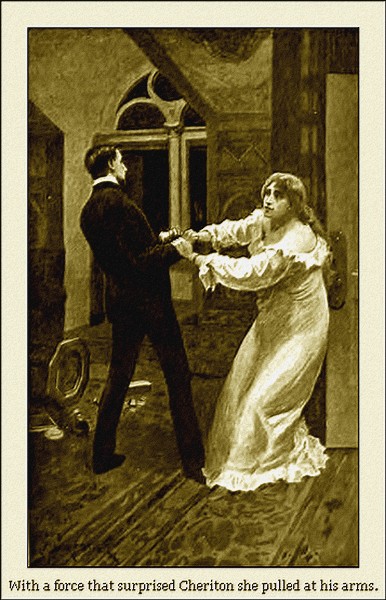

She advanced with hands outstretched and eyes full of entreaty. And Cheriton made an effort that turned him faint and dazy. Once Ida entered that room, he knew only too well that nothing could save the pair of them. But he could not move, he could only wave Ida back and speak with dumb lips.

She came on, and on, until her hands lay on his. With a force that surprised Cheriton she pulled at his arms. There was no longer the light of madness in her eyes, but a desire to save him fighting the terror that overcame her. The slim, white figure had a strength almost divine.

"For my sake!" she cried. "Come, come, come!"

As her voice rose higher and higher, some of her strength seemed to pass into Cheriton. He no longer looked to the window. He raised one foot and put it down a good yard nearer the door. With a last mighty effort, and an effort that turned him sick and dizzy, and strained his heart to bursting point, he gathered Ida in his arms and cleared the space to the door with a spring. The lock was snapped, then the key went whizzing through a window into a thicket of shrubs, where it was found many days after.

Cheriton dropped in the corridor, and there he lay unconscious for a time. When he came to himself again, Ida was bending over him. Her sweet eyes were filled with tears, but in those eyes swam the light of reason.

"Don't speak, dear," Ida said tenderly. "I know everything now. I heard them talking as behind a veil when I lay there, but now I understand. Ralph, did you not tell me that Charlie would live?"

"The doctor said so, darling. Ida, you have saved my life."

"Yes, and I fancy I have saved my reason at the same time. Take me back to my room, please; I am so tired, so tired."

Ida closed her eyes and slept again. But it was the dreamless sleep of the child, the nurse said with a smile, and there would be no more anxiety now. All the same, Mr. Cheriton must go away at once. As to his wife, it was a mere matter of time; Nature would do the rest.

* * * * *

People who know the story of the dormer window are many, but of all those who speak with authority not one can explain what lies beyond the veil.